Abstract

Phenotypic and functional alterations in Mycobacterium tuberculosis T cell subsets have been reported in patients with active tuberculosis. A better understanding of these alterations will increase the knowledge about immunopathogenesis and also may contribute to the development of new diagnostics and prophylactic strategies. Here, the ex vivo phenotype of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and the frequency and phenotype of gamma interferon (IFN-γ)- and interleukin 17 (IL-17)-producing cells elicited in short-term and long-term cultures following CFP-10 and purified protein derivative (PPD) stimulation were determined in noninfected persons (non-TBi), latently infected persons (LTBi), and patients with active tuberculosis (ATB). Phenotypic characterization of T cells was done based on the expression of CD45RO and CD27. Results show that ATB had a reduced frequency of circulating CD4+ CD45RO+ CD27+ T cells and an increased frequency of CD4+ CD45RO− CD27+ T cells. ATB also had a higher frequency of circulating IL-17-producing CD4+ T cells than did LTBi after PPD stimulation, whereas LTBi had more IFN-γ-producing CD4+ T cells than did non-TBi. The phenotype of IFN-γ-producing cells at 24 h differs from the phenotype of IL-17-producing cells with no differences between LTBi and ATB. At 144 h, IFN-γ- and IL-17-producing cells were mainly CD45RO+ CD27+ T cells and they were more frequent in ATB. These results suggest that M. tuberculosis infection induces alterations in T cells which interfere with an adequate specific immune response.

INTRODUCTION

Tuberculosis (TB) remains a major public health problem and one of the most important infectious diseases worldwide, causing 8.8 million incident cases and 1.3 million deaths in 2010 (76). Approximately one-third of the world population is considered to be latently infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis; although most of them contain the infection, remaining asymptomatic for decades or even throughout their entire life span, approximately 10% of these infected persons will develop active disease (72).

Successful host defense against M. tuberculosis requires an effective coordination of the innate and adaptive immune responses. The adaptive immune response is characterized by the expansion and differentiation of several T effector cells (e.g., Th1, Th17, Th2, and regulatory T cells [Tregs]) and the generation of long-lived memory T cells with an enhanced capacity to respond upon reexposure to mycobacteria (12, 59). Th1 responses play an important role in the defense against M. tuberculosis by inducing macrophage microbicidal mechanisms and thereby restricting mycobacterial growth (30, 39). Impairment of Th1 responses by genetic mutations in the gamma interferon (IFN-γ)/interleukin 12 (IL-12) axis (48), anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha (anti-TNF-α) treatment for autoimmune diseases (34), and HIV infection (22) increases the risk of developing active TB. M. tuberculosis can also induce Th17 responses, and although their role is less well understood, Th17 cells are also considered important in M. tuberculosis resistance by participating in granuloma formation (49, 73) and by increasing the recruitment of IFN-γ-producing cells into the lungs (35). However, due to their proinflammatory role and their capacity to induce recruitment of granulocytes into infected tissues, Th17 cells may also play a deleterious role in the necrosis of granulomas, resulting in the reactivation of latent infections (13). Thus, since IFN-γ and IL-17 may have opposite roles during M. tuberculosis infection, a balance between Th1 and Th17 responses is essential to promote an effective anti-M. tuberculosis immune response and prevent tissue damage.

Although many studies have evaluated the contributions of Th1 and Th17 cells to the immune response against M. tuberculosis infection (20, 49, 52), it is crucial to further understand their role during different stages of M. tuberculosis infection, as well as their phenotypic and functional characteristics after exposure to mycobacterial antigens.

The generation of immunological memory is the hallmark of the adaptive immune response (59). CD4+ and CD8+ memory T cell subsets can be distinguished by the expression of different phenotypic markers, homing properties, and functional capacities (7, 51). Memory T cells are classically identified by the expression of CD45RO, the low-molecular-weight isoform of CD45 which, along with other surface markers, defines different stages of differentiation of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. CD27 is a costimulatory molecule belonging to the TNF family expressed in all CD4+ naïve cells and in more than 80% of CD4+ memory cells (15, 24). A loss of CD27 expression has been proposed to be characteristic of induced effector CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (21, 56). CD27-negative cells are suggested to be a more differentiated subset with a higher capacity to secrete cytokines and a stronger recall response than those of the CD27+ population (61).

TB is a chronic, infectious disease, and prolonged exposure to mycobacterial antigens affects the biology of antigen-specific T cells (71), including the generation of memory T cells. Most of the studies focusing on T cell memory profiles in TB (27, 33, 75) analyze the phenotypes of circulating T cells ex vivo or after short-term in vitro stimulation. These studies show that the responding cells are mainly T effector memory (TEM) or T effector (TEF) cells (8, 46, 75). However, there are not many studies addressing this issue in long-term cultures, where central memory T (TCM) cells should be the main responders (6, 25, 41), and even fewer studies comparing the phenotypes of antigen-specific T cells responding to in vitro stimulation with mycobacterial antigens in both short- and long-term cultures. Phenotypic characterization of Th1 and Th17 cells has shown that IFN-γ and IL-17 are produced by T cell subsets with different phenotypes following short-term in vitro stimulation with Mycobacterium bovis BCG (62) or mycobacterial antigens (52). In these studies, IFN-γ-producing cells displayed an effector or effector memory phenotype, while IL-17-producing cells were mainly central memory cells, suggesting that IFN-γ- and IL-17-producing cells are long-lived memory cells actively involved in the immune response to M. tuberculosis infection.

Since in active tuberculosis, antigen-specific T cells are exposed to persistent antigenic stimulation, it is possible to suggest that the profile, magnitude, and phenotype of antigen-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells producing IFN-γ or IL-17 should be differentially affected in latently infected and active-TB individuals. For these reasons, the frequencies of ex vivo naïve, effector, and memory CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, as well as the frequencies and phenotypes of IFN-γ- and IL-17-producing cells elicited after stimulation with specific mycobacterial antigens, were determined in latently infected individuals (LTBi) and patients with active TB (ATB). The results show that ATB had a reduced frequency of circulating TCM CD4+ cells (CD45RO+ CD27+) and an increased frequency of Tearly/naïve cells (CD45RO− CD27+). ATB patients had a higher frequency of IL-17-producing CD4+ T cells after in vitro stimulation with purified protein derivative (PPD), while LTBi had a higher frequency of IFN-γ-producing CD4+ T cells after CFP-10 and PPD stimulation. Despite the reduced frequency of circulating CD4+ TCM cells in ATB, they were the highest producers of IFN-γ and IL-17 after long-term stimulation with CFP-10. These results suggest that M. tuberculosis infection alters the in vivo generation of M. tuberculosis-specific memory T cells and causes a shift in the protective Th1 profile toward a Th17 response: these events are related to a reduced protective response against M. tuberculosis and also with an exacerbated inflammatory response which may favor the reactivation of active disease in latently infected individuals.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population.

Forty-three newly diagnosed patients with active TB (ATB) (9 females and 34 males, aged 38 ± 14 years old) were recruited at the Tuberculosis Control Program in Medellín (Colombia) and its metropolitan area. ATB patients had positive sputum smears for acid-fast bacillus (AFB; 1+, 12 patients; 2+, 14 patients; 3+, 12 patients; no data, 5 patients) and were studied before or within the first 2 weeks of anti-TB treatment. Four ATB patients were also studied after they finished their 6-month anti-TB therapy, and all of them were cured as indicated by a negative AFB smear and a recovery from the clinical symptoms once they finished therapy. Thirty-five healthy subjects with latent TB infection (LTBi) (24 females and 11 males, aged 31 ± 16 years old) were selected according to an IFN-γ-positive response to CFP-10, as evaluated by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) in 7-day whole-blood culture supernatants, as previously reported by our group (16). Fifteen individuals with a negative response to CFP-10 were included as a noninfected control group (non-TBi) (10 females and 5 males, aged 35 ± 14 years old). Individuals from non-TBi and LTBi groups were healthy without clinical evidence of active tuberculosis. Individuals infected with HIV, using immunosuppressive drugs, with diabetes, or younger than 15 years old were excluded. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Instituto de Investigaciones Médicas of the Universidad de Antioquia, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Antigens.

