Abstract

Mobilizable genomic islands (MGIs) are small genomic islands that are mobilizable by SXT/R391 integrating conjugative elements (ICEs) due to similar origins of transfer. Their site-specific integration and excision are catalyzed by the integrase that they encode, but their conjugative transfer entirely depends upon the conjugative machinery of SXT/R391 ICEs. In this study, we report the mechanisms that control the excision and integration processes of MGIs. We found that while the MGI-encoded integrase IntMGI is sufficient to promote MGI integration, efficient excision from the host chromosome requires the combined action of IntMGI and of a novel recombination directionality factor, RdfM. We determined that the genes encoding these proteins are activated by SetCD, the main transcriptional activators of SXT/R391 ICEs. Although they share the same regulators, we found that unlike rdfM, intMGI has a basal level of expression in the absence of SetCD. These findings explain how an MGI can integrate into the chromosome of a new host in the absence of a coresident ICE and shed new light on the cross talk that can occur between mobilizable and mobilizing elements that mobilize them, helping us to understand part of the rules that dictate horizontal transfer mechanisms.

INTRODUCTION

Horizontal gene transfer plays a fundamental role in bacterial evolution (22, 24, 28, 32, 33). By transferring from one bacterial genome to another, mobile genetic elements allow bacteria to acquire new DNA fragments encoding a wide array of new functions (16, 26). Genomic islands (GIs) are mobile genetic elements that play a fundamental role in horizontal gene transfer (26). GIs are DNA segments (10 to 550 kb) that are often associated with tRNA genes and exhibit a G+C content usually different from the surrounding chromosome (16, 26). Based upon the functions that they encode, GIs are also known as pathogenicity, symbiosis, metabolic, resistance, or fitness islands (26).

Integrating conjugative elements (ICEs) are self-transmissible GIs found in many Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria (8, 11, 36–38, 42). ICEs confer a variety of functions on their host, such as virulence factors, establishment of symbiosis, new metabolic traits, resistance to antibiotics, and factors that enhance bacterial fitness (11). ICEs transfer via conjugation in a conjugative plasmid-like manner, and like many temperate bacteriophages, they integrate into their host's chromosome, along with which they are replicated. The well-studied family of SXT/R391 ICEs includes more than 30 members that are found mostly in clinical and environmental Vibrio strains as well as in several other gammaproteobacterial species (7). SXT/R391 ICEs share a conserved set of 52 genes, with nearly half of them encoding proteins necessary for conjugation, integration/excision, and regulation (Fig. 1A) (41). They integrate by site-specific recombination into the 5′ end of prfC, a nonessential gene involved in the termination of translation (25). While integration and excision of SXT/R391 ICEs are catalyzed by the site-specific tyrosine recombinase IntSXT, their excision from the chromosome is facilitated by the recombination directionality factor (RDF) Xis (10). Conjugative transfer of SXT/R391 ICEs is initiated at a cis-acting locus called the origin of transfer (oriTSXT) by the putative relaxase TraI and the auxiliary mobilization protein MobI, which likely form together a nucleoprotein complex called the relaxosome (12). By analogy with conjugative plasmids, translocation of the ICE DNA through the membranes of the donor and the recipient cell is thought to occur as a linear single-stranded DNA molecule covalently bound to TraI (4). Once in the recipient cell, the ICE DNA is recircularized and its complementary strand is synthesized prior to integration into the chromosome. Regulation of excision and transfer of SXT/R391 ICEs is controlled by setR, which encodes a λ CI-like transcriptional repressor that represses the expression of setCD (4, 5). SetCD is a transcriptional activator complex that triggers the expression of all the genes involved in integration, excision, and conjugative transfer. SetR repression of setCD expression is alleviated by DNA damage (5), allowing SetCD to activate excision and transfer of the ICE.

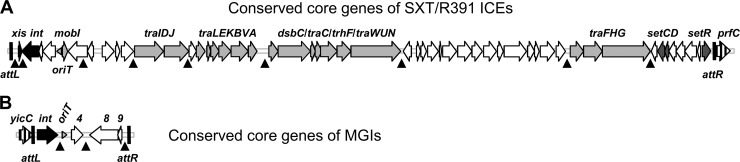

Fig 1.

Schematic representation of the core sets of conserved genes of SXT/R391 ICEs (A) and MGIs (B). Vertically hatched open reading frames indicate the integration sites of the elements (prfC for SXT/R391 ICEs and yicC for MGIs). Black open reading frames represent genes involved in site-specific excision and integration. Light gray open reading frames represent genes encoding the conjugative transfer machinery. Dark gray open reading frames correspond to genes involved in regulation (setCDR), and white open reading frames represent genes of unknown function. oriTs are represented by horizontal gray arrowheads. Hot spots for insertion of variable DNA are indicated by black arrowheads pointing upward.

Besides ICEs and bacteriophages, the vast majority of GIs do not have any known mechanisms of transfer and are therefore considered non-self-transmissible. However, such GIs typically harbor functional or cryptic genes that encode site-specific recombinases (integrases) or transposases. Their mechanisms of transfer likely involve the participation of mobilizing self-transmissible elements, such as generalized transducing phages, conjugative plasmids, or ICEs (6). We have recently identified in several genomes of Vibrio a new family of GIs that rely on a unique mechanism for gene transfer (13). These mobilizable genomic islands (MGIs) have a size of less than 25 kb and can be mobilized at high frequency by SXT/R391 ICEs using a cis-acting oriT sequence that mimics oriTSXT. MGIs integrate into the 3′ end of yicC, a conserved gene encoding a putative stress-induced protein (13). MGI integration is catalyzed by the site-specific recombinase IntMGI, a distant relative of IntSXT. Besides intMGI and the oriTSXT-like oriTMGI sequence, all MGIs identified to date share only three conserved genes (Fig. 1B), none of which are predicted to encode components of a conjugative transfer machinery or an RDF. Interestingly, while MGI excision is independent of intSXT and xis, it requires the presence of the ICE-encoded SetCD transcriptional activators (13).

In this study, we report the identification of the new RDF RdfM, which is required for MGI chromosomal excision. Like intMGI, expression of rdfM is activated by SetCD. Comparison of the regulation of the integration/excision genes of SXT/R391 ICEs and that of those of MGIs revealed that they are similarly regulated by SetCD in the donor cells, yet intMGI is expressed independently of SetCD in the recipient cells, allowing MGIs to integrate into the chromosome of a cell lacking an SXT/R391 ICE. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of such an intimate interaction between two unrelated families of mobile genetic elements.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and media.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are described in Table 1. The strains were routinely grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth at 37°C in an orbital shaker/incubator and were maintained at −80°C in LB broth containing 15% (vol/vol) glycerol. Antibiotics were used at the following concentrations: ampicillin (Ap), 100 μg/ml; kanamycin (Kn), 50 μg/ml; rifampin (Rf), 50 μg/ml; spectinomycin (Sp), 50 μg/ml; sulfamethoxazole (Su), 160 μg/ml; tetracycline (Tc), 12 μg/ml; and trimethoprim (Tm), 32 μg/ml. When required, bacterial cultures were supplemented with 0.3 mM dl-α,ε-diaminopimelic acid (DAP), 100 ng/ml mitomycin C, or 0.02% l-arabinose.

