Abstract

A novel biochemical technique, the Carba NP test, has been evaluated to detect carbapenemase production in Pseudomonas spp. This test was specific (100%), sensitive (94.4%), and rapid (<2 h). This cost-effective test, which could be implemented in any microbiology laboratory, offers a reliable technique for identification of carbapenemase-producing Pseudomonas spp.

TEXT

P seudomonas aeruginosa is intrinsically resistant to a number of β-lactams due to the low permeability of its outer membrane, the constitutive expression of various efflux pumps, and the production of β-lactamases (5). Acquired resistance to broad-spectrum β-lactams is increasingly observed in P. aeruginosa. Currently, PER-, VEB-, and GES-type enzymes are the most frequently observed extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs) identified in Pseudomonas spp. (5, 7). Therefore, carbapenems are considered crucial for treating many P. aeruginosa-associated infections.

In Pseudomonas spp., carbapenem resistance may be related either to a decreased bacterial outer membrane permeability (e.g., loss or modification of the OprD2 porin or overexpression of efflux pumps), often associated with overexpression of β-lactamases possessing no significant carbapenemase activity (AmpCs), or to expression of true carbapenemases (5, 14). In Pseudomonas spp., those carbapenemases are mostly metallo-β-lactamases (MBLs) of the VIM, IMP, SPM, GIM, AIM, DIM, and NDM types and, to a lesser extent, Ambler class A carbapenemases of the KPC and GES types (GES-2, -4, -5, -6, and -11) (2, 3, 12).

Screening of carbapenemase producers among carbapenem-resistant P. aeruginosa isolates is important since many carbapenemase genes are plasmid carried and easily transferable. Phenotypic techniques for in vitro identification of carbapenemase production, such as the modified Hodge test, are not highly sensitive and specific (10). Detection of MBL and KPC producers may be based on the inhibitory properties of several molecules (EDTA and boronic acid, respectively) and requires a significant degree of expertise (9). Indeed, inhibition of carbapenemase activity is more difficult to show in P. aeruginosa than in Enterobacteriaceae due to its low outer membrane permeability (11). Molecular detection of carbapenemase genes is an interesting alternative but remains costly and also requires a high degree of expertise that is not available for nonspecialized laboratories (16). Both the phenotypic and molecular techniques are time-consuming and therefore do not correspond to the real clinical need. However, the detection of carbapenemase producers must actually be followed by a rapid adaptation of the antibiotic therapy and by the isolation of colonized patients in order to prevent the development of nosocomial outbreaks (6).

The aim of this study was to determine the value of the newly developed Carba NP test (8) to discriminate between carbapenemase- and non-carbapenemase-producing isolates among Pseudomonas spp.

