Abstract

The Yfe/Sit and Feo transport systems are important for the growth of a variety of bacteria. In Yersinia pestis, single mutations in either yfe or feo result in reduced growth under static (limited aeration), iron-chelated conditions, while a yfe feo double mutant has a more severe growth defect. These growth defects were not observed when bacteria were grown under aerobic conditions or in strains capable of producing the siderophore yersiniabactin (Ybt) and the putative ferrous transporter FetMP. Both fetP and a downstream locus (flp for fet linked phenotype) were required for growth of a yfe feo ybt mutant under static, iron-limiting conditions. An feoB mutation alone had no effect on the virulence of Y. pestis in either bubonic or pneumonic plague models. An feo yfe double mutant was still fully virulent in a pneumonic plague model but had an ∼90-fold increase in the 50% lethal dose (LD50) relative to the Yfe+ Feo+ parent strain in a bubonic plague model. Thus, Yfe and Feo, in addition to Ybt, play an important role in the progression of bubonic plague. Finally, we examined the factors affecting the expression of the feo operon in Y. pestis. Under static growth conditions, the Y. pestis feo::lacZ fusion was repressed by iron in a Fur-dependent manner but not in cells grown aerobically. Mutations in feoC, fnr, arcA, oxyR, or rstAB had no significant effect on transcription of the Y. pestis feo promoter. Thus, the factor(s) that prevents repression by Fur under aerobic growth conditions remains to be identified.

INTRODUCTION

Nearly all bacterial pathogens must acquire iron from the host to proliferate and cause disease. Consequently, many bacteria have a wide variety of transport systems for the acquisition of iron and/or heme (21). In some cases, it appears that different uptake systems are required in different host organs or during some, but not all, stages of the disease process. For example, in Bordetella pertussis, expression of the siderophore-based systems, alcaligin and enterobactin, occurs early in lung infections, while the heme transport system is expressed late (10, 11). Yersinia pestis, the causative agent of bubonic and pneumonic plague, has numerous putative and proven systems for the uptake of iron or heme. These include the yersiniabactin (Ybt) system, which is responsible for the synthesis and transport of the Ybt siderophore; a number of ABC transporters, such as Yfe, Yiu, Fhu, and Yfu; two heme transporters (Hmu and Has); and ferrous iron transporters (Yfe, Feo, Fet, and Efe) (33, 65).

In Y. pestis, the Ybt system is encoded within a 102-kb region of the chromosome referred to as the pgm locus. The pgm locus is flanked by two IS100 elements, and recombination between these two elements results in the deletion of the intervening DNA. In addition to the Ybt system, several other genes are contained within the pgm locus, including ones involved in biofilm development and a putative Fe2+ transporter (FetMP). The Ybt system is required in order to cause disease by peripheral routes of infection but not by an intravenous route (3, 27, 36, 85). Thus, a strain missing the entire pgm locus is still fully virulent when administered directly into the bloodstream. However, a ΔyfeAB Δpgm double mutant is completely avirulent by an intravenous route of infection (4). These results suggest that for bubonic plague, the Ybt system is critical in the early stages of disease, while the Yfe ABC transporter is important later in the infectious process (4, 5).

The Ybt system is encoded on a pathogenicity island within the pgm locus and includes gene products for the synthesis and transport of the Ybt siderophore as well as a transcriptional activator of these genes. Under aerobic conditions in vitro where ferric iron would predominate, the Ybt system is the primary iron transport system used by Y. pestis. Consequently, iron-chelated growth defects due to mutations in the Yfe, Yfu, or Yiu system are observed in a Δpgm or Ybt− background but not in a Ybt+ background (4, 36, 49, 53, 62, 65).

The Yfe system is an ABC transporter for iron and manganese with a typical periplasmic binding protein (YfeA), two inner membrane (IM) permeases (YfeC and YfeD), and an ATPase (YfeB). An additional IM protein, YfeE, seems to assist in iron transport via Yfe but is not essential. An outer membrane (OM) component for the Yfe system has not been identified, and the transport of iron via Yfe is TonB independent. The yfeABCD promoter is repressed by both iron and manganese through the action of Fur. In contrast, the yfeE promoter is not repressed by either cation (4, 5, 61, 67).

The Feo transporter is widespread among bacteria and has a demonstrated role in the uptake of ferrous iron under anoxic and/or intracellular growth conditions. The Y. pestis FeoA (FeoAYp) and FeoB predicted gene products are highly homologous to those of Escherichia coli and Shigella flexneri. In E. coli, FeoA is a small (8.3-kDa) protein of unproven function; it has been suggested that FeoA interacts with FeoB to stimulate GTPase activity and ferrous iron uptake. FeoAYp is 73% identical and 87% similar to FeoAEc. While FeoBYp (83.9 kDa) is clearly an ortholog of the putative FeoBEc permease (78% identical and 95% similar over 712 of 771 residues), it lacks the 60 C-terminal amino acids of FeoBEc. The 9.1-kDa FeoCYp protein shows the most divergence, being 53% identical and 77% similar to FeoCEc. Based on bioinformatic analysis and indirect experimental evidence, it has been speculated that FeoC may be a transcriptional repressor of the feoABC locus (7, 12, 20, 23, 38, 57, 66, 73, 80).

Previously, we showed that the Y. pestis Feo and Yfe systems share partially redundant functions for iron uptake during microaerobic growth. Single feoA, feoB, or yfeAB mutations in a Δpgm background caused reduced growth on nitrilotriacetic acid gradient plates in a candle jar, while a yfeAB feoB double mutant had a more severe growth defect. In contrast, an feoC mutation had no significant effect on microaerobic, iron-chelated growth regardless of whether the Yfe system was present (66).

It has been known for some time that Y. pestis can replicate within macrophage lines, and there is clear evidence that Y. pestis cells are found inside macrophages early in infection (15, 37, 54, 69, 79). We have shown that in strains missing the pgm locus, the Yfe and Feo systems play a role in intracellular growth in J774A.1 cells (66).

However, the role, if any, of the Feo system in the virulence of Y. pestis is unknown. Here we show that an feoB mutant was fully virulent in mouse models of bubonic and pneumonic plague. A yfe feoB double mutant was also fully virulent by an intranasal route of infection, but it exhibited ∼90-fold and ∼10-fold losses in virulence by a subcutaneous route of infection relative to the Yfe+ Feo+ parent strain and a yfe mutant, respectively. Thus, the Yfe and Feo systems play a role in iron acquisition during bubonic plague but are not essential for pneumonic plague.

The factors influencing the expression of the Feo system in Y. pestis had not been investigated. Here we used lacZ fusions to analyze transcription of the Y. pestis feo operon. Under static conditions, expression of feo was repressed by iron in a Fur-dependent manner. However, under aerobic conditions, the addition of iron did not repress the transcription of feo. The expression of Y. pestis feo was not affected by mutations in feoC, fnr, arcA, rstAB, or oxyR.

In addition, we have shown that FetP and one or more downstream genes (y2367-y2362; designated flpDABCTE for fet linked phenotype) are involved in the in vitro, iron-deficient, static growth of Y. pestis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and primers.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material. E. coli strains DH5α and DH5α(λpir) were used in construction of recombinant plasmids. KIM6+ and KIM6 (75) strains have been cured of the virulence plasmid pCD1, encoding the low-calcium response (Lcr) type III secretion system and its effector proteins. Strains whose names bear a plus sign possess an intact 102-kb chromosomal pgm locus which contains several genes, including those for the Ybt siderophore-dependent iron transport system and the FetMP putative ferrous uptake system as well as those involved in biofilm formation (hms). All other Y. pestis strains have either a pgm deletion (and lack the Ybt and Fet iron transport systems) or a mutation within the pgm locus. KIM5 strains contain pCD1Ap and are potentially fully virulent if the pgm locus is present [e.g., KIM5(pCD1Ap)+]. Primers used for cloning, mutant construction, and confirmation are listed in Table S2 in the supplemental material.

To clone the Y. pestis feo operon, Y. pestis genomic DNA was digested with BamHI and separated on a 1% low-melting-point agarose gel. DNA was extracted from the region of the gel expected to contain the feo operon and ligated to BamHI-digested pWSK29 (88) which had been treated with alkaline phosphatase. Positive clones were identified by colony blots using a digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled probe prepared by PCR amplification of a 420-bp fragment of Y. pestis genomic DNA using primers FeoB-F and FeoB-R2. Restriction enzyme digests confirmed the presence of the expected ∼8.9-kb BamHI insert in one of the clones (pWSKfeo) that hybridized to the feoB probe.

To clone Y. pestis fetP driven by an arabinose-inducible promoter, PCR amplification of Y. pestis genomic DNA using primers pBADfetP1 and pBADfetP2 was performed. The resulting 546-bp product was digested with EcoRI and HindIII and cloned into the same sites in pBAD24 (39). Sequencing confirmed the appropriate insert in the resulting plasmid, pBADFetP. To integrate the fetP locus back into the chromosome of fetP mutants, a 1,997-bp BglII-XbaI fragment from pWSKFetMP-AS (see below) was ligated into the BamHI and XbaI sites of suicide vector pKNG101 (47). The insert in pKNGFetP starts within the coding region of fetM, including all of fetP and 389 bp downstream of fetP. pKNGfetP was integrated into the chromosome of KIM6-2088.9, generating KIM6-2088.16; PCR using primers Y2370forC and 2368C-1 confirmed that a wild-type (WT) fetMP locus had been restored.

To clone Y. pestis fetMP, Y. pestis genomic DNA was digested with Asp718 and ScaI. DNA fragments in the 4- to 6-kb range were isolated and ligated into the Asp718 and EcoRV sites of pWSK29. The appropriate 4,893-bp insert was identified by Southern blot analysis using a DIG PCR probe generated using primers 2368C-1 and 2368C-2. The resulting plasmid, pWSKFetMP-AS, contains the fetMP locus starting 1,853 bp upstream of the putative ATG start for fetM to 389 bp downstream of the stop codon for fetP.

To clone the 6 genes (y2367-y2362 [flpDABCTE]) downstream of fetMP behind an isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG)-inducible promoter, PCR was performed using primers 2367Pro-2 and 2367Pro-3 and Y. pestis genomic DNA. The resulting ∼5,386-bp PCR product was digested with BamHI and NcoI and cloned into the same sites in pProEX-1. The resulting recombinant plasmid was designated pProEX-2367.11-1.

The feo promoter region was amplified by PCR using primers feo-Pro1 and feo-Pro2. The PCR product was digested with PmeI and AscI and cloned into the same sites in pNEB193. A clone containing the correct 412-bp insert (pNEBfeoP), confirmed by DNA sequencing (ACGT, Inc.), was digested with SphI and SmaI, and the resulting fragment containing the feo promoter was cloned into the SphI and PmeI sites in pBSlacZMCS (64), resulting in pBSfeoPlacZ. This plasmid was digested with EagI and filled in with the Klenow fragment of DNA polymerase, and the ∼4.6-kb fragment containing lacZ under the control of the feo promoter was cloned into the EcoRV site of pWSK129 (88) to yield pWSKfeoA::lacZ.

