Abstract

In this study, we evaluated a recently developed multilocus variable-number tandem-repeat (VNTR) analysis (MLVA) method for the molecular typing of Mycoplasma pneumoniae. The method is based on GeneScan analysis of five VNTR loci throughout the genome which define a specific genotype based on the number of tandem repeats within each locus. A retrospective analysis of 154 M. pneumoniae clinical isolates collected over the last 50 years and a limited (n = 4) number of M. pneumoniae-positive primary specimens acquired by the CDC was performed using MLVA. Eighteen distinct VNTR types were identified, including two previously unidentified VNTR types. Isolates from several M. pneumoniae community outbreaks within the United States were also analyzed to examine clonality of a specific MLVA type. Observed in vitro variability of the Mpn1 VNTR locus prompted further analysis, which showed multiple insertions or deletions of tandem repeats within this locus for a number of specimens and isolates. To our knowledge, this is the first report showing variation within the Mpn1 locus, thus affecting precise and reliable classification using the current MLVA typing system. The superior discriminatory capability of MLVA provides a powerful tool for greater resolution of M. pneumoniae strains and could be useful during outbreaks and epidemiological investigations.

INTRODUCTION

Mycoplasma pneumoniae is one of the most common bacterial etiologies of community-acquired pneumonia (CAP), representing 15 to 20% of cases in some studies (28). It is also a significant cause of community-wide outbreaks which are reported to occur in 3- to 7-year intervals with various incidence rates (10, 12, 28). Upper and lower respiratory tract symptoms are often mild and self-limiting; however, occasional extrapulmonary complications may develop, sometimes resulting in death (5, 7, 23).

Strain subtyping is an important epidemiological tool for surveillance and outbreak investigations. Until recently, molecular typing of M. pneumoniae had been hindered by its minimal and highly uniform genome. Molecular typing was often restricted to a single gene encoding the P1 protein. Methods such as PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis of the P1 gene (4, 18) and real-time PCR followed by high-resolution melt analysis (HRM) targeting the region of M. pneumoniae repetitive elements 2 and 3 (RepMp2/3) of the P1 gene (19, 20) were used to genotype M. pneumoniae into two subtypes (PCR-RFLP) and variants of subtypes 1 and 2 (PCR-HRM). Both sequencing (9) and pyrosequencing (6, 21, 22) techniques have also been developed to differentiate subtypes of M. pneumoniae. Recently, Degrange et al. (6) developed a multiple-locus variable-number tandem-repeat (VNTR) analysis (MLVA) method for M. pneumoniae based on whole-genome analysis that was able to differentiate 26 distinct VNTR types. This procedure takes advantage of the variation in the copy numbers of tandemly repeated sequences within five different loci within the genome and has proven to be highly discriminatory (6). Ultimately, this technique may allow for improved resolution of M. pneumoniae strains and enhance epidemiological investigations.

In this study, we used the recently developed MLVA typing method to analyze nucleic acid extracts from a collection of M. pneumoniae clinical isolates and a limited number of primary specimens, acquired over the past 50 years, that originated in the United States, Canada, Denmark, Egypt, Kenya, and Guatemala. Isolates from the last three countries were part of the International Emerging Infections Program, a multicountry surveillance network coordinated by the Center for Global Health at the CDC. Additionally, this retrospective analysis allowed us to further examine clinical isolates obtained from eight different M. pneumoniae outbreaks within the United States since 1995 in order to assess potential clonal MLVA types. Lastly, our observations of ostensive in vitro Mpn1 locus instability prompted further evaluation of the suitability of this locus to serve as a reliable marker for MLVA typing.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mycoplasma pneumoniae isolates, culture, and nucleic acid isolation.

Reference strains M129 (ATCC 29342) and FH (ATCC 15531) were tested along with 154 clinical isolates submitted to or isolated at the Respiratory Diseases Branch of the CDC (Table 1). The majority of isolates were collected from nasopharyngeal (NP) and/or oropharyngeal (OP) swab specimens, with the exception of four isolates; three of these four originated from urinary tract specimens (isolates 988, 989, and 990), and one was isolated from synovial fluid (isolate 987). The isolates came from the United States (n = 116), Canada (n = 3), Denmark (n = 10), Egypt (n = 9), Kenya (n = 12), and Guatemala (n = 4) and were collected between 1962 and 2012. Single patient isolates accounted for 150 of 154 isolates. The collection included 145 macrolide-susceptible and 10 macrolide-resistant isolates. All isolations and propagations were performed using SP4 medium (Remel) as previously described (24). Nucleic acid was extracted from liquid culture and from quantitative PCR (qPCR)-positive M. pneumoniae primary specimens using either a QIAmp DNA minikit (Qiagen) or a MagNA Pure Compact Total Nucleic Acid Isolation Kit (Roche Applied Science), according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Table 1.

