Abstract

To study the gastrointestinal survival and enterotoxin production of the food-borne pathogen Bacillus cereus, an in vitro simulation experiment was developed to mimic gastrointestinal passage in 5 phases: (i) the mouth, (ii) the stomach, with gradual pH decrease and fractional emptying, (iii) the duodenum, with high concentrations of bile and digestive enzymes, (iv) dialysis to ensure bile reabsorption, and (v) the ileum, with competing human intestinal bacteria. Four different B. cereus strains were cultivated and sporulated in mashed potato medium to obtain an inoculum of 7.0 log spores/ml. The spores showed survival and germination during the in vitro simulation of gastrointestinal passage, but vegetative outgrowth of the spores was suppressed by the intestinal bacteria during the final ileum phase. No bacterial proliferation or enterotoxin production was observed, despite the high inoculum levels. Little strain variability was observed: except for the psychrotrophic food isolate, the spores of all strains survived well throughout the gastrointestinal passage. The in vitro simulation experiments investigated the survival and enterotoxin production of B. cereus in the gastrointestinal lumen. The results obtained support the hypothesis that localized interaction of B. cereus with the host's epithelium is required for diarrheal food poisoning.

INTRODUCTION

According to the current hypothesis, B. cereus diarrheal food poisoning is caused by destruction of epithelial cells in the small intestine due to enterotoxin production by vegetative cells (16, 44). Those B. cereus cells originate from ingested vegetative cells that survive gastric passage and/or from ingested spores which germinate in the small intestine. During vegetative growth, B. cereus produces various enterotoxins and virulence factors implicated in diarrheal food poisoning, such as nonhemolytic enterotoxin (Nhe), hemolysin BL (Hbl), cytotoxin K (CytK), enterotoxin FM (entFM), phospholipases C, hemolysins, collagenases, and cereolysins (6). The Nhe, Hbl, and CytK toxins possess hemolytic and cytotoxic activity due to pore formation in the cell membrane (4, 14, 19, 25). Phospholipases C damage human epithelial cells and the subepithelial matrix and also cause hemolysis by enzymatic degradation of the cell membrane (15, 41). The enterotoxin EntFM, hemolysins, and degradative enzymes are not directly cytotoxic, but they contribute to the cytotoxic and hemolytic activity of B. cereus and its adhesion to epithelial cells (2, 3, 26, 37).

In vitro experiments that simulate the physicochemical conditions, enzymatic digestive activity, and microbiological interactions in the gastrointestinal tract were developed (29, 30, 32). These in vitro simulations enable, among other things, the study of the bioaccessibility of food contaminants and of the effects of pre- and probiotics on the gastrointestinal microbiota (17, 39, 40). Although host interactions are excluded, these in vitro experiments can provide valuable information regarding the survival of probiotic bacteria in different formulations during gastrointestinal passage (27, 34). Similarly, in vitro experiments were used to assess the survival and behavior of food pathogens in the gastrointestinal lumen of the host after ingestion. For example, successive batch incubation of B. cereus spores in gastric and intestinal simulation media at 37°C showed germination and growth for the majority of the strains tested (43). However, this previous study did not assess enterotoxin production. Other batch incubation studies with B. cereus under gastrointestinal conditions revealed important influence of the added food type and the bile concentration on the growth and survival of B. cereus (10, 11). In contrast to the average gastric conditions simulated in batch incubation, the in vivo gastric pH and residence time are highly variable parameters (7, 9, 13). Similarly, digestive secretions in the proximal small intestine result in initially high bile and enzyme concentrations in the duodenum, followed by very low concentrations in the ileum due to removal and reabsorption (33). These aspects were included in the current study by developing a dynamic in vitro simulation experiment by continuous addition of acid and fractional emptying of the gastric vessel and dialysis of the intestinal vessel. Moreover, competition with intestinal microbiota was included during the ileum phase after dialysis, since the indigenous microbial community has been shown to affect the intestinal survival of B. cereus (8).

The aim of the present study was to investigate the survival and intestinal enterotoxin production of B. cereus spores produced in mashed potato medium during dynamic in vitro simulation of gastrointestinal passage with exclusion of host signals and influences.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacillus cereus strains, cultivation, and enumeration.

The Bacillus cereus strains (Table 1) were cultivated in tryptone soya broth (TSB; Oxoid) for 24 h at 30°C and subcultured before inoculation in mashed potato medium. The mashed potato medium was a mixture (50:50, wt/wt) of food solution (Table 2) and mashed potato flakes (Mousline classic; Maggi) reconstituted with whole milk according to the manufacturer's recipe. Approximately 3 log CFU/ml vegetative B. cereus cells of the subculture were inoculated in 83 ml mashed potato medium in stomacher bags and incubated for 1 to 2 weeks at 30°C until 7 to 8 log spores/ml were produced, under conditions depending on the strain. The day before the simulation experiment, the spore concentration was adjusted to 7.0 log spores/ml with fresh mashed potato medium and this spore inoculum was stored at 2°C until use. Total B. cereus concentrations were determined by plating the appropriate dilutions in physiological peptone salt solution (PPS; 8.5 g/liter NaCl [Fluka] and 1 g/liter neutralized bacteriological peptone [Oxoid]) on tryptone soya agar (TSA). Spore concentrations were determined by plating on TSA after heating samples for 10 min at 80°C. In the presence of intestinal bacteria, i.e., during the ileum phase of the gastrointestinal simulation experiment, total B. cereus numbers were monitored by quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR), because plate count enumeration was no longer possible due to overgrowth of the plates by the intestinal bacteria (5).

Table 1.

