Abstract

The aim of this study was to understand the relationship between egalitarianism, dominance, and intimate partner violence within the context of couples’ dynamics. In particular, it was hypothesized that dominance and sexist attitudes would have both self and partner effects on relationship aggression. To test this hypothesis, gender role egalitarianism, dominance/control, sexism, power dynamics, and aggression were assessed using several measures. Questionnaires for these measures were completed by 87 heterosexual dyads. The relationship between female and male scores on the dominance, egalitarianism, sexism, and intimate partner violence scales were examined using Actor-Partner Interdependence Model (APIM). Findings indicated that the APIM model provided a satisfactory fit to the data*. For both sexes, dominance had more explanatory power than sexism and egalitarianism when all else was controlled in the model. Furthermore, contrary to our expectation, male egalitarian attitude had no significant actor or partner effect on relationship aggression, while female egalitarian attitude had significant actor and partner effects on relationship aggression. Dyadic analysis indicated that cultural pointers of patriarchy, such as egalitarianism among young college students, were not associated with male-to-female violence. The sample size might also have an effect on this result in that a larger sample with older participants might yield different results.

Intimate partner violence is a significant social problem throughout the world and is often persistent. Violence in intimate relationships can occur in physical forms such as hitting, kicking, and choking and in emotional forms such as verbal assault, dominance, control, isolation, ridicule, use of intimate knowledge for degradation, and threats of violence directed toward an individual (Goodman, Koss, Fitzgerald, Russo, & Keita, 1993; Hamby, 1996; Katz & Arias, 1999; Marshall, 1999; Stets, 1990; Straus, 1979; Tolman, 1999). However, regardless of the form, intimate partner violence has serious consequences.

Researchers have focused on the prevalence of intimate partner violence not only among married couples, but among cohabitating and dating couples as well. Prevalence rates for violence among non-married heterosexual couples have been consistently cited at about 25% (Cate, Henton, Koval, Christopher, & Lloyd, 1982), but some research suggests even higher rates. Statistics indicate that the occurrence rate of intimate partner violence, including physical aggression and verbal aggression, ranges between 20% and 60% among college-aged dating couples (Gryl, Stith, & Bird, 1991). A more recent study by Próspero and Vohra-Gupta (2007) found that intimate partner violence continues to be highly prevalent among both male and female college students in dating relationships, with 86% of respondents reporting psychological, physical, and/or sexual victimization.

Some relationships suffer from conflict-related outbursts of violence, in which either partner may ‘lose control’ and consequently act violently (Johnson, 1995). This form of violence rarely escalates into more injurious or life-threatening behaviors (Johnson, 1995; Waltz, Babcock, Jacobson, & Gottman, 2000), and it occurs in a larger number of households than do more severe forms of violence. On the other hand, some relationships suffer from more systematic male violence, which is deeply rooted in the patriarchal traditions of men controlling ‘their’ women (Johnson, 1995). This form of violence involves systematic acts of violence, as well as economic subordination, threats, isolation and other control tactics. In due course, these types of batterers tend to intensify the severity of their violent behaviors by time (Johnson, 1995).

Studies examining men’s and women’s use of physical violence indicate that the number of women using physical aggression is either comparable to that of men (e.g. Archer, 2000; Stets & Straus, 1992) or higher than that of men (e.g., Ferraro & Moe, 2003; Gryl, Stith, & Bird, 1991). However, findings consistently indicate greater rates of deteriorating physical and emotional health over time among female victims (Archer, 2000). As a consequence of severe intimate partner violence, women are more likely than men to take time off work and require medical attention (Stets & Straus, 1990). They are also more likely to suffer from depression, suicidal thoughts and attempts, lowered self esteem, alcohol and substance abuse, and posttraumatic stress disorder (Dutton, Green, Kaltman, Roesch, Zeffiro & Krause, 2006; Lemon, Veroek-Oftedahl & Donnelly, 2002).

Violence within the family can also have significant consequences for other family members who are not directly a victim. Intimate partner violence has been associated with long-lasting, intense, and negative emotional and behavioral influences on children who witness domestic violence (Jaffe & Sudderman, 1995). People who have witnessed violence during their childhood are more likely to assault their siblings and their parents, commit violent crimes outside the family, and assault their own intimate partners when compared to people who have not witnessed violence between their parents (Jaffe & Sudderman, 1995).

