Abstract

Background

Monopartite begomoviruses (genus Begomovirus, family Geminiviridae) that infect sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas) around the world are known as sweepoviruses. Because sweet potato plants are vegetatively propagated, the accumulation of viruses can become a major constraint for root production. Mixed infections of sweepovirus species and strains can lead to recombination, which may contribute to the generation of new recombinant sweepoviruses.

Results

This study reports the full genome sequence of 34 sweepoviruses sampled from a sweet potato germplasm bank and commercial fields in Brazil. These sequences were compared with others from public nucleotide sequence databases to provide a comprehensive overview of the genetic diversity and patterns of genetic exchange in sweepoviruses isolated from Brazil, as well as to review the classification and nomenclature of sweepoviruses in accordance with the current guidelines proposed by the Geminiviridae Study Group of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV). Co-infections and extensive recombination events were identified in Brazilian sweepoviruses. Analysis of the recombination breakpoints detected within the sweepovirus dataset revealed that most recombination events occurred in the intergenic region (IR) and in the middle of the C1 open reading frame (ORF).

Conclusions

The genetic diversity of sweepoviruses was considerably greater than previously described in Brazil. Moreover, recombination analysis revealed that a genomic exchange is responsible for the emergence of sweepovirus species and strains and provided valuable new information for understanding the diversity and evolution of sweepoviruses.

Keywords: Geminivirus, Begomovirus, Sweet potato, Ipomoea batatas, Convolvulaceae

Background

Sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas, family Convolvulaceae) is one of the most important subsistence crops in developing countries and the third most important root crop after potato (Solanum tuberosum) and cassava (Manihot esculenta) [1]. More than 30 viruses are known to infect sweet potato and in some cases cause serious diseases in this crop [2]. Many of these viruses are monopartite begomoviruses (genus Begomovirus, family Geminiviridae).

The first two sweet potato begomoviruses to be characterized at the molecular level were Sweet potato leaf curl virus (SPLCV) and Sweet potato leaf curl Georgia virus (SPLCGoV), isolated in Louisiana, USA, in 1999 [3,4]. Subsequently, begomovirus infections in sweet potato have been reported from many countries, including Peru [5], Spain [6], China [7,8], Italy [9], Uganda [10], the United States [11] and Brazil [12,13], resulting in the description of ten additional novel species [6,7,10-13]. Phylogenetically, these viruses, for which the name sweepoviruses has been proposed [14], group in a monophyletic cluster that is distinct from the two main begomovirus branches, the Old and New World groups [6,15]. In addition to sweet potato, sweepoviruses can infect other hosts such as I. nil or I. setosa[16]. The symptoms caused by sweepoviruses depend on the specific host and usually consist of leaf curling and vein yellowing, although the infection can be asymptomatic.

Begomoviruses are transmitted to dicotyledonous plants by the whitefly Bemisia tabaci and cause important yield losses in many crops worldwide [17-19]. They have small, circular, single-strand DNA genomes consisting of one (monopartite) or two (bipartite) components encapsidated in twinned icosahedral particles [20,21]. The viral DNA-A has one (V1) or two open reading frames (ORFs - V1 and V2, in Old World begomoviruses) in the virion sense and four ORFs (C1, C2, C3 and C4) in the complementary sense, separated by an intergenic region (IR). The DNA-A encodes the viral coat protein (CP or V1) essential for viral transmission by B. tabaci and a V2 protein that may potentially be involved in virus accumulation, symptom development and virus movement [22,23]. The complementary-sense strand of DNA-A encodes the replication-associated protein (Rep or C1), the transcriptional activator protein (TrAP or C2), which controls viral gene expression, the replication-enhancer protein (REN or C3), required for viral DNA replication, and C4, a suppressor of post-transcriptional gene silencing (PTGS). The DNA-B of bipartite begomoviruses encodes two proteins, the nuclear shuttle protein (NSP – BV1) and the movement protein (MP – BC1) involved in intra- and inter-cellular movement within the plant [24].

Because sweet potato plants are vegetatively propagated, accumulation of viruses may occur and results in the co-infection of multiple viral genomes in a single plant. Mixed infections of sweepovirus species and strains have been previously shown to be frequent in sweet potato [6,11,13]. This phenomenon is extremely important for virus evolution because it provides opportunities for the occurrence of natural recombination events leading to extensive viral diversity [25-27]. The importance of recombination to geminivirus evolution is well known [26,28,29], and it is probably the mechanism responsible for the genetic diversification and emergence of the most agriculturally important begomovirus species [30-32]. While generating descendants with increased fitness, recombination has also been the cause of the increased genetic diversity within the begomoviruses that consequently complicates the classification of new species.

In this report, we present a study of the genetic diversity among sweepoviruses in Brazil. Thirty-four new complete sequences were determined. Based on these new sequences and on other sequences available in public sequence databases, the classification and nomenclature of sweepoviruses were revised in accordance with the current guidelines of the Geminiviridae Study Group of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV). We also provide clear evidence of recombination events that may have led to the emergence of new sweepovirus strains and species.

Results

Sequence analysis of full-length sweepovirus genomes

The complete nucleotide sequence of 34 cloned isolates (GenBank accessions HQ393442 to HQ393472 and HQ393474 to HQ393476) corresponding to putative full-length sweepovirus genomes was determined from the sweet potato Embrapa germplasm bank (SPEGB) and from commercial field samples. All genomes (ranging from 2779 to 2843 nucleotides) had the typical organization of monopartite begomoviruses with two ORFs in the virion sense (V1 and V2) and four ORFs in the complementary sense (C1, C2, C3 and C4). All sequences contained the conserved nonanucleotide sequence 5’-TAATATT↓AC-3’ and four iterative elements (iterons, short repeated sequences important for the replication process; Additional File 1), three direct (I, II and III) and one inverted (IV), with the core consensus sequence GGWGR located around the TATA box [33]. The iteron-related domain (IRD) in the N-terminal region of the replication-associated protein (Rep IRD) was also identified [34]. Sequences were identified that contain three Rep IRDs (MATPKRFRIS, MAPPNRFKIQ and MPRAGRFNLN) that differ from those previously described by Lozano et al.[6] and Zhang and Ling [11] for sweepoviruses (Additional File 1).

The 34 sequences determined here were compared with the sequences of 67 sweepovirus isolates obtained from sequence databases (Table 1 and Additional File 2). Each isolate was named following the standard nomenclature for begomoviruses (Table 2; see Additional File 2 for complete isolate names). Based on the current guidelines proposed by the ICTV Geminiviridae Study Group [35,36], two isolates belong to the same species if the overall nucleotide identity is >89%. The isolates described in this study belong to three species, Sweet potato leaf curl virus (SPLCV), Sweet potato golden vein virus (SPGVV) (the term "associated" was eliminated from the previous name, sweet potato golden vein-associated virus, following the standard begomovirus naming recommendation) and Sweet potato leaf curl Spain virus (SPLCESV), with the percentage of nucleotide identity ranging from 92.2-98.4% within each species. Twenty-one of the isolates belong to three novel strains (the demarcation threshold for distinguishing different strains of a species is 89-94% nucleotide identity [36]) of SPLCV and SPGVV named SPLCV-Brazil (SPLCV-BR), SPLCV-Pernambuco (SPLCV-PE) and SPGVV-Rondonia (SPGVV-RO). The other isolates are variants of SPLCV-United States (SPLCV-US), SPGVV-Paraiba (SPGVV-PB) and SPLCESV. The isolates of SPGVV and SPLCESV were found only in the SPEGB, whereas SPLCV isolates were found in both the SPEGB and commercial field samples. The samples from São Paulo state were infected by both SPLCV-US and SPLCV-Sao Paulo (SPLCV-SP) isolates. However, the samples from the States of Pernambuco, Paraíba and Rio Grande do Sul were shown to be infected by SPLCV-PE (Table 2). Interestingly, we identified co-infection in six samples (#171, #184, #325, #337, #346 and #370) from the SPEGB, whereas all of the samples from commercial fields were apparently infected by a single species/strain, as suggested by the uniformity of the clones obtained from these samples (Table 2).

Table 1.