Origin and characteristics of the Bacillus cereus strains used in this study

| B. cereus straina | Origin | Minimum growth temp (°C) | Production ofb: |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hbl |

Nhe |

|||||

| BCET-RPLAb | Duopath | Duopath | VIA-BDE | |||

| NVH 1230-88 | Clinical (human feces) | 8 | + | + | + | + |

| RIVM 9903295-4 | Clinical (human feces) | 7 | + | − | + | + |

| LFMFP 381 | Food (dried potato flakes) | >10 | + | − | + | − |

| LFMFP 710 | Food (mashed potatoes) | 7 | + | + | + | + |

NVH, Norwegian School of Veterinary Science, Oslo, Norway; RIVM, National Institute for Public Health and Environment, Bilthoven, the Netherlands; LFMFP, Laboratory of Food Microbiology and Food Preservation, Ghent University, Ghent, Belgium.

BCET-RPLA, Bacillus cereus enterotoxin reversed passive latex agglutination (Oxoid); Duopath, Duopath cereus enterotoxins (Merck); VIA-BDE, Bacillus diarrheal enterotoxin visual immunoassay (3M Tecra).

Table 2.

Composition of the simulation media for food, saliva, gastric secretion, intestinal secretion, and dialysis

| Compound (source) | Concn (g/liter) ina: |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Food solution | Saliva medium | Gastric medium | Intestinal medium | Dialysis medium | |

| Salts | 2.80 | 4.15 | 4.32 | 12.89 | 8.41 |

| NaCl | 2.80 | 0.30 | 2.75 | 6.43 | 8.41 |

| NaH2PO4 · 2H2O | — | 1.15 | 0.35 | — | — |

| KCl | — | 0.90 | 0.82 | 0.50 | — |

| NH4Cl | — | 0.31 | — | — | — |

| KSCN | — | 0.20 | — | — | — |

| Na2SO4 · 10H2O | — | 1.29 | — | — | — |

| CaCl2 · 2H2O | — | — | 0.40 | 0.21 | — |

| KH2PO4 | — | — | — | 0.05 | — |

| MgCl2 · 6H2O | — | — | — | 0.03 | — |

| NaHCO3 | — | — | — | 5.67 | — |

| Nutrients | 10.50 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Arabinogalactan (from larch wood; Sigma-Aldrich) | 2.00 | — | — | — | — |

| Pectin (from apples; Sigma-Aldrich) | 2.00 | — | — | — | — |

| Xylan (from birch wood; Sigma-Aldrich) | 2.00 | — | — | — | — |

| Yeast extract (Oxoid) | 3.00 | — | — | — | — |

| Proteose peptone (Oxoid) | 0.50 | — | — | — | — |

| Cysteine (nonanimal source; Sigma-Aldrich) | 1.00 | — | — | — | — |

| Host factors | 0.00 | 0.99 | 10.19 | 18.42 | 1.13 |

| Amylase (α-amylase from Bacillus sp.; Sigma-Aldrich) | — | 0.73 | — | — | — |

| Mucin (from porcine stomach type II; Sigma-Aldrich) | — | 0.05 | 3.00 | — | — |

| Urea (Sigma-Aldrich) | — | 0.20 | 0.09 | 0.15 | — |

| Uric acid (Sigma-Aldrich) | — | 0.02 | — | — | — |

| d-Glucuronic acid (Fluka) | — | — | 0.02 | — | — |

| d-(+)-Glucosamine hydrochloride (Sigma-Aldrich) | — | — | 0.33 | — | — |

| Bovine serum albumin (fraction V; Merck) | — | — | 2.25 | 1.27 | 1.13 |

| Pepsin (from porcine stomach mucosa; Sigma-Aldrich) | — | — | 4.50 | — | — |

| Pancreatin (from porcine pancreas; Sigma-Aldrich) | — | — | — | 6.00 | — |

| Lipase (from porcine pancreas; Sigma-Aldrich) | — | — | — | 1.00 | — |

| Bile (oxgall, dehydrated fresh bile; Difco) | — | — | — | 10.00 | — |

—, the compound was not added to the medium.

Simulation media.

The composition of the simulation media was based on the media from the RIVM (National Institute for Public Health and Environment, the Netherlands) in vitro digestion model representing the fed state (18) and the Simulator of the Human Intestinal Microbial Ecosystem (SHIME) reactor feed (35). The composition of all simulation media is presented in Table 2. The volume ratio of the food/saliva/gastric/intestinal simulation medium was 1.5:1:2:4.5.

Gastrointestinal simulation experiments.

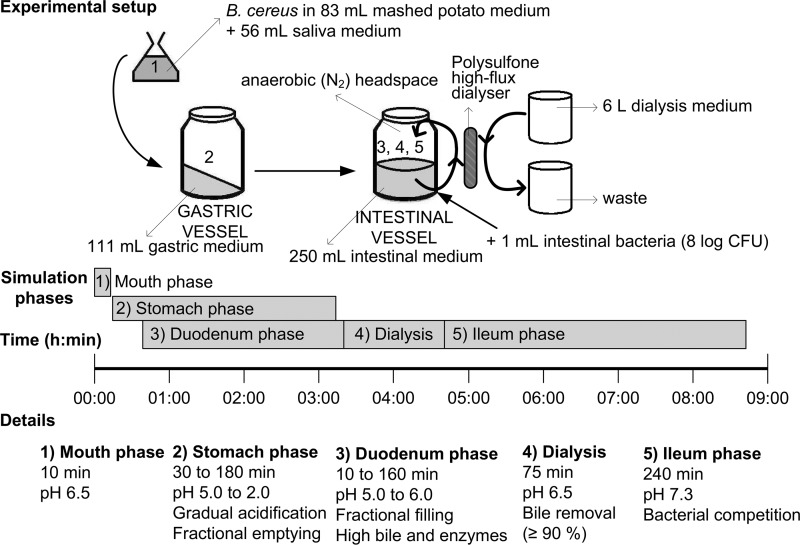

The gastrointestinal simulation experiment comprised five phases: the mouth, the stomach, the duodenum, dialysis, and the ileum (Fig. 1). The stomach phase took place in the gastric vessel, while the duodenum phase, dialysis, and the ileum phase all occurred subsequently in the intestinal vessel. The gastric and intestinal vessels were two SHIME reactor vessels, i.e., double-jacketed glass vessels of 1 liter kept at 37°C with continuous stirring. The headspace of the gastric vessel consisted of normal atmospheric air, but the intestinal vessel with the intestinal simulation medium was flushed for 30 min with pure nitrogen gas to obtain anaerobic conditions. The experiments were performed in triplicate with different B. cereus inocula on different days.

