Abstract

Declining malaria transmission and known difficulties with current diagnostic tools for malaria, such as microscopy and rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs) in particular at low parasite densities, still warrant the search for sensitive diagnostic tests. Molecular tests need substantial simplification before implementation in clinical settings in countries where malaria is endemic. Direct blood PCR (db-PCR), circumventing DNA extraction, to detect Plasmodium was developed and adapted to be visualized by nucleic acid lateral flow immunoassay (NALFIA). The assay was evaluated in the laboratory against samples from confirmed Sudanese patients (n = 51), returning travelers (n = 214), samples from the Dutch Blood Bank (n = 100), and in the field in Burkina Faso (n = 283) and Thailand (n = 381) on suspected malaria cases and compared to RDT and microscopy. The sensitivity and specificity of db-PCR-NALFIA compared to the initial diagnosis in the laboratory were 94.4% (95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.909 to 0.969) and 97.4% (95% CI = 0.909 to 0.969), respectively. In Burkina Faso, the sensitivity was 94.8% (95% CI = 0.88.7 to 97.9%), and the specificity was 82.4% (95% CI = 75.4 to 87.7%) compared to microscopy and 93.3% (95% CI = 87.4 to 96.7%) and 91.4% (95% CI = 85.2 to 95.3%) compared to RDT. In Thailand, the sensitivity and specificity were 93.4% (CI = 86.4 to 97.1%) and 90.9 (95% CI = 86.7 to 93.9%), respectively, compared to microscopy and 95.6% (95% CI = 88.5 to 98.6%) and 87.1% (95% CI = 82.5 to 90.6) compared to RDT. db-PCR-NALFIA is highly sensitive and specific for easy and rapid detection of Plasmodium parasites and can be easily used in countries where malaria is endemic. The inability of the device to discriminate Plasmodium species requires further investigation.

INTRODUCTION

Proper and fast diagnosis followed by appropriate treatment is essential for the management of malaria (20) and is fundamental for the control and eradication of the disease. Nevertheless, in many areas particularly, in resource-poor settings, the diagnosis of malaria is still based on clinical symptoms without laboratory confirmation. Laboratory examination of blood specimens to support malaria diagnosis is mainly based on microscopy or rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs) (18). However, these tests require experienced staff (microscopy) or have a low detection limit (RDTs) (5). Molecular techniques such as PCR to detect Plasmodium infections have demonstrated high sensitivity and specificity (14, 15) and have the ability to quantify parasitemia when used in a quantitative real-time PCR format. Therefore, molecular technologies are frequently used in malaria studies and in well-equipped laboratories as the “gold standard” (15). However, the implementation of molecular techniques in resource-poor settings is hindered by the requirement for DNA isolation, as well as careful handling of the clinical specimen in order to avoid sample contamination. In addition, the analysis of amplicons obtained from conventional PCR formats is elaborate and often requires either a toxic and environmentally hazardous ethidium bromide gel for visualization. An alternative is expensive real-time PCR equipment for analysis (3, 6).

Notwithstanding the above, a more sensitive tool for the detection of low-level parasitemia is needed not only for general malaria case management but especially in areas where malaria incidence is decreasing. In these areas, close vigilance of patients and asymptomatic carriers harboring a low level of parasites is essential for immediate treatment and subsequent case detection in order to avoid a resurgence of malaria.

Several attempts have been made to simplify molecular tools such as the amplification of DNA in an isothermal manner (7), adding the specimen without complete DNA isolation (4), or by adding colorimetric substances that allow the PCR result to be interpreted visually (8). In the present study, a direct blood PCR (db-PCR) combined with a rapid readout system, nucleic acid lateral flow immunoassay (NALFIA), is described. The direct blood approach circumvents preamplification handling such as DNA extraction. The full blood sample can be directly added to the PCR mixture and subsequently amplify the target DNA of Plasmodium in less than 1 h.

Thereafter, the product can be visualized with NALFIA, which is a rapid immunochromatographic test to detect labeled amplicon products on a nitrocellulose stick coated with specific antibodies (12). The amplicons are labeled via specific primers that contain a biotin molecule and a hapten. This complex is detected by direct interaction with a colloidal, neutravidin-labeled carbon particle. The detection test is a simple, straightforward, and safe one-step procedure in which the results are visible within 10 min. This methodology was extensively tested in a laboratory setting and subsequently evaluated for its sensitivity and specificity compared to RDT and expert microscopy in Nanoro, Burkina Faso, and Mae Sot, Thailand—two areas of high endemicity for P. falciparum and P. falciparum/P. vivax, respectively.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

db-PCR.

