Abstract

The variations in architecture of gallium-seamed (PgC4Ga) and gallium-zinc-seamed (PgC4GaZn) C-butylpyrogallol[4]arene nanoassemblies in solution (SANS/NMR) versus the solid state (XRD) have been investigated. Rearrangement from the solid-state spheroidal to the solution-phase toroidal shape differentiates the gallium-containing pyrogallol[4]arene nanoassemblies from all other PgCnM nanocapsules studied thus far. Different structural arrangements of the metals and arenes of PgC4Ga versus PgC4GaZn have been deduced from the different toroidal dimensions, C–H proton environments and guest encapsulation of the two toroids. PGAA of mixed-metal hexamers reveals a decrease in gallium-to-metal ratio as the second metal varies from cobalt to zinc. Overall, the combined study demonstrates the versatility of gallium in directing the self-assembly of pyrogallol[4]arenes into novel nanoarchitectures.

Keywords: pyrogallol[4]arene, SANS, gallium, toroid, supramolecular chemistry

The synthesis of metal-seamed architectures continues to attract wide attention among supramolecular chemists. Understanding the properties of such metal-seamed systems could lead to practical applications such as biological probes,[1] electronic nanodevices[2] or luminescent superparamagnetic hybrids.[3] Investigation of metal-seamed pyrogallol[4]arene organic nanocapsules (MONCs) dates back to 2005 with the formation of copper-seamed C-propan-3-ol-pyrogallol[4]arene hexamers.[4] In this assembly, six pyrogallol[4]arenes are partially deprotonated to yield a small rhombicuboctahedron with eight triangular [of (O-Cu-O)3 units] and eighteen square faces. Later, zinc-seamed C-propylpyrogallol[4]arene (PgC3Zn, where 3 is the alkyl chain length) dimeric nanocapsule formation was synthesized.[5]

Gallium is of particular interest with respect to MONCs, owing to its semiconducting properties and its ability to assemble into interesting architectures. For example, gallium cages,[6] gallium nanoparticles,[7] single-wall gallium nitride nanotubes[8] and GaP nanowires, nanocables and nanobelts[9] have been reported. Amongst the pyrogallol[4]arene frameworks, gallium-containing scaffolds are unique in several aspects, such as the diversity of architectures, the metal to pyrogallol[4]arene ratio and the metal oxidation state.

Unlike the other observed dimeric and hexameric pyrogallol[4]arene nanocapsules, which are spherical, the gallium-seamed C-butylpyrogallol[4]arene (PgC4Ga) hexamers have a distorted `rugby-ball' shape.[10] Compared to 24 copper atoms in a typical spherical hexamer, only 12 gallium atoms, along with four water molecules, seam this hexameric assembly. These gallium-seamed nanocapsules are particularly interesting owing to the Ga+3 ions occupying Ga3(μ3-O)3(O)6 units on opposite planes seaming only four of the six PgC4 moieties of the hexameric framework.[10] Water molecules seam the remaining two PgC4 moieties, providing the first partially hydrogen-bonded metal-seamed hexamer. The gated aqueous channels can be utilized for ion transportation to the interior of the capsules.[11]

Gallium continued to show distinctive behaviour when mixed-metal hexamers were synthesized.[11a] Addition of a second metal to a pre-formed gallium hexamer caused a transition in structure from the distorted rugby ball to a sphere. Subsequently, hexameric spheres of gallium-zinc, gallium-copper, gallium-nickel and gallium-cobalt combinations were found.[11a] It was, however, difficult to distinguish between the metal atoms using single-crystal XRD because of the similar electronic densities of the metals involved. Hence, inductively coupled plasma (ICP) analyses were conducted to confirm the presence of the second metal and to obtain an approximate ratio of the metal ions in the framework.[11a]

Given the interesting solid-state properties of the gallium-based nanocapsules, we have investigated their geometric dimensions and shapes in solution with small-angle neutron scattering (SANS). We have also performed prompt gamma activation analysis (PGAA) of the solid-state capsules to support the earlier ICP results. To our knowledge, the only other solution-phase study of PgC4Ga mixed-metal hexamers is a 1H NMR study (CD3CN) comparing the PgC4GaZn hexamer to the PgC4Ga hexamer.[12] The one definitive conclusion obtained from these studies was that solvent is encapsulated only in the presence of zinc. To obtain more specific structural details, we performed SANS measurements, 1-D NMR and 2-D HMQC and diffusion-ordered NMR spectroscopy for the PgC4Ga and PgC4GaZn nanoassemblies. Previously, we have employed SANS to examine the self-assembly process and geometric dimensions of the spherical PgC3Cu and PgC3Ni hexamers and dimers in solution.[13] These two sets of experiments will allow us to identify any differences in the behaviour of a typical transition metal (copper/nickel)-seamed PgCn sphere and a gallium-seamed PgCn distorted rugby ball.