Fig 1.

Setup of the gastrointestinal simulation experiment and details of its five phases.

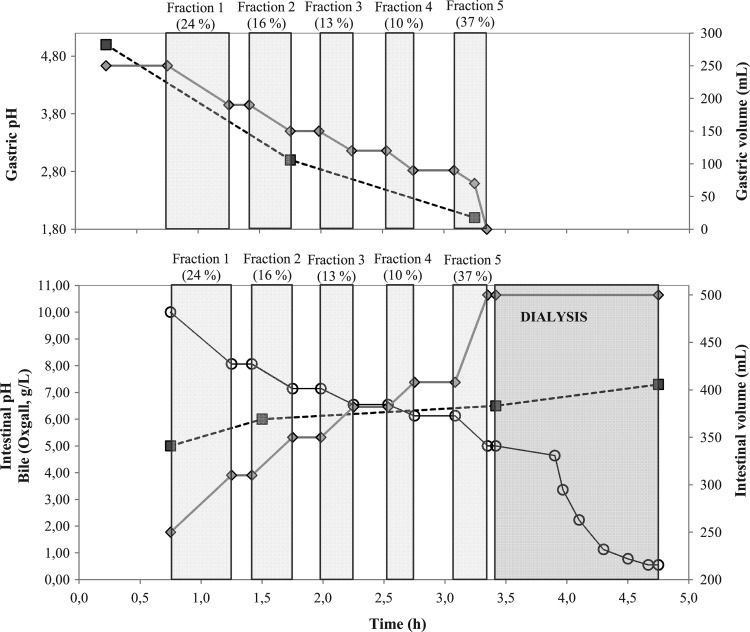

The B. cereus inoculum was produced in the mashed potato medium (see above). The mouth phase consisted of mixing the mashed potato medium containing the spores (83 ml containing 7.0 log spores/ml) with 56 ml saliva medium (37°C, pH 6.5) by stomaching for 1 min (Stomacher 400 laboratory paddle blender; Seward). At the beginning of the stomach phase, the pH in the gastric vessel was manually set at exactly 5.00 (±0.02). Then, the pH was decreased from 5.0 to 3.0 during the first 90 min by automated continuous addition of acid (0.18 M HCl) at 0.2 ml/min (Masterflex L/S economy digital drive with 0.51-mm tubing [PharMed BPT tubing; Saint-Gobain Performance Plastics]) and at 0.1 ml/min during the last 90 min to reach pH 2.0. Gastric emptying was initiated 30 min after the start of the gastric phase by discontinuous pumping (2 ml/min, Masterflex L/S economy digital drive). The contents of the gastric vessel were transferred to the intestinal vessel in 5 fractions (indicated as gray areas in Fig. 2) by discontinuous pumping in such a way that approximately 25% of the gastric content was removed after 1 h, 50% after 2 h, and 75% after 3 h. The fractional gastric emptying resulted in a 150-min overlap between the stomach and duodenum phase in which the B. cereus inoculum was divided into subpopulations which were subjected to various different incubation times in the stomach phase (minimum 30 min, maximum 180 min) and duodenum phase (minimum 10 min, maximum 160 min). The duodenal pH fluctuates randomly between 5.0 and 6.0 in healthy people who have consumed a solid meal (13). Therefore, the pH in the intestinal vessel was automatically adjusted by a pH controller (FerMac 260; Electrolab) to remain at pH 5.0 during the first 45 min and at pH 6.0 during the last 115 min of the duodenum phase, at pH 6.5 during the dialysis, and at pH 7.3 during the ileum phase. An overview of the dynamically changing parameters during the stomach and duodenum phase and the dialysis is presented in Fig. 2.

Fig 2.

(Top) pH (■) and volume (224) in the gastric vessel, which was gradually emptied, resulting in 5 gastric fractions (indicated as light gray areas); (bottom) pH (■), volume (224), and bile concentration (○) in the intestinal vessel, which was gradually supplied with the gastric content in 5 fractions. After complete transfer of the gastric vessel's content, dialysis was performed (indicated as dark gray area) to reduce the bile levels to ≤90% of the initial concentration.

The consumption of food induces bile secretion in the small intestine in the range of 7 to 15 mM bile salts, which corresponds to 5 to 10 g/liter bile (18, 29, 33). Dialysis to ensure ≥90% (wt/vol) bile removal (from 5 g/liter to ≤0.5 g/liter) was performed by repeated filtration of the duodenal content with a Diacap polysulfone high-flux dialyzer (Diacap HiFlo18; B. Braun) during 75 min at 40 ml/min with fresh dialysis medium in counterflow at 80 ml/min (Masterflex L/S economy digital drive). The quantification of the bile concentration in intestinal medium was done by measuring the optical density at 350 nm (OD350) (VersaMax Absorbance Microplate Reader; Molecular Devices) of 300-μl samples. The OD350 values were converted to bile concentrations with the linear standard curve (R2 = 0.997) generated by a dilution series of bile (0.5 to 10.0 g/liter oxgall; Difco) in intestinal medium. The lower limit of this bile quantification method was 0.5 g/liter bile (results not shown).

