Abstract

Transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) signaling regulates cell growth and survival. Dysregulation of the TGF-β pathway is common in viral infection and cancer. Latent infection by Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) is required for the development of several AIDS-related malignancies, including Kaposi's sarcoma and primary effusion lymphoma (PEL). KSHV encodes more than two dozen microRNAs (miRs) derived from 12 pre-miRs with largely unknown functions. In this study, we show that miR variants processed from pre-miR-K10 are expressed in KSHV-infected PEL cells and endothelial cells, while cellular miR-142-3p and its variant miR-142-3p_-1_5, which share the same seed sequence with miR-K10a_ +1_5, are expressed only in PEL cells and not in uninfected and KSHV-infected TIME cells. KSHV miR-K10 variants inhibit TGF-β signaling by targeting TGF-β type II receptor (TβRII). Computational and reporter mutagenesis analyses identified three functional target sites in the TβRII 3′ untranslated region (3′UTR). Expression of miR-K10 variants is sufficient to inhibit TGF-β-induced cell apoptosis. A suppressor of the miRs sensitizes latent KSHV-infected PEL cells to TGF-β and induces apoptosis. These results indicate that miR-K10 variants manipulate the TGF-β pathway to confer cells with resistance to the growth-inhibitory effect of TGF-β. Thus, KSHV miRs might target the tumor-suppressive TGF-β pathway to promote viral latency and contribute to malignant cellular transformation.

INTRODUCTION

MicroRNAs (miRs) are a class of ∼22-nucleotide (nt)-long noncoding small RNAs that regulate gene expression at the posttranscriptional level, mainly by binding to the 3′ untranslated region (3′UTR) of the target mRNAs (2). Mature miRs, which are the result of sequential processing of primary transcripts mediated by two RNase III enzymes, Drosha and Dicer, are incorporated into the RNA-induced silencing complex to mediate the repression of translation or degradation of target mRNAs, depending on the degree of complementarity between the miR and its target (3). Recent studies have shown that miRs regulate diverse cellular processes, including differentiation, proliferation, self-renewal, apoptosis, stress responses, and metabolism (4). More than 30% of human genes are posttranscriptionally regulated by miRs (4). Herpesviruses also encode miRs to regulate the functions of both viral and cellular genes, contributing to their infections and associated diseases (12).

Herpesviruses often establish persistent latent infection in the host, which is critical for immune evasion and associated pathogenesis (51). Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV), also known as human herpesvirus 8 (HHV8), is a gammaherpesvirus associated with the development of Kaposi's sarcoma (KS), primary effusion lymphoma (PEL), and multicentric Castleman's disease (MCD) (51). In KSHV-induced malignancies, most tumor cells are latently infected by KSHV, expressing only a subset of limited viral latent genes, including vFLIP (ORF71), vCyclin (ORF72), and LANA (ORF73). These latent genes, located within the latency-associated region, promote cell growth and survival and contribute to viral latency and the development of KSHV-induced tumors (51). KSHV encodes more than two dozen miRs, derived from 12 precursor miRs (pre-miRs) (8, 19, 27, 37, 41, 49). Interestingly, all KSHV pre-miRs are located in the latency-associated genomic locus and expressed during viral latency (7, 8, 19, 37, 41), suggesting their potential roles in regulating this phase of the viral life cycle. In fact, deletion of the 10-pre-miR cluster resulted in the increase of KSHV lytic replication (23, 32). So far, KSHV miRs have been shown to regulate the viral life cycle and host pathways, which might contribute to viral persistent infection and development of KSHV-induced malignancies (1, 5, 17, 18, 23, 25, 26, 31, 32, 36, 38, 39, 42, 46, 53).

Transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) superfamily cytokines play important roles in many essential cellular processes, including proliferation, differentiation, migration, survival, and apoptosis (43, 50). Three isoforms of TGF-β, named TGF-β1, TGF-β2, and TGF-β3, have been identified in mammals. These isoforms bind directly to TGF type II receptor (TβRII), leading to the transphosphorylation of TGF type I receptor (TβRI), which enables its kinase domain to phosphorylate Smad2 and Smad3, the so-called receptor-regulated Smads (R-Smads). Phosphorylated R-Smads form heteromeric complexes with Smad4, which are translocated into the nucleus to regulate the transcription of TGF-β-responsive genes (43). The common result of TGF-β signaling is cell growth inhibition, which is observed in a variety of cell types, including B cells and endothelial cells (43, 50). However, dysregulation of the TGF-β pathway can lead to uncontrolled cell growth (33). Loss of TGF-β responsiveness is a hallmark of many types of cancer (24). In fact, TGF-β is often overexpressed in cancer and is shown to promote the progression of cancer by enhancing the growth of cancer cells and regulating the extracellular microenvironment (6, 24, 33).

A number of viruses, including several tumor viruses, regulate the TGF-β pathway (10, 21, 22, 34, 35, 47). KSHV also encodes several genes to regulate this pathway. Two KSHV lytic proteins interfere with TGF-β signaling, including viral interferon regulatory factor 1 (vIRF1), encoded by ORF-K9, which targets the Smad proteins (44), and the K-bZIP protein, encoded by ORF-K8, which interacts with CREB-binding protein (48). These viral lytic proteins might inhibit the TGF-β pathway to prolong cell survival during KSHV lytic replication. Recently, it has been reported that the KSHV latent protein LANA inhibits TGF-β signaling through epigenetic silencing of TβRII (13), indicating that KSHV also manipulates this pathway during latent infection. In this study, we examined the role of KSHV-encoded miRs in regulating the TGF-β pathway during viral latency. We found that miRs derived from pre-miR-K10 significantly suppress the TGF-β signaling pathway and thus might have an important role in viral latency and KSHV-induced malignancies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture.

Human embryonic kidney 293T cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) containing 10% of fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 100 μg/ml of gentamicin. BCP-1 and Bjab cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 containing 10% FBS and 100 μg/ml of gentamicin. Telomerase-immortalized human dermal microvascular endothelial (TIME) cells, a generous gift of Don Ganem, were cultured in EBM2 medium containing the growth factors human epidermal growth factor (hEGF), human basic fibroblast growth factor (hFGF-B), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), ascorbic acid, hydrocortisone, long R3 insulin-like growth factor 1 (long R3-IGF-1), and heparin at concentrations recommended by the manufacturer (Clonetics, Lonza, Allendale, NJ). To obtain stable 293T, Bjab, and TIME cultures, cells were infected with retroviruses expressing pre-miR-K10 cloned in the pSUPER.retro.puro vector (OligoEngine, Seattle, WA) or a control virus containing the vector and selected with puromycin at 1 μg/ml.

RT-qPCR.

Total RNA was isolated with the TRIzol reagent according to the instructions of the manufacturer (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Expression of the miR-K10 and miR-142-3p variants was quantified using the miRCURY LNA (locked nucleic acid) universal RT microRNA PCR system (Exiqon, Vedbaek, Denmark) with U6 small nuclear RNA as internal standards. All reverse transcription real-time quantitative PCRs (RT-qPCRs) were carried out on an Eppendorf Mastercycler gradient PCR system (Eppendorf, Hauppauge, NY). The expression levels of the target genes were normalized to the expression levels of the internal controls. All reactions were run in triplicate.

Plasmids and miR mimics.

A fragment of the KSHV genome encompassing pre-miR-K10 was cloned into the retroviral vector pSUPER.retro.puro by PCR amplification of the corresponding miR coding fragments from KSHV genomic DNA as previously described (15), followed by insertion of the amplified fragments into the BglII and HindIII sites. The Renilla luciferase sensor construct of miR-K10a (2TK) is a kind gift of Bryan Cullen at Duke University Medical Center. A TβRII full-length 3′UTR luciferase reporter plasmid (TβRII3′UTR WT) was obtained by inserting the full-length 3′UTR of TβRII downstream of the luciferase coding sequence into the pGL3 vector. Mutagenesis was carried out using the wild-type (WT) reporter to generate the mutant reporters TβRII3′UTR Mut1, TβRII3′UTR Mut2, and TβRII3′UTR Mut3, with mutations in the three putative sites. TβRII3′UTR Mut1 was generated using the fusion PCR method. To generate TβRII3′UTR Mut2 and TβRII3′UTR Mut3, NheI and SacI restriction enzyme sites were introduced as the mutated sequences by PCR, respectively (45). All the primers are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sequences of miR mimics, miR suppressors, and PCR primersa

