Abstract

Inattentional blindness—the failure to see visible and otherwise salient events when one is paying attention to something else—has been proposed as an explanation for various real-world events. In one such event, a Boston police officer chasing a suspect ran past a brutal assault and was prosecuted for perjury when he claimed not to have seen it. However, there have been no experimental studies of inattentional blindness in real-world conditions. We simulated the Boston incident by having subjects run after a confederate along a route near which three other confederates staged a fight. At night only 35% of subjects noticed the fight; during the day 56% noticed. We manipulated the attentional load on the subjects and found that increasing the load significantly decreased noticing. These results provide evidence that inattentional blindness can occur during real-world situations, including the Boston case.

Keywords: Inattentional blindness, illusion of attention, law and psychology, noticing, detection, eyewitness testimony, attention, perception

At 2:00 in the morning on 25 January 1995, Boston police officer Kenny Conley was chasing a shooting suspect who climbed over a chain-link fence. An undercover officer named Michael Cox had arrived on the scene moments earlier, but other officers had mistaken him for a suspect, assaulted him from behind, and brutally beat him. Conley chased the suspect over the fence and apprehended him some time later. In later testimony, Conley said that he ran right past the place where Cox was under attack, but he claimed not to have seen the incident. The investigators, prosecutors, and jurors in the case all assumed that because Conley could have seen the beating, Conley must have seen the beating, and therefore must have been lying to protect his comrades. Conley was convicted of perjury and obstruction of justice and was sentenced to thirty-four months in jail (Lehr 2009).

We have used the term ‘illusion of attention’ to denote the common but mistaken belief that people pay attention to, and notice, more of their visual world than they actually do (Chabris and Simons 2010; Levin and Angelone 2008). None of the principals in this case seem to have realized that Conley could have been telling the truth (Chabris and Simons 2010). He could have failed to notice the beating of Cox because of inattentional blindness (Mack and Rock 1998; Neisser 1979; Simons and Chabris 1999; Simons 2010): While his attention was focused on the suspect he was chasing, he may have been essentially blind to unexpected events that he otherwise would have seen easily.

This explanation is plausible, but generalization from studies using videos or computerized displays (eg, Most et al 2000) to real-world events is not necessarily valid. In laboratory studies participants are seated in front of a screen, under artificial light, indoors, tracking one or more objects within a confined display space at close range. Conley was running outdoors at night chasing a moving target at some distance.

Although some studies have examined inattentional blindness in relatively complex displays (eg, Haines 1991; Neisser 1979; Simons and Chabris 1999), and anecdotal evidence suggests that it plays a role in many real-world contexts (eg, the prevalence of ‘looked but failed to see’ driving accidents), to our knowledge, only one study has systematically documented a failure to notice an unexpected real-world event. Hyman and colleagues (2010) asked pedestrians whether they had noticed a clown that was riding a unicycle near where they were walking; many missed it, especially if they were talking on a mobile phone at the time. Here we ask whether inattentional blindness can occur under realistic conditions similar to those in the Conley-Cox scenario. In contrast to the clown study, our subjects knew they were participating in research, and they were assigned a task requiring focused attention.

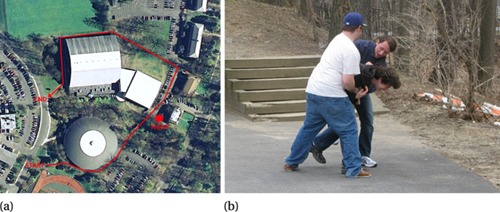

In study 1 we asked 20 subjects (college students, tested individually, participating for money or course credit) to pursue a male confederate while he jogged a 400-meter route at night in an area lit with streetlamps (see figure 1a). The confederate and subject ran at a speed of approximately 2.4 meters per second, for a total running time of about 2 minutes and 45 seconds. At the end of the run, the confederate's heart rate was approximately 148 beats per minute.

Figure 1.