An feoB::lacZ transcriptional reporter plasmid was generated using Mu dI1734 (14). Briefly, pWSKfeo was transformed into E. coli strain PO1683 and Mu dI1734 transposition was induced by incubation at 44°C. The resulting phage lysate was used to infect M8820 (13). Plasmids were isolated from cells forming blue colonies on LB plates containing ampicillin (Ap), kanamycin (Km) and 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (X-Gal) and characterized by restriction enzyme digests to identify those carrying insertions in the correct orientation within the feo operon. One isolate, pWSKfeoMu-2, with an insertion in feoB was selected for further analysis.

To construct an feoA::lacZ reporter for integration into the Y. pestis chromosome, an SpeI and XhoI digest of pBSfeoPlacZ was filled in using the Klenow fragment of DNA polymerase and electrophoresed on a 1% agarose gel, and the 6.7-kb fragment was isolated and religated to create pBSfeoPlacZΔR1. This plasmid was digested with NaeI and NotI and filled in with the Klenow fragment of DNA polymerase, and the 6.4-kb fragment isolated from an agarose gel was religated to generate pBSfeoPlacZΔRs. A 3.8-kb EagI fragment was isolated from pBSfeoPlacZΔRs and cloned into the EagI site of the suicide vector pSucinv to create pSinvfeo. The construct was electroporated into KIM6+, and recombinants were selected for growth on tryptose blood agar base (TBA) plates containing 50 μg of ampicillin/ml. An isolate with pSinvfeo integrated into the invA locus, which is a pseudogene in Y. pestis (23), was identified by PCR using primers invD1 and feo-Pro2-1, grown overnight at 37°C in the absence of antibiotics, and plated onto TBA plates with 5% sucrose. An ampicillin-sensitive strain in which inv had been replaced by the reporter gene was identified by PCR and designated KIM6-2191+.

Construction of yfeABCD, feo, fet, irp2, arcA, fnr, oxyR, rstAB, and flpD mutations.

To generate an in-frame deletion within feoB, an ∼2.8-kb BamHI/ClaI fragment was cloned from pWSKfeo into pBluescript II KS+, creating pFeo3. A 1.48-kb BsrBI/ClaI fragment from pWSKfeo was ligated into pFeo3 digested with SfoI and ClaI, resulting in pFeo5. Ligation of an ∼2.9-kb SpoI/SalI fragment from pFeo5 into the SmaI/SalI sites of the suicide vector pKNG101 resulted in pKNGΔfeo with a 1.185-kb in-frame deletion within feoB. The ΔfeoB2088 mutation was introduced into KIM6+ and KIM6-2031.1+ by allelic exchange as previously described (27), and the resulting strains were designated KIM6-2088+ and KIM6-2088.1+, respectively.

A mutation in feoC was constructed using the red recombinase system (22). The primer pair FeoC-5′ and FeoC-3′ was used to insert either a chloramphenicol resistance (Cmr) cassette amplified from pKD3 or a kanamycin resistance (Kmr) gene amplified from pKD4 into feoC in KIM6+ (generating Cmr KIM6-2121+) or KIM6-2191+ (generating Kmr KIM6-2191.1+), respectively. Primer FeoC-2 in combination with either FeoC-in or FeoC-down was used to confirm the mutation in each strain.

Primers y2370revR and y2370forF were used in concert with pKD3 to delete fetM (y2370 in KIM10+) and insert a Cmr cassette in KIM6-2088.1+, generating KIM6-2088.3. The Cmr cassette was removed, generating KIM6-2088.4, using the FLP recombinase encoded on pCP20, followed by incubation at an elevated temperature to cure pCP20 (18). The mutation in fetM was confirmed by PCR using primers y2370revC and y2370forC. A mutation in fetP (y2368 in KIM10+) was constructed using primers Y2368F1 and Y2368R2 to amplify the Cmr cassette from pKD3. The PCR product was electroporated into KIM6-2088.5 carrying the red recombinase-bearing plasmid pWL204. Colonies in which the WT gene had been replaced with the PCR product (ΔfetP::cam) were identified using primers 2368C-1 and 2368C-2, and one mutant was designated KIM6-2088.9. To eliminate pWL204, the KIM6-2088.9 cells were grown at 37°C overnight and then streaked onto TBA plates containing 5% sucrose (TBAS) (52). Individual colonies were screened for sensitivity to Ap. The Cmr cassette was removed using the FLP recombinase encoded on pSkippy (68), followed by incubation on TBAS plates to cure pSkippy. Primers 2368C-1 and 2368C-2 were used to confirm the ΔfetP mutation, and the strain was designated KIM6-2088.13. Primer pair Y2368R2 and y2370forF was used to amplify the Cmr cassette from pKD3 and create a ΔfetMP::cam mutation in KIM6-2088.5 carrying red recombinase plasmid pWL204. A mutant strain (designated KIM6-2088.10) was identified by PCR using primers 2368C-1 and y2370forC. pWL204 was eliminated by overnight growth at 37°C, followed by streaking onto TBAS plates. The Cmr cassette was removed using the FLP recombinase encoded on pSkippy, followed by incubation on TBAS plates to cure pSkippy. Primers 2368C-1 and y2370forC were used to confirm the ΔfetMP mutation, and the strain was designated KIM6-2088.12.

Primers Y2367for and Y2367rev were used in concert with pKD3 to delete flpD (y2367) and insert a Cmr cassette into KIM6-2088.5 carrying pWL204. The mutation was confirmed by PCR using primers CM-2 and 2368C-2, and pWL204 was eliminated by overnight growth at 37°C, followed by streaking onto TBAS plates. The Cmr cassette in the resulting strain KIM6-2088.14 was removed using the FLP recombinase encoded on pSkippy, followed by incubation on TBAS plates to cure pSkippy. The ΔflpD mutation was confirmed by PCR using primers d2367-up and d2367-down, and this strain was designated KIM6-2088.15.

The suicide plasmid pCirp498.8 was used as previously described (29) to introduce an irp2::kan2046.1 mutation into Y. pestis strains with mutations in yfe, feo, and fet.

A reexamination of the method originally used to create a deletion in the yfe operon (ΔyfeAB2031.1) (4) revealed that the construct, in addition to removing all of yfeA and part of yfeB, also deleted the putative start codon and 5 bp of the upstream gene (mltE) as well as the intergenic region between mltE and the yfe operon. To ensure that the effects we observed were due to mutations in the yfe operon and did not involve mltE, we generated a new mutation which only affected yfe sequences. All of yfeABC and part of yfeD were removed by digesting pYFE3 with HindIII and PacI, blunt ending with mung bean nuclease, and religating the gel-purified 8.2-kb fragment containing the deletion to create pYFE3ΔPH. A BamHI/blunt-ended SacII fragment carrying the deletion was excised from pYFE3ΔPH and cloned into the SmaI/BamHI sites in pKNG101 to generate the suicide vector pKNGΔyfePH, and the mutation was transferred into KIM6-2088+, generating KIM6-2088.8+.

Separate mutations were constructed in Y. pestis arcA, fnr, rstAB, and oxyR using lambda red recombinase (22), generating strains KIM6-2166+, KIM6-2176+, KIM6-2189+, and KIM6-2190+, respectively. To construct the mutations, a Cmr cassette flanked by arcA, fnr, oxyR, or rstAB sequences was amplified from pKD3 using primer pairs arcA1 and arcA2, fnr1 and fnr2, oxyR1 and oxyR2, or RST-up and RST-down. The PCR products were electroporated into KIM6(pKD46)+ or KIM6(pWL204)+, in the case of oxyR, and the cells were incubated overnight at 30°C. Individual Cmr colonies were screened by PCR to identify those in which the WT gene had been replaced with the Cmr cassette using primer pair arcA3 and arcA4 for arcA. The fnr mutation was confirmed using primer pairs fnr3/fnr4 and fnr4/fnr3.1, as well as fnr4 and Cm-1B. Primer pair Rst-5′ and Rst-3′ was used to verify the rstAB mutation, while primers oxyR3 and CM-2 were used to identify the oxyR mutant.

In vitro cultivation.

All E. coli strains were grown in LB. From −80°C glycerol stocks (6), Y. pestis strains were grown on Congo red (CR) agar at 26 to 30°C (81) before being transferred to TBA slants and incubated overnight at 30°C. Pgm+ strains form red colonies on CR plates at 26 to 34°C; white colonies on these plates were confirmed as Δpgm mutants by PCR as previously described (30).

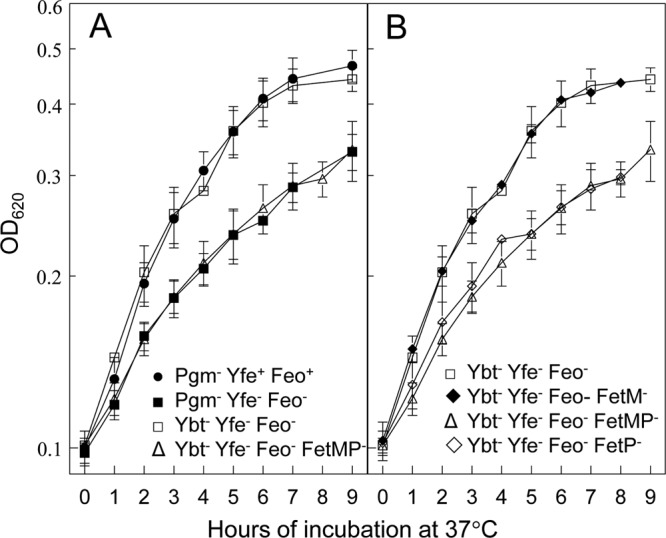

For both aerobic and static growth, cells were washed off the TBA slants with deferrated, defined PMH2 medium and inoculated to an optical density at 620 nm (OD620) of 0.1 into deferrated PMH2 containing 10 μM ferrozine (36, 66). PMH2 was deferrated by extraction with Chelex 100 resin (Bio-Rad Laboratories) (76). The cultures were grown through two transfers for a total of ∼24 h at 37°C and inoculated into fresh media at an OD620 of 0.1, and the optical density was measured at hourly intervals. Aerobic cultures were shaken at 200 to 220 rpm, and the volume of media was ∼10% of the flask capacity. Static cultures were not shaken and the amount of media was ≥50% of the flask or tube capacity. For the experiment in Fig. 2, second-transfer static cultures were inoculated to an OD620 of 0.1 and 1.2-ml aliquots dispensed into 1.5-ml screw-cap microcentrifuge tubes, with OD620 readings performed on individual tubes. All glassware used for Fe-restricted growth studies was soaked overnight in ScotClean (OWL Scientific, Inc.) to remove contaminating metals and copiously rinsed in deionized water.

Fig 2.

