Abstract

A total of 434 methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) baseline isolates were collected from subjects enrolled in a prospective, double-blind randomized trial comparing linezolid versus vancomycin for the treatment of nosocomial pneumonia. Isolates were susceptibility tested by broth microdilution, examined for inducible clindamycin resistance by D-test, and screened for heterogeneous resistance to vancomycin (hVISA) by the Etest macromethod. All strains were subjected to Panton-Valentine leukocidin (PVL) screening, and SCCmec, pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE), and spa typing. Selected strains were evaluated by multilocus sequence typing (MLST). Clonal complexes (CCs) were assigned based on the spa and/or MLST results. Most strains were CC5 (56.0%), which originated from North America (United States) (CC5-MRSA-SCCmec II/IV; 70.0%), Asia (CC5-MRSA-II; 14.0%) and Latin America (CC5-MRSA-I/II; 12.3%). The second- and third-most-prevalent clones were CC8-MRSA-IV (23.3%) and CC239-MRSA-III (11.3%), respectively. Furthermore, the CC5-MRSA-I/II clone predominated in Asia (50.7% within this region) and Latin America (66.7%), followed by CC239-MRSA-III (32.8% and 28.9%, respectively). The European strains were CC8-MRSA-IV (34.5%), CC22-MRSA-IV (18.2%), or CC5-MRSA-I/II/IV (16.4%), while the U.S. MRSA isolates were CC5-MRSA-II/IV (64.4%) or CC8-MRSA-IV (28.8%). Among the U.S. CC8-MRSA-II/IV strains, 73.7% (56/76 [21.2% of all U.S. MRSA strains]) clustered within USA300. One strain from the United States (USA800) was intermediate to vancomycin (MIC, 4 μg/ml). All remaining strains were susceptible to linezolid, daptomycin, vancomycin, and teicoplanin. hVISA strains (14.5%) were predominantly CC5-MRSA-II, from South Korea, and belonged to a single PFGE type. Overall, each region had two predominant clones. The USA300 rate corroborates previous reports describing increased prevalence of USA300 strains causing invasive infections. The prevalence of hVISA was elevated in Asia, and these strains were associated with CC5.

INTRODUCTION

Staphylococcus aureus remains a leading cause of human bacterial infections worldwide, and the incidence of health care-associated and community-acquired (CA) infections caused by this organism has increased steadily (7). This species ranks as the main pathogen responsible for nosocomial bloodstream infections (BSI), hospital-acquired bacterial pneumonia (HABP) and ventilator-acquired bacterial pneumonia (VABP), and skin and skin structure infections (SSSI) (20, 25). Many infections are caused by methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) isolates, and recent studies have demonstrated an increased MRSA incidence over the last decade (31, 34, 43, 51). These facts, along with complicating risk factors, comorbidity, and mortality (between 40 and 60%), result in extended hospitalizations, escalated health care costs, and the requirement of potent, broad-spectrum agents often used in combination regimens (7).

The population structure of MRSA strains is constantly evolving. These epidemiologic alterations reflect in changes in the incidence and characteristics of MRSA infections in the hospital and community settings. In the United States, the USA300 clone emerged as important cause of CA-MRSA infections, predominantly SSSI (29). Recently, this clone has also been implicated as a cause of health care-associated (HA-MRSA) and invasive infections (22, 39, 45). However, recent studies have demonstrated an overall increase of noninvasive, community-onset, MRSA infections, while the incidence of HA-MRSA and invasive infections declined (8, 21, 31, 51). Similar changes in the MRSA epidemiology among European hospitals have been reported in numerous studies as well (6, 9, 14, 16). Moreover, CA-MRSA has recently emerged across Europe (2, 19, 24, 26), and the incidence of HA-MRSA BSI has decreased or remained stable in several countries in Europe (24).

From October 2004 through January 2010, a phase IV randomized, double-blind, actively controlled study was performed to assess the efficacy and safety of linezolid compared with dose-optimized vancomycin for the treatment of culture-proven MRSA nosocomial pneumonia (NP) in hospitalized adults (53). In this study, a significantly better clinical cure rate was observed with linezolid (58%) than with vancomycin (47%). Favorable results were also obtained for linezolid (58%) in terms of microbiological cure rates compared with vancomycin (47%). During this trial, a large collection of geographically diverse MRSA isolates was obtained. This study sought to further characterize this worldwide MRSA population and evaluate possible changing trends of genotypes, molecular characteristics, and antimicrobial susceptibility profiles of strains responsible for NP between 2004 and 2010.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

A total of 434 microbiologically evaluable baseline MRSA isolates were collected (from October 2004 through January 2010) from hospitalized subjects with clinically documented NP proven to be caused by MRSA. Subjects were required to have a baseline tracheal aspirate, bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid, or high-quality sputum specimen (defined as having less than 10 squamous epithelial cells and greater or equal to 25 leukocytes per high-power field) positive for MRSA (53). Baseline isolates included in this study originated from patients enrolled in the clinical trial according to preestablished inclusion criteria. Therefore, MRSA isolates included in this study were not consecutively collected and did not follow a prevalence mode design (53). Specimens were processed and cultured for bacterial pathogens according to the standard procedure at each medical center laboratory site. Individual investigators forwarded MRSA isolates to the Covance Central Laboratory Service (Indianapolis, IN) for confirmation of identification and susceptibility testing. MRSA isolates were subsequently sent to JMI Laboratories (North Liberty, IA) for further studies. Only one strain per patient was included in this analysis.

The strains included in this study were predominantly collected from enrolled subjects in the United States (264 [60.8%]), followed by smaller numbers of subjects from the following countries: South Korea (44 [10.1%]), Brazil (18 [4.1%]), Belgium (18 [4.1%]) Taiwan (15 [3.5%]), Russia (13 [3.0%]), Mexico (10 [2.3%]), Portugal (8 [1.8%]), Chile (8 [1.8%]), France (8 [1.8%]), Malaysia (6 [1.4%]), Puerto Rico (5 [1.2%]), South Africa (3 [0.7%]), Colombia (3 [0.7%]), Spain (2 [0.5%]), and Germany (2 [0.5%]), with 1 (0.2%) strain each from Singapore, Greece, Poland, the United Kingdom, Argentina, Hong Kong, and Turkey.

Epidemiologic typing.

Panton-Valentine leukocidin (PVL) (lukF-PV and lukS-PV) screening was performed by using a multiplex real-time PCR (RT-PCR) approach as previously described (30). SCCmec types (I through VI) were characterized using a multiplex PCR strategy (32). Strains showing inconclusive SCCmec typing results were subjected to a secondary strategy proposed by Oliveira et al. (35). Typing of the agr operon (groups I through IV) was assessed using multiplex RT-PCR as previously described by Strommenger et al. (49).

