Abstract

Schwannomas of the intra oral region are relatively uncommon; these are benign nerve sheath tumors that arise from schwann cells of the neural sheath. They are solitary, slow-growing, smooth-surfaced, usually asymptomatic, and encapsulated tumors, about 25% of all schwannomas are located in the head and neck, but only 1% show intraoral origin. We are contributing a report of 24 years old woman with slow progressive swelling over the right retromolar region. Magnetic resonance imaging presented a well defined mass over the right retromolar area measuring 19 × 19 mm2 and fine needle aspiration cytology revealed that it was a tumor mass of neurogenic origin. Diagnosis was confirmed by excisional histological identification of Antoni A areas with marked palisading of nuclei. Although these rare entities of oral cavity are routinely not encountered in practice, they should be added in differential diagnosis of intraoral tumors.

Keywords: Schwannoma, Neurogenic tumor, Soft tissue tumor, Intraoral tumor

Introduction

Schwannoma also referred to as neurilemmomas or neuronommas are benign nerve sheath tumors that arise from schwann cells of the neural sheath of peripheral, spinal or cranial nerve [1]. They are solitary, slow-growing, smooth-surfaced, usually asymptomatic, and encapsulated tumors [2]. Although they may arise at any age, the peak incidence is between the third and sixth decades [3]. There is no gender predilection; about 25% of all schwannomas are located in the head and neck, but only 1% show intraoral origin [4]. The intraoral lesions show a predilection for the tongue, with the tip being the least affected part, the palate, buccal mucosa, lip, and gingiva are also affected in decreasing order [3]. Malignant transformation is rare; Das Gupta and Brasfield [5] found an incidence of 8% of malignant schwannomas in the head and neck. However, Yamashita et al. [6] reported one case of schwannoma over the retromolar region which has ever been documented in literature. We report, to our knowledge, the second known case of intra oral schwannoma over the retromolar area.

Case Report

A 24 year old female patient reported to unit with complaint of mild swelling over right back tooth region. The swelling was associated with pain during mastication. There was no complaint of parethesia of any region. The lesion had appeared 11 months earlier as small nodule and gradually increased in size. The patient was otherwise healthy and had no significant past medical history and no other symptoms; her family history was also unremarkable. On examination an approximate 20 mm diameter mass was observed over the right retromolar region with overlying ulcerated mucosa due to impingement of upper right second molar while closing of mouth. The mass was firm, non tender and relatively mobile (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Tumor mass over right retromolar area with overlying ulcer

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a mass with a clear and smooth border in retro molar region measuring about 19 × 19 mm2, there was no obvious abnormalities of surrounding soft tissues (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Magnetic imaging resonance reveals well define mass measuring 19 × 19 mm2

The complete blood count, biochemistry tests (aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, lactate dehydrogenase, alkaline phosphatase, total protein, and C-reactive protein), and renal function tests (uric acid, blood urea nitrogen, and creatinine) all gave results within normal limits. Fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) was performed, and the lesion was diagnosed as a benign tumor of neurogenic origin. Based on the diagnosis of a benign tumor, excision of the tumor was performed under general anesthesia. The excised tumor measured about 20 × 20 × 20 mm and was encapsulated with fibrous connective tissue. Macroscopic appearance was oval, solid, and grayish white in color (Fig. 3) and had diffuse brown pigmentation on the cut surface.

Fig. 3.

Intra operative picture shows exposed tumor mass

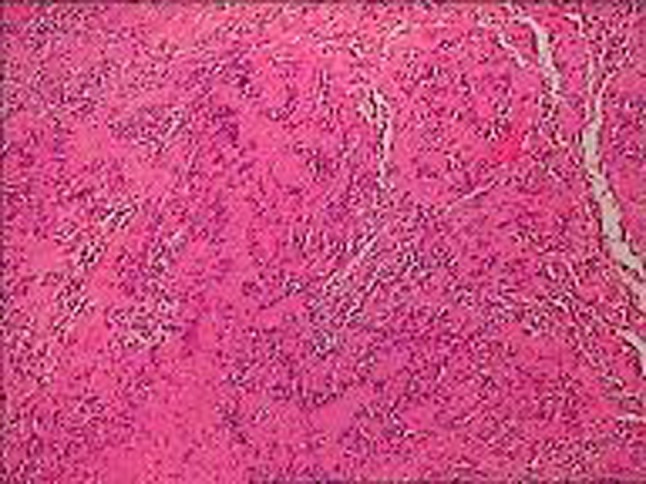

Histological study shows tumor consist of predominantly Antoni A areas with marked palisading of nuclei (H&E ×50) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Histological slide shows tumor consisting predominantly Antoni A areas with marked palisading of nuclei (H&E ×50)