After the dialysis, the ileum phase (4 h) was started by the addition of 1 ml human intestinal bacteria (8 log CFU/ml) obtained from the colon ascendens vessel of a SHIME reactor, started up with fecal material of a healthy 27-year-old male, fed with standard reactor feed, and kept under the standard reactor conditions (32, 35). In the human ileum, the resident microbiota originates from bacteria in the ingested food and cecal reflux (45). Therefore, the intestinal bacteria used to simulate competition in the ileum were taken from the colon ascendens vessel from SHIME to simulate reflux inoculation. According to PCR-denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis and metabolite analysis, the SHIME contains stable bacterial communities which resemble the human microbiota of the colon in its composition of bacterial numbers and species (35). The exact composition of the intestinal microbiota depends on both host-specific characteristics and diet. It was previously shown that differences in SHIME reactor feed (simulating different diets) affected the kinetics of competition of B. cereus with the intestinal microbiota and, thus, its survival within the intestinal community (8). During these experiments, the variation in the intestinal bacterial community was minimized by using colon ascendens bacteria from the same SHIME reactor maintained under standard conditions with the standard feed. This allows the comparison of the intestinal survival of the different B. cereus strains relative to each other. The growth of the intestinal bacteria during the ileum phase in the absence of B. cereus was monitored by plating. Total (facultative) aerobic bacteria, staphylococci, total coliforms, enterococci, and total anaerobes were counted according to Possemiers et al. (35). Fecal lactobacilli, clostridia, and bifidobacteria were determined on LamVab agar (20), tryptose sulfite cycloserine (TSC) agar (Merck), and raffinose-Bifidobacterium agar (RB) (21) with 1% (wt/vol) bromocresol purple (Merck), respectively.

Toxin production.

The intestinal production of enterotoxins by B. cereus was assessed hourly during the ileum phase by testing 1-ml samples (after filtration with 0.2-μm syringe filters; Whatman) with the Duopath cereus enterotoxins test (Merck) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The detection limits of the Duopath kit are not provided by the manufacturer, but they have been estimated at 6 ng/ml for Nhe-B and 20 ng/ml Hbl-L2 (23).

RESULTS

Gastrointestinal simulation experiments with B. cereus spores.

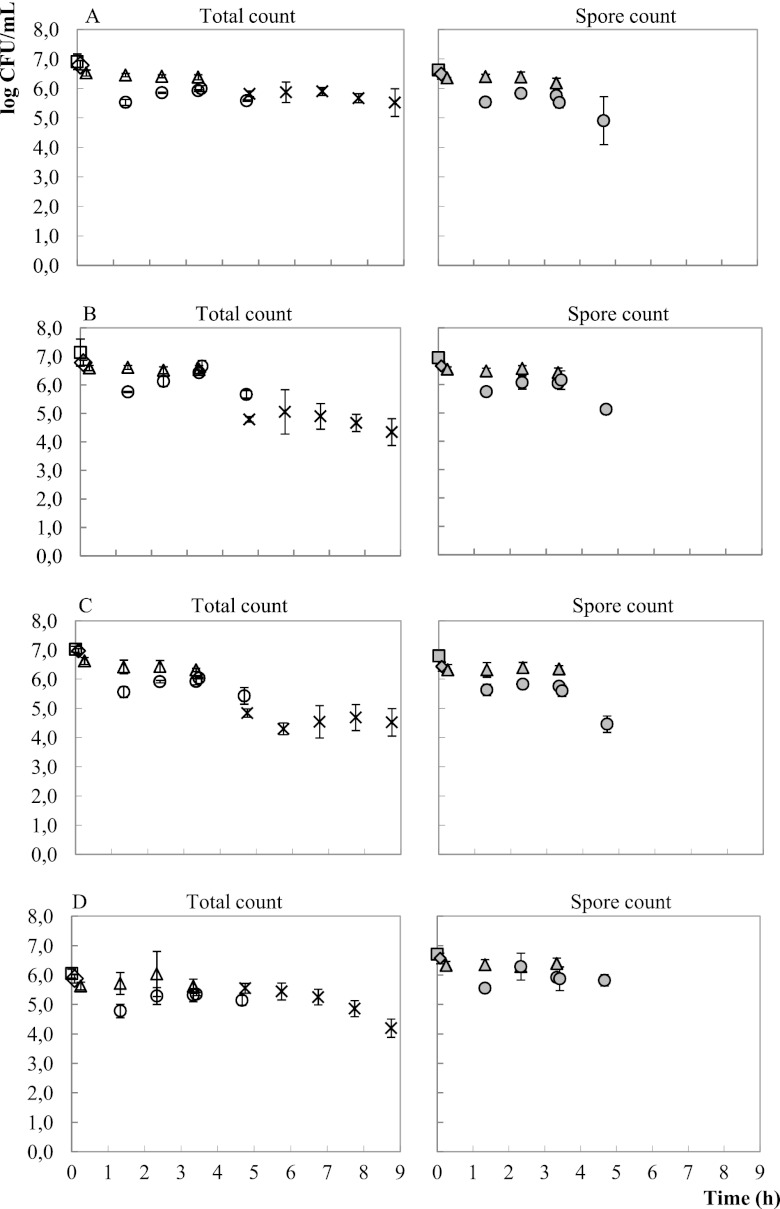

Mashed potato medium containing 7.0 log spores/ml was subjected to in vitro simulation of the gastrointestinal passage. The spores of all B. cereus strains (Table 1) were unaffected by the mouth, stomach, and duodenum phases, during which the entire population remained viable without germinating (Fig. 3). The slight increase of total and spore counts during the duodenum phase was solely the consequence of the gradual transfer of the gastric content to the intestinal vessel (Fig. 2). At the end of the duodenum phase and during the dialysis, the spore germination had started, noticeable as the decreasing spore percentage of the B. cereus population during those phases (Table 3). Subsequently, the competing intestinal bacteria were added to the intestinal vessel at the final concentration of 5.5 log CFU/ml. During the ileum phase, plating on MYP (1a, 22a) was no longer possible for B. cereus discrimination from the ileal bacteria, so qPCR was applied (5). This analysis revealed stable DNA levels of all B. cereus strains, except for the psychrotrophic food isolate B. cereus LFMFP 710. These results suggest spore survival, but further germination to vegetative cells without outgrowth or slight inactivation of the spores cannot be ruled out, since these scenarios all occur under stable DNA concentrations. The concentration of B. cereus LFMFP 710 decreased more than 10-fold during the 4-h ileum phase, namely, −1.36 log copy numbers/ml. This indicates inactivation of this strain followed by DNA degradation. In comparison, the concentrations of the other strains decreased only slightly, by 0.30 and 0.32 log copy numbers/ml for mesophilic strains B. cereus NVH 1230-88 and B. cereus RIVM 9903295-4, respectively, and by 0.45 log copy numbers/ml for the diarrheal psychrotrophic strain B. cereus LFMFP 381. As a general feature, the psychrotrophic food isolate B. cereus LFMFP 710 consistently showed lower total counts than spore counts (Table 3). This suggests that the spores of this strain required the heat treatment prior to the spore count to ensure outgrowth of all spores on the plates, resulting in lower CFU numbers in the total counts due to the lack of outgrowth of non-heat-activated spores.

