ABSTRACT

Purpose: This study describes the health-related quality of life (HRQOL) of Australians living with Parkinson disease (PD) and compares the findings to international reports. Methods: The Parkinson's Disease Questionnaire-39 (PDQ-39) was used to measure HRQOL in 210 individuals with PD living in Australia. In parallel, a tailored literature search identified previous studies on HROQL in people with PD. A quantitative meta-analysis with a random-effects model was used to compare the HRQOL of individuals with PD living in Australia and other countries. Results: The mean PDQ-39 summary index (SI) score for this sample of Australians with PD was 20.9 (SD 12.7). Ratings for the dimension of social support and stigma were significantly lower than ratings for bodily discomfort, mobility, activities of daily living, cognition, and emotional well-being. Comparing the Australian and international PD samples revealed a significant heterogeneity in overall HRQOL (I2=97%). The mean PDQ-39 SI scores for Australians were lower, indicating better HRQOL relative to samples from other countries. Conclusions: This Australian sample with PD perceived their HRQOL as poor, although it was less severely compromised than that of international samples. While further research is required, these findings can inform the clinical decision-making processes of physiotherapists.

Key Words: Australia, meta-analysis, Parkinson disease, quality of life

RÉSUMÉ

Objectif : Cette étude décrit la qualité de vie liée à la santé (QDVS) des Australiens qui vivent avec la maladie de Parkinson (MP) et elle compare les diverses conclusions de rapports internationaux. Méthode : Le questionnaire sur la maladie de Parkinson-39 (Parkinson's Disease Questionnaire-39, ou PDQ-39) a été utilisé pour mesurer la qualité de vie de 210 personnes aux prises avec la maladie de Parkinson et vivant en Australie. Parallèlement, une recherche documentaire sur mesure a permis de trouver les études déjà réalisées sur la QVDS des personnes aux prises avec cette maladie. Une méta-analyse quantitative avec modèle à effets aléatoires a été utilisée pour comparer la QVDS des individus aux prises avec la maladie de Parkinson qui vivent en Australie ou ailleurs. Résultats : La moyenne de l'indice global du PDQ-39 pour cet échantillon d'Australiens atteints de la maladie de Parkinson était de 20,9 (écart-type de 12,7). Les cotes en ce qui concerne le soutien social et la discrimination étaient considérablement plus faibles que celles touchant l'inconfort physique, la mobilité, les activités de la vie quotidienne, la cognition et le bien-être affectif. La comparaison entre les échantillons de malades australiens et ceux d'ailleurs dans le monde a révélé une hétérogénéité considérable dans la QVDS globale (I2=97%). La moyenne des IS du PDQ-39 pour les Australiens était moins élevée, ce qui indique une meilleure QVDS pour les échantillons des autres pays. Conclusions : Dans cet échantillon australien, les personnes aux prises avec la maladie de Parkinson percevaient leur QVDS comme mauvaise, bien que celle-ci ait été beaucoup moins gravement compromise que chez les personnes des échantillons internationaux. Des recherches supplémentaires seraient nécessaires, mais ces constatations peuvent tout de même contribuer au processus de prise de décision des physiothérapeutes.

Mots clés : Australie, maladie de Parkinson, méta-analyse, physiothérapie, qualité de vie

The term health-related quality of life (HRQOL) refers to the health dimension of quality of life (QOL) and is concerned with the impact of health, disease, and treatment on physical mobility, social and emotional well-being, and cognition.1 Despite the growing literature on HRQOL in people with Parkinson disease (PD), there are limited published data on Australians. Previous studies have mainly reported samples from Europe, North and South America, and Asia.2–4 International findings are not necessarily applicable to Australia, since HRQOL varies according to cultural norms and value systems.5 For example, financial security is highly valued in some cultures, and the inability to work because of mobility restrictions may contribute to the perception of reduced QOL. The stigma associated with the visible disability of tremors and dyskinesias has also been shown to correlate with poor HRQOL in other cultures.6 There is thus a need to examine how Australians with PD perceive their own HRQOL, as well as how this perception compares with those of international samples. This information can be used to optimize the assessment and clinical decision-making processes of physiotherapists working with the Australian PD population.

Measures of health status or health utility are typically used to assess HRQOL in people with PD.5 Measures of health status focus on the impact of health on functional ability; this category includes both generic and disease-specific instruments. Measures of health utility assess how much an individual values his or her health and can be used for both unimpaired and impaired people.5 Generic measures may not adequately examine issues associated with a particular condition—for example, difficulties with writing or communication in individuals with PD7—and disease-specific instruments are therefore considered most relevant to these individuals. Our study aims to describe and quantify the HRQOL of a sample of Australians with PD using the Parkinson's Disease Questionnaire-39 (PDQ-39);7 a disease-specific health status instrument. We also compare and contrast the HRQOL of this Australian sample to values reported in the literature from other countries.

METHODS

Participants and procedures

Data from individuals with idiopathic PD from an existing therapy trial were included in this investigation.8 This trial investigated the efficacy of two physiotherapy interventions (movement strategy training and progressive resistive strength training) on reducing falls and improving mobility in people with PD. The therapy sessions were conducted in an outpatient setting for 2 hours, once per week, for 8 consecutive weeks.8 Participants were recruited from different sources and sites in metropolitan Melbourne, Australia, such as movement disorder clinics, outpatient rehabilitation programs, and PD support groups. Individuals were included if they had a diagnosis of idiopathic PD confirmed by a neurologist, were able to provide informed consent, and were able to walk and safely participate in an exercise program.8 Individuals who scored <24 on the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE), adjusted for age, were excluded,9 as they were not able to provide informed consent. Participants were also excluded if they had a disease severity of stage 5, according to the modified Hoehn and Yahr (HY) scale,10 as they could not complete the assessment protocol. Ethics approval was obtained from The University of Melbourne's Health Sciences Human Ethics Sub-Committee (HREC 0828579.3).

Structured interviews were used to standardize the collection of demographic characteristics, such as age and comorbidities, and to administer the HRQOL questionnaire. Clinical assessment using the Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS)11 and the modified HY scale10 was also undertaken to measure the severity and disability associated with PD. The UPDRS is a clinical test of motor impairment and disability with evidence of internal consistency, face validity, and convergent validity, and it has been used extensively in PD.12

The PDQ-397 was used to quantify HRQOL because it is widely used13–17 and highly reliable.7 A recent systematic review examining the factors that predicted HRQOL in people with PD found that the PDQ-39 was the most frequently reported disease-specific tool.18 The PDQ-39 correlates strongly with clinical measures such as the modified HY scale.19,20 There is also evidence supporting its content, construct, and discriminative validity in different cultural populations.21,22 We therefore considered the PDQ-39 a suitable instrument to determine how the HRQOL of Australians with PD compares to samples from other countries. The PDQ-39 contains 39 items across 8 different dimensions of health; summary indices can be calculated for each dimension, as well as for the overall scale. Lower scores indicate better perceived HRQOL.7

International PD studies

An electronic literature search was conducted in August 2010 to identify previous studies that examined the HRQOL of people with PD using the PDQ-39, using six online medical and health databases: Medline (from 1960), Cumulated Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) (from 1982), Web of Science (from 1960), PsychINFO (from 1960), EMBASE (from 1966), and Scopus (from 1960). Keywords in the tailored search strategy included “Parkinson's disease,” “quality of life,” “health status,” “life satisfaction,” and “PDQ-39.” Appropriate keywords related to these terms were selected using search tools provided by each database. Terms were also mapped to medical subject headings, where relevant, and exploded to include all subheadings and related terms. In addition, a manual search of reference lists from retrieved studies was undertaken to identify studies that were not found through the electronic search.

