Abstract

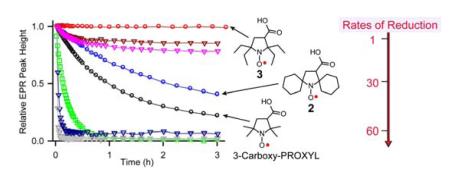

A series of sterically shielded pyrrolidine nitroxides were synthesized and their reduction by ascorbate (vitamin C) indicate that nitroxide 3 – a tetraethyl derivative of 3-carboxy-PROXYL – is reduced at the slowest rate among known nitroxides, i.e., at a 60-fold slower rate than that for 3-carboxy-PROXYL.

Nitroxide radicals have a wide range of applications in organic synthesis,1 materials chemistry,2,3 biophysics,4 and biomedicine.5 These applications rely on the stability, paramagnetic properties,6 and/or redox properties7 of the radicals at ambient conditions. While fast redox reactions of nitroxide radicals are favorable for many applications, fast in vivo reduction of paramagnetic nitroxide radicals to diamagnetic hydroxylamines by antioxidants, such as ascorbate (vitamin C) or enzymatic systems, hinder their applications in biomedicine.

3-Carboxy-PROXYL (1) (Figure 1) and its carboxylic acid derivatives are among the most commonly used nitroxides in vivo because of their resistance to reduction.9 However, their half-life is only ~2 min in the bloodstream and major organs, as determined by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies in mice.9 Therefore, their applications as paramagnetic contrast agents in MRI or in vivo spin labels are rather limited.10

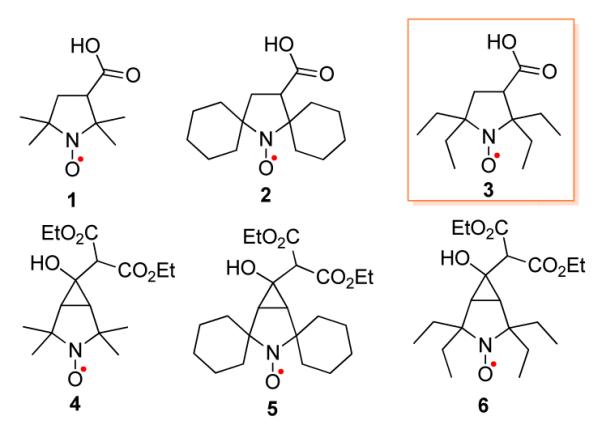

Figure 1.

Pyrrolidine nitroxides.

Recently, we reported the design and synthesis of an MRI contrast agent based upon macromolecular polyradicals derived from spirocyclohexyl nitroxide 2 (Figure 1).11,12 The agent possesses a comparatively long in vivo lifetime, high 1H water relaxivity (R1), and provides contrast-enhanced high resolution MRI in mice for over 1 hour.11

To further improve the development of organic based MRI contrast agents, we explore nitroxides that are more resistant to reduction than 2. It is well-established that the slower rate of reduction of nitroxides is associated with ring size, i.e. 5-membered (pyrrolidine) vs. 6-membered (piperidine) ring structures,9 as well as steric shielding of the nitroxide moiety.13,14 To search for nitroxides with increased resistance to reduction, we focus on a series of sterically shielded pyrrolidine nitroxides and their rate of reduction with ascorbate. Typically, the rate of reduction of a nitroxide by ascorbate in vitro provides a qualitative guideline to its expected half-life in vivo.11,14

Herein we report synthesis of sterically shielded pyrrolidine nitroxides 3 – 6 (Figure 1) and reduction kinetics of nitroxides 1 – 6 by ascorbate.

