Abstract

Pilomatricoma is typically an isolated benign tumor of the hair follicle matrix with very low incidence, recurrence, and initial diagnostic accuracy. This report presents a case of a pilomatricoma of the left chest that was initially ignored due to the limited extent of access to medical care in Palau, and subsequent treatment for cervical cancer. The paper helps to emphasize the importance of a vast differential diagnosis, especially in those patients from the Pacific Islands.

Keywords: Pilomatricoma, pilomatrixoma, calcifying epithelioma of Malherbe, CTNNB1

Introduction

Pilomatricomas are commonly misdiagnosed, benign neoplasms of the skin, thought to arise from hair follicles. They most frequently appear as solitary, firm nodules, exhibiting a normal to pearl white epidermis. Calcium deposits are present in well over half the lesions identified. Thus, the skin lesion is also described as a calcifying epithelioma. Some debate exists regarding accurate preoperative diagnosis of pilomatricomas. Histologically, pilomatricomas present as a well demarcated lesion, stemming from dermis and extending into the subcutaneous fat. They classically consist of islands of epithelial cells comprised of both basophilic cells with meager cytoplasm and ghost cells that have a central unstained area indicative of a lost nucleus.

Pilomatricomas are generally asymptomatic and found in the head and neck area and, upper extremities, but rarely identified on the chest, trunk, or lower extremities. They are reported to occur in people of all ages; however the distribution favors both children and the elderly.

This article describes a case of a Pacific Islander with a pilomatricoma arising from her left superior chest, and the clinical, radiographic, and pathologic features of this rare tumor.

Case Report

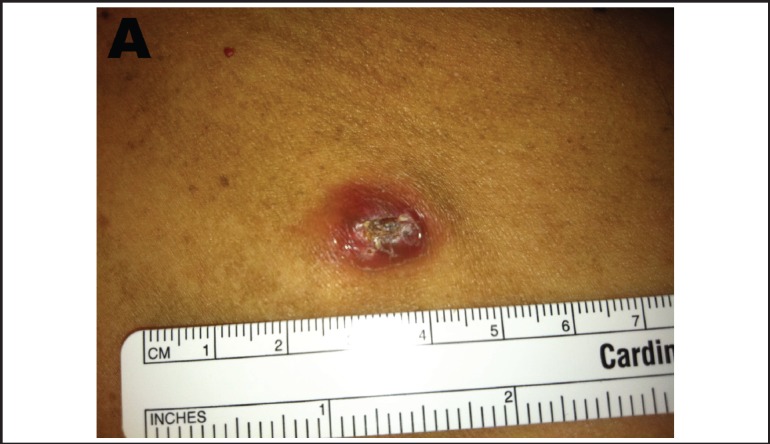

A 43-year-old woman from the island of Palau with a history of cervical cancer presented to the General Surgery clinic in June 2011, with a fungating left breast mass of recent onset and rapid expansion (Figure 1). At the time, the patient was diagnosed with Stage IIIB cervical cancer and underwent chemotherapy. She stated that the lesion was first detected while completing a PET-CT, two months prior to presentation, for her cervical cancer management. The recent PET-CT examination identified a hyper metabolic mass in the anterior left chest wall. The patient was recommended to have the lesion evaluated with mammography. Bilateral mammography demonstrated scattered fibroglandular elements, however no dominant mass, architectural distortion, or suspicious calcification was detected in either breast. The mass identified on PET-CT was found to be outside of the breast, and a focal spot compression view of the anterior chest wall failed to completely include the lesion.

Figure 1 A and B. Erythematous lesion with an elevated border and central ulceration on left breast.

Figure 1A.

Figure 1B.

The patient then underwent ultrasound of the left chest. The patient readily identified a fungating mass in the medial subclavicular region of the left chest wall. She stated that this lesion had been rapidly expanding over the previous three to four months. Sonographic interrogation of the mass was limited due to the dense calcification, which caused large shadowing artifact. The lesion measured approximately 2–3 cm in diameter, and 1.5 cm in depth (Figure 2). The lesion was documented to have no evidence of malignancy and to not be related to the breast parenchyma. The patient was recommended for excisional biopsy.

Figure 2.

Ultrasound of fungating dermal mass in the medial supraclavicular region of the left chest wall. Dense calcifications causing shadowing artifact. Dermis appears to be thickened and the pectoralis fascia appears to be displaced posteriorly. The lesion appears to be approximately 2– 3 cm in diameter. The depth, difficult to judge due to the posterior shadowing, is approximately 1.5cm.

The patient underwent punch biopsy in the General Surgery clinic. At that time, the left breast mass remained painless and not associated with any symptoms such as bone pain or nipple discharge, or with other palpable breast masses. No other areas of erythema or overlying skin changes appreciated.

The patient returned for follow up of biopsy results. Tissue exam revealed a pilomatricoma. The patient stated that the mass was unchanged since last visit. Excision of the lesion was discussed with the patient and she was amenable to this option. Given the benign nature of pilomatricoma, surgery was deferred until after placement of her brachytherapy catheters for her cervical malignancy.