Characteristics of clinical isolates used in this study

| Isolate | Origin (country and/or state) | Yr of isolation | P1 genotype by PCR-HRM | MLVA type(s) | Modified MLVA nomenclaturej |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 303 | AL, USA | 1991 | 1 | U | 5/4/5/7/2 |

| 519b | CA, USA | 1995 | 2 | M | 4/3/5/6/2 |

| 533b | CA, USA | 1995 | 2 | M | 4/3/5/6/2 |

| 585b | CA, USA | 1995 | 2 | M | 4/3/5/6/2 |

| 987 | CA, USA | 1986 | 2 | O | 4/3/6/6/2 |

| 1801 | DC, USA | 2000 | 2 | O/W | 4–6/3/6/6/2 |

| FL1 | FL, USA | 2012 | 1 | NT | 4–5/4/6/7/2 |

| FL8 | FL, USA | 2012 | 1 | P | 4/4/5/7/2 |

| 1134c | IN, USA | 1999 | 2 | H | 3/3/6/6/2 |

| 1136c | IN, USA | 1999 | 2 | H | 3/3/6/6/2 |

| 1137c | IN, USA | 1999 | 2 | H | 3/3/6/6/2 |

| 1144c | IN, USA | 1999 | 2 | H | 3/3/6/6/2 |

| 1270c | IN, USA | 1999 | 2 | H | 3/3/6/6/2 |

| MA1 | MA, USA | 2011 | 1 | E/J | 2–3/4/5/7/2 |

| O-356d | ME, USA | 2007 | 1 | U | 5/4/5/7/2 |

| 3064d | ME, USA | 2007 | 1 | P/U | 4–5/4/5/7/2 |

| O-360d | ME, USA | 2007 | 1 | U | 5/4/5/7/2 |

| 3058d | ME, USA | 2007 | 1 | U | 5/4/5/7/2 |

| 3076e | NH, USA | 2007 | 2 | G | 3/3/5/6/2 |

| 3088e | NH, USA | 2007 | 2 | G | 3/3/5/6/2 |

| 334 | NJ, USA | 1994 | 2 | O | 4/3/6/6/2 |

| 339 | NJ, USA | 1994 | 2 | O | 4/3/6/6/2 |

| NM1 | NM, USA | 2010 | 1 | P | 4/4/5/7/2 |

| NM2a | NM, USA | 2010 | 1 | P/U | 4–5/4/5/7/2 |

| NM3a | NM, USA | 2010 | 1 | U | 5/4/5/7/2 |

| 297 | NY, USA | 1994 | 2 | W | 6/3/6/6/2 |

| 298 | NY, USA | 1994 | 2 | T | 5/3/6/6/2 |

| 299 | NY, USA | 1994 | 2 | T | 5/3/6/6/2 |

| 300 | NY, USA | 1994 | 2 | T | 5/3/6/6/2 |

| 301 | NY, USA | 1994 | 2 | T | 5/3/6/6/2 |

| 709f | NY, USA | 1996 | 2 | G | 3/3/5/6/2 |

| 752f | NY, USA | 1996 | 2 | G | 3/3/5/6/2 |

| 782f | NY, USA | 1996 | 2 | G | 3/3/5/6/2 |

| 804f | NY, USA | 1996 | 2 | G | 3/3/5/6/2 |

| 806f | NY, USA | 1996 | 2 | M | 4/3/5/6/2 |

| 810f | NY, USA | 1996 | 2 | G | 3/3/5/6/2 |

| 833f | NY, USA | 1996 | 2 | M | 4/3/5/6/2 |

| 834g | NY, USA | 1996 | 2 | M | 4/3/5/6/2 |

| 997g | NY, USA | 1999 | 2 | C | 2/3/6/6/2 |

| 998g | NY, USA | 1999 | 2 | C | 2/3/6/6/2 |

| 999g | NY, USA | 1999 | 2 | C | 2/3/6/6/2 |

| 1000g | NY, USA | 1999 | 2 | C | 2/3/6/6/2 |

| 1001g | NY, USA | 1999 | 2 | C | 2/3/6/6/2 |

| 1002g | NY, USA | 1999 | 2 | C | 2/3/6/6/2 |

| 1003g | NY, USA | 1999 | 2 | C | 2/3/6/6/2 |

| 1004g | NY, USA | 1999 | 2 | C | 2/3/6/6/2 |

| 1005g | NY, USA | 1999 | 2 | C | 2/3/6/6/2 |

| 1006a,g | NY, USA | 1999 | 2 | C | 2/3/6/6/2 |

| 237 | OH, USA | 1993 | 2 | C | 2/3/6/6/2 |

| 250 | OH, USA | 1993 | 2 | H | 3/3/6/6/2 |

| 253 | OH, USA | 1993 | 2 | C | 2/3/6/6/2 |

| OR1a | OR, USA | 2011 | 1 | P | 4/4/5/7/2 |

| OR2a | OR, USA | 2011 | 1 | P/X | 4–6/4/5/7/2 |

| 399 | PA, USA | 1994 | 2 | G | 3/3/5/6/2 |

| 2Pa,h | RI, USA | 2007 | 1 | X | 6/4/5/7/2 |

| 3h | RI, USA | 2007 | 2Vl | T | 5/3/6/6/2 |

| 6a,h | RI, USA | 2007 | 1 | J | 3/4/5/7/2 |

| 10h | RI, USA | 2007 | 1 | J | 3/4/5/7/2 |

| 11a,h | RI, USA | 2007 | 1 | J | 3/4/5/7/2 |

| 13h | RI, USA | 2007 | 1 | U | 5/4/5/7/2 |

| 15h | RI, USA | 2007 | 1 | J | 3/4/5/7/2 |