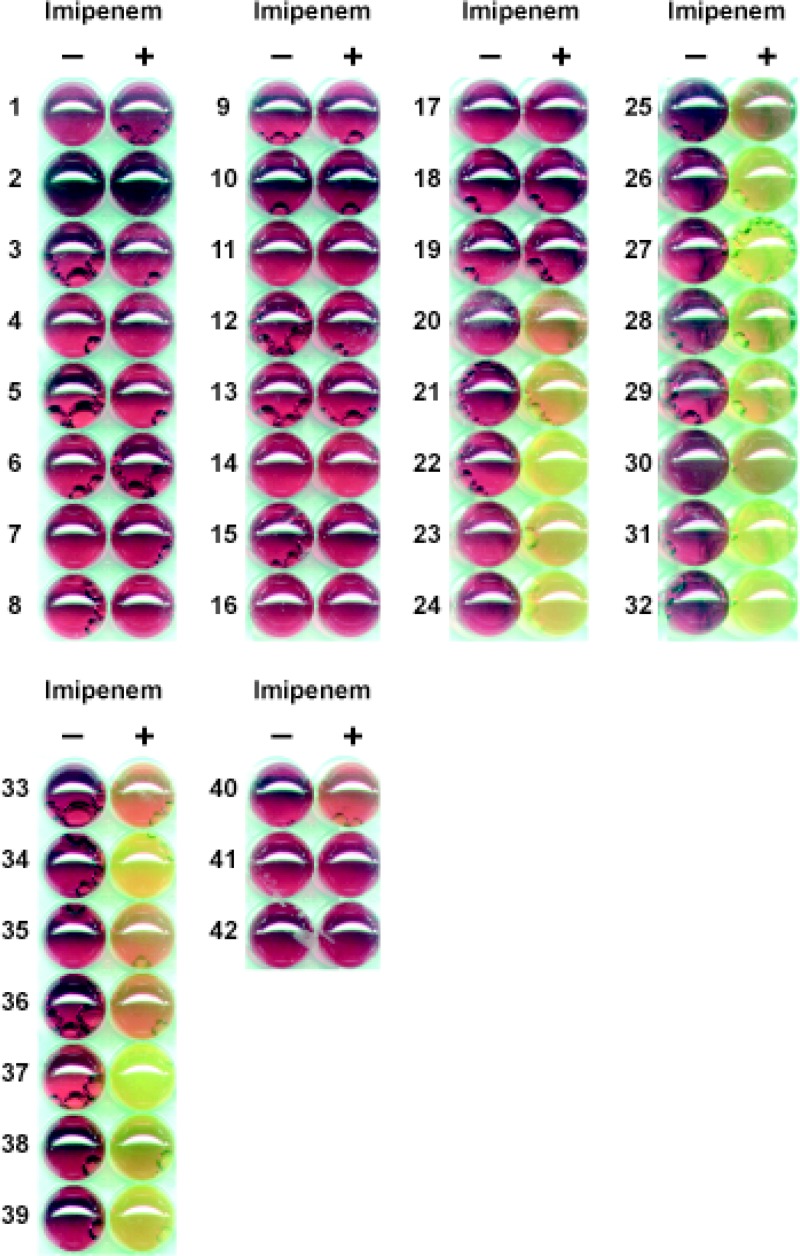

The Carba NP test is based on biochemical detection of the hydrolysis of the β-lactam ring of a carbapenem, imipenem, followed by color change of a pH indicator (Fig. 1). This test was performed on strains grown on Mueller-Hinton agar plates (Becton, Dickinson, Le Pont de Chaix, France) at 37°C for 18 to 22 h (8). Briefly, one calibrated loop (10 μl) of the tested strain directly recovered from the Mueller-Hinton agar plate was resuspended in 100 μl of a 20 mM Tris-HCl lysis buffer (bacterial protein extraction reagent II [B-PER II]; Pierce, Thermo Scientific, Villebon-sur-Yvette, France), vortexed for 1 min, and further incubated at room temperature for 30 min. This bacterial suspension was centrifuged at 10,000 × g at room temperature for 5 min. Thirty microliters of the supernatant, corresponding to the enzymatic bacterial suspension, was mixed in a well of a 96-well tray with 100 μl of a 1-ml solution made of 3 mg of imipenem monohydrate (Sigma, Saint-Quentin-Fallavier, France) (pH 7.8) phenol red solution and 0.1 mM ZnSO4 (Merck Millipore, Guyancourt, France). The phenol red solution used was prepared by taking 2 ml of a phenol red (Merck Millipore) solution (0.5%, wt/vol) to which 16.6 ml of distilled water was added. The pH value was then adjusted to 7.8 by adding drops of 1 N NaOH. A mixture of the phenol red solution and the enzymatic suspension being tested was incubated at 37°C for a maximum of 2 h. Test results were interpreted by technicians who were blinded to the identity of the samples.

Fig 1.

