Abstract

Infections caused by multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii constitute a major life-threatening problem worldwide, and early adequate antibiotic therapy is decisive for success. For these reasons, rapid detection of antibiotic susceptibility in this pathogen is a clinical challenge. Two variants of the Micromax kit were evaluated for a rapid detection in situ of susceptibility or resistance to meropenem or ciprofloxacin, separately, in 322 clinical isolates. Release of the nucleoid is the criterion of susceptibility to the beta-lactams (carbapenems), whereas diffusion of DNA fragments emerging from the nucleoid characterizes the quinolone activity. All the susceptible and resistant strains were correctly categorized in 100 min according to the MIC results and CLSI criteria. Thus, our technology is a promising tool for rapid identification of carbapenem and quinolone resistance of A. baumannii strains in hospital settings.

INTRODUCTION

One of the most formidable challenges in practical medicine is the progressive worldwide increase of multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii strains. This opportunistic pathogen shows an alarming ability for nosocomial spread and persistence, causing a wide variety of serious infections, mostly in immunocompromised hospitalized patients, and is associated with an elevated mortality rate. The most common illness caused by A. baumannii is severe pneumonia that is frequently ventilator associated, but the pathogen also causes infections in the bloodstream, central nervous system, urinary tract, skin and soft tissues, and bone (9, 15).

The first-line treatment for serious A. baumannii infection relies on a carbapenem antibiotic such as imipenem or meropenem. These are beta-lactams that affect peptidoglycan synthesis by interacting with the active center of penicillin-binding proteins (PBPs), with inhibition of the transpeptidation reaction (12). Alarmingly, resistance to carbapenems is increasingly common. This is due mainly to the production of chromosome- or plasmid-encoded carbapenemases but also to changes in outer membrane porins, multidrug efflux pumps, or alteration in the affinity or expression of PBPs (5). These mechanisms often work in concert, resulting in multidrug-resistant strains (15). Other treatment options include the use of quinolones like ciprofloxacin or levofloxacin, which induce DNA double-strand breaks by trapping the DNA gyrase and/or topoisomerase IV on the DNA, resulting in DNA fragmentation (6). Nevertheless, resistance to quinolones is also emerging, through mutations mainly in the quinolone resistance-determining region (QRDR) within gyrA and parC genes (20, 21, 22), which interfere with the target binding, but resistance is also mediated by multidrug efflux pumps (5).

Standard antibiograms require nearly 24 h or even longer to yield results after the bacterial isolate has been identified. Sometimes, while waiting for results from the microbiology laboratory, physicians must implement empirical antibiotic therapy. Nevertheless, inappropriate empirical antimicrobial therapy is associated with increased mortality, and it is emphasized that early, adequate antibiotic therapy is essential to improve outcomes (7, 11, 13). Moreover, inadequate use of antibiotics contributes to the emergence and spread of drug resistance and increases toxic effects and health care costs. Rapid and reliable antimicrobial resistance testing should be of great relevance for selection of the most appropriate antibiotic therapy and optimized use of antimicrobials. For example, a fast assessment of carbapenem status may ensure a most favorable treatment in case of microbe susceptibility, avoiding misuse of antibiotics that should be reserved for cases of proven resistance. However, given the great facility to develop multidrug resistance in A. baumannii, a rapid evaluation of carbapenem and quinolone susceptibility should be of great interest. In fact, a recent nationwide multicenter study in Spain revealed that more than 93% and 81% of A. baumannii isolates showed lack of sensitivity to ciprofloxacin and to imipenem, respectively (data not shown).

We have developed a procedure to assess DNA integrity in bacteria, which has been validated as a rapid and simple assay for determination of susceptibility or resistance to quinolones in Escherichia coli (8, 17, 19). Cells trapped in an agarose microgel on a slide are incubated with a lysing solution to remove the cell wall from all the cells in the population; the nucleoids are then visualized under fluorescence microscopy after staining with the fluorochrome SYBR Gold. Using our procedure, DNA fragmentation induced by quinolones is visualized as DNA spots that diffuse peripherally from the nucleoid. The greater the DNA fragmentation, the greater the number of DNA spots and the width of the circular diffusion area around the central residual core. In the case of resistance to quinolones, the nucleoids appear intact, with limited spreading of DNA fiber loops (17).

