Abstract

Several lysines (Lys) were determined to be involved in the regulation of the ADP-glucose (Glc) pyrophosphorylase from spinach leaf and the cyanobacterium Anabaena sp. PCC 7120 (K. Ball, J. Preiss [1994] J Biol Chem 269: 24706–24711; Y. Charng, A.A. Iglesias, J. Preiss [1994] J Biol Chem 269: 24107–24113). Site-directed mutagenesis was used to investigate the relative roles of the conserved Lys in the heterotetrameric enzyme from potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) tubers. Mutations to alanine of Lys-404 and Lys-441 on the small subunit decreased the apparent affinity for the activator, 3-phosphoglycerate, by 3090- and 54-fold, respectively. The apparent affinity for the inhibitor, phosphate, decreased greater than 400-fold. Mutation of Lys-441 to glutamic acid showed even larger effects. When Lys-417 and Lys-455 on the large subunit were mutated to alanine, the phosphate inhibition was not altered and the apparent affinity for the activator decreased only 9- and 3-fold, respectively. Mutations of these residues to glutamic acid only decreased the affinity for the activator 12- and 5-fold, respectively. No significant changes were observed on other kinetic constants for the substrates ADP-Glc, pyrophosphate, and Mg2+. These data indicate that Lys-404 and Lys-441 on the small subunit are more important for the regulation of the ADP-Glc pyrophosphorylase than their homologous residues in the large subunit.

ADP-Glc PPase (ATP:α-Glc-1-P adenylyltransferase, EC 2.7.7.27) catalyzes the synthesis of ADP-Glc from Glc-1-P and ATP, releasing PPi as a product. This reaction is considered a prime regulatory step in the synthesis of bacterial glycogen and starch in plants (Preiss, 1984, 1988, 1991, 1997a).

Potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) tuber ADP-Glc PPase is activated by 3-PGA and inhibited by Pi, as are most higher-plant, algal, and cyanobacterial ADP-Glc PPases (Preiss, 1982, 1988, 1991, 1997a). The enzyme from cyanobacteria is homotetrameric, as are other enzymes from bacteria (Iglesias et al., 1991; Kakefuda et al., 1992). Conversely, all of the ADP-Glc PPases from higher plants studied so far, including the potato tuber enzyme, are heterotetramers composed of two distinct subunits (Okita et al., 1990). Even though there is little difference in molecular mass, use of the terms “large” for the 51-kD subunit and “small” for the 50-kD subunit has been retained, because they have homology to the large and small subunits, respectively.

The amino acid sequences of the small subunit of higher-plant ADP-Glc PPases are highly conserved, but there is less similarity among the large subunits (Smith-White and Preiss, 1992). It has been suggested that the major function of the large subunit is to modify regulatory properties of the small subunit, which is the subunit primarily involved in catalysis (Ballicora et al., 1995).

The genes of both subunits of the potato tuber ADP-Glc PPase have been cloned (Nakata et al., 1991). The cDNAs corresponding to the two subunits of the potato enzyme have been expressed in an Escherichia coli strain (AC70R1-504) deficient in ADP-Glc PPase activity (Iglesias et al., 1993; Ballicora et al., 1995). This recombinant enzyme was composed of two large subunits and two small subunits to yield a heterotetrameric (L2S2) native structure, as shown by N-terminal sequencing (Preiss, 1997b). This expression system allowed us to study the interaction between subunits and the roles played by each in heterotetrameric enzymes from higher plants.

The first structural study on the regulatory site of the plant enzymes was performed on the ADP-Glc PPase purified from spinach leaves. After chemical modification with pyridoxal 5′-phosphate, protection with effectors, and sequencing of the peptides, covalently modified Lys residues involved in allosteric regulation were identified. These residues were involved in the binding of either the activator, 3-PGA, or the inhibitor, Pi, (Ball and Preiss, 1994). Three of the Lys residues are highly conserved in the enzymes from higher plants and cyanobacteria (Table I, s-II, l-I, l-II). Two are equivalent (s-II and l-II), one corresponding to the large subunit and the other to the small subunit (Lys-440 in the small subunit of spinach leaf and Lys-441 in that of potato tuber). The third Lys residue labeled by pyridoxal 5′-phosphate was present in the large subunit (l-I; Table I). The enzyme from Anabaena, which is composed of only one type of subunit, conserves these Lys residues in the primary structure (sites I and II; Table I).

Table I.

Sequence alignment of the regulatory sites of ADP-Glc PPases from higher plants and cyanobacteria

| Accession No. | Source | Tissue | Site | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cyanobacterial | I | II | ||

| 382 | 419 | |||

| Z11539 | Anabaena | DTIIRRAIIDKNARIG | IVVVLKNAVITDGTII | |

| M83556 | Synochocystis | GTTIRRAIIDKNARIG | IVVVIKNVTIADGTVI | |

| Small subunits | s-I | s-II | ||

| 404 | 441 | |||

| S. tuberosum | Tuber | NCHIKRAIIDKNARIG | IVTVIKDALIPSGIII | |

| x83500 | Spinacia oleracea | Leaf | NSHIKRAIIDKNARIG | IVTVIKDALIPSGTVI |

| L33648 | S. tuberosum, R. Burbank | NCHIKRAIIDKNARIG | IVTVIKDALIPSGIVI | |

| x61186 | S. tuberosum, R. Burbank | Tuber | NCHIKRAIIDKNARIG | IVTVIKDALIPSGIII |

| x55155 | S. tuberosum, Desiree | Tuber | NCHIKRAIIDKNARIG | IVTVIKDALIPSGIVI |

| x55650 | S. tuberosum, Desiree | Tuber | NCHIKRAIIDKNARIG | IVTVIKDALIPSGIVI |

| x76941 | Vicia faba (VfAGPP) | Cotyledons | NSHIRRAIIDKNARIG | IVTVIKDALIPSGTVI |

| x76940 | V. faba (VfAGPC) | Cotyledons | NSHIKRAIVDKNARIG | IVTIIKDALIPSGTVL |

| x96764 | Pisum sativum | Cotyledons | NSHIKRAIIDKNARIG | IVTVIKDALIPSGTVI |

| x96765 | P. sativum | Cotyledons | NSHIKRAIVDKNARIG | IVTIIKDALIPSGTVI |

| z79635 | Ipomoea batatas (psTL1) | Tuberous root/leaf | NSHIKRAIIDKNARIG | IVTIIKDALIPSGTII |

| Z79636 | I. batatas (psTL2) | Tuberous root/leaf | NSHIKRAIIDKNARIG | IVTVIKDALIPSGTVI |

| L41126 | Lycopersicon esculentum | Fruit | NCLYKRAIIDKNARIG | IVTVIKDALIPSGIVI |