Examples of results for non-carbapenemase-producing and carbapenemase-producing Pseudomonas spp. from the Carba NP test. Non-carbapenemase producers are as follows: P. aeruginosa 76110, wild type, P. aeruginosa PU 21, wild type; P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853, wild type; P. aeruginosa PAO1, wild type; P. aeruginosa HT29, OprM porin deficient; P. aeruginosa PAO1, OprD porin deficient; P. aeruginosa PAO1, overexpressing MexC/D-OprM efflux pump; P. aeruginosa, overexpressing MexA/B-OprM efflux pump; P. aeruginosa PAO1, overexpressing MexX/Y-OprM efflux pump; P. aeruginosa 3-12, overexpressing the chromosomal AmpC; P. aeruginosa, GES-1; P. aeruginosa, GES-9; P. aeruginosa ED, OXA-28; P. aeruginosa, OXA-32; P. aeruginosa, SHV-2a; P. aeruginosa, SHV-5; P. aeruginosa, PER-1; P. aeruginosa, VEB-1; and P. aeruginosa, BEL-1 (rows 1 to 19, respectively). Carbapenemase producers are as follows; P. aeruginosa 16, SPM-1; P. stutzeri, DIM-1; P. aeruginosa P13, KPC-2; P. aeruginosa PA-2, KPC-2; P. aeruginosa, VIM-1; Pseudomonas fluorescens COU, VIM-2; P. aeruginosa REZ, VIM-2; P. putida, VIM-2; P. stutzeri, VIM-2; P. aeruginosa CAS, VIM-4; P. aeruginosa JAC, VIM-4; P. aeruginosa 1287, IMP-1; P. stutzeri PB207, IMP-1; P. putida NTU 92/99, IMP-1; P. aeruginosa 0607097, IMP-2; P. aeruginosa, IMP-13; P. aeruginosa 453, NDM-1; P. aeruginosa 353, NDM-1; P. aeruginosa 73-56, GIM-1; P. aeruginosa WCH2677, AIM-1; P. fluorescens, BIC-1; P. aeruginosa GW-1, GES-2; and P. aeruginosa, GES-5 (rows 20 to 42, respectively). Note that strains in rows 41 and 42 gave false-negative results.

Thirty-six carbapenemase-producing isolates belonging to several Pseudomonas species, isolated from various clinical samples and of global origin, have been included in this study (Table 1). The strains had been previously characterized for their β-lactamase content at the molecular level. This collection also contained 72 strains representative of the main β-lactam resistance phenotypes and β-lactamase diversity identified in Pseudomonas spp. (including ESBLs of PER, VEB, BEL, SHV, TEM, and OXA types) (Table 2). In addition, most of those strains were resistant to carbapenems.

Table 1.

Detection of carbapenemase activity in carbapenemase producers by using the Carba NP test

| Ambler class | Carbapenemase type | Organism | β-Lactamase | MIC (mg/liter) |

Carba NP test result | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IMP | MER | |||||

