Abstract

Background

Peripheral T-cell lymphomas (PTCLs) have an inferior progression-free (PFS) and overall survival (OS) compared to aggressive B-NHL. Since PTCLs over-express MDR-1/P-gp, we devised PEGS with agents which are not substrates of the efflux pump. Gemcitabine was included due to excellent single agent activity in PTCL.

Patients and Methods

PTCLs with stage II bulky, III or IV with extra-nodal, nodal and transformed cutaneous presentations were eligible. Patients received IV cisplatin 25 mg/m2 days 1–4, etoposide 40 mg/m2 days 1–4, gemcitabine 1000 mg/m2 day 1 and solumedrol 250 mg days 1–4 of a 21 day cycle for 6 cycles.

Results

34 patients were enrolled, 33 were eligible and 79% were newly diagnosed. Histologic types were PTCL, NOS [n= 15], ALCL, ALK- [n= 4], AITL [n= 6] or other T-NHL [n=8]. Adverse events included 1 grade 5 infection with grade 3–4 ANC and 9 grade 4 hematologic toxicities. The overall response rate [ORR] was 39%: 47% in PTCL, NOS, 33% in AITL, 25% in ALCL [ALK-], and 38% in other T-NHL. PFS at 2 years was 12% [95% CI: 0.1–31%] with a median PFS of 7 months. OS at 2 years was 30% (95% CI: 8–54%) with a median OS of 17 months. P-gp expression by immunohistochemistry showed strong positivity in a subset of lymphoma cells [n=6] and tumor endothelium [n=25].

Conclusions

Overall PEGS was well tolerated, but OS was not considered promising given design specified targets. These results may serve as a benchmark for future comparisons for non-CHOP regimens.

Keywords: Peripheral T-cell lymphoma; not otherwise specified (PTCL, NOS); Anaplastic large cell lymphoma; Anaplastic Lymphoma Kinase-negative (ALCL, ALK-); Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma (AITL); Chemotherapy; Multi-drug Resistant Proteins

Introduction

Non-cutaneous nodal and extra-nodal peripheral T-cell lymphomas (PTCL) are a rare heterogeneous group of clinically aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHL) with a poor prognosis [1]. The World Health Organization (WHO) classification includes many subtypes [2] but understanding the pathophysiology and development of clinically effective therapies for each entity is currently very difficult [3]. Among the subtypes of PTCL different outcomes are observed. The international prognostic index (T-IPI) applied to high risk (IPI 3–5) PTCL, NOS has a 5 year OS of 11%, AITL 25% and ALCL, ALK- 13–33% [4]. Frequently, patients with a diagnosis of PTCL are treated with anthracycline-based therapy (e.g. CHOP or CHOP-like), however, event-free and OS are inferior to those with aggressive B-cell NHL [5, 6]. Relapse/refractory disease is common for most PTCL patients with current agents [7] with inadequate salvage therapy. Autologous stem cell transplants may be curable in a small subset of fit chemo-sensitive patients [8].

The optimal therapy for PTCL is an area of controversy due to the rarity of the disease subtypes, variable clinical course, biological heterogeneity and lack of clinical trials. Studies using the Lymphoma Biology Tissue Bank of SWOG, a federally funded cancer research cooperative group, have shown that patients with advanced stage PTCLs using standard IPI have worse survival than patients with B-cell lymphomas (p < .01), with a median PFS of 6 months (compared to 17 months for aggressive B-NHL) and a 2 year PFS of 21% (compared to 46% for B-NHL) [9]. The biologic explanation for the difference is unknown.

Several biomarkers of prognostic significance that predict for a poor survival in PTCL have been identified, including factors that drive aberrant proliferation (e.g. Ki-67 and p53) [7]. In fact, p53 is a critical prognostic factor that correlates well with MDR-1/P-gp expression (ABCB1, ATP-binding cassette sub-family B1) that confers chemotherapy resistance [10, 11]. However, the differential expression of P-gp within the tumor and the microenvironment has not been elucidated. Hence, we hypothesized that combination chemotherapy with agents not effluxed by MDR1 (ABCB1) may overwhelm P-gp and abrogate drug resistance leading to an increased response rate that would improve PFS and OS. Therefore, we devised a protocol based on ESHAP (cisplatin, etoposide, ara-C and solumedrol), a typical second-line chemotherapy regimen, by replacing ara-C with gemcitabine, known as `PEGS'. Gemcitabine was included in PEGS as it has potent single agent activity in PTCL [12] and is not a substrate of ABCB1. In 44 previously treated patients with mycosis fungoides (MF; n = 30) and peripheral T-cell lymphoma unspecified (PTCLU; n = 14), gemcitabine administered on days 1, 8, and 15 of a 28 day cycle (1,200 mg/m2) achieved 5 CRs and 26 PRs. The CR and PR rates were similar for MF and PTCLU, with a median duration of CR and PR of 15 and 10 months respectively [12].