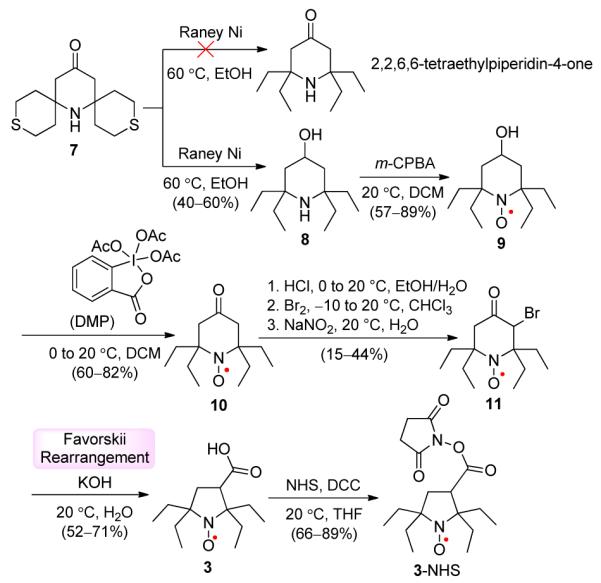

Synthesis of nitroxide 3 is outlined in Scheme 1. Starting from 7, we followed the desulfurization procedure using Raney Ni, which was previously reported to provide 2,2,6,6-tetraethylpiperidine-4-one in 15% yield.15 However, we found that the major product was alcohol 8,16 which could be obtained in about 50% yield using a larger excess of Raney Ni. We expected that, under similar conditions for preparation of Tempone (16),17 oxidation of 8 using m-CPBA would provide 10. Instead, we obtained 9,16 which was then oxidized further with Dess–Martin periodinane (DMP) to give ketone-nitroxide 10. By adapting the previously reported procedure for bromination of Tempone,18 11 was obtained by protonation of nitroxide 10, followed by bromination, and recovery of nitroxide with sodium nitrite. Nitroxide 11 in potassium hydroxide solution at 20 °C undergoes Favorskii rearrangement18 to give the target nitroxide 3. Treatment of 3 with N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) and N,N’-dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (DCC) in THF provides spin label 3-NHS in good yield.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of Nitroxides 3 and 3-NHS.a

a Isolated yields.

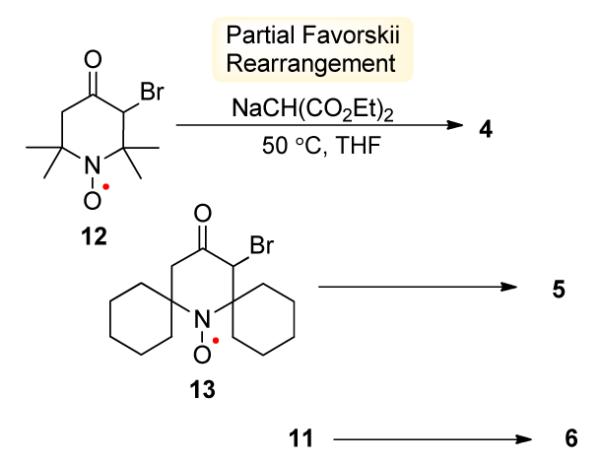

The synthesis of bicyclic pyrrolidine nitroxides is based on partial Favorskii rerrangement of 12 leading to 4.19 Sodium diethyl malonate is added to a solution of a bromoketone in anhydrous THF, and then the reaction mixture is stirred at 50 °C for 1.5 – 2.5 h, to produce bicyclic nitroxides 4 – 6 in about 50% isolated yields as mixtures of diastereomers (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of Nitroxides 4 – 6.

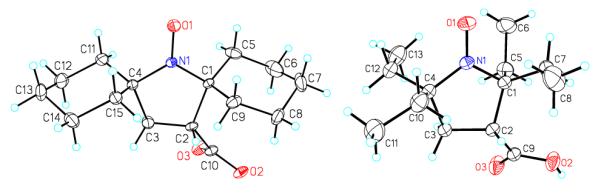

Structures of nitroxides 2 and 3 are confirmed by single-crystal X-ray analysis (Figure 2).20

Figure 2.

X-ray structures for nitroxide radicals 2 (left) and 3 (right). Carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen atoms are depicted with thermal ellipsoids set at the 50% probability level.

High purity of the bulk samples of nitroxides 3 – 6, as well as all other nitroxides used for kinetic studies, is determined by paramagnetic 1H NMR spectra and EPR spectroscopic spin concentrations.

EPR spectra of nitroxides 3 – 6 in chloroform show triplet patterns due to 14N hyperfine splitting, aN ≈ 14 – 16 Gauss, and g-values of about 2.006, similar to those for 1 and 2. For bicylic nitroxide 4, each of the triplet peaks is resolved into nonets, corresponding to coupling of 8 protons with 1H hyperfine splitting, aH ≈ 0.5 Gauss. This EPR splitting pattern is reproduced by DFT calculations,21 using simplified structures for cis and trans diastereomers, in which the diethylmalonate moiety is replaced with a methyl group. Specifically, each diastereomer has 8 protons with computed aH ≈ 0.5 Gauss, i.e., 2 protons at the bridghead and 6 protons in the methyls that are syn to the cyclopropane moiety.22

