Abstract

Objective

To identify factors that might influence physicians' referrals of obese adolescents to pediatric multidisciplinary weight management (PMWM) programs.

Design/methods

Survey of a national sample of 375 pediatricians (PDs) and 375 family physicians (FPs) explored program availability, referral history, desired services, and when in the course of treatment physicians would refer. Differences were examined via c2 tests.

Results

Response rate was 67%. More PDs than FPs reported having a PMWM program available (46% vs 10%, P < .01). More PDs (PD 83% vs FP 53%, P < .01) and female physicians (88% vs 65%, P < .01) reported having made a referral. Most physicians wanted coordinated diet, activity, and behavioral therapy (79%). Almost all physicians indicated they would refer when unsure of what else to do, or if requested by the patient/parent.

Conclusions

PMWM program referrals appear limited by availability. These data also suggest physicians may be reticent to refer. Further work should examine whether this affects patient outcomes.

Keywords: obesity, adolescents, primary care physicians, multidisciplinary care, weight management programs

Introduction

Over the past 3 decades the prevalence of obesity among children and adolescents has more than tripled.1–5 The challenges faced by physicians in attempting to treat pediatric obesity in the primary care setting are well documented.6,7 Low self-efficacy, time constraints, and limited resources are often cited barriers to effectively treating obesity in the primary care setting.8,9 Consequently, recent efforts to treat childhood obesity have focused on the development of pediatric multidisciplinary weight management (PMWM) programs, where coordinated, intensive weight-management services can be provided.

In these programs, physicians work in tandem with dietitians, exercise physiologists, and psychologists to provide comprehensive weight management.10 Such programs generally provide medical care and weightrelated educational components enhanced by behavior modification techniques. Few of these programs have published outcomes data but those that do have shown modest success in reducing participants' body mass index (BMI).11,12

Typically, referrals to PMWM programs are made by primary care physicians, but little is known about the referral decisions of pediatricians and family physicians in this area. Our objective was to explore whether primary care physicians had PMWM programs available to which they could refer patients, what services they want their patients to receive from a pediatric PMWM program, and when in the course of treating an obese adolescent they would make a referral to a PMWM program. In addition, we wished to examine whether these factors varied by specialty and by other physician demographics.

Methods

Sample

A national random sample of 375 pediatricians (PDs) and 375 family physicians (FPs) was drawn from the American Medical Association (AMA) Masterfile, a database of all licensed physicians in the United States. The AMA Masterfile is the most comprehensive listing of physicians in the United States, including both AMA members and nonmembers. The sampling frame included all allopathic and osteopathic physicians self-described as a general pediatrician or family physician in office-based direct patient care. Excluded were physicians with any specialty board listing, physicians 70 years or older, and resident physicians. Along with names and office addresses, the AMA Masterfile also includes demographic information such as gender, year of medical school graduation, and history of board certification.

Instrument

The investigators developed a self-administered, 2-page, 30-item survey instrument with fixed responses. Respondents were asked the following questions: (a) Is there a pediatric multidisciplinary weight management program available to which you can refer patients? (Yes, No, Don't know); and (b) If yes, have you ever referred adolescents to this program? (Yes, No). Respondents were subsequently asked to assume that a pediatric multidisciplinary weight management center were available to them, then to note whether they would not refer, may refer, or would refer an obese adolescent in the following situations: (a) on first diagnosing a patient as obese, (b) after management in the primary care setting for ≥6 months, (c) after participation in a group program (eg, Weight Watchers), (d) if the patient has been obese for more than 2 to 3 years, (e) at any point if requested by the patient or parent, and (f) when you don't know what else to do to help your patient lose weight.

Finally, respondents were asked to indicate the extent (very little, somewhat, or a lot) the need for the listed services would influence them to make a referral to a PMWM program. The survey instrument was pilot tested with a convenience sample of physicians to ensure clarity and ease of administration. Feedback from the pilot test was used to guide refinements to the instrument.

Survey Administration

During spring 2007 the survey along with a cover letter explaining the purpose of the study were mailed to the full sample. Two subsequent mailings were sent to nonrespondents at 3-week intervals.

Data Analysis

After verification of data entry, univariate frequencies were generated for each variable. Bivariate analyses using a likelihood ratio c2 test were performed to examine differences in availability, referral patterns, and desired services. Associations were also explored by years since medical school graduation (≤10 years, 11 to 20 years, and >20 years), gender, and board certification status. All analyses were conducted using STATA 8.0 (Stata Corporation; College Station, TX). This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Michigan Medical School.