Methods

Patient Population

The study was conducted by SWOG (S0350; Clinical Trials Registration Identification Number: NCT00109928) with appropriate regulatory and institutional review board approval for each site and patients providing informed consent. Patients must have either newly diagnosed NHL of T-cell lineage or relapsed or progressing disease after one prior treatment with a non-platinum based chemotherapy (e.g. CHOP or CHOP-like). ALCL ALK positive patients were excluded as they do better with CHOP-like therapy. All samples had central pathology review (Dr. C. Spier). PTCL includes extra-nodal types (extra-nodal NK/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type; enteropathy type T-cell lymphoma; hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma; and subcutaneous panniculitis like T-cell lymphoma) and nodal types (peripheral T-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified; anaplastic large cell lymphoma, ALK negative; and angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma). Patients with transformed cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) to peripheral T-cell lymphoma (PTCL) with systemic involvement (not local skin transformation) were also eligible. Patients had bulky Stage II, Stage III or Stage IV disease according to Ann Arbor classification [13]. All patients were required to have bi-dimensionally measurable disease documented within 28 days prior to registration. Patients with non-measureable disease in addition to measureable disease were required to have the non-measurable disease assessed within 42 days prior to registration. A bilateral or unilateral bone marrow aspirate and biopsy were required to be performed within 42 days prior to registration.

Patients were ≥18 years old. Women must have been of non-childbearing potential (post-menopausal or history of bilateral oophorectomy or hysterectomy), not pregnant, or willing to use contraception. Inclusion criteria included life expectancy ≥12 weeks; a performance status of 0, 1, or 2 by Zubrod criteria; ANC ≥ 1,500/mm3 and platelets ≥ 75,000/mm3; creatinine clearance ≥ 30 mL/min or estimated creatinine clearance ≥ 30 mL/min.; serum bilirubin ≤ 2 × institutional ULN; and ALT or AST or ALKP >2.5 ULN of reference range or >5 times ULN of reference range with liver metastases. No prior malignancy was allowed except for adequately treated basal cell (or squamous cell) skin cancer, in situ cervical cancer or other cancer for which the patient has been disease-free for five years. Exclusion criteria included >1 prior chemotherapy or radiotherapy within 4 weeks of study start; left ventricular ejection fraction < institutional lower limit of normal; history of ischemic heart disease or myocardial infarction within 3 months of the study; severe or uncontrolled systemic conditions or current unstable or uncompensated respiratory or cardiac conditions; central nervous system involvement by lymphoma; or HIV-positive.

Study Objectives

This was a Phase II study of PTCL patients treated with the regimen of cisplatin, etoposide, gemcitabine, and solumedrol (PEGS) with the primary objective of estimating 2 year OS. Secondary clinical objectives were to assess toxicity, response rate (complete unconfirmed, complete and partial responses), PFS, and P-glycoprotein (P-gp) expression in untreated and treated T-NHL.

Lesions were accurately measured in two dimensions by CT, MRI, medical photograph (skin or oral lesion), plain X-ray, or other conventional technique and a greatest transverse diameter of 1 cm or greater; or palpable lesions with both diameters ≥ 2 cm. CT scans were the standard imaging for evaluation of nodal disease. Responses (CR, PR, SD and PD) were evaluated according to modified Cheson criteria [14].

Drug Administration

Eligible patients received IV cisplatin 25 mg/m2 days 1–4, etoposide 40 mg/m2 days 1–4, gemcitabine 1000 mg/m2 day 1 and solumedrol 250 mg days 1–4 of a 21 day cycle for a maximum of 6 cycles. Dose reductions (up to 50%) and/or delays (up to 4 weeks) were allowed. Bone marrow colony stimulating factors were not be routinely used in this protocol. However, they could be utilized in individual patients if the presence of severe neutropenia required either delays in therapy or a dose reduction or with neutropenic fever.

P-glycoprotein Expression by immunohistochemistry

Thirty-three patients underwent histologic evaluation. Two were excluded from the P-gp analysis because there was insufficient tissue for study. All others were evaluated for P-gp using both JSB-1 (Covance, Dedham, MA) and C494 (Covance, Dedham, MA) murine monoclonal antibodies, which target that 170-kDa adenosine triphosphate (ATP)-dependent multi-specific drug transporter ABCB1 [15]. IHC staining was performed utilizing the Ventana Ultra automated stainer (Ventana Medical Systems, Tucson, AZ). Tissue sections were cut at 3 microns, with an initial antigen retrieval process performed on the Ultra. After antigen amplification, antibody detection was performed using the Ultra. After an H&E counterstain was performed, each slide was cover-slipped and evaluated. Evaluation included both tumor and residual background components. If the lymphoma was composed of large cells, determination of their P-gp status was certain. However, when tumor cells and residual small lymphocytes were of similar size, P-gp status of each group was not always able to be made with complete certainty.

