Abstract

The nucleotide excision repair (NER) and spore photoproduct lyase DNA repair pathways are major determinants of Bacillus subtilis spore resistance to UV radiation. We report here that a putative ultraviolet (UV) damage endonuclease encoded by ywjD confers protection to developing and dormant spores of B. subtilis against UV DNA damage. In agreement with its predicted function, a His6-YwjD recombinant protein catalyzed the specific incision of UV-irradiated DNA in vitro. The maximum expression of a reporter gene fusion to the ywjD opening reading frame occurred late in sporulation, and this maximal expression was dependent on the forespore-specific RNA polymerase sigma factor, σG. Although the absence of YwjD and/or UvrA, an essential protein of the NER pathway, sensitized developing spores to UV-C, this effect was lower when these cells were treated with UV-B. In contrast, UV-B but not UV-C radiation dramatically decreased the survival of dormant spores deficient in both YwjD and UvrA. The distinct range of lesions generated by UV-C and UV-B and the different DNA photochemistry in developing and dormant spores may cause these differences. We postulate that in addition to the UvrABC repair system, developing and dormant spores of B. subtilis also rely on an alternative excision repair pathway involving YwjD to deal with the deleterious effects of various UV photoproducts.

INTRODUCTION

The constant exposure of cells and spores of Bacillus subtilis to a number of environmental factors of chemical and physical origin may result in the production of number of types of DNA lesions, including strand breaks, apurinic/apyrimidinic (AP) sites, UV-induced pyrimidine dimers (PD) of various types and chemically altered bases (21, 25, 43). B. subtilis possesses an arsenal of preventive and repair mechanisms to counteract the mutagenic and deleterious effects of these insults (5, 10, 28, 29, 30, 31, 33, 38, 53, 55). The expression of genes that prevent and repair genetic insults in this bacterium is regulated in time and space by gene circuitries that respond to developmental and environmental conditions during growth and cell differentiation (6, 23, 24, 28, 34, 38, 49, 54, 55).

When nutritional and/or environmental conditions trigger sporulation, B. subtilis undergoes a final round of DNA replication, followed by polar septation and segregation of the chromosomal copies between two unequal cell-sized compartments that follow dissimilar programs of gene expression (reviewed in references 9 and 27). The end product of sporulation is a highly resistant endospore with no detectable metabolism that lacks most common high-energy compounds (39). This endospore can remain dormant for long periods of time, until it encounters the appropriate conditions to germinate and resume growth (42). It has been proposed that the formation of the spore may potentially be compromised by damaging the chromosomes of either cell compartment and that the sporulating cell presumably relies on mechanisms to sense, repair, or even tolerate DNA damage in order to generate the two cell types (31). In support of these notions, results have revealed that defects in chromosome partitioning or DNA damage can delay sporulation at the level of Spo0A activation (4, 18) and that DisA, a scanning checkpoint protein, temporarily blocks the initiation of sporulation when DNA damage is encountered (2). A recent report (31) further demonstrated that YqjH/YqjW-dependent translesion synthesis operates in sporulating B. subtilis cells and contributes to the processing of spontaneous and artificially induced genetic damage.

B. subtilis spores are 10 to 20 times more resistant to the killing effects of ultraviolet C (UV-C) radiation than are vegetative cells of the same organism. Two mechanisms are responsible for elevated spore UV resistance. First, upon interacting with a group of small-acid-soluble spore proteins (termed α/β-type SASP), the chromosomal DNA of B. subtilis spores acquires an A-type conformation with altered DNA photochemistry, such that UV-C irradiation of spores induces the formation of a special type of PD termed spore photoproduct (SP) between adjacent thymidine residues (40, 41, 43). Second, accumulated SP are processed during spore germination with participation of two repair routes: (i) the SplB dimer, a member of the radical-SAM family, specifically recognizes and splits SP back into two thymidine residues and (ii) incision and excision through the nucleotide excision repair (NER) pathway (21, 29, 30, 40, 41, 43).

B. subtilis spores irradiated with solar or artificial UV-B light accumulate a wider spectrum of PDs than do spores irradiated with UV-C in which SP is by far the major photoproduct, since UV-B photoproducts in spores include not only SP but also cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers (CPDs) (44). B. subtilis does not contain a DNA photolyase that splits CPDs using a visible light-dependent mechanism (43). Therefore, germinating B. subtilis spores eliminate UV-B-induced CPDs and other UV pyrimidine adducts from spore DNA primarily through the NER pathway involving the UvrA protein and to a minor extent via repair that is dependent on the RecA protein (21, 38, 44, 51). We report here the existence of an alternative DNA repair mechanism encoded by ywjD that, together with the NER system, is involved in processing UV-induced DNA damage in dormant spores and developing spores of B. subtilis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and spore preparation.

The strains used in the present study are listed in Table 1. All B. subtilis strains are isogenic with and derived from a laboratory 168 strain. The growth medium used routinely was Luria-Bertani (LB) medium (20), and sporulation was induced in Difco sporulation medium (DSM) (37). When appropriate, ampicillin (Amp; 100 μg/ml), chloramphenicol (Cm; 5 μg/ml), kanamycin (Kan; 10 μg/ml), erythromycin (Er; 1 μg/ml), or IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside; 0.5 mM) was added to the media. Liquid cultures were incubated at 37°C with vigorous aeration. Spores of all strains were prepared at 37°C on 2× SG medium (2× DSM supplemented with 0.1% glucose) agar plates without antibiotics, and spores were harvested, cleaned, and stored as described previously (22). All dormant spore preparations used in the present study were free (≥98%) of growing cells, germinated spores, and cell debris as determined by phase-contrast microscopy. The optical density of the liquid cultures was monitored at 600 nm using an Ultrospec Pharmacia spectrophotometer.

Table 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmida | Genotype and descriptionb | Source or referencec |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| E. coli | ||

| XL10-Gold Kan | Tetr Δ(mcrA)183 Δ(mcrCB-hsdSMR-mrr)173 endA1 supE44 thi-1 recA1 gyrA96 relA1 lac Hte [F′ proAB lacIqZΔM15 Tn10 (Tetr) Tn5 (Kanr) Amy] | Stratagene, La Jolla, CA |

| DH5α | F− ϕ80dlacZΔM15 Δ(lacZYA argF)U169 deoR recA endA1 hsdR17(rK− mK+) supE44 thi-1 gyrA96 | Laboratory stock |

