Abstract

Interstitial lung disease (ILD) is commonly encountered in patients with connective tissue diseases (CTD). Besides the lung parenchyma, the airways, pulmonary vasculature and structures of the chest wall may all be involved, depending on the type of CTD. As a result of this so-called multi-compartment involvement, airflow limitation, pulmonary hypertension, vasculitis and extrapulmonary restriction can occur alongside fibro-inflammatory parenchymal abnormalities in CTD. Rheumatoid arthritis (RA), systemic sclerosis (SSc), poly-/dermatomyositis (PM/DM), Sjögren’s syndrome (SjS), systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), and undifferentiated (UCTD) as well as mixed connective tissue disease (MCTD) can all be associated with the development of ILD. Non-specific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP) is the most commonly observed histopathological pattern in CTD-ILD, but other patterns including usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP), organizing pneumonia (OP), diffuse alveolar damage (DAD) and lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia (LIP) may occur. Although the majority of patients with CTD-ILD experience stable or slowly advancing ILD, a small yet significant group exhibits a more severe and progressive course. Randomized placebo-controlled trials evaluating the efficacy of immunomodulatory treatments have been conducted only in SSc-associated ILD. However, clinical experience suggests that a handful of immunosuppressive medications are potentially effective in a sizeable portion of patients with ILD caused by other CTDs. In this manuscript, we review the clinical characteristics and management of the most common CTD-ILDs.

Keywords: connective tissue disease, interstitial lung disease, autoimmune disease, pulmonary fibrosis, rheumatoid arthritis, dermatomyositis, polymyositis, Sjogren’s syndrome, progressive systemic sclerosis, systemic lupus erythematosus, mixed connective tissue disease, undifferentiated connective tissue disease, lung-dominant connective tissue disease

Introduction

Lung involvement is common in connective tissue diseases (CTDs) and can lead to significant morbidity and shortened survival. Depending on the underlying CTD, various thoracic compartments can be involved simultaneously; although, for this review, we will focus on the parenchymal changes of CTD-associated interstitial lung disease (CTD-ILD). Most CTD-ILD presents with a dry cough, gradually progressive dyspnea and a restrictive ventilatory defect on pulmonary function tests (PFTs). Many patients diagnosed with CTD-ILD have a classifiable CTD at the time ILD is recognized; however, in up to 25% of cases a constellation of clinical and serological findings suggest, but are not entirely diagnostic of, a classifiable CTD. Patients in such a scenario have been labeled with “undifferentiated” CTD (UCTD), lung-dominant CTD and autoimmune-featured ILD by various investigators.1, 2 Lung disease can also predate extrapulmonary CTD manifestations by several years, thus making the distinction between CTD-ILD and an idiopathic interstitial pneumonia (IIP) difficult. 3 Below, we provide a general description of the physiological, histological and radiological findings and management features of CTD-ILD and proceed to highlight some of the unique and important aspects of ILD in the context of each individual CTD.

Clinical features of CTD-ILD

Pulmonary function testing (PFT)

The classic PFT pattern observed in CTD-ILD is a restrictive ventilatory defect and reduced diffusion capacity (DLco). However, when other thoracic compartments such as airways, vasculature or chest wall are involved (as may occur in CTD), clinicians should be aware that a different constellation of PFT-abnormalities can arise. For example, a disproportionate reduction in DLco may signify ILD with coexistent emphysema or pulmonary hypertension,4 or a significant reduction in lung volumes with relatively preserved DLco should raise suspicion for extrapulmonary restriction (e.g., chest wall skin thickening, respiratory muscle weakness or kyphoscoliosis).

Histopathological patterns

Except for rheumatoid arthritis (RA), in which UIP-pattern pathology is more common, the non-specific interstitial pneumonia-(NSIP-) pattern of lung injury is most common across all CTD-ILD.56 Compared with cases in which UIP-pattern injury is idiopathic (i.e., idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis [IPF]), CTD-associated UIP (CTD-UIP) has fewer fibroblastic foci, smaller honeycomb cysts, a greater number of germinal centers and more inflammation.7 Although results are conflicting, some studies suggest patients with CTD-UIP have a better prognosis than IPF-patients. Also a matter of debate, some studies suggest no difference in prognosis between CTD-UIP and CTD-NSIP, contrasting with what is known about the difference in prognosis between idiopathic NSIP and IPF. 6,8,9 Less commonly encountered injury patterns of CTD-ILD include organizing pneumonia (OP)—although OP not uncommonly occurs as a secondary feature in patients with CTD—diffuse alveolar damage (DAD), lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia (LIP) and desquamative interstitial pneumonia (DIP).

Because of conflicting study results, many clinicians are uncertain about the utility of surgical lung biopsy (SLBx) in their patients with CTD-ILD. On the one hand, many clinicians believe that, among patients with CTD-ILD, UIP-pattern histology confers a worse prognosis than NSIP-pattern histology. Those in this camp would have their CTD-ILD patients undergo SLBx, because the results could better define disease trajectory. On the other hand, clinicians not using SLBx in their patients with CTD-ILD are either unconvinced that the histological pattern trumps pulmonary physiology in determining prognosis, or more likely, do not expect the results to change management: they plan to treat (or perhaps already are treating) with immunosuppressive medications, and the SLBx pattern would not affect their choice of therapeutic agent or anticipated duration of therapy. When an etiology for the ILD other than CTD (e.g. hypersensitivity pneumonitis) is seriously considered or when imaging features suggest malignancy or infection (e.g. progressive nodules, cavitation, consolidation, pleural thickening or effusion), there is greater consensus about the utility of SLBx in this patient population.

High-resolution computer tomography (HRCT) findings

Most parenchymal abnormalities in CTD-ILD are easily appreciated with HRCT and commonly described using terminology applied to IIPs (Figures 1 and 2). While each CTD demonstrates a predilection for a certain pattern of parenchymal involvement, significant overlap exists (Table 1).10,11 Overall, a radiographic NSIP-pattern is found most commonly in CTD-ILDs and is characterized by intra- and interlobular reticular opacities in a predominantly subpleural and basilar distribution. Groundglass opacificities are usually considered to represent a higher degree of cellularity and suggest the disease is potentially more responsive to treatment, although in some cases this is not true. Subpleural sparing—an opacity-free, thin rim of parenchyma directly adjacent to the pleura in the posterior zones of the lung bases—hints at an underlying NSIP-pattern of lung injury and argues against the UIP-pattern. Reticulation, traction bronchiectasis and honeycombing reflect fibrotic changes and more advanced ILD. Abnormalities in other thoracic structures (e.g., esophageal or pulmonary artery dilatation) –hinting at the presence of multi-compartment involvement—should raise suspicion for the presence of a CTD.12,13