Fig 3.

The survival of B. cereus spores during the gastrointestinal simulation experiment with B. cereus NVH 1230-88 (A), B. cereus RIVM 9903295-4 (B), B. cereus LFMFP 381 (C), and B. cereus LFMFP 710 (D); open symbols indicate the total count and filled symbols the spore count in mashed potato medium (◽), mouth phase (224), stomach phase (△), and duodenum phase and dialysis (○), and qPCR enumeration during the ileum phase is shown (×); the average values and standard deviations of triplicate experiments are presented.

Table 3.

Bacillus cereus spore populations during the gastrointestinal simulation experiments

| Sample | Time (h) | Proportion of spores [% of total population (±SD)] of B. cereus straina |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NVH 1230-88 | RIVM 9903295-4 | LFMFP 381 | LFMFP 710 | LFMFP 381 without competition | ||

| Mashed potato medium | 0.0 | 60 (±37) | 89 (±71) | 64 (±35) | 458 (±90) | 125 (±113) |

| Mouth phase | 0.1 | 50 (±37) | 75 (±7) | 30 (±10) | 504 (±173) | 73 (±20) |

| Stomach phase | 0.3 | 81 (±47) | 91 (±30) | 51 (±17) | 500 (±104) | 85 (±65) |

| Stomach phase | 1.3 | 48 (±36) | 73 (±7) | 83 (±27) | 452 (±194) | 102 (±63) |

| Stomach phase | 2.3 | 75 (±45) | 115 (±26) | 94 (±26) | 285 (±226) | 90 (±29) |

| Stomach phase | 3.3 | 61 (±37) | 77 (±19) | 108 (±18) | 586 (±66) | 85 (±33) |

| Duodenum phase | 1.3 | 66 (±41) | 99 (±21) | 119 (±17) | 622 (±248) | 91 (±86) |

| Duodenum phase | 2.3 | 60 (±32) | 91 (±26) | 83 (±3) | 2,496 (±3,642) | 82 (±56) |

| Duodenum phase | 3.3 | 28 (±16) | 43 (±12) | 69 (±7) | 411 (±242) | NA |

| Dialysis | 3.4 | 30 (±18) | 33 (±11) | 40 (±21) | 403 (±245) | 36 (±22) |

| Dialysis | 4.7 | 19 (±12) | 29 (±5) | 13 (±8) | 599 (±513) | NA |

| Ileum phase | 4.8 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 54 (±32) |

| Ileum phase | 5.8 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 20 (±21) |

| Ileum phase | 6.8 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 5 (± 5) |

| Ileum phase | 7.8 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 2 (± 3) |

| Ileum phase | 8.8 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 2 (± 3) |

The Bacillus cereus spore populations of the indicated strains during the gastrointestinal simulation experiments, determined by plating on TSA with and without prior heat treatment (10 min at 80°C), are expressed as the percentage of the total B. cereus count. NA, not applicable because the spore percentage cannot be calculated from the available data.

When no competing intestinal bacteria were added during the ileum phase, the germination of B. cereus spores was followed by vegetative outgrowth to approximately 7.0 log CFU/ml (Fig. 4). The remaining spore concentration during the ileum phase was constant throughout any one experiment but highly variable among the four replicate experiments, namely, 4.5 log spores/ml, 5.5 log spores/ml, 3.8 log spores/ml, and none detected (<1.0 log spores/ml). Although large variations in germination were observed, ranging from 94% to 100% of the population, germination was always followed by significant outgrowth of the vegetative cells, to approximately 7.0 log CFU/ml. Therefore, the lack of vegetative outgrowth in the presence of human intestinal bacteria (Fig. 3) can be attributed to competition and/or inhibition of the indigenous microbiota.

Fig 4.

Survival of B. cereus LFMFP 381 spores during the gastrointestinal simulation experiment without the addition of intestinal bacteria during the ileum phase; open symbols indicate the total count and filled symbols the spore count in mashed potato medium (◽), mouth phase (224), stomach phase (△), and duodenum phase, dialysis, and ileum phase (○); the average values and standard deviations of quadruple experiments are presented.

No enterotoxins (Nhe nor Hbl) were detected during the ileum phase of any of the simulation experiments (Fig. 3 and 4), even when approximately 7 log CFU/ml growing vegetative cells were present in the absence of competing bacteria.

Dialysis.

To mimic the approximately 95% bile salt reabsorption in the human ileum (33), dialysis was performed between the duodenum and the ileum phase. At the beginning of the duodenum phase, the pure intestinal medium contained the maximal bile concentration of 10 g/liter oxgall, corresponding to approximately 15 mM bile salts (27), which gradually decreased to 5 g/liter due to dilution with the contents of the gastric vessel (Fig. 2). Dialysis of intestinal medium containing 5 g/liter and 10 g/liter bile showed that 90% and 95% of the bile was removed after 60 and 80 min, respectively (results not shown).