| 17h | RI, USA | 2007 | 1 | U | 5/4/5/7/2 |

| 18h | RI, USA | 2007 | 1 | P | 4/4/5/7/2 |

| 19h | RI, USA | 2007 | 1 | J | 3/4/5/7/2 |

| 20h | RI, USA | 2007 | 1 | J | 3/4/5/7/2 |

| RI1 | RI, USA | 2011 | 2 | B | 2/3/5/6/2 |

| RI2 | RI, USA | 2011 | 2 | B | 2/3/5/6/2 |

| 983 | SC, USA | 1988 | 2 | T | 5/3/6/6/2 |

| 984 | SC, USA | 1988 | 2 | H | 3/3/6/6/2 |

| 985 | SC, USA | 1988 | 2 | O | 4/3/6/6/2 |

| 386 | TX, USA | 1994 | 2 | B | 2/3/5/6/2 |

| 382 | WA, USA | 1966 | 1 | E/P | 2–4/4/5/7/2 |

| 383 | WA, USA | 1966 | 1 | P | 4/4/5/7/2 |

| 384 | WA, USA | 1965 | 1 | X | 6/4/5/7/2 |

| 385 | WA, USA | 1966 | 1 | J | 3/4/5/7/2 |

| 534 | WA, USA | 1966 | 1 | J | 3/4/5/7/2 |

| 535 | WA, USA | 1966 | 1 | J | 3/4/5/7/2 |

| 536 | WA, USA | 1965 | 1 | P | 4/4/5/7/2 |

| 537 | WA, USA | 1965 | 1 | P | 4/4/5/7/2 |

| 538 | WA, USA | 1965 | 1 | U | 5/4/5/7/2 |

| 539 | WA, USA | 1971 | 1 | P | 4/4/5/7/2 |

| 540 | WA, USA | 1974 | 1 | U | 5/4/5/7/2 |

| 541 | WA, USA | 1974 | 1 | U | 5/4/5/7/2 |

| 542 | WA, USA | 1969 | 1 | U | 5/4/5/7/2 |

| 543 | WA, USA | 1968 | 1 | J | 3/4/5/7/2 |

| 544 | WA, USA | 1974 | 1 | J | 3/4/5/7/2 |

| 545 | WA, USA | 1966 | 1 | J | 3/4/5/7/2 |

| 546 | WA, USA | 1965 | 1 | P | 4/4/5/7/2 |

| 547 | WA, USA | 1967 | 1 | E | 2/4/5/7/2 |

| 548 | WA, USA | 1966 | 1 | E | 2/4/5/7/2 |

| 549 | WA, USA | 1965 | 1V | P | 4/4/5/7/2 |

| 550 | WA, USA | 1965 | 1 | Z | 7/4/5/7/2 |

| 551 | WA, USA | 1974 | 2 | O | 4/3/6/6/2 |

| 552 | WA, USA | 1968 | 1 | P | 4/4/5/7/2 |

| 553 | WA, USA | 1970 | 1 | P | 4/4/5/7/2 |

| 554 | WA, USA | 1966 | 1 | P | 4/4/5/7/2 |

| 555 | WA, USA | 1966 | 1 | J | 3/4/5/7/2 |

| 556 | WA, USA | 1966 | 1 | J | 3/4/5/7/2 |

| 557 | WA, USA | 1965 | 1 | J | 3/4/5/7/2 |

| 558 | WA, USA | 1965 | 1 | Z | 7/4/5/7/2 |

| 559 | WA, USA | 1967 | 1 | P | 4/4/5/7/2 |

| WI3 | WI, USA | 2012 | 1 | E | 2/4/5/7/2 |

| WI4 | WI, USA | 2012 | 1 | Z | 7/4/5/7/2 |

| WI5 | WI, USA | 2012 | 1 | E | 2/4/5/7/2 |

| WI6 | WI, USA | 2012 | 2 | M | 4/3/5/6/2 |

| WI7 | WI, USA | 2012 | 2 | M/V | 4–6/3/5/6/2 |

| WV1i | WV, USA | 2011 | 2 | S | 5/3/5/6/2 |

| WV2i | WV, USA | 2011 | 1 | P | 4/4/5/7/2 |

| WV4i | WV, USA | 2012 | 1 | J | 3/4/5/7/2 |

| WV8i | WV, USA | 2011 | 1 | J/P | 3–4/4/5/7/2 |

| WV9a,i | WV, USA | 2012 | 1 | J | 3/4/5/7/2 |

| WV13i | WV, USA | 2011 | 2 | S | 5/3/5/6/2 |

| WV14i | WV, USA | 2011 | 1 | P | 4/4/5/7/2 |

| WV22i | WV, USA | 2012 | 2 | M | 4/3/5/6/2 |

| 982 | USA | 1962 | 2 | O | 4/3/6/6/2 |

| 674 | USA | 1965 | 2 | O | 4/3/6/6/2 |

| 988 | Ontario, Canada | 1992 | 1 | P | 4/4/5/7/2 |

| 989 | Ontario, Canada | 1992 | 1 | P | 4/4/5/7/2 |

| 990 | Ontario, Canada | 1992 | 1 | P | 4/4/5/7/2 |

| M8 | Denmark | Unknown | 1 | P | 4/4/5/7/2 |

| M1042 | Denmark | Unknown | 1 | Z | 7/4/5/7/2 |

| M1311 | Denmark | Unknown | 1 | U | 5/4/5/7/2 |

| M1397 | Denmark | Unknown | 1 | U | 5/4/5/7/2 |

| M2098 | Denmark | Unknown | 2 | V | 6/3/5/6/2 |

| M4718 | Denmark | Unknown | 1 | X | 6/4/5/7/2 |

| M72 | Denmark | Unknown | 1V | X | 6/4/5/7/2 |

| M2018a | Denmark | 1988 | 1 | P | 4/4/5/7/2 |