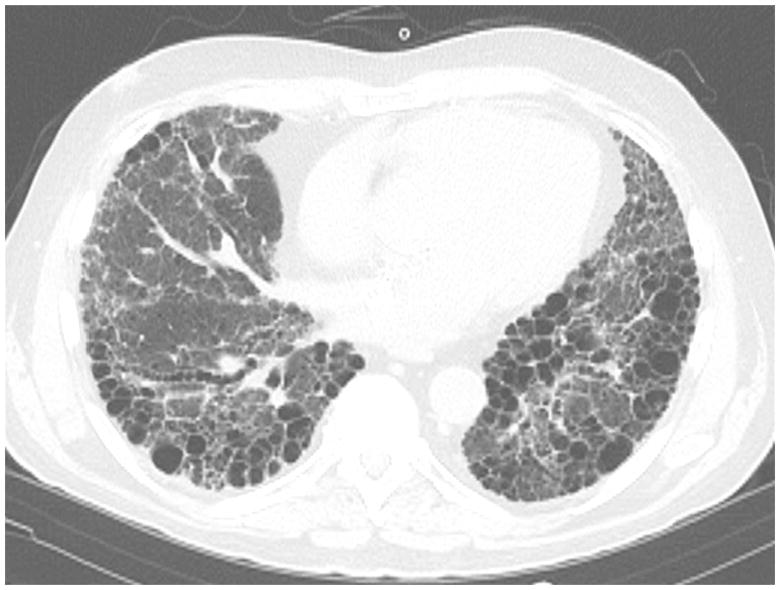

Figure 1.

Slice from a HRCT scan from a 65 year-old man with rheumatoid arthritis. Note the honeycombing characteristic of a radiographic UIP-pattern.

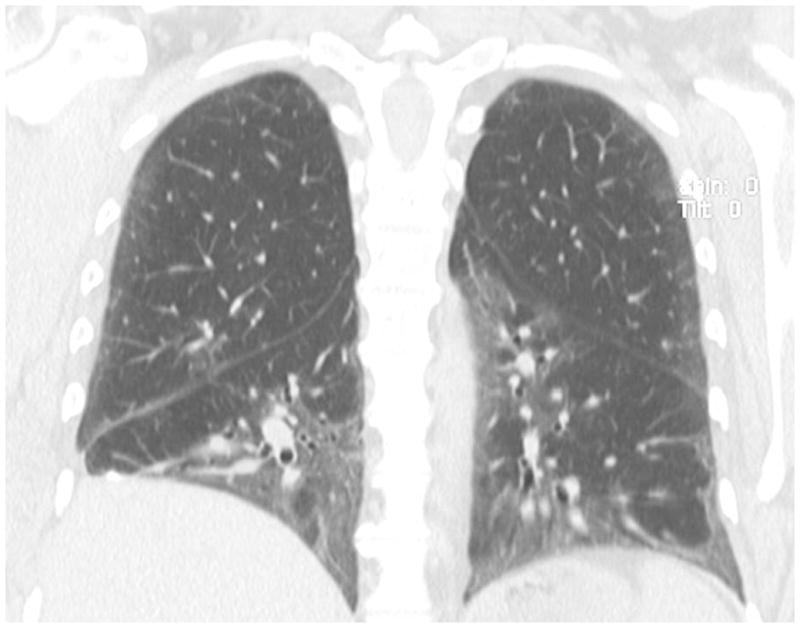

Figure 2.

Coronal view slice from a HRCT scan from a 58 year-old woman with dermatomyositis. Notice the ground glass opacities and traction bronchiolectasis characteristic of mixed cellular and fibrotic NSIP.

Table 1.

| NSIP | UIP | OP | PH | DAD | LIP | Hemorrhage | Airways disease | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RA | + | ++++ | ++ | + | + | + | ++++ | |

| SSc | ++++ | + | + | +++ | + | |||

| PM/DM | ++++ | + | ++++ | + | ||||

| SjS | ++ | + | + | + | + | ++++ | +++ | |

| MCTD | ++ | + | + | + | + | |||

| SLE | ++ | + | + | + | ++ | + | ++ | + |

The number of ‘+’ signs indicates the frequency of observed injury pattern, i.e., ++++ = very common or clinically prominent manifestation, + = less common, empty cells = rare or not described in this disease; RA=rheumatoid arthritis; SSc=systemic sclerosis; PM/DM=poly−/dermatomyositis; SjS=Sjögren’s syndrome; MCTD=mixed-connective tissue disease; SLE=systemic lupus erythematosus

Serological studies

Serum auto-antibodies will be explored in the sections covering each of the CTDs below.13

General Strategies in the Management of CTD-ILD

Not every patient with CTD-ILD requires treatment; thus, it is important to distinguish trivial disease (with low likelihood for progression) from clinically significant ILD. HRCT and PFTs are most helpful in objectively determining disease severity and its course over time, but strong consensus regarding which patients to treat, when and for how long has not been achieved for CTD-ILD. In our experience, patients with disease extent < 10% on HRCT and/or FVC >75% and/or DLco >65%, in the absence of respiratory symptoms, can be carefully monitored every 3–6 months for evidence of progression. Since immunomodulatory medications are associated with significant adverse effects, we reserve treatment for those cases with severe, extensive or progressive disease. Various regimens have been used to treat CTD-ILD, but the only large-scale, randomized trials have been conducted to examine the effectiveness of cyclophosphamide (or cyclophosphamide followed by azathioprine) in patients with SSc-ILD.14,15 Data for other immunomodulatory drugs (including azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil and tacrolimus) stem from case reports and observational case series.16,17,18 We typically evaluate the response to therapy every three months. A favorable response may be defined as improvement in symptoms and functional capacity, or disease extent on HRCT or pulmonary physiology; however, in this challenging spectrum of diseases, halting progression and maintaining stability should also be considered a success. As mentioned above, there are a number of questions that remain unanswered about the treatment of CTD-ILD, so this is an area ripe for investigation.

ILD in Specific CTDs

Rheumatoid arthritis

RA is the most common CTD and is characterized by an erosive inflammatory polyarthropathy with symmetrical arthritis and a range of pulmonary manifestations. While RA occurs more commonly in females (female to male ratio 3:1), RA-ILD is more frequent in males. The prevalence of RA-ILD varies from 5–58%, depending on the case definition for ILD.19,20,21 Smoking is a risk factor for RA-ILD, and emerging data suggest that cigarette smoke exerts its effects by promoting the citrullination of various proteins in the lung. In fact, theories have arisen that seropositive RA “starts” in the lung. 22,23 Severe ILD may occur when joint disease is mild or well-controlled with therapy—there appears to be no reliable correlation between the extent or severity of the joint disease and the development or progression of ILD in patients with RA.

RA-ILD manifests most commonly in the UIP-pattern, and less commonly with NSIP-pattern injury. However, clinicians caring for patients with RA must keep in mind that medications used to treat extrapulmonary disease (e.g., methotrexate) can cause ILD and predispose to opportunistic infections.

