Abstract

We have previously shown that in the red alga Rhodella violacea, exposure to continuous low intensities of light 2 (green light) or near-saturating intensities of white light induces a ΔpH-dependent PSII fluorescence quenching. In this article we further characterize this fluorescence quenching by using white, saturating, multiturnover pulses. Even though the pulses are necessary to induce the ΔpH and the quenching, the development of the latter occurred in darkness and required several tens of seconds. In darkness or in the light in the presence of 2,5-dibromo-3-methyl-6-isopropyl-p-benzoquinone, the dissipation of the quenching was very slow (more than 15 min) due to a low consumption of the ΔpH, which corresponds to an inactive ATP synthase. In contrast, under far-red illumination or in the presence of 3-(3,4-dichlorophenyl)-1,1′-dimethylurea (only in light), the fluorescence quenching relaxed in a few seconds. The presence of N,N′-dicyclohexyl carbodiimide hindered this relaxation. We propose that the quenching relaxation is related to the consumption of ΔpH by ATP synthase, which remains active under conditions favoring pseudolinear and cyclic electron transfer.

Photosynthetic organisms convert light energy into chemical energy. The energy absorption occurs at the level of the antenna of two membrane-pigment complexes, PSI and PSII. The absorbed energy is transferred to the reaction centers, which operate in series. The electron transport from water to NADP+ is coupled to a proton translocation across the membrane, generating a proton motive force for the synthesis of ATP.

Trapping by the photochemical centers is the main pathway of deactivation of the excitons formed by the absorption of photons. Fluorescence and thermal dissipation are the other ways to deactivate these excitons. Photochemistry and qP are maximal when all PSII centers are open and the Φo is low. When all of the centers are closed, qP is suppressed and the Φo is concomitantly increased to its maximal value (Φm). Fluorescence is modulated by the oxidoreduction state of the primary acceptor QA (Duysens and Sweers, 1963; van Gorkom, 1974). Nonphotochemical processes can also reduce the Φo. Several mechanisms may be involved at the level of the antenna system and the PSII reaction centers (Krause and Weis, 1991; Horton and Ruban, 1992). NPQ of fluorescence is ascribed to three major processes: state transitions, qE, and photoinhibition. These different mechanisms have been widely studied either in vitro, in thylakoid and chloroplast, or in vivo, in leaves and green algae cells. The different types of NPQ can be recognized because they are developed at different light intensities, inhibited by specific chemical treatments, and relaxed in the dark with characteristic kinetics (Demmig and Winter, 1988; Horton and Hague, 1988; Quick and Stitt, 1989; Lee et al., 1990; Walters and Horton, 1991, 1993).

qE is related to a transthylakoid proton gradient formed during electron transport (Krause, 1973; Briantais et al., 1980; Krause et al., 1982). It was shown that in higher plants and in green and brown algae, part of this quenching is correlated to the dissipation of an excess of excitation energy in the PSII antenna complex. The formation of this quenching is accompanied by the accumulation of de-epoxidated xanthophyll (Demmig et al., 1987; Bilger et al., 1989; Demmig-Adams, 1990; Gilmore and Yamamoto, 1991) and conformational changes (most probably, aggregation) of LHCII (Horton et al., 1991, 1996; Noctor et al., 1991; Ruban et al., 1992a, 1993). Part of the quenching was also attributed to energy dissipation in the reaction center by radiationless decay (Weis and Berry, 1987) or rapid charge recombination (Krieger et al., 1992; Krieger and Weis, 1993). The mechanism of qE concerns PSII, but not PSI.

Different incident wavelengths can selectively excite one of the two photosystems. Higher plants, green algae, and cyanobacteria have developed a mechanism called state transitions to optimize the utilization of the captured energy and to regulate the production of ATP and NADPH. In higher plants and green algae, the redistribution of absorbed excitation energy between PSI and PSII involves redox-dependent phosphorylation/dephosphorylation reactions of LHCII, leading to opposite changes of the cross-section of the PSII and PSI antenna complexes (for review, see Haworth et al., 1982; Williams and Allen, 1987; Allen, 1992, 1995). Both photosystems are involved in this mechanism.

In red algae and cyanobacteria, the energy collection of PSII is mainly achieved by the phycobilisomes, large extramembrane complexes formed by phycobiliproteins, whereas Chl a is the major energy-collector pigment in PSI. The mechanisms involved in PSII fluorescence quenching in phycobilisome-containing organisms are not as well characterized as in higher plants. It was proposed that state transitions were related to redistribution of the absorbed energy by changes in the spillover between PSII and PSI (Ley and Butler, 1980; Biggins et al., 1984; Bruce et al., 1985; Olive et al., 1986; Vernotte et al., 1990) or to changes in the cross-section of the antenna of both PSI and PSII (Allen et al., 1985; Sanders and Allen, 1987, 1988). It was also suggested that only PSII is involved in the mechanism of fluorescence quenching (Satoh and Fork, 1983). However, few studies analyzed the possibility of the existence of a qE in red algae or cyanobacteria.

Recently, we have studied the adaptation to changes in light intensity and quality in the red alga Rhodella violacea (Delphin et al., 1995, 1996). We demonstrated in vivo that the fluorescence changes produced by illumination at different wavelengths were independent of protein phosphorylation (Delphin et al., 1995). We have also shown that illumination of R. violacea cells with light 2 (light preferentially absorbed by the phycobiliproteins) induced a large quenching of PSII fluorescence. This quenching was suppressed by addition of the uncoupler NH4Cl, whereas it was maintained when the cells were exposed to light 1 (light preferentially absorbed by the PSI) illumination in the presence of DCCD, an inhibitor of ATP synthase. The level of the PSI-related fluorescence (detected at low temperature) did not change under these different conditions. We concluded that the fluorescence changes commonly associated with state 2 transition are in fact due to a ΔpH-dependent quenching (Delphin et al., 1996).