| PERM555 | DH5α harboring pPERM555; Ampr | This study |

| PERM635 | DH5α harboring pPERM635; Ampr | This study |

| PERM653 | DH5α harboring pPERM653; Ampr | This study |

| PERM661 | XL10 Gold harboring pPERM661; Ampr Kanr | This study |

| PERM972 | XL10 Gold harboring pPERM972; Ampr Kanr | This study |

| B. subtilis | ||

| 168 | trpC2 | Laboratory stock |

| WN118* | sigGΔ1 trpC2 | 46 |

| PERM639* | ΔywjD::lacZ; Err | pPERM635→168† |

| PERM985* | ΔuvrA::Cm; Cmr | pPERM972→168† |

| PERM1009* | ΔywjD::lacZ ΔuvrA::Cm Err Cmr | pPERM972→639† |

| PERM557* | trpC2 ywjD-lacZ; Cmr | pPERM555→168† |

| PERM755* | sigGΔ1 trpC2 ywjD-lacZ; Cmr | pPERM555→WN118† |

| Plasmids | ||

| pCR-Blunt-II-TOPO | Cloning vector | Invitrogen Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY |

| pJF751 | Integrational lacZ fusion vector; Ampr Cmr | 12 |

| pCP115 | Integrational vector; Ampr Cmr | BGSCd |

| pQE30 | Vector that contains a T5 promoter that enables N-terminal His6-tagged protein expression; Ampr | Qiagen, Inc., Valencia, CA |

| pMUTIN4 | Integrational vector; Ampr Emr | 50 |

| pPERM555 | 712-bp EcoRI/BamHI fragment of ywjD cloned in pJF751; Ampr Cmr | This study |

| pPERM635 | 615-bp HindIII/SacI fragment (internal region of ORF) of ywjD cloned in pMUTIN4; Ampr Err | This study |

| pPERM653 | 960-bp fragment of the ywjD ORF cloned in pCR-Blunt II TOPO; Kanr | This study |

| pPERM661 | 960-bp of the ywjD ORF cloned between the BamHI-PstI restriction sites of pQE30; Ampr | This study |

| pPERM972 | 867-bp EcoRI-BamHI (internal region of ORF) of uvrA cloned in pCP115; Ampr Cmr | This study |

*, The background for this strain is 168.

Ampr, ampicillin resistance; Cmr, chloramphenicol resistance; Err, erythromycin resistance; Kanr, kanamycin resistance.

†, DNA of the plasmid to the left of the arrow was used to transform the strain to the right of the arrow.

BGSC, Bacillus Genetic Stock Center.

Genetic and molecular biology techniques.

Preparation of competent Escherichia coli or B. subtilis cells and their transformation with plasmid DNA were performed as described previously (3, 35). Chromosomal DNA from B. subtilis was purified as described by Cutting and Vander Horn (7). Large-scale preparation and purification of plasmid DNA was accomplished using commercial ion-exchange columns, according to the instructions of the supplier (Qiagen, Inc., Valencia, CA). Small-scale preparation of plasmid DNA from E. coli cells, enzymatic manipulations, and agarose gel electrophoresis were performed by standard techniques (20, 35). PCR products were obtained with homologous oligonucleotides and Vent DNA polymerase (New England BioLabs, Ipswich, MA).

Design of a plasmid to overexpress ywjD.

The open reading frame (ORF) of ywjD lacking the first and stop codons was amplified by PCR utilizing Vent DNA polymerase and the oligonucleotide primers 5′-GGATCCATTTTCAGATTCGGGTTCGTT-3′ (forward) and 5-CTGCAGTGACTTCCATTGCAGCGCA-3′ (reverse), that inserted BamHI and PstI restriction sites, respectively, into the cloned DNA (the restriction site sequences are underlined). The PCR fragment was first ligated into PCR-Blunt-II-TOPO (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) and transformed into E. coli DH5α. The resulting construct (pPERM653) was cut with BamHI and PstI, and the 960-bp ywjD insert was purified and ligated into BamHI/PstI-treated pQE30 (Qiagen). This expression vector provided the start and stop codons, as well as an IPTG-inducible T5-promoter to direct the expression of the ywjD ORF. The resulting construct was transformed into E. coli XL-10 Gold (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA), generating E. coli strain PERM661. The plasmid in this strain was subjected to both restriction analysis and DNA sequencing to ensure the proper insertion of ywjD into pQE30, in which a His6 tag was fused in frame at the N-terminal coding region of ywjD.

Purification of His6-YwjD.

E. coli strain PERM661 was grown at 37°C in 50 ml of LB medium to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.5. At this point, the culture was supplemented with IPTG to a final concentration of 0.5 mM, and the expression of ywjD was induced for 2 h. Cells were collected by centrifugation and washed twice with 10 ml of 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 6.0)–150 mM NaCl (buffer A) and then disrupted in 10 ml of buffer A containing lysozyme (5 mg/ml) for 1 h at 37°C. The cell lysate was subjected to centrifugation (27,200 × g) to eliminate undisrupted cells and cell debris, and the supernatant was applied to 5-ml of Ni-NTA-agarose (Qiagen) column equilibrated with buffer A. The column was washed with 50 ml of buffer A alone and then with 50 ml of buffer A containing 10 mM imidazole, and then the protein bound to the resin was eluted with 6 ml of buffer A containing 200 mM imidazole; 1.5-ml fractions were collected during this last step. Aliquots (15 μl) were analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) as previously described (17).

Determination of His6-YwjD enzyme activity.

UV-endonuclease activity of His6-YwjD was assayed against a sample of closed circular plasmid pBR322 that was exposed to UV (450 J/m2) according to a previously described protocol (14). A typical reaction mixture in a volume of 25 μl contained 500 ng of purified His6-YwjD, 200 ng of purified unirradiated or irradiated plasmid pBR322 in 50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.9), 50 mM KCl, 15 mM MgCl2 and 1 mM dithiothreitol. The reactions were incubated at 37°C for 1 h and analyzed by electrophoresis on a 1% agarose gel that was stained with ethidium bromide. Since the enzymatic activity of the recombinant protein is identical to that reported in the extract of Schizosaccharomyces pombe cells, a reaction mixture containing 100 U (0.25 μg) of S. pombe UV-damage-endonuclease (Sp-Uvde1) (New England BioLabs) instead of His6-YwjD was used as a positive control.

Construction of a B. subtilis strain containing a ywjD-lacZ gene fusion.

Construction of an in-frame translational fusion between the ywjD gene and the E. coli lacZ gene was carried out in the integrative plasmid pJF751 (12) as follows. A 712-bp EcoRI/BamHI fragment extending from 661 bp upstream of the translation start codon of ywjD to 51 bp downstream of this point was amplified with Vent DNA polymerase (New England BioLabs), using chromosomal DNA from B. subtilis 168. The oligonucleotide primers used in the PCR were 5′-GAATTCGCGCATGATCGGAGAAGGCG-3′ (forward) and 5′-GGATCCCGCATCCCAAAGGCTCATCGC-3′ (reverse) (the restriction sites are underlined). The 712-bp PCR fragment was inserted between the EcoRI and BamHI sites of pJF751, and the resulting construct (pPERM555) was transformed into E. coli DH5α. Plasmid pPERM555 was introduced by transformation into competent cells of B. subtilis 168 (wild type), as well as into a B. subtilis ΔsigG strain (a generous gift from W. Nicholson, University of Florida), generating strains PERM557 and PERM755, respectively (Table 1).

