Abstract

Piperonylic acid (PA) is a natural molecule bearing a methylenedioxy function that closely mimics the structure of trans-cinnamic acid. The CYP73A subfamily of plant P450s catalyzes trans-cinnamic acid 4-hydroxylation, the second step of the general phenylpropanoid pathway. We show that when incubated in vitro with yeast-expressed CYP73A1, PA behaves as a potent mechanism-based and quasi-irreversible inactivator of trans-cinnamate 4-hydroxylase. Inactivation requires NADPH, is time dependent and saturable (KI = 17 μm, kinact = 0.064 min−1), and results from the formation of a stable metabolite-P450 complex absorbing at 427 nm. The formation of this complex is reversible with substrate or other strong ligands of the enzyme. In plant microsomes PA seems to selectively inactivate the CYP73A P450 subpopulation. It does not form detectable complexes with other recombinant plant P450 enzymes. In vivo PA induces a sharp decrease in 4-coumaric acid concomitant to cinnamic acid accumulation in an elicited tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) cell suspension. It also strongly decreases the formation of scopoletin in tobacco leaves infected with tobacco mosaic virus.

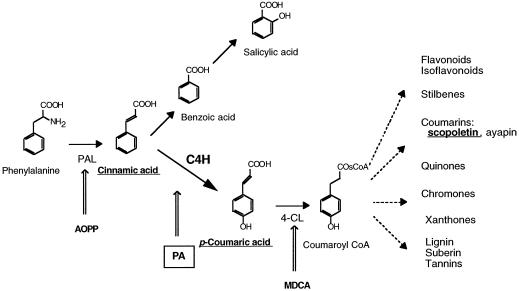

The phenylpropanoid metabolism is a plant-specific pathway leading to compounds of extremely diverse structure and function (Dixon and Paiva, 1995; Werck-Reichhart, 1995). It is involved in the formation of quantitatively major biopolymers such as lignin and suberin, but also in the biosynthesis of signaling molecules such as salicylic acid and isoflavonoids in flower pigments, UV protectants such as anthocyanins, flavonoids, and coumarins, and several classes of phytoalexins. The upstream part of the phenylpropanoid metabolism, which branches from the shikimate pathway at the level of l-Phe, consists of a core of three enzymatic steps leading to 4-coumaroyl CoA (Fig. 1). This set of three reactions, often called the general phenylpropanoid pathway, controls the flux of metabolites toward all families of compounds derived from the C6-C3 skeleton of Phe. Compounds with a C6-C1 structure are not strictly phenylpropanoids, but also derive from l-Phe. They originate from the core pathway intermediates cinnamic acid or 4-coumaric acid (Yalpani et al., 1993). Molecules with a C6-C1 backbone include benzoic and salicylic acids and economically important compounds such as vanillin.

Figure 1.

Branching and inhibitors of the phenylpropanoid pathway. AOPP, α-Amino-β-phenylpropionic acid; MDCA, methylenedioxycinnamic acid.

The second step in the core phenylpropanoid pathway is the hydroxylation of trans-cinnamic acid to 4-coumaric acid. The reaction is catalyzed by C4H, a member of the superfamily of Cyt P450 heme-thiolate proteins. P450s are monooxygenases that catalyze the oxidation of a remarkably broad range of endogenous and exogenous chemicals in all organisms. In plants they play important roles in biosynthetic pathways, including those of sterols, isoprenoids, alkaloids, oxygenated fatty acids, and phenylpropanoids (Bolwell et al., 1994; Durst and O'Keefe, 1995; Schuler, 1996). They are also involved in the metabolism and sometimes in the activation of many herbicides, insecticides, and other xenobiotics. CYP73A1 is a C4H from Jerusalem artichoke (Helianthus tuberosus). Its coding sequence was isolated from tuber tissues (Teutsch et al., 1993) and expressed in yeast (Urban et al., 1994). The yeast-expressed enzyme is catalytically active and capable of hydroxylating cinnamic acid with a very high efficiency (kcat ranging from 100 to 400 min−1).

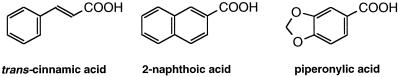

The high activity of the recombinant enzyme led us to investigate its activity toward other potential substrates, natural plant components, and xenobiotics. Several exogenous molecules were thus found to be substrates of CYP73A1 (Pierrel et al., 1994; Schalk et al., 1997). The efficiency of the metabolism of the xenobiotic molecules largely relied on their structural analogy to the natural substrate. A systematic structure-activity study recently led to the characterization of some good alternative substrates and high-affinity inhibitors of the enzyme, and of the structural requirements for an efficient binding into the active site of CYP73A1 (Schalk et al., 1997). The ideal ligand of C4H was thus defined as a rigid hydrophobic backbone of the size of a bicyclic aromatic structure (e.g. naphthalene), bearing one or several small negatively charged substituent(s) centered around carbon 2 of the naphthalene ring, the prototype alternative substrate being 2-naphthoic acid (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Structural analogy between substrates of CYP73A1.

PA is a natural molecule extracted from the bark of the Paracoto tree that roughly fulfills all of these requirements. PA contains a MDP function at a position suitable for oxidative attack by CYP73A1. Many compounds with MDP function have been shown to inhibit mammalian or insect P450 enzymes both in vitro and in vivo (Franklin, 1977; Wilkinson et al., 1984; Ortiz de Montellano and Correia, 1995). They were shown to act as mechanism-based inactivators and to require P450-catalyzed metabolism to generate a MI forming a stable complex with the enzyme (Franklin, 1971). Available data suggest that the MI is likely a carbene that binds as the sixth coordinant to the heme iron (Mansuy et al., 1979).

We have tested PA inhibition of recombinant CYP73A1 and show that it behaves as a very potent, mechanism-based inhibitor of C4H. It is effective in vitro on the recombinant enzyme, being far more efficient than other MDP compounds. It is apparently selective for C4H. Assays performed in vivo on tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) leaves and cell cultures indicate that it can be used to inactivate C4H and to block the input of precursors into the main C6-C3 pathway. To our knowledge, it is the first selective and quasi-irreversible inhibitor of the C4H so far described.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals

All methylenedioxy compounds were from Aldrich. Scopoletin was from Carl Roth GmbH (Karlsruhe, Germany). Ayapin was a gift of Dr. Jesus Jorrín (Escuela Technica Superior Ingenieros Agronomica Montes, Córdoba, Spain). β-Megaspermin was kindly provided by Dr. S. Kauffmann (Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, UPR 406, Strasbourg, France). trans-[3-14C]Cinnamic acid was from Isotopchim (Ganagobie, France), [1-14C]lauric acid from Comissariat à l'Energie Atomique (Gif-sur-Yvette, France), and [1-14C]palmitic acid from DuPont-New England Nuclear. All chemicals were of the highest purity available from commercial sources and were used without further purification.