The db-PCR is based on a combination of Phusion db-PCR buffer (Finnzymes, Espoo, Finland) and Phire Hotstart II DNA polymerase (Finnzymes). The dB-PCR requires two primer pairs, one pair for the amplification of pan-Plasmodium and the second pair for amplification of the human housekeeping gene glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH). The GAPDH gene is used as an amplification control, as well as an internal running control for the NALFIA (see below for the interpretation of the results). In order to prevent extra handling steps, an internal amplification control from another source was not added. Each primer pair contains a digoxigenin- or Texas Red-labeled primer and a primer labeled with biotin. The dB-PCR comprises of 10 μl of Phusion blood direct buffer, 250 nM Plasmodium 18S forward primer (digoxigenin-5′-TCAGATACCGTCGTAATCTTA-3′), 250 nM Plasmodium 18S reverse primer (biotin-5′-AACTTTCTCGCTTGCGCG-3′), 88 nM GAPDH forward (biotin-5′-TGCACCACCAACTGCTTAGC-3′), and 88 nM GAPDH reverse primer (Texas Red-5′-GGCATGGACTGTGGTCATGAG-3′), 0.4 μl of Phire Hotstart II DNA polymerase, water, and 2.5 μl of EDTA blood, with a final volume of 25 μl. The cycling conditions consisted of an initial activation step of 30 s at 98°C, followed by 10 cycles of 5 s at 98°C, 15 s at 60°C and 30 s at 72°C, than 28 cycles of 5 s at 98°C, 15 s at 58°C, and 30 s at 72°C, and a final step of 1 min at 72°C (MyCycler; Bio-Rad). For each experiment a blood sample negative for Plasmodium, a blood sample containing P. falciparum and a nontemplate control of only water were used as control samples.

NALFIA.

A HiFlow 135 nitrocellulose membrane (25 by 5 mm per strip) (Millipore, Amsterdam, Netherlands) was used to fabricate the NALFIA sticks for this assay. On the nitrocellulose, 0.8 mg/ml (0.8 μl/cm) of anti-Texas Red rabbit IgG fraction (Invitrogen, Paisley, United Kingdom) and 0.2 mg/ml (0.8 μl/cm) of anti-digoxigenin polyclonal antibody (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim Germany) were sprayed within 9 mm of one another. A Surewick G041 glass fiber sample pad (Millipore, Billerica, MA) was used to spray 2.5 μl of neutravidin-labeled carbon suspension (three parts neutravidin-labeled carbon/cm and two parts sodium tetraborate buffer solution containing 6.25% sucrose and 6.25% bovine serum albumin [BSA]) and attached to the NALFIA stick. The strips were air dried at 37°C, packed in plastic housing, and sealed in air-tight bags containing silica until further use.

Detection of PCR fragments by NALFIA and gel electrophoresis.

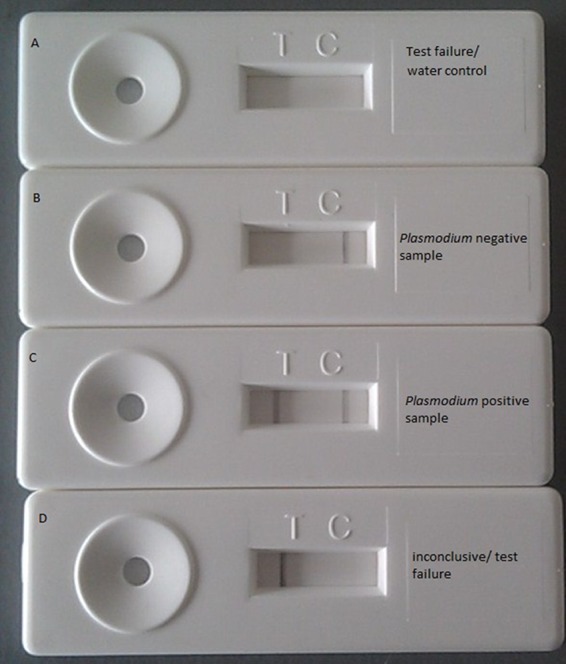

After PCR, 5 μl of PCR product and 70 μl of running buffer (0.1 M borate buffer [pH 8.8], 1% BSA, and 1% [wt/vol] sodium azide) were added on the sample pad of the NALFIA and, after 10 min, the results were read. The NALFIA was considered valid but negative for Plasmodium if a black line at the GAPDH position was visible (control line). If two lines (control and test line) were visible, the NALFIA was considered to be positive for Plasmodium. If no lines were present or only a single test line was present, the NALFIA was considered to be a test failure. Examples of the different interpretation possibilities can be found in Fig. 1.

Fig 1.

