Abstract

Type IV pili (T4P) are polar surface structures that play important roles in bacterial motility, biofilm formation, and pathogenicity. The protein FimX and its orthologs are known to mediate T4P formation in the human pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa and some other bacterial species. It was reported recently that FimXXAC2398 from Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. citri interacts with PilZXAC1133 directly through the nonenzymatic EAL domain of FimXXAC2398. Here we present experimental data to reveal that the strong interaction between FimXXAC2398 and PilZXAC1133 is not conserved in P. aeruginosa and likely other Pseudomonas species. In vitro and in vivo binding experiments showed that the interaction between FimX and PilZ in P. aeruginosa is below the measurable limit. Surface plasmon resonance assays further confirmed that the interaction between the P. aeruginosa proteins is at least more than 3 orders of magnitude weaker than that between the X. axonopodis pv. citri pair. The N-terminal lobe region of FimXXAC2398 was identified as the binding surface for PilZXAC1133 by amide hydrogen-deuterium exchange and site-directed mutagenesis studies. Lack of several key residues in the N-terminal lobe region of the EAL domain of FimX is likely to account for the greatly reduced binding affinity between FimX and PilZ in P. aeruginosa. All together, the results suggest that the interaction between PilZ and FimX in Xanthomonas species is not conserved in P. aeruginosa due to the evolutionary divergence among the FimX orthologs. The precise roles of FimX and PilZ in bacterial motility and T4P biogenesis are likely to vary among bacterial species.

INTRODUCTION

The dinucleotide cyclic di-GMP (c-di-GMP) is a major bacterial messenger molecule that mediates bacterial motility, biofilm formation, and virulence expression (10, 35). Cellular c-di-GMP signaling networks are usually composed of proteins and riboswitches involved in c-di-GMP synthesis, degradation, and recognition (37). EAL and GGDEF domain-containing proteins are the most prominent c-di-GMP signaling proteins, with the canonical GGDEF and EAL domains functioning as diguanylate cyclases (DGCs) and c-di-GMP-specific phosphodiesterases (PDEs), respectively (36, 38, 41). Recent studies have also uncovered a significant number of nonenzymatic GGDEF and EAL domains (4, 7, 27, 30, 33, 34, 38, 40, 42). Although the functions of many of the nonenzymatic domains remain unknown, some of them act as ligand- or protein-binding domains. In addition to the large number of c-di-GMP signaling proteins in the cell, the presence of nonenzymatic GGDEF and EAL domains further contributes to the complexity of the hierarchical c-di-GMP signaling network.

One of the first proteins known to contain a nonenzymatic EAL domain is FimX, a cytoplasmic protein from the opportunistic pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa (referred to here as FimXPA4959). FimXPA4959 is a multidomain protein required for normal twitching motility and biofilm formation in P. aeruginosa (15, 17) (12). FimXPA4959 contains four protein domains that include a CheY-like domain, a PAS domain, a GGDEF domain, and a C-terminal EAL domain. Studies have shown that the EAL domain of FimXPA4959 binds c-di-GMP with high affinity without degrading the cyclic dinucleotide (15, 26, 34). It was shown that the N-terminal region is necessary and sufficient for polar localization (12, 15) and that the binding of c-di-GMP to the C-terminal EAL domain induces a conformational change in the N-terminal region (29). Farah and coworkers reported that the EAL domain of the FimX ortholog XAC2398 (referred to here as FimXXAC2398) in Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. citri not only binds c-di-GMP but also interacts directly with the PilZ protein XAC1133 (referred to here as PilZXAC1133). PilZXAC1133 is involved in the biogenesis of the polar surface structure type IV pili (T4P), which are essential for twitching motility and biofilm formation (5, 16, 23). Unlike the orthodox PilZ proteins that function as the c-di-GMP binding receptor, PilZXAC1133 belongs to the type II PilZ family and does not exhibit c-di-GMP binding capability (19, 20). It was also suggested by Farah and coworkers that the noncanonical PilZXAC1133 interacts with FimXXAC2398 through a hydrophobic surface (9).

Intriguingly, knockout of the pilZ gene in different bacterial species gives rise to different phenotypic changes. While the knockout of the pilZ gene in P. aeruginosa suppresses twitching motility by hindering the assembly of T4P on the cell surface (1), the knockout of pilZ in Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris only slightly affects T4P-dependent motility (24), and deletion of pilZ in the related Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. citri species enhances sliding motility on semisolid surfaces (9). It was also reported that the knockout of pilZ in Neisseria meningitidis prevents the formation of bacterial aggregates without affecting the biogenesis of T4P (2). These observations seem to indicate that the cellular function of PilZ may have diverged in different bacterial species. Considering the high sequence identity of the PilZ homologs, it is intriguing to speculate whether the divergence is due to the changes in the cellular context of the PilZ proteins (e.g., different protein partners). Following our previous studies on FimXPA4959 and intrigued by the reported interaction between PilZXAC1133 and FimXXAC2398 in Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. citri, we asked whether the FimX-PilZ interaction is also conserved in P. aeruginosa and other bacterial species. In this study, comparative in vitro and in vivo studies were conducted to examine the interaction between the FimX and PilZ homologs in P. aeruginosa and Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. citri. Our data suggest that the interaction between FimX and PilZ in P. aeruginosa is so weak that it is no longer detectable by in vitro and in vivo methods. Identification of a small binding surface in the N-terminal lobe region of the EALXAC2398 domain led to a molecular understanding of the weakened interaction between FimX and PilZ in P. aeruginosa. The results together reveal a structural and functional divergence of the EALFimX domain and underscore the adaptability of c-di-GMP signaling proteins.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

The common chemicals and biological reagents used for protein cloning, expression, and purification were obtained from common commercial sources as specified below.

Preparation of cyclic di-GMP.

c-di-GMP was synthesized enzymatically using a thermophilic diguanylate cyclase (DGC) as described previously (28, 31).

Cloning, expression, and purification of recombinant proteins.

The characteristics of the strains and plasmids used in this study are shown in Table 1. The genes encoding the full-length PilZPA2960 were amplified from the genomic DNA of P. aeruginosa PAO-1 and cloned into the expression vector pET-28b(+) (Novagen) between the NdeI and NotI restriction sites, forming pET-PilZPA2960. Plasmids pET-FimXPA4959 and pET-EALPA4959, which express the full-length FimXPA4959 and EAL domain of FimXPA4959 (referred to as EALPA4959), have been described previously (29). The gene that encodes the EAL domain of FimXXAC2398 was cloned into pET-28a(+) between the NdeI and NotI sites to yield pET-EALXAC2398. PilZXAC1133 was synthesized and optimized for expression in Escherichia coli and cloned into pET-30a(+), forming pET-PilZXAC1133. The plasmids harboring the genes in frame with the His6 tag-encoding sequence were transformed into E. coli strain BL21(DE3).