| J04960 | Oryza sativa | Endosperm | NCHIRRAIIDKNARIG | IVTVIKDALLLAEQLYE |

| M31616 | O. sativa | Leaf | NCHIRRAIIDKNARIG | IVTVIKDALLLAEQLYE |

| X66080 | Triticum aestivum | Leaf | NSHIKRAIIDKNARIG | IVTVIKDALLPSGTVI |

| Z48562 | Hordeum vulgare | Starchy endosperm | NSHIKRAIIDKNARIG | IVTVIKDALLPSGTVI |

| Z48563 | H. vulgare | Leaf | NSHIKRAIIDKNARIG | IVTVIKDALLPSGTVI |

| Zea mays, brittle-2 | Endosperm | NSCIRRAIIDKNARIG | IVTVIKDALLPSGTVI | |

| S72425 | Z. mays | Leaf | NSHIRKAIIDKNARIG | IVTVIKDALLPSGTVI |

| Large subunits | l-I | l-II | ||

| 417 | 455 | |||

| S. tuberosum | Tuber | NTKIRKCIIDKNAKIG | IIIILEKATIRDGTVI | |

| S. oleraceaa | Leaf | ...IKDAIIDKNAR.. | ITVIFKNATIKDGVV | |

| x76136 | S. tuberosum, Desiree | Tuber | NTRIKDCIIDKNARIG | ITVISKNSTIPDGTVI |

| x61187 | S. tuberosum, R. Burbank | Tuber | NTKIRKCIIDKNAKIG | IIIILEKATIRDGTVI |

| x74982 | S. tuberosum, Desiree | Leaf | NTKIQNCIIDKNAKIG | ITVIMKNATIKDGTVI |

| u81033 | L. esculentum | NTKIRKCIIDKNAKIG | IIIISEKATIRDGTVI | |

| u88089 | L. esculentum | NTKIRKCIIDKNAKIG | IIIIAEKATIRDGTVI | |

| U81034 | L. esculentumb | NTKIQKCIIDKNAKIG | ITVIMKNATIKDGTVI | |

| x96766 | P. sativum | Cotyledons | NTKIKNCIIDKNAKIG | ITIIMEKATIEDGTVI |

| x78900 | Beta vulgaris, Zuchtlinie | Tap root | NTKIKNCIIDKNAKIG | ITIILKNATIQDGLVI |

| x14348 | T. aestivum, cv Mardler | Leaf | NTSIQNCIIDKNARIG | ITVVLKNSVIADGLVI |

| x14349 | T. aestivum | Endosperm | NTKISNCIIDMNARIG | IVVIQKNATIKDGTVV |

| z21969 | T. aestivum | Developing grain | NTKISNCIIDMNARIG | IVVIQKNATIKDGTVV |

| x14350 | T. aestivum | Endosperm | NTKISNCIIDMNARIG | IVVIQKNATIKDGTVV |

| z38111 | Z. mays | Embryo | NTKISNCIIDMNCQGW | IVVVLKNATIKDGTVI |

| s48563 | Z. mays, Shrunken-2 | Endosperm | NTKIRNCIIDMNARIG | IVVILKNATINECLVI |

| u66041 | O. sativa | Endosperm | NTKIRNCIIDMNARIG | IVVILKNATNATIKHGTVI |

| u66876 | H. vulgare | Leaf | NTSIQNCIIDKNARIG | ITVVLKNSVIADGLVI |

| x67151 | H. vulgare | Starchy endosperm | NTKISNCIIDMNARIG | IVVIQKNATIKDGTVV |

| x91736 | Chlamydomonas reinhardtii | NSVITNAIIDKNARVG | ILVIDKDALVPTGTTI | |

Sequence determined by amino acid sequencing (Ball and Preiss, 1994).

Same sequence in this region has been reported by Park and Chung (accession no. U85496).

Using chemical modification and site-directed mutagenesis techniques (Charng et al., 1994; Sheng et al., 1996), both Lys-382 and Lys-419 were shown to be involved in the activation by 3-PGA. However, no studies were performed to replace these residues on an enzyme consisting of two different subunits, which would be necessary to understand the role that each subunit plays in higher-plant enzymes. In the present study site-directed mutagenesis was used to determine whether the Lys residues of both subunits are involved in the activation by 3-PGA or the inhibition by Pi of the potato tuber ADP-Glc PPase. It was found that the effects of substitution of the Lys residues in the large and small subunit are not equivalent. Mutating Lys-404 and Lys-441 on the small subunit decreased the affinity for the activator 3-PGA and the ability of the enzyme to be inhibited by Pi. However, the effects were less pronounced when the homologous mutations were performed on the large subunit.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents

32PPi was purchased from DuPont-New England Nuclear. [14C]Glc-l-P was from ICN Pharmaceuticals. [α-35S]dATP was from Amersham. Oligonucleotides were synthesized and purified by the Macromolecular Facility at Michigan State University (East Lansing). Restriction enzymes were from New England Biolabs. All other reagents were of the highest quality available.

Bacterial Strains and Media

Escherichia coli strain TG1 (K12, Δ[lac-pro], supE, thi, hsdD5/F'traD36, proA+B+, lacIq, lacZΔM15) was used for site-directed mutagenesis and grown in 2× YT medium (Sambrook et al., 1989). E. coli mutant strain AC70R1-504, which is deficient in ADP-Glc PPase activity, was used for expression of the wild-type and mutant enzymes described in this work. For the preparation of plasmids pMON17336 and pMLaugh10, AC70R1-504 was grown in Luria-Bertani medium (Sambrook et al., 1989) in the presence of kanamycin (25 μg/mL) or spectinomycin (70 μg/mL), respectively.

Plasmids and Phages

Plasmid pMLaugh10 is a vector used for the expression of an insert that encodes the small subunit of ADP-Glc PPase from potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) tubers. pMON17336 is another expression vector, compatible with pMLaugh10, that contains an insert that encodes the large subunit. The construction of both plasmids was described previously (Iglesias et al., 1993; Ballicora et al., 1995). Phages M13 mp18 and M13 mp19, derivatives of M13, were used for the preparation of single-stranded DNA (Messing, 1983).

Site-Directed Mutagenesis

Site-directed mutagenesis was performed using a previously published procedure (Sayers et al., 1988) and an in vitro mutagenesis kit (Sculptor, Amersham). Because this method requires a single-stranded DNA template, target genes were subcloned to vectors capable of producing it. For that purpose, phages M13 mp18 and M13 mp19 were used as follows: Plasmid pMON17336 was digested with XbaI, and the fragment that contained the gene of the large subunit was subcloned onto M13 mp19, whereas pMLaugh10 was digested with EcoRI and the fragment that encoded the small subunit was subcloned onto M13 mp18. Single-stranded DNA was prepared from these phages to proceed with the site-directed mutagenesis (Sayers et al., 1988). The oligonucleotides used to perform the mutations are shown in Figure 1. Once the mutations were confirmed by dideoxy sequencing (Sanger et al., 1977), replicative forms (double-stranded DNA) of the phages were prepared and digested with the restriction enzyme used to introduce the fragment. Those fragments were returned to the original vectors, pMON17336 and pMLaugh10, respectively. To verify that there were no unintended mutations, the entire coding regions of these mutated plasmids were sequenced. The plasmids with the desired mutations were used to transform AC70R1-504 cells for expression.