After completion of her chemotherapy, patient underwent surgical excision of the lesion. Macroscopically, the mass was measured to be approximately 3.6 × 2.8 × 2.4 cm. No invasion into adjacent structures was noted. The sample was sent for pathological examination. The specimen contained a centrally located, indurated, bosselated, variably pigmented area measuring 1.0 × 0.8 × 0.3 cm. Microscopic examination revealed a localized area of friable calcified material measuring up to 1.7 cm in diameter (Figure 3). The specimen was diagnosed as a completely excised pilomatricoma, with clear margins.

Figure 3 A and B. Left breast pilomatricoma. Well-circumscribed with islands of basaloid cells (arrows). Most of the tumor is composed of eosinophilic keratin debris (asterisk) and a mixed inflammatory infiltrate (triangle).

Figure 3A.

Figure 3B.

Discussion

The Republic of Palau is a constitutional democracy with a population of approximately 21,000 people. Upon independence in 1994, Palau entered into a 50-year Compact of Free Association with the United States. Palau is an archipelago consisting of several hundred volcanic and limestone islands and coral atolls, few of which are inhabited. Health facilities in Palau are adequate for routine medical care, but the availability and quality of services are limited. Serious medical conditions requiring hospitalizations or evacuation to the United States or elsewhere may cost tens of thousands of dollars.1

Patients that live in the Pacific Islands often present with diseases and pathology that are in an advanced stage or are unfamiliar to practicing Western-trained physicians. The vast differential diagnosis of cutaneous lesions is an important consideration for physicians trained in the United States who are practicing in other regions of the world.

Pilomatricomas were first described by Malherbe and Chenantais in 1880 as a benign neoplasm of sebaceous gland origin.2 It was not until later that the lesion was understood to be a calcifying epithelioma that arises from hair follicle matrix, hair cortex, follicular infundibulum, outer root sheath, and hair bulge.3 Pilomatricoma is a term first used by Jones and Campbell in 1969, when they discovered presentations of subcutaneous lesions in a pediatric population, with similar unique histological features occurring in adults. Pilomatricomas manifest as a benign, cutaneous, firm, solitary lesions of the face, neck, and upper extremities. The difficulty with diagnosing pilomatricoma lies with their variant morphology and sometimes unusual appearance similar to more common lesions. The presentation of these subcutaneous nodules may resemble benign lesions such as a keratoacanthoma, ossifying hematoma, and fibroxanthoma, or malignant lesions such as squamous cell carcinoma. Diagnostic identification of this lesion is important because, although extremely rare with fewer than 20 cases described in the literature, pilomatricomas can undergo malignant transformation into a pilomatrix carcinoma.4–6 Most pilomatrix carcinomas occur on the head and neck of middle age to elderly patients. The rate of malignant transformation is difficult to assess due to overall disease rarity and lack of specific features that can distinguish whether a malignant pilomatricoma has arisen de novo or if it represents the malignant transformation from a preexisting pilomatricoma.7

Imaging characteristics described in this paper are not diagnostic nor are they required for diagnosis of pilomatricoma except when the diagnosis is unclear as in our report. Ultrasound has demonstrated the highest accuracy rates between 28.9 and 46 percent. There is also literature citing some diagnostic discriminative findings on ultrasound that may distinguish pilomatricomas from other subcutaneous tumors: heterogeneous echotexture, internal echogenic foci in scattered-dot pattern, and a hypoechoic rim or posterior shadowing.8 Ultrasound imaging of pilomatricomas usually demonstrates lesions with an ovoid complex mass at the junction of the dermis and subcutaneous fat with focal thinning of the overlying dermis.9

Computed tomography (CT) can also be used to study pilomatricomas. They appear as sharply demarcated subcutaneous tumors containing micro-calcifications. The predicament, however, is the same as the clinical diagnosis. There are many lesions that share these CT characteristics, including sebaceous cysts, foreign body reaction, and metastatic bone formations.10 There have also been reports of the use of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Most demonstrate uniform, homogeneous signal on T1 weighted signal, with varying results on T1 with contrast and T2 imaging.11–12 Therefore, the nonspecific features of pilomatricoma on MRI, do not allow for its use as a definitive diagnostic tool.

The only truly reliable means of diagnosis remains pathological evaluation. The classic histology is said to be defined by the presence of ghost or shadow cells and basophilic cells. At low power the histological pattern usually seen in pilomatricoma is of a well-circumscribed nodulo-cystic tumor. While predominantly seen within the lower dermis, extension into the subcutaneous tissue is not uncommon. Figure 3A demonstrates the islands of eosinophilic cells derived from basaloid proliferation. As the tumor matures, these basaloid cells degrade centrally forming the anucleated ghost, or shadow cells, due to the unstained region.6,13 The shadow cell area represents differentiation towards the hair cortex. Occasionally, there are areas of calcification within the shadow cell regions and infiltration with multinucleated cells formed at sites of rupture. Shadow cells alone, however, cannot make the diagnosis. Many other lesions that cause inflammatory reactions such as foreign body granulomas or keratin debris, may also have this characteristic finding.