Recombinant ESAT-6 and CFP-10 were provided by the Department of Microbiology and Immunology of Colorado State University (Fort Collins, CO) through the Tuberculosis Vaccine Testing and Research Material contract no. HHSN26266400091C (NIH, NIAID, N01-AI-40091). PPD (RT50) was obtained from the State Serum Institute (Copenhagen, Denmark). Irradiated M. tuberculosis was obtained from BEI Resources (Manassas, VA).

Sample preparation.

Twenty milliliters of peripheral blood was obtained using heparin as anticoagulant, and the peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were obtained by Ficoll-Hypaque density gradient centrifugation (BioWhittaker, Walkersville, MD). Viability, as tested by trypan blue exclusion, was always ≥95%.

Cell phenotyping, cell cultures, and intracellular cytokine analysis.

The phenotype of CD4+ and CD8+ T cell subsets was evaluated by the surface expression of CD45RO and CD27 on fresh whole blood and cultured cells (19, 22, 38). For the ex vivo analysis, 100 μl of whole blood was lysed with Optilyse (Beckman Coulter) according to the manufacturer's instructions and blocking buffer (2% pooled human serum [BioWhittaker] plus 0.01% NaN3 in phosphate-buffered saline [PBS]) was added for 15 min at 4°C with light protection. The antibody panel for ex vivo analysis included anti-CD4-peridinin chlorophyll protein (PerCP)-Cy5 (clone OKT4), anti-CD8-Pacific blue (clone OKT8) (eBioscience, San Diego, CA), anti-CD27-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) (clone 0323), and anti-CD45RO-allophycocyanin (APC) (clone UCHL-1) (Biolegend, San Diego, CA). In some experiments, cells were stained with 7-amino-actinomycin D (7-AAD) along with CD27 and CD45RO in order to evaluate the viability of T cells in long-term cultures and less than 1% of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were 7-AAD positive. Stained cells were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde (J. T. Baker, Phillipsburg, NJ), and 1 × 105 cells were acquired in a fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) Canto II flow cytometer (BD Bioscience, San Diego, CA).

For the 24-h whole-blood cultures (short term), heparinized blood was diluted 1:10 in 1 ml of RPMI 1640 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with penicillin-streptomycin (BioWhittaker, Walkersville, MD) plus 1 μg/ml of anti-CD28/anti-CD49d (BD Bioscience). For 144-h cultures (long term), PBMC were plated at 1 × 105 cells/well in triplicate in 96-well round-bottomed plates in complete culture medium (RPMI 1640 plus 10% pooled human serum [BioWhittaker] and penicillin-streptomycin). Both 24-h and 144-h cultures were stimulated with CFP-10 (5 μg/ml), PPD (10 μg/ml), or M. tuberculosis (10 μg/ml), and nonstimulated cultures were used as negative controls. Four hours before the end of incubation, supernatants were collected and brefeldin A (10 μg/ml) was added to the cultures. At the end of the incubation, red cells from the whole-blood cultures were lysed with Optilyse (Beckman Coulter). Cells from 24 h and 144 h were stained for surface markers and fixed as described for ex vivo assays. Fixed cells were permeabilized followed by incubation with anti-IFN-γ–phycoerythrin (PE)–Cy7 (clone B27) (Biolegend) and anti-IL-17–PE (clone eBios64CAP17) (eBioscience). One hundred thousand cells were acquired in a FACS Canto II flow cytometer and analyzed using BD FACSDiva software, v6.1.2 (BD Bioscience, San Jose, CA), or FlowJo software, v7.6.1 (Tree Star Inc., Ashland, OR). Data analysis was performed by selecting singlets in a forward scatter A (FSC-A)/FSC-H dot plot, followed by the selection of lymphocytes in an FSC-A/side scatter A (SSC-A) dot plot, and then CD4 or CD8 was plotted versus SSC. To identify the phenotype of cytokine-producing cells, IFN-γ- and IL-17-producing gated CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were evaluated for the expression of CD27 and CD45RO (see Fig. 3A and B).

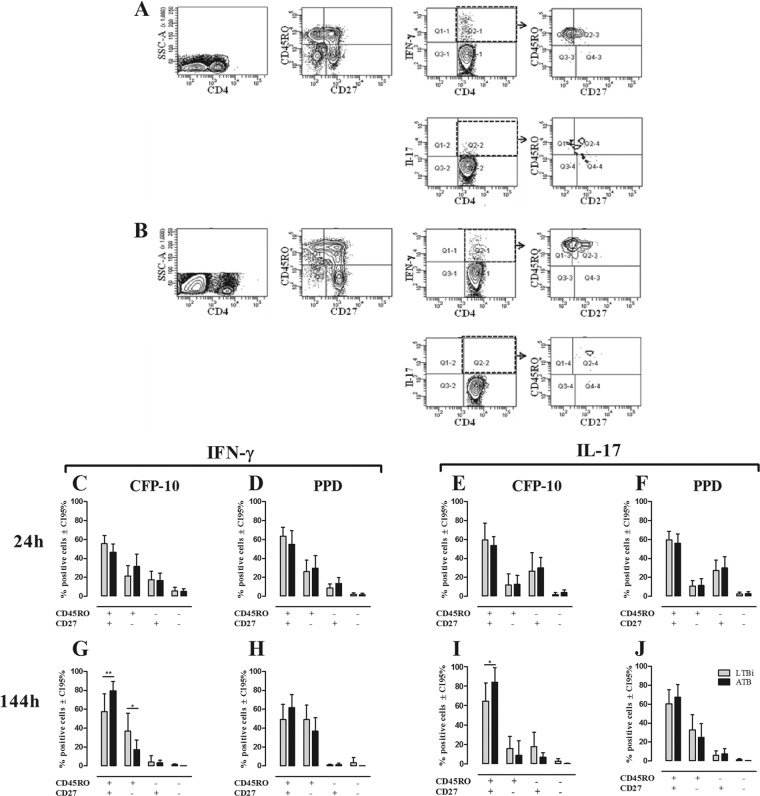

Fig 3.

Phenotypes of IFN-γ- and IL-17-producing CD4+ T cells in non-TBi, LTBi, and ATB individuals. The phenotypes of IFN-γ- and IL-17-producing CD4+ T cells were evaluated based on the expression of CD45RO and CD27 as described in Materials and Methods. One representative example of the gating strategy used to evaluate the phenotypes of IFN-γ+ and IL-17+ CD4+ T cells from whole-blood 24-h (A) and PBMC 144-h (B) cultures stimulated with CFP-10 from one ATB is shown. The phenotypes of IFN-γ (C, D, G, and H)- and IL-17 (E, F, I, and J)-producing CD4+ T cells from 24-h whole-blood (C to F) and 144-h PBMC (G to J) cultures stimulated with CFP-10 (C, E, G, and I) and PPD (D, F, H, and J) were evaluated by the expression of CD27 and CD45RO. Gray bars, LTBi; black bars, ATB. Two-way ANOVA test with Bonferroni's posttest: *, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.01.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 5 (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA). Comparisons between three or more groups were done by the Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn's multiple comparison test. A two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) test with Bonferroni's posttest was used to compare means of the T cell subsets among the studied groups. Pearson's correlation coefficient was done and is specified in each case in the figure legend. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Memory phenotypes of CD4+ and CD8+ cells.