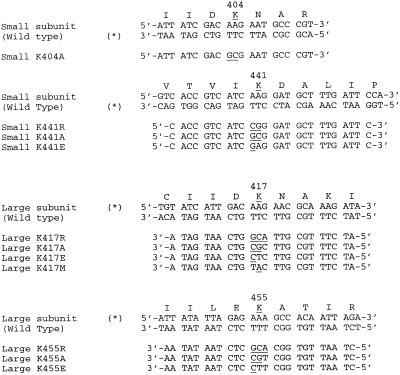

Figure 1.

Synthetic oligonucleotides used for site-directed mutagenesis. Underlined nucleotides denote differences from the wild-type sequence. Asterisks indicate strands produced from the phage (M13 mp18 and M13 mp19 for the small and large subunit genes, respectively) and used as templates on the mutagenesis protocol.

Expression and Purification of Wild-Type and Mutant Enzymes

Wild-type and mutant genes were expressed in AC70R1-504 cells to obtain heterotetrameric or homotetrameric enzymes, as described previously (Ballicora et al., 1995) with only one modification. The concentration of isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside was increased from 0.01 to 0.5 mm in the induction. To express the mutants, cells were transformed with the mutated plasmids pMON17336 or pMLaugh10.

The enzymes were purified as indicated previously with the following modifications. After the heat treatment step, a precipitation step was introduced in which ammonium sulfate was added to the extract until 30% saturation was reached. After centrifugation for 15 min at 15,000g, the supernatant was taken to 60% saturation and centrifuged for 20 min at 15,000g. This pellet was dissolved in a minimal amount of buffer A (Ballicora et al., 1995) and desalted against the same buffer using Econo-Pac 10DG columns (Bio-Rad). All of these steps were performed at 4°C. Another modification was at the hydrophobic chromatography step, in which ammonium sulfate was used instead of potassium phosphate buffer. Other steps remained unchanged and, unless indicated otherwise, all mutant enzymes reached >90% purity.

Assay of ADP-Glc PPase

Assay A: Pyrophosphorolysis Direction

Pyrophosphorolysis of ADP-Glc was determined by the formation of [32P]ATP from 32PPi. Unless indicated otherwise, the reaction mixture contained 20 μmol of Gly-Gly buffer, pH 8.0, 1.75 μmol of MgCl2, 0.75 μmol of DTT, 2.5 μmol of NaF, 0.5 μmol of ADP-Glc, 0.38 μmol of 32PPi (0.5 × 106 cpm μmol−1 to 2.0 × 106 cpm μmol−1), 50 μg of crystalline BSA, and variable concentrations of 3-PGA in a final volume of 0.25 mL. The reaction was started by the addition of enzyme and after a 10-min incubation at 37°C was terminated by the addition of 3 mL of cold 5% TCA. The [32P]ATP formed was measured as described previously (Morell et al., 1987). Inhibition by Pi was measured by the addition of potassium phosphate, pH 8.0, to the reaction mixture.

Assay B: Synthesis Direction

Synthesis of ADP-Glc was followed by the formation of [14C]ADP-Glc from [14C]Glc-1-P. Reaction mixtures contained (in 0.2 mL): 20 μmol of Hepes buffer, pH 8.0, 1 μmol of MgCl2, 0.6 μmol of DTT, 0.1 μmol of [14C]Glc-1-P (1.0 × 106 cpm μmol−1), 0.3 μmol of ATP, 0.3 unit of inorganic pyrophosphatase, and 40 μg of crystalline BSA. 3-PGA was added at different concentrations as indicated. Assays were initiated by addition of the enzyme. Reaction mixtures were incubated for 10 min at 37°C and terminated by heating in a boiling-water bath for 1 min. [14C]ADP-Glc was assayed as described previously (Ghosh and Preiss, 1966). In both assays A and B, 1 unit is defined as the amount of enzyme that produces 1 μmol of product in 1 min. For assay of the mutant enzymes, the reaction conditions were identical to the wild type except that the amount of 3-PGA was altered to obtain maximal activity.

Protein Assay

Protein concentration was determined using bicinchoninic acid reagent (Smith et al., 1985) (Pierce) with BSA as the standard.

Kinetic Characterization

Kinetic data were plotted as velocity versus substrate or effector concentration. Kinetic constants were obtained from Hill plots and were confirmed through nonlinear least-squares fitting of the data with the Hill's equation or the Michaelis-Menten equation for hyperbolic plots (Fraser and Suzuki, 1973).

Kinetic constants were expressed as A0.5, S0.5, and I0.5, which correspond to the concentration of effector necessary to reach 50% of maximal activation, velocity, and inhibition, respectively. The -fold activation was the ratio between the maximal activity obtained at saturating concentrations of activator and the activity in the absence of it.

RESULTS

Effect of the Mutations on the Pyrophosphorolysis Direction

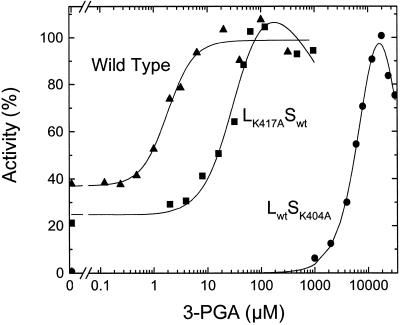

Using partially purified enzymes, it has been reported that in the presence of the large subunit from potato tubers, the small subunit has a higher affinity for the activator 3-PGA in both the synthesis and pyrophosphorolysis directions (Ballicora et al., 1995). In the present study using proteins purified to homogeneity, we observed that the homotetramer composed of only the small subunit (S4) and the heterotetramer (L2S2) had similar specific activities at saturated concentrations of 3-PGA in the pyrophosphorolysis reaction. They were 55 and 48 units mg−1, and the A0.5 for 3-PGA was 900 and 2.2 μm, respectively (Table II). Figure 2 shows representative activation curves for the wild-type and LK417ASwt ADP-Glc PPases. In addition to the affinity for the activator, another difference was noted: When the activity was analyzed in the absence of 3-PGA, the activity of the small subunit alone was negligible; when it was expressed in the presence of the large subunit, the activity in the absence of activator was 13.3 units mg−1, which is only 3.6-fold lower than the maximal activity at saturated concentrations of 3-PGA (Table II). Because the presence of the large subunit in the quaternary structure is so important in allosteric activation, it was of interest to determine the effect of mutations on the putative allosteric sites of that subunit.