The patriarchal social system is perceived by many feminist perspectives as justifying and condoning physical violence against women (Yllo & Straus, 1990). According to some of these perspectives, gender inequality in patriarchal social systems ensures that men have more resources available to them than women (Smith, 1990). Furthermore, society imparts men with a sense of entitlement to control women within their intimate relationships (Ehrensaft & Vivian, 1999). This imbalance in resources may manifest itself as submission of women in male-dominated families or as economic dependence of the female partner. Previous studies have suggested that dependency, submission, and transgression add to dominance, which in turn contributes to intimate partner violence (Choi & Ting, 2008).

Other research using a power inequality perspective indicated that an imbalance of economic resources within the couple underlies the use of violence (Fox, Benson, DeMaris, & Van Wyk, 2002). Cross-cultural and ethnographic studies of spousal violence against women show that male-to-female abuse is less likely to occur in societies where women have strong and close bonds to their families or co-workers. On the contrary, spousal violence is more likely to occur when males dominate all aspects of family life (Kruttschnitt, 1995). Fox et al., (2002) found that women’s vulnerability to harm increases when they live in a disadvantaged neighborhood and have a large number of children. Research along these lines also shows that economically dependent women lack the power to adopt economic or social sanctions against their perpetrators (Sagrestano, Heavey & Christensen, 1999; Yount, 2005).

In families in which women are not economically disadvantaged, men may still resort to physical violence to reassure their masculine identity when they do not feel they are fulfilling their primary provider role, especially in comparison with the economic contributions of their female partners. This violence is triggered by men’s need to compensate for the loss of esteem they experience when they cannot economically contribute as much as their spouses (Choi & Ting, 2008). According to Ehrensaft and Vivian (1999), aggressive men tend to view their own control over their partner as acceptable, but they are particularly sensitive to the feeling of being controlled by their partners—and they may behave aggressively to reassert control. Even after controlling for marital adjustment, income, and communication patterns, Sagrestano et al. (1999) found that couples experience more verbal aggression and violence when the husband thinks that he has less power than his wife.

Lawson’s (2008) study indicated that more hostile-dominance patterns among men are associated with more severe intimate partner violence. However, Strauss (2008) found that dominance is associated with an increased probability of violence regardless of the gender of the partner. Motivated by these results, this study aimed to investigate the relationship between egalitarianism, dominance, and intimate partner violence within the context of couples’ dynamics. In particular, we hypothesized that dominance and sexist attitudes would have both self and partner effects on relationship aggression. Sexist attitudes, such as lack of egalitarian attitudes and a greater degree of benevolent and hostile sexism, were hypothesized to be related to both self and partner relationship aggression. Furthermore, the need for dominance/control, a greater degree of authority, restrictiveness, and disparagement were hypothesized to be associated with increased risk of behaving aggressively for both self and partner in the relationship.

In this study, these hypotheses were tested using an actor partner interdependence model (APIM). This model incorporated measures of dominance (authority, restrictiveness, and disparagement) and sexist attitudes (egalitarian attitudes, hostile sexism, and benevolent sexism) to explain relationship aggression (physical and verbal aggression).

Methods

Participants

The participants of this study included 87 heterosexual dyads recruited from a large Midwestern university campus. The age of the participants forming these dyads ranged from 18 to 53 (M=22.3, SD=4.80). Of the 87 dyads, 21% (n = 18) had been in a relationship for less than 6 months, 33% (n = 29) had been in a relationship between 6 and 20 months, and 46% (n = 40) had been in a relationship for more than 20 months. The participants were from a range of cultural and ethnic backgrounds, including European American (n = 102, 70 %), Asian American (n = 13, 9%), African American (n = 11, 8%), Hispanic (n = 9, 6%), other ethnicities (n = 6, 4%), and 3% (n = 4) did not report their race/ethnicity.

Participants were recruited through classroom announcements. The e-mail address of the investigator was provided in the flyers that were distributed in classrooms. Interested participants contacted the investigator for answers to their questions and to arrange a time for participating in the study. Before data collection, both partners in each couple were asked to sign consent forms, tailored to the student participant or their partner. After participants signed the consent forms, they completed a battery of questionnaires that covered demographic information, gender role egalitarianism, dominance/control, sexism, power dynamics, and aggression. Completing the questionnaires took from 60 to 90 minutes. Participants received extra class credit for their participation.

Measures

Demographic Information

This questionnaire included questions about demographic characteristics of the participants and their relationships. Questions on participants’ characteristics included age, gender, race, education level, and SES. The remainder of the questions were related to relationship characteristics of the participants, including duration of the relationship and anticipated length of the relationship.