In order to determine the combination of surface markers that allows well-defined T cell subsets, CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from fresh blood and PBMC stimulated for 24 h with PPD were analyzed for the expression of CCR7, CD62L, CD27, and CD45RO. Based on the expression pattern of these surface molecules, CD27 and CD45RO were selected to identify CD4+ and CD8+ T cell subsets (data not shown). Thus, the combined use of CD45RO along with CD27 defined four subsets of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells: CD45RO+ CD27+, CD45RO+ CD27−, CD45RO− CD27+, and CD45RO− CD27−, which, according to previous reports by other authors, would correspond to TCM, TEM, Tearly/naïve, and TEF cells, respectively (5, 19, 38, 69). Representative dot plots of the ex vivo expression of CD45RO and CD27 on CD4+ and CD8+ T cells are shown in Fig. 1A and B.

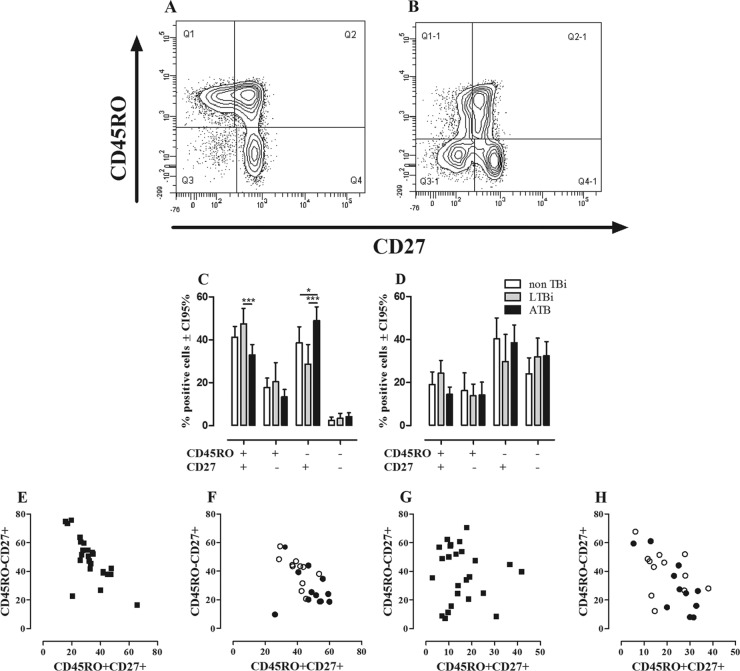

Fig 1.

Ex vivo phenotypes of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. The phenotypes of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from non-TBi, LTBi, and ATB were evaluated according to the expression of CD45RO and CD27 as described in Materials and Methods. A representative example of the expression of CD45RO and CD27 on CD4 (A) and CD8 (B) T cells from one LTBi is shown. Frequencies of CD4+ (C) and CD8+ (D) T cells from non-TBi (n = 12) (white bars), LTBi (n = 11) (gray bars), and ATB (n = 24) (black bars). Two-way ANOVA test with Bonferroni's posttest: *, P ≤ 0.05; ***, P ≤ 0.001. Pearson's correlation coefficient between the percentages of CD4+ CD45RO+ CD27+ and CD4+ CD45RO− CD27+ T cells from ATB (r = −0.7317, P = 0.0001) (E) and non-TBi (white circles) (Pearson r = −0.7417; P = 0.0058) and LTBi (black circles) (Pearson r = −0.2190; P = 0.5176) (F). Correlations between CD8+ CD45RO+ CD27+ and CD8+ CD45RO− CD27+ T cells in ATB (Pearson r = −0.0844; P = 0.6947) (G) and non-TBi (Pearson r = −0.3545; P = 0.2581) and LTBi (Pearson r = −0.7951; P = 0.0034) (H).

Ex vivo evaluation of CD27 and CD45RO expression in non-TBi, LTBi, and ATB showed that CD4+ and CD8+ T cells have different profiles regarding the proportion of cells expressing CD45RO and CD27. There was a very low frequency of CD45RO− CD27− cells among CD4+ T cells compared to the CD8+ T cells (Fig. 1C and D), irrespective of the group studied. Among CD4+ T cells, the subsets expressing CD27 were more frequent than the subsets lacking CD27 expression, regardless of the expression of CD45RO (Fig. 1C), while among CD8+ T cells, there was a higher proportion of cells lacking the CD45RO expression, regardless of the expression of CD27 (Fig. 1D). Comparative analysis of these subsets among non-TBi, LTBi, and ATB showed that ATB had a lower frequency of CD4+ CD45RO+ CD27+ T cells (P ≤ 0.001) than did LTBi and also a higher frequency of CD4+ CD45RO− CD27+ T cells than those for non-TBi (P ≤ 0.05) and LTBi (P ≤ 0.001), but no differences were observed between non-TBi and LTBi (Fig. 1C). Regarding CD8+ T cells, there were no differences in the percentages of these subsets among the studied groups (Fig. 1D).

To evaluate whether the reduced frequency of CD4+ CD45RO+ CD27+ T cells observed in ATB is associated with changes in the other T cell subsets, correlation analyses were done. In ATB, the frequency of CD4+ CD45RO+ CD27+ memory T cells correlated negatively with the frequency of CD4+ CD45RO− CD27+ T cells (Pearson r = −0.7317; P = 0.0001) (Fig. 1E). A similar pattern was also found in non-TBi (Pearson r = −0.7417; P = 0.0058) but not in LTBi (Pearson r = −0.2190; P = 0.5176) (Fig. 1F). Regarding CD8+ T cells, the frequency of CD8+ CD45RO+ CD27+ T cells negatively correlated with the frequency of CD8+ CD45RO− CD27+ T cells in LTBi (Pearson r = −0.7951; P = 0.0034) but not in non-TBi (Fig. 1H) (Pearson r = −0.3545; P = 0.2581) nor in ATB (Pearson r = −0.0844; P = 0.6947) (Fig. 1G). These results show that active TB causes a reduction in the percentage of circulating TCM cells, while there is an increase of circulating Tearly/naïve cells, which may occur as a compensatory mechanism to balance the proportion of circulating T cell subsets.

Evaluation of IFN-γ- and IL-17-producing cells in 24-h and 144-h cultures from non-TBi, LTBi, and ATB individuals.