| Name | Sequence (description) |

|---|---|

| miR mimics | |

| miR-K10a | UAGUGUUGUCCCCCCGAGUGGC (sense) |

| CACUCGGGGGGACAACACUCUU (antisense) | |

| miR-K10a_+1_5 | UUAGUGUUGUCCCCCCGAGUGGC (sense) |

| CACUCGGGGGGACAACACUACUU (antisense) | |

| miR-K10b | UGGUGUUGUCCCCCCGAGUGGC (sense) |

| CACUCGGGGGGACAACACCCUU (antisense) | |

| miR-K10b_+1_5 | UUGGUGUUGUCCCCCCGAGUGGC (sense) |

| CACUCGGGGGGACAACACCACUU (antisense) | |

| miR-142-3p | UGUAGUGUUUCCUACUUUAUGGA (sense) |

| CAUAAAGUAGGAAACACUACCUU (antisense) | |

| miR-142-3p_-1_5 | GUAGUGUUUCCUACUUUAUGGA (sense) |

| CAUAAAGUAGGAAACACUAAUU (antisense) | |

| miR suppressors | |

| SC | CATTAAT+G+T+C+G+G+A+C+AACTCAAT |

| Anti-K10a | GCCACTC+G+G+G+G+G+G+A+CAACACTA |

| Anti-142-3p | TCCATAA+A+G+T+A+G+G+A+AACACTACA |

| Primers for constructing miR-pre-K10 expression plasmid | |

| miR-pre-K10-BgIII | TTTAGATCTCCCCCTCCAATCCCAATGCATG (forward) |

| miR-pre-K10-HindIII | GGGAAGCTTAAAAAACTGACACTCTTTGGGAG (reverse) |

| Primers for constructing TβRII 3′UTR WT and mutant reporters | |

| WT | CCCAATACCAGTGGGGTTCAAAACATTCAA (forward) |

| CTCCTCGAGCTCTTCTGGGGCAGGCTGGGCCAT (reverse) | |

| Mut1 | TCTAGTTTTCTATACATTGTGGAATGGGTTCCATCTTT (forward) |

| AAAGATGGAACCCATTCCACAATGTATAGAAAACTAGA (reverse) | |

| Mut2 | TATAGCTAGCTATACATAAAGGGAAAGTTTT (forward) |

| TATACTCGAGGCTAGCAAAAAAGTCAGTATTTTTAGGAA (reverse) | |

| Mut3 | TATAGAGCTCTCAGCTGTACTCATGTATTAA (forward) |

| TATACTCGAGGAGCTCCCATAAAAGAATAAAACTTTCC (reverse) |

Symbol “+” before the letter indicates an LNA-modified base. SC, scrambled control.

miR mimics were commercially synthesized based on the sequences of mature miRs (Table 1) (Ambion, Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY). A scrambled oligonucleotide containing random sequence was obtained from the manufacturer (Ambion) and used as a control.

Luciferase reporter assay.

Cells were plated in 24-well plates 24 h before transfection. The luciferase reporter construct pSBE-luc or pMBE-luc, containing a TGF-β-responsive Smad-binding element or its mutant, respectively (52), at 50 ng, and the pSV-β-galactosidase expression plasmid at 10 ng (Promega, Madison, WI) were transiently cotransfected into the cells using the TargetfactF2 transfection reagent according to the manufacturer's instructions (Targeting Systems, El Cajon, CA). At 24 h posttransfection, the cells were treated with TGF-β1 at 1.0 ng/ml for another 24 h and collected, and the luciferase and β-galactosidase activities were measured using the luciferase assay system and β-galactosidase enzyme assay system, respectively (Promega). Luciferase activity was normalized to β-galactosidase activity. All reporter assays were performed three times, each in triplicate. Results were calculated as averages ± standard errors of the means (SEM) from one representative experiment (see Fig. 1, 3, 5, and 11) or averages ± standard deviations (SD) from three independent experiments (see Fig. 2, 7, and 10).

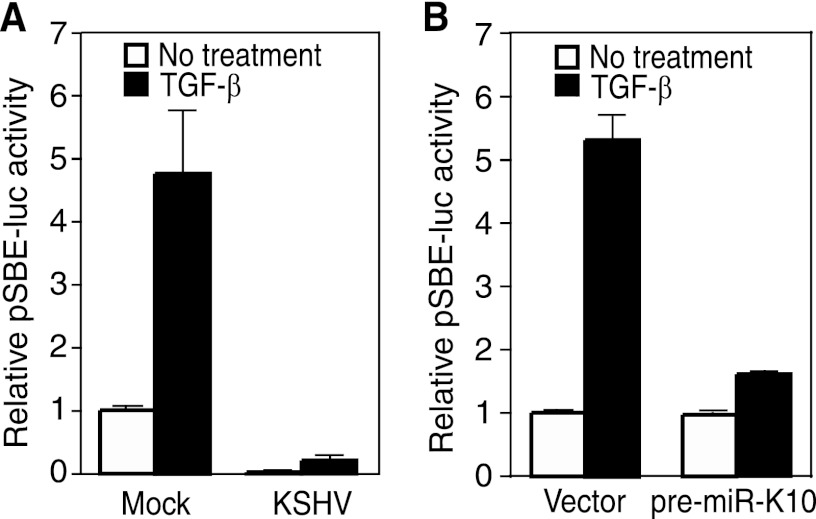

Fig 1.

TGF-β signaling is inhibited by miRs processed from KSHV pre-miR-K10. (A) KSHV infection suppresses TGF-β signaling, shown in a reporter assay. Mock- or KSHV-infected TIME cells were transiently transfected with pSBE4-Luc and β-galactosidase constructs for 24 h, treated with 1.0 ng/ml TGF-β1 for an additional 24 h, and measured for relative luciferase activities. (B) Inhibition of TGF-β signaling by miRs derived from KSHV pre-miR-K10. TIME cells were transiently cotransfected with pSBE4-Luc and β-galactosidase constructs together with pre-miR-K10 or a vector control for 24 h, treated with 1.0 ng/ml TGF-β1 for an additional 24 h, and measured for relative luciferase activities.

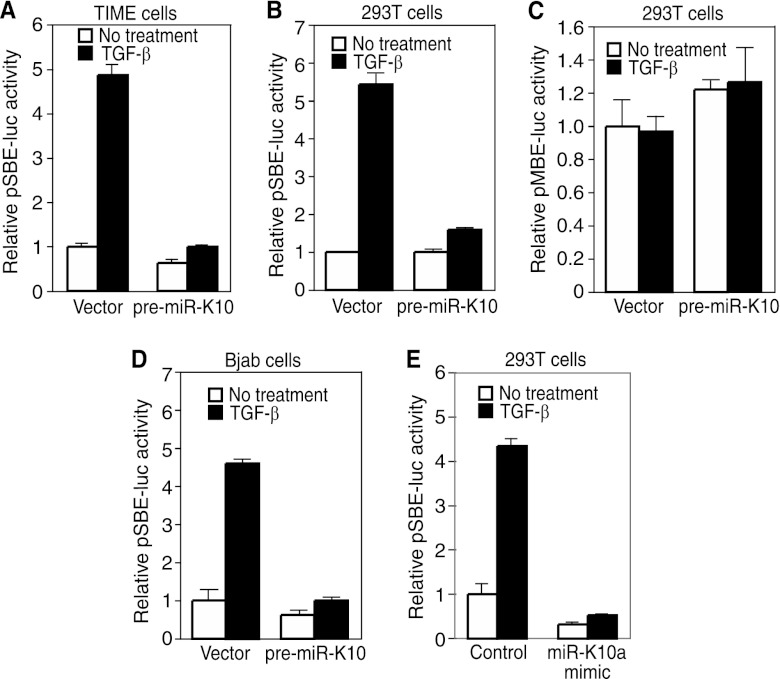

Fig 3.

KSHV miR-K10 variants inhibit TGF-β signaling. (A to D) miR-K10 variants suppress TGF-β signaling, shown in a reporter assay. Stable TIME cells (A), Bjab cells (B), or 293T cells (C and D) expressing pre-miR-K10 or a vector control were transfected with pSBE4-Luc (A, B, and C) or pMBE-luc (D) together with the β-galactosidase construct for 24 h, treated with 1.0 ng/ml TGF-β1 for an additional 24 h, and measured for relative luciferase activities. (E) KSHV miR-K10a mimic suppresses TGF-β signaling, shown in a reporter assay. MiR-K10a mimic or a scrambled control was cotransfected into 293T cells together with pSBE4-Luc and β-galactosidase constructs for 24 h, treated with TGF-β1 for an additional 24 h, and measured for relative luciferase activities.

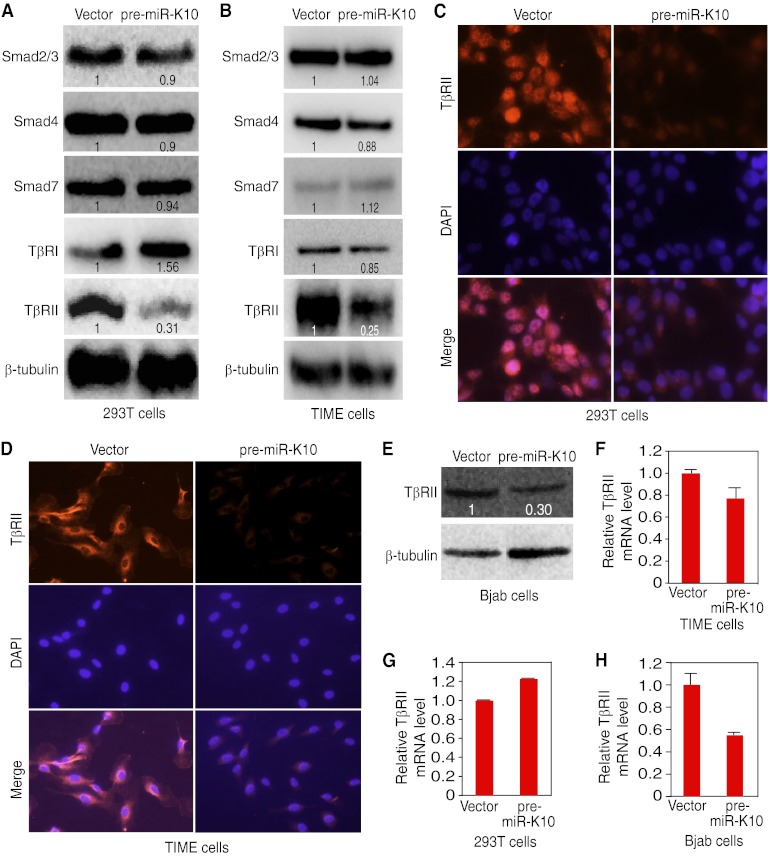

Fig 5.

