Abstract

Influenza B virus hemagglutinin (BHA) contains a predicted cytoplasmic tail of 10 amino acids that are highly conserved among influenza B viruses. To understand the role of this cytoplasmic tail in infectious virus production, we used reverse genetics to generate a recombinant influenza B virus lacking the BHA cytoplasmic tail domain. The resulting virus, designated BHATail−, had a titer approximately 5 log units lower than that of wild-type virus but grew normally when BHA was supplemented in trans by BHA-expressing cells. Although the levels of BHA cell surface expression were indistinguishable between truncated and wild-type BHA, the BHATail− virus produced particles containing dramatically less BHA. Moreover, removal of the cytoplasmic tail abrogated the association of BHA with Triton X-100-insoluble lipid rafts. Interestingly, long-term culture of a virus lacking the BHA cytoplasmic tail in Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells yielded a mutant with infectivities somewhat similar to that of wild-type virus. Sequencing revealed that the mutant virus retained the original cytoplasmic tail deletion but acquired additional mutations in its BHA, neuraminidase (NA), and M1 proteins. Viral growth kinetic analysis showed that replication of BHA cytoplasmic tailless viruses could be improved by compensatory mutations in the NA and M1 proteins. These findings indicate that the cytoplasmic tail domain of BHA is important for efficient incorporation of BHA into virions and tight lipid raft association. They also demonstrate that the domain is not absolutely required for virus viability in cell culture in the presence of compensatory mutations.

INTRODUCTION

Influenza A and B viruses are enveloped negative-strand RNA viruses that assemble at and bud from the plasma membrane of infected cells. The envelope accommodates 3 or 4 different transmembrane proteins: hemagglutinin (HA) glycoprotein, neuraminidase (NA) glycoprotein, and M2 in influenza A viruses and HA, NA, BM2, and NB in influenza B viruses. HA, the major surface antigen, is a multifunctional protein with many essential roles in the virus life cycle. It has receptor binding and membrane fusion activities, both of which are indispensable for viral infection of host cells. Viral particles attach to cell surfaces through the binding of HA to viral receptors and are then endocytosed and transported to endosomes (33, 38, 54). The low pH inside the endosomes triggers a conformational change in HA (7, 10) to induce fusion of the viral envelopes with the endosomal membranes, causing the viral ribonucleoprotein complex to be released into the cytoplasm. HA is a homotrimer in which each monomer consists of two disulfide-linked polypeptides, HA1 and HA2, generated by proteolytic cleavage of the primary translation product, HA0. The HA2 subunit has a conserved structural organization: an ectodomain containing a hydrophobic fusion peptide, a single membrane-spanning domain, and a C-terminal cytoplasmic region.

In influenza A virus, the HA protein contains a cytoplasmic tail of 10 or 11 residues that are highly conserved among the different HA subtypes (48). For several subtypes of HA, it has been shown that mutation of certain residues in the cytoplasmic tail affects membrane fusion activity (44, 55, 63). The cytoplasmic tail of the HA protein has also been reported to play regulatory roles in virus assembly and budding at a late step of infection. Biochemical analyses indicated that truncation of the cytoplasmic tail of HA caused reduced association of HA with specific membrane microdomains termed lipid rafts (70), which are considered the assembly and binding sites of influenza A virus. In addition, association of the matrix protein M1 with the lipid rafts appears to be influenced by the presence or absence of the cytoplasmic tail of HA on the membrane (1, 70). A study with virus-like particle (VLP) systems demonstrated that the cytoplasmic tail of HA is required for efficient incorporation of M1 into VLPs (12). Reverse genetic studies also showed that the budding of a virus encoding a tailless HA was slightly impaired and that the growth of this virus was slightly attenuated (28). Furthermore, deletion of the cytoplasmic tails of both HA and NA has drastic effects on virus morphology (29) and genome packaging in virions (69). The importance of the cytoplasmic tail domains of other transmembrane proteins of influenza A and B viruses, such as NA, M2, and BM2, for virus assembly and budding has also been shown (3, 4, 11, 17, 24, 26, 27, 29, 39–41, 51, 59).

Influenza B virus HA protein (BHA) contains a predicted cytoplasmic tail of 10 amino acids that are highly conserved among influenza B viruses. A previous study using BHA-expressing systems showed that removal of the cytoplasmic tail does not affect BHA expression on the surfaces of BHA-expressing cells, receptor binding activity, or BHA-mediated membrane fusion (62). Unlike the HA of influenza A virus, however, the role of the cytoplasmic tail of BHA in the viral life cycle, in particular the assembly process, has not yet been elucidated. Here, we used reverse genetics to generate a mutant virus lacking the cytoplasmic tail of BHA and examined the impact of this tail deletion on virus infectivity and incorporation of viral proteins into virions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells.

Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells were grown in Eagle's minimal essential medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS). Human embryonic kidney 293T cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) containing 10% FCS. Stable MDCK cell lines expressing wild-type BHA protein (MDCK/BHA) were established by cotransfecting the plasmid pCDNA3.1neo with pCAGGS/BLeeHA at a ratio of 1:2. Stable MDCK cell clones were selected in medium containing 0.5 mg/ml of Geneticin (Invitrogen) and were screened by using an indirect immunofluorescence assay. MDCK/BHA cells were maintained in DMEM containing 10% FCS.

Plasmid constructs and reverse genetics.

For construction of the BHA protein expression vector, the cDNAs encoding the HA genes of B/Lee/40 (B/Lee) virus were cloned into the eukaryotic expression vector pCAGGS/MCS (47), resulting in pCAGGS/BLeeHA. To generate BHA deletion constructs, mutated BHA genes (Fig. 1) were amplified by inverse PCR from pT7BlueBlunt containing the B/Lee BHA gene and were then digested using BsmBI (primer sequences provided on request). The BsmBI-digested fragment was cloned into the BsmBI sites of RNA expression PolI plasmids, which contain the human RNA polymerase I promoter and the mouse RNA polymerase I terminator (46). All constructs were sequenced to ensure that no unwanted mutations were present. Transfectant influenza viruses were generated as described previously (22). Recombinant viruses were plaque purified on MDCK or MDCK/BHA cells and then amplified in MDCK or MDCK/BHA cells in Opti-MEM I containing 5 μg/ml trypsin.

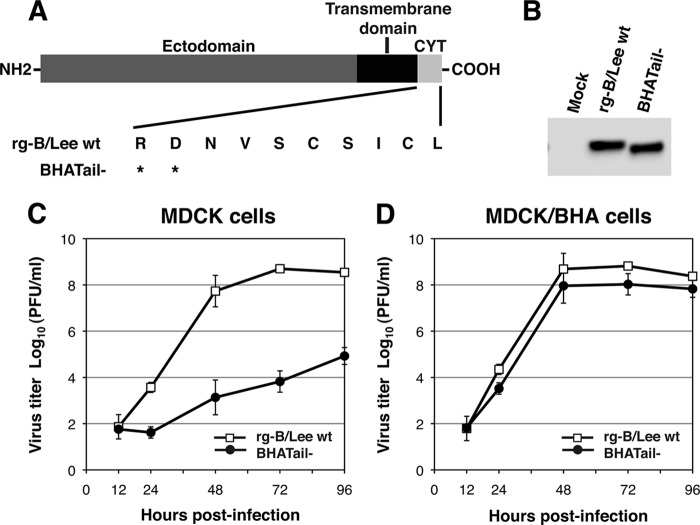

Fig 1.

(A) Schematic diagram of wild-type and mutant BHA proteins carrying a carboxy-terminal truncation in BHA. The amino acid sequence of the BHA cytoplasmic tail (CYT; residues 560 to 569) is shown. An asterisk indicates a stop codon. (B) Detection of BHA protein in BHA truncation mutant virus-infected MDCK cells in the presence of trypsin. MDCK cells were infected with rg-B/Lee wt and BHATail− viruses in the presence of trypsin. BHA proteins in cell lysates were detected by Western blotting using an anti-BHA antibody. (C and D) Growth properties of BHATail− mutant virus. MDCK (C) and MDCK/BHA (D) cells were infected at an MOI of 0.001 PFU, and supernatants of infected cells were harvested at the indicated times. Virus titers in the supernatant were determined by plaque assay on MDCK/BHA cells. The data points represent the means ± standard deviations from triplicate experiments.

Antibodies.

The anti-BHA monoclonal antibody (MAb) B198M and the anti-influenza A virus HA MAb B213M were obtained from Biodesign International. The influenza B virus NA MAb B3 was from QED Bioscience, and the anti-influenza B virus NP MAb INFLB7.1 was from Research Diagnosis. Rabbit polyclonal antiserum against vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) was purchased from Lee BioMolecular Research Laboratories. Goat polyclonal antisera against influenza B virus NA (V312-501-157) and M1 (V307-501-157) were from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and the rabbit polyclonal antiserum to influenza B virus BM2 has been previously described (21). Horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG), HRP-conjugated anti-goat IgG, and HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG were from Zymed.