| M1885 | Denmark | Unknown | 2 | V | 6/3/5/6/2 |

| M4394 | Denmark | Unknown | 1 | P | 4/4/5/7/2 |

| E1 | Egypt | 2009 | 2 | M | 4/3/5/6/2 |

| E8 | Egypt | 2010 | 2 | S | 5/3/5/6/2 |

| E9 | Egypt | 2010 | 2 | G | 3/3/5/6/2 |

| E16 | Egypt | 2010 | 1 | X | 6/4/5/7/2 |

| E17 | Egypt | 2010 | 2 | G | 3/3/5/6/2 |

| E18 | Egypt | 2010 | 1 | J | 3/4/5/7/2 |

| E25 | Egypt | 2010 | 1 | P | 4/4/5/7/2 |

| E56 | Egypt | 2010 | 2 | G | 3/3/5/6/2 |

| E57 | Egypt | 2010 | 2 | B | 2/3/5/6/2 |

| G6 | Quetzaltenango, Guatemala | 2010 | 1 | P | 4/4/5/7/2 |

| G10 | Cuilapa, Guatemala | 2010 | 1 | NTk | 4/4/6/7/2 |

| G14 | Quetzaltenango, Guatemala | 2010 | 1 | E | 2/4/5/7/2 |

| G15 | Quetzaltenango, Guatemala | 2010 | 1 | J | 3/4/5/7/2 |

| 986 | Kenya | 1998 | 1 | U | 5/4/5/7/2 |

| K3 | Kenya | 2010 | 2 | T | 5/3/6/6/2 |

| K4 | Kenya | 2010 | 2 | C | 2/3/6/6/2 |

| K5 | Kenya | 2010 | 2 | C | 2/3/6/6/2 |

| K6 | Kenya | 2010 | 2 | M | 4/3/5/6/2 |

| K8 | Kenya | 2010 | 2 | M | 4/3/5/6/2 |

| K20 | Kenya | 2010 | 2 | C | 2/3/6/6/2 |

| K21 | Kenya | 2010 | 1 | P | 4/4/5/7/2 |

| K22 | Kenya | 2010 | 1 | P | 4/4/5/7/2 |

| K23 | Kenya | 2010 | 1 | P | 4/4/5/7/2 |

| K27 | Kenya | 2010 | 2 | C | 2/3/6/6/2 |

| K28 | Kenya | 2010 | 1 | P | 4/4/5/7/2 |

Macrolide-resistant isolates (28).

California outbreak, 1995.

Indiana outbreak, 1999.

Maine outbreak, 2007.

New Hampshire outbreak, 2007.

New York outbreak, 1996.

New York outbreak, 1999.

Rhode Island outbreak, 2007.

West Virginia outbreak, 2011 to 2012.

Dumke and Jacobs (8).

NT, untypeable by the scheme proposed by Degrange et al. (6).

V, variant.

P1 and macrolide profile genotyping.

The P1 genotype and macrolide susceptibility profiles for 100 isolates were previously determined (20, 29). The identical method of real-time PCR followed by HRM analysis was performed on the 54 remaining isolates to determine the P1 genotypes and macrolide susceptibility profiles, as previously described (20, 29).

MLVA PCR.

Extracted nucleic acid from all 154 isolates and from four qPCR-positive M. pneumoniae primary NP/OP specimens, which subsequently yielded 4 isolates (MA1, WI7, WV8, and WV9), was used as the template for PCR amplification of the five loci selected for MLVA, as described previously (6). Cycling conditions were adjusted from 25 to 45 cycles when nucleic acid extracts from primary specimens were amplified.

Mpn1 VNTR locus variability analysis.

Reference strain FH (ATCC 15531) obtained in 1996 and 2009 (each isolate propagated and stored using identical conditions within our laboratory) along with 14 clinical isolates was passaged 10 times in SP4 medium. MLVA was performed on nucleic acid extracts from each isolate at every passage.

RESULTS

Typing of clinical isolates.

MLVA typing of 154 clinical isolates collected since 1962 from several countries, including the United States, Canada, Denmark, Egypt, Kenya, and Guatemala, was performed (Table 1). All five VNTR loci were amplified from all 154 isolates with consistent size variations and multiples of the amplicon repeats as previously described by Degrange et al. (6; also data not shown).