Table II.

Activation by 3-PGA in the pyrophosphorolysis reaction

E. coli AC70R1-504 cells were cotransformed with two plasmids. Plasmid pMON17336 encodes either the wild-type (wt) large subunit of the potato tuber ADP-Glc PPase or a mutated large subunit. The other plasmid (pMLaugh10) encodes either the wild-type small subunit or a single amino acid mutant. Enzymes were expressed and purified as described in Methods. Specific activities of the mutants were determined at saturating concentrations of activator (3-PGA) and substrates. Every constant was determined at least twice and the difference was <10% of the average in all cases. Average values are shown.

| Subunit

|

A0.5

|

Specific Activity | Activationa | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pMON17336 (Large) | pMLaugh10 (Small) | 3-PGA | Ratio mutant/wt | |||

| μm | units mg−1 | −fold | ||||

| wt | 900 | 55 | >500 | |||

| wt | + | wt | 2.2 | 1 | 48 | 3.6 |

| K455A | + | wt | 6 | 3 | 47 | 6 |

| K455E | + | wt | 10 | 5 | 51 | 50 |

| K417A | + | wt | 20 | 9 | 13 | 22 |

| K417E | + | wt | 27 | 12 | 14 | 18 |

| wt | + | K441A | 120 | 54 | 32 | 2.9 |

| wt | + | K441E | 420 | 191 | 39 | 3.1 |

| wt | + | K404A | 6800 | 3090 | 12 | 130 |

| K417A | + | K441A | 390 | 177 | 7 | 80 |

| K417E | + | K441E | 6500 | 2955 | 5b | 96 |

Ratio between the activity at saturated concentrations and in the absence of 3-PGA. In the case of the wild-type small subunit, the activity in the absence of activator was negligible even when 0.5 μg of purified enzyme was added in the reaction mixture.

Specific activity is estimated to be higher because the purity was about 40%. One unit is defined as 1 μmol of ATP formed in 1 min.

Figure 2.

The effect of 3-PGA concentration on ADP-Glc PPase activity in the pyrophosphorolysis direction. For the wild-type enzyme and the mutants LK417ASwt and LwtSK404A, 100% activity represents 42, 12, and 5.2 μmol of ATP produced min−1 mg−1, respectively.

When the Lys-455 on the large subunit was mutated, the apparent affinity for 3-PGA decreased. The A0.5 values were 3- and 5-fold higher when the residue was replaced by Ala and Glu, respectively. Greater changes were observed when large-subunit Lys-417 was mutated. In this case, the A0.5 values were 9- and 12-fold higher when the residue was replaced by Ala or Glu, respectively (Table II). The catalytic ability of the enzyme was not affected dramatically by these four mutations. However, a greater reduction was observed when the activity was assayed in the absence of 3-PGA. For that reason, the activation increased from 3.6 (wild type) to 6, 22, 18, and 50 for the mutations K455A, K417A, K417E, and K455E, respectively (Table II). Even though these mutated large subunits produced heterotetrameric enzymes with lower affinity for the activator than the heterotetrameric wild type, the mutated large subunits still had the ability to increase the apparent affinity of 3-PGA for the small subunit when both subunits were expressed together.

When the wild-type small subunit was expressed along with the mutated large subunits K455A, K455E, K417A, and K417E, the A0.5 for 3-PGA was reduced from 900 μm to 6, 10, 20, and 27 μm, respectively (Table II).

Mutations of the homologous residues on the small subunit were performed to determine whether they are more relevant than their equivalent residues on the large subunit to the activation of the enzyme. When Lys-441 was replaced with Ala or Glu, the A0.5 for 3-PGA increased 54- and 191-fold, respectively. However, the specific activities at saturated concentrations of activator were not much different than those of the wild type: 32 units mg−1 for the Ala and 39 units mg−1 for the Glu mutant. The activity of these mutants in the absence of 3-PGA did not change much. For that reason, the maximal activation remained at 2.9 for the Ala and 3.1 for the Glu mutant (Table II). The greatest decrease in apparent affinity was obtained when Lys-404 on the small subunit was replaced by Ala. The A0.5 for 3-PGA was 6800 μm, which represents a 3090-fold increase over the wild type (Table II; Fig. 2). Despite this mutant being severely affected in its allosteric properties, the maximal specific activity was 12 units mg−1, only 4 times lower than the wild type. Conversely, the pyrophosphorolysis activity was very dependent on the allosteric activator, as shown by the fact that 3-PGA activated the K404A-mutated enzyme 130-fold (Table II).

Two double mutants were prepared by cotransforming with plasmids that encoded subunits with a single mutation. These double mutants had a remarkable effect on the activation properties. Not only were the A0.5 values for 3-PGA of the LK417ASK441A and LK417ESK441E enzymes much higher than that of the wild type, but they were also higher than the A0.5 of each single mutant. Moreover, the effects of these mutations seemed to be additive. The A0.5 for 3-PGA of LK417ASK441A was 177-fold higher than that of the wild type, which is close to the value that would be expected (162-fold) if the LK417A mutation increased 3-fold and the SK441A mutation contributed with a 54-fold increase, as occurred when each single mutant was analyzed (Table II). At the same time, the A0.5 for 3-PGA of LK417ESK441E was 2955 times higher than that of the wild type. If each mutation contributed to the same extent that they did in the single mutants (5- and 191-fold increase of the A0.5 for 3-PGA), an increase of 955-fold would be expected. The effect observed with the double mutant was higher but in the same range.

There was a common property between the double and the single mutants on the LK417 site that has not been observed with the mutations on the SK441 residue. Because the activities in the absence of 3-PGA decreased significantly, the activation by 3-PGA was very high for both the LK417ASK441A and LK417ESK441E mutants: 80- and 96-fold, respectively (Table II). A role in catalytic efficiency can be ruled out for these residues (LK417 and SK441). The specific activities of the double mutants were lower than those of the wild type; however, this decrease is not significant compared with the effect on the apparent affinity for the activator (Table II).

Effect of the Mutations on the Inhibition by Pi

It has been shown for spinach leaf ADP-Glc PPase that the activation and the inhibition are structurally related. Two Lys residues were protected by both 3-PGA and Pi against chemical modification by pyridoxal 5-phosphate (Ball and Preiss 1994). In the present study the mutations performed on the ADP-Glc PPase from potato tubers yielded enzyme forms with altered activation properties. Therefore, it was of interest to determine whether the inhibition by Pi was also altered. For this purpose, the mutants were analyzed in the pyrophosphorolysis direction because the activities were measurable even in the absence of the activator 3-PGA. Furthermore, in this direction all of the mutants were activated by 3-PGA, so inhibition studies could be performed not only in the presence but also in the absence of the activator.