Preparation of RBCs for fusion assays.

Guinea pig red blood cells (RBCs) were dually labeled as described previously (31). The RBCs were washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and diluted to 50% (vol/vol) in PBS. A 20-μl volume of octadecylrhodamine B chloride (R18; 1 mg/ml in ethanol; Molecular Probes) was added to 0.2 ml of the RBC suspension in 5 ml of PBS under gentle vortexing. After incubation for 30 min at room temperature in the dark, 10 ml of DMEM containing 10% FCS was added to the suspension to remove unbound R18. After further incubation for 20 min at room temperature in the dark, the RBC suspension was washed three times and then resuspended in 2 ml of PBS. R18-labeled RBCs (5% in PBS) were then incubated with 50 μl of calcein acetoxymethylester (calcein-AM) solution (50 μg dissolved in 50 μl of dimethyl sulfoxide; Molecular Probes) at 37°C for 45 min. Subsequently, the suspension was centrifuged and washed in 10 ml of PBS. After resuspension of the pellet in 10 ml of PBS, the cells were incubated at 37°C for 20 min to allow the calcein-AM that was incorporated into the RBCs to be cleaved by cellular esterases, resulting in fluorescent calcein. The suspension of dually labeled RBCs was washed in PBS three times and resuspended to 0.1% in PBS containing 1 mM CaCl2 and 1 mM MgCl2 (PBS++).

Image analysis of fusion events between single RBCs and virus-infected cells.

MDCK cells grown in 35-mm dishes were infected with virus at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 5 PFU per cell and cultured in Opti-MEM I at 33°C for 14 h. The cells were then treated with trypsin (5 μg/ml) in Opti-MEM I for 1 h at 33°C and kept in PBS++ on ice until use. For virus binding, 0.1 ml of labeled RBCs (0.1% in PBS++) was added to virus-infected cells and incubated for 5 min at 4°C. The cells were washed with ice-cold PBS to remove unbound RBCs. The dish was mounted on a laser scanning microscope (LSM 510; Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) equipped with a Planapochromat 10/0.45-numerical-aperture objective. Capture of time-lapse sequences of the fluorescence images at 4-s intervals was started, and then, to trigger the fusion activity of BHA, PBS++ was replaced with 1 ml of an acidic buffer (145 mM NaCl, 20 mM sodium citrate, pH 5.2). Green fluorescence upon excitation with a 488-nm Ar laser was imaged by using a 505- to 530-nm band-pass filter, and red fluorescence upon excitation with a 543-nm HeNe laser was imaged by using a 560-nm-cutoff filter concurrently.

To monitor the fluorescence intensities of individual fusing membranes, the region of interest was set as outlines of fluorescence from RBCs (Fig. 2A). The changes in fluorescence intensity in individual regions were measured with LSM510 software. The response times before the fusion of single RBCs were determined by the timing of the fluorescence increase at more than 100 vesicle regions for each preparation. The kinetics of RBC-cell fusion was obtained from the cumulative sums of the response time distributions.

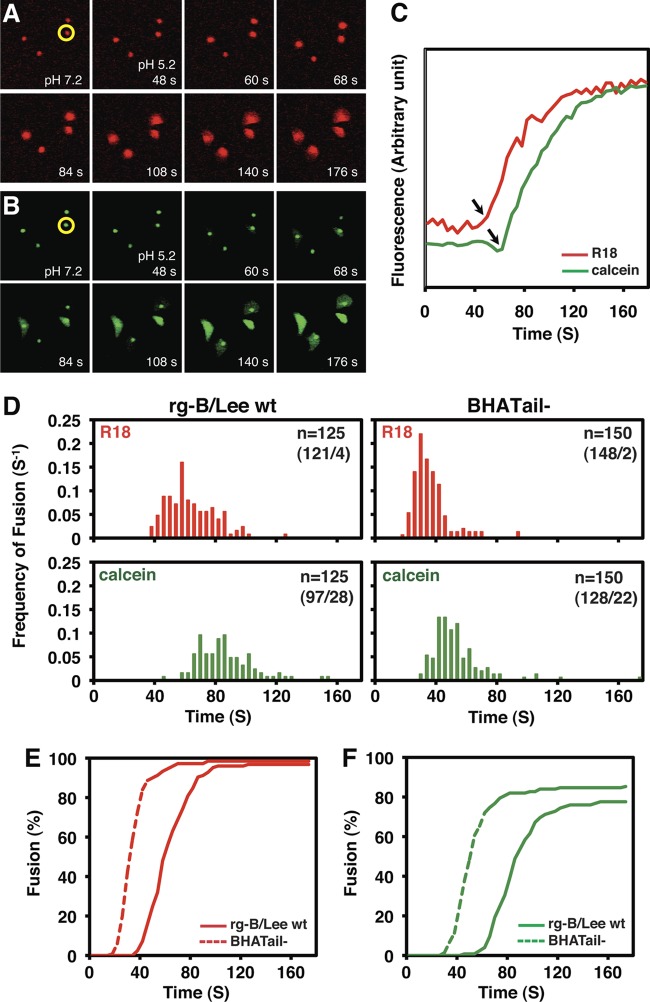

Fig 2.

BHA protein-induced RBC-cell fusion. MDCK cells were infected with rg-B/Lee wt and BHATail− viruses at an MOI of 5 PFU. At 14 h p.i., R18/calcein-labeled RBCs were adsorbed to BHA expressed on the cell surface. Fusion was triggered by transiently shifting the pH to 5.2. (A and B) Time-lapse sequences of fluorescence images of RBCs and virus-infected cells during membrane fusion. Fluorescence images of the RBCs bound to virus-infected cells were captured before and after low-pH treatment at pH 5.2 and 23°C. (A) Time-lapse sequence of red fluorescence (R18) images. (B) Time-lapse sequence of green fluorescence (calcein) images. Both red and green fluorescence was initially located only in the RBC regions but became diffusely distributed over regions of the infected cells after the induction of fusion. (C) Changes in intensity of red (R18) and green (calcein) fluorescence at a single RBC-cell complex during membrane fusion. Fluorescence intensities at the single RBC region (panels A and B, circled in yellow) were plotted. Time zero corresponds to the pH shift. The arrows indicate the time points at which lipid mixing or content mixing started, that is, the response time for single-RBC fusion. (D) Response time distributions of red (R18) and green (calcein) fluorescence increase in wild-type and BHATail− virus-infected cells. Red and green fluorescence intensities at individual RBCs were measured as in panel C to determine the response times for RBC-cell fusion. “n” in each box denotes the number of RBCs examined, with the number of fused RBCs/number of nonfused RBCs within 176 s in parentheses. The vertical axis represents the frequency of fusion for one RBC per 4 s (fusion/RBC/4s). (E and F) Kinetics of fusion in the wild-type and BHATail− virus-infected cells. The kinetics of RBC-cell fusion were obtained by cumulative summation of the data in Fig. 2D.

Western blotting.

Western blot analysis was performed as previously described (24), with modifications. MDCK cells were infected with virus at an MOI of 5 PFU and incubated at 33°C. At various times postinfection (p.i.), cells were lysed in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100 [TX-100], 0.5% deoxycholate, and 0.05% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS]) and maintained for 30 min on ice. After clarification by centrifugation, the supernatant was dissolved in SDS sample buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 6.8], 5% 2-mercaptoethanol, 2% SDS, 10% glycerol, and bromophenol blue) at 95°C for 5 min, resolved by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE), electroblotted, and probed with antibody. The immunoreactive proteins were visualized by using species-specific secondary antibodies coupled to HRP and an enhanced chemiluminescence system (GE Healthcare Life Sciences). The chemiluminescence signal on the membranes was detected by using a FluorChem HD2 (Alpha Innotech) and analyzed by measuring the integrated density of each band with Image J.

Analysis of the protein composition of virions.

MDCK cells were infected with wild-type or mutant viruses at an MOI of 5 PFU and cultured in Opti-MEM I at 33°C. At 26 h p.i., supernatants from cell culture were harvested and clarified by low-speed centrifugation for 10 min at 4°C. Virions were purified by centrifugation through 30% sucrose in a SW41 Ti rotor at 35,000 rpm for 1 h at 4°C, and the virus pellet was disrupted with SDS sample buffer. Viral proteins were analyzed by means of SDS-PAGE and detected by using Coomassie brilliant blue staining and Western blotting using an anti-BM2 antibody. The profiles of the stained gels were digitized and were quantified by using Image J.

Electron microscopy.

A droplet of purified virions was placed on a 400-mesh copper grid coated with Formvar (Electron Microscopy Sciences) and then negatively stained with 1% uranyl acetate. Images were obtained with an H-7600 transmission electron microscope (Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan) operated at 80 kV.

Cell ELISA analysis.