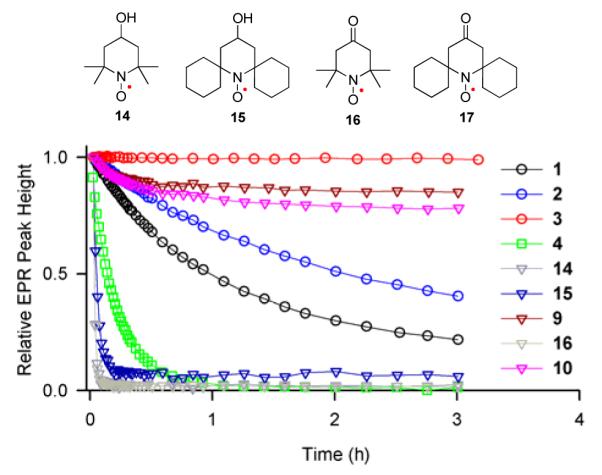

Rates of reduction for pyrrolidine nitroxides 1 – 6 are studied under pseudo-first order conditions using a 20-fold excess ascorbate in pH 7.4 PBS buffer. For comparison, the rates of reduction of the gem-dimethyl, spirocyclohexyl, and gem-diethyl piperidine nitroxides 9, 10, 14 – 179,14,23 are measured under identical conditions. Second order rate constants, k, are obtained by monitoring the decay of the low-field EPR peak height of nitroxides at 295 K (Figure 3 and Table 1). Also, decays of EPR single integrated peak height are examined and found to produce similar values of k for most nitroxides (Tables S5 and S6, SI).

Figure 3.

Reduction profiles of 0.2 mM nitroxides with 4 mM ascorbate in 25 mM PBS pH 7.4 at 295 K. (5, 6, and 17 have insufficient solubility to be included in the plot.)

Table 1.

Second order rate constants, k (M−1s−1), for initial rates of reduction of nitroxides (0.04 – 0.2 mM) with 20-fold excess ascorbate in 25 mM PBS pH 7.4 at 295 K.a

| pyrrolidine nitroxides | piperidine nitroxides | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| k | k | ||

| 1 | 0.063 ± 0.002 | 14 | 5.6 ± 0.2 |

| 2 | 0.031 ± 0.003 | 15 | 2.57 ± 0.03 |

| 3 | ≤0.001b | 9 | 0.039 ± 0.003 |

| 4 | 0.354 ± 0.006 | 16 | 6.32 ± 0.01 |

| 5 | 0.170 ± 0.004 | 17 | 3.2 ± 0.2 |

| 6 | 0.01 | 10 | 0.044 ± 0.002 |

Mean ± two standard deviations from at least three measurements; see: Tables S5 – S6 in the SI.

1 mM 3 with 20 or 100 mM ascorbate in 125 mM PBS.

The values of k for gem-dimethyl nitroxides 1, 14, and 16 in Table 1, which may be compared to the corresponding k = 0.06, 5.46, 5.78 M−1s−1 at 293 K reported by Rigo,23 reflect a well-known finding that 5-membered ring nitroxides are reduced at relatively slower rates, compared to 6-membered ring nitroxides. The gem-dimethyl bicyclic nitroxide 4 (k = 0.354 M−1s−1) is reduced at a significantly faster rate than 1 (Figure 3). The spirocyclohexyl nitroxides 2, 5, 15, and 17 are reduced at rates that are about two times slower than those for the corresponding gem-dimethyl nitroxides. The rates of reduction for gem-diethyl nitroxides 3, 6, 9, and 10 are decreased by another factor of 20–70, compared to the spirocyclohexyl nitroxides.

gem-Diethyl pyrrolidine nitroxides 3 (k ≤ 0.001 M−1s−1) and 6 (k ≈ 0.01 M−1s−1) are reduced at significantly slower rates, compared to previously reported nitroxides, including 5-membered ring nitroxides shielded with gem-diethyl groups, such as 3,4-dimethyl-2,2,5,5-tetraethylperhydroimidazol-1-yloxy (k = 0.02 M−1s−1).13 As illustrated in Figure 3, 0.2 mM nitroxide 3 in the presence of a 20-fold excess of ascorbate shows no detectable decay over 3 hours. Only when much higher concentrations of 3 and ascorbate are used, the reduction becomes detectable (Figure 4); for 1 mM 3 treated with 20 mM and 100 mM ascorbate, the EPR signal of nitroxide 3 decreases by only 5 and 15%, respectively, after 3 hours.