Thus, a detailed drug history is crucial in all patients with CTD-ILD. A temporal relationship between drug initiation and symptom onset and then improvement after withdrawal can point toward drug-induced lung disease. However, delayed reactions or continued progression despite stopping the medication can occur, making the differentiation between drug-induced ILD and worsening RA-ILD challenging. In this situation, diagnostic BAL can help to exclude infectious etiologies, while BAL-lymphocytosis and/or eosinophilia with or without peripheral blood eosinophilia can further support the diagnosis of drug-induced ILD. Some of the most commonly prescribed medications implicated in pulmonary toxicity include methotrexate, leflunomide, gold salts, sulfasalazine, and anti-tumor necrosis factor (anti-TNF) antibodies.24,25,26,27,28 A helpful online tool listing all medications associated with pulmonary toxicity in further detail can be found at pneumotox.com.29 We advocate against the use of drugs with high rates of pulmonary toxicity in RA patients with pre-existing lung disease.

Due to the absence of randomized controlled trials, the treatment of RA-ILD remains entirely empirical. High-dose corticosteroids are often used in patients with potentially reversible patterns such as OP or those with flares of RA-ILD. In addition, cyclophosphamide, azathioprine, cyclosporine or mycophenolate have been used as steroid sparing agents or in steroid-refractory cases.17,18,30 ,31,32 In our experience, biologic agents control the joint disease very well but have minimal effect on ILD. Lung transplantation is offered by certain centers to RA-ILD patients with limited joint disease and relatively preserved functional status.

Systemic sclerosis

Systemic sclerosis is the CTD with the largest percentage of patients afflicted with ILD (40–80% depending on method of ascertainment). Along with pulmonary hypertension (PH), ILD is a major cause of death in this disease.33,34 The frequency of ILD depends on ethnicity, autoantibody pattern and less so on the extent of skin disease. Most patients with SSc have high titers of antinuclear antibodies (ANA)—most often in a nucleolar pattern. Three antibodies with the highest specificity for SSc include antibodies against anti-RNA polymerase III (Pol3), anticentromere antibodies (ACA) and antibodies against topoisomerase (anti-Scl70). Anti-Scl70 antibodies are strongly associated with ILD. 35 Although ACA are protective from significant ILD, patients with ACA carry a high risk for the development of PH later in the course of the disease.35 The Pol3 antibody is seen with diffuse skin disease and renal crisis but is rarely associated with significant lung fibrosis.35

The majority of patients with SSc-ILD have NSIP-pattern injury.36 Less commonly a UIP-pattern is observed, and other histophatological patterns (e.g., OP or DAD) are very rare. As with other CTD-ILD patients, a subset with SSc-ILD is believed not to require treatment. Some experts adhere to using a staging system to help determine which SSc-ILD patients to treat with immunomodulatory therapy: Goh and colleagues observed that patients with lung involvement greater than 20% on HRCT and a FVC <70% of predicted were most likely to progress without therapy.37 Such patients with more severe disease are often treated aggressively.

Two randomized placebo controlled trials, the Scleroderma Lung Study (SLS) and the Fibrosing Alveolitis Scleroderma Trial (FAST), evaluated cyclophosphamide (given orally at 2mg/kg for one year in SLS, and intravenously at a dose of 600mg/m2 monthly for six months followed by oral azathioprine for the following six months in FAST) for SSc-ILD.14, 15 Results from both studies demonstrated a slower decline in FVC in the cyclophosphamide group compared with placebo. Intravenous administration of cyclophosphamide was associated with a lower rate of gonadal failure, severe infections and bone marrow toxicity compared to oral medication, presumably due to higher cumulative dose achieved with daily oral medication.38 Six months after discontinuation of immunosuppression, the improvements in FVC waned to baseline, suggesting prolonged immunomodulatory therapy may be required to maintain stability of lung function.39

Whether there is a causal relationship between ILD and esophageal dysmotility/gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD)/microaspiration is unclear, but we believe aggressive treatment of these abnormalities in patients with SSc-ILD (and any other ILD patient with them) is warranted. Co-management with gastroenterology can be helpful.

Poly-/Dermatomyositis

Both PM and DM share the diagnostic criteria of symmetrical proximal muscle weakness, raised serum muscle enzymes, and muscle biopsy and electromyography results consistent with myositis. In addition, DM requires the presence of certain skin manifestations (e.g., heliotrope rash and Gottron’s sign) to fulfill diagnostic criteria. 40,41 In amyopathic DM, classical skin findings of DM are present without muscle involvement.42 Overall, pulmonary disease is present in one- to two-thirds of patients and is a significant cause of mortality in PM/DM.43

In patients with clinically significant disease, two main types of clinical presentations have been observed. The first is characterized by subacute onset of dyspnea and widespread basilar predominant ground glass opacities and consolidation against a background of reticulation with traction bronchiectasis on CT.44 Many patients presenting this way progress significantly over a few weeks to months and are refractory to therapy. Histopathologically, a DAD pattern atop both OP and NSIP has been described in this setting.45,46 The other form of presentation is more common and involves an insidious onset and slowly progressive dyspnea. A combined pattern of NSIP and OP are observed on HRCT and in histopathological specimens.47,48,49 Other patients with PM/DM can present with a UIP-pattern of lung injury.

As with most CTDs, lung involvement in PM/DM may occur before, after or at the same time of the development of extrapulmonary manifestations.50,51 Risk factors for the development of PM/DM-ILD include a higher age (>45), joint involvement,51,52 and in particular, the presence of aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase (i.e., anti-synthetase or AS) antibodies. The most commonly identified AS antibody is directed against anti-histidyl-tRNA synthetase (anti-Jo1) and is present in 25–40% of all patients with PM/DM53,54,55 and in 30–75% of those cases with ILD.49,52,56, 57, 58 Other less commonly found antibodies include anti-PL-7, -PL-12, -OJ, -EJ, -KS and -Zo.51,55,59 The combination of arthritis, myositis, anti-synthetase antibodies and ILD constitutes the anti-synthetase syndrome. Raynaud’s phenomenon, “mechanic’s hands” (dry, rough, fissured skin of the hands, particularly on the thenar side of the index finger and the finger tips) and fever, while not part of the diagnostic criteria of anti-synthetase syndrome, are other findings frequently encountered.59 It is not entirely clear whether AS antibodies are pathogenic or merely disease markers. In addition, it is unknown whether the different AS antibodies portend different clinical phenotypes.

As with most other CTDs, no definitive recommendations for the treatment of PM/DM-associated ILD exist due to the lack of randomized clinical trials. High-dose oral prednisone is often used as first-line therapy in PM/DM-associated ILD. In the US, azathioprine and mycophenolate are the most frequently used immunomodulatory agents for PM/DM-ILD; however, there are case reports and case series suggesting a role for the calcineurin antagonists.60,61 In severe, rapidly progressive disease, intravenous cyclophosphamide in conjunction with high-dose methylprednisone has been used.62,63 Rituximab has been tried in patients who failed to respond to conventional immunosuppressive regimens or who presented with rapidly progressive DAD.64,65 In addition to treating refractory myositis, intravenous immunoglobulins have been used with some success to treat rapidly progressive ILD.66 In PM/DM the risk of malignancy is increased and screening for occult neoplasm should be considered, particularly in patient without AS antibodies.