Examples of different test outcomes of the db-PCR-NALFIA. Control and test lines are absent. (A) This is a test failure but can also be seen when only water is amplified (negative control). (B) A positive control line is visible and a test line is absent, indicating that the test is valid but that no parasite DNA is detected. (C) Both a positive control and a test line are visible, indicating a valid test positive for Plasmodium. (D) Only the test line is visible. This test should be considered a test failure.

During laboratory evaluation NALFIA analysis was compared to visualization of DNA bands in ethidium bromide-stained 3% agarose gels in which a pan-Plasmodium fragment of 180 bp and human GAPDH fragment of 224 bp could be observed.

Laboratory evaluation db-PCR-NALFIA.

The analytical sensitivity of the dB-PCR-NALFIA was assessed in triplicate by using a 5% P. falciparum NF54 ring stage culture (in 5% hematocrit) and a P. falciparum-positive patient blood sample with 12% parasitemia. The cultured parasites were diluted 10-fold with Plasmodium-negative donor blood to obtain malaria parasites dilutions ranging from 0.55 to 5.10−8% in a 45% hematocrit. The patient sample was diluted to a Plasmodium density of 12 to 5.10−4%.

The specificity of the test was determined by analyzing malaria-positive and -negative EDTA blood samples (n = 365) from travelers returning from areas of malaria endemicity, from Sudanese patients with a confirmed P. falciparum infection, and samples provided by the Dutch Blood Bank, which excludes donations from patients who have traveled in the past 9 months to areas of malaria endemicity and can therefore be considered negative for malaria. The samples from returning travelers were provided by the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (London, United Kingdom), and the samples from Sudanese patients (n = 51) were provided by the Wad Medani Teaching Hospital in Sudan. These blood samples were analyzed by an experienced technician by microscopy and/or Plasmodium-specific nested PCR according to the method of Snounou et al. (17). The malaria-positive samples (n = 250) contained the following species: P. falciparum (n = 65), P. vivax (n = 33), P. malariae (n = 48), P. ovale (n = 92), P. falciparum-P. malariae mixed infection (n = 4), P. falciparum-P. vivax mixed infection (n = 5), and P. falciparum-P. ovale mixed infection (n = 3). Samples of malaria-suspected patients (n = 15) that were found to be negative by expert microscopy and PCR served together with the Dutch blood bank samples (n = 100) as negative controls.

Field evaluation of db-PCR-NALFIA study site and patient description.

Two prospective studies were conducted: one in the Health and Social Promotion Centers of Nanoro Health District (Nanoro and Nazoanga), Boulkiemdé Province, Burkina Faso, and the other in Wang Pa and Mae Khon Ken, Mae Sot district, Tak Province, Thailand. Malaria in Nanoro is holoendemic, and transmission is perennial, with a seasonal peak during the rainy season that usually lasts from June to October (21). P. falciparum was the main infecting species. That study was performed in conjunction with the ongoing study “Pharmacovigilance for Artemisinin-Based Combination Treatments in Africa” (protocol A70283). After collection, samples were transported to the Clinical Research Unit of Nanoro for further analysis and processing.

Mae Sot is located on the Thai-Myanmar border. In this hill-forested region, with low year-round transmission and two seasonal peaks, the predominant species causing malaria are P. vivax, and during the rainy season, P. falciparum (16). Patients were recruited in the malaria clinics of Wang Pa and Mae Khon Ken located around Mae Sot. Samples were transported to the Shoklo Malaria Research Unit (SMRU) in Mae Sot for further processing.

Patients presenting in outpatient clinics with a clinical suspicion of uncomplicated malaria and an axillary temperature ≥37.5°C or a history of fever in the past 24 h were enrolled. In Burkina Faso patients of all ages were enrolled, whereas in Thailand patients older than 3 years were enrolled. For both field evaluations ethical approval was obtained from local ethical review boards.

Laboratory procedure field evaluation.