| A | KPC | P. aeruginosa COL | KPC-2 | >32 | >32 | + |

| P. aeruginosa P13 | KPC-2 | >32 | >32 | + | ||

| P. aeruginosa PA-2 | KPC-2 | >32 | >32 | + | ||

| P. aeruginosa PA-3 | KPC-2 | >32 | >32 | + | ||

| GES | P. aeruginosa GW-1 | GES-2 | 3 | 1 | − | |

| P. aeruginosa P35 | GES-5 | >32 | >32 | − | ||

| B | VIM | P. aeruginosa P0510 | VIM-1 | >32 | >32 | + |

| Pseudomonas fluorescens COU | VIM-2 | >32 | >32 | + | ||

| P. aeruginosa REZ | VIM-2 | >32 | >32 | + | ||

| P. putida 9335 | VIM-2 | >32 | >32 | + | ||

| P. stutzeri P511503100 | VIM-2 | >32 | >32 | + | ||

| P. aeruginosa BY25753 | VIM-2 | >32 | >32 | + | ||

| P. aeruginosa V919005 | VIM-2 | >32 | >32 | + | ||

| P. aeruginosa AK5493 | VIM-2 | >32 | >32 | + | ||

| P. aeruginosa KA-209 | VIM-2 | >32 | >32 | + | ||

| P. putida NTU 91/99 | VIM-2 | >32 | >32 | + | ||

| P. aeruginosa CAS | VIM-4 | >32 | >32 | + | ||

| P. aeruginosa JAC | VIM-4 | >32 | >32 | + | ||

| IMP | P. aeruginosa 12870 | IMP-1 | 12 | >32 | + | |

| P. stutzeri PB207 | IMP-1 | 2 | 4 | + | ||

| P. putida NTU 92/99 | IMP-1 | 1 | 0.19 | + | ||

| P. aeruginosa | IMP-1 | >32 | >32 | + | ||

| P. aeruginosa 0607097 | IMP-2 | >32 | >32 | + | ||

| P. aeruginosa ITA | IMP-13 | >32 | >32 | + | ||

| NDM | P. aeruginosa 453 | NDM-1 | >32 | >32 | + | |

| P. aeruginosa 353 | NDM-1 | >32 | >32 | + | ||

| GIM | P. aeruginosa 73-12198 | GIM-1 | 3 | 0.19 | + | |

| P. aeruginosa 73-15574 | GIM-1 | >32 | >32 | + | ||

| P. aeruginosa 73-15553A | GIM-1 | >32 | >32 | + | ||

| P. aeruginosa 73-5674 | GIM-1 | >32 | >32 | + | ||

| AIM | P. aeruginosa WCH2677 | AIM-1 | >32 | >32 | + | |

| P. aeruginosa WCH2813 | AIM-1 | >32 | >32 | + | ||

| P. aeruginosa WCH2837 | AIM-1 | >32 | >32 | + | ||

| SPM | P. aeruginosa 16 | SPM-1 | >32 | >32 | + | |

| DIM | P. stutzeri 13 | DIM-1 | >32 | >32 | + | |

| BIC | P. fluorescens | BIC-1 | >32 | 4 | + | |

Table 2.

Results of Carba NP test on non-carbapenemase-producing Pseudomonas spp.

| Resistance mechanism(s)a | Organism | Resistance determinant(s)b | MIC (mg/liter) |

Carba NP test result | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IMP | MER | ||||

| Wild type | P. aeruginosa 76110 | None | 0.75 | 0.19 | − |

| P. aeruginosa PU21 | None | 1.5 | 0.75 | − | |

| P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853 | None | 2 | 0.25 | − | |

| P. aeruginosa PAO1 | None | 1 | 0.5 | − | |

| P. putida CIP 55-5 | None | 0.5 | 3 | − | |

| AmpC overproduction | P. aeruginosa 3-12 | AmpC | 3 | 0.25 | − |

| P. aeruginosa VED | AmpC | 0.12 | 0.19 | − | |

| Efflux | P. aeruginosa PAO1 | MexC/D-OprJ | >32 | 4 | − |

| P. aeruginosa PT629 | MexA/B-OprM | 1.5 | 1.5 | − | |

| P. aeruginosa PAO1 | MexX/Y-OprM | 1.5 | 0.75 | − | |

| Porin deficiency | P. aeruginosa PAO1 | OprM deficient | 0.75 | 0.5 | − |

| P. aeruginosa H729 | OprD deficient | >32 | 6 | − | |

| P. aeruginosa Paeβ-02 | OprD deficient | 4 | 4 | − | |

| P. aeruginosa Paeβ-05 | OprD deficient | 16 | 8 | − | |

| P. aeruginosa Paeβ-30 | OprD deficient | 8 | 8 | − | |

| P. aeruginosa Paeβ-31 | OprD deficient | 16 | 8 | − | |

| Porin deficiency and efflux | P. aeruginosa Paeβ-19 | OprD deficient + MexA/B-OprM | 4 | 4 | − |

| P. aeruginosa Paeβ-29 | OprD deficient + MexA/B-OprM + MexX/Y-OprM | 16 | 32 | − | |