Pilomatricomas are traditionally regarded as benign tumors with limited understanding of any possible transition to pilomatrical carcinoma. The clinical difficulty distinguishing pilomatricomas from more common skin lesions, combined with a patient population that does not have ideal medical access, enforces the importance of incorporating these lesions in the differential diagnosis. Treatment is surgical resection with wide margins of 1–2cm. Following excision, pilomatricoma recurrences are relatively rare, with an overall rate of 2.6%.5,14–15 The rarity of this lesion provides little evidence for follow-up recommendations after excision. One study's treatment population remained free of recurrence during follow up that ranged from 3 to 37 months.15 If the lesion were to recur, the physician should have increased suspicion of pilomatrical carcinoma, however aggressive surgical excision remains the treatment of choice.16–19 Surgical excision of this tumor is a sufficient and curative treatment, with excellent postoperative prognosis for both cosmesis and to prevent the possibility of malignant transformation.

Abbreviations

- TAMC

Tripler Army Medical Center

- PET-CT

positron emission tomography-computed tomography

Disclosure/Disclaimer

The views expressed herein are of the authors and do not reflect the official policy of the Department of the Army, Department of Defense, or the US Government. The authors report no conflict of interest, financial, personal, or professional, concerning the preparation of this manuscript.

References

- 1.US Department of State, author. International travel. Palau Country Specific Information. 2012. Feb 22, [Feb 22 2012]. Available at http://www.travel.state.gov/travel/cis_pa_tw/cis/cis_993.html.

- 2.Malherbe A, Chenantais J. Note sur l'epithelioma calcifie des glandes sebaces. Progres Medical. 1880;8:826–828. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kurokawa I, Yamanaka K-i, Senba Y, Sugisaki H, Tsubura A, Kimura T, et al. Pilomatricoma can differentiate not only towards hair matrix and hair cortex, but also follicular infundibulum, outer root sheath and hair bulge. Experimental dermatology. Exp Dermatol. 2009;18(8):734–737. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2008.00835.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dubreuilh W, Cazenave E. De l'epithélioma calcifié: étude histologique. Ann Dermatol Syphilol. 1922;3:257–268. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Forbis R, Helwig EB. Pilomatrixoma (calcifying epithelioma) Arch Dermatol. 1961;83:606–617. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1961.01580100070009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Julian CG, Bowers PW. A clinical review of 209 pilomatricomas. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39(2 Part 1):191–195. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(98)70073-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schwartz RA. Skin Cancer:Recognition and Management. 2nd ed. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choo HJ, Lee SW, Lee YH, Lee JH, Oh M, Kim MH, et al. Pilomatricomas: the diagnostic value of ultrasound. Skeletal Radiology. 2009 doi: 10.1007/s00256-009-0678-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hughes J, Lam A, Rogers M. Use of ultrasonography in the diagnosis of childhood pilomatrixoma. Pediatr Dermatol. 1999;16:341–344. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1470.1999.00090.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Som PM, Shugar JM, Silvers AR. CT of pilomatrixoma in the cheek. Am J Neuroradiol. 1998;19:1219–1220. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Beuckeleer LH, De Schepper AM, Neetens I. Magnetic resonance imaging of pilomatricoma. Eur Radiol. 1996;6:72–75. doi: 10.1007/BF00619959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoffmann V, Roeren T, Möller P, Heuschen G. MR imaging of a pilomatrixoma. Pediatr Radiol. 1998;28:272. doi: 10.1007/s002470050350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang J, Cobb CJ, Martin SE, Venegas R, Wu N, Greaves TS. Pilomatrixoma: clinicopathologic study of 51 cases with emphasis on cytologic features. Diagn Cytopathol. 2002;27:167–172. doi: 10.1002/dc.10161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moehlenbeck FW. Pilomatrixoma (calcifying epithelioma): A statistical study. Arch Dermatol. 1973;108:532–534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thomas RW, Perkins JA, Ruegemer JL, Munaretto JA. Surgical excision of pilomatrimoxoma of the head and neck: A retrospective review of 26 cases. Ear Nose Thorat J. 1999;514:544–546. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Solanki P, Ramzy I, Durr N, Henkes D. Pilomatrixoma: Cytologic features with differential diagnostic considerations. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1987;I 11:294–297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lopansri S, Mihm MC., Jr Pilomatrix carcinoma or calcifying epitheliocarcinoma of Malherbe: A case report and review of literature. Cancer. 1980;45:2368–2373. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19800501)45:9<2368::aid-cncr2820450922>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sasaki CT, Yue A, Enriques R. Giant calcifying epithelioma. Arch Otolaryngol. 1976;102:753–755. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1976.00780170071012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lan MY, Lan MC, Ho CY, Li WY, Lin CZ. Pilomatricoma of the head and neck: a retrospective review of 179 cases. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;129(12):1327–1330. doi: 10.1001/archotol.129.12.1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]