More recently, the procedure was modified to evaluate cell wall integrity, i.e., the efficacy of antibiotics that affect peptidoglycan synthesis (18). For this purpose, the lysis must be adapted to affect only those bacteria whose cell walls have been damaged by the antibiotic. If the bacterium is susceptible, the weak cell wall is removed by the lysing solution so that the nucleoid contained inside the bacterium is released and spread. In the case of a resistant strain, bacteria are practically unaffected by the lysis solution and so do not liberate the nucleoid, which retains its usual shape.

In this straightforward report, we evidence the usefulness of using both technical variants to rapidly determine the susceptibility or resistance of A. baumannii to carbapenems, using meropenem as the antibiotic model, and ciprofloxacin.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

Three hundred twenty-two A. baumannii consecutive isolates obtained at University Hospital A Coruña (collected from 2001 to 2011) and from the bacterial collection of the Spanish Network for Research in Infectious Diseases were analyzed. Repetitive extragenic palindromic (REP)-PCR was performed in some cases to rule out clonality (2). Moreover, two reference strains obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA), ATCC 17978 and ATCC 19606, showing meropenem and ciprofloxacin susceptibility, were also assayed. Specific A. baumannii strains with defined carbapenem and ciprofloxacin resistance mechanisms were also used as controls. The MICs were determined by automated microdilution (MicroScan Walkaway; Siemens) and confirmed by Etest (AB Biodisk; bioMérieux) according to the manufacturer's instructions and following CLSI criteria for antibiotic susceptibility categorization.

DNA fragmentation assay.

Determination of DNA fragmentation and cell wall integrity was carried out as a blind procedure, without knowledge of the MICs. Two variants of the Micromax kit for fluorescence microscopy (Halotech DNA SL, Madrid, Spain), Micromax-Q and Micromax WG-, were employed to evaluate the integrity of the nucleoid and of the cell wall, respectively. The only difference between the two assays lies in the lysing solution.

Bacteria were routinely grown in Mueller-Hinton agar at 37°C for 24 h. A colony was grown with aeration and shaking in Mueller-Hinton broth at 37°C for 90 min. Then, the culture was diluted to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.1 in Mueller-Hinton broth. They were then incubated at 37°C in 200-μl tubes, with meropenem at 0, 4, 8, and 16 μg/ml and with ciprofloxacin at 0, 1, 2, and 4 μg/ml for 60 min, in a final volume of 30 μl. These concentrations were chosen according to the CLSI breakpoint concentrations of susceptibility, intermediate resistance, and resistance (3). The kit includes 0.5-ml snap cap microcentrifuge tubes containing gelled aliquots of low-melting-point agarose. The tube was placed in a water bath at 90 to 100°C for about 5 min to melt the agarose completely and then placed in a water bath at 37°C. Thirty microliters of the diluted sample was added to the tube and mixed with the melted agarose (the final concentration was 5 to 10 million microorganisms/ml). A 10-μl aliquot of the sample-agarose mixture was pipetted onto a precoated slide and covered with an 18- by 18-mm coverslip. The slide was placed on a cold plate in the refrigerator (4°C) for 5 min to allow the agarose to produce a microgel with the trapped intact cells inside. The coverslip was removed gently, and the slide was immediately immersed horizontally in 10 ml of the specific lysing solution for 5 min at room temperature for those bacteria incubated with meropenem and at 37°C for those incubated with ciprofloxacin. The slide was washed horizontally in a tray with abundant distilled water for 3 min, dehydrated by incubating horizontally in cold (−20°C) ethanol of increasing concentration (70%, 90%, and 100%) for 3 min each, and air dried in an oven, and the DNA was stained with 25 μl of the fluorochrome SYBR Gold (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) diluted 1:200 in Tris-borate-EDTA (TBE) buffer (0.09 M Tris-borate, 0.002 M EDTA, pH 7.5) for 2 min in the dark, with a glass coverslip. After a brief wash in phosphate buffer (pH 6.88) (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), a 24- by 60-mm coverslip was added, and the slides were visualized under fluorescence microscopy.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