Dominance Scale (DS)

The DS was used to measure three dimensions of dominance toward an intimate partner (Hamby, 1996). This scale includes 32 items rated on a 4-point Likert Scale, ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree (1=“Strongly Disagree,” 2=“Disagree,” 3=“Agree,” and 4=“Strongly Agree”). It has three subscales: (i) authority, (ii) restrictiveness, and (iii) disparagement. The DS includes items such as “Sometimes I have to remind my partner of who’s the boss,” “I have a right to know everything my partner does,” and “my partner does not know how to act in public.” According to the literature, reliability of the subscales ranges from .73 to .82. Initial construct validity of the scale is also satisfactory. In this study, Cronbach’s alpha was .90 for female participants and .88 for male participants alpha.

Sex Role Egalitarianism Scale (SRES)

The SRES assesses respondents’ attitudes toward the equality of men and women (Beere, King, Beere, & King, 1984). In this study, the SRES-Short Form was used. This shorter version of the SRES includes 25 attitudinal statements related to gender-based stereotyping. These statements require the respondent to evaluate judgments about men and women assuming non-traditional roles. The SRES has five subscales, each consisting of 5 items. These subscales measure attitudes related to (i) educational roles, (ii) employment roles, (iii) marital roles, (iv) parental roles, and (v) social-interpersonal-heterosexual roles. Items are rated on a 5-point Likert Scale ranging from “Strongly Disagree” to “Strongly Agree.” In the original study, Cronbach’s alpha for each scale ranged from .97 to .87. Test-retest reliability over a 4-week period was shown to be .85 over the domains (Beere, King, Beere, & King, 1984). Convergent and discriminant validity were established (Beere et al., 1984), and this scale has been widely used by various researchers (Crossman, Stith, & Bender, 1990). In this study, alpha for female participants was .86 and alpha for male participants was .92.

The Ambivalent Sexism Inventory (ASI)

The ASI is a 22-item measure that was developed to measure sexist attitudes (Glick & Fiske, 1996). The ASI has two (hostile & benevolent sexism) 11-item subscales. The hostile sexism subscale contains items such as “Women are too easily offended,” and the benevolent sexism subscale contains items such as “No matter how accomplished he is, a man is not truly complete as a person unless he has the love of a woman.” These subscales were reported to have reliability between .80 and .94 (Glick & Fiske, 1996). Past research also established concurrent validity with several other sexism scales (e.g. Attitudes toward Women Scale, the Modern Sexism Scale, and the Old Fashioned Sexism Recognition of Discrimination Scale) (Glick et al., 2000). In this study, alpha for female participants was .79 and alpha for male participants was .78.

Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS)

The CTS was developed by Straus (1979). It is widely used in the assessment of adult partner and self violence. CTS also assesses the significance of inter-partner agreement. A modified version of the Conflict Tactics Scale, the CTS2, was used in this study (Straus, Hamby, Boney-McCoy, & Sugarman, 1996). CTS2 has 78 items. In this study, the psychological aggression subscale, which has eight items, and the physical assault subscale, which has 12 items, were used. In each subscale, a list of actions is provided and participants are asked to circle how many times they and/or their partners engaged into each action. The psychological aggression subscale includes items such as “I insulted or swore at my partner” and “I stomped out of the room or house.” The physical aggression subscale includes items such as “I threw something at my partner” and “I pushed, grabbed, or hit my partner.” For each item in the scale, the statements are also posed by replacing the subject with “my partner.” For CTS2, reliability ranges from .62 to .88 for the verbal aggression subscale and from .79 to .88 for the physical aggression subscale. It is a widely-used instrument with good construct validity (Archer, 1999; Straus, 1995). In the current study, Cronbach’s alpha for female participants’ reports of their partners’ conflict tactics was .80 for psychological aggression and .77 for physical assault. Cronbach’s alpha for male participants’ reports of their partners’ conflict tactics was .70 for psychological aggression and .79 for physical assault. In order to compose the violence variables, for each action, self report on the frequency of being a victim of that action and partner report on the frequency of perpetrating that action were averaged.

Software

Full-information maximum likelihood estimation (FIML) was used in AMOS 17, a Structural Equation Modeling software solution developed by SPSS. It uses all available data for parameter estimation under the assumption that data are missing at random.