KSHV miR-K10 variants downregulate the level of the TβRII protein. (A and B) Expression of pre-miR-K10 reduces the protein level of TβRII but not other components of the TGF-β pathway in 293T cells (A) or TIME cells (B). Protein levels of Smad2/3, Smad4, Smad7, TβRI, and TβRII in stable cells expressing pre-miR-K10 or a vector control were detected by Western blotting. Numbers shown on the lanes are the relative intensities after calibration with β-tubulin. (C and D) Expression of pre-miR-K10 reduces the protein level of TβRII in 293T cells (C) or TIME cells (D), shown by immunofluorescence staining. The TβRII protein in stable cells expressing pre-miR-K10 or a vector control was examined by immunofluorescence assay. (E) The level of the TβRII protein was reduced in Bjab cells expressing pre-miR-K10. The TβRII protein was detected by Western blotting. Numbers shown on the lanes are the relative intensities after calibration with β-tubulin. (F to H) KSHV miR-K10 variants don't affect the level of TβRII mRNA. TβRII mRNA levels in stable TIME cells (F), 293T cells (G), or Bjab cells (H) expressing pre-miR-K10 or a vector control were measured by RT-qPCR.

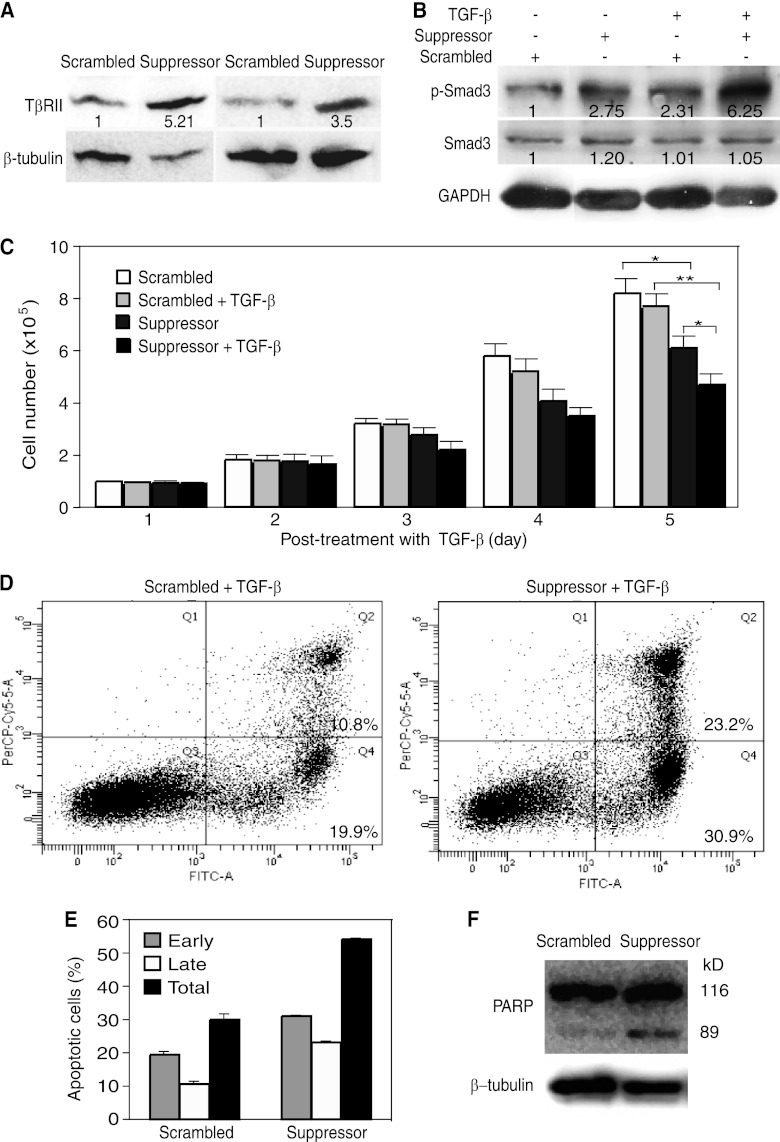

Fig 11.

A suppressor of miR-K10a increases TβRII expression, enhances TGF-β signaling, sensitizes cells to apoptosis, and decreases cell growth in KSHV-infected BCP-1 cells. (A) A suppressor of miR-K10a restores the expression of the TβRII protein in latent KSHV-infected BCP-1 PEL cells. BCP-1 cells transfected with 10 nM miR-10a suppressor or a scrambled oligonucleotide for 4 days were examined for the TβRII protein by Western blotting. Numbers shown on the lanes are the relative intensities after calibration with β-tubulin. (B) A suppressor of miR-K10a restores the responsiveness of latent BCP-1 cells to TGF-β. BCP-1 cells transfected with 10 nM miR-10a suppressor or a scrambled oligonucleotide for 4 days were treated with 1.0 ng/ml of TGF-β1 for 20 min and collected for measurement of pSmad3 by Western blotting. Numbers shown on the lanes are the relative intensities after calibration with GAPDH. (C) A suppressor of miR-K10a sensitizes BCP-1 cells to TGF-β-induced cell growth arrest. BCP-1 cells transfected with 10 nM miR-K10a suppressor or a scrambled oligonucleotide for 24 h were treated with 10 ng/ml of TGF-β1 for another 5 days. The cell number in each well was counted daily. Data are shown as averages ± SEM from 3 repeats. (D to F) A suppressor of miR-K10a sensitizes BCP-1 cells to apoptosis. BCP-1 cells transfected with 10 nM miR-K10a suppressor or a scrambled oligonucleotide for 24 h were treated with 1.0 ng/ml of TGF-β1 for another 48 h. Cells were collected and examined for apoptotic cells by dual staining of annexin V (x axis) and PI (y axis), followed by flow cytometry analysis (D), and results are summarized as the averages ± SEM from 3 repeats (E) or PARP cleavage by Western blotting (F).

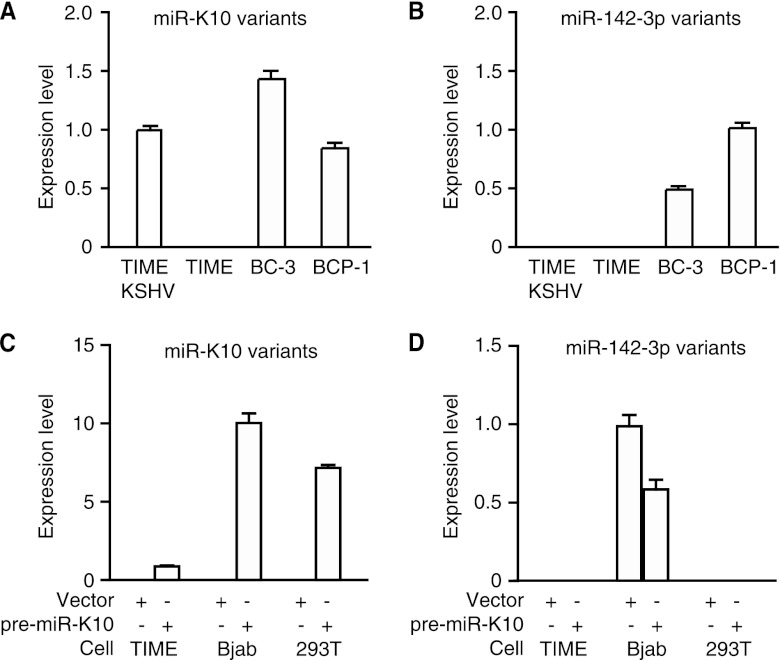

Fig 2.

Detection of miR-K10 and miR-142-3p variants by RT-qPCR in KSHV-infected cells and TIME, Bjab, and 293T stable cells expressing pre-miR-K10 and a vector control. (A and B) Detection of miR-K10 variants (A) or miR-142-3p variants (B) in TIME cells and KSHV-infected BC-3, BCP-1, and TIME-KSHV cells. (C and D). Detection of miR-K10 variants (C) or miR-142-3p variants (D) in stable TIME, Bjab, and 293T cultures of pre-miR-K10 or a vector control.