Statistical Methods

The primary objective of this study was to estimate 2 year OS. Thirty patients accrued over 4 years with two additional years of follow-up would be sufficient to estimate the two year survival to within ± 0.18. Assuming a historical two year survival probability of 0.48 for advanced stage T-cell lymphomas, with 30 patients this would have 81% power (one- sided 0.03 level one-sample exact binomial test) to detect an improvement to a 2 year survival probability of 0.72 assuming complete follow-up on all patients for two years. An estimated 2 year survival probability of 0.67 would warrant further investigation of this regimen. Thirty patients would also be sufficient to estimate response, the probability of any particular adverse event, and PFS to within ± 18%. Any adverse event occurring with at least 8% probability is likely to be seen at least once (92% chance).

The following definitions applied to time-related endpoints. OS was defined as the time between study registration and death due to any cause. PFS was defined as the time between study registration and documented progression, or death if no progression was observed. Time to response (TTR) was defined as the time between study registration and first documentation of response (either first documentation of partial response; or, if no documentation of partial response, first documentation of confirmed or unconfirmed complete response). Duration of response (DR) was defined as the time between first documentation of response and progression, death, or date of last contact (if still alive without progression). Median and range values are provided for TTR. Median and 2-year estimates of PFS, OS, and DR, and their 95% confidence intervals (CI) were estimated using Kaplan-Meier to account for censoring [16].

Results

Patient Characteristics

Thirty-four patients were enrolled. One patient was ineligible due to insufficient pre-study documentation. Among the 33 eligible patients, T-NHL subtypes were PTCL, NOS [n=15], AITL [n=6], ALCL, ALK- [n=4], Nasal NK/T-NHL [n=2] and other T-NHLs [n=6] (n=1 subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma; n=1 enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma, Type II; and n=4 T-cell lymphomas with likely diagnoses of enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma [n=1], AITL [n=2], and ALCL (ALK-) [n=1]. Most diagnostic biopsies were from lymph nodes [19/33, 58%], while the rest originated from varied sites. The median age was 60 years (range, 20–92 years) with 22 (67%) males. The majority of the patients enrolled on S0350 were newly diagnosed and chemo-naïve (79%) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient Demographics

| Patient Characteristics | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| Median (range) | 60 (20–92) Yr | |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 22 | 67% |

| Female | 11 | 33% |

| Race | ||

| White | 28 | 85% |

| Black | 4 | 12% |

| Asian | 1 | 3% |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic | 2 | 6% |

| Not Hispanic | 31 | 94% |

| Number of Prior Treatments | ||

| 0 | 26 | 79% |

| 1 | 7 | 21% |

| Histology | ||

| PTCL [NOS] | 15 | 45% |

| AITL | 6 | 18% |

| ALCL [ALK-] | 4 | 12% |

| Nasal NK/T-NHL [Extranodal] | 2 | 6% |

| Other T-NHL | 6 | 18% |

| Symptoms | ||

| A | 16 | 48% |

| B | 17 | 52% |

| Bulky Disease | ||

| No | 25 | 76% |

| Yes | 8 | 24% |

| Stage | ||

| II | 5 | 15% |

| III | 9 | 27% |

| IV | 19 | 58% |

| Performance Status | ||

| 0 | 7 | 21% |

| 1 | 21 | 64% |

| 2 | 5 | 15% |

| Bone Marrow Involvement | ||

| No | 23 | 70% |

| Yes | 10 | 30% |

| LDH | ||

| Normal | 11 | 33% |

| >ULN | 22 | 67% |

| Extra-nodal Involvement | ||

| No | 11 | 33% |

| Yes | 22 | 61% |

| IPI Risk Group | ||

| Low | 6 | 18% |

| Low-Intermediate | 13 | 39% |

| High Intermediate | 8 | 24% |

| High | 6 | 18% |

Patient characteristics were also analyzed by newly diagnosed versus recurrent disease. Although the groups did not differ in the proportion of PTCL [NOS] cases, most cases of AITL histology were in recurrent patients (57% vs. 8%, p=.003). There was also a trend towards more newly diagnosed patients having B symptoms (58% vs. 29%), however this was not statistically significant, perhaps due to lack of power. No other differences were evident.

Treatment Administration

The majority of patients (n=21; 64%) completed all six cycles of treatment. The remaining patients received either 4 cycles (n=1), 3 cycles (n=3), 2 cycles (n=3), or 1 cycle (n=5). Patients who did not complete treatment were removed due to toxicity (n=2), progression (n=6), early death prior to assessment for response or progression (n=2) or other reasons (n=2).

Adverse Events

The number of patients with a given type and grade of adverse event (AE) are reported while AEs unlikely or not related to treatment are excluded (Table 2). One patient died of infection with Grade 3 or 4 neutropenia, probably related to treatment. Fourteen patients had at worst Grade 3 adverse events and 13 had at worst Grade 4 adverse events. The most common Grade 3 and 4 toxicities were hematologic (n=21), metabolic (n=8), and infection (n=7).

Table 2.