The titles and abstracts retrieved from the initial search were evaluated for eligibility by a single reviewer (SS). Full-length articles were eligible for inclusion if they satisfied the following criteria: (1) examined the HRQOL of people with PD, using the PDQ-39, and reported the means and standard deviations of the overall summary index (SI) and each dimension for the total sample; (2) were full papers published in English; and (3) included more than 50 individuals with idiopathic PD from a single country.

Published data from the selected studies were used to compare the HRQOL of our Australian PD sample to samples from other countries. The means and standard deviations of the overall SI and each dimension of the PDQ-39 were extracted by a reviewer (SS), and the data extracted were then verified independently by a second reviewer (JM) to ensure their accuracy.23 Data from multiple reports of a single study were extracted separately and collated.14,24 For longitudinal, intervention, and randomized controlled trials, only the baseline data were extracted.25–27 Details of the study design, participant characteristics, and recruitment procedures were also recorded. In the case of two reports, the authors were contacted to confirm the required information.3,16

Statistical analysis

The PDQ-39 was used to assess HRQOL because this study aimed to examine how Australians with PD perceived their QOL. The PDQ-39 SI was computed for the scale to provide an indication of overall HRQOL. Summary scores were also calculated for each dimension according to published algorithms.7 Data missing from the PDQ-39 were imputed with the dimension scores, using the Expectation-Maximization computational algorithm.28 The distribution of scores from the PDQ-39 was inspected for normality before analysis. A one-way repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare ratings for the eight dimensions of HRQOL, with Bonferroni adjustment for multiple comparisons (p<0.002). Pearson's correlation coefficients and independent t-tests were also used to determine associations between HRQOL and demographic characteristics such as age, disease duration, and disease severity.

In parallel, a meta-analysis of the means and standard deviations of HRQOL was performed to determine the comparability of ratings between Australians with PD and individuals with PD from other countries. Heterogeneity was evaluated using the χ2 and I2 statistics. To account for differences in studies due to heterogeneity, a random-effects model was used to combine estimates from the studies. To compare the HRQOL of Australians with PD and people with PD from other countries, 95% CIs were constructed around the estimates. Secondary subgroup analyses were undertaken by combining the studies into five regions: North America,3,27 South America,12,14,15,24,29,30 Western Europe,2,13,16,25,26,31–34 Eastern Europe,17,35,36 and Asia–Pacific.4,21,22,37–41 The ratings for each dimension of HRQOL by people with PD living in Australia and other countries were also examined to determine the comparability of these estimates. Statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, version 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL), and the RevMan 5.0 meta-analysis program (Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, UK).

RESULTS

Australian sample characteristics

A total of 210 individuals (140 male, 70 female) with idiopathic PD, living in metropolitan Melbourne, completed the PDQ-39 questionnaire. They ranged in age from 44 to 89 years (mean 67.9; SD 9.6); with a mean (SD) disease duration of 6.7 (SD 5.6) years. Most participants lived with another person (77.1%), were no longer working (85.2%), and were taking levodopa either in mono-therapy or combination therapy (89%). The median HY stage was 2.5 (range 0–4) and the mean UPDRS-II score was 11.5 (5.9). Three participants (1%) reported that they did not have any other health conditions or disorders apart from PD. The three most commonly self-reported comorbid health conditions were fractures, pain, and dizziness.

HRQOL ratings in Australians with PD

Ten participants had data missing for a single item in the PDQ-39, resulting in a loss of <0.2% of data. The mean PDQ-39 SI score for the Australian sample with mild to moderate disease was 20.9 (SD 12.7). Participants reported having the most difficulties in the dimensions of bodily discomfort, mobility, activities of daily living, cognition, emotional well-being, and communication. They had lesser concerns with the dimensions related to stigma and social support (see Table 1).

Table 1.

HRQOL as Measured by the PDQ-39 for Australians with PD (n=210)

| Scores |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| HRQOL | Mean (SD) | Range | 95% CI |

| PDQ-39 SI | 20.9 (12.7) | 0–62 | (19.2–22.6) |

| Dimensions of PDQ-39 | |||

| Mobility | 26.4 (24.2) | 0–100 | (23.1–29.7) |

| Activities of daily living | 24.9 (20.9) | 0–100 | (22.0–27.7) |

| Emotional well-being | 20.2 (15.9) | 0–79 | (18.0–22.4) |

| Stigma | 15.2 (18.1) | 0–88 | (12.7–17.6) |

| Social support | 9.6 (15.3) | 0–83 | (7.5–11.7) |

| Cognition | 23.2 (18.1) | 0–75 | (20.8–25.7) |

| Communication | 20.1 (21.0) | 0–100 | (17.2–22.9) |

| Bodily discomfort | 27.7 (21.3) | 0–83 | (24.8–30.6) |

HRQOL=health-related quality of life; PD=Parkinson disease; PDQ-39=Parkinson's Disease Questionnaire-39; SI=summary index.

A one-way repeated-measures ANOVA was conducted to compare ratings for the eight dimensions of HRQOL. The results revealed significant differences in HRQOL ratings for each dimension (Wilks' λ=0.49, F7,203=28.09, p<0.001, multivariate partial η2=0.49). Post hoc pair-wise Bonferroni corrected comparisons revealed that the rating for social support was significantly lower than for all other dimensions (p<0.001) with the exception of stigma (p=0.003). The rating for stigma was also significantly lower than ratings for bodily discomfort, mobility, activities of daily living, cognition, and emotional well-being (p<0.001).

There was a significant and positive correlation between disease duration and HRQOL: longer disease duration was associated with poorer life quality (p<0.001). There was also a statistically significant difference in HRQOL between individuals with mild and those with moderate disease severity (p<0.001). Individuals with moderate disease severity (modified HY stage ≥2.5) recorded a higher mean PDQ-39 SI score, indicating poorer HRQOL. The association between HRQOL, as measured by the PDQ-39 SI, and age, however, was not significant. Similarly, no significant difference in PDQ-39 SI scores was observed between men and women. There was also no difference between individuals with comorbidities and those who did not have any other health condition apart from PD (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Pearson Correlations and Independent t-test Results between HRQOL and Demographic Characteristics for Australians with PD

| Demographic characteristic | PDQ-39 SI; mean (SD) | r | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | — | −0.04 | 0.58 |

| PD duration, y | — | 0.37 | <0.001* |

| Sex | — | — | 0.48 |

| Male | 21.4 (12.7) | — | — |

| Female | 20.0 (12.9) | — | — |

| Disease severity | — | — | <0.001* |

| Mild (HY Stages ≤2) | 17.0 (11.2) | — | — |

| Moderate (HY Stages ≥2.5) | 23.9 (13.1) | — | — |

| Comorbidities | — | — | 0.82 |

| Yes | 20.9 (12.8) | — | — |

| No | 22.5 (10.6) | — | — |

Significant at p<0.001.