According to the procedure, a strain is categorized as susceptible to meropenem when the nucleoids start to appear to spread following incubation with the drug at the CLSI breakpoint concentration of susceptibility (4 μg/ml), i.e., at 4, 8, and 16 μg/ml. Intermediate strains begin to release the nucleoids at the CLSI breakpoint dose of intermediate resistance (8 μg/ml), i.e., at 8 and 16 μg/ml. Resistant strains never liberate the nucleoids, or they do so only after incubation with the drug at the CLSI breakpoint dose of resistance (16 μg/ml). In relation to ciprofloxacin, a strain is susceptible when it shows DNA fragmentation from incubation with the drug at the CLSI breakpoint dose of susceptibility (1 μg/ml), i.e., at 1, 2, and 4 μg/ml. An intermediate strain reveals fragmented DNA after incubation at the CLSI breakpoint dose of intermediate resistance (2 μg/ml), i.e., at 2 and 4 μg/ml. In a resistant strain, nucleoids always appear intact or appear fragmented only after treatment with the drug at the CLSI breakpoint concentration of resistance (4 μg/ml).

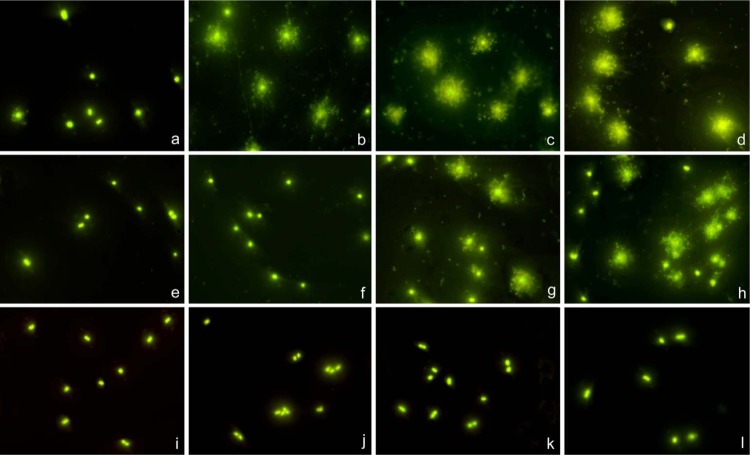

Susceptible strains and those with recognized mechanisms of reduced susceptibility or resistance were initially tested as control strains. For meropenem assays, commercial ATCC 19606 (MIC, 0.25 μg/ml) and ATCC 17978 (MIC, 0.5 μg/ml) were selected as susceptible strains. Strains producing serine β-lactamases oxacillinases OXA-24 (strain RYC 52763/97; MIC, 256 μg/ml) (1), OXA-58 (MIC, 16 μg/ml), and OXA-23 (MIC, 16 μg/ml) were chosen as resistant strains. An intermediate strain with MIC of 8 μg/ml was selected, i.e., strain JC10/01 (pAT-RA-34s) (4). Representative images are presented in Fig. 1. Susceptible strains showed nucleoid spreading at 4, 8, and 16 μg/ml, and intermediate strains revealed release of nucleoids after 8 and 16 μg/ml, whereas resistant strains did not reveal spreading of nucleoids at any dose, except those that liberated some nucleoids at an MIC of 16 μg/ml.

Fig 1.