From each participant, 200 μl of finger prick blood was collected in EDTA tubes (Stastedt, Numbrecht, Germany) for the preparation of thin and thick Giemsa-stained microscopy slides, a histidine-rich protein II- and Plasmodium lactate dehydrogenase-based RDT (SD Bioline Malaria Antigen Pf/Pan; Standard Diagnostics, Inc., Kyonggi-do, Korea), and the db-PCR-NALFIA. Microscopy was performed according to international and good clinical and laboratory practices guidelines by local expert microscopists (19, 22). In Burkina Faso, parasites were counted against 200 leukocytes, with parasite-negative results based on screening of 100 microscopic fields at ×1,000 magnification. In the case of lower parasitemia (<10 parasites/200 leukocytes), parasites were counted against 500 leukocytes. Slides were examined by two readers and, in the case of discordant results, by a third reader. Discordant results were defined as a difference between the two readers in (i) Plasmodium species, (ii) positive and negative, (iii) with parasitemia > 400/μl; if the higher count divided by the lower count was >2 or >4) with parasitemia at ≤400/μl and if the higher reading density was >1 log10 higher than the lowest reading. In Thailand, parasites were counted against 500 leukocytes at ×1,000 magnification. If only one parasite was found after counting 500 leukocytes, then counting continued until a second parasite was observed with a limit of counting 4,000 leukocytes. Also, here all slides were read by two individual microscopists, and discordant results were read by a third reader. For both settings, a leukocyte count of 8,000/μl was assumed to calculate the parasite density per μl, and the final result was the geometric mean of the readings. In both settings, peripheral blood was applied to the SD Bioline Malaria Antigen Pf/Pan RDT according to the manufacturer's instructions. The db-PCR-NALFIA was performed as described above by local operators. All test operators were blinded from each other's test result. A Plasmodium species differentiation PCR was performed as described by Snounou et al. (17) on specimens that yielded discordant results and on a selection of microscopy-negative samples from Thailand. For the differentiation PCR, DNA was extracted from blood using a DNA minikit (Qiagen, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Samples from Burkina Faso were not available for species differentiation PCR analysis.

Data analysis.

All data from the field evaluations were collected on separate case record forms and subsequently entered into Microsoft Excel. Calculations on sensitivity, specificity, and agreement between the microscopy, RDT, and db-PCR-NALFIA results were done using Epi Info version 6.04 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA). The kappa (κ) value (calculated with a 95% confidence interval [CI]) expresses the agreement beyond chance (2). A κ value of 0.21 to 0.60 is moderate, a κ value of 0.61 to 0.80 is good, and a κ value of >0.80 is an almost-perfect agreement beyond chance.

RESULTS

Analytical performance of the db-PCR-NALFIA.

The lower detection limit of the developed db-PCR-NALFIA was determined to be 1 parasite/μl and 8 parasites/μl when tested on cultured parasites and patient blood, respectively. db-PCR-NALFIA was able to detect a 10-fold-higher dilution than the ethidium bromide staining of agarose gels (data not shown).

In total, 365 samples were analyzed by db-PCR-NALFIA and compared to their initial laboratory diagnosis. Of the 115 samples considered to be negative in their initial diagnosis, 112 were also found to be negative by db-PCR-NALFIA. The three positive samples belonged to the group of Dutch Blood Bank donors. Fourteen samples that were initially identified as positive for Plasmodium were identified as negative by db-PCR-NALFIA. Of these, seven samples contained P. falciparum, one sample contained P. vivax, three samples were microscopically identified as P. ovale, and two were microscopically identified as P. malariae. In addition, one P. falciparum-P. vivax mixed infection was missed by the assay. The sensitivity and specificity db-PCR-NALFIA were, respectively, 0.944 (95% CI = 0.909 to 0.969) and 0.974 (95% CI = 0.926 to 0.995) with an agreement of 0.953 (95% CI = 0.926 to 0.973) and a Cohen's kappa value of 0.894 (95% CI = 0.846 to 0.944).

All PCR products were also analyzed using gel-electrophoresis. Thirteen of the fourteen samples that were found to be negative by db-PCR-NALFIA but positive for Plasmodium in their initial diagnosis were determined to be negative by gel analysis as well. However, in total 11 samples identified as Plasmodium positive at initial diagnosis were found to be positive by db-PCR-NALFIA but negative by gel analysis. One sample containing P. malariae was determined to be positive by gel electrophoresis and negative by db-PCR-NALFIA. The three samples from Dutch Blood Bank donors that were determined to be positive with db-PCR-NALFIA were negative by gel electrophoresis.

Evaluation of the db-PCR-NALFIA in areas of malaria endemicity.

The evaluation of the db-PCR-NALFIA in Burkina Faso took place shortly after the rainy season from November 2010 to May 2011. In total, 283 malaria-suspected patients were included in the study. A total of 54% of the participants were female, and 46% male, with a mean age of 4.1 years (range, 5 months to 56 years).

