Abstract

Some unidentified RNA molecules, together with the nucleoid protein HU, were suggested to be involved in the nucleoid structure of Escherichia coli. HU is a conserved protein known for its role in binding to DNA and maintaining negative supercoils in the latter. HU also binds to a few RNAs, but the full spectrum of its binding targets in the cell is not known. To understand any interaction of HU with RNA in the nucleoid structure, we immunoprecipitated potential HU-RNA complexes from cells and examined bound RNAs by hybridization to whole-genome tiling arrays. We identified associations between HU and 10 new intragenic and intergenic noncoding RNAs (ncRNAs), 2 of which are homologous to the annotated bacterial interspersed mosaic elements (BIMEs) and boxC DNA repeat elements. We confirmed direct binding of HU to BIME RNA in vitro. We also studied the nucleoid shape of HU and two of the ncRNA mutants (nc1 and nc5) by transmission electron microscopy and showed that both HU and the two ncRNAs play a role in nucleoid morphology. We propose that at least two of the ncRNA species complex with HU and help the formation or maintenance of the architecture of the E. coli chromosome. We also observed binding of HU with rRNA and tRNA segments, a few small RNAs, and a distinct small set of mRNAs, although the significance, if any, of these associations is not known.

INTRODUCTION

HU, a well-conserved and abundant nucleoid protein in Escherichia coli, is composed of two 9-kDa homologous subunits, α and β (9, 18, 40, 41, 48, 49). HU showed nonspecific interactions with DNA with micromolar affinity (8, 52) and specific interactions with nicked, cruciform, and kinked DNA with nanomolar affinities (5, 29, 30, 45, 52, 55, 60). HU also showed interactions with tRNAs and dsrA and rpoS mRNA (4, 5).

It was suggested that RNA molecules, together with HU and other nucleoid proteins, are involved in maintaining E. coli chromosome structure, although the identities of the RNAs have not been established (44). These and subsequent studies showed that 100- to 300-nucleotide (nt)-long RNA chains are part of the nucleoid (43, 44). Treatment of the nucleoid with RNase caused a decondensation with a dramatic decrease in the sedimentation constant of the isolated chromosome from 1600S to approximately 400S to 500S (44, 65). In this work, we followed the idea that some HU-RNA complexes are of importance in nucleoid structure with the aim of identifying the RNAs that bind to HU and then understanding the role of such complexes in the nucleoid.

We took the ribonomic approach, also referred to as RNA immunoprecipitation (IP) followed by microarray (Chip) profiling (RIP-Chip) assay, which involves immunoprecipitation of ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes with antibodies against specific proteins, extraction of RNA, and hybridization to microarrays (58). The assay helped with global identification of putative endogenous RNA targets of specific proteins in several systems (11, 12, 24, 25, 32, 33, 50, 51, 53, 57, 66).

We report associations of HU with several RNAs and their identification: a set of noncoding RNAs (ncRNAs) not previously reported, regions of rRNA and tRNA, a few small RNAs (sRNAs), and a set of mRNAs. We further investigated some of the noncoding RNAs by confirming their transcription by Northern blotting and by showing their direct binding to HU by electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA). By transmission electron microscopy (TEM) analysis, we showed that deletion of two ncRNAs (nc1 and nc5) leads to nucleoid decondensation. We propose that at least two of the ncRNAs play a role in the E. coli chromosome architecture.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

All E. coli strains used in this study are derivatives of E. coli K-12 MG1655. In order to construct eight myc tags fused to HUβ, two complementary primer sets, each with four myc tags, flanked by HindIII-EcoRI and EcoRI-BamHI, were used (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Complementary primers were annealed, ligated to each other, and cloned into the HindIII-BamHI cloning vector containing the hupB open reading frame. Finally, hupB with the eight myc tags was integrated into the chromosome in place of hupB (10). The protein expression profiles, as monitored by Western blotting, of the strains with eight myc tags fused to HUβ were identical to the profile of the wild type (data not shown). We tested the tagged HUβ functionality by testing two cellular functions as described in Results. For TEM analysis, we constructed deletions of nc1 or nc5 by the recombineering method (10), introducing an ∼1-kb tetracycline resistance cassette which replaced the intergenic region between yagP and intF or yjdN and yjdM, respectively. HU deletions were constructed by P1 transduction of hupA::Kan and hupB::Cm alleles into the wild-type, Δnc1, or Δnc5 background.

RIP-Chip assay.

The RIP-Chip assay was adapted from that of Zhang et al. (66) and Hu et al. (22).

(i) Cell growth.

Cells of the strain with eight myc tags fused to HUβ were grown in M63 medium supplemented with 0.2% glucose, 0.1% Casamino Acids, and 0.002% vitamin B1 at 37°C to exponential phase (optical density at 600 nm [OD600] = 0.4).

(ii) Cell extracts.

Overnight cultures in M63 medium with 0.2% glucose, 0.1% Casamino Acids, and 0.0001% thiamine were diluted 1:100 into 50 ml and grown to an OD600 of 0.8. Samples were centrifuged and resuspended in 400 ml lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM dithiothreitol). After addition of 400 μl (about 0.6 g) glass beads (catalog number G1277; Sigma) and 2 μl RNasin, 10 cycles of alternate 30 s vortexing and 5 s incubation on ice were performed. An additional 800 μl lysis buffer was added, and after a brief vortexing for 10 s, the samples were spun down at 4°C for 10 min. One-milliliter supernatant samples were transferred into new Eppendorf tubes.

(iii) Preparation of Ab-PAS beads.

Twenty-four milligrams of protein A Sepharose CL-4B (PAS; catalog number 17-0780-01; Amersham Biosciences) was swelled in 200 μl Net2 buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 0.05% Triton X-100). Twenty microliters of anti-myc antibody (Ab; M4439; Sigma) was added, and the mixture was rotated at 4°C overnight. Ab-PAS was washed 5 times with Net2 buffer.

(iv) Immunoprecipitation.

Immunoprecipitation was carried out according to the modified protocol of Wassarman and Storz (64). Two hundred microliters of cell extract, 200 μl Net2 buffer, and 1 μl RNasin were added to the Ab-PAS pellet, and the mixture was rotated at 4°C for 2 h. Samples were washed 5 times with 1.5 ml Net2 buffer.

(v) Isolation of RNA.

RNA fragments were purified using a Qiagen RNeasy purification kit according to the manufacturer's protocol. The RNA pellet was dissolved in diethyl pyrocarbonate H2O. A single IP usually yields about 10 μg RNA (for 50 ml). Since we omitted any cross-linking, there is a chance that RNAs are free to dissociate and bind HU in the cell lysate and RNAs that may normally be sequestered in the cell and unavailable for binding to HU are potentially released in the lysis process and then bind to HU nonspecifically.

(vi) RNA hybridization and detection.

