Abstract

Helicobacter pylori infection is associated with gastritis and gastric cancer. An H. pylori virulence factor, the cag pathogenicity island (PAI), is related to host cell cytokine induction and gastric inflammation. Since elucidation of the mechanisms of inflammation is important for therapy, the associations between cytokines and inflammatory diseases have been investigated vigorously. Levels of interleukin-32 (IL-32), a recently described inflammatory cytokine, are increased in various inflammatory diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis and Crohn's disease, and in malignancies, including gastric cancer. In this report, we examined IL-32 expression in human gastric disease. We also investigated the function of IL-32 in activation of the inflammatory cytokines in gastritis. IL-32 expression paralleled human gastric tissue pathology, with low IL-32 expression in H. pylori-uninfected gastric mucosa and higher expression levels in gastritis and gastric cancer tissues. H. pylori infection increased IL-32 expression in human gastric epithelial cell lines. H. pylori-induced IL-32 expression was dependent on the bacterial cagPAI genes and on activation of nuclear factor κB (NF-κB). IL-32 expression induced by H. pylori was not detected in the supernatant of AGS cells but was found in the cytosol. Expression of the H. pylori-induced cytokines CXCL1, CXCL2, and IL-8 was decreased in IL-32-knockdown AGS cell lines compared to a control AGS cell line. We also found that NF-κB activation was decreased in H. pylori-infected IL-32-knockdown cells. These results suggest that IL-32 has important functions in the regulation of cytokine expression in H. pylori-infected gastric mucosa.

INTRODUCTION

The relationships between microbial infections, inflammatory disorders, and cancer have been investigated extensively, and these associations are now widely accepted, owing partly to the discovery of Helicobacter pylori (5, 19). H. pylori was first isolated from gastritis patients in 1983 by Warren and Marshall (52). Gastric inflammation caused by H. pylori infection increases the risk of gastric cancer, a common cause of cancer death worldwide (8, 42, 51). One of the virulence factors responsible for the progression of gastric diseases is the cag pathogenicity island (PAI) of H. pylori, a cluster of approximately 30 genes. H. pylori and its cagPAI genes are associated with severe gastric diseases, including gastric cancer and gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma (29, 40).

H. pylori cagPAI activates nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathways in infected epithelial cells. NF-κB is a transcription factor that regulates various cellular responses, including inflammation, cell survival or death, and cell proliferation. NF-κB activation induces the production of inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-1β (IL-1β), IL-8, and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α). IL-8, which is induced by H. pylori infection via NF-κB activation in gastric epithelial cells, plays a critical role in gastritis and gastric carcinogenesis (6, 39, 49). IL-8 causes neutrophil infiltration into gastric tissue, which elicits additional inflammation. In Japanese populations, a single polymorphism in the IL-8 gene is associated with upregulation of IL-8 and with an increased risk of atrophic gastritis and gastric cancer (50). Similarly, polymorphisms in the IL-1β and TNF-α genes have been associated with gastritis and gastric cancer (9, 47).

The importance of understanding inflammation was recently highlighted. First, particular cytokines induced in inflammatory diseases, for example, TNF-α, which leads to the sequential release of cytokines and causes inflammatory reactions, are good therapeutic targets. Antibodies used for anti-TNF therapy have been shown to control rheumatoid arthritis and Crohn's disease (34). Also, the identification and elimination of pathogens in inflammatory disease have decreased the incidence of inflammation-associated cancer. Indeed, some studies on H. pylori have shown that eradication therapy reduces the risk of gastric cancer (10, 38, 53).

IL-32, formerly called NK-4, is a newly described inflammatory cytokine and is reported to induce the production of several other cytokines, such as TNF-α and IL-1 (7, 23). IL-32 does not share sequence homology with other cytokines, and no homolog has been found in rodents. Previous reports showed that IL-32 expression is increased in various inflammatory diseases, and it is involved in the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis and Crohn's disease (14, 44, 45). IL-32 expression is induced by hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, and Mycobacterium tuberculosis (3, 32, 35, 41). Furthermore, IL-32 expression is associated with several malignancies, including lung cancer, pancreatic cancer, and gastric cancer (22, 36, 46).

The mechanisms underlying IL-32 expression in gastric tissues, as well as the roles of IL-32 in the development of gastric disease, have not been clarified fully. In this study, we investigated IL-32 expression in H. pylori-infected gastric epithelial cells. We further examined the association of IL-32 and other inflammatory cytokines induced in gastritis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Human gastric tissue samples.

Gastric tissues from patients were obtained from the archives of the University of Tokyo Hospital and Motojima General Hospital, with the approval of the medical ethics committee and with informed consent. H. pylori-induced gastritis was defined by positive H. pylori test results, a rapid urease test (Helicocheck; Otsuka Pharmaceuticals, Tokyo, Japan), and microscopic verification. Healthy gastric mucosa was defined by the absence of pathological inflammation and a negative result for the H. pylori test.

Cell lines.

Three gastric cancer cell lines, AGS, TMK-1, and MKN45, were described previously (15, 30, 31). AGS cells were maintained in Ham's F-12 medium (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). TMK-1 and MKN45 cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium (Sigma) containing 10% FBS.

Helicobacter pylori strains.

H. pylori strain TN2, which is positive for cagPAI, was maintained in brucella broth under microaerobic conditions. TN2 isogenic cagPAI-negative and cagE-negative mutants (TN2-ΔcagPAI and TN2-ΔcagE, respectively) were constructed as described previously (39). In coculture experiments, H. pylori was washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), resuspended in Ham's F-12 medium (Sigma), and used in the assays. The bacterium-to-cell ratio was approximately 100:1 in all assays.

Reagents.

Recombinant human IL-1β, recombinant human TNF-α, and recombinant IL-32β were purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). Chemical inhibitors of IKKβ (SC-514) and p38 (SB203580) were purchased from Merck (Nottingham, United Kingdom). SC-514 and SB203580 were dissolved in 4% dimethyl sulfoxide and added to 12-well plates at a concentration of 20 μM 1 h before H. pylori infection.

Plasmids.

The luciferase reporter plasmids −133-IL-8-Luc (a gift from K. Matsushima), pNF-κB-Luc (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA), and pRL-TK (Promega, Madison, WI) were described previously (1, 31). pSilencer vectors (Ambion, Austin, TX) encoding small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) for IL-32 were constructed using previously reported sequences (3). Two siRNA sequences were used, generating pSi-IL-32-6 and pSi-IL-32-7. The IL-32 expression vector (pcDNA-IL-32β) was constructed by cloning IL-32β cDNA into the pcDNA3.1 vector (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Full-length IL-32β was amplified by reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) from RNA obtained from AGS cells infected with H. pylori and then was sequenced. For IL-32 rescue experiments, a mutant IL-32β expression vector (pcDNA-mIL32β) was generated by mutagenesis. We constructed primers to insert three mutations in the target sequence of pSi-IL-32-6, and mutagenesis was performed on pcDNA-IL-32β by use of a QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Immunoblotting and immunoprecipitation.