The PgC4Ga hexameric crystals were formed by the earlier reported method of mixing acetone solubilized PgC4 (0.26 × 10−3 mol/L) with water solubilized gallium nitrate (0.28 g in 2 mL water).[12] Likewise, the PgC4GaZn hexamer crystals were obtained by adding a zinc-nitrate ethanolic solution (0.28 g in 2 mL) to pre-formed and dried PgC4Ga crystals that had been dissolved in acetone (0.015 × 10−3 mol/L).[12] A similar method was followed for the preparation of the Ga/Ni, Ga/Co and Ga/Cu mixed-metal nanocapsules. Slow evaporation of each solution led to crystals suitable for structure elucidation. The unit cells for these crystals matched those obtained previously.[11a]

Cold neutron PGAA[14] was conducted to investigate the metal ratios in mixed-metal pyrogallol[4]arene frameworks and the results are compared with the earlier ICP analyses in Table 2. Interestingly, however, the new measurements lead to a noticeable trend in the metal ratios across the periodic table. The average mmol ratios of Ga+3:M+2 decrease from approximately 2.8 for Ga+3:Co+2 to 1.8 for Ga+3:Ni+2 to 1.4 for Ga+3:Cu+2 and to 1.3 for Ga+3:Zn+2. That is, as the atomic number of the transition metal increases, the transition metal fills more sites in the Ga/M hexameric framework, suggesting an enhanced affinity to stitch the hexameric framework from cobalt to zinc (Table 1).

Table 2.

Resolution-smeared hollow cylinder fits to nanoassemblies of C-butylpyrogallol[4]arene gallium-zinc and gallium.a

| SAMPLE | Unitb (Å) | SQRT (χ2/N) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PgC4GaZn | Rcore | 6.31 ± 0.15 | 1.07 |

| Rshell | 14.52 ± 0.11 | ||

| L | 13.10 ± 0.24 | ||

| PgC4Ga | Rcore | 4.78 ± 0.27 | 1.307 |

| Rshell | 16.8 ± 0.17 | ||

| L | 6.9 ± 0.36 |

Rcore = core radius; Rshell = shell radius; L = height

Uncertainties in the fitted parameters are one standard deviation.

Table 1.

Metal ratios from Prompt Gamma Activation Analysis (PGAA) of Ga/M-seamed pyrogallol[4]arene hexamers.a

| Metal 1:Metal 2 | ICP Analysisb | PGAA |

|---|---|---|

| Ga : Zn | 14 : 10 | 13.5 : 10.5 |

| Ga : Cu | 13 : 11 | 14 : 10 |

| Ga : Ni | 15 : 9 | 15 : 9 |

| Ga : Co | 16 : 8 | 18 : 6 |

Expanded uncertainties for PGAA values are estimated at ≤ 5 % based on counting statistics, background subtraction, purity of the standards, and neutron flux uncertainties.

The SANS measurements were conducted on the NG7 30m SANS instrument at the NIST Center for Neutron Research (NIST-NCNR) in Gaithersburg, MD.[15] Neutrons of wavelength λ = 6 Å with full width half-maximum Δλ/λ = 15% were used. Sample to detector distances of 1.3 m and 6 m were employed to cover the q range of 0.012 Å−1 < q < 0.52 Å−1, where q is the scattering vector. Pre-formed PgC4Ga hexamers[11a] and PgC4GaZn hexamers[11a] were dissolved separately in deuterated (d6)-acetone at a mass fraction of 2%. Deuterated solvents improve the scattering contrast and thus the coherent scattering of neutrons that contains the structural information. The collected scattering data was then reduced and analyzed on software provided by NIST.[16] Factors such as instrumental geometry, apertures, wavelength spread, effect of gravity on neutron trajectory, etc. have been taken into account by employing resolution-smeared models for the data fitting and modelling. Smeared models provide a more accurate representation of the (smeared) experimentally measured scattering data.