Sweepoviruses used in this study

| Species-Strain | Accession no | Identification according to databases | Origin | Reference | Acronym suggested in this studyb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |

HQ393450 |

SPLCV-US[BR:PA:08]a |

Brazil |

This study |

SPLCV-US[BR:PA:08] |

| SPLCV-US |

HQ393451 |

SPLCV-US[BR:SE:PV:08] |

Brazil |

This study |

SPLCV-US[BR:SE:PV:08] |

|

HQ393443 |

SPLCV-US[BR:BA:CA1:08] |

Brazil |

This study |

SPLCV-US[BR:BA:CA1:08] |

|

|

HQ393446 |

SPLCV-US[BR:BA:CA2:08] |

Brazil |

This study |

SPLCV-US[BR:BA:CA2:08] |

|

|

FJ969834 |

SPLCV-RS2[BR:Est1] |

Brazil |

Paprotka et al., 2010 |

SPLCV-US[BR:RS:Est1:07] |

|

|

FJ969837 |

SPLCV-RS2[BR:Ros1] |

Brazil |

Paprotka et al., 2010 |

SPLCV-US[BR:RS:Ros1:07] |

|

|

FJ969835 |

SPLCV-RS2[BR:Mac1] |

Brazil |

Paprotka et al., 2010 |

SPLCV-US[BR:RS:Mac1:07] |

|

|

HQ393471 |

SPLCV-US[BR:SP:AM1:09] |

Brazil |

This study |

SPLCV-US[BR:SP:AM1:09] |

|

|

HQ393472 |

SPLCV-US[BR:SP:AM2:09] |

Brazil |

This study |

SPLCV-US[BR:SP:AM2:09] |

|

|

FJ969836 |

SPLCV-RS2[BR:Poa1] |

Brazil |

Paprotka et al., 2010 |

SPLCV-US[BR:RS:Poa1:07] |

|

|

HQ393475 |

SPLCV-US[BR:SP:AM4:09] |

Brazil |

This study |

SPLCV-US[BR:SP:AM4:09] |

|

|

HQ393474 |

SPLCV-US[BR:SP:AM3:09] |

Brazil |

This study |

SPLCV-US[BR:SP:AM3:09] |

|

|

HM754641 |

SPLCV-[Haenam1] |

South Korea |

GenBank |

SPLCV-US[KR:Hae1:09] |

|

|

HM754637 |

SPLCV-[Yeojoo 507] |

South Korea |

GenBank |

SPLCV-US[KR:Yeo507:09] |

|

|

FJ560719 |

SPLCKrV-[J-508] |

South Korea |

GenBank |

SPLCV-US[KR:Yeo508:08] |

|

|

HM754639 |

SPLCV-[Haenam532] |

South Korea |

GenBank |

SPLCV-US[KR:Hae532:09] |

|

|

HM754638 |

SPLCV-[Haenam 519–3] |

South Korea |

GenBank |

SPLCV-US[KR:Hae519:09] |

|

|

HM754635 |

SPLCV-[Yeojoo 388] |

South Korea |

GenBank |

SPLCV-US[KR:Yeo388:09] |

|

|

HM754636 |

SPLCV-[Nonsan 445–2] |

South Korea |

GenBank |

SPLCV-US[KR:Non445-2:09] |

|

|

HM754634 |

SPLCV-[Chungju 263] |

South Korea |

GenBank |

SPLCV-US[KR:Chu263:09] |

|

|

HM754640 |

SPLCV-[Haenam 618–2] |

South Korea |

GenBank |

SPLCV-US[KR:Hae618:09] |

|

|

AF104036 |

SPLCV-US[US:Lou:94] |

USA |

Lotrakul & Valverde, 1999 |

SPLCV-US[US:Lou:94] |

|

|

HQ393453 |

SPLCV-US[BR:RO:OPO:08] |

Brazil |

This study |

SPLCV-US[BR:RO:OPO:08] |

|

|

FJ176701 |

SPLCV-[Eastern China] |

China |

GenBank |

SPLCV-US[CN:Jia:08] |

|

|

AB433788 |

SPLCV-[Japan:Kyoto:1998] |

Japan |

GenBank |

SPLCV-US[JR:Kyo:98] |

|

|

HQ333141 |

SPLCV-[US:MS:WS1-4] |

USA |

Zhang & Ling, 2011 |

SPLCV-US[US:MS:WS1-4:07] |

|

|

HQ333142 |

SPLCV-[US:MS:WS3-8] |

USA |

Zhang & Ling, 2011 |

SPLCV-US[US:MS:WS3-8:07] |

|

|

HQ333140 |

SPLCV-[US:MS:4B-14] |

USA |

Zhang & Ling, 2011 |

SPLCV-US[US:MS:4b-14:07] |

|

|

HQ333139 |

SPLCV-[US:MS:1B-1A] |

USA |

Zhang & Ling, 2011 |

SPLCV-US[US:MS:1b-1a:07] |

|

| SPLCV-CN |

EU267799 |

SPLCV-[RL7] |

China |

GenBank |

SPLCV-CN[CN:Yn:RL7:07] |

|

FN806776 |

SPLCV-[Y338] |

China |

GenBank |

SPLCV-CN[CN:Yn338:09] |

|

|

EU253456 |

SPLCV-[RL31] |

China |

GenBank |

SPLCV-CN[CN:Yn:RL31:07] |

|

| SPLCV-SP |

HQ393473 |

SPLCV-SP[BR:AlvM:09] |

Brazil |

Albuquerque et al., 2011 |

SPLCV-SP[BR:SP:AlvM:09] |

|

HQ393476 |

SPLCV-SP[BR:SP:PP:09] |

Brazil |

This study |

SPLCV-SP[BR:SP:PP:09] |

|

| SPLCV-JP |

AB433787 |

SPLCV-[Japan:Kumamoto:1998] |

Japan |

GenBank |

SPLCV-JP[JR:Kum:98] |

|

AB433786 |

SPLCV-[Japan:Miyazaki:1996] |

Japan |

GenBank |

SPLCV-JP[JR:Miy:96] |

|

| SPLCV-SC |

HQ333138 |

SPLCV-[US:SC:646B-11] |

USA |

Zhang & Ling, 2011 |

SPLCV-SC[US:SC:646-B11:06] |

|

HQ333137 |

SPLCV-[US:SC:634–7] |

USA |

Zhang & Ling, 2011 |

SPLCV-SC[US:SC:634–7:06] |

|

|

HQ333135 |

SPLCV-[US:SC:377–23] |

USA |

Zhang & Ling, 2011 |

SPLCV-SC[US:SC:377–23:06] |

|

|

HQ333136 |

SPLCV-[US:SC:634–2] |

USA |

Zhang & Ling, 2011 |

SPLCV-SC[US:SC:634–2:06] |

|

| SPLCV-BR |

HQ393445 |

SPLCV-BR[BR:BA:CA:08] |

Brazil |

This study |

SPLCV-BR[BR:BA:CA:08] |

|

HQ393460 |

SPLCV-BR[BR:RO:Cac:08] |

Brazil |

This study |

SPLCV-BR[BR:RO:Cac:08] |

|

|

HQ393455 |

SPLCV-BR[BR:RO:OPO:08] |

Brazil |

This study |

SPLCV-BR[BR:RO:OPO:08] |

|

|

HQ393449 |

SPLCV-BR[BR:SE:Ria:08] |

Brazil |

This study |

SPLCV-BR[BR:SE:Ria:08] |

|

|

HQ393442 |

SPLCV-BR[BR:BA:Uru:08] |

Brazil |

This study |

SPLCV-BR[BR:BA:Uru:08] |

|

| SPLCV-PR |

DQ644563 |

SPLCV-[N4] |

Puerto Rico |

GenBank |

SPLCV-PR[PR:Me-N4:06] |

|

DQ644562 |

SPLCV-[PR80-N2] |

Puerto Rico |

GenBank |

SPLCV-PR[PR:80-N2:06] |

|

| SPLCV-PE |

HQ393456 |

SPLCV-PE[BR:RO:PV:08] |

Brazil |

This study |

SPLCV-PE[BR:RO:PV:08] |

|

HQ393464 |

SPLCV-PE[BR:RS:MP1:09] |

Brazil |

This study |

SPLCV-PE[BR:RS:MP1:09] |

|

|

HQ393465 |

SPLCV-PE[BR:RS:MP2:09] |

Brazil |

This study |

SPLCV-PE[BR:RS:MP2:09] |

|

|

HQ393467 |

SPLCV-PE[BR:RS:MP5:09] |

Brazil |

This study |

SPLCV-PE[BR:RS:MP5:09] |

|

|

HQ393462 |