Bacterial chromosomal DNA was digested with SmaI and subjected to pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE). PFGE types were assigned according to the origin of the isolates (United States, Europe [including Russia and Turkey], Latin America, the Asian-Pacific [APAC] region, and South Africa), followed by a capital letter (PFGE type) and a number (PFGE subtype). Gel pattern analysis was performed using the GelCompar II software (Applied Math, Kortrijk, Belgium), and the patterns obtained were compared to those of the major U.S. and international clones, which were provided by the Network on Antimicrobial Resistance in S. aureus (NARSA; www.narsa.net). Percent similarities were identified on a dendrogram derived by the unweighted-pair group method using arithmetic averages and based on Dice coefficients. Band position tolerance and optimization were set at 1.3 and 0.5%, respectively. Isolates showing similarity coefficient at ≥80% were considered genetically related (same PFGE type), while those with a similarity coefficient at ≥95% were assigned the same PFGE subtype (29).

All strains were subjected to spa typing (46). Clonal complexes (CCs) were assigned based on the spa typing results using the multilocus sequence typing (MLST) mapping database (http://spa.ridom.de/mlst) or peer-reviewed reports. Strains with new spa typing denominations and previously unknown MLST associations, but clustering within PFGE types containing strains with similar patterns of spa repeat sequences and known CC results, were assigned the same CCs. MLST was performed (36) for a given strain showing a spa type with an unknown MLST association and a unique PFGE pattern. See the supplemental material for additional information related to the strains and molecular testing results (including heterogeneous vancomycin-intermediate S. aureus [hVISA], SCCmec, PVL, agr, spa [Ridom and Kreiswirth nomenclatures]), MLST, and CCs generated during this study.

Antimicrobial susceptibility profile.

Isolates were tested for susceptibility by broth microdilution in cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton medium according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) recommendations (12). Quality assurance was performed by concurrent testing of CLSI-recommended (M100-S22) strains: Enterococcus faecalis ATCC 29212 and S. aureus ATCC 29213. Interpretation of MIC results was in accordance with published CLSI criteria (13).

Inducible clindamycin resistance was detected using the D-test disk diffusion method according to CLSI (13). Briefly, a 2-μg clindamycin disk was placed 15 mm from the edge of a 15-μg erythromycin disk. Following incubation, isolates that showed flattening of the clindamycin zone on the edge adjacent to the erythromycin disk were considered D-test positive. Screening for heterogeneous vancomycin-intermediate S. aureus (hVISA) was performed using the Etest (bioMérieux, Marcy l'Etoile, France) macromethod as previously described (30).

RESULTS

Epidemiologic typing.

MRSA strains will be referred to herein according to the CC and SCCmecA typing results. Therefore, CC5-MRSA-II indicates that a particular strain or group of strains are associated with CC5 and carried SCCmec type II. The most frequent clone identified in this study was CC5-MRSA-I/II/IV (56.0% [243/434]), followed by CC8-MRSA-IV (23.3% [101/434]) and CC239-MRSA-III (11.3% [49/434]), while another 10 CCs detected were each represented by <3.5% of the total strains included (Table 1). MRSA strains associated with CC5 (56.0%) originated mostly from the United States (CC5-MRSA-II/IV; 70.0% [170/243]), Asia (CC5-MRSA-II; 14.0% [34/243]), and Latin America (CC5-MRSA-I/II; 12.3% [30/243]). CC8 MRSA strains were most commonly observed in the United States (75.2% [76/101]) and Europe (18.8% [19/101]) (Table 1), while the third-most-observed MRSA lineage (CC239-MRSA-III) was more commonly noted in Asia (44.9% [22/49]) and Latin America (26.5% [13/49]), where these strains represented the second-most-common clone (Table 1).

Table 1.

Clonal distribution of MRSA isolates (unique strains) recovered from subjects enrolled in a phase IV pneumonia clinical trial for linezolid

| Clonal complex | No. (%) of strains |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| United States | Europea | Latin Americab | Asiac | Total | |

| CC5 | 170 (64.4) | 9 (16.4) | 30 (66.7) | 34 (50.7) | 243 (56.0) |

| CC5-MRSA-I | 0 (0.0) | 3 (5.5) | 13 (28.9) | 0 (0.0) | 16 (3.7) |

| CC5-MRSA-II | 159 (60.2) | 4 (7.3) | 17 (37.8) | 34 (50.7) | 214 (49.3) |

| CC5-MRSA-IV | 11 (4.2) | 2 (3.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 13 (3.0) |

| CC8-MRSA-IV | 76 (28.8) | 19 (34.5) | 1 (2.2) | 5 (7.5) | 101 (23.3) |

| CC239-MRSA-III | 4 (1.5) | 7 (12.7) | 13 (28.9) | 22 (32.8) | 49 (11.3)d |

| CC45-MRSA-II/III/IV | 7 (2.7)e | 6 (10.9)f | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.5)g | 14 (3.2) |

| CC22-MRSA-IV | 0 (0.0) | 10 (18.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 10 (2.3) |

| CC30-MRSA-II | 4 (1.5) | 1 (1.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (1.2) |

| CC59-MRSA-IV | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (4.5) | 4 (0.9) |

| CC398-MRSA-III/IV | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.8)f | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.5)g | 2 (0.5) |

| CC1-MRSA-IV | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) |

| CC9-MRSA-II | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.5) | 1 (0.2) |

| CC72-MRSA-IV | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) |

| CC80-MRSA-IV | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) |

| CC96-MRSA-III | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) |

| CC97-MRSA-IV | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) |

| Total | 264 (60.8) | 55 (12.7) | 45 (10.4) | 67 (15.4) | 434 (100.0) |

Includes isolates from Belgium, France, Germany, Greece, Poland, Portugal, Russia, Spain, Turkey, and the United Kingdom.

Includes isolates from Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, and Puerto Rico.

Includes isolates from Hong Kong, South Korea, Malaysia, Singapore, and Taiwan.

Includes three CC239-MRSA-III strains from South Africa.

MRSA strains carrying SCCmec type II.

MRSA strain carrying a SCCmec type IV.

MRSA strains carrying SCCmec type III.

The majority (64.4% [170/264]) of clinical trial strains collected from the United States were CC5-MRSA-II/IV, agr type 2 and PVL negative (Table 2). Among these strains, 159 and 11 carried SCCmec types II and IV, respectively. While most CC5-MRSA-II strains (69.2% [110/159]) clustered within a PFGE type (USA-B) with profiles similar to or indistinguishable from that of the USA100 strain, the other CC5-MRSA-II isolates were distributed among 14 clusters (PFGE types). All 11 CC5-MRSA-IV strains clustered within USA-N, which showed PFGE patterns similar to or indistinguishable from that of NRS387, a representative of USA800. The second major cluster detected in the United States was CC8-MRSA-IV (28.8% [76/264]), among which 73.7% (56/76 [21.2% of all U.S. strains]) (Table 2) were PVL positive and clustered within USA-A (USA300 pattern) (Table 2). CC8-MRSA-IV, which was PVL negative, from the United States grouped into nine PFGE types (six spa types), including isolates with PFGE patterns similar to USA500 (USA-Q) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Epidemiologic data of baseline MRSA isolates (unique strains) recovered during a phase IV pneumonia clinical trial for linezolid

| Region or country (no. tested) | No. (%) | SCCmec type | PVLa | agr type | PFGE | spa type(s) | CC no. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| APAC (67) | |||||||

| Hong Kong (1) | 1 (100.0) | III | − | 1 | ASI-J | 433 | 45 |

| South Korea (44) | 22 (50.0) | II | − | 2 | ASI-Ab | 232, 1095, 1478, 1479 | 5 |