Tiling array chips on which the complete Escherichia coli MG1655 genome sequence is represented were used (E. coli_Tab520346F; Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA). The chips had 1,159,908 probes in 1.4 cm by 1.4 cm and a 25-mer probe every 8 bp in both strands of the entire E. coli genome. The probes overlapped by 4 bp with the probes of the opposite strand. Each 25-mer DNA probe in the tiling array chip is 8 bp apart from the next probe and designed to cover the whole E. coli genome. The intergenic regions were originally defined by Blattner et al. (6). The RNA samples were hybridized directly to the oligonucleotide arrays with no prior labeling or cDNA synthesis. The RNA samples were added to the hybridization solution (1× MES [100 mM MES {morpholineethanesulfonic acid}, 1 M NaCl, 20 mM EDTA, 0.01% Tween 20, pH 6.6], 0.1 mg ml−1 herring sperm DNA, 0.5 mg ml−1 bovine serum albumin [BSA], and 50 pM control biotinylated oligonucleotide B2 [GeneChip Expression Analysis technical manual, Affymetrix 701021 rev. 5]), and the mixture was heated to 99°C for 5 min and then incubated at 45°C for an additional 5 min before being placed in the microarray cartridge. Hybridization was carried out at 45°C for 16 h on a rotary mixer at 60 rpm. Following hybridization, the sample solution was removed and the array was washed as recommended in the technical manual (Affymetrix). Hybridization was assayed using antibodies specific to the RNA-DNA hybrid and a Digene HC ExpressArray kit (Digene, Gaithersburg, MD) as described by Hu et al. (22). The antibody was a gift of Stephen Leppla (National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health). Twenty-five microliters of an RNA-DNA polyclonal antibody (1.3 mg ml−1) was resuspended in 475 μl of matrix solution and loaded on the array, and the array was incubated at 25°C for 20 min (22). After removal of the first antibody stain and 10 wash cycles, the array was incubated with the second antibody stain, containing 0.036 mg ml−1 biotin rabbit anti-goat IgG and 0.4 mg ml−1 rabbit IgG in 1× MES. The RNA-DNA hybrids were fluorescently labeled by incubating with 10 mg ml−1 streptavidin-phycoerythrin (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) and 2 mg ml−1 BSA in 1× MES. Hybridized, washed, and stained tiling arrays were scanned using a GeneChip Scanner 3000 (Affymetrix). Signals standardized for each individual probe in the array were generated using the model-based analysis of tiling arrays (MAT) analysis software (27) at the University of Wisconsin—Madison for Escherichia coli K-12 MG1655, version m56 (16).

RNA preparation and Northern blot experiments.

Overnight cultures were grown at 37°C in M63 medium supplemented with 0.2% glucose, 0.1% Casamino Acids, and 0.002% vitamin B1. Strains were diluted 1:100 and grown to mid-exponential phase at 37°C in M63 medium supplemented with 0.2% glucose, 0.1% Casamino Acids, and 0.002% vitamin B1. RNA was extracted using the hot phenol method (1). RNAs were detected by Northern blotting, as follows. Five micrograms of RNA from each sample was separated on a 10% Tris-borate-EDTA (TBE)–urea polyacrylamide gel (EC6875; Invitrogen) that was prerun for 30 min at 70 V and subsequently electrophoresed at 60 V for 2 h in 1× TBE. Serial dilutions of at least one sample were included on each gel. RNA was transferred onto a positively charged nylon Zeta-probe membrane (Bio-Rad) at 200 mA for 1 h in 0.5× TBE. After UV cross-linking, membranes were incubated with Ultrahyb solution (Ambion) at 42°C for 30 min and then hybridized to the 5′-biotinylated probe (100 ng ml−1 in Ultrahyb) for approximately 15 to 20 h at 42°C. The sequences of 5′-biotinylated DNA probes were CGAAGGTCGTAGGTTCGACTCCTATTATCGGCACC for nc1 and GATAAGACGCGCAAGCGTCGCATCAGGCAGTCGGCAC for nc5. The blots were washed, and labeled RNA was detected using a BrightStar BioDetect kit (Ambion), as recommended by the manufacturer.

DNA templates and RNA synthesis.

The series of complementary single-stranded DNA oligonucleotides containing the T7 promoter sequence (5′-TAATACGACTCACTATAGG-3′) followed by a sequence which corresponds to nc5 was used (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). The doubles-stranded DNAs were obtained by annealing the appropriate complementary oligonucleotides. Annealing reactions were carried out by incubating equal amounts of two complementary oligonucleotides (500 nM) for 30 s at 95°C in 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 200 mM NaCl and then allowing them to cool slowly. Transcription reactions were carried out as described previously (38). Double-stranded template DNA (2 nM) was preincubated at 37°C for 5 min in transcription buffer (50 μl) containing 20 mM Tris acetate (pH 7.8), 10 mM magnesium acetate, 200 mM potassium glutamate, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 0.8 U μl−1 rRNasin (Promega), and 100 units of T7 RNA polymerase (200 units μl−1; USB). To initiate the reactions, nucleotides were added to final concentrations of 1 mM ATP, 0.1 mM GTP, 0.1 mM CTP, 0.01 mM UTP, and 5 μCi [α-32P]UTP (specific activity, 3,000 μCi mmol−1, 10 μCi μl−1; MP Biomedicals). The reaction mixtures were incubated at 37°C for an additional 10 min, and then the reactions were terminated by the addition of 50 μl of loading dye (90% formamide, 10 mM EDTA, 0.1% xylene cyanol, 0.1% bromophenol blue). After incubation at 90°C for 2 to 3 min, samples were chilled on ice. Sample aliquots of 10 μl were loaded onto an 8% sequencing gel and electrophoresed at 60 W.

Gel mobility shift assay.

Various amounts of HU protein were incubated with 5′ 32P-labeled RNAs for 15 min in high-salt buffer (20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 200 mm NaCl, 10% glycerol) at room temperature (5). Electrophoresis was carried out on an 8% polyacrylamide gel (29:1) buffered with 0.5× Tris-borate buffer, pH 8.3. Gels were analyzed and quantified using a PhosphorImager with Molecular Dynamics software.

Transmission electron microscopy.

Equal volumes of Escherichia coli cell culture and 2× fixative (8% formaldehyde and 4% glutaraldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline, pH 7.4) were centrifuged at 200 × g for 15 min and processed for thin-section electron microscopy analysis. The pellet was rinsed thoroughly in sodium cacodylate buffer (0.1 M, pH 7.4) and postfixed in 1% osmium tetroxide in the same buffer for 1 h at room temperature. The pellet was dehydrated in a series of graded ethanol (e.g., 35, 50, 75, 95, and 100%) and 100% propylene oxide and infiltrated in an equal volume of 100% propylene oxide and epoxy resin overnight. The pellet was embedded in the pure epoxy resin and was cured at 55°C for 48 h. The cured block was thin sectioned in ≈50- to 60-nm sections with an ultramicrotome. The thin sections were mounted on a naked copper grid and stained in uranyl acetate and lead citrate solution to enhance the contrast. The grids were examined, and digital images were taken with an H7000 electron microscope (Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan) operated at 75 kV. We looked at 50 cells of each strain. Figures 5 to 7 show two pictures of each strain. In each case, the two are representatives of 90% of the images collected for each strain.