Results

Variables included in the analysis were examined to assess the accuracy and completeness of the data. In order to ensure that the variables were normally distributed, Shapiro-Wilk test for normality was performed. Results indicated that for females and males, physical assault frequency and psychological aggression variables had a slight positively skewed distribution with unsatisfactory normality. (As discussed in the previous section, these variables measure the aggression toward self for each participant, computed by averaging the self and partner reports on the frequency of each action.) In order to avoid violating the normality assumptions, these variables were transformed by taking the natural logarithm of the variables.

Means, standard deviations, and corresponding group t-tests for gender differences in dominance, egalitarianism, sexism, and violence variables are shown in Table 1. Preliminary paired sample t-test analysis indicated no sex difference for dominance, sexism, psychological aggression, and physical assault. Examination of relationship aggression variables demonstrated that females reported significantly higher levels of egalitarianism (t (53) = 2.424, p < .05), while males demonstrated significantly higher levels of hostile sexism (t (53) = −2.489, p < .05), need for authority (t (54) = −2.495, p < .05), and higher frequency of physical aggression (t (53) = 2.424, p < .05).

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics and Paired Sample T-Tests for the Major Variables

| Female | Male | T-test | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | S.D | Mean | S.D | T | Df | |

| Sexist Attitude: | ||||||

| Benevolent sexism | 2.84 | .43 | 2.90 | .57 | −.772 | 52 |

| Hostile sexism | 2.68 | .57 | 2.90 | .53 | −2.489* | 53 |

| Egalitarian attitude | 4.20 | .72 | 3.94 | .76 | 2.424* | 53 |

| Dominance: | ||||||

| Authority | 1.46 | .36 | 1.66 | .54 | −2.495* | 54 |

| Restrictiveness | 2.48 | .46 | 2.36 | .50 | 1.420 | 56 |

| Disparagement | 1.89 | .56 | 2.00 | .55 | −1.251 | 55 |

| Relationship Aggression: | ||||||

| Psychological Aggression | 8.83 | 8.57 | .33 | 8.62 | −.283 | 51 |

| Physical Assault | 1.50 | 2.84 | 3.27 | 7.35 | −2.016* | 51 |

p<.05

p<.01

Statistical Analysis - Actor Partner Interdependence Model (APIM)

Relationship research presents unique challenges, particularly when the unit of analysis is dyadic data rather than independent individual data. Novel measurement difficulties arise for analysis because relational partner data are likely to be correlated rather than being independent. Traditional statistical methods such as ANOVA and regression analysis have important limitations when used to analyze non-independent data, since they are generally based on the assumption of independence. Serious biases in estimation of standard error arise when this assumption is violated (Kenny, Kashy, & Cook, 2006).

A number of methods have been proposed for dealing with couple or family level data, including combining the data by taking averages or sums of husband and wife scores on outcome variables (e.g. Fisher, Kokes, Ranson, Phillips, & Rudd, 1985). However, such methods are likely to result inloss of information for the dyad. In particular, with such an approach, couples in which one partner has a low score while the other has a high score cannot be distinguished from couples in which both partners have medium scores. However, most clinicians would argue that such couples should be distinguished. On the other hand, running separate analyses on husband and wife data ignores the fact that husband and wife scores are related and therefore potentially correlated. Such an approach can result in too relaxed or too conservative significance tests (Kenny et al., 2006). Consequently, the statistical validity of conclusions derived from such analyses will be questionable.

In order to handle the difficulties associated with dyadic data analysis, we have chosen to use the Actor-Partner Interdependence Model (APIM) to examine the relationship between male and female scores on the dominance, sexism, and violence scales. APIM is a flexible method that allows analysis of interactions that can be broken into actor and partner effects (Cook, & Kenny, 2005). In this model, the dyad is treated as the unit of analysis. Actor effects are the relationships of individual’s independent variables on the individual’s own dependent variable. Partner effects are the relationships of the individual’s independent variables on their partner’s dependent variable.

