Abstract

Phosphatidylinositol-4-kinase IIIα (PI4KIIIα) is an essential host cell factor for hepatitis C virus (HCV) replication. An N-terminally truncated 130-kDa form was used to reconstitute an in vitro biochemical lipid kinase assay that was optimized for small-molecule compound screening and identified potent and specific inhibitors. Cell culture studies with PI4KIIIα inhibitors demonstrated that the kinase activity was essential for HCV RNA replication. Two PI4KIIIα inhibitors were used to select cell lines harboring HCV replicon mutants with a 20-fold loss in sensitivity to the compounds. Reverse genetic mapping isolated an NS4B-NS5A segment that rescued HCV RNA replication in PIK4IIIα-deficient cells. HCV RNA replication occurs on specialized membranous webs, and this study with PIK4IIIα inhibitor-resistant mutants provides a genetic link between NS4B/NS5A functions and PI4-phosphate lipid metabolism. A comprehensive assessment of PI4KIIIα as a drug target included its evaluation for pharmacologic intervention in vivo through conditional transgenic murine lines that mimic target-specific inhibition in adult mice. Homozygotes that induce a knockout of the kinase domain or knock in a single amino acid substitution, kinase-defective PI4KIIIα, displayed a lethal phenotype with a fairly widespread mucosal epithelial degeneration of the gastrointestinal tract. This essential host physiologic role raises doubt about the pursuit of PI4KIIIα inhibitors for treatment of chronic HCV infection.

INTRODUCTION

About 2.4% of the human population, corresponding to about 160 million individuals, is infected with hepatitis C virus (HCV). The vast majority are chronically infected, with sequelae that often lead to serious liver diseases such as cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (42). The new gold standard therapy for chronic genotype 1 HCV infection is an NS3/4A protease inhibitor (boceprevir or telaprevir [36, 48]) in combination with pegylated alpha interferon and ribavirin (PegIFN/RBV). This new standard of care still has limited efficacy, particularly among treatment-experienced patients who previously failed to respond to PegIFN/RBV therapy, and is associated with several adverse reactions. Research into more effective antiviral therapies has, in part, focused on host targets that may lead to broadly active drugs with pangenotype activity. These may also provide greater barriers to drug resistance. The availability of multiple new therapeutic options could lead to regimens that are free of PegIFN and/or RBV.

Several groups have performed screens to identify cellular cofactors involved in HCV replication and infection. A common target identified in the various screens is phosphatidylinositol-4-kinase IIIα (PI4KIIIα) (10, 15, 43, 50, 59, 63, 64). PI4KIIIα is one of four mammalian phosphatidylinositol 4-kinases that catalyze the first step in phosphoinositide synthesis (5). PI4KIIIα is a 230-kDa protein (58) that is primarily localized in the endoplasmic reticulum (67) and apparently contributes to the formation of endoplasmic reticulum exit sites (14, 24) as well as the maintenance of plasma membrane phosphoinositide pools (6).

PI4KIIIα associates with NS5A in infected cells (11, 44, 50, 61). By use of a yeast two-hybrid approach, PI4KIIIα was found to interact with NS5A in a proteome-wide mapping of interactions between HCV and human proteins (20). In another yeast two-hybrid study, using a portion of the HCV NS5A protein as a bait, the region of amino acids (aa) 1799 to 1916 of PI4KIIIα was proposed to interact with domains II and III of NS5A (aa 300 to 447 [1]), while coimmunoprecipitation experiments demonstrated that a reduction in the interaction between NS5A and PI4KIIIα was observed only by deleting domain I and not by deletions of domain II or III (50). Deletion mutants of PI4KIIIα and NS5A map the interaction domain of PI4KIIIα to amino acids 401 to 600 and domain I of NS5A (44).

Genetic (11, 50, 61) and pharmacological (12) approaches have also been used to demonstrate that the enzymatic activity is essential and PI4KIIIα is required for the integrity of the membranous web and PI4-phosphate (PI4P) levels are enriched on these membranes. Additionally, NS5A stimulates the enzymatic activity of PI4KIIIα (11, 50). PI4KIIIα may therefore be recruited by NS5A to sites where it is needed for formation of the membranous web replication complex. Targeted inhibition of this host function may offer the opportunity for more broadly effective anti-HCV therapies.

In this study, we constructed a modified derivative of PI4KA that encoded an N-terminally truncated 130-kDa form of the enzyme, expressed and purified the product, and reconstituted an in vitro biochemical lipid kinase activity that was optimized for the screening of a large compound library to identify inhibitors of PI4KIIIα. To further validate the role of the kinase activity in HCV replication, several of the identified inhibitors that represent different chemotypes were used in subsequent cell culture studies. Two potent compounds from one of the chemotypes were used for HCV replicon resistance studies to identify regions of the HCV nonstructural proteins that may be linked to PI4P metabolism. Furthermore, extensive mouse genetic studies were performed to determine the likely effect of efficient PI4KIIIα inhibition in vivo and to assess the consequence of targeting PI4KIIIα for pharmacologic inhibition. We generated tamoxifen-inducible mouse transgenic mice in which PI4KIIIα can be conditionally knocked out (KO) through a deletion or knocked in (KI) with an amino acid-substituted derivative that codes for a kinase-defective PI4KIIIα. Induction studies were performed, and phenotypes were analyzed in detail.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals and reagents.

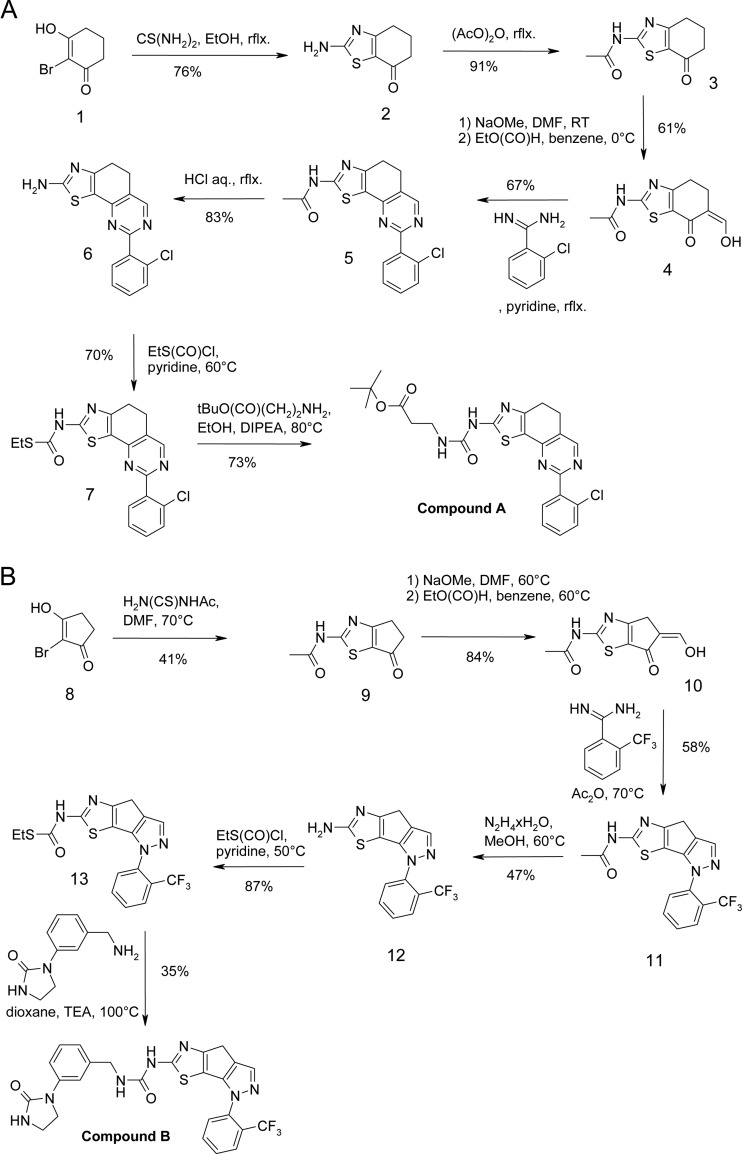

Phosphatidylinositol (sodium salt) was purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids. PtdIns-(1,2-dioctanoyl) sodium salt (PI-diC8) was purchased from the Cayman Chemical Company. GloPIP Bodipy TMR phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate (PI4P-Bodipy-TMR) was purchased from Echelon Biosciences Inc. Triton X-100 (10.8% solution) was from Calbiochem. ATP (100 mM solution, pH 7.5) was purchased from GE Healthcare. The Kinase-Glo Luminescent Kinase assay kit was purchased from Promega. Compounds A and B were synthesized as previously described (16, 17) (Fig. 1). All other chemicals were of analytical grade.

Fig 1.

Schemes for the synthesis of compound A and compound B as described in U.S. patent 2007/0238746 A1 (16) and U.S. patent 2007/0238730 A1 (17).

Expression, production, and purification of PI4KIIIα, PI4KIIIβ, and SidC proteins.

The PI4KA and PI4KB genes with codons optimized for expression in Sf21 insect cells were ordered from DNA 2.0 (Menlo Park, CA). The PI4KA gene portion encoding the N-terminally truncated 130-kDa PI4KIIIα protein (aa 875 to 2044) and the full-length PI4KB gene were subcloned and expressed using pFastBac1 in which glutathione S transferase (GST) had been cloned to express N-terminally tagged GST proteins. Each protein was produced by infecting exponentially growing Sf21 cells diluted to 1 × 106 cells/ml in SF-900II SFM medium (Invitrogen) at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 1 and incubating for 66 h at 27°C. The infected cell pellet was obtained by spinning at 500 × g for 5 min and then frozen at −80°C prior to purification. The GST-130-kDa PI4KIIIα and PI4KIIIβ proteins were purified according to the following procedure: 1 liter of insect cell culture was resuspended in 25 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing one-half of a cOmplete, EDTA-free Protease Inhibitor Cocktail tablet (Roche), 1 mM Pefabloc, and 2 mM EDTA. The resuspended cells were processed in a Dounce homogenizer for 50 strokes and then diluted with 25 ml of PBS. Nuclei were removed by centrifugation, and the cytosolic fraction (33 to 37 ml) was incubated on ice for 1 h with glutathione (GSH)-Sepharose 4B resin (GE Healthcare). The resin was pelleted at 500 × g for 5 min and then washed with 40 ml of PBS. This cycle was repeated 4 times. The protein was eluted by incubating the washed resin with 4.0 ml of elution buffer (50 mM Tris [pH 8.0], 20 mM reduced glutathione) for 20 min prior to centrifugation. The elution step was repeated twice, and eluates were pooled and spun at 800 × g for 5 min to remove residual resin. The eluate was concentrated in Amicon-Ultra 15 with a 30-kDa cutoff membrane. Glycerol (10%) was added, and aliquots were frozen and stored at −80°C.