Results

The overall response rate was 67% (PDs, 76%; FPs 58%). There were no significant differences between the nonrespondents and the eligible respondents based on demographic characteristics from the AMA Masterfile. The characteristics of this nationally representative sample are presented in Table 1. PDs and FPs did not differ significantly in years since graduation or percentage with board certification. A higher percentage of PDs than FPs were female.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of the Respondents by Specialty

| Pediatricians (%) | Family Physicians (%) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Male | 43 | 63 | |

| Female | 57 | 37 | <.01 |

| Years since graduation | |||

| ≤10 | 22 | 23 | |

| 11–20 | 39 | 33 | |

| >20 | 39 | 34 | Nonsignificant |

| Board certification | |||

| Yes | 88 | 85 | |

| No | 12 | 15 | Nonsignificant |

Overall, 30% of physicians indicated that there was a PMWM program available to which they could refer patients. However, there were significant differences in reported availability of a pediatric weight management program between PDs (46%) and FPs (10%; Table 2). Approximately one quarter of family physicians did not know whether there was a PMWM program available to them. Of those physicians who reported having a PMWM program available, more than three quarters had actually referred a patient (77%). Having made a referral differed significantly by specialty (PD 83% vs FP 53%, P < .001) and by gender (female 88% vs male 65%, P < .001) but not by years since graduation or history of board certification.

Table 2.

Availability of Pediatric Multidisciplinary Weight Management (PMWM) Programs by Specialty

| Pediatricians (%) | Family Physicians (%) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Available PMWM program | 46 | 10 | <.001 |

| No available PMWM program | 43 | 66 | |

| Don't know about availability | 11 | 24 |

Of the 4 factors listed as possible reasons for referring an adolescent to a PMWM program, “coordinated diet, activity, and behavioral therapy” (80%) and “family-focused weight management therapy” (77%), were the most frequently endorsed as motivating physicians a lot to refer patients. The desire to obtain coordinated medical management of obesity-related comorbidities and for coordinated obesity-related medical evaluation acrossw subspecialties were only endorsed by about half of the respondents as providing a lot of motivation for them to refer to a PMWM program (53% and 47%, respectively). The bivariate analyses did not reveal any consistent patterns of associations between reasons for referring and physician specialty, gender, years since medical school graduation, and history of board certification.

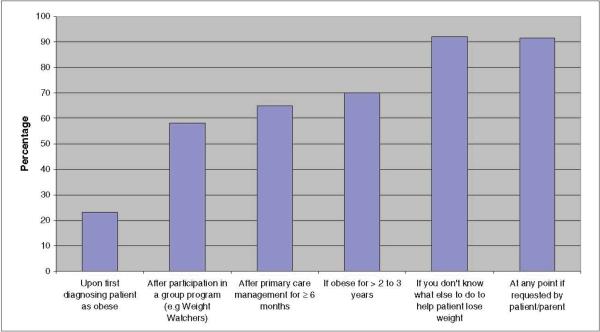

With regard to when physicians thought they would refer an obese adolescent to a PMWM program, most respondents indicated they would make a referral “at any stage, if requested by the patient or their parent” (91%) and “when they didn't know what else to do to help the adolescent lose weight” (92%; Figure 1). Referral “after 6 months of treatment in the primary care setting” and “after trying a group weight management program such as Weight Watchers” was significantly more common among recent graduates (<10 years) compared with their counterparts who graduated >20 years ago. In general, female compared with male physicians more often indicated that they would refer adolescents “after 6 months of treatment in the primary care setting” (66% vs 50%, respectively, P < .01), and “if the patient had been obese for more than 2 to 3 years” (80% vs 61%, respectively, P < .001).

Figure 1.

Percentage of physicians who would refer obese adolescents to a pediatric multidisciplinary weight management program at specific thresholds

Discussion

In this national survey of PDs and FPs, we found that less than half of the respondents knew of a PMWM program available to which they could refer patients. Although much more research is needed to determine the best approach to the treatment of obesity, the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American Medical Association recently recommended the use of a multidisciplinary approach for the treatment of obesity when primary care efforts have failed to achieve satisfactory results.13 If our results reflect the true availability of PMWM programs, then it may be difficult for physicians to follow the recommendations for referral and further work is required to explore this as a potential barrier to obesity care.

Pediatricians were more likely than family physicians to know whether there was a PMWM program available to which they could refer patients and if they knew of one, they were more likely to have made a referral. The reasons for these differences are not known. It is likely that PDs are more aware of the resources available for children as this is their focus but further work is required to explore the discrepancy in referrals. It is possible that PDs and FPs differ in their self-efficacy in the treatment of pediatric obesity or in their views of the importance of intervening in the childhood years.