Table 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant genotype or phenotypea | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli strains | ||

| β2163 | (F−) RP4-2-Tc::Mu ΔdapA::(erm-pir) (Knr Emr) | 15 |

| MC4100 λpir | F− araD139 Δ(argF-lac)U169 rpsL150 (Smr) relA1 flbB5301 deoC1 ptsF25 rbsR λpir | 19 |

| CAG18439 | MG1655 lacZU118 lacI42::Tn10 (Tcr) | 39 |

| VB112 | MG1655 Rfr | 12 |

| AD57 | CAG18439 prfC::ICEVflInd1 yicC::MGIVflInd1 (Tcr Sur Tmr) | 13 |

| AD63 | CAG18439 prfC::ICEVflInd1 yicC::MGIVflInd1::aph (Tcr Sur Tmr Knr) | 13 |

| AD72 | CAG18439 prfC::SXT yicC::MGIVflInd1::aph (Tcr Sur Tmr Knr) | 13 |

| AD81 | CAG18439 prfC::ICEVflInd1 yicC::MGIVflInd1 Δint::aad7 (Tcr Sur Tmr Spr) | 13 |

| AD130 | CAG18439 yicC::MGIVflInd1::aph (Tcr Knr) | This study |

| AD132 | CAG18439 yicC::MGIVflInd1::aph pGG2B (Tcr Knr Apr) | This study |

| AD133 | CAG18439 prfC::SXT ΔsetCD yicC::MGIVflInd1::aph (Tcr Sur Tmr Knr) | This study |

| AD167 | CAG18439 prfC::ICEVflInd1 yicC::MGIVflInd1 Δcds9::aph (Tcr Sur Tmr Knr) | This study |

| AD169 | CAG18439 prfC::ICEVflInd1 yicC::MGIVflInd1 Δcds4::aph (Tcr Sur Tmr Knr) | This study |

| AD192 | CAG18439 prfC::ICEVflInd1 yicC::MGIVflInd1 Δcds8::aph (Tcr Sur Tmr Knr) | This study |

| AD207 | CAG18439 prfC::R997 yicC::MGIVflInd1::aph (Tcr Apr Knr) | This study |

| AD208 | CAG18439 pIntVvu (Tcr Apr) | This study |

| AD210 | β2163 pVB200 (Emr Cmr) | This study |

| AD217 | CAG18439 yicC::pVB200 pIntVvu (Tcr Cmr Apr) | This study |

| AD232 | β2163 pSW23T (Emr Cmr) | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pIntVvu | pBAD-TOPO intMGIVvuTai1 (Apr) | 13 |

| pGG2B | pBAD30 setCD (Apr) | G. Garriss |

| pSW23T | oriTRP4; oriVR6Kγ (Cmr) | 15 |

| pVB200 | pSW23T attPMGIVflInd1 (Cmr) | This study |

| p8 | pBAD-TOPO cds9MGIVvuTai1 (Apr) | This study |

| p9 | pBAD-TOPO cds9MGIVvuTai1 (Apr) | This study |

| p9-8 | pBAD-TOPO cds9-8MGIVflInd1 (Apr) | This study |

| pKD13 | PCR template for one-step chromosomal gene inactivation (Knr) | 14 |

Apr, ampicillin resistant; Cmr, chloramphenicol resistant; Knr, kanamycin resistant; Emr, erythromycin resistant; Rfr, rifampin resistant; Smr, streptomycin resistant; Spr, spectinomycin resistant; Sur, sulfamethoxazole resistant; Tcr, tetracycline resistant; Tmr, trimethoprim resistant.

Plasmids and strain constructions.

Plasmids and primers used in this study are described in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. Plasmid pVB200 was constructed by subcloning the XbaI-flanked digestion product attPMGIVflInd1 into the XbaI site of pSW23T. Product attPMGIVflInd1 was amplified using genomic DNA of Vibrio fluvialis H-08942 as a template and primer pair attPAD-L1/attPAD-R1-AC for the first round and primer pair attPAD-L2/attPAD-R2-AC for the second round and then cloned into vector pCR2.1-TOPO (Invitrogen). Plasmids p9, p8, and p9-8 were constructed by cloning cds9MGIVvuTai1, cds8MGIVvuTai1, or cds9-8MGIVflInd1 into the TA cloning expression vector pBAD-TOPO (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. cds9MGIVvuTai1, cds8MGIVvuTai1, and cds9-8MGIVflInd1 were amplified by PCR from genomic DNA of Vibrio vulnificus YJ016 or V. fluvialis H-08942 as a template using primer pairs AD4-V-F/AD4-R1, AD5-F/AD5-V-R1, and AD5-A-R1/AD4-A-F, respectively (Table 2).

Table 2.

DNA sequences of the primers used in this study

| Primer name | Nucleotide sequence (5′ to 3′) | Use in the study |

|---|---|---|

| AD4-V-F | TAGCAGTGAGGAAGCAAACGATG | Amplification of cds9MGIVvuTai1 |

| AD4-R1 | TTATCCACGGCCATAAGCAGC | Amplification of cds9MGIVvuTai1 |

| AD5-F | GCCGTGGATAAACCATCAGCA | Amplification of cds8MGIVvuTai1 |

| AD5-V-R1 | TTAGTCATCCAAAATACTGCCTTT | Amplification of cds8MGIVvuTai1 |

| AD5-A-R1 | TTAGTCATCCAAGATGCTGCCTTT | Amplification of cds9-8MGIVflInd1 |

| AD4-A-F | TAGCCGATTAGTACTGGCAAACTCC | Amplification of cds9-8MGIVflInd1 |

| AD11-WF | CAGCCCACGGCACGCGCACCAATACGAATGGAACGTGTGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCTTCG | Deletion of cds9 in MGIVflInd1 |

| AD11-WR | ATGAACCCAACTACACAATCATCCACCACATCAACAATTCCGGGGATCCGTCGACC | Deletion of cds9 in MGIVflInd1 |

| AD13-WF | AGTGCTAACGATTGGGATAGAGAATGGATACAGCAGGTGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCTTCG | Deletion of cds4 in MGIVflInd1 |

| AD13-WR | CAGCGCCCTGTGAGGGGTTACTCTTTTTTCAGGCCTATTCCGGGGATCCGTCGACC | Deletion of cds4 in MGIVflInd1 |

| attPAD-L1 | TCGGCTTTGCTGTATGCAATA | Amplification of attPMGI, 1st round |

| attPAD-R1-AC | TCTGCCATAGCAACAGCAAT | Amplification of attPMGI, 1st round |

| attPAD-L2 | GAGTTTTCCCATGTTTACTCCATA | Amplification of attPMGI, 2nd round |

| attPAD-R2-AC | GTGACAGCTTTGCCTGCTT | Amplification of attPMGI, 2nd round |

| Gene8-WF | TATGCCTAGCAACATGCCAAAATTACCAGCTGGTTTGTGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCTTCG | Deletion of cds8 in MGIVflInd1 |

| Gene8-WR | TGACTTTGCGCTGTGGTCGGTTGCCATCGGGGATTAATTCCGGGGATCCGTCGACC | Deletion of cds8 in MGIVflInd1 |

| Q-PCR-1F | AAGTGACAAACTCCGCCATC | Amplification of attB in E. coli |

| Q-PCR-1R | GCACGCAAAACAGAATTGAA | Amplification of attB in E. coli |

| Q-PCR-2F | GAAAACGGCAAGCTGAAAAC | Amplification of rph in E. coli |

| Q-PCR-2R | GTCCCCTGCACTTCAATGAT | Amplification of rph in E. coli |

| RTgene9-F b | TTATCCACGGCCATAAGCAG | Amplification of cds9MGIVflInd1 |

| RTgene9-R b | AGGTAAAGGCCAACTCAGGCTT | Amplification of cds9MGIVflInd1 |

| RTintVf-F | CCGTATCGGGTTTACACCAA | Amplification of intMGIVflInd1 |

| RTintVf-R | TTATCGCATGTCGAAACAGC | Amplification of intMGIVflInd1 |

| RTrpoZcoli-F | GCTCGTCAGATGCAGGTAGG | Amplification of rpoZ |

| RTrpoZcoli-R | GCTTGTAATTCAGCGGCTTC | Amplification of rpoZ |

| RTyicC-F | GAGTGACGAAGGGGAAATCA | Amplification of yicC |

| RTyicC-R | GCTTTCAGTGCCTGACCTTC | Amplification of yicC |

All deletion mutants were constructed in Escherichia coli AD57 using the one-step chromosomal gene inactivation technique (14). All mutations were designed to be nonpolar. The Δcds4, Δcds8, and Δcds9 mutations were introduced in MGIVflInd1 using primer pairs AD13-WF/AD13-WR, Gene8-WF/Gene8-WR, and AD11-WF/AD11-WR (Table 2), respectively, and pKD13 as the template. All deletion mutations were verified by PCR amplification using primers flanking the deletion.