Table 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant phenotypea | Description (reference) |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| Escherichia coli | ||

| BL21(DE3) | Camr | Cells enabling high-level expression of heterologous proteins in E. coli (Stratagene) |

| BacterioMatch II reporter strain | Kanr | Host strain used for detection of protein-protein interactions in BacterioMatch II 2-hybrid system (Stratagene; catalog no. 200195) |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO-1 | Obtained from ATCC (39) | |

| Plasmids | ||

| pETPA2960 | Kanr | pET-28-based plasmid used for His6-tagged PA2960 protein expression in E. coli |

| pETXAC1133 | Ampr | pET-30-based plasmid used for His6-tagged XAC1133 expression in E. coli |

| pET-EALPA4959 | Kanr | pET-28-based plasmid that encodes the EAL domain (aa 436–691)b of FimX (PA4959) as described previously (29) |

| pET-EALXAC2398 | Kanr | pET-28-based plasmid used for His6-tagged EAL domain (aa 436–698) of XAC2398 expression in E. coli |

| pET-EALXAC2398 (M487E) | Kanr | Plasmid used for expression of M487E mutant protein |

| pET-EALXAC2398 (A493E) | Kanr | Plasmid used for expression of A493E mutant protein |

| pET-EALXAC2398 (M487E L459R) | Kanr | Plasmid used for expression of M487E L459R double mutant protein |

| pET-EALXAC2398 (M487E L459R A493E) | Kanr | Plasmid used for expression of M487E L459R A493E triple mutant protein |

| pBT | Cmr | Bait plasmid used for detection of protein-protein interaction in BacterioMatch II 2-hybrid system (Agilent Technologies; catalog no. 240065) |

| pBTXAC1133 | Cmr | Plasmid constructed by cloning DNA fragment encoding XAC1133 (aa 1–117) into vector pBT |

| pBTPA2960 | Cmr | Plasmid constructed by cloning DNA fragment encoding PA2960 (aa 1–119) into vector pBT |

| pTRG | Tetrr | Prey plasmid used for detection of protein-protein interaction in BacterioMatch II 2-hybrid system |

| pTRG-EALPA4959 | Tetrr | Plasmid constructed by cloning DNA fragment encoding EAL domain (aa 436–691) of FimX (PA4959) into vector pTRG |

| pTRG-EALXAC2398 | Tetrr | Plasmid constructed by cloning DNA fragment encoding EAL domain (aa 436–698) of XAC2398 into vector pTRG |

| pTRG-Gal11P | Tetrr | Positive interaction control plasmid in BacterioMatch II 2-hybrid system, encoding a domain of mutant form of Gal11 protein |

| pBT-LGF2 | Cmr | Positive interaction control plasmid in BacterioMatch II 2-hybrid system, encoding dimerization domain of Gal4 transcriptional activator protein |

Cmr, chloramphenicol resistance; Ampr, ampicillin resistance; Tetrr, tetracycline resistance; Kanr, kanamycin resistance.

aa, amino acids.

For protein expression, 2 ml of culture inoculated with frozen cell stock was added to 1 liter of Luria-Bertani (LB) medium. Bacterial culture was grown at 37°C to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.8 before the induction with 0.5 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) at 16°C for 16 h. The harvested cell pellet was lysed with 40 ml lysis buffer that contains 50 mM NaH2PO4 (pH 7.0), 300 mM NaCl, 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol, and 20 mM imidazole. After centrifugation at 20,000 rpm for 30 min, the supernatant was filtered and then incubated with 2 ml of Ni2+-nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA) resin (Qiagen) for 30 min. After the resin had been washed with 50 ml of wash buffer (lysis buffer supplemented with 50 mM imidazole), protein was eluted with the elution buffer (lysis buffer supplemented with 300 mM imidazole). Fractions with purity higher than 95% were pooled after SDS-PAGE analysis. Size exclusion chromatography was performed at 4°C using the AKTA fast protein liquid chromatography (FPLC) system equipped with a Superdex 200 HR 16/60 column (GE Healthcare). Since c-di-GMP was found to be copurified with FimX, the protein solution of full-length FimX proteins or stand-alone EAL domains was treated with the c-di-GMP-specific phosphodiesterase RocR and Mg2+ to remove c-di-GMP (34). The c-di-GMP-free protein was subsequently separated from RocR by size exclusion chromatography. Purified proteins were flash frozen in liquid N2 and stored at −80°C after the concentration had been measured by the Bradford method.

Site-directed mutagenesis and preparation of mutant proteins.

Site-directed mutagenesis for EALXAC2398 was performed using the pET-28a(+)-based pET-EALXAC2398 plasmid to produce the A493E, M487E, M487E L459R, and M487E L459R A493E mutants via a single-step PCR protocol using the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The following primers were used for the PCR: A493E, 5′-CGGTGAAATGATGAGTCCGAATGAATTCATGGCAATTGCTGAAGAA-3′ and 3′-TTCTTCAGCAATTGCCATGAATTCATTCGGACTCATCATTTCACCG-5′; M487E, 5′-CTGGAACGCAACGGTGAAGAGATGAGTCCGAATGCC-3′ and 3′-GGCATTCGGACTCATCTCTTCACCGTTGCGTTCCAG-5′; and L459R, 5′-GTCGGTGACGGTTTCCGGCTGCATTATCAGCCGG-3′ and 3′-CCGGCTGATAATGCAGCCGGAAACCGTCACCGAC-5′. The mutant proteins were expressed and purified following the same procedure.

Bacterial two-hybrid assay.

The DNA fragment encoding PilZPA2960 was amplified by PCR directly from genomic DNA and by using primers designed based on the Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO-1 genome sequence (39). The following primers were used: forward, CCGGAATTCCATGAGTTTGCCACCCAATC; and reverse, CGCGGATCCTTACATCGTGTGGGTCGG. The amplified DNA fragment was cloned into vector pBT between the EcoRI and BamHI restriction sites to yield plasmid pBT-PilZPA2960.