Cells were disrupted in lysis buffer (20 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 1% Triton X [Sigma], 2.5 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 1 mM glycerophosphate, 1 mM Na3VO4, 1 μg/ml leupeptin). CagA immunoprecipitation was performed as described previously (16). Cell lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, United Kingdom), and blocked for 1 h with Tris-buffered saline–Tween (TBST) plus 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA). The membrane was incubated overnight at 4°C with the primary antibody and subsequently washed and incubated with a secondary horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated antibody. The immunocomplexes were detected with an Immunostar LD instrument (Wako, Tokyo, Japan). Images were obtained using an LAS 3000 image analyzer (Fujifilm, Tokyo, Japan). The primary antibodies used for immunoblotting were anti-human IL-32 (R&D), anti-human β-actin (Sigma), anti-urease (Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, CA), anti-phospho-IκBα (Ser32) (Cell Signaling, Beverly, MA), anti-phospho-c-Jun N-terminal kinase (anti-phospho-JNK) (Cell Signaling), anti-phospho-p38 (Cell Signaling), anti-phosphotyrosine (PY99) (Santa Cruz), and anti-CagA (16) antibodies.

Immunohistochemistry.

IL-32 expression in human gastric tissues was examined immunohistochemically. Formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded gastric specimens were cut at a thickness of 3 μm and deparaffinized. Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked using 3% H2O2. The primary anti-IL-32 antibody (KU32-52; BioLegend, San Diego, CA) was added, and the tissue sections were incubated overnight. For the secondary antibody, the tissues were exposed to Histofine Simple Stain Max PO (Nichirei, Tokyo, Japan) for 30 min. Mouse IgG1 isotype antibody (R&D) was used as the negative control.

IL-32 expression in AGS cells was examined by immunofluorescence staining. AGS cells were seeded into four-well chamber slides (Nalge Nunc International, Naperville, IL) and infected with H. pylori for 24 h. The cells were washed with PBS, fixed with 3% paraformaldehyde for 30 min, incubated with 0.5% Triton X (Sigma) for 10 min, and then blocked with 2% BSA for 10 min. IL-32 antibody (KU32-52) was added and incubated overnight. Cells were incubated with Alexa Fluor 555-conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) for 30 min, and the nuclei were visualized by staining with Hoechst 33342 (TaKaRa, Tokyo, Japan) for 1 min.

ELISA.

IL-32, IL-8, CXCL1, CXCL2, and TNF-α levels in culture supernatants or cell lysates were quantitated by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). IL-32 levels were measured as described previously (22). KU32-56 (BioLegend) was used as the capture antibody, and biotinylated KU32-52 (BioLegend) was used as the detection antibody. IL-8, CXCL1, and TNF-α levels were measured with Quantikine ELISA kits (R&D) according to the manufacturer's protocol. CXCL2 levels were measured with a human CXCL2 assay kit (IBL, Gunma, Japan).

Cloning and sequencing.

Cloning and sequence analysis were conducted to identify IL-32 isoforms in human gastritis tissue. Total RNAs were extracted from human gastric tissues from H. pylori-positive gastritis patients by use of a NucleoSpin RNA II kit (TaKaRa), and cDNAs were synthesized from 1 μg of RNA by use of the ImProm-II reverse transcription system (Promega). The full-length coding region of IL-32 cDNA was amplified by PCR and cloned into the TOPO TA cloning vector (Invitrogen). Plasmid DNAs from 20 colonies were sequenced using an ABI Prism 310 genetic analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA).

Real-time RT-PCR.

Total cellular RNA samples were isolated from AGS cells by use of a NucleoSpin RNA II kit (TaKaRa). cDNAs were generated from 1 μg of total RNA by reverse transcription using the ImProm-II reverse transcription system (Promega). The mRNA expression levels of total IL-32, IL-32β, IL-8, CXCL1, CXCL2, TNF-α, IL-11, and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) were determined by quantitative real-time RT-PCR, using an ABI Prism 7000 quantitative PCR system (Applied Biosystems). GAPDH mRNA was used as the internal control. The primer sequences used are available on request.

RNA interference.

siRNAs for IKKβ (5′-GGUGAAGAGGUGGUGGUGAGC-3′) and IL-8 (Qiagen, Chatsworth, CA) were used. The siRNAs or the nonsilencing control (5′-AATTCTCCGAACGTGTCACGT-3′) was transfected by use of Lipofectamine RNAimax (Invitrogen) for 48 h, and cells were infected with H. pylori for the indicated times.

Construction of stable cell lines.

To establish IL-32-knockdown stable cell lines and a control cell line, AGS cells were transfected with pSi-IL-32-6 or pSi-IL-32-7, or a scrambled DNA sequence for control cells, by use of Effectene transfection reagent (Qiagen). The transfectants were cultured with G418 (50 μg/ml) and selected. We established two independent knockdown cell lines, AGS-IL32KD1 and AGS-IL32KD2, using pSi-IL-32-6 and pSi-IL-32-7, respectively.

To obtain IL-32-overexpressing cell lines, AGS cells were transfected with pcDNA-IL-32β and selected with G418. Two cell lines were established (AGS IL-32 clone 15 and AGS IL-32 clone 19). The control cell line was generated by transfection with empty pcDNA3.1 and selection with G418.

Luciferase assay.

AGS cells cultured in 24-well tissue culture plates were transfected with 100 ng/μl −133-IL-8-Luc or pNF-κB-Luc and 10 ng/μl pRL-TK, using Effectene transfection reagent (Qiagen). In the rescue experiment, AGS-IL32KD1 cells were transfected with 100 ng of pcDNA-mIL32β or the empty pcDNA3.1 vector. After 24 h, H. pylori was added (ratio of cells to bacteria = 1:100) and cocultured for a further 24 h. Cells were washed with PBS and lysed in luciferase lysis buffer. The lysates were assayed using a Pica-Gene dual-luciferase reporter assay system (Toyo Ink, Tokyo, Japan) as described previously (31). All assays were performed at least three times independently, in triplicate.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analysis was performed using Student's t test, two-sided or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Dunnett's multiple-comparison test, or Tukey's honestly significant difference (HSD) test. Differences were considered statistically significant if the P value was <0.05.

RESULTS

IL-32 expression correlates with the severity of gastric disease.