Bacterial conjugation.

Conjugation assays were used to transfer SXT, R997, MGIVflInd1, or plasmids into E. coli. Mating assays were performed by mixing equal volumes of overnight cultures of donor and recipient strains. The cells were harvested by centrifugation and resuspended in a 1/20 volume of LB broth. Cell suspensions were poured onto LB agar plates and incubated at 37°C for 6 h. The cells were then resuspended in 1 ml of LB medium, and serial dilutions were plated onto appropriate selective media to determine the number of donors, recipients, and exconjugants. Frequency of transfer was expressed as the number of exconjugant cells per recipient cell in the mating mixture at the time of plating. E. coli CAG18439, MC4100 λpir, or VB112 was used as the recipient in conjugation experiments (Table 1). To induce expression of IntMGI from pIntVvu, SetCD from pGG2B, protein 8 from p8, protein 9 (RdfM) from p9, or proteins 9 and 8 from p9-8 (Table 1) in complementation assays, mating experiments were carried out on LB agar plates supplemented with 0.02% l-arabinose.

Molecular biology techniques.

All the enzymes were used according to the manufacturer's instructions (New England BioLabs). Plasmid DNA was prepared with a QIAprep Spin miniprep kit (Qiagen), and chromosomal DNA was prepared with a Wizard Genomic DNA purification kit (Promega) as described in the manufacturer's instructions.

PCR assays were carried out in 50-μl PCR mixtures with 1 U of Taq DNA polymerase (New England BioLabs). The PCR conditions were as follows: (i) 3 min at 94°C; (ii) 30 cycles of 30 s at 94°C, 30 s at a suitable annealing temperature, and 30 s to 60 s at 72°C; and (iii) 5 min at 72°C. When needed, PCR products were purified using a QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The purified PCR products or inserts of constructed plasmids were sequenced by Centre d'Innovation Génome Québec (McGill University, Montréal, Québec, Canada). DNA sequences were compared with the GenBank DNA sequence database using the BLASTN program (3). E. coli was transformed by electroporation in 1-mm-gap cuvettes according to the method of Dower et al. (18), using a GenePulser Xcell apparatus (Bio-Rad) set at 25 μF, 200 Ω, and 1.8 kV.

Real-time quantitative PCR assays for relative quantification of attB and rph.

Real-time quantitative PCR assays were used to measure the percentages of cells in a culture that contained an unoccupied MGI attB site (the 3′ end of yicC) as described previously (13). Briefly, this corresponds to a comparison of the amounts of excised circularized MGI relative to the amounts of chromosome copies deduced from the amplification of rph, a gene located immediately 5′ of yicC. Primer pairs Q-PCR-1F/Q-PCR-1R and Q-PCR-2F/Q-PCR-2R were used for the amplification of attB and rph, respectively (Table 2).

RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis.

Bacterial cultures were grown at 37°C to early exponential phase (optical density at 600 nm [OD600], 0.2). Cultures were split in two, and induction was initiated by addition of 100 ng/ml mitomycin C or 0.02% l-arabinose. Two hours after induction, aliquots of bacterial cultures were directly mixed with RNA Protect bacterial reagent (Qiagen) and treated according to the manufacturer's instructions. Bacterial RNA was isolated after treating the cells with lysozyme (Sigma), using the RNeasy minikit (Qiagen). In addition, RNA samples were treated with DNase (RNase-free DNase set; Qiagen) during purification and Turbo DNase (Ambion) after purification. RNA purity and concentration were evaluated with an ND-1000 NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific/NanoDrop Products). cDNA was prepared using SuperScript II (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. Fifty nanograms of random hexamers (Integrated DNA Technologies) and 1 μg of total bacterial RNA were used in each reaction. After synthesis, cDNA sample mixtures were purified with the PCR purification kit (Qiagen) and stored at −20°C.

Reverse transcription quantitative PCR.

The MasterCycler EP Realplex 4 sequence detection system (Eppendorf) was used to quantify the increase in fluorescence emission of SYBR green I during PCR. The Realplex software (version 1.5; Eppendorf) was used for data acquisition and analysis. Each 25-μl reaction mixture contained 12.5 μl of 2× SYBR green PCR Master Mix (Qiagen), 1 μM (each) primer, and 1 μl of cDNA template. Primer pairs RTgene9-F b/RTgene9-R b, RTintVf-F/RTintVf-R, RTrpoZcoli-F/RTrpoZcoli-R, and RTyicC-F/RTyicC-R were used for the amplification of cds9MGIVflInd1, intMGIVflInd1, rpoZ, and yicC, respectively (Table 2). The PCR conditions were (i) 5 min at 95°C, (ii) 45 cycles of 10 s at 95°C and 30 s at 60°C, (iii) 15 s at 95°C, (iv) 15 s at 60°C, (v) melting curve from 60°C to 95°C, and (vi) 15 s at 95°C. Three reactions were performed for each sample. For normalization, the rpoZ gene was used and results were expressed as relative expression based on the threshold cycle (ΔΔCT) calculation method. Experiments were carried out three times and combined.

RESULTS

IntMGI is the only MGI-encoded protein necessary for MGI integration.

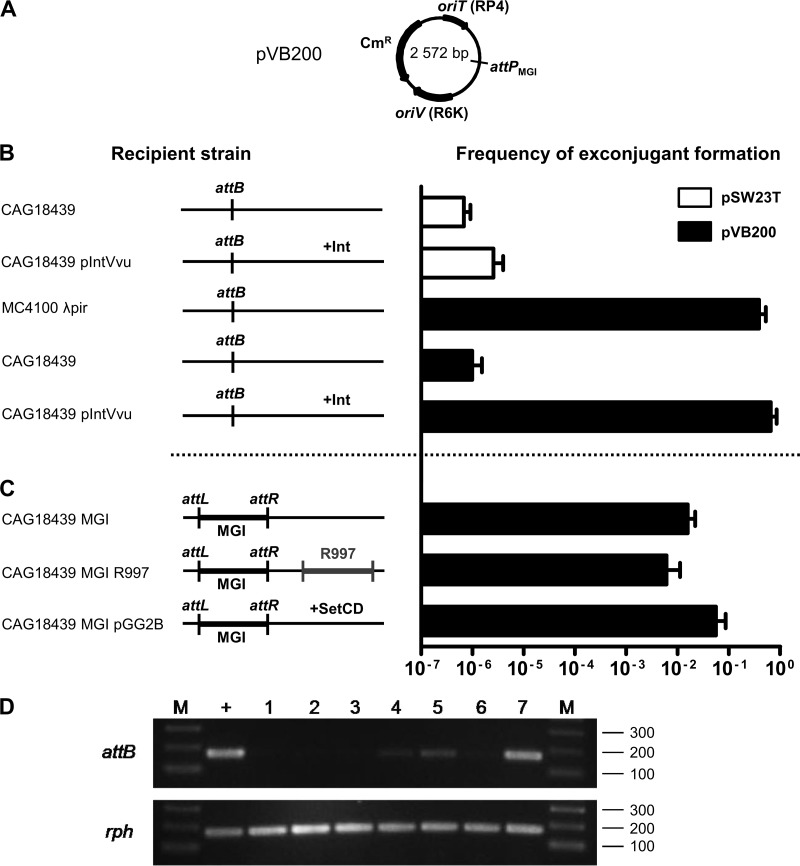

In a previous study, we showed that IntMGI is required for integration and excision of MGIVflInd1 (13). To examine whether IntMGI is the sole MGI-encoded protein necessary to mediate MGI's integration into the 3′ end of yicC, IntMGI-mediated recombination between attPMGI and attB at yicC was monitored using pVB200, a derivative of the mobilizable Cmr suicide vector pSW23T harboring attPMGI (Fig. 2A). Since pSW23T requires the product of pir to replicate, Cmr exconjugants can be isolated after its conjugative transfer from a pir+ host to a pir host only if it has integrated into the chromosome.