The gene encoding PilZXAC1133 was amplified from plasmid pETXAC1133 by using the primers 5′-CCGGAATTCCATGAGTGCAATGAAT-3′ and 5′-CGCGGATCCTTACATCGTGTGGGTCG-3′. The amplified DNA fragment was cloned into the vector pBT between the EcoRI and BamHI restriction sites to yield plasmid pBT-PilZXAC1133. The gene encoding the EAL domain of FimXXAC2398 (residues 436 to 689) was amplified from plasmid pET28-EALXAC2398 by using the primers 5′-CGCGGATCCCGTGCGGAAGAAGAACG-3′ and 5′-CCGCTCGAGTCAGCCAAATTCATAG-3′. The amplified DNA fragment was cloned into the vector pTRG between the BamHI and XhoI restriction sites to yield plasmid pTRG-EALXAC2398. The gene encoding the EAL domain of FimXPA4959 (residues 436 to 691) (referred to as EALPA4959) was amplified from genomic DNA of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO-1 by using the primers 5′-CGCGGATCCGCCGCCGCCCAGCGCGGCGAC-3′ and 5′-CCGGAATTCTCATTCGTCTCCCGAGGAGAAG-3′. The amplified DNA fragment was cloned into the vector pTRG between the BamHI and EcoRI restriction sites to yield plasmid pTRG-EALPA4959. Analysis of the interaction between PilZPA2960 and the EAL domain of FimXPA4959 (EALPA4959) was performed following the manufacturer's instructions. In brief, the constructs pBT-PilZPA2960 and pTRG-EALPA4959 were cotransformed into the BacterioMatch II system reporter strain (Stratagene, catalog no. 200195). At the same time, the positive-control plasmid combination, including pBT-LGF2/pTRG-GAL11P and pBT-PilZXAC1133/pTRG-EALXAC2398, and the negative-control plasmid combination shown in the figure legend were also cotransformed into the bacteria the same way. The positive-control plasmids of pTRG-Gal11P and pBT-LGF2 used were from the BacterioMatch II two-hybrid system vector kit (Stratagene, catalog no. 240065). The positive interaction between PilZXAC1133 and EALXAC2398 was confirmed by stripping the cotransformants on the M9+ His-deficient medium containing 5 mM 3-aminotriazole (3-AT), and the mixture was incubated at 37°C overnight. Various growth temperatures and time lengths were tested for the EALPA4959/PilZPA2960 pair to detect weak interaction.

Amide H/D exchange by mass spectrometry.

The experimental setup for hydrogen-deuterium (H/D) exchange was similar to the one described previously (11, 21, 22, 32). Prior to H/D exchange, EALXAC2398 or EALPA4959 was exchanged into 20 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) that contains 100 mM sodium chloride and 2 mM dithiothreitol (DTT). The peptides generated by pepsin digestion at pH 2.5 at 0°C were first identified by a tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) experiment. The H/D exchange reactions were initiated by adding 10 μl of newly thawed protein solution to 90 μl of D2O. After incubation for various lengths of time, the exchange reaction was rapidly quenched by lowering the pH to 2.4 and the temperature to 0°C and followed by pepsin digestion. The generated peptides were passed through a homemade capillary reverse-phase C18 high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) column and eluted into the LTQ-Orbitrap mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific). The peptides were eluted out at a flow rate of 20 μl/min using a stepped gradient (7.5, 10, 12.5, 15, 17.5, 20, 22.5, 25, 30, 40, and 80% acetonitrile in 0.1% formic acid). The time from the initiation of digestion to the elution of the last peptide was approximately 25 min. Xcalibur software (Thermo Scientific) was used for spectrum analysis and data extraction. The H/D exchange data were processed by using the program HX-Express (43). Measured peptide masses were corrected for artifactual in-exchange and back exchange following the methods described by Hoofnagle et al. (11). The time-dependent H/D exchange data were fit by nonlinear least-squares fitting as described previously (21).

ITC.

The equilibrium dissociation constant (KD) for the interaction between FimX and PilZ was measured by using an ITC200 calorimeter (MicroCal). Calorimetric titration of full-length FimX or EALFimX with PilZ protein was performed at 25°C in the assay buffer that contains 10 mM Tris-Cl (pH 8.0)–100 mM NaCl. A time spacing of 240 s was set between injections. The concentration of the EAL protein in the cell is 40 μM, and the final concentration of the PilZ protein reaches 80 or 100 μM. Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) data were analyzed by integrating the heat effects after being normalized to the amount of injected protein. Data fitting was based on a single-site binding model using the embedded software package Microcal to obtain KD.

SPR assay.

Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) measurements were performed on a Biacore 3000 instrument (Biacore, GE Healthcare). All experiments were run with a constant flow rate of 30 μl/min of HBS-EP buffer (10 mM HEPES [pH 7.4], 150 mM NaCl, 3.4 mM EDTA, 0.0005% surfactant P20) at 25°C. Wild-type EAL domain protein and its single, double, and triple mutants were amine coupled onto the surface of a CM5 chip (Biacore, GE Healthcare) through standard amine-coupling chemistry (14). Briefly, a buffer-equilibrated carboxymethyl dextran surface was activated with 7-min injection of a 1:1 mixture of 0.05 M N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) and 0.2 M N-ethyl-N′-[3-(diethylamino)propyl] carbodiimide (EDC). Ligands (the wild-type EAL domain protein and its mutants) acidified in 10 mM sodium acetate buffer (pH 5.0) were passed over the activated surface to achieve the desired response levels separately on different flow cells. A 7-min injection of 1 M ethanolamine-HCl (pH 8.5) was used to deactivate the surface and remove any noncovalently bound protein. Three-fold serially diluted PilZ (0.1 to 24 μM) were injected in duplicates across the chip for 1 min, and dissociation was monitored for 2.5 min. A short pulse (30 s) of 15 mM HCl was passed through the flow system to completely remove any residual bound protein to prepare for the next injection cycle. The raw sensorgrams obtained were aligned, solvent corrected, and double referenced using Scrubber 2 software (BioLogic Software, Campbell, Australia) (25). Processed data were globally analyzed and fit to a simple 1:1 interaction model using numeric integration to yield the individual affinities and kinetic parameters.

Homology modeling.

The structural model for EALXAC2398 was built by using the threading protocol of the Rosetta macromolecular modeling software suite (Rosetta 3.2) (6, 18). The crystal structure of EALFimX (Protein Data Bank [PDB] entry 3HV9 or 3HV8) was used as the template for homology modeling. The 3-mer and 9-mer fragments and the predicted secondary structure for the modeling were generated by the Robetta sever (http://robetta.bakerlab.org/fragmentsubmit.jsp). Alignment of the template and target sequences was performed using ClustalW. The options for the threading protocol are as follows: -in:file:fullatom, -frag3, -frag9, -loops: extended, -loops: build_initial, -loops: remodel quick_ccd, -loops: refine refine_ccd, -random_grow_loops_by 4, -select_best_loop_from 1, -out: nstruct 5000, -out: file: fullatom. The final structural model with lowest energy was obtained by filtering the decoys by ranking and clustering.