SPLCV-PE[BR:PE:CSF:08] |

Brazil |

This study |

SPLCV-PE[BR:PE:CSF:08] |

|

|

HQ393463 |

SPLCV-PE[BR:PE:CSF:08] |

Brazil |

This study |

SPLCV-PE[BR:PE:CSF:08] |

|

|

HQ393461 |

SPLCV-PE[BR:PB:PF:09] |

Brazil |

This study |

SPLCV-PE[BR:PB:PF:09] |

|

|

HQ393466 |

SPLCV-PE[BR:RS:MP4:09] |

Brazil |

This study |

SPLCV-PE[BR:RS:MP4:09] |

|

|

HQ393469 |

SPLCV-PE[BR:RS:MP7:09] |

Brazil |

This study |

SPLCV-PE[BR:RS:MP7:09] |

|

|

HQ393468 |

SPLCV-PE[BR:RS:MP6:09] |

Brazil |

This study |

SPLCV-PE[BR:RS:MP6:09] |

|

|

HQ393470 |

SPLCV-PE[BR:RS:MP3:09] |

Brazil |

This study |

SPLCV-PE[BR:RS:MP3:09] |

|

| SPLCV-Fu |

FJ515898 |

SPLCV-[Fp-3] |

China |

Yang et al., 2009 |

SPLCV-Fu[CN:Fj:Fp3:07] |

|

FJ515897 |

SPLCV-[Fp-2] |

China |

Yang et al., 2009 |

SPLCV-Fu[CN:Fj:Fp2:07] |

|

|

FJ515896 |

SPLCV-[Fp-1] |

China |

Yang et al., 2009 |

SPLCV-Fu[CN:Fj:Fp1:07] |

|

| SPLCV-ES |

EU856364 |

SPLCV-ES[ES:CI:BG12:02] |

Spain |

Lozano et al., 2009 |

SPLCV-ES[ES:CI:BG12:02] |

|

EF456744 |

SPLCV-ES[ES:CI:BG6:02] |

Spain |

Lozano et al., 2009 |

SPLCV-ES[ES:CI:BG6:02] |

|

|

EU856366 |

SPLCV-ES[ES:CI:BG13:02] |

Spain |

Lozano et al., 2009 |

SPLCV-ES[ES:CI:BG13:02] |

|

| SPLCV-IT |

AJ586885 |

SPLCV-IT[IT:Sic:02] |

Italy |

Briddon et al., 2005 |

SPLCV-IT[IT:Sic:02] |

| SPLCLaV-BR |

FJ969833 |

SPLCV-RS1[BR:Tav1] |

Brazil |

Paprotka et al., 2010 |

SPLCLaV-BR[BR:RS:Tav1:07] |

| SPLCLaV-ES |

EF456746 |

SPLCLaV-[ES:CI:BG27:02] |

Spain |

Lozano et al., 2009 |

SPLCLaV-ES[ES:CI:BG27:02] |

|

EU839579 |

SPLCLaV-[ES:Mal:BG30:06] |

Spain |

Lozano et al., 2009 |

SPLCLaV-ES[ES:Mal:BG30:06] |

|

| SPLCBeV |

FN432356 |

SPLCBV-[India:West Bengal:2008] |

India |

GenBank |

SPLCBeV-[IN:Ben:08] |

| SPLCBRV |

FJ969832 |

SPLCV-CE[BR:For1] |

Brazil |

Paprotka et al., 2010 |

SPLCBRV-[BR:CE:For1:07] |

| SPLCCaV |

EF456742 |

SPLCCaV-[ES:CI:BG4:02] |

Spain |

Lozano et al., 2009 |

SPLCCaV-[ES:CI:BG4:02] |

|

EF456745 |

SPLCCaV-[ES:CI:BG7:02] |

Spain |

Lozano et al., 2009 |

SPLCCaV-[ES:CI:BG7:02] |

|

|

EU856365 |

SPLCCaV-[ES:CI:BG21:02] |

Spain |

Lozano et al., 2009 |

SPLCCaV-[ES:CI:BG21:02] |

|

|

FJ529203 |

SPLCCaV-[ES:CI:BG25:02] |

Spain |

Lozano et al., 2009 |

SPLCCaV-[ES:CI:BG25:02] |

|

| SPLCShV |

EU309693 |

SPLCV |

China |

GenBank |

SPLCShV-[CN:Sha:07] |

| SPLCGoV |

AF326775 |

SPLCGV-[16] |

USA |

Lotrakul et al., 2003 |

SPLCGoV-[US:Geo:16] |

| MerLCuV-US |

HQ333143 |

SPGVaV-[US:MS:1B-3] |

USA |

Zhang & Ling, 2011 |

MerLCuV-US[US:MS:1B-3:07] |

| MerLCuV-BR |

FJ969829 |

SPGVaV-PA[BR:Bel1] |

Brazil |

Paprotka et al., 2010 |

MerLCuV-BR[BR:PA:Bel1:07] |

| MerLCuV-PR |

DQ644561 |

MeLCV-[PR:N1] |

Puerto Rico |

GenBank |

MeLCuV-PR[PR:N1:06] |

| IYVMaV |

EU839576 |

IYVV-[ES:Mal:IG1:06] |

Spain |

Lozano et al., 2009 |

IYVMaV-[ES:Mal:IG1:06] |

| IYVV |

EU839578 |

IYVV-[ES:Mal:IG5:06] |

Spain |

Lozano et al., 2009 |

IYVV-[ES:Mal:IG5:06] |

|

AJ132548 |

IYVV-[ES:98] |

Spain |

Banks et al., 1999 |

IYVV-[ES:98] |

|

|

EU839577 |

IYVV-[ES:Mal:IG3:06] |

Spain |

Lozano et al., 2009 |

IYVV-[ES:Mal:IG3:06] |

|

| SPLCSPV |

HQ393477 |

SPLCSPV-[BR:AlvM:09] |

Brazil |

Albuquerque et al., 2011 |

SPLCSPV-[BR:SP:AlvM:09] |

| SPMV |

FJ969831 |

SPMaV-[BR:BSB1] |

Brazil |

Paprotka et al., 2010 |

SPMV-[BR:BSB1:07] |

| SPLCSCV |

HQ333144 |

SPLCSCV-[US:SC:648B-9] |

USA |

Zhang & Ling, 2011 |

SPLCSCV-[US:SC:648-B9:06] |

| SPLCUV |

FR751068 |

SPLCUV-[UG:KAMP:08] |

Uganda |

Wasswa et al., 2011 |

SPLCUV-[UG:KAMP:08] |

| SPLCESV |

EF456741 |

SPLCESV-[ES:CI:BG1:02] |

Spain |

Lozano et al., 2009 |

SPLCESV-[ES:CI:BG1:02] |

|

EF456743 |

SPLCESV-[ES:CI:BG5:02] |

Spain |

Lozano et al., 2009 |

SPLCESV-[ES:CI:BG5:02] |

|

|

HQ393448 |

SPLCESV-[BR:BA:Uti:08] |

Brazil |

This study |

SPLCESV-[BR:BA:Uti:08] |

|

|

FJ151200 |

SPLCESV-[ES:Mal:IG2:06] |

Spain |

Lozano et al., 2009 |

SPLCESV-[ES:Mal:IG2:06] |

|

|

HQ393458 |

SPLCESV-[BR:RO:Cac:08] |

Brazil |

This study |

SPLCESV-[BR:RO:Cac:08] |

|

| SPGVV-PB |

HQ393444 |

SPGVV-PB[BR:BA:CA:08] |

Brazil |

This study |

SPGVV-PB[BR:BA:CA:08] |

|

FJ969830 |

SPGVaV-PB1[BR:Sou1] |

Brazil |

Paprotka et al., 2010 |

SPGVV-PB[BR:PB:Sou1:07] |

|

| SPGVV-RO |

HQ393459 |

SPGVV-RO[BR:RO:Cac:08] |

Brazil |

This study |

SPGVV-RO[BR:RO:Cac:08] |

|

HQ393457 |

SPGVV-RO[BR:RO:PV2:08] |

Brazil |

This study |

SPGVV-RO[BR:RO:PV2:08] |

|

|

HQ393454 |

SPGVV-RO[BR:RO:OPO:08] |

Brazil |

This study |

SPGVV-RO[BR:RO:OPO:08] |

|

|

HQ393447 |

SPGVV-RO[BR:BA:Uti:08] |

Brazil |

This study |

SPGVV-RO[BR:BA:Uti:08] |

|

|

HQ393452 |

SPGVV-RO[BR:SE:PV1:08] |

Brazil |

This study |

SPGVV-RO[BR:SE:PV1:08] |

|

| SPLCCNV |

DQ512731 |

SPLCV-[CN] |

China |

Luan et al., 2007 |

SPLCCNV-[CN:05] |

| JF736657 | SPLCV-B3 | China | GenBank | SPLCCNV-[CN:Zhe:10] |

aThe isolates present in this study are shown in bold.

bComplete names of the viruses are shown in the Additional file 2.

Table 2.