Two major contaminants that copurified were identified by mass spectrometry as the baculovirus envelope protein VP25 and the heat shock protein Hsp70, both of which are commonly copurified with GSH-Sepharose resins. The total protein concentration of the pooled GSH eluate was 0.5 to 0.7 mg/ml with ∼20% GST-PI4KIIIα or GST-PI4KIIIβ, ∼50% VP25, and ∼30% Hsp70. VP25 and Hsp70 could be removed with additional purification steps, but screening was performed using the GST-Sepharose-purified material. The specificity of the enzymatic activity and lack of interference by VP25 and Hsp70 were demonstrated by the lack of activity for variants in which an active-site residue was changed (see Results). In all cases, similar PI4KIIIα yields were obtained. In addition, the same two proteins were also bystanders in the counterscreen because they were also copurified in the PI4KIIIβ preparation.

The SidC protein, which binds to PI4P (66), was produced to develop the assay that detects the PI4P lipid product. A codon-optimized gene encoding an N-terminally truncated 39-kDa SidC protein (aa 582 to 917) was obtained from DNA2.0, subcloned, and expressed in Escherichia coli BL21 as an N-terminally GST-tagged 67-kDa protein using pGEX4T1. The GST-SidC protein was produced by transforming E. coli BL21 with the pGEX4T1-SidC plasmid. Two-liter cultures were inoculated with 20 ml of an overnight culture grown at 37°C. The cultures were incubated for 9 h at 25°C (optical density at 600 nm [OD600], ∼0.5 to 0.7) and then cooled to 15°C for 1 h before the addition of 0.5 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside. The cultures were incubated for another 16 to 17 h and then harvested. The cells were resuspended in PBS and disrupted by two successive passages through a French press operated at 12,500 lb/in2 and 4°C. The cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 27,000 × g for 30 min. The supernatant was carefully isolated, and the subsequent steps of the purification were performed using the GSH-Sepharose 4B resin (GE Healthcare) as described for PI4KIIIα and PI4KIIIβ.

PI4KIIIα and PI4KIIIβ assays for the detection of PI4P formation and ATP consumption.

A fluorescence polarization (FP) assay that monitored the formation of PI4P was developed for high-throughput screening (HTS) using the soluble lipid PI-diC8 as a substrate. This assay was based on a previously reported format (22) with adjustments to the specific assay components. A basal FP signal was obtained with the high-affinity binding of PI4P-Bodipy-TMR probe to SidC, which is subject to PI4P competitive displacement produced by PI4KIIIα or PI4KIIIβ (counterscreen). Two microliters of compound dissolved in 1× assay buffer (20 mM HEPES [pH 7.5], 10 mM MgCl2, 0.075% Triton X-100) containing 3% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was first added to a black Corning 384 Well Low Volume Polystyrene NBS Microplate 3676. Two microliters of the enzyme (1/32 dilution of stock for PI4KIIIα and 1/80 dilution of stock for PI4KIIIβ) premixed with 300 μM PI-diC8 in 1× assay buffer was then added using a MultiDrop Combi (Thermo Fisher). The positive-control wells did not contain inhibitors, and the negative-control wells did not contain enzyme. The plates were incubated without mixing at room temperature for 5 min prior to the addition of 2 μl of 15 μM ATP in 1× assay buffer using a MultiDrop Combi. The plates were then incubated at room temperature for 1 h. Six microliters of 100 mM EDTA, 30 nM PI4P-Bodipy-TMR, 300 nM SidC protein, 10% glycerol in 1× assay buffer was then added to quench the reaction and detect the amount of PI4P produced. The plates were then incubated at room temperature for 1.5 h and processed on an Envision reader (Perkin-Elmer) with an excitation wavelength of 531 nm and emission wavelength of 595 nm. This assay format provided an assay window of ∼100 millipolarization units (mP) with <1.5% coefficient of variation (CV) and robust assay statistics (Z′ > 0.7).

A Kinase-Glo assay format (Promega) was developed for the routine testing of inhibitors. In this format, consumption of the ATP substrate was monitored, and a PI substrate extracted from natural sources was used (Avanti Polar Lipids). A PI-enzyme solution was prepared by first dissolving the PI in chloroform. The appropriate quantity was then transferred using a Gastight syringe (Hamilton Company) followed by evaporation of the chloroform under a flow of nitrogen. The PI was then dissolved to homogeneity in 2× assay buffer (40 mM HEPES [pH 7.5], 20 mM MgCl2, 0.15% Triton X-100), the diluted enzyme (1/30 dilution of stock for PI4KIIIα and 1/75 dilution of stock for PI4KIIIβ) was added, and the solution was diluted to 1× assay buffer (20 mM HEPES [pH 7.5], 10 mM MgCl2, 0.075% Triton X-100) with water to obtain a concentration of 600 μM PI and the diluted enzyme. Three microliters of test compound dissolved in assay buffer containing 6% DMSO (final concentration) was first added to a white OptiPlate-384 (Perkin-Elmer), and then 3 μl of the PI/enzyme stock solution was added. The positive-control wells did not contain inhibitors, and the negative-control wells did not contain enzyme. The plates were then incubated for 30 min at room temperature followed by the addition of 3 μl of 3 μM ATP to start the reaction in a total volume of 9 μl. The plates were incubated for 1 h at room temperature, followed by the addition of 9 μl of Kinase-Glo. After a 30-min incubation, the plates were read using a TopCount or Envision reader (Perkin Elmer). The Kinase-Glo format also provided for a consistent assay signal, minimal well-to-well variability (CV < 12%), and robust assay statistics with Z′ values of >0.7.

The formation of PI4P could also be monitored using a low-throughput but highly sensitive radioactive-assay format. The same assay conditions as those of the Kinase-Glo format were used, except that the reaction was supplemented with [γ-33P]ATP (maintaining the same final ATP concentration). PI4P extraction was performed as previously described (47) and followed by liquid scintillation counting.

Cultures, cell lines, and viral replication assays.

Cultures and assays with the viral subgenomic replicons were performed as previously described (64). Transient-transfection assays and stable PI4KA knockdown HuH-7 and HuH-7.5 clones have been previously described (64).

Selection of HCV subgenomic replicons resistant to PI4KIIIα inhibition by compounds A and B.

The S22.3 cell line derived from the Con-1 sequence was used to select resistant clones (3). Cells were trypsinized and resuspended in fresh medium (Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium [DMEM], 10% fetal calf serum) containing 1 mg/ml G418 (Invitrogen). Approximately 150,000 cells were plated into 1 well of a 6-well plate. The following day (day 0), fresh medium containing compound A at 1.6 μM or compound B at 0.16 μM and 1 mg/ml G418 was added to the well. On day 3, cells were trypsinized and transferred to a 10-cm plate. Medium (containing fresh inhibitor and 1 mg/ml G418) was changed on day 6. At day 10, the medium was changed, with fresh medium harboring the same concentration of inhibitors and only 0.5 mg/ml G418. Fresh medium with inhibitor and 0.5 mg/ml G418 was replaced every 3 to 4 days. Only a few colonies were visible after a minimum of 30 days of selection. The colonies were isolated and expanded into cell lines for further analysis.

The total cellular RNA, containing the HCV subgenomic replicon RNA, was isolated from resistant clones using the Qiagen RNeasy protocol. HuH-7.5 cells (13) were electroporated with 10 μg of total RNA and seeded into two 10-cm dishes with fresh medium; 72 h later, the medium was supplemented with G418 (0.5 mg/ml) and compound A or B at the same concentrations as described above. Colonies that were visible after 4 weeks were isolated. Long-term resistant replicon selection was maintained for cell expansion, and the total cellular RNA, containing the HCV subgenomic replicon RNA, was isolated as described above. HCV sequences were amplified by reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR), and the DNA product was sequenced with HCV-specific primers. Quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) of the HCV replicon and PI4KA were performed as described previously (64).

Genetic mapping and HCV RNA replication rescue in a PI4KIIIα knockdown cell line.

DNA products from a reverse transcriptase PCR obtained from HCV replicon RNA isolated from cell lines resistant to compound A were digested with restriction enzymes. Specifically, FseI and PacI digestion generated an NS4B-NS5A fragment that was transferred to an R3-derived luciferase reporter HCV subgenomic replicon. An SrfI-MluI subfragment encoding the last 67 amino acids from NS4B and the first 91 amino acids from NS5A was also subcloned in the same replicon. The NS4B S258P and NS5A R70S point mutations were introduced using the QuikChange Lightning site-directed mutagenesis kit from Stratagene.

Vector construction for the generation of Pi4ka conditional KO mice.

The targeting vector was based on a 10.2-kb genomic fragment from the Pi4ka gene encompassing exons 44 to 55 and surrounding sequences. This fragment, obtained from the C57BL/6J RP23 BAC library, was modified by inserting a loxP site and an FLP recognition target (FRT)-flanked neomycin resistance (NeoR) gene in intron 45 and a loxP site in intron 52 as well as a ZsGreen cassette at its 3′ end.

ES cell culture for the generation of Pi4ka conditional KO mice.

The quality-tested C57BL/6NTac embryonic stem (ES) cell line was grown on a mitotically inactivated feeder layer comprised of mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEF) in high-glucose DMEM containing 20% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (PAN Biotech GmbH) and 1,200 U/ml leukemia inhibitory factor (ESG 1107; Millipore). Cells (1 × 107) and 30 μg of linearized DNA-targeting vector were electroporated (Gene Pulser; Bio-Rad) at 240 V and 500 μF. Positive selection with G418 (200 μg/ml) started on day 2 after electroporation. Nonfluorescent resistant ES cell colonies with a distinct morphology were isolated on day 8 after transfection and expanded in 96-well plates. Correctly recombined ES cell clones were identified by Southern blot analysis using several restrictions and external and internal probes and were frozen in liquid nitrogen. The probe A was amplified by PCR using the primers CCAAACCAAACTAAAACCTTCC and AGCAGAGGAGGCTATGGTGG.

Generation of Pi4ka conditional KO mice.