β-Galactosidase assays.

B. subtilis strains carrying the ywjD-lacZ fusion were grown and sporulated at 37°C in liquid DSM. Cells from 1-ml samples were harvested by centrifugation during vegetative growth (Veg) and throughout sporulation. Cell pellets were frozen and stored at −20°C until the determination of β-galactosidase activity (12, 22). Briefly, washed cell samples were first disrupted with lysozyme and subjected to centrifugation. The β-galactosidase activity present in the supernatant fraction was measured and assigned to the mother cell fraction (which actually consisted of mother cells plus lysozyme-sensitive forespores). The pellets collected 4 to 8 h after T0 (the time when the slopes of the logarithmic and stationary phases of growth intersected), which consisted of lysozyme-resistant forespores containing spore coats, were subjected to spore coat removal (22) and washed in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) buffer, and a second round of lysozyme treatment was applied to the forespore fraction for determination of β-galactosidase activities (19, 22). The β-galactosidase activity was determined using ortho-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (ONPG) as a substrate and expressed in Miller units as described previously (22). The endogenous ONPGase specific activities expressed by the wild-type and sigG B. subtilis strains without a lacZ fusion during growth and sporulation were determined in parallel and subtracted from the data obtained for strains carrying the ywjD-lacZ fusion. The ONPGase activities in both strains lacking the ywjD-lacZ fusion gave similar values and fluctuated between 40% (Veg, T0 − T3) and 30% (T4 − T8) of the values determined in the ΔsigG strain carrying the ywjD-lacZ fusion.

RT-PCR.

Total RNA from vegetative and sporulating B. subtilis 168 cells was isolated using the TRI Reagent (RNA/DNA/protein isolation reagent; Molecular Research Center, Inc., Cincinnati, OH). Reverse transcription-PCRs (RT-PCRs) were performed for 29 cycles with the RNA samples and a Master Amp RT-PCR kit (Epicentre Technologies, Madison WI) according to the instructions of the provider. The primers used for RT-PCRs were 5′-CTGCGAACAAGCTTTCATC-3′ (forward) and 5′-GTTTGACACCGCGGATG-3′ (reverse) to generate a 555-bp RT-PCR product extending from 216 to 771 bp downstream from the start codon of ywjD. The absence of chromosomal DNA in the RNA samples was assessed by PCRs with Vent DNA polymerase (New England BioLabs) and the primer set described above.

Construction of mutant strains.

A construct to disrupt ywjD was generated in the integrative vector pMUTIN4 (50). To this end, a 615-bp HindIII-SacI internal fragment of the ywjD gene (from bp 313 to 928 downstream of the ywjD translational start codon) was amplified by PCR with Vent DNA polymerase (New England BioLabs), using chromosomal DNA from B. subtilis 168. The oligonucleotide primers for amplifying the ywjD fragment were 5′-AAGCTTCTGCGAACAAGCTTTCAT-3′ (forward) and 5′-GAGCTCGTTTGACACCGCGGATG-3′ (reverse) (the restriction sites are underlined). The ywjD PCR fragment was inserted between the HindIII and SacI restriction sites of pMUTIN4 (50). The resulting construct designated pPERM635 was generated in E. coli DH5α. Plasmid pPERM635 was used to transform wild-type B. subtilis generating strain PERM639 (Table 1). The presence of an IPTG-inducible Pspac promoter in pMUTIN4 allowed expression of genes located downstream of the disrupted ywjD gene avoiding polar effects in the resulting mutant. To inactivate the uvrA gene, an 849-bp internal DNA fragment of uvrA, extending from 867 to 1716-bp from the translational start site, was amplified by PCR using genomic DNA of B. subtilis 168 as a template and the oligonucleotide primers 5′-CGGAATTCGCCGATCTTGTCATCCCCA-3′ (forward) and 5′-GCGGATCCTATCACCTGTCCGCCGTGA-3′ (reverse) containing EcoRI or BamHI sites, respectively (underlined). PCR amplification of the target sequence was performed with Vent DNA polymerase (New England BioLabs). The uvrA fragment was recovered and cloned between the EcoRI-BamHI sites of integrative vector pCP115 (Bacillus Genetic Stock Center), generating plasmid pPERM972, which was transformed into E. coli DH5α. This plasmid was used to transform B. subtilis wild-type and PERM639 strains, generating strains PERM985 and PERM1009, respectively (Table 1).

UV irradiation of B. subtilis spores and sporulating cells.

Spores of the different strains were obtained and purified as described previously (22). To obtain sporulating cells, strains were grown overnight at 37°C in LB medium and diluted 50-fold into DSM, and growth at 37°C was monitored by determining the OD600. Samples for UV exposure were collected by centrifugation (5,000 × g) 5 h after the cessation of exponential growth (T5) and washed once with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 0.7% Na2HPO4, 0.3% KH2PO4, 0.4% NaCl [pH 7.5]).

Sporulating cells or spores (5 ml at an OD600 of 0.5 [1 × 106 to 3 × 106 viable count]) in PBS were stirred continuously and UV irradiated at room temperature. Artificial UV-C radiation was provided by a commercial low-pressure mercury arc lamp (model UVG-11; UV Products, Upland, CA) that emitted essentially monochromatic 254-nm UV radiation. Artificial UV-B radiation was provided by a commercial medium-pressure mercury arc lamp (model UVM-57; UV Products, Upland, CA) that emitted a spectrum of UV wavelengths from 280 to 320 nm, with peak emission at 302 nm. The UV dose produced by the lamps was measured using a model UVX radiometer (UV Products, Upland, CA). The survival of spores and sporulating cells during these treatments was measured by plating aliquots of serial dilutions in PBS on LB medium agar plates; colonies were counted after 24 to 48 h of incubation at 37°C. The experiments were repeated three times, and values were plotted as averages of triplicate determinations ± the standard deviations (SD). In all cases, killing curves were performed with different spore or sporulating cell preparations, and these yielded essentially similar (±20%) results.

Statistical analyses.

The 90% lethal dose (LD90) values (the UV dose in J/m2) to give 90% killing from experiments testing spore or sporulating cell resistance to UV-B and UV-C were evaluated by analysis of variance using commercial software (Kaleidagraph version 3.6.2; Synergy Software, Reading, PA). Differences with P values of ≤0.01 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Expression and purification of YwjD from E. coli.