Sjögren’s syndrome

In 1933 Sjýgren introduced the term “keratoconjunctivitis sicca”, also referred to as “sicca complex” to describe a syndrome characterized by dry eyes and dry mouth.67 Sjýgren’s syndrome (SjS) is a chronic inflammatory condition characterized by lymphocytic infiltration of exocrine glands (including salivary and lacrimal glands) – and other structures, including the lungs. It can occur either in isolation, when it is referred to as primary SjS, or as a secondary phenomenon in the setting of another established CTD, in which case it is termed secondary SjS.68 The primary form displays more severe exocrine dysfunction including renal tubular disorder, neurological involvement and vascular disorders (Raynaud’s phenomenon and vasculitis).69 In the absence of a salivary gland biopsy demonstrating focal lymphocytic sialoadenitis, the presence of “keratoconjunctivitis sicca” and anti-nuclear antibodies against ribonucleoproteins Ro/SSA and La/SSB is required to fulfill diagnostic criteria in both primary and secondary SjS.69 Polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia, elevated sedimentation rate and other autoimmune antibodies (e.g., rheumatoid factor) can be found with varying frequency in SjS and are non-specific.70,71 Patients with SjS are at increased risk for pulmonary and other lymphomas. 72,73

Although restriction and reduced DLco have been found in 17%–37.5% of patients with SjS, clinically significant ILD is rare, and in most cases SjS-ILD follows a mild and self-limited course.74,75 Respiratory symptoms mostly relate to dry mucous membranes predisposing patients with SjS to hoarseness and dry cough (due to xerotrachea). Patients with SjS are at increased risk of respiratory tract infections due to impaired immune function of the mucosal barrier lining the airway epithelium. Exertional dyspnea is reported by some patients.75,76 Pleuritis, PAH, middle lobe syndrome and shrinking lung syndrome have been described in SjS rarely.77,78,79,80

Authors of older series reported LIP as the most common histopathological pattern in patients with SjS, but more recent studies have revealed a higher frequency of NSIP-pattern injury in this disease.81,82 This finding is likely based on the reclassification of many cases as cellular NSIP, which in the past would have been interpreted as LIP.83 Other less commonly observed patterns include OP and UIP. In patients with SjS-ILD, HRCT- and histopathological findings correlate well with each other, so SLBx is usually not recommended.82,84,85 However, radiographic features suggestive of lymphoma (see below) require thorough investigation.86 Ground glass opacities and thin-walled cysts in a peri-bronchovascular distribution can occur with LIP. Centrilobular nodules are noted with LIP or lymphocytic bronchiolitis. Pulmonary lymphoma accounts for approximately 20% of all SjS-associated lymphomas.73,74 Both LIP and pulmonary lymphoma have overlapping features, including ground glass opacification, small nodules and hilar-mediastinal lymphadenopathy. Consolidation, large nodules measuring more than 10 mm as well as pleural effusions are more common in lymphoma, whereas cysts are more frequently observed in LIP. 87

Unclassifiable connective tissue disease

A large minority of patients with ILD do not fulfill the diagnostic criteria for any specific CTD but display features including positive serologies and systemic extrapulmonary manifestations that are reminiscent of an underlying autoimmune disease. Such patients have been labeled as having an “autoimmune flavor”.87 Over the course of follow-up, a number of these patients go on to develop clinical and serological characteristics that fulfill diagnostic criteria for a specific CTD. 88 Ongoing investigations aim to determine how best to follow, treat and conduct research in this interesting population. Such patients are different from those with anti-U1 RNP antibodies and features of more than one specific CTD who have mixed connective tissue disease (MCTD)–a specific CTD. 89 While a large number of patients with MCTD have pulmonary involvement, most have relatively mild disease, and many are asymptomatic. 90 Pleural effusions, ILD consistent with NSIP and sometimes UIP, and PAH, either as a result of CTD-ILD or in isolation, have all been described in MCTD. 91,92

Systemic lupus erythematosus

SLE is a multisystem disorder afflicting joints, skin, kidneys, central nervous system, serosal surfaces of internal organs including heart and lungs. The disease is more prevalent in women of reproductive age and African Americans.93 Almost all patients are anti-nuclear antibody (ANA) positive.94,95 Four or more criteria are required to establish the diagnosis.96 Interestingly, these criteria do not include any pulmonary manifestations, except for pleuritis. Although respiratory symptoms associated with SLE are often absent, abnormal PFT- and HRCT-findings are common, and the prognosis is significantly worse in patients experiencing pulmonary complications.97,98,99,100

While trivial lung disease is present in one third of patients, clinically significant disease afflicts only 3% to 8% of the lupus population.101,102 In some cases, acute lupus pneumonitis (ALP) with a DAD-pattern heralds the development of ILD.103 Similar to most other CTD-ILDs, NSIP is the most commonly observed histopathological pattern, but LIP, OP and UIP have all been described.98,104,104,105,106 Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage (DAH) and ALP are characterized by acute onset of dyspnea with fever, cough and in the case of DAH, sometimes hemoptysis. A sudden decrease in hemoglobin is highly suggestive of DAH.99,104,107,108 Approximately one-half of patients with DAH require mechanical ventilation. An increasingly bloody return on BAL is diagnostic and supported by high counts of red blood cells and hemosiderin-laden macrophages on the differential cell count. A neutrophilic capillaritis and alveoli filled with red blood cells are seen on histopathology of lung tissue from patients with DAH.109 In ALP, the histopathological picture resembles DAD but without hemorrhage or capillaritis.99 Both ALP and DAH present with diffuse, bilateral ground glass opacities on HRCT. In this setting pulmonary edema, drug reactions as well as infection all need to be excluded.

Due to the high incidence of infections in SLE, broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy should be started empirically without delay, while infectious etiologies are excluded and before aggressive immunosuppression is initiated. DAH and ALP carry a mortality rate of 50%.104,109 In patients requiring mechanical ventilation a lung protective strategy with low tidal volumes should be used. We recommend high-dose intravenous methylprednisone (1 g daily for 72 hours) followed by oral corticosteroids and possibly intravenous cyclophosphamide. In refractory cases of DAH or ALP, plasmapheresis and intravenous immunoglobulins have been described. 99,104 Success with rituximab has also been reported.109

Conclusions

CTD-ILD comprises a heterogeneous group of disorders marked by varying degrees of fibrosis and/or inflammation within the lung parenchyma. ILD is a potentially morbid and life-threatening complication of any CTD, but it is most commonly seen in patients with RA, SSc or PM/DM. A large group of patients have features suggestive of CTD but cannot be classified according to currently available systems. How best to treat them—or other patients with CTD-ILD—is based largely on experience and observational studies. Future research is required to advance understanding of the pathogenesis of CTD-ILD and to help determine which patients require therapy, what drugs to use and how long to use them.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Swigris is supported in part by a Career Development Award from the NIH (K23 HL092227).