The animal study protocol was approved by the local authority according to the German Animal Welfare Act (TierSchG, article 8, section 1). Mice were kept in the animal facility at TaconicArtemis GmbH in microisolator cages (Tecniplast Sealsave). Feed and water were available ad libitum. Light cycles were on a 12:12-h light/dark cycle with the light phasing starting at 0600 h. Temperature and relative humidity were maintained between 21 and 23°C and 45 and 65%.

After administration of hormones, superovulated BALB/c females were mated with BALB/c males. Blastocysts were isolated from the uterus at 3.5 days postcoitum (dpc). For microinjection, blastocysts were placed in a drop of DMEM with 15% fetal calf serum (FCS) under mineral oil. A flat-tip, piezo-actuated-microinjection pipette with an internal diameter of 12 to 15 μm was used to inject 10 to 15 targeted C57BL/6NTac ES cells into each blastocyst. After recovery, 8 injected blastocysts were transferred to each uterine horn of 2.5-dpc, pseudopregnant NMRI females. Chimerism was measured in chimeras (G0) by coat color contribution of ES cells to the BALB/c host (black/white). Highly chimeric mice were bred to C57BL/6-Tg(CAG-Flpe)2Arte females with mutations of the presence of the Flp recombinase gene. This allowed detection of germ line transmission by the presence of black, strain C57BL/6, offspring (G1) and creation of selection marker-deleted conditional mice by Flp-mediated removal, in one breeding step.

Genotyping of Pi4ka conditional KO mice by PCR.

Genomic DNA was extracted from 1- to 2-mm-long tail tips using the NucleoSpin Tissue kit (Macherey-Nagel). Genomic DNA (2 μl) was analyzed by PCR in a final volume of 50 μl in the presence of 2.0 mM MgCl2, 200 μM dinucleoside triphosphates (dNTPs), 100 nM each primer, and 2 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Invitrogen) with primers 1264_27, CTCCACAGAGAGGCACTAACC, and 1264_28, GGAGTGCTTGCCCTCGCTTGC, detecting the presence of the wild-type allele (191 bp) and the conditional allele (305 bp). Following a denaturing step at 95°C for 5 min, 35 cycles of PCR were performed, each consisting of a denaturing step at 95°C for 30 s, followed by an annealing phase at 60°C for 30 s and an elongation step at 72°C for 1 min. PCR was finished by a 10-min extension step at 72°C. Amplified products were analyzed using 2% standard Tris-acetate-EDTA (TAE) agarose gels.

Selection of amino acid substitution for the generation of Pi4ka conditional KI mice.

Several catalytic site variants were generated, purified, and tested in the biochemical assays. The S1884A, D1899A, R1900A, R1900K, and N1904N variants were generated and tested in the radioactive-assay format. All variants were inactive (<0.06% of wild-type [WT] activity) except the S1884A variant, which demonstrated 25% of the WT activity. Given its level of conservation and location in the mouse genome, the R1900K substitution was the best candidate for the generation of a conditional KI mouse.

Vector construction for the generation of Pi4ka conditional KI mice.

The first targeting vector was based on a 13.6-kb genomic fragment from the Pi4ka gene encompassing exons 44 to 55 and surrounding sequences. This fragment, obtained from the C57BL/6J RP23 BAC library, was modified by inserting a loxP site in intron 47, a human growth hormone polyadenylation signal (hGHpA), a loxP site, and an FRT/F3-flanked cassette expressing the thymidine kinase (TK) and NeoR genes downstream of exon 55. hGHpA was inserted to prevent transcriptional read-through into the duplicated region of Pi4ka and thus precluded the expression of the mutated protein in the absence of Cre activity.

The second targeting vector was based on a 3.5-kb genomic fragment from the Pi4ka gene encompassing exons 48 to 55 and surrounding sequences. This fragment, obtained from the C57BL/6J RP23 BAC library, was modified by inserting an FRT site and an attB/attP-flanked puromycin resistance (PuroR) gene in intron 48 and an F3 site downstream of exon 55. It also carries the point mutation (PM) R1900K in exon 51.

ES cell culture for the generation of Pi4ka conditional KI mice.

The quality-tested C57BL/6NTac ES cell line was grown on a mitotically inactivated feeder layer comprised of MEF in high-glucose DMEM containing 20% FBS (PAN Biotech GmbH) and 1,200 U/ml leukemia inhibitory factor (ESG 1107; Millipore). Cells (1 × 107) and 30 μg of linearized DNA from the first targeting vector were electroporated (Gene Pulser; Bio-Rad) at 240 V and 500 μF. Positive selection with G418 (200 μg/ml) started on day 2 after electroporation. Resistant ES cell colonies with a distinct morphology were isolated on day 8 after transfection and expanded in 96-well plates. Correctly recombined ES cell clones were identified by Southern blot analysis using several restrictions and external and internal probes and were frozen in liquid nitrogen. Two of these clones were selected and cotransfected with the second targeting vector and a plasmid expressing the Flpe recombinase. The transfection was performed via lipofection with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Puromycin selection (1 μg/ml) started on day 2 after electroporation. Counterselection with ganciclovir (2 μM) started on day 5 after electroporation. Resistant ES cell colonies with a distinct morphology were isolated on day 7 after transfection. Correctly recombined ES cell clones were identified by Southern blot analysis using several restrictions and external and internal probes and were frozen in liquid nitrogen. The probe B was amplified by PCR using the primers AAGTACCTGCAGCGCCACAAGCTG and TAGACAGCCTGGACCCTGTTCGC.

Generation of Pi4ka conditional KI mice.

The animal study protocol was approved according to the German Animal Welfare Act, as noted above, by the local authority. Mice were kept in the animal facility as described above in “Generation of Pi4ka conditional KO mice.”

After administration of hormones, superovulated BALB/c females were mated with BALB/c males. Blastocysts were isolated from the uterus at dpc 3.5. For microinjection, blastocysts were placed in a drop of DMEM with 15% FCS under mineral oil. A flat tip, piezo-actuated-microinjection pipette with an internal diameter of 12 to 15 μm was used to inject 10 to 15 targeted C57BL/6NTac ES cells into each blastocyst. After recovery, 8 injected blastocysts were transferred to each uterine horn of 2.5-dpc, pseudopregnant NMRI females. Chimerism was measured in chimeras (G0) by coat color contribution of ES cells to the BALB/c host (black/white). Highly chimeric mice were bred to C57BL/6-Rosa26(C31)Arte females with mutation of the presence of the phiC31 recombinase gene. This allowed detection of germ line transmission by the presence of black, strain C57BL/6 offspring (G1) and creation of selection marker-deleted conditional mice by phiC31-mediated removal, in one breeding step. Chimeric mice and conditional KI mice were bred to Gt(ROSA)26Sortm9(creESR1) mice expressing a tamoxifen-inducible Cre recombinase to obtain experimental animals with the targeted allele 2 (Cre heterozygous [Cre het]) or the conditional KI allele (Cre het) genotypes.

In order to obtain a sufficient number of animals homozygous for the Pi4ka targeted allele 2 (Cre het) genotype, two males of this genotype were used for to perform a rapid expansion by in vitro fertilization (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA). One hundred thirty animals were derived, and one subsequent round of breeding was required to obtain the desired homozygous Pi4ka (Cre het) animals. This model is available at TaconicArtemis (Taconic Emerging Model 11694).

Genotyping of Pi4ka conditional KI mice by PCR.

Genomic DNA was extracted from 1- to 2-mm-long tail tips using the NucleoSpin Tissue kit (Macherey-Nagel). Genomic DNA (2 μl) was analyzed by PCR in a final volume of 50 μl in the presence of 2.0 mM MgCl2, 200 μM dNTPs, 100 nM each primer, and 2 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Invitrogen) with appropriate primers. Following a denaturing step at 95°C for 5 min, 35 cycles of PCR were performed, each consisting of a denaturing step at 95°C for 30 s, followed by an annealing phase at 60°C for 30 s and an elongation step at 72°C for 1 min. PCR was finished by a 10-min extension step at 72°C. Amplified products were analyzed using a Caliper LabChip GX device. The primers 2100_50, GTATGCCAGCACCACCTAGCG, and 2100_48, CTGGGCTACAAGTTTCCCTAGG, detect the presence of the wild-type allele (246 bp), the conditional KI allele, and targeted allele 2 (327 bp), as well as the constitutive KI allele (432 bp). The primers 1242-1, CCATCATCGAAGCTTCACTGAAG, and 1242-2, GGAGTTTCAATACCCGAGATCATGC, detect the presence of the creESR1 transgene (310 bp). The primers 1260_1, GAGACTCTGGCTACTCATCC, and 1260_2, CCTTCAGCAAGAGCTGGGGAC,were used as internal control (585 bp).

Tamoxifen induction studies.

The animal study protocols were approved by the local institutional animal care and use committee (IACUC) and performed according to the Association for Assessment of and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC) guidelines. Tamoxifen was prepared as a 50-mg/ml solution in corn oil and was administered via oral gavage (200 mg/kg of body weight). The formulations were prepared fresh daily for 5 consecutive days. Healthy animals were sent for necropsy after 30 days. Animals in a moribund state were euthanized earlier. Tissues were collected upon euthanasia, half sections were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and the remainder of the tissue was placed in 10% neutral buffered formalin.

For the Pi4ka conditional KO mice model, two tamoxifen induction studies were performed. In total, seven Pi4ka homozygous (Cre het) animals were induced together with nine Pi4ka heterozygous (Cre het) animals. The following control animals were also included in the study and treated with tamoxifen: 4 Pi4ka Ho, Cre WT; 5 Pi4ka WT, Cre Het; and 4 Pi4ka WT, Cre WT. In each group, an extra 1 to 4 animals were included and treated only with vehicle.

For the Pi4ka conditional KI mice, a tamoxifen induction study was performed with four Pi4ka animals homozygous for the targeted allele 2 (Cre het), one Pi4ka animal homozygous for the conditional allele (Cre het), and four Pi4ka heterozygous (Cre het) animals. The following control animals were also included in the study and treated with tamoxifen: 2 Pi4ka WT, Cre Het; and 2 Pi4ka WT, Cre WT. In each group, an extra 1 or 2 animals were included and treated only with vehicle.

Quantification of RNA and protein levels in induced mice.