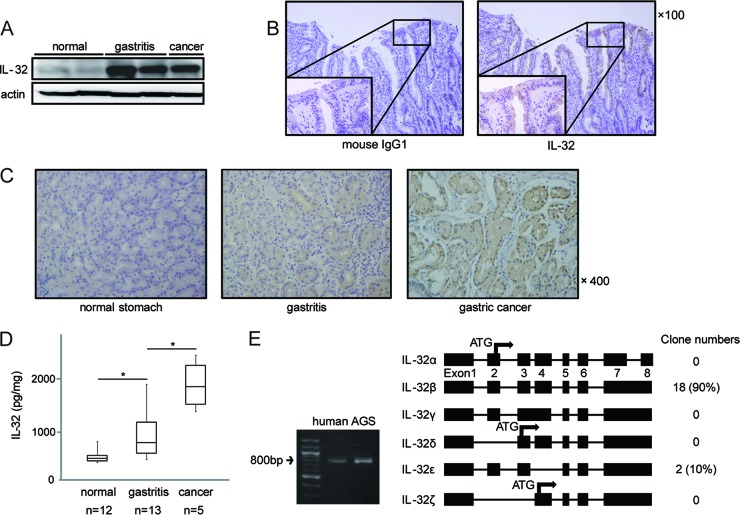

To investigate the involvement of IL-32 in H. pylori-induced gastric disease, we first examined the expression levels of IL-32 in human gastric tissues. IL-32 levels were elevated in gastritis tissues and gastric cancer tissues compared to those in H. pylori-negative healthy gastric mucosa, as determined by immunoblot analysis (Fig. 1A). Immunohistochemical analysis indicated that high levels of IL-32 were present in the cytoplasm of gastric epithelial cells from gastritis patients (Fig. 1B, right panel), while the negative isotype control with mouse IgG1 antibody exhibited negative staining (Fig. 1B, left panel). IL-32 expression was weak or not detectable in healthy gastric mucosa (Fig. 1C, left panel). IL-32 was strongly positive in the cytoplasm of gastric cancer cells (Fig. 1C, right panel).

Fig 1.

Expression of IL-32 in human gastric tissues. (A) Immunoblot analysis of IL-32 protein in healthy human gastric tissues, gastritis tissues, and gastric cancer tissues. (B) (Left) Mouse IgG1 isotype antibody as the negative control. (Right) Representative immunohistochemical analysis of IL-32 expression in human gastritis tissue. (C) Typical examples of immunohistochemical analysis of IL-32 expression in healthy human gastric tissue (left), gastritis tissue (center), and gastric cancer tissue (right). (D) Graphic representation of IL-32 expression in human gastric samples, including healthy gastric mucosa, gastritis tissues, and gastric cancer tissues. Expression was quantified by ELISA. Each box plot indicates the median (horizontal line), interquartile range (the box itself), and the sample minimum and maximum (bars). *, P < 0.05 by Tukey's HSD test. (E) (Left) The full-length coding region of IL-32 cDNA, synthesized from RNA extracted from human gastritis tissue and AGS cells infected with H. pylori, was amplified by PCR. (Right) Known structures of IL-32 isoforms (splice variants) and numbers of clones detected in human gastritis tissue. The exon numbers are shown beneath the boxes.

To quantitate IL-32 expression, IL-32 concentrations in gastric tissues were determined by ELISA. As shown in Fig. 1D, IL-32 protein levels increased depending on the pathology, ranging from very low in healthy gastric mucosa to intermediate in H. pylori-infected gastric mucosa and high in gastric cancer tissue. The IL-32 concentration in gastritis tissue (643 ± 492 pg/ml) was significantly higher than that in healthy gastric tissue (208 ± 133 pg/ml). Gastric cancer tissue exhibited an even higher IL-32 expression level (1,651 ± 488 pg/ml), which was statistically significant compared to that in gastritis tissue.

To determine the IL-32 isoforms that are expressed in gastric tissue, full-length IL-32 mRNA was amplified from the cDNA obtained from gastritis tissue. As shown in Fig. 1E (left panel), human gastritis tissue, as well as AGS cells, expressed full-length IL-32. By cloning the IL-32 mRNA from gastritis tissue, we found that 90% of IL-32 was IL-32β (18/20 samples) and 10% was IL-32ε (2/20 samples); no other isoforms were detected (Fig. 1E, right panel).

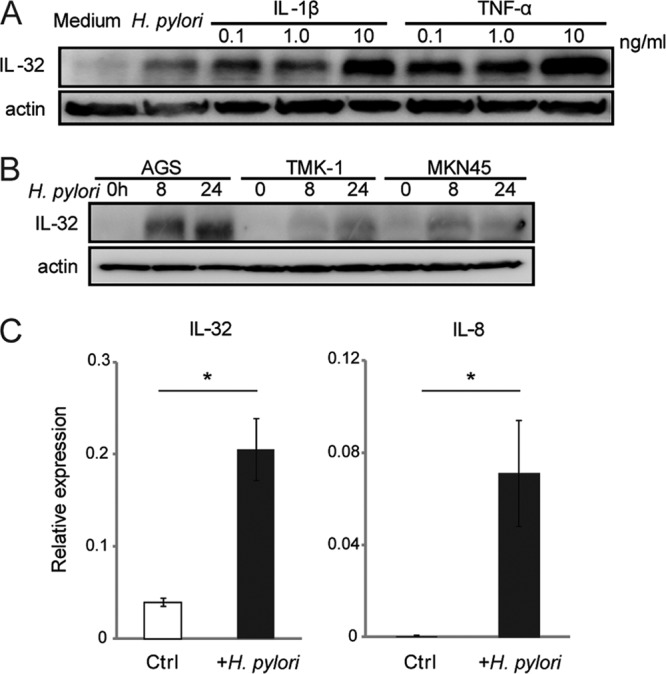

H. pylori infection induces IL-32 expression in gastric cancer cells.

Next, we investigated the expression of IL-32 in vitro by using gastric cancer cell lines. IL-1β and TNF-α have been reported to strongly induce IL-32 in several cell lines (21, 37, 54). Twenty-four hours after stimulation with IL-1β, TNF-α, and cagPAI-positive H. pylori strain TN2, IL-32 expression was induced in AGS cells (Fig. 2A). Western blot analysis revealed that IL-32 was also induced by H. pylori in the TMK-1 and MKN45 gastric cancer cell lines, in a time-dependent manner (Fig. 2B). IL-32 mRNA levels were then determined by real-time RT-PCR. IL-32 mRNA levels in AGS cells increased after infection with H. pylori for 3 h, similar to the increase in IL-8 mRNA levels (Fig. 2C). These results indicate that H. pylori enhances IL-32 mRNA and protein expression in infected gastric cells in vitro.

Fig 2.