During the first 2 months recruitment was focused on microscopy positive cases. An overview of the results of the different tests can be found in Table 1. In total, 122 microscopy positive participants were included, of which four cases were P. falciparum-P. malariae coinfections and one was a P. falciparum-P. ovale coinfection. The parasitemia ranged from 66 to 235,417 parasites/μl (geometric mean = 11,519 parasites/μl). Of the 122 microscopy-positive samples, 118 were also determined to be positive by RDT. The four samples determined to be negative by RDT had microscopic parasitemia levels ranging from 336 to 2,664 parasites/μl. However, 23 of the microscopy-negative samples were positive by RDT. The agreement between microscopy and RDT was 90%. When db-PCR-NALFIA is compared to microscopy, only 276 samples could be analyzed since four samples were not available for db-PCR-NALFIA analysis, and three samples were inconclusive. Of the 276 remaining samples 28 microscopy-negative samples were determined to be positive with db-PCR-NALFIA and six microscopy-positive samples were determined to be negative with the PCR method. Of these six microscopy positive samples, three were also negative by RDT. Of the 28 microscopy-negative samples that were determined to be positive by db-PCR-NALFIA, 17 were also positive by RDT (Table 1). The agreement, predictive values, sensitivity, and specificity of all tests compared to each other are shown in Table 2.

Table 1.

Number of samples that were positive or negative in respective diagnostic tests in Burkina Faso

| db-PCR-NALFIA result | RDT result | Microscopy (no. of positive or negative samples) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative | Positive | Total | ||

| Missing or inconclusive | Negative | 2 | 2 | |

| Positive | 5 | 5 | ||

| Negative | Negative | 125 | 3 | 128 |

| Positive | 6 | 3 | 9 | |

| Positive | Negative | 11 | 1 | 12 |

| Positive | 17 | 110 | 127 | |

| Total | 161 | 122 | 283 | |

Table 2.

Sensitivity, specificity, and agreement of different diagnostic tests in Burkina Faso and Thailanda

| Location and comparison (n) | Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | PPV (95% CI) | NPV (95% CI) | κ value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Burkina Faso | |||||

| SD Bioline vs microscopy (283) | 0.967 (0.913–0.989) | 0.857 (0.791–0.905) | 0.837 (0.763–0.891) | 0.972 (0.925–0.991) | 0.81 |

| Microscopy vs dB-PCR-NALFIA (276) | 0.799 (0.720–0.860) | 0.956 (0.903–0.982) | 0.949 (0.887–0.979) | 0.824 (0.754–0.878) | 0.75 |

| SD Bioline vs dB-PCR-NALFIA (276) | 0.914 (0.851–0.953) | 0.934 (0.875–0.968) | 0.934 (0.875–0.968) | 0.914 (0.851–0.953) | 0.85 |

| Thailandb | |||||

| SD Bioline vs microscopy (377) | 0.813 (0.724–0.879) | 0.985 (0.960–0.995) | 0.956 (0.885–0.986) | 0.930 (0.892–0.956) | 0.83 |

| Microscopy vs dB-PCR-NALFIA (381) | 0.798 (0.715–0.863) | 0.973 (0.942–0.988) | 0. 934 (0.864–0.971) | 0.909 (0.867–0.939) | 0.80 |

| SD Bioline vs dB-PCR-NALFIA (377) | 0.702 (0.612–0.779) | 0.984 (0.958–0.995) | 0.956 (0.885–0.986) | 0.871 (0.825–0.906) | 0.74 |

PPV, positive predictive value; NPV, negative predictive value. n, Number of samples.

All calculations are before species differentiation PCR correction and with the results of P. falciparum and P. vivax detection combined.

In Thailand, the evaluation of the db-PCR-NALFIA was performed from December 2011 to January 2012. In total, 381 patients were included. The mean age of the participants was 20.6 years (range, 4 to 63 years), 33% were female and 67% were male. In total, 107 participants had a positive microscopy slide (Table 3): 32 patients had P. falciparum infections, 72 had P. vivax infections, and 3 mixed infections were observed, one of which was P. vivax-P. malariae. The mean parasitemias of P. falciparum and P. vivax were 5,185 and 730 parasites/μl, respectively. RDT detected all P. falciparum cases. However, 19 samples that were determined to be P. vivax positive by microscopy were negative by RDT (Table 3), resulting in a lower overall sensitivity than that observed in the patients from Burkina Faso (Table 2). Three of the four patients considered negative for malaria by microscopy but positive by RDT had a history of malaria in the last 2 months prior to enrollment. The overall agreement between microscopy and RDT was 92%. When microscopy and db-PCR-NALFIA were compared, 25 of the microscopy-negative samples were found to be positive; 3 of which these patients were reported to have had a history of malaria in the previous 2 months, and 1 of them was also positive by RDT. Seven of the P. vivax-positive samples determined by microscopy were negative by db-PCR-NALFIA (Table 3). Four had a parasitemia of <2 parasites/μl, and the other three had 4, 10, and 32 parasites/μl, respectively. The agreement, predictive values, sensitivity, and specificity of all tests compared to each other are summarized in Table 2. All specimens that yielded discordant results, as well as 65 microscopy- and db-PCR-NALFIA-negative samples from Thailand, were tested by the species differentiation PCR. This showed that of the 25 db-PCR-NALFIA-positive/microscopy-negative samples, 13 were positive with the species differentiation PCR (12 P. vivax and 1 P. falciparum). The remaining 12 were negative, including the samples from the three patients with a history of malaria. Six of the seven P. vivax samples that were positive by microscopy and negative by db-PCR-NALFIA were also positive with the differentiation PCR. Of the 65 samples that were determined to be negative by microscopy, RDT, and db-PCR-NALFIA, 12 were positive with the species differentiation PCR (3 P. falciparum and 9 P. vivax).