Footnotes

Disclosure

No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

References

- 1••.Fischer A, West SG, Swigris JJ, Brown KK, du Bois RM. Connective tissue disease-associated interstitial lung disease: a call for clarification. Chest. 2010;138(2):251–6. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-0194. A synopsis and discussion of “lung-dominant connective tissue diseases”, “autoimmune-featured ILD” and “undifferentiated connective tissue diseases” including a proposal for criteria to more accurately capture the group of “lung-dominant CTDs”. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vij R, Noth I, Strek ME. Autoimmune-featured interstitial lung disease: a distinct entity. Chest. 2011;140(5):1292–9. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-2662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Homma Y, Ohtsuka Y, Tanimura K, Kusaka H, Munakata M, Kawakami Y, Ogasawara H. Can interstitial pneumonia as the sole presentation of collagen vascular diseases be differentiated from idiopathic interstitial pneumonia? Respiration. 1995;62(5):248. doi: 10.1159/000196457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4••.Wells AU. Pulmonary function tests in connective tissue disease. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;28:379–388. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-985610. Excellent summary on pulmonary function test patterns observed in CTD-ILD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee H, Kim DS, Yoo B, Seo JB, Rho J, Colby TV, et al. Histopathologic pattern and clinical features of rheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial lung disease. Chest. 2005;127:2019–2027. doi: 10.1378/chest.127.6.2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6•.Tanaka N, Kim JS, Newell JD, Brown KK, Cool CD, Meehan R, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis-related lung diseases: CT findings. Radiology. 2004;232:81–91. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2321030174. Description of characteristic HRCT-patterns in patients with RA-related ILD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Song JW, Do K, Kim M, Jang SJ, Colby TV, Kim DS. Pathologic and radiologic differences between idiopathic and collagen vascular disease-related usual interstitial pneumonia. Chest. 2009;136:23–30. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-2572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Park JH, Kim DS, Park I, Jang SJ, Kitaichi M, Nicholson AG, et al. Prognosis of fibrotic interstitial pneumonia: idiopathic versus collagen vascular disease-related subtypes. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:705–711. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200607-912OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim EJ, Elicker BM, Maldonado F, Webb WR, Ryu JH, Van Uden JH, et al. Usual interstitial pneumonia in rheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial lung disease. Eur Respir J. 2010;35:1322–1328. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00092309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10••.King TE, Jr, Kim EJ, Kinder BW. Connective Tissue Diseases. In: King TE, Schwartz M, editors. Interstitial Lung Disease. 5. 2011. Detailed review of connective tissue disease – related interstitial lung diseases from standard reference textbook for the interstitial lung diseases. [Google Scholar]