H. pylori infection induces IL-32 expression in gastric cancer cells. (A) AGS cells were infected with cagPAI-positive H. pylori strain TN2 for 24 h or stimulated with IL-1β or TNF-α for 24 h at the indicated concentrations. IL-32 expression was detected by immunoblot analysis. (B) AGS, TMK-1, and MKN45 gastric cancer cells were cocultured with H. pylori for the indicated times (hours), and IL-32 expression was evaluated by immunoblot analysis. (C) IL-32 and IL-8 mRNA levels in AGS cells after infection with H. pylori for 6 h were determined by real-time RT-PCR. Data shown are means and standard errors of the means (SEM) (n = 3). *, P < 0.05 by Student's t test.

IL-32 is induced by the NF-κB signaling pathway in AGS cells cocultured with H. pylori.

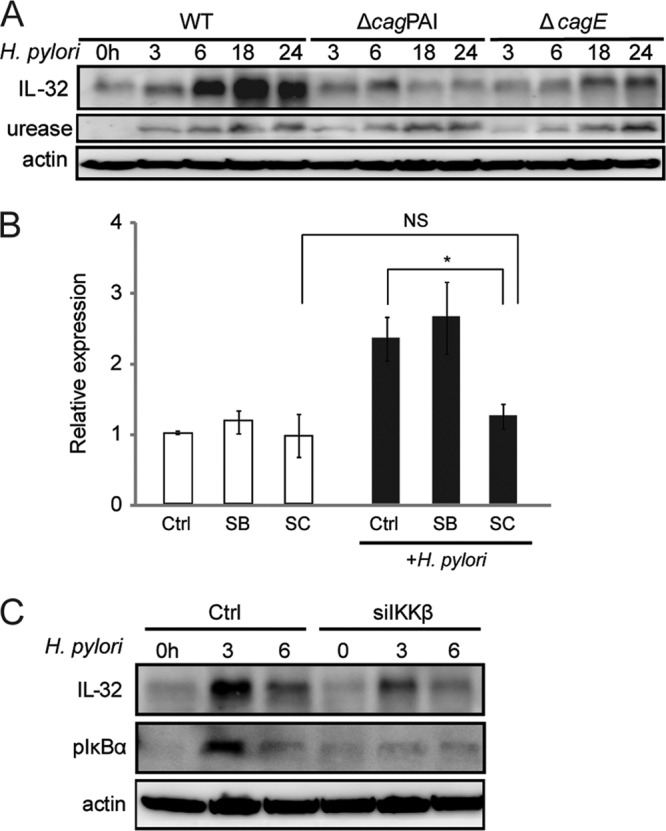

Progression of gastric disease is affected by the presence of H. pylori virulence factors such as cagPAI. We next examined the role of cagPAI in IL-32 expression by using isogenic mutant strains of TN2. Immunoblot analysis showed that IL-32 expression after infection with TN2-ΔcagPAI and TN2-ΔcagE was significantly weaker than that induced by wild-type H. pylori (Fig. 3A), suggesting that the cagPAI and cagE virulence factors upregulate IL-32 expression.

Fig 3.

H. pylori infection induces IL-32 production in AGS cells via the NF-κB signaling pathway. (A) Levels of IL-32 in AGS cells infected with wild-type H. pylori (WT), TN2-ΔcagPAI, or TN2-ΔcagE for the indicated times were determined by immunoblot analysis. Anti-urease staining was used to control for H. pylori strain variations. (B) H. pylori-induced IL-32 mRNA expression, with or without chemical inhibitors, was examined by real-time RT-PCR. The IKKβ inhibitor SC-514 (SC) and the p38 inhibitor SB203580 (SB) were added at a concentration of 20 μM 1 h before H. pylori infection. Cells were cocultured with H. pylori for 24 h. Data are means and SEM (n = 3). *, P < 0.05 by Dunnett's multiple-comparison test; NS, not significant. (C) H. pylori-induced IL-32 expression in AGS cells treated with control siRNA and IKKβ siRNA, as determined by immunoblot analysis. AGS cells were transfected with the siRNAs for 48 h and then infected with H. pylori for the indicated times.

Since cagPAI-positive H. pylori exhibits a higher capacity to activate NF-κB and MAPK, especially in epithelial cells (11, 16), we next investigated the involvement of these signaling pathways in the expression of IL-32 in H. pylori-infected cells. When we examined the effects of chemical inhibitors of IKKβ (SC-514) and p38 (SB203580) on H. pylori-induced IL-32 expression, H. pylori-induced IL-32 mRNA expression was significantly reduced in cells preincubated with SC-514 but not in those preincubated with SB203580 (Fig. 3B). To confirm the involvement of IKKβ in H. pylori-induced IL-32 expression, siRNA for IKKβ was transfected into cells. H. pylori-induced IL-32 levels were reduced by IKKβ siRNA (Fig. 3C). These results indicate that IL-32 is induced via the NF-κB signaling pathway in AGS cells infected with cagPAI-positive H. pylori.

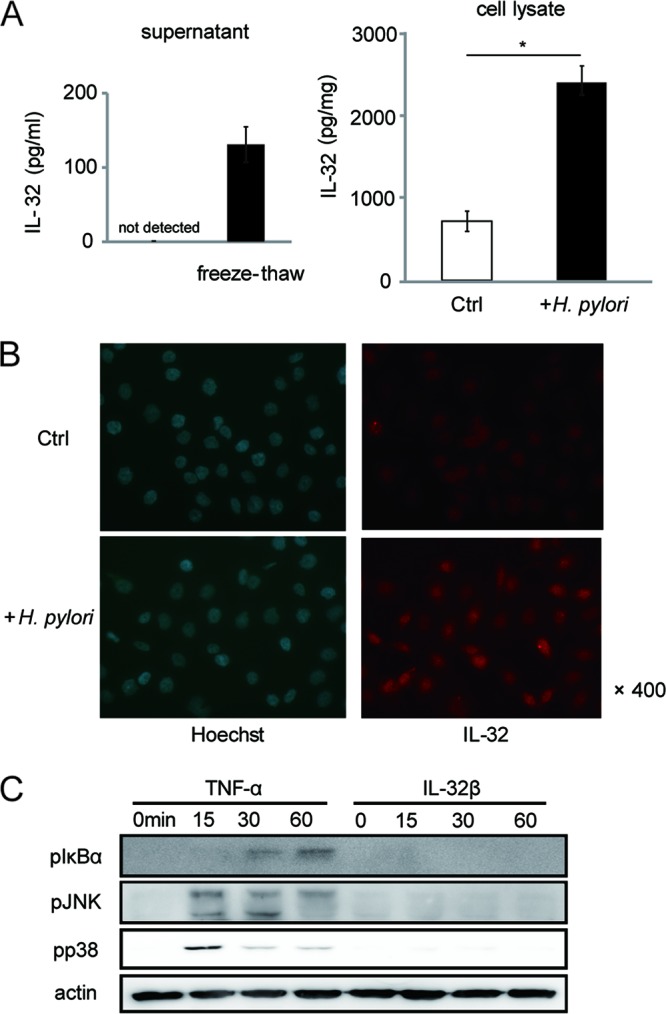

IL-32 is intracellular in H. pylori-infected cells.