Expression of viral glycoproteins at the cell surface was quantified by cell enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) as described previously, with modifications (49). Briefly, MDCK cells grown in 96-well plates were infected with wild-type or mutant virus at an MOI of 5 PFU and incubated at 33°C. At the indicated times p.i., cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature. The plates were then blocked with 10% goat serum in PBS at room temperature for 2 h. The blocked plates were incubated with an anti-BHA MAb or anti-NA MAb for 2 h. The plates were washed with PBS and then incubated for 2 h with HRP-conjugated anti-mouse IgG. The plates were again washed with PBS, and HRP activity was detected by using the SuperSignal ELISA Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate (Pierce). The chemiluminescent signal was detected by using a Glomax 96 Luminometer (Promega), and the average of triplicate samples was calculated. To determine relative BHA and NA protein surface expression levels, parallel samples were permeabilized with 0.1% TX-100 and incubated with an anti-NP MAb for 2 h, and HRP activity was detected. The BHA and NA protein levels were normalized to the level of NP expression measured in parallel samples that were permeabilized.

TX-100 solubility.

TX-100 solubility was examined as described previously, with modifications (57). MDCK cells grown on 6-cm dishes were infected with viruses at an MOI of 5. At 15 h p.i., the cell monolayer was washed three times with ice-cold PBS and biotinylated for 30 min with 1 mg/ml sulfosuccinimidyl-6-[biotin-amido]hexanoate (Sulfo-NHS-LC-Biotin; Pierce) in PBS++ at 4°C. The cells were then washed three times with PBS containing 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA), scraped into ice-cold PBS, pelleted, and extracted on ice with 0.5 ml of 0.2% TX-100 in TNE buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA) containing protease inhibitors at final concentrations of 1.04 mM aminoethyl-benzene sulfonyl fluoride, 0.8 μM aprotinin, 20 μM leupeptin, 40 μM bestatin, 15 μM pepstatin A, and 14 μM E-64. After 10 min, the supernatant was collected as the soluble fraction. The pellet containing TX-100-insoluble materials was resuspended in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.2% TX-100, 1.0% deoxycholate, and 0.1% SDS) plus protease inhibitors and incubated for 30 min on ice. After incubation, the cells were disrupted by repeated passage (20 times) through a 23-gauge needle. Unbroken cells and nuclei were removed by centrifugation. Both soluble and insoluble biotinylated proteins were immunoprecipitated with streptavidin-agarose (Pierce) and analyzed by use of SDS-PAGE.

RESULTS

Generation of influenza B virus mutants with a deleted BHA cytoplasmic tail domain by using reverse genetics.

To explore the functional role of the cytoplasmic tail of BHA in the replication cycle of influenza B virus, we generated an influenza B virus possessing BHA with a 10-amino-acid truncation from the carboxy-terminal end, BHATail− (Fig. 1A), by using reverse genetics with BLee virus as described previously (22). To rescue the BHATail− mutant virus, a Pol I plasmid encoding the viral RNA (vRNA) for the truncated BHA cytoplasmic tail, together with 7 Pol I plasmids encoding the remaining viral RNAs, was transfected into 293T cells, together with 4 protein expression plasmids (PB1, PB2, PA, and NP). The supernatant harvested at 48 h posttransfection was then inoculated into MDCK cells to amplify transfectants. After 3 days of incubation, an extensive cytopathic effect (CPE) was observed in cells inoculated with the transfectants of B/Lee wild-type virus (rg-B/Lee wt), whereas no CPE was detected in cells inoculated with those of the BHATail− mutant. This result suggests that the cytoplasmic tail of BHA may be required for efficient virus replication and that trans-supplementation of wild-type BHA protein would be necessary to recover the mutant. We therefore established an MDCK cell line, MDCK/BHA, that constitutively expresses BHA protein (as described in Materials and Methods). For rescue of the BHATail− mutant virus, 12 plasmids, as described above, and the plasmid for the expression of the BHA protein were transfected into 293T cells. The mutant in the culture supernatant was plaque purified and amplified on MDCK/BHA cells for the preparation of working stock viruses. Titers of virus stocks were determined by means of plaque assays on MDCK/BHA cells, and the mutant showed titers similar to that of the rg-B/Lee wt virus (2.8 × 108 and 9.5 × 108 PFU/ml, respectively). By sequencing the HA segment of the mutant, we confirmed that no reversion or additional mutations were present in the segment.

To analyze the synthesis of the BHA2 subunit of the BHATail− mutant, virus-infected cells were incubated in the presence of trypsin to cleave BHA0 to BHA1 and BHA2, and BHA2 was detected by Western blotting using an anti-BHA2 antibody. The results showed that the electrophoretic mobility of the BHA2 subunit of the BHATail− mutant was faster than that of the wild-type BHA2 (Fig. 1B), confirming that the BHATail− mutant virus encodes BHA with a deletion.

We compared the kinetics of virus production in multiple-step growth cycles in the BHATail− mutant and rg-B/Lee wt viruses. MDCK and MDCK/BHA cells were infected with virus at an MOI of 0.001, and virus titers in the supernatant were measured by using plaque assays on MDCK/BHA cells. In MDCK cells, growth of the mutant was extremely low and the yield at 72 h p.i. was approximately 5 log units less than that of rg-B/Lee wt virus (Fig. 1C), whereas in MDCK/BHA cells, the mutant virus grew similarly to the rg-B/Lee wt, yielding only a slightly lower titer than the wild-type virus (Fig. 1D). These results indicate that the 10 amino acids at the carboxy-terminal end play a critical role in infectious virus production.

Fusion of the BHA cytoplasmic tail mutant virus with labeled RBCs.

A previous study using BHA-expressing cells showed that deletion of the BHA cytoplasmic tail does not affect its fusion activity (62). To test whether the BHA cytoplasmic tail is required for membrane fusion in the context of a viral infection, we measured low-pH-triggered fusion of virus-infected cells with guinea pig RBCs labeled with a lipid probe (R18), as well as a water-soluble probe (calcein). The labeled RBCs were allowed to adhere to the surfaces of infected cells, and the fusion reaction was induced by transiently lowering the pH to 5.2. Time-lapse sequences of green (i.e., calcein) and red (i.e., R18) fluorescence images were captured simultaneously by means of fluorescence microscopy. In Fig. 2A and B, the time-lapse sequences of the fluorescence images of the RBC-cell complexes are shown for wild-type viruses at pH 5.2 and 23°C. Individual RBCs were discerned as punctate green or red fluorescence at pH 7.2, whereas the virus-infected cells bound to the RBCs were invisible. Redistribution of both green and red fluorescence from RBCs into virus-infected cells was observed after a low-pH trigger, indicating that aqueous content mixing of calcein and lipid mixing of R18 were induced between the virus-infected cells and the RBCs. Under control conditions at pH 7.2, redistribution of neither green nor red fluorescence was observed (data not shown). These results indicate that the dye transfer of both R18 and calcein was due to the low-pH-dependent activity of BHA.

To examine the time course of the fusion events at single RBCs, the time-lapse sequences of the fluorescence images of the RBC-cell complexes, such as those shown in Fig. 2A and B, were analyzed quantitatively. Fluorescence intensities were measured around the RBC. Figure 2C shows the typical time courses of the green and red fluorescence intensities observed in the same single RBCs. During the fluorescence redistribution from RBCs to cells, abrupt fluorescence increases were recorded with both green and red emissions. The increases were ascribed to fluorescence dequenching of the probes due to the lipid and aqueous content mixing between the RBCs and the virus-infected cells upon fusion, similar to the previously observed increase in fluorescence of R18/calcein dually labeled HA-reconstituted vesicles fusing with RBC membranes (25). We defined the interval between the low-pH triggers and the fluorescence increases as the response time preceding the onset of fusion. In most cases, the response time for the red fluorescence increase was shorter than that for the green fluorescence increase, as shown in Fig. 2C, indicating that lipid mixing of R18 typically preceded the aqueous content mixing of calcein.

To quantitatively analyze the RBC-cell fusion events, we determined the response times at hundreds of RBCs for wild-type and mutant viruses (Fig. 2D). The cumulative sums of the response time distributions in Fig. 2D gave the kinetics of RBC-cell fusion (Fig. 2E and F). The fusion rate (V; fusion [%] per time [s]) was obtained from the steepest slope of the curve of the plot in Fig. 2E and F. The fusion rates of mutant BHA were slightly higher than those of wild-type BHA for both the red (11.1 and 7.4 V, respectively) and green (7.8 and 6.4 V, respectively) fluorescence, suggesting that the mutant BHA protein fused with faster kinetics than those of the wild-type BHA protein at pH 5.2 and 23°C. Otherwise, the extent of fusion measured for mutant BHA was similar to that of wild-type BHA, indicating that truncation of the 10 amino acids at the carboxy-terminal end of the BHA protein does not substantially influence BHA-induced fusion.