To measure inhibition in the absence of activator, the activity was analyzed in the absence of 3-PGA at different concentrations of Pi for determination of the I0.5. None of the mutations performed in the large subunit decreased the affinity for the inhibitor Pi. On the contrary, those mutants were equally or more sensitive to Pi inhibition than the wild type. The I0.5 for the wild type was 74 μm, whereas the I0.5 of the mutants K455A, K455E, K417A, and K417E was 19, 20, 76, and 22 μm, respectively (Table III). Conversely, when Lys-441 and Lys-404 on the small subunit were replaced, mutants became virtually insensitive to Pi inhibition. The I0.5 of all mutants, K441A, K441E, and K404A, was more than 200-fold higher than that of the wild type (Table III). These results suggest that the Lys-441 and Lys-404 residues of the small subunit are important for inhibition by Pi, whereas Lys-417 and Lys-455 of the large subunit play little or no role. To confirm this, the effect of Pi in presence of the activator 3-PGA was also studied.

Table III.

Inhibition of the ADP-Glc PPase mutants by phosphate in the pyrophosphorolysis direction

E. coli AC70R1-504 cells were cotransformed with two plasmids. Plasmid pMON17336 encodes either the wild-type (wt) large subunit of the potato tuber ADP-Glc PPase or a mutated large subunit. The other plasmid (pMLaugh10) encodes either the wild-type small subunit or a single amino acid mutant. Enzymes were expressed and purified as described in Methods. The substrates and cofactors were 2 mm ADPGlc, 1.5 mm PPi, and 7 mm Mg2+. The I0.5 of Pi was determined as described in Methods. Every constant was determined at least twice and the difference was <10% of the average in all cases. Average values are shown. The 3-PGA activation curve was performed in presence of 0.5 mm phosphate.

| Subunit

|

I0.5

|

A0.5

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pMON17336 (Large) | pMLaugh10 (Small) | Phosphate | Ratio mutant/wt | 3-PGA activation +0.5 mm Pi | Ratio +Pi/−Pia | |

| μm | μm | |||||

| wt | + | wt | 74 | 1.0 | 56 | 25 |

| K455A | + | wt | 19 | 0.25 | 160 | 27 |

| K455E | + | wt | 20 | 0.25 | 280 | 28 |

| K417A | + | wt | 76 | 1.0 | 400 | 20 |

| K417E | + | wt | 22 | 0.3 | 600 | 22 |

| wt | + | K441A | 32,000 | 432 | 240 | 2.0 |

| wt | + | K441E | 16,000 | 216 | 800 | 1.9 |

| wt | + | K404A | 48,000 | 650 | 8000 | 1.2 |

To determine the ratio A0.5(+Pi)/A0.5(−Pi), the A0.5 value in the absence of Pi was taken from Table II.

Pi can reverse the activation caused by 3-PGA and vice versa. Therefore, Pi in the reaction mixture shifts the 3-PGA activation curve toward higher concentrations, thus increasing the A0.5. To study this effect, an activation curve was performed for each mutant in the presence of 0.5 mm Pi. The resultant A0.5 was then compared with that determined in the absence of inhibitor (Table III). When the wild-type enzyme was analyzed, 0.5 mm Pi increased the A0.5 for 3-PGA 25-fold. All of the mutations performed in the large subunit produced enzymes that showed similar results. Pi increased the A0.5 for 3-PGA by 27-, 28-, 20-, and 22-fold for the mutants K455A, K455E, K417A, and K417E, respectively. Conversely, none of the mutations performed on the small subunit, K441A, K441E, and K404A, exhibited the same effect. Activation curves in the presence or absence of Pi were very similar. The A0.5 values were little affected, increasing only 2-, 1.9-, and 1.2-fold for the mutants K441A, K441E, and K404A, respectively (Table III).

Effect of the Mutations on the Kinetic Constants and Stability

The allosteric properties were altered when Lys-417, Lys-455 (large subunit), Lys-404, and Lys-441 (small subunit) were replaced by either Ala or Glu. To confirm that these residues were specifically involved in the regulation of the enzyme, kinetic characteristics of the substrates were determined to see if they were altered. The affinities for Mg2+ and PPi did not change dramatically in any of the mutants tested. The S0.5 for Mg2+ remained between 2.6 and 4.2 mm, and the Km for PPi did not increase more than 2-fold for any of the mutants relative to the wild type (Table IV). The apparent affinity for ADP-Glc did not change for most of the mutants. Double-mutant LK417ESK441E and single-mutant LwtSK404A had Km values of 0.60 and 0.90 mm, respectively, for ADP-Glc (Table IV). These parameters were 2.7- and 4.1-fold higher than those of the wild type. However, these changes are small compared with the striking changes in allosteric properties observed for these two mutants (Tables II and III).

Table IV.

Pyrophosphorolysis of ADP-Glc: kinetic constants of substrates and cofactors

E. coli AC70R1-504 cells were cotransformed with two plasmids. Plasmid pMON17336 encodes either the wild-type (wt) large subunit of the potato tuber ADP-Glc PPase or a mutated large subunit. The other plasmid (pMLaugh10) encodes either the wild-type small subunit or a single amino acid mutant. Enzymes were expressed and purified as described in Methods. The concentration of 3-PGA used was 10 mm. In the case of mutants LwtSK404A and LK417ES441E the concentration was 20 mm. The concentration of ADP-Glc, PPi, and Mg2+ were as described in Methods. Every constant was determined at least twice and the difference was <10% of the average in all cases. Average values are shown.

| Subunit

|

S0.5 Mg2+ | Km PPi | Km ADP-Glc | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Large | Small | ||||

| mm | |||||

| wt | + | wt | 2.6 | 0.065 | 0.22 |

| K417A | + | wt | 2.9 | 0.070 | 0.22 |

| K417E | + | wt | 3.3 | 0.075 | 0.26 |

| K455A | + | wt | 4.2 | 0.040 | 0.30 |

| K455E | + | wt | 4.2 | 0.070 | 0.30 |

| wt | + | K441A | 3.5 | 0.060 | 0.20 |

| wt | + | K441E | 2.7 | 0.060 | 0.26 |

| wt | + | K404A | 3.1 | 0.120 | 0.90 |

| K417A | + | K441A | 2.8 | 0.050 | 0.34 |

| K417E | + | K441E | 2.8 | 0.050 | 0.60 |

These results suggest that the mutations had little if any effect on the catalytic site and that they specifically altered the regulatory properties. Furthermore, like the wild type, all of these mutants were stable (>70% recovery) to a treatment at 60°C for 5 min (data not shown). This was used as a first purification step in all cases and indicates that the Lys residues under study are not necessary for the stability of the enzyme structure.