Table 3.

Number of samples that were positive or negative in respective diagnostic tests in Thailand

| db-PCR-NALFIA result | RDT result | Microscopy (no. of positive or negative samples) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative | Positive (P. falciparum) | Positive (P. vivax) | Mixed | Total | ||

| Negative | Total | 249 | 1b | 7c | 257 | |

| Negativea | 246 | 7 | 253 | |||

| Positive (P. falciparum) | 3 | 1 | 4 | |||

| Positive | Total | 25d | 31 | 65 | 3 | 124 |

| Negative | 24 | 12 | 1e | 37 | ||

| Positive (P. falciparum) | 1 | 31 | 1 | 2f | 35 | |

| Positive (P. vivax) | 52 | 52 | ||||

| Total | 274 | 32 | 72 | 3 | 381 | |

Includes four tests that were in conclusive.

Containing Plasmodium falciparum gametocytes only from a patient with history of malaria 1 week preceding testing.

All positive for P. vivax, with confirmative PCR according to Snounou et al. (17).

Includes three samples from patients with a history of malaria in the week preceding testing. Thirteen of these samples were also positive for Plasmodium with confirmative PCR.

Mixed infection of P. vivax and P. malariae.

Mixed infection of P. falciparum and P. vivax.

When the microscopy-positive samples were stratified by parasitemia, it was shown that db-PCR-NALFIA and RDT had similar sensitivities for the samples from Burkina Faso and that db-PCR-NALFIA was more sensitive than RDT for the samples from Thailand (Table 4). This difference was due to the presence of P. vivax in samples from Thailand, for which db-PCR-NALFIA was substantially more sensitive than RDT.

Table 4.

Sensitivities of SD-Bioline RDT and db-PCR-NALFIA in Burkina Faso and Thailand versus microscopy-determined levels of parasitemia

| Parasitemia level (count/μl) | % Sensitivity (no. of positive samples/total no. of samples tested)a |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Burkina Faso |

Thailand |

|||

| SD Bioline RDT | db-PCR-NALFIA | SD Bioline RDT | db-PCR-NALFIA | |

| >50,000 | 100 (27/27) | 95.8 (23/24) | 100 (3/3) | 100 (3/3) |

| 5,000 to 50,000 | 100 (59/59) | 98.8 (57/58) | 100 (49/49) | 100 (49/49) |

| 500 to 5,000 | 86.2 (25/29) | 92.9 (26/28) | 100 (22/22) | 100 (22/22) |

| 100 to 500 | 80.0 (4/5) | 80.0 (4/5) | 81.8 (9/11) | 100 (11/11) |

| 50 to 100 | 100 (4/4) | 75.0 (3/4) | 66.7 (2/3) | 100 (3/3) |

| <50 | 10.5 (2/19) | 57.9 (11/19) | ||

Sensitivities that are remarkably low are indicated in boldface.

DISCUSSION

We describe here a sensitive and robust method, db-PCR-NALFIA, for the detection of Plasmodium species directly from blood samples. The standard PCR technology has been simplified by circumventing DNA extraction prior to amplification and adding an easy visual detection of the products using a lateral flow immunoassay. Most PCR protocols still require some specimen processing steps such as boiling or chemical treatment of samples or postamplification analysis that requires equipment or instrumentation (4). The sensitivity and specificity of the db-PCR-NALFIA was good in both in laboratory setting and for field evaluations. However, in the laboratory evaluation, 14 samples initially identified as Plasmodium positive were found to be negative with db-PCR-NALFIA. This could be due to DNA degradation since these samples were stored for several years under suboptimal storage conditions in a refrigerator.