Next, we investigated IL-32 expression by gastric cells. First, we examined IL-32 levels in the supernatants of H. pylori-infected AGS cells. While a 24-h infection with wild-type H. pylori typically produced 1,000 pg/ml of IL-8 protein in AGS cell supernatants (data not shown), our ELISA results showed that IL-32 concentrations were below the detection limit (<16 pg/ml) in the same supernatants in our ELISA. When we disrupted the cell membrane by freeze-thawing, IL-32 protein was detected in the supernatant of AGS cells, suggesting an intracellular accumulation of IL-32 in H. pylori-infected cells (Fig. 4A, left panel). We also examined intracellular protein levels in AGS cells, with or without H. pylori infection, by ELISA. Lysates of uninfected AGS cells contained 800 pg/mg of IL-32. However, H. pylori infection significantly increased the intracellular IL-32 level (Fig. 4A, right panel).

Fig 4.

IL-32 is intracellular in H. pylori-infected cells. (A) (Left) IL-32 concentrations in supernatants were quantitated by ELISA. Supernatants were collected from AGS cells infected with H. pylori for 24 h and from the same cells that had been freeze-thawed to facilitate cell membrane destruction. (Right) IL-32 concentrations in AGS cell lysates, with or without H. pylori infection for 24 h, were determined by ELISA. Data shown are means and SEM (n = 3). *, P < 0.05 by Student's t test. (B) AGS cells were cocultured with H. pylori for 24 h, and IL-32 expression was analyzed by immunofluorescence staining. Nuclear staining was conducted using Hoechst 33342. (C) Immunoblots of the indicated proteins in AGS cells stimulated with TNF-α (1 ng/ml) or recombinant IL-32β (1 ng/ml) for 0, 15, 30, or 60 min.

To address the localization of IL-32 in AGS cells, we performed immunofluorescence staining. As shown in Fig. 4B, uninfected AGS cells contained low levels of IL-32 in the cytosol. H. pylori infection increased both cytosolic and nuclear IL-32 levels, leading us to question whether IL-32 in gastric cells functions as a typical cytokine. Thus, we examined whether extracellular IL-32 could activate intracellular signaling in gastric epithelial cells, as it has been reported to do in macrophages (23). In contrast to the case with TNF-α, stimulation of AGS cells with recombinant IL-32β did not enhance IκBα, JNK, or p38 phosphorylation in AGS cells, suggesting that IL-32 has a specific intracellular function in gastric cells (Fig. 4C).

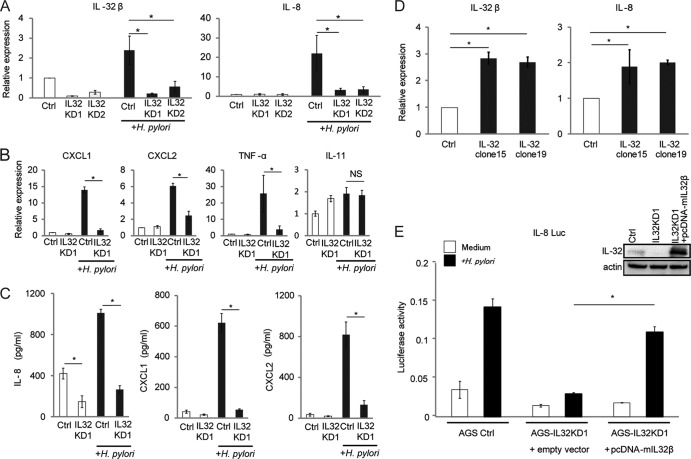

IL-32 expression upregulates IL-8, CXCL1, CXCL2, and TNF-α expression.

Previous reports showed that IL-32 functions as a proinflammatory cytokine which elicits production of other inflammatory cytokines in diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis. Due to its intracellular localization in AGS cells, we next determined whether IL-32 regulates inflammatory cytokines. We established two stable IL-32-knockdown AGS cell lines, AGS-IL32KD1 and AGS-IL32KD2, and decreased IL-32 mRNA expression was confirmed for both by real-time RT-PCR (Fig. 5A, left panel). Next, we examined whether IL-32 affects the expression of cytokines in H. pylori-infected AGS cells. As shown in Fig. 5A (right panel), the expression of IL-8 mRNA was significantly decreased in both AGS-IL32KD1 and AGS-IL32KD2 cells cocultured with H. pylori compared with the level in the control cell line. We also measured the expression of other cytokines that are induced by H. pylori (17, 28, 48). CXCL1, CXCL2, and TNF-α mRNA levels were also decreased in the IL-32-knockdown cells (Fig. 5B). IL-11 mRNA levels were not decreased in the IL-32-knockdown cells (Fig. 5B). ELISA indicated that IL-8, CXCL1, and CXCL2 levels in supernatants of AGS-IL32KD1 cells cocultured with H. pylori were decreased compared to those for the control cell line (Fig. 5C). The levels of TNF-α were below the detection limit of the ELISA (<16 pg/ml) (data not shown). To confirm the role of IL-32 in the regulation of expression of other cytokines, we established two stable AGS cell lines (AGS IL-32 clone 15 and AGS IL-32 clone 19) that overexpressed IL-32. IL-8 mRNA levels were increased in these IL-32-overexpressing cells. In the two IL-32-overexpressing cell lines, IL-8 levels were 2-fold higher than that in control cells (Fig. 5D).

Fig 5.

IL-32 expression affects induction of other cytokines involved in gastritis. (A) Control (Ctrl) and stable IL-32-knockdown AGS cell lines (IL32KD1 and IL32KD2) were cultured with or without H. pylori for 6 h. IL-32β and IL-8 mRNA levels were determined by real-time RT-PCR. Data shown are means and SEM (n = 3). *, P < 0.05 by Dunnett's multiple-comparison test. (B) CXCL1, CXCL2, TNF-α, and IL-11 mRNA levels were evaluated by real-time RT-PCR analysis of AGS control cells (Ctrl) and IL32KD1 cells cultured with or without H. pylori for 6 h. Data shown are means and SEM (n = 3). *, P < 0.05 by Student's t test; NS, not significant. (C) ELISAs of IL-8, CXCL1, and CXCL2 expression in AGS cell supernatants of control (Ctrl) and IL32KD1 cells cultured with or without H. pylori for 24 h. Data shown are means and SEM (n = 3). *, P < 0.05 by Student's t test. (D) Two stable IL-32-overexpressing AGS cell lines (AGS IL-32 clone 15 and AGS IL-32 clone 19) were established. (Left) The increased IL-32 mRNA level was confirmed by real-time RT-PCR. (Right) IL-8 mRNA levels in the control (Ctrl), IL-32 clone 15, and IL-32 clone 19 cells were determined by real-time RT-PCR. Data shown are means and SEM (n = 3). *, P < 0.05 by Dunnett's multiple-comparison test. (E) IL-8 reporter activity was examined in AGS control (Ctrl), IL32KD1, and IL32KD1 cells transfected with IL-32β cDNA (pcDNA-mIL32β). Cells were left uninfected or infected with H. pylori for 24 h. Data shown are means and SEM (n = 3). *, P < 0.05 by Student's t test. The IL-32 level in each cell line is shown in the upper right panel.