Effect of the Mutations on the Synthesis Direction

The large subunit has the ability to reduce the A0.5 for 3-PGA when expressed along with the small subunit. That effect is more marked in the pyrophosphorolysis direction, so changes in the affinity for the activator were easier to detect. However, the activation in the reaction of synthesis was also studied because this is the direction of the reaction in vivo in the pathway of the starch biosynthesis.

When Lys-455 on the large subunit was mutated to Ala or Glu, the A0.5 for 3-PGA increased 2- and 8-fold, respectively. Greater increases in A0.5 were obtained by mutating Lys-417 on the large subunit. The A0.5 of mutants K417A and K417E were 3 and 13 times higher than that of the wild type (Table V), indicating that replacing these residues affected the activation of the enzyme. However, all of these mutants on the large subunit had an A0.5 for 3-PGA lower than the A0.5 of the small subunit expressed alone (Table V). As it was observed in the pyrophosphorolysis direction, mutations on the small subunit caused a bigger decrease in the apparent affinity for the activator. Mutants K441A and K441E had A0.5 values for 3-PGA 32 and 83 times higher, respectively, than that of the wild type. At the same time, mutant K404 could not be activated by 3-PGA, even by increasing the concentration up to 50 mm.

Table V.

Activation by 3-PGA of the synthesis of ADP-Glc

E. coli AC70R1-504 cells were cotransformed with two plasmids. Plasmid pMON17336 encodes either the wild-type (wt) large subunit of the potato tuber ADP-Glc PPase or a mutated large subunit. The other plasmids (pMLaugh10) encodes either the wild-type small subunit or a single amino acid mutant. Enzymes were expressed and purified as described in Methods. Specific activities of the mutants were determined at saturated concentrations of activator (3-PGA) and substrates (1.5 mm ATP, 0.5 mm Glc-1-P, 7 mm Mg2+). In the case of mutants LwtSK404A and LK417ES441E, concentrations of substrates were increased four times but still no activation was observed. Every constant was determined at least twice and the difference was <10% of the average in all cases. Average values are shown. Inhibition has been observed at higher concentrations of 3-PGA.

| Subunit

|

A0.5

|

Specific Activity | Activationa | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pMON17336 (Large) | pMLaugh10 (Small) | 3-PGA | Ratio mutant/wt | |||

| mm | units mg−1 | −fold | ||||

| wt | 3.5 | 32 | >100 | |||

| wt | + | wt | 0.10 | 1 | 30 | 30 |

| K455A | + | wt | 0.22 | 2 | 22 | >100 |

| K455E | + | wt | 0.77 | 8 | 16 | >100 |

| K417A | + | wt | 0.30 | 3 | 11 | 25 |

| K417E | + | wt | 1.30 | 13 | 5 | >30 |

| wt | + | K441A | 3.2 | 32 | 16 | >30 |

| wt | + | K441E | 8.3 | 83 | 3 | >30 |

| wt | + | K404A | No activation | 0.26 | None | |

| K417A | + | K441A | 6.0 | 60 | 9 | 31 |

| K417E | + | K441E | No activation | 0.14b | None | |

Ratio between the activity at saturated concentrations and in the absence of 3-PGA.

In this case, specific activity was determined in the absence of 3-PGA. On the other hand, specific activity is estimated to be higher because the purity reached was about 40%. One unit is defined as 1 μmol of ATP formed in 1 min.

Double mutants also showed that the effects of the mutations were at least additive. The A0.5 for 3-PGA of LK417ASK441A was 6.0 mm, which is 60 times higher than that of the wild type. This is in the range of what is expected if one mutation contributes with an increase of 3-fold and another of 32-fold, as they do when the single mutants are analyzed. The A0.5 of LK417ESK441E could not be measured because the enzyme was not activated by 3-PGA, even up to 50 mm. At the highest concentrations assayed, 3-PGA partially inhibited LK417ESK441E (data not shown). In this double mutant, if both Glu mutations contribute similarly, as they do in the single mutants (with increases of 13- and 83-fold; Table V), an A0.5 of approximately 100 mm would have been expected. At such high concentrations, it is possible that 3-PGA also interacts nonspecifically with other sites of the enzyme, causing inhibition.

Characterization of the LK417MSwt Mutant

The residue Lys-417 in the potato tuber ADP-Glc PPase is highly conserved among the large subunits from plant enzymes. However, there are some exceptions (Table I). Because this residue could be involved in the regulation of the enzyme, a question arose about how relevant a change would be in the allosteric properties. As has been shown on the mutant LK417ASwt at this position, a change from a positively charged to a neutral amino acid showed a significant but small effect on the activation by 3-PGA and no effect on the inhibition by Pi. Therefore, some substitutions at this position could still give an enzyme with the ability to be regulated allosterically in vivo. To test this postulate, since some enzymes have a Met at this position (Table I), Lys-417 of the large subunit from potato tubers was mutated to Met and the regulatory properties were analyzed (Table VI). LK417MSwt was activated by 3-PGA in the pyrophosphorolysis and synthesis directions in a manner similar to that of the Ala mutant.

Table VI.

Regulatory properties of the mutant LK417MSwt

| Kinetic Constant | Reaction

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Pyrophosphorolysis | Synthesis | |

| Specific activity | 45 units mg−1 | 12 units mg−1 |

| 3-PGA activation | 14-fold | >100-fold |

| A0.5 3-PGA (−Pi) | 7 μm | 450 μm |

| A0.5 Ratio mutant/wt | 3.5 | 4.5 |

| A0.5 3-PGA (+0.5 mm Pi) | 198 μm | — |

| A0.5 Ratio +Pi/−Pi | 28 | — |

| I0.5 Pi | 20 μm | — |

The mutant LK417MSwt was expressed, purified, and the kinetic parameters determined as described in Methods. The substrates and cofactors were 2 mm ADP-Glc, 1.5 mm PPi, and 7 mm Mg2+ in the pyrophosphorolysis direction, and 1.5 mm ATP, 0.5 mm Glc-1-P, and 7 mm Mg2+ in the synthesis direction. The results are the average of two independent experiments and the difference between them was less than 10% in all cases.

In the synthesis direction the A0.5 was 450 μm, and in the pyrophosphorolysis direction it was 7 μm; these values are only 4.5 and 3.2 times higher, respectively, than those of the wild type. At the same time, specific activities did not change dramatically. In the pyrophosphorolysis direction it was 45 units mg−1, and in the synthesis direction it was 12 units mg−1. The inhibition by Pi was not altered significantly. The sensitivity toward Pi in the absence of activator increased from 74 to 20 μm, but the ability to shift the 3-PGA activation curve remained the same. In the presence of 0.5 mm Pi the A0.5 for 3-PGA in the pyrophosphorolysis direction increased 28-fold. Under the same conditions, the wild-type enzyme showed an increase of 25-fold. The most altered characteristic between LK417MSwt and the wild type was that the activation in the pyrophosphorolysis direction increased from 3.6 to 14 because the enzyme was lower in activity in the absence of the activator. This alteration may have very little physiological effect.