Generation of a BHA cytoplasmic tailless virus that replicates almost as efficiently as wild-type virus in MDCK cells.

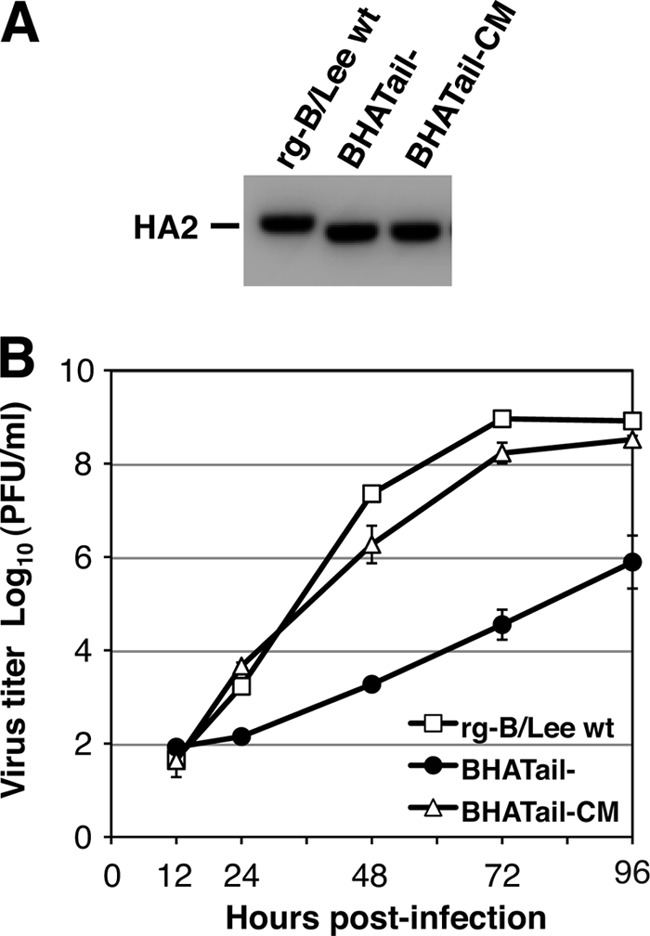

To understand the mechanism by which BHA cytoplasmic truncation negatively affects BHA function, a virus lacking the BHA cytoplasmic tail was subjected to serial passage. The supernatants of 293T cells transfected with 12 plasmids, as mentioned above, were inoculated into MDCK cells, and the culture was monitored for 7 days for CPE due to the propagation of influenza B virus. CPE was detected on day 7 p.i. on the first passage, and viruses from the culture were plaque purified on MDCK cells. Since HA interacts with the NA and M1 proteins (52, 64), the nucleotide sequences of the BHA, NA, and M gene segments of 3 individual plaques were determined. Sequence analysis of the viruses revealed that all of the plaques possessed four amino acid changes (one in BHA [V380M; V34M in the BHA2 subunit], two in NA [Y446C and Q453R], and one in M1 [E136K]), in addition to the original two stop codon mutations in BHA. To assess the growth properties of a BHA cytoplasmic tailless virus possessing the four additional mutations, a virus stock was prepared by amplifying one of the 3 plaques in MDCK cells. By sequencing, we confirmed that the mutant (designated BHATail-CM) contained the same 6 amino acid changes in the BHA, NA, and M1 proteins (Table 1). No changes in the remaining viral proteins were detected compared with the wild-type virus sequences. We next examined whether BHATail-CM synthesized a truncated BHA. As expected, the BHATail-CM virus synthesized a truncated BHA2 subunit in infected-MDCK cells, and no differences in the molecular mass of the BHA between the BHATail− and BHATail-CM viruses were detected (Fig. 3A). The efficiencies of replication of the wild-type and mutant (BHATail− and BHATail-CM) viruses were then compared in a multiple-step growth cycle in MDCK cells (Fig. 3B). The BHATail-CM virus replicated more rapidly and reached significantly higher titers than the BHATail− mutant, although titers at 72 h p.i. were approximately 5-fold lower than that of rg-B/Lee wt virus. Thus, the additional mutations in the BHATail-CM virus appear to improve the replication of a mutant that lacks the cytoplasmic tail of BHA.

Table 1.

Sequence analysis of viruses lacking the BHA cytoplasmic tail obtained after long-term culture of the viruses in MDCK cellsa

| Virus | Amino acid or codon at position: |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BHA |

NA |

M1 136 | ||||

| 380 (BHA2 34) | 560 (BHA2 214) | 561 (BHA2 215) | 446 | 453 | ||

| rg-B/Lee wt | V | R | D | Y | Q | E |

| BHATail− | V | Stop | Stop | Y | Q | E |

| BHATail-CM | M | Stop | Stop | C | R | K |

A Pol I plasmid encoding viral RNA for the BHA truncated cytoplasmic tail, together with 7 Pol I plasmids encoding the remaining viral RNAs, was transfected into 293T cells, together with 4 protein expression plasmids (PB1, PB2, PA, and NP). The supernatant was inoculated into MDCK cells, and the culture was monitored for 7 days for CPE due to propagation of influenza B virus. CPE was detected on day 7 p.i. on the first passage; viruses from the culture were plaque purified and propagated on MDCK cells.

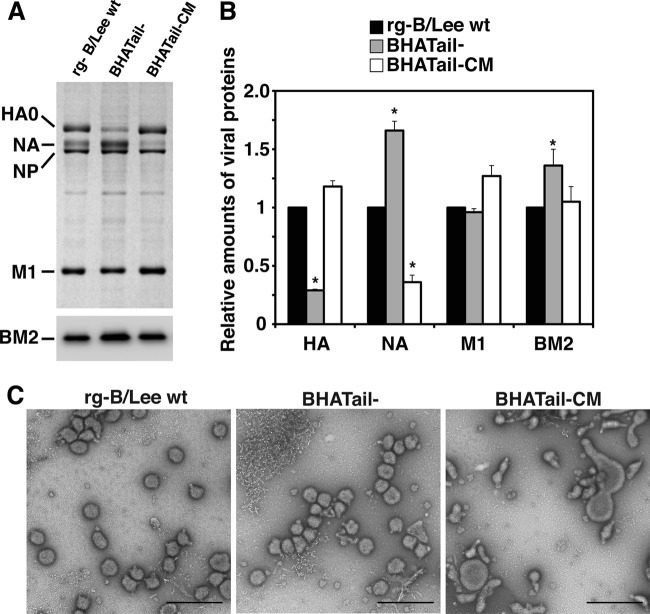

Fig 3.

Characterizations of BHA cytoplasmic tailless viruses with additional mutations. (A) Detection of BHA protein in BHA truncation mutant virus-infected MDCK cells. MDCK cells were infected with rg-B/Lee wt, BHATail−, or BHATail-CM virus in the presence of trypsin. BHA proteins in cell lysates were detected by Western blotting using an anti-BHA antibody. (B) Multiple-step growth curve of BHA mutant viruses. MDCK cells were infected at an MOI of 0.001 PFU, and culture medium was harvested at the indicated times. Virus yields from the supernatants were determined by plaque assay on MDCK/BHA cells. The data points represent the means ± standard deviations from triplicate experiments.

Analysis of the virion of BHA cytoplasmic tailless mutants.

To gain further insights into the effects of the BHA cytoplasmic tail deletion on replication, we examined the protein compositions of purified virions. MDCK cells were infected with rg-B/Lee wt, BHATail−, or BHATail-CM virus at an MOI of 5 for 26 h, and virions in the supernatant were pelleted through a 30% sucrose cushion by ultracentrifugation. The virions were lysed and subjected to SDS-PAGE, followed either by gel staining with Coomassie brilliant blue for BHA, NA, NP, and M1 or by Western blotting for BM2 (Fig. 4A), and quantified. The amounts of BHA, NA, M1, and BM2 proteins were normalized against the NP protein levels in each virus, and the ratios of the amount of each protein in the mutants to those of the corresponding proteins in rg-B/Lee wt virions are presented (Fig. 4B). In the virion of the BHATail− mutant, a dramatic reduction in BHA incorporation was observed, suggesting that removal of the BHA cytoplasmic tail impaired BHA incorporation into the viral particles. On the other hand, the levels of M1 protein were comparable in all virions. Interestingly, the BHATail− virions contained significantly larger amounts of NA and BM2, whereas the NA levels in the BHATail-CM virions were approximately 40% of those in the wild-type virus. These results suggest that the additional mutation(s) in BHA, NA, and/or M1 may cause enhanced BHA incorporation into virions, resulting in a dramatic increase in virus infectivity.

Fig 4.