RESULTS

Farah and coworkers demonstrated the interaction between PilZXAC1133 and FimXXAC2398 by using a yeast two-hybrid screening method (9). A regulatory mechanism that involves the direct interaction between FimXXAC2398 and PilZXAC1133 for T4P biosynthesis was also suggested. Intrigued by the different phenotypic changes exhibited by the ΔpilZ mutants for different bacterial species, we set out to examine the interaction between FimX and PilZ from P. aeruginosa by conducting the comparative in vivo and in vitro binding assays described below.

Lack of detectable interaction between EALPA4956 and PilZPA2960 revealed by bacterial two-hybrid assay.

After the identification of PilZXAC1133 as the protein partner for FimXXAC2398 by the yeast two-hybrid method, it was further shown that PilZXAC1133 binds to FimXXAC2398 through the EAL domain (9). We confirmed the interaction between the stand-alone EALXAC2398 domain and PilZXAC1133 by using a bacterial two-hybrid system. As shown in Fig. 1, with the pilZ (XAC1133) gene cloned into the bait plasmid and the gene encoding the EAL domain of FimXXAC2398 (residues 436 to 689) (EALXAC2398) cloned into the prey plasmid, colonies were readily observed when the cotransformed E. coli strain was growing on the selective medium. In contrast, no colonies could be detected for the EAL domain of FimXPA4959 (EALPA4959) and PilZPA2960 on the same agar plate. Prolonged growth time and lower growth temperature did not produce colonies either, suggesting that the interaction is still too weak to be detected. The comparative two-hybrid experiments confirmed the strong interaction between EALXAC2398 and PilZXAC1133 and suggested that the interaction between EALPA4959 and PilZPA2960 is below the detection limit of the in vivo two-hybrid assay method.

Fig 1.

Analysis of interaction between PilZ and the EAL domain of FimX homologs using the BacterioMatch II two-hybrid systems (Stratagene). E. coli XL1-Blue MRF′ cells carrying various combinations of pBT (bait)/pTRG (prey) plasmids of bacterial two-hybrid systems were grown on M9+ His-deficient medium (nonselective screening medium) (left panel) or M9+ His-deficient medium containing 5 mM 3-AT (selective screening medium) (right panel). The growth of colonies on selective screening medium indicates a positive interaction between proteins expressed from bait and prey plasmids.

Confirmation of the weak interaction between EALPA4956 and PilZPA2960 by ITC.

To further validate the discrepancy in binding between the two pairs of proteins as revealed by the two-hybrid assays, the four proteins were overexpressed in E. coli and purified as His6-tagged recombinant proteins for in vitro binding affinity measurement by the ITC method. The raw data and isotherm curves obtained under similar experimental conditions are shown in Fig. 2. Protein-protein interaction was readily observed between EALXAC2398 and PilZXAC1133, with a KD of 0.53 μM obtained from the data fitting. The experiment confirmed the interaction between the two proteins, although the reliability of the KD value is compromised because of the gradual precipitation of the EALXAC2398 protein in the course of the titration that resulted in a binding stoichiometry of ∼0.6 (Fig. 2A). In sharp contrast, the titration experiment showed that there is insignificant binding between EALPA4959 and PilZPA2960, with the final concentration of the latter reaching 100 μM at the end of the titration (Fig. 2B). We also tested the full-length FimXPA4959 for the binding assay, and no significant binding was observed either (data not shown). The presence of c-di-GMP (5 or 10 μM) did not seem to enhance or weaken the binding for either pair, indicating that the binding of c-di-GMP does not interfere with PilZ binding. The results are consistent with the observations from the two-hybrid assays and confirm the significant difference in binding between the FimX and PilZ proteins from X. axonopodis pv. citri and P. aeruginosa.

Fig 2.

Measurement of binding affinity by ITC. (A) Isothermal plots for the interaction between PilZXAC1133 and EALXAC2398. (B) Isothermal plots for the interaction between PilZPA2960 and EALPA4959. (Inset) Fitting of the binding isothermal data by the one-site binding model. Experiments were performed in 10 mM Tris-Cl (pH 8.0)–100 mM NaCl by titrating pilZ into EAL protein solutions. The concentration of the EAL protein in the cell is 40 μM, and the final concentration of the PilZ protein reaches 80 to 100 μM.

Characterization of the interaction between EALFimX and PilZ by SPR.

Surface plasma resonance (SPR) is considered to be a more sensitive method for characterization of weak interactions. We used the SPR technique in an effort to measure the binding affinity for the FimX and PilZ pairs and to quantitate the reduction in binding affinity, despite the fact that the interaction for the P. aeruginosa pair is too weak to be detected by the two-hybrid and ITC methods. In addition to the potential stabilizing effect of the surface-immobilizing method on the protein, SPR can also yield information about the kinetics of the association and dissociation steps, allowing a better understanding of the nature of the protein-protein interaction.

We immobilized the two stand-alone EAL domain proteins on the sensor, and the PilZ proteins were passed through the cells. For the X. axonopodis pv. citri pair, a KD of 0.11 μM was obtained from a global fitting of the data (Fig. 3A and Table 2). The kinetic parameters that include the association rate constant (ka) and dissociation rate constant (kd) were also derived from the data (Table 2). The interaction between EALPA4959 and PilZPA2960 was examined under the same conditions. The observed box-shaped sensorgram for the P. aeruginosa pair is typical for weak or transient protein-protein interactions (Fig. 3B), as characterized by the rapid association upon sample injection, the steady equilibrium phase, and the rapid dissociation leading back to buffer baseline. Hence, the square-pulse appearance of the sensorgram indicates that the transient nature of the interaction between the two proteins is governed by the fast association and dissociation steps. Due to the inherent time resolution of the instrument, reliable kinetic rate constants (ka and kd) could not be derived from the data through a simple bimolecular interaction model fit. Given the lower limits of the ITC and SPR methods, we estimate that the KD value for the P. aeruginosa protein pair is above the μM-to-mM range. Note that although both EAL domains bind c-di-GMP with sub-μM affinity, our SPR measurements showed that the binding of c-di-GMP to EALXAC2398 has a rather minor effect on the binding of PilZXAC1133 (KD changes from 0.09 to 0.11 μM) (Table 2) and has no noticeable effect on the P. aeruginosa pair. These observations confirm that the binding of c-di-GMP does not significantly impede or enhance the binding of PilZ.

Fig 3.