Yeast and Plant Microsomes

The Saccharomyces cerevisiae W303–1B strain (Mat α; ade2-1; his3-11,-15; leu2-3,-112; ura3-1; canR; cyr+), also designated W(R), overexpressing its own NADPH-P450 reductase, was constructed by Truan et al. (1993). Plasmid C4H/V60, the yeast-transformation procedure, and the preparation of yeast microsomes were described by Urban et al. (1994). Microsomes from the W(R) yeast strain transformed with the void V60 plasmid were used as a negative control. Yeast microsomes expressing CYP51, CYP81B1, CYP76B1, or CYP86A1 were prepared as described by Cabello-Hurtado et al. (1997, 1998a), Batard et al. (1998), and Benveniste et al. (1998), respectively.

Microsomes were prepared from Jerusalem artichoke (Helianthus tuberosus L. var. Blanc commun) tuber tissues that were sliced, aged, and treated with aminopyrine, MnCl2, or CuCl2 as described previously (Werck-Reichhart et al., 1990; Cabello-Hurtado et al., 1998b).

Spectrophotometric Measurements

Spectrophotometric measurement of total P450 content, quantification of microsomal protein, measurement of binding spectra, and determination of the binding constants were performed as described previously (Gabriac et al., 1991).

Enzymatic Assays

The assay of C4H activity with radiolabeled trans-cinnamic acid as the substrate was described by Reichhart et al. (1980). Possible PA reaction products were analyzed by reverse-phase HPLC on an instrument (model 510, Waters) equipped with an absorbance detector (model 480, Waters). Separations were performed on a C18 5 μ 100 × 4.6 mm Brownlee column using a mobile phase consisting of aqueous acetonitrile containing 0.1% acetic acid at a flow rate of 1 mL min−1. Kinetic data were fitted using the nonlinear regression program DNRPEASY derived by Duggleby (1984) from DNRP53.

Enzyme Inactivation

The time-dependent inhibition of the C4H activity in transformed yeast microsomes was investigated using a general dilution procedure (Silverman, 1996). Yeast microsomes (400 nm CYP73A1) were preincubated at 30°C in 0.1 m sodium phosphate, pH 7.4, 50 μm NADPH, 1 mm Glc-6-P, and 1 unit mL−1 Glc-6-P dehydrogenase with 0 to 20 μm PA. At timed intervals, aliquots were diluted 20-fold into a second incubation mixture containing radiolabeled cinnamic acid (200 μm) to assay residual activity. PA concentrations and preincubation times were chosen in accordance with the results of binding experiments shown in Figure 3 to be pseudo-first-order and not saturating conditions.

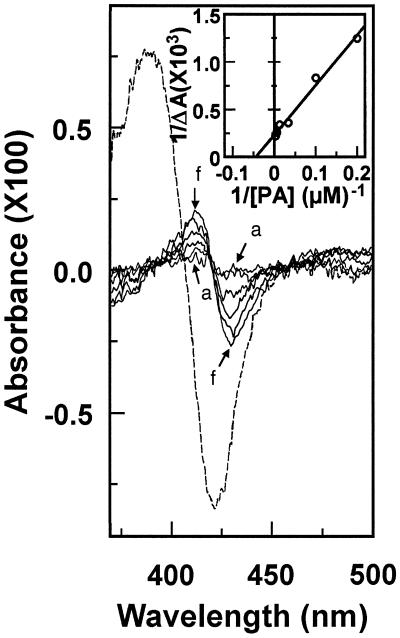

Figure 3.

Binding of PA to CYP73A1. Difference spectra were recorded in 0.1 m sodium phosphate, pH 7.4, containing CYP73A1 (0.12 μm) in microsomes from transformed W(R) yeast. Solid lines correspond to the difference spectra obtained after addition of increasing amounts (5, 10, 30, 80, 180, and 380 μm) of PA to the sample cuvette (curves a–f). An equal volume of buffer was added to the reference. The broken line is the difference spectrum obtained under the same conditions after addition of 100 μm cinnamic acid. Inset, Double-reciprocal plot of ΔA412–430 versus PA concentration.

Treatments of Leaf Tissues and Tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum L. cv Samsun, NN) Cell Suspension

Three-week-old tobacco plants were inoculated on the uppermost fully expanded leaves with TMV. Leaves were syringe infiltrated with water or 500 μm PA 16 h after inoculation with TMV. Infiltrated tissues were collected 3 d after inoculation, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C before analysis.

The tobacco BY-2 cell suspension was maintained as described by Nagata et al. (1992). Synchronization of the cells was achieved according to the method of Reichheld et al. (1995) with 3 mg mL−1 aphidicolin and 1.5 mg mL−1 propyzamide. Elicitor treatment of cell-suspension cultures was performed 48 h after aphidicolin treatment with 50 nm β-megaspermin, an elicitin protein purified from culture filtrates of Phytophthora megasperma (Baillieul et al., 1995). PA (100 μm) was added at the same time as βmegaspermin. Cells were harvested by vacuum filtration 13 h after treatment, and frozen in liquid nitrogen.

Analytical Procedures

Tissue samples (0.5 g) and frozen cells (0.2–0.3 g) were extracted using a protocol described by Bailleul et al. (1995). Scopoletin content was determined by on-line UV absorption and fluorescence detection after separation on a C18 reverse-phase column (Dorey et al., 1997). Total cinnamic and 4-coumaric acids extracted after acid hydrolysis were first separated by chromatography on plates (Silicagel 60F254, Merck) developed with toluene-acetic acid-water (6:7:3, v/v, organic phase). 4-Coumaric (RF 0.37) and cinnamic acids (RF 0.62) were scraped and eluted with MeOH. Eluates were further analyzed and quantified on a C18 reverse-phase column by HPLC using a photodiode array detector (model 996, Waters). Samples were eluted with a gradient of increasing solvent B (acetonitrile) in solvent A (25 mm NaH2PO4 adjusted to pH 3.0 with phosphoric acid): 0 to 5 min, 5% B; 5 to 20 min, 5% to 20% B; and 20 to 26 min, 20% to 80% B. The A290 and A280 of the eluate were monitored for quantification of cinnamic and 4-coumaric acids, respectively. Retention times and calibration curves were established with authentic samples.