HRQOL=health-related quality of life; PD=Parkinson disease; PDQ-39=Parkinson's Disease Questionnaire; SI=summary index; HY=Hoehn and Yahr.

International PD studies

The literature search yielded 872 published articles. After removing duplicates and reviewing the titles and abstracts we determined that 196 were suitable for further consideration. By applying pre-defined inclusion and exclusion criteria we identified 28 full-text reports for inclusion. Details of these 28 studies are provided in Table 3, together with our unpublished Australian data.

Table 3.

Descriptive Summary of Characteristics of International PD Studies

| Study design |

Participant characteristics |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study by region | Country of origin |

Source of participants |

Recruitment method |

n | Mean age, y (range) |

M:F | Mean HY stage (range) |

Mean UPDRS-II (SD) |

Mean disease duration, y (range) |

Levodopa therapy; No. (%) |

Mean PDQ-39 SI (SD) |

| North America | |||||||||||

| Brown et al. (2009)3 | USA | MDC | Convenience | 96 | 71.6 | 5.4:1 | NS | 14.5 (7.6) | NS | NS | 28.6 (18.0) |

| Tickle-Degnen et al. (2010)27 | USA | MDC | NS | 117 | 66.3 | 2.3:1 | (II–III) | NS | 7.1 | 94 (80) | 31.7 (11.1) |

| South America | |||||||||||

| Carod-Artal et al. (2010)29 | Brazil | Hospital | Consecutive | 150 | 63.1 | 1.3:1 | (I–V) | NS | 8.7 | 130 (87) | 35.4 (18.4) |

| Carod-Artal et al. (2008)15 | Brazil | NC | Consecutive | 115 | 62.5 | 1.3:1 | (I–V) | NS | 8.7 | 81 (71) | 45.0 (17.5) |

| Carod-Artal et al.(2007)14,24* | Brazil | NC/hospital | Consecutive | 144 | 61.9 | 1.1:1 | (I–IV) | 12.1 (7.1) | 6.6 | 126 (88) | 40.7 (17.8) |

| Martinez-Martin et al. (2007)30 | Ecuador | MDC | Random | 187 | 68.9 (44–96) | 2.0:1 | 2.4† (I–IV) | 19.9 (9.5) | 6.0 (1–15) | NS | 41.8 (16.3) |

| Martinez-Martin et al. (2005)12 | Ecuador | MDC | Random | 137 | 69.4 (44–92) | 2.2:1 | (I–V) | 19.7 (10.0) | 5.9 (1–15) | 137 (73) | 41.5 (15.5) |

| Western Europe | |||||||||||

| Chapuis et al. (2005)31 | France | NS | NS | 143 | 67.1 (44–90) | 1.0:1 | 2.0 (0–V) | NS | 9.1 (1–26) | 122 (85) | 36.5 (14.2) |

| Montel et al. (2009)2 | France | Hospital | NS | 135 | 60.6 | 1.5:1 | 1.9 | 13.2 (10.8) | 4.9 | NS | 35.1 (23.1) |

| Gomez-Esteban et al. (2007)16 | Spain | NS | NS | 110 | 68.6 | 0.9:1 | NS | 13.4 (5.8) | 7.6 | 88 (80) | 26.4 (13.3) |

| Gray et al. (2002)25 | UK | Hospital | Consecutive | 97 | 65.0 (48–83) | 1.5:1 | NS | NS | NS | NS | 39.0 (15.0) |

| Schrag et al. (2000)13 | UK | Community | Population | 97 | 73.0 (36–94) | 1.1:1 | 2.4 (I–V) | NS | 5.8 (0–25) | NS | 30.0 (19.3) |

| Haapaniemi et al. (2004)32 | Finland | NC | Consecutive | 259 | 66.5 | 1.1:1 | 2.1† (0–IV) | 10.2 (6.5) | 4.3 | NS | 31.6 (15.8) |

| Herlofson and Larsen (2003)33 | Norway | Hospital | NS | 66 | 70.8 | 0.6:1 | 2.5 | 11.3 (6.5) | 5.9 | NS | 18.7 (12.0) |

| Krikmann et al. (2008)34 | Estonia | NC | NS | 81 | 66.9 | 0.5:1 | (I–V) | NS | 8.9 | 74 (91) | 39.0 (17.7) |

| Reuther et al. (2007)26 | Germany | NC/community | Consecutive | 145 | 67.3 (37–94) | 2.0:1 | 2.8 | 12.9 (10.4) | 9.3 (1–36) | NS | 29.4 (17.5) |

| Eastern Europe | |||||||||||

| Dubayova et al. (2009)35 | Slovak Republic | NC/hospital | NS | 153 | 67.9 (44–83) | 1.1:1 | NS | NS | 7.5 (0–34) | NS | 58.9 (17.0) |

| Zach et al. (2004)17 | Poland | MDC | NS | 141 | 68.1 (41–92) | 1.2:1 | (II–III) | NS | 11.9 (5–34) | 141 (100) | 35.3 (15.7) |

| Ziropada et al. (2009)36 | Serbia | NC | Consecutive | 102 | 58.4 | 1.2:1 | 1.8† (I–IV) | NS | 4.8 | NS | 45.8 (13.3) |

| Asia-Pacific | |||||||||||

| Tan et al. (2004)21 | Singapore | MDC/community | NS | 88 | 63.1 (38–82) | 2.4:1 | NS | NS | NS | NS | 31.2 (14.9) |

| Luo et al. (2005)37 | Singapore | MDC/community | Convenience | 63 | 65.0 (41–82) | 1.4:1 | NS | NS | NS | NS | 21.7 (14.7) |

| Luo et al. (2010)38 | China | NC | NS | 71 | 63.7 (32–84) | 1.6:1 | (I–V) | 15.0 (7.7) | 6.0 (1–20) | NS | 29.6 (17.4) |

| Tsang et al. (2002)22 | China | MDC | NS | 54 | 66.4 (42–82) | 1.3:1 | (I–IV) | NS | NS | NS | 29.5 (21.5) |

| Moore et al. (2007)40 | Israel | MDC | Consecutive | 118 | 65.8 | 1.3:1 | 2.7‡ | NS | 5.8 | NS | 33.2 (9.4) |

| Moore et al. (2005)40 | Israel | MDC | Consecutive | 124 | 65.8 (38–85) | 1.3:1 | 2.7‡ (I–V) | NS | 5.8 (2–29) | NS | 31.3 (10.0) |

| Nojomi et al. (2010)41 | Iran | NC | Consecutive | 200 | 57.3 (27–83) | 2.1:1 | (I–V) | NS | 6.5 | NS | 35.1 (15.4) |

| Suzukamo et al. (2006)4 | Japan | NC | Convenience | 183 | 65.8 | 0.7:1 | (0–IV) | NS | NS | NS | 29.5 (17.0) |

| CURRENT STUDY | Australia | MDC/community | Convenience | 210 | 67.9 (44–89) | 2.0:1 | 2.5 (0–IV) | 11.5 (5.9) | 6.7 (0–30) | 187 (89) | 20.9 (12.7) |

Multiple reports of the same study.