The SANS data for typical PgC3M hexamers and dimers fit to a polydisperse sphere,[17] with a radius of ≈10 Å and ≈7 Å, respectively.[13] These solution phase measurements correspond well with the previously reported XRD structures, which establishes the robustness of pyrogallol[4]arene-based MONCs in solution.[5, 13, 18] Given this parallel connection in shape and size in solution and solid phases, we expected the solution-phase scattering data for the PgC4Ga and PgC4GaZn nanoassemblies to fit to an ellipsoid and sphere, respectively. However, the fits to the uniform ellipsoid[19] and Schulz sphere[17a, 20] models are of poor quality and indicate, for the first time, differences in the architectures of the nanoassemblies in the two phases (supporting information).

The PgC4Ga and PgC4GaZn neutron scattering data were then fitted to spherical polydisperse core-shell,[21] prolate core-shell[17b, 22] and hollow cylinder[19] models (see supporting information). The quality of the fit for the first two models is again very poor; the data fit exceptionally well, however, to the hollow cylinder model for both PgC4GaZn and PgC4Ga (Figures 1 and 2; Table 2). These are the first examples of cylindrical-shaped pyrogallol[4]arene nanoassemblies in solution. For this model, the scattering length densities (SLD) for the shell were calculated as 1.63×10−6 Å−2 and 1.8×10−6 Å−2 for PgC4Ga and PgC4GaZn, respectively. The solvent (d6-acetone) SLD was calculated as 5.39×10−6 Å−2 and fixed to the hollow core.[19]

Figure 1.

Pictorial representations of the geometries of gallium-seamed nanoassemblies as a function of addition of a second metal and change in phase.

Figure 2.

SANS data for the gallium-seamed C-butylpyrogallol[4]arene nanocapsule.The SANS data is fitted to a resolution-smeared hollow cylinder model (see text). Error bars on the SANS data represent one standard deviation.

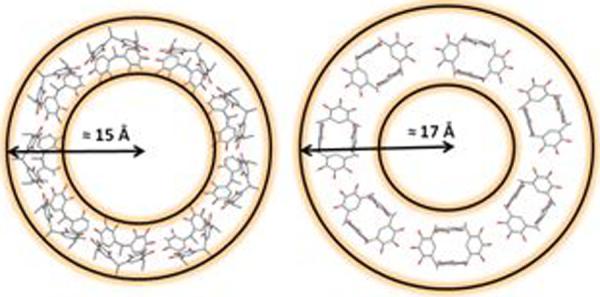

Comparing the values from the fits, there is a minor variation in the core and shell sizes. The inner radius (core) increases by ≈1.5 Å and the outer radius (shell) decreases by ≈2 Å for PgC4Ga compared to PgC4GaZn. Overall, the shell thickness is about 4 Å larger for PgC4Ga (≈12 Å) than for PgC4GaZn (≈8 Å). In contrast, the length of the cylinder for PgC4GaZn (≈13 Å) is twice that for PgC4Ga (≈7 Å). Unexpectedly, the outer radius is larger than the length of the cylinder for both the PgC4Ga and PgC4GaZn species in solution. In fact, for the former species the shell diameter (≈34 Å) is more than four times the length of the cylinder, whereas for the latter species the shell diameter (≈29 Å) is more than twice the length of the cylinder (Table 2). The shape of the PgC4Ga species in solution is thus a “donut-shaped/toroidal-shaped” assembly that expands in length on addition of the zinc metal ion. Similar self-assembled spherical and toroidal frameworks of dendrimersomes have been observed by Presec et al., reflecting the adaptibility of intermolecular interactions.[23]

It is important to note that PgCns are not cylindrical in either the solid or solution phase. Hence, both the metal and solvent are playing a role in directing the solution-phase hollow cylindrical/toroidal architectures of the PgC4Ga and PgC4GaZn assemblies. It remains to be seen whether this interesting result will be observed for other gallium-based, mixed-metal species.