| 3 (6.8) | II | − | 2 | ASI-B | 2 | 5 | |

| 2 (4.5) | II | − | 2 | ASI-C | 2, 1095 | 5 | |

| 5 (11.4) | IV | − | 1 | ASI-D | 451, 554 | 8 | |

| 1 (2.3) | II | − | 2 | ASI-E | 2 | 5 | |

| 1 (2.3) | III | − | 1 | ASI-G | 3 | 239 | |

| 8 (18.2) | III | − | 1 | ASI-I | 3 | 239 | |

| 1 (2.3) | II | − | 2 | ASI-M | 2 | 5 | |

| 1 (2.3) | II | − | 2 | ASI-N | 1095 | 5 | |

| Malaysia (6) | 1 (16.7) | II | − | 1 | ASI-F | 1152 | 8 |

| 5 (83.3) | III | − | 1 | ASI-I | 3 | 239 | |

| Singapore (1) | 1 (100.0) | III | − | 1 | ASI-I | 3 | 239 |

| Taiwan (15) | 4 (26.7) | II | − | 2 | ASI-A | 2, 14 | 5 |

| 4 (26.7) | III | − | 1 | ASI-G | 3 | 239 | |

| 1 (6.7) | III | − | 1 | ASI-H | 3 | 239 | |

| 1 (6.7) | III | − | 1 | ASI-I | 3 | 239 | |

| 2 (13.3) | IV | − | 1 | ASI-K | 143, 778 | 59 | |

| 1 (6.7) | IV | + | 1 | ASI-L | 776 | 59 | |

| 1 (13.3) | III | − | 1 | NTc | 539 | 398 | |

| 1 (13.3) | III | − | 1 | NT | 3 | 239 | |

| Europe (55) | |||||||

| Belgium (18) | 5 (27.8) | IV | − | 1 | EUR-Ad | 756, 1484 | 45 |

| 1 (5.5) | IV | − | 1 | EUR-Be | 382 | 22 | |

| 1 (5.5) | IV | − | 1 | EUR-Df | 1 | 8 | |

| 5 (27.8) | IV | − | 1 | EUR-Eg | 1, 4, 366 | 8 | |

| 4 (22.2) | II | − | 2 | EUR-Gb | 437 | 5 | |

| 1 (5.5) | IV | − | 2 | EUR-H | 2 | 5 | |

| 1 (5.5) | IV | − | 1 | NT | 1485 | 398 | |

| France (8) | 6 (75.0) | IV | − | 1 | EUR-D | 1 | 8 |

| 1 (12.5) | III | − | 1 | EUR-K | 351 | 239 | |

| 1 (12.5) | IV | − | 2 | EUR-M | 1480 | 5 | |

| Germany (2) | 1 (50.0) | IV | − | 1 | EUR-B | 382 | 22 |

| 1 (50.0) | IV | − | 1 | EUR-L | 15 | 45 | |

| Greece (1) | 1 (100.0) | IV | + | 3 | EUR-J | 70 | 80 |

| Poland (1) | 1 (100.0) | I | − | 2 | EUR-I | 388 | 5 |

| Portugal (8) | 7 (87.5) | IV | − | 1 | EUR-B | 382, 816, 1473 | 22 |

| 1 (12.5) | II | − | 3 | EUR-C | 16 | 30 | |

| Russia (13) | 3 (23.1) | IV | − | 1 | EUR-D | 1 | 8 |

| 4 (30.8) | IV | − | 1 | EUR-F | 1 | 8 | |

| 5 (38.5) | III | − | 1 | EUR-K | 351 | 239 | |

| 1 (7.7) | III | + | 3 | EUR-N | 999 | 96 | |

| Spain (2) | 2 (100.0) | I | − | 2 | EUR-I | 1481, 1488 | 5 |

| Turkey (1) | 1 (100.0) | III | − | 1 | EUR-K | 351 | 239 |

| United Kingdom (1) | 1 (100.0) | IV | − | 1 | EUR-B | 382 | 22 |

| South Africa (3) | 3 (100.0) | III | − | 1 | SA-A | 3 | 239 |

| North America (United States; 264) | 56 (21.2) | IV | + | 1 | USA-Ah | 1, 59, 245, 363, 1487 | 8 |