Ybt and FetMP contribute to iron-deficient, static growth. Cells were grown at 37°C under static conditions in deferrated PMH2 containing 10 μM ferrozine. Ybt− strains contain a mutation in irp2 and thus are unable to synthesize the Ybt siderophore. The growth curves are averages of three or more independent experiments, with standard deviations indicated by error bars. (A) Pgm− Yfe+ Feo+ (KIM6), Pgm− Yfe− Feo− (KIM6-2088.1), Ybt− Yfe− Feo− (KIM6-2088.5), and Ybt− Yfe− Feo− FetMP− (KIM6-2088.10) strains; (B) Ybt− Yfe− Feo− (KIM6-2088.5), Ybt− Yfe− Feo− FetM− (KIM6-2088.6), Ybt− Yfe− Feo− FetMP− (KIM6-2088.10), and Ybt− Yfe− Feo− FetP− (KIM6-2088.9) strains.

β-Galactosidase assays.

From TBA slants, Y. pestis cells were grown at 37°C in deferrated PMH2 in the presence or absence of 10 μM FeCl3 through 2 transfers for a total of ∼6 generations. Lysates were assayed for enzymatic activity using ONPG (4-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside) as a substrate as previously described (56). For static conditions, cells were grown through 2 transfers for a total of ∼6 generations at 37°C in 10 ml of medium in a 15-ml conical tube without shaking.

Ferrous iron transport studies.

Ferrous iron transport assays were performed using a slight modification of previously published procedures (25, 58, 89). Y. pestis cells were grown in deferrated PMH2 for ∼5 generations prior to use in iron transport assays. Transport was initiated by the addition of 55FeCl3 at a final concentration of 0.2 μCi/ml to cultures containing 5 mM sodium ascorbate. Parallel cultures, preincubated for 10 min with 100 μM carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenylhydrazone (CCCP), were used to demonstrate energy-independent binding. The 55FeCl3 used in the transport studies was diluted into PMH2 containing 100 mM sodium ascorbate, incubated for at least 30 min at room temperature, and filtered through a 0.45-μm filter before being added to the cultures. Samples (0.5 ml) were withdrawn at various times after the addition of the radioactive iron, filtered through 0.45-μm GN-6 nitrocellulose membranes, and rinsed twice with PMH2 medium containing 20 μM FeCl3. The membranes were added to vials containing Bio-Safe II scintillation fluid (Research Products International) and counted in a Beckman LS3801 liquid scintillation counter. Unfiltered samples were used to determine the total amount of radioactivity in each culture. The results are expressed as percent uptake/0.4 OD620 unit to compensate for increases in cell density during the course of the assay.

Virulence testing.

All virulence testing was done in a CDC-approved biosafety level 3 (BSL3) laboratory by following regulations for select agents and University of Kentucky Institutional Biosafety Committee-approved procedures. All animal care and experimental protocols were approved by the University of Kentucky Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Y. pestis strains were transformed with the virulence plasmid pCD1Ap by electroporation (36) and plated on TBA plates containing Ap (50 μg/ml). The plasmid profile of transformants was analyzed as well as their Pgm phenotype on CR agar and Lcr phenotype (encoded on pCD1Ap) on magnesium-oxalate plates (41). Supernatants from cultures grown at 37°C in the absence of CaCl2 were tested for the secretion of LcrV (essential for the Lcr phenotype) by Western blot analysis using polyclonal antisera against histidine-tagged LcrV (31, 34). For subcutaneous infections, overnight cultures of Y. pestis cells grown in heart infusion broth (HIB) at 26°C (to mimic ambient growth temperatures in the flea) were diluted to an OD620 of 0.1 and were incubated in HIB at 26°C until they reached mid-logarithmic phase (OD620 of ∼0.5). Samples were harvested and diluted in mouse isotonic PBS (149 mM NaCl, 16 mM Na2HPO4, 4 mM NaH2PO4). Groups of four 6- to 8-week-old female Swiss Webster (Hsd::ND4; Harlan) mice were injected subcutaneously with 0.1 ml of 10-fold serially diluted bacterial suspensions ranging from 10 to 105 CFU/ml.

Cells used for intranasal infections were grown as described above but in HIB with 2.5 mM CaCl2 and incubated at 37°C (to mimic mammalian temperature for respiratory droplet transmission); cells were similarly diluted in mouse isotonic PBS. Twenty microliters of the bacterial suspension was administered to the nares of mice, alternating aliquots between nostrils. Mice were sedated with 100 μg of ketamine and 10 μg of xylazine/kg of body weight. The actual bacterial doses were determined by plating aliquots of serially diluted suspensions of each dose, in duplicate or triplicate, onto TBA plates containing Ap (50 μg/ml). The colonies were counted on plates incubated at 30°C for 2 to 3 days. Mice were observed daily for 2 weeks, and 50% lethal dose (LD50) values were calculated according to the method of Reed and Muench (70).

RESULTS

Effect of mutations in Y. pestis iron transport systems on in vitro growth under aerobic and static conditions.

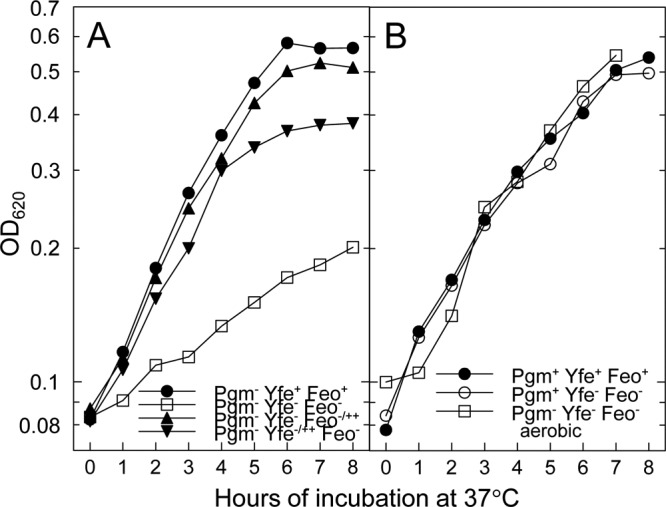

Previously we showed that a Δpgm strain with mutations in both the Yfe and Feo systems (KIM6-2088.1) displayed a severe growth defect under microaerobic, iron-chelated growth conditions, which could be complemented with cloned copies of either the yfe or feo operon (Fig. 1A) (66). However, the same strain grown aerobically did not exhibit any growth defects (Fig. 1B) (66). These results suggest that in Δpgm strains, Y. pestis uses the Yfe and Feo systems for growth in an iron-chelated medium under static conditions but that these systems are not critical for iron-chelated growth under aerobic conditions.

Fig 1.

Growth of Y. pestis strains at 37°C in defined medium under iron-depleted conditions. The indicated strains were grown in deferrated PMH2 with 10 μM ferrozine, and the optical density at 620 nm (OD620) was determined on samples taken at hourly intervals. All strains, except the indicated Pgm− strain in panel B, were grown under static conditions. The growth curves are averages of two independent experiments with nearly identical results. (A) Pgm− Yfe+ Feo+ (KIM6), Pgm− Yfe− Feo− (KIM6-2088.1), Pgm− Yfe− Feo−/++ (KIM6-2088.1[pWSKfeo]), and Pgm− Yfe−/++ Feo− (KIM6-2088.1[pYFE1.2]) strains; (B) Pgm+ Yfe+ Feo+ (KIM6+), Pgm+ Yfe− Feo− (KIM6-2088.1+), and Pgm− Yfe− Feo− aerobic (KIM6-2088.1; aerobic growth) strains. Cloned copies of the yfe operon and the feo operon are carried on pYFE1.2 and pWSKfeo, respectively. Pgm− strains have a 102-kb chromosomal deletion which includes the yersiniabactin (Ybt) iron transport system and the putative Fe2+ transporter FetMP.

Pgm+ Y. pestis strains with mutations in both yfe and feo did not exhibit any growth defects relative to the parent strain, KIM6+, when grown at 37°C under static conditions (Fig. 1B) (66). Since a Δpgm yfeAB feoB mutant does exhibit growth defects under the same conditions, then something encoded within the pgm locus likely contributes to growth under static, iron-chelated conditions. While there are numerous genes within the pgm locus, we focused on the siderophore-dependent yersiniabactin (Ybt) system and the putative FetMP ferrous iron transporter as likely candidates. Although the Ybt siderophore binds ferric, but not ferrous, iron (62), PMH2 medium was prepared aerobically and consequently, contaminating iron would be in the ferric state. Therefore, we constructed a Ybt biosynthetic mutant in the yfe feo mutant background by inserting a kanamycin resistance gene cassette (kan) into the first gene (irp2) in the Ybt biosynthetic operon and examined the growth characteristics of this triple mutant under static conditions. The irp yfeAB feoB mutant exhibited a modest growth defect, but not as severe as that of the Δpgm yfeAB feoB mutant (Fig. 2A), suggesting that the Ybt system contributes to iron acquisition under the static growth conditions used here but does not account for all of it.

In Y. pestis, fetM is predicted to encode a 71.2-kDa IM permease, while FetP is a putative periplasmic protein with a processed mass of 16.7 kDa. Both proteins have recently been characterized in E. coli and are distantly related to the Ftr ferrous transport system of Saccharomyces cerevisiae and other fungi (33, 50). The growth defect of a quadruple irp2 yfeAB feoB fetMP mutant under static, iron-chelated conditions was nearly identical to that of the Δpgm yfeAB feoB mutant (Fig. 2A). Surprisingly, an irp2 yfeAB feoB fetM quadruple mutant did not show as severe a growth defect as did the irp2 yfeAB feoB fetMP mutant but instead was similar to the irp2 yfeAB feoB mutant (Fig. 2B). However, an irp2 yfeAB feoB fetP mutant did have the same static growth defect as the irp2 yfeAB feoB fetMP strain (Fig. 2B). These results suggest that the Fet system contributes to static iron acquisition, with FetM being nonessential.

A variety of approaches were taken to try to complement the defects in the irp2 yfeAB feoB fetMP or irp2 yfeAB feoB fetP mutant. A recombinant plasmid, pWSKfetMPAS, which expresses fetMP from its native promoter did not restore growth to either of these strains. Likewise, fetP under the control of an arabinose-inducible promoter in pBADFetP failed to complement the growth defect in the irp2 yfe feoB fetP mutant (KIM6-2088.9) as well as in a strain (KIM6-2088.12) with the cam resistance cassette removed. Finally, we restored the wild-type fetMP locus in KIM6-2088.9 by integrating pKNGFetP, yielding an fetMP+ genotype with the suicide vector between fetMP and the downstream genes. This strain showed the same growth defect as its irp2 yfeAB feoB fetP parent (data not shown), suggesting that one or more downstream genes play a role in the mutant phenotype.