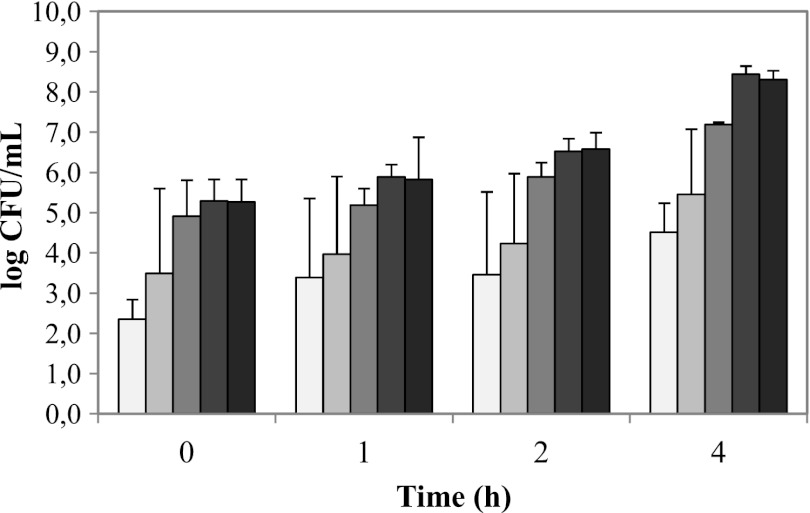

Intestinal bacteria.

At the start of the ileum phase, 5.5 log CFU/ml human intestinal bacteria were added to simulate competition of B. cereus with the indigenous intestinal microbiota. These bacteria proliferated to approximately 8 log CFU/ml at the end of the ileum phase, with their relative abundances being preserved (Fig. 5).

Fig 5.

Survival and growth of human intestinal bacteria during ileum phase conditions, determined by plate count enumeration of enterococci (very light gray), clostridia (light gray), staphylococci (medium gray), coliforms (medium-dark gray), and total (facultative) anaerobes (dark gray); the average values and standard deviations of duplicate experiments are presented.

DISCUSSION

B. cereus spores survived throughout the simulation of gastrointestinal passage. Realistic but worst-case conditions were selected for the gastrointestinal simulation experiment, namely, the high inoculum concentration of 7 log spores/ml and the slow kinetics of gastric acidification (from pH 5.0 to 2.0 over 3 h). However, the gastric acidification profile was previously shown to affect only vegetative B. cereus cells, since the spores were fully resistant to pH values between 5.0 and 2.0 (7). The food source was highly contaminated with 7.0 log spores/ml, which corresponds with a total infective dose of 8.9 log spores. This is far more than the currently postulated infective dose of 5 to 8 log viable B. cereus for diarrheal food poisoning (16). It was previously hypothesized that B. cereus-induced diarrhea is caused by enterotoxin production in close proximity to the intestinal epithelium cells (16, 44). This study reinforces this hypothesis by showing that no B. cereus proliferation and toxin production occurred in the intestinal lumen during in vitro gastrointestinal passage of mashed potatoes heavily contaminated with B. cereus spores.

No toxin production by any of the strains was detected during the ileum phase, even when high concentrations (approximately 7 log CFU/ml) of growing vegetative cells were present. However, the lack of detection of enterotoxin does not necessarily mean that toxin production did not occur, because the enterotoxins are very susceptible to degradation by the digestive host enzymes. These enzymes were added in high concentrations to the simulation media to mimic the fed state of the host. It is possible that these host digestive enzymes were partially removed during the dialysis for bile removal, since the sizes of the enzymes fall in the range of the cutoff value of 10 to 60 kDa of the polysulfone membrane (personal communication with the product manager of Vedefar NV; also UniProt database, 4 February 2012). However, dialysis was performed to remove approximately 95% of the much smaller conjugated bile acids (approximately 0.5 kDa), so the majority of the digestive proteases was presumably still present in the simulation broth after dialysis.

The indigenous microbiota prevented B. cereus outgrowth during the ileum phase, so this study shows inhibition of pathogen outgrowth by the intestinal bacterial community during in vitro simulation of gastrointestinal passage. It was already known that the indigenous intestinal microbiota plays an important role in the maintenance of gastrointestinal homeostasis and the host's intestinal health (47). Commensal and probiotic intestinal bacteria are frequently reported to play a protective role against enteric disease by several mechanisms, including competitive exclusion and the production of antimicrobial compounds. For example, preincubation of epithelium cells with probiotic Lactobacillus strains could reduce Campylobacter jejuni infection, depending on the specific combination of bacterial strains and eukaryote cell line (46). Antimicrobial compounds produced by Lactobacillus acidophilus provided protection of intestinal epithelium cells against a range of enteric pathogens, such as B. cereus, Staphylococcus aureus, Listeria monocytogenes, Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium, Shigella flexneri, and Escherichia coli (12, 24). More specifically, the indigenous microbial community was found to inhibit the growth of newly arriving bacterial species and prevent their establishment in the community (22).

The rates of gastrointestinal survival of the four B. cereus strains used in this study were remarkably similar, although the strains were selected to represent the diversity of B. cereus in regard to growth temperature (psychrotrophic to mesophilic) and origin of isolation (clinical or food) (Table 1). However, the psychrotrophic food isolate was probably inactivated during the final ileum stage of the gastrointestinal passage simulation. This observation corresponds with the finding that the germination and growth of mesophilic B. cereus strains in the intestinal environment is better than that of psychrotrophic strains (43).