Analysis of the ywjD coding sequence revealed an ORF of 960 bp that encodes a 36,740-Da protein. Amino acid sequence alignments (1) showed that YwjD exhibits homologies of 51, 52, and 47% with the UV-damage endonucleases from S. pombe Uvde1 (Sp-Uvde1) (47), Neurospora crassa Nc-Uvde (52), and Deinococcus radiodurans Uvs (48), respectively. It has been demonstrated that the enzymes belonging to the Uve/Uvs/Uvde protein family catalyze the incision of PD dimer containing DNA (13). However, to our knowledge, the biochemical function of the product encoded by ywjD has not been elucidated. Therefore, we produced and purified a recombinant YwjD protein. The ywjD ORF (960 bp) was produced in E. coli as an His6 N-terminal tagged protein, with expression of the fusion protein induced by IPTG. Initial expression attempts using ≥1 mM IPTG resulted in the production of inclusion bodies in the E. coli host cells (data not shown). However, induction with 0.5 mM IPTG for 1 or 2 h at 37°C generated significant amounts of a soluble protein with the expected ∼37-kDa molecular mass of YwjD (Fig. 1, lanes 3 and 4). This protein was purified to homogeneity by nickel chelate affinity chromatography (Fig. 1, lane 5).

Fig 1.

SDS-PAGE analysis of His6-YwjD induction and purification through a Ni-NTA-agarose column. E. coli strain PERM661 (XL10 Gold harboring pPERM661; Ampr Kanr) was grown at 37°C in 50 ml of LB medium to an OD600 of 0.5. IPTG induction of ywjD expression and purification of His6-YwjD was performed as described in Materials and Methods. Aliquots (15 μl) of cell lysates (lanes 2 to 4) or from the peak protein fraction eluted from the Ni-NTA agarose column with 200 mM imidazole (lane 5) were electrophoresed on an SDS-polyacrylamide (12%) gel that was stained with Coomassie blue. Lane 1 shows the molecular mass standards.

YwjD induces the specific nicking of a CPD-containing DNA substrate.

To investigate whether ywjD encodes a protein capable of acting on a DNA substrate containing CPDs, we first prepared a plasmid containing this type of lesion. An E. coli strain harboring plasmid pBR322 was exposed to a UV-C dose of 450 J/m2, since this treatment induces the formation of three to four CPDs per plasmid molecule (14), and the plasmid was purified from both irradiated and unirradiated cells. In agreement with its predicted function, the purified His6-YwjD protein specifically promoted the incision of the CPD-containing plasmid (Fig. 2A, lane 2, and Fig. 2C). Importantly, the recombinant enzyme was unable to nick unirradiated pBR322 (Fig. 2B, lane 2, and Fig. 2D). As a positive control, we utilized commercially available Sp-Uvde1 that was incubated with samples of pBR322 with or without CPDs. As in the case of YwjD, Sp-Uvde1 catalyzed the incision of the CPD-containing plasmid DNA (Fig. 2A, lane 3, and Fig. 2C) and left the unirradiated plasmid intact (Fig. 2B, lane 3, and Fig. 2D).

Fig 2.

(A to D) Endonuclease activity of His6-YwjD. (A) CPD-pBR322 (0.2 μg) was incubated without (lane 1) or with either His6-YwjD (0.5 μg; lane 2) or Sp-Uvde1 (0.25 μg; lane 3). (B) Unirradiated pBR322 (0.2 μg) was incubated without (lane 1) or with either His6-YwjD (1 μg; lane 2) or Sp-Uvde1 (0.25 μg; lane 3). The reactions were incubated for 1 h at 37°C and analyzed by electrophoresis on a 1% agarose gel, which was stained with ethidium bromide. (C and D) Densitometry of the experiments described in panels A and B, respectively. Quantification of the band intensity was accomplished by densitometry using Quantity One 1-D software from Bio-Rad Laboratories (Hercules, CA). The abbreviations used in panels A, B, C, and D denote the migration positions of covalently closed circular plasmid (CCC) and nicked circular plasmid (OC). The results shown in panels C and D are representative of two experiments that yielded essentially similar (±20%) results.

Analysis of ywjD expression during growth and sporulation.

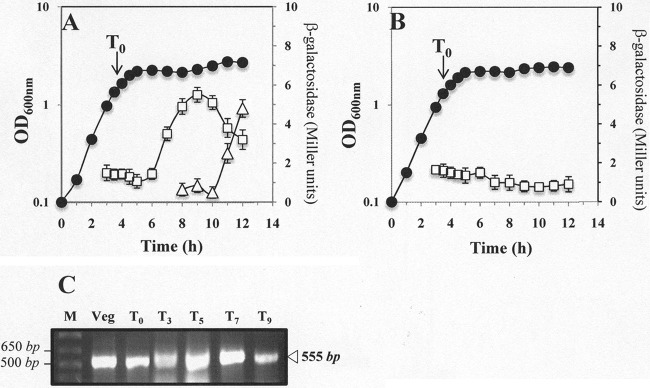

To determine when in the B. subtilis life cycle YwjD is expressed, the temporal pattern of ywjD expression was determined using two approaches. First, a B. subtilis strain harboring a translational ywjD-lacZ gene fusion was grown and sporulated in liquid DSM, and samples were harvested at various times and assayed for β-galactosidase. The results indicated that low levels of the reporter gene fusion protein were present during logarithmic growth and early in sporulation, with maximal levels reached at 5 h after sporulation (Fig. 3A, T5). To further investigate whether ywjD is transcribed throughout the B. subtilis life cycle, total RNA samples were isolated from a wild-type B. subtilis culture during growth and sporulation and processed for RT-PCR. The RT-PCR results showed the presence of mRNAs of ywjD not only in exponentially growing cells but also both early and late in sporulation (Fig. 3C).

Fig 3.

(A to C) Levels of β-galactosidase from B. subtilis wild-type (A) and ΔσG (B) strains containing a ywjD-lacZ fusion and RT-PCR analysis of ywjD transcription (C). (A and B) B. subtilis strains PERM557 (ywjD-lacZ) (A) and PERM755 (sigGΔ1 ywjD-lacZ) (B) were grown at 37°C in DSM (●). Cell samples were collected in vegetative growth (Veg) and at various times during sporulation and treated with lysozyme, and the extracts were assayed for β-galactosidase as described in Materials and Methods (□). In panel A, the β-galactosidase activity inside lysozyme-resistant forespores (△) was assayed as described in Materials and Methods. The values shown are averages of duplicate independent experiments ± the SD of the β-galactosidase specific activity expressed as Miller units (22). (C) RNA samples (∼1 μg) isolated from a B. subtilis 168 DSM culture at the times indicated were processed for RT-PCR analysis as described in Materials and Methods. The arrowhead shows the size of the expected RT-PCR products. Lanes: M, DNA markers, 1-kb Plus ladder; Veg, logarithmic growth; T0, the time when the slopes of the logarithmic and stationary phases of growth intersected; T1 to T9, times in hours after T0.