Grade 3 and 4 Adverse Events

| Adverse Event (treatment-related), n=33 | Total | Grade 3 | Grade 4 |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Constitutional | |||

| Fatigue | 18 | 2 | 0 |

| Fever | 4 | 0 | 0 |

|

| |||

| Hematologic | |||

| Neutropenia | 19 | 8 | 7 |

| Anemia | 24 | 7 | 1 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 15 | 2 | 5 |

|

| |||

| Gastrointestinal | |||

| Nausea | 23 | 0 | 0 |

| Vomiting | 9 | 0 | 0 |

| Diarrhea | 12 | 2 | 0 |

| Constipation | 11 | 0 | 0 |

|

| |||

| Infectious | |||

| Febrile Neutropenia | 4 | 3 | 1 |

| Blood infection | 1 (grade 5) | 0 | 0 |

| Other infection | 11 | 5 | 0 |

|

| |||

| Renal/metabolic | |||

| Renal failure | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| Hyperglycemia | 11 | 4 | 0 |

| Hyponatremia | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| Tumor lysis syndrome | 1 | 1 | 0 |

|

| |||

| Neurologic | |||

| CNS Hemorrhage | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Neuropathy | 10 | 1 | 1 |

| Tinnitus | 4 | 1 | 0 |

|

| |||

| Thrombosis/embolism | 0 | 1 | 0 |

|

| |||

| Maximum Grade Any Adverse Event | 27 | 14 | 13 |

Tumor Response

Restaging was performed 4 to 6 weeks after receipt of last cycle of PEGS using modified Cheson criteria [14]. The ORR was 39% (13/33) of which 24% (8/33) were CR/unconfirmed CR and 15% (5/33) were PR. Stable disease (SD) occurred in 12% of patients (4/33). Among the subtypes of T-NHL, the ORR was 47% (7/15) in PTCL [NOS], 33% (2/6) in AITL, 25% (1/4) in ALCL [ALK-] and 38% (3/8) in other T-NHL. The CR was 26% (4/15) in PTCL [NOS], 17% (1/6) in AITL, 25% (1/4 in ALCL [ALK-], and 25% (2/8) in other T-NHL. Among the 26 previously untreated patients, the overall response rate was 38% (10/26), with a CR rate (confirmed and unconfirmed) of 23%, and a PR rate of 15%. Among the 7 previously treated patients, the overall response rate was 43% (3/7), with a CR rate of 29% and a PR rate of 14%.

The median time to response (TTR) was 2.2 months (range, 1.6–2.9 months). Among the 8 patients with a CR (confirmed or unconfirmed), the median TTR was 2.1 months (range, 1.6–2.9 months). Among the 5 patients with a PR, the median TTR was 2.2 months (range, 1.8–2.4 months). The median DR was 19.5 months (95% CI: 3.0–21.2 months). Among the 8 patients with a CR (confirmed or unconfirmed), the median DR was 21.2 months (95% CI: 2.4–21.2 months). Among the 5 patients with a PR, the median DR was 3.0 months (95% CI:1.0–19.5 months).

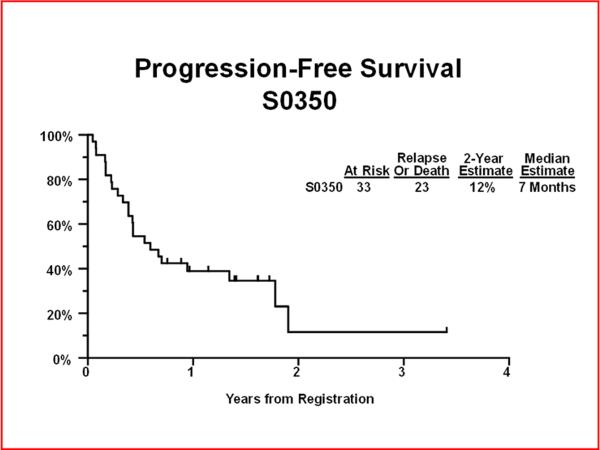

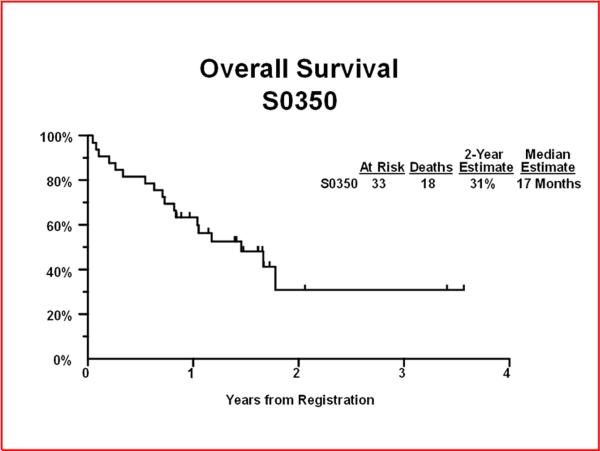

Progression-Free and Overall Survival

Through August 5th, 2011, the median follow-up time among patients still alive was 1.6 years. Twenty-three of 33 eligible patients have relapsed or died. The 2 year PFS was 12% (95% CI: 0.1%–31%) with a median PFS of 7 months (95% CI: 5 – 21 months) (Figure 1). Eighteen patients have died. The 2 year OS was 31% (95% CI: 8%–54%) with a median OS of 17 months (95% CI: 10 months-Not Defined) (Figure 2). Among the 26 newly diagnosed patients only, the 2-year PFS was 14% (95% CI: 0.1%–36%) and 2-year OS was 36% (95% CI: 13%–59%). None of the 7 patients with recurrent disease had progression-free or overall survival times two years or longer.