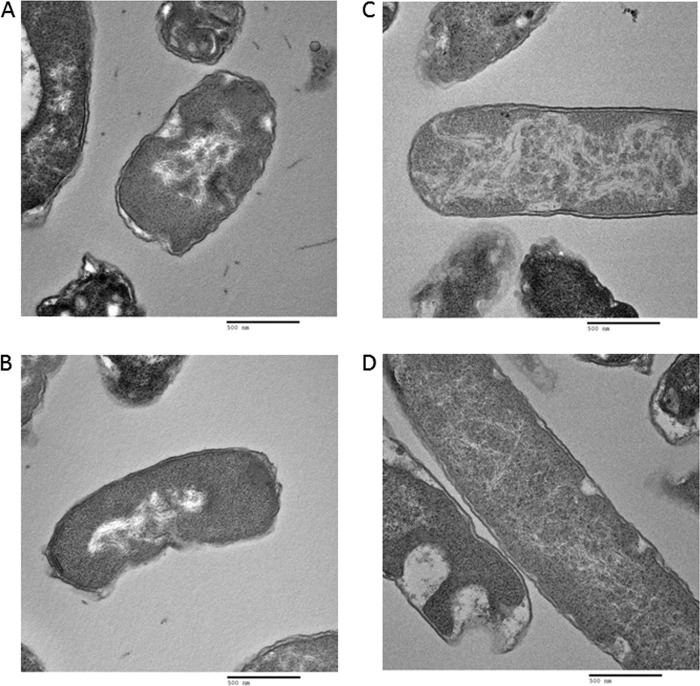

Fig 5.

TEM analysis of nucleoid morphology of wild-type E. coli MG1655 cells (A, B) and E. coli MG1655 cells with deletion of hupA and hupB genes (C, D).

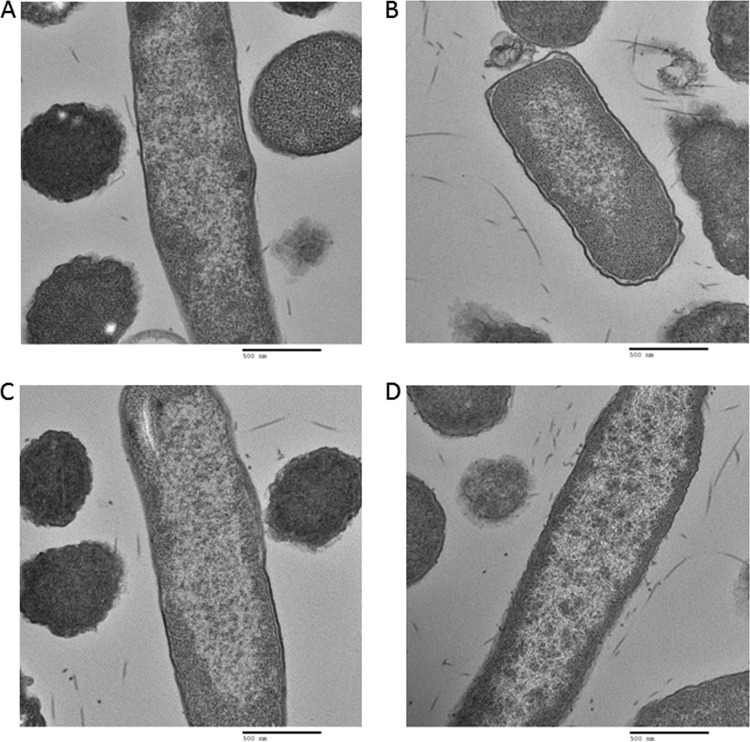

Fig 7.

Effects of nc5 on nucleoid morphology. TEM analysis of cells with deletion of nc5 (A, B) and deletion of nc5 and hupA and hupB genes (C, D).

Microarray data accession number.

The RNA targets that coimmunoprecipitated with HU and that were identified by tiling arrays have been submitted to the GEO databank (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo) under accession number GSE28565.

RESULTS

RIP-Chip identification of RNAs bound to HU.

Exponentially growing Escherichia coli cells were shown to contain a mixture of homodimeric HUα2 and heterodimeric HUαβ, but homodimeric HUβ2 was not detected (9). To identify the RNA targets of the HUαβ heterodimer in exponentially growing cells, we constructed an E. coli strain in which the chromosomal hupB was replaced by the hupB gene with eight successive myc tags fused to its N terminus. We confirmed that the tagged HUβ-myc protein was functional by two assays: (i) mini-P1 plasmids cannot be maintained in the host cell unless either HUα or HUβ is present (42). We showed that, as expected, mini-P1 plasmid cannot transform the E. coli strain that is genotypically ΔhupA ΔhupB, whereas the same plasmid can be stably transformed in the ΔhupA hupB-myc host, suggesting that the HUβ-myc fusion protein is active (Table 1). (ii) Bacteriophage Mu does not form plaques on a ΔhupA ΔhupB E. coli lawn on agar plates (31). We found that Mu forms plaques on ΔhupA hupB+-myc at an almost normal efficiency compared to the wild-type host, suggesting that the fusion protein is biologically active (Table 1).

Table 1.

Function of HUβ fusion protein measured by efficiency of mini-P1 plasmid replication and bacteriophage Mu growtha

| Host strain | CFU of mini-P1/μg DNA | PFU of phage Mu/ml |

|---|---|---|

| Wild type | 1.0 × 108 | 3.7 × 108 |

| 8 myc-tagged hupB | 1.0 × 107 | 2.5 × 108 |

| ΔhupA | 4.0 × 107 | 2.2 × 108 |

| ΔhupA 8 myc-tagged hupB | 2 × 105 | 4.4 × 107 |

| ΔhupA ΔhupB | >1 × 103 | >1 × 102 |

Mini-P1 plasmid maintenance was measured by transforming various competent E. coli cells with plasmid DNA and then counting the number of transformed cells (CFU) per unit of DNA. Efficiency of phage Mu growth was estimated by measuring the number of plaques obtained by plating phage Mu (PFU) on various hosts per given amount of phage particles.

We chose to grow the cultures in minimal medium to allow more genes to be expressed for RIP-Chip assays (56). It was previously reported that a larger number of genes have expression intensities above the background values when E. coli is grown under these conditions compared to when it is grown in rich medium. Although our minimal medium contained Casamino Acids, the gene expression spectrum is still higher than that in LB medium. After immunoprecipitation and RNA isolation, samples were identified by direct hybridization to the E. coli DNA tiling arrays, by using an antibody specific for RNA-DNA hybrids to detect hybridization on the DNA chips (22). As a negative control, we used RNA extracted from the parental strain in which no myc tag was present. Total RNA extracted from cells served as the total signal. We used 0.8 μg of RNA in the immunoprecipitated experiment, 8 μg in the total RNA experiment, and 0.5 μg in the negative-control experiment. Microarray analysis was done using a model-based analysis of tiling arrays (MAT) which models the baseline probe behavior by considering the probe sequence and copy number on each array. It standardizes the probe value through the probe model, eliminating the need for sample normalization. MAT uses an innovative function to score regions for enrichment, which allows robust P-value and false-discovery-rate calculations (27).

The RNA targets which coimmunoprecipitated with HU and were identified by tiling arrays are given in Table 2. We found segments of (i) all tRNAs; (ii) 23S, 16S, and 5S rRNAs; (iii) 11 mRNAs; and (iv) four sRNAs that immunoprecipitated with HUβ-myc. We additionally found 10 RNA molecules transcribed from intergenic and intragenic regions; no RNA was previously reported to be transcribed from these regions. These RNAs were named nc1 to nc10 (where “nc” stands for noncoding).

