Abstract

Context

There is limited information on the prevalence and correlates of bipolar spectrum disorder in international population-based studies using common methodology.

Objective

To describe the prevalence, impact, patterns of comorbidity, and patterns of service utilization for bipolar spectrum disorder in the WHO World Mental Health survey (WMH) initiative.

Design

Cross-sectional face-to-face household surveys

Participants

61,392 community adults in 11 countries in the Americas, Europe, and Asia

Main Outcome Measure

DSM-IV disorders, severity, and treatment assessed with the World Mental Health version of the WHO Composite International Diagnostic Interview (WMH CIDI 3.0), a fully-structured lay-administered psychiatric diagnostic interview.

Results

The aggregate lifetime prevalence of BP-I disorder was 0.6%, BP-II was 0.4%, subthreshold BP was 1.4%, and Bipolar Spectrum (BPS) was 2.4%. Twelve-month prevalence of BP-I disorder was 0.4%, BP-II was 0.3%, subthreshold BP was 0.8%, and BPS was 1.5%. Severity of both manic and depressive symptoms, and suicidal behavior increased monotonically from subthreshold BP to BP-I. By contrast, role impairment was similar across bipolar subtypes. Symptom severity was greater for depressive than manic episodes, with approximately 75% of respondents with depression and 50% of respondents with mania reporting severe role impairment. Three-quarters of those with BPS met criteria for at least one other disorder, with anxiety disorders, particularly panic attacks, being the most common comorbid condition. Less than half of those with lifetime BPS received mental health treatment, particularly in low-income countries where only 25% reported contact with the mental health system.

Conclusions

Despite cross-site variation in the prevalence rates of bipolar spectrum disorder, the severity, impact, and patterns of comorbidity were remarkably similar internationally. The uniform increases in clinical correlates, suicidal behavior and comorbidity across each diagnostic category provide evidence for the validity of the concept of a bipolar spectrum. BPS treatment needs are often unmet, particularly in low-income countries.

INTRODUCTION

Bipolar disorder is responsible for the loss of more disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) than all forms of cancer or than major neurologic conditions such as epilepsy and Alzheimer’s disease1, primarily because of its early onset and chronicity across the life span. Aggregate estimates of the prevalence of bipolar disorder indicate that approximately 1.0% of the general population meet lifetime criteria for Bipolar I disorder (BP-I) 2–8. Estimates of the lifetime prevalence of bipolar II (BP-II) disorder have been provided by only one investigation that reported a median lifetime prevalence of 1.2% 8. However, a recent international review 9 of both DSM-IV bipolar I and II disorders in population studies yielded an aggregate cross-study lifetime prevalence estimate of 1.2%, ranging from 0.1% in Nigeria 10 to 3.3% in the U.S 11. Although these summaries have been instrumental in illuminating the scope and impact of bipolar illness, the estimation of international prevalence rates remains hampered by the lack of data based on comparable methodology12. The persistence of this limitation is also particularly surprising considering that it served as the impetus for the classic U.S.-UK that led to the development of common diagnostic methods for cross-cultural studies in psychiatry13.

In addition to the need for international comparisons based on common methodology, converging evidence from clinical and epidemiologic studies suggests that current diagnostic criteria for bipolar disorder fail to include milder but clinically significant syndromes. The application of the subthreshold bipolarity concept in a growing number of population surveys reveals that between 4% and 6% of adults may in fact manifest these conditions 14–17. However, a significant percentage of subthreshold bipolar cases are diagnosed by default as unipolar major depression using current criteria 16, 18, 19. Expanding the definition of bipolarity is nonetheless supported by prospective findings for a high probability of conversion to bipolar disorder in youth with subthreshold mania17, as well as by findings from the National Comorbidity Survey-Replication (NCS-R) indicating uniform increases in spectrum of severity and impairment across subthreshold, BP-II and BP-I categories 16. Investigations of depression and mania symptom severity associated with sub-threshold bipolar conditions further suggests that this category encompasses clinically significant manifestations that are comparable to people seeking treatment for bipolar disorder in outpatient settings 20.

A final limitation of previous research concerns the fact that most previous international studies have focused solely on prevalence estimates without including information on severity or disability associated with bipolar disorder. This information is necessary to facilitate cross-country analyses of comparable disorders, but also to help inform allocation of health services to populations having poor access to treatment, particularly in low-income countries 21. This report presents the lifetime and 12-month prevalence rates, patterns of comorbidity, impact, and use of mental health services for the bipolar spectrum (BP-I, BP-II, and subthreshold BP) in the World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative, a project of the World Health Organization (WHO) that aims to obtain accurate cross-national information on the prevalence, correlates, and service patterns of mental disorders in high, middle, and low income countries (www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/wmh/). The major aims of this report are: 1) to present the cross-national prevalence estimates of bipolar disorder using common diagnostic methodology; 2) to test the validity of the spectrum concept of bipolar disorder based on clinical severity, impairment, and comorbidity patterns; and 3) to examine cross-national service patterns for bipolar spectrum disorder.

METHODS

Samples

Eleven population-based surveys were carried out in the Americas (São Paulo Metropolitan Area in Brazil, Colombia, Mexico, United States), Europe (Bulgaria, Romania), Asia (Shenzhen, in the People’s Republic of China, Pondicherry region in India, nine metropolitan areas in Japan), Lebanon, and New Zealand. With the exception of Japan (unclustered two-stage probability sample), all surveys were based on stratified multi-stage clustered area probability samples. Interviews were carried out face-to-face by trained lay-interviewers on household residents ages 18 and older (except 16+ in New Zealand and 20+ in Japan). Sample sizes ranged from 2,357 (Romania) to 12,790 (New Zealand). Response rates ranged from 59.2% (Japan) to 98.8% (India), with an average of 75.0% (Table 1).

Table 1.

WMH Sample Characteristics

|

Country by income category1 |

Survey2 | Sample Characteristics3 |

Field Dates |

Age Range |

Sample Size4 | Response Rate5 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low and Lower-middle | Part I | Part II | Part II and Age ≤ 44 |

|||||

| Colombia | NSMH | Stratified multistage clustered area probability sample of household residents in all urban areas of the country (approximately 73% of the total national population) |

2003 | 18–65 | 4426 | 2381 | 1731 | 87.7 |

| India | WMHI | Stratified multistage clustered area probability sample of household residents in Pondicherry region. NR |

2003–5 | 18+ | 2992 | 1373 | 642 | 98.8 |

| PRC | Shenzhen | Stratified multistage clustered area probability sample of household residents and temporary residents in the Shenzhen area. |

2006–7 | 18+ | 7134 | 2476 | 1993 | 80.0 |

| Upper-middle | ||||||||

| Brazil | São Paulo Megacity |

Stratified multistage clustered area probability sample of household residents in the São Paulo metropolitan area. |

2005–7 | 18+ | 5037 | 2942 | -- | 81.3 |

| Bulgaria | NSHS | Stratified multistage clustered area probability sample of household residents. NR | 2003–7 | 18+ | 5318 | 2233 | 741 | 72.0 |

| Lebanon | LEBANON | Stratified multistage clustered area probability sample of household residents. NR | 2002–3 | 18+ | 2857 | 1031 | 595 | 70.0 |

| Mexico | M-NCS | Stratified multistage clustered area probability sample of household residents in all urban areas of the country (approximately 75% of the total national population). |

2001–2 | 18–65 | 5782 | 2362 | 1736 | 76.6 |

| Romania | RMHS | Stratified multistage clustered area probability sample of household residents. NR | 2005–6 | 18+ | 2357 | 2357 | -- | 70.9 |

| High | ||||||||

| Japan | WMHJ2002–2006 | Un-clustered two-stage probability sample of individuals residing in households in nine metropolitan areas (Fukiage, Higashi-ichiki, Ichiki, Kushikino, Nagasaki, Okayama, Sano, Tamano, and Tendo) |

2002–6 | 20+ | 3417 | 1305 | 425 | 59.2 |

| New Zealand6 | NZMHS | Stratified multistage clustered area probability sample of household residents. NR | 2004–5 | 16+ | 12790 | 7312 | 4119 | 73.3 |

| United States | NCS-R | Stratified multistage clustered area probability sample of household residents. NR | 2002–3 | 18+ | 9282 | 5692 | 3197 | 70.9 |

The World Bank. (2008). Data and Statistics. Accessed September 17, 2008 at: http://go.worldbank.org/D7SN0B8YU0

NSMH (The Colombian National Study of Mental Health); WMHI (World Mental Health India);NSHS (Bulgaria National Survey of Health and Stress); LEBANON (Lebanese Evaluation of the Burden of Ailments and Needs of the Nation); M-NCS (The Mexico National Comorbidity Survey); RMHS (Romania Mental Health Survey); WMHJ2002–2006 (World Mental Health Japan Survey); NZMHS (New Zealand Mental Health Survey); NCS-R (The US National Comorbidity Survey Replication).