Analysis of the combination of tandem repeats of the five loci revealed 16 distinct types (B, C, E, G, H, J, M, O, P, S, T, U, V, W, X, and Z) in the United States, 1 in Canada (P), 5 in Denmark (P, U, V, X, and Z), 7 in Egypt (B, G, J, M, P, S, and X), 5 in Kenya (C, M, P, U, and T), and 3 in Guatemala (E, J, and P). Additionally, two novel MLVA types were identified: MLVA profile 4–5/4/6/7/2 (isolate FL1; United States) and 4/4/6/7/2 (isolate G10; Guatemala). The most common MLVA type across the entire collection of specimens was P (21%), present in each of the six international sites contributing isolates to this study. This observation is consistent with another recent study (6). Two isolates (1005 and 1006), obtained from respiratory specimens collected from a single patient 3 weeks apart during the 1999 New York outbreak, were both MLVA type C (Table 1), but isolate 1006 had acquired macrolide resistance through a single point mutation in the 23S rRNA gene (29). No obvious link between MLVA type and resistance to macrolides was observed as the 10 macrolide-resistant isolates were distributed among five different MLVA types (C, J, P, U, and X).

Clinical isolates from eight different M. pneumoniae community outbreaks within the United States were also successfully typed using MLVA (Table 1). Clonal spread of a particular MLVA type was identified in community outbreaks in California (1995, MLVA type M), Indiana (1999, type H), New York (1999, type C), Maine (2007, type U), and New Hampshire (2007, type G). Two MLVA types (G and M) were present in isolates collected in a New York outbreak in 1996, while five (J, P, T, U, and X) and four (J, M, P, and S) MLVA types were detected in outbreaks in Rhode Island (2007) and West Virginia (2011 to 2012), respectively. No particular pattern or trend was observed with regard to the number of MLVA types present in each outbreak and the year of occurrence. However, the prevalence of clonality of MLVA types appears to be less likely in outbreaks as higher numbers of representative isolates are obtained.

Analysis of Mpn1 VNTR locus variations.

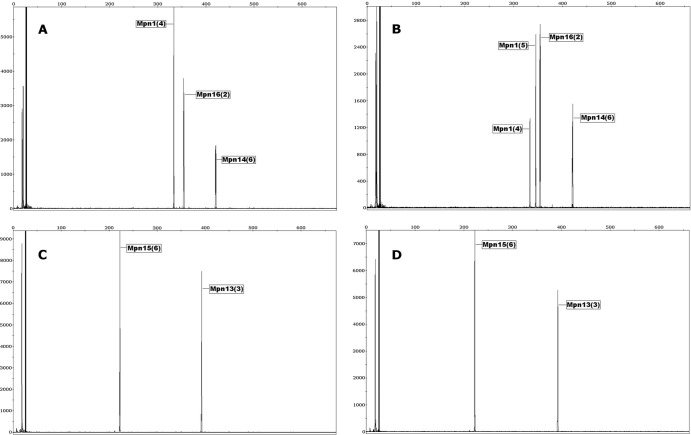

While analyzing the Mpn1 VNTR locus of all isolates, we noted an interesting observation. Although reference strain M129 displayed the same MLVA type (P) as previously reported (6), the FH typing strains acquired by our laboratory from the ATCC in 1996 and 2009 displayed two different MLVA types, which were also different from MLVA type T previously reported by Degrange et al. (6). MLVA type O was observed in the 1996 FH strain electropherogram (Fig. 1A and C), while two unique MLVA types (O and T) differing in a single tandem-repeat copy number at the Mpn1 locus were observed in the 2009 FH strain electropherogram (Fig. 1B and D). Additionally, similar allele differences were observed in Mpn1 profiles from nine independent isolates (Table 2). MLVA analysis was also performed on available primary-specimen extracts from the set of isolates displaying variable Mpn1 profiles (Table 2). Mpn1 allele variability was observed in primary-specimen extracts as well, suggesting the occurrence of allele alterations both in vitro and in vivo. For instance, in vitro shifts of the Mpn1 VNTR locus can be observed in isolates FL1, MA1, and WV8, where a single MLVA type was detectable in the specimen extract but mixed MLVA types were obtained during isolation. In contrast, mixed MLVA types were observed in the WV9 specimen extract, while only a single MLVA type was recovered during culture. Another example of an allele shift was seen in single patient isolates OR1 and OR2 obtained concurrently from right and left lung bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) specimens. One isolate was MLVA type P, while the second isolate contained types P/X based on a shift from four tandem repeats (type P) to six tandem repeats (type X) in the Mpn1 locus (Table 1). No variability was observed within the other four VNTR loci, indicating relative stability compared to Mpn1. Table 1 displays a recently proposed nomenclature system for MLVA typing based on the numeric combination of the number of tandem repeats which account for Mpn1 VNTR variation (8).

Fig 1.

MLVA typing capillary electrophoresis electropherogram of reference strains FH (1996) and FH (2009). (A) FH (1996) electropherogram displaying a single Mpn1 VNTR allele along with Mpn14 and Mpn16 VNTR loci. (B) FH (2009) electropherogram displaying two Mpn1 VNTR alleles along with Mpn14 and Mpn16 VNTR loci. (C) FH (1996) electropherogram displaying Mpn13 and Mpn15 VNTR loci. (D) FH (2009) electropherogram displaying Mpn13 and Mpn15 VNTR loci. The number of tandem repeats for each locus is indicated by parentheses. Relative fluorescence units are indicated by the y axis, and fragment size in base pairs is indicated by the top x axis.

Table 2.