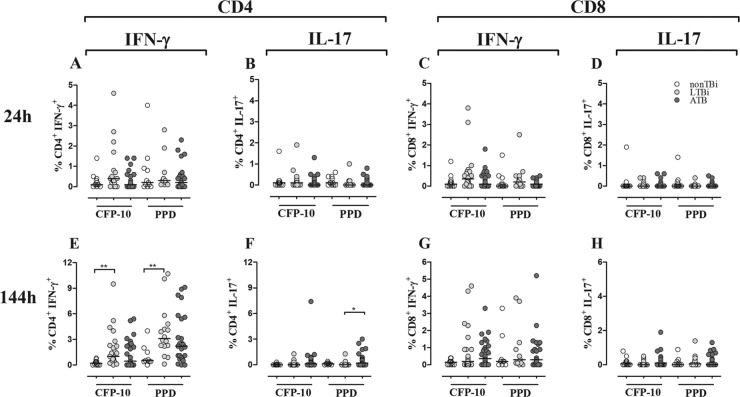

Th1 and Th17 seem to have opposite roles during active TB (71); thus, low Th1 and high Th17 responses have been previously reported in patients with active TB in long-term and short-term cultures, respectively (57, 74). Therefore, the frequency of IFN-γ- and IL-17-producing CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in response to mycobacterial antigens was determined in 24-h whole-blood and 144-h PBMC cultures stimulated or not with CFP-10 and PPD. There was a negligible percentage of IFN-γ- and IL-17-producing CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in both 24-h and 144-h cultures from non-TBi. At 24 h, there were not significant differences in the frequencies of IFN-γ- and IL-17-producing CD4+ T cells among non-TBi, LTBi, and ATB in response to CFP-10 or PPD (Fig. 2A and B). At 144 h, LTBi had a higher frequency of CD4+ IFN-γ+ T cells in response to CFP-10 and PPD than did non-TBi (P ≤ 0.01) (Fig. 2E). No differences were observed between ATB and non-TBi or LTBi regardless of the antigen used (Fig. 2E). With respect to IL-17-producing cells, at 144 h ATB had a higher frequency of CD4+ IL-17+ T cells than did LTBi in response to PPD (P ≤ 0.05) (Fig. 2F). There were no differences between non-TBi and LTBi groups in the percentages of IL-17-producing cells at this time point. Regarding CD8+ T cells, the frequencies of IFN-γ- or IL-17-producing CD8+ T cells were not different in response to CFP-10 and PPD among the studied groups (Fig. 2C and D and 2G and H). These results suggest that evaluation of IFN-γ and IL-17 responses in 24-h whole-blood cultures did not discriminate infected from noninfected persons. However, in 144-h PBMC cultures, the IFN-γ production elicited after CFP-10 and PPD stimulation discriminated infected from noninfected individuals, while the high production of IL-17 was a characteristic of ATB patients.

Fig 2.

Frequencies of IFN-γ- and IL-17-producing CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in non-TBi, LTBi, and ATB individuals. CD4+ (A, B, E, and F) and CD8+ (C, D, G, and H) T cells from 24-h whole blood (A to D) and 144-h PBMC (E to H) cultures stimulated with CFP-10 and PPD were intracellularly stained with anti-IFN-γ–PE–Cy7 (A, C, E, and G) and anti-IL-17–PE (B, D, F, and H). The frequencies of IFN-γ- and IL-17-producing CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were evaluated in non-TBi (white circles), LTBi (gray circles), and ATB (black circles). Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn's multiple comparison test: *, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.01.

Memory phenotypes of IFN-γ- and IL-17-producing cells in short- and long-term cultures from non-TBi, LTBi, and ATB individuals.

Studies addressing the contributions of different subsets of effector and memory CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in ATB and LTBi to the recall response against mycobacterial antigens have been done, and differences in the memory phenotypes of responding cells have been reported (23, 46, 62). Therefore, considering the phenotypic and functional features of the effectors and memory T cells established above, we speculated that the phenotype of IFN-γ- and IL-17-producing cells should be different in short- and long-term cultures from LTBi and ATB. Thus, phenotypic characterization of IFN-γ- and IL-17-producing CD4+ and CD8+ T cells was done by evaluating the expression of CD45RO and CD27 in cells from 24-h and 144-h cultures stimulated with CFP-10 and PPD. One representative example of the gating strategy for the phenotypic and functional evaluation of CD4+ T cells stimulated for 24 h (Fig. 3A) or 144 h (Fig. 3B) with CFP-10 is shown. In short-term cultures (24 h) stimulated with CFP-10 (Fig. 3C) or PPD (Fig. 3D), IFN-γ-producing CD4+ T cells showed a heterogeneous phenotype, although CD45RO+ CD27+ T cells were the main producers, followed by CD45RO+ CD27− and CD45RO− CD27+ T cells and a negligible percentage of CD45RO− CD27− T cells. IL-17 was mainly produced by CD4+ CD27+ T cells, irrespective of the CD45RO expression, with approximately 60% of the IL-17+ cells exhibiting the CD45RO+ CD27+ phenotype (Fig. 3E and F). At this time point, no significant differences were observed between LTBi and ATB regarding the frequency of each CD4+ T cell subset producing IFN-γ or IL-17 in response to CFP-10 and PPD (Fig. 3C to F).

In long-term cultures (144 h), both CFP-10 and PPD induced IFN-γ and IL-17 production mainly by CD4+ CD45RO+ CD27+ T cells, although CD4+ CD45RO+ CD27− also contributed to IFN-γ production (Fig. 3G to J). In response to CFP-10, ATB had a higher frequency of IFN-γ- and IL-17-producing CD4+ CD45RO+ CD27+ T cells compared to LTBi (Fig. 3G and I), whereas ATB showed a lower frequency of IFN-γ-producing CD4+ CD45RO+ CD27− T cells than did LTBi (Fig. 3G).

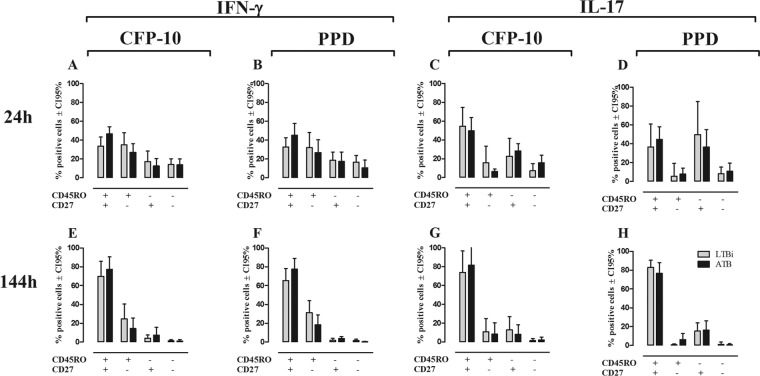

Regarding CD8+ T cells (Fig. 4), in short-term cultures all the cell subsets produced IFN-γ (Fig. 4A and B), while IL-17, similar to CD4+ T cells, was produced mainly by CD27+ T cells, either CD45RO+ or CD45RO− (Fig. 4C and D). No differences were observed in the phenotypes of IFN-γ- and IL-17-producing CD8+ T cells between LTBi and ATB in response to CFP-10 or PPD (Fig. 4A to D). In long-term cultures, IFN-γ and IL-17 were mainly produced by CD45RO+ CD27+ CD8+ T cells, without statistically significant differences between the studied groups after CFP-10 or PPD stimulation (Fig. 4E to H). These results show differences in the phenotypes of IFN-γ and IL-17 after short-term stimulation with mycobacterial antigens, since IFN-γ was basically produced by CD45RO+ T cells while IL-17 was mainly produced by CD27+ T cells. However, after long-term in vitro stimulation, both of them were produced almost exclusively by central memory CD45RO+ CD27+ T cells, with a higher frequency of this subset producing IFN-γ and IL-17 in ATB after CFP-10 stimulation.

Fig 4.

Phenotypes of IFN-γ- and IL-17-producing CD8+ T cells in non-TBi, LTBi, and ATB individuals. The phenotypes of IFN-γ (A, B, E, and F)- and IL-17 (C, D, G, and H)-producing CD8+ T cells from 24-h whole-blood (A to D) and 144-h PBMC (E to H) cultures after stimulation with CFP-10 (A, C, E, and G) and PPD (B, D, F, and H) were evaluated by the expression of CD27 and CD45RO. Gray bars, LTBi; black bars, ATB. Two-way ANOVA test with Bonferroni's posttest.