Fig 2.

Genetic requirements for integration and excision of a replication-deficient plasmid containing the attP site of MGIVflInd1. (A) Schematic map of pVB200. (B and C) Mobilization assays of pSW23T and pVB200 performed to assess plasmid integration into the 3′ end of yicC (attB). Conjugation assays were carried out using E. coli β2163 (pir+) as a donor and MC4100 λpir (pir+) or CAG18439 variants (pir) as recipient strains. The genetic background of each recipient strain is indicated on the left side of the panels. R997 is an Apr-conferring ICE of the SXT/R391 family. To induce expression of IntMGI from pIntVvu or of SetCD from pGG2B, the conjugation assays were carried out on media supplemented with 0.02% arabinose. The frequency of exconjugant formation was obtained by dividing the number of exconjugants (Tcr Cmr CFU for CAG18439 or Smr Cmr for MC4100 λpir) by the number of recipients (Tcr or Smr CFU, respectively). The bars indicate the mean values and standard deviations obtained from three independent experiments. (D) Analysis of excision of pVB200 integrated into yicC (attB). Ethidium bromide-stained 2% agarose gel of attB and rph fragments amplified by semiquantitative PCR. Lanes: M, 2-log molecular size marker; +, CAG18439; 1 and 2, CAG18439 yicC::pVB200 pIntVvu; 3, CAG18439 yicC::pVB200-MGIVflInd1; 4 and 5, CAG18439 yicC::pVB200-MGIVflInd1 prfC::R997; 6 and 7, CAG18439 yicC::pVB200-MGIVflInd1 pGG2B. Lanes 2 and 7, cultures were induced with 0.02% arabinose; lane 5, culture was induced with 100 ng/ml mitomycin C.

For a negative control, we first mobilized empty pSW23T from a mob+ pir+ donor strain to CAG18439 or CAG18439 harboring pIntVvu (AD208), a plasmid expressing IntMGI under the control of an arabinose-inducible promoter. In both cases, the frequency of exconjugant formation was below 5 × 10−6 exconjugants/recipient, a value that we established as our baseline for subsequent experiments (Fig. 2B). The few recovered exconjugants can be attributed to random integration of the plasmid into the recipient chromosome. For a positive control, we also mobilized pVB200 from the same donor strain to a pir+ strain (MC4100 λpir) to verify that the constructed plasmid remained mobilizable. We found that up to 39% of the pir+ recipient cells acquired and maintained the plasmid. We then mobilized pVB200 from the same donor strain to CAG18439 or AD208 (Fig. 2B). When IntMGI was expressed in the pir recipient strain, the frequency of exconjugant formation was as high as that of the positive control, indicating that the plasmid was able to maintain itself by site-specific integration into the recipient's chromosome. Thus, we conclude that IntMGI is the only MGI-encoded protein needed to mediate efficient integration of MGIs.

MGI integration does not require activation by SetCD.

In our initial study of MGIs, we showed that the SXT/R391 ICE-encoded transcriptional activator SetCD is necessary for MGI excision from the chromosome, suggesting that it is required to activate the expression of IntMGI (13). Surprisingly, we also observed that colonies harboring an MGI but devoid of any ICE were also recovered at high frequency in exconjugant populations. This observation is consistent with the natural occurrence of environmental and clinical isolates (Vibrio cholerae RC385 and V. vulnificus YJ016) having similar configurations (13) and suggests that while SetCD is necessary for excision, it is not required for de novo expression of IntMGI in the recipient cells. To test this hypothesis, we mobilized pVB200 into CAG18439 harboring MGIVflInd1 alone (AD130) or along with either R997 (AD207), an Apr-conferring ICE of the SXT/R391 family, or pGG2B (AD132), a plasmid expressing SetCD under the control of an arabinose-inducible promoter (Fig. 2C). Interestingly, exconjugants formed at high frequency in the sole presence of MGIVflInd1 whereas the presence of R997 or expression of SetCD in the recipient cells did not significantly improve transfer and maintenance of pVB200, supporting the notion that SXT/R391 ICEs and SetCD are necessary for MGI's excision but not its integration.

IntMGI alone does not promote efficient excision of MGIs.

Next, we examined whether IntMGI alone was able to promote efficient excision of pVB200 integrated into yicC. We used a semiquantitative PCR assay to detect unoccupied attB sites in the cell populations compared to rph as a reference target. The formation of an attB site was tested in CAG18439 as a positive control and in CAG18439 harboring attB::pVB200 along with pIntVvu (AD217), MGIVflInd1 (AD130), MGIVflInd1 and R997 (AD207), or MGIVflInd1 and pGG2B (AD132). We found that IntMGI alone did not mediate efficient excision, even when overexpressed (Fig. 2D, lanes 1 to 3). In fact, excision was detectable only in the presence of MGIVflInd1 either along with R997 or upon expression of SetCD from pGG2B (Fig. 2D, lanes 4, 5, and 7). These results led us to suppose that an unidentified MGI-encoded factor likely helps IntMGI to mediate efficient site-specific excision and that expression of this factor is likely activated by SetCD.

MGIs encode a putative RDF.

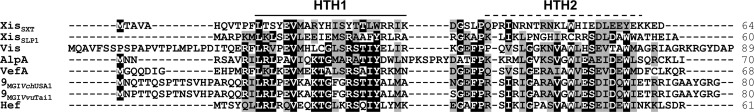

Considering that IntMGI is required but not sufficient to promote efficient excision, we looked at the genes conserved among sequenced MGIs to identify an RDF that could facilitate the IntMGI-mediated excision of MGIs. RDFs control the directionality of tyrosine recombinase-mediated site-specific recombination events (30) and are usually small basic proteins (<100 amino acids) with or without a putative helix-turn-helix (HTH) DNA-binding motif. Besides intMGI, only 3 genes are common to all MGIs identified and sequenced to date: cds4 encodes a 214-amino-acid protein of unknown function, cds8 encodes a 580-amino-acid putative helicase, and cds9 encodes an 80-amino-acid predicted transcriptional regulator (Fig. 1B). Interestingly, the translation product of cds9 shares 36% identity with Hef encoded by the high-pathogenicity island (HPI) of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis and 29% identity with AlpA encoded by E. coli prophage CP4-57 (Fig. 3). Hef has been reported to act as an RDF (29), whereas AlpA has been reported to activate the expression of its cognate integrase gene (27). Given the size of the predicted translation product of cds9 and its similarity with Hef, we considered it to be a good candidate for a putative RDF. Yet, given its similarity with the transcriptional regulator AlpA, we could not rule out at this point the possibility that the product of cds9 could activate the expression of intMGI.

Fig 3.