RNA and proteins were extracted using the Paris kit (Ambion), and the BioMasher device (Nippi Inc.) was used to grind tissue samples, followed by a DNase treatment (DNA-free; Ambion) of the total RNA. The WT, KO, and KI RNAs were analyzed using different PCR protocols. For the conditional KO, RNA was quantified with Ribogreen and analyzed by qRT-PCR using a real-time PCR System model 7500 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and the primers and probe of the TaqMan Gene Expression Assay ID Mm01344904_m1 for the quantification of total Pi4ka RNA (exon boundary 43 to 44) and the TaqMan Gene Expression assay ID Mm01344908_m1 for the quantification of WT Pi4ka RNA levels only (exon boundary 47 to 48, ΔExons 46 to 52 in KO). Relative Pi4ka levels were determined in comparison to NIH 3T3 total RNA. For the conditional KI model, the same extraction protocol was used. The total RNA was used in RT-PCR products that were extracted from agarose gels with the Illustra GFX DNA purification kit (GE Healthcare). Quantification was done using a Nanodrop system, and similar amounts of DNA were analyzed with a Custom TaqMan single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) genotyping assay (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and allelic-discrimination qPCR. The following unlabeled PCR primers and TaqMan MGB probes (6-carboxyfluorescein [FAM] and VIC dye labeled) were used to detect the WT and KI sequences: forward primer, 5′-CCTATAGCCTCCTGCTGTTCCT-3′; reverse primer, 5′-CCTTCTTGTCCAGCATGATGTTG-3′; WT probe, 5′-ATCAAGGACAGGCACAAT-3′ (VIC-labeled); KI probe (FAM-labeled), 5′-ATCAAGGACAAGCACAAT-3′ (underlining indicates the base that differs between the WT and KI sequences); all were directly supplied by the Assay-by-Design service from Applied Biosystems. The levels of WT and KI were verified by sequencing with a forward primer localized in exon 50 and 120 bp from the mutant base pair (G5699A in Mm_NM_001001983) using the ABI PRISM 7900HT Sequence Detection system. Protein concentrations were determined using the Bio-Rad protein assay reagent with bovine serum albumin (BSA) standard and were quantified by Western blotting using a custom rabbit polyclonal antibody (Cambridge Research Biochemicals) generated with a peptide corresponding to the region of amino acids 966 to 983 of human PI4KIIIα that is also conserved in the mouse sequence. The levels of β-actin were also determined as internal controls. SuperSignal West Femto substrate (Promega) or ECL Plus (GE Healthcare) was used for visualization.

Histopathology analyses.

Formalin-preserved tissues were trimmed, processed, embedded in paraffin, sectioned at 5 μm, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). The H&E-stained tissues were examined via light microscopy by one veterinary pathologist, and a peer review was conducted by a second veterinary pathologist.

RESULTS

PI4KIIIα expression, purification, assay development, and screening.

An N-terminally truncated 130-kDa form (aa 875 to 2044) of the PI4KIIIα enzyme known to be highly active (33) was expressed in Sf21 insect cells as a GST-tagged protein and purified on the GST-Sepharose resin. The specificity of the active enzyme preparation was demonstrated by site-directed substitution of two different single-amino-acid active-site residues (D1899A or R1900K), which generated inactive PI4KIIIα variants. The yields of the R1900K and D1899A PI4KIIIα variants were similar to those of the wild type, and the enzymatic activity of both variants was no greater than background activity.

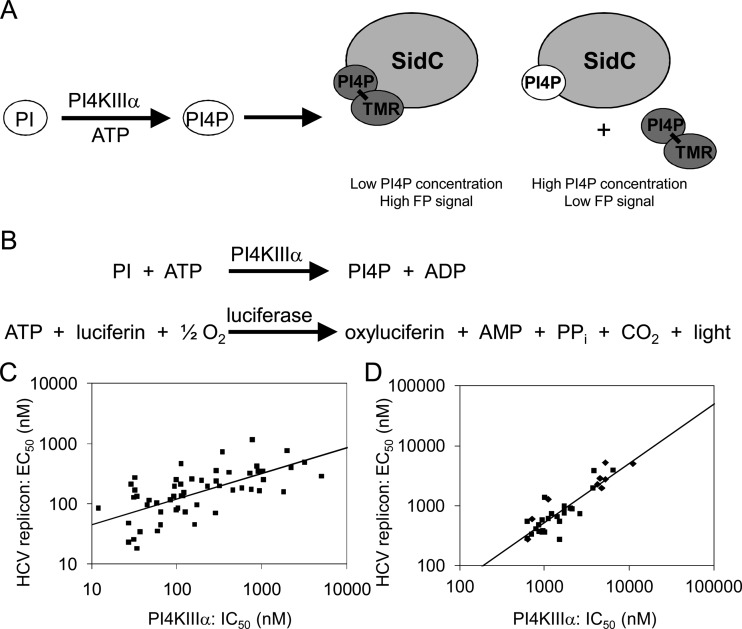

A PI4KIIIα lipid kinase assay was developed using the SidC protein, which specifically binds PI4P. The PI4P lipid product is quantified by a competitive displacement of a fluorescent analog of PI4P using fluorescence polarization (Fig. 2A). An advantage of the FP assay format is that it used a more soluble PI substrate with a shorter lipid chain (PI-diC8), which prevented the formation of suspended insoluble aggregates often observed in the Kinase-Glo assay format (see below), which used longer lipid chains. Consequently, the FP assay was used to perform a high-throughput screen (HTS) with the BI compound library. A hit rate of 0.64% was obtained for >500,000 compounds screened. Individual compounds within the hit list were triaged on the basis of an overall profile that included physicochemical properties, PI4KIIIα potency as determined by concentration-response behavior, counterscreening against PI4KIIIβ, cytotoxicity testing, and cell culture activity in the HCV subgenomic replicon assay (9, 45). The selected compounds that fulfilled the profiling criteria clustered into three separate inhibitor families.

Fig 2.

(A, B) Schematics of activity assays developed to identify inhibitors of PI4KIIIα: fluorescent polarization (FP) assay to detect the formation of PI4P by PI4KIIIα (A) and Kinase-Glo assay to detect the consumption of ATP by PI4KIIIα (B). (C, D) Correlation of PI4KIIIα in vitro potency (IC50) with HCV replication inhibition (replicon EC50) obtained with chemotype 1 (slope of the observed correlation, 0.43; R2 = 0.49; P < 0.05; 57 compounds tested) (C) and with chemotypes 2 (squares) and 3 (diamonds) (slope of the observed correlation, 0.99; R2 = 0.75; P < 0.05; 51 compounds tested) (D).

The Kinase-Glo assay format amenable for multiwell, plate-based screening of inhibitors was used to measure enzymatic activity on a routine basis. In this assay format, PI4KIIIα-catalyzed depletion of ATP is indirectly quantified by the luminescence generated from the ATP-dependent luciferase oxidation of luciferin to oxyluciferin (Fig. 2B). Luminescence is directly proportional to the remaining ATP concentration.

PI4P product is an essential factor for HCV replication.

Results for the three inhibitor families (chemotypes) identified by the HTS provided a remarkably good correlation between inhibition of HCV replication (50% effective concentration [EC50]) and PI4KIIIα activity (50% inhibitory concentration [IC50]) (Fig. 2C and D). Representatives of each chemotype were profiled for off-target activity against other kinases. The three chemotypes demonstrated “off-target” profiles that were clearly distinct. Chemotype 1 potently inhibited type I phosphoinositide 3-kinases. Compound A inhibited phosphoinositide 3-kinase α, β, δ, and γ with IC50 of 1,400 nM, 30 nM, 630 nM, and 1.2 nM, respectively. Compound B inhibited phosphoinositide 3-kinase α, β, δ, and γ with IC50 of 180 nM, 140 nM, 35 nM, and 0.6 nM, respectively. Compounds from chemotypes 2 and 3 inhibited distinct classes of protein kinases without any observed lipid kinase inhibition. Notably, no correlation was observed between inhibition of HCV replication and the activity against any other kinase. This cross-chemotype correlation provides additional support for an important role for local PI4P lipid production in HCV RNA replication.

Isolation and characterization of HCV replicons resistant to PI4KIIIα inhibitors.

Compounds A and B from chemotype 1 (Fig. 1) were used to select for drug-resistant HCV replicon cell lines. Compound A had a PI4KIIIα IC50 of 450 nM and an EC50 of 170 nM in the HCV replicon cell-based assay. Compound B had a PI4KIIIα IC50 of 27 nM and an EC50 of 23 nM in the cellular HCV replicon. Both compounds demonstrated acceptable selectivity indices (>10), with HuH-7 cytotoxicity based on CC50 (concentration of compound that reduced cell viability by 50% compared to the untreated controls) of 10,000 nM and 1,000 nM for compounds A and B, respectively. Moreover, both compounds demonstrated a 15- to 20-fold PI4KIIIα selectivity with corresponding IC50s for PI4KIIIβ of 8,000 nM and 440 nM for compounds A and B, respectively. The selection experiment was performed using the S22.3 cell line, which harbors a replicon based on the Con-1 genotype 1b sequence (3). EC50s of 300 nM and 60 nM were determined for compounds A and B, respectively, in this line (Table 1). In order to minimize cytotoxic effects in this study, the compounds were incubated at a concentration 2.5- to 5-fold above their EC50s and 6- to 9-fold below their corresponding CC50 to provide a sufficient window to select for resistant HCV replicons.

Table 1.

Potency of PI4KIIIα inhibitors of different chemotypes against parental and resistant retransfected repliconsa

| HCV replicon | EC50 (μM) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemotype 1 |

Chemotype 2 |

Chemotype 3 |

NS5B pol inhibitor | ||||

| Cmpd A | Cmpd B | Cmpd C | Cmpd D | Cmpd E | Cmpd F | ||

| Parental S22.3 | 0.30 | 0.060 | 1.9 | 2.2 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 0.012 |

| Cmpd A-resistant clone | 7.4 | >1.1 | >10 | >22 | >11 | >10 | 0.023 |

| Cmpd B-resistant clone | >3.0 | >1.1 | >10 | >22 | 11 | >10 | 0.020 |

Presence of the “ >” sign in front of a value indicates that <50% inhibition was observed at the highest concentration tested. Cmpd, compound; pol, polymerase.

In contrast to standard selection with NS3 or NS5B direct acting antivirals (DAAs) (39, 41), relatively few colonies were selected after a minimum incubation of 30 days with the compounds. Clonal lines obtained by expansion of these colonies were confirmed to be less sensitive to compounds A and B, as well as to compounds from the unrelated chemotypes 2 and 3. The levels of PI4KA mRNA were unchanged in the different clones. Serial passaging of HCV replicon RNA by extraction of total RNA, followed by transfection into naïve HuH-7.5 cells, confirmed that the resistance phenotype was linked to HCV replicon RNA rather than cell adaptation and also conferred broad resistance against the other two chemotypes (Table 1). The phenotype of these serially passaged replicon-resistant clones showed an ∼20-fold shift in sensitivity to PI4KIIIα inhibition but no major shift in sensitivity (<2-fold) to a potent HCV polymerase inhibitor (Table 1) or other classes of DAA that were tested, including the NS5A inhibitor daclatasvir (BMS-790052) (data not shown).