Measurement of binding affinity by surface plasmon resonance (SPR). (A) Sensorgrams globally fit to a simple bimolecular interaction model of PilZXAC1133 binding to EALXAC2398. Model lines are shown as the thin gray lines. RU, resonance units. (B) Sensorgrams globally fit to a simple bimolecular interaction model of PilZPA2960 binding to EALPA4959. (C) Sensorgrams globally fit to a simple bimolecular interaction model of PilZPA2960 binding to EALXC2398. (D) Schematic illustration of the cross-binding experiments with the equilibrium dissociation constant (KD) shown for each interaction. Binding measurements were performed in a mixture containing 50 mM HEPES buffer (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 3.4 mM EDTA, and 0.005% surfactant P20 at 25°C with the EAL domain proteins immobilized on the chip.

Table 2.

Thermodynamic and kinetic parameters from SPR measurements

| Protein pair | c-di-GMP (5 μM) | KD (μM) | ka (M−1 s−1) | kd (s−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EALXAC2398-PilZXAC1133 | − | 0.09 | 2.6 × 105 | 2.4 × 10−2 |

| EALXAC2398-PilZXAC1133 | + | 0.11 | 2.4 × 105 | 1.4 × 10−2 |

| EALPA4959-PilZPA2960 | − | NDa | ND | ND |

| EALPA4959-PilZPA2960 | + | ND | ND | ND |

| EALXAC2398-PilZPA2960 | − | 0.06 | 2.4 × 105 | 1.4 × 10−2 |

| EALPA4959-PilZXAC1133 | − | ND | ND | ND |

| EALXAC2398 (M487E)-PilZXAC1133 | − | 0.31 | 8.5 × 104 | 2.6 × 10−2 |

| EALXAC2398 (A493E)-PilZXAC1133 | − | ND | ND | ND |

| EALXAC2398 (M487E L459R)-PilZXAC1133 | − | 0.26 | 1.2 × 105 | 3.1 × 10−2 |

| EALXAC2398 (M487E L459R A493E)-PilZXAC1133 | − | ND | ND | ND |

ND, not determined due to weak binding and fast kinetics.

To investigate whether the weakening in binding between EALPA4959 and PilZPA2960 is due to a divergence in FimX, PilZ, or both proteins, we conducted the cross-binding experiments for the heterologous FimX-PilZ pairs (i.e., EALXAC2398-PilZPA2960 and EALPA4959-PilZXAC1133). While no significant binding was observed between EALPA4959 and PilZPA2960, we observed a strong interaction between EALXAC2398 and PilZPA2960 (Fig. 3C and Table 2). The cross-binding experiment clearly demonstrated the ability of both PilZ proteins to interact with EALXAC2398. This is consistent with the higher extent of sequence identity/homology between the two PilZ proteins: while PilZXAC1133 and PilZPA2960 share 65% sequence identity (82% homology) with the putative binding residues identified by Farah et al. (9) as fully conserved, the two EAL domains only share a low sequence identity of 33% (56% homology), with rather different surface properties.

Identification of the binding surface of EALXAC2398 by H/D exchange.

To understand the molecular basis for the striking contrast in binding between the two pairs of homologous proteins, it is necessary to identify the surface regions and residues involved in protein interaction. While the binding surface for PilZXAC1133 has been suggested to encompass a hydrophobic region in the vicinity of Tyr22 (9), the binding surface of EALXAC2398 has yet to be identified. We employed the highly sensitive amide hydrogen-deuterium (H/D) exchange-coupled mass spectrometry method to map out the binding surface on EALXAC2398. When a protein is incubated in 90% D2O in its native state, the binding of the protein by its ligand or protein partner will result in a suppression of the deuteration level (or rate) for the regions involved in binding (3, 8, 11). Comparison of the deuteration levels for the protein-derived peptides in the presence or absence of the protein partner will disclose the regions involved in protein-protein interaction. In a previous H/D exchange experiment, when H/D exchange was conducted to probe the effect of c-di-GMP binding to FimXPA4959, reduction in deuteration levels of several peptides in the EAL domain and the N-terminal region was readily detected (29).

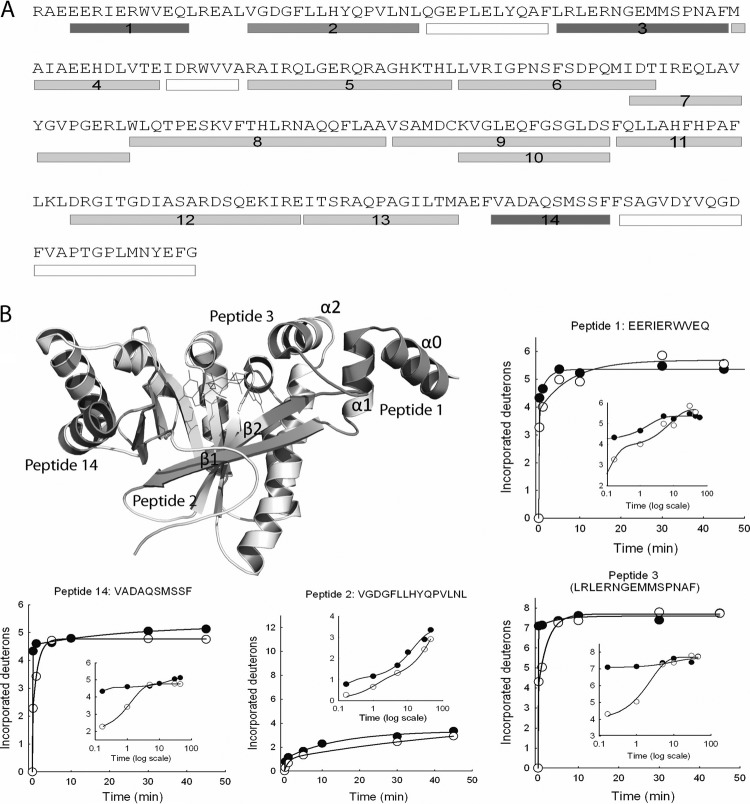

Amide H/D exchange was first performed for the EALXAC2398-PilZXAC1133 pair under the conditions that maintain the stability of the protein in 90% D2O. For EALXAC2398, only 4 out of 14 peptides showed significant changes in deuteration rates or levels when the protein was incubated with PilZXAC1133 in D2O (Fig. 4A). Based on a structural model of EALXAC2398 built by homology modeling, as described in Materials and Methods, the four peptides, which are located on the upper “front face” of the EAL domain, consistently exhibit either a suppressed deuteration level (peptide 2) or a lower exchange rate (peptides 1, 3, and 14). It is clear from the data that peptides 1, 3, and 14 exhibit much slower exchange in the first 10 min in the presence of PilZXAC1133 (Fig. 4B). With the exception of peptide 14, peptides 1, 2, and 3 all contain residues from the N-terminal lobe region. Hence, the lobe region that contains three short helices (α0, α1, and α2) and two loops (α1-β1 and α2-β2) could constitute the main surface for the binding of PilZXAC1133. We speculate that the change in solvent accessibility in peptide 14 could be caused by an allosteric conformational change induced by PilZXAC1133 binding. The H/D exchange experiment was also conducted for the full-length FimXPA4959 as well as the stand-alone EALPA4959 domain in the absence and presence of PilZPA2960. None of the peptides from FimXPA4959 or EALPA4959 showed significant changes in deuteration level or rate when incubated with PilZPA2960 (data not shown), confirming the lack of or at most weak interaction between the P. aeruginosa pair.