Mean values calculated from raw scores.

HY scores reported for off-medication state.

PD=Parkinson disease; HY=Hoehn and Yahr; UPDRS-II=Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale Part II; PDQ-39=Parkinson's Disease Questionnaire; MDC=movement disorder clinic; NC=neurology clinic; NS=not stated.

The mean of the reported mean ages of participants was 65.7 (range 57–73). Most participants had mild to moderate PD, with a mean HY stage of 2.3 (range 0–5) in the medication “on” phase, a mean UPDRS-II score of 16.7 (range 10–20), and a mean disease duration of 7.1 years (range 4–12). Nine studies included individuals with HY stage 5 within their samples.12,13,15,29,31,34,38,39,41 Sufficient information regarding the proportion of participants in the different HY stages was provided by seven of these studies,12,13,15,29,34,38,41 and in these investigations individuals with HY stage 5 made up less than 5% of the total sample. Thus, the disease severity of participants with PD in other countries was comparable to that observed in our Australian sample.

In studies with available socio-demographic data, the majority of participants were taking levodopa (range 71%–100%) and lived with others (range 83%–97%). Only a small proportion of participants, however, were still working (range 4%–37%). The sample size, reported mean values of UPDRS-II scores, and disease duration varied across studies.

HRQOL of people with PD living in Australia and other countries

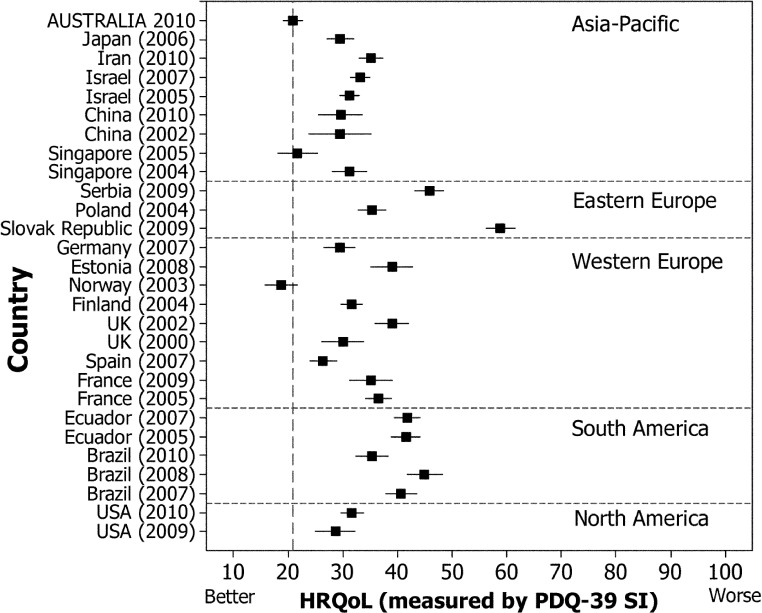

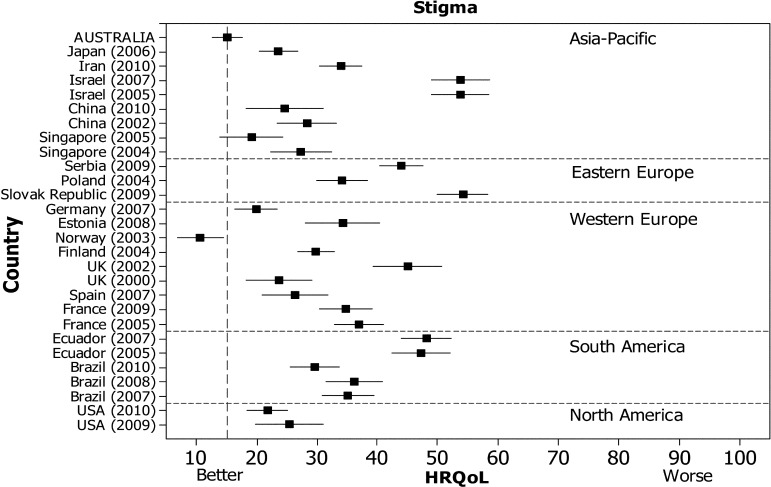

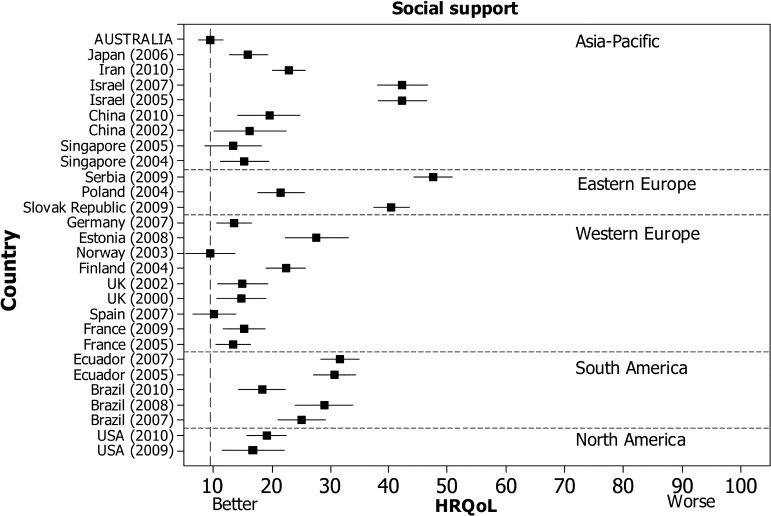

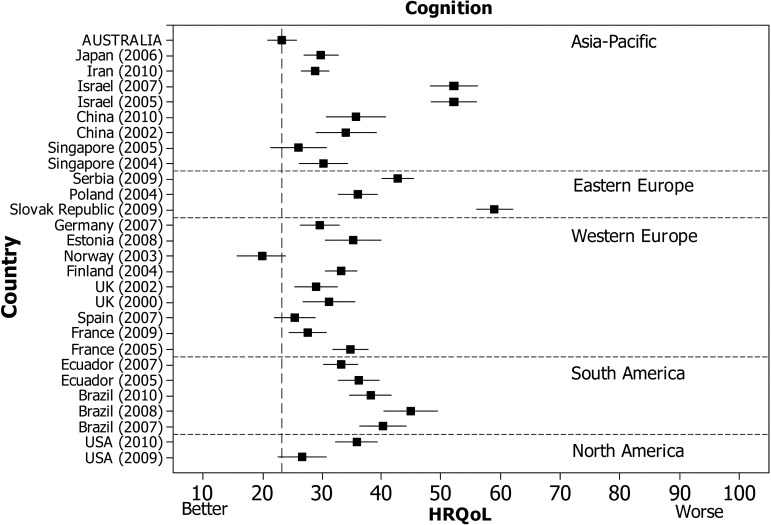

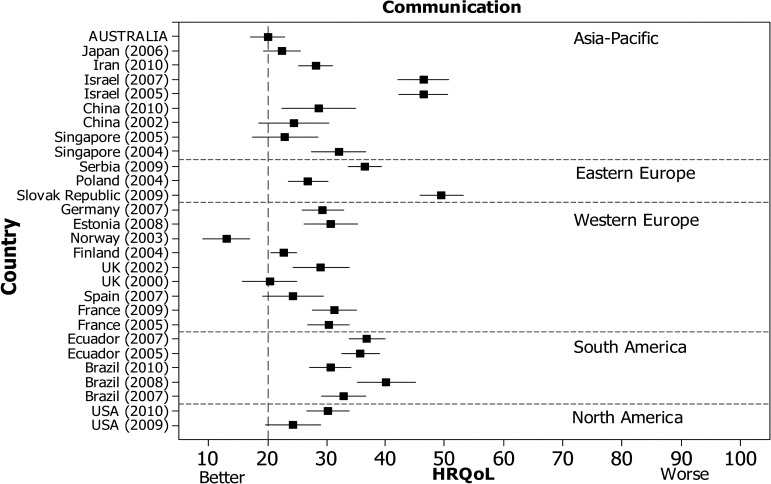

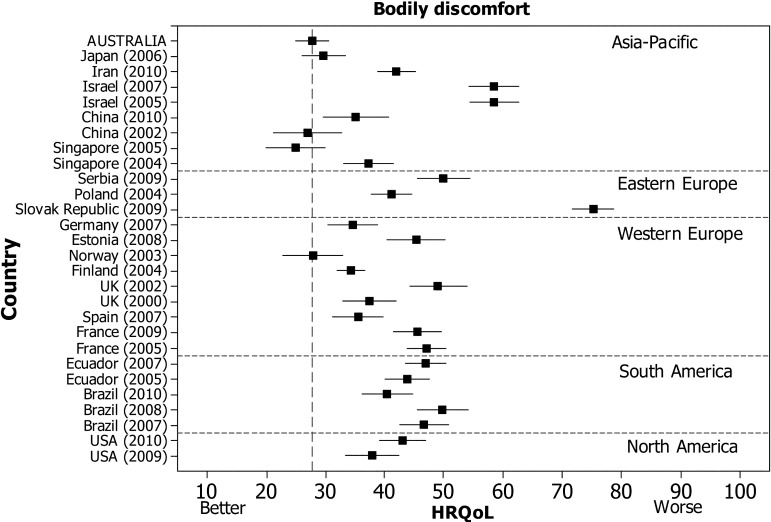

From the included studies, individuals with PD living in North American, South American, European, and Asian countries were identified (see Table 3). The 95% CIs around the estimates of overall HRQOL for people with PD living in Australia and in these countries are shown in Figure 1, which illustrates the wide variability in overall HRQOL across this sample of studies. The χ2 test of heterogeneity among