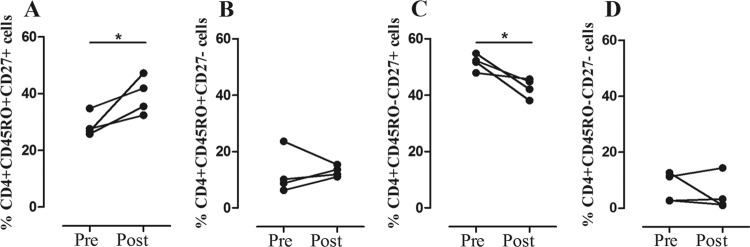

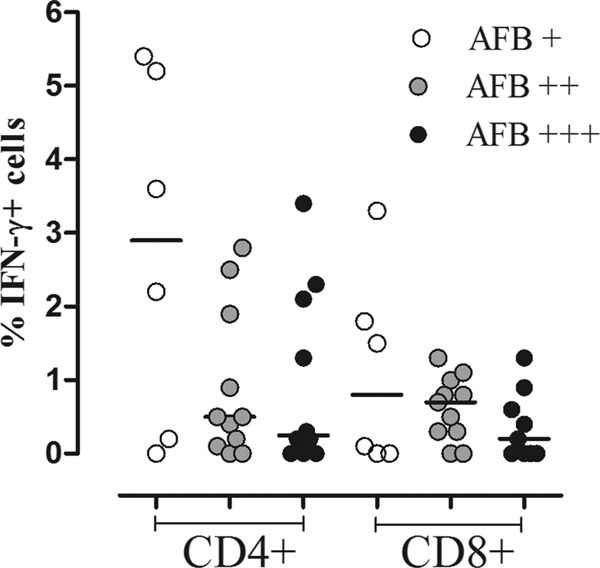

Recent evidence suggests that the profile and magnitude of the antimycobacterial immune response in ATB correlate with pathogen load, and its reduction after completion of the anti-TB therapy impacts the profile and magnitude of cytokine response (1, 9, 45). However, the frequency of ex vivo CD4+ and CD8+ T cells with different phenotypes did not show any relationship with AFB positivity in sputum smears in our TB patients (data not shown). Nevertheless, there was a trend toward lower numbers of IFN-γ-producing CD4+ and CD8+ T cells with increasing AFB smear sputum positivity in 144-h cultures stimulated with CFP-10 (Fig. 5). Furthermore, the ex vivo phenotypes of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and the frequencies of IFN-γ- and IL-17-producing CD4+ and CD8+ T cells following stimulation with CFP-10 were evaluated in four cured TB patients, and the results were compared with the pretreatment measurements. In all patients, there was an increase in the frequency of circulating CD4+ CD45RO+ CD27+ T cells (P ≤ 0.05) (Fig. 6A) and a decrease in frequency of CD4+ CD45RO− CD27+ T cells (P ≤ 0.05) (Fig. 6C) after the completion of their anti-TB therapy. No changes were observed in the frequencies of CD4+ CD45RO+ CD27− (Fig. 6B) and CD4+ CD45RO− CD27− cells (Fig. 6D) or in the frequencies of the four CD8+ T cell subsets (data not shown). Likewise, the frequencies of IFN-γ- and IL-17-producing CD4+ and CD8+ T cells evaluated at 24 h and 144 h following stimulation with CFP-10 and PPD diminished in ATB after anti-TB treatment, but the change did not reach statistical significance. These results show that the functional response of CD4+ or CD8+ T cells seems to be affected by the bacterial load and also that an effective anti-TB therapy restores the immunological components which were altered during the active disease, thus recovering the immune homeostasis.

Fig 5.

Frequencies of IFN-γ-producing CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in ATB with different AFB smear values. PBMC from ATB were stimulated for 144 h with CFP-10 and then evaluated for the frequency of IFN-γ-producing cells as described in Materials and Methods. Frequencies of IFN-γ-producing CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in patients with AFB smear values of 1+ (white circles), 2+ (gray circles), and 3+ (black circles). Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn's multiple comparison test.

Fig 6.

Phenotypic changes in T cells associated with anti-TB therapy. Ex vivo frequencies of CD4+ CD45RO+ CD27+ (A), CD4+ CD45RO+ CD27− (B), CD4+ CD45RO− CD27+ (C), and CD4+ CD45RO− CD27− (D) T cells in four ATB patients before and after anti-TB treatment. Paired Student's t test: *, P ≤ 0.05.

DISCUSSION

This study shows alterations in the phenotypes of circulating CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and the frequencies and phenotypes of IFN-γ- and IL-17-producing CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in patients with active tuberculosis. A special feature of our study is that short-term (24-h) whole-blood and long-term (144-h) PBMC cultures were compared. Because in short-term cultures there is not enough time for cellular division, their evaluation has been considered an ex vivo measurement of the host's immune status, and cytokines produced in these cultures are considered to be produced mainly by effector cells or effector memory T cells (25, 26, 41). Conversely, long-term assays (5 to 7 days) allow the evaluation of antigen-specific memory T cells expanded after stimulation with the cognate antigen. In addition, long-term assays have been reported to be more sensitive and specific in detecting latent infection than short-term cultures, especially in areas where TB is endemic (6, 10, 25).

Alterations in the frequencies of circulating memory T cells have been reported in ATB (31, 46, 75). Most of these studies have been carried out ex vivo or after short-term in vitro stimulation with mycobacterial antigens (31, 62, 75). Here, identification of ex vivo and short- and long-term cultured CD4+ and CD8+ memory phenotypes was done using the combination of CD45RO with CD27. Four subsets of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were defined: CD45RO+ CD27−, CD45RO+ CD27+, CD45RO− CD27−, and CD45RO− CD27+, which, according to previous reports and their expression pattern on the T cell subsets, would correspond to TEM, TCM, TEF, and Tearly/naïve cells, respectively (19, 22, 38, 69). It is noteworthy that among CD8+ T cells, a particular subset known as TEMRA (effector memory CD45RA+) expressing CD45RA, but not CD27 (64), overlaps with the CD45RO− CD27− subset described in our study (N. D. Marín, Y. M. Ortiz, S. C. París, M. Rojas, and L. F. García, in preparation). Thus, the presence of TEMRA cells among CD8+ T cells may explain the increased frequency of CD8+ CD45RO− CD27− T cells compared to CD4+ T cells, although no differences in this specific subset were found among the studied groups.

The analysis of the phenotype of circulating CD4+ T cells showed a decreased frequency of TCM CD45RO+ CD27+ T cells and a higher frequency of CD45RO− CD27+ T cells in ATB than in LTBi. The frequencies of these subsets showed a negative correlation between them, not found with the other subsets, suggesting that the generation of CD45RO− CD27+ and CD45RO+ CD27+ T cells is a dynamic process where the increase of the first one could be a compensatory mechanism for the reduced frequency of TCM CD4+ CD45RO+ CD27+ T cells observed in ATB. This finding and the irreversible loss of CD27 expression associated with terminal effector T cell differentiation (28) would support the idea that CD45RO− CD27+ T cells might be direct precursors of CD45RO+ CD27+ T cells and that the latter would give rise to CD45RO+ CD27− TEM and terminally differentiated or effector CD45RO− CD27− T cells. Decreased frequency of TCM (CD45RO+ CD27+) has been also reported in children (31) and adults (75) with active TB. However, although there are many studies addressing the phenotypic characterization of T cell subsets in TB, the mechanism(s) underlying the reduced frequency of memory T cells in TB is still poorly understood.

