Abstract

We report a molecular design that provides an intravenously injectable organic radical contrast agent (ORCA) that has molecular r1 ≈ 5 mM−1s−1. The ORCA is based on spirocyclohexyl nitroxide radicals and polyethylene glycol chains conjugated to a generation 4 polypropylenimine dendrimers scaffold. The metal-free ORCA has a long shelf-life and provides selectively enhanced MRI in mice for over 1 h.

Paramagnetic organic radicals, such as stable nitroxides, have been investigated as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) contrast agents.1–6 Metal-free, organic radical contrast agent (ORCA) would provide an alternative to gadolinium-based contrast agents (GBCAs), which are the most widely used paramagnetic metal ion-based agents in the clinic. Although GBCAs are well tolerated by the majority of patients, patients with impaired kidney function are reported to be at increased risk of developing a serious adverse reaction named nephrogenic systemic fibrosis (NSF).7 Since the first report on this adverse effect in renal-dialysis patients and its association with gadolinium,8,9 guidelines on the administration of GBCAs have been issued and implemented worldwide to minimize the risk for NSF.

To date, the critical obstacle in the development of a practical ORCA for MRI is the design and synthesis of paramagnetic compounds of moderate molecular size that possess long in vivo lifetime, high 1H water relaxivity (r1), and high water solubility.1–6

Commonly used, paramagnetic nitroxides undergo fast reduction in vivo, especially in the bloodstream and tissues, to diamagnetic hydroxylamines.2,3 For example, 3-carboxy- 2,2,5,5-tetramethyl-l-pyrrolidinyloxy (3-CP) (Scheme 1) and its derivatives, which are among the most widely used and most resistant to reduction nitroxide radicals, have a short half-life (ca. 2 min) in the bloodstream and kidneys, as determined by MRI mouse studies.2,3 Although nitroxides with one unpaired electron, total spin quantum number, S = ½, possess low 1H water relaxivity,10 e.g. r1 ≈ 0.15 mM−1s−1 at 7 T for 3-CP, they have been utilized as functional redox-sensitive agents in MRI studies, and as in vivo radioprotectors. 2,3,11 In principle, r1 could be increased by conjugation of paramagnetic metal chelates or radicals to rigid scaffolds.12–14 However, previous examples of conjugation of nitroxides to dendrimers did not provide increased r1,15,16 as shown in the case of the generation 3 (G3) polypropylenimine (PPI) dendrimers conjugated with nitroxides 3-CP which has r1 ≈ 0.16 mM−1s−1 at 1.5 T, similar to that for common nitroxides. Despite low r1 and low solubility in water,15 in vivo MR images of the rabbit stifle joints, obtained by intraarticular administration of these agents, showed significant enhancement of articular cartilage in T1-weighted images.1 Fast reduction and low r1 of nitroxides pose serious obstacles because they severely limit available MR imaging time and contrast, while increasing dose of the agent to compensate for reduction and low r1 could lead to oxidative stress.17 A practical ORCA, especially suitable for intravenous injection, remains elusive.

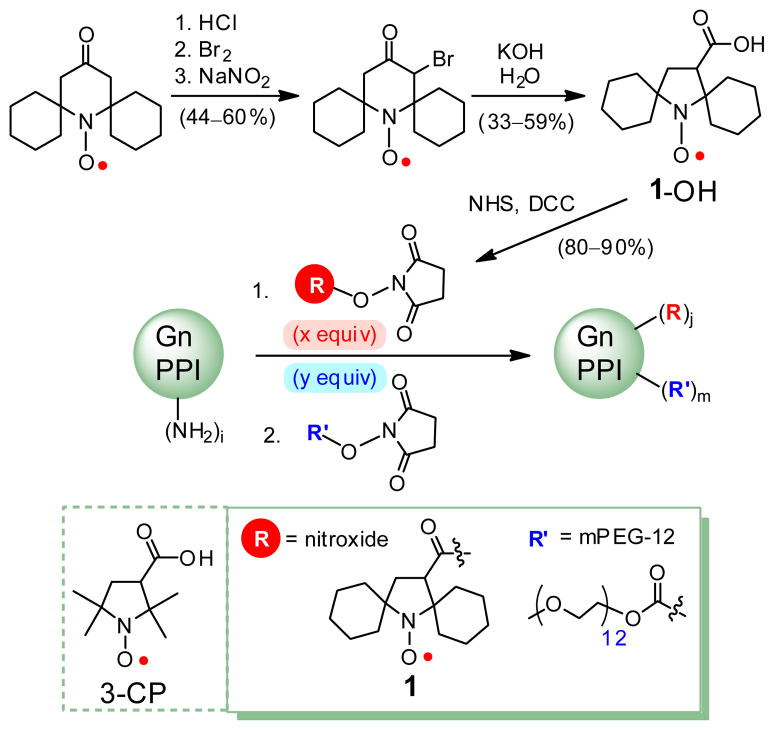

Scheme 1.