Analysis of the virions of BHA cytoplasmic tailless mutants. (A and B) Protein composition of BHA mutant virions. MDCK cells were infected at an MOI of 5 PFU, and virions were purified by centrifugation through 30% sucrose. (A) Proteins of purified viruses were analyzed by using Coomassie brilliant blue staining (top) and Western blotting using an anti-BM2 antibody (bottom). (B) Relative amounts of viral proteins. Viral proteins were quantified by using Image J, and the relative staining intensity of each protein was normalized to that of NP for each virus. *, P < 0.05 compared with the value for rg-B/Lee wt. The error bars indicate standard deviations. (C) Morphology of mutants observed under negative-staining electron microscopy. Virions were grown in MDCK cells and purified by centrifugation through 30% sucrose. The virions were negatively stained with 1% uranyl acetate and observed under a transmission electron microscope. Bars, 500 nm.

Studies of influenza A virus have shown that deletion of the cytoplasmic tails of both the HA and NA glycoproteins affects the size and shape of the virus particle, often resulting in the formation of long filamentous structures, although deletion of only the HA cytoplasmic tail does not influence viral morphology (28, 29). To determine whether truncation of the BHA cytoplasmic tail alters morphogenesis in BLee virus particles, MDCK cells were infected with mutant viruses at an MOI of 5 for 26 h, and virions were purified and examined under negative-staining electron microscopy (Fig. 4C). BHATail− virions exhibited roughly spherical morphology with a diameter similar to that of rg-BLee wt virions, even though the mutant did not contain appreciable amounts of BHA. In contrast, BHATail-CM virus particles showed a different morphological phenotype; the virions were elongated and irregularly shaped. Lower expression of the NA protein at the cell surface may contribute to the morphological change in BHATail-CM virions, as shown by others (68).

Synthesis of BHA and NA proteins in cells infected with BHA cytoplasmic tail mutants.

The reduced levels of BHA in BHATail− and NA in BHATail-CM virions may have been due to decreased expression of these proteins in virus-infected cells. To examine this possibility, the surface and total expression levels of the BHA and NA proteins in virus-infected MDCK cells were analyzed by cell ELISA and Western blotting, respectively, at 11, 15, and 19 h p.i. The expression levels of both proteins were normalized to that of the NP protein. While the amounts of BHA protein expressed on the cell surface were comparable in BHATail− and rg-B/Lee wt viruses, as seen by cell ELISA analysis, the BHA protein of the BHATail-CM virus was expressed more abundantly than that of the wild-type virus (Fig. 5A). Western blot analysis of cell lysates showed that total BHA protein levels were similar for the different viruses (Fig. 5B). These results indicate that truncation of the 10 amino acids from the carboxy-terminal end of the BHA protein does not significantly affect the biosynthesis or the transport of the mutant BHA protein, confirming previously published results (62). Although the NA protein of BHATail− virus was expressed on the cell surface at a higher level than that of the wild-type virus, the total levels of NA were similar. In contrast, the amounts of the NA protein on the surfaces of BHATail-CM virus-infected cells were significantly reduced at all times compared with those of wild-type virus-infected cells. In Western blot assays, the NA protein of BHATail-CM virus showed higher electrophoretic mobility than the wild-type virus and its total expression levels were lower. These results suggest that a mutation(s) at positions 446 and/or 453 in NA that affect the folding and/or stability of NA may cause a marked decrease in the cell surface expression of NA, thereby contributing to the reduced levels of NA incorporation into BHATail-CM virions.

Fig 5.

Comparison of the amounts of viral glycoproteins expressed in virus-infected MDCK cells. (A) Surface expression of BHA and NA proteins. Infected MDCK cells were fixed with paraformaldehyde at the indicated times p.i. and permeabilized with TX-100 for the detection of NP or left untreated for the detection of BHA and NA on the cell surface. Viral glycoprotein levels were analyzed by means of a cell ELISA using anti-BHA and anti-NA antibodies. The amounts of BHA and NA proteins were normalized to that of the NP protein of each mutant virus. The amounts of BHA and NA in the wild-type virus were set to 100%, and the amounts of both proteins in the mutants are shown relative to that of the wild-type virus. The error bars indicate standard deviations. (B) Total expression of BHA and NA proteins. Infected MDCK cells were lysed at the indicated times p.i., and viral glycoprotein in cell lysates was detected by Western blotting using anti-BHA and anti-NA antibodies. Viral proteins were quantified by using Image J, and the relative staining intensity of each protein was normalized to that of the NP protein of each virus.

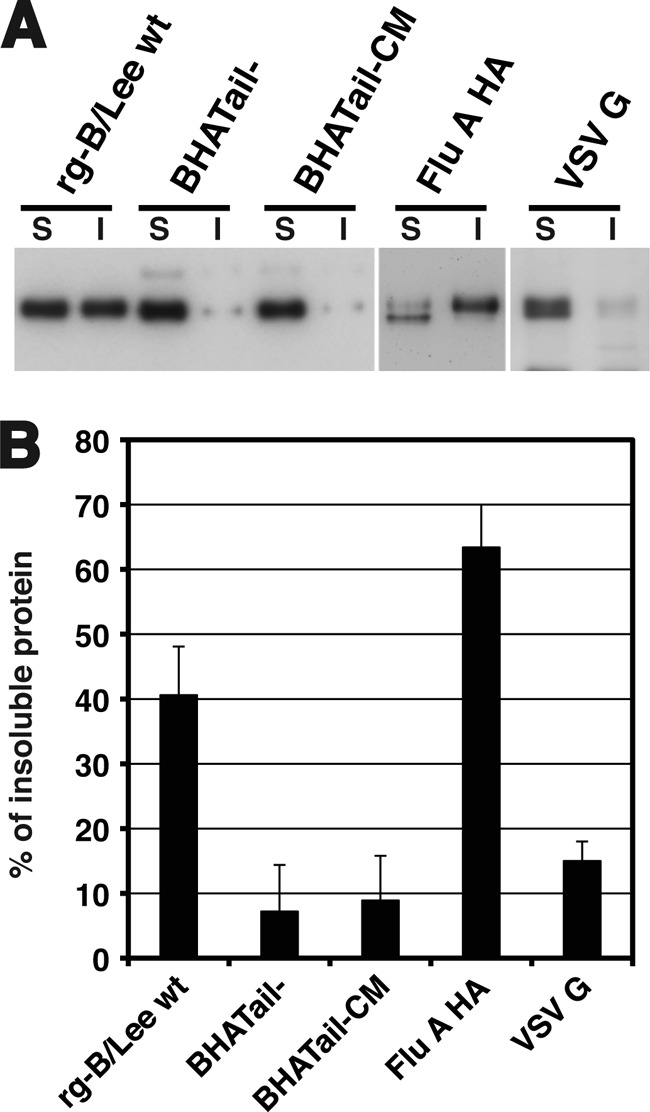

A role for the cytoplasmic tail of BHA in BHA protein-lipid raft association.

A previous study has suggested that the HA of influenza A viruses associates with low-density plasma membrane domains known as lipid rafts and that truncation of the HA cytoplasmic tail affects the lipid raft association of HA (70). Lipid rafts contain high levels of sphingolipids and cholesterol and can be isolated due to their resistance to solubilization with cold nonionic detergents (e.g., TX-100). To determine whether truncation of the BHA cytoplasmic tail alters the lipid raft association of BHA, the TX-100 solubility of the BHA of rg-B/Lee wt, BHATail−, and BHATail-CM viruses was examined, together with known raft- and non-raft-associated proteins, that is, influenza A virus HA and VSV G, respectively. The surfaces of virus-infected cells were biotinylated, and proteins on the surface were extracted with 0.2% TX-100 on ice. Detergent-soluble and insoluble fractions were separated by centrifugation, and biotinylated proteins from both fractions were collected. Consistent with previous reports (57, 70), influenza A virus HA was mainly detected in the insoluble fractions extracted by TX-100 on ice, whereas only small amounts of VSV G were found in the insoluble fraction (Fig. 6A). In cells infected with rg-B/Lee wt virus, approximately 40% of the BHA was associated with the insoluble fraction (Fig. 6B). In contrast, in cells infected with BHATail− and BHATail-CM mutants, only 7% and 8% of the mutant BHA proteins, respectively, were in the insoluble fraction. These results indicate that the wild-type BHA protein is resistant to TX-100 extraction at low temperature, whereas in the absence of the cytoplasmic tail, BHA becomes sensitive to TX-100 extraction, suggesting the importance of the cytoplasmic tail in the lipid raft association of the BHA protein.

Fig 6.

Effect of the cytoplasmic tail deletion on BHA protein-lipid raft association. (A) TX-100 solubility of the wild-type and mutant BHA proteins in virus-infected cells. MDCK cells were infected at an MOI of 5 PFU. After 15 h, the cells were surface biotinylated and then incubated with lysis buffer (0.2% TX-100, 50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA) on ice for 10 min. The soluble (S) and insoluble (I) fractions were separated by centrifugation, and the insoluble fraction was homogenized by passage through a 25-gauge needle 20 times. Both fractions were immunoprecipitated and analyzed by use of SDS-PAGE. (B) The relative intensities of the viral proteins found in the insoluble and soluble fractions were quantified by using Image J. The error bars indicate standard deviations.