Most WMH surveys are based on stratified multistage clustered area probability household samples in which samples of areas equivalent to counties or municipalities in the US were selected in the first stage followed by one or more subsequent stages of geographic sampling (e.g., towns within counties, blocks within towns, households within blocks) to arrive at a sample of households, in each of which a listing of household members was created and one or two people were selected from this listing to be interviewed. No substitution was allowed when the originally sampled household resident could not be interviewed. These household samples were selected from Census area data in all countries. The Japanese sample is the only totally un-clustered sample, with households randomly selected in each of the four sample areas and one random respondent selected in each sample household. 6 of the 11 surveys are based on nationally representative (NR) household samples, while two others are based on nationally representative household samples in urbanized areas (Colombia, Mexico).

Brazil and Romania did not have an age restricted Part II sample. All other countries, with the exception of India (which was age restricted to ≤ 39), were age restricted to ≤ 44.

The response rate is calculated as the ratio of the number of households in which an interview was completed to the number of households originally sampled, excluding from the denominator households known not to be eligible either because of being vacant at the time of initial contact or because the residents were unable to speak the designated languages of the survey. The weighted average response rate is 75.0%.

New Zealand interviewed respondents 16+ but for the purposes of cross-national comparisons we limit the sample to those 18+.

Procedures

In each participating country, the survey investigators and supervisors who were fluent in English and their local languages received standardized WHO-CIDI training at the Institute for Social Research at the University of Michigan CIDI on the use of the survey instrument and survey procedures. They were also involved in translation of the instrument and training materials for interviewers in their survey sites according to the translation protocol of the World Health Organization Surveys, carried out exclusively in the official languages of each country. Persons who could not speak these languages were excluded. Quality control protocols were standardized across countries to check on interviewers’ reliability and specify data cleaning and coding procedures. The institutional review board of the organization that coordinated the survey in each country approved and monitored compliance with procedures for obtaining informed consent and protecting participants’ identification.

Measures

All surveys used the WMH Survey version of the WHO Composite International Diagnostic Interview (WMH-CIDI, version 3.0), a fully structured diagnostic interview composed of two parts to reduce respondent burden and survey costs. Part 1 constituted the core diagnostic assessment of various mental disorders including major depressive disorder and bipolar disorders. Part 2 included additional information relevant to a wide range of survey objectives. All respondents completed Part 1 and those meeting criteria for any core mental disorder plus a probability sample of other respondents were administered Part 2. Part 1 sample was weighted to adjust for the probability of selection and non-response, and post-stratified to approximate the general population distribution regarding gender and age among other characteristics. Part 2 respondents were also weighted by the inverse of their probability of selection for Part 2 of the interview to adjust for differential sampling. Methodological evidence collected in the WMH-CIDI field trials and later clinical calibration studies showed that all the disorders considered here were assessed with acceptable reliability and validity. Manic, hypomanic, and major depressive episodes (MDE) were assessed according to DSM-IV criteria.

Bipolar disorders

Respondents were classified as having lifetime BP-I if they ever had a manic episode, defined by a period of seven days or more with elevated mood plus three other mania-related symptoms, or irritable mood plus four other mania-related symptoms, with the mood disturbance resulting in marked impairment, need for hospitalization, or psychotic features. Respondents were classified as having lifetime BP-II if they had both MDE and a hypomanic episode, defined by a period of four days or more with symptom criteria similar to mania and with an unequivocal change in functioning, but without a manic episode. Criteria for subthreshold hypomania included the presence of at least one of the screening questions for mania and failure to meet the full diagnostic criteria for hypomania. In the remainder of this report, we use the abbreviation “BPD to refer to people with either BP-I or BP-II, and “BPS” to refer to bipolar spectrum comprised of either BP-I, BP-II or subthreshold BP. The DSM-IV requirement that symptoms do not meet criteria for a Mixed Episode was not operationalized in making these diagnoses.

Among respondents with lifetime BP-I or BP-II, those reporting an MDE or a manic/hypomanic episode at any time in the 12 months before the interview were classified as having 12-month BPD. The number of manic/hypomanic episodes and MDE in this 12-month period was assessed. For those having episodes in the past 12 months, symptom severity and role impairment were also assessed. Symptom severity for the most severe month in the past 12 months was assessed with the self-report versions of the Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS)22, 23 for mania/hypomania and the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptoms (QIDS)24 for MDE. We defined level of severity for manic/hypomanic episode and MDE as severe (YMRS> 24, QIDS > 15), moderate (14 <YMRS <=24, 10 < QIDS <=15), mild (8 < YMRS <=14, 5 < QIDS <=10) or clinically non-significant (0 <= YMRS <=8, 0 <=QIDS <=5). Role impairment was assessed with the Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS)25. Respondents were asked to focus on the months in the past year when their manic/hypomanic episode or MDE was most severe and to rate how much the condition interfered with their home management, work, social life, and close relationships using a visual analogue scale from 1 to 10. Impairment was scored as none (0), mild (1–3), moderate (4–6), severe (7–9), or very severe (10). Clinical features such as age of onset, course, longest lifetime episode, and number of months in episode during previous year were assessed separately for manic/hypomanic episodes and MDE.

Other disorders

Assessment of other DSM-IV disorders/symptoms included anxiety disorders (generalized anxiety disorder, panic attacks, panic disorder and/or agoraphobia, post-traumatic stress disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, specific phobia, social phobia, separation anxiety disorder), impulse-control disorders (attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, conduct disorder, and intermittent explosive disorder) and substance-related disorders (alcohol abuse and dependence, drug abuse and dependence). Organic exclusion rules and diagnostic hierarchy rules were used in making all diagnoses (i.e., the diagnosis was not made if the respondent indicated that the episode of depression or mania was due to physical illness or injury or use of medication, drugs, or alcohol). Blinded clinical reappraisal interviews using the non-patient version of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID)26 with a probability sub-sample of respondents in the US National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) found generally good concordance of CIDI/DSM-IV diagnoses of anxiety, mood, and substance-related disorders with independent clinical assessments27. The SCID clinical reappraisal interviews did not include an assessment of impulse-control disorders.

Other measures

We also considered the association of BPD with sociodemographic variables at the time of interview such as gender, age (18–34, 35–49, 50–64, 65+ years), marital status (married, previously married, never married), education level compared to local country standard (low, low-average, high-average, high), employment status (working, student, homemaker, retired, other including those being unemployed) and household income compared to local country standard (low, low-average, high-average, high). Results are not presented by income level for all of the analyses but differences are described in the text whenever relevant. Cross-country treatment rates are presented by income levels because of international variation in the availability of mental health services. All part 2 respondents were asked about 12-month and lifetime treatment of any problem concerning emotions, nerves, or substance use by a psychiatrist, other mental health professional (psychologist, psychotherapist, psychiatric nurse), general medical provider, human services professional, and complementary-alternative medical (CAM) provider (e.g., acupuncturist, chiropractor, spiritual healer). They were also asked about treatment specific to MDE and/or mania-hypomania, whether the treatment was helpful or effective, hospitalization for MDE and/or mania-hypomania, and use of indicated medications such as mood stabilizers, antidepressants or antipsychotics.

Statistical Analysis

Age-of-onset and projected lifetime risk as of age 75 were estimated using the two-part actuarial method implemented in SAS 8.228. Predictors were examined using discrete-time survival analysis with person-year as the unit of analysis. Standard errors were estimated using the Taylor series linearization method implemented in the SUDAAN software system. Multivariate significance tests were made with Wald ÷2 tests, using Taylor series design-based coefficient variance-covariance matrices. Standard errors of lifetime risk were estimated using the jackknife repeated replication method29, 30 implemented in a SAS macro30. Significance tests were all evaluated at the .05 level with two-sided tests.

RESULTS

Lifetime and 12-month prevalence and age of onset

The lifetime prevalence rates of BP-I, BP-II, and subthreshold BP from the pooled sample of eleven countries were 0.6%, 0.4%, and 1.4%, respectively (Table 2). The 12-month prevalence of BP-I, BP-II, and subthreshold BP was 0.4%, 0.3%, and 0.8%, respectively. The United States had the highest lifetime and 12-month prevalence of BPS (4.4%, 2.8%) while India had the lowest (0.1%, 0.1%). Exceptions were found for Japan, a high income country with very low lifetime and 12-month prevalence of BPS (0.7%, 0.2%), and Colombia, a low income country with high lifetime prevalence of BPS (2.6%). Lifetime rates of BP-I and subthreshold BP were greater in males than in females, whereas females had higher rates of BP-II than their male counterparts. There were no other significant differences between BPS and other sociodemographic correlates including marital status, employment status, and family income (not shown).