- 11••.Kim EA, Lee KS, Johkoh T, et al. Interstitial lung diseases associated with collagen vascular diseases: radiologic and histopathologic findings. RadioGraphics. 2002;22:S151–S165. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.22.suppl_1.g02oc04s151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12••.Hwang JH, Misumi S, Sahin H, et al. Computed tomographic features of idiopathic fibrosing interstitial pneumonia: comparison with pulmonary fibrosis related to collagen vascular disease. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2009;33:410–415. doi: 10.1097/RCT.0b013e318181d551. Comprehensive reviews of radiologic and histopathologic features in CTD-ILD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13••.Lynch DA. Lung Disease Related to Collagen Vascular Disease. J Thoracic Imaging. 2009;24(4):299–309. doi: 10.1097/RTI.0b013e3181c1acec. Excellent overview of radiologic, serologic and histopathologic patterns of lung injury from CTD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tashkin DP, Elashoff R, Clements PJ, Goldin J, Roth MD, Furst DE, et al. Cyclophosphamide versus placebo in scleroderma lung disease. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2655–2666. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoyles RK, Ellis RW, Wellsbury J, Lees B, Newlands P, Goh NSL, et al. A multicenter, prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of and intravenous cyclophosphamide followed by oral azathioprine for the treatment of pulmonary fibrosis in scleroderma. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:3962–3970. doi: 10.1002/art.22204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saketkoo LA, Espinoza LR. Experience of mycophenolate mofetil in 10 patients with autoimmune-related interstitial lung disease demonstrates promising effects. Am J Med Sci. 2009 May;337(5):329–35. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e31818d094b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Swigris JJ, Olson AL, Fischer A, et al. Mycophenolate mofetil is safe, well-tolerated, and preserves lung function in patients with connective tissue disease-related interstitial lung disease. Chest. 2006;130:30–36. doi: 10.1378/chest.130.1.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kobayashi A, Okamoto H. Treatment of interstitial lung diseases associated with connective tissue diseases. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2012;5(2):219–27. doi: 10.1586/ecp.12.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hyland RH, Gordon DA, Broder I, Davies GM, Russell ML, Hutcheon MA, et al. A systematic controlled study of pulmonary abnormalities in rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 1983;10:395–405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jurik AG, Davidsen D, Graudal H. Prevalence of pulmonary involvement in rheumatoid arthritis and its relationship to some characteristics of the patients. A radiological and clinical study. Scand J Rheumatol. 1982;11:217–224. doi: 10.3109/03009748209098194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gabbay E, Tarala R, Will R, Carroll G, Adler B, Cameron D, Lake FR. Interstitial lung disease in recent onset rheumatoid arthritis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;156:528–535. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.156.2.9609016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saag KG, Cerhan JR, Kolluri S, Ohashi K, Hunninghake GW, Schwartz DA. Cigarette smoking and rheumatoid arthritis severity. Ann Rheum Dis. 1997;56:463–469. doi: 10.1136/ard.56.8.463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Deane KD, Norris JM, Holers VM. Preclinical rheumatoid arthritis: identification, evaluation, and future directions for investigation. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2010;36(2):213–41. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2010.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barrera P, Laan RF, van Riel PL, Dekhuijzen PN, Boerbooms AM, van de Putte LB. Methotrexate-related pulmonary complications in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1994;53:434–439. doi: 10.1136/ard.53.7.434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sakai F, Noma S, Kurihara Y, Yamada H, Azuma A, Kudoh S, et al. Leflunomide-related lung injury in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: imaging features. Mod Rheumatol. 2005;15:173–179. doi: 10.1007/s10165-005-0387-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scott DL, Bradby GV, Aitman TJ, Zaphiropoulos GC, Hawkins CF. Relationship of gold and penicillamine therapy to diffuse interstitial lung disease. Ann Rheum Dis. 1981;40:136–141. doi: 10.1136/ard.40.2.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Parry SD, Barbatzas C, Peel ET, Barton JR. Sulphasalazine and lung toxicity. Eur Respir J. 2002;19:756–764. doi: 10.1183/09031936.02.00267402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thavarajah K, Wu P, Rhew EJ, Yeldandi AK, Kamp DW. Pulmonary complications of tumor necrosis factor-targeted therapy. Respir Med. 2009;103:661–669. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29••.pneumotox.com. Foucher P, Camus P. The drug-induced lung diseases. Very useful online tool that allows searches for individual medications listing all respective drug-induced pulmonary complications described in the literature. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abel T, Andrews BS, Cunningham PH, et al. Rheumatoid vasculitis: Effect of cyclophosphamide on the clinical course and levels of circulating immune complexes. Ann Intern Med. 1980;93:407–413. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-93-3-407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chang HK, Park W, Ryu DS. Successful treatment of progressive rheumatoid interstitial lung disease with cyclosporine: A case report. J Korean Med Sci. 2002;17:270–273. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2002.17.2.270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Scott DGI, Bacon PA. Resonse to methotrexate in fibrosing alveolitis associated with connective tissue disease. Thorax. 1980;35:725–731. doi: 10.1136/thx.35.10.725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33•.Steen VD. Clinical manifestations of systemic sclerosis. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 1998;17:48–54. doi: 10.1016/s1085-5629(98)80062-x. A comprehensive review of the general clinical features of systemic sclerosis. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hachulla E, de Groote P, Gressin V, Sibilia J, Diot E, Carpentier P, et al. The three-year incidence of pulmonary arterial hypertension associated with systemic sclerosis in a multicenter nationwide longitudinal study in France. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:1831–1839. doi: 10.1002/art.24525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35•.Reveille JD, Solomon DH. Evidence-based guidelines for the use of immunologic tests: anticentromere, Scl-70, and nucleolar antibodies. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;49:399–412. doi: 10.1002/art.11113. This article is part of a series on immunologic testing guidelines published by the American College of Rheumatology and HOC Committee on Immunologic Testin. For further details an introduction to this series has been published in Arthritis Care and Research, Vol 47, Nr 4, August 2002 pp 429–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bouros D, Wells AU, Nicholson AG, Cobly TV, Polychronopoulos V, Pantelidis P, et al. Histopathologic subsets of fibrosing alveolitis in patients with systemic sclerosis and their relationship to outcome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165:1581–1586. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2106012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Goh NSL, Desai SR, Veeraraghavan S, Hansell DM, Copley SJ, Maher TM, et al. Interstitial lung disease in systemic sclerosis: a simple staging system. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177:1248–1254. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200706-877OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Haubitz M, Schellong S, Gýbel U, Schurek HJ, Schaumann D, Koch KM, et al. Intravenous pulse administration of cyclophosphamide versus daily oral treatment in patients with antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis and renal involvement: a prospective, randomized study. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41:1835–1844. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199810)41:10<1835::AID-ART16>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tashkin DP, Elashoff R, Clements PJ, Roth MD, Furst DE, Silver RM, et al. Effects of 1-year treatment with cyclophosphamide on outcomes at 2 years in scleroderma lung disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176:1026–1034. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200702-326OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40•.Bohan A, Peter JB. Polymyositis and dermatomyositis (first of two parts) N Engl J Med. 1975;292:344–347. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197502132920706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41•.Bohan A, Peter JB. Polymyositis and dermatomyositis (second of two parts) N Engl J Med. 1975;292:403–407. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197502202920807. Original description and diagnostic criteria for polymyositis and dermatomyositis by Bohan and Peter. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Krain L. Dermatomyositis in six patients without initial muscle involvement. Arch Dermatol. 1975;111:241–245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43•.Fathi M, Lundberg IE, Tornling G. Pulmonary complications of polymyositis and dermatomyositis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;28:451–458. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-985666. A comprehensive review of polymyositis and dermatomyositis with emphasis on the pulmonary manifestation. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44•.Ikezoe J, Johkoh T, Kohno N, et al. High-resolution CT findings of lung disease in patients with polymyositis and dermatomyositis. J Thorac Imag. 1996;11:250–259. doi: 10.1097/00005382-199623000-00002. A review of radiological features on chest HRCT in PM/DM. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schwarz MI. The lung in polymyositis. Clin Chest Med. 1998;19:701–12. viii. doi: 10.1016/s0272-5231(05)70111-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Won Huh J, Soon Kim D, Keun Lee C, Yoo B, Bum Seo J, Kitaichi M, et al. Two distinct clinical types of interstitial lung disease associated with polymyositis dermatomyositis. Respir Med. 2007;101:1761–1769. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2007.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tansey D, Wells AU, Colby TV, Ip S, Nikolakoupolou A, du Bois RM, et al. Variations in histological patterns of interstitial pneumonia between connective tissue disorders and their relationship to prognosis. Histopathology. 2004;44:585–596. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2004.01896.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cottin V, Thivolet-Béjui F, Reynaud-Gaubert M, Cadranel J, Delaval P, Ternamian PJ, et al. Interstitial lung disease in amyopathic dermatomyositis, dermatomyositis and polymyositis. Eur Respir J. 2003;22:245–250. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00026703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Douglas WW, Tazelaar HD, Hartman TE, Hartman RP, Decker PA, Schroeder DR, et al. Polymyositis-dermatomyositis-associated interstitial lung disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:1182–1185. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.7.2103110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schnabel A, Reuter M, Biederer J, Richter C, Gross WL. Interstitial lung disease in polymyositis and dermatomyositis: clinical course and response to treatment. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2003;32:273–284. doi: 10.1053/sarh.2002.50012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Friedman AW, Targoff IN, Arnett FC. Interstitial lung disease with autoantibodies against aminoacylt RNA synthetases in the absence of clinically apparent myositis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1996;26:459–467. doi: 10.1016/s0049-0172(96)80026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chen I, Jan Wu Y, Lin C, Fan K, Luo S, Ho H, et al. Interstitial lung disease in polymyositis and dermatomyositis. Clin Rheumatol. 2009;28:639–646. doi: 10.1007/s10067-009-1110-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53•.Dalakas M, Hohlfeld R. Polymyositis and dermatomyositis. Lancet. 2003;362:971–982. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14368-1. A comprehensive review of the general clinical features of polymyositis and dermatomyositis. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Evans J. Antinuclear antibody testing in systemic autoimmune disease. Clin Chest Med. 1998;19:613–625. vii. doi: 10.1016/s0272-5231(05)70106-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Targoff IN. Humoral immunity in polymyositis/dermatomyositis. J Invest Dermatol. 1993;100:116S–123S. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12356607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Marie I, Hachulla E, Chérin P, Dominique S, Hatron P, Hellot M, et al. Interstitial lung disease in polymyositis and dermatomyositis. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;47:614–622. doi: 10.1002/art.10794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Marie I, Hatron PY, Hachulla E, Wallaert B, Michon-Pasturel U, Devulder B. Pulmonary involvement in polymyositis and in dermatomyositis. J Rheumatol. 1998;25:1336–1343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Selva-O’Callaghan A, Labrador-Horrillo M, Muñoz-Gall X, Martínez-Gomez X, Majó-Masferrer J, Solans-Laque R, et al. Polymyositis/dermatomyositis associated lung disease: analysis of a series of 81 patients. Lupus. 2005;14:534–542. doi: 10.1191/0961203305lu2158oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Imbert-Masseau A, Hamidou M, Agard C, Grolleau JY, Chérin P. Antisynthetase syndrome. Joint Bone Spine. 2003;70:161–168. doi: 10.1016/s1297-319x(03)00012-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ando M, Miyazaki E, Yamasue M, Sadamura Y, Ishii T, Takenaka R, Ito T, Nureki S, Kumamoto T. Successful treatment with tacrolimus of progressive interstitial pneumonia associated with amyopathic dermatomyositis refractory to cyclosporine. Clin Rheumatol. 2010;29(4):443–5. doi: 10.1007/s10067-009-1358-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ochi S, Nanki T, Takada K, Suzuki F, Komano Y, Kubota T, Miyasaka N. Favorable outcomes with tacrolimus in two patients with refractory interstitial lung disease associated with polymyositis/dermatomyositis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2005;23(5):707–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yamasaki Y, Yamada H, Yamasaki M, Ohkubo M, Azuma K, Matsuoka S, Kurihara Y, Osada H, Satoh M, Ozaki S. Intravenous cyclophosphamide therapy for progressive interstitial pneumonia in patients with polymyositis/dermatomyositis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2007;46(1):124. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kel112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kameda H, Nagasawa H, Ogawa H, Sekiguchi N, Takei H, Tokuhira M, Amano K, Takeuchi T. Combination therapy with corticosteroids, cyclosporin A, and intravenous pulse cyclophosphamide for acute/subacute interstitial pneumonia in patients with dermatomyositis. J Rheumatol. 2005;32(9):1719. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sem M, Molberg O, Lund MB, Gran JT. Rituximab treatment of the anti-synthetase syndrome: a retrospective case series. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2009;48:968–971. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kep157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lambotte O, Kotb R, Maigne G, Blanc F, Goujard C, Delfraissy JF. Efficacy of rituximab in refractory polymyositis. J Rheumatol. 2005;32:1369–1370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Suzuki Y, Hayakawa H, Miwa S, Shirai M, Fujii M, Gemma H, Suda T, Chida K. Intravenous immunoglobulin therapy for refractory interstitial lung disease associated with polymyositis/dermatomyositis. Lung. 2009;187(3):201. doi: 10.1007/s00408-009-9146-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sjögren H. Zur Kenntnis der Keratoconjunctivitis sicca. Acta Ophthalomol. 1933;11(suppl II):1. [Google Scholar]