Three representative strains of A. baumannii, incubated with meropenem for 60 min at 0 μg/ml (a, e, i) and at the 4-μg/ml CLSI breakpoint concentration of susceptibility (b, f, j), 8-μg/ml CLSI breakpoint concentration of intermediate resistance (c, g, k), and 16-μg/ml CLSI breakpoint concentration of resistance (d, h, l). Bacteria were processed to determine effects on the cell wall, evaluated through nucleoid releasing after incubation with a specific lysing solution. (a through d) Susceptible strain ATCC 19606 (MIC, 0.25 μg/ml); (e through h) intermediate strain JC10/01 (pAT-RA-34s) (MIC, 8 μg/ml); (i through l) resistant strain RYC 52763/97 producing OXA-24 (MIC, 256 μg/ml). Spreading of the nucleoids was obvious in the susceptible strain after 4, 8, and 16 μg/ml but only after 8 and 16 μg/ml in the intermediate strain. A discrete background of extracellular DNA fragments was visualized in the meropenem-affected cultures. In spite of susceptibility after 8 and 16 μg/ml, a proportion of cells remained apparently unaffected, without nucleoid spreading, in the intermediate strain. The resistant strain cells always maintained their morphological appearance.

For ciprofloxacin, the ATCC 17978 strain was used as susceptible control (MIC, ≤0.125 μg/ml). A clinical isolate intermediate strain (MIC, 2 μg/ml) and a resistant strain with mutations resulting in changes at codon 83 for gyrA (TCA→TTA) and at codon 80 for parC (TCG→TTG) (MIC, 64 μg/ml) (where underlining indicates a changed base) were also used as controls. The susceptible strain showed nucleoids with fragmented DNA after incubation at 1, 2, and 4 μg/ml, and the intermediate strain showed DNA fragmentation only after incubation at 2 and 4 μg/ml, whereas nucleoids always appeared intact in the resistant strain (Fig. 2).

Fig 2.

Three representative strains of A. baumannii, incubated with ciprofloxacin for 40 min at 0 μg/ml (a, e, i) and at the 1-μg/ml CLSI breakpoint concentration of susceptibility (b, f, j), 2-μg/ml CLSI breakpoint concentration of intermediate resistance (c, g, k), and 4-μg/ml CLSI breakpoint concentration of resistance (d, h, l). Bacteria were processed to visualize the nucleoids, determining the presence or absence of chromosomal DNA fragmentation, i.e., diffused DNA spots. (a through d) Susceptible strain ATCC 17978 (MIC, ≤0.125 μg/ml); (e through h) intermediate strain (MIC, 2 μg/ml); (i through l) resistant strain possessing both a gyrA Ser83 codon mutation (TCA→TTA) and a parC Ser80 codon mutation (TCG→TTG) (MIC, 64 μg/ml) (underlining indicates a changed base). DNA fragmentation was evident in the susceptible strain after incubation with the drug at 1, 2, and 4 μg/ml but only after incubation at 2 and 4 μg/ml in the intermediate strain. Nucleoids from the resistant strain never showed fragmentation.

Once the procedure had been successfully assayed in control strains, 322 clinical isolates were processed by the Micromax kits. MIC determination by automated microdilution and confirmed by Etest according to CLSI criteria was considered the gold standard method. According to the MICs and the CLSI criteria, 39 isolates were susceptible to both meropenem and ciprofloxacin, 37 were susceptible to meropenem and resistant to ciprofloxacin, only 1 isolate was resistant to meropenem and susceptible to ciprofloxacin, and 159 were resistant to both meropenem and ciprofloxacin. Regarding intermediate strains, 85 isolates were intermediate to meropenem and resistant to ciprofloxacin, and only one was intermediate to ciprofloxacin and susceptible to meropenem. Therefore, overall, 77, 85, and 160 isolates were susceptible, intermediate, and resistant to meropenem, respectively, whereas 40, 1, and 281 were susceptible, intermediate, and resistant to ciprofloxacin, respectively. The mechanism of nonsusceptibility to meropenem had been recognized in 140 selected intermediate and resistant isolates to be due to carbapenem-hydrolyzing activity, in agreement with nationwide studies that showed that OXA-type enzymes (OXA-24 [1, 14] specifically) are most prevalent in Spain. The cause of nonsusceptibility to ciprofloxacin for 110 isolates was established as the simultaneous mutations resulting in changes at codon 83 for gyrA and at codon 80 for parC (10, 20, 21).