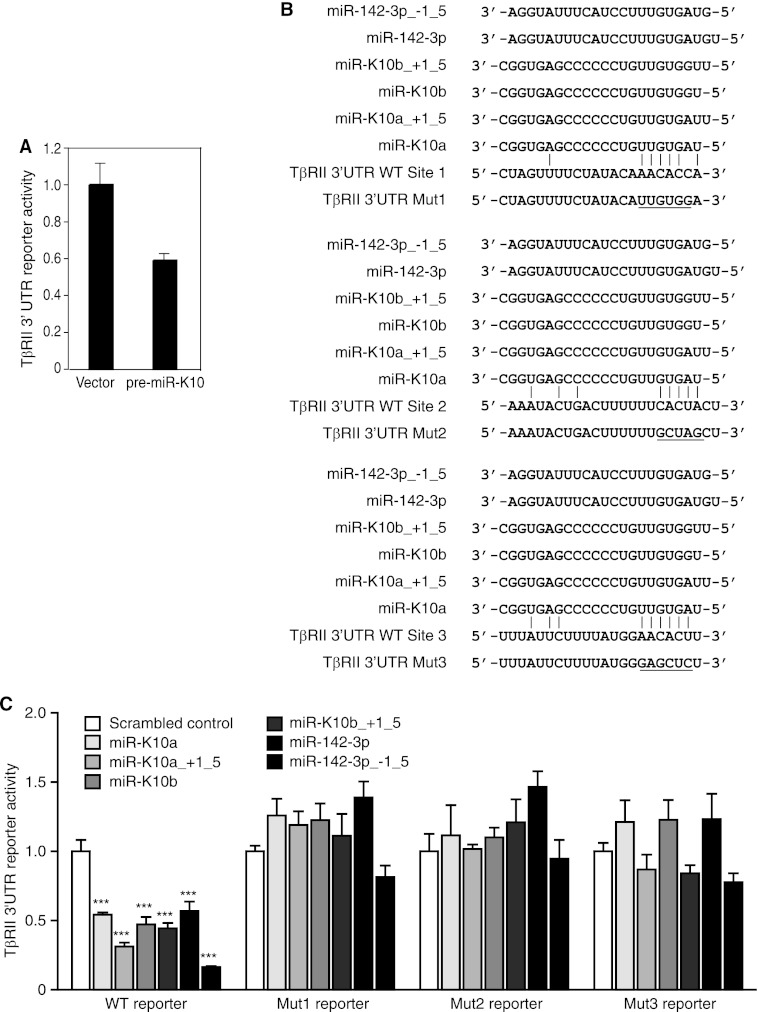

Fig 7.

KSHV miR-K10 and miR-142-3p variants target TβRII 3′UTR. (A) KSHV miR-K10 variants suppress full-length TβRII 3′UTR reporter activity. Stable 293 cells expressing pre-miR-K10 or a vector control were transfected with the full-length TβRII 3′UTR reporter construct (TβRII 3′UTR WT) and a β-galactosidase expression construct for 48 h and measured for relative luciferase activities. (B) Sequence alignment of miR-K10 and miR-142-3p variants with the TβRII 3′UTR WT reporter and mutant reporters TβRII 3′UTR Mut1, TβRII 3′UTR Mut2, or TβRII 3′UTR Mut3, with mutation in the respective putative targeting site. (C) Mutation of any of the three predicted sites abolishes inhibition of TβRII 3′UTR reporter activity by mimics of miR-K10 and miR-142-3p variants. Cells were cotransfected with mimics or a scrambled mimic control together with TβRII 3′UTR luciferase reporters and the pRL-TK construct for 48 h and measured for relative luciferase activities using pRL-TK as a calibration control.

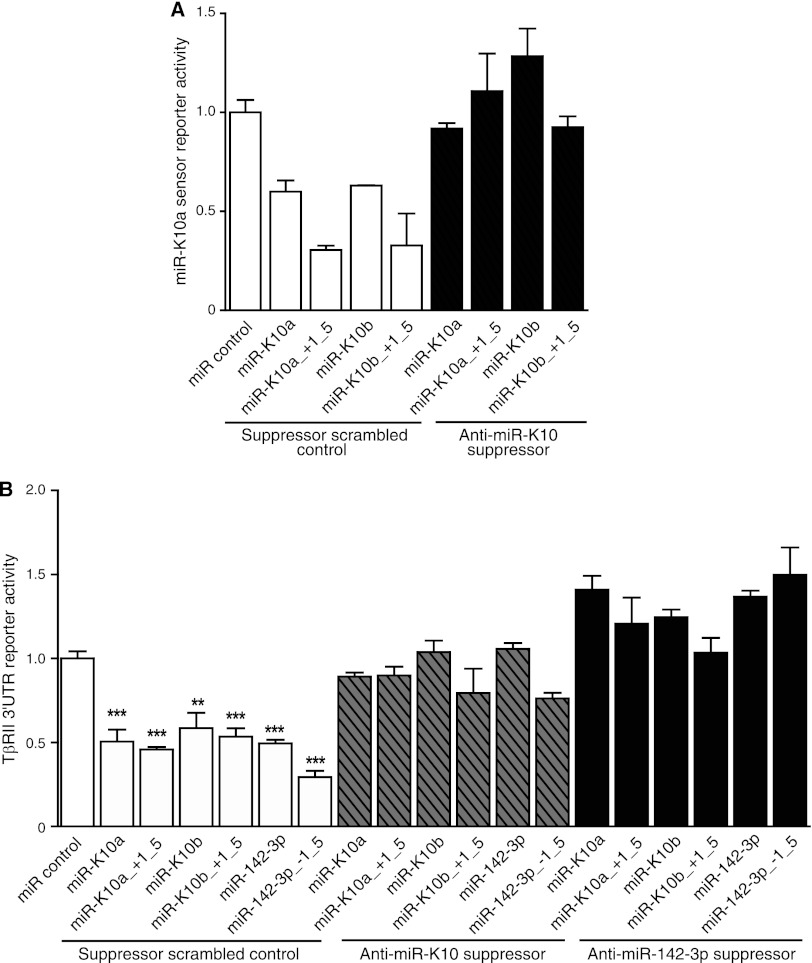

Fig 10.

A suppressor of miR-K10a inhibits the function of all miR-K10 and miR-142-3p variants. (A) A suppressor of miR-K10a relieved the inhibition of the miR-K10a sensor reporter by all miR-K10 variants. Cells were cotransfected with a miR-K10a sensor luciferase reporter, the pRL-TK construct, mimics, or a scrambled mimic control, together with a suppressor of miR-K10a or a scrambled suppressor control for 48 h, and measured for relative luciferase activities using pRL-TK as a calibration control. (B) A suppressor of either miR-K10a or miR-142-3p relieved the inhibition of the TβRII3′UTR WT reporter by all miR-K10 and miR-142-3p variants. Cells were cotransfected with the TβRII3′UTR WT luciferase reporter, the pRL-TK construct, mimics, or a scrambled mimic control, together with a suppressor of miR-K10a or miR-142-3p, or a scrambled suppressor control for 48 h, and measured for relative luciferase activities using pRL-TK as a calibration control.

Reporter assays for the 3′UTR reporters were carried out in 48-well plates. For each well, cells were cotransfected with 20 ng of the luciferase reporter plasmid, 2 ng of pRL-TK (Promega, Madison, WI), and a 50 nM concentration of a miR mimic with or without the presence of 100 nM respective LNA suppressor. Cells were collected at 48 h posttransfection and analyzed using the Dual-Luciferase reporter assay system (Promega). The pRL-TK vector providing the constitutive expression of Renilla luciferase was used as an internal control. Transfection was performed in duplicate, and all experiments were independently repeated at least three times.

Western-blotting.

Equal amounts of protein samples were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes as previously described (14). The blots were blocked with 5% nonfat milk and incubated with primary antibody followed by a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Specific bands were revealed with chemiluminescence substrates (Roche, Nutley, NJ) and recorded with an IS2000MM imaging scanner (Eastman Kodak Company, Rochester, NY). Signals were quantified using IS2000MM imaging software. We ensured that all quantifications were performed on images/exposures that were in the linear ranges. Numbers shown on all figures were quantifications from the actual blots after calibration with the loading control β-tubulin or glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH). Antibodies to TβRII and Smad2/3, Smad3, Smad4, and Smad7 were obtained from Abcam (Cambridge, MA). Antibodies to p-Smad3, β-tubulin, and GAPDH were from Sigma. Antibodies to TβRI and PARP were from Santa Cruz (Santa Cruz, CA). All antibodies were used at 1:1,000 dilutions.

Immunofluorescence assay.

Cells fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde and blocked with 10% FBS were incubated with primary antibody. Specific signal was detected with an Alexa Fluor 568 secondary antibody (Invitrogen). The cells were counterstained with DAPI (4′, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole). Images were observed and recorded with a Zeiss Axiovert 200M fluorescence microscope (Carl Zeiss Microimaging Inc., Thornwood, NY).

Apoptosis assay.

Apoptotic cells were detected by propidium iodide (PI) staining and with a fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-annexin V apoptosis detection kit (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) following treatment with TGF-β1 at 1 ng/ml for the indicated times. Cells were washed twice with cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and resuspended at 106 cells per ml in the binding buffer. Annexin V-FITC (5 μl) and PI (5 μl) were added to 100 μl of cells. The mixture was incubated at room temperature for 15 min in the dark. An additional 400 μl of binding buffer was added before the cells were analyzed with a flow cytometer. Early apoptotic cells were those that were positive only for annexin V, while late apoptotic cells were positive for both annexin V and PI.

MiR suppressors and transfection.

LNA suppressors were chemically synthesized by Exiqon (Woburn, MA). The sequences are listed in Table 1. LNA oligonucleotides at 10 nM were transfected into BCP-1 cells to suppress the corresponding miRs using the siPORT NeoFX transfection agent according to the manufacturer's instructions (Applied Biosystems).