In an effort to help physicians treat childhood obesity, a number of state and national agencies have developed treatment aids and/or toolkits for use in the primary care setting.14–16 Whether these will increase PDs' and FPs' ability to manage obesity in the office is as yet unknown. However, some of the barriers to care such as the time required during a busy day to counsel about obesity, will be largely unaffected by these aids. Thus, the need for referrals to a PMWM remains, along with the need for assistance and guidance regarding options for referrals (eg, registries of locally available programs) and the optimal stage in treatment to make such a referral.

From this study it appears that primary care physicians value family-focused interventions and coordinated diet, activity, and behavioral therapy for their patients requiring obesity treatment. These are aspects of weight management that are difficult to deliver in the primary care setting and to meet these needs, a number of PMWM programs have recently been developed across the country.17 Unfortunately, these services are typically inadequately reimbursed or not reimbursed at all.18,19 Whether these economic considerations play a role in primary care physicians' referral patterns to PMWM programs was not explored. However, if this is the case, poor reimbursement may result in PMWM programs being underused even when they are available.

Limitations

The response rate was 67%. The views of PDs and FPs in general may vary from our findings. In addition, we asked about physicians' opinions; actual practice may differ.

Conclusions

Access to PMWM programs for obese adolescents appears limited by both availability and a tendency for physicians to delay referrals. Initiatives to improve obesity treatment should include efforts to explore and affect physicians' referral patterns.

Acknowledgments

Funding The author(s) received no financial support for the research and/or authorship of this article.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Ogden CL, Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Johnson CL. Prevalence and trends in overweight among US children and adolescents, 1999–2000. JAMA. 2002;288:1728–1732. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.14.1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, McDowell MA, Tabak CJ, Flegal KM. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in the United States, 1999–2004. JAMA. 2006;295:1549–1555. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.13.1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Strauss RS, Pollack HA. Epidemic increase in childhood overweight, 1986–1998. JAMA. 2001;286:2845–2848. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.22.2845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Troiano RP, Flegal KM. Overweight children and adolescents: description, epidemiology, and demographics. Pediatrics. 1998;101(3 Pt 2):497–504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hedley AA, Ogden CL, Johnson CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, Flegal KM. Prevalence of overweight and obesity among US children, adolescents, and adults, 1999–2002. JAMA. 2004;291:2847–2850. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.23.2847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dorsey KB, Wells CW, Krumholz HM, Concato JC. Diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of childhood obesity in pediatric practice. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159:632–638. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.7.632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Story MT, Neumark-Stzainer DR, Sherwood NE, et al. Management of child and adolescent obesity: attitudes, barriers, skills, and training needs among health care professionals. Pediatrics. 2002;110:210–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Perrin EM, Flower KB, Ammerman AS. Body mass index charts: useful yet underused. J Pediatr. 2004;144:455–460. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.01.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Woolford SJ, Clark SJ, Strecher VJ, Gebremariam A, Davis MM. Physicians' perspectives on increasing the use of BMI charts for young children. Clin Pediatr. 2008;47:573–577. doi: 10.1177/0009922808314905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eneli I, Woolford SJ. The pediatric multidisciplinary obesity program: an update. Prog Pediatr Cardiol. 2008;25:129–136. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kirk S, Zeller M, Claytor R, Santangelo M, Khoury PR, Daniels SR. The relationship of health outcomes to improvement in BMI in children and adolescents. Obes Res. 2005;13:876–882. doi: 10.1038/oby.2005.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Savoye M, Shaw M, Dziura J, et al. Effects of a weight management program on body composition and metabolic parameters in overweight children: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2007;297:2697–2704. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.24.2697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barlow SE. Expert committee recommendations regarding the prevention, assessment, and treatment of child and adolescent overweight and obesity: summary report. Pediatrics. 2007;120(Suppl 4):S164–S192. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2329C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. [Accessed July 31, 2009];Blue Cross Blue Shield of Tennessee tool kit. Web site. http://www.bcbst.com/providers/Childhood_obesity_tool _kit.pdf.

- 15.National Initiative for Children's Healthcare Quality (NICHQ) [Accessed July 31, 2009]; Web site. http://www.nichq.org/childhood_obesity/childhood_obesity_toolkit.html.

- 16.Capital District Physicians' Health Plan [Accessed July 31, 2009]; Web site. http://www.cdphp.com/images/providers/Toolkit_BMI_Provider.pdf.

- 17.Eneli I, Patel D, Cunningham A, Hinton T, Stephens J, Murray R. Pediatric obesity programs in US children's hospitals. Paper presented at: Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting; Honolulu, HI. May, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tershakovec AM, Watson MH, Wenner WJ, Jr, Marx AL. Insurance reimbursement for the treatment of obesity in children. J Pediatr. 1999;134:573–578. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(99)70243-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Griffith J, Gantz S, Lowry J, Dai H, Bada H. Insurance reimbursement in a university-based pediatric weight management clinic. J Natl Med Assoc. 2007;99:1037–1041. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]