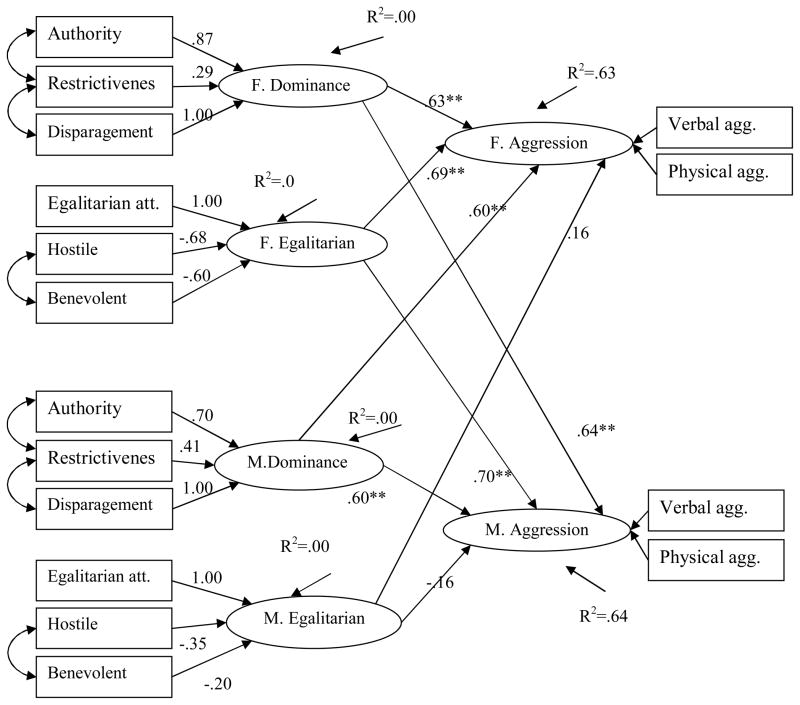

Findings indicated that the proposed model provided a good fit to the data (χ2(86, N=87) =137.22, p < .001) in that the ratio of χ2 statistics to the df was 1.60 (Singer & Willet, 2003; Wheaton, Muthen, Alwin, & Summers, 1977). The model provided a satisfactory fit to the data (RMSEA=.08, AGFI=.92, CFI=.93, NFI =.93). Examination of the structural path parameters (Figure 1) showed significant actor effects: the female egalitarian attitude factor had a significant direct effect on female victimization (β = 69, p < .05), as did female dominance (β =.63, p < .05). In other words, results indicated that women who scored high in egalitarian attitude and high in dominance reported being a victim of relationship aggression more often as compared to women who had low egalitarian attitudes and dominance. Male dominance had a significant direct effect on male victimization (β = .60, p < .05). Similarly, men who scored higher score in dominance were more likely to report being victim of relationship aggression.

Figure 1.

Fitted model with standardized coefficients. *p<.05, **p< .01, ***p<.001.

Examination of the structural path parameters showed significant partner effects, in that female egalitarian attitude had a significant direct effect on male victimization (β = .70 p < .05), as did female dominance on male victimization (β =.64, p < .05). In other words, women’s own high egalitarian attitude and high dominance score were associated with higher victimization of men. Furthermore, male dominance had a significant direct effect on female victimization (β = .60, p < .05). Men who scored higher on dominance also reported being more likely to be aggressive toward their partner. However, male egalitarian attitude did not have any significant partner or actor effects. When all else was controlled in the model, males’ aggression to their partner was not linked to their own egalitarian attitude,

Discussion

Previous studies reported inconsistent findings on the relationship between intimate partner violence and patriarchy, dominance, and power advantages (Dutton & Nicholls, 2005). The aim of this study was to extend our understanding of intimate partner aggression by investigating the relationship between egalitarian attitudes, dominance, and intimate relationship aggression for couples who are currently in a relationship. In our dyadic analysis, dominance exhibited more explanatory power than egalitarian attitudes when all else was controlled in the model. This was observed for the actor and partner effects of both males and females. Consistent with some other studies conducted across the United States, cultural pointers of patriarchy were not associated with male-to-female violence (Yllo & Straus, 1990).

Clearly, not all acts of violence occur in the same way. For example, Fogany (1999) identified dominance as a social privilege given to men, which promotes violence toward women. On the other hand, according to ethological theory, aggression and violence are triggered instinctively to maintain social order. It is likely that there are multiple pathways to becoming aggressive in a relationship. In some of these aggression patterns, similar to what Dutton and Nicholls (2005) reported and our analysis supported, relationship violence might be generated by psychopathology as well as the need for control—rather than gender roles.

Furthermore, contrary to our expectation, male egalitarian attitude showed no significant actor or partner effect on relationship aggression, while female egalitarian attitude had significant actor and partner effects on relationship aggression. More specifically, women who had high egalitarian values and low hostile and benevolent sexist values were more likely to report being a victim of relationship aggression. For such couples, it is possible that male partners perpetrate aggression as a means of reasserting control. Based on previous findings suggesting that men are particularly sensitive to the feeling of being controlled by their partners (Ehrensaft & Vivian,1999), it can be asserted that men might be interpreting their partner’s high level of egalitarian attitude as controlling toward themselves, which, in turn, might lead to aggression. Along these lines, physically abused wives reported that their husband often became violent when they were defensive toward their husband (Babcock et al., 2000). Additional research is needed to understand males’ interpretation of females’ egalitarian attitudes in the manifestation of relationship aggression.