Complementation by stable expression of TβRII.

Bjab cells were infected with TβRII-inducible lentivirus particles (LVP054; GenTarget, San Diego, CA) or negative control lentiviral particles (LVP-Null-RB). The cultures were selected with 5 μg/ml blasticidin (Sigma). Stable TβRII cells were transfected with miR-K10a mimics or a scrambled control and treated with TGF-β1 at 5 ng/ml. At 4 days posttreatment, cells were collected and apoptotic cells were examined.

RESULTS

KSHV miR-K10a and its variant block TGF-β signaling.

We determined whether KSHV regulates the TGF-β pathway during viral latent infection. TIME cells latently infected by KSHV were examined for their responsiveness to TGF-β using a luciferase reporter, pSBE-luc, containing a Smad-binding element (52). As shown in Fig. 1A, mock-infected control cells responded robustly to TGF-β treatment. However, KSHV-infected cells had a low basal level of luciferase activity and a minimal response to TGF-β, indicating the blockage of the TGF-β pathway in these latent cells. We then used the same luciferase reporter assay to identify KSHV miRs that might regulate the TGF-β pathway. While several miRs were initially found to alter the cell response to TGF-β, subsequent experiments confirmed only that pre-miR-K10 dramatically blocked TGF-β signaling (Fig. 1B).

Because of RNA editing, the pre-miR-K10 gene can be processed into two miR variants, miR-K10a and miR-K10b, which differ in a single nucleotide (37). Recent results from deep sequencing of KSHV-infected cells indicate that miR-K10a and miR-K10b further exhibit 5′ nucleotide variations, in that each mature miR is longer by a single nucleotide at the 5′ end, generating two other miR variants, miR-K10a_ +1_5 and miR-K10b_ +1_5 (16, 49). Furthermore, cellular miR-142-3p has a variant, miR-142-3p_-1_5, that shares the same seed sequence with miR-K10a_ +1_5 (16, 49). Since these miR variants could potentially share the same targets and regulate the TGF-β pathway, we developed RT-qPCR assays based on their sequence variations to detect their expression levels, which could facilitate the definition of their functions. RT-qPCR assays designed to detect individual miR-K10 variants effectively detected the mimics of their respective miR-K10 variants; however, all of them also detected all other miR-K10 variants with similar sensitivities (Table 2). These assays didn't detect miR-142-3p and its variant miR-142-3p_-1_5. Similarly, the two RT-qPCR assays designed for miR-142-3p and miR-142-3p_-1_5 effectively detected their own miRs as well as each other but not the miR-K10 variants (Table 2). Examination of KSHV-infected cells indicated that KSHV-infected TIME cells (TIME-KSHV), BC-3, and BCP-1 cells had similar expression levels of miR-K10 variants while no expression of miR-K10 variants was found in uninfected TIME cells, as expected (Fig. 2A). BC-3 and BCP-1 cells also had similar expression levels of miR-142-3p and miR-142-3p_-1_5. Surprisingly, no expression of miR-142-3p and miR-142-3p_-1_5 was detected in TIME and TIME-KSHV cells (Fig. 2B).

Table 2.

Detection of mimics of individual miR variants by using specific RT-qPCRsa

| miR mimic | Detection (CT value) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SC | miR-K10a | miR-K10a_+1_5 | miR-K10b | miR-K10b_+1_5 | miR-142-3p | miR-142-3p_-1_5 | |

| miR-K10a | 28.82 | 7.86 | 5.70 | 9.97 | 9.70 | 35.11 | 29.91 |

| miR-K10a_ +1_5 | 27.30 | 6.68 | 4.97 | 8.65 | 8.52 | 33.55 | 28.07 |

| miR-K10b | 27.52 | 6.85 | 5.19 | 9.14 | 8.66 | 34.29 | 28.22 |

| miR-K10b_ +1_5 | 28.11 | 7.01 | 5.59 | 8.57 | 8.68 | 34.75 | 28.35 |

| miR-142-3p | ND | ND | ND | 31.97 | 34.38 | 8.45 | 6.41 |

| miR-142-3p_-1_5 | ND | ND | 34.91 | 31.61 | ND | 8.30 | 6.39 |

SC, scrambled control; ND, not detectable.

To examine the regulation of the TGF-β pathway by miR-K10 variants, we established stable cell cultures expressing pre-miR-K10 or the vector control in TIME, 293T, and Bjab cells since these cells are responsive to TGF-β treatment (data not shown). RT-qPCR showed that pre-miR-K10 stable cultures of Bjab and 293T cells had similar expression levels of miR-K10 variants; however, that of TIME cells was 5- to 10-fold lower (Fig. 2C). Compared to KSHV-infected cells, all pre-miR-K10 stable cultures had approximately 2 orders of magnitude lower expression levels of miR-K10 variants. Despite lower expression levels in the stable cells, miR-K10 variants were functional in these cells, as illustrated in the following sections. While pre-miR-K10 and vector control stable cultures of Bjab had similar expression levels of miR-142-3p and miR-142-3p_-1_5, cultures of all TIME and 293T cells were negative (Fig. 2D). To determine the extent of RNA editing, which might contribute to the variations of the miR-K10 variants, we performed sequence analysis of the primary miR-K10 cloned from the cDNAs of stable TIME, 293T, and Bjab cultures. While this assay cannot distinguish the 5′ variants, it could detect variations caused by RNA editing. Out of 20 clones analyzed for each culture, we detected only miR-K10a variants and not miR-K10b variants. Thus, miR-K10a variants are the only likely forms expressed in these stable cultures, which are also the focus of this study.

To examine the inhibition of the TGF-β pathway by miR-K10a variants, we performed a pSBE-luc reporter assay with the pre-miR-K10 stable cultures. In TIME and 293T cells, control cells were highly responsive to TGF-β; however, those expressing pre-miR-K10 were not (Fig. 3A and B). A control luciferase reporter, pMBE-luc, containing a mutated Smad-binding element, was not responsive to TGF-β (Fig. 3C). The responsiveness of Bjab cells to TGF-β is controversial (9, 20). As shown in Fig. 3D, control Bjab cells were highly responsive to TGF-β despite the expression of miR-142-3p and miR-142-3p_-1_5, indicating that inhibition of the TGF-β pathway by miR-142-3p and miR-142-3p_-1_5, if it existed, was inefficient. Expression of pre-miR-K10 rendered Bjab cells unresponsive to TGF-β (Fig. 3D). These results indicate that miR-K10a variants are the primary miRs that mediate the inhibition of the TGF-β pathway in the pre-miR-K10 stable cultures. Consistent with these results, a synthetic miR-K10a mimic efficiently blocked TGF-β responsiveness (Fig. 3E).

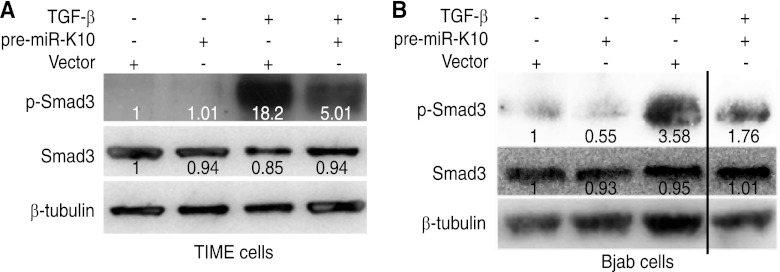

To confirm the results of reporter assays, we examined the phosphorylation status of the Smad3 protein. Figure 4 showed reduced levels of p-Smad3 following TGF-β treatment in TIME and Bjab cells stably expressing pre-miR-K10 compared to levels in cells expressing the vector control, confirming the inhibition of TGF-β pathway by these miR-K10a variants.

Fig 4.

KSHV miR-K10 variants inhibit Smad3 phosphorylation. (A) Inhibition of Smad3 phosphorylation in TIME cells stably expressing pre-miR-K10. (B) Inhibition of Smad3 phosphorylation in Bjab cells stably expressing pre-miR-K10. Cells grown at the exponential phase were treated with 1.0 ng/ml of TGF-β1 for 20 min, collected, and measured for p-Smad3 by Western blotting. Numbers shown on the lanes are the relative intensities after calibration with β-tubulin.

MiR-K10a variants target TβRII.

The primary mode of action of a miR is translational repression of the target mRNA (3). While miR-K10a variants affected the phosphorylated status of Smad3, they had no effect on its total protein level (Fig. 4). To identify the target(s) of miR-K10a variants, we further examined the protein levels of other major mediators in the TGF-β pathway. Expression of pre-miR-K10 in 293T and TIME cells had no obvious effect on the protein levels of Smad2/3, Smad4, Smad7, and TβRI. In contrast, pre-miR-K10 reduced the TβRII protein levels in 293 and TIME cells by 69% and 75%, respectively (Fig. 5A and B). Immunofluorescence staining confirmed that the TβRII protein level was reduced in pre-miR-K10 stable cells compared to that in cells with the vector control (Fig. 5C and D). Similarly, in stable Bjab cells, pre-miR-K10 reduced the TβRII protein level by 70% (Fig. 5E). RT-qPCR showed that TβRII mRNA was slightly decreased in TIME and Bjab cells but increased in 293 cells following the expression of pre-miR-K10 (Fig. 5F to H). Nevertheless, these assays measured total mRNA levels and thus could not exclude the possibility that miR-K10a variants might also affect the stability of TβRII mRNA.