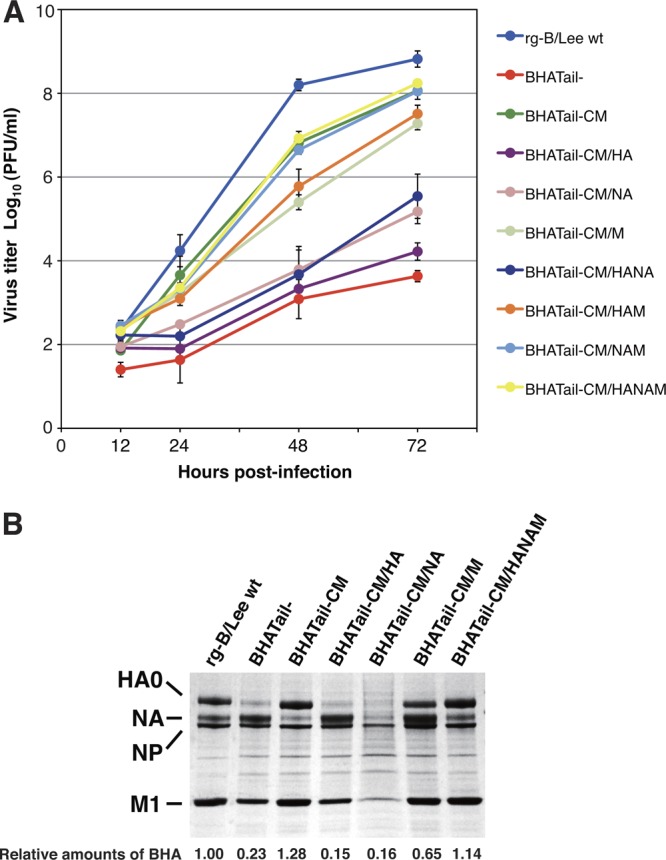

Identification of compensatory mutations that enhance the growth of a BHA cytoplasmic tailless virus.

As described above, the virus lacking the BHA cytoplasmic tail (BHATail−) replicated poorly in MDCK cells, whereas the BHA cytoplasmic tailless virus possessing four additional mutations in its BHA, NA, and M1 proteins (BHATail-CM) was restored to nearly wild-type levels of replication (Fig. 3). To define the responsible mutation(s) for the improved replication of BHATail-CM virus, we generated BHA cytoplasmic tailless viruses encoding the additional mutations in BHA, NA, and M1 individually and in various combinations on the wild-type virus background and characterized their replication in MDCK cells (Fig. 7A). BHA tailless viruses possessing either the BHA V380M mutation or the two NA Y446C/Q453R mutations or both (designated BHATail-CM/HA, BHATail-CM/NA, and BHATail-CM/HANA, respectively) showed a marked growth delay, and their titers at 72 h p.i. were 3 to 4 log units lower than those of BHATail-CM, although the growth of the last two mutants was better than that of the BHATail− virus without the additional mutations. BHA tailless viruses carrying both the BHA V380M and M1 E136K mutations or only the M1 E136K mutation (designated BHATail-CM/HAM or BHATail-CM/M, respectively) replicated to approximately 10-fold-lower titers than did BHATail-CM. In contrast, BHA tailless viruses containing the mutations in the BHA, NA, and M1 proteins or in the NA and M1 proteins (designated BHATail-CM/HANAM or BHATail-CM/NAM, respectively) exhibited growth kinetics indistinguishable from those of BHATail-CM virus. Thus, the mutations in NA (Y446C and/or Q453R) and M1 (E136K) enabled a virus lacking the BHA cytoplasmic tail to replicate more efficiently in MDCK cells, albeit with different efficiencies; however, the BHA V380M mutation did not appear to influence the replication of the mutant.

Fig 7.

(A) Identification of compensatory mutations that contribute to the efficient growth of BHATail-CM mutant virus. Multicycle replication kinetics was determined as described in the legend to Fig. 3B. (B) Protein compositions of mutant virions. Proteins of purified viruses were analyzed by use of Coomassie brilliant blue staining as described in the legend to Fig. 4.

We then analyzed components of the purified mutant virions to determine the relative amounts of BHA incorporation into them. BHATail-CM/HA and BHATail-CM/NA produced virions containing dramatically reduced BHA, as was observed for BHATail− (Fig. 7B). In contrast, the amount of BHA in the BHATail-CM/M virions was approximately 3-fold higher than that in BHATail− virions, although virus particles of BHATail-CM/M contained smaller amounts of BHA than those of the wild-type virus. These data show that the M1 E136K mutation is required for the efficient incorporation of tailless BHA protein into virions.

DISCUSSION

Our studies using virus-infected cells indicate that the cytoplasmic tail of BHA is not required for the membrane fusion activity of BHA, in accordance with previous findings (62). However, we observed that an influenza B virus lacking the BHA cytoplasmic tail, BHATail−, exhibited extreme attenuation of growth. Notably, this mutant produced virus particles containing dramatically reduced BHA levels. Studies of influenza A virus have shown that the fusion activity of individual HA-containing vesicles is dependent on their surface density of HA proteins (20, 25). In addition, the receptor binding efficiency of virus particles to cells may also vary, depending on the surface density of HA on the virions. Our findings suggest that a decrease in BHA density at the virion surface, as a result of deletions of the BHA cytoplasmic tail domain that impair BHA incorporation into virions, may reduce the fusogenic and binding activities of the virus particles, thereby resulting in a loss of viral infectivity.

Interestingly, we obtained a virus lacking the BHA cytoplasmic tail, BHATail-CM, that grew almost as well as the wild-type virus in MDCK cells. The BHATail-CM virus retained its BHA cytoplasmic tail deletion but acquired additional mutations: one in BHA (V380M), two in NA (Y446C and Q453R), and one in M1 (E136K). Growth kinetics in MDCK cells of BHA tailless viruses possessing one or more of these additional mutations suggested that the E136K mutation in M1 may play a role in the efficient incorporation of BHA protein lacking the tail into particles, leading to the restoration of the growth of BHA tailless viruses; the Y446C and/or Q453R mutation in NA also conferred improved growth. Collectively, these results suggest that the BHA cytoplasmic tail is not absolutely essential for virus replication in cultured cells.

The HA cytoplasmic tail of influenza A virus is believed to associate with the M1 protein (1, 15, 32, 70). This may indicate that the incorporation of HA into virions is mediated by interactions between the cytoplasmic tail and the M1 protein, because M1 regulates the assembly and budding of viral particles (45). However, an HA protein lacking the entire cytoplasmic domain was effectively incorporated into budding virions (28, 29). In addition, a recent study demonstrated that when HA-expressing cells were treated with exogenous bacterial NA, HA alone could induce the budding and release of HA protein-containing particles, suggesting that HA is incorporated into virus particles without the aid of other viral proteins (12). In the case of human immunodeficiency virus, on the other hand, specific interactions between the cytoplasmic tail of the glycoproteins and the matrix protein are necessary for incorporation of the glycoprotein into virions (16, 43, 67). In this study, we observed that the E136K mutation in M1 improved incorporation of tailless BHA protein into virions and the replication of viruses bearing the mutant BHA, raising the possibility that the putative BHA-M1 interaction is involved in the efficient incorporation of BHA at the virion budding site during virus assembly. Interestingly, in the three-dimensional model of influenza A virus M1 protein (residues 1 to 164) (58), residue 136 is exposed at the surface of the molecule and is located proximal to the 101-RKLKR-105 sequence, which plays an important role in the virus assembly process (8, 35, 36). Although a BHA-M1 interaction has not been observed, the M1 mutation may be necessary to restore the interaction between M1 and tailless BHA, possibly through a direct interaction with the transmembrane domain of BHA. Alternatively, since influenza A virus M1 protein has lipid-binding properties (6, 19, 53), the mutation might alter the interaction between M1 and the plasma membrane. The altered membrane association of M1 may play a role in the efficient incorporation of tailless BHA into virions. Further investigations are required to define the role of the M1 mutation in incorporation of tailless BHA protein into virions.