The susceptibility to meropenem and/or to ciprofloxacin was always correctly identified by the assay. This was also the case for resistance to the antibiotics. The only strain categorized as intermediate to ciprofloxacin was exactly assigned by the assay. The status of intermediate to meropenem attributed to 85 isolates according to the CLSI criteria was similarly categorized by the assay in 82 cases, the rest (3.5%) being visualized as resistant, thus preventing the categorization as susceptible and the putative administration of carbapenems, which may cause a therapeutic failure. It must be emphasized that meropenem-intermediate strains were never detected as susceptible. Fifty isolates from the same study were also examined for imipenem and levofloxacin susceptibility or resistance. Results were fully coincident with those of meropenem or ciprofloxacin, following either CLSI criteria or the technical assay.

From a practical point of view, the clinician needs rapid, straightforward information about the susceptibility or nonsusceptibility of the isolate, in order to administer or not the appropriate antibiotic or to adequately assess the antibiotic treatment after the administration of the initial empirical therapy. While interesting to the microbiologist, the discrimination between intermediate or resistant classes should not modify the therapeutic decision, which should initially tend to discard meropenem use. Categorizing the isolates as susceptible or nonsusceptible using the CLSI breakpoint of susceptibility supposes a 100% accuracy of the assay. Thus, the technical handling of the procedure could be even more simplified by incubating the isolate with the drug only at the CLSI breakpoint concentration of susceptibility while simultaneously processing reliable susceptible, intermediate, and resistant strains as assay controls.

The technical processing of antibiotic-treated bacteria takes 40 min, and visualization under fluorescence microscopy is rapid and conclusive. Prior incubation with the antibiotics was standardized to 60 min. Although 40 min is enough for quinolones, 60 min is better for beta-lactams. This incubation time is estimated for bacteria exponentially growing in broth cultures. When the bacteria come from an agar plate, a 90-min incubation in Mueller-Hinton broth prior to the addition of carbapenem results in more-homogeneous images of the bacteria. This is due to the exponential growth of the whole population at the moment of addition of the antibiotic.

Some extracellular DNA fragments are evident as background in cultures of A. baumannii susceptible to meropenem during the assay, without the necessity for a lysing step (Fig. 1) (18). Nevertheless, this background is variable, is usually very limited, and sometimes may be present in cultures not subjected to incubation with the antibiotic. Intermediate strains may or may not show the extracellular DNA fragments. It is much more stringent to use the lysing solution to assess the possible effect of meropenem, evaluating the cell wall integrity through releasing of the nucleoid. The presence of extracellular DNA fragments is a complementary but not rigorous criterion.

The assay described here has been demonstrated to be a rapid, simple, and reliable procedure to determine susceptibility or nonsusceptibility of clinical isolates of A. baumannii to carbapenems and quinolones. Such a technique may have high clinical relevance, given the major challenge to patient safety of this pathogen and the critical importance of an appropriate antibiotic therapy as early as possible to improve outcomes in vulnerable hospitalized patients (7, 11, 13). An adequate early treatment also reduces the length of hospital stay and health care costs. In the actual context of reduction in the discovery and development of new antibiotics, rational therapeutic strategies must aim to restrict the use of those that are most effective in order to avoid the emergence and spreading of resistance (16). This could also be a potential benefit of the assay. The procedure for rapid assessment of susceptibility or resistance is going to be implemented for more antibiotic families, not only in A. baumannii but also in other pathogens of high clinical impact.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work has been supported by grants from the European Community, FP 7, ID: 278232 (MagicBullet), Xunta de Galicia 10CSA916020PR, and by REIPI, Spanish Network for Research in Infectious Diseases (Instituto de Salud Carlos III, RD06/0008/0025) and the Fondo de Investigaciones Sanitarias (PS09/00687) to G.B.