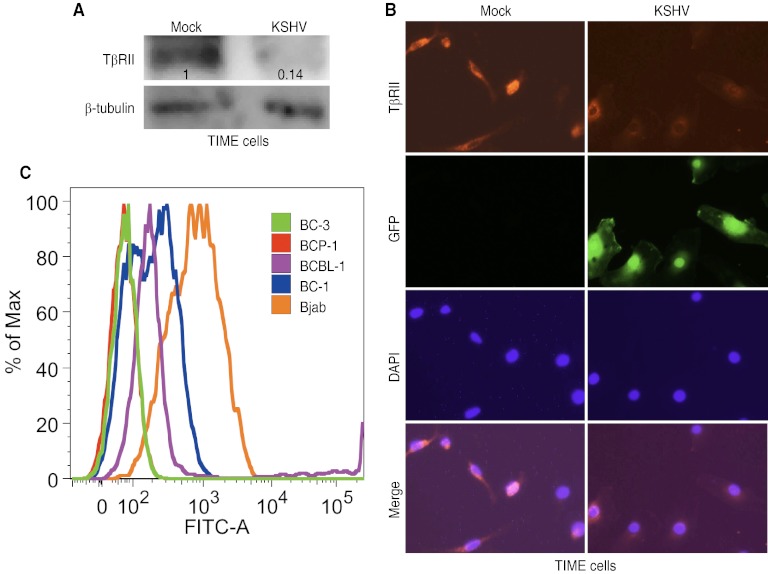

To determine whether the reduction in TβRII protein levels is present during KSHV infection, we examined latent KSHV-infected TIME cells. The TβRII protein level was reduced by 86% in KSHV-infected cells compared to that in mock-infected control cells (Fig. 6A). Immunofluorescence staining confirmed that the TβRII protein level was reduced in KSHV-infected TIME cells compared to that in uninfected control cells (Fig. 6B). We also examined the expression of TβRII in several KSHV-infected PEL cell lines by flow cytometry. BC-3 and BCP-1 cells had no detectable TβRII expression, while BCBL-1 and BC-1 cells had low levels of TβRII expression (Fig. 6C). In contrast, KSHV-negative Bjab cells had robust expression of TβRII, which was consistent with their high responsiveness to TGF-β treatment (Fig. 3D).

Fig 6.

KSHV infection downregulates the level of the TβRII protein. (A) KSHV infection reduces the protein level of TβRII in TIME cells. Protein levels of TβRII in mock and latently KSHV-infected TIME cells were detected by Western blotting. Numbers shown on the lanes are the relative intensities after calibration with β-tubulin. (B) KSHV infection reduces the protein level of TβRII in TIME cells, shown by immunofluorescence staining. TβRII protein in mock- or KSHV-infected TIME cells was examined by immunofluorescence assay. (C) Expression of TβRII in the KSHV-infected PEL cell lines BC-3, BCP-1, BCBL-1, and BC-1 and the KSHV-negative cell line Bjab, analyzed by flow cytometry.

MiR usually binds to the 3′UTR of the target for its action (3). Using a full-length 3′UTR luciferase reporter of TβRII, we showed that stable expression of pre-miR-K10 reduced 40% of the luciferase activity compared to that with the vector control (Fig. 7A). Computational prediction with the SVMicrO miR target prediction program (28) identified three putative targeting sites of miR-K10 and miR-142-3p variants in the 3′UTR of TβRII with a partial match in bases 1 to 7 of the seed sequence at the 5′ end of the miRs (Fig. 7B). To determine whether these putative sites are functional, we performed mutagenesis with the full-length 3′UTR luciferase reporter of TβRII (WT) and generated luciferase reporters with mutations on these individual sites (Mut1, Mut2, and Mut3). We then tested the effects of mimics of all of the miR-K10 and miR-142-3p variants on the WT and mutant reporters (Fig. 7C). Mimics of miR-K10 and miR-142-3p variants reduced the luciferase activity of the WT reporter 45% to 82% compared to that with the control mimic. Interestingly, miR-142-3p_-1_5 caused the most dramatic reduction, reaching 82%. Mutation of any of the predicted target sites completely abolished the inhibition of reporter activities by the miR-K10 and miR-142-3p variants, indicating that all three sites are functional and essential for the efficient inhibition of the WT reporter by the miR variants.

MiR-K10a variants protect cells from TGF-β-induced cell growth arrest and apoptosis.

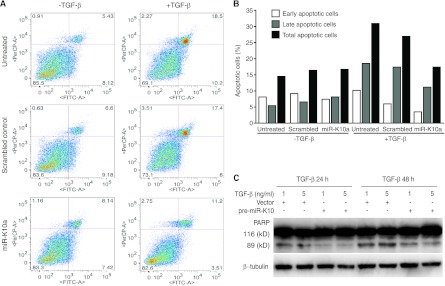

TGF-β signaling generally leads to cell growth arrest and apoptosis in normal cells (43, 50). Because miR-K10a variants targeted TβRII and inhibited the TGF-β pathway (Fig. 3 to 5), we determined if these two variants could protect cells from apoptosis. Without treatment with TGF-β, Bjab cells and Bjab cells transfected with a miR-K10a mimic and a scrambled mimic control had apoptotic rates ranging from 14.5% to 16.7% (Fig. 8). Treatment with TGF-β increased apoptosis of Bjab cells and Bjab cells transfected with a scrambled control to 30.9% and 26.9%, respectively. However, the apoptotic rate of Bjab cells transfected with a miR-K10a mimic remained almost unchanged at 17.4%. We further examined PARP cleavage in stable pre-miR-K10 Bjab cells. Without TGF-β treatment, PARP cleavage was not detected in Bjab cells expressing either the vector control or pre-miR-K10 (data not shown). While TGF-β treatment induced PARP cleavage in Bjab cells expressing the vector control, expression of pre-miR-K10 protected Bjab cells from TGF-β-induced PARP cleavage (Fig. 8C). These results indicate that the miR-K10a variants were sufficient to protect cells from apoptosis. To further determine if the antiapoptotic effect of the miR-K10a mimic was due to specific targeting of TβRII, we determined if expression of TβRII without the native 3′UTR was sufficient to sensitize the cells to TGF-β-induced apoptosis. Bjab cells were transduced with lentiviruses expressing TβRII without the native WT 3′UTR or a vector control. Again, untreated Bjab cells and Bjab cells transfected with a miR-K10a mimic and a scrambled mimic control had apoptotic rates ranging from 16.7% to 19.6% (Fig. 9). Expression of TβRII increased the level of apoptotic cells to 25% to 25.4%, which was probably due to the basal level of expression of TGF-β in Bjab cells. As in the previous experiment, treatment with TGF-β increased apoptosis of Bjab cells and Bjab cells transfected with a scrambled control to 29.5% and 26.3%, respectively, while the apoptosis rate of Bjab cells transfected with the miR-K10a mimic remained at 15.7%. Expression of TβRII sensitized the cells transfected with the miR-K10a mimic to apoptosis and increased the apoptosis rate to 31.5%, which was similar to the apoptotic rates of Bjab cells (32%) and Bjab cells transfected with a scrambled control (37.6%). Together, these results indicated that the antiapoptotic effect of the miR-K10a mimic was indeed through specific targeting of TβRII.

Fig 8.

KSHV miR-K10 variants inhibit TGF-β-induced apoptosis. (A) A mimic of miR-K10a protects cells from TGF-β-induced apoptosis. Bjab cells were transfected with either a mimic of miR-K10a or a scrambled control and treated with TGF-β1 at 5 ng/ml. At 4 days posttreatment, cells were collected and apoptotic cells were examined. x and y axes indicate annexin V and PI staining intensities, respectively. (B) Summary of percentages of early, late, and total apoptotic cells in panel A. (C) KSHV miR-K10 variants inhibit TGF-β-induced PARP cleavage. Stable pre-miR-K10 Bjab cells treated with TGF-β1 at 1 and 5 ng/ml for 24 h or 48 h were harvested and examined for PARP cleavage by Western blotting.

Fig 9.

Expression of TβRII without the native 3′UTR abolishes the inhibition of TGF-β-induced apoptosis by a mimic of KSHV miR-K10a. (A) Bjab cells with stable expression of TβRII without the native 3′UTR or a vector control were transfected with a mimic of miR-K10a or a scrambled control and treated with TGF-β1 at 5 ng/ml. At 4 days posttreatment, cells were collected, and apoptotic cells were examined. x and y axes indicate annexin V and PI staining intensities, respectively. (B) Summary of percentages of early, late, and total apoptotic cells in panel A. (C) Examination of TβRII expression in Bjab cells by flow cytometry. Bjab cells with stable expression of TβRII without the native 3′UTR or a vector control were transfected with a mimic of miR-K10a or a scrambled control for 4 days and examined for expression of TβRII.