| 110 (41.7) | II | − | 2 | USA-Bb | See footnote i | 5 | |

| 17 (6.4) | II | − | 2 | USA-C | 2, 11, 24, 50, 230 | 5 | |

| 1 (0.4) | II | − | 2 | USA-D | 2 | 5 | |

| 5 (1.9) | II | − | 2 | USA-E | 2, 24, 29, 302 | 5 | |

| 10 (3.8) | II | − | 2 | USA-F | 2, 24, 58 | 5 | |

| 4 (1.5) | II | − | 2 | USA-G | 2, 11, 302 | 5 | |

| 1 (0.4) | IV | − | 1 | USA-H | 1 | 8 | |

| 2 (0.8) | II | − | 2 | USA-I | 2, 1475 | 5 | |

| 1 (0.4) | IV | − | 1 | USA-J | 1 | 8 | |

| 1 (0.4) | IV | − | 1 | USA-K | 363 | 8 | |

| 3 (1.1) | II | − | 2 | USA-L | 2 | 5 | |

| 1 (0.4) | II | − | 2 | USA-M | 303 | 5 | |

| 11 (4.2) | IV | − | 2 | USA-Nj | 2, 23, 24, 29, 203, 693 | 5 | |

| 1 (0.4) | II | − | 2 | USA-O | 24 | 5 | |

| 1 (0.4) | IV | − | 3 | USA-P | 175 | 1 | |

| 10 (3.8) | IV | − | 1 | USA-Qg | 1, 7 | 8 | |

| 1 (0.4) | IV | − | 1 | USA-R | 139 | 8 | |

| 4 (1.5) | III | − | 1 | USA-S | 3 | 239 | |

| 1 (0.4) | IV | − | 1 | USA-T | 1 | 8 | |

| 1 (0.4) | II | − | 2 | USA-U | 12 | 5 | |

| 2 (0.8) | IV | − | 1 | USA-V | 1 | 8 | |

| 1 (0.4) | II | − | 2 | USA-W | 1070 | 5 | |

| 7 (2.7) | II | − | 1/NT | USA-Xd | 10, 15, 62, 1472 | 45 | |

| 4 (1.5) | II | − | 3 | USA-Yk | 16, 33 | 30 | |

| 1 (0.4) | IV | − | 1 | USA-Z | 1 | 8 | |

| 1 (0.4) | II | − | 2 | USA-AA | 337 | 5 | |

| 1 (0.4) | II | − | 2 | USA-AB | 11 | 5 | |

| 1 (0.4) | II | − | 2 | USA-AC | 11 | 5 | |

| 1 (0.4) | IV | − | 1 | USA-AEl | 206 | 59 | |

| 1 (0.4) | IV | − | 1 | USA-AFm | 1482 | 72 | |

| 2 (0.8) | IV | − | 1 | USA-AG | 68, 1486 | 8 | |

| Latin America (45) | |||||||

| Argentina (1) | 1 (100.0) | I | − | 2 | LAT-D | 58 | 5 |

| Brazil (18) | 2 (11.0) | II | − | 2 | LAT-B | 2 | 5 |

| 1 (5.5) | I | − | 2 | LAT-E | 2 | 5 | |

| 5 (27.8) | III | − | 1 | LAT-G | 3 | 239 | |

| 3 (16.7) | III | − | 1 | LAT-H | 3 | 239 | |

| 2 (11.1) | III | − | 1 | LAT-I | 3 | 239 | |

| 2 (11.1) | III | − | 1 | LAT-J | 3 | 239 | |

| 1 (5.5) | III | − | 1 | LAT-K | 3 | 239 | |

| 1 (5.5) | IV | − | 1 | LAT-M | 92 | 97 | |

| 1 (5.5) | II | − | 2 | LAT-N | 2 | 5 | |

| Chile (8) | 8 (100.0) | I | − | 2 | LAT-Cn | 442 | 5 |

| Colombia (3) | 3 (100.0) | I | − | 2 | LAT-C | 442 | 5 |

| Mexico (10) | 8 (80.0) | II | − | 2 | LAT-A | 58, 1474 | 5 |

| 1 (10.0) | II | − | 2 | LAT-B | 58 | 5 | |

| 1 (10.0) | II | − | 2 | LAT-N | 29 | 5 | |

| Puerto Rico (5) | 3 (60.0) | II | − | 2 | LAT-B | 2 | 5 |

| 1 (20.0) | IV | + | 1 | LAT-Fh | 1 | 8 | |

| 1 (20.0) | II | − | 2 | LAT-L | 2 | 5 |

PVL, Panton-Valentine leukocidin. +, present; −, absent.

PFGE type indistinguishable from or similar to that of USA100.

NT, nontypeable.

PFGE type indistinguishable from or similar to that of USA600.

PFGE type indistinguishable from or similar to that of EMRSA-15.

PFGE type indistinguishable from or similar to that of EMRSA-6.

PFGE type indistinguishable from or similar to that of USA500.

PFGE type indistinguishable from or similar to that of USA300.

Strains represented by spa types 2, 23, 24, 25, 29, 47, 50, 58, 65, 203, 230, 268, 300, 336, 442, 487, 841, 1206, 1476, 1477, and 1483.

PFGE type indistinguishable from or similar to that of USA800.

PFGE type indistinguishable from or similar to that of USA200.

PFGE type indistinguishable from or similar to that of USA1000.

PFGE type indistinguishable from or similar to that of USA700.

PFGE type indistinguishable from or similar to that of Cordobes/Chilean.

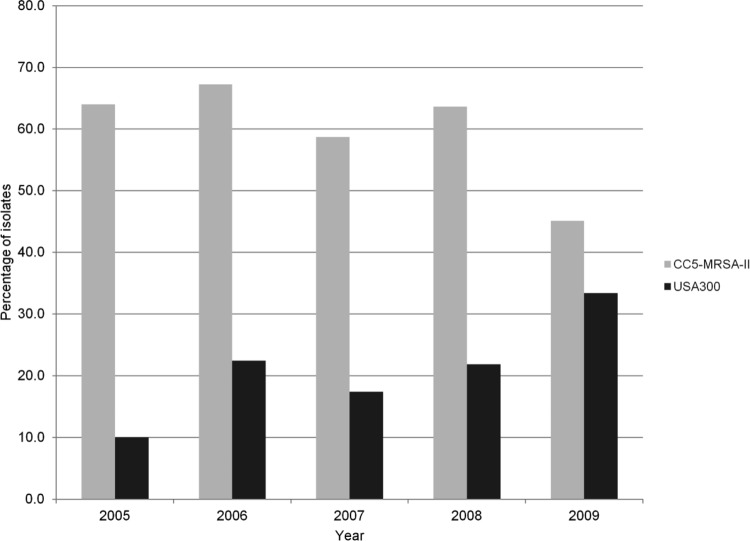

Figure 1 displays the percentages of CC8-MRSA-IV (USA300) compared to CC5-MRSA-II strains (agr type 2, USA100 and associated ancestors) recovered during each year of the study period. Only one and three strains included in the study were collected during 2004 and 2010, respectively (data not shown). Thus, these 2-year periods were excluded from this analysis. A total of 64.0% (32/50) of the USA100 strains were recovered from subjects included in 2005 versus 10.0% (5/50) of USA300 strains. However, 45.1% (23/51) of USA100 strains were observed in 2009 against an increasing 33.3% (17/51) of USA300 MRSA isolates (P = 0.0049; odds ratio [OR] = 0.21 [range, 0.06 to 0.73]).

Fig 1.

Proportion of unique CC8-MRSA-IV (PVL-positive; USA300) and CC5-MRSA-II strains recovered from subjects enrolled in the United States during the study period. CC8-MRSA-IV strains were agr type 1 and PVL positive and clustered within the PFGE USA-A group (USA300). CC5-MRSA-II strains were agr type 2 and PVL negative.

A greater genetic diversity was observed among strains from European countries, including Russia and Turkey. Isolates were mostly CC8-MRSA-IV (34.5% [19/55]) or CC22-MRSA-IV (18.2% [10/55]) (Tables 1 and 2). CC8-MRSA-IV strains clustered within three PFGE types (EUR-D, -E, and -F), among which EUR-D (from Belgium, France, and Russia) and -E (all from Belgium) were also similar to the EMRSA-6 and USA500 patterns, respectively (Table 2). All CC22-MRSA-IV strains clustered within EUR-B, also known as EMRSA-15, and originated from Portugal (70.0% [7/10]), Belgium (10.0% [1/10]), Germany (10.0% [1/10]), and the United Kingdom (10.0% [1/10]). MRSA isolates from Europe associated with CC5 possessed SCCmec types I, II, or IV. CC5-MRSA-I isolates grouped within EUR-I and originated from Poland and Spain (Table 2). Four CC5-MRSA-II strains from Belgium showed a unique PFGE pattern (EUR-G; spa type 437), which matched that of NRS382 (USA100), while one CC5-MRSA-IV strain each from Belgium (EUR-H; spa type 2) and France (EUR-M; spa type 1480) was detected (Table 2). Other less prevalent lineages noted in Europe are as follows: CC398-MRSA-IV (one strain from Belgium), CC239-MRSA-III (one strain each from France and Turkey and four isolates from Russia), CC80-MRSA-IV (one strain from Greece), CC96-MRSA-III (one strain from Russia), CC45-MRSA-IV (five strains from Belgium and one from Germany), and CC30-MRSA-II (one strain from Portugal) (Table 1).