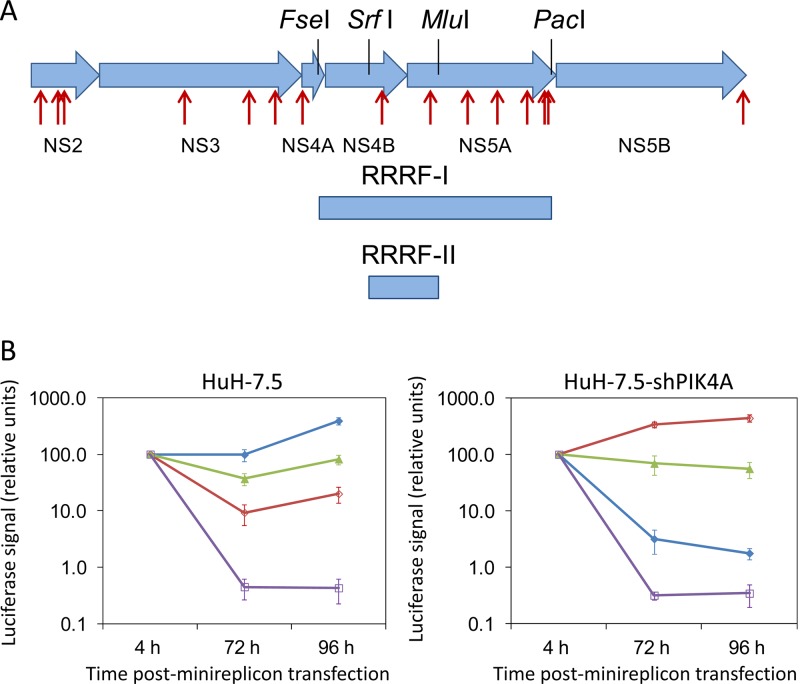

Fifteen amino acid changes were identified in the HCV replicon sequence isolated from the clonal line resistant to compound A. These were distributed throughout the nonstructural region (Fig. 3A). In order to identify which of these changes specifically confer resistance to compound A, we used a luciferase derivative of our Con-1b-adapted clone R3 (40) to construct chimeric subgenomic replicons containing defined fragments from the resistant clone.

Fig 3.

Resistance study using PI4KIIIα inhibitors. (A) Genetic mapping of the region involved in resistance. Fifteen amino acid changes (red arrows) were identified in the HCV replicon sequence isolated from the clonal line resistant to compound A. These were distributed throughout the nonstructural region with 3 changes in NS2 (L33P, I86T, and F103S), 3 in NS3 (G262S, M470I, and N556S), 1 NS4A (T2A), 1 NS4B (S258P), 6 in NS5A (R70S [G70 in Con-1], S107T, G267E, D358N, L419P, and G421R), and 1 in NS5B (I585V). The FseI-PacI replicon-resistant restriction fragment I (RRRF-I) and the SrfI/MluI replicon-resistant restriction fragment II (RRRF-II) were obtained from the RT-PCR DNA product of the clonal line resistant to compound A. (B) Luciferase levels obtained after transient transfection of the chimeric replicon RNA in HuH-7.5 cells (left panel) and in the stable PI4KA knockdown cell line (HuH-7.5-shPIK4A; right panel). Luciferase levels were determined at 4, 72, and 96 h posttransfection. Values are corrected for transfection efficiency by measuring the signal at 4 h and expressing all luciferase levels as a percentage of this value. Luciferase levels of the baseline replicon (R3-derived replicon) with the FseI/PacI region of the S22.3 parent replicon are shown in blue (closed diamonds); with the RRRF-I region of the compound A-resistant clone, in red (open diamonds); and with the RRRF-II region of the Cpd A-resistant clone, in green (closed triangles). As a negative control, a replication-incompetent replicon (NS5A deletion of residues 55 to 60) was used (purple, open squares).

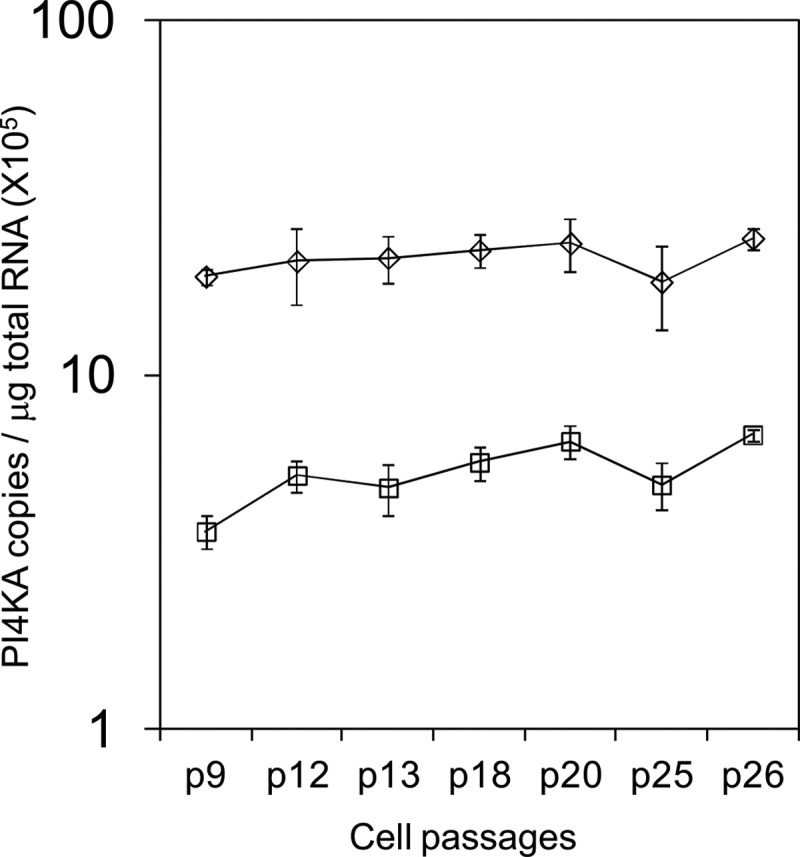

In order to facilitate these genetic mapping experiments, we established HuH-7.5 clones that stably expressed small hairpin RNA (shRNA) targeting PI4KIIIα (Fig. 4). The resulting HuH-7.5-shPIK4A cell line was confirmed to have significantly reduced PI4KIIIα levels and could not support the replication of our Con-1-adapted R3 clone, which replicates with high efficiency in HuH-7.5 cells. Our experimental strategy was to isolate the minimal contiguous replicon-resistant restriction fragment (RRRF) from the compound A-resistant replicon clone, which in an R3 replicon chimera would rescue HCV RNA replication in the HuH-7.5-shPIK4A cell line. The RRRF-I spanning NS4B-NS5A was used to generate a luciferase R3-derived chimeric replicon that rescued replication in HuH-7.5-shPIK4A cells, and for which a 1-log reduction in replication was observed in HuH-7.5 cells (Fig. 3A and B). The RRRF-II region encoding the last 67 amino acids of NS4B and the first 91 amino acids of NS5A was the minimal functional segment able to restore a low level of replication in the HuH-7.5-shPIK4A cells and encoded the NS4B S258P and NS5A R70S substitutions (Fig. 3A and B). Site-directed mutagenesis to generate individual single and double mutants confirmed that both the NS4B S258P and NS5A R70S substitutions were required to rescue a low level of replication in PI4KIIIα-deficient cells.

Fig 4.

Stability of PI4KA RNA transcript suppression observed in a stable HuH-7.5 shRNA PI4KA knockdown clone. The levels of PI4KA in the control HuH-7.5 cell line are represented by open diamonds, and the levels of PI4KA in the HuH-7.5 PI4KA stable knockdown clone that expresses an shRNA targeting the PI4KA gene are represented by open squares.

PI4KIIIα (Pi4ka) conditional KO mice.

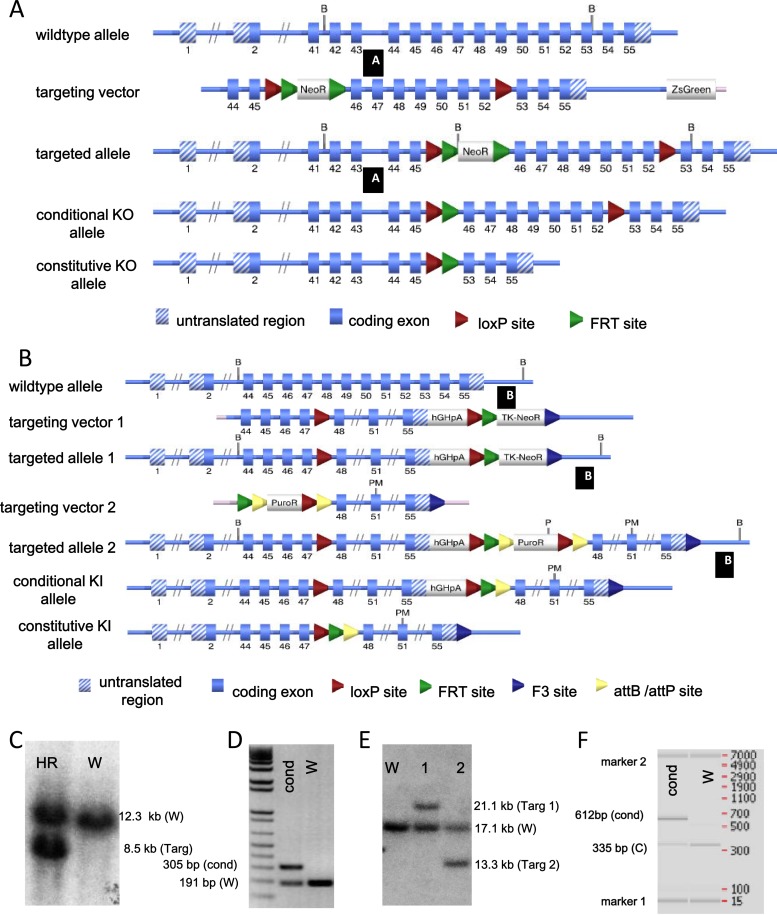

In order to determine the suitability of PI4KIIIα as a target for pharmacologic intervention in vivo, a conditional KO transgenic murine line was generated. A targeting vector was constructed in order to generate a conditional KO mouse line for the Pi4ka gene via homologous recombination in embryonic stem cells. Given the size of the Pi4ka gene, exons 46 to 52 of Pi4ka encoding the kinase domain were flanked by loxP sites. The conditional KO allele was obtained after Flp-mediated removal of the selection marker. The constitutive KO allele was obtained after Cre-mediated recombination. Deletion of exons 46 to 52 removed an essential part of the C-terminal kinase domain of this large gene and generated a frameshift from exon 53 to exon 55, resulting in a loss-of-function Pi4ka truncation (Fig. 5).