It has been generally assumed that the fluorescence changes induced by different light conditions in red algae and cyanobacteria are related to the same mechanism. However, we have demonstrated that such changes are associated with a transmembrane ΔpH in red algae (Delphin et al., 1996), and Campbell and Öquist (1996) proposed that in cyanobacteria, the changes in Φo are only related to state transitions. In our previous studies on fluorescence quenching mechanisms in red algae, we used the light-saturation-pulse method, in which brief pulses of intense light remove all of the qP and reveal the remaining quenching, which is nonphotochemical in nature, as shown by the level of the Fm assessed during the pulse (Bradbury and Baker, 1984; Renger and Schreiber, 1986; Schreiber et al., 1986, 1995; Quick and Stitt, 1989; Krause and Weis, 1991; Walters and Horton, 1991; Lokstein et al., 1993). We observed that the saturating, multiturnover, white pulses induced a large quenching of Fm′. In this article we further characterize the PSII fluorescence quenching mechanisms in red algae by using saturating, multiturnover pulses at different intensities, lengths, and frequencies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Culture of Algae

Red algae (Rhodella violacea) cells were grown autotrophically in Erdschreiber medium (modified seawater) enriched with FeCl3·6H2O (0.6 mg L−1) at 20°C. The cultures were continuously flushed with sterile air. Light was provided by cool-white fluorescent tubes (Philips, Eindhoven, The Netherlands) at an intensity of 60 μmol photons m−2 s−1 in a 16-h light/8-h dark cycle. Cells were collected at a concentration of about 8.0 × 105 cells mL−1, corresponding to a Chl concentration of 5.5 μg Chl mL−1. Porphyridium cruentum cells were grown in the same conditions as R. violacea cells, except that the culture medium was artificial seawater prepared according to the method of Jones et al. (1963) and the light intensity was 30 μmol photons m−2 s−1. Cells were collected at a concentration of about 4.5 × 106 cells mL−1, corresponding to a Chl concentration of 4.5 μg mL−1. The cells were maintained under white, low-light conditions. Each experiment began with 5 min of dark adaptation followed by 4 min of cell incubation in far-red light.

Fluorescence Measurements

Chl Φo was measured at the same temperature as that of the growth cultures with a pulse-amplitude modulated fluorometer (model 101, Heinz-Walz, Effelrich, Germany) adapted to an oxygen electrode (model DW1, Hansatech, King's Lynn, UK), as previously described by Arsalane et al. (1994). In the absence of any actinic light, the minimal Φo (Fo or Fo′) was measured by the nonactinic-modulated beam. Saturating, multiturnover, white-light pulses (3200 μmol photons m−2 s−1) were applied to assess the maximal Φo (Fm or Fm′). In this paper the maximal Φo obtained by a train of saturating white light pulses under nonactinic-modulated light is also called Fm′. The pulses were generated by an electronic shutter (Uniblitz, Vincent, Rochester, NY) in front of a quartz-iodine lamp (model KL-1500, Schott, Mainz, Germany) that was continuously on. The shutter was controlled by the accessory module pulse-amplitude modulated fluorometer (model 103, Heinz-Walz).

Two types of recordings were carried out in these experiments, those measured in milliseconds and those measured in seconds. For the slow fluorescence changes, the sampling was done every 10 ms and averaged every 3 s. For a correct evaluation of Fm (or Fm′) during a light pulse of 800 ms, the signal was averaged over the second half of the light pulse (from 400 to 800 ms). During inductions in the millisecond range, the fluorescence signal was sampled every millisecond. The Fo level was assessed with the modulated detector beam before the shutter opened. There was a 3-ms delay between the trigger of the signal recording and the shutter opening. The shutter took 3 ms to be fully open.

The different background continuous illuminations were obtained from another KL-1500 lamp, which was either used as white light or filtered at 540 nm for green light (filter 70617 AM-4064, Oriel, Stratford, CT), at 601 nm for orange light (filter: 40 599 10, Balzers Pseiffer, North America, Hudson, NH), or at 435 nm for blue light (filter 4–35, Corning Instruments, Corning, NY). Far-red light (735 ± 10 nm) was obtained from a light-emitting diode (102-FR, Heinz-Walz). Data acquisition, shutter control, and pulse averaging were driven by homemade software through a 12-bit analogic digital converter, as previously described (Arsalane et al., 1994). When indicated, 77 K fluorescence emission spectra were measured as described in Delphin et al. (1996).

RESULTS

Effect of Saturating, Multiturnover Pulses on Maximal Fluorescence

This study was performed on two strains of red algae, R. violacea and P. cruentum. We have already shown that in R. violacea, a large ΔpH-dependent quenching of PSII fluorescence is generated by continuous green light (absorbed mainly by phycobilisomes) even at low light intensities (Delphin et al., 1996). Similar results have been obtained in P. cruentum cells. In this alga, as in R. violacea, the Fm′ level was maximal in far-red-adapted cells. Under green-light illumination, a large Fm′ quenching was developed. The main part of the fluorescence quenching was suppressed when the ΔpH across the membrane was suppressed by addition of NH4Cl or nigericin, even under green-light illumination (data not shown).

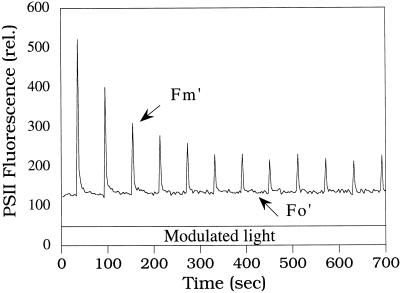

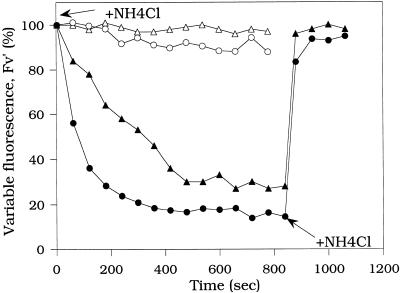

Near-saturating and saturating intensities of continuous white light also induce a large ΔpH-dependent fluorescence quenching in red alga cells (Delphin et al., 1996). Moreover, in our previous studies, we have observed that the repetitive application of saturating pulses of white light induces a large decrease of Fm′ in red alga cells. R. violacea and P. cruentum dark-adapted cells were preincubated in far-red light (75 μmol photons m−2 s−1) for 4 min to ensure a maximal level of Fm′ (Delphin et al., 1996). The far-red light was turned off before a train of saturating pulses (800 ms, 3200 μmol photons m−2 s−1) was applied. The interpulse time was 60 s. Figure 1 shows that Fv′ (Fm′ − Fo′) decreased during a series of pulses to reach a level of 20% to 30% of the maximal Fv′ in R. violacea cells. No variation of the Fo′ level was detected. This Fv′ quenching was also observed when the train of saturating pulses was directly applied to dark-adapted cells. Similar results were obtained with P. cruentum cells (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Effect of a train of saturating pulses (800 ms, 3200 μmol photons m−2 s−1) on Fm′ and Fo′ levels in R. violacea cells. Dark-adapted (for 5 min) cells were preincubated for 4 min in far-red light (75 μmol photons m−2 s−1). Far-red light was turned off before the pulses were applied; pulses were spaced by 60 s. rel., Relative units.

Low-temperature fluorescence spectra of cells preadapted to far-red light and of those exposed to a sequence of saturating pulses were performed in the presence of an external fluorescence probe (phycocyanin from Spirulina maxima). Low-temperature emission spectra were deconvoluted into Gaussian components, and the areas corresponding to F695 (PSII fluorescence), F718, (PSI fluorescence), and F650 (probe fluorescence) were calculated. The F695 to F718 ratio decreased from 1.4 to 0.7 after the sequence of saturating pulses. The calculated ratio of F718 to F650 showed that PSI fluorescence was similar before and after the sequence of pulses (F718 to F650= 1 ± 0.03). In contrast, the F695 to F650 ratio varied from 1.4 ± 0.04 to 0.8 ± 0.03, indicating a decrease in PSII fluorescence. These results suggest that a specific quenching of F695 was responsible for the decrease of the F695 to F718 ratio.