Table 2.

RNA fragments which coimmunoprecipitated with HU in RIP-Chip assaysa

| RNA species | Name | Physiological role | Genomic coordinates | No. of fragments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| tRNA | Protein synthesis | 89 | ||

| rRNA | Protein synthesis | 22 | ||

| sRNA | ffs (4.5S) | Component of the signal recognition particle (SRP) | 475672–475785 | 1 |

| ssrA (tRNA, mRNA) | trans-Translation | 2753615–2753977 | 1 | |

| ssrS (6S) | RNA polymerase associated; transcription | 3053970–3054220 | 1 | |

| rnpB | RNase P RNA component precursor | 3268614–3268238 | 1 | |

| mRNA | rpsK | 30S ribosomal protein S11 | 3440120–3439731 | 1 |

| fliC | Flagellar filament structural protein (flagellin) | 2001630–2000134 | 1 | |

| agaW | N-Acetylgalactosamine-specific enzyme, IIC component of PTS | 3278723–3279097 | 1 | |

| cspA | Major cold shock protein | 3718072–3718284 | 1 | |

| lpp | Outer membrane murein lipoprotein | 1755445–1755681 | 1 | |

| ompA | Outer membrane protein A | 1018236–1019276 | 1 | |

| mrp | Antiporter inner membrane protein | 2192190–2191081 | 1 | |

| flu (b2000) | CP4-44 prophage antigen 43, phase-variable biofilm | 2069563–2072682 | 1 | |

| ybhN | Conserved inner membrane protein | 821721–820765 | 1 | |

| ybhO | Cardiolipin synthase 2 | 822962–821721 | 1 | |

| yhhS | Predicted transporter | 3609756–3608539 | 1 | |

| Noncoding | nc1 | Homology to thrW | 296361–296528 | 1 |

| nc2 | boxC repetitive element | 497025–497169 | 1 | |

| nc3 | Unknown | 1276081–1276160 | 1 | |

| nc4 | Unknown | 3263241–3263360 | 1 | |

| nc5 | BIME | 4323897–4324000 | 2 | |

| 4324201–4324288 | ||||

| nc6 | Unknown | 4564441–4564552 | 1 | |

| nc7 | boxC repetitive element | 1349125–1349315 | 1 | |

| nc8 | Unknown | 3668941–3669196 | 1 | |

| nc9 | Unknown | 28509–28620 | 1 | |

| nc10 | Unknown | 1202901–1203109 | 1 |

The number of immunoprecipitated fragments and their coordinates on the E. coli genome are also listed. Cases where no physiological role is assigned to a given RNA species are marked as unknown. IIC, N-acetylgalactosamine-specific transporter subunit; PTS, phosphotransferase system.

We observed that HU is associated with rRNA and tRNAs. It is conceivable that HU binding to rRNA, tRNA, and some mRNA is because of their known abundance and therefore is nonspecific. Specific binding can be tested by the use of a HU mutant that does not bind RNA in the IP experiment. However, due to our lack of knowledge about the RNA binding domain of HU, such mutants are not available. Nevertheless, the abundance scenario is unlikely because many other abundant mRNAs and sRNAs were not present in our IP experiments. However, our findings are in agreement with previous reports estimating that 40% of nucleoid-associated RNAs are segments of rRNA (43), and HU was previously shown to bind tRNA (5). It was reported that many tRNAs of E. coli contain stretches of sequences that are similar to those found in rRNAs (7). These similar sequences contain both loops and stems and are too frequent to be coincidental (7). It is possible that HU might recognize similar sequences and the corresponding structural motifs in both RNA species. Previous studies of structural motifs important for HU binding revealed that HU recognizes a stem-loop structure (5).

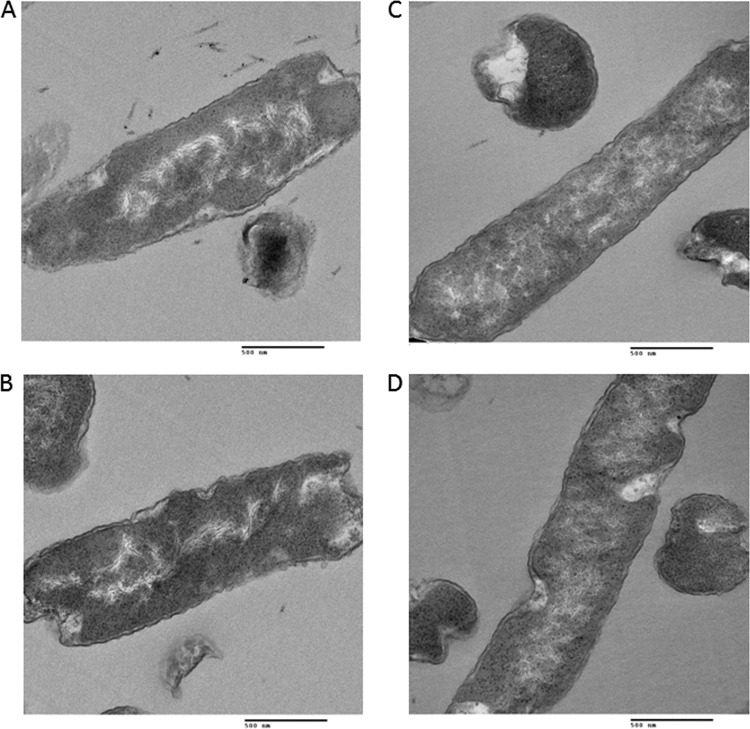

Eleven mRNAs coimmunoprecipitated with HU, and the majority of these code for membrane-associated proteins (Table 2). Two representatives of HU-binding mRNAs, lpp and cspA, are shown in Fig. 1A and Fig. S1A in the supplemental material. It is possible that some of these mRNAs are also present in the nucleoid, since it was shown that nucleoid RNA, in addition to rRNAs, also contains some mRNAs (19). The majority of membrane proteins listed in Table 2 have G+C contents higher than 50%. As previously mentioned, HU binds specifically to the RNA fragment containing the translational initiation region of rpoS mRNA (4). However, we did not detect immunoprecipitation of rpoS mRNA with HU because we did not detect any rpoS mRNA in the total RNA under our conditions.

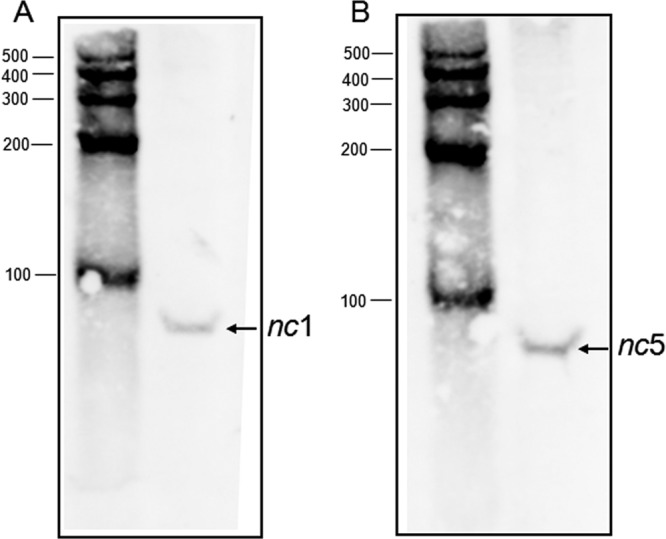

Fig 1.