Table 2.

Cross-National Lifetime and 12-month Prevalence of DSM-IV/CIDI Major Depressive Episode and Bipolar Spectrum Disorders

| Major Depressive Episode | BPS | BP-I | BP-II | Subthreshold BP | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| country | N | % | SE | N | % | SE | N | % | SE | N | % | SE | N | % | SE | |

| Lifetime | Brazil | 953 | 18.3 | 0.8 | 98 | 2.1 | 0.2 | 35 | 0.9 | 0.2 | 11 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 52 | 1.1 | 0.2 |

| Bulgaria | 328 | 5.7 | 0.4 | 9 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 6 | 0.2 | 0.1 | |

| Colombia | 603 | 13.3 | 0.6 | 115 | 2.6 | 0.3 | 33 | 0.7 | 0.2 | 16 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 66 | 1.5 | 0.2 | |

| India | 307 | 9.0 | 0.5 | 5 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 4 | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| Japan | 218 | 6.4 | 0.4 | 20 | 0.7 | 0.2 | 2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 3 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 15 | 0.5 | 0.1 | |

| Lebanon | 307 | 10.9 | 0.9 | 61 | 2.4 | 0.4 | 10 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 10 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 41 | 1.5 | 0.3 | |

| Mexico | 531 | 8.0 | 0.5 | 106 | 1.9 | 0.2 | 39 | 0.7 | 0.1 | 8 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 59 | 1.0 | 0.2 | |

| New Zealand | 2383 | 18.0 | 0.4 | 617 | 3.9 | 0.2 | 188 | 1.0 | 0.1 | 121 | 0.7 | 0.1 | 308 | 2.1 | 0.2 | |

| Romania | 101 | 3.3 | 0.5 | 36 | 1.8 | 0.3 | 4 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 5 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 27 | 1.4 | 0.3 | |

| Shenzhen | 476 | 6.5 | 0.4 | 90 | 1.5 | 0.2 | 14 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 12 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 64 | 1.0 | 0.2 | |

| United States | 1829 | 19.2 | 0.5 | 416 | 4.4 | 0.3 | 101 | 1.0 | 0.1 | 105 | 1.1 | 0.1 | 210 | 2.4 | 0.2 | |

| All countries | 8036 | 12.5 | 0.2 | 1573 | 2.4 | 0.1 | 429 | 0.6 | 0.0 | 292 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 852 | 1.4 | 0.1 | |

| 12 month | Brazil | 540 | 10.4 | 0.6 | 73 | 1.5 | 0.2 | 27 | 0.6 | 0.1 | 10 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 36 | 0.7 | 0.1 |

| Bulgaria | 145 | 2.5 | 0.3 | 3 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3 | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| Colombia | 280 | 6.2 | 0.4 | 65 | 1.5 | 0.2 | 18 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 12 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 35 | 0.8 | 0.2 | |

| India | 154 | 4.6 | 0.4 | 3 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3 | 0.1 | 0.0 | |

| Japan | 72 | 2.2 | 0.3 | 7 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 5 | 0.2 | 0.1 | |

| Lebanon | 144 | 5.5 | 0.7 | 44 | 1.9 | 0.4 | 8 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 9 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 27 | 1.1 | 0.3 | |

| Mexico | 268 | 4.0 | 0.3 | 64 | 1.1 | 0.2 | 26 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 6 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 32 | 0.5 | 0.1 | |

| New Zealand | 901 | 6.6 | 0.3 | 351 | 2.2 | 0.2 | 112 | 0.6 | 0.1 | 75 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 164 | 1.1 | 0.1 | |

| Romania | 46 | 1.8 | 0.3 | 21 | 1.0 | 0.2 | 2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 5 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 14 | 0.7 | 0.2 | |

| Shenzhen | 249 | 3.8 | 0.3 | 61 | 1.1 | 0.2 | 10 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 8 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 43 | 0.8 | 0.1 | |

| United States | 805 | 8.3 | 0.3 | 262 | 2.8 | 0.2 | 65 | 0.6 | 0.1 | 74 | 0.8 | 0.1 | 123 | 1.4 | 0.2 | |

| All countries | 3604 | 5.6 | 0.1 | 954 | 1.5 | 0.1 | 269 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 200 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 485 | 0.8 | 0.0 | |

Abbreviations: MDE, Major Depressive Episode, BPS, bipolar spectrum disorder; BP-I, DSM-IV bipolar I disorder; BP-II, DSM-IV bipolar II disorder; CIDI, Composite International Diagnostic Interview

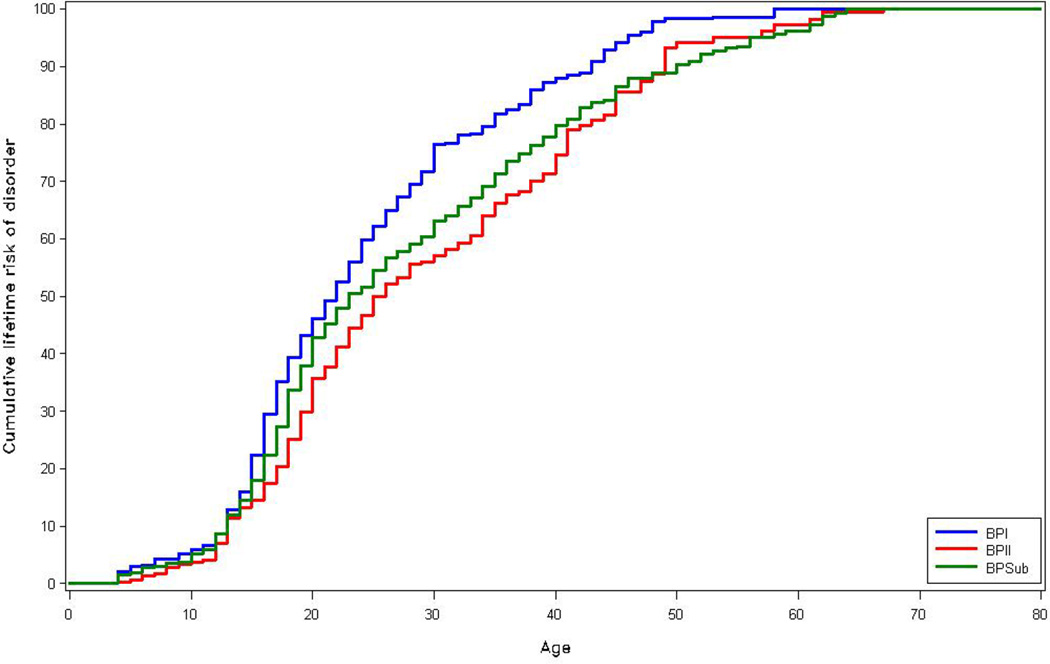

The cumulative lifetime risk of BPS subtypes is shown in Figure 1. Approximately half of those with BP-I and subthreshold BP report onset before age 25, and those with BP-II report a slightly later age of onset. However, there was a direct increase in the mean age of onset with less severe subtypes of BPS; the mean (SE) age of onset of BP-I was 18.4 (0.7) years, BP-I BP-II was 20.0 (0.6) years, and subthreshold BP was 21.9 (0.4) years.

Figure 1.

Cumulative age of onset distributions of DSM-IV/CIDI BP-1, BP-II, and subthreshold BP among respondents projected to develop these disorders in their lifetime

Lifetime comorbidity with other DSM-IV disorders

Three-quarters of those with BPS also met criteria for another lifetime disorder, more than half of whom had 3 or more other disorders (Table 3). Anxiety disorders, particularly panic attacks, were the most common comorbid conditions, followed by behavior disorders (44.8%) and substance use disorders (36.6%). There were significantly greater rates of comorbid disorders among those with BP-I (88.2%) and BP-II (83.1%) than among those with subthreshold BP (69.1%), although the odds of comorbid disorders were still significantly elevated for those with subthreshold BP relative to those without BP. Patterns of comorbidity with anxiety disorders and substance use disorders were remarkably similar across countries, whereas rates of comorbid behavior disorders were substantially higher in the U.S. and New Zealand compared to most other countries.

Table 3.