Mpn1 VNTR variability in reference strain FH and nine clinical isolates

| Isolate name | Nucleic acid source | MLVA type(s)a | No. of VNTRs by locus |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mpn1 | Mpn13 | Mpn14 | Mpn15 | Mpn16 | |||

| FH (2009) | ATCC 15531 | O/T | 4–5 | 3 | 6 | 6 | 2 |

| FL1 | Specimen | NT | 4 | 4 | 6 | 7 | 2 |

| Isolate | NT | 4–5 | 4 | 6 | 7 | 2 | |

| MA1 | Specimen | J | 3 | 4 | 5 | 7 | 2 |

| Isolate | E/J | 2–3 | 4 | 5 | 7 | 2 | |

| NM2 | Specimen | NA | |||||

| Isolate | P/U | 4–5 | 4 | 5 | 7 | 2 | |

| OR2 | Specimen | NA | |||||

| Isolate | P/X | 4–6 | 4 | 5 | 7 | 2 | |

| WI7 | Specimen | M/V | 4–6 | 3 | 5 | 6 | 2 |

| Isolate | M/V | 4–6 | 3 | 5 | 6 | 2 | |

| WV8 | Specimen | J | 3 | 4 | 5 | 7 | 2 |

| Isolate | J/P | 3–4 | 4 | 5 | 7 | 2 | |

| WV9 | Specimen | E/J | 2–3 | 4 | 5 | 7 | 2 |

| Isolate | J | 3 | 4 | 5 | 7 | 2 | |

| 1801 | Specimen | NA | |||||

| Isolate | O/W | 4–6 | 3 | 6 | 6 | 2 | |

| 3064 | Specimen | NA | |||||

| Isolate | P/U | 4–5 | 4 | 5 | 7 | 2 | |

NA, not available; NT, untypeable using the scheme proposed by Degrange et al. (6).

To further test the stability of the Mpn1 VNTR locus, eight isolates (including the 2009 FH strain) displaying variable Mpn1 profiles and eight other isolates (including the 1996 FH strain) displaying “stable” Mpn1 profiles were passaged 10 times in SP4 medium (Table 3). MLVA analysis was performed on nucleic acid extracts collected at each passage. After 10 passages, six out of eight isolates with initially variable Mpn1 VNTRs, including the 2009 FH strain, evolved to a specific Mpn1 allele with either single or double tandem-repeat insertions (n = 6) or a double tandem-repeat deletion (n = 1, isolate 1801) (Table 3). Isolates 382 and OR2 still presented mixed Mpn1 alleles after 10 passages. After the third passage, the 1996 FH strain displayed a variable Mpn1 profile similar to the one observed in the 2009 FH strain (O/T), while MLVA types for the other seven isolates with stable Mpn1 profiles remained unchanged. No variability was observed in the other four VNTR loci from any of the isolates tested after 10 passages (data not shown).

Table 3.

Mpn1 VNTR locus stability after in vitro culture passage

| Isolate | Mpn1 profile by passage no. |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Passage 0 |

Passage 10 |

|||

| MLVA type(s) | No. of VNTRs | MLVA type(s) | No. of VNTRs | |

| FH (2009) | O/T | 4–5 | T | 5 |

| FH (1996) | O | 4 | O/T | 4–5 |

| MA1 | E/J | 2–3 | J | 3 |

| NM2 | P/U | 4–5 | U | 5 |

| OR2 | P/X | 4–6 | E/X | 2–6 |

| WV8 | J/P | 3–4 | P | 4 |

| 382 | E/P | 2–4 | E/P | 2–4 |

| 1801 | O/W | 4–6 | O | 4 |

| 3064 | P/U | 4–5 | U | 5 |

| NM1 | P | 4 | P | 4 |

| NM3 | U | 5 | U | 5 |

| OR1 | P | 4 | P | 4 |

| 550 | Z | 7 | Z | 7 |

| 674 | O | 4 | O | 4 |

| 1006 | C | 2 | C | 2 |

| 1134 | H | 3 | H | 3 |

DISCUSSION

MLVA typing has been increasingly used successfully to genotype a number of microbial species (26). Recent studies have adapted MLVA typing to genotype several Mycoplasma species, including Mycoplasma pneumoniae (2, 3, 6, 8), Mycoplasma bovis (14), Mycoplasma genitalium (1), and Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae (27). MLVA analysis of M. pneumoniae has been shown to have significantly greater discriminatory power than P1 typing methods previously used (6). This procedure will likely aid in providing greater resolution of M. pneumoniae strains derived from sporadic cases, epidemiological studies, and, most importantly, during outbreaks. In this study, we evaluated the recent MLVA typing scheme developed by Degrange et al. (6) to genotype a large, global collection of M. pneumoniae clinical isolates and primary specimens that span over 50 years and represent six countries on three continents.