Fig 4.

Mapping the binding surface on EALXAC2398 by amide H/D exchange-coupled mass spectrometry. (A) Sequence of EALXAC2398 with the peptides identified for data analysis represented by the underlying bars. The peptides exhibiting deuteration suppression upon PilZXAC1133 binding are represented by the dark gray bars. The peptides exhibiting no changes in deuteration are represented by the light gray bars. The peptides that were not identified are represented by the white bars. (B) EALXAC2398 structural model with the four peptides showing changes in deuteration colored in dark gray. c-di-GMP is modeled in the binding pocket and shown as thin lines. Time-dependent H/D exchange plots for the four peptides are shown along with the log-scaled plots to highlight the early time points (●, without PilZXAC1133; ○, with PilZXAC1133).

Identification of the binding residues in EALXAC2398.

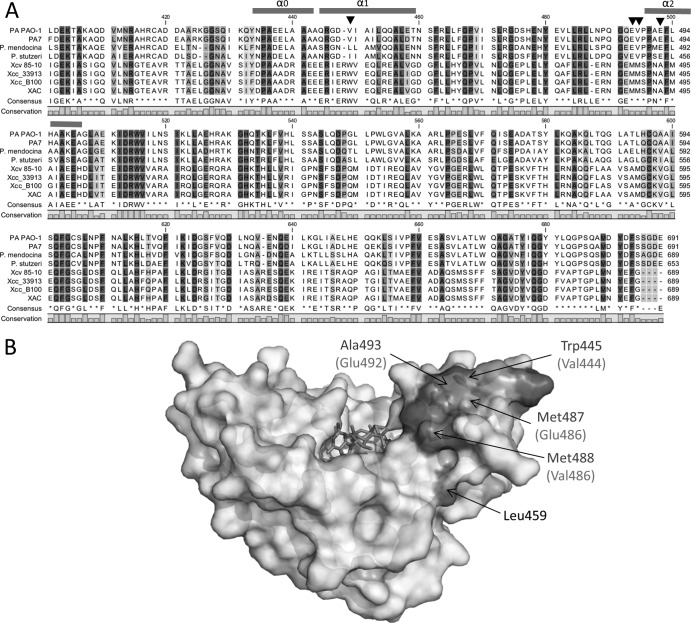

Based on the H/D exchange results, the N-terminal lobe region of EALXAC2398 is likely to be in direct contact with the PilZXAC1133 protein. Considering that the binding surface of PilZXAC1133 is largely nonpolar in nature, the side chains of several conserved nonpolar residues in the lobe region of EALXAC2398 could be the key residues interacting with PilZXAC1133. By sequence alignment, we identified several surface nonpolar residues that are conserved in Xanthomonas species but are replaced by smaller or charged residues in the FimX orthologs from several Pseudomonas species (e.g., Trp445 to Val, Met487 to Glu, Met488 to Val, and Ala493 to Glu) (Fig. 5A and B). To fully establish the roles of these nonpolar residues in the interaction between EALXAC2398 and PilZXAC1133, site-directed mutagenesis was performed to change the residues in EALXAC2398 to the corresponding residues in EALPA4959. Excluding the mutants that are poorly expressed or prone to protein aggregation, we were able to prepare two single mutants (M487E and A493E), one double mutant (M487E L459R), and one triple mutant (M487E L459R A493E) for binding analysis. No noticeable structural perturbation can be detected for the mutants according to size exclusion chromatography and circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy. The residue Leu459 located below the lobe was mutated in the double and triple mutants to test whether the lower front face of the EALXAC2398 domain is also involved in PilZ binding. SPR measurements were performed to examine the effect of the residue replacement on PilZXAC1133 binding. The single mutation M487E causes a 3-fold decrease in binding affinity, and the mutation A493E in EALXAC2398 has the greatest effect on protein-protein interaction by almost completely abolishing the binding, as evidenced by the box-shaped sensorgram (Fig. 6A and B and Table 2). The surface-exposed residue Ala493 is located in a small helix on the top of the lobe region that probably makes direct contact with PilZXAC1133. The replacement of Ala493 by Glu probably impedes the formation of the protein-protein complex by imposing unfavorable steric and electrostatic interactions. The M487E L459R double mutant exhibits similar binding affinity to the M487E single mutant, confirming that the Leu459 residue from the lower front face does not contribute to the binding (Fig. 6C). Similar to the A493E single mutant, the A493E M487E L459R triple mutant exhibits negligible binding affinity for PilZXAC1133, with very weak signals (Fig. 6D). Taken together, the results showed that the replacement of the two nonpolar residues Met487 and Ala493 has a significant effect on the binding between EALXAC2398 and PilZXAC1133, providing strong support for the involvement of the lobe region in the binding of PilZXAC1133.

Fig 5.

Identification of the key binding residues in EALXAC2398. (A) Sequence alignment of the EAL domains from representative Pseudomonas (top four) and Xanthomonas (bottom four) species. PA, P. aeruginosa; Xcv, X. campestris pv. vesicatoria; Xcc, X. campestris pv. campestris; XAC, X. axonopodis pv. citri. The sequence for EALPA4959 is at the top, and the sequence for EALXAC2398 is at the bottom. The positions of the residues that account for the different binding for PilZ are indicated by arrowheads. (B) Surface representation and structural model of EALXAC2398. The residues that are important for PilZXAC1133 binding are highlighted in dark gray and labeled. (In parentheses are the corresponding residues in EALPA4959.) c-di-GMP is modeled in the binding pocket and shown as sticks in the binding pocket.

Fig 6.