Prolonged exposure to antigen has been associated with defective generation of TCM by induction of effector and exhausted cells (40, 65). Since TB is a chronic infection where T cells are constantly exposed to mycobacterial antigens, it is possible to hypothesize that this persistent, chronic stimulation may explain the decreased TCM cells observed in TB. In this regard, we found that the frequency of CD4+ CD45RO+ CD27+ T cells was restored in ATB after the completion of their anti-TB treatment, while the frequency of CD4+ CD45RO− CD27+ T cells was reduced. These changes may be related to an effective control of the infection with low levels of antigens available to activate antigen-specific T cells, thus favoring generation of TCM cells, as previously proposed (40).

The importance of memory T cells in M. tuberculosis infection has been clearly demonstrated in mice, but in humans its role is less clear. In mice, the generation of memory T cells correlates with an increased recall response and enhanced protection after M. tuberculosis infection (33, 63). However, in humans its role is controversial and the only anti-TB vaccine available, BCG, does not induce an effective memory T cell response, showing variable protection among human populations, since it seems to be effective only in protecting children from severe forms of TB (3). In addition, the observation that cured TB patients may become reinfected and suffer active TB further supports the idea that anti-M. tuberculosis memory T cells are not protective in TB. Despite this, the generation of memory T cells is the basis for the development of the new TB vaccines that would protect against M. tuberculosis and help to control its spread around the world, mainly in areas of high endemicity.

In addition to the phenotypic evaluation of T cells, we also evaluated the functional capacity of mycobacterial antigen-specific T cells from ATB, non-TBi, and LTBi to produce IFN-γ or IL-17 after stimulation with mycobacterial antigens. IFN-γ has been considered the most important cytokine in the defense against M. tuberculosis infection, and its production in response to mycobacterium-specific antigens has been used as a correlate of protection (2, 17, 58). However, at the moment there is a consensus that IFN-γ is necessary but not sufficient to protect against M. tuberculosis infection in humans (42, 66). In fact, our group and others have shown that high levels of IFN-γ are associated with susceptibility to developing ATB in recently exposed contacts (16, 29); therefore, it is important to study the role of other cytokines or immune components that may help to elucidate the immune profiles associated with susceptibility to or protection from TB. Here, we evaluated the frequency of IFN-γ- and IL-17-producing cells in short- and long-term cultures. We, as well as others (60), did not find differences in the frequencies of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells producing these cytokines in response to CFP-10 and PPD in short-term cultures among non-TBi, LTBi, and ATB. However, it is important to mention that non-TBi had the lowest response in all cases.

Unlike short-term cultures, in long-term cultures the proportion of IFN-γ+ CD4+ T cells was higher in LTBi in response to both CFP-10 and PPD than it was in non-TBi. Although LTBi tend to show a high proportion of CD4+ IFN-γ+ T cells compared to that in ATB, our results and those of others did not show significant differences in the frequency of IFN-γ-producing cells between them (60, 68). Our group, however, using PBMC cultures supplemented with autologous serum and after in vitro restimulation at 120 h of culture, has previously reported a lower frequency of IFN-γ-producing cells in ATB than in LTBi after stimulation with specific mycobacterial antigens or PPD (55, 57). The clinical heterogeneity of ATB as shown by the AFB sputum results ranging from 1+ to 3+ may explain the high variability found in the specific response to CFP-10 and PPD in this group. Additionally, the time of exposure of TB contacts to the index case (16, 68) and the M. tuberculosis strains infecting the patients may also impact the IFN-γ response (54).

Th17 cells producing IL-17 seem to play opposite roles in early and late stages of M. tuberculosis infection. During early stages of M. tuberculosis infection, IL-17-producing cells are suggested to be important in granuloma formation, favoring defense against M. tuberculosis infection when IL-12 is absent and also by accelerating the recruitment of IFN-γ-producing CD4+ T cells into the lungs (35, 36, 49, 73). However, a pathogenic role of Th17 cells in later stages of the M. tuberculosis infection has also been proposed. IL-17 has been implicated in induction and recruitment of neutrophils into the lungs (47, 73) through the induction of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) and IL-8 (37, 44). Neutrophils in TB have been mainly associated with the development of pathology by increasing the local inflammation and granuloma necrosis which favors M. tuberculosis replication and dissemination (18, 70). Thus, given the dual role played by Th17 cells in early and late stages of M. tuberculosis infection and its particular interaction with Th1 cells, the cross-regulation of these two T cell subsets is critical for the control of bacterial growth and tissue damage. In this regard, and similarly to previous studies (68, 74), we found a higher frequency of IL-17-producing CD4+ T cells in ATB than in LTBi after long-term in vitro stimulation with PPD.

These results suggest that by increasing IL-17 production, M. tuberculosis may cause a decreased production of IFN-γ during active disease; however, it may also occur that a reduction in IFN-γ production may favor the expansion of IL-17-producing cells. In this regard, IFN-γ regulates the development of Th17 cells (14, 47), and in TB, this may be a mechanism to control the immunopathology associated with Th17 during mycobacterial infections (14, 47, 67). Moreover, we and others have previously reported that IL-17-producing cells are less sensitive to Treg-mediated suppression than are IFN-γ-producing cells following stimulation with mycobacterial antigens (4, 43). Thus, the change of Th1 toward a nonprotective Th17 profile may exacerbate the inflammation in the lungs by favoring the recruitment of neutrophils. These events hamper adequate control of M. tuberculosis, worsen the prognosis of TB, and may also promote the reactivation of TB in latently infected persons.

The inhibition of an M. tuberculosis-specific response has been associated with the bacterial load and the severity of the disease (11, 32, 53). In concordance with these studies, we found an inverse relationship between the frequency of IFN-γ-producing cells and the severity of the disease as measured by the AFB smear, although it did not reach statistical significance. Furthermore, effective anti-TB therapy has also been associated with a reduction in the frequency of antigen-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells producing IFN-γ (1, 9, 45). Analysis of the immune response before and after anti-TB therapy showed a trend toward a reduction in the frequency of IFN-γ- and IL-17-producing CD4+ and CD8+ T cells elicited by stimulation with CFP-10 and PPD, in both short- and long-term cultures. Therefore, dynamic changes in the frequencies of IFN-γ- and IL-17-producing cells could be used as an immunological correlate of bacterial load and may also be used to evaluate the efficiency of anti-TB therapy.

Regarding the phenotype of IFN-γ- and IL-17-producing cells in short-term cultures, both TCM and TEM CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were the main producers of IFN-γ, followed by CD45RO− CD27+ T cells, whereas CD45RO− CD27− T cells had the lowest contribution to the production of both IFN-γ and IL-17. It should be noted that unlike IFN-γ-producing cells, IL-17-producing cells were mainly CD27+ T cells, suggesting a differential requirement of this costimulatory molecule in the production of this cytokine after stimulation with specific antigens. Pepper et al. (50) found that IFN-γ- and IL-17-producing cells have differential expression of CD27 in a model of infection with Listeria monocytogenes, but unlike our results, they reported that IL-17-producing cells were mainly short-lived CD27− T cells. In addition, Scriba et al. (62), based on the expression of CD45RA, CCR7, and CD27, found that after short-term in vitro stimulation, IL-17-producing cells were mainly central memory cells, whereas IFN-γ-producing cells were predominantly effector cells. However, our finding that an important percentage of IL-17-producing cells are CD45RO− CD27+ may suggest that T cells in the early differentiation stages are capable of producing this cytokine.