The most prevalent clone found in Latin America was CC5-MRSA-I/II (66.7% [30/45]), followed by CC239-MRSA-III (28.9% [13/45]) (Table 1). CC5-MRSA-I isolates were represented by the LAT-C (84.6% [11/13]), LAT-D (7.7% [1/13]), and LAT-E (7.7% [1/13]) PFGE types, among which LAT-C showed profiles that matched that from a representative of the Cordobes/Chilean clone (Tables 1 and 2). LAT-C strains originated from Chile (72.7% [8/11]) and Colombia (27.3% [3/11]). Those strains associated with CC5-MRSA-II clustered within LAT-A (47.0% [8/17]), LAT-B (35.3% [6/17]), LAT-L (5.9% [1/17]), and LAT-N (11.8% [2/17]). All LAT-A strains were collected from Mexico, while LAT-B MRSA isolates were from Puerto Rico (50.0% [3/6]), Brazil (33.3% [2/6]), or Mexico (16.7% [1/6]). All CC239-MRSA-III strains (28.9% [13/45]) observed from Latin America originated from a single country (Brazil). Other minor clones were CC97-MRSA-IV (2.2% [1/45]) and CC8-MRSA-IV (2.2% [1/45]). The latter strain originated from Puerto Rico and demonstrated molecular and PFGE profiles (LAT-F) similar to those of the USA300 clone (Table 2).

Overall, strains from the APAC region were CC5-MRSA-II (50.7% [34/67]) or CC239-MRSA-III (32.8% [22/67]), PVL negative, and agr types 2 and 1, respectively (Tables 1 and 2). Five and three isolates were CC8-MRSA-IV and CC59-MRSA-IV, which were from South Korea (ASI-D) and Taiwan (ASI-K and -L), respectively (Table 3). One strain from Taiwan was CC398-MRSA-III, agr type 1, and PVL negative, while a single strain collected from Hong Kong was CC45-MRSA-III, agr type 1, and PVL negative (Table 2). Regarding PFGE patterns, the majority of APAC MRSA strains clustered within ASI-A (26/67 [38.8%]) or -I (15/67 [22.4%]). Isolates showing the ASI-A PFGE type were CC5-MRSA-II, spa type 2 or related types, and agr type 2, also known as the New York/Japan clone, whereas those belonging to ASI-I were CC239-MRSA-III, spa type 3, and agr type 1 (Hungarian/Brazilian clone) (Table 2). Among ASI-A strains, the vast majority (22/26 [84.6%]) originated from four hospitals in South Korea, while the remaining four strains were from two hospitals in Taiwan (4/26 [15.4%]). In contrast, strains clustering within ASI-I (10 subtypes) were from South Korea (8/15 [53.3%]), Malaysia (5/15 [33.3%]), Singapore (1/15 [6.7%]), and Taiwan (1/15 [6.7%]) (Table 2).

Table 3.

Antimicrobial activity and susceptibility results of selected drugs tested against baseline MRSA clinical isolates (unique strains) by clonal complex recovered during a phase IV pneumonia clinical trial for linezolid

| Antimicrobial agent | MIC50/MIC90, μg/ml (% susceptible) bya: |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CC |

USA clone |

||||||

| CC5 (n = 243) | CC8 (n = 101) | CC239 (n = 49) | CC45 (n = 14) | CC22 (n = 10) | USA300 (n = 56) | USA100 (n = 110) | |

| Linezolid | 2/4 (100.0) | 2/2 (100.0) | 2/2 (100.0) | 2/4 (100.0) | 2/2 (100.0) | 2/2 (100.0) | 2/4 (100.0) |

| Vancomycin | 1/1 (99.6) | 1/1 (100.0) | 1/1 (100.0) | 1/2 (100.0) | 1/1 (100.0) | 1/1 (100.0) | 1/1 (100.0) |

| Teicoplanin | 0.5/2 (100.0) | 0.5/1 (100.0) | 1/2 (100.0) | 0.5/2 (100.0) | 0.25/0.5 (100.0) | 0.5/1 (100.0) | 0.5/1 (100.0) |

| Daptomycin | 0.5/1 (100.0) | 0.5/1 (100.0) | 0.5/1 (100.0) | 0.5/1 (100.0) | 0.25/0.5 (100.0) | 1/1 (100.0) | 0.5/1 (100.0) |

| Erythromycin | >64/>64 (1.2) | 64/>64 (8.9) | >64/>64 (0.0) | 0.5/>64 (57.1) | >64/>64 (40.0) | 64/>64 (1.8) | >64/>64 (0.0) |

| Clindamycin | >64/>64 (4.5)b | 0.25/>64 (61.4)c | >64/>64 (0.0)d | 0.12/>64 (57.1)e | 0.12/>64 (40.0)f | 0.25/>64 (85.7)g | >64/>64 (0.0)h |

| Gatifloxacin | 8/>16 (4.9) | 2/16 (28.7) | 4/16 (0.0) | 4/8 (7.1) | 8/16 (0.0) | 2/8 (32.1) | 8/>16 (2.7) |

| Tetracycline | 0.5/64 (87.3) | 0.25/1 (93.1) | 32/>64 (2.0) | 0.25/1 (92.9) | 0.25/0.25 (100.0) | 0.25/0.5 (98.2) | 0.5/1 (98.2) |

| Q/Di | 0.5/1 (99.6) | 0.25/0.5 (99.0) | 0.5/0.5 (100.0) | 0.25/0.5 (100.0) | 0.25/0.25 (100.0) | 0.5/0.5 (100.0) | 0.5/0.5 (100.0) |

| TMP/SMXj | 0.12/0.25 (98.0) | 0.06/0.5 (90.1) | 16/>32 (18.4) | 0.12/0.5 (92.9) | 0.06/0.06 (100.0) | 0.06/0.12 (100.0) | 0.12/0.25 (95.5) |

MICs were interpreted according to the M100-S22 document (13).

Nonsusceptible strains are represented by 73.0% and 22.5% of constitutive and inducible resistance phenotypes, respectively.

Nonsusceptible strains are represented by 32.6% and 6.0% of constitutive and inducible resistance phenotypes, respectively.

Nonsusceptible strains are represented by 81.6% and 18.4% of constitutive and inducible resistance phenotypes, respectively.

Nonsusceptible strains are represented by 42.9% of constitutive resistance phenotypes.

Nonsusceptible strains are represented by 20.0% and 40.0% of constitutive and inducible resistance phenotypes, respectively.

Nonsusceptible strains are represented by 10.7% and 3.6% of constitutive and inducible resistance phenotypes, respectively.

Nonsusceptible strains are represented by 66.4% and 33.6% of constitutive and inducible resistance phenotypes, respectively.

Q/D, quinupristin-dalfopristin.

TMP/SMX, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.

Antimicrobial susceptibility profiles.

Table 3 displays the activities and susceptibility profiles of selected agents tested against MRSA strains according to lineage. Overall, linezolid (MIC50, 2 μg/ml), vancomycin (MIC50, 1 μg/ml), teicoplanin (MIC50, 0.5 μg/ml), and daptomycin (MIC50, 0.5 μg/ml) showed stable MIC50 results when evaluated against each major CC. Exceptions were observed when teicoplanin was tested against the CC239 and CC22 strains, which showed MIC50 values 2-fold higher (MIC50, 1 μg/ml) and 2-fold lower (MIC50, 0.25 μg/ml) than those of the other CC isolates, respectively. In addition, CC22 strains exhibited daptomycin MIC values (MIC50/90, 0.25/0.5 μg/ml) 2-fold lower than those of other tested CC strains (MIC50/90, 0.5/1 μg/ml). One MRSA strain from the United States exhibited a nonsusceptible phenotype to vancomycin (MIC, 4 μg/ml; intermediate) and clustered within USA-N (USA800). Tetracycline (MIC50, 0.25 μg/ml [≥92.9% susceptible]) was active when tested against CC8, CC45, and CC22 strains, while 98.0% of CC239 MRSA isolates were tetracycline resistant. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP/SMX) showed potent activity (MIC50/90, 0.06 to 0.12/0.06 to 0.5 μg/ml [≥90.1% susceptible]) against all major CC groups, except for CC239 strains (MIC50/90, 16/>32 μg/ml [18.4% susceptible]).