Lifetime Comorbidity of DSM-IV/CIDI Bipolar Spectrum Disorders with Other DSM-IV/CIDI Disorders

| BPS | BP I | BP II | Subthreshold BP | χ2‡ | p-value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disorder | % (SE)* | OR (95% CI)† | % (SE)* | OR (95% CI)† | % (SE)* | OR (95% CI)† | % (SE)* | OR (95% CI)† | ||

| Anxiety disorders | ||||||||||

| Agoraphobia without panic | 6.4 (0.8) | 6.7 (5.0,8.9) | 6.8 (1.5) | 6.4 (4.0,10.1) | 8.8 (1.8) | 9.7 (6.0,15.7) | 5.4 (1.0) | 5.8 (3.8,8.9) | 3.1 | 0.212 |

| Panic disorder | 11.1 (0.9) | 5.5 (4.5,6.7) | 17.5 (2.4) | 9.6 (6.8,13.7) | 16.8 (2.7) | 7.5 (5.1,10.9) | 6.5 (0.9) | 3.2 (2.4,4.2) | 31.4 | 0.000 |

| Panic attacks | 49.8 (1.5) | 4.4 (3.8,5.0) | 57.9 (3.2) | 6.3 (4.8,8.5) | 63.8 (3.4) | 6.8 (5.1,9.2) | 41.7 (2.0) | 3.2 (2.7,3.8) | 27.0 | 0.000 |

| PTSD | 18.9 (1.3) | 5.2 (4.2,6.3) | 26.3 (2.7) | 8.2 (6.2,11.0) | 25.0 (2.8) | 6.4 (4.8,8.5) | 13.4 (1.6) | 3.6 (2.6,4.8) | 17.4 | 0.000 |

| GAD | 20.5 (1.3) | 5.5 (4.6,6.5) | 26.9 (2.8) | 8.0 (6.0,10.6) | 32.8 (3.3) | 8.9 (6.6,12.2) | 13.7 (1.4) | 3.5 (2.7,4.5) | 26.8 | 0.000 |

| Specific phobia | 30.1 (1.4) | 4.0 (3.4,4.6) | 39.4 (2.9) | 5.8 (4.5,7.5) | 41.3 (3.2) | 6.2 (4.8,8.0) | 22.4 (1.7) | 2.7 (2.2,3.4) | 30.7 | 0.000 |

| Social phobia | 25.9 (1.4) | 4.5 (3.8,5.3) | 35.4 (3.2) | 7.2 (5.4,9,6) | 36.3 (3.3) | 6.6 (4.9,8.9) | 18.3 (1.6) | 3.0 (2.3,3.8) | 29.3 | 0.000 |

| OCD | 12.5 (1.4) | 5.7 (4.2,7.8) | 17.7 (2.8) | 9.0 (5.9,13.8) | 11.8 (2.9) | 6.4 (3.3,12.5) | 10.1 (1.8) | 4.1 (2.7,6.4) | 7.6 | 0.022 |

| SAD | 29.3 (1.7) | 5.3 (4.4,6.3) | 35.6 (4.0) | 6.5 (4.5,9.3) | 38.9 (4.5) | 7.9 (5.4,11.7) | 23.3 (2.2) | 4.0 (3.1,5.2) | 9.1 | 0.010 |

| Any anxiety disorder | 62.9 (1.6) | 5.6 (4.8,6.5) | 76.5 (2.7) | 10.3 (7.5,14.1) | 74.6 (3.0) | 9.1 (6.5,12.7) | 52.9 (2.2) | 3.8 (3.2,4.7) | 37.2 | 0.000 |

| Behavior disorders¶ | ||||||||||

| IED | 24.0 (1.8) | 5.5 (4.5,6.7) | 33.5 (4.0) | 8.3 (5.7,12.2) | 18.7 (3.5) | 3.8 (2.4,5.9) | 21.9 (2.2) | 5.1 (3.8,6.7) | 7.7 | 0.021 |

| ADHD | 19.8 (1.9) | 6.9 (5.4,9.0) | 27.6 (3.6) | 10.8 (7.3,15.9) | 27.5 (5.7) | 9.2 (5.5,15.5) | 14.3 (2.1) | 4.9 (3.3,7.3) | 8.8 | 0.012 |

| ODD | 24.8 (2.2) | 5.9 (4.6,7.5) | 30.4 (3.9) | 8.2 (5.6,12.1) | 29.2 (5.6) | 6.5 (3.5,12.1) | 21.0 (2.9) | 4.8 (3.5,6.6) | 4.3 | 0.116 |

| CD | 19.1 (1,9) | 5.2 (4.0,6.7) | 28.2 (3.9) | 9.2 (6.1,13.7) | 16.4 (3.9) | 3.5 (1.9,6.5) | 15.9 (2.3) | 4.3 (3.0,6.1) | 9.6 | 0.008 |

| Any behavior disorder | 44.8 (2.3) | 6.4 (5.2,7.9) | 54.1 (4.4) | 9.3 (6.4,13.5) | 51.8 (6.0) | 7.2 (4.5,11.5) | 38.9 (2.9) | 5.3 (3.9,7.1) | 5.8 | 0.055 |

| Substance use disorders | ||||||||||

| Alcohol abuse | 34.2 (1.5) | 4.6 (4.0,5.3) | 48.3 (2.9) | 7.9 (6.2,10.1) | 33.5 (3.1) | 4.1 (3.1,5.6) | 28.2 (2.1) | 3.6 (2.9,4.4) | 29.1 | 0.000 |

| Alcohol dependence | 18.0 (1.2) | 6.0 (5.0,7.3) | 31.1 (2.9) | 12.1 (9.0,16.4) | 17.2 (2.5) | 5.2 (3.6,7.6) | 12.2 (1.5) | 3.9 (3.0,5.2) | 32.6 | 0.000 |

| Drug abuse | 17.8 (1.3) | 4.0 (3.3,5.0) | 31.9 (2.7) | 9.2 (7.0,12.1) | 17.1 (2.2) | 3.6 (2.6,4.9) | 11.6 (1.5) | 2.4 (1.8,3.3) | 40.6 | 0.000 |

| Drug dependence | 10.5(1.0) | 7.4 (5.8,9.4) | 23.8 (2.6) | 18.2 (13.2,25.1) | 8.1 (1.9) | 4.8 (2.8,8.3) | 5.3 (1.0) | 3.2 (2.2,4.7) | 53.5 | 0.000 |

| Any substance disorder | 36.6 (1.6) | 4.5 (3.9,5.3) | 52.3 (3.1) | 8.4 (6.5,10.8) | 36.5 (3.0) | 4.2 (3.2,5.6) | 29.5 (2.1) | 3.4 (2.8,4.1) | 34.0 | 0.000 |

| Any disorder | 76.5 (1.4) | 7.3 (6.2,8.7) | 88.2 (1.9) | 15.7 (10.8,22.9) | 83.1 (2.6) | 10.3 (7.1,14.9) | 69.1 (2.1) | 5.3 (4.2,6.6) | 26.3 | 0.000 |

| Exactly 1 disorder | 20.2 (1.3) | 4.0 (3.2,5.0) | 15.8 (2.0) | 5.9 (3.8,9.0) | 14.3 (2.6) | 3.9 (2.2,6.9) | 24.2 (2.0) | 3.6 (2.7,4.8) | 3.2 | 0.199 |

| Exactly 2 disorders | 12.3 (1.0) | 5.1 (3.9,6.5) | 10.1 (1.8) | 8.2 (4.6,14.5) | 10.5 (2.2) | 5.9 (3.3,10.7) | 13.9 (1.5) | 4.4 (3.2,6.0) | 3.9 | 0.144 |

| 3 or more disorders | 43.9 (1.6) | 16.6 (13.3,20.7) | 62.2 (3.1) | . | 58.3 (3.3) | . | 31.0 (2.1) | . | . | . |

Abbreviations: ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; BPS, bipolar spectrum disorder; BP-I, DSM-IV bipolar I disorder; BP-II, DSM-IV bipolar II disorder; CD, conduct disorder; CI, confidence interval; CIDI, Composite International Diagnostic Interview; GAD, generalized anxiety disorder; IED, intermittent explosive disorder; OCD, obsessive-compulsive disorder; ODD, oppositional defiant disorder; OR, odds ratio; PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder; SAD, separation anxiety disorder.

Mean (SE) prevalence of the comorbid disorder in respondents with BPS.

Based on logistic regression models with 1 DSM-IV/CIDI disorder at a time as a predictor of lifetime BPS, controlling for age at interview, age at interview squared and country. The last model had the predictors “exactly 1,” “exactly 2,” and “3 or more” disorders in 1 model.

Test of the significance of the difference in ORs across the 3 BPS subgroups.

Sample included part II respondents who were 39/44 years or younger at interview.