| P. aeruginosa Paeβ-01 | OprD deficient + MexX/Y-OprM + MexC/D-OprJ | 4 | 8 | − | |

| Porin deficiency and AmpC overproduction | P. aeruginosa Paeβ-03 | OprD deficient + AmpC | 16 | 8 | − |

| P. aeruginosa Paeβ-12 | OprD deficient + AmpC | 16 | 8 | − | |

| P. aeruginosa Paeβ-13 | OprD deficient + AmpC | 16 | 8 | − | |

| P. aeruginosa Paeβ-14 | OprD deficient + AmpC | 16 | 4 | − | |

| P. aeruginosa Paeβ-16 | OprD deficient + AmpC | 32 | 4 | − | |

| P. aeruginosa Paeβ-23 | OprD deficient + AmpC | 32 | 16 | − | |

| P. aeruginosa Paeβ-25 | OprD deficient + AmpC | 8 | 8 | − | |

| P. aeruginosa Paeβ-26 | OprD deficient + AmpC | 4 | 4 | − | |

| P. aeruginosa Paeβ-32 | OprD deficient + AmpC | 64 | 16 | − | |

| Porin deficiency, AmpC overproduction, and efflux | P. aeruginosa Paeβ-04 | OprD deficient + AmpC + MexA/B-OprM | 16 | 16 | − |

| P. aeruginosa Paeβ-24 | OprD deficient + AmpC + MexA/B-OprM | 32 | 32 | − | |

| P. aeruginosa Paeβ-28 | OprD deficient + AmpC + MexA/B-OprM | 16 | 4 | − | |

| P. aeruginosa Paeβ-15 | OprD deficient + AmpC + MexX/Y-OprM | 16 | 8 | − | |

| P. aeruginosa Paeβ-21 | OprD deficient + AmpC + MexX/Y-OprM | 16 | 32 | − | |

| P. aeruginosa Paeβ-22 | OprD deficient + AmpC + MexC/D-OprJ | 8 | 4 | − | |

| P. aeruginosa Paeβ-06 | OprD deficient + AmpC + MexX/Y-OprM + MexC/D-OprJ | 16 | 8 | − | |

| P. aeruginosa Paeβ-07 | OprD deficient + AmpC + MexX/Y-OprM + MexC/D-OprJ | 16 | 8 | − | |

| P. aeruginosa Paeβ-08 | OprD deficient + AmpC + MexX/Y-OprM + MexC/D-OprJ | 16 | 8 | − | |

| P. aeruginosa Paeβ-09 | OprD deficient + AmpC + MexX/Y-OprM + MexC/D-OprJ | 16 | 8 | − | |

| P. aeruginosa Paeβ-11 | OprD deficient + AmpC + MexX/Y-OprM + MexC/D-OprJ | 16 | 8 | − | |

| P. aeruginosa Paeβ-17 | OprD deficient + AmpC + MexX/Y-OprM + MexC/D-OprJ | 32 | 8 | − | |

| P. aeruginosa Paeβ-18 | OprD deficient + AmpC + MexA/B-OprM + MexX/Y-OprM | 64 | 64 | − | |

| P. aeruginosa Paeβ-27 | OprD deficient + AmpC + MexA/B-OprM + MexX/Y-OprM | 32 | 64 | − | |

| P. aeruginosa Paeβ-10 | OprD deficient + AmpC + MexA/B-OprM + MexC/D-OprJ | 16 | 8 | − | |

| P. aeruginosa Paeβ-20 | OprD deficient + AmpC + MexA/B-OprM + MexC/D-OprJ | 16 | 8 | − | |