USA300 strains were susceptible to most antimicrobial agents tested (≥98.2% susceptible), except for erythromycin (1.8% susceptible) and gatifloxacin (32.1% susceptible), which were inactive. Clindamycin demonstrated a potent MIC50 result (0.25 μg/ml) when tested against MRSA belonging to the USA300 lineage. However, 10.7 and 3.6% of isolates exhibited, respectively, constitutive and inducible resistance phenotypes for clindamycin, resulting in a suboptimal overall susceptibility result (85.7% susceptible) and an elevated MIC90 result (>64 μg/ml). CC5 isolates and their regional U.S. subset (USA100) showed a similar susceptibility profile, except for tetracycline. When tested against all CC5 strains, tetracycline demonstrated MIC90 results (MIC50/90, 0.5/64 μg/ml) higher than those of the USA100 subset (MIC50/90, 0.5/1 μg/ml), which translated into slightly different susceptibility profiles (87.3 versus 98.2%, respectively). Among tetracycline-resistant CC5 strains, 27 of 31 (87.1%) originated from four hospitals in South Korea, and 19 of 27 (70.4%) belonged to a unique PFGE type (ASI-A; data not shown). Other tetracycline-resistant CC5 isolates were from the United States (three strains) or Belgium (one strain).

Overall, 14.5% (63/434) isolates were characterized as hVISA, according to the employed method. The countries with the highest hVISA rates (countries with ≥10 strains) were as follows: South Korea (61.4% [27/44]), Brazil (40.4% [8/18]), Russia (23.1% [3/13]), Mexico (20.0% [2/10]), Taiwan (13.3% [2/15]), and the United States (5.3% [14/264]) (data not shown). The occurrences of hVISA strains were higher within CC30-MRSA-II strains (40.0% [2/5]), followed by CC239-MRSA-III (22.4%; [11/49]), CC45-MRSA-II/III (21.4% [3/14]), CC5-MRSA-I/II/IV (16.5% [40/243]), and CC8-MRSA-IV (6.9% [7/101]) strains. Among CC5 hVISA strains, the majority were collected from South Korea (65.0% [26/40]) and belonged mostly (76.9% [20/26]) to a unique PFGE type (ASI-A). Two CC30 hVISA isolates were recovered from the United States and Portugal (one each), while CC45 hVISA strains originated from three U.S. hospitals and clustered within USA600 (USA-X). hVISA strains associated with CC239-MRSA-III were collected from scattered countries, such as Brazil (six strains), Russia (three strains), Malaysia (one strain), and Turkey (one strain). Differences in the susceptibility profiles between hVISA and non-hVISA strains were not observed.

DISCUSSION

The majority (56.0%) of the microbiologically evaluable baseline MRSA isolates responsible for NP and included in this study belonged to CC5-MRSA-I/II/IV. However, when analyzing the prevalence of MRSA lineages according to the geographic regions, two major clones predominated in each area. In the APAC and Latin America regions, isolates associated with CC5-MRSA-I/II prevailed, followed by CC239-MRSA-III. Isolates responsible for NP among U.S. hospitals were mostly associated with CC5-MRSA-II/IV and CC8-MRSA-IV, while in Europe, a greater clonal diversity was observed and CC8-MRSA-IV predominated, followed by similar occurrences of CC22-MRSA-IV and CC5-MRSA-I/II/IV. Overall, these lineages are comprised of the so-called pandemic clones, such as ST239-MRSA-III (Brazilian/Hungarian), ST5-MRSA-II (New York/Japan), ST5-MRSA-IV (pediatric), ST22-MRSA-IV (UK-EMRSA-15) and ST8-MRSA-IV (USA300, USA500, and UK-EMRSA-2 and -6) (18, 33, 36, 41).

In the United States, ST5-MRSA-II (USA100) has been the most common nosocomial MRSA clone, which has been implicated for approximately 60 to 68% of hospital-onset or hospital-acquired infections (HA-MRSA) (10, 27). The rate (60.2% [159/264]) of CC5-MRSA-II (USA100) strains observed in this study corroborates those previously reported and confirmed USA100 as an important cause of HA-MRSA infections. However, studies reported that USA300 strains are now responsible for 15.7 to 20.0% of the invasive HA-MRSA infections in the United States (10, 22, 27). An overall USA300 prevalence rate (21.2%) similar to those reported previously was observed in this study. In addition, the proportion of USA300 strains appears to have increased slightly throughout the study period (Fig. 1). Overall, rates of USA300 were 10.0 to 22.4% during 2005 to 2008, while CC5-MRSA-II represented 58.7 to 67.2% of strains included. In 2009, USA300 and CC5-MRSA-II strains comprised 33.3 and 45.1% of all isolates, respectively. These results support previous data indicating that the proportion of infection cases caused by USA300 has increased and that it may be slowly replacing the traditional HA-MRSA strains (31, 39). However, this piece of data needs to be analyzed carefully, since the inclusion of the isolates in this pneumonia trial did not follow prevalence mode design criteria.

Grundmann et al. (19) recently reported the detection of genetic diversity among MRSA strains causing invasive infections in Europe, with CC5 (30.3%) being the most prevalent lineage, followed by CC22 (16.9%), CC8 (15.3%), and CC239 (5.0%). Changes within the MRSA population have been well documented in European countries, such as Germany (2), Ireland and Spain (38, 47), and Portugal (1, 4). Additional reports have described alterations in the MRSA epidemiology among other European countries (6, 9, 14, 16). The results reported here corroborate those reported by Grundmann et al. (19), who showed a greater genetic diversity and similar distribution of MRSA CCs. In addition, the results described here and elsewhere indicate that previously prevalent clones, such as ST247-MRSA-I (Iberian; CC8), ST228-MRSA-I (Southern Germany; CC5), ST239-MRSA-III (CC239; Brazilian/Hungarian), and ST45-MRSA-IV (CC45; Berlin, Germany), have decreased occurrences or have no longer been detected (15).

In contrast, Alp et al. (3) described the persistence of ST239-MRSA-III among eight university hospitals in Turkey over a 10-year period. Previous reports have also described a significant dominance (≥80.0%) of ST239-MRSA-III within Russian hospitals (5, 52, 54). Interestingly, this study detected a higher prevalence (53.8%) of CC8-MRSA-IV causing NP in Russia, while ST239-MRSA-III represented 38.5% of strains from this region. We are unaware of any previous report describing this clonal alteration in the HA-MRSA strain population in Russia, except for an earlier publication reporting that 80.0% of the MRSA strains causing skin and skin-structure infections during a phase IV clinical trial in this country were CC8-MRSA-IV (30), although a higher CC8-MRSA-IV rate might be expected among strains responsible for skin infections. Still in Europe, one strain belonging to a livestock-associated clone (spa type 1485/ST398) was collected from Belgium and one CC80-MRSA-IV strain (spa type 70; PVL positive) was noted in Greece. The latter has been implicated as an important CA-MRSA clone in Europe, but it has also been responsible for documented HA-MRSA infections (26).