The variations in the structures of PgC4Ga and PgC4GaZn in the two phases suggest a conformational change in d6-acetone. To further study their solution-phase behavior and exhange dynamics, the PgC4Ga and PgC4GaZn nanoassemblies were investigated through 1H, 13C, 71Ga, HMQC and diffusion-ordered (DOSY) NMR spectroscopy techniques. Because the peaks in the 13C 1-D NMR spectra are too broad to be observed with sufficient signal-to-noise ratio, the 13C peak positions for the linker and aromatic groups have been assigned via one-bond carbon-proton correlation in the HMQC (supporting information). HMQC indicates that the group of broad proton peaks between 6 and 8 ppm derive from protons directly bonded to the phenyl carbons (110 ppm) and that the peaks at 4.5 ppm derive from protons directly bonded to the linker carbons (35 ppm). The proton signals at 0.94 ppm and 1.4 ppm are correlated to the carbons of the -CH3 (14 ppm) and -CH2 (22 and 32 ppm) moieties, respectively, of the alkyl chains (supporting information). In addition to the peak broadening, the 1H NMR spectra of PgC4Ga and PgC4GaZn show multiple peaks associated with the aromatic -CH and linker -CH protons, in contrast to the single 1H signal from each of the two groups in PgC4. PgC4Ga and PgC4GaZn show at least three environments for the aromatic -CH group and two environments for the linker -CH group. Note also the switch in the relative peak heights for the two sets of protons in the two toroidal nanoassemblies (supporting information).

Two peaks in the negative region (0 and -1.7 ppm) in the 1H NMR spectra are observed only for PgC4GaZn, suggesting that small molecules are encapsulated in only this toroidal nanoassembly. This result is consistent with that reported earlier for PgC4Ga and PgC4GaZn in CD3CN.[12] The peak at 0 ppm produced a carbon counterpart (29 ppm) in the HMQC. This observation indicates that the encapulated molecule is either acetone or ethanol (some ethanol was present during sample preparation), but not water (supporting information).

PgC4Ga has a diffusion coefficient in d6-acetone of 5.37×10−10 m2/sec, which remains essentially unchanged even after 7 days (5.33×10−10 m2/sec). The corresponding diffusion coefficients for PgC4GaZn and PgC4 are 5.07×10−10 m2/sec and 8.65×10−10 m2/sec, respectively. Furthermore, the diffusion coefficient for the entrapped small molecule is the same as that of the host PgC4GaZn toroid. These diffusion coefficients are similar in magnitude to those found by Cohen and coworkers for hydrogen-bonded resorcin[4]arene and pyrogallol[4]arene hexamers in chloroform.[24]

The 71Ga NMR for the PgC4Ga or PgC4GaZn filtrate in d6-acetone shows a sharp peak from free gallium. In contrast, the 71Ga NMR for the crystalline hexamers dissolved in d6-acetone at both 27°C and −70°C reveals no recognizable signal, which indicates the absence of free gallium in solution (Figure 3). Overnight 71Ga NMR on both PgC4Ga and PgC4GaZn in d6-acetone at room temperature produced no free gallium signal.

Figure 3.

71Ga NMR of (a) PgC4Ga crystals in d6-acetone at −70°C and (b) PgC4Ga crystals in d6-acetone at 27°C shows no signal for free gallium; (c) supernatant of PgC4Ga at 27°C shows a free gallium peak in d6-acetone. (The broad humps in the baseline in (a) and (b) are due to the probe's background).

Overall, these experiments provide evidence for not only the presence of gallium in the self-assembled toroidal frameworks but also the stability of the frameworks. The experiments also demonstrate that the PgC4GaZn toroids comprise solvent as well as metal and that the guest solvent remains encapsulated over time.

Combining the above SANS and NMR data and assuming the same metal content as observed from XRD and PGAA, we propose the following structural details for the solution-phase toroidal assemblies. Calulating the shell volume using equation 1 yields a Vshell of ≈5600 Å3 for the PgC4Ga toroidal assembly and ≈7000 Å3 for the PgC4GaZn assembly.

| (1) |

Both XRD and SANS measurements reveal the dimensions of ca. 14 × 7 Å for a typical PgCn (n = 1–4) bowl. The 7 Å length is the distance between the centroid of the linker carbons at the lower rim and the centroid of the oxygens at the upper rim. The 14 Å diameter is the distance between opposing oxygens at the upper rim. Thus, the difference of ≈1400 Å3 in Vshell corresponds to the volume of 2 bowls of PgC4. Assuming that the toroidal assemblies consist of only PgC4 bowls, the individual shell volumes are consistent with 7 bowls in PgC4Ga and 9 bowls in PgC4GaZn.