| ESBL | P. aeruginosa F6R7 | GES-1 | 1 | 0.75 | − |

| P. aeruginosa DEJ | GES-9 | 2 | 1 | − | |

| P. aeruginosa RNL-1 | PER-1 | 6 | 6 | − | |

| P. aeruginosa A2O6 | PER-1 | 13 | 3 | − | |

| P. aeruginosa A5O6 | PER-1 | 1.5 | 0.38 | − | |

| P. aeruginosa A7O6 | PER-1 | 6 | 1 | − | |

| P. aeruginosa A3O6 | PER-1 | 3 | 1.5 | − | |

| P. aeruginosa A8O6 | PER-1 | >32 | 12 | − | |

| P. aeruginosa A4O6 | PER-1 | 12 | 3 | − | |

| P. aeruginosa E3O6 | PER-1 | >32 | 12 | − | |

| P. aeruginosa E1O6 | PER-1 | 0.25 | 0.016 | − | |

| P. aeruginosa C2O7 | PER-1 | >32 | 8 | − | |

| P. aeruginosa C1O7 | PER-1 | >32 | >32 | − | |

| P. aeruginosa 15 | VEB-1 | 2 | 1.5 | − | |

| P. aeruginosa 51170 | BEL-1 | 1 | 0.5 | − | |

| P. aeruginosa 0602-52025 | SHV2-a | 1.5 | 3 | − | |

| P. aeruginosa 1782 | SHV-5 | 2 | 2 | − | |

| P. aeruginosa SHAM | TEM-4 | 3 | 0.75 | − | |

| P. aeruginosa PU 21 | OXA-2 | 2 | 1 | − | |

| P. aeruginosa PAO38 | OXA-4 | 0.016 | 0.19 | − | |

| P. aeruginosa PU 21 | OXA-10 | 2 | 1.5 | − | |

| P. aeruginosa PU 21 | OXA-11 | 3 | 1.5 | − | |

| P. aeruginosa NAJ | OXA-13 | 2 | 1.5 | − | |

| P. aeruginosa PU 21 | OXA-14 | 2 | 2 | − | |

| P. aeruginosa MUS | OXA-18 + OXA-20 | >32 | >32 | − | |

| P. aeruginosa ED | OXA-28 | 2 | 0.75 | − | |

| P. aeruginosa PIC | OXA-31 | >32 | 1.5 | − | |

| P. aeruginosa PG13 | OXA-32 | >32 | 12 | − | |

Lack of OprD, AmpC overexpression, and efflux system overproduction were previously characterized by quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (12).

Bold AmpC corresponds to overexpression of chromosomal AmpC. Mex-type efflux systems are indicated when overexpressed.

The Carba NP test differentiated the carbapenemase producers, with the exception of several GES-type producers (Table 1 and Fig. 1), from those isolates that were carbapenem resistant due to non-carbapenemase-mediated mechanisms (the most frequent ones) such as combined mechanisms of resistance (outer membrane permeability defect associated or not with overproduction of cephalosporinase and/or ESBLs) (Table 2). The specificity and sensitivity of the test were found to be 100% and 94.4%, respectively. Interestingly, carbapenemase activity was detected in the two carbapenemase producers (IMP-1-producing Pseudomonas stutzeri PB207 and Pseudomonas putida NTU 92/99) that were basically susceptible to imipenem (MIC, ≤2 μg/ml) according to the CLSI guidelines (1) (Table 1).

The Carba NP test has multiple benefits for detecting carbapenemase activity in nonfermenters such as Pseudomonas spp. It eliminates the need for in vitro detection of carbapenemase activity (Hodge test) and for β-lactamase inhibitor-based phenotypic techniques (boronic acid for KPC and EDTA for MBLs), which both require at least 24 to 72 h to be performed. The Carba NP test is the first technique available to identify carbapenemase producers with such high specificity, sensitivity, and rapidity (less than 2 h). However, the absence of detection of GES-type carbapenemases has to be considered, especially in geographical regions with a high prevalence (i.e., Brazil and South Africa) (although other GES-producing strains shall be tested). The GES-type carbapenemases are point mutant analogues of the ESBL GES-1 that possess an additional and rather weak carbapenemase activity (4) that may explain this lack of detection. In addition, the real clinical significance of the carbapenemase activity of GES-type variants as a source of in vivo resistance to carbapenems (therapeutic failure) remains to be evaluated (13, 15).