CC5-MRSA-I, CC5-MRSA-II, and CC239-MRSA-III predominated among Latin American countries and represented 95.6% of all strains. CC239-MRSA-III was the predominant clone found in this region, but recent investigations demonstrated that CC239-MRSA-III has been partially replaced by the Cordobes/Chilean (CC5-MRSA-I) and New York/Japan (CC5-MRSA-II) clones (30, 42). However, CC239-MRSA-III and CC5-MRSA-I were detected equally in the South America, while CC5-MRSA-II was most frequently observed in Mexico. Moreover, the latter has been the predominant clone in Mexico after 2002, when this lineage displaced ST30-MRSA-IV (30). More recently, the CC8-MRSA-IV (USA300) clone has also emerged in several South American countries (30, 40, 42). One USA300 strain (PVL-positive) collected from Puerto Rico was observed here.

Among those MRSA strains originating from the APAC region, the CC5-MRSA-II and CC239-MRSA-III clones represented 83.5% of all strains included. Previous investigations have demonstrated the predominance of these clones in China (28), Malaysia (17), and other Asian countries (23). Surprisingly, a great proportion of hVISA strains detected by the method employed originated from South Korea (27/63 [42.9%]), and 61.4% of the MRSA strains from this country were considered hVISA. In addition, the vast majority (26/27 [96.3%]) of these hVISA strains were CC5-MRSA-II. An elevated hVISA rate (37.7%) has been previously reported by Park et al. (37) among isolates responsible for bacteremia in a hospital in South Korea, and several studies also reported that a greater number of hVISA strains were associated with CC5-MRSA-II (11, 37, 44, 48). The clinical significance of hVISA remains controversial (37, 44), but the overall rate of hVISA strains (14.5%) observed in this study appears elevated and mostly driven by a high rate noted in South Korea due to the dissemination of genetically related strains (PFGE, ASI-A). However, the hVISA-positive results obtained here were not confirmed by a second Etest macromethod testing result or population analysis profile-area under the curve (PAP-AUC). Some key phenotypic characteristics were observed according to the MRSA clonal lineage. Most notably, CC239-MRSA-III strains were resistant to erythromycin, clindamycin, gatifloxacin, tetracycline, and TMP/SMX, which has been a characteristic profile observed among isolates belonging to this clone (4). Although USA300 strains were previously described as susceptible to fluoroquinolones and clindamycin (29), fluoroquinolone (gatifloxacin) resistance has become commonplace among these strains (29, 30, 50) and was confirmed here (67.9% resistance). In contrast, clindamycin resistance remains uncommon among USA300 strains (27, 30). However, this study (14.3% resistance) and results from previous reports suggest that clindamycin resistance may be emerging among USA300 strains (27, 50).

It is important to mention that some countries, such as Hong Kong, Singapore, Germany, Greece, Poland, Spain, Turkey, the United Kingdom, South Africa, Argentina, and Colombia, contributed limited numbers of strains (<5 isolates) to this clinical trial study, which may compromise some epidemiological conclusions and/or comparison with other investigations. However, this study provides some insights regarding the MRSA population responsible for NP in most evaluated regions. In summary, the data documented a clear dominance of the CC5 lineage and confirmed an increased prevalence of USA300 strains causing NP in the United States. In addition, higher fluoroquinolone (67.9%) and clindamycin (14.3%) resistance rates (inducible and constitutive) were observed among USA300 strains. Moreover, a shift in the MRSA population was observed in Russia, with CC8-MRSA-IV replacing CC239-MRSA-III, and a high prevalence of hVISA strains was observed in the APAC region, especially South Korea.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the following staff members at JMI Laboratories (North Liberty, IA) for technical support and manuscript assistance: S. Benning, M. Castanheira, A. Costello, S. Farrell, and P. R. Rhomberg. We also thank Herminia de Lencastre and Keiichi Hiramatsu for providing S. aureus strains HDE288 and WIS, respectively, used in this study as positive controls (SCCmec types V and VI) during the SCCmec typing procedures.

This study was sponsored by the Pfizer, Inc., Specialty Care Business Unit, Collegeville, PA. JMI Laboratories, Inc. (R.E.M., L.M.D., D.J.F., and R.N.J.) received research and educational grants in 2009 to 2011 from Achaogen, Aires, American Proficiency Institute (API), Anacor, Astellas, AstraZeneca, Bayer, bioMérieux, Cempra, Cerexa, Cosmo Technologies, Contrafect, Cubist, Daiichi, Dipexium, Enanta, Furiex, GlaxoSmithKline, Johnson & Johnson (Ortho McNeil), LegoChem Biosciences Inc., Meiji Seika Kaisha, Merck, Nabriva, Novartis, Paratek, Pfizer (Wyeth), PPD Therapeutics, Premier Research Group, Rempex, Rib-X Pharmaceuticals, Seachaid, Shionogi, Shionogi USA, the Medicines Co., Theravance, ThermoFisher, TREK Diagnostics, Vertex Pharmaceuticals, and some other corporations.

Some JMI Laboratories employees are advisors and/or consultants for Astellas, Cubist, Pfizer, Cempra, Cerexa-Forest, J&J, and Theravance. D.S.S. and B.S. have no potential conflicts of interest to declare.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 12 September 2012

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jcm.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aires-de-Sousa M, Correia B, de Lencastre H. 2008. Changing patterns in frequency of recovery of five methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clones in Portuguese hospitals: surveillance over a 16-year period. J. Clin. Microbiol. 46:2912–2917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Albrecht N, Jatzwauk L, Slickers P, Ehricht R, Monecke S. 2011. Clonal replacement of epidemic methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains in a German university hospital over a period of eleven years. PLoS One 6:e28189 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0028189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alp E, et al. 2009. MRSA genotypes in Turkey: persistence over 10 years of a single clone of ST239. J. Infect. 58:433–438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amorim ML, et al. 2002. Clonal and antibiotic resistance profiles of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) from a Portuguese hospital over time. Microb. Drug Resist. 8:301–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baranovich T, et al. 2010. Molecular characterization and susceptibility of methicillin-resistant and methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus isolates from hospitals and the community in Vladivostok, Russia. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 16:575–582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blanc DS, et al. 2007. Changing molecular epidemiology of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in a small geographic area over an eight-year period. J. Clin. Microbiol. 45:3729–3736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boucher HW, Corey GR. 2008. Epidemiology of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Clin. Infect. Dis. 46(Suppl 5:S344–S349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burton DC, Edwards JR, Horan TC, Jernigan JA, Fridkin SK. 2009. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus central line-associated bloodstream infections in US intensive care units, 1997–2007. JAMA 301:727–736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Campanile F, Bongiorno D, Borbone S, Stefani S. 2009. Hospital-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Italy. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 8:22 doi:10.1186/1476-0711-8-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chua T, et al. 2008. Molecular epidemiology of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bloodstream isolates in urban Detroit. J. Clin. Microbiol. 46:2345–2352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chung G, et al. 2010. Nationwide surveillance study of vancomycin intermediate Staphylococcus aureus strains in Korean hospitals from 2001 to 2006. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 20:637–642 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute 2012. M07-–A9. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically: approved standard, 9th ed. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; Wayne, PA [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute 2012. M100-–S22. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing: 22nd informational supplement. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; Wayne, PA [Google Scholar]