RESULTS

Binding of PA to CYP73A1

A shift in the Soret maximum from 420 to about 390 nm is usually observed upon addition of substrates to oxidized native P450s (Jefcoate, 1978). The resulting difference spectrum is referred to as type I. The type I spectrum reflects the increase in the high-spin character of the iron, which is a consequence of the displacement of water bound as sixth iron ligand on the distal face of the heme (Fisher and Sligar, 1987; Helms et al., 1996).

Binding of trans-cinnamic acid to CYP73A1 results in a typical type I spectrum (Fig. 3). Addition of PA to a microsomal suspension of W(R) yeast expressing CYP73A1 also induced a shift in absorbance that clearly resulted from its binding in the P450 heme pocket (Fig. 3). The oxidized and PA-bound versus oxidized difference spectrum presented a peak at about 412 nm and a trough around 430 nm. The ΔA412−430 increased with PA concentration and saturation was obtained at a concentration of about 400 μm. The apparent Ks calculated from the double-reciprocal plot of ΔA412−430 versus substrate concentration was 45 ± 11 μm. The PA-induced spectrum was reminiscent of but not identical to the spectrum induced by cinnamic acid. The shift of the Soret maximum to 412 nm in the CYP73A1-PA complex possibly indicates a PA-induced alteration in the heme-protein structure or a direct interaction of PA with the iron-porphyrin system. The small amplitude of the absorbance change also suggests that the solvent was not completely displaced from the immediate heme environment.

Formation of a CYP73A1-MI Complex

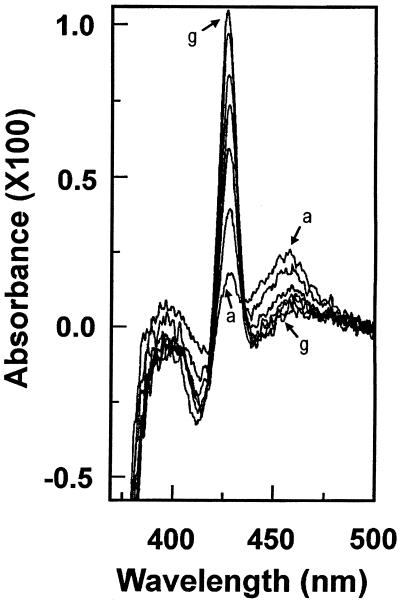

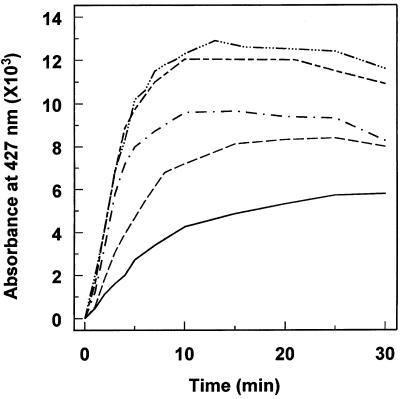

A typical difference spectrum showing a dual Soret absorption and usually referred to as type III was obtained upon metabolism of MDP compounds by animal P450s (Hodgson et al., 1973). In the presence of NADPH the PA-binding spectrum previously observed evolved in a time-dependent manner into a spectrum showing two distinct peaks (Fig. 4), one at 455 nm, which appeared immediately and decreased upon incubation, and a second, much sharper peak at 427 nm, which increased rapidly in the first few minutes of incubation. The change in absorbance was dependent on NADPH and time of incubation. It was not observed with control microsomes prepared from yeast transformed with a void plasmid.

Figure 4.

Formation of a complex between the CYP73A1 and PA metabolite. CYP73A1 (0.12 μm) in transformed yeast microsomes was incubated at 30°C in 0.1 m sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, containing 500 μm NADPH. PA was added to the sample cuvette at a final concentration of 30 μm. Difference spectra were recorded 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, and 10 min after adding PA (curves a–g).

The increase in ΔA427−490 was recorded as a function of time for various concentrations of PA (Fig. 5). It displayed saturation kinetics as a function of both time and PA concentration. After 15 to 30 min of incubation, the amplitude of ΔA427−490 started to decline slowly. This was likely the result of a reoxidation of CYP73A1 (Franklin, 1971), since both formation and stability of the complex absorbing at 427 nm were enhanced by reduction of heme iron. The addition of sodium dithionite to both cuvettes after completion of the reaction with NADPH resulted in a slight increase in A427 and in a complete disappearance of the peak at A455. After complete reduction, the spectrum remained quite stable. A similar stabilization of the P450 complex by subsequent addition of sodium dithionite was observed with several MDP compounds (Hodgson et al., 1973; Yu et al., 1980).

Figure 5.

Time- and inhibitor-concentration-dependence of the formation of the complex between CYP73A1 and PA. Formation of the complex was measured as described in Figure 4. Time-dependent appearance of the 427-nm peak was recorded for PA concentrations of 2 (———), 5 (– – –), 15 ( · – · ), 30 (- – -), and 50 μm ( · · · – · · · ).

The 427-nm-absorbing species was not formed with sodium dithionite alone. Metabolic activation of PA is thus required, and the type III spectrum does not result from the direct binding of PA to reduced P450. These data strongly suggest that the absorbance changes observed in the presence of PA and NADPH actually reflect the formation of a P450-bound MI.

Reversibility of the P450-MI Complex

The animal P450-MI complexes were reported to be reversible by type I ligands (Elcombe et al., 1975; Dickins et al., 1979), but not by CO (Hodgson and Philpot, 1974). A reversion of the CYP73A1-MI complex by the substrate was also detected by differential spectrophotometry. CYP73A1 in yeast microsomes was incubated with NADPH in both cuvettes and PA in the sample. After 10 min (i.e. completion of the reaction), a baseline between the two cuvettes was recorded. The subsequent addition of cinnamic acid (100 μm) to both cuvettes resulted in the time-dependent formation of a trough at 427 nm. The initial type III spectrum could be totally reversed (i.e. the trough reached the same amplitude as the peak previously observed), but the reversion was much slower than the formation of the complex, lasting 60 instead of 10 min (not shown). The complex was also efficiently reversed by 2-hydroxy-1-naphthoic acid, a high-affinity ligand and competitive inhibitor of CYP73A1 (Schalk et al., 1997).

Addition of CO to the sample cuvette after stabilization of the complex with sodium dithionite did not shift the absorption to 450 nm. The P450-MI complex was thus not dissociated by CO (not shown), in agreement with previous reports (Hodgson et al., 1973).