Figure 1.

Progression Free Survival at 2 years.

Figure 2.

Overall Survival at 2 years.

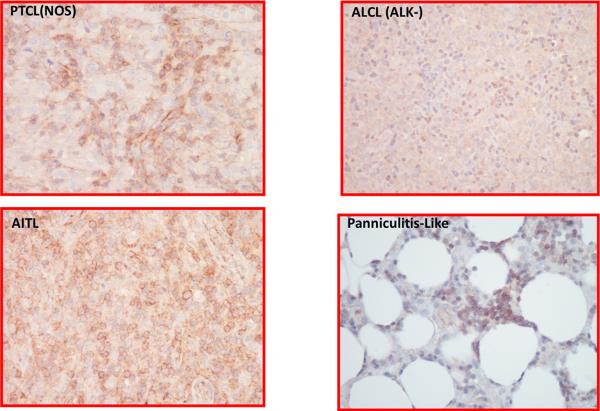

P-glycoprotein (MDR-1/ABCB1) is expressed on PTCL tumor endothelium

Both monoclonal antibodies C494 and JSB-1 were used for detection of P-gp expression. Two patients did not have sufficient tissue for further study, leaving 31 patient samples for analysis. C494 showed reactivity in a subset of tumor cells in 6 patients; these were cases where the tumor cells were large cells. However, at least a subset of small lymphocytes was positive in 20 patients. This included patients whose tumor cells were small in size, making distinction between tumor and residual T cells problematic. Endothelium was focally to diffusely positive in 25 patients. Four representative cases of T-NHL for P-gp expression are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

P-gp by IHC (C494) staining in a representative group of T-cell lymphomas. (A). PTCL [NOS] demonstrates staining of the large cells, (B). AITL shows staining of both large and small cells, (C). ALCL [ALK-] shows reactivity in only a subset of small lymphocytes, (D). Panniculitis-like T cell lymphoma shows staining of the tumor cells that rim the fat cells as well as small foci of small lymphocytes between the adipose cells.

Discussion

The rarity of PTCL makes it difficult to conduct biologically guided clinical trials that help clinicians determine the best therapeutic options for each of the subtypes. This is the largest completed US cooperative group study of PTCL to date.

PTCL patients have been treated similarly to aggressive B-NHL patients with CHOP-21; however, anthracycline-based regimens are associated with a 5 year OS of <40% [15]. In the interim investigators have developed 3 strategies to improve outcomes - dose escalation of standard chemotherapy, new chemotherapy combinations and novel agents [3, 4, 7]. However, none of these strategies have improved OS in PTCL patients. The mechanistic explanation for unresponsiveness to CHOP-like therapy is unknown, but expression of MDR-1/P-gp (ABCB1) and other ABC transporters may be a mechanism of chemo-resistance. Hence, we devised a chemotherapy protocol incorporating agents known to be active in PTCL (e.g. cisplatin, gemcitabine, etoposide and solumedrol) [17, 18, 19] and not effluxed by the ATP-dependent P-gp efflux pump to abrogate drug resistance, with the potential to increase the response rate (RR) with an associated improvement in PFS and OS. The chemotherapy regimen PEGS was based on ESHAP (cisplatin, etoposide, ara-C and methylprednisolone) [20] in which ara-C was replaced with gemcitabine. ESHAP has not been evaluated in PTCL patients except as part of an intensive chemotherapy (high-dose CHOP/ESHAP) followed by autologous stem-cell transplantation in previously untreated patients with peripheral T-cell lymphoma with a CR + PR of 48% [21]. However, ESHAP treatment of relapsed and refractory B-NHL achieved CR + PR of 64%. The median duration of CR was 20 months, with 28% of remitters still in CR at 3 years. The overall median survival duration was 14 months; the survival rate at 3 years was 31%. ESHAP was found to be an active, tolerable chemotherapy regimen for relapsing and refractory lymphoma [20].

Overall PEGS was well tolerated with 21 of 33 patients completing 6 cycles of therapy. The major grade 3/4 AE was myelosuppression, and the only grade 5 AE was systemic infection (Table 2). The observed outcomes, however, have been disappointing - 24% CR/CRu, 15% PR, 12% SD with a median PFS and OS of 9 months and 17 months, respectively, while 2-year PFS was 12% [95% CI: 0.1%–31%] and OS was 31% (95% CI: 8.0%–54%). The results did not reach the design target of two year OS of 67%. Overall response rates were not different between histologic subgroups; however, power to assess differences between subgroups was limited by the small sample size. Results for PFS, OS, and response were similar when the analysis was restricted to 26 previously untreated patients, and are worse than those reported for typical CHOP-based regimens (Table 3) [17, 22–26].