Fig 5.

Generation of Pi4ka conditional KO and KI mice. (A, B) Targeting strategies used to generate Pi4ka conditional KO (A) and KI (B) mice. (C) Southern blot analysis of KO homologous recombinant (HR) ES cell clones using a BamHI digest and probe A. W, wild-type signal; Targ, targeted signal. (D) PCR analysis of heterozygous conditional (cond) KO and wild-type (W) mice. (E) Southern blot analysis of KI homologous recombinant ES cell clones using a BsrGI (B) and PvuI (P) digest and probe B. Clone 1 is a homologous recombinant ES cell clone derived from the transfection with the first targeting vector. Clone 2 is derived from clone 1 and has undergone the recombination-mediated cassette exchange with the second targeting vector. W, wild-type signal; Targ 1 and Targ 2, targeted signals. (F) PCR analysis of heterozygous conditional (cond) KI mice. W, wild-type sample; C, internal control.

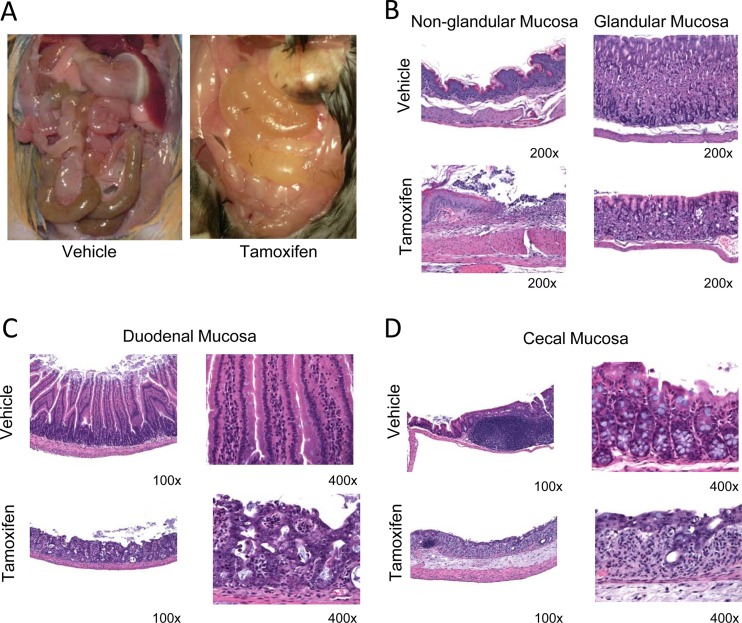

Two tamoxifen induction studies were performed to generate an appropriate number of animals for histopathology analysis. In the first study, three homozygous Pi4ka animals were induced. One died 7 days after the initiation of tamoxifen induction, and the other two were euthanized within 2 days due to their moribund state. In the second study, four homozygous Pi4ka animals were induced, and one animal was found dead 8 days postinduction while the other three were euthanized within 2 days due to their moribund state. Necropsy identified anomalies in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract with distended intestines that were filled with a yellowish clear fluid. The stomach was also distended and filled with food (Fig. 6A). In each study, five heterozygous mice were also induced. All were healthy and did not show any anomalous phenotype. Tissues were collected for RNA and protein level analysis. Histopathology analysis of induced heterozygous mice was not performed. Control animals did not show any anomalous phenotype.

Fig 6.

Gross phenotype and histopathology analysis of induced homozygous conditional Pi4ka KO mice. (A) Distended GI tract gross phenotype observed at necropsy. (B) Histopathology analysis of stomach lesions: ulceration of nonglandular mucosa (left panel) and parietal cell degeneration of glandular mucosa (right panel). (C) Histopathology analysis of small intestine lesions: mucosal epithelial degeneration of duodenal mucosa. (D) Histopathology analysis of large intestine lesions: mucosal epithelial degeneration of cecal mucosa.

H&E-stained sections of liver, heart, kidney, lung, brain, pancreas, and GI tract of the induced Pi4ka homozygous/Cre heterozygous mice were analyzed. The heart, kidney, lung, and brain sections were normal in all animals. The most affected organs were tissues of the GI tract with widespread degeneration and necrosis of mucosal epithelial cells in the mucosae of the stomach and the small and large intestines (Fig. 6B, C, and D).

RNA and proteins were isolated from the liver, stomach, ileum, heart, and brain tissues of induced homozygous animals. Reliable quantification of RNA levels in the stomach and ileum of induced homozygous animals was not possible, likely due to the tissue condition. RNA levels could be obtained only from the brain, liver, and heart of induced homozygous animals. A 20% WT RNA knockdown was observed in the brain, probably due to the low distribution of tamoxifen, and WT RNA knockdown levels of 85% and 60% were observed in the liver and heart, respectively. Similar or slightly greater knockdown levels were also observed in Western blots, and the truncated protein could not be detected in any of these organs despite the presence of mRNA at the expected level. The PI4KIIIα protein could be detected in the tissues of control animals, although protein levels were variable.

PI4KIIIα (Pi4ka) conditional KI mouse.

In order to assess the phenotype caused by specific abrogation of kinase activity without affecting protein levels, an inducible Pi4ka kinase-inactive transgenic mouse was designed to further evaluate the target. The R1900K PI4KIIIα variant with 0.03% of the WT activity was chosen as the basis for this model.

A first targeting vector was constructed in order to flank exons 48 to 55 with loxP sites and introduce docking sites (FRT and F3 recombination sites) into intron 47 and downstream of exon 55 of Pi4ka via homologous recombination in ES cells. The docking sites were then used to duplicate the region of Pi4ka encompassing exons 48 to 55 and insert the point mutation encoding R1900K in exon 51 via recombination-mediated cassette exchange (RMCE) with the second targeting vector. The conditional KI allele was obtained after phiC31-mediated removal of the selection marker and expressed the wild-type Pi4ka gene product (Fig. 5). Both the targeted allele 2 (which still carried the puromycin resistance gene) and the conditional KI allele were used to induce the expression of the site-specifically mutated Pi4ka gene (constitutive KI allele) by Cre-mediated recombination.

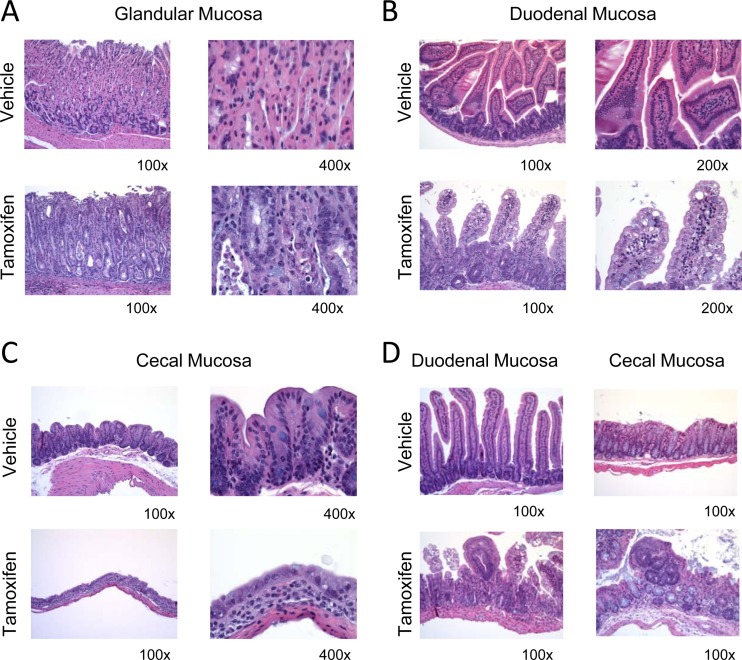

A tamoxifen induction study was performed to assess the effect of the PI4KIIIα R1900K substitution. Four heterozygous and four homozygous adult mice (two males and two females in each case) with the targeted allele 2 were induced. One female mouse homozygous for the conditional allele was also included in the study. Induced homozygous animals were euthanized for tissue collection 10 to 11 days postinduction due to unresolved diarrhea and inactivity to touch. Although the distended intestine phenotype was not observed, intestine contents were loose or discolored in most cases. Animals were also thin and hunched and had a poor coat condition. All induced male heterozygous animals were euthanized 12 days postinduction because they had lost 25 to 30% weight, were becoming inactive and hunched, and had a poor coat condition. Female heterozygotes were healthy, did not show any anomalous phenotype, and were euthanized 30 days postinduction together with the controls. One of the induced heterozygous female had a black focal mild discoloration of the spleen. None of the control animals showed anomalous phenotype.

RNA and proteins were isolated from the liver, stomach, ileum, and brain tissues of induced homozygous animals. Quantification of RNA levels in the unhealthy stomach and ileum was possible in only a few cases, for which a level of ∼75% KI was observed. As expected, background KI levels (5 to 10%) were observed in the brain. Surprisingly, the KI levels were slightly lower than 50% in the liver. The percentages of KI obtained were in good agreement with the relative fluorescence obtained in the electropherograms from sequencing of RNA transcript amplified by qRT-PCR. Western blot analysis revealed normal PI4KIIIα protein levels in the brain. PI4KIIIα could not be detected accurately in the ileum. The PI4KIIIα protein levels in the liver and stomach were variable in both homozygous KI animals and controls.

H&E-stained sections of liver, heart, kidney, pancreas, and GI tract were analyzed. The significant microscopic findings were present only in mice that were sacrificed early because of their moribund condition. All tissues from the other animals in the histopathology analysis, including the induced Pi4ka heterozygous females, were essentially normal. Similar to what was seen in the conditional Pi4ka KO mice, tissues of the GI tract were the most affected organs in the KI Pi4ka homozygous animals that were induced (Fig. 7). Again, there was fairly widespread mucosal epithelial degeneration, especially in the small and large intestines, but less in the stomach. In the small intestines the villous epithelial cells were swollen from excessive vacuoles, and in the large intestines the surface epithelial cells were also swollen and basophilic. In some areas of the large intestines, there was loss of mucosal crypts. Focal atypical hyperplasia of mucosal crypts was occasionally seen in the small intestines. Focal atypical hyperplasia was characterized by the presence of small clusters of enlarged atypical crypts that were lined by tall dysplastic basophilic epithelial cells. Overall, similar observations were found in the induced Pi4ka heterozygous males, but with a lower severity.