RIP-Chip assays. Representatives of immunoprecipitated RNAs. (A) lpp; (B) ssrA; (C) nc1; (D) nc5. N, negative control (RNA from a strain with no myc tag); IP, immunoprecipitated RNA; T, total RNA.

sRNAs are divided into two subgroups on the basis of their function: the regulatory sRNAs that act as regulators of gene translation and the housekeeping sRNAs that affect different aspects of cellular metabolism (61, 62). Our results show that HU binds to only 4 of about 100 sRNAs, ssrA (tRNA, mRNA), ssrS (6S sRNA), ffs (4.5S sRNA), and rnpB, which, incidentally, belong to the sRNAs that do not require the chaperone protein Hfq for their function (66) (Table 2). The tiling array patterns of two of the HU-binding sRNAs, ssrA and ssrS, are shown in Fig. 1B and Fig. S1B in the supplemental material. These four housekeeping sRNAs are highly structured (63). In addition, consistent with the observation that HU binds mRNA that is G/C rich, the G+C contents of the housekeeping sRNAs (ssrA, 53%; ssrS, 55%; ffs, 62%; and rnpB, 62%) are also high. This is in contrast to the low G+C content of the regulatory sRNAs (20).

Ten novel noncoding RNAs.

A search for the E. coli sequence homologous to ncRNA fragments using NCBI BLAST (26) showed that a segment of nc1 has homology to the thrW tRNA gene. The fragment corresponding to nc1 is encoded in the intergenic region between yagP and intF (Fig. 1C). This intergenic region contains a pseudogene of thrW inserted at the CP4-6 prophage att site, as annotated in the EcoGene Database of Escherichia coli Sequence and Function (www.ecogene.org). An NCBI BLAST search revealed that nc2, nc5 (discussed later in more detail), and nc7 are homologous to repetitive palindromic extragenic DNA elements. We found that nc2 and nc7 are homologous to boxC DNA elements. On the E. coli K-12 chromosome, there are 22 extragenic regions containing either 1 or 2 boxC DNA elements, totaling 32 boxC DNA elements. boxC DNA elements contain 56-bp-long imperfect palindromes, with a pyrimidine-rich 5′ end (the tail) and a purine-rich 3′ end (2). The functional significance of boxC is not known. It was proposed that boxC DNA elements represent potential sites for protein binding, but no protein has so far been identified to bind these DNA sequences (2). Our data suggest that at least two of the boxC elements are transcribed into RNA to which HU binds. nc2 RNA is encoded by the boxC element in the intergenic region between adk and hemH (see Fig. S1C in the supplemental material), whereas nc7 is encoded in the boxC element that is located between fabI and ycjD (see Fig. S1D in the supplemental material).

nc3, nc4, nc6, nc8, and nc9 are homologous to parts of the noncoding strands of the narX, tdcB, yjiN, treF, and dapB genes, respectively. Two representatives, nc3 and nc8, are shown in Fig. S1E and F in the supplemental material. nc10 is complementary to the intergenic region between ymfL and ymfM, including parts of both the ymfL and ymfM genes.

nc5 refers to the two highly similar immunoprecipitated fragments located in the intergenic region between phnA and phnB (Fig. 1D) that was previously annotated in the EcoGene Database of Escherichia coli Sequence and Function (www.ecogene.org) as the region that contains repetitive extragenic palindromic (REP) elements. MAT analysis of RIP-Chip data (27) suggests that the two immunoprecipitated fragments are 88 nt and 104 nt long, with the first 88 nt of the 104-nt-long RNA being identical in sequence to the individual 88-nt RNA. A BLAST search revealed that the segments of the E. coli genome that are homologous to nc5 represent bacterial interspersed mosaic element (BIME) DNA (14).

We also verified the presence of nc1 and nc5 by Northern blot experiments with two 40-nt-long 5′ biotinylated DNA probes corresponding to nc1 and nc5, respectively. We observed an RNA band of approximately 90 nt in length that hybridized with the probe specific for nc1 (Fig. 2A). In the case of the nc5 probe (Fig. 2B), we also detected a similarly sized RNA that matches the ∼88-nt RNA detected by the tiling array. Since estimating the length of RNA by MAT score is not precise, we believe that the length of nc5 RNA is approximately 90 nt, as detected by Northern blotting.

Fig 2.

Northern blot analysis of nc1 and nc5 RNA. Wild-type strain MG1655 was grown in M63 medium supplemented with 0.2% glucose, 0.1% Casamino Acids, and 0.002% vitamin B1 at 37°C, and samples were removed at an OD600 of 0.5. RNA was extracted by the hot phenol method, fractionated on a 10% TBE-urea gel, and transferred to a nylon membrane. 5′ biotinylated probes were used to detect nc1 (A) and nc5 (B). Ambion RNA Century markers (in nucleotides) were used to determine the size of RNA.

Electrophoretic characterization of HU-RNA complexes.