The plethora of enterotoxins and virulence factors with cytotoxic and pore-forming properties produced by vegetative B. cereus cells suggests that the host's epithelial cells may be targeted by diarrheal B. cereus in the small intestine. Moreover, in vitro research demonstrated that the presence of human intestinal cells (Caco-2 cells) specifically induced spore germination (1, 42). The subsequent outgrowth and toxin production of vegetative cells resulted in detachment of the epithelial cells, microvillus damage, decreased mitochondrial activity, membrane damage, and cell lysis (31, 36). These reports from the literature and the data obtained in the current study support the hypothesis that ingested B. cereus spores do not multiply in the intestinal lumen after germination but first adhere to the intestinal mucosa, followed by outgrowth and enterotoxin production, which damages the host epithelium and eventually results in diarrhea. Future research should study the influence of interhost variability in intestinal communities on the intestinal behavior of B. cereus, since it is known that different microbiota show different degrees of growth inhibition toward B. cereus (8). Moreover, the influence of and interactions with the host should be assessed by extending the in vitro simulation experiments with modules that allow bacterial adhesion to mucin layers and interactions with eukaryote cells (28, 38).

Conclusions.

B. cereus spores, except those of the psychrotrophic food isolate, were able to survive throughout gastrointestinal passage as simulated by the in vitro experiment. No bacterial outgrowth and no enterotoxin production were observed in the intestinal lumen, despite the high inoculum concentration of 7 log spores/ml in the mashed potato food matrix. It is hypothesized that B. cereus-induced diarrhea is not caused by massive B. cereus proliferation and toxin production in the intestinal lumen but by localized growth and enterotoxin production at the host's mucus layer or epithelial surface. Moreover, our results indicate that the host's intestinal microbiota is an important defense barrier to control B. cereus outgrowth in the small intestine and, thus, may play an important role in the host's susceptibility to diarrheal food poisoning.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Special Research Funds of Ghent University as a part of the project “Growth kinetics, gene expression and toxin production by Bacillus cereus in the small intestine,” B/09036/02 fund IV1 31/10/2008-31/10/2012, by the Federal Public Service (FOD) Health, Food Chain Safety and Environment project RT09/2 Bacereus, and by a Research Foundation Flanders (FWO) postdoctoral mandate to Andreja Rajkovic.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 24 August 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Andersson A, Granum PE, Ronner U. 1998. The adhesion of Bacillus cereus spores to epithelial cells might be an additional virulence mechanism. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 39:93–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 1a. AOAC International 1995. Microbiological methods—Bacillus cereus in foods—enumeration and confirmation. Official method 980.31. AOAC International, Gaithersburg, MD [Google Scholar]

- 2. Asano SI, Nukumizu Y, Bando H, Iizuka T, Yamamoto T. 1997. Cloning of novel enterotoxin genes from Bacillus cereus and Bacillus thuringiensis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:1054–1057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Beecher DJ, Olsen TW, Somers EB, Wong ACL. 2000. Evidence for contribution of tripartite hemolysin BL, phosphatidylcholine-preferring phospholipase C, and collagenase to virulence of Bacillus cereus endophthalmitis. Infect. Immun. 68:5269–5276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Beecher DJ, Schoeni JL, Wong AC. 1995. Enterotoxic activity of hemolysin BL from Bacillus cereus. Infect. Immun. 63:4423–4428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ceuppens S, et al. 2010. Quantification methods for Bacillus cereus vegetative cells and spores in the gastrointestinal environment. J. Microbiol. Methods 83:202–210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ceuppens S, et al. 2011. Regulation of toxin production by Bacillus cereus and its food safety implications. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 37:188–213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ceuppens S, et al. 2012. Survival of Bacillus cereus vegetative cells and spores during in vitro simulation of gastric passage. J. Food Prot. 75:690–694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ceuppens S, et al. 2012. Impact of intestinal microbiota and gastrointestinal conditions on the in vitro survival and growth of Bacillus cereus. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 155:241–246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Clarkston WK, et al. 1997. Evidence for the anorexia of aging: gastrointestinal transit and hunger in healthy elderly vs young adults. Am. J. Physiol. 272:R243–R248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Clavel T, et al. 2007. Effects of porcine bile on survival of Bacillus cereus vegetative cells and haemolysin BL enterotoxin production in reconstituted human small intestine media. J. Appl. Microbiol. 103:1568–1575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Clavel T, Carlin F, Lairon D, Nguyen-The C, Schmitt P. 2004. Survival of Bacillus cereus spores and vegetative cells in acid media simulating human stomach. J. Appl. Microbiol. 97:214–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Coconnier MH, Lievin V, Bernet-Camard MF, Hudault S, Servin AL. 1997. Antibacterial effect of the adhering human Lactobacillus acidophilus strain LB. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:1046–1052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dressman JB, et al. 1990. Upper gastrointestinal (GI) pH in young, healthy men and women. Pharm. Res. 7:756–761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fagerlund A, Lindbäck T, Storset AK, Granum PE, Hardy SP. 2008. Bacillus cereus Nhe is a pore-forming toxin with structural and functional properties similar to the ClyA (HIyE, SheA) family of haemolysins, able to induce osmotic lysis in epithelia. Microbiology 154:693–704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Firth JD, Putnins EE, Larjava H, Uitto VJ. 1997. Bacterial phospholipase C upregulates matrix metalloproteinase expression by cultured epithelial cells. Infect. Immun. 65:4931–4936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Granum PE, Lund T. 1997. Bacillus cereus and its food poisoning toxins. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 157:223–228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gron C, Oomen A, Weyand E, Wittsiepe J. 2007. Bioaccessibility of PAH from Danish soils. J. Environ. Sci. Health A Tox. Hazard. Subst. Environ. Eng. 42:1233–1239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hagens WI, Lijzen JPA, Sips AJAM, Oomen AG. 2007. Richtlijn: bepalen van de orale biobeschikbaarheid van lood in de bodem. RIVM rapport 711701060/2007. National Institute for Public Health and the Environment (RIVM), Bilthoven, Netherlands [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hardy SP, Lund T, Granum PE. 2001. CytK toxin of Bacillus cereus forms pores in planar lipid bilayers and is cytotoxic to intestinal epithelia. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 197:47–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hartemink R, Domenech VR, Rombouts FM. 1997. LAMVAB—a new selective medium for the isolation of lactobacilli from faeces. J. Microbiol. Methods 29:77–84 [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hartemink R, Kok BJ, Weenk GH, Rombouts FM. 1996. Raffinose-Bifidobacterium (RB) agar, a new selective medium for bifidobacteria. J. Microbiol. Methods 27:33–43 [Google Scholar]