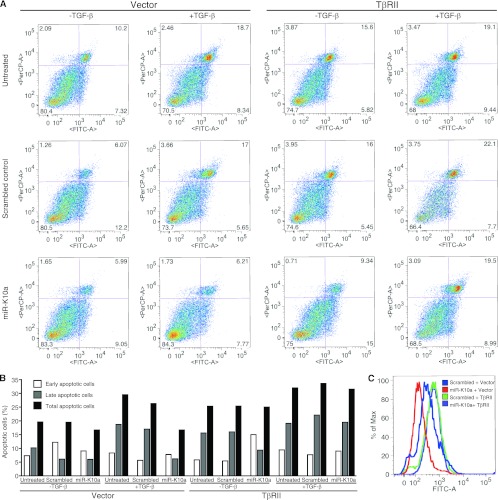

To examine if miR-K10 variants suppress the TGF-β pathway in the context of KSHV infection, we developed a locked nucleic acid (LNA)-based suppressor. Using a miR-K10a sensor reporter, we tested the effect of the suppressor on all miR-K10 variants. As shown in Fig. 10A, all miR-K10 variants effectively inhibited reporter activity, with efficiencies ranging from 39% to 72%. Better efficiencies were observed with miR-K10a_ +1_5 and miR-K10b_ +1_5, at 72% and 70%, respectively. The miR-K10 suppressor effectively relieved the inhibition effect of all miR variants. The suppressor also effectively relieved the inhibition of the full-length 3′UTR luciferase reporter of TβRII by all miR-K10 variants, as well as miR-142-3p and miR-142-3p_-1_5 (Fig. 10B), which was consistent with the observations that these miRs share the same seed sequence. As expected, a suppressor developed based on the miR-142-3p sequence also effectively relieved the inhibition of the full-length 3′UTR luciferase reporter of TβRII by all miR-K10 and miR-142 variants. These results indicate that both suppressors could inhibit the function of all miR-K10 and miR-142 variants.

We further determined if the miR-K10 suppressor could sensitize KSHV-infected cells to TGF-β. Transfection of the suppressor increased the TβRII level by 5.21- and 3.5-fold in BCP-1 cells compared to that in cells transfected with the scrambled control in two independent experiments (Fig. 11A), indicating that suppression of TβRII expression could be at least partially attributed to miR-K10 and miR-142 variants in these cells.

A previous study has shown that TGF-β is highly expressed in PEL cells (13). Consistently, we detected a low level of p-Smad3 in BCP-1 cells without TGF-β treatment. Transfection with the suppressor increased the p-Smad3 level by 2.75-fold compared to that for the cells transfected with the scrambled control (Fig. 11B). While TGF-β increased the p-Smad3 level by 2.31-fold in cells transfected with the scrambled control, that in cells transfected with the suppressor was further increased to 6.25-fold (Fig. 11B), indicating that the miR-K10 and miR-142 variants suppress TGF-β signaling in latently KSHV-infected cells.

KSHV-infected PEL cells are resistant to TGF-β-induced cell growth arrest and apoptosis. Since the miR-K10 suppressor restored the responsiveness of BCP-1 cells to TGF-β (Fig. 11B), we examined the protective effect of miR variants in these latently KSHV-infected cells. As shown in Fig. 11C, transfection with the suppressor alone was sufficient to reduce the growth rate of BCP-1 cells. Treatment with TGF-β further reduced the cell growth rates. PI and annexin V staining revealed that the suppressor increased the number of apoptotic cells in BCP-1 cells (Fig. 11D and E). Examination of PARP cleavage confirmed these results, as indicated by an increased intensity of the cleavage band in cells treated with the miR-K10a suppressor (Fig. 11F).

DISCUSSION

Viruses often manipulate host environments to facilitate their infections. Since TGF-β signaling plays an important role in many essential cellular processes, including proliferation, differentiation, migration, survival, and apoptosis (43, 50), it is not surprising that a number of viruses dysregulate this important cellular pathway during infection (10, 21, 22, 34, 35, 47). In normal cells, such as B-cells and endothelial cells, the two primary cell types that are infected by KSHV, the common result of TGF-β signaling is cell growth inhibition (43, 50). In contrast, dysregulation of TGF-β signaling often leads to uncontrolled cellular proliferation, as observed in many types of cancer (33). In this study, we have found that KSHV miRs derived from pre-miR-K10 dysregulate the TGF-β pathway by targeting TβRII.

Results of recent studies revealed multiple miR-K10 variants and the presence of a miR-142-3p variant that shares the same seed sequence in KSHV-infected cells (16, 49). We attempted to develop specific RT-qPCR assays for the detection of these viral and cellular miR variants. Unfortunately, all the viral assays detected all the viral variants, while all the cellular assays detected all the cellular variants. Nevertheless, we were able to examine the expression of overall abundance of these miR variants in our experimental systems. It is interesting that miR-142-3p variants are expressed only in B-cells (PEL and Bjab) but not endothelial cells and 293T cells irrespective of the presence of KSHV infection. Furthermore, while the miR-142-3p variants are expressed in Bjab cells, they neither shut down the expression of TβRII, which is robustly expressed in these cells (Fig. 5E and 6C), nor efficiently block TGF-β signaling (Fig. 3D and 4B), indicating that inhibition of the TGF-β pathway by the miR-142-3p variants, if there is any, is inefficient. Results from previous studies on the responsiveness of Bjab cells to TGF-β are controversial (9, 20). Our results have clearly shown that Bjab cells are responsive to TGF-β treatment.

We have shown that miR-K10 variants alone are sufficient to protect cells from TGF-β-induced cell growth arrest and apoptosis. Transfection of a miR suppressor that inhibits all the miR-K10 and miR-142-3p variants into KSHV-infected BCP-1 cells increased TβRII expression, enhanced TGF-β signaling, sensitized cells to apoptosis, and decreased cell growth (Fig. 11). These results indicate that the inhibitory effects of other KSHV proteins and miRs on the TGF-β pathway, if any, are ineffective. On the other hand, miR-K10 and miR-142-3p variants likely play a major role in KSHV inhibition of the TGF-β pathway and thus might protect latent KSHV-infected cells from apoptosis. Nevertheless, because the suppressor blocks the functions of all miR-K10 and miR-142-3p variants, the relative contributions of these variants to the inhibition of TGF-β signaling in these KSHV-infected latent cells cannot be evaluated.

A previous study has shown that KSHV miRs indirectly regulate the TGF-β pathway by targeting THBS1 (42). MiR-K11 functions as an ortholog of the cellular oncogenic miR hsa-miR-155 (18, 46). Because hsa-miR-155 blocks TGF-β signaling pathway by targeting Smad5 or Smad2 (30, 40), it is likely that miR-K11 might also target the TGF-β pathway. Indeed, during preparation of the manuscript, an independent study reported miR-K11 inhibition of the TGF-β pathway (29). Several KSHV-encoded proteins have been shown to regulate the TGF-β pathway, including the viral latent protein LANA, which epigenetically silences TβRII, and two viral lytic proteins, vIRF1 and K-bZIP, that target the Smad and CREB-binding proteins, respectively (13, 44, 48). Thus, KSHV has evolved multiple mechanisms to disrupt the TGF-β pathway during both latent and lytic infection. Whether these viral products exert synergistic effects or target specific stages of the viral life cycle in KSHV-infected cells remains to be determined.

Latency is a hallmark of herpesvirus infection. Latent infection serves to evade the host immune responses in part because of the minimal expression of viral products during this phase of the viral life cycle. Strategies that promote the growth and survival of latent cells, as well as blocking the innate or adaptive host immune responses, favor herpesviral latent infection. The fact that all KSHV miRs are located at the latent locus of the viral genome and expressed during viral latency suggests that they function to promote viral latency (7, 8, 19, 37, 41). Viral miRs have the advantages of evading host immune detection while exerting their functions. Indeed, we and another group have recently reported that deletion of the 10-pre-miR cluster resulted in an increase in lytic reactivation of KSHV (23, 32). Both miR-K9-5p and miR-K7-5p directly target the viral lytic transactivator RTA (ORF50) to stabilize viral latency (5, 26). On the other hand, both KSHV miR-K5 and -K9 inhibit apoptosis by targeting the BCLAF1 protein (53). MiR-K11 attenuates interferon signaling by targeting IKKε, which contributes to maintenance of KSHV latency (25). MiR-K7 represses the expression of the natural killer cell ligand MICB (36). MiR-K1 directly targets IκBα and the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21 (17, 23). Results of these studies together with our finding of dysregulation of the TGF-β pathway indicate that KSHV miRs manipulate several cellular pathways to facilitate viral latency by evading immune responses, inhibiting viral lytic replication, and promoting the growth and survival of KSHV-infected cells.

Dysregulation of the TGF-β pathway is a hallmark of many types of cancer. Cancer cells are resistant to TGF-β-mediated inhibition of proliferation, albeit TGF-β is often overexpressed in human cancers (6, 24, 33). Extensive studies have shown that TGF-β is required for the suppression of antitumor immune responses, optimal interactions of cancer cells with the microenvironment, cancer-induced angiogenesis, and the invasion and metastasis of cancer cells (6, 33). As a consequence, dysregulation of the TGF-β pathway is one of the key steps in the development of a variety of human cancers (33). Indeed, TGF-β signaling is dysregulated in all three KSHV-induced malignancies, including KS, PEL, and MCD (13). Both KS tumors and PEL have high expression levels of TGF-β (11, 13). Our finding that miRs derived from KSHV miR-pre-K10 suppress the TGF-β pathway suggests that they might contribute to the development of KSHV-induced malignancies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Bryan Cullen at Duke University Medical Center for the Renilla luciferase constructs of the miRs and members of S.-J. Gao's laboratory for technical assistance.