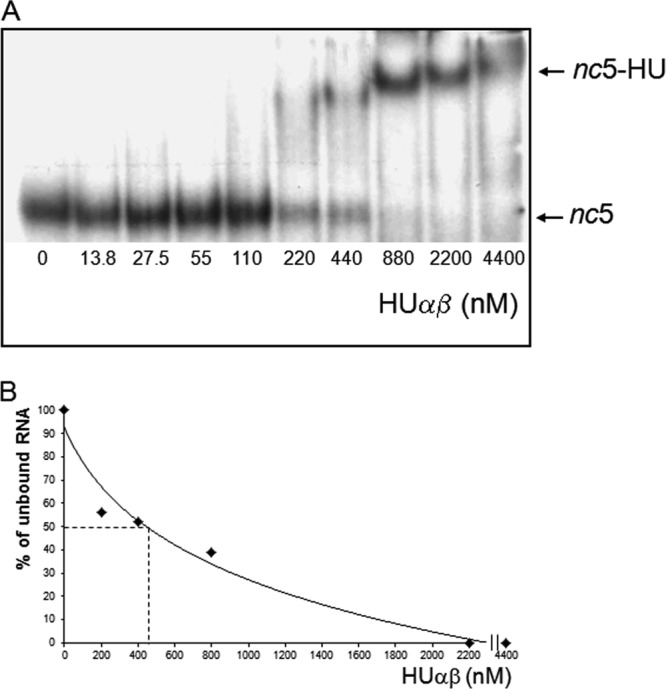

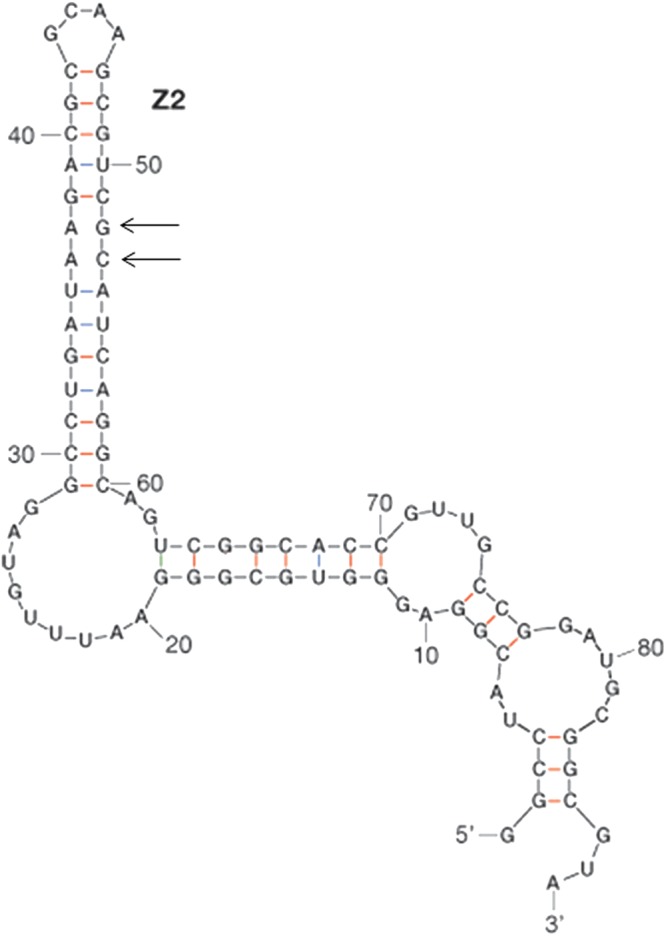

We tested direct binding of HU to BIME nc5 RNA in vitro by electrophoresis mobility shift assay (Fig. 3A). We used an 88-nt-long nc5 RNA at a constant amount (15 fmol) and increasing concentrations of HUαβ heterodimer (13 to 4,400 nM). The results presented in Fig. 3A established that HU formed a complex with the 88-mer RNA. The apparent dissociation constant (Kd) for HU binding was about 450 nM (Fig. 3B). BIMEs comprise combinations of several short sequence motifs called palindromic units (PUs) (21), which are 40-bp-long imperfect palindromes found in the E. coli and Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium genomes. PUs are found either as single occurrences or in clusters, where they alternate in orientation and type (i.e., Y and Z2, according to the classification suggested by Gilson and colleagues [3, 15]). The M-fold analysis (67) of the nc5 RNA shows that it likely forms a BIME-like structure containing a PU Z2 hairpin (Fig. 4). We found that the HU binds to the PU Z2 with a Kd of about 600 nM (see Fig. S2A in the supplemental material). This value is similar to the Kd measured for HU binding to the whole nc5 RNA fragment (Fig. 3B). Several bands of the HU-RNA complexes are observed, each possibly representing a unique number of HU molecules bound to these RNA fragments. Z2 RNA has two mismatches (Fig. 4). HU was previously shown to bind strongly to DNA mismatches and bulges (28). Therefore, the Z2 hairpin present in nc5 might be an important determinant of HU binding.

Fig 3.

HU binding to nc5 RNA. (A) HU protein at the concentrations indicated was mixed with 15 fmol nc5 RNA (88 nt long) synthesized in an in vitro T7 polymerase reaction. The incubation of HU with nc5 RNA was performed under high-salt conditions, and HU-RNA was analyzed by PAGE (see Materials and Methods). (B) Quantification of HU binding to nc5 RNA.

Fig 4.

Predicted RNA fold of nc5 RNA. The secondary structure of nc5 RNA was predicted using the Mfold web server (67). The hairpin which corresponds to the PU Z2 motif found in BIME DNA (3, 15) is indicated. Positions of mismatches in the Z2 hairpin are indicated with arrows.

TEM analysis of nucleoid structure.

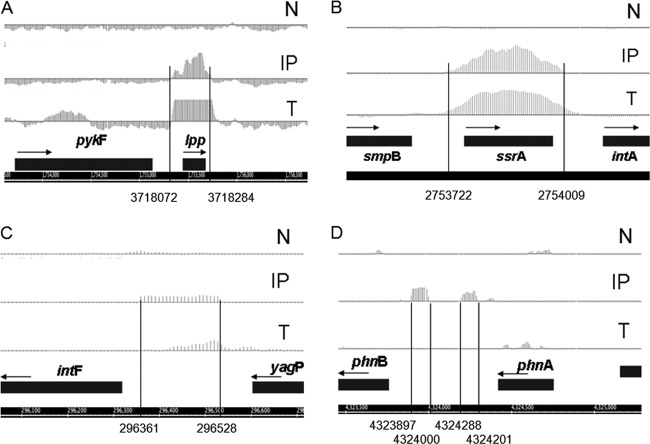

In order to establish whether the ncRNAs identified in this work have an effect on nucleoid structure, we investigated the morphology of nucleoids in cells with deletions of nc1, nc5 RNAs, and HU by TEM (Fig. 5 to 7). In contrast to well-defined nucleoids of wild-type cells (Fig. 5A and B), nucleoids from HU-depleted cells showed a high degree of decondensation (Fig. 5C and D), which is in agreement with previous literature (23). Interestingly, deletions of either nc1 (Fig. 6A and B) or nc5 (Fig. 7A and B) had an impact on nucleoid organization. In both cases, nucleoids were less compacted than those in the wild type. In the strain with deletion of nc5, the nucleoid is decondensed but still retains shape (Fig. 7A and B). Further deletion of HU in this genetic background leads to higher decompaction and loss of shape of the nucleoid (Fig. 7C and D). The strain with deletion of nc1 has a dispersed nucleoid with no defined shape (Fig. 6A and B). Further deletion of HU in the absence of nc1 does not seem to have any additional effect on nucleoid morphology (Fig. 6C and D). Taken together, these results suggest that nc1 and nc5 play a role in defining both the shape and compaction of the nucleoid in an unknown way. We are currently investigating the underlying mechanisms.

Fig 6.

TEM analysis of nucleoid morphology of cells with deletion of nc1 (A, B) and deletion of nc1 hupA and hupB genes (C, D).