We report a water-soluble ORCA with long in vivo lifetime and high r1 that provide selectively enhanced MRI in mice for over 1 h.

Our approach to the design of ORCA relies on spirocyclohexyl nitroxide radical 1-OH (Figure. 1). The 5-membered ring (pyrrolidinyl) nitroxide radical18,19 that is sterically shielded20 by the spirocyclohexyl groups21 is expected to be reduced at a slower rate in vivo, particularly by antioxidants such as ascorbate (vitamin C). Through judicious molecular design, conjugation of nitroxide radicals to a rigid scaffold should provide an agent with not only increased resistance to reduction but also with increased relaxivity. We consider dendrimers (branched structures), which have been demonstrated to be more effective as scaffold for linking Gd-chelates than linear structures in the approaches to increased relaxivity of GBCAs.13,14,22 Because hydrophobicity of nitroxide- covered dendrimer surface may contribute to limited applications of the agents in MRI, our approach is aimed at alleviating that effect by including water solubilizing groups such as polyethylene glycol (PEG) chains on the surface of the dendrimer. The non-immunogenic and polar PEG chains may provide additional advantages,23 that is, the PEG chains may help to immobilize nitroxides as well as increase water access to the paramagnetic nitroxides that could help to increase r1. Our design strategy is to optimize the ratio of nitroxide and PEG chains on the dendrimer surface to obtain ORCA with high r1 and good water solubility. This concept is tested using PPI dendrimer conjugated with spirocyclohexyl nitroxide 1 and hydrophilic, monodisperse methoxypolyethylene glycol (mPEG-12) chains to obtain water soluble ORCA.

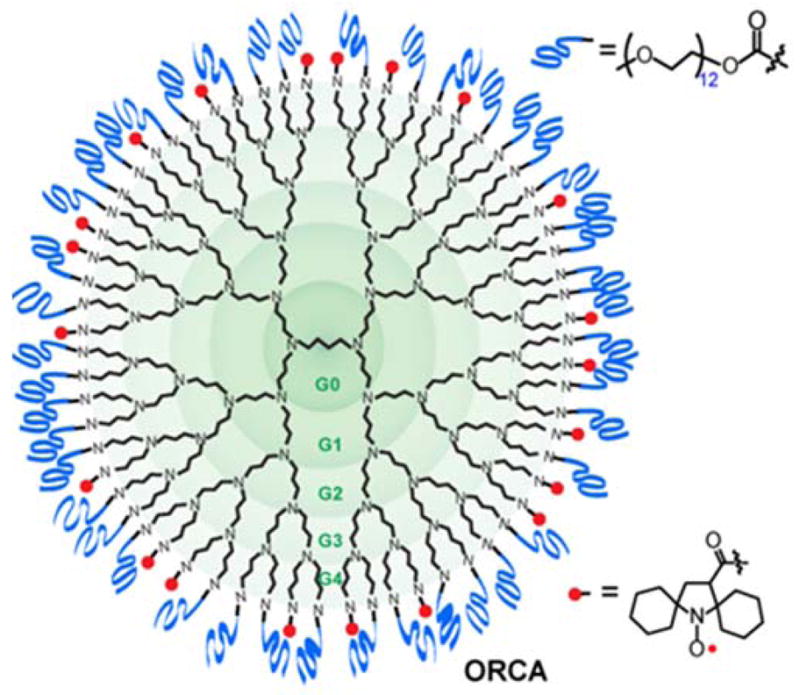

Figure 1.

Organic radical contrast agent (ORCA).