Long-term cultures are reported to detect mainly memory T cell responses (10, 41), and in this regard, we found that both CD4+ and CD8+ TCM (CD45RO+ CD27+) cells were the major subset producing both IFN-γ and IL-17. Despite the reduced frequency of CD4+ CD45RO+ CD27+ T cells found ex vivo in ATB, the high proportion of TCM cells producing IFN-γ and IL-17 in ATB after long-term stimulation suggests that although TCM differentiation may be impaired in ATB, due to the persistent mycobacterial stimulation, they are still able to proliferate and produce cytokines after stimulation with mycobacterial antigens in vitro. Of note, the percentages of CD4+ and CD8+ dead cells, as determined by FasL, annexin V, and 7-AAD staining, were always very low in long-term cultures, and there were no differences between LTBi and ATB (data not shown), suggesting that the differences in the cytokine responses observed in long-term cultures were not due to increased cell death.

Altogether, these results demonstrate that M. tuberculosis infection alters the generation of memory T cells and the functional profile of T cells by biasing the protective Th1 profile toward the pathological Th17 response during active disease, which could exacerbate the immune-related pathology. Despite the reduction of TCM cells, this T cell subset was functionally able to produce more IFN-γ and IL-17 than were memory cells from latently infected individuals after long-term stimulation with specific mycobacterial antigens. These findings provide a better understanding of immunological alterations occurring during active TB that could be used for the development of new diagnostic and therapeutic strategies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the TB patients and noninfected and latently infected individuals who consented to participate in this study and the Tuberculosis Control Programs of the Servicio Seccional de Salud de Antioquia and the Secretaria de Salud de Medellín, who contributed in the recruitment of the patients and allowed us to have access to the clinical records of the patients. We also thank Thomas J. Scriba and Andrés Baena for their critical reading of the manuscript.