The NA protein of influenza viruses cleaves sialic acids from receptors on cellular and viral surfaces to facilitate virus entry and budding (34, 50, 60). Due to the antagonistic functions of HA and NA, the interplay between the activities of HA and NA in influenza virus particles must be optimal for efficient attachment to cells during the initial stages of infection. A recent study of influenza A virus reported that the balance between HA and NA activities is important for virus entry into cells, as well as for the release of virus particles from the infected cell surface (13). In virions of the BHATail− mutant that grew poorly, the incorporation of NA increased, but BHA tailless protein incorporation was decreased compared with the wild-type virus (Fig. 4), suggesting that mutant viruses with a very low BHA/NA ratio on the surface are unable to bind efficiently to cells due to an imbalance between the BHA and NA activities. In influenza A viruses, numerous studies have shown that compensatory mutations in HA, NA, or both proteins can modulate the functional balance between HA and NA (2, 18, 23, 30, 42, 64, 65). In this study, we found that a BHA cytoplasmic tailless mutant carrying two NA mutations, BHATail-CM/NA, replicated better than did BHATail− without the mutations (Fig. 7). Although we have yet to examine the role of the NA mutations in viral replication, the mutation(s) was associated with low-level expression of NA on the cell surface (Fig. 5A), likely resulting in reduced amounts of NA in the budding virions. The mutation(s) in NA might therefore regulate the balance between the HA and NA activities of virus particles containing decreased levels of BHA by reducing NA incorporation per virion, thereby allowing the BHATail-CM/NA virus to bind to cells with higher efficiency than BHATail− virus.

Our data indicate that the cytoplasmic tail is required for the tight association of the BHA protein with lipid raft microdomains, as measured by the TX-100 insolubility of cell surface BHA (Fig. 6). Since influenza A virus HA is incorporated into virions during budding from the microdomains of the plasma membrane (56, 61), the reduced raft association of BHA may be a contributing factor causing the decreased BHA incorporation into virions. However, in the case of the BHATail-CM virus, despite the lack of raft association, the mutant BHA protein was incorporated into virions at levels comparable to those of the BHA protein in the wild-type virus. Similar evidence has been obtained for influenza A virus, where mutations in the HA cytoplasmic tail markedly reduced raft association but did not affect HA incorporation into virions (63). Thus, it is likely that reduced raft association is not responsible for BHA incorporation into virions.

Influenza A virus HA and BHA are posttranslationally modified by the addition of palmitate to the two cysteine residues located in their cytoplasmic tails through a thioester bond. In the case of influenza A virus, removal of the cysteine palmitoylation signals, located in the cytoplasmic tail, does not abolish HA incorporation into virions (63). Also, deletion of the cytoplasmic tail that causes elimination of palmitoylation does not affect HA incorporation into virus particles (28). In contrast, removal of palmitoylation by deletion of the BHA cytoplasmic tail decreases BHA incorporation into virions (Fig. 4). However, we observed that in the BHATail-CM virus, deletion of the BHA cytoplasmic tail had no effect on BHA incorporation. These observations suggest that the palmitoylation of the BHA cytoplasmic tail may not be critical for BHA incorporation into viral particles.

Studies of influenza A virus have shown that specific nucleotide residues at both the 5′ and 3′ ends of the HA open reading frame (ORF) are necessary for efficient incorporation of the vRNA segment into virions (37, 66). Thus, it is possible that the mutations introduced into the 5′ coding ends of the BHA segment of BHATail− virus disrupt packaging signals, resulting in reduced viral replication. However, we found that BHATail-CM virus, whose HA is identical to that of BHATail−, exhibited growth kinetics almost identical to those of rg-B/Lee wt virus (Fig. 3B). Thus, it is unlikely that the mutations we introduced in the HA gene affected BHA segment incorporation.

Observations made by using negative-stain electron microscopy showed that BHATail-CM virus produced particles with a wide range of sizes that were heterogeneous in shape. A temperature-sensitive mutant of influenza B virus that is defective in both transport of NA to the cell surface and virus morphogenesis at the nonpermissive temperature possesses amino acid changes at positions 237, 395, 458, and 463 in NA (68). We found that the amount of NA with the mutations Y446C and Q453R expressed during BHATail-CM virus infection was dramatically reduced on the surfaces of virus-infected cells and that these mutations are located proximal to amino acids 458 and 463 in the NA crystallographic structure (9). These data suggest that changes at these NA positions may result in decreased NA expression on the cell surface, leading to significant changes in virus particle morphology. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that the concomitant E136K change in M1 also affects the morphology of the budded viruses, because the M1 protein of influenza A virus is known to modulate virus particle morphology (5, 8, 14).

In summary, the cytoplasmic tail domain of BHA is important for the efficient incorporation of BHA into virions and for tight lipid raft association of BHA, suggesting that it has important roles in influenza B virus replication. Our data further suggest that this domain is not absolutely required for the productive growth of influenza B virus in tissue culture in the presence of compensatory mutations.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Takato Odagiri for providing MDCK cells. We also thank Martha McGregor, Rebecca Moritz, Lisa Burley, and Kelly Moore for technical support and Susan Watson for editing the manuscript.