The spirocyclohexyl nitroxide 1-OH is synthesized by modification of methods for 3-CP,24 and then the carboxylic acid is converted to N-hydroxysuccinimidyl (NHS) ester, 1-NHS, using standard methods. Sequential conjugation of 1-NHS, and mPEG-12-NHS to PPI dendrimer generation-4 (PPI-G4) with 64 terminal amine groups ((NH2)i, i = 64) provides ORCA 1-mPEG-G4. Through tests of various reaction conditions, it was determined that using about 1/3 stoichiometric amount (1/3 equiv) of 1-NHS and an excess of 2/3 equiv of mPEG-12-NHS is optimum. The resultant 1-mPEG-G4 has water solubility ≥0.5 g/mL and radical concentration ≥0.4 mmol/g. ORCAs 1-mPEG-G3, 1-mPEG-G2, and 1-mPEG-G0, as well as 3-CP-mPEG-G4 are prepared by analogous procedure (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of ORCAs.

| PPI | i | ORCA | x (equiv) | y (equiv) | Spin Conc. (mmol g−1) | r1 (mM−1s−1)a | τrot (ns) | j | m | (R′)m/(R)j | Surface Coverage (%) | Mn (kDa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G4 | 64 | 1-mPEG-G4 | 21–22 | 54–65 | 0.41 ± 0.01 | 0.42 ± 0.03 | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 13.1 ± 0.5 | 37.9 ± 2.0 | 2.90 ± 0.04 | 79.6 ± 4.0 | 32 |

| G3 | 32 | 1-mPEG-G3 | 11 | 25 | 0.46 ± 0.01 | 0.37 ± 0.02 | 0.84 ± 0.06 | 8 | 20 | 2.5 | 86 | 17 |

| G2 | 16 | 1-mPEG-G2 | 6 | 15 | 0.46 ± 0.04 | 0.29 ± 0.02 | 0.49 ± 0.02 | 4 | 10 | 2.5 | 90 | 8.4 |

| 1-G4 | 70–80 | 0 | 2.36 ± 0.03 | - | - | 41 ± 1 | 0 | 0 | 64 ± 2 | 17 | ||

| G4 | 64 | mPEG-G4 | 0 | 70 | 0 | - | - | 0 | 59 | - | 92 | 41 |

| 3-CP-mPEG-G4 | 21 | 52 | 0.50 ± 0.05 | 0.33 | 0.85 ± 0.07 | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| 3-CP | - | - | - | 0.14 | 0.045 | - | - | - | - | - |

r1 (mM−1s−1): mM−1 of S = ½ nitroxide radical (per S = ½ nitroxide radical); i is number of NH2 groups; x and y are molar equivalents of nitroxide- NHS and mPEG-12-NHS; j and m are number of conjugated nitroxide radicals (R) and mPEG-12 (R′) - see Scheme 1.

The number of conjugated spirocyclohexyl nitroxide 1 and mPEG-12 moieties per PPI dendrimer core is determined using end group analysis based upon 1H NMR spectroscopy and spin counting by EPR spectroscopy. Because 1H NMR spectra of paramagnetic ORCAs are broad, and not useful for characterization, we convert the nitroxides to diamagnetic hydroxylamines by treating the ORCAs with excess of ascorbate. The partially reduced ORCAs provide sufficiently well resolved 1H NMR spectra for determination of the number of conjugated mPEG-12 (m), by the relative integrals of 1H resonances for the terminal methyl groups of mPEG-12 and the 1H resonances of the dendrimer scaffold. Spin counting provides the spin concentration of the ORCA sample (prior to treatment with ascorbate), which can be used to determine the number of conjugated nitroxide radicals (j). The PPI dendrimer surface coverage determined from the values of m and j is shown in Table 1. For 1-mPEG-G4, about 80% of the dendrimer surface is covered with nitroxides 1 and mPEG-12 and this surface coverage increases to about 90% for lower generations of ORCA. This incomplete surface coverage may be associated with well-known overcrowding on the surfaces of the higher generation dendrimers25 that is further amplified by larger space requirements of spirocyclic nitroxide vs. mPEG-12, as illustrated by the surface coverage of 64% and 92% for model compounds 1-G4 and mPEG-G4. Covalent attachment of both mPEG-12 and the reduced nitroxides (hydroxylamines) to the scaffold is evidenced by two broad 1H NMR peaks at δ 7.9 and δ 10.4 ppm (dimethylsulfoxide-d6), assigned to two distinct NH amide groups. mPEG-G4 has only one type of NH amide group (singlet at δ 7.9 ppm), which shows a 1H-1H COSY cross-peak to the dendrimer backbone (Figures S10–S18).