DISCUSSION

The allosteric regulation of the ADP-Glc PPase has always been an important topic because this enzyme catalyzes a key step in the pathway of the synthesis of glycogen in bacteria and starch in plants (Preiss 1984, 1988, 1991, 1997a, 1997b). To study the different roles of these sites on a heterotetrameric enzyme, in the current study site-directed mutagenesis was performed on the homologous Lys residues of the potato tuber ADP-Glc PPase, which has been cloned and expressed in E. coli cells.

Lys residues (Lys-417 and Lys-455 of the large subunit and Lys-441 of the small subunit) were mutated conservatively to Arg. However, very little change was observed on the affinity for the activator. The A0.5 for 3-PGA in the synthesis direction did not increase more than 2-fold (data not shown). Therefore, to study the different roles that these residues may play in the large and small subunits, Ala (neutral) and Glu (negatively charged) mutations were performed. The mutant enzymes obtained were expressed, purified, and characterized kinetically. Much greater effects on the affinity for activator were found when the Lys residues were replaced by Ala and Glu. The A0.5 for 3-PGA of these mutants increased up to 8.3 mm (83-fold higher than in the wild type) when Lys-441 on the small subunit was mutated to Glu (Table V). This indicated that the most important characteristic of these Lys residues is the positive charge that probably interacts with the negative charge of the phosphate and/or carboxyl groups of the 3-PGA.

At the same time, replacing the Lys-404 on the small subunit (homologous to Lys-417 of the large subunit) with Ala was enough to make this mutant insensitive to the activation in the synthesis direction. When the pyrophosphorolysis reaction was analyzed, this mutant had an A0.5 that was 3090-fold higher than that of the wild type. The other mutants also had lower affinities for 3-PGA, but even so, the kinetic constants for the substrates ADP-Glc, PPi, and the cofactor Mg2+ did not change significantly (Tables II and IV). The most significant difference between these mutants was that mutations on the small subunit showed a much lower affinity for 3-PGA than the mutations on the large subunit (Tables II and V). Thus, both of these sites in the small subunit appear to be more important for regulation than the homologous Lys residues in the large subunit.

It has been thought that the large subunit plays the most important role in the regulation because its presence in the heterotetramer increases the affinity for the activator 3-PGA (Ballicora et al., 1995). One of the possibilities that was considered was that the large subunit provides a regulatory site with higher affinity. However, performing mutations in the large subunit of the putative amino acids involved in the binding of the activator did not support this idea. These large-subunit mutants still increased the affinity for 3-PGA when they were combined with the wild-type small subunit. This effect was observed whether the reaction was in the synthesis or the pyrophosphorolysis direction (Tables II and V). Thus, the large subunit of the potato tuber ADP-Glc PPase increases the affinity for the activator, but the integrity of its own regulatory-site residues is not necessary to see this effect.

Furthermore, mutations on the homologous sites on the small subunit showed larger effects on the regulation of the enzyme. All of this suggests that the role of the large subunit is to modulate the regulatory properties of the small subunit rather than to provide a more efficient allosteric site for activation. The small subunit has not only a functional catalytic site but also a functional yet relatively inefficient regulatory site (with a low affinity for the activator). In the presence of the large subunit, this site in the small subunit is more efficient as an activator.

The inhibition by Pi showed a very clear difference between the residues on the small and large subunits. When Lys-441 and Lys-404 on the small subunit were mutated to either Ala or Glu, the inhibition by Pi in the absence of the activator almost disappeared. The I0.5 increased more than 2 orders of magnitude (Table III). These mutants also lost the ability to shift the activation curve by the presence of inhibitor. Thus, Pi cannot effectively compete with the activator. Nevertheless, when the mutations were performed on the large subunit the effect was very different. None of the mutants on the Lys-417 or the Lys-455 could increase the I0.5 for Pi in absence of 3-PGA. In these mutants Pi shifted the activation curve to the same extent as in the wild type (Table III). Therefore, Lys-404 (site s-I) and Lys-441 (site s-II) are important for inhibition by Pi. The homologous sites on the large subunit do not seem to have the same role. It is interesting that in the spinach leaf enzyme Pi can prevent the binding of pyridoxal 5-P to the large subunit site (l-I) (Ball and Preiss, 1994). This can be explained by Pi binding and partially blocking the access of the activator or chemical analog (pyridoxal 5-P) to that residue. Recently, another Pi-binding site was found on the enzyme from Anabaena (Sheng and Preiss, 1997). Because this enzyme is a homotetramer, it would be interesting to know if this residue plays a different role in the large or small subunit of the heterotetrameric higher-plant enzyme.

The results obtained in the present study strongly suggest that the different subunits have an asymmetric regulatory function in the heterotetrameric ADP-Glc PPase. Previously, it has been suggested that they have different roles in catalysis. The small subunit seemed to have all of the catalytic activity of the heterotetramer, because the large subunit expressed alone did not show ADP-Glc PPase activity (Iglesias et al., 1993; Ballicora et al., 1995). Site-directed mutagenesis experiments on the Glc-1-P site confirmed the idea that the role of the large subunit on catalysis is minimal (Fu et al., 1998). We propose that the main role of the large subunit is to interact with the small subunit and modulate the properties of the activator site. The structure of the putative activator sites in the large subunit would not be as important as the overall interaction of the large subunit that allows the small subunit to increase its affinity for the activator. This effect could be the result of an induced conformational change or a direct interaction between regulatory sites. This hypothesis explains why the Lys residues identified as part of the activator site showed a higher conservation in the small subunit than in the large subunit of the plant enzymes sequenced so far. The only time that the Lys residue of the site s-I was not conserved was in a clone from sugar beet that had a deletion of 12 amino acids in that region. However, this clone has not been expressed to determine if it has any activity and it was used only as a probe in blot experiments (Muller-Röber et al., 1995). Another exception is a PCR product from Arabidopsis. However, the alteration occurs in the region where degenerate primers were used (Villand et al., 1993). Another clone of the small subunit of the enzyme from Arabidopsis leaves has been isolated and the Lys at site s-I is conserved (B. Smith-White, unpublished results).

It has been suggested that Lys-417 (site l-I, Table I) in the large subunit is not conserved and may provide different grades of activation for 3-PGA to different ADP-Glc PPases from different sources (Martin and Smith, 1995). However, a change in this residue can explain only slight decreases in affinity for the 3-PGA. Mutating Lys-417 to Met, a residue that is present in this position in some enzymes, showed little change in the regulatory properties (Table V). Thus, enzymes bearing a Met instead of a Lys at this position can still have all of the properties needed to regulate the synthesis of starch in vivo. If an ADP-Glc PPase from a higher plant does not show the classic regulation by 3-PGA and Pi, it is not because there is a Met in this site, so other structural reasons have to be found.