The shorter axis of the PgC4 bowl corresponds to the height of the PgC4Ga toroid while the longer axis of the bowl corresponds to the height of the PgC4GaZn toroid. This observation suggests a possible difference in the orientation of the PgC4 macrocyles in the two toroidal assemblies, with the upper and lower rims of the macrocyles aligned with the upper and lower rims of the PgC4Ga toroid but perpendicular to the upper and lower rims of the PgC4GaZn toroid.

The suggested structure of the PgC4Ga toroid has the 7 arenes in a boat conformation providing possible coordination sites for the 14 gallium ions between the flat pyrogallols on adjacent arenes and between opposite pyrogallols on the same arene. The sideways orientation of the 9 cone-shaped macrocyles in the PgC4GaZn assembly allows guest encapsulation and provides sufficient coordination sites between adjacent arenes for the 24 metals that stitch the toroidal assembly (Figure 4). Among other possible interactions, the assemblies may also be stabilized by hydrogen-bonding between the pyrogallol hydroxyl groups and solvent and by coordinate covalent bonds between the metal and solvent.

Figure 4.

Top: Top view of the suggested arrangement of pyrogallol[4]arenes in PgC4GaZn (left) and PgC4Ga (right) nanoassemblies in acetone. Bottom: Top view of the suggested metal coordination sites in the PgC4Ga toroidal framework in acetone.

The proposed metal coordination sites lead to at least three different environments for the pyrogallol -CH protons and two different environments for the linker group protons, as observed in the 1H NMR. For example, focusing on the PgC4Ga assemblies, because gallium interacts with only two of the three hydroxyl groups of a given pyrogallol, all four of the aryl protons of a given arene are non-equivalent (Figure 4, bottom). The (at least) two different types of protons on the linker carbons arise for the same reason. If both gallium and zinc metals are present in the framework of the PgC4GaZn assembly, as suggested by the difference in the toroidal dimensions, the more complicated multiple proton environments would be expected.

The results of the SANS, NMR and PGAA studies conducted in this work are intriguing because they demonstrate that PgC4Ga nanoassemblies are distinctive in five ways: (1) the toroidal structure of the PgC4Ga and PgC4GaZn assemblies is different from the spherical structure of other PgCnM (M = Cu, n = 3–13; M = Ni, n = 3) assemblies[25] in the solution phase; (2) the rugby ball structure of the PgC4Ga hexamer is different from the spherical structures of the PgC3M (M = Cu, Ni) hexamers[13] in the solid state; (3) the structure of PgC4Ga is different from that of PgC4GaZn in the solid and solution phases; (4) guest encapsulation is not observed for the PgC4Ga toroid in solution ; (5) the Ga+3:M+2 ratio in the PgC4GaM hexamers varies with M, decreasing from Co+2 to Zn+2. That is, the SANS measurements reveal the first structural change from the solid state to the solution phase, the NMR results reveal structural details unique to each toroid, and the PGAA measurements reveal the trend among the late 3d transition metals in directing the formation of mixed metal-seamed pyrogallol[4]arene nanoassemblies. Overall, the cohesive SANS and NMR experiments provide important insights into the solution-phase behavior of gallium-seamed C-butylpyrogallol[4]arene nanoassemblies.

Future studies will continue to address the ways in which non-covalent interactions and metal ions govern the self-assembly process of bi- and tri-metallic gallium-seamed nanoassemblies. In particular, combined solution-phase and computation studies will be performed to obtain more insight into the mechanism of formation of and metal ion positions in gallium-seamed scaffolds.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

We thank NSF for support of this work (J.L.A). This work utilized facilities supported in part by the National Science Foundation under Agreement No. DMR-0944772 (S.R.K.), NSF grant CHE-89-08304, NIH/NCRR S10 RR022341-01 (Cold probe) for NMR. Certain trade names and company products are identified to adequately specify the experimental procedure. In no case does such identification imply recommendation or endorsement by the National Institute of Standards and Technology, nor does it imply that the products are necessarily best for the purpose.