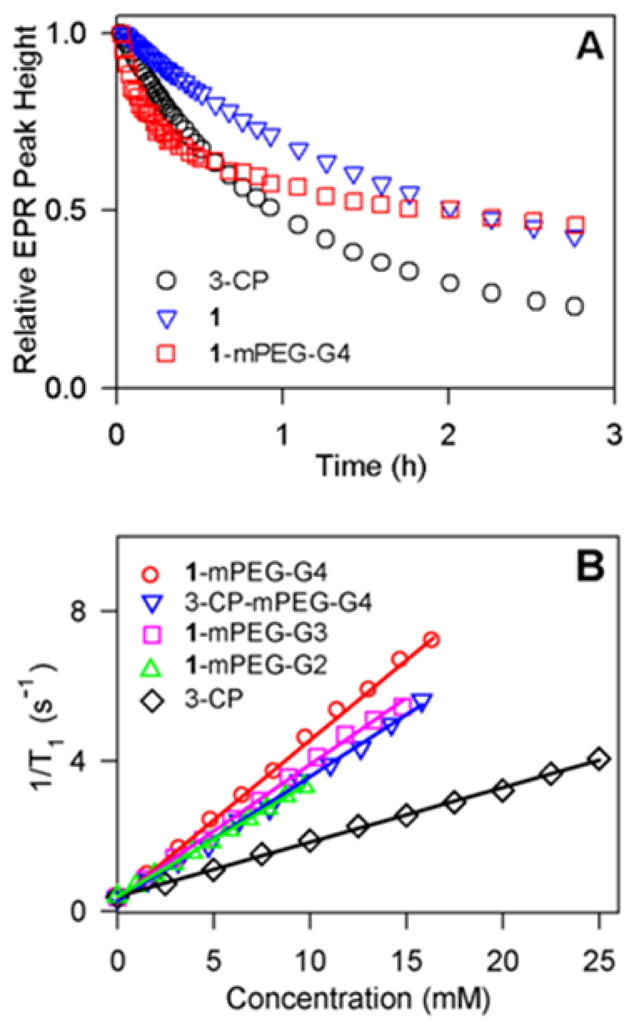

We investigate the rate of reduction of nitroxides 1-OH and ORCA 1-mPEG-G4 under pseudo-first order conditions using 20-fold excess ascorbate in pH 7.4 PBS buffer. As reference, the rate of reduction of 3-CP is determined under identical conditions. Second order rate constants, k, are obtained by following the decay of the nitroxide EPR peak height at 295 K (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

(A) Reduction of 0.2 mM nitroxide radicals with 4 mM ascorbate in 125 mM PBS pH 7.4 at 295 K. (B) Plots of water 1H relaxation rates, 1/T1, vs. concentration of nitroxide radicals in PBS pH 7.2; water relaxivities r1 determined from slopes of the linear fits (R2 = 0.998–0.999).

The spirocyclohexyl nitroxide, 1-OH (k = 0.031 ± 0.003 M−1s−1) is reduced at a significantly slower rate than 3-CP (k = 0.063 ± 0.002 M−1s−1).19 Under similar conditions, initial reduction of 1-mPEG-G4 occurs with the rate constant, k = 0.058 ± 0.004 M−1s−1, which is comparable to that of 3-CP. However, after a fraction of nitroxides is reduced during the initial 1-h period, the remaining nitroxides 1 on the crowded dendrimer surface are reduced at about 20-fold slower rate (Table S2).

1H water relaxivity r1 of ORCAs and 3-CP in PBS buffer are measured using a 7-T MRI scanner. The plots of 1/T1 (1H relaxation rate of water) vs. nitroxide concentration are linear for all agents, indicating the absence of aggregation in the concentration range studied, 0–16 mM (per-nitroxide) (Fig. 2B). The slopes of the plots indicate that, under physiological conditions (PBS, pH 7.2), 1H water relaxivity of PEGylated ORCAs is significantly higher than for 3-CP. For example, r1 = 0.42 ± 0.03 mM−1s−1 per S = ½ nitroxide radical in 1-mPEGG4, corresponding to molecular r1 ≈ 5 mM−1s−1, may be compared to 3-CP with r1 ≈ 0.14 mM−1s−1 (Table 1). Solutions of 1- mPEG-G4 in PBS buffer are stable at room temperature, with r1 showing negligible change over 24 h; similarly, no change is detected in spin concentration by EPR spectroscopy for 1- mPEG-G4 in PBS buffer stored at −20 °C for 5 months.