Origins of the 34 sweepovirus isolates used in this study

| Sample Origin | Sample | Enzyme | Species | Strain[Isolate] | Acronym | Accession No |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPEGBa |

#167 |

EcoRV |

SPLCVb |

United States[Brazil:Bahia:Cruz das Almas1:2008] |

SPLCV-US[BR:BA:CA1:08] |

HQ393443 |

| SPEGB |

#171 |

SacI |

|

United States[Brazil:Bahia:Cruz das Almas2:2008] |

SPLCV-US[BR:BA:CA2:08] |

HQ393446 |

| SPEGB |

#293 |

EcoRV |

|

United States[Brazil:Para:2008] |

SPLCV-US[BR:PA:08] |

HQ393450 |

| SPEGB |

#325 |

SacI |

|

United States[Brazil:Rondonia:Porto Velho:2008] |

SPLCV-US[BR:RO:PV:08] |

HQ393451 |

| SPEGB |

#337 |

EcoRV |

|

United States[Brazil:Rondonia:Ouro Preto do Oeste:2008] |

SPLCV-US[BR:RO:OPO:08] |

HQ393453 |

| Sao Paulo |

#SP12 |

BamHI |

|

United States[Brazil:Sao Paulo:Alfredo Marcondes1:2009] |

SPLCV-US[BR:SP:AM1:09] |

HQ393471 |

| Sao Paulo |

#SP12 |

SacI |

|

United States[Brazil:Sao Paulo:Alfredo Marcondes2:2009] |

SPLCV-US[BR:SP:AM2:09] |

HQ393472 |

| Sao Paulo |

#SP88 |

BamHI |

|

United States[Brazil:Sao Paulo:Alfredo Marcondes3:2009] |

SPLCV-US[BR:SP:AM3:09] |

HQ393474 |

| Sao Paulo |

#SP130 |

BamHI |

|

United States[Brazil:Sao Paulo:Alfredo Marcondes4:2009] |

SPLCV-US[BR:SP:AM4:09] |

HQ393475 |

| Sao Paulo |

#SP140 |

BamHI |

|

Sao Paulo[Brazil:Sao Paulo:Presidente Prudente:2009] |

SPLCV-SP[BR:SP:PP:09] |

HQ393476 |

| SPEGB |

#134 |

SpeI |

|

Brazil[Brazil:Bahia:Urucuca:2008] |

SPLCV-BR[BR:BA:Uru:08] |

HQ393442 |

| SPEGB |

#171 |

BamHI |

|

Brazil[Brazil:Bahia:Cruz das Almas:2008] |

SPLCV-BR[BR:BA:CA:08] |

HQ393445 |

| SPEGB |

#235 |

BamHI |

|

Brazil[Brazil:Sergipe:Riachao:2008] |

SPLCV-BR[BR:SE:Ria:08] |

HQ393449 |

| SPEGB |

#337 |

SacI |

|

Brazil[Brazil:Rondonia:Ouro Preto do Oeste:2008] |

SPLCV-BR[BR:RO:OPO:08] |

HQ393455 |

| SPEGB |

#370 |

SacI |

|

Brazil[Brazil:Rondonia:Cacoal:2008] |

SPLCV-BR[BR:RO:Cac:08] |

HQ393460 |

| SPEGB |

#346 |

EcoRV |

|

Pernambuco[Brazil:Rondonia:Porto Velho:2008] |

SPLCV-PE[BR:RO:PV:08] |

HQ393456 |

| Paraiba |

#PB82 |

SacI |

|

Pernambuco[Brazil:Paraiba:Pedras de Fogo:2008] |

SPLCV-PE[BR:PB:PF:08] |

HQ393461 |

| Pernambuco |

#PE49 |

BamHI |

|

Pernambuco[Brazil:Penambuco:Camocin de São Félix1:2008] |

SPLCV-PE[BR:PE:CSF1:08] |

HQ393462 |

| Pernambuco |

#PE49 |

SacI |

|

Pernambuco[Brazil:Pernambuco:Camocin de São Félix2:2008] |

SPLCV-PE[BR:PE:CSF2:08] |

HQ393463 |

| Rio Grande do Sul |

#RS9 |

BamHI |

|

Pernambuco[Brazil:Rio grande do Sul:Mariana Pimentel1:2009] |

SPLCV-PE[BR:RS:MP1:09] |

HQ393464 |

| Rio Grande do Sul |

#RS9 |

SacI |

|

Pernambuco[Brazil:Rio Grande do Sul:Mariana Pimentel2:2009] |

SPLCV-PE[BR:RS:MP2:09] |

HQ393465 |

| Rio Grande do Sul |

#RS24 |

SacI |

|

Pernambuco[Brazil:Rio Grande do Sul:Mariana Pimentel4:2009] |

SPLCV-PE[BR:RS:MP4:09] |

HQ393466 |

| Rio Grande do Sul |

#RS29 |

BamHI |

|

Pernambuco[Brazil:Rio Grande do Sul:Mariana Pimentel5:2009] |

SPLCV-PE[BR:RS:MP5:09] |

HQ393467 |

| Rio Grande do Sul |

#RS33 |

BamHI |

|

Pernambuco[Brazil:Rio Grande do Sul:Mariana Pimentel6:2009] |

SPLCV-PE[BR:RS:MP6:09] |

HQ393468 |

| Rio Grande do Sul |

#RS52 |

BamHI |

|

Pernambuco[Brazil:Rio Grande do Sul:Mariana Pimentel7:2009] |

SPLCV-PE[BR:RS:MP7:09] |

HQ393469 |

| Rio Grande do Sul |

#RS52 |

SacI |

|

Pernambuco[Brazil:Rio Grande do Sul:Mariana Pimentel3:2009] |

SPLCV-PE[BR:RS:MP3:09] |

HQ393470 |

| SPEGB |

#171 |

BamHI |

SPGVVc |

Paraiba[Brazil:Bahia:Cruz das Almas:2008] |

SPGVV-PB[BR:BA:CA:08] |

HQ393444 |

| SPEGB |

#184 |

SacI |

|

Rondonia[Brazil:Bahia:Utinga:2008] |

SPGVV-RO[BR:BA:Uti:08] |

HQ393447 |

| SPEGB |

#325 |

SacI |

|

Rondonia[Brazil:Rondonia:Porto Velho1:2008] |

SPGVV-RO[BR:RO:PV1:08] |

HQ393452 |

| SPEGB |

#337 |

EcoRV |

|

Rondonia[Brazil:Rondonia:Ouro Preto do Oeste:2008] |

SPGVV-RO[BR:RO:OPO:08] |

HQ393454 |

| SPEGB |

#346 |

EcoRV |

|

Rondonia[Brazil:Rondonia:Porto Velho2:2008] |

SPGVV-RO[BR:RO:PV2:08] |

HQ393457 |

| SPEGB |

#370 |

BamHI |

|

Rondonia[Brazil:Rondonia:Cacoal:2008] |

SPGVV-RO[BR:RO:Cac:08] |

HQ393459 |

| SPEGB |

#184 |

SpeI |

SPLCESVd |

[Brazil:Bahia:Utinga:2008] |

SPLCESV-[BR:BA:Uti:08] |

HQ393448 |

| SPEGB | #370 | BamHI | [Brazil:Rondonia:Cacoal:2008] | SPLCESV-[BR:RO:Cac:08] | HQ393458 |

a Sweet potato Embrapa Germplasm Bank.

b Sweet potato leaf curl virus.

c Sweet potato golden vein virus.

d Sweet potato leaf curl Spain virus.

Taxonomic and phylogenetic analysis of sweepoviruses

Pairwise comparisons using Clustal V were performed using the sequences determined here and all full-length sweepovirus sequences available in the databases. It is worth noting that a few sweepovirus isolates were likely misclassified according to the taxonomic criteria for geminivirus classification [36] (the proposed new names are shown in Table 1 and Additional File 2). These isolates were SPLCV-Ceara[Brazil:Fortaleza1] (SPLCV-CE[BR:For1], FJ969832), SPLCV-Rio Grande do Sul1[Brazil:Tavares1] (SPLCV-RS1[BR:Tav1], FJ969833) [12], Sweet potato golden vein-associated virus-[United States:Mississipi:1b-3:07] (SPGVaV-[US:MS:1B-3], HQ333143) [11], SPGVaV-Para[Brazil:Belem1] (SPGVaV-PA[BR:Bel1], FJ969829) [12] and Ipomoea yellow vein virus-[Spain:Malaga:IG1:2006] (IYVV-[ES:Mal:IG1:06], EU839576) [6]. The genome of isolate SPLCV-CE[BR:For1] shares <89% nucleotide identity with all other begomovirus sequences (Additional File 2), and in accordance with the cut-off point of 89% identity established for species separation within the genus Begomovirus[35], it most likely belongs to a new species, proposed here as Sweet potato leaf curl Brazil virus (SPLCBRV). The isolate SPLCV-RS1[BR:Tav1] shares >90% identity with SPLCLaV isolates, and we therefore proposed it be classified as Sweet potato leaf curl Lanzarote virus-Brazil[BR:RS:Tav1:07] (SPLCLaV-BR[BR:RS:Tav1:07]). The IYVV-[ES:Mal:IG1:06] sequence shared <89% identity with IYVV-[Spain:1998] and all other begomovirus sequences; it is therefore suggested that it be classified as a new species named Ipomoea yellow vein Malaga virus-[ES:Mal:IG1:06] (IYVMaV-[ES:Mal:IG1:06]). In addition, based on the nucleotide sequence identities found (Additional File 2), we propose that the isolates SPGVaV-[United States:Mississippi:1B-3] (SPGVaV-[US:MS:1B-3], HQ333143), SPGVaV-[Brazil:Belém1] (SPGVaV-PA[BR:Bel1], FJ969829) and Merremia leaf curl virus-[Puerto Rico:N1] (DQ644561) be classified as strains of Merremia leaf curl virus (MerLCuV), specifically MerLCuV-US[US:MS:1B-3:07], MerLCuV-BR[BR:PA:Bel1:07] and MerLCuV-PR[PR:N1:06], respectively.