It should also be noted that an important aim of this study was to examine the path to intimate relationship aggression within the context of dyadic interaction. As discussed above, our findings indicated that although male perpetration is not associated with their own egalitarian attitude, it is possible that this link is operant within the relational context. In other words, gender dynamics, particularly through female egalitarianism, might still have an impact on relationship aggression. Since violence research typically utilizes reports from either victims or perpetrators, this link cannot be examined in such studies. Therefore, egalitarianism should be further explored at the relationship level, by incorporating dyadic data collected from both partners.

Some previous studies indicated that females could be as abusive as males (Stets & Straus, 1992). Although the first wave of relationship aggression research was mainly based on male to female violence, others have focused on female to male relationship aggression as well (Archer, 2000; Capaldi, Kim, & Shortt, 2007). In concordance with this trend, our model accounted for approximately the same amount of variance for male and female aggression. In particular, it was found that women who had high egalitarian values and low hostile and benevolent sexist values were more likely to be aggressive toward their male partners. However, for males, egalitarian and sexist attitudes were not significantly associated with aggression toward their female partners or their likelihood of being abused by their female partners.

According to Johnson (1995), less severe violence is mostly related to commonly occurring couple conflict and mutual physical aggression between partners. On the other hand, more severe forms of violence that lead to injury as reported by women in domestic violence shelters are predominantly one-sided, male-to-female violence. Accumulative evidence also suggests that mutual couple violence is less severe and more common than severe male to female violence (e.g., intimate partner terrorism) (Capaldi, Shortt, & Crosby, 2003; Cascardi, Langhinrichsen, & Vivian, 1992). Since the current study focused on less severe forms of violence, our results were consistent with recent literature in this regard.

This study concentrated on dyadic patterns of relationship violence in understanding the interactions in which violent behaviors emerge. Couples participated in the study together, offering an opportunity to improve our understanding of the path to violence at the individual, as well as at the couple level. Since the proposed model was dyadic and included several predictors, we were able to identify the gender differences in terms of the experience of violence, as well as the adequacy of the model (and the factors considered thereof). In particular, dyadic analysis revealed that having egalitarian attitudes had different influences on males and females who were in the relationship together.

It should be recognized that data collected from college students allows only limited generalization. Married couples or couples who are older likely have different relationship dynamics. Therefore, it is important to extend this study with a broader range of participants in terms of age, race, and socio-economic status. The small sample size is another limitation that makes it difficult to generalize the findings of the study to a larger population. It is also possible that men are less likely than women to identify physical and sexual abuse perpetrated on themselves (Nabors, Dietz, & Jasinski, 2006). Furthermore, males were found to have a tendency to report aggression in their relationships only if they had been sexually abused as children (Prospero & Vohra-Gupta, 2007). These factors might also play a role in the gender differences observed in this study.

Findings of the current study may be applicable in clinical settings for therapists helping couples and families experiencing intimate partner violence. In particular, findings of this study indicate that violent couples might have different relationship dynamics. Therefore, couple therapy may be an option for some couples. However, couple therapy should be offered only after careful assessment and with much attention to the safety of the participants. Therapists may want to consider models that concentrate on promoting positive attitudes toward an egalitarian relationship in terms of power differences and establishing concordance in the egalitarian attitudes of the partners. In particular, if the egalitarian attitudes of women are perceived as controlling by their partners, therapists can identify this issue and focus on improving communication between the partners. Diminishing the need for dominance in the relationship could also be beneficial in treatment outcomes. Exploring the reasons where the need for dominance comes from and how it is manifested in the context of the relationship may also be helpful in reducing violence.

Since the intimate partner violence can affect health in many ways, both physically and emotionally, the findings are also applicable to those working in the health sector, particularly in primary and emergency care settings where many of these families first seek care. Many physicians might have difficulty broaching the topic of abuse with patient; this might be due to lack of time, resources, and training, fear of offending the patient, frustration with lack of change in patient’s situation, or financially draining long consultations (Snug & Inui, 1992). Physicians might use motivational interviewing techniques that are time-appropriate to help their patients explore their readiness to change the situation and their ideas about egalitarianism, sexism, and violence.