Discussion

Schwannomas, being rare in the oral cavity, represent a lesion not often encountered in clinical practice. Embryologically, schwann cells arise during the fourth week of development from a specialized population of ectomesenchymal cells of the neural crest, which then detach from the neural tube and migrate into the embryo. Schwann cells form a thin barrier around each extracranial nerve fiber and wrap larger fibers with an insulating membrane, myelin sheath, to enhance nerve conductance. As nerves exit the brain and spinal cord, there is a change between myelination by oligodendrocytes to myelination by schwann cells. Schwannomas arise when proliferating schwann cells form a tumor mass (unknown etiology) encompassing motor and sensory peripheral nerves [3].

The lesion is usually single, circumscribed, firm, painless, and of variable size, ulceration of the overlying mucosa is rare and generally the result of trauma [4]. These tumors may arise any part of the body, intraoral incidence of origin is about 1% only. In the oral cavity, schwannoma is found most commonly in the tongue, due to mobility of the tongue it is apt to receive stimuli that enlarge a tumor; also, it is comparatively easy to detect a lesion in the tongue [4]. Gallo et al. [7] reported on 157 cases where 45.2% of the cases involved the tongue and 13.3% involved the cheek. Das Gupta et al. [5] reported on 136 cases of schwannoma in the head and neck that consisted of 60 cases in the neck, 10 cases in the parotid gland, 9 cases in the cheek, 8 cases in the tongue, and 8 cases in the pharynx. Kun et al. [8] reported in their study that 18 out of 49 cases were in the neck and 11 cases were in the tongue.

Radiological imaging by computed tomography (CT) shows schwannomas to be well-circumscribed, homogeneous masses that enhance with contrast. The use of CT is less than ideal because it can be limited by bone artifact, especially when imaging smaller lesions. Its true value lies is in its ability to determine the amount adjacent bony damage that has occurred secondarily to schwannoma growth [9]. MRI is the imaging modality of choice for radiological evaluation of schwannomas because of its increased tissue contrast and spatial resolution when compared to CT. MRI detects tumors that are too small or hindered by artifact to be viewed with CT. Most schwannomas appear hypointense or isointense relative td muscle on T1-weighted images. With T2-weighted MRI, the tumor is usually homogenous in signal intensity, although cysts or degenerative changes within the schwannoma may be seen [9].

Macroscopically, schwannomas are typically circumscribed and encapsulated. Histopathologically, five schwannoma variants have been described: common, plexiform, cellular, epithelioid, and ancient schwannomas [10]. In common schwannoma two distinct histological patterns can be seen: known as Antoni type A and type B. Antoni type A tissues are characterized by compact schwann cells with nuclear palisading, whereas Antoni type B tissues exhibit a considerable degree of cell pleomorphism in a loosely arranged reticulum network. Vascularity is not a prominent feature, and necrosis and mitotic activity are seldom encountered [1]. Sometimes in type A, the cells are aligned in palisade manner with the nuclei lying side by side in one strip and cytoplasm of cells in the adjacent strip, this pattern known as “Verokay body” [4]. This pattern was not appreciated in our case. As the schwannoma ages, degenerative changes take place, characterized by hyalinized tissue, myxoid areas, and large cystic spaces. The resulting entity is known as ancient schwannoma. Malignant transformation is rare [5].

In evaluating a patient with a slow-growing tongue mass that has been present for a long period of time, benign soft tissue neoplasms and reactive lesions need to be considered. In addition to schwannomas, the differential diagnosis should include neurofibromas, granular cell tumors, irritation fibromas, leiomyomas, rhabdomyomas, hemangiomas, lymphangiomas, lipomas, pyogenic granulomas, and benign salivary gland tumors, nerve sheath myxoma, palisaded encapsulated neurinoma, mucosal neurinoma associated with multiple endocrine neoplasia III, traumatic neuroma and granular cell tumour [11].

The presence of schwannoma calls for the careful search for nerve tumors in other parts of the body, although in most cases none may be found. The differentiation of schwannoma from neurofibroma is essential, because an apparently solitary neurofibroma may be a manifestation of neurofibromatosis. They are distributed in a centripetal fashion on the body [12].

Microscopically, both schwannoma and the neurofibroma contain elongated cells with irregular nuclei lying between bundles of collagen fibers. They differ histologically and histogenetically, the schwannoma is derived from the Schwann cells and the neurofibroma from mixture of Schwann cells, perineurial cells, and endoneurial fibroblasts. Neurofibroma is unencapsulated [13].