Fig 7.

Histopathology analysis of induced homozygous conditional Pi4ka KI mice: stomach lesions showing degeneration of glandular mucosa (A), small intestine lesions showing mucosal epithelial degeneration of duodenal mucosa (B), large intestine lesions showing mucosal epithelial degeneration of cecal mucosa (C), and small and large intestine lesions showing focal atypical hyperplasia of crypt (D).

DISCUSSION

Recent advances in somatic cell genetics have facilitated the identification of host cell genes required to support virus replication. The gene encoding PI4KIIIα was one of the first such genes to be identified. As a kinase, PI4KIIIα represented a potential target for drug development, though it posed substantial technical challenges, particularly in obtaining sufficient active enzyme for large-scale screening. We initiated a PI4KIIIα drug discovery project by cloning and expressing a highly active 130-kDa N-terminally truncated form (33). Shorter truncations of 97 kDa or less are known to be inactive (33, 58). Two different assay formats were developed to monitor the enzymatic activity of PI4KIIIα. Both of these formats were very sensitive, and robust assay performance was obtained with very low ATP concentrations (5 μM for the SidC assay and 1 μM for the Kinase-Glo assay). These ATP concentrations were well below the apparent Km for ATP of 200 to 300 μM (29, 60), and consequently, the assays were very sensitive to ATP-competitive inhibitors. In addition, the availability of two different assay formats monitoring two different components of the kinase reaction (ATP substrate and PI4P product) of PI4KIIIα and PI4KIIIβ allowed the unequivocal identification of PI4KIIIα inhibitors.

The identification of compounds from three distinct chemotypes that inhibited both PI4KIIIα catalysis and replicon activity confirms an essential role for the enzymatic activity in HCV RNA replication. Similar findings from studies using the unrelated 4-anilino quinazoline chemotype have recently been reported (12). Our findings are also in agreement with genetic studies in which HCV replication in HuH-7.5-based cell lines with a knockdown of PI4KIIIα could be rescued only by expression of shRNA-resistant wild-type PI4KIIIα and not the catalytically inactive K1792L or D1899A or D1957A variants (11, 50, 61).

The inhibitor resistance studies provided additional insight into the potential role of PI4KIIIα and its product in the HCV life cycle. In contrast to standard replicon resistance studies with DAAs that rapidly select for mutants, the selection experiments with the PI4KIIIα inhibitors required considerable time and resulted in a few viable colonies. A similar observation was made in a resistance study with inhibitors of cyclophilins, another class of host targets (21, 49).

Resistance to PI4KIIIα inhibitors was mapped in part to the replicon RNA, and amino acid residues in both the C terminus of NS4B and the N terminus of NS5A are genetically linked to a lower HCV dependence on functional PI4KIIIα, as they rescued replication in a PI4KIIIα knockdown cell line. The R70S NS5A mutant is specifically notable as we have previously characterized G70R as an adaptive mutant in Con-1b wild type that enhances replication in HuH-7 cells (3). HuH-7 cells may limit the metabolism of a number of key components that are required for HCV replication, and in retrospect it may not be surprising that we have found distinct changes in adapted Con-1 replicons that are associated with overcoming a PI4KIIIα deficiency and conversely may alter replication fitness in other HuH-7 backgrounds. Our genetic mapping strategy that screened for functional rescue in a PI4KIIIα knockdown cell line was necessitated by the inability to rescue the replication of mutants in wild-type HuH-7 cells. Consequently, a detailed assessment of the isolated NS4B and NS5A amino acid substitutions and resistance to compounds in wild-type Huh-7 cells was not possible. NS4B induces alterations to produce membranous webs (23, 30) that provide distinct vesicles (26, 50), and others have suggested that NS5A has an essential role in membranous web integrity by activating PI4KIIIα, leading to an accumulation of PI4P at sites of HCV replication (11, 50). Alteration of the subcellular distribution of NS5A was demonstrated by the inhibition of PI4KIIIα with the 4-anilino quinazoline chemotype (12). The association of genetic alterations in both NS4B and NS5A that in part compensate for PI4KIIIα deficiency supports this model.

In order to assess the broader physiologic effect of inhibiting PI4KIIIα, a tamoxifen-inducible mouse conditional KO and conditional KI were generated. Upon induction, a lethal effect on the GI tract was observed. This essential host physiologic role raises doubt on the pursuit of PI4KIIIα inhibitors for HCV therapy, especially because of the rapid onset as well as the conditional nature of both of these models, whereby residual levels of WT protein are still detectable in tissues and therefore represent a good model for pharmacologic inhibition. This GI tract phenotype is significantly different from the phenotype observed in the only other reported phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase mouse transgenic model (PI4KIIα encoded by Pi4k2a), in which the kinase catalytic domain was KO by gene trapping (57). In that case, no significant development abnormalities or GI effects were observed; a late onset of degeneration of spinal cord axons leading to a progressive neurological disease and reduced life span of the animals was observed, with an earliest onset of 4 months. These very different results are consistent with the very different cellular functions of the four respective phosphatidylinositol 4-kinases, which are likely not redundant.

The GI tract defects we observed suggest that PI4KIIIα may play an essential role in intestinal tissue renewal and potentially cell division, since intestinal cells are renewed every 3 to 5 days in the mouse (18). Two pools of multipotent intestinal stem cells give rise to hundreds of millions of cells each day. Fast-cycling Lgr5-positive stem cells are present mostly at the crypt base, and the slower-cycling Bmi1-positive stem cells reside mostly above the crypt base (7, 8, 53). PI4KIIIα is likely not functioning only on the Lgr5-positive stem cells because their loss is known not to result in a profound outcome, given that the Bmi-positive stem cells may compensate for the loss and give rise to Lgr5-expressing stem cells (62). PI4KIIIα may therefore play a role directly on the overall pool of stem cells and in the generation of the daughter cells or subsequent differentiation and division. In good agreement with this hypothesis, the downregulation of Pi4ka using morpholino oligonucleotide-based gene silencing in the zebrafish demonstrated that a reduction of Pi4ka levels during zebrafish development leads to an imbalance between proliferation and apoptosis. A major developmental defect marked by a decreased proliferation was observed in the pectoral fin (46). In a Drosophila genetic screen aiming to identify genes required for oocyte polarization, mutations that lead to premature stop codons in CG10260 (which encodes PI4KIIIα) led to the identification of oocyte polarization defects similar to mutations in the Hippo pathway. In addition, mutations in CG10260 were also shown to lead to a Notch signaling defect and failure of oocyte repolarization (68). Notably, Notch is well known to play a key role in intestinal homeostasis and to be active in intestinal stem cells (27, 28, 65).

In addition to HCV, which requires PI4KIIIα (see above) and PI4KIIIβ (15, 19, 35, 63, 70), several other viruses are also known to require lipid kinase activity and phosphoinositides. For example, enteroviruses that are members of the Picornaviridae family appear to recruit PI4KIIIβ to the RNA replication site to yield PI4P-enriched organelles (4, 35), whereas the Aichi virus, a Kobuvirus that is also part of the picornavirus family, appears to use an analogous but slightly different mechanism also requiring PI4KIIIβ for genome RNA replication (31, 55). PI4KIIIβ also appears to play a role in the entry of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (69). The matrix domain of the HIV and the equine infectious anemia virus Gag proteins have been shown to interact with PI4,5P2 (25, 52), whereas the NS1 protein of influenzavirus was demonstrated to directly interact with the p85 protein of a phosphoinositide 3-kinase (32). Interestingly, several human-pathogenic Gram-negative bacteria are also known to subvert host phosphoinositides or lipid kinases to their own advantage. For example, Francisella tularensis, a highly infectious facultative intracellular Gram-negative bacterium, requires PI4KA for proliferation within the cytosol (2). Legionella pneumophila, enteropathogenic Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Yersinia pseudotuberculosis all use distinct phosphoinositide-related mechanisms during infections (34, 37, 54, 56, 66). The type III secretion system of Shigella flexneri encodes a phosphoinositide 4-phosphatase to manipulate host metabolism (38), and a parasitic protist encoding its own essential PI4KIIIβ enzyme is also known (51).

These findings suggest that lipid kinase inhibitors could be useful for treatment of many infectious diseases, in cases for which the enzyme required by the infectious agent is not required by the host. Unfortunately, PI4KIIIα has an essential host physiologic role, raising doubt on the pursuit of PI4KIIIα inhibitors for treatment of chronic HCV infection.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Nathalie Uyttersprot is an employee of TaconicArtemis, and all other authors are employees of Boehringer Ingelheim. This work was supported by Boehringer Ingelheim.