Clinical severity

The vast majority of 12-month BPS cases reported severe or moderate manic/hypomanic or major depressive episodes in the past year (Table 4). Combined manic/hypomanic and depressive episodes in the past 12 months were more severe among BP-I (74.5%) and II (68.8%) compared to subthreshold BP (42.5%). The severity of depressive episodes was greater among those from low (95.5%) and medium (77.4%) than those in high (68.5%) income countries, whereas the severity of mania was comparable across low and middle income countries and slightly higher in high income countries (results not shown).

Table 4.

Clinical Severity in Respondents with 12-Month DSM-IV/CIDI Bipolar Spectrum Disorders

| BPS | BP-I | BP-II | Subthreshold BP |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | SE | % | SE | % | SE | % | SE | χ2* | p-value | |

| Manic/hypomanic episode, %(se) † | ||||||||||

| Severe | 39.6 | 2.7 | 66.6 | 6.3 | 44.3 | 6.2 | 26.6 | 3.3 | 31.2 | 0.000 |

| Moderate | 42.8 | 3.0 | 24.8 | 5.6 | 36.1 | 6.3 | 52.6 | 3.9 | 4.3 | 0.117 |

| Mild | 15.0 | 2.6 | 8.6 | 3.9 | 14.5 | 5.2 | 18.0 | 3.7 | 12.2 | 0.002 |

| None | 2.5 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 5.2 | 2.7 | 2.8 | 0.9 | . | . |

| No. § | 418 | 109 | 72 | 237 | ||||||

| Major depressive episode, %(se) $ | ||||||||||

| Severe | 73.1 | 2.9 | 76.5 | 5.1 | 76.1 | 4.7 | 66.1 | 5.1 | 5.5 | 0.063 |

| Moderate | 25.2 | 2.9 | 20.4 | 5.2 | 22.4 | 4.7 | 33.3 | 5.1 | 2.8 | 0.249 |

| Mild | 1.6 | 0.6 | 3.1 | 1.5 | 1.4 | 1.1 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 1.0 | 0.606 |

| None | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.3 | . | . |

| No. §§ | 416 | 140 | 146 | 130 | ||||||

| Combined, %(se) # | ||||||||||

| Severe | 57.4 | 2.4 | 74.5 | 4.5 | 68.8 | 4.7 | 42.5 | 3.3 | 31.0 | 0.000 |

| Moderate | 33.9 | 2.4 | 21.2 | 4.4 | 26.8 | 4.5 | 44.3 | 3.4 | 7.3 | 0.027 |

| Mild | 7.9 | 1.6 | 4.3 | 1.9 | 4.4 | 2.2 | 11.6 | 2.9 | 7.4 | 0.025 |

| None | 0.8 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.5 | 0.6 | . | . |

| No. §§§ | 670 | 192 | 169 | 309 | ||||||

Abbreviations: BPS, bipolar spectrum disorder; BP-I, DSM-IV bipolar I disorder; BP-II, DSM-IV bipolar II disorder; CIDI, Composite International Diagnostic Interview.

Significance tests were performed for cumulative categories. In the case of moderate severity, the BPSsubgroups were compared for the prevalence of severe or moderate vs. mild or none. In the case of mild severity, the BPS subgroups were compared for the prevalence of any severity (ie, severe, moderate, or mild) vs none. No significance test values are given for the final category (none) because of this cumulative coding.

Based on the Young Mania Rating Scale.23

Significant difference across the 3 BPS subgroups at the P=.05 level, 2-sided test.

Number of 12-month cases of mania/hypomania with valid YMRS (New Zealand did not assess the YMRS)

Based on the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology Self-Report.24

Number of major depressive episodes among people with 12-month BPS with valid QIDS

Respondents who reported both manic/hypomanic and major depressive episodes in the past year were assigned the more severe of their 2 severity scores.

Number of 12-month BPS in the sample with either valid YMRS or valid QIDS.

Role impairment

The aggregate proportions of severity levels of role impairment as assessed by the Sheehan Disability Scale by BP subtypes are presented in Table 5. The proportion of respondents with severe and very severe role impairment was greater for depression (74.0%) than for mania (50.9%). Severe and very severe role impairment was greater in high income countries for both mania (57.3%) and depression (84.9%) than in medium (49.0% for mania; 58.7% for depression) and low (30.4% for mania; 55.1% for depression) income countries (results not shown).

Table 5.

Severity of Role Impairment in Respondents with 12-Month DSM-IV/CIDI Bipolar Spectrum Disorders*

| BPS | BP-I | BP-II | Subthreshold BP | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | SE | % | SE | % | SE | % | SE | χ2† | p-value | |

| Manic/hypomanic episode, %(SE) | ||||||||||

| Severe and very severe | 50.9 | 2.2 | 57.1 | 4.7 | 57.0 | 4.9 | 46.3 | 3.2 | 3.9 | 0.142 |

| Moderate | 30.2 | 2.1 | 29.2 | 4.3 | 22.4 | 4.1 | 33.0 | 2.8 | 4.7 | 0.095 |

| Mild | 8.2 | 1.3 | 7.5 | 2.3 | 4.1 | 1.5 | 9.8 | 1.9 | 10.8 | 0.005 |

| None | 10.7 | 1.3 | 6.2 | 2.4 | 16.5 | 4.2 | 10.9 | 1.6 | ||

| No. § | 744 | 211 | 132 | 401 | ||||||

| Major depressive episode, %(SE) | ||||||||||

| Severe and very severe | 74.0 | 2.9 | 77.6 | 5.1 | 72.8 | 4.7 | 71.9 | 4.5 | 3.7 | 0.154 |

| Moderate | 20.4 | 2.7 | 19.2 | 5.0 | 21.9 | 4.4 | 19.9 | 4.4 | 1.3 | 0.514 |

| Mild | 2.0 | 0.9 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 1.4 | 0.8 | 4.4 | 2.4 | 0.1 | 0.932 |

| None | 3.5 | 1.2 | 2.7 | 1.7 | 3.9 | 2.2 | 3.8 | 2.3 | ||

| No. §§ | 452 | 150 | 156 | 146 | ||||||

Abbreviations: BPS, bipolar spectrum disorder; BP-I, DSM-IV bipolar I disorder; BP-II, DSM-IV bipolar II disorder; CIDI, Composite International Diagnostic Interview; MDE, major depressive episode.

Based on the Sheehan Disability Scale.26 Respondents were assigned their highest rating of impairment across the 4 Sheehan Disability Scale domains.

Significance of differences across 3 BPSsubgroups in part II was evaluated for cumulative categories. In the case of moderate severity, the BPS subgroups were compared for the prevalence of severe or moderate vs. mild or none. In the case of mild severity, the subgroups were compared for the prevalence of any severity (ie, severe, moderate, or mild) vs none.

Number of 12-month BPS in the sample with valid Sheehan associated with 12M mania/hypomania.

Number of 12-month BPS in the sample with valid Sheehan associated with 12M major depressive episode

Suicide Attempts

Suicidal behaviors among those with BPS during the past 12 months are shown in Table 6. Similar to the other clinical indicators of severity, there was an increasing proportion of with suicidal behaviors with increasing levels of the BPS. One of every 4 persons with BP-I, 1 of 5 of those with BP-II, and 1 in 10 of those with subthreshold BP reported a history of suicide attempts.

Table 5a.

Suicidal Ideation, Plans and Attempts in Respondents with 12-Month DSM-IV/CIDI Bipolar Spectrum Disorders

| BPS | BP-I | BP-II | Subthreshold BP | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | SE | N | % | SE | N | % | SE | N | % | SE | χ2 | p-val | |

| Suicide ideation | 444 | 43.4 | 1.9 | 156 | 52.2 | 3.9 | 109 | 50.6 | 4.0 | 179 | 36.3 | 2.7 | 10.8 | 0.005 |

| Suicide plan | 225 | 21.0 | 1.6 | 90 | 31.4 | 3.4 | 55 | 23.9 | 3.6 | 80 | 14.9 | 1.9 | 13.6 | 0.001 |

| Suicide attempt | 161 | 16.0 | 1.5 | 69 | 25.6 | 3.5 | 42 | 20.8 | 3.4 | 50 | 9.5 | 1.6 | 20.7 | 0.000 |

Abbreviations: BPS, bipolar spectrum disorder; BP-I, DSM-IV bipolar I disorder; BP-II, DSM-IV bipolar II disorder; CIDI, Composite International Diagnostic Interview

Lifetime and 12-month treatment

A substantially greater proportion of respondents with any bipolar spectrum disorder from high income countries reported mental health service use (50.2% lifetime; 28.4% 12-month) than those in middle income (33.9% lifetime; 15.9% 12-month) or low income (25.2% lifetime; 13.0% 12-month) countries (Table 7). Most respondents used mental health specialty sectors followed by the general medical sector, and smaller proportions used human services and CAM. Significantly greater proportions of those with BP-1 (51.6%) and BP-II (59.9%) reported mental health specialty treatment than those with subthreshold BP (33.3%). Similar findings emerged for 12-month treatment.