The maximum level of β-galactosidase from the ywjD-lacZ fusion was achieved late in sporulation, and this level then fell as sporulation proceeded. This behavior is similar to that of genes expressed primarily if not exclusively in the forespore compartment of the sporulating cell, and often under the control of the RNA polymerase forespore-specific sigma factor, σG (15). Indeed, further analysis showed that the ywjD-directed β-galactosidase activity accumulated inside lysozyme-resistant forespores beginning at T6 and continued to accumulate until at least T8, confirming that expression of the reporter gene occurred inside the developing spore (Fig. 3A). Since many genes expressed specifically in developing forespores are transcribed by RNA polymerase with the forespore-specific sigma factor σG (EσG), we examined the levels of β-galactosidase from the ywjD-lacZ fusion in a sigG strain (Fig. 3B). Strikingly, ywjD-lacZ expression did not increase during sporulation of the sigG strain, although expression was similar to that given by the lacZ fusion in the wild-type strain during logarithmic growth (Fig. 3A).

Role of YwjD in resistance of B. subtilis spores to UV radiation.

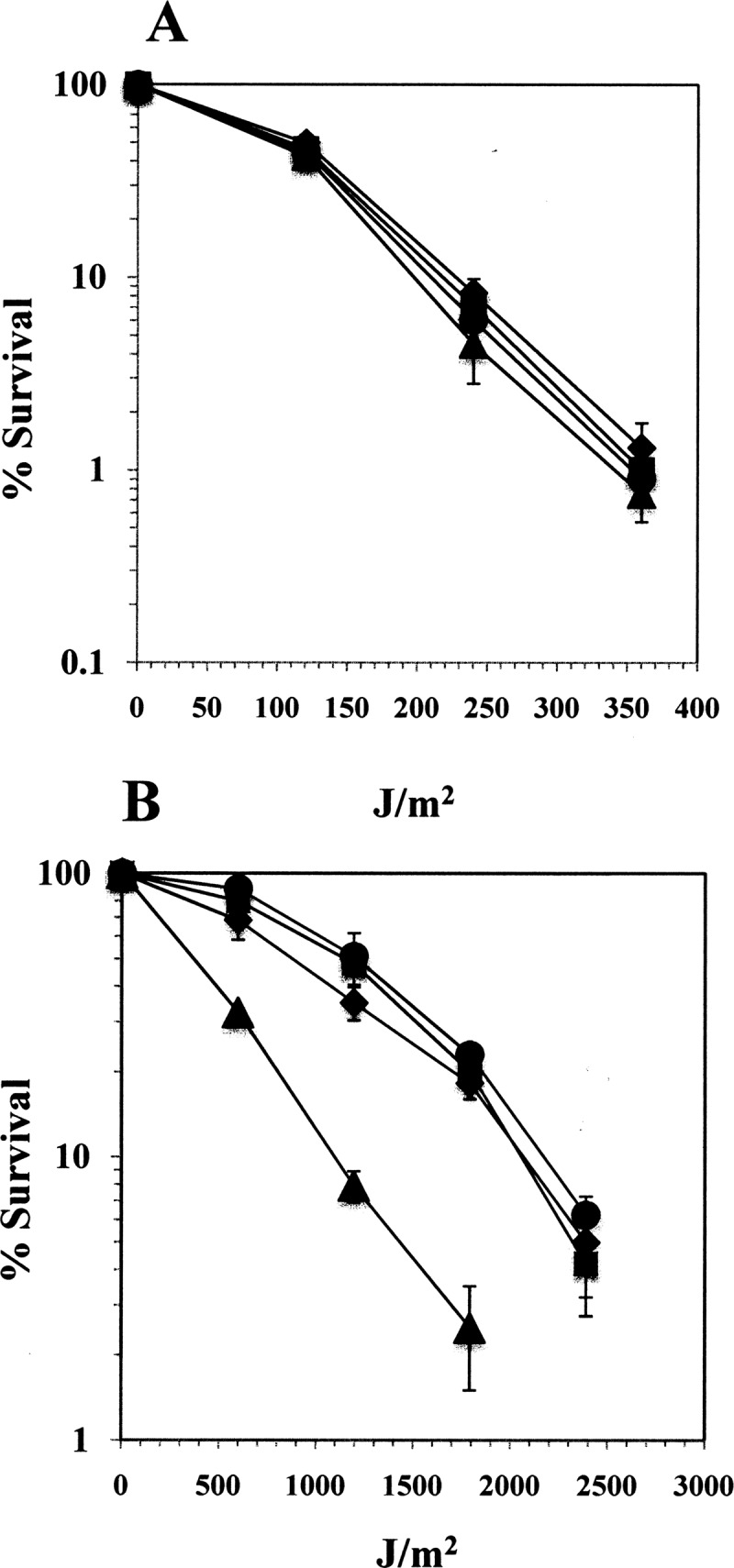

The expression pattern of ywjD during late sporulation, and its σG dependence at this time is reminiscent of genes whose transcription is confined to the forespore compartment, such as splB, sspA, and sspB, genes encoding proteins important in spore UV resistance (11, 19, 23, 24). This is also consistent with the rapid apparent decrease in β-galactosidase specific activity following T6 that may be due to the inability to assay β-galactosidase when it becomes packaged into the maturing spore (19). Since it is likely that there are significant levels of YwjD in dormant spores (Fig. 3A), it is possible that this YwjD is involved in protecting B. subtilis spores against UV-induced DNA damage. However, disruption of either ywjD or uvrA alone did not sensitize dormant spores to UV-B or UV-C (Fig. 4). Thus, the LD90s to UV-C radiation of wild-type spores (210 ± 8.1 J/m2) and those calculated for the single ywjD (217.5 ± 12.5 J/m2) and uvrA (223 ± 6.2 J/m2) spores were not significantly different (Fig. 4A). In contrast, dormant spores carrying mutations in both of these DNA repair genes were significantly more sensitive to UV-B (Fig. 4B), and the LD90 values were 2,125 ± 30 J/m2 for wild-type spores and 1,075 ± 25 J/m2 for the ywjD uvrA spores. However, the spores of the double knockout strain were not more susceptible to UV-C than were the wild-type spores (Fig. 4A), with LD90 values of 195 ± 15 J/m2 (ywjD uvrA) and 210 ± 18 J/m2 (wild type), respectively. Together, these results suggest that the type of DNA damage generated by UV-B but not by UV-C is eliminated during spore germination by the concomitant action of YwjD and the NER pathway.

Fig 4.

(A and B) Resistance of wild-type, ywjD, uvrA, and ywjD uvrA spores to UV-C (A) and UV-B (B). The spores obtained from B. subtilis wild-type (●), PERM639 (ywjD [■]), PERM985 (uvrA [◆]), and PERM1009 (ywjD uvrA [▲]) strains were assayed for UV-C (A) or UV-B (B) resistance as described in Materials and Methods. The results are expressed as averages ± the SD of three independent experiments.

Role of YwjD in resistance of developing B. subtilis sporangia to UV radiation.

The physiological significance of the expression of ywjD during forespore development was further analyzed by examination of the effects of loss of ywjD on the resistance of T5 sporulating cells of various strains to UV-B and UV-C. T5 sporulating cells were chosen for this analysis because the levels of β-galactosidase from ywjD-lacZ were maximal at this time (Fig. 3A). This analysis revealed that the absence of YwjD slightly but significantly increased the susceptibility of T5 sporangia to 254-nm UV radiation (Fig. 5A), since the calculated LD90s for sporangia of the ywjD and wild-type strains were 62 ± 8 and 95.3 ± 7 J/m2, respectively.