We examine rotational dynamics of the ORCA by EPR line-shape analysis. Because high spin concentration leads to exchange broadening of EPR spectra, we decrease spin concentration of ORCA, by treatment with ascorbate in PBS buffer, to obtain adequately resolved EPR spectra for the analysis. Simulations of the EPR spectra of the partially reduced ORCAs provide rotational correlation time (τrot) in the ns-range (Table 1), compared to τrot = 0.045 ns for 3-CP under identical conditions. The value of τrot for 1-mPEG-G4 is about 50% longer than that for 3-CP-mPEG-G4, emphasizing the effectiveness of the spirocyclohexyl, and thus more rigid, structure of nitroxide 1 in restricting the motion of the radical. Although the ORCA with the longest τrot = 1.5 ± 0.1 ns possesses the highest r1, the relaxivity is only weakly dependent on τrot. This suggests the possibility of different factors limiting r1 for the ORCAs, such as short electron spin relaxation time T1e and long residence/exchange time (τexch) of water molecule hydrogen-bonded to the nitroxide radical.

EPR line-shape analyses for 1-mPEG-G4, -G3, and -G2 suggest that T1e is longer than about 20 ns, based upon the assumption T1e > T2e estimated from linewidths. Because the dominant mechanism for shortening of T1e is by the modulation of electron-electron spin-spin interaction by motion,26 the highly restricted motion of the radicals in the ORCAs (τrot ≈ 1 ns) is likely to prevent T1e from becoming sufficiently short, to affect water r1 significantly (Figure S22). This leaves long τexch as the most probable factor limiting water r1, similar to the behavior observed in conjugates of Gd-chelates with dendrimers.27 The dipolar inner sphere model,28 which is the standard in the analysis of Gd-chelates,13,22 predicts that shortened τexch ≤ 1 μs, i.e., improved access of water to radicals, should facilitate increased water r1. For example, r1 ≈ 5 mM−1s−1 per S = ½ nitroxide radical is computed for τexch ≈ 1 μs, τrot ≈ 1.5 ns, and T1e ≥ 20 ns (Figure S22).

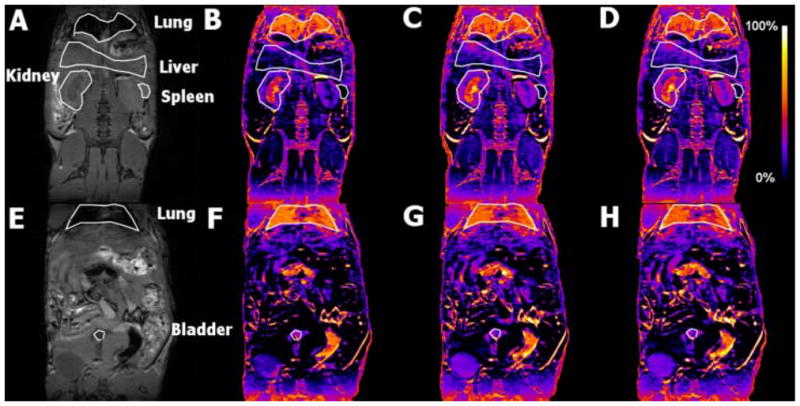

To explore the potential of ORCAs as practical MRI contrast agents, we investigate 1-mPEG-G4 in vivo. Since the r1 per S = ½ nitroxide radical for 1-mPEG-G4 is about 3 times higher than for a typical nitroxide, we used a relatively small dose of radical, 0.5 mmol/kg, which is 3 times less than the typical dose for common nitroxides in in vivo MRI studies.2,3 The T1 weighted high resolution 3D images of the mouse torso show that the 1-mPEG-G4 is a long lasting blood pool contrast agent, which is slowly excreted through the kidneys (Figures 3, 4, and Fig. S25). This can be appreciated in the subtraction images shown in Figure 3B–D, F–H. It is clear that the liver and spleen show no appreciable uptake, only residual signal as a result of the vasculature, while the lung, normally a low intensity organ in MRI, lights up due to the enhancement of the vasculature.

Figure 3.