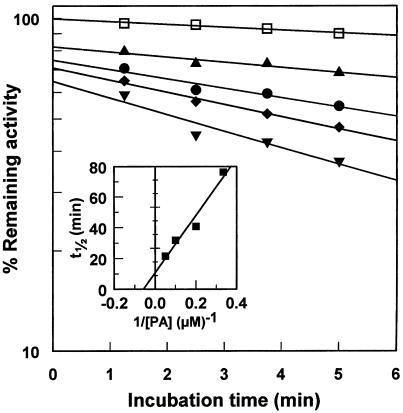

Kinetics of CYP73A1 Inactivation by PA

To confirm mechanism-dependent inactivation, CYP73A1 in a yeast microsomal suspension was preincubated with PA and NADPH before measurement of C4H residual activity. Pseudo-first-order kinetics were observed for the initial phase of the inactivation (Fig. 6). Inactivation rates increased with PA concentration. Despite a 20-fold dilution of the preincubation medium before the measurement of residual activity, coordinate intercepts reflect a significant competitive inhibition and confirm that PA binds to the same site as cinnamic acid. The plot of the estimated half-life for inactivation (t1/2) at each PA concentration compared with the 1/PA concentration is characteristic of an inactivation that proceeds with saturation (Silverman, 1996). The kinetic constants calculated from the plot are KI = 17 μm and kinact = 0.064 min−1.

Figure 6.

Time- and concentration-dependent inactivation of CYP73A1 by PA. CYP73A1 in W(R) yeast microsomes was preincubated at 30°C in 0.1 m sodium phosphate, pH 7.4, with 50 μm NADPH, 1 mm Glc-6-P, 0.2 unit of Glc-6-P dehydrogenase, and 0 (□), 3 (▴), 5 (•), 10 (♦), and 20 μm (▾) PA. The residual C4H activity was then assayed as described in Methods. Data correspond to means of duplicates. Inset, Times of one-half inactivation (t1/2) estimated from linear regression analysis were plotted against the reciprocal of PA concentration.

Other Methylenedioxy Compounds

MDP compounds are widely used to characterize P450-dependent reactions, and are often considered to be broad-specifity inhibitors of P450 enzymes. Therefore, we tested and compared the inhibition of C4H obtained with a set of different MDP compounds, some of them showing structural similarity to cinnamic acid, to that obtained with PA. The MDP compounds tested widely differ in the size and nature of their side chains (Table I). Several of these compounds have previously been reported to inhibit insect or animal enzymes (Hodgson and Philpot, 1974). Ayapin is a natural coumarin synthesized by H. tuberosus in response to elicitation or pathogen attack (Gutiérrez-Mellado et al., 1996; Cabello-Hurtado et al., 1998b). Its reported fungicidal effect (Tal and Robeson, 1986) probably relies on its methylenedioxy function. Residual C4H activity was assayed in yeast microsomes after 15 min of preincubation with each compound (100 μm) in the presence of NADPH. Table I shows that PA is by far the most effective inhibitor of CYP73A1. The second most efficient molecule is another analog of cinnamic acid, 3,4-(methylenedioxy)phenyl acetic acid. Ayapin also produces a significant inactivation. The 3,4-methylenedioxy derivative of cinnamic acid, which is commonly used as an inhibitor of the coumaroyl-CoA ligase (Funk and Brodelius, 1990), is a very poor inhibitor of C4H.

Table I.

Inactivation of CYP73A1 by methylenedioxy compounds

| MDP Compound | C4H Inhibition |

|---|---|

| % | |

| PA | 58 |

| Piperonyl butoxide | 9 |

| Piperonylamine | 0 |

| Piperonyl acetate | 2 |

| Piperonyl chloride | 13 |

| 3,4-(Methylenedioxy)-cinnamic acid | 2 |

| Piperonyl alcohol | 2 |

| Piperonylnitrile | 7 |

| Piperonal | 5 |

| 3,4-(Methylenedioxy)-toluene | 8 |

| 3,4-(Methylenedioxy)-phenyl acetic acid | 15 |

| Methylenedioxy-aniline | 13 |

| Piperonyl isobutyrate | 5 |

| Ayapin | 13 |

| Safrole | 8 |

| Isosafrole | 5 |

CYP73A1 in transformed yeast microsomes were preincubated at a concentration of 250 nm with 4 mm Glc-6-P, 0.1 unit of Glc-6-P dehydrogenase, 100 μm NADPH, and 100 μm of each inhibitor. After 15 min, 10 μL of the mixture was transferred into the C4H assay for determination of residual activity. The assay contained 4 mm Glc-6-P, 0.1 unit of Glc-6-P dehydrogenase, 100 μm NADPH, and 100 μm radiolabeled trans-cinnamic acid in a final volume of 200 μL. 4-Coumaric acid formed after 3 min of incubation was determined as described previously (Reichhart et al., 1980).

Selectivity of PA toward C4H

The efficiency of PA as a mechanism-based inhibitor of C4H seems to largely rely on its high structural homology to cinnamic acid. However, the MDP function can potentially inactivate any P450 enzyme. To determine if PA was selective for C4H or if it also inactivated other P450s, we made an estimation of the proportion of P450 converted into the MI complex and compared it with the proportion of C4H in total plant microsomes. No PA metabolite was detected by HPLC analysis of the incubation medium, suggesting that no metabolite leaves the active site of the P450(s) that catalyzes its activation and binds other P450 enzymes. The amount of P450-MI complex determined by spectrophotometry can thus be used to measure the proportion of total P450 capable of metabolizing PA in a mixture such as that in plant microsomes.

A similar approach was proposed by Franklin (1991) to determine the proportion of P450 isozymes capable of oxidatively metabolizing macrolide antibiotics to a nitroso intermediate in liver microsomes. To determine an extinction coefficient (ε) for the Soret maximum of the reduced CYP73A1-MI complex, we measured ΔA427−490 for several dilutions of yeast microsomes (i.e. 30–150 nm CYP73A1) after 15 min of incubation with 50 μm PA and a NADPH-regenerating system and subsequent complete reduction with sodium dithionite. ΔA427−490 was proportional to the CYP73A1 content of the incubation medium: the ε427−490 was 102 mm−1 cm−1. This extinction coefficient was then used to determine the P450-MI content (Table II) in microsomes of Jerusalem artichoke tubers treated to modify P450 enzyme subpopulations (Batard et al., 1995, 1997; Cabello-Hurtado et al., 1998b). CYP73A1 contents were determined in the same microsomes from the substrate-binding spectra (Urban et al., 1994). The difference spectra observed upon incubation of plant microsomes with PA and NADPH were identical to those obtained with recombinant CYP73A1. Table II shows that the C4H contents deduced from substrate binding were very similar to the content of P450-MI complexes measured in the same microsomes. Only the results obtained with microsomes prepared from aminopyrine-treated tissues suggested the possible existence of another P450 subspecies able to form a MI complex with PA.