Fig 5.

(A and B) Resistance of developing wild type, ywjD, uvrA, and ywjD uvrA T5 sporangia to UV-C (A) and UV-B (B). B. subtilis wild-type (●), PERM639 (ywjD [■]), PERM985 (uvrA [◆]), and PERM1009 (ywjD uvrA [▲]) strains were sporulated in DSM. The sporulating cells were isolated 5 h after the end of logarithmic growth and treated with different doses of UV-C or UV-B, and the cell viability was determined as described in Materials and Methods. The results are expressed as averages ± the SD of at least three independent experiments.

Although the contribution of the NER system in conferring protection to vegetative cells and spores from the noxious effects of UV radiation has been well established (6, 41, 51, 52), the role played by this pathway in protecting sporangia from UV radiation is unknown. Our results showed that in comparison to the parental wild-type strain, the absence of UvrA, an essential component of the NER pathway (53), greatly increased the susceptibility of the B. subtilis T5 sporangia to UV-C radiation (Fig. 5A), and this susceptibility was further increased by the loss of both YwjD and UvrA (Fig. 5A). Sporangia from the wild-type, ywjD, uvrA, and ywjD uvrA strains exhibited significantly different LD90s to UV-C of 95.3 ± 7, 64.6 ± 3.1, 13.5 ± 2.5, and 2.9 ± 0.5 J/m2, respectively.

We next investigated the relative contributions of YwjD and/or NER in protecting the T5 sporangia from artificial UV-B light. The results revealed that sporulating cells from the uvrA strain were more sensitive to UV-B than those from the wild-type strain, whereas the loss of ywjD alone did not increase the susceptibility of sporangia to UV-B (Fig. 5B). However, sporulating cells lacking both YwjD and UvrA were more sensitive to UV-B than uvrA sporangia (Fig. 5B). The LD90s for UV-B with strains lacking YwjD and/or UvrA were 189.6 ± 7.8 J/m2 (wild type), 191.7 ± 5 J/m2 (ywjD), 35.7 ± 4.3 J/m2 (uvrA), and 21.3 ± 2.9 J/m2 (ywjD uvrA).

DISCUSSION

UV-damage endonucleases are distributed among organisms of different species, and they are involved in processing PD-containing DNA using alternative excision repair mechanisms (13). Although it has been demonstrated that these enzymes incise DNA immediately 5′ to PDs, the postincision event(s) that completes this repair mechanism is not fully understood (13). The in vivo function of the N. crassa and S. pombe UVDE homologs was inferred from their ability to decrease the UV-C radiation susceptibility of E. coli strains deficient on NER, recombination and/or photolyase activities (47, 52). In D. radiodurans, such susceptibility was only evident when both the UvsE protein and the NER pathways were inactivated (48).

It was previously shown that expression of a B. subtilis genomic sequence, termed Z49782, encoding a predicted protein with regional homology to SP-Uve1, decreased the UV susceptibility of an E. coli strain deficient in light-dependent photoreversion, recombination, and NER (47). An inspection of the B. subtilis chromosome (16; GenoList/SubtiList from Institut Pasteur Genopole) indicated that Z49782 encoded a product that was similar to an ORF termed ywjD, although the former contained an extra C-terminal 24-residues long peptide. The results of an in silico analysis revealed that YwjD shares 52 to 54% amino acid sequence homology with UV-damage endonucleases of fungal and bacterial origin that belong to the Uve/Uvs/UvdE protein family (1). We demonstrated here that purified His6-YwjD protein generated from the correct ywjD ORF, namely, 960 bp (16), specifically nicked a UV-irradiated plasmid substrate, strongly suggesting that YwjD possesses properties required for involvement in repair of UV-C-induced PD. The substrate specificity of YwjD remains to be determined, since the UV irradiated plasmid used in this assay may contain UV-induced lesions in addition to CPDs such as pyrimidine(6-4)pyrimidone photoproducts (13).

Analysis of the B. subtilis chromosome (16; GenoList/SubtiList from Institut Pasteur Genopole) reveals that ywjD is flanked upstream by ywjE encoding a cardiolipin synthetase and downstream by ywjC a gene whose function has not been determined. The intergenic region between ywjE and ywjD is only 12 bp, suggesting that both genes are part of a bicistronic operon (and see below). In contrast, previous results have shown that ywjC belongs to the σB regulon (26); therefore, a promoter recognized by σB presumably directs the independent transcription of this gene.

In the present study, we found that ywjD is expressed throughout the life cycle of B. subtilis, since ywjD mRNA was detected during growth and sporulation. Expression studies with a ywjD-lacZ fusion showed that β-galactosidase from this fusion exhibited a temporal pattern of expression similar to that of EσG-dependent genes whose expression occurs in the forespore compartment. Consistent with these results, the sporulation-associated expression of the ywjD-lacZ fusion was dependent on the σG protein, confirming results of a microarray study that showed that ywjD belongs to the σG regulon (45). Indeed, both ywjE and ywjD are members of the σG regulon, which is consistent with these two genes being in an operon. In conjunction, these results strongly suggest that expression of ywjD during sporulation is carried out by EσG, the holoenzyme that transcribes most sporulation genes in the forespore compartment (9, 27, 32).

Based on the results of expression analysis of ywjD and the significant expression of this gene during sporulation, the UV resistance properties of developing and dormant spores lacking YwjD and/or UvrA were determined. In our experimental conditions the single disruption of either ywjD or uvrA did not sensitize spores to UV-B, suggesting that neither of these systems alone is essential to protect to spores from this type of radiation. This result was unexpected since Slieman and Nicholson (44) have demonstrated that UV-B irradiation of dormant B. subtilis spores results in a major production of CPDs and both YwjD and NER are supposed to repair this type of lesion (44). However, when both repair systems were inactivated, a dramatic decline in spore resistance to this type of radiation was observed. Taken collectively, our results strongly suggest that UV-B-promoted PDs are eliminated from the spore chromosome during spore germination by NER and by an alternative excision repair process that employs YwjD.

The A-type conformation adopted by the spore chromosome promotes the production of the unique PD SP following UV-C radiation (21, 40). The results described in the present study suggested that YwjD is most probably not involved in processing SP, since spores deficient in this protein were not sensitized to UV-C. A similar result was obtained when both uvrA and ywjD were disrupted. Therefore, we conclude that damage inflicted by UV-C on the chromosome of spores lacking YwjD and UvrA is most likely repaired by SplB and RecA during spore germination/outgrowth (21, 38, 40).