Table 6.

Lifetime and 12 Month Treatment of DSM-IV/CIDI Bipolar Spectrum Disorders

| Country by income category |

Lifetime treatment*, %(SE) | 12-month treatment*, %(SE) | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mental health specialty | General medical |

Human services |

CAM | Any | Mental health specialty | General medical |

Human services |

CAM | Any | |||||||

| No. | Psychiatrist | Other MH |

Any MH | No. | Psychiatrist | Other MH |

Any MH | |||||||||

| Low & lower-middle | ||||||||||||||||

| BPS | 210 | 13.9(3.6) | 16.5(3.2) | 25.2(3.9) | 6.8(2.1) | 3.3(1.2) | 3.9(1.5) | 35.1(3.9) | 129 | 10.6(4.3) | 3.1(1.3) | 13.0(4.4) | 7.9(2.9) | 0.9(0.8) | 0.4(0.4) | 18.5(4.6) |

| BP-I | 48 | 18.4(7.1) | 11.8(5.1) | 22.3(7.4) | 9.6(4.8) | 9.2(4.6) | 7.7(4.5) | 37.9(8.3) | 28 | 6.1(4.3) | 0.0(0.0) | 6.1(4.3) | 13.8(6.5) | 0.9(1.0) | 1.9(1.9) | 16.6(6.8) |

| BP-II | 28 | 19.3(8.2) | 25.7(8.4) | 34.7(9.2) | 0.0(0.0) | 0.0(0.0) | 4.0(3.0) | 35.9(9.3) | 20 | 9.1(5.3) | 7.4(5.6) | 12.5(6.8) | 8.7(8.2) | 0.0(0.0) | 0.0(0.0) | 21.2(10.2) |

| Sub BP | 134 | 11.2(4.2) | 16.1(4.1) | 24.2(5.0) | 7.2(2.5) | 1.8(1.1) | 2.5(1.3) | 33.9(5.1) | 81 | 12.6(6.3) | 2.9(1.7) | 15.3(6.3) | 5.8(3.2) | 1.2(1.2) | 0.0(0.0) | 18.4(6.3) |

| χ2 | 0.9 | 4.0 | 2.1 | 10.5 | 5.0 | 1.3 | 0.2 | 0.8 | 4.1 | 1.6 | 1.4 | 1.8 | 1.0 | 0.1 | ||

| p value | 0.623 | 0.135 | 0.358 | 0.006 | 0.087 | 0.517 | 0.925 | 0.683 | 0.132 | 0.441 | 0.496 | 0.404 | 0.606 | 0.942 | ||

| Upper-middle | ||||||||||||||||

| BPS | 310 | 20.5(3.0) | 20.7(2.8) | 33.9(3.6) | 17.0(2.5) | 6.1(1.8) | 7.2(1.7) | 45.3(3.9) | 205 | 10.2(2.3) | 8.0(2.3) | 15.9(3.0) | 8.4(2.1) | 2.7(1.0) | 2.9(1.4) | 24.9(3.8) |

| BP-I | 90 | 34.5(5.9) | 21.6(4.9) | 44.8(6.5) | 15.6(3.8) | 6.1(2.4) | 9.8(2.8) | 54.7(6.7) | 63 | 17.9(5.9) | 7.6(2.7) | 23.3(6.3) | 9.8(3.5) | 5.2(2.4) | 3.2(1.6) | 35.1(6.8) |

| BP-II | 35 | 21.0(7.9) | 16.3(7.4) | 26.7(8.2) | 22.3(7.9) | 1.4(1.4) | 16.9(7.7) | 43.0(9.7) | 30 | 7.9(5.1) | 0.0(0.0) | 7.9(5.1) | 9.2(5.6) | 0.0(0.0) | 10.9(7.5) | 28.0(9.5) |

| Sub BP | 185 | 13.4(2.8) | 21.2(3.4) | 29.9(3.9) | 16.6(3.6) | 7.0(2.6) | 4.0(2.1) | 41.1(4.4) | 112 | 6.5(2.3) | 10.5(3.8) | 14.2(4.1) | 7.4(3.5) | 2.0(1.3) | 0.3(0.3) | 18.1(4.2) |

| χ2 | 11.7 | 0.4 | 5.3 | 0.6 | 3.7 | 4.6 | 3.1 | 3.5 | 10.9 | 2.7 | 0.2 | 6.3 | 5.2 | 4.7 | ||

| p value | 0.003 | 0.815 | 0.075 | 0.756 | 0.157 | 0.104 | 0.213 | 0.178 | 0.005 | 0.261 | 0.901 | 0.046 | 0.075 | 0.096 | ||

| High | ||||||||||||||||

| BPS | 1053 | 37.1(2.0) | 35.3(1.9) | 50.2(2.0) | 46.3(2.1) | 18.3(1.4) | 21.6(1.7) | 74.9(1.6) | 620 | 16.4(1.7) | 22.8(1.9) | 28.4(2.0) | 33.7(2.3) | 8.9(1.3) | 9.6(1.6) | 49.5(2.4) |

| BP-I | 291 | 49.3(3.9) | 48.3(3.7) | 61.3(3.3) | 52.5(3.6) | 22.5(2.9) | 33.2(3.8) | 82.0(2.7) | 178 | 25.5(4.0) | 32.6(4.6) | 39.8(4.5) | 37.4(4.8) | 12.4(3.0) | 15.9(3.9) | 58.6(4.4) |

| BP-II | 229 | 56.8(4.1) | 48.0(3.4) | 70.7(3.5) | 63.3(3.8) | 24.2(3.2) | 25.1(3.4) | 94.7(1.7) | 150 | 25.3(3.9) | 30.5(4.0) | 40.5(4.3) | 44.9(4.9) | 10.1(2.8) | 11.8(2.8 | 67.2(4.7) |

| Sub BP | 533 | 23.9(2.3) | 24.4(2.5) | 37.2(2.9) | 36.8(2.6) | 14.1(1.9) | 15.0(1.8) | 63.8(2.8) | 292 | 7.7(1.8) | 14.3(2.3) | 17.0(2.5) | 26.6(3.1) | 6.6(1.8) | 5.5(1.5) | 36.5(3.2) |

| χ2 | 50.2 | 38.4 | 45.3 | 34.8 | 11.8 | 22.1 | 69.5 | 23.8 | 20.4 | 32.8 | 9.4 | 3.3 | 10.1 | 29.7 | ||

| p value | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.003 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.010 | 0.194 | 0.007 | 0.000 | ||

| All Countries | ||||||||||||||||

| BPS | 1573 | 29.8(1.5) | 29.1(1.4) | 42.7(1.6) | 33.6(1.6) | 13.3(1.0) | 15.7(1.1) | 62.1(1.6) | 954 | 14.0(1.3) | 16.0(1.3) | 22.9(1.6) | 23.4(1.7) | 6.1(0.9) | 6.5(1.0) | 38.5(1.9) |

| BP-I | 429 | 41.1(3.1) | 36.2(2.9) | 51.6(3.1) | 36.8(2.9) | 16.3(2.1) | 23.5(2.7) | 68.7(3.0) | 269 | 20.7(3.0) | 21.1(3.0) | 30.6(3.4) | 26.3(3.3) | 8.8(1.9) | 10.4(2.4) | 46.3(3.7) |

| BP-II | 292 | 47.1(3.7) | 40.6(3.1) | 59.9(3.5) | 49.9(3.5) | 18.0(2.5) | 21.5(2.8) | 80.2(3.0) | 200 | 20.0(3.1) | 21.9(3.0) | 30.9(3.5) | 33.6(4.0) | 7.0(2.0) | 10.2(2.4) | 54.1(4.4) |

| Sub BP | 852 | 19.3(1.7) | 22.3(1.8) | 33.3(2.1) | 27.0(1.9) | 10.4(1.3) | 10.3(1.2) | 53.4(2.2) | 485 | 8.3(1.7) | 11.2(1.7) | 16.0(2.1) | 17.9(2.1) | 4.5(1.1) | 3.2(0.9) | 28.6(2.4) |

| χ2 | 61.9 | 30.9 | 45.5 | 37.4 | 12.0 | 31.1 | 54.0 | 19.2 | 14.1 | 21.7 | 13.4 | 4.4 | 16.0 | 32.9 | ||

| p value | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.003 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.109 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||

Abbreviations: BPS, bipolar spectrum disorder; BP-I, DSM-IV bipolar I disorder; BP-II, DSM-IV bipolar II disorder; CAM, complementary and alternative medicine; CIDI, Composite International Diagnostic Interview.