- 68•.Vitali C, Bombardieri S, Jonsson R, Moutsopoulos HM, Alexander EL, Carsons SE, et al. Classification criteria for Sjýgren’s syndrome: a revised version of the European criteria proposed by the American-European Consensus Group. Ann Rheum Dis. 2002;61:554–558. doi: 10.1136/ard.61.6.554. Diagnostic criteria for primary and secondary Sjýgren’s syndrome following revision by the European Study Group on Classification Criteria for Sjýgren’s syndrome. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Alexander EL, Provost TT, Stevens MB, Alexander GE. Neurologic complications of primary Sjýgren’s syndrome. Medicine (Baltimore) 1982;61:247–257. doi: 10.1097/00005792-198207000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Carine S, Gottenberg JE, Bengoufa D, Desmoulins F, Miceli-Richard C, Mariette X. Anticentromere antibodies identify patients with Sjýgren’s syndrome and autoimmune overlap syndrome. J Rheumatol. 2007;34:2253–2258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Fischbach M, Char D, Christensen M, et al. Immune complexes in Sjýgren’s syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 1980;23:791–795. doi: 10.1002/art.1780230703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72•.Fox R. Sjýgren’s syndrome. Lancet. 2005;366:321–331. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66990-5. A comprehensive review of the general clinical features of Sjýgren’s syndrome. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Royer B, Cazals-Hatem D, Sibilia J, Agbalika F, Cayuela JM, Soussi T, et al. Lymphomas in patients with Sjýgren’s syndrome are marginal zone B-cell neoplasms, arise in diverse extranodal and nodal sites, and are not associated with viruses. Blood. 1997;90:766–775. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Papathanasiou MP, Constantopoulos SH, Tsampoulas C, Drosos AA, Moutsopoulos HM. Reappraisal of respiratory abnormalities in primary and secondary Sjýgren’s syndrome. A controlled study. Chest. 1986;90:370–374. doi: 10.1378/chest.90.3.370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ramos-Casals M, Solans R, Rosas J, Camps MT, Gil A, Del Pino-Montes J, et al. Primary Sjýgren syndrome in Spain: clinical and immunologic expression in 1010 patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 2008;87:210–219. doi: 10.1097/MD.0b013e318181e6af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Constantopoulos SH, Papadimitriou CS, Moutsopoulos HM. Respiratory manifestations in primary Sjýgren’s syndrome. A clinical, functional, and histologic study. Chest. 1985;88:226–229. doi: 10.1378/chest.88.2.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77•.Cain HC, Noble PW, Matthay RA. Pulmonary manifestations of Sjýgren’s syndrome. Clin Chest Med. 1998;19:687–99. viii. doi: 10.1016/s0272-5231(05)70110-6. A comprehensive review of the pleuro-pulmonary manifestations of SjS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Launay D, Hachulla E, Hatron P, Jais X, Simonneau G, Humbert M. Pulmonary arterial hypertension: a rare complication of primary Sjýgren syndrome: report of 9 new cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore) 2007;86:299–315. doi: 10.1097/MD.0b013e3181579781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Chen H, Lai S, Kwang W, Liu J, Chen C, Huang D. Middle lobe syndrome as the pulmonary manifestation of primary Sjýgren’s syndrome. Med J Aust. 2006;184:294–295. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2006.tb00242.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Tavoni A, Vitali C, Cirigliano G, Frigelli S, Stampacchia G, Bombardieri S. Shrinking lung in primary Sjýgren’s syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42:2249–2250. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199910)42:10<2249::AID-ANR31>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81•.Parambil JG, Myers JL, Lindell RM, Matteson EL, Ryu JH. Interstitial lung disease in primary Sjýgren syndrome. Chest. 2006;130:1489–1495. doi: 10.1378/chest.130.5.1489. A comprehensive overview of interstitial lung diseases in SjS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Yamadori I, Fujita J, Bandoh S, Tokuda M, Tanimoto Y, Kataoka M, et al. Nonspecific interstitial pneumonia as pulmonary involvement of primary Sjýgren’s syndrome. Rheumatol Int. 2002;22:89–92. doi: 10.1007/s00296-002-0204-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bradley B, Branley HM, Egan JJ, Greaves MS, Hansell DM, Harrison NK, et al. Interstitial lung disease guideline: the British Thoracic Society in collaboration with the Thoracic Society of Australia and New Zealand and the Irish Thoracic Society. Thorax. 2008;63 (Suppl 5):v1–58. doi: 10.1136/thx.2008.101691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Devaraj A, Wells AU, Hansell DM. Computed tomographic imaging in connective tissue diseases. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;28:389–397. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-985611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Koyama M, Johkoh T, Honda O, Mihara N, Kozuka T, Tomiyama N, et al. Pulmonary involvement in primary Sjýgren’s syndrome: spectrum of pulmonary abnormalities and computed tomography findings in 60 patients. J Thorac Imaging. 2001;16:290–296. doi: 10.1097/00005382-200110000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86•.Honda O, Johkoh T, Ichikado K, Tomiyama N, Maeda M, Mihara N, et al. Differential diagnosis of lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia and malignant lymphoma on high-resolution CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1999;173:71–74. doi: 10.2214/ajr.173.1.10397102. An interesting study comparing HRCT-findings of lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia and malignant lymphoma of the chest to delineate the differentiating features of these two disorders. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Cervera R, Khamashta MA, Hughes GR. “Overlap” syndromes. Ann Rheum Dis. 1990;49(11):947. doi: 10.1136/ard.49.11.947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88•.Mosca M, Tani C, Neri C, Baldini C, Bombardieri S. Undifferentiated connective tissue diseases (UCTD) Autoimmun Rev. 2006;6(1):1. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2006.03.004. Description of “undifferentiated connective tissue diseases” as a distinct disease entity. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89•.Sharp GC, Irvin WS, Tan EM, Gould RG, Holman HR. Mixed connective tissue disease--an apparently distinct rheumatic disease syndrome associated with a specific antibody to an extractable nuclear antigen (ENA) Am J Med. 1972;52(2):148. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(72)90064-2. Original description of “mixed connective tissue disease” as a separate disease entity by Sharp et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Bodolay E, Szekanecz Z, Dévényi K, Galuska L, Csípo I, Vègh J, et al. Evaluation of interstitial lung disease in mixed connective tissue disease (MCTD) Rheumatology (Oxford) 2005;44:656–661. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keh575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91•.Prakash UB. Respiratory complications in mixed connective tissue disease. Clin Chest Med. 1998;19:733–46. ix. doi: 10.1016/s0272-5231(05)70113-1. A comprehensive review of MCTD-related pulmonary complications. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Sullivan WD, Hurst DJ, Harmon CE, Esther JH, Agia GA, Maltby JD, et al. A prospective evaluation emphasizing pulmonary involvement in patients with mixed connective tissue disease. Medicine (Baltimore) 1984;63:92–107. doi: 10.1097/00005792-198403000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Chakravarty EF, Bush TM, Manzi S, Clarke AE, Ward MM. Prevalence of adult systemic lupus erythematosus in California and Pennsylvania in 2000: estimates obtained using hospitalization data. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:2092–2094. doi: 10.1002/art.22641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Swaak AJ, Nossent JC, Smeenk RJ. Systemic lupus erythematosus. Int J Clin Lab Res. 1992;22:190–195. doi: 10.1007/BF02591422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Cervera R, Khamashta MA, Font J, Sebastiani GD, Gil A, Lavilla P, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus: clinical and immunologic patterns of disease expression in a cohort of 1,000 patients. The European Working Party on Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Medicine (Baltimore) 1993;72:113–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96•.Tan EM, Cohen AS, Fries JF, Masi AT, McShane DJ, Rothfield NF, et al. The 1982 revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1982;25:1271–1277. doi: 10.1002/art.1780251101. Revised Criteria for the diagnosis of SLE from the Subcommittee for Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Criteria of the American Rheumatism Association Diagnostic and Therapeutic Criteria Committee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Fenlon HM, Doran M, Sant SM, Breatnach E. High-resolution chest CT in systemic lupus erythematosus. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1996;166:301–307. doi: 10.2214/ajr.166.2.8553934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98•.Pego-Reigosa JM, Medeiros DA, Isenberg DA. Respiratory manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus: old and new concepts. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2009;23:469–480. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2009.01.002. Concise review of the pulmonary manifestations in SLE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Cervera R, Khamashta MA, Font J, Sebastiani GD, Gil A, Lavilla P, et al. Morbidity and mortality in systemic lupus erythematosus during a 5-year period. A multicenter prospective study of 1,000 patients. European Working Party on Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Medicine (Baltimore) 1999;78:167–175. doi: 10.1097/00005792-199905000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Stoll T, Seifert B, Isenberg DA. SLICC/ACR Damage Index is valid, and renal and pulmonary organ scores are predictors of severe outcome in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Br J Rheumatol. 1996;35:248–254. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/35.3.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Bankier AA, Kiener HP, Wiesmayr MN, Fleischmann D, Kontrus M, Herold CJ, et al. Discrete lung involvement in systemic lupus erythematosus: CT assessment. Radiology. 1995;196:835–840. doi: 10.1148/radiology.196.3.7644652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Sant SM, Doran M, Fenelon HM, Breatnach ES. Pleuropulmonary abnormalities in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: assessment with high resolution computed tomography, chest radiography and pulmonary function tests. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 1997;15:507–513. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Matthay RA, Schwarz MI, Petty TL, Stanford RE, Gupta RC, Sahn SA, et al. Pulmonary manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus: review of twelve cases of acute lupus pneumonitis. Medicine (Baltimore) 1975;54:397–409. doi: 10.1097/00005792-197509000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Colby TV. Pulmonary pathology in patients with systemic autoimmune diseases. Clin Chest Med. 1998;19:587–612. vii. doi: 10.1016/s0272-5231(05)70105-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Min JK, Hong YS, Park SH, Park JH, Lee SH, Lee YS, et al. Bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia as an initial manifestation in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 1997;24:2254–2257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Filipek MS, Thompson ME, Wang P, Gosselin MV, Primack L. S Lymphocytic interstitial pneumonitis in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus: radiographic and high-resolution CT findings. J Thorac Imaging. 2004;19:200–203. doi: 10.1097/01.rti.0000099464.94973.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Carette S, Macher AM, Nussbaum A, Plotz PH. Severe, acute pulmonary disease in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: ten years of experience at the National Institutes of Health. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1984;14:52–59. doi: 10.1016/0049-0172(84)90009-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Zamora MR, Warner ML, Tuder R, Schwarz MI. Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage and systemic lupus erythematosus. Clinical presentation, histology, survival, and outcome. Medicine (Baltimore) 1997;76:192–202. doi: 10.1097/00005792-199705000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Todd DJ, Costenbader KH. Dyspnoea in a young woman with active systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2009;18:777–784. doi: 10.1177/0961203309104860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]