YwjD and NER also clearly had a role in conferring protection on T5 sporangia against UV radiation. Analysis of this protection was complicated because there are two cell types in T5 sporangia, the mother cell and the developing forespore, either of which could in theory give rise to a colony. However, by T5 in sporulation under these conditions, the majority of sporangia are committed to proceed through sporulation with eventual mother cell lysis before giving rise to a growing cell, and therefore the colonies generated from T5 sporangia are largely derived from the developing forespores. The UV resistance of T5 sporangia is thus determined by developing forespores' UV photochemistry, their complement of DNA repair proteins, and their maintenance of sufficient levels of ATP and general enzyme activity to allow DNA repair in the developing forespore itself, as well as possible repair of DNA lesions acquired in sporulation only following spore germination. Keeping these facts in mind, it was clear that NER played the major role in protecting T5 sporangia from both UV-C and UV-B radiation, since the inactivation of uvrA was enough to sensitize these cells to both types of radiation, whereas the disruption of ywjD alone only slightly increased the susceptibility of T5 sporangia to UV-C. However, YwjD did play a role in protecting T5 sporangia from UV-B, since the disruption of ywjD increased the susceptibility of the resulting ywjD uvrA strain to this type of radiation. We propose that the different contributions of YwjD in protecting T5 sporangia from UV-C and UV-B radiation probably depends on the UV photochemistry and the large amount of CPDS induced by this physical factor in developing forespores at this developmental stage. In support of this contention, it has been shown that the spore-specific DNA photochemistry is dependent not only on the SASP that are expressed 3 to 4 h after the onset of sporulation but also on the dehydration state of the spore core, as well as its accumulation of dipicolinic acid, and dipicolinic acid uptake and full spore core dehydration take place 1 to 2 h after SASP accumulation (8, 19). It has also been established that UV-C generally induces a much higher proportion of CPDs than UV-B in SASP-free DNA (36). Taken collectively, our results support the idea that under conditions of extreme UV radiation, the developing spore eliminates PDs by incision/excision (NER) and alternative excision repair (YwjD), assuring completion of the sporulation process. Importantly, the UV sensitivity exhibited by mature and developing spores lacking ywjD cannot be attributed to a polar effect, since supplementation of ywjD cultures with IPTG to induce the expression of the downstream ywjC gene did not affect sporulating cells' UV sensitivity (data not shown). Repair of UV-induced DNA damage is indeed important during spore morphogenesis and may proceed in an error-prone manner since a recent report showed that the absence of translesion DNA polymerases YqjH and YqjW not only resulted in inefficient sporulation but also sensitized sporulating B. subtilis cells to UV-C (31). Indeed, repair or bypassing of UV-C-induced PDs in this developmental stage may be directed to actively transcribed genes since these repair processes seem to require the transcriptional repair coupling factor Mfd (31; F. H. Ramírez-Guadiana and M. Pedraza-Reyes, unpublished results).

Finally, the evidence presented here indicates that YwjD catalyzed the incision of CPD-containing DNA. However, the mechanism that completes the repair process in B. subtilis is currently unknown. In S. pombe two such mechanisms have been proposed: (i) incision on the 3′ side of the UV lesion by the Rad2 flap endonuclease, generating a 3′-OH end that is extended by a DNA polymerase, followed by synthesis of the phosphodiester bond, and (ii) the recombination subpathway, which requires the Exo1 Rhp51 and Rad18 proteins (13). The B. subtilis genome lacks sequences encoding proteins with evident homology to flap endonucleases. Therefore, additional work will be necessary to identify the protein(s) involved in the postincision events that complete the repair process initiated by YwjD in B. subtilis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by University of Guanajuato and by Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología (CONACYT; grant 84482) of Mexico. M.B.-S., F.H.R.-G., and M.O.-C. were supported by scholarships from CONACYT.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 7 September 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Altschul SF, et al. 1997. Gapped blast and PSI-blast: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:3389–3402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bejerano-Sagie M, et al. 2006. A checkpoint protein that scans the chromosome for damage at the start of sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. Cell 125:679–690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Boylan RJ, Mendelson NH, Brooks D, Young FE. 1972. Regulation of the bacterial cell wall: analysis of a mutant of Bacillus subtilis defective in biosynthesis of teichoic acid. J. Bacteriol. 110:281–290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Burkholder WF, Kurtser I, Grossman AD. 2001. Replication initiation proteins regulate a developmental checkpoint in Bacillus subtilis. Cell 104:269–279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Castellanos-Juárez FX, et al. 2006. YtkD and MutT protect vegetative cells but not spores of Bacillus subtilis from oxidative stress. J. Bacteriol. 188:2285–2289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cheo DL, Bayles KW, Yasbin RE. 1993. Elucidation of regulatory elements that control damage induction and competence induction of the Bacillus subtilis SOS system. J. Bacteriol. 18:5907–5915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cutting SM, Vander Horn PB. 1990. Genetic analysis, p 27–74 In Harwood CR, Cutting SM. (ed), Molecular biological methods for Bacillus. John Wiley & Sons, Sussex, England [Google Scholar]

- 8. Douki T, Setlow B, Setlow P. 2005. Photosensitization of DNA by dipicolinic acid, a major component of spores of Bacillus species. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 4:591–597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Errington J. 2003. Regulation of endospore formation in Bacillus subtilis. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 1:117–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fajardo-Cavazos P, Salazar C, Nicholson WL. 1993. Molecular cloning and characterization of the Bacillus subtilis spore photoproduct lyase (spl) gene, which is involved in repair of UV radiation-induced DNA damage during spore germination. J. Bacteriol. 175:1735–1744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fajardo-Cavazos P, Tovar-Rojo F, Setlow P. 1991. Effect of promoter mutations and upstream deletions on the expression of genes coding for small, acid-soluble spore proteins of Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 173:2011–2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ferrari E, Howard SMH, Hoch JA. 1985. Effect of sporulation mutations on subtilisin expression assayed using a subtilisin-β-galactosidase gene fusion, p 180–184 In Hoch JA, Setlow P. (ed), Molecular biology of microbial differentiation. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 13. Friedberg EC, et al. 2006. DNA repair and mutagenesis, 2nd ed. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gruskins EA, Lloyd RS. 1987. Molecular analysis of plasmid DNA repair within ultraviolet irradiated Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 263:12728–12737 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Haldenwang WG. 1995. The sigma factors of Bacillus subtilis. Microbiol. Rev. 59:1–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kunst F, et al. 1997. The complete genome sequence of the gram-positive Bacillus subtilis. Nature 390:249–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Laemmli UK. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227:680–685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lemon KP, Kurtser I, Wu J, Grossman AD. 2000. Control of initiation of sporulation by replication initiation genes in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 182:2989–2991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mason JM, Hackett RH, Setlow P. 1988. Regulation of expression of genes coding for small, acid-soluble spore proteins of Bacillus subtilis spores: studies using lacZ gene fusions. J. Bacteriol. 170:239–244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Miller JH. 1972. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- 21. Nicholson WL, Munakata N, Horneck G, Melosh HJ, Setlow P. 2000. Resistance of Bacillus endospores to extreme terrestrial and extraterrestrial environments. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 64:548–572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nicholson WL, Setlow P. 1990. Sporulation, germination, and outgrowth, p 391–450 In Harwood CR, Cutting SM. (ed), Molecular biological methods for Bacillus. John Wiley & Sons, Sussex, England [Google Scholar]