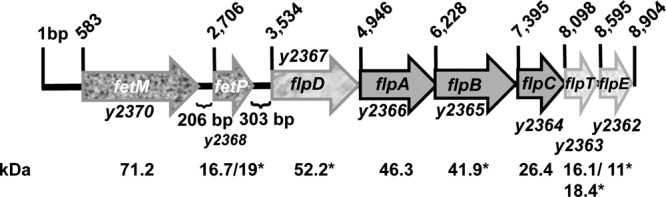

Examination of the region downstream of fetMP revealed the presence of a putative 6-gene operon, flpDABCTE (Fig. 3). All reading frames of these downstream genes overlap or have very small gaps between them. Although the downstream genes are in the same orientation as fetMP, there is a >300-bp gap between the stop codon for fetP and the putative start codon of flpD. FlpA and FlpB are predicted ABC permeases for export of antimicrobial peptides, while FlpC is the associated ATPase. FlpD is a predicted IM protein with a partial YHS domain, found in copper-transporting ATPases, but lacks two cysteine residues within this domain thought to be important for its function. FlpT is a TlpA-like family member. Proteins in this family have a thioredoxin-like domain in the periplasm with putative disulfide reductase activity and roles in cytochrome maturation and sulfoxide reductase recycling. FlpT is a predicted periplasmic protein with a processed signal sequence (Fig. 3). Finally, FlpE is a cytochrome c superfamily member (55).

Fig 3.

Genetic organization of the fetMP-flpDABCTE (y2370-y2362) locus in Y. pestis KIM. Arrows indicate the direction of transcription of the genes in the ∼9-kb locus and are drawn to scale. A small open reading frame (oppositely oriented and upstream of fetP) potentially encoding a 67-amino-acid protein (Y2369) is annotated in Y. pestis KIM10+ but not in most other sequenced Y. pestis genomes (33). Predicted protein masses are shown with both processed and unprocessed masses where signal sequence cleavage is predicted. Protein masses with an asterisk indicate that the Y. pestis CO92 genome annotated starts, which were used in calculating molecular masses, differed from that in Y. pestis KIM (23, 60).

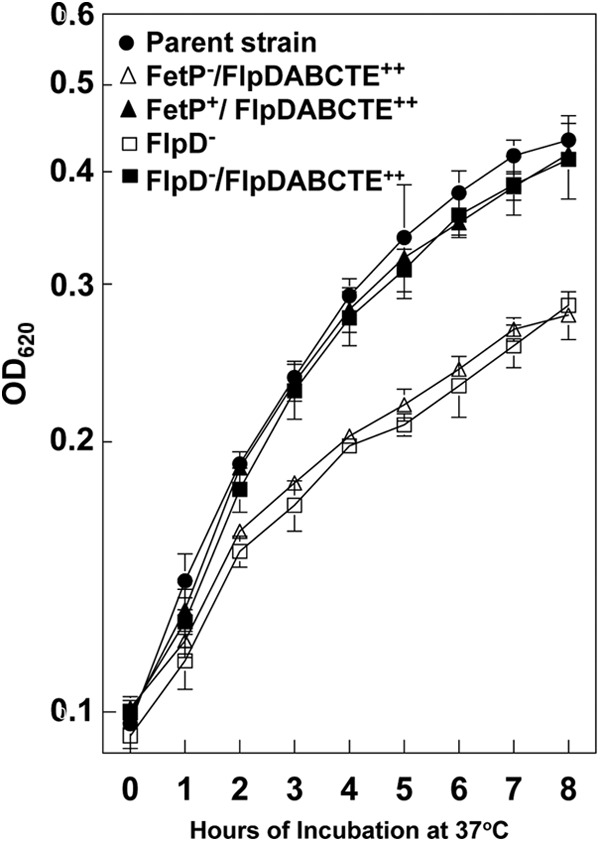

We constructed a ΔflpD mutation via red recombinase in a strain with the irp2 yfeAB feoB background. The irp2 yfeAB feoB flpD and irp2 yfeAB feoB fetP mutant genotypes caused nearly identical growth defects. We cloned flpDABCTE behind an IPTG-inducible promoter, and the resulting plasmid (pProEX-2367.11-1) restored the growth of the irp2 yfeAB feoB flpD mutant (KIM6-2088.15) to that of the parent strain (Fig. 4). This indicates that one or more of the flpDABCTE locus genes play a role in the iron-deficient, static growth of Y. pestis. pProEX-2367.11-1 failed to restore growth to the fetP mutant (KIM6-2088.13) but did complement KIM6-2088.16 (the fetP mutant containing the integrated suicide vector which restores fetMP) (Fig. 4). Thus, the growth defect in our fetP mutant results from a combination of the fetP mutation and apparent downstream effects on the flpDABCTE genes.

Fig 4.

FetP and one or more gene products of the flpDABCTE locus contribute to iron-deficient, static growth. Cells were grown at 37°C under static conditions in deferrated PMH2 containing 10 μM ferrozine. The growth curves are averages of three or more independent experiments, with standard deviations indicated by error bars. All strains have an irp2 yfeAB feoB background (parent strain KIM6-2088.5 [solid circles]) and are unable to synthesize the Ybt siderophore. Open triangles, strain KIM6-2088.13(pProEX-2367.11-1) (FetP−/FlpDABCTE++); solid triangles, strain KIM6-2088.16(pProEX-2367.11-1) (FetP+/FlpDABCTE++); open squares, strain KIM6-2088.15(pProEX-1) (FlpD−); solid squares, strain KIM6-2088.15(pProEX2367.11-1) (FlpD−/FlpDABCTE++).

KIM6-2088.10 (irp2 yfeAB feoB fetMP) is severely impaired in ferrous iron transport.

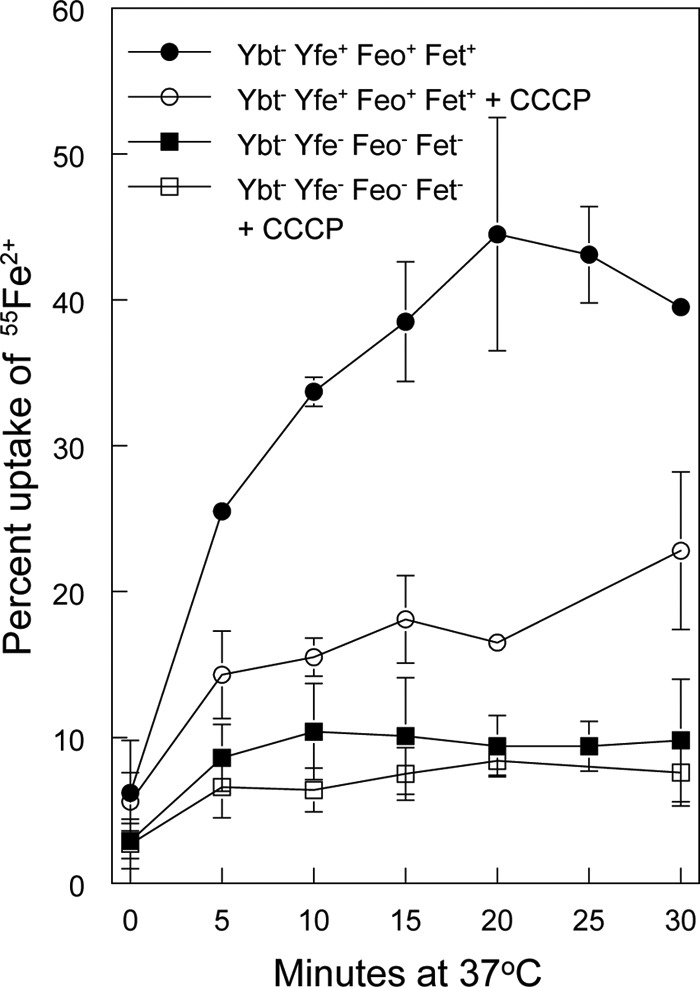

To directly demonstrate that the irp2 yfeAB feoB fetMP mutant was defective in ferrous iron transport, we performed uptake assays. The reactions were carried out in the presence of ascorbate to reduce 55Fe3+ to 55Fe2+. An irp2 mutant displayed rapid uptake of radiolabeled ferrous iron, which plateaued at approximately 40% after 15 min of incubation at 37°C (Fig. 5). This uptake was energy dependent, as revealed by the substantial decrease in cell-associated isotope that occurred when cells were pretreated with CCCP. Relative to the CCCP-treated control, very little iron was taken up by the quadruple mutant KIM6-2088.10 (irp2 yfeAB feoB fetMP [Fig. 5]), indicating that this mutant is defective in the transport of ferrous iron.

Fig 5.

The ybt yfe feo fetMP mutant is defective in ferrous iron transport. The uptake of radiolabeled iron by Y. pestis strains KIM6-2046.1 (Ybt− Yfe+ Feo+ Fet+ [circles]) and KIM6-2088.10 (Ybt− Yfe− Feo− FetMP− [squares]) incubated at 37°C in the presence of ascorbate was monitored over time. Cells were poisoned metabolically by incubation for 10 min with CCCP before the addition of the isotope (open symbols). The uptake curves are averages of replicate experiments, with standard deviations indicated by error bars.

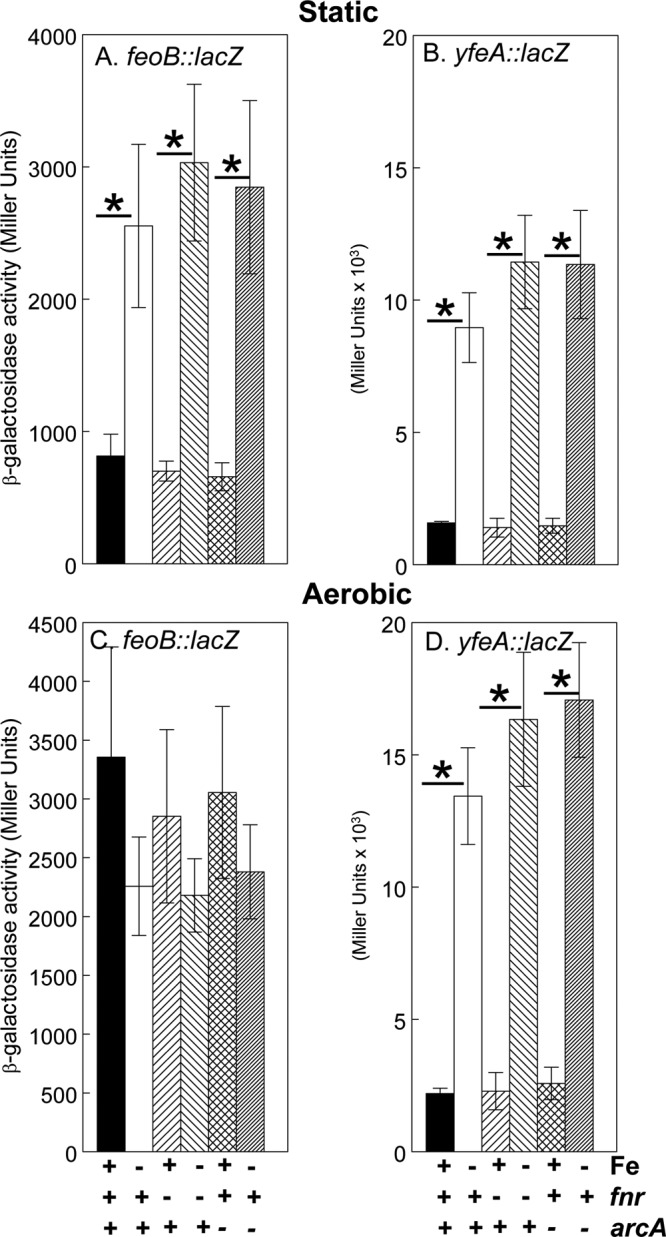

Regulation of the feo operon.