Treatment either for mania/hypomania or for a major depressive episode.

DISCUSSION

This paper presents the first international data on the prevalence of DSM-IV bipolar disorder and the broader bipolar spectrum using common diagnostic procedures and methodology. In a combined sample of 61,392 adults from 11 countries, the total lifetime prevalence of BP-I was 0.6%, BP-II was 0.4%, and subthreshold BP was 1.4%, yielding a total prevalence estimate BPS of 2.4% worldwide. Comparable 12-month prevalence rates were 0.4% for BP-I, 0.3% for BP-II, and 0.8% for subthreshold BP, with a total 12-month prevalence BPS of 1.5%. These rates are somewhat lower than those from earlier reviews of European studies 12 and international studies 9, which yielded aggregate estimates of 1.5% and 0.8% for BP-I and BP-II, respectively, but with a far wider range of estimates than those reported here. In fact, variation in prevalence rates in these studies was attributed primarily to differences in the diagnostic interviews and definitions that were used to characterize bipolar disorder 6. The use of common diagnostic definitions in the WMH reduces the methodologic diversity that has hindered international prevalence estimates and that has prevented accurate descriptions of the personal and economic impact of this disorder12.

These data also provide the first international evidence that supports the validity of the spectrum concept of bipolarity. There was a direct association between increasingly restrictive definitions of bipolar disorder and indicators of clinical severity including symptom severity, role impairment, comorbidity, suicidality and treatment. For example, the proportion of mood episodes rated as clinically severe increased from 42.5% for subthreshold BP to 68.8% for BP-II to 74.5% for BP-I, and the proportion of cases reporting severe role impairment ranged from 46.3% for subthreshold BP to 57.1% for BP-I. The finding that more than half of those with bipolar disorder in adulthood date their onset to adolescence highlights the importance of early detection and intervention, and possibly prevention of subsequent comorbid disorders. Since the average age at onset of bipolar disorder occurs at one of the most critical periods of educational, occupational, and social development, its consequences often lead to lifelong disability.

These findings also confirm those of previous epidemiologic surveys that have highlighted pervasive comorbidity between bipolar disorder and other mental disorders 11, 31. Despite the differences in prevalence rates of comorbid disorders across countries, nearly three-quarters of those with BP-I or BP-II, and more than half of those with bipolar spectrum disorders have a history of three or more disorders. With respect to specific types of conditions, the association of bipolar disorder with anxiety disorders, particularly panic attacks, was notable; 62.9% of those in the bipolar spectrum have an anxiety disorder, with nearly half reporting panic attacks, and about one-third meeting criteria for a phobic disorder. Confirmation of a strong link between bipolar disorder and anxiety is particularly interesting in light of results from prospective studies of adolescents32 and follow-up studies of children of bipolar parents suggesting that anxiety disorders may constitute an early form of expression of the developmental pathway of bipolar disorders 33, 34.

There was striking similarity in patterns of comorbidity of bipolar spectrum disorders with substance use disorders despite large differences in cross-national prevalence rates of substance use and abuse. The strong association of bipolar disorder with substance use disorders has also been widely described in both community and clinical samples35. Recent findings from a 20-year prospective cohort study revealed a dramatic increase in risk of alcohol dependence associated with symptoms of mania and bipolar disorder in early adulthood 36. This suggests that bipolar disorder can be considered a risk factor for the development of substance use disorders, which has important implications for prevention efforts. These findings also support the need for careful probing of a history of bipolarity among those with substance use disorders.

Finally, the large proportion of those with severe symptoms and role impairment highlights the serious nature of bipolar disorder. Three-quarters of those with BPS reported severe levels of depressive symptoms and a comparable magnitude of severe role impairment. Most striking, one in every 4–5 person with BPD had made suicide attempts. When taken together with the early age at onset and strong association with other mental disorders, these results provide further documentation of the individual and societal disability associated with this disorder 16, 37, 38. In light of the disability associated with bipolar disorder, the lack of mental health treatment among those with bipolar disorder, particularly in low income countries, is alarming. Only one-quarter of those with bipolar disorder in low income countries, and only half of those in high income countries, had contacted mental health services. Previous findings of service use in the WMH surveys described the large gap between the burden of mental disorders and mental health care in the studies participating in the WMH survey 21. However, it is notable that the majority of those with BP disorder received treatment in the mental health sector, even in low income countries.

Interpretations of our findings must take account of the following conceptual and methodological issues. First, the surveys are cross-sectional so the findings are based on retrospective recall of symptoms and their correlates. Second, despite the use of common interview and diagnostic methods, there was still substantial cross-national variation in the rates of BPS. Although it is possible that these differences reflect real variation in prevalence perhaps due to higher false negatives in countries with greater stigma associated with mental illness, further inspection of these differences suggested that there was also variation in the translation, implementation and quality control in some countries that may have led to reduced prevalence rates. Although we found evidence for the validity of the diagnosis of bipolar spectrum based on the CIDI compared with clinical reappraisal interviews (k=.94)20, comparable clinical validation studies were not carried out in all of the participating WMH countries. Third, comparisons across countries may be limited because of variability in the availability of mental health treatment.

There are also several features of the WMH Survey Initiative that represent advances over prior cross-national studies in psychiatric epidemiology. First, the WMH initiative includes far larger representation of several regions of the world including low income countries. Second, the high degree of coordination across studies enhanced the validity of the cross-national comparisons. Third, the inclusion of standardized methods for assessing severity and role impairment facilitates estimation that can provide a context for the public health significance of the prevalence estimates.

These findings demonstrate the important growth of international collaborations that permit investigation of cultural and regional differences in prevalence and risk factors for mental disorders. Recent efforts such as the proposal of a common global nomenclature to define the course and outcome in bipolar disorders as proposed by a task force under the auspices of the International Society for Bipolar Disorders39 should facilitate outcome studies across geographies. Contemporary issues concerning bipolar disorder that warrant further study include: further evaluation of the thresholds and boundaries of bipolar disorder; better integration of adult and child epidemiology of bipolar disorder and its evolution in light of its onset in adolescence, and further investigation of explanations for the patterns of comorbidity between bipolar disorder with other disorders. In summary, this paper reports the first data on the prevalence and correlates of the full spectrum of bipolar disorder in a series of nationally representative surveys using common methodology. As such, they document the magnitude and major impact of bipolar disorder worldwide and underscore the urgent need for increased recognition and treatment facilitation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The WMH Surveys are carried out in conjunction with the World Health Organization World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative. We thank the WMH staff for assistance with instrumentation, fieldwork, and data analysis. These activities were supported by the United States National Institute of Mental Health (R01MH070884), the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the Pfizer Foundation, the US Public Health Service (R13-MH066849, R01-MH069864, and R01 DA016558), the Fogarty International Center (FIRCA R03-TW006481), the Pan American Health Organization, the Eli Lilly & Company Foundation, Ortho-McNeil Pharmaceutical, Inc., GlaxoSmithKline, Sanofi Aventis and Bristol-Myers Squibb. A complete list of WMH publications can be found at http://www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/wmh/. The São Paulo Megacity Mental Health Survey is supported by the State of São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP) Thematic Project Grant 03/00204-3. The Bulgarian Epidemiological Study of common mental disorders EPIBUL is supported by the Ministry of Health and the National Center for Public Health Protection. The Shenzhen Mental Health Survey is supported by the Shenzhen Bureau of Health and the Shenzhen Bureau of Science, Technology, and Information. The Colombian National Study of Mental Health (NSMH) is supported by the Ministry of Social Protection. The WMHI was funded by WHO (India)and helped by Dr R Chandrasekaran, JIPMER. The World Mental Health Japan (WMHJ) Survey is supported by the Grant for Research on Psychiatric and Neurological Diseases and Mental Health (H13-SHOGAI-023, H14-TOKUBETSU-026, H16-KOKORO-013) from the Japan Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. The Lebanese National Mental Health Survey (LEBANON) is supported by the Lebanese Ministry of Public Health, the WHO (Lebanon), Fogarty International, anonymous private donations to IDRAAC, Lebanon, and unrestricted grants from Janssen Cilag, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Roche, and Novartis. The Mexican National Comorbidity Survey (MNCS) is supported by The National Institute of Psychiatry Ramon de la Fuente (INPRFMDIES 4280) and by the National Council on Science and Technology (CONACyT-G30544- H), with supplemental support from the PanAmerican Health Organization (PAHO). Te Rau Hinengaro: The New Zealand Mental Health Survey (NZMHS) is supported by the New Zealand Ministry of Health, Alcohol Advisory Council, and the Health Research Council. The Romania WMH study projects "Policies in Mental Health Area" and "National Study regarding Mental Health and Services Use" were carried out by National School of Public Health & Health Services Management (former National Institute for Research & Development in Health), with technical support of Metro Media Transilvania, the National Institute of Statistics-National Centre for Training in Statistics, SC. Cheyenne Services SRL, Statistics Netherlands and were funded by Ministry of Public Health (former Ministry of Health) with supplemental support of Eli Lilly Romania SRL. The US National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) is supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH; U01-MH60220) with supplemental support from the National Institute of Drug Abuse (NIDA), the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF; Grant 044708), and the John W. Alden Trust. This work was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Mental Health. The views and opinions expressed in this report are those of the authors and should not be construed to represent the views of any of the sponsoring organizations, agencies, or US Government.