We are grateful to Godfrey Hewitt, University of East Anglia, Norwich, United Kingdom, for the critical reading of the manuscript and improving of the English style.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 29 August 2012

REFERENCES

- 1.Bou G, Oliver A, Martínez-Beltrán J. 2000. OXA-24, a novel class D β-lactamase with carbapenemase activity in an Acinetobacter baumannii clinical strain. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:1556–1561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cartelle M, et al. 2004. Risk factors for colonization and infection in a hospital outbreak caused by a strain of Klebsiella pneumoniae with reduced susceptibility to expanded-spectrum cephalosporins. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:4242–4249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute 2012. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing, twenty-second informational supplement. M100-S22, vol 32, no. 3. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA [Google Scholar]

- 4.del Mar Tomas M, et al. 2005. Cloning and functional analysis of the gene encoding the 33- to 36-kilodalton outer membrane protein associated with carbapenem resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:5172–5175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dijkshoorn L, Nemec A, Seifert H. 2007. An increasing threat in hospitals: multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 5:939–951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Drlica K, Malik M, Kerns RJ, Zhao X. 2008. Quinolone-mediated bacterial death. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:385–392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Falagas ME, Kasiakou SK, Rafailidis PI, Zouglakis G, Morfou P. 2006. Comparison of mortality of patients with Acinetobacter baumannii bacteraemia receiving appropriate and inappropriate empirical therapy. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 57:1251–1254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fernández JL, et al. 2008. DNA fragmentation in microorganisms assessed in situ. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74:5925–5933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gootz TD, Marra A. 2008. Acinetobacter baumannii: an emerging multidrug-resistant threat. Expert Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 6:309–325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hujer KM, et al. 2009. Rapid determination of quinolone resistance in Acinetobacter spp. J. Clin. Microbiol. 47:1436–1442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iregui M, Ward S, Sherman G, Fraser VJ, Kollef MH. 2002. Clinical importance of delays in the initiation of appropriate antibiotic treatment for ventilator-associated pneumonia. Chest 122:262–268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koch AL. 2003. Bacterial wall as target for attack: past, present, and future research. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 16:673–687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kollef KE, et al. 2008. Predictors of 30-day mortality and hospital costs in patients with ventilator-associated pneumonia attributed to potentially antibiotic-resistant gram-negative bacteria. Chest 134:281–287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Merino M, et al. 2010. OXA-24 carbapenemase gene flanked by XerC/XerD-like recombination sites in different plasmids from different Acinetobacter species isolated during a nosocomial outbreak. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:2724–2727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peleg AY, Seifert H, Paterson DL. 2008. Acinetobacter baumannii: emergence of a successful pathogen. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 21:538–582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peleg AY, Hooper DC. 2010. Hospital-acquired infections due to gram-negative bacteria. N. Engl. J. Med. 362:1804–1813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Santiso R, et al. 2009. Rapid and simple determination of ciprofloxacin resistance in clinical strains of Escherichia coli. J. Clin. Microbiol. 47:2593–2595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Santiso R, et al. 2011. A rapid in situ procedure for determination of bacterial susceptibility or resistance to antibiotics that inhibit peptidoglycan biosynthesis. BMC Microbiol. 11:19 doi:10.1186/1471-2180-11-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tamayo M, Santiso R, Gosálvez J, Bou G, Fernández JL. 2009. Rapid assessment of ciprofloxacin effect on chromosomal DNA from Escherichia coli with an in situ DNA fragmentation assay. BMC Microbiol. 9:69 doi:10.1186/1471-2180-9-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vila J, Ruiz J, Goni P, Marcos A, Jimenez de Anta T. 1995. Mutation in the gyrA gene of quinolone-resistant clinical isolates of Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 39:1201–1203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vila J, Ruiz J, Goni P, Jimenez de Anta T. 1997. Quinolone-resistance mutations in the topoisomerase IV parC gene of Acinetobacter baumannii. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 39:757–762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wisplinghoff H, et al. 2003. Mutations in gyrA and parC associated with resistance to fluoroquinolones in epidemiologically defined clinical strains of Acinetobacter baumannii. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 51:177–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]