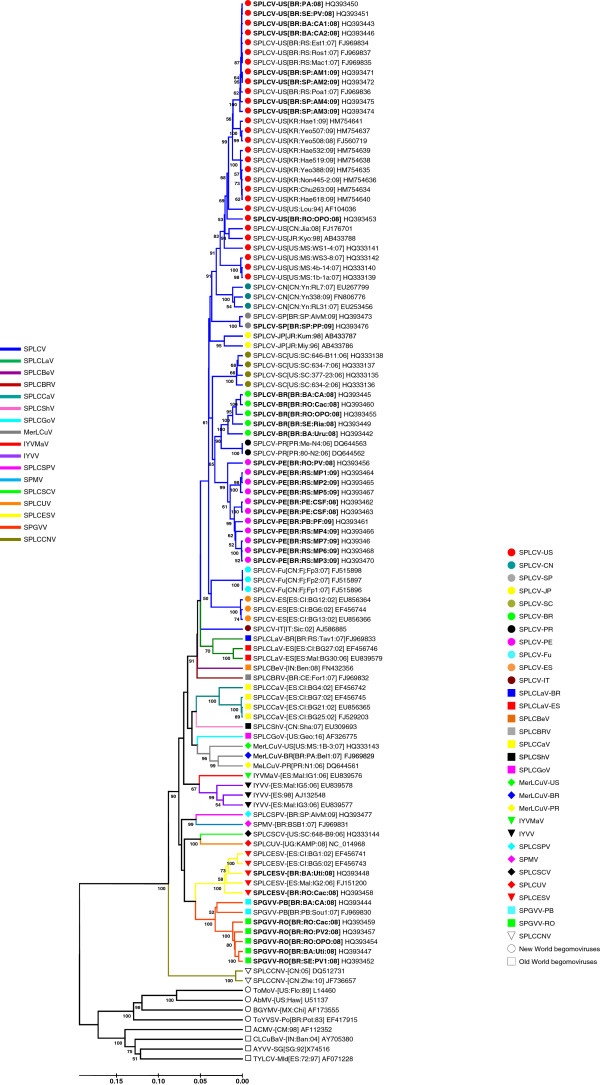

In the UPGMA phylogenetic tree (Figure 1), the sweepovirus sequences were consistently grouped in accordance with the proposed species/strain classification and were separated from both the Old and New World begomoviruses as was expected from the pairwise nucleotide identity analysis (Additional File 2).

Figure 1.

UPGMA phylogenetic tree based on a multiple alignment of the complete sequences of the sweepoviruses described in this work (in bold) and those available in public sequence databases. Branches were bootstrapped with 1,000 replications. Acronyms are described in Table 1. Representative sequences are included for New World (L14460, Tomato mottle virus: ToMoV-[US:Flo:89]; U51137, Abutilon mosaic virus: AbMV-[US:Haw]; AF173555, Bean golden yellow mosaic virus: BGYMV-[MX:Chi]; and EF417915, Tomato yellow vein streak virus: ToYVSV-[BR:Ba3]) and Old World begomoviruses (AF112352, African cassava mosaic virus: ACMV-[CM:98]; AY705380, Cotton leaf curl Burewala virus: CLCuBuV-[IN:Ban:04]; X74516, AYVV-SG[SG:92]; and AF071228, Tomato yellow leaf curl virus: TYLCV-Mdl[ES:72:97]). The scale bar indicates the number of substitutions per site. Bootstrap values >50% are indicated.

Recombination analysis

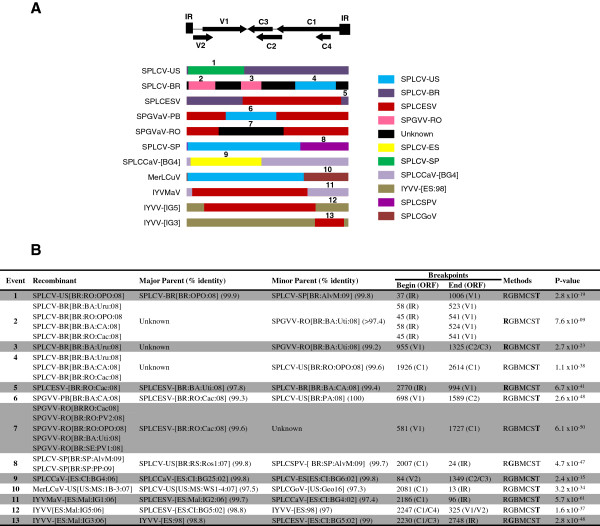

We searched for evidence of recombination in an alignment of all 101 complete sweepovirus sequences. Different methods were used for recombination breakpoint prediction and provided strong evidence for at least 13 recombination events spread across 19 of 101 analyzed genomes (Figure 2). Remarkably, following the adopted criteria (detectable by seven different analytical methods and recombined fragments with ≥97% nucleotide identity with parental sequences), most recombination events were detected among the isolates from the SPEGB. Eight recombination patterns were detected for sequences reported in this work, while five were found in the previously published sweepovirus sequences. The recombination breakpoints were detected between the intergenic region (IR) and V1 (events 1, 2, and 5); V1 and C2/C3 (event 3); C1 and C1 (event 4), V1 and C2 (event 6), V1 and C1 (event 7); V2 and C2/C3 (event 9); C1/C4 and V1/V2 (event 12) and C1 and IR (events 8, 10, 11, and 13) (Figure 2). After analysis with the RDP3 program, the recombination events detected for the sequences reported in this study (events 1–8, Figure 2A, 2B) were tested using the SimPlot program (Figure 3). Every event identified by the RDP3 program was confirmed by Simplot. SPLCV-US[BR:RO:OPO:08] (HQ393453) appeared to be a recombinant (recombination points detected at nucleotide (nt) positions 37 and 1006) of the putative parental-like strains SPLCV-SP[BR:SP:AlvM:09] (HQ393476) and SPLCV-BR[BR:RO:OPO:08] (HQ393455) (Figure 3A). Among the isolates from the SPLCV-BR strain, SPLCV-BR[BR:BA:Uru:08] (HQ393442) contained three recombination events (event 2, breakpoints at nucleotide positions 58–523; event 3, nt positions 955–1325 and event 4, nt positions 1926–2614), three putative parental-like strains: SPGVV-RO[BR:BA:Uti:08] (HQ393447), SPLCV-US[BR:RO:OPO:08] (HQ393453) and an unknown sequence (Figure 3B). For the SPLCV-BR isolates [BR:BA:CA:08] and [BR:RO:Cac:08], two recombinant events were detected (event 2, nt positions 45–541 and event 4, nt positions 1926–2614), whereas SPLCV-BR[BR:RO:OPO:08] contained only event 2 (Figure 2B). The isolate SPLCESV-[BR:RO:Cac:08] (HQ393458) was identified as a recombinant (between nt positions 994–2770) of SPLCV-BR[BR:BA:CA:08] (HQ393445) and SPLCESV-[BR:BA:Uti:08] (HQ393448) (Figure 3C). When SPGVV-PB[BR:BA:CA:08] (HQ393444) was used as a query sequence, a recombinant breakpoint (event 6, nt positions 698–1589) with two putative parental-like viruses, SPLCESV-[BR:RO:Cac:08] and SPLCV-US[BR:PA:08] (HQ393450) (Figure 3D) was identified. In contrast, when SPGVV-RO[BR:RO:Cac:08] (HQ393459) was used as a query sequence, a recombinant breakpoint at nt positions 581–1727 (event 7) was identified with two putative parental-like viruses, SPLCESV-[BR:RO:Cac:08] and an unknown sequence (Figure 3E). The remaining four SPGVV-RO sequences contained the same recombination event observed for SPGVV-RO[BR:RO:Cac:08] (Figure 2B). Finally, when the analysis was performed for SPLCV-SP[BR:SP:PP:09] (HQ393476), two different recombination points (at nt positions 24–2007) and two putative parental strains, SPLCV-US[BR:RS:Ros1:07] (FJ969837) and SPLCSPV-[BR:SP:AlvM:09] (HQ393477), were detected (Figure 3F).