Relationship aggression is an important social problem, and it is extensive throughout the world. There is more to be done to give the public a more effective and nuanced understanding of its predictors, consequences, and treatments. This study provides further understanding of intimate relationship violence by showing that for both genders, a need for dominance is a crucial factor in the manifestation of relationship aggression and that having egalitarian attitudes has a different effect on both males’ and females’ experiences of violence.

Footnotes

In order to utilize the dyadic data, Actor-Partner Interdependence Model (APIM) was used to test the proposed model. The proposed model provided a good fit to the data (χ2(86, N=87) =137.22, p < .001) in that the ratio of χ2 statistics to the df was 1.60 with model characteristics of RMSEA=.08, AGFI=.92, CFI=.93, NFI =.93.

Contributor Information

Gunnur Karakurt, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH.

Tamra Cumbie, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, TX

References

- Archer J. Assessment of the reliability of the conflict tactics scales: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1999;14:1263–1289. [Google Scholar]

- Archer J. Sex difference in aggression between heterosexual partners: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin. 2000;126:651–680. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.5.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babcock JC, Jacobson NS, Gottman JM, Yerington TP. Attachment, emotional regulation, and the function of marital violence: Differences between secure, preoccupied, and dismissing violent and nonviolent husbands. Journal of Family Violence. 2000;15:391–409. [Google Scholar]

- Beere CA, King DW, Beere DB, King LA. The Sex-Role Egalitarianism Scale: A measure of attitudes toward equality between the sexes. Sex Roles. 1984;10:563–576. [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi D, Kim HK, Shortt J. Observed initiation and reciprocity of physical aggression in young, at-risk couples. Journal of Family Violence. 2007;22:01–111. doi: 10.1007/s10896-007-9067-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi D, Shortt J, Crosby L. Physical and psychological aggression in at-risk young couples: Stability and change in young adulthood. Merill-Palmer Quarterly. 2003;49:1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Cascardi M, Langhinrichsen J, Vivian D. Marital aggression, impact, injury, and health correlates for husbands and wives. Archives of Internal Medicine. 1992;152:1178–1184. doi: 10.1001/archinte.152.6.1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cate CA, Henton JM, Koval J, Christopher FS, Lloyd S. Premarital abuse: A social psychological perspective. Journal of Family Issues. 1982;3:79–90. [Google Scholar]

- Choi SYP, Ting K. Wife beating in South Africa: An imbalance theory of resources and power. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2008;23:834–852. doi: 10.1177/0886260507313951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook WL, Kenny DA. The Actor-Partner Interdependence Model: A model of bidirectional effects in developmental studies. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2005;29:101–109. [Google Scholar]

- Crossman RK, Stith SM, Bender MM. Sex role egalitarianism and marital violence. Sex Roles. 1990;22:293–304. [Google Scholar]

- Dutton MA, Green BL, Kaltman SI, Roesch DM, Zeffiro TA, Krause ED. Intimate partner violence, PTSD and adverse health outcomes. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2006;21:955–968. doi: 10.1177/0886260506289178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutton DG, Nicholls TL. The gender paradigm in domestic violence research and theory: The conflict of theory and data. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2005;10:680–714. [Google Scholar]

- Ehrensaft MK, Vivian D. Is partner aggression related to appraisals of coercive control by a partner? Journal of Family Violence. 1999;14:251–266. [Google Scholar]

- Ferraro KJ, Moe AM. Mothering, crime and incarceration. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography. 2003;32:9–40. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher LA, Kokes RF, Ranson DC, Phillips SL, Rudd PA. Alternative strategies for creating “relational” family data. Family Process. 1985;24:213–224. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.1985.00213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonagy P. Male perpetrators of violence against women: An attachment theory perspective. Journal of Applied Psychoanalytic Studies. 1999;1:7–27. [Google Scholar]

- Fox GL, Benson ML, DeMaris A, Van Wyk J. Economic distress and intimate violence: Testing family stress and resources theories. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2002;64:793–807. [Google Scholar]

- Glick P, Fiske ST. The Ambivalent Sexism Inventory: Differentiating hostile and benevolent sexism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1996;70:491–512. [Google Scholar]

- Glick P, Fiske ST, Mladinic A, Saiz J, Abrams D, Masser B, et al. Beyond prejudice as simple antipathy: Hostile and benevolent sexism across cultures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;79:763–775. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.79.5.763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman LA, Koss MP, Fitzgerald L, Felipe-Russo N, Keita G. American Psychologist. 1993;48:1054–1058. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.48.10.1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gryl F, Stith S, Bird G. Close dating relationships among college students: Differences by use of violence and by gender. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1991;8:243–264. [Google Scholar]