3D T1 weighted spoiled gradient recalled echo MRI of mouse before and after injection of 1-mPEG-G4. (A,E) MRI before injection and (B–D,F–H): subtraction of preinjection images from images obtained (B,D) 0–30 min, (C,E) 30–60 min, and (D,H) 60–90 min after injection.

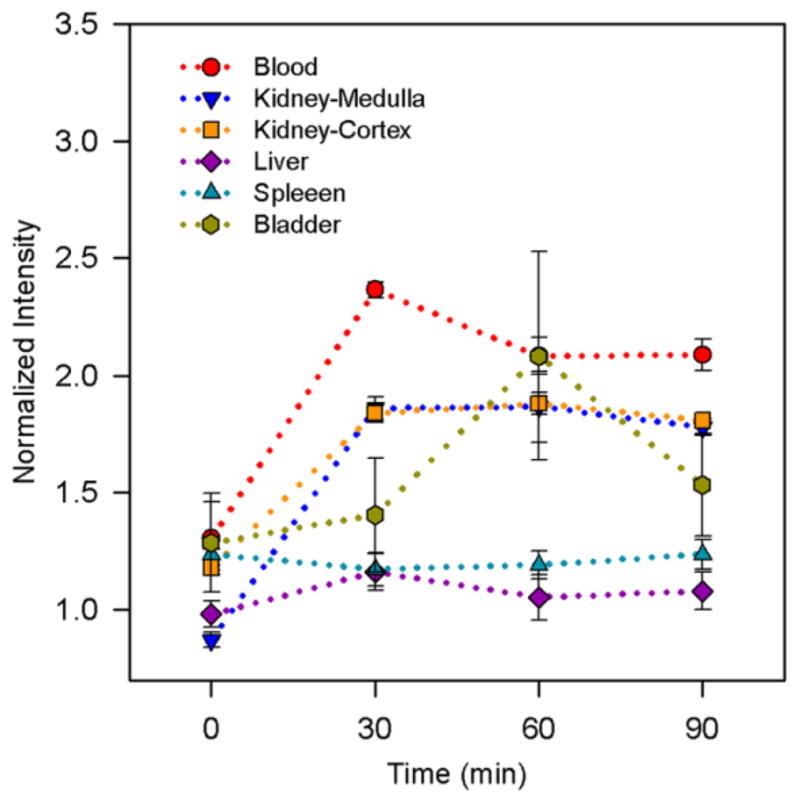

Figure 4.

Plots of normalized intensities (mean ± standard errors, n = 3) before and after injection of 1-mPEG-G4.

The MRI signal in blood and kidneys decays gradually allowing for a long imaging time. For example, the image enhancement (mean ± standard deviations, n = 3) in kidneys medulla and blood vessels is 114 ± 14% and 81 ± 27% after 30 min following administration of the agent and slowly decreases to 104 ± 11% and 60 ± 26% after 90 min of scanning, respectively (Figure 4).

Although the present data do not allow for quantitation of the excretion of the agent, selective uptake by the kidneys medulla and cortex, and the enhanced image of the bladder (Figure 3), suggest excretion of ORCA through the kidneys. ORCA 1-mPEG-G4, with average Mn ≈ 32 kDa (Table 1), is estimated to have a Stokes-Einstein radius (rSE) of about 2.4 nm, which is near the upper limit, rSE ≈ 2.5 nm, for glomerular filtration of positively charged spherical solutes,29 and could thus account for strongly enhanced MR image of kidneys, especially medulla, over a period exceeding 1 h (Table 1).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Przemysław J. Boratyński and Krzysztof Waskiewicz for preliminary synthesis of 1-mPEG-G4. This research was supported by NSF CHE-1012578 (UNL), NIH NIBIB EB008484 (UNL), Nebraska Research Initiative (UNL and UNMC), and NIH NIBIB EB002807 (Denver).