Dr. Kessler has been a consultant for GlaxoSmithKline Inc., Kaiser Permanente, Pfizer Inc., Sanofi-Aventis, Shire Pharmaceuticals, and Wyeth-Ayerst; has served on advisory boards for Eli Lilly & Company and Wyeth-Ayerst; and has had research support for his epidemiological studies from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly & Company, GlaxoSmithKline, Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceuticals, Ortho-McNeil Pharmaceuticals Inc., Pfizer Inc., and Sanofi-Aventis.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement:

Dr Merikangas reports no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Organization WH. The World Health Report 2002: Reducing Risks, Promoting Healthy Life. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2002. Oct 30, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weissman MM, Bland RC, Canino GJ, et al. Cross-national epidemiology of major depression and bipolar disorder. Jama. 1996 Jul 24–31;276(4):293–299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bauer M, Pfennig A. Epidemiology of bipolar disorders. Epilepsia. 2005;46:8–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2005.463003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pini S, de Queiroz V, Pagnin D, et al. Prevalence and burden of bipolar disorders in European countries. European Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005 Aug;15(4):425–434. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2005.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sherazi R, McKeon P, McDonough M, Daly I, Kennedy N. What's new? The clinical epidemiology of bipolar I disorder. Harvard Review of Psychiatry. 2006 Nov-Dec;14(6):273–284. doi: 10.1080/10673220601070047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Waraich P, Goldner EM, Somers JM, Hsu L. Prevalence and incidence studies of mood disorders: A systematic review of the literature. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry-Revue Canadienne De Psychiatrie. 2004 Feb;49(2):124–138. doi: 10.1177/070674370404900208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goodwin F, Jamison K. Manic-Depressive Illness. 2nd ed. Oxford University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bauer M, Pfennig A. Epidemiology of bipolar disorders. Epilepsia. 2005;46(Suppl 4):8–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2005.463003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Merikangas K, Pato M. Recent Developments in the Epidemiology of Bipolar Disorder in Adults and Children: Magnitude, Correlates, and Future Directions. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2009;16(2):121–133. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gureje O, Lasebikan VO, Kola L, Makanjuola VA. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of mental disorders in the Nigerian Survey of Mental Health and Well-Being. Br J Psychiatry. 2006 May;188:465–471. doi: 10.1192/bjp.188.5.465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grant BF, Stinson FS, Hasin DS, et al. Prevalence, correlates, and comorbidity of bipolar I disorder and axis I and II disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005 Oct;66(10):1205–1215. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pini S, de Queiroz V, Pagnin D, et al. Prevalence and burden of bipolar disorders in European countries. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2005 Aug;15(4):425–434. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2005.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cooper JE, Kendell RE, Gurland B, Sharpe L, Copeland JRM, Simon R. Psychiatric diagnosis in New York and London: A comparative study of mental hospital admissions. London: Oxford University Press; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Angst J, Gamma A, Lewinsohn P. The evolving epidemiology of bipolar disorder. World Psychiatry. 2002 Oct;1(3):146–148. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Judd LL, Akiskal HS. The prevalence and disability of bipolar spectrum disorders in the US population: re-analysis of the ECA database taking into account subthreshold cases. J Affect Disord. 2003 Jan;73(1–2):123–131. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(02)00332-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Merikangas KR, Akiskal HS, Angst J, et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of bipolar spectrum disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007 May;64(5):543–552. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.5.543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zimmermann P, Bruckl T, Nocon A, et al. Heterogeneity of DSM-IV major depressive disorder as a consequence of subthreshold bipolarity. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009 Dec;66(12):1341–1352. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Angst J, Gamma A, Benazzi F, Ajdacic V, Eich D, Rossler W. Toward a re-definition of subthreshold bipolarity: epidemiology and proposed criteria for bipolar-II, minor bipolar disorders and hypomania. J Affect Disord. 2003 Jan;73(1–2):133–146. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(02)00322-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Angst J. The emerging epidemiology of hypomania and bipolar II disorder. J Affect Disord. 1998 Sep;50(2–3):143–151. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(98)00142-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kessler RC, Akiskal HS, Angst J, et al. Validity of the assessment of bipolar spectrum disorders in the WHO CIDI 3.0. J Affect Disord. 2006 Dec;96(3):259–269. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang PS, Angermeyer M, Borges G, et al. Delay and failure in treatment seeking after first onset of mental disorders in the World Health Organization's World Mental Health Survey Initiative. World Psychiatry. 2007 Oct;6(3):177–185. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Young RC, Biggs JT, Ziegler VE, Meyer DA. A rating scale for mania: reliability, validity and sensitivity. Br J Psychiatry. 1978 Nov;133:429–435. doi: 10.1192/bjp.133.5.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gracious BL, Youngstrom EA, Findling RL, Calabrese JR. Discriminative validity of a parent version of the Young Mania Rating Scale. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002 Nov;41(11):1350–1359. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200211000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Ibrahim HM, et al. The 16-Item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (QIDS), clinician rating (QIDS-C), and self-report (QIDS-SR): a psychometric evaluation in patients with chronic major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2003 Sep 1;54(5):573–583. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01866-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leon AC, Olfson M, Portera L, Farber L, Sheehan DV. Assessing psychiatric impairment in primary care with the Sheehan Disability Scale. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1997;27(2):93–105. doi: 10.2190/T8EM-C8YH-373N-1UWD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.First M, Spitzer R, Gibbon M, Williams J. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Non-patient Edition (SCID-I/NP) New York Biometrics Research, New York State Psychatric Institute; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kessler RC, Abelson J, Demler O, et al. Clinical calibration of DSM-IV diagnoses in the World Mental Health (WMH) version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (WMHCIDI) Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004;13(2):122–139. doi: 10.1002/mpr.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.SAS/STAT Software: Changes and Enhancements, Release 8.2 [computer program] Cary, NC: SAS Publishing; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Halli S, Rao K, Halli S. Advanced Techniques of Population Analysis. New York, NY: Plenum Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wolter K. Introduction to Variance Estimation. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Keller MB. Prevalence and impact of comorbid anxiety and bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(Suppl 1):5–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR, Buckley ME, Klein DN. Bipolar disorder in adolescence and young adulthood. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2002 Jul;11(3):461–475. vii. doi: 10.1016/s1056-4993(02)00005-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Duffy A, Alda M, Crawford L, Milin R, Grof P. The early manifestations of bipolar disorder: a longitudinal prospective study of the offspring of bipolar parents. Bipolar Disord. 2007 Dec;9(8):828–838. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2007.00421.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Henin A, Biederman J, Mick E, et al. Psychopathology in the offspring of parents with bipolar disorder: a controlled study. Biol Psychiatry. 2005 Oct 1;58(7):554–561. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Strakowski SM, DelBello MP. The co-occurrence of bipolar and substance use disorders. Clin Psychol Rev. 2000 Mar;20(2):191–206. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(99)00025-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Merikangas KR, Herrell R, Swendsen J, Rossler W, Ajdacic-Gross V, Angst J. Specificity of bipolar spectrum conditions in the comorbidity of mood and substance use disorders: results from the Zurich cohort study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008 Jan;65(1):47–52. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2007.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wittchen HU, Mhlig S, Pezawas L. Natural course and burden of bipolar disorders. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2003 Jun;6(2):145–154. doi: 10.1017/S146114570300333X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morgan VA, Mitchell PB, Jablensky AV. The epidemiology of bipolar disorder: sociodemographic, disability and service utilization data from the Australian National Study of Low Prevalence (Psychotic) Disorders. Bipolar Disord. 2005 Aug;7(4):326–337. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2005.00229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tohen M, Frank E, Bowden CL, et al. The International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) Task Force report on the nomenclature of course and outcome in bipolar disorders. Bipolar Disord. 2009 Aug;11(5):453–473. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2009.00726.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]