Using this accurate test would be helpful for detecting patients infected or colonized with carbapenemase producers, which is of utmost importance for better antibiotic stewardship and prevention of outbreaks (6). Use of the Carba NP test may be useful in particular for intensive care unit (ICU) and burn patients, among whom multidrug-resistant P. aeruginosa isolates are widespread. It offers a cost-effective solution for detecting carbapenemase producers and preventing their spread, considering that they may harbor those carbapenemase genes on plasmids that can spread to other bacterial families (Enterobacteriaceae and the family that includes Acinetobacter species).

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was funded by a grant from the INSERM (UMR914).

We thank T. R. Walsh for the gift of the GIM- and AIM-positive isolates, P. Plésiat for the gift of some of the efflux and AmpC overproducers, and B. Kocic for the gift of the NDM-positive isolates.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 12 September 2012

REFERENCES

- 1.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute 2012. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; 22nd informational supplement. M100-S22. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gupta V. 2008. Metallo-β-lactamases in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Acinetobacter species. Expert Opin. Invest. Drugs 17:131–143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jovcic B, et al. 2011. Emergence of NDM-1 metallo-β-lactamase in Pseudomonas aeruginosa clinical isolates from Serbia. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55:3929–3931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kotsakis SD, Miriagou V, Tzelepi E, Tzouvelekis LS. 2010. Comparative biochemical and computational study of the role of naturally occurring mutations at Ambler positions 104 and 170 in GES β-lactamases. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:4864–4871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mesaros N, et al. 2007. Pseudomonas aeruginosa: resistance and therapeutic options at the turn of the new millennium. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 13:560–578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nordmann P, et al. 2012. Identification and screening of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 18:432–438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nordmann P, Naas T. 2010. β-Lactams and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, p 157–174 In Courvalin P, Leclercq R, Rice LB. (ed), Antibiogram. ASM Press, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nordmann P, Poirel L, Dortet L. 2012. Rapid detection of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 18:1503–1507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pasteran F, et al. 2011. A simple test for the detection of KPC and metallo-β-lactamase carbapenemase-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates with the use of meropenem disks supplemented with aminophenylboronic acid, dipicolinic acid and cloxacillin. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 17:1438–1441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pasteran F, Veliz O, Rapoport M, Guerriero L, Corso A. 2011. Sensitive and specific modified Hodge test for KPC and metallo-β-lactamase detection in Pseudomonas aeruginosa by use of a novel indicator strain, Klebsiella pneumoniae ATCC 700603. J. Clin. Microbiol. 49:4301–4303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Picao RC, et al. 2008. Metallo-β-lactamase detection: comparative evaluation of double-disk synergy versus combined disk tests for IMP-, GIM-, SIM-, SPM-, or VIM-producing isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 46:2028–2037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Poirel L, Rodriguez-Martinez JM, Al Naiemi N, Debets-Ossenkopp YJ, Nordmann P. 2010. Characterization of DIM-1, an integron-encoded metallo-β-lactamase from a Pseudomonas stutzeri clinical isolate in the Netherlands. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:2420–2424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Poirel L, Weldhagen GF, De Champs C, Nordmann P. 2002. A nosocomial outbreak of Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates expressing the extended-spectrum β-lactamase GES-2 in South Africa. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 49:561–565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rodriguez-Martinez JM, Poirel L, Nordmann P. 2009. Molecular epidemiology and mechanisms of carbapenem resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:4783–4788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang C, Cai P, Chang D, Mi Z. 2006. A Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolate producing the GES-5 extended-spectrum β-lactamase. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 57:1261–1262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Woodford N. 2010. Rapid characterization of β-lactamases by multiplex PCR. Methods Mol. Biol. 642:181–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]