Sequence alignment of the translation products of cds9MGIVvuTai1 and cds9MGIVchUSA1 with related RDFs. The primary sequences of RDFs encoded by two sequenced MGIs were aligned using MUSCLE with the transcriptional regulator AlpA from CP4-57 prophage (NP_417113) and the RDFs Xis encoded by ICEs of the SXT/R391 family (ACV96240), Hef of HPI from Y. pseudotuberculosis (CAB46594), VefA of VPI-2 from V. cholerae N16961 (NP_231420), SLP1 of plasmid SLP1 from Streptomyces coelicolor, and Vis of the satellite bacteriophage P4 (NP_042041). Amino acid residues that are identical or similar (BLOSUM62 substitution matrix) in at least 60% of the sequences are indicated by a black or gray background, respectively. The solid bar indicates a helix-turn-helix (HTH) DNA-binding motif predicted in all proteins based on the Dodd-Egan method (17) (Dodd-Egan scores of 2.36 or higher), whereas the dashed bar highlights a secondary HTH motif exclusively predicted in RDFs encoded by MGIs (Dodd-Egan score of 3.07). The length of each protein is indicated in the right column.

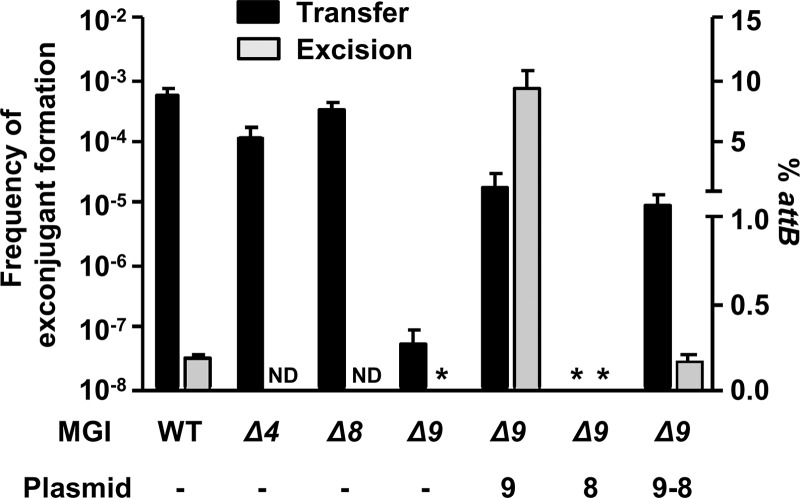

Deletion of cds9 dramatically affects MGI excision and transfer.

To assess whether one of the three MGI conserved genes could act as an RDF, we first constructed deletion mutants of each gene in MGIVflInd1. We tested the ability of each mutant to be mobilized by ICEVflInd1. While deletions of cds4 or cds8 had virtually no impact, deletion of cds9 led to a dramatic reduction of the MGI frequency of transfer (Fig. 4). Mobilization of MGIVflInd1 Δcds9 could be partially restored when cds9 was expressed in trans from an inducible promoter. Complementation with cds8 did not restore MGI transfer, whereas complementation with cds9-cds8 expressed from the same inducible promoter restored mobilization to the same level as that with cds9 alone, ruling out the possible polar effects of the Δcds9 deletion on cds8 that could have explained the partial complementation phenotype observed upon cds9 overexpression.

Fig 4.

Genetic requirements for excision and transfer of MGIVflInd1. Mobilization assays of MGIVflInd1::aph or its Δcds4, Δcds8, or Δcds9 mutants by ICEVflInd1 were carried out using E. coli CAG18439 containing ICEVflInd1 and MGIVflInd1 mutants as donors. When indicated, the donor expressed cds9, cds8, or cds9 and cds8 from p9, p8, or p9-8, respectively. E. coli VB112 (Rfr) was used as the recipient strain. The frequency of exconjugant formation was calculated by dividing the number of exconjugants (Rfr Knr CFU) by the number of donors (Tcr CFU). Real-time quantitative PCR was used to determine the percentage of unoccupied attB sites resulting from the circularization of MGIVflInd1 or of its Δcds9 mutant in E. coli CAG18439 harboring ICEVflInd1, p9, p8, or p9-8. The bars indicate the mean values and standard deviations obtained from three independent experiments. ND, not determined. Asterisks indicate that the frequency of exconjugant formation or the percentage of attB sites was below the limit of detection of the assays (<1 × 10−8 or 0.0004%, respectively).

To investigate whether the reduction of MGIVflInd1 transfer was a consequence of reduced or abolished excision caused by deletion of cds9, we conducted real-time quantitative PCR assays to measure the percentage of cells in a culture containing unoccupied attB sites and found that excision of MGIVflInd1 Δcds9 was undetectable (Fig. 4). In contrast, excision of the same mutant was dramatically enhanced (50-fold over wild-type level) when cds9 was expressed in trans. Interestingly, the rate of excision of the mutant was restored to wild-type level when cds9 and cds8 were expressed together in trans, suggesting a possible regulatory activity of the protein encoded by cds8. These results indicate that the product of cds9 plays an important role in MGI excision, either by acting as an RDF or by activating intMGI expression, or both.

The product of cds9 acts as an RDF, not as a transcriptional activator.

AlpA was shown to activate the expression of the integrase gene of the cryptic prophage CP4-57 in E. coli (27). This ability prompted us to investigate whether the product of cds9 could act as a transcriptional activator of intMGI. Expression of intMGI was measured by reverse transcription real-time quantitative PCR in the presence or absence of mitomycin C and in different genetic backgrounds, including cells devoid of ICE (AD130), cells containing an ICE and a wild-type (AD72) or Δcds9 (AD167) copy of MGIVflInd1, or cells containing both ICEVflInd1 and MGIVflInd1 and expressing cds9 from an inducible promoter (Fig. 5A). We found that intMGI expression was strongly stimulated by the addition of the DNA-damaging agent mitomycin C, but only in the presence of an SXT/R391 ICE. The absence of cds9 had no effect on the mitomycin C-induced activation of intMGI expression. Overexpression of cds9 in the absence of mitomycin C induction led to a slight yet nonsignificant activation of intMGI expression. This barely detectable level of activation is probably not dependent upon cds9 expression, but rather the result of the expression of SetCD in a subpopulation of cells inherently expressing the SOS response, as reported by McCool et al. (31). This phenomenon also explains the constitutive basal level of transfer of SXT/R391 ICE in the absence of DNA-damaging agents. These results combined with our previous observations on SetCD-mediated activation of MGI excision indicate that the product of cds9 acts as an RDF rather than an activator of intMGI expression. From now on, cds9 will therefore be referred to as rdfM for recombination directionality factor of MGI.

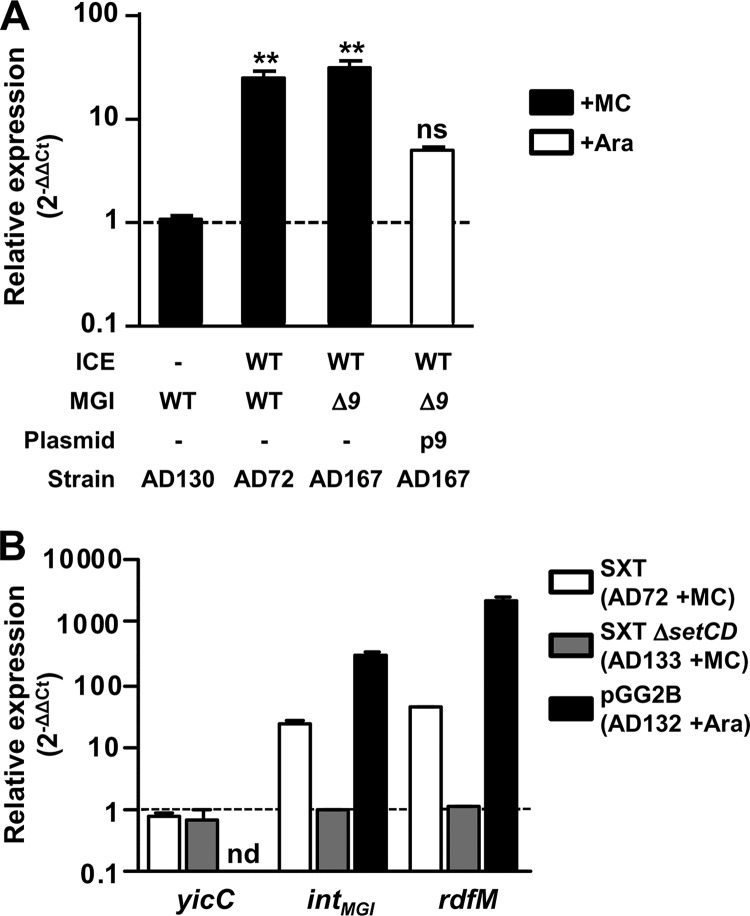

Fig 5.