Dee Lawrenia and Susana Gameiro (Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc.) are acknowledged for their histology and photography support, respectively. The High-Throughput Biology group of Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals is acknowledged for performing the HTS. Charles River Laboratories are thanked for breeding and assistance during the performance of the conditional knock-in tamoxifen induction study.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 15 August 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Ahn J, et al. 2004. Systematic identification of hepatocellular proteins interacting with NS5A of the hepatitis C virus. J. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 37:741–748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Akimana C, Al-Khodor S, Abu Kwaik Y. 2010. Host factors required for modulation of phagosome biogenesis and proliferation of Francisella tularensis within the cytosol. PLoS One 5:e11025 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0011025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ali S, Pellerin C, Lamarre D, Kukolj G. 2004. Hepatitis C virus subgenomic replicons in the human embryonic kidney 293 cell line. J. Virol. 78:491–501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Arita M, et al. 2011. Phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase III beta is a target of enviroxime-like compounds for antipoliovirus activity. J. Virol. 85:2364–2372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Balla A, Balla T. 2006. Phosphatidylinositol 4-kinases: old enzymes with emerging functions. Trends Cell Biol. 16:351–361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Balla A, et al. 2008. Maintenance of hormone-sensitive phosphoinositide pools in the plasma membrane requires phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase IIIalpha. Mol. Biol. Cell 19:711–721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Barker N, et al. 2010. Lgr5(+ve) stem cells drive self-renewal in the stomach and build long-lived gastric units in vitro. Cell Stem Cell 6:25–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Barker N, et al. 2007. Identification of stem cells in small intestine and colon by marker gene Lgr5. Nature 449:1003–1007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Beaulieu PL, et al. 2006. Improved replicon cellular activity of non-nucleoside allosteric inhibitors of HCV NS5B polymerase: from benzimidazole to indole scaffolds. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 16:4987–4993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Berger KL, et al. 2009. Roles for endocytic trafficking and phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase III alpha in hepatitis C virus replication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:7577–7582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Berger KL, Kelly SM, Jordan TX, Tartell MA, Randall G. 2011. Hepatitis C virus stimulates the phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase III alpha-dependent phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate production that is essential for its replication. J. Virol. 85:8870–8883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bianco A, et al. 2012. Metabolism of phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase IIIα-dependent PI4P is subverted by HCV and is targeted by a 4-anilino quinazoline with antiviral activity. PLoS Pathog. 8:e1002576 doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1002576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Blight KJ, McKeating JA, Rice CM. 2002. Highly permissive cell lines for subgenomic and genomic hepatitis C virus RNA replication. J. Virol. 76:13001–13014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Blumental-Perry A, et al. 2006. Phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate formation at ER exit sites regulates ER export. Dev. Cell 11:671–682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Borawski J, et al. 2009. Class III phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase alpha and beta are novel host factor regulators of hepatitis C virus replication. J. Virol. 83:10058–10074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Brandl T, et al. October 2007. Thiazolyl-dihydro-chinazoline. US patent 2007/0238746 A1

- 17. Breitfelder S, et al. October 2007. Thiazolyl-dihydro-cyclopentapyrazole. US patent 2007/0238730 A1

- 18. Cheng H, Leblond CP. 1974. Origin, differentiation and renewal of the four main epithelial cell types in the mouse small intestine. V. Unitarian theory of the origin of the four epithelial cell types. Am. J. Anat. 141:537–561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Coller KE, et al. 2012. Molecular determinants and dynamics of hepatitis C virus secretion. PLoS Pathog. 8:e1002466 doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1002466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. de Chassey B, et al. 2008. Hepatitis C virus infection protein network. Mol. Syst. Biol. 4:230 doi:10.1038/msb.2008.66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Delang L, Vliegen I, Froeyen M, Neyts J. 2011. Comparative study of the genetic barriers and pathways towards resistance of selective inhibitors of hepatitis C virus replication. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55:4103–4113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Drees BE, et al. 2003. Competitive fluorescence polarization assays for the detection of phosphoinositide kinase and phosphatase activity. Comb. Chem. High Throughput Screen. 6:321–330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Egger D, et al. 2002. Expression of hepatitis C virus proteins induces distinct membrane alterations including a candidate viral replication complex. J. Virol. 76:5974–5984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Farhan H, Weiss M, Tani K, Kaufman RJ, Hauri HP. 2008. Adaptation of endoplasmic reticulum exit sites to acute and chronic increases in cargo load. EMBO J. 27:2043–2054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fernandes F, et al. 2011. Phosphoinositides direct equine infectious anemia virus gag trafficking and release. Traffic 12:438–451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ferraris P, Blanchard E, Roingeard P. 2010. Ultrastructural and biochemical analyses of hepatitis C virus-associated host cell membranes. J. Gen. Virol. 91:2230–2237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fre S, Bardin A, Robine S, Louvard D. 2011. Notch signaling in intestinal homeostasis across species: the cases of Drosophila, Zebrafish and the mouse. Exp. Cell Res. 317:2740–2747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Fre S, et al. 2011. Notch lineages and activity in intestinal stem cells determined by a new set of knock-in mice. PLoS One 6:e25785 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0025785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gehrmann T, et al. 1999. Functional expression and characterisation of a new human phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase PI4K230. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1437:341–356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gosert R, et al. 2003. Identification of the hepatitis C virus RNA replication complex in Huh-7 cells harboring subgenomic replicons. J. Virol. 77:5487–5492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Greninger AL, Knudsen GM, Betegon M, Burlingame AL, Derisi JL. 2012. The 3A protein from multiple picornaviruses utilizes the Golgi adaptor protein ACBD3 to recruit PI4KIIIβ. J. Virol. 86:3605–3616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hale BG, et al. 2010. Structural insights into phosphoinositide 3-kinase activation by the influenza A virus NS1 protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107:1954–1959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Heilmeyer LM, Jr, Vereb G, Jr, Vereb G, Kakuk A, Szivák I. 2003. Mammalian phosphatidylinositol 4-kinases. IUBMB Life 55:59–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hilbi H, Weber S, Finsel I. 2011. Anchors for effectors: subversion of phosphoinositide lipids by legionella. Front. Microbiol. 2:91 doi:10.3389/fmicb.2011.00091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hsu NY, et al. 2010. Viral reorganization of the secretory pathway generates distinct organelles for RNA replication. Cell 141:799–811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Jacobson IM, et al. 2011. Telaprevir for previously untreated chronic hepatitis C virus infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 364:2405–2416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kierbel A, et al. 2007. Pseudomonas aeruginosa exploits a PIP3-dependent pathway to transform apical into basolateral membrane. J. Cell Biol. 177:21–27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Konradt C, et al. 2011. The Shigella flexneri type three secretion system effector IpgD inhibits T cell migration by manipulating host phosphoinositide metabolism. Cell Host Microbe 9:263–272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kukolj G, et al. 2005. Binding site characterization and resistance to a class of non-nucleoside inhibitors of the hepatitis C virus NS5B polymerase. J. Biol. Chem. 280:39260–39267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kukolj G, Pause A. August 2003. Self-replicating RNA molecule from Hepatitis C virus. US patent 2003/0148348 A1

- 41. Lagacé L, et al. 2012. In vitro resistance profile of the hepatitis C virus NS3 protease inhibitor BI 201335. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56:569–572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lavanchy D. 2011. Evolving epidemiology of hepatitis C virus. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 17:107–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Li Q, et al. 2009. A genome-wide genetic screen for host factors required for hepatitis C virus propagation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:16410–16415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lim YS, Hwang SB. 2011. Hepatitis C virus NS5A protein interacts with phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase type IIIalpha and regulates viral propagation. J. Biol. Chem. 286:11290–11298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lohmann V, et al. 1999. Replication of subgenomic hepatitis C virus RNAs in a hepatoma cell line. Science 285:110–113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ma H, Blake T, Chitnis A, Liu P, Balla T. 2009. Crucial role of phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase IIIalpha in development of zebrafish pectoral fin is linked to phosphoinositide 3-kinase and FGF signaling. J. Cell Sci. 122:4303–4310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Nakanishi S, Catt KJ, Balla T. 1995. A wortmannin-sensitive phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase that regulates hormone-sensitive pools of inositolphospholipids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 92:5317–5321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Poordad F, et al. 2011. Boceprevir for untreated chronic HCV genotype 1 infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 364:1195–1206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Puyang X, et al. 2010. Mechanism of resistance of hepatitis C virus replicons to structurally distinct cyclophilin inhibitors. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:1981–1987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Reiss S, et al. 2011. Recruitment and activation of a lipid kinase by hepatitis C virus NS5A is essential for integrity of the membranous replication compartment. Cell Host Microbe 9:32–45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Rodgers MJ, Albanesi JP, Phillips MA. 2007. Phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase III-beta is required for Golgi maintenance and cytokinesis in Trypanosoma brucei. Eukaryot. Cell 6:1108–1118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Saad JS, et al. 2006. Structural basis for targeting HIV-1 Gag proteins to the plasma membrane for virus assembly. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:11364–11369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Sangiorgi E, Capecchi MR. 2008. Bmi1 is expressed in vivo in intestinal stem cells. Nat. Genet. 40:915–920 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Sarantis H, et al. 2012. Yersinia entry into host cells requires Rab5-dependent dephosphorylation of PI(4,5)P2 and membrane scission. Cell Host Microbe 11:117–128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Sasaki J, Ishikawa K, Arita M, Taniguchi K. 2012. ACBD3-mediated recruitment of PI4KB to picornavirus RNA replication sites. EMBO J. 31:754–766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Sason H, et al. 2009. Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli subverts phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate and phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate upon epithelial cell infection. Mol. Biol. Cell 20:544–555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Simons JP, et al. 2009. Loss of phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase 2α activity causes late onset degeneration of spinal cord axons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:11535–11539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Szentpetery Z, Szakacs G, Bojjireddy N, Tai A, Balla T. 2011. Genetic and functional studies of phosphatidyl-inositol 4-kinase type IIIα. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1811:476–483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Tai AW, et al. 2009. A functional genomic screen identifies cellular cofactors of hepatitis C virus replication. Cell Host Microbe 5:298–307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Tai AW, Bojjireddy N, Balla T. 2011. A homogeneous and nonisotopic assay for phosphatidylinositol 4-kinases. Anal. Biochem. 417:97–102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Tai AW, Salloum S. 2011. The role of the phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase PI4KA in hepatitis C virus-induced host membrane rearrangement. PLoS One 6:e26300 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0026300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Tian H, et al. 2011. A reserve stem cell population in small intestine renders Lgr5-positive cells dispensable. Nature 478:255–259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Trotard M, et al. 2009. Kinases required in hepatitis C virus entry and replication highlighted by small interference RNA screening. FASEB J. 23:3780–3789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Vaillancourt FH, et al. 2009. Identification of a lipid kinase as a host factor involved in hepatitis C virus RNA replication. Virology 387:5–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Vooijs M, Liu Z, Kopan R. 2011. Notch: architect, landscaper, and guardian of the intestine. Gastroenterology 141:448–459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Weber SS, Ragaz C, Reus K, Nyfeler Y, Hilbi H. 2006. Legionella pneumophila exploits PI(4)P to anchor secreted effector proteins to the replicative vacuole. PLoS Pathog. 2:e46 doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.0020046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Wong K, Meyers R, Cantley LC. 1997. Subcellular locations of phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase isoforms. J. Biol. Chem. 272:13236–13241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Yan Y, Denef N, Tang C, Schüpbach T. 2011. Drosophila PI4KIIIalpha is required in follicle cells for oocyte polarization and Hippo signaling. Development 138:1697–1703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Yang N, et al. 2012. Phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase IIIβ is required for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus spike-mediated cell entry. J. Biol. Chem. 287:8457–8467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Zhang L, et al. 2012. ARF1 and GBF1 generate a PI4P-enriched environment supportive of hepatitis C virus replication. PLoS One 7:e32135 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0032135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]