MLVA type P was the most prevalent type identified, found in all six countries included in this study and previously found in Germany, Japan, Belgium, Tunisia, France, England, and Wales (2, 3, 6, 8). Geographical clustering of MLVA types was observed both in Canada and the United States. Three different isolates obtained from urinary tract specimens in Ottawa, Canada (11), shared the same MLVA type. In the United States, MLVA typing allowed analysis of a number of isolates collected from eight different M. pneumoniae CAP outbreaks. Clonal spread of specific strains based on MLVA type was identified in five of the eight outbreaks although these findings are based upon a limited number of isolates recovered. These data are consistent with a recent M. pneumoniae outbreak in a public school in France in which a single clone was identified based upon MLVA analysis of eight DNA extracts from positive primary specimens (13). Collectively, these observations may indicate that a single MLVA type identified during an outbreak might, in some instances, be a function of clinical specimen and isolate sampling size and thus be less likely to exist when larger populations are queried over the course of an investigation. Clearly, more extensive research needs to be performed to understand the potential clonal spread that may occur during M. pneumoniae outbreaks. Recent reports from England and Wales identified several distinct MLVA types in nucleic acid extracts from primary specimens, but specific MLVA type clusters were not observed (2, 3). Further, MLVA analysis of 54 M. pneumoniae-positive primary specimens from individual sporadic cases collected in Germany from 2006 to 2011 revealed 20 different MLVA types (8). Likewise, our results indicate the lack of a specific link between year of isolation and MLVA type clustering among isolates collected from individual cases. Similarly, the 10 M. pneumoniae macrolide-resistant isolates, which included nine U.S. isolates and one Danish isolate, did not exhibit a particular MLVA type cluster. This observation parallels results previously reported (6). Further analysis of clinical data is needed to fully investigate the possible clinical relevance of MLVA types.

Two strains (M129 and M2018) tested in the present study and by Degrange et al. displayed the same MLVA type (6), confirming interlaboratory consistency of MLVA typing. However, MLVA results of the typing strain FH differed. Degrange et al. reported the FH strain as having MLVA type T (6), while in our study, two FH strains (obtained from the ATCC in 1996 and 2009) displayed MLVA type O and a mixed MLVA type O/T, respectively. Moreover, mixed MLVA types were also observed in nine different isolates and two primary-specimen extracts (Table 2). Variability within a different VNTR locus (Mpn14) has previously been observed when M. pneumoniae was passaged in guinea pigs (8). Other reports have shown relatively stable in vivo and in vitro reliability of the five VNTR loci (6, 8). Conversely, our results show inconsistency of the defined tandem repeats for the Mpn1 VNTR locus, thereby rendering these strains “untypeable” using the current MLVA nomenclature scheme. The possibility of a coinfection by two different strains is remote because only tandem-repeat insertions or deletions in the Mpn1 locus were observed, suggesting a VNTR shift rather than the presence of multiple strains. The presence of mixed Mpn1 alleles in both extracts and isolates may suggest the temporary existence of a mixed bacterial population while a tandem-repeat shift within the Mpn1 locus is occurring. Both insertions and deletions of tandem repeats were observed among the isolates displaying variable Mpn1 alleles, but insertions were more commonly found. However, no clear trend in specific allele pattern shift was identified among the strains tested.

Allelic variation in the Mpn1 VNTR locus may not be all that surprising since it is located in the coding region of hsdS, a gene encoding the S subunit of a type I restriction-modification enzyme (15) which is known to be variable (17). It is possible that some strains may be more susceptible to specific genetic shifts and rearrangements due to selective pressures within defined populations, thereby restricting this allele shift to only a subset of strains. However, this does not explain allelic shifts observed during in vitro culturing. A previous report shows that variable numbers of tandem repeats have occurred within virulence gene regions during persistent Haemophilus influenzae host colonization (16). Additional studies are required to understand the significance of the observed genetic shifts in M. pneumoniae.

Originally founded on the observed stability of each of the five VNTRs, the current nomenclature system for MLVA typing may benefit from a modification to account for the frequently observed Mpn1 VNTR variability. Additionally, several MLVA types obtained in this study and previous studies (2, 3, 8) could not be classified according to the published scheme based on the 26 tandem-repeat combinations assigned to the alphabetic characters A to Z (6). Since even more tandem-repeat combinations are possible, the proposed nomenclature system by Dumke and Jacobs (8) based on the numeric combination of the number of tandem repeats for the characterization of a typed strain (e.g., Table 1, isolate MA1, 2–3/4/5/7/2,) may be more appropriate. The frequently observed variability of the Mpn1 locus within this typing scheme would obviously lessen the likelihood of being able to identify a “true” clonal spread in most instances. Identification of additional markers could potentially augment MLVA typing and possibly increase the discriminatory level between strains.

Although the current M. pneumoniae MLVA typing method may benefit from further refinement, it currently still exceeds the discriminatory power of previous typing methods based on P1 gene subtyping. While P1 typing identified only two subtypes and a few variants, MLVA typing is currently able to discriminate isolates into over 26 types. Another major advantage of MLVA typing is its adaptability for typing not only isolates but also primary-specimen extracts, thereby extending the range and speed of molecular characterization of M. pneumoniae for epidemiological studies and outbreak investigations. This may allow for a more effective public health response and implementation of appropriate infection control measures during outbreaks. In addition, this typing system may allow better insight into the molecular evolution of M. pneumoniae.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Department of the Navy, Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government. This work was prepared as part of their official duties. Title 17 U.S.C. §105 provides that “Copyright protection under this title is not available for any work of the United States Government” (25). Title 17 U.S.C. §101 defines a U.S. Government work as a work prepared by a military service member or employee of the U.S. Government as part of that person's official duties (25).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 5 September 2012