The diagnosis of schwannoma presenting in this unusual location in our patient would have been difficult to make based upon routine haematoxylin and eosin stains alone. Immunohistochemistry is a simple, accurate, and cost-effective technique used in the diagnosis of schwannoma. S-100 protein is a diagnostic immunohistochemical marker for schwannoma [14].

Treatment should be confined to complete excision, wide excision is not advocated. Neck dissection is not necessary, because lymphatic spread and metastases are rare [15]. Cure entails a complete resection but this conflicts with the surgical instinct to preserve the nerve of origin. The role of radiosurgery as an alternative to surgical resection is a matter of ongoing debate. This technique is reserve for those cases in which schwanomma is originated from definitive nerve trunks, e.g. trigeminal, laryngeal, vagus, vestibular nerve [16]. This technique was not applicable in our presented case.

Schwannomas are not radiosensitive, so radiotherapy plays no role with these lesions [4]. Prognosis for complete cure in the benign schwannoma in the oral cavity is excellent; few schwannoma recur after complete surgical excision.

Conclusion

Only a few cases of schwannoma in the oral floor have been reported. With approximately one third of all documented cases presenting in the head and neck region, the diagnostic difficulties are discussed and, however, when the characteristics findings are observed on CT and MRI, Schwannoma should be added to the differential diagnosis. Schwannoma are best treated by total surgical resection, which yields acceptable results with low rates of mortality and permanent morbidity.

References

- 1.Bildirici K, Cakli H, Kecik H, Dundar E, Agikalin MF. Schwannoma (neurilemmomas) of the palatine tonsil. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;126(6):693–694. doi: 10.1067/mhn.2002.123926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lall GS, Walsh RM, Rowlands DC. Schwannoma (neurilemmoma) of the tonsil. J Laryngol Otol. 1999;113(6):585–586. doi: 10.1017/S002221510014455X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pfeifle R, Baur DA, Paulino A, Helman J. Schwannoma of the tongue: report of 2 cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2001;59(7):802–804. doi: 10.1053/joms.2001.24298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jornet PL, Fenoll AB. Neurilemmoma of the tongue. Oral Oncol Extra. 2005;41:154–157. doi: 10.1016/j.ooe.2005.03.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Das Gupta TK, Brasfield RD. Solitary schwannoma. Ann Surg. 1976;171(3):419. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197003000-00016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yamashita T, Toida M, Hatakeyama D, Yonemoto K, Kusunoki Y, Shibata T. Schwannoma of the oral cavity. Asian J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006;18:75–78. doi: 10.1016/S0915-6992(06)80036-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gallo WJ, Moss M, Shapiro DN, Gaul JV. Neurilemmoma: review of the literature and report of five cases. J Oral Surg. 1977;35(5):235–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kun Z, Dao-Yi QI, Kui-Hua Z. A comparison between the clinical behaviors of neurilemmomas in the neck and oral and maxillofacial region. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1993;51(7):769–771. doi: 10.1016/S0278-2391(10)80419-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sawhney R, Carron MA, Mathog RH. Tongue base schwannoma: report, review, and unique surgical approach. Am J Otolaryngol–Head Neck Surg. 2008;29(2):119–122. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weiss SW, Goldblum JR. Parotis schwannoma. In: Enzinger SW, Weiss SW, editors. Enzinger and Weiss’s soft tissue tumors. 4. Saint Louis: Mosby; 2001. pp. 1146–1167. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hatziotis JC, Asprides H. Neurilemmoma (schwannoma) of the oral cavity. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1967;24:510–526. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(67)90431-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wright BA, Jackson D. Neural tumors of the oral cavity: a review of the spectrum of benign and malignant oral tumors of the oral cavity and jaws. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1980;49(6):509–522. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(80)90075-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Requena L, Sangueza OP. Benign neoplasms with neural differentiation: a review. Am J Dermatopathol. 1995;17(1):75–96. doi: 10.1097/00000372-199502000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schnitt SJ, Vogel H. Diagnostic value of immunoperoxidase staining for epithelial membrane antigen. Am J Surg Pathol. 1986;10(9):640–649. doi: 10.1097/00000478-198609000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Conley J, Janecka IP. Neurilemmoma of the head and neck. Trans Am Acad Ophthalmol Otol. 1975;80(5):459–464. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang CF, Kondziolka D, Flickinger JC, Lunsford LD. Stereotactic radiosurgery for trigeminal schwannomas. Neurosurgery. 1999;45(1):11–16. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199907000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]