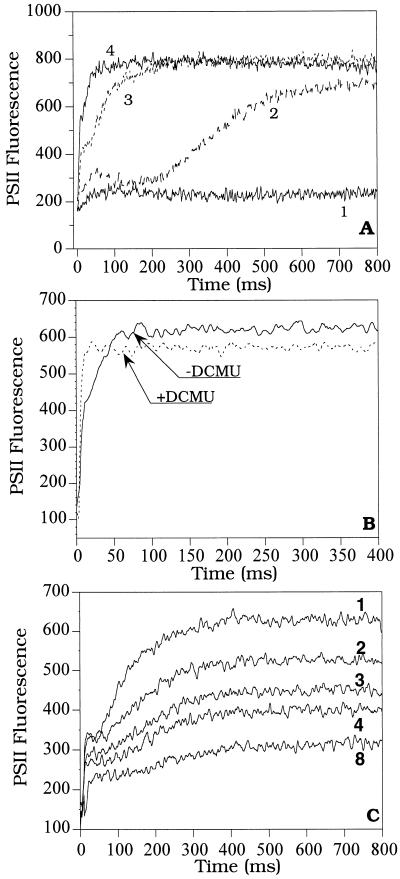

Effect of the Intensity and Length of Light Pulses

To further characterize the effect of individual pulses on the development of fluorescence quenching, the length and intensity of the pulses were systematically varied. To monitor the fluorescence changes occurring during the pulse, induction curves were recorded during the pulse at different intensities: 15, 50, 300, and 3200 μmol photons m−2 s−1 (Fig. 2A). The pulse was applied to cells preincubated for 4 min in far-red light. The induction curves were recorded 30 s after the far-red light was turned off. Under light intensities higher than 300 μmol photons m−2 s−1 during the pulse, the P level was the maximum Φo attained during the transition. Under 3200 μmol photons m−2 s−1 light intensity, the P level was attained after 70 ms (trace 4), whereas under 300 μmol photons m−2 s−1, the P level was reached in 300 ms (trace 3). When the light intensity was lower than 300 μmol photons m−2 s−1, the P level was not reached (traces 2 and 1, Fig. 2A). Fluorescence quenching was not developed during the light pulse. Figure 2B shows that the P level was slightly higher than the Fm′ measured in the presence of 10−5 M DCMU. In the presence of DCMU, the oxidized PQ pool is a quencher of fluorescence (Vernotte et al., 1979).

Figure 2.

Fluorescence inductions of R. violacea cells. A, 800-ms duration pulses of varying white-light intensities: 15 (trace 1), 50 (trace 2), 300 (trace 3), and 3200 (trace 4) μmol photons m−2 s−1; B, a saturating pulse (800 ms, 3200 μmol photons m−2 s−1) in the absence or in the presence of DCMU (10 μm); C, a train of saturating pulses (800 ms/300 μmol photons m−2 s−1) spaced by 60 s. Fluorescence inductions during the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th, and 8th pulse are presented. Dark-adapted cells were preilluminated with far-red light (75 μmol photons m−2 s−1) for 4 min. Induction curves were recorded 30 s after far-red light was switched off.

Figure 2C shows the fluorescence induction generated during the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th, and 8th pulses of 300 μmol photons m−2 s−1 and 800 ms in duration. Each additional pulse produced an additional decrease of the variable fluorescence visible during the subsequent pulse. We observed that almost all of the levels of fluorescence were affected by quenching. However, the P level was the most affected: at the end of a series of pulses the fast initial phase was diminished by one-half, whereas the slower phase (rise to P level) almost disappeared. The Fo′ remained constant.

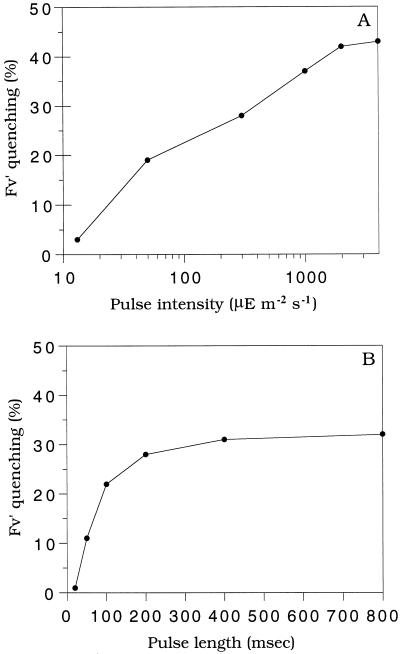

The quenching of the variable fluorescence induced by the first light pulse 800 ms in duration and detected by the second pulse was proportional to the light intensity (Fig. 3A). If the length of pulses was varied while fixing the intensity to 300 μmol photons m−2 s−1, we observed that the quenching increased with the length of the pulse up to 400 ms (Fig. 3B). As shown in Figure 3C, 300 ms was the time required to reach the P level. No additional quenching was induced if pulses were of a longer duration (up to 800 ms).

Figure 3.

Effect of the intensity and the length of the pulse on the extent of the fluorescence quenching in R. violacea cells. A, Pulses of 800 ms at different light intensities. B, Pulses of different lengths at 300 μmol photons m−2 s−1. Calculations of the percent of quenching produced by a first pulse were done on the variable fluorescence (Fv′ = Fm′ − Fo′) of a second pulse (800 ms, 3200 μmol photons m−2 s−1) applied 60 s after the first pulse. A pulse given after 2 min of far-red illumination was set as 100% of Fv′.

Fv′ Quenching and the Dark Period between the Pulses

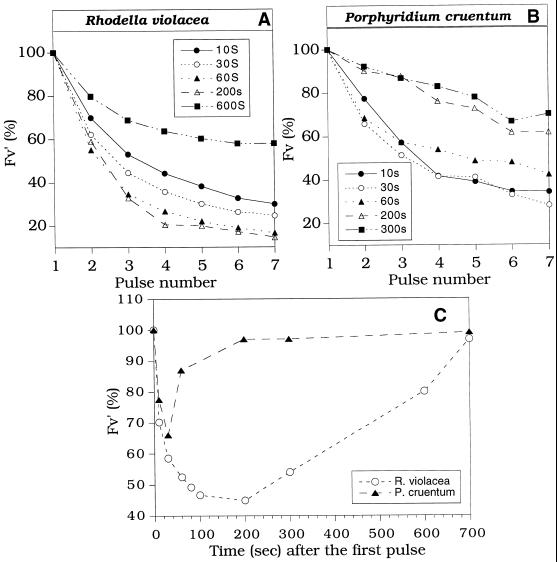

To determine the kinetics of formation and relaxation of Fv′ quenching, the duration of dark periods between pulses was varied. A train of saturating pulses (800 ms, 3200 μmol photons m−2 s−1) spaced by 10, 30, 60, 200, 300, or 600 s was applied to far-red light-adapted cells after far-red light was turned off. In both strains and for all the frequencies of pulses, the level of Fv′ decreased (Fig. 4, A and B).