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of recombination events (A) and details of the recombination breakpoints (B) detected in sweepoviruses. The genome organization of a typical sweepovirus is shown at the top of the figure. Each genome is represented by an open box, colored according to the isolate. Numbers indicate recombination events described in B. R, G, B, M, C, S and T indicate detection by RDP, GENCONV, BOOTSCAN, MAXCHI, CHIMAERA, SISCAN and 3SEQ methods, respectively, with the presented highest p-value being that determined by the method indicated in bold type.

Figure 3.

Evidence of recombination events in Brazilian sweepoviruses (A) SPLCV-US[BR:RO:OPO:08], (B) SPLCV-BR[BR:BA:Uru:08], (C) SPLCESV-[BR:RO:Cac:08], (D) SPGVV-PB[BR:BA:CA:08], (E) SPGVV-RO[BR:RO:Cac:08] and (F) SPLCV-SP[BR:SP:PP:09]. SimPlot analyses were performed with full genome sequence alignments using the Window 200bp, Step 20bp, GapStrip on Kimura (2-parameter) method. Recombination points are shown by vertical lines.

Discussion

RCA (rolling circle amplification) has greatly facilitated the cloning of geminivirus genomes. This is especially true for sweet potato samples, as DNA extraction is difficult due to the high polysaccharide content [37]. Because RCA-based methods may start from a low amount of template DNA, sample dilution is sufficient to avoid the harmful effects of contaminating substances. In total, 34 complete sweepovirus genomes were isolated from sweet potato samples collected from a sweet potato germplasm bank (SPEGB) and commercial fields across four Brazilian states. Based on ICTV guidelines [36], the isolates belong to new strains of SPLCV [38] (strains SPLCV-BR and SPLCV-PE), and of SPGVV [12] (strain SPGVV-RO), and 13 other isolates are considered to be variants of SPLCV-US [38], SPLCV-SP [13] and SPLCESV [6].

A thorough pairwise comparison of all of the sweepovirus sequences available in the databases along with the 34 sequences reported here was performed, and it appeared that four viral isolates were not appropriately classified; hence, their classification was reviewed according to ICTV guidelines. We found that the isolates described as SPLCV-CE [12] and IYVV-[ES:IG1] [6] would be better classified as novel species, suggested here as Sweet potato leaf curl Brazil virus (SPLCBRV) and Ipomoea yellow vein Malaga virus (IYVMaV), respectively. Additionally, the SPLCV-RS1 isolate [12] may be classified as a new strain of SPLCLaV [6], and the name Sweet potato leaf curl Lanzarote virus-Brazil (SPLCLaV-BR) is proposed. Thus, it is suggested that all SPLCLaV isolates from Spain be classified as SPLCLaV-ES. Similarly, the isolates designated as SPGVaV-[US:MS:1B-3], SPGVaV-PA[BR:Bel1] and Merremia leaf curl virus-[PR:N1] (MeLCV-[PR:N1]) would be better renamed Merremia leaf curl virus-[US:MS:1B-3:07] (MerLCuV-US-[US:MS:1B-3:07]), MerLCuV-BR[BR:PA:Bel1:07] and MerLCuV-[PR:N1:06], respectively. Additionally, we suggest eliminating the term “associated” from the virus names, as symptom expression was not studied for any of the species. Finally, it was concluded that 44 of 67 sequences should be designated as strains (Table 1). This result clearly illustrates the complexity of sweepovirus taxonomy and nomenclature. Therefore, a set of modifications is suggested for updating the sweepovirus nomenclature and facilitating the interpretation of sweepovirus phylogenetic analysis (Table 1 and Figure 1).

The phylogenetic analysis demonstrated that the sweepovirus diversity found in the SPEGB samples is higher than in samples collected from commercial fields. In the SPEGB samples (n=10), three species (SPLCV, SPGVV and SPLCESV), five strains (SPLCV-US, SPLCV-BR, SPLCV-PE, SPGVV-PB and SPGVV-RO) and 11 recombinants were found, while in commercial fields (n=11), only one species (SPLCV) and three different strains (SPLCV-US, SPLCV-SP and SPLCV-PE) were observed. Moreover, co-infections were found solely in the SPEGB samples, although they have been shown to be frequent in field samples from other countries [6,11]. This could be explained by the vegetative propagation of sweet potato that favors viral accumulation in the roots, the maintenance of many sweet potato entries collected throughout Brazil and abroad in the same confined screenhouse, and the presence of whiteflies (Bemisia tabaci) in the germplasm bank facilities. Of the approximately 1400 entries in the SBEGB, nine are from Argentina, the USA, Paraguay, Japan and Spain, and 173 were received from the International Potato Center (CIP), Peru, as supposedly virus-free in vitro seedlings. The seedlings were maintained in vivo for at least three years, and this might have resulted in the natural spread of the begomoviruses present in some plants, thus enabling recombinations to occur. Virus-free plants or seeds will be produced to reduce the negative effect of virus infection for the breeding program.

Patterns of inter-species/strain geminivirus recombination and a number of hot- and cold-spots have been described among members of the genus Begomovirus[32,39-41]. We therefore analyzed the recombination breakpoints detected within the sweepovirus dataset and a number of recombination events were identified. In some cases (Figure 3A, C, D and F), the recombinants appeared to be the result of recent recombination events because a low mutation rate was observed in this region (data not shown). Most of the recombination breakpoints occur in the IR (detected between nt positions 2770 and 96) and in the middle of the C1 ORF (between nt positions 2000 and 2250) (Figure 2A). Similarly, three recombination breakpoints (events 1, 3 and 5) were identified next to the end of the V1 ORF (Figure 2A). These results are consistent with those obtained from geminivirus recombination analyses, which show that the Rep, the IR and the interface between ORFs V1 and C3 are recombination hot-spots [29,40,42,43]. Lefeuvre et al.[40] also described the presence of a recombination cold-spot within the V2 ORF and the third quarter of the V1 ORF of begomoviruses; here, however, we detected the occurrence of recombination breakpoints in the first half of the V1 ORF. Some sweepovirus recombination events have been previously described [6,11], and most were confirmed in our study (events 9–13, Figure 2). The detection of similar recombination patterns agrees with the recent hypothesis that the recombination sites are non-randomly distributed along the geminivirus genome [29,39,44]. The observed recombination patterns are most likely due to the existence of regions with higher biochemical and biophysical predisposition and with tolerance for recombination. The experimental generation of recombinants has shown that the IR and V1/C3 interface is a recombination hot-spot [43], and this can be explained by the fact that recombinants derived from recombination breakpoints that occur outside the genes are generally more viable than those occurring within the genes [29]. In addition to sequence homology, secondary structural features might also favor the occurrence of recombination [43]. In our case, we detected a number of recombination breakpoints in the Rep and this was also observed among other geminiviruses [26,29,45].

Conclusions

Our study shows that the genetic diversity of sweepoviruses both in the SPEGB and commercial crops in Brazil is considerably greater than previously reported by Paprotka et al.[12] and highlights the importance of recombination in the evolution of these viruses. These results indicate that recombination events are apparently responsible for the emergence of sweepovirus strains and species, although alterations in host range, cell tropism, viral symptoms and pathogenicity remain to be elucidated. Recently, the generation of the first infectious clone of a sweepovirus, SPLCLaV, was described [16], which is especially important as it opens the possibility of understanding the various aspects of pathogenicity as well as its potential use in breeding virus-resistant sweet potatoes. Studies on viral diversity in particular regions provide important information enabling recommendations for viral control strategies and are essential for identifying species/strains from which to select isolates for screening tests for resistant germplasm. Finally, studies on viral diversity are necessary for comprehending how sweepovirus diversification results from propagative material exchange within the country. The ‘in vivo’ maintenance of vegetatively propagated plants in a germplasm bank has proven to be a risky strategy because it may enable or accelerate the generation of new species/strains that can spread to nature if isolation conditions are not sufficient to maintain the bank free of insect vectors.

Methods

Collection of leaf samples and DNA extraction

Sweet potato leaf samples showing a variety of symptoms, including vein thickening, chlorosis, curling, mottling and distortion, were collected from the sweet potato germplasm bank of Embrapa Vegetables (Brasilia-DF, Brazil) (SPEGB) and commercial fields across four Brazilian states (Table 2). Total DNA was extracted following the protocol described by Doyle and Doyle [46].

Cloning strategy

Circular geminiviral DNA was amplified by rolling-circle amplification (RCA) using φ-29 DNA polymerase (TempliPhi kit, GE Healthcare) as described by Inoue-Nagata et al.[47]. RCA products were digested with a set of restriction enzymes (BamHI, EcoRI, EcoRV, HindIII, KpnI, PstI, SacI, SacII, SpeI and XbaI) to identify unique sites for cloning the full-length genomes (~2.8 kb). The restricted fragments corresponding to putative full-length monomer genomes were cloned into the vector pBluescript SK(+) (Stratagene, California, USA) and fully sequenced at Macrogen Inc. (Seoul, South Korea). One to two enzymes were finally selected for cloning the viral genomes present in each sample (Table 2).