Table 3.

CHOP-based response data for PTCL (NR- not reported)

| Regimen | N | Histology | Response | PFS or EFS or FFS | OS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHOP-21 vs VIP-r-ABVD [21] | 88 |

PTCL 65%

AITL 17% ALCL 16% |

CR: 29% PTCL

53% AITL |

2-year EFS

41% |

Median 42 mo |

| CHOP-like (meta-analysis) [17] | 2912 | NR | CR: 55% | NR | 5-year 37% |

| CHOP-ASCT [22] | 83 |

PTCL 33%

AITL 39% ALCL 16% |

ORR: 79%

CR: 39% |

3-year PFS

~35% |

3-year 48% |

| CHOEP-ASCT [23] | 160 |

PTCL 39%

AITL 19% ALCL 19% |

ORR: 88%

CR: 40% *based on 2006 report |

5-year

PFS 44% |

5-year 51% |

| CHOP-EG [24] | 26 |

PTCL 54%

NKT 31% |

CR:61% | 1-year 50% | 1-year 70% |

| CHOP-alemtuzumab [25] | 24 | PTCL 58% AITL 25% ALCL 12% |

ORR: 75% CR 71% |

1-year 54% | 1-year 70% |

Possible reasons for these disappointing results include relatively unfavorable patient mix, with older patients (median age 60), unfavorable PTCL histologies (no ALCL [ALK+]), and extensive disease (58% stage IV, 67% elevated LDH) (Table 1). Due to expected older cohort and multicenter setting, cisplatin was fractionated at 25 mg/m2 daily days 1–4 and solumedrol doses were reduced to 250 mg days 1–4, which may also have contributed to decreased efficacy. Similarly, if the P-gp hypothesis was not correct, omission of cytarabine may have contributed to decreased regimen efficacy. On the other hand, in the cooperative group trial setting, which represents both academic and community-based centers, may have mitigated selection bias and more realistically reflected the outcomes of chemotherapy in the general population of patients with PTCL.

The DR of PEGS in previously treated patients, however, is relatively favorable when compared to other second-line regimens (Table 4) [27–32], although the number of patients treated in first relapse is too small to draw strong conclusions. This is not surprising considering that PEGS is based on a second-line regimen, ESHAP, and raises the possibility that PEGS may be a viable option for second-line treatment.

Table 4.

Novel agent response data in relapsed PTCL (NR- not reported)

| Regimen | N | Response | DR | PFS | OS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bendamustine [26] | 38 (2 w MF) |

ORR 47%

CR: 29% |

5.1 mo | NR | NR |

| Pralatrexate [27] | 111 | ORR 29%, CR 11% | 10.1 mo | Med 3.5 mo | Med 14.5 mo |

| Romidepsin [28] | 130 |

ORR 25%

CR 15% |

17 mo | Med 4 mo | |

| DHAP-alemtuzumab (+Auto-SCT) [29] | 24 |

ORR 50%

CR |

Med 2.9 mo | NR | Med 6 mo |

| Gem-Cis-Methylpred [30] | 16 |

ORR 69%

CR 19% |

Med 4 mo (TTP) | NR | 1-yr 69% |

| Alemtuzumab [31] | 14 |

ORR 36%

CR 22% |

Med 6 mo | NR | NR |

Previously, it was shown that P-gp is variably expressed in normal peripheral blood T- cells which, in general, overexpress P-gp relative to B-cells [33]. In fact, some subsets of T-cells (CD8 > CD4) and NK-cells express as much as 40-fold the amount of P-gp as circulating B-cells [33]. The level of detection of P-gp is several-fold higher than the level at which drug resistance is observed and its expression is further increased in relapsed/refractory disease for both T- and B-NHL. In the S0350 study, the analysis of P-gp expression was conducted on diagnostic (pre-treatment) biopsies and post-treatment biopsies were not available. P-gp expression was positive on small T-cells (n=20) and in a subset of large T-cells (n=6) within the tumor. The pattern P-gp of expression varied among these lymphomas with PTCL[NOS], ALCL[ALK−], AITL and panniculitis-like T-NHL (Figure 3).

Twenty five patients demonstrated P-gp expression on the tumor vascular endothelium (Figure 3). ABC transporters are known to decorate the luminal plasma membrane of the brain capillary endothelium facing the vascular space and to protect the central nervous system from entry of neurotoxins [34, 35]. Our data imply that the tumor microenvironment of small T-lymphocytes and blood vessels that overexpress P-gp, effectively efflux administered chemotherapy and allow tumor growth in the presence of chemotherapy. This may explain ineffectiveness of anthracycline-based chemotherapy in PTCL. Further, it is known that doxorubicin enhances constitutive P-gp expression resulting in exclusion of doxorubicin from tumor cells and endothelial cells of the tumor vasculature [35]. Since vascularization and P-gp expression are prerequisites for tumor growth in a hypoxic environment [36], inhibition of P-gp in tumor endothelial cells may be a clinical approach to enhance effectiveness of chemotherapy. Of interest, in nine PTCL patients where Bcl2 expression was evaluated, eight demonstrated its elaboration within tumor cells. This finding coupled with an environment where drug levels are sub-therapeutic due to P-gp expression may explain the poor relapse free survival and outcome in a majority of the patients.