References

- [1].Buenzli JCG, Choppin GR, editors. Lanthanide Probes in Life, Chemical and Earth Sciences: Theory and Practice. 1989. p. 432. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Cao X, Liang Y. Mater. Lett. 2009;63:2215–2217. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Evans CW, Raston CL, Iyer KS. Green Chem. 2010;12:1175–1179. [Google Scholar]

- [4].McKinlay RM, Cave GWV, Atwood JL. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2005;102:5944–5948. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408113102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Power NP, Dalgarno SJ, Atwood JL. New J. Chem. 2007;31:17–20. [Google Scholar]

- [6].(a) Mugridge JS, Bergman RG, Raymond KN. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:2057–2066. doi: 10.1021/ja2067324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Caulder DL, Powers RE, Parac TN, Raymond KN. Angew. Chemie. Int. Ed. 1998;37:1840–1843. [Google Scholar]

- [7].Kolesnikov NN, Kveder VV, Borisenko DN, Borisenko EB, Timonina AV, Bozhko SI. Method of gallium nano-particles production using pulse crystn. 2008;2336371 [Google Scholar]

- [8].Kang JW, Hwang HJ. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2004;31:237–246. [Google Scholar]

- [9].Seo HW, Bae SY, Park J. Mater. Res. Soc. Symp. Proc. 2004;789:285–290. [Google Scholar]

- [10].McKinlay RM, Thallapally PK, Cave GWV, Atwood JL. Angew. Chem. 2005;44:5733–5736. doi: 10.1002/anie.200501491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].(a) Jin P, Dalgarno SJ, Atwood JL. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2010;254:1760–1768. [Google Scholar]; (b) Dalgarno SJ, Power NP, Atwood JL. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2008;252:825–841. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Jin P. Synthesis of Mixed Metal-organic Pyrogallol[4]arene Nanocapsules and their Host-guest Chemistry. Ph.D. Thesis. University of Missouri-Columbia; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- [13].Kumari H, Mossine AV, Kline SR, Dennis CL, Fowler DA, Barnes CL, Teat SJ, Deakyne CA, Atwood JL. Angew. Chem. 2011 doi: 10.1002/anie.201107182. In press. DOI: anie.201107182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Paul RL, Lindstrom RM, Heald AE. J. Radioanal. and Nuc. Chem. 1997;215:63–68. [Google Scholar]

- [15].Glinka CJ, Barker JG, Hammouda B, Krueger S, Moyer JJ, Orts WJ. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 1998;31:430–445. [Google Scholar]

- [16].Kline SR. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2006;39:895–900. [Google Scholar]

- [17].(a) Schulz GV. Z. physik. Chem. 1939;B43:25–46. [Google Scholar]; (b) Kotlarchyk M, Chen SH. J. Chem. Phys. 1983;79:2461–2469. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Atwood JL, Brechin EK, Dalgarno SJ, Inglis R, Jones LF, Mossine A, Paterson MJ, Power NP, Teat SJ. Chem. Commun. 2010;46:3484–3486. doi: 10.1039/c002247k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Svergun DI, Feigin LA. X-ray and Neutron Low-Angle Scattering. 1986:278. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Schulz GV. Z. physik. Chem. 1935;B30:379–398. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Bartlett P, Ottewill RH. J. Chem. Phys. 1992;96:3306–3318. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Berr SS. J. Phys. Chem. 1987;91:4760–4765. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Percec V, Wilson DA, Leowanawat P, Wilson CJ, Hughes AD, Kaucher MS, Hammer DA, Levine DH, Kim AJ, Bates FS, Davis KP, Lodge TP, Klein ML, DeVane RH, Aqad E, Rosen BM, Argintaru AO, Sienkowska MJ, Rissanen K, Nummelin S, Ropponen J. Science. 2010;328:1009–1014. doi: 10.1126/science.1185547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].(a) Avram L, Cohen Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:15148–15149. doi: 10.1021/ja0272686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Avram L, Cohen Y. Org. Lett. 2003;5:3329–3332. doi: 10.1021/ol035211y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].(a) Kumari H, Kline SR, Schuster NJ, Atwood JL. Chem. Commun. 2011;47:12298. doi: 10.1039/c1cc15615b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Kumari H, Kline SR, Schuster NJ, Barnes CL, Atwood JL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:18102–18105. doi: 10.1021/ja208195t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.