the studies was statistically significant (p<0.001) and the I2 statistical test yielded a value of 97% (see Table 4). Inspection of CIs around the mean in Figure 1 provides an indication of whether there were differences in overall HRQOL between the studies. When the CIs around HRQOL overlap, a difference might not exist. This was evident in comparisons between the Australian PD sample and the Norway33 and Singapore37 samples. The width of the intervals in Figure 1 also demonstrates the precision in the estimation of overall HRQOL for each study. A wide CI around HRQOL, as observed for PD samples from China,22,38 France,2 the United Kingdom,13 Germany,26 and Singapore,37 indicates that the estimate is less precise because of smaller sample sizes and larger variance.42

Figure 1.

Mean and 95% CIs of overall HRQOL as measured by the PDQ-39 summary index for people with PD living in Australia and other countries, stratified by region.

Table 4.

Pooled Estimates and Heterogeneity Values of the Mean PDQ-39 SI and Mean Values for Each Dimension

| HRQOL | Pooled estimate of mean values (95% CI) |

Test of heterogeneity |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| χ2 test, p-value | I2 test, % | ||

| PDQ-39 SI (all studies) | 34.0 (31.0–37.1) | <0.001 | 97 |

| PDQ-39 SI (by regions) | |||

| North America | 28.1 (23.3–39.9) | 0.14 | 54 |

| South America | 40.9 (38.1–43.7) | <0.001 | 81 |

| Western Europe | 31.7 (27.6–35.8) | <0.001 | 95 |

| Eastern Europe | 46.7 (33.4–60.0) | <0.001 | 99 |

| Asia–Pacific | 29.2 (25.5–32.8) | <0.001 | 95 |

| Dimensions of PDQ-39 (all studies) | |||

| Mobility | 43.1 (39.3–47.0) | <0.001 | 96 |

| Activities of daily living | 40.3 (36.2–44.3) | <0.001 | 96 |

| Emotional well-being | 36.7 (32.3–41.1) | <0.001 | 98 |

| Stigma | 32.0 (27.5–36.6) | <0.001 | 97 |

| Social support | 21.6 (17.6–25.7) | <0.001 | 97 |

| Cognition | 34.2 (30.8–37.5) | <0.001 | 96 |

| Communication | 29.9 (26.9–32.9) | <0.001 | 95 |

| Bodily discomfort | 41.5 (37.4–45.5) | <0.001 | 97 |

HRQOL=health-related quality of life; PDQ-39=Parkinson's Disease Questionnaire; SI=summary index.