(a) The area on the Union College campus where the studies were conducted (image from Google Maps, maps.google.com). The route run by the confederate and the subjects is shown in red. (b) A close-up view of the fight from the point where the subjects passed closest to it.

Subjects were told to maintain a distance of 30 feet (9.1 meters) while counting the number of times the runner touched his head. At approximately 125 meters into the route, in a driveway 8 meters off the path, three other male confederates staged a fight in which two of them pretended to beat up the third. These confederates shouted, grunted, and coughed during the fight, which was visible to subjects for at least 15 seconds before they passed by it. The runner touched his head three times with his left hand and six times with his right hand, following the same sequence on every trial. The touches always started 30 meters into the run and occurred at approximately 40-meter intervals.

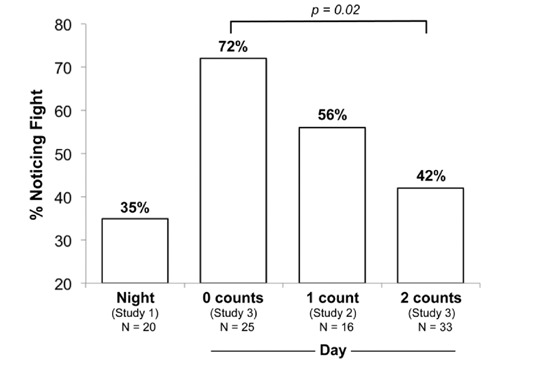

At the end of the route, we first asked the subjects how many head-touches they had counted. Then we asked whether the subjects had seen anything unusual along the route, and then whether they had seen anyone fighting. Only 7 out of 20 subjects (35%) reported seeing the fight in response to at least one of these questions (see figure 2). All seven noticers were able to describe some details of the fight, such as the number of participants and the location. We asked about two additional events that we did not stage (someone dribbling a basketball and someone juggling), and no subjects falsely reported seeing either. These results demonstrate that under real-world visual conditions approximating those experienced by Kenny Conley, people can fail to notice a nearby fight.

Figure 2.

Results of studies 1–3: Percentage of subjects in each condition who reported noticing the simulated fight during questioning after the run. Across studies 2 and 3 each additional mental task imposed was associated with a decrease of about 15% in noticing of the unexpected event.

In study 2 we asked whether the low rates of noticing resulted only from poor viewing conditions due to darkness. We repeated the procedure, on the same route, during the daytime. Now the fight first became visible to the subjects about 20 seconds into their run, and it remained visible for at least 30 seconds. Even so, only 9 out of 16 subjects (56%; see figure 2) noticed the fight, consistent with the inattentional blindness hypothesis.

One hallmark of inattentional blindness is that increasing the effort required by the primary task decreases noticing of unexpected events (eg, Jensen and Simons 2009; Simons and Chabris 1999). If the failure to notice the fight results from inattentional blindness, then manipulating the demands of the counting task should affect noticing rates. Study 3 used the same daytime protocol as study 2, but each of the 58 subjects was randomly assigned (by coin flip) to either keep separate counts of head touches by the runner's left and right hands (high load condition) or to follow the runner without counting (low load).

As shown in figure 2, under a high-attentional load 14 of 33 subjects noticed the fight (42%), but under a low load 18 of 25 noticed (72%). This difference was significant, χ 2(1) = 5.03, p = 0.02, supporting the hypothesis that subjects who missed the unexpected event displayed inattentional blindness. Moreover, participants in the dual-counting condition who did notice the fight counted less accurately (off by M = 1.1 touches) than those who missed it (off by M = 0.2 touches), t (31) = 2.65, p = 0.01, d = 0.86, suggesting that engaging in the counting task had a direct impact on noticing. (In studies 1 and 2 there were no significant differences in accuracy between noticers and missers, p > 0.30 in both cases.) It is possible that the amount of physical exertion during the run, which varied among subjects, would also predict inattentional blindness in this task; future research should examine this.