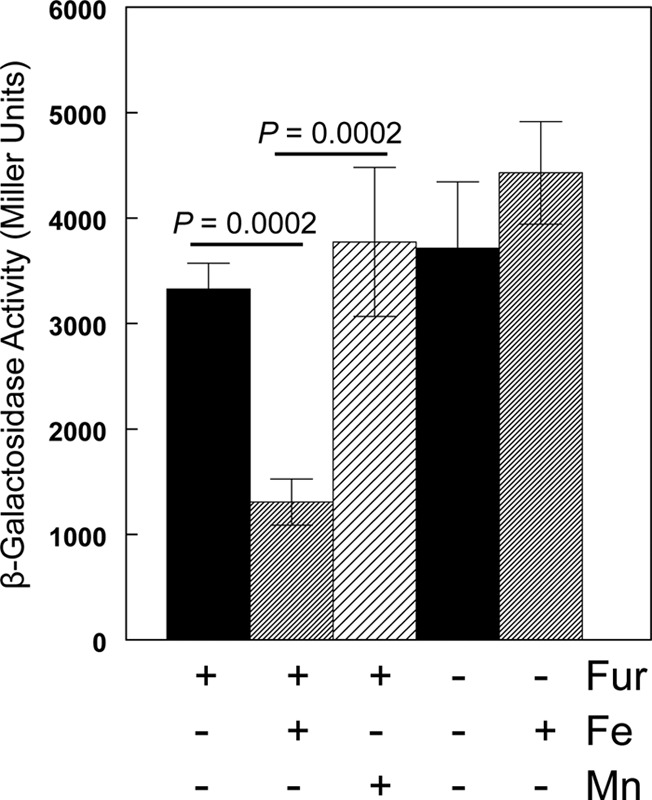

To examine the factors that affect expression of feo, we used Mu dI1734 to create an feoB::lacZ transcriptional reporter in pWSKfeo. KIM6 (Δpgm [Ybt− Fet−] Fur+ Yfe+ Feo+) carrying this reporter plasmid, pWSKfeoMu-2, was grown in deferrated PMH2 in the presence and absence of iron under aerobic and static conditions. Growth of KIM6(pWSKfeoMu-2) under static conditions in the presence of 10 μM iron repressed expression of the feo operon ∼3-fold (Fig. 6). Similar results were obtained with the same reporter plasmid in KIM6+ (Pgm+ [Ybt+ Fet+] Fur+ Yfe+ Feo+) (data not shown). This repression was relieved in a Y. pestis strain that has a mutation in fur. In contrast to the yfeA promoter (5, 61), surplus manganese (10 μM) did not repress expression of the feoB::lacZ reporter during static growth (Fig. 6).

Fig 6.

Effects of iron, manganese, and Fur on the activity of the feoB reporter. KIM6 (Δpgm Fur+) or KIM6-2030 (Δpgm fur::kan-9) carrying pWSKfeoMu-2 (feoB::lacZ reporter) was grown at 37°C in deferrated PMH2 in the presence or absence of 10 μM FeCl3 or MnCl2 under static conditions. Activities are averages from multiple samples from two or more independent experiments, expressed in terms of Miller units. Standard deviations are indicated by the vertical bars, and statistically significant differences are indicated.

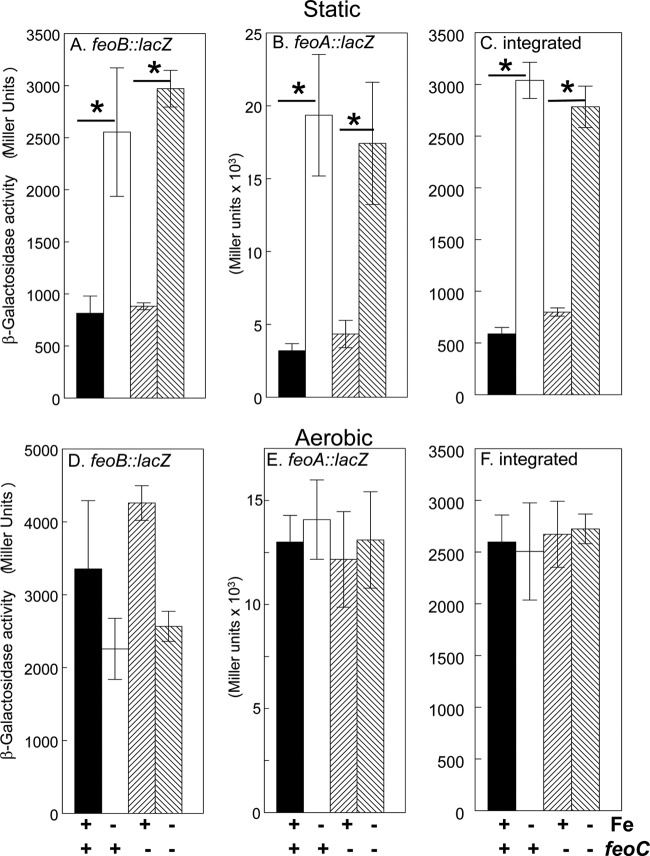

E. coli FeoC contains motifs reminiscent of transcriptional regulators (12). A recent report suggests that in Y. pestis KIM strains, FeoC functions as a transcriptional repressor. In that study, an feoC mutant had increased resistance to certain antimicrobial peptides. Similar results were obtained by overexpressing feoAB, leading the authors to conclude that FeoC was repressing expression of the feo operon (38). In our hands, the expression of the feoB::lacZ reporter was unaffected by a mutation in feoC (Fig. 7A and D). However, pWSKfeoMu-2 contains the entire feoABC operon with Mu disrupting feoB. The transcriptional terminators within Mu likely prevent transcription of feoC in pWSKfeoMu-2. Nonetheless, to ensure that the copy of feoC on pWSKfeoMu-2 was not complementing the chromosomal feoC mutation, we constructed a reporter consisting of only the promoter region of the feo operon inserted upstream of lacZ (pWSKfeoA::lac [see Table S1 in the supplemental material]) to ensure that only the mutated version of feoC was present. A comparison of this promoter in the parent strain (feoABC+) and the feoC mutant (Fig. 7B and E) showed that neither iron regulation nor the levels of expression were affected by the feoC mutation under static or aerobic growth conditions. Finally, to ensure that plasmid copy number was not affecting the ability of FeoC to repress transcription of the feo::lacZ constructs in pWSK129, we integrated the feoA::lacZ reporter into the Y. pestis chromosome at the invA locus. The integrated reporter behaved the same as the plasmid constructs (Fig. 7C and F). Thus, under the conditions we have tested, FeoC does not affect transcription of the feo operon.

Fig 7.

Effects of iron, FeoC, and aeration on the activity of feo reporter genes. KIM6+ (feoABC+) and KIM6-2121(pKD46)+ (feoC mutant) cells carrying either pWSKfeoMu-2 (A and D) or pWSKfeoA::lacZ (B and E) as well as KIM6-2191+ (feoABC+) and KIM6-2191.1+ (feoC mutant) with an integrated feoA::lacZ reporter (C and F) were grown at 37°C in deferrated PMH2 in the presence or absence of 10 μM FeCl3 under static (A, B, and C) or aerobic (D, E, and F) conditions. Samples were harvested for β-galactosidase assays during mid-log phase. Activities are averages from multiple samples from two or more independent experiments, expressed in terms of Miller units. Standard deviations are indicated by the vertical bars. Under static growth conditions, expression levels for all three reporters were significantly reduced (P < 0.00001 [*]) by iron supplementation to 10 μM compared to those with no iron addition to deferrated PMH2.

Curiously, under aerobic conditions, the activities of all the feo reporters were essentially the same whether the cells were grown with or without added iron (Fig. 7D, E, and F). These values were equivalent to those obtained in cells grown under iron-deficient, static conditions. Thus, under aerobic conditions, the expression of the feo operon was not repressed by iron (Fig. 7).

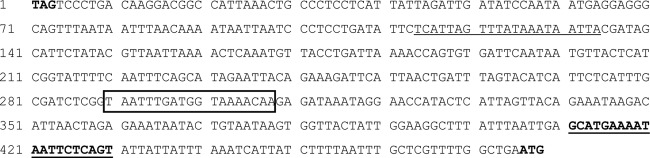

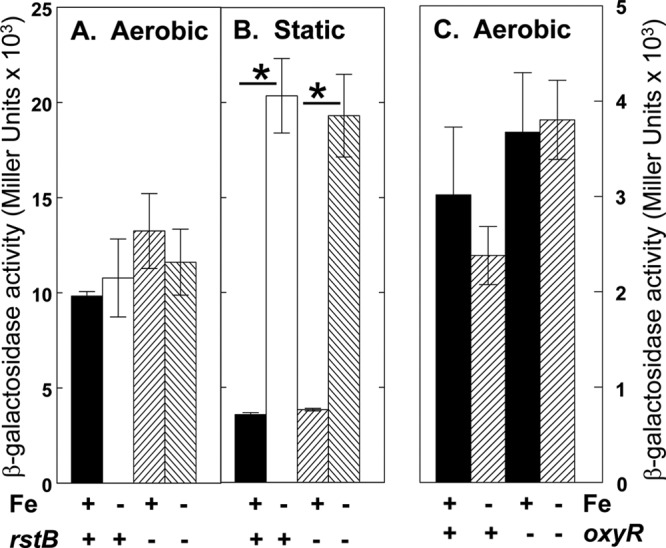

We next tried to identify the mechanism that prevents Fe-Fur repression of the Y. pestis feo promoter during aerobic growth. Expression of the feo operon is positively regulated by Fnr in both E. coli and Shigella (7, 46). In Shigella, expression of feo is also induced by ArcA (7). The Y. pestis feoABC promoter region contains potential binding sites for both ArcA and Fnr upstream of the Fur binding site (Fig. 8). Thus, we reasoned that Fnr and possibly ArcA might override iron regulation aerobically. However, fnr and arcA mutant strains did not differ significantly from the parent strain in the expression of either the feoB::lacZ or feoA::lacZ reporters—once again, iron did not repress expression under aerobic conditions (Fig. 9A and C and data not shown). We also examined the expression of a yfeA::lacZ reporter. Aerobic versus static growth did not have a significant effect on the expression of this reporter, and transcription from the yfeA promoter was repressed by iron under both aerobic and static conditions. As with the feo reporter, mutations in fnr or arcA did not significantly affect transcription from the yfeA promoter (Fig. 9B and D).

Fig 8.

Y. pestis feoABC promoter region. Bold letters at the beginning and end of the sequence correspond to the stop codon for the upstream gene and the predicted start codon for feoA, respectively. Bases enclosed within the box indicate a possible Fnr binding site. Underlined residues are the best match to a predicted ArcA motif in Shigella (7), while bold and underlined bases have been shown to bind Fur (35).