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health; by a Grant-in-Aid for Specially Promoted Research; by a contract research fund for the Program of Founding Research Centers for Emerging and Reemerging Infectious Diseases from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology; by grants-in-aid from the Ministry of Health; and by ERATO (Japan Science and Technology Agency).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 15 August 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Ali A, Avalos RT, Ponimaskin E, Nayak DP. 2000. Influenza virus assembly: effect of influenza virus glycoproteins on the membrane association of M1 protein. J. Virol. 74:8709–8719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Baigent SJ, McCauley JW. 2001. Glycosylation of haemagglutinin and stalk-length of neuraminidase combine to regulate the growth of avian influenza viruses in tissue culture. Virus Res. 79:177–185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Barman S, et al. 2004. Role of transmembrane domain and cytoplasmic tail amino acid sequences of influenza A virus neuraminidase in raft association and virus budding. J. Virol. 78:5258–5269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bilsel P, Castrucci MR, Kawaoka Y. 1993. Mutations in the cytoplasmic tail of influenza A virus neuraminidase affect incorporation into virions. J. Virol. 67:6762–6767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bourmakina SV, Garcia-Sastre A. 2003. Reverse genetics studies on the filamentous morphology of influenza A virus. J. Gen. Virol. 84:517–527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bucher DJ, et al. 1980. Incorporation of influenza virus M-protein into liposomes. J. Virol. 36:586–590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bullough PA, Hughson FM, Skehel JJ, Wiley DC. 1994. Structure of influenza haemagglutinin at the pH of membrane fusion. Nature 371:37–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Burleigh LM, Calder LJ, Skehel JJ, Steinhauer DA. 2005. Influenza a viruses with mutations in the m1 helix six domain display a wide variety of morphological phenotypes. J. Virol. 79:1262–1270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Burmeister WP, Ruigrok RW, Cusack S. 1992. The 2.2 Å resolution crystal structure of influenza B neuraminidase and its complex with sialic acid. EMBO J. 11:49–56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Carr CM, Kim PS. 1993. A spring-loaded mechanism for the conformational change of influenza hemagglutinin. Cell 73:823–832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chen BJ, Leser GP, Jackson D, Lamb RA. 2008. The influenza virus M2 protein cytoplasmic tail interacts with the M1 protein and influences virus assembly at the site of virus budding. J. Virol. 82:10059–10070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chen BJ, Leser GP, Morita E, Lamb RA. 2007. Influenza virus hemagglutinin and neuraminidase, but not the matrix protein, are required for assembly and budding of plasmid-derived virus-like particles. J. Virol. 81:7111–7123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. de Vries E, et al. 2012. Influenza A virus entry into cells lacking sialylated N-glycans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 109:7457–7462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Elleman CJ, Barclay WS. 2004. The M1 matrix protein controls the filamentous phenotype of influenza A virus. Virology 321:144–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Enami M, Enami K. 1996. Influenza virus hemagglutinin and neuraminidase glycoproteins stimulate the membrane association of the matrix protein. J. Virol. 70:6653–6657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Freed EO, Martin MA. 1996. Domains of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 matrix and gp41 cytoplasmic tail required for envelope incorporation into virions. J. Virol. 70:341–351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Garcia-Sastre A, Palese P. 1995. The cytoplasmic tail of the neuraminidase protein of influenza A virus does not play an important role in the packaging of this protein into viral envelopes. Virus Res. 37:37–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ginting TE, et al. 2012. Amino acid changes in hemagglutinin contribute to the replication of oseltamivir-resistant H1N1 influenza viruses. J. Virol. 86:121–127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gregoriades A, Frangione B. 1981. Insertion of influenza M protein into the viral lipid bilayer and localization of site of insertion. J. Virol. 40:323–328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gunther-Ausborn S, Schoen P, Bartoldus I, Wilschut J, Stegmann T. 2000. Role of hemagglutinin surface density in the initial stages of influenza virus fusion: lack of evidence for cooperativity. J. Virol. 74:2714–2720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hatta M, Goto H, Kawaoka Y. 2004. Influenza B virus requires BM2 protein for replication. J. Virol. 78:5576–5583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hatta M, Kawaoka Y. 2003. The NB protein of influenza B virus is not necessary for virus replication in vitro. J. Virol. 77:6050–6054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hughes MT, Matrosovich M, Rodgers ME, McGregor M, Kawaoka Y. 2000. Influenza A viruses lacking sialidase activity can undergo multiple cycles of replication in cell culture, eggs, or mice. J. Virol. 74:5206–5212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Imai M, Kawasaki K, Odagiri T. 2008. Cytoplasmic domain of influenza B virus BM2 protein plays critical roles in production of infectious virus. J. Virol. 82:728–739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Imai M, Mizuno T, Kawasaki K. 2006. Membrane fusion by single influenza hemagglutinin trimers. Kinetic evidence from image analysis of hemagglutinin-reconstituted vesicles. J. Biol. Chem. 281:12729–12735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Imai M, Watanabe S, Ninomiya A, Obuchi M, Odagiri T. 2004. Influenza B virus BM2 protein is a crucial component for incorporation of viral ribonucleoprotein complex into virions during virus assembly. J. Virol. 78:11007–11015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Iwatsuki-Horimoto K, et al. 2006. The cytoplasmic tail of the influenza A virus M2 protein plays a role in viral assembly. J. Virol. 80:5233–5240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jin H, Leser GP, Lamb RA. 1994. The influenza virus hemagglutinin cytoplasmic tail is not essential for virus assembly or infectivity. EMBO J. 13:5504–5515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Jin H, Leser GP, Zhang J, Lamb RA. 1997. Influenza virus hemagglutinin and neuraminidase cytoplasmic tails control particle shape. EMBO J. 16:1236–1247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kaverin NV, et al. 1998. Postreassortment changes in influenza A virus hemagglutinin restoring HA-NA functional match. Virology 244:315–321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kozerski C, Ponimaskin E, Schroth-Diez B, Schmidt MF, Herrmann A. 2000. Modification of the cytoplasmic domain of influenza virus hemagglutinin affects enlargement of the fusion pore. J. Virol. 74:7529–7537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kretzschmar E, Bui M, Rose JK. 1996. Membrane association of influenza virus matrix protein does not require specific hydrophobic domains or the viral glycoproteins. Virology 220:37–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lakadamyali M, Rust MJ, Babcock HP, Zhuang X. 2003. Visualizing infection of individual influenza viruses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100:9280–9285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Liu C, Eichelberger MC, Compans RW, Air GM. 1995. Influenza type A virus neuraminidase does not play a role in viral entry, replication, assembly, or budding. J. Virol. 69:1099–1106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Liu T, Ye Z. 2004. Introduction of a temperature-sensitive phenotype into influenza A/WSN/33 virus by altering the basic amino acid domain of influenza virus matrix protein. J. Virol. 78:9585–9591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Liu T, Ye Z. 2002. Restriction of viral replication by mutation of the influenza virus matrix protein. J. Virol. 76:13055–13061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Marsh GA, Hatami R, Palese P. 2007. Specific residues of the influenza A virus hemagglutinin viral RNA are important for efficient packaging into budding virions. J. Virol. 81:9727–9736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Martin K, Helenius A. 1991. Transport of incoming influenza virus nucleocapsids into the nucleus. J. Virol. 65:232–244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. McCown MF, Pekosz A. 2006. Distinct domains of the influenza A virus M2 protein cytoplasmic tail mediate binding to the M1 protein and facilitate infectious virus production. J. Virol. 80:8178–8189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. McCown MF, Pekosz A. 2005. The influenza A virus M2 cytoplasmic tail is required for infectious virus production and efficient genome packaging. J. Virol. 79:3595–3605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Mitnaul LJ, Castrucci MR, Murti KG, Kawaoka Y. 1996. The cytoplasmic tail of influenza A virus neuraminidase (NA) affects NA incorporation into virions, virion morphology, and virulence in mice but is not essential for virus replication. J. Virol. 70:873–879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Mitnaul LJ, et al. 2000. Balanced hemagglutinin and neuraminidase activities are critical for efficient replication of influenza A virus. J. Virol. 74:6015–6020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Murakami T, Freed EO. 2000. Genetic evidence for an interaction between human immunodeficiency virus type 1 matrix and alpha-helix 2 of the gp41 cytoplasmic tail. J. Virol. 74:3548–3554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Naeve CW, Williams D. 1990. Fatty acids on the A/Japan/305/57 influenza virus hemagglutinin have a role in membrane fusion. EMBO J. 9:3857–3866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Nayak DP, Hui EK, Barman S. 2004. Assembly and budding of influenza virus. Virus Res. 106:147–165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Neumann G, et al. 1999. Generation of influenza A viruses entirely from cloned cDNAs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96:9345–9350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Niwa H, Yamamura K, Miyazaki J. 1991. Efficient selection for high-expression transfectants with a novel eukaryotic vector. Gene 108:193–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Nobusawa E, et al. 1991. Comparison of complete amino acid sequences and receptor-binding properties among 13 serotypes of hemagglutinins of influenza A viruses. Virology 182:475–485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Oomens AG, Bevis KP, Wertz GW. 2006. The cytoplasmic tail of the human respiratory syncytial virus F protein plays critical roles in cellular localization of the F protein and infectious progeny production. J. Virol. 80:10465–10477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Palese P, Tobita K, Ueda M, Compans RW. 1974. Characterization of temperature sensitive influenza virus mutants defective in neuraminidase. Virology 61:397–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Rossman JS, et al. 2010. Influenza virus m2 ion channel protein is necessary for filamentous virion formation. J. Virol. 84:5078–5088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Rossman JS, Lamb RA. 2011. Influenza virus assembly and budding. Virology 411:229–236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Ruigrok RW, et al. 2000. Membrane interaction of influenza virus M1 protein. Virology 267:289–298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Rust MJ, Lakadamyali M, Zhang F, Zhuang X. 2004. Assembly of endocytic machinery around individual influenza viruses during viral entry. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 11:567–573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Sakai T, Ohuchi R, Ohuchi M. 2002. Fatty acids on the A/USSR/77 influenza virus hemagglutinin facilitate the transition from hemifusion to fusion pore formation. J. Virol. 76:4603–4611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Scheiffele P, Rietveld A, Wilk T, Simons K. 1999. Influenza viruses select ordered lipid domains during budding from the plasma membrane. J. Biol. Chem. 274:2038–2044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Scheiffele P, Roth MG, Simons K. 1997. Interaction of influenza virus haemagglutinin with sphingolipid-cholesterol membrane domains via its transmembrane domain. EMBO J. 16:5501–5508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Sha B, Luo M. 1997. Structure of a bifunctional membrane-RNA binding protein, influenza virus matrix protein M1. Nat. Struct. Biol. 4:239–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Stewart SM, Pekosz A. 2012. The influenza C virus CM2 protein can alter intracellular pH, and its transmembrane domain can substitute for that of the influenza A virus M2 protein and support infectious virus production. J. Virol. 86:1277–1281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Su B, et al. 2009. Enhancement of the influenza A hemagglutinin (HA)-mediated cell-cell fusion and virus entry by the viral neuraminidase (NA). PLoS One 4:e8495 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0008495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Takeda M, Leser GP, Russell CJ, Lamb RA. 2003. Influenza virus hemagglutinin concentrates in lipid raft microdomains for efficient viral fusion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100:14610–14617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Ujike M, Nakajima K, Nobusawa E. 2004. Influence of acylation sites of influenza B virus hemagglutinin on fusion pore formation and dilation. J. Virol. 78:11536–11543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Wagner R, Herwig A, Azzouz N, Klenk HD. 2005. Acylation-mediated membrane anchoring of avian influenza virus hemagglutinin is essential for fusion pore formation and virus infectivity. J. Virol. 79:6449–6458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Wagner R, Matrosovich M, Klenk HD. 2002. Functional balance between haemagglutinin and neuraminidase in influenza virus infections. Rev. Med. Virol. 12:159–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Wagner R, Wolff T, Herwig A, Pleschka S, Klenk HD. 2000. Interdependence of hemagglutinin glycosylation and neuraminidase as regulators of influenza virus growth: a study by reverse genetics. J. Virol. 74:6316–6323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Watanabe T, Watanabe S, Noda T, Fujii Y, Kawaoka Y. 2003. Exploitation of nucleic acid packaging signals to generate a novel influenza virus-based vector stably expressing two foreign genes. J. Virol. 77:10575–10583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Wyma DJ, Kotov A, Aiken C. 2000. Evidence for a stable interaction of gp41 with Pr55(Gag) in immature human immunodeficiency virus type 1 particles. J. Virol. 74:9381–9387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Yamamoto-Goshima F, et al. 1994. Role of neuraminidase in the morphogenesis of influenza B virus. J. Virol. 68:1250–1254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Zhang J, Leser GP, Pekosz A, Lamb RA. 2000. The cytoplasmic tails of the influenza virus spike glycoproteins are required for normal genome packaging. Virology 269:325–334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Zhang J, Pekosz A, Lamb RA. 2000. Influenza virus assembly and lipid raft microdomains: a role for the cytoplasmic tails of the spike glycoproteins. J. Virol. 74:4634–4644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]