DISCUSSION

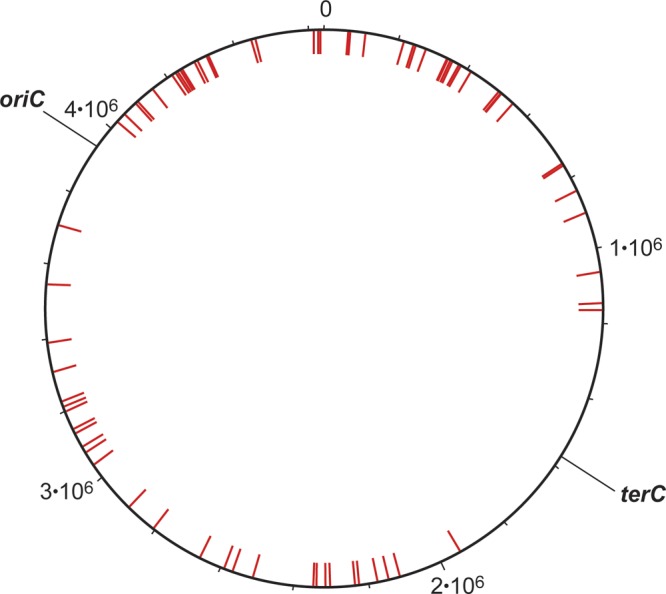

The major purpose of the research described here is to identify the RNA species binding the nucleoid-associated protein HU. It has been suggested that in the nucleoid, segments of DNA (domains) are held together by RNA molecules and stabilized by architectural proteins such as HU (19, 34, 44, 54, 65). In this work, we emphasized two noncoding RNAs, nc1 and nc5, because of their potential role in the E. coli nucleoid structure. nc1 originates from a threonine tRNA gene (E. coli DNA sequence coordinates 296361 to 296528) interrupted by a prophage att site. nc5 is homologous to the DNA repeat elements called BIME. The BIME location on the E. coli chromosome is nonrandom, with most of the positions being in the GC-rich genomic regions (red bars in Fig. 8). A previous report (13) proposed that all copies of BIME identified so far are either between two genes that are cotranscribed as part of a single operon or, alternatively, within the 3′ untranslated region at the end of an operon. In all cases where the extent of transcription is known, the BIME sequence falls within a transcribed region. However, some of the BIME RNA, even if stable, may not interact with HU and thus was not present in our ncRNA collection.

Fig 8.

Location of DNA sequences homologous to nc5 RNA. The circular E. coli chromosome. Red bars, 121 genomic sequences, BIMEs, having more than 50 nt identical to the sequence of nc5 RNA (Fig. 1). The positions of the origin and the terminus of replication (6) are indicated (oriC and terC, respectively).

We have determined the E. coli transcriptome using DNA tiling array in exponentially growing cells of wild-type strain MG1655 (data not shown). We found that of 264 BIMEs identified in E. coli (http://www.pasteur.fr/recherche/unites/pmtg/repet/tableauBIMEcoli.html), only approximately 100 showed significant hybridization signals. Because of extensive sequence similarities between the BIMEs, we were unable to conclude whether all of those BIMEs are transcribed or if only a few of them give transcripts which then hybridize onto the tiling array to other BIME locations because of sequence homology. Based on our results of the RIP-Chip assay, we assigned the BIME(s) at a location between phnA and phnB to be the source of nc5 RNA.

Deletion of both nc5 and nc1 RNAs showed effects on nucleoid structure. The nucleoid of the strain with the nc5 deletion assumed a more open conformation (Fig. 7A and B), and deletion of the HU protein further exacerbated nucleoid decompaction (Fig. 7C and D). Hecht and Pettijohn suggested that certain unknown RNA-DNA interactions in the nucleoid restrain the rotation and extension of the DNA (19). The number of chromosomal domains was variously estimated to be a few hundred, the upper limit of which is compatible with the number of BIME sequences occurring on the chromosome. ncRNAs may interact simultaneously with BIME DNA sequences around the chromosome and HU to form ternary complexes potentially playing the role of anchoring points, which define different chromosomal domains. Interestingly, deletion of nc1 leads to decondensation of the nucleoid regardless of the presence of HU in the cell (Fig. 6A to D). It is possible that both nc1 and nc5 RNAs participate in the nucleoid structure by different mechanisms, which are the subject of our future studies.

A recent publication on RNA-seq analysis in E. coli has confirmed the existence of all ncRNAs reported in this work in various amounts, except that nc4 is expressed at a very low level in exponentially growing cells, whereas nc1 and nc2 are present in large excess relative to the others (46). The same publication confirmed the presence of all the mRNA species that bind to HU in exponentially growing cells, except cspA.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank our colleagues in the laboratory for various help and suggestions and Stephen Leppla for the generous gift of the RNA-DNA mouse monoclonal antibody. We thank Peter Fitzgerald for help with analysis and interpretation of the RIP-Chip data. We also thank R. Raghavan and E. Groisman for the communication of their results to us.

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 31 August 2012

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jb.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1. Aiba H, Adhya S, de Crombrugghe B. 1981. Evidence for two functional gal promoters in intact Escherichia coli cells. J. Biol. Chem. 256:11905–11910 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bachellier S, Clement JM, Hofnung M. 1999. Short palindromic repetitive DNA elements in enterobacteria: a survey. Res. Microbiol. 150:627–639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bachellier S, Saurin W, Perrin D, Hofnung M, Gilson E. 1994. Structural and functional diversity among bacterial interspersed mosaic elements (BIMEs). Mol. Microbiol. 12:61–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Balandina A, Claret L, Hengge-Aronis R, Rouviere-Yaniv J. 2001. The Escherichia coli histone-like protein HU regulates rpoS translation. Mol. Microbiol. 39:1069–1079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Balandina A, Kamashev D, Rouviere-Yaniv J. 2002. The bacterial histone-like protein HU specifically recognizes similar structures in all nucleic acids. DNA, RNA, and their hybrids. J. Biol. Chem. 277:27622–27628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Blattner FR, et al. 1997. The complete genome sequence of Escherichia coli K-12. Science 277:1453–1462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bloch DP, et al. 1983. tRNA rRNA sequence homologies: evidence for a common evolutionary origin? J. Mol. Evol. 19:420–428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bonnefoy E, Rouviere-Yaniv J. 1991. HU and IHF, two homologous histone-like proteins of Escherichia coli, form different protein-DNA complexes with short DNA fragments. EMBO J. 10:687–696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Claret L, Rouviere-Yaniv J. 1997. Variation in HU composition during growth of Escherichia coli: the heterodimer is required for long term survival. J. Mol. Biol. 273:93–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Court DL, et al. 2003. Mini-lambda: a tractable system for chromosome and BAC engineering. Gene 315:63–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Eystathioy T, et al. 2002. A phosphorylated cytoplasmic autoantigen, GW182, associates with a unique population of human mRNAs within novel cytoplasmic speckles. Mol. Biol. Cell 13:1338–1351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gerber AP, Herschlag D, Brown PO. 2004. Extensive association of functionally and cytotopically related mRNAs with Puf family RNA-binding proteins in yeast. PLoS Biol. 2:E79 doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0020079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gilson E, Clement JM, Brutlag D, Hofnung M. 1984. A family of dispersed repetitive extragenic palindromic DNA sequences in E. coli. EMBO J. 3:1417–1421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gilson E, Saurin W, Perrin D, Bachellier S, Hofnung M. 1991. The BIME family of bacterial highly repetitive sequences. Res. Microbiol. 142:217–222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gilson E, Saurin W, Perrin D, Bachellier S, Hofnung M. 1991. Palindromic units are part of a new bacterial interspersed mosaic element (BIME). Nucleic Acids Res. 19:1375–1383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Glasner JD, et al. 2003. ASAP, a systematic annotation package for community analysis of genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 31:147–151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Reference deleted.