Figure 4.

Effect of the pulse frequency on the Fv′ level in far-red-light-adapted R. violacea cells (A) and P. cruentum cells (B) as a function of the number of pulses. Pulses of 800 ms, 3200 μmol photons m−2 s−1, were spaced by 10, 30, 60, 200, 300, or 600 s. A pulse given after 2 min of far-red illumination was set as 100% of Fv′. C, Kinetics of fluorescence quenching during dark incubation after a light pulse (800 ms, 3200 μmol photons m−2 s−1) in R. violacea (○) and P. cruentum cells (▴). The detection and calculation of the percent of quenching was done as in Figure 3 except that the detecting pulse was applied after different times.

Figure 4C shows the quenching of Fv′ induced by one pulse and detected by a second pulse after different dark periods. A dark period between 100 and 200 s was optimal to reach the quenched state in R. violacea. When the dark period was longer than 200 s, the effect of the pulse began to be dissipated between the pulses (Fig. 4, A and C). The effect of each pulse seemed to dissipate faster in P. cruentum than in R. violacea cells. In P. cruentum cells a dark period of 30 s was optimal to reach a maximal Fm′ quenching (Fig. 4, B and C). When the spacing between the pulses was 60 s or more, a reverse of the quenching became evident.

Origin of the Fm′ Quenching Induced by Saturating White Pulses

NH4Cl Effect

As mentioned above, the formation of a ΔpH across the thylakoid membrane is responsible for the fluorescence quenching observed under continuous, near-saturating white light (Delphin et al., 1996). Therefore, we assumed that the quenching induced by saturating white pulses would be ΔpH dependent. To confirm this hypothesis, chemical and light treatments that can alter the extent of the ΔpH were applied before or during the pulse sequences. In the first experiment, the ΔpH was not allowed to accumulate during the series of saturating pulses: the uncoupler NH4Cl (2 mm) was added 1 min before the first pulse. Figure 5 shows that in the presence of the uncoupler, repetitive pulses did not affect (P. cruentum cells) or slightly affected (R. violacea cells) the level of Fm′ (or Fv′). In the second experiment, NH4Cl was added after 12 pulses, after the fluorescence quenching was formed. Addition of the uncoupler suppressed most of the quenching (Fig. 5). The same result was obtained when the uncoupler nigericin was used instead of NH4Cl (data not shown).

Figure 5.

Effect of NH4Cl on the Fv′ level in R. violacea (circles) and P. cruentum (triangles) cells during a train of saturating pulses (800 ms, 3200 μmol photons m−2 s−1) spaced by 60 s. NH4Cl (2 mm) was added 1 min before the onset of the train of pulses (open symbols), or after 14 pulses (closed symbols). Calculations of the percentage of quenching were done on the variable fluorescence recorded during pulses, Fv′ = Fm′ − Fo′. The first pulse of the train was set as 100% of Fv′.

Far-Red Light Effect

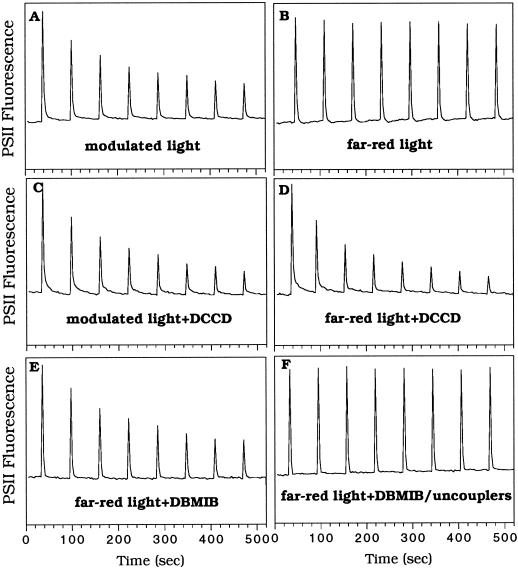

Because the effect of the pulses was accumulative, we assumed that the ΔpH was not (or not sufficiently) dissipated in darkness between the pulses. In contrast, when the pulses were separated by 60 s of far-red illumination, only a slight decrease of Fm′ was observed (Fig. 6B), indicating that illumination by far-red light favored the consumption of ΔpH between the pulses. When DCCD (40 μm), an inhibitor of ATP synthase, was present while the background of far-red illumination was maintained, a large quenching of Fm′ appeared again (Fig. 6D), indicating the absence of ΔpH consumption. Under modulated illumination the decrease of Fv′ was slightly faster in the presence of DCCD (Fig. 6C) than in its absence (Fig. 6A). Under far-red illumination and in the presence of DCCD, the decrease of Fv′ was even faster (Fig. 6D). These results suggest that ATP synthase was active during part of the pulse and during far-red illumination.

Figure 6.

Effect of far-red light in the dissipation of fluorescence quenching in R. violacea cells and the influence of DCCD and DBMIB. The far-red preincubation light was maintained during the trains of pulses in B, D, E, and F. The trains of pulses (800 ms, 3200 μmol photons m−2 s−1) were applied in the absence of any chemical (A and B) or in the presence of DCCD (40 μm) (C and D), DBMIB (10 μm) (E), or DBMIB (10 μm) plus nigericin (100 μm) (F). DCCD was added in the dark and incubated for 10 min before the far-red light was turned on. DBMIB and nigericin were added just before turning on the far-red light.

Figure 6B shows that illumination by far-red light eliminated the fluorescence quenching induced by the white, saturating pulses. However, cyclic electron transport functioning under far-red illumination should induce a proton translocation across the membrane, increasing the ΔpH. The existence of a ΔpH coupled to cyclic electron transport around the PSI induced by far-red illumination was demonstrated by incubating the cells in the presence of DCCD (40 μm) under far-red illumination in the absence of light pulses. Under these conditions, Fv′ decreased 40% after 10 min and 70% after 20 min of far-red incubation. In the absence of DCCD, no fluorescence quenching was detected, suggesting that the ΔpH formed was small and/or that it was rapidly consumed.

The results presented in this section confirm that the persistence of the fluorescence quenching in darkness was due to the inactivation of ATP synthase in the dark, leading to a very slow consumption of the ΔpH. We propose that far-red light inhibited the development of fluorescence quenching by maintaining the ATP synthase active between the pulses. Under far-red illumination, PSI is active and it can be assumed that reduction of PQ molecules via a NAD(P)H-PQ oxydoreductase would provide some electrons to maintain pseudolinear electron transfer and thioredoxin reduction, favoring ATP synthase activity.