The db-PCR-NALFIA is similar in concept to the simple RDT, except that the lateral flow immunoassay is preceded by a PCR. This makes the technology more complicated and so requires some additional training. However, we have shown that db-PCR-NALFIA is much more sensitive than RDT, especially for the detection of P. vivax. There were discrepancies in results between the db-PCR-NALFIA and microscopy and RDT. Although in both field settings there were false-negative db-PCR-NALFIA samples that were determined to be positive by microscopy and/or RDT, there were a greater number of false-positive db-PCR-NALFIA samples that were negative with the other methods. In both scenarios, this could be due to a very low number of parasites in samples (<2 parasites/μl), resulting in sampling error. Unfortunately, no sample material was available from Burkina Faso to perform the additional species differentiation PCR, but analysis of the discrepant samples from Thailand resolved a number of the apparent db-PCR-NALFIA false-positive results as in fact true positives and also confirmed the false-negative results. Remaining discordant samples could be due to sampling error. In 80% of the discordant db-PCR-NALFIA-positive samples, P. vivax DNA was found.

Although the field technicians were experienced in PCR technology, the db-PCR-NALFIA was performed in Burkina Faso by a technician after very little training in the protocol, and in Thailand the assay was performed without any prior training. This shows that the db-PCR-NALFIA can be performed by technicians with no or little training in the protocol itself.

One of the drawbacks of the current technology is the requirement for a reliable source of electricity for cold storage of the PCR reagents and the operation of the PCR thermal cycler. This may limit the current technology to areas where some laboratory infrastructure is available (18, 9). Regional or national malaria control programs could decentralize their testing since this is an operator-friendly technology in which a large number of people can be screened with a high sensitivity in a short time. This may be especially interesting in areas with moderate to low transmission, since the probability of having malaria is less in these areas and therefore sensitive and accurate diagnosis is essential (11). In the light of eradication programs, this technology may be useful for the detection of asymptomatic carriers that usually harbor low parasitemia. The availability of thermal cyclers that operate on solar-powered batteries (23) and room temperature-stable PCR reagents would expand the availability of this technology in resource-poor settings.

Another drawback of the technology is that, as with all antigen detection and molecular methods, db-PCR-NALFIA cannot differentiate between asexual (responsible for disease) and sexual (gametocytes, responsible for transmission) stages. This could potentially lead to the misdiagnosis of patients that harbor gametocytes but are suffering from a different disease as well. Clinical signs and ruling out of other conditions should thus always be considered when applying these tests.

The current db-PCR-NALFIA is highly sensitive for the detection of P. vivax, as well as P. falciparum, but the current format does not differentiate the Plasmodium species. The sensitivity of other human Plasmodium species—e.g., P. ovale, P. knowlesi, and P. malaria—could not be assessed here. For areas where there are high rates of transmission of P. vivax or other Plasmodium species, additional species-specific detection lines should be added to the db-PCR-NALFIA detection device. Since currently available RDTs have a low sensitivity for the detection of P. vivax (1, 10), in remote field settings microscopy is still the only relatively easy, although very time-consuming, field-deployable method for the detection of P. vivax (10).

The current db-PCR-NALFIA consists of a combination of components from two commercially available kits, the buffer component of the Phusion direct blood PCR kit and the separately available Phire Hotstart II DNA polymerase. Unfortunately, it was not possible to purchase the reagents separately from the complete kits, adding to the cost of the current technology and making it unnecessarily more expensive than conventional PCR. However, the ability to add blood directly to the PCR without any form of processing saves reagent costs. Ideally, all components would be combined in a single kit to make the assay affordable and convenient, which are prerequisites if large-scale implementation is desired (13). Because of the large-scale production, the price of the NALFIA detection device was <$0.50. Finally, it would be useful to provide standardized quality control material in order for laboratories to harmonize results among regions or countries (14, 9). This should always be accompanied by ongoing quality assurance, including training and continuing education of laboratory scientists (9, 13).

In conclusion, the db-PCR-NALFIA is a relatively easy-to-use method that is robust, sensitive, and specific and could have great potential in locales where malaria is endemic, especially in areas where there is low transmission of malaria, and thus a very sensitive technology is warranted.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This project was financially supported by the EU funded FP7 project MALACTRES (Multidrug Resistance in Malaria under Combination Therapy: Assessment of Specific Markers and Development of Innovative, Rapid and Simple Diagnostics) under grant 201889.