Footnotes

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Materials, general methods, instrumentation, synthetic protocols, in vitro and in vivo characterizations. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Winalski CS, Shortkroff S, Schneider E, Yoshioka H, Mulkern RV, Rosen GM. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage. 2008;16:815–822. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2007.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hyodo F, Matsumoto K, Matsumoto A, Mitchell JB, Krishna MC. Cancer Res. 2006;66:9921–9928. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davis RM, Matsumoto S, Bernardo M, Sowers A, Matsumoto K, Krishna MC, Mitchell JB. Free Rad Biol Med. 2011;50:459–468. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.11.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Utsumi H, Yamada K, Ichikawa K, Sakai K, Kinoshita Y, Matsumoto S, Nagai M. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:1463–1468. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510670103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gallez B, Lacour V, Demeure R, Debuyst R, Dejehet F, De Keyser JL, Dumont P. Magn Reson Imag. 1994;12:61–69. doi: 10.1016/0730-725x(94)92353-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brasch RC, London DA, Wesbey GE, Tozer TN, Nitecki DE, Williams RD, Doemeny J, Tuck LD, Lallemand DP. Radiology. 1983;147:773–779. doi: 10.1148/radiology.147.3.6844613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Braverman IM, Cowper S. F1000 Med Reports. 2010;2:84. doi: 10.3410/M2-84. http://f1000.com/reports/m/2/84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grobner T. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21:1104–1108. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfk062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marckmann P, Skov L, Rossen DA, Damholt MB, Heaf JG, Thomsen HS. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:2359–2362. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006060601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vallet P, Van Haverbeke Y, Bonnet PA, Subra G, Chapat JP, Muller RN. Magn Reson Med. 1994;32:11–15. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910320103.S = 1 nitroxide diradicals have similarly low r1 (per nitroxide moiety): Spagnol G, Shiraishi K, Rajca S, Rajca A. Chem Commun. 2005:5047–5049. doi: 10.1039/b508094k.

- 11.Davis RM, Sowers AL, DeGraff W, Bernardo M, Thetford A, Krishna MC, Mitchell JB. Free Radical Biol Med. 2011;51:780–790. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.05.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chan HC, Sun K, Magin RL, Swartz HM. Bioconjugate Chem. 1990;1:32–36. doi: 10.1021/bc00001a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Villaraza AJL, Bumb A, Brechbiel MW. Chem Rev. 2010;110:2921–2959. doi: 10.1021/cr900232t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Floyd WC, III, Klemm PJ, Smiles DE, Kohlgruber AC, Pierre VC, Mynar JL, Fréchet JMJ, Raymond KN. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:2390–2393. doi: 10.1021/ja110582e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Winalski CS, Shortkroff S, Mulkern RV, Schneider E, Rosen GM. Magn Res Med. 2002;48:965–972. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Francese G, Dunand FA, Loosli C, Merbach AE, Decurtins S. Magn Reson Chem. 2003;41:81–83. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Silberstein T, Mankuta D, Shames AI, Likhtenshtein GI, Meyerstein D, Meyerstein N, Saphier O. Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 2008;277:233–237. doi: 10.1007/s00404-007-0439-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keana JF, Pou S, Rosen GM. Magn Reson Med. 1987;5:525–536. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910050603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vianello F, Momo F, Scarpa M, Rigo A. Magn Reson Imaging. 1995;13:219–226. doi: 10.1016/0730-725x(94)00121-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bobko AA, Kirilyuk IA, Grigor’ev IA, Zweier JL, Khramtsov VV. Free Radical Biol Med. 2007;42:404–412. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kirilyuk IA, Polienko YF, Krumkacheva OA, Strizhakov RK, Gatilov YV, Grigor’ev IA, Bagryanskaya EG. J Org Chem. 2012;77 doi: 10.1021/jo301235j. ASAP: 08/23/2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Caravan P. Chem Soc Rev. 2006;35:512–523. doi: 10.1039/b510982p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Joralemon MJ, McRae S, Emrick T. Chem Commun. 2010;46:1377–1393. doi: 10.1039/b920570p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sosnovsky G, Cai Z. J Org Chem. 1995;60:3414–3418. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Newkome GR, Moorefield CN, Vögtle F. Dendrimers and Dendrons. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim: 2001. pp. 1–623. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sato H, Kathirvelu V, Spagnol G, Rajca S, Rajca A, Eaton SS, Eaton GR. J Phys Chem B. 2008;112:2818–2828. doi: 10.1021/jp073600u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nicolle GM, Toth E, Schmitt-Willich H, Raduchel B, Merbach AE. Chem Eur J. 2002;8:1040–1048. doi: 10.1002/1521-3765(20020301)8:5<1040::aid-chem1040>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maliakal AJ, Turro NJ, Bosman AW, Cornel J, Meijer EW. J Phys Chem A. 2003;107:8467–8475. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Haraldsson B, Sörensson J. Physiology. 2004;9:7–10. doi: 10.1152/nips.01461.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.