Next, we asked whether the reduced IL-8 levels in IL-32-knockdown AGS cells could be rescued by overexpressing IL-32 cDNA. We reintroduced a mutant IL-32 cDNA (pcDNA-mIL32β), which was genetically modified to be resistant to the inhibitory effects of the siRNA, into AGS-IL32KD1 cells and examined IL-8 activity by using reporter assays. Immunoblot analysis confirmed that IL-32 was suppressed in AGS-IL32KD1 cells and could be rescued by overexpression of mIL-32 cDNA (Fig. 5E, upper right panel). The suppression of H. pylori-induced IL-8 reporter activation in AGS-IL32KD1 cells was rescued by overexpression of mIL-32 in AGS-IL32KD1 cells (Fig. 5E). These results suggest that IL-32 functions as an intracellular regulator of cytokine expression in H. pylori-infected gastric cells.

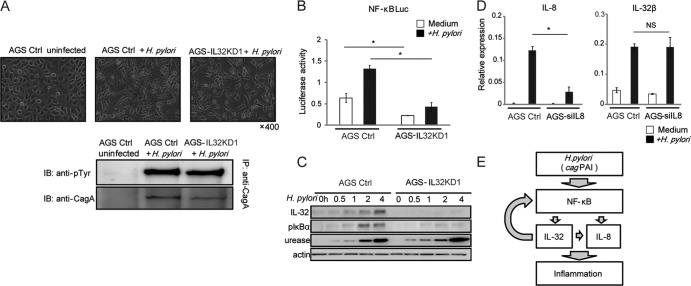

IL-32 regulates NF-κB activation in H. pylori-infected AGS cells.

We examined whether IL-32 suppression impairs the type IV secretion system of H. pylori, which is essential for induction of cytokine production in epithelial cells. CagA phosphorylation and the subsequent hummingbird phenotype of infected AGS cells are the hallmarks of the type IV secretion system (43). Microscopic analyses indicated that both AGS-IL32KD1 and AGS control cells cocultured with H. pylori developed the hummingbird phenotype (Fig. 6A, upper panels). CagA was phosphorylated in AGS-IL32KD1 and AGS control cells (Fig. 6A, lower panel), indicating that IL-32 expression does not affect type IV secretion.

Fig 6.

Role of IL-32 in H. pylori-induced cell signaling. (A) (Top) Micrographs of uninfected AGS cells transfected with the nonsilencing control (AGS Ctrl), AGS Ctrl cells infected with H. pylori, and stable IL-32-knockdown AGS (AGS-IL32KD1) cells infected with H. pylori for 24 h. (Bottom) Cell lysates of uninfected AGS Ctrl cells, AGS Ctrl cells infected with H. pylori, and AGS-IL32KD1 cells infected with H. pylori for 24 h were immunoprecipitated (IP) using anti-CagA antibody, and the immunoprecipitates were immunoblotted (IB) using anti-phosphotyrosine and anti-CagA antibodies. (B) NF-κB activation induced by 24-h H. pylori infection of AGS Ctrl cells and AGS-IL32KD1 cells was determined using luciferase activity assays. Data shown are means and SEM (n = 3). *, P < 0.05 by Student's t test. (C) Immunoblot analysis of IL-32 and pIκBα levels in AGS Ctrl cells and AGS-IL32KD1 cells infected with H. pylori for the indicated times. Anti-urease staining was used to control the H. pylori load. (D) H. pylori-induced IL-32β mRNA (right) and IL-8 mRNA (left) levels in AGS cells treated with control siRNA (AGS Ctrl) and IL-8 siRNA (AGS-siIL8), as determined by real-time RT-PCR. AGS cells were transfected with the siRNAs for 48 h and then infected with H. pylori for an additional 24 h. Data shown are means and SEM (n = 3). *, P < 0.05 by Student's t test; NS, not significant. (E) Summary of the role of IL-32 in gastritis. H. pylori induces NF-κB activation in gastric epithelial cells in a cagPAI-dependent manner. NF-κB activation is required for IL-32 expression. Intracellular IL-32 expression amplifies both NF-κB activation and IL-8 expression.

Next, we examined NF-κB activation in AGS IL-32 stable-knockdown cells. A luciferase reporter assay indicated that NF-κB activation induced by H. pylori was decreased in AGS-IL32KD cells compared with the level in the control cell line (Fig. 6B). Immunoblot analysis showed that phosphorylation of IκBα was decreased in AGS-IL32KD1 cells cocultured with H. pylori compared with the level in the control cell line. This indicates that NF-κB signaling is defective in AGS-IL32KD1 cells (Fig. 6C).

Finally, we tested the contribution of downregulation of IL-8 mRNA to the level of IL-32 mRNA. The siRNA for IL-8 was transfected into the AGS cell lines, and decreased IL-8 mRNA expression was confirmed by real-time RT-PCR (Fig. 6D, left panel). H. pylori-induced IL-32 levels were not significantly different in AGS cells transfected with scrambled siRNA and AGS cells transfected with siRNA for IL-8 (Fig. 6D, right panel).

These results indicate that intracellular IL-32 expression is associated with NF-κB activation and subsequent cytokine production in gastric epithelial cells infected with H. pylori.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we showed that expression of IL-32 is elevated in human gastritis and gastric cancer tissues. We also demonstrated that IL-32 is induced by H. pylori in vitro. In addition, our results indicate that IL-32 expression activates NF-κB and induces cytokine production, including that of IL-8. These results suggest that IL-32 is fundamental to the gastric inflammation caused by H. pylori. H. pylori induces NF-κB activation in gastric epithelial cells in a cagPAI-dependent manner which is required for IL-32 upregulation. In turn, intracellular IL-32 amplifies NF-κB activity and cytokine production, which accelerate the inflammatory responses of gastric tissue infected with H. pylori (Fig. 6D).