This study was supported by Colciencias (Bogotá, Colombia) grant 1115-408-20488 and Estrategia de Sostenibilidad (Comité para el Desarrollo de la Investigación, CODI; Universidad de Antioquia). N.D.M. is the recipient of a predoctoral scholarship from Colciencias, Bogotá, Colombia.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 22 August 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Adetifa IM, et al. 2010. Decay kinetics of an interferon gamma release assay with anti-tuberculosis therapy in newly diagnosed tuberculosis cases. PLoS One 5:e12502 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0012502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Agger EM, Andersen P. 2001. Tuberculosis subunit vaccine development: on the role of interferon-gamma. Vaccine 19:2298–2302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Andersen P, Doherty TM. 2005. The success and failure of BCG—implications for a novel tuberculosis vaccine. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3:656–662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Annunziato F, et al. 2007. Phenotypic and functional features of human Th17 cells. J. Exp. Med. 204:1849–1861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Appay V, van Lier RA, Sallusto F, Roederer M. 2008. Phenotype and function of human T lymphocyte subsets: consensus and issues. Cytometry A 73:975–983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Beveridge NE, et al. 2008. A comparison of IFNgamma detection methods used in tuberculosis vaccine trials. Tuberculosis (Edinb.) 88:631–640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Beverley PC. 1992. Functional analysis of human T cell subsets defined by CD45 isoform expression. Semin. Immunol. 4:35–41 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Caccamo N, et al. 2009. Analysis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis-specific CD8 T-cells in patients with active tuberculosis and in individuals with latent infection. PLoS One 4:e5528 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0005528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 9. Casey R, et al. 2010. Enumeration of functional T-cell subsets by fluorescence-immunospot defines signatures of pathogen burden in tuberculosis. PLoS One 5:e15619 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0015619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cehovin A, Cliff JM, Hill PC, Brookes RH, Dockrell HM. 2007. Extended culture enhances sensitivity of a gamma interferon assay for latent Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 14:796–798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chen X, et al. 2010. Reduced Th17 response in patients with tuberculosis correlates with IL-6R expression on CD4+ T cells. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 181:734–742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cooper AM, Khader SA. 2008. The role of cytokines in the initiation, expansion, and control of cellular immunity to tuberculosis. Immunol. Rev. 226:191–204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cooper AM, Solache A, Khader SA. 2007. Interleukin-12 and tuberculosis: an old story revisited. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 19:441–447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cruz A, et al. 2006. Cutting edge: IFN-gamma regulates the induction and expansion of IL-17-producing CD4 T cells during mycobacterial infection. J. Immunol. 177:1416–1420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. De Jong R, et al. 1992. The CD27- subset of peripheral blood memory CD4+ lymphocytes contains functionally differentiated T lymphocytes that develop by persistent antigenic stimulation in vivo. Eur. J. Immunol. 22:993–999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. del Corral H, et al. 2009. IFNgamma response to Mycobacterium tuberculosis, risk of infection and disease in household contacts of tuberculosis patients in Colombia. PLoS One 4:e8257 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0008257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ellner JJ, Hirsch CS, Whalen CC. 2000. Correlates of protective immunity to Mycobacterium tuberculosis in humans. Clin. Infect. Dis. 30(Suppl 3):S279–S282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Eum SY, et al. 2010. Neutrophils are the predominant infected phagocytic cells in the airways of patients with active pulmonary TB. Chest 137:122–128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fallen PR, et al. 2003. Identification of non-naive CD4+CD45RA+ T cell subsets in adult allogeneic haematopoietic cell transplant recipients. Bone Marrow Transplant. 32:609–616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Flynn JL, et al. 1993. An essential role for interferon gamma in resistance to Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. J. Exp. Med. 178:2249–2254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fritsch RD, et al. 2005. Stepwise differentiation of CD4 memory T cells defined by expression of CCR7 and CD27. J. Immunol. 175:6489–6497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Geldmacher C, et al. 2010. Preferential infection and depletion of Mycobacterium tuberculosis-specific CD4 T cells after HIV-1 infection. J. Exp. Med. 207:2869–2881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Goletti D, et al. 2006. Region of difference 1 antigen-specific CD4+ memory T cells correlate with a favorable outcome of tuberculosis. J. Infect. Dis. 194:984–992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hamann D, et al. 1997. Phenotypic and functional separation of memory and effector human CD8+ T cells. J. Exp. Med. 186:1407–1418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hanekom WA, et al. 2008. Immunological outcomes of new tuberculosis vaccine trials: WHO panel recommendations. PLoS Med. 5:e145 doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0050145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hanekom WA, et al. 2004. Novel application of a whole blood intracellular cytokine detection assay to quantitate specific T-cell frequency in field studies. J. Immunol. Methods 291:185–195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Henao-Tamayo MI, et al. 2010. Phenotypic definition of effector and memory T-lymphocyte subsets in mice chronically infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 17:618–625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hendriks J, et al. 2000. CD27 is required for generation and long-term maintenance of T cell immunity. Nat. Immunol. 1:433–440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Higuchi K, Harada N, Fukazawa K, Mori T. 2008. Relationship between whole-blood interferon-gamma responses and the risk of active tuberculosis. Tuberculosis (Edinb.) 88:244–248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Jacobs M, et al. 2007. Tumor necrosis factor is critical to control tuberculosis infection. Microbes Infect. 9:623–628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Jacobsen M, et al. 2007. Clonal expansion of CD8+ effector T cells in childhood tuberculosis. J. Immunol. 179:1331–1339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Jurado JO, et al. 2012. IL-17 and IFN-gamma expression in lymphocytes from patients with active tuberculosis correlates with the severity of the disease. J. Leukoc. Biol. 91:991–1002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kamath A, Woodworth JS, Behar SM. 2006. Antigen-specific CD8+ T cells and the development of central memory during Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. J. Immunol. 177:6361–6369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Keane J, et al. 2001. Tuberculosis associated with infliximab, a tumor necrosis factor alpha-neutralizing agent. N. Engl. J. Med. 345:1098–1104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Khader SA, et al. 2007. IL-23 and IL-17 in the establishment of protective pulmonary CD4+ T cell responses after vaccination and during Mycobacterium tuberculosis challenge. Nat. Immunol. 8:369–377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Khader SA, et al. 2005. IL-23 compensates for the absence of IL-12p70 and is essential for the IL-17 response during tuberculosis but is dispensable for protection and antigen-specific IFN-gamma responses if IL-12p70 is available. J. Immunol. 175:788–795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kolls JK, Linden A. 2004. Interleukin-17 family members and inflammation. Immunity 21:467–476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kwa D, Vingerhoed J, Boeser-Nunnink B, Broersen S, Schuitemaker H. 2001. Cytopathic effects of non-syncytium-inducing and syncytium-inducing human immunodeficiency virus type 1 variants on different CD4(+)-T-cell subsets are determined only by coreceptor expression. J. Virol. 75:10455–10459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lalvani A, Millington KA. 2008. T cells and tuberculosis: beyond interferon-gamma. J. Infect. Dis. 197:941–943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lanzavecchia A, Sallusto F. 2005. Understanding the generation and function of memory T cell subsets. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 17:326–332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Leyten EM, et al. 2007. Discrepancy between Mycobacterium tuberculosis-specific gamma interferon release assays using short and prolonged in vitro incubation. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 14:880–885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Majlessi L, et al. 2006. An increase in antimycobacterial Th1-cell responses by prime-boost protocols of immunization does not enhance protection against tuberculosis. Infect. Immun. 74:2128–2137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Marin ND, et al. 2010. Regulatory T cell frequency and modulation of IFN-gamma and IL-17 in active and latent tuberculosis. Tuberculosis (Edinb.) 90:252–261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. McKenzie BS, Kastelein RA, Cua DJ. 2006. Understanding the IL-23-IL-17 immune pathway. Trends Immunol. 27:17–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Millington KA, et al. 2007. Dynamic relationship between IFN-gamma and IL-2 profile of Mycobacterium tuberculosis-specific T cells and antigen load. J. Immunol. 178:5217–5226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Mueller H, et al. 2008. Mycobacterium tuberculosis-specific CD4+, IFNgamma+, and TNFalpha+ multifunctional memory T cells coexpress GM-CSF. Cytokine 43:143–148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Nandi B, Behar SM. 2011. Regulation of neutrophils by interferon-gamma limits lung inflammation during tuberculosis infection. J. Exp. Med. 208:2251–2262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Newport MJ, et al. 1996. A mutation in the interferon-gamma-receptor gene and susceptibility to mycobacterial infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 335:1941–1949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Okamoto Yoshida Y, et al. 2010. Essential role of IL-17A in the formation of a mycobacterial infection-induced granuloma in the lung. J. Immunol. 184:4414–4422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Pepper M, et al. 2010. Different routes of bacterial infection induce long-lived TH1 memory cells and short-lived TH17 cells. Nat. Immunol. 11:83–89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Picker LJ, et al. 1995. Direct demonstration of cytokine synthesis heterogeneity among human memory/effector T cells by flow cytometry. Blood 86:1408–1419 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Qiao D, et al. 2011. ESAT-6- and CFP-10-specific Th1, Th22 and Th17 cells in tuberculous pleurisy may contribute to the local immune response against Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Scand. J. Immunol. 73:330–337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Qiu Z, et al. 2012. Multifunctional CD4 T cell responses in patients with active tuberculosis. Sci. Rep. 2:216 doi:10.1038/srep00216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Rakotosamimanana N, et al. 2010. Variation in gamma interferon responses to different infecting strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in acid-fast bacillus smear-positive patients and household contacts in Antananarivo, Madagascar. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 17:1094–1103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Riano F, et al. 2012. T cell responses to DosR and Rpf proteins in actively and latently infected individuals from Colombia. Tuberculosis (Edinb.) 92:148–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Romero P, et al. 2007. Four functionally distinct populations of human effector-memory CD8+ T lymphocytes. J. Immunol. 178:4112–4119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Rueda CM, Marin ND, Garcia LF, Rojas M. 2010. Characterization of CD4 and CD8 T cells producing IFN-gamma in human latent and active tuberculosis. Tuberculosis (Edinb.) 90:346–353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Sahiratmadja E, et al. 2007. Dynamic changes in pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokine profiles and gamma interferon receptor signaling integrity correlate with tuberculosis disease activity and response to curative treatment. Infect. Immun. 75:820–829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Sallusto F, Geginat J, Lanzavecchia A. 2004. Central memory and effector memory T cell subsets: function, generation, and maintenance. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 22:745–763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Sargentini V, et al. 2009. Cytometric detection of antigen-specific IFN-gamma/IL-2 secreting cells in the diagnosis of tuberculosis. BMC Infect. Dis. 9:99 doi:10.1186/1471-2334-9-99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Schiott A, Lindstedt M, Johansson-Lindbom B, Roggen E, Borrebaeck CA. 2004. CD27- CD4+ memory T cells define a differentiated memory population at both the functional and transcriptional levels. Immunology 113:363–370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Scriba TJ, et al. 2008. Distinct, specific IL-17- and IL-22-producing CD4+ T cell subsets contribute to the human anti-mycobacterial immune response. J. Immunol. 180:1962–1970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Serbina NV, Flynn JL. 2001. CD8(+) T cells participate in the memory immune response to Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect. Immun. 69:4320–4328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Shen T, et al. 2010. PD-1 expression on peripheral CD8+ TEM/TEMRA subsets closely correlated with HCV viral load in chronic hepatitis C patients. Virol. J. 7:310 doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-7-310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Shin H, Wherry EJ. 2007. CD8 T cell dysfunction during chronic viral infection. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 19:408–415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Soares AP, et al. 2008. Bacillus Calmette-Guerin vaccination of human newborns induces T cells with complex cytokine and phenotypic profiles. J. Immunol. 180:3569–3577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Stumhofer JS, Silver J, Hunter CA. 2007. Negative regulation of Th17 responses. Semin. Immunol. 19:394–399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Sutherland JS, de Jong BC, Jeffries DJ, Adetifa IM, Ota MO. 2010. Production of TNF-alpha, IL-12(p40) and IL-17 can discriminate between active TB disease and latent infection in a West African cohort. PLoS One 5:e12365 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0012365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Tapaninen P, Korhonen A, Pusa L, Seppala I, Tuuminen T. 2010. Effector memory T-cells dominate immune responses in tuberculosis treatment: antigen or bacteria persistence? Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 14:347–355 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Torrado E, Cooper AM. 2010. IL-17 and Th17 cells in tuberculosis. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 21:455–462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Torrado E, Robinson RT, Cooper AM. 2011. Cellular response to mycobacteria: balancing protection and pathology. Trends Immunol. 32:66–72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Tufariello JM, Chan J, Flynn JL. 2003. Latent tuberculosis: mechanisms of host and bacillus that contribute to persistent infection. Lancet Infect. Dis. 3:578–590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Umemura M, et al. 2007. IL-17-mediated regulation of innate and acquired immune response against pulmonary Mycobacterium bovis bacille Calmette-Guerin infection. J. Immunol. 178:3786–3796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Wang T, et al. 2011. Increased frequencies of T helper type 17 cells in tuberculous pleural effusion. Tuberculosis (Edinb.) 91:231–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Wang X, et al. 2010. Association of mycobacterial antigen-specific CD4(+) memory T cell subsets with outcome of pulmonary tuberculosis. J. Infect. 60:133–139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. World Health Organization 2011. Global tuberculosis control: WHO report 2011. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland [Google Scholar]