Table II.

Determination of the amounts of CYP73A1-MI complex formed in Jerusalem artichoke tuber microsomes after incubation with PA

| Tuber Treatment | Total P450 | C4H | MI Complex | C4H | MI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pmol mL−1 | % of total P450 | ||||

| Wounding | 79 ± 4 | 47 ± 3 | 50 ± 5 | 59 | 62 |

| CuCl2 | 66 ± 3 | 15 ± 1 | 17 ± 2 | 22 | 25 |

| MnCl2 | 225 ± 17 | 82 ± 6 | 86 ± 1 | 36 | 38 |

| Aminopyrine | 95 ± 2 | 24 ± 1 | 33 ± 2 | 25 | 35 |

Microsomes were prepared from tuber tissues, sliced, and aged for 24 h in water (wounding) or 1 mm CuCl2, for 48 h in 20 mm aminopyrine, or for 72 h in 25 mm MnCl2, pH 7.0. All measurements were performed by differential spectrophotometry. Microsomes were diluted in 0.1 m sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4. Total P450 content was estimated from the reduced-CO binding spectra according to the method of Omura and Sato (1964). The C4H content was estimated from trans-cinnamic acid binding to native microsomes as previously described (Urban et al, 1994). The MI complex was quantified as described in Results. All values are means of triplicates.

To further confirm the selectivity of PA, we tested if other available yeast-expressed plant P450 enzymes, CYP81B1 and CYP76B1 from Jerusalem artichoke, CYP51 from wheat, and CYP86A1 from Arabidopsis, were able to form MI complexes with PA. No MI-complex formation was detected when yeast microsomes containing from 68 to 125 pmol mg−1 protein of either P450 were incubated for 15 min with concentrations up to 100 μm PA (data not shown).

Effect of PA on the Phenylpropanoid Metabolism in Vivo

PA seems to be a potent and selective inhibitor of C4H in vitro. The in vivo activity of the molecule could be limited by a low permeability of the plant tissues or by a fast metabolism of the compound. We therefore tested the effects of PA on the accumulation of some phenylpropanoid intermediates in induced plant cells or leaf tissues.

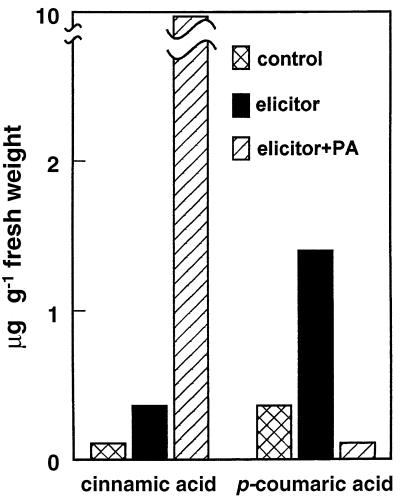

A BY2 tobacco cell suspension was simultaneously elicited with β-megaspermin and given 100 μm PA. The cinnamic and 4-coumaric acid contents of the cells were determined 13 h after the beginning of the treatment (Fig. 7). The sharp decrease in 4-coumaric acid (13-fold), together with the strong cinnamic acid accumulation (20-fold) observed relative to control cells treated with elicitor alone, were consistent with an effective inhibition of C4H.

Figure 7.

Effect of PA treatment on cinnamic and 4-coumaric acids concentrations in elicited tobacco cells. A synchronized BY2 tobacco cell suspension was treated with 50 nm β-megaspermin, alone or together with 100 μm PA. Total cell contents in cinnamic and 4-coumaric acids (free plus conjugated forms) were determined after 13 h of treatment, as described in Methods.

Scopoletin is a simple 7-hydroxylated coumarin. Its biosynthetic pathway is not elucidated, but involves at least the first two steps of the core phenylpropanoid pathway (Fritig et al., 1970). Scopoletin accumulation is observed in cultured tobacco cells in response to fungal elicitor. In tobacco leaves scopoletin is responsible for the fluorescent rings observed around local lesions occurring in the hypersensitive response to TMV. When plant cells were treated simultaneously with β-megaspermin and PA, scopoletin accumulation was considerably decreased compared with cells treated with β-megaspermin alone (Table III). A similar effect was observed when 500 μm PA was injected in TMV-infected tobacco leaves. Scopoletin accumulation measured after 3 d was decreased by about 70% compared with leaves injected with water (Table III).

Table III.

Effect of PA on the induced accumulation of scopoletin in plant cells or tissues

| Tissue and Treatment | Scopoletina

|

Inhibition | |

|---|---|---|---|

| −PA | +PA | ||

| % | |||

| BY2 cells treated with elicitor | 13 | 3 | 77 |

| Leaves infected with TMV | 110 | 35 | 68 |

Synchronized BY2 tobacco cell suspensions were treated with 50 nm β-megaspermin, alone (−PA) or together with 100 μm PA (+PA). The scopoletin content of the cells was analyzed 13 h after treatment. Tobacco leaves were syringe infiltrated with water or 500 μm PA 16 h after inoculation with TMV. Scopoletin content of the tissues was determined 3 d after inoculation. Results are given in relative units compared with controls without elicitor treatment or TMV inoculation. Scopoletin contents in control cells and tissues were 0.11 and 0.12 μg g−1 fresh weight, respectively.

Relative increase compared with noninduced controls.

DISCUSSION

Based on a structure-activity study we have recently characterized strong competitive inhibitors of C4H (Schalk et al., 1997). Mechanism-based inactivators are potentially more efficient and selective, since (a) they must satisfy the structural constraints imposed for binding to the active site, (b) the inhibitor must be acceptable as a substrate for its catalytical activation, and (c) reactive species produced by catalysis irreversibly or quasi-irreversibly alter the enzyme and remove it permanently or quasi-permanently from the catalytic pool (Ortiz de Montellano and Correia, 1995).

First used empirically as herbicide synergists or drug potentiators, MDP compounds have subsequently been shown to exert their activity via mechanism-based inactivation of xenobiotic-metabolizing P450 enzymes. The inhibition of P450 activities by MDP compounds and the mechanism-based formation of MI complexes have been extensively studied in a number of species both in vitro and in vivo and found to affect a broad range of P450-dependent reactions (Franklin, 1971; Hodgson and Philpot, 1974; Elcombe et al., 1975). Inhibition of P450 by MDP compounds has also been observed in plant tissues (Varsano et al., 1992; Kusukawa et al., 1995). It is generally accepted that the P450 inactivation and the unusual optical absorption spectra observed with inactivated enzymes result from the direct interaction with heme iron of a carbene formed by hydrogen abstraction or by elimination of water from a hydroxymethylene intermediate.