SPR measurement of the binding affinity of the EALXAC2398 mutants for PilZXAC1133. (A) Global analysis of PilZXAC1133 binding to the M487E single mutant as fit to a simple bimolecular interaction model. Model lines are shown as the thin gray lines. RU, resonance units. (B) Global analysis of PilZXAC1133 binding to the A493E single mutant. (C) Global analysis of PilZXAC1133 binding to the M487E L459R double mutant as fit to a simple bimolecular interaction model. (D) Global analysis of PilZXAC1133 binding to the M487E L459R A493E triple mutant. (Inset) Circular dichroism (CD) spectra of EALXAC2398 and the triple mutant to show the integrity of the mutant. Experiments were performed in a mixture containing 50 mM HEPES buffer, 150 mM NaCl, 3.4 mM EDTA, and 0.005% surfactant P20 (pH 7.4) at 25°C with the EAL domain proteins immobilized on the chip.

DISCUSSION

One of the hallmarks of the c-di-GMP signaling network is the remarkable functional diversity of c-di-GMP signaling proteins. In addition to the diverse families of c-di-GMP binding receptors, it is now known that the GGDEF and EAL domains can function as enzymatic, ligand-binding, or protein-binding domains. Although EAL domains were initially identified as c-di-GMP-specific phosphodiesterases, a significant number of EAL domains are now known as nonenzymatic domains (26, 27, 32, 34, 42). Among the nonenzymatic EAL domains, some act as c-di-GMP binding domains and some as protein-protein interaction domains. The nonenzymatic EAL domain of FimXXAC2398 harbors binding sites for both c-di-GMP and PilZXAC1133 (9). While the binding mode of c-di-GMP is known from the structural studies on FimXPA4959 (26), how the EALXAC2398 domain interacts with the protein partner PilZXAC1133 remains unknown. The results presented here allow us to identify the N-terminal lobe region of EALXAC2398 as the main surface for PilZXAC1133 binding. The results further indicate that some FimX homologs have gained or lost the binding affinity for PilZ, presumably as a result of the evolutionary divergence of the T4P and the associated c-di-GMP regulatory systems to gain survival advantages.

Binding analysis by the two-hybrid and in vitro methods (ITC and SPR) demonstrated that the interaction between FimXPA4959 and PilZPA2960 is much weaker than that between FimXXAC2398 and PilZXAC1133. In fact, the binding affinity for the P. aeruginosa pair is so low that the interaction is beyond the detection limits of the bacterial two-hybrid and ITC methods. SPR measurement revealed that the weak protein-protein interaction is governed by the rapid association and dissociation processes associated with the binding event. Meanwhile, EALXAC2398 binds PilZPA2960 and PilZXAC1133 with comparable binding affinities (0.06 and 0.09 μM, respectively), strongly suggesting that it is the changes in the EAL domain that result in the reduction in binding affinity. Amide H/D exchange suggested that PilZXAC1133 binds to EALXAC2398 through the N-terminal lobe region. The site-directed mutagenesis experiments confirmed the important roles of the two residues (Ala493 and Met487) from the lobe region in EALXAC2398 for PilZ binding, with a detrimental effect observed for the A493E mutant. Hence, the key binding residues in EALXAC2398 include some of the nonpolar surface residues from the short helices (α0, α1, and α2) and the loop following the β2 strand in the lobe region. The lack of detectable binding between FimXPA4959 and PilZ2960 is due to the changes in the lobe region, especially with the replacement of Trp445, Ala493, Met487, and Met488 by smaller or charged residues.