DBMIB Effect

We assumed that DBMIB, which inhibits linear and cyclic electron transport by interaction with the Qo site of the cyt b6/f complex, may hinder the ATPase activity under far-red illumination. The presence of DBMIB (10 μm) when the train of pulses was superimposed to far-red illumination also induced the Fm′ quenching (Fig. 6D). The fact that the Fo′ level between the pulses remained low and constant indicated that the plastoquinol molecules were reoxidized during the 60-s far-red illumination between the light pulses. This reoxidation had to occur via a pathway that did not involve the cyt b6/f, probably via equilibrium with molecular oxygen. Our results also indicated that the reoxidation of the PQ molecules allowed PSII turnover during each successive pulse. During each light pulse, even in the presence of DBMIB, there was enough proton pumping associated with PQ reduction to induce fluorescence quenching that was not dissipated between the pulses. The DBMIB effect was suppressed by addition of uncouplers, confirming that DBMIB hindered the consumption of the ΔpH under far-red light (Fig. 6E).

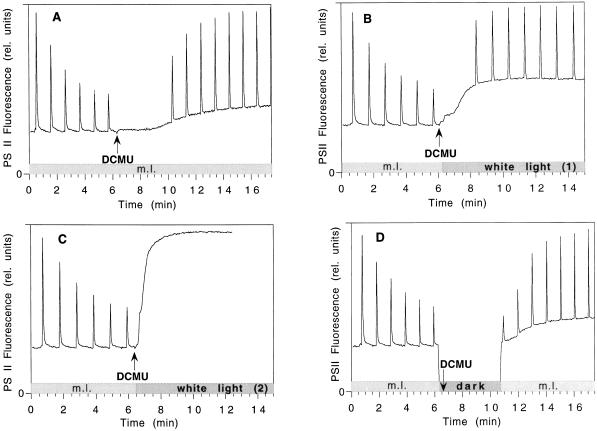

DCMU Effect

We have already reported that addition of DCMU suppressed the fluorescence quenching induced by continuous green light (Delphin et al., 1996). In certain conditions, DCMU is also able to eliminate the fluorescence quenching induced by the train of pulses. Figure 7, A through C, shows the effect of DCMU (10 μm) under different light conditions. DCMU was added to the “quenched” sample and then the cells were illuminated for 4 min by “nonactinic” modulated light (Fig. 7A), 50 μmol photons m−2 s−1 white light (Fig. 7B), and 200 μmol photons m−2 s−1 white light (Fig. 7C) before a train of saturating pulses was applied. The rate of quenching relaxation depended on the light intensity: 8 min under the modulated light (Fig. 7A), 4 min at 50 μmol photons m−2 s−1 of white light (Fig. 7B), and 1 min at 200 μmol photons m−2 s−1 (Fig. 7C). Illumination was necessary for the DCMU effect (Fig. 7D). DCMU added in the dark, after the formation of Fm′ quenching, did not suppress the quenching even if the dark period was for 4 min (Fig. 7D). Only after 15 min of dark incubation in the presence of DCMU did the quenching begin to relax (data not shown). This clearly rules out the possibility of DCMU acting as an uncoupler.

Figure 7.

Effect of DCMU on Fm′ quenching in R. violacea cells. Far-red-adapted cells were exposed to a train of pulses after turning off the far-red light. DCMU (10 μm) was added after six light pulses (800 ms, 3200 μmol photons m−2 s−1) spaced by 60 s, under the nonactinic-modulated light (0.046 μmol photons m−2 s−1) (A–C) or in the dark (D). After DCMU addition, the cells were incubated for 4 min in modulated light (A); 50 μmol photons m−2 s−1 white light (B); 200 μmol photons m−2 s−1 white light (C); or darkness (D). Then, the cells in the dark were shifted to modulated light. The other samples were maintained under the same light conditions and a train of saturating pulses was applied.

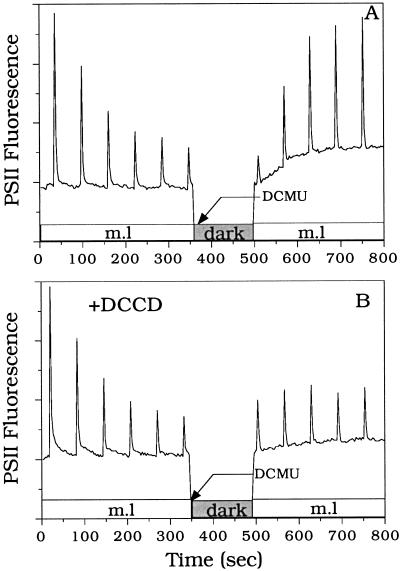

Fluorescence quenching was suppressed by DCMU in the absence but not in the presence of DCCD (40 μm) (Fig. 8). Moreover, the presence of DCCD largely decreased the actinic effect of the modulated light observed in the presence of DCMU. Since DCCD is an inhibitor of ATP synthase, one can conclude that under illumination, the presence of DCMU eliminated the quenching by preventing the formation of the ΔpH coupled to PSII activity without inhibiting the consumption of the ΔpH formed by the illumination period preceding DCMU addition. Under illumination in the presence of DCMU, PSI is active and pseudolinear, and cyclic electron transport would occur. Under these conditions the ΔpH consumption seems to be faster than its buildup induced by cyclic electron transport or by far-red illumination.

Figure 8.

Effect of DCMU in the absence or presence of DCCD in R. violacea cells. Far-red-adapted cells were exposed to a train of pulses in the absence (A) or in the presence (B) of DCCD (40 μm). DCCD was added in the dark and incubated for 10 min before cells were exposed to far-red light (2 min). Far-red light was turned off before the train of pulses was applied. DCMU (10 μm) was added in the dark and after six light pulses spaced by 60 s. After 4 min of dark incubation the modulated light was turned on. One pulse was immediately applied and a second one was applied after 5 min.

DISCUSSION

We have previously shown that in red algae exposed to continuous illumination, low and high intensities of light 2 (green light) and near-saturating and saturating intensities of white light induced a PSII fluorescence quenching triggered by the formation of a transthylakoid ΔpH and not by the reduction of the PQ. Quenching was relaxed under conditions that suppressed the ΔpH across the membrane, even when the PQ remained reduced (Delphin et al., 1996). In the present paper we demonstrated that in red algae (R. violacea and P. cruentum), white-light pulses of a wide range of intensities and lengths were able to induce a ΔpH-dependent Fm′ quenching with no change in Fo′. When the formation of ΔpH was hindered by the presence of NH4Cl or nigericin, no fluorescence quenching occurred. The quenching induced by a train of pulses rapidly disappeared after addition of uncouplers.