Regulation of the expression of integration and excision genes of MGIs and SXT/R391 ICEs. (A) Impact of protein 9 on the expression of intMGI. The expression of intMGI was measured by quantitative PCR upon induction of the SOS response (+MC) in AD72, AD130, and AD167 or overexpression of cds9 from p9 in AD167 p9 (+Ara). One-way analysis of variance with a Dunnett posttest was used to compare the means of relative expression of intMGI against the strain devoid of an ICE. The confidence interval for the comparisons was P < 0.01 (**). ns, nonsignificant. (B) Impact of SetCD on intMGI and rdfM expression. The expression of yicC, intMGI, and rdfM was measured upon induction of the SOS response (+MC) in AD72 and AD133 or upon overexpression of setCD from pGG2B (+Ara) in AD132.

Expression of both intMGI and rdfM is activated by SetCD.

Given that SetCD activates MGI excision (13) and that DNA-damaging agents stimulate intMGI expression, we hypothesized that SetCD acts as a transcriptional activator of both intMGI and rdfM. To verify this hypothesis, we measured the expression of intMGI and rdfM in E. coli cells carrying MGIVflInd1 and SXT (AD72) or SXT ΔsetCD (AD133) or expressing SetCD from pGG2B (AD132). We also measured the expression of yicC in the same cells since it is described in GenBank as a gene coding for a putative stress-induced protein and the relative positions and orientations of yicC and intMGI suggest that the two genes may be cotranscribed. Induction was carried out with either mitomycin C (AD72 and AD133) or l-arabinose (AD132). First, we observed that neither SetCD nor mitomycin C modulates the expression of yicC, ruling out the possible expression of intMGI from the promoter of yicC when the MGI is integrated into its 3′ end (Fig. 5B). In contrast, in the presence of wild-type SXT, mitomycin C was found to stimulate the expression of both intMGI and rdfM (24- and 44-fold increase, respectively), whereas it had no effect in the presence of the SXT ΔsetCD mutant. This stimulation of expression is attributable to the increased expression of SetCD from SXT, as the expression of SetCD from pGG2B in a strain lacking SXT resulted in increases of ∼300- and ∼2,000-fold in the transcript levels of intMGI and rdfM, respectively.

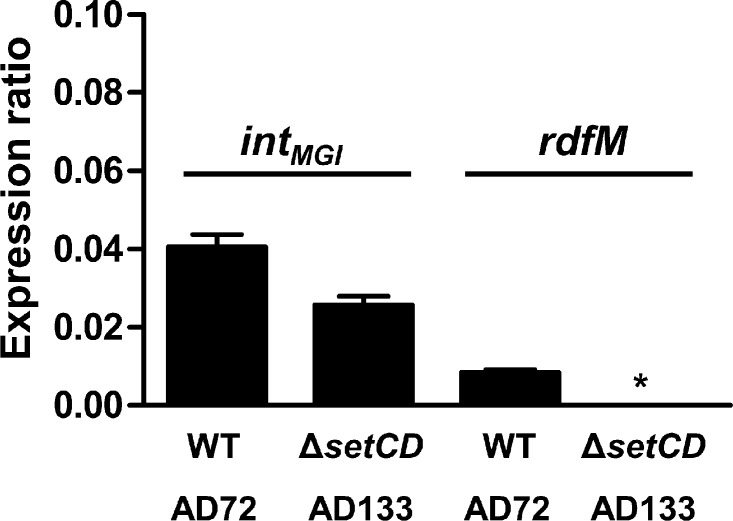

intMGI is constitutively expressed, allowing MGI integration in a strain devoid of an SXT/R391 ICE.

We previously reported that upon mating with an E. coli donor strain harboring MGIVflInd1 and ICEVflInd1, ∼98% of the isolated exconjugant colonies selected for the MGI were devoid of ICEVflInd1, highlighting the independence of MGIs from ICEs for their integration into the chromosome (13). This result is supported by naturally occurring isolates containing MGIs but devoid of SXT/R391 ICEs (13). However, it contrasts with our abovementioned expression results indicating that SetCD activates the expression of intMGI. To explain how MGIs integrate into yicC in the absence of ICE-encoded SetCD, we had a closer look at intMGI expression data under noninduced conditions, which revealed that intMGI has a low-level constitutive expression. In the presence of SXT (AD72), intMGI and rdfM exhibit detectable 2−ΔΔCT values of 0.041 and 0.01 relative to rpoZ, respectively (Fig. 6). This level of expression is most likely a consequence of spontaneous induction of the SOS response (31). When the same experiment was carried out using SXT ΔsetCD (AD133), rdfM expression was below the limit of detection whereas expression of intMGI was reduced by only 36% (Fig. 6). This result, which is also supported by the high rate of exconjugant formation upon mobilization of pVB200 to a strain containing MGIVflInd1 but lacking an ICE (Fig. 2C), indicates that intMGI is constitutively expressed at a low level in the absence of SetCD. This basal level of expression is necessary and sufficient to promote integration of MGIs into the chromosome of a new host in the absence of a helper SXT/R391 ICE.

Fig 6.

intMGI has a basal level of expression in the absence of SetCD. The expression of intMGI was measured by quantitative PCR in AD72 and AD133. The graph shows differential gene expression values (ΔCT) compared with that of the housekeeping gene rpoZ. Results are expressed as the means of three independent biological replicates. The asterisk indicates that expression was below the detection limit. WT, wild type.