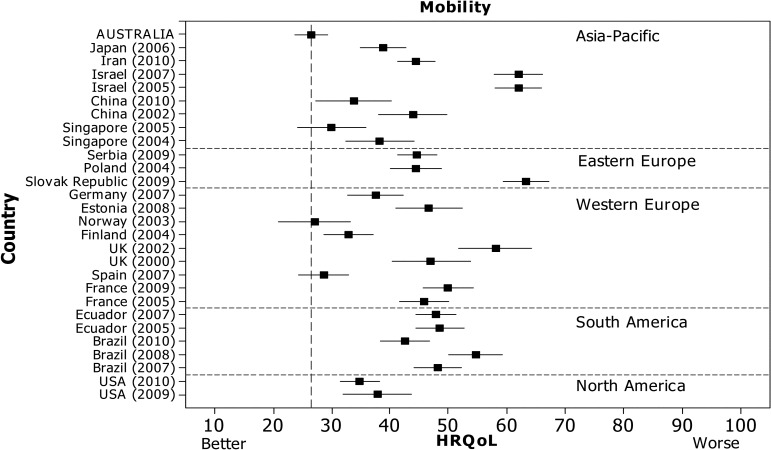

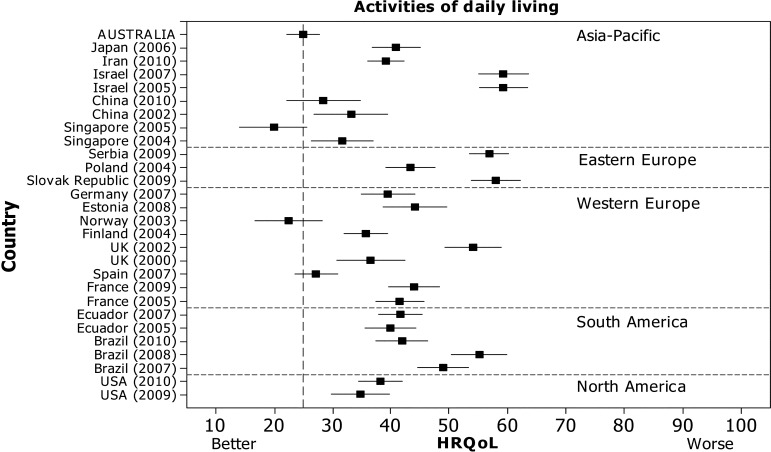

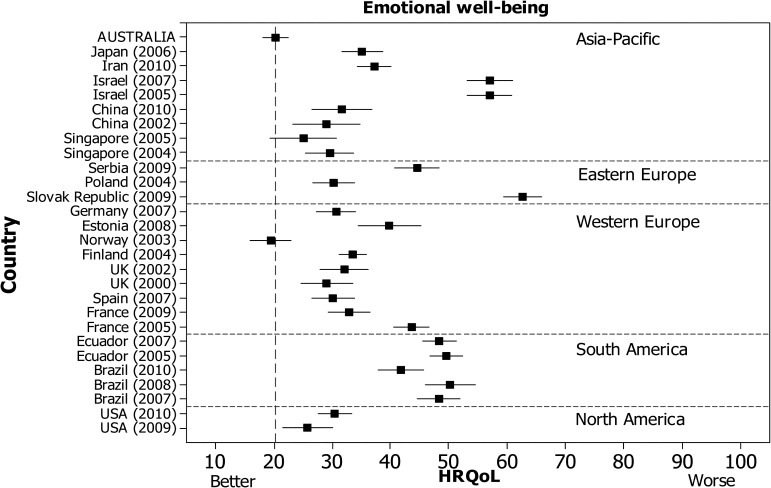

Secondary analyses were undertaken by subdividing the studies into five regions, to explore whether overall HRQOL within each region was more consistent. Figure 1 shows wide variability in overall HRQOL for PD samples in Western Europe, Eastern Europe, and Asia–Pacific; this is confirmed by the tests of heterogeneity presented in Table 4, which show high levels of inconsistency in the pooled estimate of the mean PDQ-39 SI score for these regions and dimensions (I2=95–99%). Only the North American sample of two studies passed the test of statistical heterogeneity for the regional samples, although it still demonstrated a moderate level of inconsistency (p=0.14, I2=54%). Similar variability was evident in ratings for the dimensions of mobility, activities of daily living, emotional well-being, stigma, cognition, and bodily discomfort across the studies at the regional level (see online Figure 1). The ratings for each dimension of HRQOL by people with PD living in Australia and other countries were also examined. The pooled estimated mean values for each dimension of HRQOL are shown in Table 4. The tests of heterogeneity for each dimension highlight the high levels of inconsistency across samples (I2 ranges from 95% for communication to 98% for emotional well-being).

DISCUSSION

Our study is the first to quantify the HRQOL of an Australian sample of people with PD. Mean scores on the PDQ-39 SI were lower (indicating better HRQOL) than those of individuals living in North American, South American, European, and Asian countries. Similar findings have been observed in previous cross-cultural studies examining the QOL of Australians in the general population.43–45 Midlife men and women living in Australia have been shown to have better QOL than individuals living in Taiwan.43 Adults in Hong Kong and Italy have also reported lower levels of life satisfaction and personal well-being than people living in Australia.44,45 Caution is required when interpreting these findings, given the methodological and statistical heterogeneity observed among studies from different countries. Differences in participant characteristics, such as disease severity, disease duration, and age, may contribute to the finding of better HRQOL in Australians with PD. Other unreported factors, such as the presence of social support networks, quality of the health care systems, and service delivery models, may also contribute to the observed differences.43 For example, most participants in the Australian PD sample received comprehensive care that included medical management, allied health reviews, and supportive services, which may not be available to people with PD in other countries.8 In addition, differences in culture, expectations, and values may explain why this Australian PD sample had better perceived HRQOL.

Participants in this Australian sample reported having fewer difficulties with the stigma and social support dimensions of the PDQ-39. Low ratings for stigma were also observed in some other countries, such as Singapore,21,37 Brazil,14,15,24,29 Norway,33 the United States,3,27 and the United Kingdom.13 In contrast, Zhao and colleagues,6 using the PDQ-8, found stigma to be a major concern among people with PD living in Singapore. The PDQ-8 is a short measure of health status that is derived from the PDQ-39.46 Further investigation is therefore warranted to determine the extent to which cultural differences impact the perception of stigma in individuals with PD.

The overall HRQOL of the Australian sample did not differ from that of individuals with PD living in Scandinavian countries such as Norway.33 This parallels findings by Kreuter and colleagues,47 who found that there was no difference in perceived HRQOL between individuals with spinal cord lesions living in Sweden and those living in Australia. Similarities in the health and social welfare systems between Australia and the Scandinavian countries may account for the lack of difference in QOL.43 Further cross-cultural comparisons are required to determine the extent of the differences in HRQOL between individuals with PD in Australia and those in Scandinavian countries. It may also be beneficial for studies to consider factors such as access to health care services and service delivery models when examining the HRQOL of people with PD in these countries.

The HRQOL of people with PD varied widely across the studies included in our meta-analysis, even when considered on a regional basis. Several factors may account for the observed differences in HRQOL throughout the world. First, few studies used population-based sampling techniques; their samples may therefore not be representative of the population of people with PD in those countries. Second, differences in participant characteristics such as disease severity, disease duration, and socio-economic status may have contributed to the variability in HRQOL, which may explain the heterogeneity in pooled estimates of the mean values across the dimensions of HRQOL as measured by the PDQ-39. To obtain a more precise estimate of the HRQOL of people with PD it would be useful for future studies to incorporate samples that better reflect the population of people with PD in those countries.

Other limitations also need to be considered when interpreting our findings. International samples were limited to studies that reported the overall PDQ-39 SI and dimension scores. Thus, our findings may not reflect all that is known about the HRQOL of people with PD living in countries outside Australia, which may have been reported differently or measured using other instruments. The sample characteristics reported in the literature were not always comparable across studies and there was also significant methodological and statistical heterogeneity. This may have limited our ability to determine whether differences in HRQOL indeed relate to differences in participant characteristics such as disease severity and disease duration. Further work using meta-regression analysis may be beneficial to extend the findings of this study and identify factors that potentially contribute to HRQOL for people with PD living in different countries.