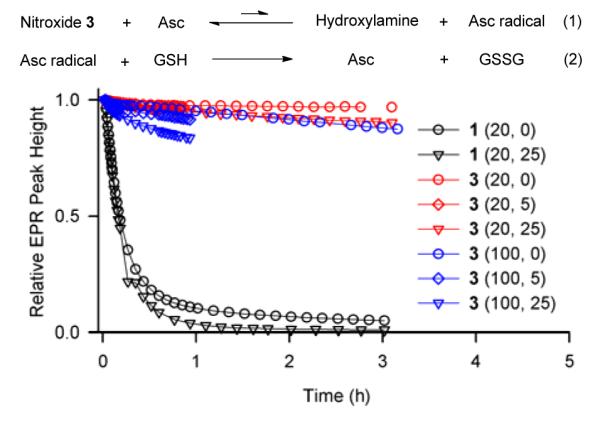

Figure 4.

Reduction profiles of 1.0 mM nitroxides in 125 mM PBS pH 7.4 at 295 K. Concentrations of ascorbate (20 or 100 mM) and GSH (0, 5, or 25 mM) are indicated for each experiment.

The reduction profiles (Figure 4) suggest that the slow rate at the initial stage of the reaction (k ≈ 0.001 M−1s−1, Table 1) is followed by slower decay of the EPR signal in the later stage. This observation may be interpreted as initial slow reaction of ascorbate with nitroxide, which produces hydroxylamine and ascorbate radical, reaching an “equlibrium” (Figure 4, eq. 1). The equilibrium is shifted toward hydroxylamine by slow decay of ascorbate radical via known multi-step mechanism.13,24 Addition of reduced glutathione (GSH), which is known to scavenge ascorbate radical with k ≈ 10 M−1s−1 or dehydroascorbate (disproportionation product of ascorbate radical),13,24,25 leads to higher conversion of nitroxide to hydroxylamine. This effect is more pronounced at higher concentrations of ascorbate (Figure 4). In the absence of ascorbate, GSH does not reduce stable nitroxides (Figure S5, SI), and the initial rates of the reduction of studied nitroxides with ascorbate are only slightly increased by addition of GSH (Table S6, SI).

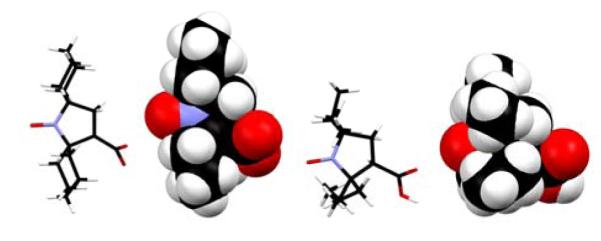

The slow rate of reduction of 3 compared to that of 2 may be related to increased steric shielding of the nitroxide moiety by gem-diethyl vs. spirocyclohexyl groups, as shown by the space-filling plots of the X-ray structures (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Stick and space-filling plots for X-structures of 2 (left) and 3 (right). Carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen atoms are colored in black, blue, and red, respectively.

For further insight into the structure of 5-membered ring nitroxides, geometries of 1 – 3 were optimized at the UB3LYP/6-311+G(d,p)+ZPVE level of theory;21 for 4 – 6, simplified structures for cis and trans diastereomers, in which the diethylmalonate moiety is replaced with a methyl group, are computed at the same level of theory. Space-filling plots for these DFT-computed nitroxides suggest that steric shielding of the nitroxide moiety increases from gem-dimethyl to spirocyclohexyl to gem-diethyl (Figure S6, SI). Also, steric shielding is more effective in 1 – 3, compared to the simplified structures of 4 – 6 (Figure S7, SI).26 Thus, the experimentally observed rate constants for reduction of 1 – 6 by ascorbate may be qualitatively correlated with steric shielding of the NO moiety in pyrrolidine nitroxides.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank the National Science Foundation and National Institutes of Health for support of this work through Grants CHE-1012578 and NIBIB EB008484. We thank Molly Sowers for her help with the synthesis of 3.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Complete acknowledgment, reference 21, experimental and computational details, and CIF files. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- (1).Tebben L, Studer A. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011;50:5034–5068. doi: 10.1002/anie.201002547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Ratera I, Veciana J. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012;41:303–349. doi: 10.1039/c1cs15165g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Lahti PM. Adv. Phys. Org. Chem. 2011;45:93–169. [Google Scholar]