Fig 9.

Neither the feo nor the yfe operon is regulated by fnr or arcA. KIM6+ (ArcA+ Fnr+), KIM6-2166(pKD46)+ (arcA mutant), and KIM6-2176(pKD46)+ (fnr mutant) carrying pWSKfeoMu-2 (feoB::lacZ) (A and C) or pEUYfeA (yfeA::lacZ) (B and D) were grown in the presence or absence of 10 μM FeCl3 at 37°C under static (A and B) or aerobic (C and D) conditions in deferrated PMH2. Samples were taken during mid-log phase for β-galactosidase assays. Activities are averages from multiple samples from two or more independent experiments and are expressed in Miller units. Vertical bars represent standard deviations. Under aerobic growth conditions, yfeA reporter expression levels for all three strains (parent and arc and fnr mutants) were significantly reduced (P = 0.0002 or less) by iron supplementation to 10 μM compared to levels with no iron addition to deferrated PMH2 (*). Under static conditions, iron repressed both the feoB::lacZ and yfeA::lacZ reporters in all three strains (P = 0.029 or less [*]).

In Salmonella, feo transcription is activated by RstA, a response regulator that is induced by the PhoP/PhoQ system and binds directly to sites within the feoA promoter when the cells are grown in the presence of iron (19, 45). To determine if RstA was responsible for the activity of Y. pestis feo in cells grown aerobically in the presence of iron, we constructed a ΔrstAB::cam strain. Expression of the feoA::lacZ reporter in the rstAB mutant grown under static and aerobic conditions was essentially the same as in the parent strain (Fig. 10A and B).

Fig 10.

The Y. pestis feo operon is not regulated by RstAB or OxyR. KIM6+ (OxyR+ RstAB+) and KIM6-2189(pKD46)+ (rstAB mutant) cells carrying pWSKfeoA::lacZ (A and B) or KIM6-2190(pWL204)+ (oxyR mutant) cells containing pWSKfeoMu-2 (C) were grown under aerobic (A and C) or static (B) conditions in deferrated PMH2 in the presence or absence of 10 μM FeCl3 at 37°C. Samples for β-galactosidase assays were removed during mid-log phase. Activities, expressed as Miller units, are averages from multiple samples from two or more independent experiments, with vertical bars indicating the standard deviations. Under static conditions, iron repressed the feo reporter in the parent and rstB mutant strains (P = 0.029 or less [*]).

We also considered the possibility that the expression of feo under aerobic conditions might respond to the oxidative stress regulator, OxyR (78). However, the β-galactosidase activity of the pWSKfeoMu-2 reporter in an oxyR mutant grown under aerobic conditions was not significantly different from that in the parent strain (Fig. 10C).

Since our static growth conditions might have additional effects such as altered nutrient access due to the settling of Y. pestis cells, we also tested expression of the feoB::lacZ reporter in the fnr, arcA, and oxyR mutants under conditions where all cultures were shaken and had the same liquid-to-air ratio. For these studies, 5-ml cultures were grown through 2 transfers in 50-ml conical tubes in BBL GasPak chambers with or without BD GasPak EZ gas-generating sachets at 37°C in a shaking incubator. Samples were harvested for β-galactosidase assays. These experiments also failed to show regulation by Fnr, ArcA, or OxyR (data not shown), yielding results similar to those we obtained with static cultures. These results and those in Fig. 1 (static versus aerobic growth) indicate that our static cultures were functionally equivalent to microaerobic conditions, at least for Y. pestis.

Roles of the feo and yfe systems in mouse models of bubonic and pneumonic plague.

In outbred Swiss Webster mice, a fully virulent strain of Y. pestis [KIM5(pCD1Ap)+] has an LD50 of ∼300 cells by an intranasal route of infection, which mimics pneumonic plague. Strains with single mutations in yfeAB or feoB as well as an yfeAB feoB double mutant were as virulent as the parent Yfe+ Feo+ strain when administered in this manner (Table 1). By a subcutaneous route of infection, the LD50 of KIM5(pCD1Ap)+ is ∼23 cells in Swiss Webster mice. The ΔfeoB mutant had no significant reduction in virulence, while the ΔyfeAB mutant showed a modest but consistent 10-fold loss of virulence compared to the parent strain, which was not statistically significant (P = 0.55) (Table 1). In a previous study we reported that the same ΔyfeAB mutation caused an ∼76-fold loss of virulence compared to the parent Yfe+ strain. However, the strains used for those experiments had additional mutations in an adhesin (encoded by psa) and a type III secretion effector protein (encoded by yopJ) (4). Thus, the combination of the yfe mutation with mutations in psa and yopJ likely led to a greater loss in virulence. The ∼10-fold loss of virulence shown here by the yfe mutant in an otherwise WT background is a more realistic reflection of the role of Yfe in bubonic plague.

Table 1.

LD50 values for Y. pestis strains in mouse models of pneumonic and bubonic plague

| Strain | LD50a in plague model |

|

|---|---|---|

| Pneumonic plague | Bubonic plague | |

| KIM5(pCD1Ap)+ | 329 ± 105 | 23 ± 14 |

| KIM5-2031.12(pCD1Ap)+ (ΔyfeAB) | 139 ± 142 | 205 ± 149 |

| KIM5-2088(pCD1Ap)+ (ΔfeoB) | 211 ± 182 | 55 ± 48 |

| KIM5-2088.1(pCD1Ap)+ (ΔyfeAB ΔfeoB) | 407 ± 59 | 2,035 ± 842 |

| KIM5-2088.8(pCD1Ap)+ (ΔyfeABCD ΔfeoB) | Not tested | 1,616 ± 87 |

LD50 values are the averages of two or more independent studies, with standard deviations.

In contrast, a strain with a mutation in both yfeAB and feoB had an ∼90-fold loss in virulence compared to that of the Yfe+ Feo+ parent, KIM5(pCD1Ap)+ (P = 0.0015), and an ∼10-fold loss relative to that of the ΔyfeAB single mutant (P = 0.0146) (Table 1). This suggests that both the Yfe and Feo systems play roles in the progression of bubonic plague.

During the course of these studies, we discovered that the ΔyfeAB mutation (made in the pregenomic era) also deleted a portion of the upstream gene, mltE. mltE has an open reading frame with a superfamily domain involved in the hydrolysis of β-1,4-linked polysaccharides (2). To determine whether our results were due to the mltE mutation, we constructed a ΔyfeABCD2031.4 mutation in which the upstream mltE gene is intact. In vitro static growth studies showed that the Pgm− ΔyfeABCD ΔfeoB mutant had a growth defect identical to that of the old Pgm− ΔyfeAB ΔfeoB mutant (data not shown). In addition, the new Pgm+ ΔyfeABCD ΔfeoB Lcr+ derivative exhibited a loss of virulence nearly identical to that of the old Pgm+ ΔyfeAB ΔfeoB Lcr+ mutant compared to the virulence of Yfe+ Feo+ Lcr+ parent (Table 1). Thus, neither the in vitro or in vivo phenotypes were affected by the inadvertent mltE mutation.

DISCUSSION

This study examined the role of the Yfe and Feo systems during in vitro growth and in mouse models of bubonic and pneumonic plague as well as regulation of the feo operon in Y. pestis. The Yfe system is an ABC transporter that was first identified in Y. pestis and is closely related to the Sit system, which was subsequently characterized in other Enterobacteriaceae (4, 72, 91). The Yfe/Sit systems transport manganese and ferrous iron (4, 32, 48). The Feo system was initially identified in E. coli as a ferrous iron transporter (40, 46). The feo operon consists of anywhere from 1 to 3 genes depending upon the bacterial species (12). FeoB is present in all bacterial strains that possess the Feo system. The functions of the two small proteins encoded by feoA and feoC are unknown, but FeoA contains an Src homology 3 (SH3) domain that is associated with protein-protein interactions, while FeoC is predicted to have a winged-helix motif found in transcriptional repressors (12).

The Yfe/Sit and/or Feo systems have been shown to be important for in vitro, iron-depleted growth in a number of bacteria under either aerobic or anaerobic conditions (43, 57, 71, 73). In Y. pestis, the Yfe and Feo systems are required for efficient growth under static conditions (66). Given that the Yfe and Feo systems transport ferrous iron, it is perhaps not surprising that cells with mutations in these systems only show defects when grown under static conditions that favor the maintenance of iron in a ferrous state. The effects are additive—a yfeAB feoB double mutant has a more severe growth defect than either of the single mutants. In addition, the phenotype of the double mutant is masked by the presence of the pgm locus (Fig. 1) (66), which encodes both the Ybt and FetMP systems. An irp2 mutation, which prevents Ybt synthesis, in a yfeAB feoB background showed a modest growth defect (Fig. 2). Deletion of fetMP in addition to mutations in the other three systems was required to yield a growth phenotype similar to that of the Δpgm yfeAB feoB mutant (Fig. 2). FetMP has previously been implicated in iron acquisition in a marine magnetotatic bacterium (24) and more recently in E. coli (50). In E. coli, FetM was found to be essential, with FetP required for maximum growth at low iron concentrations or in the presence of ferric iron (50). An FetP ortholog, P19, was identified in Campylobacter jejuni (44, 86). Both FetP and P19 exist as a homodimer in the periplasm and have been shown to bind copper and iron. In C. jejuni, P19 was needed for iron-deficient growth (16, 50). The role of the FetM ortholog in Campylobacter has not been tested. In Y. pestis, a mutation in fetP, but not in fetM, caused a growth defect similar to that of the fetMP deletion mutant (Fig. 2B). It is unclear why FetM is essential in E. coli but not in Y. pestis. The predicted products are 69.3% identical over 635 amino acids. Perhaps in Y. pestis something else can serve the function of FetM in the fetM mutant.

Our inability to complement the growth defect of the fetP mutant with the cloned fetP gene alone led to the identification of a putative 6-gene operon (designated flpDABCTE) located downstream of fetMP which also appears to be involved in the growth of Y. pestis under static, iron-restricted conditions. Our data indicate that fetP works in conjunction with the downstream genes, since the cloned flp operon could complement the flpD mutant as well as KIM6-2088.16 (a strain containing the integrated suicide vector which restores fetMP but would prevent any transcriptional read-through of the downstream genes) but not the fetP mutant (KIM6-2088.13) (Fig. 4). These data also suggest that there is a link between the transcription of fetP and expression of the downstream genes despite the intervening ∼300 bp between the stop codon for fetP and the putative start codon for flpD. Further studies will be necessary to determine if the flp operon is cotranscribed with fetMP.

The flp operon is present in a variety of other bacteria, including C. jejuni, some E. coli strains, Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (but not Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi), and Shigella flexneri, and is located adjacent to an fetMP-like operon. Not all of the flp genes are present in other bacterial species. Organisms with flp-like sequences have genes related to flpD (the first gene in the operon) as well as flpABC, encoding the ABC transporter, and flpT, encoding the thioredoxin, with the flpE sequences either missing or replaced by the sequence for another putative thioredoxin. In C. jejuni, the downstream genes (designated Cj1660-1665 in strain NCTC11168) as well as P19 and Cj1658 (the fetM ortholog) have been shown to be regulated by iron and repressed by Fur (42, 59, 86). Whether these flp-related sequences play a role in iron transport in these other species is unknown. Likewise, it is not known if all of the flp genes are needed for iron-deficient, static growth of Y. pestis.