REFERENCES

- 1.Cazanave C, Charron A, Renaudin H, Bebear C. 2012. Method comparison for molecular typing of French and Tunisian Mycoplasma genitalium-positive specimens. J. Med. Microbiol. 61:500–506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chalker V, et al. 2012. Increased detection of Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection in children in England and Wales, October 2011 to January 2012. Euro Surveill. 17:20081 http://www.eurosurveillance.org/ViewArticle.aspx?ArticleId=20081 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chalker V, Stocki T, Mentasti M, Fleming D, Harrison TG. 2011. Increased incidence of Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection in England and Wales in 2010: multilocus variable number tandem repeat analysis typing and macrolide susceptibility. Euro Surveill. 16:19865 http://www.eurosurveillance.org/ViewArticle.aspx?ArticleId=19865. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cousin-Allery A, et al. 2000. Molecular typing of Mycoplasma pneumoniae strains by PCR-based methods and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. Application to French and Danish isolates. Epidemiol. Infect. 124:103–111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cunha BA. 2006. The atypical pneumonias: clinical diagnosis and importance. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 12:12–24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Degrange S, et al. 2009. Development of multiple-locus variable-number tandem-repeat analysis for the molecular typing of Mycoplasma pneumoniae. J. Clin. Microbiol. 47:914–923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dorigo-Zetsma JW, Verkooyen RP, Van Helden HP, Van Der Nat H, Van Den Bosch J. 2001. Molecular detection of Mycoplasma pneumoniae in adults with community-acquired pneumonia requiring hospitalization. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:1184–1186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dumke R, Jacobs E. 2011. Culture-independent multi-locus variable-number tandem-repeat analysis (MLVA) of Mycoplasma pneumoniae. J. Microbiol. Methods 86:393–396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dumke R, et al. 2006. Culture-independent molecular subtyping of Mycoplasma pneumoniae in clinical samples. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44:2567–2570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Foy HM. 1993. Infections caused by Mycoplasma pneumoniae and possible carrier state in different populations of patients. Clin. Infect. Dis. 17(Suppl 1):S37–S46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goulet M, Dular R, Tully JG, Billowes G, Kasatiya S. 1995. Isolation of Mycoplasma pneumoniae from the human urogenital tract. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:2823–2825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klement E, et al. 2006. Identification of risk factors for infection in an outbreak of Mycoplasma pneumoniae respiratory tract disease. Clin. Infect. Dis. 43:1239–1245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pereyre S, Renaudin H, Charron A, Bebear C. 2012. Clonal spread of Mycoplasma pneumoniae in primary school, Bordeaux, France. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 18:343–345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pinho L, Thompson G, Rosenbusch R, Carvalheira J. 2012. Genotyping of Mycoplasma bovis isolates using multiple-locus variable-number tandem-repeat analysis. J. Microbiol. Methods 88:377–385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Razin S, Yogev D, Naot Y. 1998. Molecular biology and pathogenicity of mycoplasmas. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62:1094–1156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Renders N, et al. 1999. Variable numbers of tandem repeat loci in genetically homogeneous Haemophilus influenzae strains alter during persistent colonisation of cystic fibrosis patients. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 173:95–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rocha EP, Blanchard A. 2002. Genomic repeats, genome plasticity and the dynamics of Mycoplasma evolution. Nucleic Acids Res. 30:2031–2042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sasaki T, et al. 1996. Epidemiological study of Mycoplasma pneumoniae infections in Japan based on PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism of the P1 cytadhesin gene. J. Clin. Microbiol. 34:447–449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schwartz SB, Mitchell SL, Thurman KA, Wolff BJ, Winchell JM. 2009. Identification of P1 variants of Mycoplasma pneumoniae by use of high-resolution melt analysis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 47:4117–4120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schwartz SB, Thurman KA, Mitchell SL, Wolff BJ, Winchell JM. 2009. Genotyping of Mycoplasma pneumoniae isolates using real-time PCR and high-resolution melt analysis. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 15:756–762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spuesens EB, et al. 2012. Macrolide resistance determination and molecular typing of Mycoplasma pneumoniae in respiratory specimens collected between 1997 and 2008 in the Netherlands. J. Clin. Microbiol. 50:1999–2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spuesens EBM, et al. 2010. Macrolide resistance determination and molecular typing of Mycoplasma pneumoniae by pyrosequencing. J. Microbiol. Methods 82:214–222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tsiodras S, Kelesidis I, Kelesidis T, Stamboulis E, Giamarellou H. 2005. Central nervous system manifestations of Mycoplasma pneumoniae infections. J. Infect. 51:343–354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tully JG, Rose DL, Whitcomb RF, Wenzel RP. 1979. Enhanced isolation of Mycoplasma pneumoniae from throat washings with a newly modified culture medium. J. Infect. Dis. 139:478–482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.U.S. Copyright Office 2011. Copyright law of the United States and related laws contained in Title 17 of the United States Code. Circular 92. Library of Congress, Washington, DC: http://www.copyright.gov/title17/circ92.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 26.van Belkum BA. 2007. Tracing isolates of bacterial species by multilocus variable number of tandem repeat analysis (MLVA). FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 49:22–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vranckx K, et al. 2011. Multiple-locus variable-number tandem-repeat analysis is a suitable tool for differentiation of Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae strains without cultivation. J. Clin. Microbiol. 49:2020–2023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Waites KB, Talkington DF. 2004. Mycoplasma pneumoniae and its role as a human pathogen. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 17:697–728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wolff BJ, Thacker WL, Schwartz SB, Winchell JM. 2008. Detection of macrolide resistance in Mycoplasma pneumoniae by real-time PCR and high resolution melt analysis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:3542–3549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]