The strong π-acceptor character of the carbene explains the shift of the Soret peak toward long-absorption wavelengths and the stability of the complex that is not displaced by CO or dioxygen (Wilkinson et al., 1984). MDP-P450 complexes are preserved through microsome extraction, dialysis, detergent treatment (Elcombe et al., 1975), oxidation, and re-reduction of the enzyme (Franklin, 1979). Inactivation, however, is not completely irreversible since the carbene can be displaced by type-I ligands (i.e. substrates), in particular once the enzyme is re-oxidized. There is a considerable degree of selectivity in the inhibitory potency of the MDP compounds toward different P450 enzymes (Wilkinson et al., 1984; Murray et al., 1993). The interactions of MDP side chains and aromatic cycles with the protein regions adjacent to the heme determine not only the binding of the compound prior to metabolism, but also the stability and further transformation of the complex.

In vitro, PA shows all of the characteristics of a specific ligand and of a very potent mechanism-based inactivator of C4H. The totality of the recombinant enzyme is complexed after less than 10 min in the presence of 30 μm PA, with a quasi-total loss in catalytic activity. Inactivation and formation of the MI complex are observed only in the presence of NADPH, increase in a time-dependent manner, and exhibit saturation kinetics. The presence of substrate or competitive inhibitors slows down or completely reverses the formation of the complex. This reversion process is, however, slow compared with inactivation and requires high, most likely nonphysiological, substrate concentrations.

The optical difference spectrum resulting from incubation of CYP73A1 with PA in the presence of NADPH is typical of a P450-MDP metabolite interaction (Wilkinson et al., 1984). This spectrum differs slightly from the typical type-III spectrum observed with the majority of MDP derivatives, since the peak at 455 nm appears only very transiently. The two peaks detected in the MI-bound versus free-P450 difference spectra are thought to reflect the formation of two distinct types of MI-P450 complexes, but the exact nature of the two complexes has not been elucidated. The 455-nm peak is usually considered to reflect only the interaction of the carbene with heme iron. Conversion of the 455-nm-absorbing entity into a 427-nm-absorbing complex seems to depend both on the substituents of the MDP molecules and on the P450 isoform that metabolizes it.

It has been proposed that the 427-nm peak could result from interactions of the MDP side chains with the protein in the vicinity of heme or from a shift in the spin state of the heme iron. The most plausible explanation, however, seems to be a rupture of the bond between heme iron and its Cys thiolate fifth ligand (Dahl and Hodgson, 1979; Wilkinson et al., 1984). It can be speculated that this rupture results from a stretching of the iron-sulfur bond induced by the electron-withdrawing properties of MDP substituants or by the interactions of the MDP side chains with the protein. An increase in the iron-sulfur distance upon CO binding has been demonstrated for P450cam (Raag and Poulos, 1989). In addition, the strong electrostatic interactions that are likely to ensure PA binding to the apoprotein and the shortened ring structure of the molecule compared with an ideal substrate (Fig. 2) would support the hypothesis of a very stretched complex. It has been reported that the presence of electron-withdrawing substituants on the MDP aromatic ring tends to favor the production of CO from the methylenic carbon of the methylenedioxy ring (Yu et al., 1980), leading to the formation of a typical complex absorbing at 450 nm. It is interesting to note that despite the presence of a carboxylic function on PA, no formation of a CYP73A1-CO complex was detected.

Its close structural analogy to the natural substrate seems to confer on PA a real selectivity for C4H. None of the other plant P450s that we tested so far, which were reported as fatty acid hydroxylases or sterol or 7-ethoxycoumarin O-dealkylases, were capable of forming spectrally detectable complexes that would indicate enzyme inactivation. PA was also apparently selective for C4H in microsomes from Jerusalem artichoke. However, the potential number of P450s in plant tissues is extremely high. In the phenylpropanoid pathway alone, more than 16 P450-dependent reactions have been characterized, and more than 120 plant P450 genes have already been isolated. C4H is very abundant in plants, as shown in Jerusalem artichoke tissues (Table II). Formation of a MI complex with a minor P450 subpopulation in plant microsomes would not be detectable by the spectrophotometric approach used in this work. It is thus reasonable to assume that PA is not strictly specific to C4H, although inactivation of another P450 isoform with a similar efficiency is highly improbable.

PA also seems to be an efficient inactivator of C4H in vivo, blocking the synthesis of 4-coumaric acid and inducing the accumulation of cinnamic acid in plant cells. Tools were already available to block the steps upstream and downstream in the pathway (Fig. 1). α-Aminooxy-β-phenylpropionic acid, which inhibits Phe-ammonia lyase, has been available and used extensively for many years to block the whole phenylpropanoid pathway (Amrhein and Gödeke, 1977). 3,4-(Methylenedioxy)-cinnamic acid has recently been described as a potent inhibitor of the coumaroyl CoA-ligase (Funk and Brodelius, 1990). This compound, which also bears a methylenedioxy function and is a structural analog of cinnamic acid, does not affect C4H. We have previously shown that size and charge are critical determinants in the binding of ligands into the substrate pocket of CYP73A1 (Schalk et al., 1997). This is confirmed by the data presented in Table I. It is thus probable that the methylenedioxy ring renders the molecule too large to bind or to have access to the active site of C4H. MDCA remains a potential inhibitor of other P450 enzymes downstream in the pathway.

Compared with aminooxy-β-phenylpropionic acid and 3,4-(methylenedioxy)-cinnamic acid, PA offers new potential applications. It can be used to selectively block the C6-C3 metabolism and, possibly, to shift the precursor flow into the formation of C6-C1 compounds such as benzoic and salicylic acids. It also offers a possibility to determine if 4-hydroxybenzoic acids derive from cinnamic acid or must be formed from 4-hydroxycinnamic acids. Many reports (Werck-Reichhart, 1995; Sewalt et al., 1997) have suggested that C4H, possibly via its product and substrate, has a regulatory function in the coordinate regulation of the phenypropanoid pathway. PA is a new tool to test this hypothesis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Drs. D. Pompon and P. Urban for providing the W(R) yeast strain and the pYeV60 expression vector and Dr. I. Benveniste for microsomes of yeast expressing CYP86A1. We also thank M.F. Castaldi for her technical assistance. The critical reading of the manuscript by F. Bernier and R. Kahn is gratefully acknowledged.