- 23. Pedraza-Reyes M, Gutierrez-Corona F, Nicholson WL. 1997. Spore photoproduct lyase operon (splAB) regulation during Bacillus subtilis sporulation: modulation of splB-lacZ fusion expression by P1 promoter mutations and by an in-frame deletion of splA. Curr. Microbiol. 34:133–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pedraza-Reyes M, Gutierrez-Corona F, Nicholson WL. 1994. Temporal regulation and forespore-specific expression of the spore photoproduct lyase gene by sigma-G RNA polymerase during Bacillus subtilis sporulation. J. Bacteriol. 176:3983–3991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pedraza-Reyes M, Ramírez-Ramírez N, Vidales-Rodríguez LE, Robleto EA. 2012. Mechanisms of bacterial spores survival, p 73–84 In Abel-Santos E. (ed), Bacterial spores: current research and applications. Caister Academic Press, Wymondham, United Kingdom [Google Scholar]

- 26. Petersohn A, et al. 2001. Global analysis of the general stress response of Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 183:5617–5631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Piggot PJ, Hilbert DW. 2004. Sporulation of Bacillus subtilis. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 7:579–586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ramírez MI, Castellanos FX, Yasbin RE, Pedraza-Reyes M. 2004. The ytkD (mutTA) gene of Bacillus subtilis encodes a functional antimutator 8-oxo-(dGTP/GTP)ase and is under dual control of sigma A and sigma F RNA polymerase. J. Bacteriol. 186:1050–1059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rebeil R, Nicholson WL. 2001. The subunit structure and catalytic mechanism of the Bacillus subtilis DNA repair enzyme spore photoproduct lyase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98:9038–9043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rebeil R, et al. 1998. Spore photoproduct lyase from Bacillus subtilis spores is a novel iron-sulfur DNA repair enzyme which shares features with proteins such as class III anaerobic ribonucleotide reductases and pyruvate-formate lyases. J. Bacteriol. 180:4879–4885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rivas-Castillo AM, Yasbin RE, Robleto E, Nicholson WL, Pedraza-Reyes M. 2010. Role of the Y-family DNA polymerases YqjH and YqjW in protecting sporulating Bacillus subtilis cells from DNA damage. Curr. Microbiol. 60:263–267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Robleto EA, Martin HA, Pepper AM, Pedraza-Reyes M. 2012. Gene regulation of sporulation in Bacillus subtilis, p 9–18 In Abel-Santos E. (ed), Bacterial spores: current research and applications. Caister Academic Press, Wymondham, United Kingdom [Google Scholar]

- 33. Salas-Pacheco JM, Setlow B, Setlow P, Pedraza-Reyes M. 2005. Role of the Nfo (YqfS) and ExoA apurinic/apyrimidinic endonucleases in protecting Bacillus subtilis spores from DNA damage. J. Bacteriol. 187:7374–7381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Salas-Pacheco JM, Urtiz-Estrada N, Martínez-Cadena G, Yasbin RE, Pedraza-Reyes M. 2003. YqfS from Bacillus subtilis is a spore protein and a new functional member of the type IV apurinic/apyrimidinic-endonuclease family. J. Bacteriol. 185:5380–5390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor N.Y [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sato T, et al. 1996. Differential effect of UV-B and UV-C on DNA damage in L-132 cells. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 19:721–725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Schaeffer P, Millet J, Aubert JP. 1965. Catabolic repression of bacterial sporulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 54:704–711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Setlow B, Setlow P. 1996. Role of DNA repair in Bacillus subtilis spore resistance. J. Bacteriol. 178:3486–3495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Setlow P. 1981. Biochemistry of bacterial forespore development and spore germination, p 13–28 In Levinson HS, Tipper DJ, Sonenshein AL. (ed), Sporulation and germination. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 40. Setlow P. 2007. I will survive: DNA protection in bacterial spores. Trends Microbiol. 15:172–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Setlow P. 2001. Resistance of spores of Bacillus species to ultraviolet light. Environ. Mol. Mutagen. 38:97–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Setlow P. 2003. Spore germination. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 6:550–556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Setlow P. 2006. Spores of Bacillus subtilis: their resistance to and killing by radiation, heat and chemicals. J. Appl. Microbiol. 101:514–525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Slieman TA, Nicholson WL. 2000. Artificial and solar UV radiation induces strand breaks and cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers in Bacillus subtilis spore DNA. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:199–205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Steil L, Serrano M, Henriques AO, Völker U. 2005. Genome-wide analysis of temporally regulated and compartment-specific gene expression in sporulating cells of Bacillus subtilis. Microbiology 151:399–420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Sun D, Stragier P, Setlow P. 1989. Identification of a new σ-factor involved in compartmentalized gene expression during sporulation of Bacillus subtilis. Genes Dev. 3:141–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Takao M, Yonemasu R, Yamamoto K, Yasui A. 1996. Characterization of a UV endonuclease gene from the fisson yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe and its bacterial homolog. Nucleic Acids Res. 24:1267–1271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Tanaka M, et al. 2005. Characterization of pathways dependent on the uvsE, uvrA1, or uvrA2 gene product for UV resistance in Deinococcus radiodurans. J. Bacteriol. 187:3693–3697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Urtiz-Estrada N, Salas-Pacheco JM, Yasbin RE, Pedraza-Reyes M. 2003. Forespore-specific expression of Bacillus subtilis yqfS, which encodes type IV apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease, a component of the base excision repair pathway. J. Bacteriol. 185:340–348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Vagner V, Dervyn E, Ehrlich D. 1998. A vector for systematic gene inactivation in Bacillus subtilis. Microbiology 144:3097–3104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Xue Y, Nicholson WL. 1996. The two major spore DNA repair pathways, nucleotide excision repair and spore photoproduct lyase, are sufficient for the resistance of Bacillus subtilis spores to artificial UV-C and UV-B but not to solar radiation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:2221–2227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Yajima H, et al. 1995. A eukaryotic gene encoding an endonuclease that specifically repairs DNA damaged by ultraviolet light. EMBO J. 14:2393–2399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Yasbin RE, Cheo D, Bol D. 1993. DNA repair systems, p 529–537 In Sonenshein AL, Losick R, Hoch JA. (ed), Bacillus subtilis and other gram-positive organisms. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 54. Yasbin RE, Cheo D, Bayles KW. 1992. Inducible DNA repair and differentiation in Bacillus subtilis: interactions between global regulons. Mol. Microbiol. 10:1263–7120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Yasbin RE, Cheo D, Bayles KW. 1991. The SOB system of Bacillus subtilis: a global regulon involved in DNA repair and differentiation. Res. Microbiol. 142:885–892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]