- 22. He XS, et al. 2010. In vitro communities derived from oral and gut microbial floras inhibit the growth of bacteria of foreign origins. Microb. Ecol. 60:665–676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22a. International Organization for Standardization 2004. Microbiology of food and animal feeding stuffs—horizontal methods for the enumeration of presumptive Bacillus cereus—colony count technique at 30°C. ISO 7932. International Organizaton for Standardization, Geneva, Switzerland [Google Scholar]

- 23. Krause N, et al. 2010. Performance characteristics of the Duopath® cereus enterotoxins assay for rapid detection of enterotoxinogenic Bacillus cereus strains. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 144:322–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lievin-Le Moal V, Amsellem R, Servin AL, Coconnier MH. 2002. Lactobacillus acidophilus (strain LB) from the resident adult human gastrointestinal microflora exerts activity against brush border damage promoted by a diarrhoeagenic Escherichia coli in human enterocyte-like cells. Gut 50:803–811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lindbäck T, Fagerlund A, Rodland MS, Granum PE. 2004. Characterization of the Bacillus cereus Nhe enterotoxin. Microbiology 150:3959–3967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Luxananil P, Butrapet S, Atomi H, Imanaka T, Panyim S. 2003. A decrease in cytotoxic and haemolytic activities by inactivation of a single enterotoxin gene in Bacillus cereus Cx5. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 19:831–837 [Google Scholar]

- 27. Marteau P, Minekus M, Havenaar R, Huis in't Veld JH. 1997. Survival of lactic acid bacteria in a dynamic model of the stomach and small intestine: validation and the effects of bile. J. Dairy Sci. 80:1031–1037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Marzorati M, et al. 2011. Studying the host-microbiota interaction in the human gastrointestinal tract: basic concepts and in vitro approaches. Ann. Microbiol. 61:709–715 [Google Scholar]

- 29. Minekus M, Marteau P, Havenaar R, Huis in't Veld JH. 1995. A multicompartmental dynamic computer-controlled model simulating the stomach and small intestine. Altern. Lab. Anim. 23:197–209 [Google Scholar]

- 30. Minekus M, et al. 1999. A computer-controlled system to simulate conditions of the large intestine with peristaltic mixing, water absorption and absorption of fermentation products. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 53:108–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Minnaard J, Humen M, Perez PF. 2001. Effect of Bacillus cereus exocellular factors on human intestinal epithelial cells. J. Food Prot. 64:1535–1541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Molly K, Van de Woestyne M, Verstraete W. 1993. Development of a 5-step multi-chamber reactor as a simulation of the human intestinal microbial ecosystem. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 39:254–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Northfield TC, Mccoll I. 1973. Postprandial concentrations of free and conjugated bile acids down length of normal human small intestine. Gut 14:513–518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Possemiers S, Marzorati M, Verstraete W, Van de Wiele T. 2010. Bacteria and chocolate: a successful combination for probiotic delivery. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 141:97–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Possemiers S, Verthe K, Uyttendaele S, Verstraete W. 2004. PCR-DGGE-based quantification of stability of the microbial community in a simulator of the human intestinal microbial ecosystem. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 49:495–507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ramarao N, Lereclus D. 2006. Adhesion and cytotoxicity of Bacillus cereus and Bacillus thuringiensis to epithelial cells are FlhA and PlcR dependent, respectively. Microbes Infect. 8:1483–1491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Tran SL, Guillemet E, Gohar M, Lereclus D, Ramarao N. 2010. CwpFM (EntFM) is a Bacillus cereus potential cell wall peptidase implicated in adhesion, biofilm formation, and virulence. J. Bacteriol. 192:2638–2642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Van den Abbeele P, et al. 2012. Incorporating a mucosal environment in a dynamic gut model results in a more representative colonization by lactobacilli. Microb. Biotechnol. 5:106–115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Van de Wiele T, Verstraete W, Siciliano SD. 2004. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon release from a soil matrix in the in vitro gastrointestinal tract. J. Environ. Qual. 33:1343–1353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Van de Wiele T, Boon N, Possemiers S, Jacobs H, Verstraete W. 2007. Inulin-type fructans of longer degree of polymerization exert more pronounced in vitro prebiotic effects. J. Appl. Microbiol. 102:452–460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wazny TK, Mummaw N, Styrt B. 1990. Degranulation of human neutrophils after exposure to bacterial phospholipase-C. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 9:830–832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wijnands LM, Dufrenne JB, van Leusden FM, Abee T. 2007. Germination of Bacillus cereus spores is induced by germinants from differentiated Caco-2 cells, a human cell line mimicking the epithelial cells of the small intestine. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:5052–5054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Wijnands LM, Dufrenne JB, Zwietering MH, van Leusden FM. 2006. Spores from mesophilic Bacillus cereus strains germinate better and grow faster in simulated gastro-intestinal conditions than spores from psychrotrophic strains. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 112:120–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wijnands LM, Dufrenne JB, van Leusden FM. 2005. Bacillus cereus: characteristics, behaviour in the gastro-intestinal tract, and interaction with Caco-2 cells. RIVM report 250912003/2005. National Institute for Public Health and the Environment (RIVM), Bilthoven, Netherlands [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wilson M. 2008. Bacteriology of humans, an ecological perspective. University College London, Blackwell Publishing Ltd., Oxford, United Kingdom [Google Scholar]

- 46. Wine E, Gareau MG, Johnson-Henry K, Sherman PM. 2009. Strain-specific probiotic (Lactobacillus helveticus) inhibition of Campylobacter jejuni invasion of human intestinal epithelial cells. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 300:146–152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Young VB. 2012. The intestinal microbiota in health and disease. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 28:63–69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]