We thank all collaborators of the MALACTRES project for their fruitful discussions on the project and initial evaluation of the developed protocols. We want to specifically thank Colin Sutherland of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (United Kingdom) and Senior Lecturer of the Malaria Reference Laboratory (United Kingdom) and Bakri Nour from Wad Medani Teaching Hospital (Sudan) for kindly providing blood samples for the laboratory evaluation. We thank Marc Tahita (Unité de Recherche Clinique de Nanoro) for his supervision and support of the Burkina Faso trial and his staff and patients in Nanoro, Burkina Faso, for the possibility of doing this study in conjunction with the ongoing Pharmacovigilance study. We are also grateful to the staff and patients of the Mae Khon Ken and Wang Pa clinics and the Shoklo Malaria Research Unit (Thailand), part of the Mahidol-Oxford Tropical Medicine Research Unit (MORU) supported by the Wellcome Trust (United Kingdom), for their willingness to participate in this trial.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 22 August 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Alam MS, et al. 2011. Real-time PCR assay and rapid diagnostic tests for the diagnosis of clinically suspected malaria patients in Bangladesh. Malar J. 10: 175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Altman DG. 1991. Practical statistics for medical research, p. 611 Chapman & Hall, London, United Kingdom [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fabre R, Berry A, Morassin B, Magnaval JF. 2004. Comparative assessment of conventional PCR with multiplex real-time PCR using SYBR Green I detection for the molecular diagnosis of imported malaria. Parasitol. 128: 15–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fuehrer HP, et al. 2011. Novel nested direct PCR technique for malaria diagnosis using filter paper samples. J. Clin. Microbiol. 49: 1628–1630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hawkes M, Kain KC. 2007. Advances in malaria diagnosis. Expert Rev. Anti-Infect. Ther. 3: 485–495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kamau E, et al. 2011. Development of a highly sensitive genus-specific quantitative reverse transcriptase real-time PCR assay for detection and quantitation of plasmodium by amplifying RNA and DNA of the 18S rRNA genes. J. Clin. Microbiol. 49: 2946–2953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lucchi NW, et al. 2010. Real-time fluorescence loop mediated isothermal amplification for the diagnosis of malaria. PLoS One 5: e13733 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0013733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Luo L, et al. 2011. Visual detection of high-risk human papillomavirus genotypes 16, 18, 45, 52, and 58 by loop-mediated isothermal amplification with hydroxynaphthol blue dye. J. Clin. Microbiol. 49: 3545–3550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. malERA Consultative Group on Diagnoses and Diagnostics 2011. A research agenda for malaria eradication: diagnoses and diagnostics. PLoS Med. 8: 1000396 doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. McMorrow ML, Aidoo M, Kachur SP. 2011. Malaria rapid diagnostic tests in elimination settings—can they find the last parasite? Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 17: 1624–1631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mens P, et al. 2007. Is molecular biology the best alternative for diagnosis of malaria to microscopy? A comparison between microscopy, antigen detection and molecular tests in rural Kenya and urban Tanzania. Trop. Med. Int. Health 12: 238–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mens PF, van Amerongen A, Sawa P, Kager PA, Schallig HDFH. 2008. Molecular diagnosis of malaria for the field: development of a novel, 1-step nucleic acid lateral flow immunoassay for the detection of all 4 human Plasmodium spp. and its evaluation Mbita, Kenya. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 61: 421–427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Peeling RW, Mabey D. 2010. Point-of-care tests for diagnosing infections in the developing world Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 16: 1026–1029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Proux S, et al. 2011. Considerations on the use of nucleic acid-based amplification for malaria parasite detection. Malar. J. 10: 323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rantala AM, et al. 2010. Comparison of real-time PCR and microscopy for malaria parasite detection in Malawian pregnant women. Malar. J. 9: 269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. SMRU-Shoklo Malaria Research Unit 2012. Malaria on the Thai-Myanmar border. SMRU-Shoklo Malaria Research Unit, Mae-Sot, Thailand: http://www.shoklo-unit.com/MTF/tb_border.php [Google Scholar]

- 17. Snounou G, Viriyakosol S, Jarra W, Thaithong S, Brown KN. 1993. Identification of the four human malaria parasite species in field samples by the polymerase chain reaction and detection of a high prevalence of mixed infections. Molecular Biochem. Parasitol. 58: 283–292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Snounou G. 2007, Rapid, Sensitive and cheap molecular diagnostics of malaria: is microscopy on the way out? Future Microbiol. 2: 447–480 [Google Scholar]

- 19. World Health Organization 1991. Basic laboratory methods in medical parasitology. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland [Google Scholar]

- 20. World Health Organization 2010. Guidelines for the treatment of malaria, 2nd ed. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland [Google Scholar]

- 21. World Health Organization 2010. World malaria report: technical report. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland [Google Scholar]

- 22. World Health Organization 2010. Basic malaria microscopy. I. Learner's guide, 2nd ed. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland [Google Scholar]

- 23. Yashon RK, Cummings MR. 2012. Human genetics and society, 2nd ed, p 189 Brooks/Cole Cencage Learning, Independence, KY [Google Scholar]