Even though fluorescence quenching was induced by light, it did not develop during a pulse with a duration less than or equal to 800 ms. Fluorescence quenching developed during the dark period following the pulse, indicating that, once induced, light was not necessary for its development. The quenching was revealed by the following light pulse. Several tens of seconds were required to develop the maximal quenching induced by each pulse (30 s in P. cruentum and 100 s in R. violacea). For this reason, in R. violacea, pulses spaced by 100 s of darkness seemed to have a greater effect than pulses spaced by 10 s of darkness. These results also suggest that it is not the formation of the proton gradient that limits the rate of quenching formation. A slower process after the pulse is required for the full occurrence of the quenching. In darkness the dissipation of quenching was very slow; it took up to 5 min in P. cruentum and up to 10 min in R. violacea.

As expected, under a large range of intensities and lengths, fluorescence quenching increased with the quanta absorbed by the cells. However, pulses of very different lengths (70 and 800 ms for the 3200 μmol photons m−2 s−1 pulses or 300 and 800 ms for the 300 μmol photons m−2 s−1 pulses) induced a similar Fm′ quenching. To explain this result, we propose that it takes more time to activate ATP synthase than to reduce the PQ pool. During the first period of illumination, corresponding mainly to PQ reduction, the ΔpH is efficiently formed by PSII and little is consumed. The time needed for the full reduction of the PQ pool depends on the light intensity of the pulse (70 ms for the 3200 μmol photons m−2 s−1 pulse and 300 ms for the 300 μmol photons m−2 s−1 pulse, see Fig. 5A). When the PQ pool becomes mostly reduced, the PSII activity and the proton translocation decrease, whereas the ATP synthase is activated. The fact that the decrease of Fv′ was slightly faster in the presence of DCCD than in its absence also suggests a small ATP synthase activity during the pulse (Fig. 6).

Our results suggest that the persistence of the fluorescence quenching in the dark corresponds to a low consumption of the ΔpH. As soon as the ΔpH was nullified, the maximal fluorescence was restored. In higher plants the activity of ATP synthase depends on the ΔpH and on the redox state of the thioredoxin (Vallejos et al., 1983; Junesch and Gräber, 1984; Mills and Mitchell, 1984): The reduced thioredoxin activates ATP synthesis by reduction of the γ-subunit of ATP synthase (Nalin and McCarty, 1984). We propose that the same is true in red algae. In dark-adapted cells the ATP synthase seems to be inactive; upon illumination it is activated and the rate of ΔpH consumption slowly increases. In the dark it rapidly becomes inactive. The accumulative effect of pulses can be explained by the very slow consumption of the ΔpH during the dark periods in red algae cells.

Cyclic electron transfer occurring under far-red light induced a pH gradient sufficiently large to generate fluorescence quenching even in the absence of white light pulses. However, this quenching was formed only in the presence of DCCD, an inhibitor of ATP synthase. In contrast, in the absence of DCCD, this quenching was not observed, suggesting that the consumption of the ΔpH was faster than its formation. Alternatively, it can be assumed that the formation of the NPQ is more sensitive to H+ domains localized around PSII than to the ΔpH across the membrane generated by cyclic electron transfer. Our results also suggest that far-red illumination maintained ATP synthase in an active state. Under far-red illumination, thioredoxin could be reduced via pseudolinear electron transfer allowed by the PQ reduction by a NAD(P)H-PQ oxidoreductase. In this case, the thioredoxin reduction and the pH gradient generated by cyclic electron transport could contribute to maintain ATP synthase activity. Moreover, the far-red-generated ΔpH seemed to be sufficient to maintain the activity of ATP synthase between the pulses. When the pulses were applied in the presence of far-red light, almost no fluorescence quenching was observed between the light pulses, indicating that the ΔpH was consumed (Fig. 6). This hypothesis was supported by the fact that in the presence of DCCD the fluorescence quenching developed.

The antagonistic effects of DCMU and DBMIB can be interpreted in terms of their effects on ΔpH but not in terms of their effects on the redox state of PQ. DCMU addition relaxed fluorescence quenching under illumination, whereas it had no effect in the presence of DCCD or in darkness. In the presence of DCMU and light, as was the case under far-red illumination, cyclic and pseudolinear electron transport via PSI were active. We propose that these conditions maintained ATP synthase activity, enabling a rapid ΔpH consumption and avoiding quenching formation or relaxing the quenching previously induced. Addition of DBMIB, which inhibited both cyclic and pseudolinear electron transport, suppressed the effect of far-red illumination. Since the presence of uncouplers annulled the effect of DBMIB, we conclude that this chemical indirectly decreased ATP synthase activity by inhibiting pseudolinear and cyclic electron transport.

It has been demonstrated previously that, in higher plants, DCCD, in addition to inhibiting the ATP synthase, inhibits the H+ release into the lumen following water splitting, hindering ΔpH (Jahns et al., 1988) and qE formation (Ruban et al., 1992b). These effects of DCCD are due to modifications of amino acids on LHCII polypeptides (Jahns et al., 1988; Ruban et al., 1992b; Walters et al., 1996). In red algae DCCD's effect on qE seems to be only related to the maintenance of a proton gradient by inhibition of the ATP synthase. Addition of uncouplers such as NH4Cl or nigericin annulled the effect of DCCD (data not shown). However, our results do not allow us to clearly distinguish between the effect on qE of a local concentration of H+ around PSII to that of a nonlocalized ΔpH across the membrane. We demonstrated that conditions favoring PSII activity (green and white light [Delphin et al., 1996; this article]) induce a ΔpH-dependent quenching, whereas under conditions favoring cyclic electron transfer (far-red illumination, presence of DCMU), no fluorescence quenching was observed in the absence of DCCD. These results favor the hypothesis involving a localized proton gradient around the PSII on the induction of qE in red algae.

Contrasting hypotheses have been put forward to explain the molecular mechanism of qE. In most studies in leaves and chloroplasts, a decrease of Fo′ has been associated with Fm′ quenching (Bilger and Schreiber, 1986; Rees et al., 1990; Walters and Horton, 1991; Gilmore and Yamamoto, 1992; Horton and Ruban, 1993). This feature reflects the energy de-excitation in the PSII antenna, which decreases the lifetime of excited Chls (Horton and Ruban, 1992; Walters and Horton, 1993; Horton et al., 1996). Another hypothesis for the mechanism of qE in higher plants is the energy dissipation in PSII reaction centers. It was proposed that the acidification of the thylakoid lumen provokes the release of Ca2+, inhibiting the electron donation to the reaction center II and resulting in quenching either through rapid-charge recombination or by the accumulation of a “quencher” such as P680+ (Weis and Berry, 1987; Krieger et al., 1992; Krieger and Weis, 1993). In red algae no change in the minimal fluorescence was detected under the different light regimes used (train of saturating pulses [this study], continuous low light 2, or near-saturating white light illumination [Delphin et al., 1996]), suggesting that PSII fluorescence quenching might occur in the reaction center and not in the antenna. Saturation curves of oxygen evolution also suggested that photon flux to the centers is similar in the absence or presence of quenching (Delphin et al., 1996). However, preliminary measurements of oxygen emission per flash in a Joliot-type electrode suggest that, under saturating light intensities, oxygen yield per flash and therefore the number of active PSII centers are not affected by fluorescence quenching. Further studies are necessary to elucidate the molecular mechanism of fluorescence quenching in red algae.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank G. Paresys and J.-P. Roux for their excellent computer and electronic assistance and for writing the computer software used in the pulsed-amplitude fluorimeter.