Previous studies showed that both feoA and feoB, but not feoC, are required for static growth of Y. pestis (66). Here we showed that an feoC mutation had no effect on expression of the feo operon (Fig. 7). Of the three proteins predicted to be encoded by the feo operon, FeoC is the least conserved, with the gene entirely missing from some organisms (12). Relative to E. coli and Shigella FeoC, Y. pestis has 7 additional amino acids and diverges significantly at the carboxy-terminal end, which might explain any differences observed between the function of FeoC in Y. pestis versus other Enterobacteriaceae.

Recently, Guo et al. observed that a transposon insertion into, or deletion of, feoC resulted in increased sensitivity of Y. pestis KIM strains to polymyxin B. Overexpression of feoAB yielded a similar phenotype (38). Based on these data, and the predicted LysR-like winged-helix N-terminal motif (12), Guo et al. proposed that the Y. pestis FeoC is a regulator of feoAB that represses expression in vitro (38). However, our studies using transcriptional reporters failed to show any regulatory effects on transcription from the feo promoter in vitro due to an feoC mutation (Fig. 7). Thus, any role for FeoC in the Feo system and the mechanism for increased sensitivity to polymyxin B remain to be clearly elucidated.

The Yfe/Sit and/or Feo systems have been implicated in the virulence of several bacterial species (8, 32, 43, 57, 71, 74, 77, 84, 87, 90). Previous studies from our laboratory have shown that the siderophore Ybt plays a major role in the virulence of bubonic and pneumonic plague (3, 27, 28). Mutants unable to produce Ybt are avirulent by subcutaneous routes of infection in mice and are drastically reduced in virulence by an intranasal route of infection. However, the Ybt system is apparently not required once the organisms enter the bloodstream, as Δpgm strains are still fully virulent when administered intravenously. The intravenous model in mice mimics septicemic plague, which bypasses the early lymphatic stage of bubonic plague (4, 85). Instead the Yfe system comes into play, since Δpgm strains with a mutation in yfe are now avirulent by an intravenous route. Yfe mutants also show a modest loss of virulence by a subcutaneous route of infection (4). Here we show that an feo mutant did not have any apparent defect in virulence by a peripheral route of infection, while the yfe feo double mutant showed a greater reduction in virulence than the single yfe mutant (70- to 88-fold versus 9-fold). This suggests that these two systems play partially redundant roles in vivo that cannot be performed by systems present in the pgm locus (i.e., Ybt and/or FetMP). This reflects a difference from our in vitro studies where the Ybt system has to be absent in order to see a defect in growth.

Yfe and Feo do not appear to play significant roles in pneumonic plague in mice. The double mutant was still fully virulent via an intranasal route. Several studies indicate that the lungs present pathogens with an iron-deficient environment. For example, Pseudomonas siderophores have been detected in the sputum of infected cystic fibrosis patients. In addition, mutations in the siderophore receptor LbtU in Legionella and the Ybt siderophore system of Y. pestis cause a significant loss of virulence during pneumonic infections (17, 28, 51). Thus, it would appear that in Y. pestis, ferric iron transport via the Ybt system plays a more important role than ferrous iron transport in a pneumonic mouse model of plague. However, at present we cannot rule out the possibility that other ferrous iron transporters compensate for the loss of the Yfe and Feo systems in pneumonic plague. These results highlight our and others' previous findings that different iron transport systems may be required for growth at various times during infection and/or in different host organs (4, 9).

In various bacterial systems, feo has been shown to be repressed by Fur in the presence of iron and activated by Fnr, ArcA, and/or RstA (7, 19, 45, 46). Y. pestis feo was repressed by Fur but only under static conditions. Individual mutations in feoC, fnr, arcA, or rstAB did not affect the expression of the Y. pestis feo operon under either aerobic or static conditions. An oxyR mutation did not affect transcription of the feo operon under aerobic conditions (Fig. 7, 9, and 10). The inability of iron to repress feo expression under aerobic conditions is puzzling. There are other examples where feo transcription is not repressed by iron (1, 82), but to our knowledge, this is the first instance of an iron transport system which is iron and Fur regulated under static conditions but not during aerobic growth. Clearly, Fur is still present and active under aerobic conditions, as shown by its ability to inhibit the expression of other Y. pestis iron transport systems such as Ybt, Yfe, Fet, Efe, and Hmu (5, 26, 27, 63, 83). We are investigating precisely what components are involved in overriding iron repression of the feo operon in Y. pestis under aerobic conditions.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was partially supported by Public Health Service grant AI033481 from the National Institutes of Health.

We thank Justin Radolf for thoughtful discussions on divalent cation transport, regulation, and homeostasis.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 27 August 2012

This article is dedicated to Jorge Crosa (1941-2012), a leader in the field of iron transport and regulation and a good friend. He will be greatly missed.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://iai.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1. Anaya-Bergman C, et al. 2010. Porphyromonas gingivalis ferrous iron transporter FeoB1 influences sensitivity to oxidative stress. Infect. Immun. 78:688–696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Artola-Recolons C, et al. 2011. High-resolution crystal structure of MltE, an outer membrane-anchored endolytic peptidoglycan lytic transglycosylase from Escherichia coli. Biochemistry 50:2384–2386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bearden SW, Fetherston JD, Perry RD. 1997. Genetic organization of the yersiniabactin biosynthetic region and construction of avirulent mutants in Yersinia pestis. Infect. Immun. 65:1659–1668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bearden SW, Perry RD. 1999. The Yfe system of Yersinia pestis transports iron and manganese and is required for full virulence of plague. Mol. Microbiol. 32:403–414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bearden SW, Staggs TM, Perry RD. 1998. An ABC transporter system of Yersinia pestis allows utilization of chelated iron by Escherichia coli SAB11. J. Bacteriol. 180:1135–1147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Beesley ED, Brubaker RR, Janssen WA, Surgalla MJ. 1967. Pesticins. III. Expression of coagulase and mechanism of fibrinolysis. J. Bacteriol. 94:19–26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Boulette ML, Payne SM. 2007. Anaerobic regulation of Shigella flexneri virulence: ArcA regulates fur and iron acquisition genes. J. Bacteriol. 189:6957–6967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Boyer E, Bergevin I, Malo D, Gros P, Cellier MFM. 2002. Acquisition of Mn(II) in addition to Fe(II) is required for full virulence of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Infect. Immun. 70:6032–6042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Brickman T, Armstrong S. 2009. Temporal signaling and differential expression of Bordetella iron transport systems: the role of ferrimones and positive regulators. Biometals 22:33–41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Brickman TJ, Hanawa T, Anderson MT, Suhadolc RJ, Armstrong SK. 2008. Differential expression of Bordetella pertussis iron transport system genes during infection. Mol. Microbiol. 70:3–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Brickman TJ, Vanderpool CK, Armstrong SK. 2006. Heme transport contributes to in vivo fitness of Bordetella pertussis during primary infection in mice. Infect. Immun. 74:1741–1744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cartron ML, Maddocks S, Gillingham P, Craven CJ, Andrews SC. 2006. Feo—transport of ferrous iron into bacteria. Biometals 19:143–157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Casadaban MJ. 1975. Fusion of the Escherichia coli lac genes to the ara promoter: a general technique using bacteriophage Mu-1 insertions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 72:809–813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Castilho BA, Olfson P, Casadaban MJ. 1984. Plasmid insertion mutagenesis and lac gene fusion with mini-Mu bacteriophage transposons. J. Bacteriol. 158:488–495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cavanaugh DC, Randall R. 1959. The role of multiplication of Pasteurella pestis in mononuclear phagocytes in the pathogenesis of flea-borne plague. J. Immunol. 83:348–363 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chan ACK, et al. 2010. Structure and function of P19, a high-affinity iron transporter of the human pathogen Campylobacter jejuni. J. Mol. Biol. 401:590–604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chatfield CH, Mulhern BJ, Burnside DM, Cianciotto NP. 2011. Legionella pneumophila LbtU acts as a novel, TonB-independent receptor for the legiobactin siderophore. J. Bacteriol. 193:1563–1575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cherepanov PP, Wackernagel W. 1995. Gene disruption in Escherichia coli: TcR and KmR cassettes with the option of Flp-catalyzed excision of the antibiotic-resistance determinant. Gene 158:9–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Choi E, Groisman EA, Shin D. 2009. Activated by different signals, the PhoP/PhoQ two-component system differentially regulates metal uptake. J. Bacteriol. 191:7174–7181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cianciotto N. 2007. Iron acquisition by Legionella pneumophila. Biometals 20:323–331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Crosa JH, Mey AR, Payne SM. (ed). 2004. Iron transport in bacteria. ASM Press, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 22. Datsenko KA, Wanner BL. 2000. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:6640–6645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Deng W, et al. 2002. Genome sequence of Yersinia pestis KIM. J. Bacteriol. 184:4601–4611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Dubbels BL, et al. 2004. Evidence for a copper-dependent iron transport system in the marine, magnetotactic bacterium strain MV-1. Microbiology 150:2931–2945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Evans SL, Arceneaux JEL, Byers BR, Martin ME, Aranha H. 1986. Ferrous iron transport in Streptococcus mutans. J. Bacteriol. 168:1096–1099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Fetherston JD, Bearden SW, Perry RD. 1996. YbtA, an AraC-type regulator of the Yersinia pestis pesticin/yersiniabactin receptor. Mol. Microbiol. 22:315–325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fetherston JD, Bertolino VJ, Perry RD. 1999. YbtP and YbtQ: two ABC transporters required for iron uptake in Yersinia pestis. Mol. Microbiol. 32:289–299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Fetherston JD, Kirillina O, Bobrov AG, Paulley JT, Perry RD. 2010. The yersiniabactin transport system is critical for the pathogenesis of bubonic and pneumonic plague. Infect. Immun. 78:2045–2052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Fetherston JD, Lillard JW, Jr, Perry RD. 1995. Analysis of the pesticin receptor from Yersinia pestis: role in iron-deficient growth and possible regulation by its siderophore. J. Bacteriol. 177:1824–1833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Fetherston JD, Schuetze P, Perry RD. 1992. Loss of the pigmentation phenotype in Yersinia pestis is due to the spontaneous deletion of 102 kb of chromosomal DNA which is flanked by a repetitive element. Mol. Microbiol. 6:2693–2704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Fields KA, Nilles ML, Cowan C, Straley SC. 1999. Virulence role of V antigen of Yersinia pestis at the bacterial surface. Infect. Immun. 67:5395–5408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Fisher CR, et al. 2009. Genetics and virulence association of the Shigella flexneri Sit iron transport system. Infect. Immun. 77:1992–1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Forman S, Paulley JT, Fetherston JD, Cheng Y-Q, Perry RD. 2010. Yersinia ironomics: comparison of iron transporters among Yersinia pestis biotypes and its nearest neighbor, Yersinia pseudotuberculosis. Biometals 23:275–294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Forman S, et al. 2008. yadBC of Yersinia pestis, a new virulence determinant for bubonic plague. Infect. Immun. 76:578–587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Gao H, et al. 2008. The iron-responsive Fur regulon in Yersinia pestis. J. Bacteriol. 190:3063–3075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gong S, Bearden SW, Geoffroy VA, Fetherston JD, Perry RD. 2001. Characterization of the Yersinia pestis Yfu ABC iron transport system. Infect. Immun. 67:2829–2837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Grabenstein JP, Fukuto HS, Palmer LE, Bliska JB. 2006. Characterization of phagosome trafficking and identification of PhoP-regulated genes important for survival of Yersinia pestis in macrophages. Infect. Immun. 74:3727–3741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Guo J, Nair MKM, Galván EM, Liu S-L, Schifferli DM. 2011. Tn5AraOut mutagenesis for the identification of Yersinia pestis genes involved in resistance towards cationic antimicrobial peptides. Microb. Pathog. 51:121–132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Guzman LM, Belin D, Carson MJ, Beckwith J. 1995. Tight regulation, modulation, and high-level expression by vectors containing the arabinose PBAD promoter. J. Bacteriol. 177:4121–4130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hantke K. 1987. Ferrous iron transport mutants in Escherichia coli K12. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 44:53–57 [Google Scholar]