- (3).Nishide H, Oyaizu K. Science. 2008;319:737–738. doi: 10.1126/science.1151831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Reginsson GW, Schiemann O. Biochem J. 2011;434:353–363. doi: 10.1042/BJ20101871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Burks SR, Makowsky MA, Yaffe ZA, Hoggle C, Tsai P, Muralidharan S, Bowman MK, Kao JPY, Rosen GM. J. Org. Chem. 2010;75:4737–4741. doi: 10.1021/jo1005747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6)(a).Dane EL, Griffin RG, Swager TM. Org. Lett. 2009;11:1871–1874. doi: 10.1021/ol9001575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Rajca A, Mukherjee S, Pink M, Rajca S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:13497–13507. doi: 10.1021/ja063567+. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Olankitwanit A, Kathirvelu V, Rajca S, Eaton GR, Eaton SS, Rajca A. Chem. Commun. 2011;47:6443–6445. doi: 10.1039/c1cc11172h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Zagdoun A, Casano G, Ouari O, Lapadula G, Rossini AJ, Lelli M, Baffert M, Gajan D, Veyre L, Maas WE, Rosay M, Weber RT, Thieuleux C, Coperet C, Lesage A, Tordo P, Emsley L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:2284–2291. doi: 10.1021/ja210177v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7)(a).Oyaizu K, Nishide H. Adv. Mater. 2009;21:2339–2344. [Google Scholar]; (b) Gryn’ova1 G, Barakat JM, Blinco JP, Bottle SE, Coote ML. Chem. – Eur. J. 2012;18:7582–7593. doi: 10.1002/chem.201103598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Keana JFW, Pou S, Rosen GM. Magn. Res. Med. 1987;5:525–536. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910050603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Hyodo F, Matsumoto K, Matsumoto A, Mitchell JB, Krishna MC. Cancer Res. 2006;66:9921–9928. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10)(a).Davis RM, Sowers AL, DeGraff W, Bernardo M, Thet-ford A, Krishna MC, Mitchell JB. Free Radical Biol. Med. 2011;51:780–790. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.05.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Khan N, Blinco JP, Bottle SE, Hosokawa K, Swartz HM, Micallef AS. J Magn Reson. 2011;211:170–177. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2011.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Rajca A, Wang Y, Boska M, Paletta JT, Olankitwanit A, Swanson MA, Mitchell DG, Eaton SS, Eaton GR, Rajca S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:15724–15727. doi: 10.1021/ja3079829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Kirilyuk IA, Polienko YF, Krumkacheva OA, Strizhakov RK, Gatilov YV, Grigor’ev IA, Bagryanskaya EG. J. Org. Chem. 2012;77:8016–8027. doi: 10.1021/jo301235j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13)(a).Marxa L, Chiarellia R, Guiberteaub T, Rassat A. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1. 2000:1181–1182. [Google Scholar]; (b) Bobko AA, Kirilyuk IA, Grigor’ev IA, Zweier JL, Khramtsov VV. Free Radical Biol. Med. 2007;42:404–412. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Emoto M, Mito F, Yamasaki T, Yamada K, Sato-Akaba H, Hirata H, Fujii H. Free Radical Res. 2011;45:1325–1332. doi: 10.3109/10715762.2011.618499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Sakai K, Yamada K, Yamasaki T, Kinoshita Y, Mito F, Utsumi H. Tetrahedron. 2010;66:2311–2315. [Google Scholar]

- (16).Wetter C, Gierlich J, Knoop CA, Müller C, Schulte T, Studer A. Chem. – Eur. J. 2004;10:1156–1166. doi: 10.1002/chem.200305427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Cella JA, Kelley JA, Kenehan EF. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1974:943–943. [Google Scholar]

- (18).Sosnovsky G, Cai Z. J. Org. Chem. 1995;60:3414–3418. [Google Scholar]

- (19).Babič A, Pečar S. Synlett. 2008:1155–1158. [Google Scholar]

- (20).X-ray structure of 17 is described in the Supporting Information.

- (21).Frisch MJ, et al. Gaussian 09. Revision A.01 Gaussian; Wallingford, CT: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- (22).Computed 1H hyperfine splitting within each syn methyl averages to ∣aH∣ ≈ 0.5 Gauss. All other gem-dimethyls have significantly smaller values of average ∣aH∣ (Table S9, Supporting Information).

- (23).Vianello F, Momo F, Scarpa M, Rigo A. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 1995;13:219–226. doi: 10.1016/0730-725x(94)00121-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Bielski BHJ, Allen AO, Schwarz HA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1981;103:3516–3518. [Google Scholar]

- (25).Winkler BS, Orselli SM, Rex TS. Free Rad. Biol. Med. 1994;17:333–349. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(94)90019-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Space-filling plots suggest that α-alkylation of malonate moiety in the cis isomer of 4 – 6 may significantly increase steric shielding of nitroxide moiety.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.