Abbreviations:

- C4H

trans-cinnamate 4-hydroxylase (NADPH:oxygen oxidoreductase [4-hydroxylating] EC 1.14.13.11)

- MDP

methylenedioxyphenyl

- MI

metabolic intermediate

- PA

piperonylic acid

- TMV

tobacco mosaic virus

Footnotes

This work was supported by a Ministére de la Recherche et de l'Enseignement Supériur grant to M.S. F.C.-H. was supported by a postdoctoral grant from the Spanish Ministerio de Agricultura, Pesca y Alimentación, and M.-A.P. was supported by the Bio Avenir program funded by Rhône-Poulenc, the Ministère de la Recherche et de l'Espace, and the Ministère de l'Industrie et du Commerce Extérieur.

LITERATURE CITED

- Amrhein N, Gödeke KH. Plant Sci Lett. 1977;8:313–317. [Google Scholar]

- Baillieul F, Genetet I, Kopp M, Saindrenan P, Fritig B, Kauffmann S. A new elicitor of the hypersensitive response in tobacco: a fungal glycoprotein elicits cell death, expression of defence genes, production of salicylic acid, and induction of systemic acquired resistance. Plant J. 1995;8:551–560. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1995.8040551.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batard Y, LeRet M, Schalk M, Robineau T, Durst F, Werck-Reichhart D. Plant J. 1998;14:111–120. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1998.00099.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batard Y, Zimmerlin A, Le Ret M, Durst F, Werck-Reichhart D. Multiple xenobiotic-inducible P450s are involved in alkoxycoumarins and alkoxyresorufins metabolism in higher plants. Plant Cell Environ. 1995;18:523–533. [Google Scholar]

- Benveniste I, Tijet N, Adas F, Philips G, Salaun JP, Durst F. CYP86A1 from Arabidopsis thaliana encodes a cytochrome P450-dependent fatty acid omega-hydroxylase. Biochim Biophys Res Commun. 1998;243:688–693. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.8156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolwell GP, Bozak K, Zimmerlin A. Plant cytochrome P450. Phytochemistry. 1994;37:1491–1506. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(00)89567-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabello-Hurtado F, Batard Y, Salaün JP, Durst F, Pinot F, Werck-Reichhart D. Cloning, expression in yeast and functional characterization of CYP81B1, a plant P450 which catalyzes in-chain hydroxylation of fatty acids. J Biol Chem. 1998a;273:7260–7267. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.13.7260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabello-Hurtado F, Durst F, Jorrin JV, Werck-Reichhart, D (1998b) Coumarins in Helianthus tuberosus: characterization, induced accumulation and biosynthesis. Phytochemistry (in press)

- Cabello-Hurtado F, Zimmerlin A, Rahier A, Taton M, DeRose R, Nedelkina S, Batard Y, Durst F, Pallett KE, Werck-Reichhart D. Cloning and functional expression in yeast of a cDNA coding for an obtusifoliol 14α-demethylase (CYP51) in wheat. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;230:381–385. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.5873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl AR, Hodgson E. The interaction of aliphatic analogs of methylenedioxyphenyl compounds with cytochrome P-450 and P-420. Chem Biol Interact. 1979;27:163–175. doi: 10.1016/0009-2797(79)90123-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickins M, Elcombe CR, Moloney SJ, Netter KJ, Bridges JW. Further studies on the dissociation of the isosafrole metabolite-cytochrome P450 complex. Biochem Pharmacol. 1979;28:231–238. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(79)90509-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paiva RAN, Dixon L. Stress-induced phenylpropanoid metabolism. Plant Cell. 1995;7:1085–1097. doi: 10.1105/tpc.7.7.1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baillieul SF, Pierrel M, Dorey A, Saindrenan P, Fritig B, Kauffmann S. Spatial and temporal induction of cell death, defense genes, and accumulation of salicylic acid in tobacco leaves reacting hypersensitively to a fungal glycoprotein elicitor. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 1997;10:646–655. [Google Scholar]

- Duggleby RG. Regression analysis of nonlinear Arrhenius plots: an empirical model and a computer program. Comput Biol Med. 1984;14:447–455. doi: 10.1016/0010-4825(84)90045-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durst F, O'Keefe D. Plant cytochromes P450s: an overview. Drug Metab Drug Interact. 1995;12:171–187. doi: 10.1515/dmdi.1995.12.3-4.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elcombe CR, Bridges JW, Gray TJB, Ninno-Smith RH, Netter KJ. (1975) Studies on the interaction of safrole with rat hepatic microsomes. Biochem Pharmacol 24: 1427–1433

- Fischer MT, Sligar SG. Temperature jump relaxation kinetics of the P450cam spin equilibrium. Biochemistry. 1987;26:4797–4803. doi: 10.1021/bi00389a029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin MR. The enzymic formation of a methylenedioxyphenyl derivative exhibiting an isocyanide-like spectrum with reduced cytochrome P450 in hepatic microsomes. Xenobiotica. 1971;1:581–591. doi: 10.3109/00498257109112269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin MR. Inhibition of mixed-function oxidations by substrates forming reduced cytochrome P-450 metabolic-intermediate complexes. Pharmacol Ther A. 1977;2:227–245. [Google Scholar]

- Franklin MR. Cytochrome P450 metabolic intermediate complexes from macrolide antibiotics and related compounds. Methods Enzymol. 1991;206:559–573. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)06126-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritig B, Hirth L, Ourisson G. Biosynthesis of the coumarins: scopoletin formation in tobacco tissue cultures. Phytochemistry. 1970;9:1963–1975. [Google Scholar]

- Funk C, Brodelius PE. Phenylpropanoid metabolism in suspension cultures of Vanillia planifolia Andr. II. Effects of precursor feeding and metabolic inhibitors. Plant Physiol. 1990;94:95–101. doi: 10.1104/pp.94.1.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabriac B, Werck-Reichhart D, Teusch H, Durst F. Purification and immunocharacterisation of a plant cytochrome P450: the cinnamic acid 4-hydroxylase. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1991;288:302–309. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(91)90199-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez-Mellado MC, Edwards R, Tena M, Cabello F, Serghini K, Jorrin J. The production of coumarin phytoalexins in different plant organs of sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.) J Plant Physiol. 1996;149:261–266. [Google Scholar]