Genetic diversity

Pairwise nucleotide identity comparisons were calculated using Clustal V [48] (included in MegAlign DNASTAR Inc., Madison, WI, USA). As recommended by the ICTV Geminiviridae Study Group, viruses with nucleotide identity between full-genome sequences of <89% were considered as distinct species, while those with <94% were considered distinct strains of the same species [36].

Phylogenetic analysis

Full genome sequences from 34 virus isolates obtained from 21 samples analyzed in this study (Table 2) and the 67 complete sweepovirus sequences available in public sequence databases ( http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) as of October 2011 (Table 2) were aligned using Muscle [49]. The phylogenetic relationships were inferred using UPGMA with 1,000 bootstrap replicates, and the evolutionary distances were calculated using the p-distances method implemented in MEGA 5 [50].

Recombination analysis

All sweepovirus sequences used in this study (Table 1) were aligned using Muscle with default settings [49], and the detection of potential recombinant sequences, the identification of likely parental sequences and the localization of possible recombination breakpoints were performed using RDP [51], GENCONV [26], BOOTSCAN [52], MAXICHI [53], CHIMAERA [54], SiScan [55] and 3SEQ [56] methods implemented in the RDP3 program [57]. Default settings were used throughout. Only those potential recombination events detected using all of the methods described above and involving fragments sharing ≥97% sequence identity with their parental sequences were considered. Putative recombination events were analyzed with the SimPlot program [58] using the putative recombinant sequence as a query.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

LCA and BP performed the experiments. LCA, AKIN, ROR, EM and JN-C were involved in data analysis. JN-C provided overall direction and experimental design. LCA, AKIN, ROR, EM and JN-C wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Iterative elements [I, II and III direct (virion-sense) and IV inverted (complementary-sense) repeats] and corresponding iteron-related domains in the 5′-terminal regions of the Rep gene (Rep IRD) of sweepoviruses. Presumed iteron and Rep IRD sequences are colored as follows, blue for the IYVV, SPLCV-ES and SPLCV-IT group; pink for SPLCV-US[Lou:24]; and green for SPLCESV. The three different Rep IRDs present in this study are shown in bold.

Sweepovirus information: Complete names and color representations of the pairwise sequence identity percentages (calculated with Clustal V, included in MegAlign-DNASTAR) of the complete genome sequences of sweepovirus isolates reported here and those available in the public sequence databases. The isolates present in this study are shown in bold.

Contributor Information

Leonardo C Albuquerque, Email: lcdalbuquerque@yahoo.com.br.

Alice K Inoue-Nagata, Email: alicenag@cnph.embrapa.br.

Bruna Pinheiro, Email: brunapinheiro88@gmail.com.

Renato O Resende, Email: rresende@unb.br.

Enrique Moriones, Email: moriones@eelm.csic.es.

Jesús Navas-Castillo, Email: jnavas@eelm.csic.es.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Dr. João Bosco Carvalho Silva, Dr. Simone da Graça Ribeiro and Dr. Amaríllis Rós Golla for assistance with sample collection and Dr. Arvind Varsani for critically reading the manuscript. In Brazil, this study was funded by CNPq project 304079/2009-0. The work in Spain was partially performed within the frame of the network 111RT0433 from Fundación CYTED. JN-C and EM are members of the Research Group AGR-214, partially funded by the Consejería de Economía, Innovación y Ciencia, Junta de Andalucía, Spain (co-financed by FEDER-FSE). LCA is sponsored by CNPq (561405/2008-5), and Capes, and ROR and AKIN are CNPq fellows.

References

- FAO Statistical Databases. [ http://faostat.fao.org/]

- Clark CA, Davis JA, Abad JA, Cuellar WJ, Fuentes S, Kreuze JF, Gibson RW, Mukasa SB, Tugume AK, Tairo FD, Valkonen JPT. Sweetpotato Viruses: 15 Years of Progress on Understanding and Managing Complex Diseases. Plant Dis. 2012;96:168–185. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-07-11-0550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lotrakul P, Valverde RA. Cloning of a DNA-A-like genomic component of sweet potato leaf curl virus: nucleotide sequence and phylogenetic relationships. Molecular Plant Pathology Online. 1999. http://www.bspp.org.uk/mppol/1999/0422lotrakul/index.htm.

- Lotrakul P, Valverde RA, Clark CA, Fauquet CM. Properties of a begomovirus isolated from sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas (L.) Lam.) infected with Sweet potato leaf curl virus. Revista Mexicana de Fitopatologia. 2003;21:128–136. [Google Scholar]

- Fuentes S, Salazar LF. First report of Sweet potato leaf curl virus in Peru. Plant Dis. 2003;87:98–98. doi: 10.1094/PDIS.2003.87.1.98C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lozano G, Trenado HP, Valverde RA, Navas-Castillo J. Novel begomovirus species of recombinant nature in sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas) and Ipomoea indica: taxonomic and phylogenetic implications. J Gen Virol. 2009;90:2550–2562. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.012542-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luan YS, Zhang J, Liu DM, Li WL. Molecular characterization of sweet potato leaf curl virus isolate from China (SPLCV-CN) and its phylogenetic relationship with other members of the Geminiviridae. Virus Genes. 2007;35:379–385. doi: 10.1007/s11262-007-0084-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luan YS, Zhang J, An LJ. First report of Sweet potato leaf curl virus in China. Plant Dis. 2006;90:1111. doi: 10.1094/PD-90-1111C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briddon RW, Bull SE, Bedford ID. Occurrence of Sweet potato leaf curl virus in Sicily. Plant Pathology. 2006;55:286–286. [Google Scholar]

- Wasswa P, Otto B, Maruthi MN, Mukasa SB, Monger W, Gibson RW. First identification of a sweet potato begomovirus (sweepovirus) in Uganda: characterization, detection and distribution. Plant Pathology. 2011;60:1030–1039. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3059.2011.02464.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang SC, Ling KS. Genetic diversity of sweet potato begomoviruses in the United States and identification of a natural recombinant between Sweet potato leaf curl virus and Sweet potato leaf curl Georgia virus. Arch Virol. 2011;156:955–968. doi: 10.1007/s00705-011-0930-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paprotka T, Boiteux LS, Fonseca MEN, Resende RO, Jeske H, Faria JC, Ribeiro SG. Genomic diversity of sweet potato geminiviruses in a Brazilian germplasm bank. Virus Res. 2010;149:224–233. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2010.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albuquerque LC, Inoue-Nagata AK, Pinheiro B, Ribeiro Sda G, Resende RO, Moriones E, Navas-Castillo J. A novel monopartite begomovirus infecting sweet potato in Brazil. Arch Virol. 2011;156:1291–1294. doi: 10.1007/s00705-011-1016-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fauquet CM, Stanley J. Geminivirus classification and nomenclature: progress and problems. Ann Appl Biol. 2003;142:165–189. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7348.2003.tb00241.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Briddon R, Patil B, Bagewadi B, Nawaz-ul-Rehman M, Fauquet C. Distinct evolutionary histories of the DNA-A and DNA-B components of bipartite begomoviruses. BMC Evol Biol. 2010;10:97. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-10-97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trenado HP, Orílio AF, Márquez-Martín B, Moriones E, Navas-Castillo J. Sweepoviruses cause disease in sweet potato and related Ipomoea spp.: fulfilling Koch’s postulates for a divergent group in the genus Begomovirus. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e27329. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks GK, Bedford ID, Beitia FJ, Rodriquez-Cerezo E, Markham PG. A novel geminivirus of Ipomoea indica(Convolvulacae) from southern Spain. Plant Dis. 1999;83:486. doi: 10.1094/PDIS.1999.83.5.486B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark CA, Hoy MW. Effects of common viruses on yield and quality of beauregard sweet potato in Louisiana. Plant Dis. 2006;90:83–88. doi: 10.1094/PD-90-0083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valverde RA, Clark CA, Valkonen JPT. Viruses and virus disease complexes of sweetpotato. Plant Viruses. 2007;1:116–126. [Google Scholar]