Abbreviations:

- Chl

chlorophyll

- DBMIB

2,5-dibromo-3-methyl-6-isopropyl-p-benzoquinone

- DCCD

N,N′-dicyclohexyl carbodiimide

- Fo

Fm, and Fv, initial, maximum, and variable Chl fluorescence in dark-adapted samples, respectively

- Fo′

Fm′, and Fv′, initial, maximum, and variable Chl fluorescence in illuminated samples, respectively

- LHCII

light-harvesting Chl a/b protein

- NPQ

nonphotochemical quenching

- Φo

fluorescence yield

- PQ

plastoquinone

- qE

energy-dependent quenching

- qP

photochemical quenching

Footnotes

This work was supported by a grant from the Société de Secours des Amis des Sciences to E.D.

LITERATURE CITED

- Allen JF. Protein phosphorylation in regulation of photosynthesis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1992;1098:275–335. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(09)91014-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen JF. Thylakoid protein phosphorylations, state 1-state 2 transitions, and photosystem stoichiometry adjustment: redox control at multiple levels of gene expression. Physiol Plant. 1995;93:196–205. [Google Scholar]

- Allen JF, Sanders CE, Holmes NG. Correlation of membrane protein phosphorylation with excitation energy distribution in the cyanobacterium Synechoccocus 6301. FEBS Lett. 1985;193:271–275. [Google Scholar]

- Arsalane W, Rousseau B, Duval J-C. Influence of the pool size of the xanthophyll cycle on the effect of a light stress in a diatom: competition between photoprotection and photoinhibition. Photochem Photobiol. 1994;60:237–243. [Google Scholar]

- Biggins J, Campbell CL, Bruce D. Mechanism of the light state transition in photosynthesis. II. Analysis of phosphorylated polypeptides in the red alga, Porphyridium cruentum. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1984;767:138–144. [Google Scholar]

- Bilger W, Bjökman O, Thayer SS. Light induced spectral absorbance changes in relation to photosynthesis and the epoxidation state of xanthophyll cycle component in cotton leaves. Plant Physiol. 1989;91:542–551. doi: 10.1104/pp.91.2.542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilger W, Schreiber U. Energy-dependent quenching of dark level chlorophyll fluorescence in intact leaves. Photosynth Res. 1986;10:303–308. doi: 10.1007/BF00118295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury M, Baker NR. A quantative determination of photochemical and non-photochemical quenching during the slow phase of the chlorophyll fluorescence induction curve of bean leaves. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1984;765:275–281. [Google Scholar]

- Briantais J-M, Vernotte C, Picaud M, Krause GH. Chlorophyll fluorescence as a probe for the determination of the photoinduced proton gradient in isolated chloroplasts. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1980;591:198–202. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(80)90233-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce D, Biggins J, Steiner T, Thewalt M. Mechanism of the light-state transition in photosynthesis. IV. Picosecond fluorescence spestroscopy of Anacystis nidulans and Porphyridium cruentum in state 1 and state 2 at 77 K. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1985;806:237–246. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell D, Öquist G. Predicting light acclimatation in cyanobacteria from non-photochemical quenching of PSII fluorescence, which reflects state transitions in these organisms. Plant Physiol. 1996;111:1293–1298. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.4.1293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delphin E, Duval J-C, Etienne A-L, Kirilowsky D. State transitions or ΔpH-dependant quenching of photosystem II fluorescence in red algae. Biochemistry. 1996;35:9435–9445. doi: 10.1021/bi960528+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delphin E, Duval J-C, Kirilovsky D. Comparison of state 1-state 2 transitions in the green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii and in the red alga Rhodella violacea: effect of kinase and phosphatase inhibitors. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1995;1232:91–95. [Google Scholar]

- Demmig B, Winter K. Characterization of three components of non-photochemical fluorescence quenching and their response to photoinhibition. Aust J Plant Physiol. 1988;15:163–178. [Google Scholar]

- Demmig B, Winter K, Kruger A, Czygan F-C. Photoinhibition and zeaxanthin formation in intact leaves. A possible role of the xanthophyll cycle in the dissipation of excess light energy. Plant Physiol. 1987;84:218–224. doi: 10.1104/pp.84.2.218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demmig-Adams B. Carotenoids and photoprotection in plants: a role for the xanthophyll zeaxanthin. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1990;1020:1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Duysens LMN, Sweers HE (1963) Mechanism of the two photochemical reactions in algae as studied by means of fluorescence. In Japan Society of Plant Physiology, Studies on Microalgae and Photosynthetic Bacteria. Tokyo University, Tokyo Press, Japan, pp 353–372

- Gilmore AM, Yamamoto HY. Zeaxanthin formation and energy-dependent fluorescence quenching in pea chloroplasts under artificially mediated linear and cyclic electron transport. Plant Physiol. 1991;96:635–643. doi: 10.1104/pp.96.2.635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore AM, Yamamoto HY. Dark induction of zeaxanthin-dependent nonphotochemical quenching mediated by ATP. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:1899–1903. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.5.1899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haworth P, Kyle DJ, Horton P, Arntzen CJ. Chloroplast membrane protein phosphorylation. Photochem Photobiol. 1982;36:743–748. [Google Scholar]

- Horton P, Hague A. Studies on the induction of chlorophyll fluorescence in isolated barley protoplasts. IV. Resolution of non-photochemical quenching. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1988;932:107–115. [Google Scholar]

- Horton P, Ruban AV. Regulation of photosystem II. Photosynth Res. 1992;34:375–385. doi: 10.1007/BF00029812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton P, Ruban AV. ΔpH-dependent quenching of the Fo level of chlorophyll fluorescence in spinach leaves. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1993;1142:203–206. [Google Scholar]

- Horton P, Ruban AV, Rees D, Pascal AA, Noctor G, Young AJ. Control of the light-harvesting function of chloroplasts membranes by aggregation of the LHCII chlorophyll-protein complex. FEBS Lett. 1991;292:1–4. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(91)80819-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton P, Ruban AV, Walters RG. Regulation of light harvesting in green plants. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1996;47:655–684. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.47.1.655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahns P, Polle A, Junge W. The photosynthetic water oxidase: its proton pumping activity is short circuited within the protein by DCCD. EMBO J. 1988;7:589–594. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb02851.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones RF, Spear HL, Kurry W. Physiol Plant. 1963;16:636–643. [Google Scholar]