This work was supported by grants from NIH (CA096512, CA124332, and CA119889) to S.-J. Gao.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 22 August 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Abend JR, Uldrick T, Ziegelbauer JM. 2010. Regulation of tumor necrosis factor-like weak inducer of apoptosis receptor protein (TWEAKR) expression by Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus microRNA prevents TWEAK-induced apoptosis and inflammatory cytokine expression. J. Virol. 84:12139–12151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ambros V. 2004. The functions of animal microRNAs. Nature 431:350–355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bartel DP. 2004. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell 116:281–297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bartel DP. 2009. MicroRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell 136:215–233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bellare P, Ganem D. 2009. Regulation of KSHV lytic switch protein expression by a virus-encoded microRNA: an evolutionary adaptation that fine-tunes lytic reactivation. Cell Host Microbe 6:570–575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bierie B, Moses HL. 2006. Tumour microenvironment: TGFbeta: the molecular Jekyll and Hyde of cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 6:506–520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cai X, Cullen BR. 2006. Transcriptional origin of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus microRNAs. J. Virol. 80:2234–2242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cai X, et al. 2005. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus expresses an array of viral microRNAs in latently infected cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:5570–5575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chen G, Ghosh P, Longo DL. 2011. Distinctive mechanism for sustained TGF-beta signaling and growth inhibition: MEK1 activation-dependent stabilization of type II TGF-beta receptors. Mol. Cancer Res. 9:78–89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cheng PL, Chang MH, Chao CH, Lee YH. 2004. Hepatitis C viral proteins interact with Smad3 and differentially regulate TGF-beta/Smad3-mediated transcriptional activation. Oncogene 23:7821–7838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ciernik IF, et al. 1995. Expression of transforming growth factor beta and transforming growth factor beta receptors on AIDS-associated Kaposi's sarcoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 1:1119–1124 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cullen BR. 2009. Viral and cellular messenger RNA targets of viral microRNAs. Nature 457:421–425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Di Bartolo DL, et al. 2008. KSHV LANA inhibits TGF-beta signaling through epigenetic silencing of the TGF-beta type II receptor. Blood 111:4731–4740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gao SJ, et al. 1996. Seroconversion to antibodies against Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-related latent nuclear antigens before the development of Kaposi's sarcoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 335:233–241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gottwein E, Cai X, Cullen BR. 2006. A novel assay for viral microRNA function identifies a single nucleotide polymorphism that affects Drosha processing. J. Virol. 80:5321–5326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gottwein E, et al. 2011. Viral microRNA targetome of KSHV-infected primary effusion lymphoma cell lines. Cell Host Microbe 10:515–526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gottwein E, Cullen BR. 2010. A human herpesvirus microRNA inhibits p21 expression and attenuates p21-mediated cell cycle arrest. J. Virol. 84:5229–5237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gottwein E, et al. 2007. A viral microRNA functions as an orthologue of cellular miR-155. Nature 450:1096–1099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Grundhoff A, Sullivan CS, Ganem D. 2006. A combined computational and microarray-based approach identifies novel microRNAs encoded by human gamma-herpesviruses. RNA 12:733–750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Inman GJ, Allday MJ. 2000. Resistance to TGF-beta1 correlates with a reduction of TGF-beta type II receptor expression in Burkitt's lymphoma and Epstein-Barr virus-transformed B lymphoblastoid cell lines. J. Gen. Virol. 81:1567–1578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lee DK, Kim BC, Brady JN, Jeang KT, Kim SJ. 2002. Human T-cell lymphotropic virus type 1 tax inhibits transforming growth factor-beta signaling by blocking the association of Smad proteins with Smad-binding element. J. Biol. Chem. 277:33766–33775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lee DK, et al. 2002. The human papilloma virus E7 oncoprotein inhibits transforming growth factor-beta signaling by blocking binding of the Smad complex to its target sequence. J. Biol. Chem. 277:38557–38564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lei X, et al. 2010. Regulation of NF-kappaB inhibitor IκBα and viral replication by a KSHV microRNA. Nat. Cell Biol. 12:193–199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Levy L, Hill CS. 2006. Alterations in components of the TGF-beta superfamily signaling pathways in human cancer. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 17:41–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Liang D, et al. 2011. A human herpesvirus miRNA attenuates interferon signaling and contributes to maintenance of viral latency by targeting IKKepsilon. Cell Res. 21:793–806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lin X, et al. 2011. miR-K12-7-5p encoded by Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus stabilizes the latent state by targeting viral ORF50/RTA. PLoS One 6:e16224 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0016224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lin YT, et al. 2010. Small RNA profiling reveals antisense transcription throughout the KSHV genome and novel small RNAs. RNA 16:1540–1558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Liu H, Yue D, Chen Y, Gao SJ, Huang Y. 2010. Improving performance of mammalian microRNA target prediction. BMC Bioinformatics 11:476 doi:10.1186/1471-2105-11-476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Liu Y, et al. 2012. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-encoded microRNA miR-K12-11 attenuates transforming growth factor beta signaling through suppression of SMAD5. J. Virol. 86:1372–1381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Louafi F, Martinez-Nunez RT, Sanchez-Elsner T. 2010. MicroRNA-155 targets SMAD2 and modulates the response of macrophages to transforming growth factor-β. J. Biol. Chem. 285:41328–41336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lu CC, et al. 2010. MicroRNAs encoded by Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus regulate viral life cycle. EMBO Rep. 11:784–790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lu F, Stedman W, Yousef M, Renne R, Lieberman PM. 2010. Epigenetic regulation of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus latency by virus-encoded microRNAs that target Rta and the cellular Rbl2-DNMT pathway. J. Virol. 84:2697–2706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Massague J. 2008. TGFβ in Cancer. Cell 134:215–230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Mori N, et al. 2001. Human T-cell leukemia virus type I oncoprotein Tax represses Smad-dependent transforming growth factor beta signaling through interaction with CREB-binding protein/p300. Blood 97:2137–2144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Mori N, Morishita M, Tsukazaki T, Yamamoto N. 2003. Repression of Smad-dependent transforming growth factor-beta signaling by Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 1 through nuclear factor-kappaB. Int. J. Cancer 105:661–668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Nachmani D, Stern-Ginossar N, Sarid R, Mandelboim O. 2009. Diverse herpesvirus microRNAs target the stress-induced immune ligand MICB to escape recognition by natural killer cells. Cell Host Microbe 5:376–385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Pfeffer S, et al. 2005. Identification of microRNAs of the herpesvirus family. Nat. Methods 2:269–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Qin Z, et al. 2010. Upregulation of xCT by KSHV-encoded microRNAs facilitates KSHV dissemination and persistence in an environment of oxidative stress. PLoS Pathog. 6:e1000742 doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1000742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Qin Z, Kearney P, Plaisance K, Parsons CH. 2010. Pivotal advance: Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV)-encoded microRNA specifically induce IL-6 and IL-10 secretion by macrophages and monocytes. J. Leukoc. Biol. 87:25–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Rai D, Kim SW, McKeller MR, Dahia PL, Aguiar RC. 2010. Targeting of SMAD5 links microRNA-155 to the TGF-beta pathway and lymphomagenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107:3111–3116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Samols MA, Hu J, Skalsky RL, Renne R. 2005. Cloning and identification of a microRNA cluster within the latency-associated region of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. J. Virol. 79:9301–9305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Samols MA, et al. 2007. Identification of cellular genes targeted by KSHV-encoded microRNAs. PLoS Pathog. 3:e65 doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.0030065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Schmierer B, Hill CS. 2007. TGFβ-SMAD signal transduction: molecular specificity and functional flexibility. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8:970–982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Seo T, Park J, Choe J. 2005. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus viral IFN regulatory factor 1 inhibits transforming growth factor-beta signaling. Cancer Res. 65:1738–1747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Shankarappa B, Balachandran R, Gupta P, Ehrlich GD. 1992. Introduction of multiple restriction enzyme sites by in vitro mutagenesis using the polymerase chain reaction. PCR Methods Appl. 1:277–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Skalsky RL, et al. 2007. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus encodes an ortholog of miR-155. J. Virol. 81:12836–12845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Tarakanova VL, Wold WS. 2003. Transforming growth factor beta1 receptor II is downregulated by E1A in adenovirus-infected cells. J. Virol. 77:9324–9336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Tomita M, Choe J, Tsukazaki T, Mori N. 2004. The Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus K-bZIP protein represses transforming growth factor beta signaling through interaction with CREB-binding protein. Oncogene 23:8272–8281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Umbach JL, Cullen BR. 2010. In-depth analysis of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus microRNA expression provides insights into the mammalian microRNA-processing machinery. J. Virol. 84:695–703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Wu MY, Hill CS. 2009. Tgf-beta superfamily signaling in embryonic development and homeostasis. Dev. Cell 16:329–343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Ye F, Lei X, Gao SJ. 2011. Mechanisms of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus latency and reactivation. Adv. Virol. 2011:193860 doi:10.1155/2011/193860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Zawel L, et al. 1998. Human Smad3 and Smad4 are sequence-specific transcription activators. Mol. Cell 1:611–617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Ziegelbauer JM, Sullivan CS, Ganem D. 2009. Tandem array-based expression screens identify host mRNA targets of virus-encoded microRNAs. Nat. Genet. 41:130–134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]