In three studies with 94 total participants, a substantial number of subjects failed to notice a three-person fight as they ran past it. This real-world inattentional blindness happened both at night and during the day and was modulated by attentional load. Our results represent the first experimental induction of inattentional blindness outside the laboratory.

Kenny Conley eventually won an appeal, and the government decided not to retry him. The inattentional blindness explanation did not contribute to either of these decisions (Chabris and Simons 2010; Lehr 2009). Although no scientific study can prove or disprove a particular cause of a specific historical event, our results show that Conley's claim that he did not see the beating of Michael Cox, the claim that led to his indictment and conviction, might well have been truthful.

Acknowledgements

These studies were approved by the Union College Human Subjects Research Committee. Michael Corti, Joseph Dammann, Elon Gaffin-Cahn, Alexander Katz, Andrew McKeegan, Corey Milan, Timothy Riddell, and Jacob Schneider, all students at Union College who played the roles of the runner and the fighters, and otherwise assisted in the execution of these studies. Diana Goodman, Allie Litt, Lisa McManus, Robyn Schneiderman, and Rachel Scott provided suggestions for the design of these studies during a seminar course at Union College. Dick Lehr's brilliant journalism made us aware of the Boston case of Michael Cox and Kenny Conley and the possibility that inattentional blindness was involved in it. CFC designed and conducted the research, analyzed the data, and drafted the manuscript. AW helped to design and conduct the research. MF helped to conduct the research. DJS contributed to the research design and edited the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Christopher F Chabris, Department of Psychology, Union College, 807 Union Street, Schenectady, NY 12308 USA; e-mail: chabris@gmail.com.

Adam Weinberger, Union College, 807 Union Street, Schenectady, NY 12308 USA; e-mail: weinbera@union.edu.

Matthew Fontaine, Union College, 807 Union Street, Schenectady, NY 12308 USA; e-mail: fontainm@union.edu.

Daniel J Simons, Department of Psychology, University of Illinois, 603 East Daniel Street, Champaign, IL 61820 USA; e-mail: dsimons@illinois.edu.

References

- Chabris C, Simons D. The Invisible Gorilla, and Other Ways Our Intuitions Deceive Us. New York, NY: Crown; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Haines R F. “A breakdown in simultaneous information processing”. In: Obrecht G, Stark L W, editors. Presbyopia Research. New York, NY: Plenum Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Hyman I E, Jr, Boss S M, Wise B M, McKenzie K E, Caggiano J M. “Did you see the unicycling clown? Inattentional blindness while walking and talking on a cell phone”. Applied Cognitive Psychology. 2010;24:597–607. doi: 10.1002/acp.1638. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen M, Simons D J. “The effects of individual differences and task difficulty on inattentional blindness”. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 2009;16:398–403. doi: 10.3758/PBR.16.2.398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehr D. The Fence: A Police Cover-up Along Boston's Racial Divide. New York, NY: HarperCollins; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Levin D T, Angelone B L. “The visual metacognition questionnaire: A measure of intuitions about vision”. The American Journal of Psychology. 2008;121:451–472. doi: 10.2307/20445476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mack A, Rock I. Inattentional Blindness. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Most S B, Simons D J, Scholl B J, Jimenez R, Clifford E, Chabris C F. “How not to be seen: The contribution of similarity and selective ignoring to sustained inattentional blindness”. Psychological Science. 2000;12:9–17. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.00303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neisser U. “The control of information pickup in selective looking”. In: Pick A D, editor. Perception and its Development: A Tribute to Eleanor J Gibson. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1979. pp. 201–219. [Google Scholar]

- Simons D J. “Monkeying around with the gorillas in our midst: Familiarity with an inattentional-blindness task does not improve the detection of unexpected events”. i-Perception. 2010;1:3–6. doi: 10.1068/i0386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons D J, Chabris C F. “Gorillas in our midst: Sustained inattentional blindness for dynamic events”. Perception. 1999;28:1059–1074. doi: 10.1068/p2952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]