- 41. Higuchi K, Smith JL. 1961. Studies on the nutrition and physiology of Pasteurella pestis. VI. A differential plating medium for the estimation of the mutation rate to avirulence. J. Bacteriol. 81:605–608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Holmes K, et al. 2005. Campylobacter jejuni gene expression in response to iron limitation and the role of Fur. Microbiology 151:243–257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Janakiraman A, Slauch JM. 2000. The putative iron transport system SitABCD encoded on SPI1 is required for full virulence of Salmonella typhimurium. Mol. Microbiol. 35:1146–1155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Janvier B, et al. 1998. Characterization and gene sequencing of a 19-kDa periplasmic protein of Campylobacter jejuni/coli. Res. Microbiol. 149:95–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Jeon J, et al. 2008. RstA-promoted expression of the ferrous iron transporter FeoB under iron-replete conditions enhances Fur activity in Salmonella enterica. J. Bacteriol. 190:7326–7334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kammler M, Schön C, Hantke K. 1993. Characterization of the ferrous iron uptake system of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 175:6212–6219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kaniga K, Delor I, Cornelis GR. 1991. A wide-host-range suicide vector for improving reverse genetics in Gram-negative bacteria: inactivation of the blaA gene of Yersinia enterocolitica. Gene 109:137–141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kehres DG, Janakiraman A, Slauch JM, Maguire ME. 2002. SitABCD is the alkaline Mn2+ transporter of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 184:3159–3166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kirillina O, Bobrov AG, Fetherston JD, Perry RD. 2006. A hierarchy of iron uptake systems: Yfu and Yiu are functional in Yersinia pestis. Infect. Immun. 74:6171–6178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Koch D, et al. 2011. Characterization of a dipartite iron uptake system from uropathogenic Escherichia coli strain F11. J. Biol. Chem. 286:25317–25330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Lamont I, Konings A, Reid D. 2009. Iron acquisition by Pseudomonas aeruginosa in the lungs of patients with cystic fibrosis. Biometals 22:53–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Lathem WW, Price PA, Miller VL, Goldman WE. 2007. A plasminogen-activating protease specifically controls the development of primary pneumonic plague. Science 315:509–513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Lesic B, Carniel E. 2004. The high pathogenicity island: a broad-host-range pathogenicity island, p 285–306 In Carniel E, Hinnebusch BJ. (ed), Yersinia: molecular and cellular biology. Horizon Bioscience, Norfolk, United Kingdom [Google Scholar]

- 54. Lukaszewski RA, et al. 2005. Pathogenesis of Yersinia pestis infection in BALB/c mice: effects on host macrophages and neutrophils. Infect. Immun. 73:7142–7150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Marchler-Bauer A, et al. 2011. CDD: a Conserved Domain Database for the functional annotation of proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 39:D225–D229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Miller JH. 1992. A short course in bacterial genetics. A laboratory manual and handbook for Escherichia coli and related bacteria. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- 57. Naikare H, Palyada K, Panciera R, Marlow D, Stintzi A. 2006. Major role for FeoB in Campylobacter jejuni ferrous iron acquisition, gut colonization, and intracellular survival. Infect. Immun. 74:5433–5444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Paik S, Brown A, Munro CL, Cornelissen CN, Kitten T. 2003. The sloABCR operon of Streptococcus mutans encodes an Mn and Fe transport system required for endocarditis virulence and its Mn-dependent repressor. J. Bacteriol. 185:5967–5975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Palyada K, Threadgill D, Stintzi A. 2004. Iron acquisition and regulation in Campylobacter jejuni. J. Bacteriol. 186:4714–4729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Parkhill J, et al. 2001. Genome sequence of Yersinia pestis, the causative agent of plague. Nature 413:523–527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Perry RD, et al. 2003. Regulation of the Yersinia pestis Yfe and Ybt iron transport systems. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 529:275–283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Perry RD, Balbo PB, Jones HA, Fetherston JD, DeMoll E. 1999. Yersiniabactin from Yersinia pestis: biochemical characterization of the siderophore and its role in iron transport and regulation. Microbiology 145:1181–1190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Perry RD, et al. 2012. Yersinia pestis transition metal divalent cation transporters. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 954:267–279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Perry RD, et al. 2004. Temperature regulation of the hemin storage (Hms+) phenotype of Yersinia pestis is posttranscriptional. J. Bacteriol. 186:1638–1647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Perry RD, Fetherston JD. 2004. Iron and heme uptake systems, p 257–283 In Carniel E, Hinnebusch BJ. (ed), Yersinia: molecular and cellular biology. Horizon Bioscience, Norfolk, United Kingdom [Google Scholar]

- 66. Perry RD, Mier I, Jr, Fetherston JD. 2007. Roles of the Yfe and Feo transporters of Yersinia pestis in iron uptake and intracellular growth. Biometals 20:699–703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Perry RD, Shah J, Bearden SW, Thompson JM, Fetherston JD. 2003. Yersinia pestis TonB: role in iron, heme, and hemoprotein utilization. Infect. Immun. 71:4159–4162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Price PA, Jin J, Goldman WE. 2012. Pulmonary infection by Yersinia pestis rapidly establishes a permissive environment for microbial proliferation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 109:3083–3088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Pujol C, Bliska JB. 2005. Turning Yersinia pathogenesis outside in: subversion of macrophage function by intracellular yersiniae. Clin. Immunol. 114:216–226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Reed LJ, Muench H. 1938. A simple method for estimating fifty percent endpoints. Am. J. Hyg. 27:493–497 [Google Scholar]

- 71. Robey M, Cianciotto NP. 2002. Legionella pneumophila feoAB promotes ferrous iron uptake and intracellular infection. Infect. Immun. 70:5659–5669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Runyen-Janecky LJ, Payne SM. 2002. Identification of chromosomal Shigella flexneri genes induced by the eukaryotic intracellular environment. Infect. Immun. 70:4379–4388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Runyen-Janecky LJ, Reeves SA, Gonzales EG, Payne SM. 2003. Contribution of the Shigella flexneri Sit, Iuc, and Feo iron acquisition systems to iron acquisition in vitro and in cultured cells. Infect. Immun. 71:1919–1928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Sabri M, et al. 2008. Contribution of the SitABCD, MntH, and FeoB metal transporters to the virulence of avian pathogenic Escherichia coli O78 strain χ7122. Infect. Immun. 76:601–611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Sikkema DJ, Brubaker RR. 1987. Resistance to pesticin, storage of iron, and invasion of HeLa cells by yersiniae. Infect. Immun. 55:572–578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Staggs TM, Perry RD. 1991. Identification and cloning of a fur regulatory gene in Yersinia pestis. J. Bacteriol. 173:417–425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Stojiljkovic I, Cobeljic M, Hantke K. 1993. Escherichia coli K-12 ferrous iron uptake mutants are impaired in their ability to colonize the mouse intestine. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 108:111–116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Storz G, Zheng M. 2000. Oxidative stress, p 47–59 In Storz G, Hengge-Aronis R. (ed), Bacterial stress responses. ASM Press, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 79. Straley SC, Harmon PA. 1984. Yersinia pestis grows within phagolysosomes in mouse peritoneal macrophages. Infect. Immun. 45:655–659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Su YC, et al. 2010. Structure of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia FeoA complexed with zinc: a unique prokaryotic SH3-domain protein that possibly acts as a bacterial ferrous iron-transport activating factor. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. F Struct. Biol. Cryst. Commun. 66:636–642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Surgalla MJ, Beesley ED. 1969. Congo red-agar plating medium for detecting pigmentation in Pasteurella pestis. Appl. Microbiol. 18:834–837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Suzuki T, Okamura Y, Calugay RJ, Takeyama H, Matsunaga T. 2006. Global gene expression analysis of iron-inducible genes in Magnetospirillum magneticum AMB-1. J. Bacteriol. 188:2275–2279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Thompson JM, Jones HA, Perry RD. 1999. Molecular characterization of the hemin uptake locus (hmu) from Yersinia pestis and analysis of hmu mutants for hemin and hemoprotein utilization. Infect. Immun. 67:3879–3892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Tsolis RM, Bäumler AJ, Heffron F, Stojiljkovic I. 1996. Contribution of TonB- and Feo-mediated iron uptake to growth of Salmonella typhimurium in the mouse. Infect. Immun. 64:4549–4556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Une T, Brubaker RR. 1984. In vivo comparison of avirulent Vwa− and Pgm− or Pstr phenotypes of yersiniae. Infect. Immun. 43:895–900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. van Vliet AHM, Wooldridge KG, Ketley JM. 1998. Iron-responsive gene regulation in a Campylobacter jejuni fur mutant. J. Bacteriol. 180:5291–5298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Velayudhan J, et al. 2000. Iron acquisition and virulence in Helicobacter pylori: a major role for FeoB, a high-affinity ferrous iron transporter. Mol. Microbiol. 37:274–286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Wang RF, Kushner SR. 1991. Construction of versatile low-copy-number vectors for cloning, sequencing and gene expression in Escherichia coli. Gene 100:195–199 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Wyckoff EE, Mey AR, Leimbach A, Fisher CF, Payne SM. 2006. Characterization of ferric and ferrous iron transport systems in Vibrio cholerae. J. Bacteriol. 188:6515–6523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Zaharik ML, et al. 2004. The Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium divalent cation transport systems MntH and SitABCD are essential for virulence in an Nramp1G169 murine typhoid model. Infect. Immun. 72:5522–5525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Zhou D, Hardt W-D, Galán JE. 1999. Salmonella typhimurium encodes a putative iron transport system within the centisome 63 pathogenicity island. Infect. Immun. 67:1974–1981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.