In conclusion, S0350 is the largest completed US cooperative group study of PTCL to date that tested a novel chemotherapy regimen PEGS (cisplatin, etoposide, gemcitabine, solumedrol). Further work on P-gp should focus not only on tumor cells but on tumor microenvironment including the blood vessels. PEGS may be considered a benchmark for future comparisons for non-CHOP regimens in PTCL, and for design of rational combinations with targeted agents.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank the patients who participated in this clinical study, their families, SWOG Operations Office and Statistical Center, and all of the contributing member sites.

Funding This investigation was supported in part by the following PHS Cooperative Agreement grant numbers awarded by the National Cancer Institute, DHHS: CA32102, CA38926, CA11083, CA13612, CA45807, CA46282, CA20319, CA46441, CA46136, CA128567, CA142559, CA63848, CA37981, CA35119 and in part by Eli Lilly and Company.

Clinical Trials Registration Identification Number: NCT00109928

Footnotes

The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Savage KJ. Prognosis and Primary Therapy in Peripheral T-Cell Lymphomas. Hematology Am Soc. Hematol. Educ. Program. 2008:280–8. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2008.1.280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO classification of tumors of hematopoietic and lymphoid tissues. 4th ed. IARC Press; Lyon: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mahadevan D, Fisher RI. Novel therapeutics for aggressive non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. J Clin. Oncol. 2011;29(14):1876–84. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.7171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Savage KJ, Harris NL, Vose JM, et al. ALK-anaplastic large-cell lymphoma is clinically and immunophenotypically different from both ALK+ ALCL and peripheral T-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified: report from the International Peripheral T-Cell Lymphoma Project. Blood. 2008;103(12):3152–3158. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-01-134270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gisselbrecht C, Gaulard P, Lepage E, et al. Prognostic Significance of T-Cell Phenotype in Aggressive Non-Hodgkin's Lymphomas. Blood. 1998;92(1):76–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vose J, Armitage J, Weisenburger D. International peripheral T-cell and natural killer/T-cell lymphoma study: pathology findings and clinical outcomes. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008;26(25):4124–4130. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.4558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Foss FM, Zinzani PL, Vose JM, et al. Peripheral T-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2011;117(25):6756–67. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-05-231548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nademanee A, Palmer JM, Popplewell L, Tsai NC, Delioukina M, Gaal K, Cai JL, Kogut N, Forman SJ. High-dose therapy and autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation in peripheral T cell lymphoma (PTCL): analysis of prognostic factors. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2011;17(10):1481–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2011.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blayney DW, LeBlanc ML, Grogan T, et al. Dose-Intense Chemotherapy Every 2 Weeks With Dose-Intense Cyclophosphamide, Doxorubicin, Vincristine, and Prednisone May Improve Survival in Intermediate- and High-Grade Lymphoma: A Phase II Study of the Southwest Oncology Group (SWOG 9349) Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2003;21(13):2466–2473. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.06.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pescarmona E, Pignoloni P, Puopolo M, et al. p53 over-expression identifies a subset of nodal peripheral T-cell lymphomas with a distinctive biological profile and poor clinical outcome. J. Pathol. 2001;195(3):361–6. doi: 10.1002/path.945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mahadevan D, List AF. Targeting the multidrug resistance-1 transporter in AML: molecular regulation and therapeutic strategies. Blood. 2004;104(7):1940–51. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-07-2490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zinzani P, Baliva G, Magagnoli M, et al. Gemcitabine treatment in pretreated cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: experience in 44 patients. J. Clin. Oncol. 2000;18:2615–2619. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.13.2603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ann Arbor Classification. 6th ed. 2002. AJCC Manual for Staging of Cancer. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cheson BD, Horning SJ, Coiffier B, et al. Report of an international workshop to standardize response criteria for non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: NCI Sponsored International Working Group. J. Clin. Oncol. 1999;17:1244–1253. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.4.1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaplan B, et al. Histopathology and immunophenotype of the spleen during acute antibody mediated rejection. Am. J Transplantation. 2010;10:1316–1319. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2010.03067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric estimations from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc. 1958;53:457–481. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abouyabis AN, Shenoy PJ, Sinha R, et al. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Front-line Anthracycline-Based Chemotherapy Regimens for Peripheral T-Cell Lymphoma. ISRN Hematol. 2011;2011:623924. doi: 10.5402/2011/623924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crump M, Shepherd L, Lin B. A randomized phase III study of gemcitabine, dexamethasone, and cisplatin versus dexamethasone, cytarabine, and cisplatin as salvage chemotherapy followed by post-transplantation rituximab maintenance therapy versus observation for treatment of aggressive B-Cell and T-Cell non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Clin Lymphoma. 2005;6(1):56–60. doi: 10.3816/clm.2005.n.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pfreundschuh M, Trumper L, Kloess M, et al. Two-weekly or 3-weekly CHOP chemotherapy with or without etoposide for the treatment of elderly patients with aggressive lymphomas: results of the NHL-B2 trial of the DSHNHL. Blood. 2004;104(3):634–41. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-06-2095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Velasquez WS, McLaughlin P, Tucker S, et al. ESHAP--an effective chemotherapy regimen in refractory and relapsing lymphoma: a 4-year follow-up study. J Clin Oncol. 1994;12(6):1169–76. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1994.12.6.1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mercadal S, Briones J, Xicoy B, et al. Intensive chemotherapy (high-dose CHOP/ESHAP regimen) followed by autologous stem-cell transplantation in previously untreated patients with peripheral T-cell lymphoma. Ann Oncol. 2008;19(5):958–63. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Simon A, Peoch M, Casassus P, et al. Upfront VIP-reinforced-ABVD (VIP-r-ABVD) is not superior to CHOP/21 in newly diagnosed peripheral T cell lymphoma. Results of the randomized phase III trial GOELAMS-LTP95. Br J Haematol. 2010;151(2):159–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2010.08329.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reimer P, Rüdiger T, Geissinger E, et al. Autologous stem-cell transplantation as first-line therapy in peripheral T-cell lymphomas: results of a prospective multicenter study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(1):106–13. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.4870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.d'Amore F, Relander T, Lauritzsen GF, et al. High-Dose Chemotherapy and Autologuos Stem Cell Transplantation in Previously Untreated Peripheral T-Cell Lymphoma - Final Analysis of a Large Prospective Multicenter Study (NLG-T-01) Blood. 2011;118 ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts. Abstract 331. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim JG, Sohn SK, Chae YS, et al. CHOP plus etoposide and gemcitabine (CHOP-EG) as front-line chemotherapy for patients with peripheral T cell lymphomas. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2006;58(1):35–9. doi: 10.1007/s00280-005-0136-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gallamini A, Zaja F, Patti C, et al. Alemtuzumab (Campath-1H) and CHOP chemotherapy as first-line treatment of peripheral T-cell lymphoma: results of a GITIL (Gruppo Italiano Terapie Innovative nei Linfomi) prospective multicenter trial. Blood. 2007;110(7):2316–23. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-02-074641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Damaj G, Gressin R, Bouabdallah K, et al. Preliminary results from an open-label, multicenter, phase II study of Bendamustine in relapsed or refractory T-cell lymphoma from the French GOELAMS group: The Bently Trial. Ann Oncol. 2011;22(suppl 4) [Google Scholar]