- 18. Haselkorn R, Rouviere-Yaniv J. 1976. Cyanobacterial DNA-binding protein related to Escherichia coli HU. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 73:1917–1920 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hecht RM, Pettijohn DE. 1976. Studies of DNA bound RNA molecules isolated from nucleoids of Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 3:767–788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hershberg R, Altuvia S, Margalit H. 2003. A survey of small RNA-encoding genes in Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 31:1813–1820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Higgins CF, Ames GF, Barnes WM, Clement JM, Hofnung M. 1982. A novel intercistronic regulatory element of prokaryotic operons. Nature 298:760–762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hu Z, Zhang A, Storz G, Gottesman S, Leppla SH. 2006. An antibody-based microarray assay for small RNA detection. Nucleic Acids Res. 34:e52 doi:10.1093/nar/gkl142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Huisman O, et al. 1989. Multiple defects in Escherichia coli mutants lacking HU protein. J. Bacteriol. 171:3704–3712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Inada M, Guthrie C. 2004. Identification of Lhp1p-associated RNAs by microarray analysis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae reveals association with coding and noncoding RNAs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101:434–439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Intine RV, Tenenbaum SA, Sakulich AL, Keene JD, Maraia RJ. 2003. Differential phosphorylation and subcellular localization of La RNPs associated with precursor tRNAs and translation-related mRNAs. Mol. Cell 12:1301–1307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Johnson M, et al. 2008. NCBI BLAST: a better web interface. Nucleic Acids Res. 36(web server issue):W5–W9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Johnson WE, et al. 2006. Model-based analysis of tiling-arrays for ChIP-chip. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:12457–12462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kamashev D, Balandina A, Mazur AK, Arimondo PB, Rouviere-Yaniv J. 2008. HU binds and folds single-stranded DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 36:1026–1036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kamashev D, Balandina A, Rouviere-Yaniv J. 1999. The binding motif recognized by HU on both nicked and cruciform DNA. EMBO J. 18:5434–5444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kamashev D, Rouviere-Yaniv J. 2000. The histone-like protein HU binds specifically to DNA recombination and repair intermediates. EMBO J. 19:6527–6535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kano Y, Goshima N, Wada M, Imamoto F. 1989. Participation of hup gene product in replicative transposition of Mu phage in Escherichia coli. Gene 76:353–358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Keene JD, Lager PJ. 2005. Post-transcriptional operons and regulons co-ordinating gene expression. Chromosome Res. 13:327–337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kim Guisbert K, Duncan K, Li H, Guthrie C. 2005. Functional specificity of shuttling hnRNPs revealed by genome-wide analysis of their RNA binding profiles. RNA 11:383–393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kleppe K, Ovrebo S, Lossius I. 1979. The bacterial nucleoid. J. Gen. Microbiol. 112:1–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Reference deleted.

- 36. Reference deleted.

- 37. Reference deleted.

- 38. Lewis DE. 2003. Identification of promoters of Escherichia coli and phage in transcription section plasmid pSA850. Methods Enzymol. 370:618–645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Reference deleted.

- 40. Oberto J, Drlica K, Rouviere-Yaniv J. 1994. Histones, HMG, HU, IHF: meme combat. Biochimie 76:901–908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Oberto J, Rouviere-Yaniv J. 1996. Serratia marcescens contains a heterodimeric HU protein like Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 178:293–297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ogura T, Niki H, Kano Y, Imamoto F, Hiraga S. 1990. Maintenance of plasmids in HU and IHF mutants of Escherichia coli. Mol. Gen. Genet. 220:197–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Pettijohn DE, Clarkson K, Kossman CR, Stonington OG. 1970. Synthesis of ribosomal RNA on a protein-DNA complex isolated from bacteria: a comparison of ribosomal RNA synthesis in vitro and in vivo. J. Mol. Biol. 52:281–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Pettijohn DE, Hecht R. 1974. RNA molecules bound to folded bacterial genome stabilize DNA folds and segregate domains of supercoiling. Cold Spring Harbor Symp. Quant. Biol. 38:31–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Pontiggia A, Negri A, Beltrame M, Bianchi ME. 1993. Protein HU binds specifically to kinked DNA. Mol. Microbiol. 7:343–350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Raghavan R, Groisman EA, Ochman H. 2011. Genome-wide detection of novel regulatory RNAs in E. coli. Genome Res. 21:1487–1497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Reference deleted.

- 48. Rouviere-Yaniv J, Gros F. 1975. Characterization of a novel, low-molecular-weight DNA-binding protein from Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 72:3428–3432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Rouviere-Yaniv J, Kjeldgaard NO. 1979. Native Escherichia coli HU protein is a heterotypic dimer. FEBS Lett. 106:297–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Schmitz-Linneweber C, Williams-Carrier R, Barkan A. 2005. RNA immunoprecipitation and microarray analysis show a chloroplast pentatricopeptide repeat protein to be associated with the 5′ region of mRNAs whose translation it activates. Plant Cell 17:2791–2804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Shepard KA, et al. 2003. Widespread cytoplasmic mRNA transport in yeast: identification of 22 bud-localized transcripts using DNA microarray analysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100:11429–11434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Shindo H, Furubayashi A, Shimizu M, Miyake M, Imamoto F. 1992. Preferential binding of E. coli histone-like protein HU alpha to negatively supercoiled DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 20:1553–1558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Stephens SB, et al. 2005. Stable ribosome binding to the endoplasmic reticulum enables compartment-specific regulation of mRNA translation. Mol. Biol. Cell 16:5819–5831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Stonington OG, Pettijohn DE. 1971. The folded genome of Escherichia coli isolated in a protein-DNA-RNA complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 68:6–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Swinger KK, Rice PA. 2007. Structure-based analysis of HU-DNA binding. J. Mol. Biol. 365:1005–1016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Tao H, Bausch C, Richmond C, Blattner FR, Conway T. 1999. Functional genomics: expression analysis of Escherichia coli growing on minimal and rich media. J. Bacteriol. 181:6425–6440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Tenenbaum SA, Carson CC, Lager PJ, Keene JD. 2000. Identifying mRNA subsets in messenger ribonucleoprotein complexes by using cDNA arrays. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:14085–14090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Tenenbaum SA, Lager PJ, Carson CC, Keene JD. 2002. Ribonomics: identifying mRNA subsets in mRNP complexes using antibodies to RNA-binding proteins and genomic arrays. Methods 26:191–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Reference deleted.

- 60. Vitoc CI, Mukerji I. 2011. HU binding to a DNA four-way junction probed by Forster resonance energy transfer. Biochemistry 50:1432–1441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Wagner EGH, Vogel J. 2003. Noncoding RNAs encoded by bacterial chromosomes, p 243–259 In Barciszewski J, Erdmann V. (ed), Noncoding RNAs. Landes Bioscience, Austin, TX [Google Scholar]

- 62. Wassarman KM, Zhang A, Storz G. 1999. Small RNAs in Escherichia coli. Trends Microbiol. 7:37–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Wassarman KM, Repoila F, Rosenow C, Storz G, Gottesman S. 2001. Identification of novel small RNAs using comparative genomics and microarrays. Genes Dev. 15:1637–1651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Wassarman KM, Storz G. 2000. 6S RNA regulates E. coli RNA polymerase activity. Cell 101:613–623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Worcel A, Burgi E. 1972. On the structure of the folded chromosome of Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Biol. 71:127–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Zhang A, et al. 2003. Global analysis of small RNA and mRNA targets of Hfq. Mol. Microbiol. 50:1111–1124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Zuker M. 2003. Mfold web server for nucleic acid folding and hybridization prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 31:3406–3415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.