- 14.Conceicao T, et al. 2007. Replacement of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clones in Hungary over time: a 10-year surveillance study. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 13:971–979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cookson BD, et al. 2007. Evaluation of molecular typing methods in characterizing a European collection of epidemic methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains: the HARMONY collection. J. Clin. Microbiol. 45:1830–1837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ellington MJ, et al. 2010. Decline of EMRSA-16 amongst methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus causing bacteraemias in the UK between 2001 and 2007. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 65:446–448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ghaznavi-Rad E, et al. 2010. Predominance and emergence of clones of hospital-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Malaysia. J. Clin. Microbiol. 48:867–872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gomes AR, Westh H, de Lencastre H. 2006. Origins and evolution of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clonal lineages. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:3237–3244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grundmann H, et al. 2010. Geographic distribution of Staphylococcus aureus causing invasive infections in Europe: a molecular-epidemiological analysis. PLoS Med. 7:e1000215 doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hidron AI, et al. 2008. NHSN annual update: antimicrobial-resistant pathogens associated with healthcare-associated infections: annual summary of data reported to the National Healthcare Safety Network at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2006–2007. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 29:996–1011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kallen AJ, et al. 2010. Health care-associated invasive MRSA infections, 2005–2008. JAMA 304:641–648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klevens RM, et al. 2007. Invasive methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in the United States. JAMA 298:1763–1771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ko KS, et al. 2005. Distribution of major genotypes among methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clones in Asian countries. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:421–426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kock R, et al. 2010. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA): burden of disease and control challenges in Europe. Euro Surveill. 15:19688 http://www.eurosurveillance.org/ViewArticle.aspx?ArticleId=19688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kollef MH, et al. 2011. Epidemiology, microbiology and outcomes of healthcare-associated and community-acquired bacteremia: a multicenter cohort study. J. Infect. 62:130–135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Larsen AR, et al. 2008. Epidemiology of European community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clonal complex 80 type IV strains isolated in Denmark from 1993 to 2004. J. Clin. Microbiol. 46:62–68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Limbago B, et al. 2009. Characterization of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates collected in 2005 and 2006 from patients with invasive disease: a population-based analysis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 47:1344–1351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu Y, et al. 2009. Molecular evidence for spread of two major methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clones with a unique geographic distribution in Chinese hospitals. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:512–518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McDougal LK, et al. 2003. Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis typing of oxacillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates from the United States: establishing a national database. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:5113–5120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mendes RE, et al. 2010. Characterization of baseline methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates recovered from phase IV clinical trial for linezolid. J. Clin. Microbiol. 48:568–574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mera RM, et al. 2011. Increasing role of Staphylococcus aureus and community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in the United States: a 10-year trend of replacement and expansion. Microb. Drug Resist. 17:321–328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Milheirico C, Oliveira DC, de Lencastre H. 2007. Update to the multiplex PCR strategy for assignment of mec element types in Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:3374–3377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Monecke S, et al. 2011. A field guide to pandemic, epidemic and sporadic clones of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. PLoS One 6:e17936 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0017936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance (NNIS) System Report data summary from January 1992 through June 2004, issued October 2004. 2004. Am. J. Infect. Control 32:470–485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oliveira DC, Milheirico C, Vinga S, de Lencastre H. 2006. Assessment of allelic variation in the ccrAB locus in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clones. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 58:23–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Oliveira DC, Tomasz A, de Lencastre H. 2001. The evolution of pandemic clones of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: identification of two ancestral genetic backgrounds and the associated mec elements. Microb. Drug Resist. 7:349–361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Park KH, et al. 2012. Comparison of the clinical features, bacterial genotypes and outcomes of patients with bacteraemia due to heteroresistant vancomycin-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus and vancomycin-susceptible S. aureus. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 67:1843–1849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Perez-Roth E, Lorenzo-Diaz F, Batista N, Moreno A, Mendez-Alvarez S. 2004. Tracking methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clones during a 5-year period (1998 to 2002) in a Spanish hospital. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:4649–4656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Popovich KJ, Weinstein RA, Hota B. 2008. Are community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) strains replacing traditional nosocomial MRSA strains? Clin. Infect. Dis. 46:787–794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reyes J, et al. 2009. Dissemination of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus USA300 sequence type 8 lineage in Latin America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 49:1861–1867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Robinson DA, Enright MC. 2004. Multilocus sequence typing and the evolution of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 10:92–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rodriguez-Noriega E, et al. 2010. Evolution of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clones in Latin America. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 14:e560–e566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rosenthal VD, et al. 2012. International Nosocomial Infection Control Consortium (INICC) report, data summary of 36 countries, for 2004–2009. Am. J. Infect. Control 40:396–407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Satola SW, et al. 2011. Clinical and laboratory characteristics of invasive infections due to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates demonstrating a vancomycin MIC of 2 micrograms per milliliter: lack of effect of heteroresistant vancomycin-intermediate S. aureus phenotype. J. Clin. Microbiol. 49:1583–1587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Seybold U, et al. 2006. Emergence of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus USA300 genotype as a major cause of health care-associated blood stream infections. Clin. Infect. Dis. 42:647–656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shopsin B, et al. 1999. Evaluation of protein A gene polymorphic region DNA sequencing for typing of Staphylococcus aureus strains. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:3556–3563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shore AC, et al. 2010. Enhanced discrimination of highly clonal ST22-methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus IV isolates achieved by combining spa, dru, and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis typing data. J. Clin. Microbiol. 48:1839–1852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Song JH, et al. 2004. Emergence in Asian countries of Staphylococcus aureus with reduced susceptibility to vancomycin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:4926–4928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Strommenger B, Cuny C, Werner G, Witte W. 2004. Obvious lack of association between dynamics of epidemic methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in central Europe and agr specificity groups. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 23:15–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tenover FC, et al. 2012. Characterization of nasal and blood culture isolates of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus from patients in United States hospitals. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56:1324–1330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tracy LA, et al. 2011. Staphylococcus aureus infections in US veterans, Maryland, USA, 1999–2008. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 17:441–448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vorobieva V, et al. 2008. Clinical isolates of Staphylococcus aureus from the Arkhangelsk region, Russia: antimicrobial susceptibility, molecular epidemiology, and distribution of Panton-Valentine leukocidin genes. APMIS 116:877–887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wunderink RG, et al. 2012. Linezolid in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus nosocomial pneumonia: a randomized, controlled study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 54:621–629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yamamoto T, et al. 2012. Comparative genomics and drug resistance of a geographic variant of ST239 methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus emerged in Russia. PLoS One 7:e29187 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0029187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.