IL-32 has six described mRNA splice variants, named IL-32α, -β, -γ, -δ, -ε, and -ζ (12, 23). In our analysis, IL-32β was the major isoform detected in gastritis tissue. IL-32β is reportedly a major isoform in endothelial cells, and it has a critical function in vascular inflammation and sepsis (25). The longest IL-32 isoform, IL-32γ, is the most abundant in rheumatoid arthritis synovial tissue (14). IL-32γ exerts the greatest induction of TNF-α in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (4). However, IL-32γ mRNA was not detected in gastritis tissue. A possible explanation for the differing IL-32 isoform abundances among disease tissues may be that the splicing of IL-32 differs in different cell types or due to various inductive stimuli. The biological differences and mechanisms of tissue-specific expression of the IL-32 isoforms need to be investigated to understand the roles of this cytokine in humans.

We also investigated the mechanisms of IL-32 induction by H. pylori in AGS cells. Previous reports on IL-32 expression suggested the involvement of the JNK (33), p38 (24), extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) (37), and NF-κB (37) pathways. We found that cagPAI-positive H. pylori induced production of IL-32, in agreement with the activation of NF-κB by cagPAI-positive H. pylori in the pathogenesis of gastric diseases (2, 11). As expected, inhibition of the NF-κB pathway resulted in decreased IL-32 induction in the H. pylori-infected gastric epithelial cell model. These results indicate that IL-32 is induced in gastric epithelial cells through the activation of NF-κB by H. pylori infection.

To determine its role in gastritis, we examined the pattern of IL-32 expression in AGS cells and found it to be retained intracellularly. This is in contrast to the case for most cytokines, which are generally secreted from cells. In our investigation, recombinant IL-32β, unlike TNF-α, failed to activate IκBα, JNK, and p38 in AGS cells (Fig. 4C), which differs from the situation in macrophages (23). Furthermore, IL-32 was not detected by ELISA in supernatants of AGS cells cocultured with H. pylori. Thus, autocrine signaling activation by IL-32 in gastric cells seems unlikely. Instead, disruption of the cell membrane increased the IL-32 concentration in the supernatant to detectable levels (Fig. 4A). These results are consistent with previous reports that described intracellular IL-32 expression and leakage from apoptotic cells (12, 13, 26). Note that neutrophil proteinase 3, an IL-32 binding protein that is expressed in neutrophils and monocytes, is highly expressed in H. pylori-related gastritis (18). IL-32 from damaged epithelial cells may activate myeloid cells through an IL-32–neutrophil proteinase 3 interaction to enhance inflammation of gastric tissue. Although intracellular receptors for IL-32 have not been discovered, some interleukins, such as IL-1 and IL-33, are known to have intracellular targets and to play roles as both intracellular and secreted mediators (27). Thus, IL-32 may act intracellularly in gastric epithelial cells and extracellularly on myeloid cells.

We found that IL-32 expression levels increased concurrent with disease progression in the gastric mucosa. IL-32 staining was increased in inflamed lesions of chronic pancreatitis and strongly positive in pancreatic cancer cells, suggesting the involvement of this cytokine in pancreatic carcinogenesis (36). However, the mechanism by which IL-32 expression modifies the inflammatory processes ultimately leading to malignancy is largely unknown. Our results showing that H. pylori-induced NF-κB activation enhances IL-32 expression and that IL-32 in turn amplifies the NF-κB signaling pathway may suggest a contribution to inflammation-induced carcinogenesis. Interestingly, when IL-32 was knocked down, expression of the antiapoptotic genes for Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL in pancreatic cell lines was reduced (36); these are regulated by the NF-κB pathway (20). Thus, it is plausible that IL-32 expression also amplifies NF-κB signaling in pancreatic cancer cells. Taken together, our findings suggest that IL-32 is involved in the inflammation-cancer process through amplification of NF-κB expression and upregulation of its targets, including IL-32 itself.

In conclusion, the inflammatory molecule IL-32 plays an important role in gastritis. H. pylori infection induces IL-32 through NF-κB activation in a cag-dependent manner. IL-32 amplifies the NF-κB pathway and induces production of other inflammatory cytokines, including IL-8. IL-32 may be a future target for medical treatment of gastric inflammation and carcinogenesis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Mitsuko Tsubouchi for technical assistance. We thank Takaaki Sano and Teiji Motojima (Motojima General Hospital, Gumma, Japan) for provision of gastric carcinoma specimens.