- Hamby SL. The Dominance Scale: Preliminary psychometric properties. Violence and Victims. 1996;11:199–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffe PG, Suderman M. Child witnesses of woman abuse: Research and community responses. In: Stith SM, Straus MA, editors. Understanding partner violence. Minneapolis, MN: National Council on Family Relations; 1995. pp. 213–222. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MP. Patriarchal terrorism and common couple violence: Two forms of violence against women. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1995;57:283–294. [Google Scholar]

- Katz J, Arias I. Psychological abuse and depressive symptoms in dating women: Do differential types of abuse have differential effects? Journal of family Violence. 1999;14:281–195. [Google Scholar]

- Kenny D, Kashy D, Cook WL. Dyadic data analysis. New York: Guilford Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kruttschnitt C. Violence by and against women: A comparative and cross-national analysis. In: Ruback RB, Weiner NA, editors. Interpersonal violent behaviors. Social and cultural aspects. New York: Springer Publishing Company; 1995. pp. 89–108. [Google Scholar]

- Lawson DM. Attachment, interpersonal problems, and family of origin functioning: Differences between partner violent and non-partner violent men. Psychology of Men and Masculinity. 2008;9:90–105. [Google Scholar]

- Lemon SC, Verhoek-Oftedahl W, Donnelly EF. Preventive healthcare use, smoking, and alcohol use among Rhode Island women experiencing intimate partner violence. Journal of Women’s Health and Gender-Based Medicine. 2002;11(6):555–562. doi: 10.1089/152460902760277912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall LL. Effects of men’s subtle and overt psychological abuse on low income women. Violence and Victims. 1999;14:69–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nabors EL, Dietz TL, Jasinski JL. Domestic violence beliefs and perceptions among college students. Violence and Victims. 2006;21:779–794. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Próspero M, Vohra-Gupta S. Gender differences in the relationship between intimate partner violence victimization and the perception of dating situations among college students. Violence and Victims. 2007;22(4):489–502. doi: 10.1891/088667007781553928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagrestano LM, Heavey CL, Christensen A. Perceived power and physical violence in marital conflict. Journal of Social Issues. 1999;55(1):65–79. [Google Scholar]

- Singer JD, Willett JB. Applied longitudinal data analysis: Modeling change and event occurrence. New York: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Smith MD. Patriarchal ideology and wife beating: A test of a feminist hypothesis. Violence and Victims. 1990;5:257–273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugg N, Inui T. Primary care physician’s response to domestic violence. Journal of American Medical Association. 1992;267:3157–3160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stets JE. Verbal and psychological aggression in marriage. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1990;38:15–28. [Google Scholar]

- Stets JE, Straus MA. The marriage licence as a hitting licence: A comparison of assaults in dating, cohabiting and married couples. In: Straus MA, Gelles RJ, editors. Physical violence in American violence. New Brunswick. NJ: Transaction; 1990. pp. 227–244. [Google Scholar]

- Stets J, Straus M. Physical violence in American families. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers; 1992. The marriage license as a hitting license; pp. 227–244. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA. Measuring intrafamily conflict and violence: The Conflict Tactics (CT) Scales. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1979;41:75–88. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA. Manual for the Conflict Tactic Scales. Durham: University of New Hampshire, Family Research Laboratory; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Straus SM. Dominance and symmetry in partner violence by male and female university students in 32 nations. Children and Youth Services Review. 2008;30:252–275. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby SL, Boney-McCoy S, Sugarman DB. The revised conflict tactics scales (CTSZ) Journal of Family Issues. 1996;17:283–316. [Google Scholar]

- Tolman RM. The validation of the psychological maltreatment of women inventory. Violence and Victims. 1999;14:25–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waltz J, Babcock JC, Jacobson NS, Gottman JM. Testing a typology of batterers. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:658–669. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheaton B, Muthen B, Alwin DF, Summers GF. Assessing reliability and stability in panel models. In: Heise DR, editor. Sociological methodology. San Francisco: Jossey Bass; 1977. pp. 84–136. [Google Scholar]

- Yllo K, Straus MA. Patriarchy and violence against wives: The impact of structural and normative factors. In: Straus MA, Gelles RJ, editors. Physical violence in American families: Risk factors for adaptations to violence in 8 145 families. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction; 1990. pp. 383–399. [Google Scholar]

- Yount KM. Resources, family organization, and domestic violence against married women in Minya, Egypt. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2005;67:579–596. [Google Scholar]