The Australian PD sample included individuals who were able to travel to outpatient centres to participate in physiotherapy intervention programs. The generalizability of our findings to individuals with more severe disease who are non-ambulant and reside in nursing homes is therefore uncertain. Moreover, the sample may have been biased toward individuals actively seeking to participate in a physiotherapy exercise trial, who may have different perceptions of their HRQOL from the broader population of people with PD living in Australia.

Because the PDQ-39, a disease-specific instrument, was used to measure HRQOL in the current study, we cannot make comparisons with unimpaired individuals or those with other health conditions and can only examine the QOL dimensions directly related to health. The contributions of other factors such as social support and socio-economic status warrant further investigation, because quality of life is a multi-dimensional concept that encompasses a broad array of life situations.1

CONCLUSIONS

Although Australians with PD perceived themselves as having poor HRQOL, particularly in terms of physical function and mobility, their HRQOL was less severely compromised than that of samples from other countries. Further research is therefore needed to explain why Australians with PD report better HRQOL compared to individuals from other countries. Such research would include examining the contribution of factors such as medication levels, access to supportive services, and service delivery models, as well as the impact of factors such as age, disease duration, and disease severity on the HRQOL of Australians with PD.

KEY MESSAGES

What is already known on this topic

Parkinson disease has a negative impact on the HRQOL of some people with PD, particularly in the dimensions related to physical mobility, social function, and emotional health.

What this study adds

This study has shown that although many people with PD living in Australia rated their HRQOL as relatively poor, in the context of international samples the HRQOL of Australians was less severely compromised.

APPENDIX: MEAN AND 95% CONFIDENCE INTERVALS OF THE DIMENSIONS OF THE PDQ-39 FOR PEOPLE WITH PD LIVING IN AUSTRALIA AND OTHER COUNTRIES