The different phenotypic changes observed for the ΔpilZ mutants of various bacterial species already implied that the PilZ proteins play different roles in T4P biogenesis and bacterial motility (1, 2, 9, 24). The observations reported here have some further implications regarding the functional roles of FimX and PilZ in T4P biogenesis and regulation. The lack of detectable interaction between FimXPA4959 and PilZPA2960 suggests that the strong interaction between FimXXAC2398 and PilZXAC1133 is not conserved in P. aeruginosa. Comparison of the sequences of FimX homologs also suggests that the key residues for PilZ binding are poorly conserved among Pseudomonas species. Hence, although the interaction between FimX and PilZ could be crucial for the biogenesis and function of T4P in Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. citri (9), the direct interaction between FimX and PilZ may not be required for T4P biogenesis in Pseudomonas species. The nonessential role of FimX (and the FimX-PilZ interaction) in T4P biogenesis is also supported by the observation that the requirement of FimX for type IV pilus formation in P. aeruginosa is bypassed at high cyclic di-GMP concentrations (13). It is also interesting to note that Neisseria meningitidis does not contain a FimX homolog, further confirming that the interaction between FimX and PilZ is not absolutely required for type IV pilus biogenesis or function. Based on these considerations, we propose that FimX does not physically interact with PilZ in Pseudomonas and that the mechanisms by which FimX regulates T4P are different among bacterial species. The variation in binding between FimX and PilZ proteins may reflect the diversity of the T4P systems among bacterial species, while the precise roles of FimX and c-di-GMP in the regulation of T4P remain to be fully disclosed.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work is supported by the Ministry of Education (MOE) of Singapore through a Tier II Academic Research Grant to Z.X.L. This work is supported in part by the Ministry of Education, Taiwan, ROC, under the ATU plan, and by the National Science Council, Taiwan, ROC (grants 97-2113-M005-005-MY3), to S. H. Chou.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 31 August 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Alm RA, Bodero AJ, Free PD, Mattick JS. 1996. Identification of a novel gene, pilZ, essential for type 4 fimbrial biogenesis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 178: 46– 53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Carbonnelle E, Helaine S, Prouvensier L, Nassif X, Pelicic V. 2005. Type IV pilus biogenesis in Neisseria meningitidis: PilW is involved in a step occurring after pilus assembly, essential for fibre stability and function. Mol. Microbiol. 55: 54– 64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ceccarelli C, et al. 2004. Crystal structure and amide H/D exchange of binary complexes of alcohol dehydrogenase from Bacillus stearothermophilus: insight into thermostability and cofactor binding. Biochemistry 43: 5266– 5277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Christen B, et al. 2006. Allosteric control of cyclic di-GMP signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 281: 32015– 32024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Craig L, Pique ME, Tainer JA. 2004. Type IV pilus structure and bacterial pathogenicity. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2: 363– 378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Das R, Baker D. 2008. Macromolecular modeling with Rosetta. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 77: 363– 382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Duerig A, et al. 2009. Second messenger-mediated spatiotemporal control of protein degradation regulates bacterial cell cycle progression. Genes Dev. 23: 93– 104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Englander SW, Sosnick TR, Englander JJ, Mayne L. 1996. Mechanisms and uses of hydrogen exchange. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 6: 18– 23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Guzzo CR, Salinas RK, Andrade MO, Farah CS. 2009. PILZ protein structure and interactions with PILB and the FIMX EAL domain: implications for control of type IV pilus biogenesis. J. Mol. Biol. 393: 848– 866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hengge R. 2009. Principles of c-di-GMP signalling in bacteria. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 7: 263– 273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hoofnagle AN, Resing KA, Ahn NG. 2003. Protein analysis by hydrogen exchange mass spectrometry. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 32: 1– 25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Huang B, Whitchurch CB, Mattick JS. 2003. FimX, a multidomain protein connecting environmental signals to twitching motility in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 185: 7068– 7076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jain R, Behrens A-J, Kaever V, Kazmierczak BI. 2012. Type IV pilus assembly in Pseudomonas aeruginosa over a broad range of cyclic di-GMP concentrations. J. Bacteriol. 194: 4285– 4294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Johnsson B, LöfåS S, Lindquist G. 1991. Immobilization of proteins to a carboxymethyldextran-modified gold surface for biospecific interaction analysis in surface plasmon resonance sensors. Anal. Biochem. 198: 268– 277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kazmierczak BI, Lebron MB, Murray TS. 2006. Analysis of fimX, a phosphodiesterase that governs twitching motility in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol. Microbiol. 60: 1026– 1043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Klausen M, et al. 2003. Biofilm formation by Pseudomonas aeruginosa wild type, flagella and type IV pili mutants. Mol. Microbiol. 48: 1511– 1524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kulasakara H, et al. 2006. Analysis of Pseudomonas aeruginosa diguanylate cyclases and phosphodiesterases reveals a role for bis-(3′-5′)-cyclic-GMP in virulence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103: 2839– 2844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Leaver-Fay A, et al. 2011. Rosetta3: an object-oriented software suite for the simulation and design of macromolecules. Methods Enzymol. 487: 545– 574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Li TN, et al. 2011. A novel tetrameric PilZ domain structure from xanthomonads. PloS One 6: e22036 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0022036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Li TN, Chin KH, Liu JH, Wang AHJ, Chou SH. 2009. XC 1028 from Xanthamanas campestris adopts a PilZ domain-like structure without a c-di-GMP switch. Proteins 75: 282– 288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Liang ZX, Lee T, Resing KA, Ahn NG, Klinman JP. 2004. Thermal-activated protein mobility and its correlation with catalysis in thermophilic alcohol dehydrogenase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101: 9556– 9561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Liang ZX, et al. 2004. Evidence for increased local flexibility in psychrophilic alcohol dehydrogenase relative to its thermophilic homologue. Biochemistry 43: 14676– 14683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mattick JS. 2002. Type IV pili and twitching motility. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 56: 289– 314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. McCarthy Y, et al. 2008. The role of PilZ domain proteins in the virulence of Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris. Mol. Plant Pathol. 9: 819– 824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Myszka DG. 1999. Improving biosensor analysis. J. Mol. Recognit. 12: 279– 284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Navarro MVAS, Bae DNN, Wang Q, Sondermann H. 2009. Structural analysis of the GGDEF-EAL domain-containing c-di-GMP receptor FimX. Structure 17: 1104– 1116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Newell PD, Monds RD, O'Toole GA. 2009. LapD is a bis-(3′,5′)-cyclic dimeric GMP-binding protein that regulates surface attachment by Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf0-1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106: 3461– 3466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pasunooti S, Surya W, Tan SN, Liang Z-X. Sol-gel immobilization of a thermophilic diguanylate cyclase for enzymatic production of cyclic-di-GMP. J. Mol. Catal. B Enzym. 67: 98– 103 [Google Scholar]

- 29. Qi Y, et al. 2011. Binding of c-di-GMP in the non-catalytic EAL domain of FimX induces a long-range conformational change. J. Biol. Chem. 286: 2910– 2917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Qi Y, Rao F, Liang Z-X. 2009. A flavin-binding PAS domain regulates c-di-GMP synthesis in AxDGC2 from Acetobacter xylinum. Biochemistry 48: 10275– 10285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rao F, et al. 2009. Enzymatic synthesis of c-di-GMP using a thermophilic diguanylate cyclase. Anal. Biochem. 389: 138– 142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rao F, et al. 2009. The functional role of a conserved loop in EAL domain-based cyclic di-GMP-specific phosphodiesterase. J. Bacteriol. 191: 4722– 4731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rao F, et al. 2010. YybT is a signaling protein that contains a cyclic dinucleotide phosphodiesterase domain and a GGDEF domain with ATPase activity. J. Biol. Chem. 285: 473– 482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Rao F, Yang Y, Qi Y, Liang ZX. 2008. Catalytic mechanism of c-di-GMP specific phosphodiesterase: a study of the EAL domain-containing RocR from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 190: 3622– 3631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Romling U, Gomelsky M, Galperin MY. 2005. C-di-GMP: the dawning of a novel bacterial signalling system. Mol. Microbiol. 57: 629– 639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ryjenkov DA, Tarutina M, Moskvin OV, Gomelsky M. 2005. Cyclic diguanylate is a ubiquitous signaling molecule in bacteria: insights into biochemistry of the GGDEF protein domain. J. Bacteriol. 187: 1792– 1798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Schirmer T, Jenal U. 2009. Structural and mechanistic determinants of c-di-GMP signalling. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 7: 724– 735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Schmidt AJ, Ryjenkov DA, Gomelsky M. 2005. The ubiquitous protein domain EAL is a cyclic diguanylate-specific phosphodiesterase: enzymatically active and inactive EAL domains. J. Bacteriol. 187: 4774– 4781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Stover CK, et al. 2000. Complete genome sequence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1, an opportunistic pathogen. Nature 406: 959– 964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Suzuki K, Babitzke P, Kushner SR, Romeo T. 2006. Identification of a novel regulatory protein (CsrD) that targets the global regulatory RNAs CsrB and CsrC for degradation by RNase E. Genes Dev. 20: 2605– 2617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Tamayo R, Tischler AD, Camilli A. 2005. The EAL domain protein VieA is a cyclic diguanylate phosphodiesterase. J. Biol. Chem. 280: 33324– 33330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Tschowri N, Busse S, Hengge R. 2009. The BLUF-EAL protein YcgF acts as a direct anti-repressor in a blue-light response of Escherichia coli. Genes Dev. 23: 522– 534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Weis DD, Engen JR, Kass IJ. 2006. Semi-automated data processing of hydrogen exchange mass spectra using HX-Express. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 17: 1700– 1703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]