- Rojas MR, Hagen C, Lucas WJ, Gilbertson RL. Exploiting chinks in the plant's armor: Evolution and emergence of geminiviruses. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 2005;43:361–394. doi: 10.1146/annurev.phyto.43.040204.135939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley J, Bisaro DM, Briddon RW, Brown JK, Fauquet CM, Harrison BD, Rybicki EP, Stenger DC. In: Virus Taxonomy Classification and Nomenclature of Viruses Eighth Report of the International Committee on the Taxonomy of Viruses. Fauquet CM, Mayo MA, Maniloff J, Desselberger U, Ball LA, editor. Amsterdam: Elsevier Academic Press; 2005. Family Geminiviridae; pp. 301–326. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison BD. Advances in geminivirus research. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 1985;23:55–82. doi: 10.1146/annurev.py.23.090185.000415. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Padidam M, Beachy RN, Fauquet CM. The role of AV2 ("Precoat") and coat protein in viral replication and movement in tomato leaf curl geminivirus. Virology. 1996;224:390–404. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noueiry AO, Lucas WJ, Gilbertson RL. Two proteins of a plant DNA virus coordinate nuclear and plasmodesmal transport. Cell. 1994;76:925–932. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90366-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briddon RW, Bedford ID, Tsai JH, Markham PG. Analysis of the nucleotide sequence of the treehopper-transmitted geminivirus, Tomato pseudo-curly top virus, suggests a recombinant origin. Virology. 1996;219:387–394. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padidam M, Sawyer S, Fauquet CM. Possible emergence of new geminiviruses by frequent recombination. Virology. 1999;265:218–225. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.0056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanz AI, Fraile A, Garcia-Arenal F, Zhou X, Robinson DJ, Khalid S, Butt T, Harrison BD. Multiple infection, recombination and genome relationships among begomovirus isolates found in cotton and other plants in Pakistan. J Gen Virol. 2000;81:1839–1849. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-81-7-1839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umaharan P, Padidam M, Phelps RH, Beachy RN, Fauquet CM. Distribution and diversity of geminiviruses in Trinidad and Tobago. Phytopathology. 1998;88:1262–1268. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO.1998.88.12.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefeuvre P, Martin DP, Hoareau M, Naze F, Delatte H, Thierry M, Varsani A, Becker N, Reynaud B, Lett JM. Begomovirus 'melting pot' in the south-west Indian Ocean islands: molecular diversity and evolution through recombination. J Gen Virol. 2007;88:3458–3468. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.83252-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monci F, Sanchez-Campos S, Navas-Castillo J, Moriones E. A natural recombinant between the geminiviruses Tomato yellow leaf curl Sardinia virus and Tomato yellow leaf curl virus exhibits a novel pathogenic phenotype and is becoming prevalent in Spanish populations. Virology. 2002;303:317–326. doi: 10.1006/viro.2002.1633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Andres S, Monci F, Navas-Castillo J, Moriones E. Begomovirus genetic diversity in the native plant reservoir Solanum nigrum: Evidence for the presence of a new virus species of recombinant nature. Virology. 2006;350:433–442. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owor BE, Martin DP, Shepherd DN, Edema R, Monjane AL, Rybicki EP, Thomson JA, Varsani A. Genetic analysis of maize streak virus isolates from Uganda reveals widespread distribution of a recombinant variant. J Gen Virol. 2007;88:3154–3165. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.83144-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arguello-Astorga GR, Guevara-Gonzalez RG, Herrera-Estrella LR, Rivera-Bustamante RF. Geminivirus replication origins have a group-specific organization of iterative elements: A model for replication. Virology. 1994;203:90–100. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Argüello-Astorga GR, Ruiz-Medrano R. An iteron-related domain is associated to Motif 1 in the replication proteins of geminiviruses: identification of potential interacting amino acid–base pairs by a comparative approach. Arch Virol. 2001;146:1465–1485. doi: 10.1007/s007050170072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fauquet CM, Bisaro DM, Briddon RW, Brown JK, Harrison BD, Rybicki EP, Stenger DC, Stanley J. Revision of taxonomic criteria for species demarcation in the family Geminiviridae, and an updated list of begomovirus species. Arch Virol. 2003;148:405–421. doi: 10.1007/s00705-002-0957-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fauquet CM, Briddon RW, Brown JK, Moriones E, Stanley J, Zerbini M, Zhou X. Geminivirus strain demarcation and nomenclature. Arch Virol. 2008;153:783–821. doi: 10.1007/s00705-008-0037-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varadarajan G, Prakash C. A rapid and efficient method for the extraction of total DNA from the sweet potato and its related species. Plant Molecular Biology Reporter. 1991;9:6–12. doi: 10.1007/BF02669284. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lotrakul P, Valverde RA, Clark CA, Sim J, De La Torre R. Detection of a geminivirus infecting sweet potato in the United States. Plant Dis. 1998;82:1253–1257. doi: 10.1094/PDIS.1998.82.11.1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasanna HC, Rai M. Detection and frequency of recombination in tomato-infecting begomoviruses of South and Southeast Asia. Virology Journal. 2007;4:111. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-4-111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefeuvre P, Lett JM, Reynaud B, Martin DP. Avoidance of protein fold disruption in natural virus recombinants. PLoS Pathogens. 2007;3:e181. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patil BL, Fauquet CM. Cassava mosaic geminiviruses: actual knowledge and perspectives. Mol Plant Pathol. 2009;10:685–701. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2009.00559.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefeuvre P, Lett JM, Varsani A, Martin DP. Widely conserved recombination patterns among single-stranded DNA viruses. J Virol. 2009;83:2697–2707. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02152-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Andres S, Tomas DM, Sanchez-Campos S, Navas-Castillo J, Moriones E. Frequent occurrence of recombinants in mixed infections of tomato yellow leaf curl disease-associated begomoviruses. Virology. 2007;365:210–219. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2007.03.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeske H, Luetgemeier M, Preiss W. DNA forms indicate rolling circle and recombination-dependent replication of Abutilon mosaic virus. EMBO Journal. 2001;20:6158–6167. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.21.6158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varsani A, Shepherd DN, Monjane AL, Owor BE, Erdmann JB, Rybicki EP, Peterschmitt M, Briddon RW, Markham PG, Oluwafemi S. et al. Recombination, decreased host specificity and increased mobility may have driven the emergence of Maize streak virus as an agricultural pathogen. J Gen Virol. 2008;89:2063–2074. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.2008/003590-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle JJ, Doyle JL. A rapid isolation procedure for small quantities of fresh leaf tissue. Phytochemical Bulletin. 1987;19:11–15. [Google Scholar]

- Inoue-Nagata AK, Albuquerque LC, Rocha WB, Nagata T. A simple method for cloning the complete begomovirus genome using the bacteriophage phi29 DNA polymerase. J Virol Methods. 2004;116:209–211. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2003.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins DG, Bleasby AJ, Fuchs R. Clustal V - improved software for multiple sequence alignment. Computer Applications in the Biosciences. 1992;8:189–191. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/8.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar RC. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:1792–1797. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA5: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol Biol Evol. 2011;28:2731–2739. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin DP, Rybicki EP. RDP: detection of recombination amongst aligned sequences. Bioinformatics. 2000;15:562–563. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/16.6.562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin DP, Posada D, Crandall KA, Williamson CA. A modified bootscan algorithm for automated identification of recombinant sequence and recombination breakpoints. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 2005;21:98–102. doi: 10.1089/aid.2005.21.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JM. Analyzing the mosaic structure of genes. J Mol Evol. 1992;34:126–129. doi: 10.1007/BF00182389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posada D, Crandall KA. The effect of recombination on the accuracy of phylogeny estimation. J Mol Evol. 2002;54:396–402. doi: 10.1007/s00239-001-0034-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs MJ, Armstrong JS, Gibbs AJ. Sister-Scanning: a Monte Carlo procedure for assessing signals in recombinant sequences. Bioinformatics. 2000;16:573–582. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/16.7.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boni MF, Posada D, Feldman MW. An exact nonparametric method for inferring mosaic structure in sequence triplets. Genetics. 2007;176:1035–1047. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.068874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin DP, Lemey P, Lott M, Moulton V, Posada D, Lefeuvre P. RDP3: a flexible and fast computer program for analyzing recombination. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2462–2463. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lole KS, Bollinger RC, Paranjape RS, Gadkari D, Kulkarni SS, Novak NG, Ingersoll R, Sheppard HW, Ray SC. Full-length Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 genomes from subtype C-infected seroconverters in India, with evidence of intersubtype recombination. J Virol. 1999;73:152–160. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.1.152-160.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Iterative elements [I, II and III direct (virion-sense) and IV inverted (complementary-sense) repeats] and corresponding iteron-related domains in the 5′-terminal regions of the Rep gene (Rep IRD) of sweepoviruses. Presumed iteron and Rep IRD sequences are colored as follows, blue for the IYVV, SPLCV-ES and SPLCV-IT group; pink for SPLCV-US[Lou:24]; and green for SPLCESV. The three different Rep IRDs present in this study are shown in bold.

Sweepovirus information: Complete names and color representations of the pairwise sequence identity percentages (calculated with Clustal V, included in MegAlign-DNASTAR) of the complete genome sequences of sweepovirus isolates reported here and those available in the public sequence databases. The isolates present in this study are shown in bold.