Physiotherapy Canada 2012; 64(4);338–346; doi:10.3138/ptc.2011-26

REFERENCES

- 1.Wood-Dauphinee S. Assessing quality of life in clinical research: from where have we come and where are we going? J Clin Epidemiol. 1999;52(4):355–63. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(98)00179-6. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0895-4356(98)00179-6. Medline:10235176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Montel S, Bonnet AM, Bungener C. Quality of life in relation to mood, coping strategies, and dyskinesia in Parkinson's disease. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2009;22(2):95–102. doi: 10.1177/0891988708328219. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0891988708328219. Medline:19150974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown CA, Cheng EM, Hays RD, et al. SF-36 includes less Parkinson Disease (PD)-targeted content but is more responsive to change than two PD-targeted health-related quality of life measures. Qual Life Res. 2009;18(9):1219–37. doi: 10.1007/s11136-009-9530-y. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11136-009-9530-y. Medline:19714487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Suzukamo Y, Ohbu S, Kondo T, et al. Psychological adjustment has a greater effect on health-related quality of life than on severity of disease in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2006;21(6):761–6. doi: 10.1002/mds.20817. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/mds.20817. Medline:16511869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Soh S-E, McGinley J, Morris ME. Measuring quality of life in Parkinson's disease: selection of-an-appropriate health-related quality of life instrument. Physiotherapy. 2011;97(1):83–9. doi: 10.1016/j.physio.2010.05.006. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.physio.2010.05.006. Medline:21295243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhao YJ, Tan LCS, Lau PN, et al. Factors affecting health-related quality of life amongst Asian patients with Parkinson's disease. Eur J Neurol. 2008;15(7):737–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2008.02178.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-1331.2008.02178.x. Medline:18494793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peto V, Jenkinson C, Fitzpatrick R, et al. The development and validation of a short measure of functioning and well being for individuals with Parkinson's disease. Qual Life Res. 1995;4(3):241–8. doi: 10.1007/BF02260863. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF02260863. Medline:7613534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morris ME, Menz HB, McGinley JL, et al. Falls and mobility in Parkinson's disease: protocol for a randomised controlled clinical trial. BMC Neurol. 2011;11(1):93. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-11-93. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2377-11-93. Medline:21801451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189–98. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. Medline:1202204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoehn MM, Yahr MD. Parkinsonism: onset, progression and mortality. Neurology. 1967;17(5):427–42. doi: 10.1212/wnl.17.5.427. Medline:6067254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fahn S, Elton R. UPDRS development Committee. Unified Parkinson's disease rating scale. In: Fahn S, editor. Recent developments in Parkinson's disease. New York: MacMillan; 1987. pp. 153–63. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martínez-Martín P, Serrano-Dueñas M, Vaca-Baquero V. Psychometric characteristics of the Parkinson's disease questionnaire (PDQ-39)–Ecuadorian version. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2005;11(5):297–304. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2005.02.003. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.parkreldis.2005.02.003. Medline:15886043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schrag A, Jahanshahi M, Quinn N. How does Parkinson's disease affect quality of life? A comparison with quality of life in the general population. Mov Disord. 2000;15(6):1112–8. doi: 10.1002/1531-8257(200011)15:6<1112::aid-mds1008>3.0.co;2-a. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/1531-8257(200011)15:6<1112::AID-MDS1008>3.0.CO;2-A. Medline:11104193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carod-Artal FJ, Vargas AP, Martinez-Martin P. Determinants of quality of life in Brazilian patients with Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2007;22(10):1408–15. doi: 10.1002/mds.21408. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/mds.21408. Medline:17516479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carod-Artal FJ, Ziomkowski S, Mourão Mesquita H, et al. Anxiety and depression: main determinants of health-related quality of life in Brazilian patients with Parkinson's disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2008;14(2):102–8. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2007.06.011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.parkreldis.2007.06.011. Medline:17719828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gómez-Esteban JC, Zarranz JJ, Lezcano E, et al. Influence of motor symptoms upon the quality of life of patients with Parkinson's disease. Eur Neurol. 2007;57(3):161–5. doi: 10.1159/000098468. http://dx.doi.org/10.1159/000098468. Medline:17213723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zäch M, Friedman A, Sławek J, et al. Quality of life in Polish patients with long-lasting Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2004;19(6):667–72. doi: 10.1002/mds.10698. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/mds.10698. Medline:15197705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Soh S-E, Morris ME, McGinley JL. Determinants of health-related quality of life in Parkinson's disease: a systematic review. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2011;17(1):1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2010.08.012. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.parkreldis.2010.08.012. Medline:20833572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peto V, Jenkinson C, Fitzpatrick R. PDQ-39: a review of the development, validation and application of a Parkinson's disease quality of life questionnaire and its associated measures. J Neurol. 1998;245(S1) Suppl 1:S10–4. doi: 10.1007/pl00007730. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/PL00007730. Medline:9617716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jenkinson C, Fitzpatrick R, Peto V, et al. The Parkinson's Disease Questionnaire (PDQ-39): development and validation of a Parkinson's disease summary index score. Age Ageing. 1997;26(5):353–7. doi: 10.1093/ageing/26.5.353. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/ageing/26.5.353. Medline:9351479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tan LCS, Luo N, Nazri M, et al. Validity and reliability of the PDQ-39 and the PDQ-8 in English-speaking Parkinson's disease patients in Singapore. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2004;10(8):493–9. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2004.05.007. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.parkreldis.2004.05.007. Medline:15542010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tsang KL, Chi I, Ho SL, et al. Translation and validation of the standard Chinese version of PDQ-39: a quality-of-life measure for patients with Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2002;17(5):1036–40. doi: 10.1002/mds.10249. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/mds.10249. Medline:12360555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. Systematic reviews: CRD's guidance for undertaking reviews in health care. York: University of York; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carod-Artal FJ, Martinez-Martin P, Vargas AP. Independent validation of SCOPA-psychosocial and metric properties of the PDQ-39 Brazilian version. Mov Disord. 2007;22(1):91–8. doi: 10.1002/mds.21216. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/mds.21216. Medline:17094102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gray A, McNamara I, Aziz T, et al. Quality of life outcomes following surgical treatment of Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2002;17(1):68–75. doi: 10.1002/mds.1259. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/mds.1259. Medline:11835441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reuther M, Spottke EA, Klotsche J, et al. Assessing health-related quality of life in patients with Parkinson's disease in a prospective longitudinal study. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2007;13(2):108–14. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2006.07.009. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.parkreldis.2006.07.009. Medline:17055326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tickle-Degnen L, Ellis T, Saint-Hilaire MH, et al. Self-management rehabilitation and health-related quality of life in Parkinson's disease: a randomized controlled trial. Mov Disord. 2010;25(2):194–204. doi: 10.1002/mds.22940. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/mds.22940. Medline:20077478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jenkinson C, Heffernan C, Doll H, et al. The Parkinson's Disease Questionnaire (PDQ-39): evidence for a method of imputing missing data. Age Ageing. 2006;35(5):497–502. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afl055. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afl055. Medline:16772362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carod-Artal FJ, da Silveira Ribeiro L, Kummer W, et al. Psychometric properties of the SCOPA-AUT Brazilian Portuguese version. Mov Disord. 2010;25(2):205–12. doi: 10.1002/mds.22882. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/mds.22882. Medline:19938162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martinez-Martin P, Serrano-Dueñas M, Forjaz MJ, et al. Two questionnaires for Parkinson's disease: are the PDQ-39 and PDQL equivalent? Qual Life Res. 2007;16(7):1221–30. doi: 10.1007/s11136-007-9224-2. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11136-007-9224-2. Medline:17534735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chapuis S, Ouchchane L, Metz O, et al. Impact of the motor complications of Parkinson's disease on the quality of life. Mov Disord. 2005;20(2):224–30. doi: 10.1002/mds.20279. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/mds.20279. Medline:15384126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Haapaniemi TH, Sotaniemi KA, Sintonen H, et al. The generic 15D instrument is valid and feasible for measuring health related quality of life in Parkinson's disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004;75(7):976–83. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2003.015693. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.2003.015693. Medline:15201353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Herlofson K, Larsen JP. The influence of fatigue on health-related quality of life in patients with Parkinson's disease. Acta Neurol Scand. 2003;107(1):1–6. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0404.2003.02033.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0404.2003.02033.x. Medline:12542506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Krikmann U, Taba P, Lai T, et al. Validation of an Estonian version of the Parkinson's Disease Questionnaire (PDQ-39) Health Qual Life Out. 2008;6:23. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-6-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dubayova T, Nagyova I, Havlikova E, et al. Neuroticism and extraversion in association with quality of life in patients with Parkinson's disease. Qual Life Res. 2009;18(1):33–42. doi: 10.1007/s11136-008-9410-x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11136-008-9410-x. Medline:18989757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Žiropađa L, Stefanova E, Potrebić A, et al. Quality of life in Serbian patients with Parkinson's disease. Qual Life Res. 2009;18(7):833–9. doi: 10.1007/s11136-009-9500-4. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11136-009-9500-4. Medline:19562515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Luo N, Tan LCS, Li SC, et al. Validity and reliability of the Chinese (Singapore) version of the Parkinson's Disease Questionnaire (PDQ-39) Qual Life Res. 2005;14(1):273–9. doi: 10.1007/s11136-004-2654-1. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11136-004-2654-1. Medline:15789961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Luo W, Gui XH, Wang B, et al. Validity and reliability testing of the Chinese (mainland) version of the 39-item Parkinson's Disease Questionnaire (PDQ-39) J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2010;11(7):531–8. doi: 10.1631/jzus.B0900380. http://dx.doi.org/10.1631/jzus.B0900380. Medline:20593519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moore O, Kreitler S, Ehrenfeld M, et al. Quality of life and gender identity in Parkinson's disease. J Neural Transm. 2005;112(11):1511–22. doi: 10.1007/s00702-005-0285-5. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00702-005-0285-5. Medline:15785864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moore O, Peretz C, Giladi N. Freezing of gait affects quality of life of peoples with Parkinson's disease beyond its relationships with mobility and gait. Mov Disord. 2007;22(15):2192–5. doi: 10.1002/mds.21659. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/mds.21659. Medline:17712856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nojomi M, Mostafavian Z, Shahidi GA, et al. Quality of life in patients with Parkinson's disease: Translation and psychometric evaluation of the Iranian version of PDQ-39. J Res Med Sci. 2010;15(2):63–9. Medline:21526061. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gardner MJ, Altman DG. Confidence intervals rather than P values: estimation rather than hypothesis testing. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1986;292(6522):746–50. doi: 10.1136/bmj.292.6522.746. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.292.6522.746. Medline:3082422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fu SYK, Anderson D, Courtney M, et al. The relationship between country of residence, gender and the quality of life in Australian and Taiwanese midlife residents. Soc Indic Res. 2006;79(1):25–49. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11205-005-3002-8. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lau A, Cummins RA, McPherson W. An investigation into the cross-cultural equivalence of the Personal Wellbeing Index. Soc Indic Res. 2005;72(3):403–30. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11205-004-0561-z. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Verri A, Cummins RA, Petito F, et al. An Italian-Australian comparison of quality of life among people with intellectual disability living in the community. J Intellect Disabil Res. 1999;43(6):513–22. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2788.1999.00241.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2788.1999.00241.x. Medline:10622368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jenkinson C, Fitzpatrick R, Peto V, et al. The PDQ-8: Development and validation of a short-form Parkinson's Disease Questionnaire. Psychol Health. 1997;12(6):805–14. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08870449708406741. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kreuter M, Siösteen A, Erkholm B, et al. Health and quality of life of persons with spinal cord lesion in Australia and Sweden. Spinal Cord. 2005;43(2):123–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101692. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/sj.sc.3101692. Medline:15545980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]