- Junesh U, Gräber P (1984) The rate of ATP synthesis as function of ΔpH and Δψ in preactivated and non-preactivated chloroplasts. In C Sybesma, ed, Advances in Photosynthesis Research, Vol II. Martinus Nijhoff/Dr W. Junk Publishers, Dordrecht, The Netherlands, pp 431–436

- Krause GH. The high-energy state of the thylakoid system as indicated by chlorophyll fluorescence and chloroplast shrinkage. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1973;292:715–728. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(73)90019-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause GH, Vernotte C, Briantais J-M. Photo-induced quenching of chlorophyll fluorescence in intact chloroplasts and algae: resolution in two components. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1982;679:116–124. [Google Scholar]

- Krause GH, Weiss E. Chlorophyll fluorescence and photosynthesis: the basics. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1991;42:313–349. [Google Scholar]

- Krieger A, Moya I, Weiss E. Energy-dependent quenching of chlorophyll a fluorescence: effect of pH on stationary fluorescence and picosecond-relaxation kinetics in thylakoid membranes and photosystem II preparations. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1992;1102:167–176. [Google Scholar]

- Krieger A, Weiss E. The role of calcium in the pH-dependent control of photosystem II. Photosynth Res. 1993;37:117–130. doi: 10.1007/BF02187470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CB, Rees D, Horton P. Non-photochemical quenching of chlorophyll fluorescence in the green alga Dunaliella. Photosynth Res. 1990;24:167–173. doi: 10.1007/BF00032596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ley AC, Butler WL. Energy distribution in the photochemical apparatus of Porphyridium cruentum in state I and state II. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1980;592:349–363. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(80)90195-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lokstein H, Härtel H, Hoffmann P, Renger G. Comparison of chlorophyll fluorescence quenching in leaves of wild-type with a chlorophyll-b-less mutant of barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) J Photochem Photobiol B Biol. 1993;19:217–225. [Google Scholar]

- Mills JD, Mitchell P. Thiol modulation of the chloroplast proton motive ATPase and its effect on photophosphorylation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1984;764:93–104. [Google Scholar]

- Nalin CM, McCarty RE. Role of a disulfide bond in the γ subunit inactivation of the ATPase of chloroplast coupling factor 1. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:7275–7280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noctor G, Rees D, Young A, Horton P. The relationship between zeaxanthin, energy-dependent quenching of chlorophyll fluorescence and the transthylakoid pH-gradient in isolated chloroplasts. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1991;1057:320–330. [Google Scholar]

- Olive J, M'Bina I, Vernotte C, Astier C, Wollman F-A. Randomization of the EF particles in thylakoid membranes of Synechocystis 6714 upon transition from state I to state II. FEBS Lett. 1986;208:308–312. [Google Scholar]

- Quick WP, Stitt M. An examination of factors contributing to non-photochemical quenching of chlorophyll fluorescence in barley leaves. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1989;977:287–296. [Google Scholar]

- Rees D, Noctor G, Horton P. The effect of high-energy-state excitation quenching on maximum and dark level chlorophyll fluorescence yield. Photosynth Res. 1990;25:199–212. doi: 10.1007/BF00033161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renger G, Schreiber U (1986) Practical applications of fluorometric methods to algae and higher plant research. In Govindjee, J Amez, DC Fork, eds, Light Emission by Plants and Bacteria. Academic Press, New York, pp 587–619

- Ruban AV, Rees D, Pascal AA, Horton P. and qE in isolated thylakoids Biochim Biophys Acta. 1992a;1102:39–44. [Google Scholar]

- Ruban AV, Walters RG, Horton P. The molecular mechanism of the control of excitation energy dissipation in chloroplast membranes. FEBS Lett. 1992b;309:175–179. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(92)81089-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruban AV, Young AJ, Horton P. Induction of non-photochemical energy dissipation and absorbance changes in the state of the light harvesting system of photosystem II in vivo. Plant Physiol. 1993;102:741–750. doi: 10.1104/pp.102.3.741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders CE, Allen JF (1987) The 18,5 kDa phosphoprotein of Synechococcus 6301: a component of the phycobilisome. In J Biggins, ed, Progress in Photosynthesis Research. Martinus Nijhoff/Dr W. Junk Publishers, Dordrecht, The Netherlands, pp 761–764

- Sanders CE, Allen JF. Effecs of divalent cations on 77 K fluorescence emission and on membrane protein phosphorylation in isolated thylakoids of the cyanobacterium Synechococcus 6301. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1988;934:87–95. [Google Scholar]

- Satoh K, Fork DC. A new mechanism for adaptation to changes in light intensity and quality in the red alga, Porphyra perforata. I. Relation to state 1-state 2 transitions. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1983;722:190–196. doi: 10.1007/BF00041801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber U, Endo T, Hualing M, Asada K. Quenching analysis of chlorophyll fluorescence by the saturation pulse method: particular aspects relating to study of eukaryotic algae and cyanobacteria. Plant Cell Physiol. 1995;36:873–882. [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber U, Schliwa U, Bilger W. Continuous recording of photochemical and non-photochemical chlorophyll fluorescence quenching with a new type of modulation fluorimeter. Photosynth Res. 1986;10:51–62. doi: 10.1007/BF00024185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallejos RH, Arana JL, Ravizzini Changes in activity and structure of chloroplast proton ATPase induced by illumination of spinach leaves. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:7317–7321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Gorkom HJ. Identification of the reduced primary electron acceptor of photosystem II as a bound semiquinone anion. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1974;347:439–442. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(74)90081-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vernotte C, Astier C, Olive J. State 1-state 2 adaptation in the cyanobacteria Synechocystis PCC 6714 wild type and Synechocystis PCC 6803 wild type and phycocyanin-less mutant. Photosynth Res. 1990;26:203–212. doi: 10.1007/BF00033133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vernotte C, Etienne A-L, Briantais J-M. Quenching of the photosystem II chlorophyll fluorescence by the plastoquinone pool. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1979;545:519–527. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(79)90160-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters RG, Horton P. Resolution of non photochemical chlorophyll fluorescence quenching in barley leaves. Photosynth Res. 1991;27:121–133. doi: 10.1007/BF00033251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters RG, Horton P. Theoretical assessment of alternative mechanisms for nonphotochemical quenching of PSII fluorescence in barley leaves. Photosynth Res. 1993;36:119–139. doi: 10.1007/BF00016277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters RG, Ruban AV, Horton P. Identification of proton-active residues in a higher plant light-harvesting complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:14204–14209. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.24.14204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weis E, Berry JA. Quantum efficiency of PS2 in relation to “energy” dependent quenching of chlorophyll fluorescence. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1987;894:198–208. [Google Scholar]

- Williams WP, Allen JF. State 1-state 2 changes in higher plants and algae. Photosynth Res. 1987;13:19–45. doi: 10.1007/BF00032263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]