- Helms V, Deprez E, Gill E, Barret C, Hui Bon Hoa G, Wade RC. Improved binding of cytochrome P450cam substrate analogues designed to fill extra space in the substrate binding pocket. Biochemistry. 1996;35:1485–1499. doi: 10.1021/bi951817l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgson E, Philipot RM. Interaction of methylenedioxyphenyl (1,3-benzodioxole) compounds with enzymes and their effects on mammals. Drug Metab Rev. 1974;3:231–301. doi: 10.3109/03602537408993744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgson E, Philpot RM, Baker RC, Mailman RB. Effect of synergists on drug metabolism. Drug Metab Dispos. 1973;1:391–401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jefcoate CR. Measurement of substrate and inhibitor binding to microsomal cytochrome P450 by optical-difference spectroscopy. Methods Enzymol. 1978;52:258–279. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(78)52029-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusukawa M, Iwamura H. N-(3,4-Methylendioxyphenyl) carbamates as potent flowering-inducing compounds in Asparagus seedlings as well as probes for binding to cytochrome P450. Z Naturforsch. 1995;50c:373–379. [Google Scholar]

- Mansuy D, Battioni JP, Chottard JC, Ullrich V. Preparation of a porphyrin-iron-carbene model for the cytochrome P450 complexes obtained upon metabolic oxidation of insecticide synergists of the 1,3-benzodioxole series. J Am Chem Soc. 1979;101:3971–3973. [Google Scholar]

- Murray M, Wilkinson CF, Marcus C, Dubé CE. Mol Pharmacol. 1993;24:129–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagata T, Nemoto Y, Hasezawa S. Tobacco BY-2 cell line as the “Hela” cell in the biology of higher plants. Int Rev Cytol. 1992;132:1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Omura R, Sato R. The carbon monoxide binding pigment of liver microsomes. I. Evidence for its hemoprotein nature. J Biol Chem. 1964;239:2370–2378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz de Montellano PR, Correia MA (1995) Inhibition of cytochrome P450 enzymes. In PR Ortiz de Montellano, ed, Cytochrome P450: Structure, Mechanism, and Biochemistry, Ed 2. Plenum Press, New York, pp 305–364

- Pierrel MA, Batard Y, Kazmaier M, Mignotte-Vieux C, Durst F, Werck-Reichhart D. Catalytic properties of the plant cytochrome P450 CYP73 expressed in yeast: substrate specificity of a cinnamate hydroxylase. Eur J Biochem. 1994;224:835–844. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.00835.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raag R, Poulos TL. The structural basis for substrate-induced changes in redox potential and spin equilibrium in cytochrome P450CAM. Biochemistry. 1989;28:917–922. doi: 10.1021/bi00428a077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichhart D, Salaün JP, Benveniste I, Durst F. Time course of induction of cytochrome P450, NADPH-cytochrome c reductase, and cinnamic acid hydroxylase by phenobarbital, ethanol, herbicides, and manganese in higher plant microsomes. Plant Physiol. 1980;66:600–604. doi: 10.1104/pp.66.4.600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichheld JP, Sonobe S, Clement B, Chaubet N, Gigot C. Cell cycle-regulated histone gene expression in synchronized plant cells. Plant J. 1995;7:245–252. [Google Scholar]

- Schalk M, Batard Y, Seyer A, Nedel'kina S, Durst F, Werck-Reichhart D. Naphthoic acids, alternate fluorescent substrates or inhibitors of CYP73A1, a plant cinnamate 4-hydroxylase. Biochemistry. 1997;36:15253–15261. doi: 10.1021/bi971575k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuler MA. Plant cytochrome P450 monooxygenases. Crit Rev Plant Sci. 1996;15:235–284. [Google Scholar]

- Sewalt VJH, Ni W, Blount JW, Jung HG, Masoud SA, Howles PA, Lamb C, Dixon RA. Reduced lignin content and altered lignin composition in transgenic tobacco down-regulated in expression of l-phenylalanine ammonia-lyase or cinnamate 4-hydroxylase. Plant Physiol. 1997;115:41–50. doi: 10.1104/pp.115.1.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman RB. Mechanism-based enzyme inactivators. In: Purich DL, editor. Contemporary Enzyme Kinetics and Mechanism, Ed 2. San Diego: Academic Press; 1996. pp. 291–334. [Google Scholar]

- Tal B, Robeson DJ. Phytochemistry. 1986;25:77–79. [Google Scholar]

- Teutsch GH, Hasenfratz MP, Lesot A, Stoltz C, Garnier JM, Jeltsch JM, Durst F, Werck-Reichhart D. Isolation and sequence of a cDNA encoding the Jerusalem artichoke cinnamate 4-hydroxylase, a major plant cytochrome P450 involved in the general phenylpropanoid pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:4102–4106. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.9.4102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truan G, Collin C, Reisdorf P, Urban P, Pompon D. Enhanced in vivo monooxygenase activities of mammalian P450s in engineered yeast cells producing high levels of NADPH-P450 reductase and human cytochrome b5. Gene. 1993;125:49–55. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90744-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urban P, Werck-Reichhart D, Teusch HG, Durst F, Mignotte C, Katzmaier M, Pompon D. Characterization of a recombinant plant cinnamate 4-hydroxylase produced in yeast: kinetic and spectral properties of the major plant P450 of the phenylpropanoid pathway. Eur J Biochem. 1994;222:843–850. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.tb18931.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varsano R, Rabinovitch HD, Rubin B. Mode of action of piperonyl butoxide as herbicide synergist of atrazine and terbutryn in maize. Pestic Biochem Physiol. 1992;44:174–182. [Google Scholar]

- Werck-Reichhart D. Cytochromes P450 in phenylpropanoid metabolism. Drug Metab Drug Interact. 1995;12:221–243. doi: 10.1515/dmdi.1995.12.3-4.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werck-Reichhart D, Gabriac B, Teusch H, Durst F. Two cytochromes P450 isoforms catalyzing O-dealkylation of ethoxycoumarin and ethoxyresorufin in higher plants. Biochem J. 1990;270:719–735. doi: 10.1042/bj2700729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson CF, Murray M, Marcus CB. Interactions of methylenedioxyphenyl compounds with cytochrome P450 and effects on microsomal oxidation. In: Hodgson E, Bend JR, Philipot RM, editors. Reviews in Biochemical Toxicology, Vol 6. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 1984. pp. 27–63. [Google Scholar]

- Yalpani N, León J, Lawton MA, Raskin I. Pathway of salicylic acid biosynthesis in healthy and virus-inoculated tobacco. Plant Physiol. 1993;103:315–321. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.2.315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson LHCF, Anders M, Yu W. Generation of carbon monoxide during the microsomal metabolism of methylenedioxyphenyl compounds. Biochem Pharmacol. 1980;29:1113–1122. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(80)90405-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]