This work was partly supported by a grant-in-aid for scientific research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan to Y. Hirata.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 13 August 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Aihara M, et al. 1997. Mechanisms involved in Helicobacter pylori-induced interleukin-8 production by a gastric cancer cell line, MKN45. Infect. Immun. 65:3218–3224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Backert S, Naumann M. 2010. What a disorder: proinflammatory signaling pathways induced by Helicobacter pylori. Trends Microbiol. 18:479–486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bai XY, et al. 2010. IL-32 is a host protective cytokine against Mycobacterium tuberculosis in differentiated THP-1 human macrophages. J. Immunol. 184:3830–3840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Choi JD, et al. 2009. Identification of the most active interleukin-32 isoform. Immunology 126:535–542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Correa P. 1992. Human gastric carcinogenesis—a multistep and multifactorial process. 1st American Cancer Society award lecture on cancer epidemiology and prevention. Cancer Res. 52:6735–6740 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Crabtree JE, et al. 1995. Helicobacter pylori induced interleukin-8 expression in gastric epithelial cells is associated with cagA positive phenotype. J. Clin. Pathol. 48:41–45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dahl CA, Schall RP, He HL, Cairns JS. 1992. Identification of a novel gene expressed in activated natural killer cells and T cells. J. Immunol. 148:597–603 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. de Vries AC, et al. 2008. Gastric cancer risk in patients with premalignant gastric lesions: a nationwide cohort study in the Netherlands. Gastroenterology 134:945–952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. El-Omar EM, et al. 2000. Interleukin-1 polymorphisms associated with increased risk of gastric cancer. Nature 404:398–402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fukase K, et al. 2008. Effect of eradication of Helicobacter pylori on incidence of metachronous gastric carcinoma after endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer: an open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 372:392–397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Glocker E, et al. 1998. Proteins encoded by the cag pathogenicity island of Helicobacter pylori are required for NF-kappa B activation. Infect. Immun. 66:2346–2348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Goda C, et al. 2006. Involvement of IL-32 in activation-induced cell death in T cells. Int. Immunol. 18:233–240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hasegawa H, Thomas HJ, Schooley K, Born TL. 2011. Native IL-32 is released from intestinal epithelial cells via a non-classical secretory pathway as a membrane-associated protein. Cytokine 53:74–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Heinhuis B, et al. 2011. Inflammation-dependent secretion and splicing of IL-32 gamma in rheumatoid arthritis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108:4962–4967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hirata Y, et al. 2001. Helicobacter pylori activates the cyclin D1 gene through mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway in gastric cancer cells. Infect. Immun. 69:3965–3971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hirata Y, et al. 2002. Helicobacter pylori CagA protein activates serum response element-driven transcription independently of tyrosine phosphorylation. Gastroenterology 123:1962–1971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hirata Y, et al. 2006. Helicobacter pylori induces I kappa B kinase at nuclear translocation and chemokine production in gastric epithelial cells. Infect. Immun. 74:1452–1461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hong SN, et al. 2012. Clinical characteristics and the expression profiles of inflammatory cytokines/cytokine regulatory factors in asymptomatic patients with nodular gastritis. Dig. Dis. Sci. 6:1486–1495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Karin M, Lawrence T, Nizet V. 2006. Innate immunity gone awry: linking microbial infections to chronic inflammation and cancer. Cell 124:823–835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Karin M, Lin A. 2002. NF-kappa B at the crossroads of life and death. Nat. Immunol. 3:221–227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kato A, et al. 2010. IL-32 expression in chronic rhinosinusitis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 125:AB61 [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kim KH, et al. 2008. Interleukin-32 monoclonal antibodies for immunohistochemistry, Western blotting, and ELISA. J. Immunol. Methods 333:38–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kim SH, Han SY, Azam T, Yoon DY, Dinarello CA. 2005. Interleukin-32: a cytokine and inducer of TNF alpha. Immunity 22:131–142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ko NY, et al. 2011. Interleukin-32 alpha production is regulated by MyD88-dependent and independent pathways in IL-1 beta-stimulated human alveolar epithelial cells. Immunobiology 216:32–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kobayashi H, et al. 2010. Interleukin-32 beta propagates vascular inflammation and exacerbates sepsis in a mouse model. PLoS One 5:e9458 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0009458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kobayashi H, Lin PC. 2009. Molecular characterization of IL-32 in human endothelial cells. Cytokine 46:351–358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Luheshi NM, Rothwell NJ, Brough D. 2009. Dual functionality of interleukin-1 family cytokines: implications for anti-interleukin-1 therapy. Br. J. Pharmacol. 157:1318–1329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Maeda S, et al. 2001. Distinct mechanism of Helicobacter pylori-mediated NF-kappa B activation between gastric cancer cells and monocytic cells. J. Biol. Chem. 276:44856–44864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Maeda S, Mentis AF. 2007. Pathogenesis of Helicobacter pylori infection. Helicobacter 12:10–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Maeda S, et al. 2000. H. pylori activates NF-kappa B through a signaling pathway involving I kappa B kinases, NF-kappa B-inducing kinase, TRAF2, and TRAF6 in gastric cancer cells. Gastroenterology 119:97–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mitsuno Y, et al. 2001. Helicobacter pylori induced transactivation of SRE and AP-1 through the ERK signalling pathway in gastric cancer cells. Gut 49:18–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Moschen AR, et al. 2011. Interleukin-32: a new proinflammatory cytokine involved in hepatitis C virus-related liver inflammation and fibrosis. Hepatology 53:1819–1829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mun SH, et al. 2009. Tumor necrosis factor alpha-induced interleukin-32 is positively regulated via the Syk/protein kinase C delta/JNK pathway in rheumatoid synovial fibroblasts. Arthritis Rheum. 60:678–685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Nahar IK, Shojania K, Marra CA, Alamgir AH, Anis AH. 2003. Infliximab treatment of rheumatoid arthritis and Crohn's disease. Ann. Pharmacother. 37:1256–1265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Netea MG, et al. 2006. Mycobacterium tuberculosis induces interleukin-32 production through a caspase1/IL-18/interferon-gamma-dependent mechanism. PLoS Med. 3:1310–1319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Nishida A, Andoh A, Inatomi O, Fujiyama Y. 2009. Interleukin-32 expression in the pancreas. J. Biol. Chem. 284:17868–17876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Nold-Petry CA, et al. 2009. IL-32-dependent effects of IL-1 beta on endothelial cell functions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:3883–3888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ogura K, et al. 2008. The effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication on reducing the incidence of gastric cancer. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 42:279–283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ogura K, et al. 1998. Interleukin-8 production in primary cultures of human gastric epithelial cells induced by Helicobacter pylori. Dig. Dis. Sci. 43:2738–2743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ohmae T, et al. 2005. Helicobacter pylori activates NF-kappa B via the alternative pathway in B lymphocytes. J. Immunol. 175:7162–7169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Pan XF, et al. 2011. Interleukin-32 expression induced by hepatitis B virus protein X is mediated through activation of NF-kappa B. Mol. Immunol. 48:1573–1577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sakitani K, et al. 2011. Gastric cancer risk according to the distribution of intestinal metaplasia and neutrophil infiltration. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 26:1570–1575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Segal ED, Cha J, Lo J, Falkow S, Tompkins LS. 1999. Altered states: involvement of phosphorylated CagA in the induction of host cellular growth changes by Helicobacter pylori. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96:14559–14564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Shioya M, et al. 2007. Epithelial overexpression of interleukin-32 alpha in inflammatory bowel disease. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 149:480–486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Shoda H, et al. 2006. Interactions between IL-32 and tumor necrosis factor alpha contribute to the exacerbation of immune-inflammatory diseases. Arthritis Res. Ther. 8:R166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Sorrentino C, Di Carlo E. 2009. Expression of IL-32 in human lung cancer is related to the histotype and metastatic phenotype. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 180:769–779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Sugimoto M, et al. 2007. Different effects of polymorphisms of tumor necrosis factor-alpha and interleukin-1 beta on development of peptic ulcer and gastric cancer. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 22:51–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Sugimoto M, Ohno T, Graham DY, Yamaoka Y. 2011. Helicobacter pylori outer membrane proteins on gastric mucosal interleukin 6 and 11 expression in Mongolian gerbils. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 26:1677–1684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Suzuki M, et al. 1997. Enhancement of neutrophil infiltration in the corpus after failure of Helicobacter pylori eradication. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 25:S222–S228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Taguchi A, et al. 2005. Interleukin-8 promoter polymorphism increases the risk of atrophic gastritis and gastric cancer in Japan. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 14:2487–2493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Uemura N, et al. 2001. Helicobacter pylori infection and the development of gastric cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 345:784–789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Warren JR, Marshall BJ. 1983. Unidentified curved bacilli on gastric epithelium in active chronic gastritis. Lancet i:1273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Wong BCY, et al. 2004. Helicobacter pylori eradication to prevent gastric cancer in a high-risk region of China—a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 291:187–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Yagi Y, et al. 2011. Interleukin-32 alpha expression in human colonic subepithelial myofibroblasts. Int. J. Mol. Med. 27:263–268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]