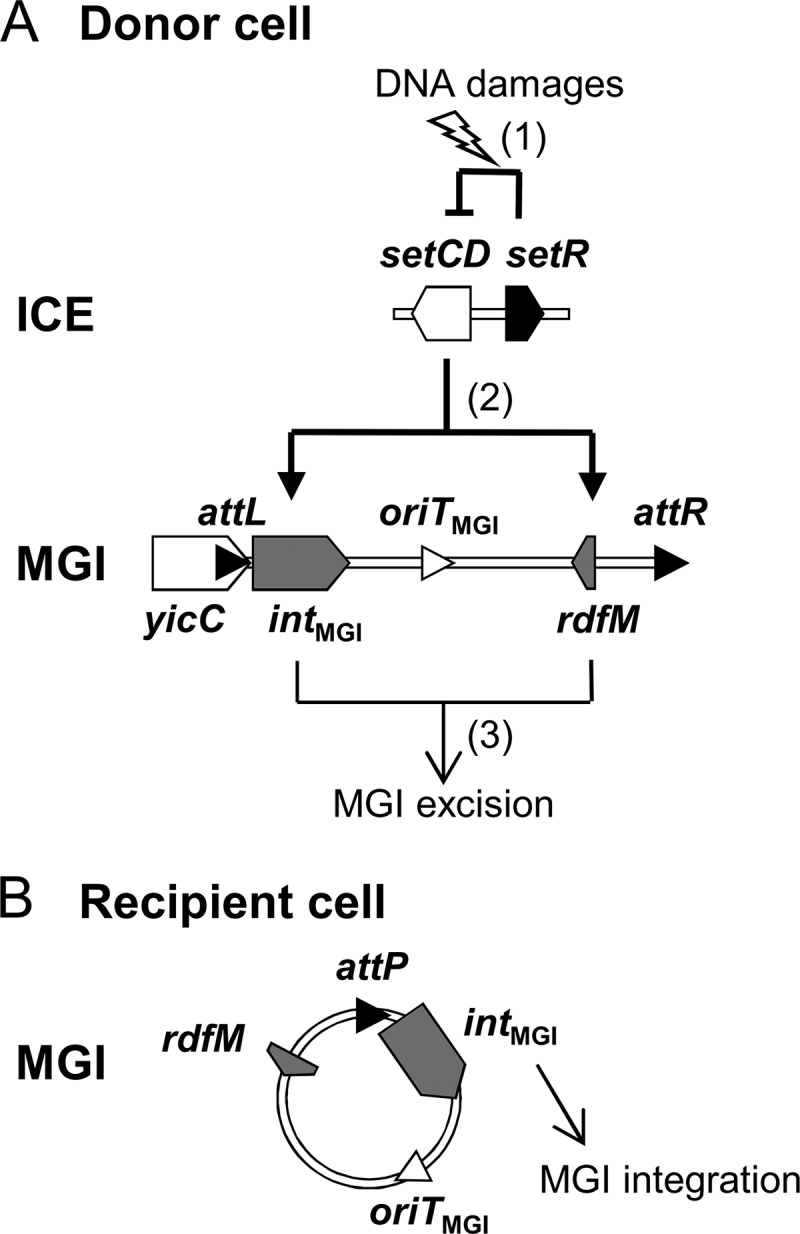

DISCUSSION

In this study, we investigated the integration and excision dynamics of MGIs. We found that while the MGI-encoded integrase alone is sufficient to promote efficient MGI integration into the chromosome, it also requires the MGI-encoded RDF RdfM to promote efficient MGI excision. We found that both intMGI and rdfM are activated by the SXT/R391 ICE-encoded transcriptional regulator SetCD. However, the expression of intMGI does not strictly require SetCD whereas the expression of rdfM does. These findings help to establish how an MGI cannot excise from the chromosome of a cell devoid of an SXT/R391 ICE but can integrate into the chromosome of such a cell. Accordingly, we propose a model of the regulation pathways responsible for the excision and integration processes of MGIs in the donor and recipient cells (Fig. 7).

Fig 7.

Integration and excision dynamics of MGIs in donor and recipient cells. (A) Excision from the donor cell chromosome. (1) SOS response is activated by DNA damages, alleviating the SetR-mediated repression of setCD. (2) The transcriptional activator SetCD activates the expression of intMGI and rdfM. (3) IntMGI and RdfM mediate the excision of the MGI. (B) Integration into the recipient cell chromosome. intMGI is expressed at a low level and allows MGI integration regardless of the presence or absence of an SXT/R391 ICE.

Integration and excision are critical steps in the maintenance and dissemination of an integrative mobile genetic element, whether it is a temperate bacteriophage, an ICE, or a mobile genomic island. Site-specific integration typically requires the action of a single mobile element-encoded site-specific recombinase and may require the help of host-encoded nucleoid proteins, such as the integration host factor (IHF) and the factor for inversion stimulation Fis (reviewed in references 20 and 21). In contrast, the reverse recombination event, the site-specific excision, usually requires an additional genetic element-encoded protein, the RDF, also known as Xis/excisionase, although it usually lacks a catalytic activity per se. RDFs are usually small basic proteins that play architectural roles in the recombination events catalyzed by their cognate tyrosine or serine recombinase. Given their small size, RDF-encoding genes can be difficult to identify, and since a subset of RDFs harbor putative helix-turn-helix domains, they are often annotated as putative transcriptional regulators.

Lewis and Hatfull divided RDFs into 11 subgroups based on sequence similarity (30). We showed here that RdfM belongs to the SLP1 subgroup of RDFs and as such has a putative conserved N-terminal HTH DNA-binding motif (HTH1) (Fig. 3). Peculiarly, unlike other members of this subgroup, RdfM is predicted to contain a second C-terminal HTH DNA-binding motif (HTH2) (Fig. 3), the role of which remains to be determined, as our results indicate that RdfM is not a transcriptional regulator of expression of intMGI. This strongly contrasts with observations reported for AlpA of CP4-57, which activates the expression of slpA, the integrase gene of this cryptic prophage, and for which the role as an actual RDF remains unclear (27). Similarly, in addition to its RDF function, Vis of satellite prophage P4 has been shown to negatively regulate the expression of the P4 integrase by acting as an RNA-binding protein that posttranscriptionally regulates int expression (35). To date, all the RDFs belonging to the SLP1 subgroup have been found associated with P4-type integrases, as is also the case for RdfM (2, 10, 29, 30).

Given their importance for transfer and stability of integrating mobile elements, excision and integration must be tightly regulated. In many temperate bacteriophages and ICEs, the genes coding for the integration and excision functions are organized as a functional module in which the gene encoding the RDF precedes the gene coding for the recombinase, and both genes are organized in an operon-like structure (1, 9, 23, 40). In contrast, the organization of the genes coding for the integration and excision functions of MGIs is atypical: intMGI is located immediately adjacent to attL, and rdfM is located on the opposite side, near the attR site (Fig. 1B). The integrase gene intV2 (VC1758) and the RDF gene vefA (VC1809) of the Vibrio pathogenicity island 2 (VPI-2) are organized in a similar manner (2). This organization also resembles that of the KplE1 prophage, in which the attL site overlaps with the promoter of the intS gene, and the gene coding for the RDF TorI is remotely located, near the attR site (34). Yet while the recombination functions of MGIs and KplE1 seem to be organized alike, they are functionally unrelated. In KplE1, the intS gene is tightly regulated by its own product as well as by the TorI protein (34). In contrast, we showed that in MGIs, rdfM is not a transcriptional regulator of intMGI. In fact, the uncoupled transcription of rdfM and intMGI is likely a feature selected for by the opportunistic behavior of MGIs, as they rely on the SXT/R391 ICE-encoded transcriptional regulator SetCD to excise from their host chromosome. Unlike MGI excision, MGI integration does not require activation by SetCD. Once in a recipient cell, the MGI integrates site specifically through the action of IntMGI expressed at a low level in the absence of SetCD. This process allows an MGI to establish itself in the host cell and be maintained in its progeny even in the absence of an SXT/R391 ICE.

Such a regulatory mechanism might have been selected to prevent MGI loss due to unproductive excision in the absence of a potentially mobilizing ICE of the SXT/R391 family. As a consequence, like for these ICEs, MGI excision and transfer are triggered by any physical or chemical agents that will damage DNA and stimulate the bacterial SOS response, including UV-light irradiation or exposure to mitomycin C and antibiotics such as ciprofloxacin (5, 13). Almagro-Moreno et al. (2) showed that Vibrio pathogenicity island 2 (VPI-2) excises from chromosome I of V. cholerae N16961 after sublethal UV-light irradiation of the cells. Increased excision of VPI-2 was correlated with increased expression of intV2 and vefA. However, since V. cholerae N16961 is devoid of SXT/R391 ICE, induction of VPI-2 excision cannot be controlled by the SetR/SetCD pathway, suggesting that it may instead rely on the SOS response regulon repressor lexA.