- 28.O'Connor OA, Pro B, Pinter-Brown L, et al. Pralatrexate in patients with relapsed or refractory peripheral T-cell lymphoma: results from the pivotal PROPEL study. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(9):1182–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.29.9024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Coiffier B, Pro B, Prince HM, et al. Results from a Pivotal, Open-Label, Phase II Study of Romidepsin in Relapsed or Refractory Peripheral T-Cell Lymphoma after Prior Systemic Therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(6):631–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.37.4223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim SJ, Kim K, Park Y, et al. Dose modification of alemtuzumab in combination with dexamethasone, cytarabine, and cisplatin in patients with relapsed or refractory peripheral T-cell lymphoma: analysis of efficacy and toxicity. Invest New Drugs. 2012;30(1):368–75. doi: 10.1007/s10637-010-9523-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arkenau HT, Chong G, Cunningham D, et al. Gemcitabine, cisplatin and methylprednisolone for the treatment of patients with peripheral T-cell lymphoma: the Royal Marsden Hospital experience. Haematologica. 2007;92(2):271–2. doi: 10.3324/haematol.10737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Enblad G, Hagberg H, Erlanson M, et al. A pilot study of alemtuzumab (anti-CD52 monoclonal antibody) therapy for patients with relapsed or chemotherapy-refractory peripheral T-cell lymphomas. Blood. 2004;103(8):2920–4. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-10-3389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Klimecki W, Futscher B, Grogan T, et al. P-glycoprotein expression and function in circulating blood cells from normal volunteers. Blood. 1994;83:2451–2458. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miller DS. Regulation of P-glycoprotein and other ABC drug transporters at the blood-brain barrier. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2010;31(6):246–54. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rittierodt M, Harada K. Repetitive doxorubicin treatment of glioblastoma enhances the PGP expression: a special role for endothelial cells. Exp Toxicol Pathol. 2003;55(1):39–44. doi: 10.1078/0940-2993-00287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Comerford KM, Wallace TJ, Karhausen J, et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1-dependent regulation of the multidrug resistance (MDR1) gene. Cancer Res. 2002;62(12):3387–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]