We have shown that the Lys residues on the small subunit were more important than the respective homologous residues in the large subunit. Still, some variations could exist in the relative importance of these two sites in the small subunit. In the potato tuber ADP-Glc PPase, site s-I (Lys-404 of the small subunit) seems to be more important than site s-II (Lys-441 of the small subunit). In other enzymes the opposite effect cannot be discounted. For instance, in the spinach leaf enzyme, site s-I is not labeled by pyridoxal 5-P (Ball and Preiss, 1994). This could be attributable to s-II being more important for regulation than s-I or because pyridoxal 5-P does not bind for steric reasons. For instance, when Lys-419 (homologous to s-II and l-II) in the enzyme from Anabaena was mutated, Lys-382 (homologous to s-I and l-I) became the preferred site for labeling (Charng et al., 1994).

Abbreviations:

- 3-PGA

3-phosphoglycerate

- PPase

pyrophosphorylase

Footnotes

This work was supported in part by Department of Energy grant no. DE-FG02-93ER20121.

LITERATURE CITED

- Ball K, Preiss J. Allosteric sites of the large subunit of the spinach leaf ADPglucose pyrophosphorylase. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:24706–24711. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballicora MA, Laughlin MJ, Fu Y, Okita TW, Barry GF, Preiss J. Adenosine 5′-diphosphate-glucose pyrophosphorylase from potato tuber. Significance of the N terminus of the small subunit for catalytic properties and heat stability. Plant Physiol. 1995;109:245–251. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.1.245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charng Y, Iglesias AA, Preiss J. Structure-function relationships of cyanobacterial ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase: site-directed mutagenesis and chemical modification of the activator-binding sites of ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase from Anabaena PCC 7120. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:24107–24113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser RDB, Suzuki E (1973) The use of least squares in data analysis. In SJ Leach, ed, Physical Principles and Techniques in Protein Chemistry, Part C. Academic Press, New York, pp 301–355

- Fu Y, Ballicora MA, Preiss J. Mutagenesis of the glucose-1-phosphate binding site of potato tuber ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase. Plant Physiol. 1998;117:989–996. doi: 10.1104/pp.117.3.989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh HP, Preiss J. Adenosine diphosphate glucose pyrophosphorylase: a regulatory enzyme in the biosynthesis of starch in spinach chloroplasts. J Biol Chem. 1966;241:4491–4504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iglesias AA, Barry GF, Meyer C, Bloksberg L, Nakata PA, Greene T, Laughlin MJ, Okita TW, Kishore GM, Preiss J. Expression of the potato tuber ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:1081–1086. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iglesias AA, Kakefuda G, Preiss J. Regulatory and structural properties of the cyanobacterial ADPglucose pyrophosphorylase. Plant Physiol. 1991;97:1187–1195. doi: 10.1104/pp.97.3.1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakefuda G, Charng YY, Iglesias AA, McIntosh L, Preiss J. Molecular cloning and sequencing of ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase from Synechocystis PCC 6803. Plant Physiol. 1992;99:259–261. doi: 10.1104/pp.99.1.359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin C, Smith AM. Starch biosynthesis. Plant Cell. 1995;7:971–985. doi: 10.1105/tpc.7.7.971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messing J. New M13 vectors for cloning. Methods Enzymol. 1983;101:20–78. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(83)01005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morell MK, Bloom M, Knowles V, Preiss J. Subunit structure of spinach leaf ADPglucose pyrophosphorylase. Plant Physiol. 1987;85:182–187. doi: 10.1104/pp.85.1.182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller-Röber B, Nast G, Willmitzer L. Isolation and expression analysis of cDNA clones encoding a small and a large subunit of ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase from sugar beet. Plant Mol Biol. 1995;27:191–197. doi: 10.1007/BF00019190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakata PA, Greene TW, Anderson JM, Smith-White BJ, Okita TW, Preiss J. Comparison of the primary sequences of two potato tuber ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase subunits. Plant Mol Biol. 1991;17:1089–1093. doi: 10.1007/BF00037149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okita TW, Nakata PA, Anderson JM, Sowokinos J, Morell M, Preiss J. The subunit structure of potato tuber ADPglucose pyrophosphorylase. Plant Physiol. 1990;93:785–790. doi: 10.1104/pp.93.2.785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preiss J. Regulation of the biosynthesis and degradation of starch. Annu Rev Plant Physiol. 1982;33:431–454. [Google Scholar]

- Preiss J. Bacterial glycogen synthesis and its regulation. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1984;38:419–458. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.38.100184.002223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preiss J. Biosynthesis of starch and its regulation. In: Preiss J, editor. The Biochemistry of Plants, Vol 14. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1988. pp. 181–254. [Google Scholar]

- Preiss J. Biology and molecular biology of starch synthesis and its regulation. In: Miflin BJ, editor. Surveys of Plant Molecular and Cell Biology, Vol. 7. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 1991. pp. 59–114. [Google Scholar]

- Preiss J (1997a) Modulation of starch synthesis. In C Foyer, P Quick, eds, Engineering Improved Carbon and Nitrogen Resource Use Efficiency in Higher Plants. Taylor and Francis, London, pp 81–104

- Preiss J (1997b) The chemistry and molecular biology of plant starch synthesis. In RL Whistler, JN BeMiller, eds, Starch: Chemistry and Technology, Ed 32. Academic Press, New York (in press)

- Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T (1989) Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual, Ed 2. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY, pp A.1–A.3

- Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulson AR. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayers JR, Schmidt W, Eckstein F. 5′-3′ Exonucleases in phosphorothioate-based oligonucleotide-directed mutagenesis. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:791–802. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.3.791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng J, Charng Y, Preiss J. Site-directed mutagenesis of lysine382, the activator-binding site, of ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase from Anabaena PCC 7120. Biochemistry. 1996;35:3115–3121. doi: 10.1021/bi952359j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith PK, Krohn RI, Hermanson GT, Mallia AK, Gartner FH, Provenzano MD, Fujimoto EK, Goeke NM, Olson BJ, Klenk DK. Measurement of protein using bicinchoninic acid. Anal Biochem. 1985;150:76–85. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(85)90442-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith-White BJ, Preiss J. Comparison of proteins of ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase from diverse sources. J Mol Evol. 1992;34:449–464. doi: 10.1007/BF00162999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villand P, Olsen OA, Kleczkowski L. Molecular characterization of multiple cDNA clones for ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase from Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Mol Biol. 1993;23:1279–1284. doi: 10.1007/BF00042361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]