This study brings a new understanding of the dynamics of excision, transfer, and integration of mobile genetic elements, giving a better insight into the rules that direct their mobility. We also show a novel interaction between two phylogenetically unrelated families of GIs and show how a small non-self-transmissible GI with no conjugative functions can take advantage of the conjugative machinery and regulatory pathways of a self-transmissible GI in order to transfer from one cell to another.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by a Discovery Grant and Discovery Acceleration Supplement from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Council of Canada (V.B.). D.P.-L. holds a Fonds de Recherche du Québec doctoral fellowship. M.M. was supported by the Deutscher Akademischer Austausch Dienst RISE program. V.B. holds a Canada Research Chair in molecular bacterial genetics and is a member of the FRSQ-funded Centre de Recherche Clinique Étienne-Le Bel.

We are grateful to D. Mazel for kindly providing us with E. coli β2163 and plasmid pSW23T. We thank E. Bordeleau, G. Garriss, N. Carraro, and A. Lavigueur for helpful comments and critical reading of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 24 August 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Abremski K, Gottesman S. 1981. Site-specific recombination Xis-independent excisive recombination of bacteriophage lambda. J. Mol. Biol. 153: 67–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Almagro-Moreno S, Napolitano MG, Boyd EF. 2010. Excision dynamics of Vibrio pathogenicity island-2 from Vibrio cholerae: role of a recombination directionality factor VefA. BMC Microbiol. 10: 306 doi:10.1186/1471-2180-10-306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215: 403–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Beaber JW, Hochhut B, Waldor MK. 2002. Genomic and functional analyses of SXT, an integrating antibiotic resistance gene transfer element derived from Vibrio cholerae. J. Bacteriol. 184: 4259–4269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Beaber JW, Hochhut B, Waldor MK. 2004. SOS response promotes horizontal dissemination of antibiotic resistance genes. Nature 427: 72–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Boyd EF, Almagro-Moreno S, Parent MA. 2009. Genomic islands are dynamic, ancient integrative elements in bacterial evolution. Trends Microbiol. 17: 47–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Burrus V, Marrero J, Waldor MK. 2006. The current ICE age: biology and evolution of SXT-related integrating conjugative elements. Plasmid 55: 173–183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Burrus V, Pavlovic G, Decaris B, Guedon G. 2002. Conjugative transposons: the tip of the iceberg. Mol. Microbiol. 46: 601–610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Burrus V, Pavlovic G, Decaris B, Guedon G. 2002. The ICESt1 element of Streptococcus thermophilus belongs to a large family of integrative and conjugative elements that exchange modules and change their specificity of integration. Plasmid 48: 77–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Burrus V, Waldor MK. 2003. Control of SXT integration and excision. J. Bacteriol. 185: 5045–5054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Burrus V, Waldor MK. 2004. Shaping bacterial genomes with integrative and conjugative elements. Res. Microbiol. 155: 376–386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ceccarelli D, Daccord A, Rene M, Burrus V. 2008. Identification of the origin of transfer (oriT) and a new gene required for mobilization of the SXT/R391 family of integrating conjugative elements. J. Bacteriol. 190: 5328–5338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Daccord A, Ceccarelli D, Burrus V. 2010. Integrating conjugative elements of the SXT/R391 family trigger the excision and drive the mobilization of a new class of Vibrio genomic islands. Mol. Microbiol. 78: 576–588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Datsenko KA, Wanner BL. 2000. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97: 6640–6645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Demarre G, et al. 2005. A new family of mobilizable suicide plasmids based on broad host range R388 plasmid (IncW) and RP4 plasmid (IncPalpha) conjugative machineries and their cognate Escherichia coli host strains. Res. Microbiol. 156: 245–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dobrindt U, Hochhut B, Hentschel U, Hacker J. 2004. Genomic islands in pathogenic and environmental microorganisms. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2: 414–424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dodd IB, Egan JB. 1990. Improved detection of helix-turn-helix DNA-binding motifs in protein sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 18: 5019–5026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dower WJ, Miller JF, Ragsdale CW. 1988. High efficiency transformation of E. coli by high voltage electroporation. Nucleic Acids Res. 16: 6127–6145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dziejman M, Mekalanos JJ. 1994. Analysis of membrane protein interaction: ToxR can dimerize the amino terminus of phage lambda repressor. Mol. Microbiol. 13: 485–494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Finkel SE, Johnson RC. 1992. The Fis protein: it's not just for DNA inversion anymore. Mol. Microbiol. 6: 3257–3265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Friedman DI. 1988. Integration host factor: a protein for all reasons. Cell 55: 545–554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Frost LS, Leplae R, Summers AO, Toussaint A. 2005. Mobile genetic elements: the agents of open source evolution. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3: 722–732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ghinet MG, et al. 2011. Uncovering the prevalence and diversity of integrating conjugative elements in actinobacteria. PLoS One 6: e27846 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0027846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gogarten JP, Townsend JP. 2005. Horizontal gene transfer, genome innovation and evolution. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3: 679–687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hochhut B, Waldor MK. 1999. Site-specific integration of the conjugal Vibrio cholerae SXT element into prfC. Mol. Microbiol. 32: 99–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Juhas M, et al. 2009. Genomic islands: tools of bacterial horizontal gene transfer and evolution. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 33: 376–393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kirby JE, Trempy JE, Gottesman S. 1994. Excision of a P4-like cryptic prophage leads to Alp protease expression in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 176: 2068–2081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lawrence JG, Hendrickson H. 2005. Genome evolution in bacteria: order beneath chaos. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 8: 572–578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lesic B, et al. 2004. Excision of the high-pathogenicity island of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis requires the combined actions of its cognate integrase and Hef, a new recombination directionality factor. Mol. Microbiol. 52: 1337–1348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lewis JA, Hatfull GF. 2001. Control of directionality in integrase-mediated recombination: examination of recombination directionality factors (RDFs) including Xis and Cox proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 29: 2205–2216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. McCool JD, et al. 2004. Measurement of SOS expression in individual Escherichia coli K-12 cells using fluorescence microscopy. Mol. Microbiol. 53: 1343–1357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ochman H, Lawrence JG, Groisman EA. 2000. Lateral gene transfer and the nature of bacterial innovation. Nature 405: 299–304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ochman H, Lerat E, Daubin V. 2005. Examining bacterial species under the specter of gene transfer and exchange. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102(Suppl 1): 6595–6599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Panis G, et al. 2010. Tight regulation of the intS gene of the KplE1 prophage: a new paradigm for integrase gene regulation. PLoS Genet. 6: e1001149 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1001149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Piazzolla D, et al. 2006. Expression of phage P4 integrase is regulated negatively by both Int and Vis. J. Gen. Virol. 87: 2423–2431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Salyers AA, Shoemaker NB, Stevens AM, Li LY. 1995. Conjugative transposons: an unusual and diverse set of integrated gene transfer elements. Microbiol. Rev. 59: 579–590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Scott JR, Churchward GG. 1995. Conjugative transposition. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 49: 367–397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Seth-Smith H, Croucher NJ. 2009. Genome watch: breaking the ICE. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 7: 328–329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Singer M, et al. 1989. A collection of strains containing genetically linked alternating antibiotic resistance elements for genetic mapping of Escherichia coli. Microbiol. Rev. 53: 1–24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Su YA, Clewell DB. 1993. Characterization of the left 4 kb of conjugative transposon Tn916: determinants involved in excision. Plasmid 30: 234–250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wozniak RA, et al. 2009. Comparative ICE genomics: insights into the evolution of the SXT/R391 family of ICEs. PLoS Genet. 5: e1000786 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wozniak RA, Waldor MK. 2010. Integrative and conjugative elements: mosaic mobile genetic elements enabling dynamic lateral gene flow. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 8: 552–563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]