Abstract

Objectives

The aim of this study was to determine the prognostic significance of changes in parameters derived from diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) that occur in response to treatment with bevacizumab and irinotecan in patients with recurrent glioblastoma multiforme.

Methods

15 patients with recurrent glioblastoma multiforme underwent serial 1.5 T MRI. Axial single-shot echo planar DTI was obtained on scans performed 3 days and 1 day prior to and 6 weeks after initiation of therapy with bevacizumab and irinotecan. Apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) and fractional anisotropy (FA) maps were registered to whole brain contrast-enhanced three-dimensional (3D) spoiled gradient recalled and 3D fluid attenuation inversion recovery (FLAIR) image volumes. Anatomic image volumes were segmented to isolate regions of interest defined by tumour-related enhancement (TRE) and FLAIR signal abnormality (FSA). Mean ADC and mean FA were calculated for each region. A Bland–Altman repeatability coefficient was also calculated for each parameter based on the two pre-treatment studies. A patient was considered to have a change in FA or ADC after therapy if the difference between the pre- and post-treatment values was greater than the repeatability coefficient for that parameter. Survival was compared using a Cox proportional hazard model.

Results

DTI detected a change in ADC within FSA after therapy in nine patients (five in whom ADC was increased; four in whom it was decreased). Patients with a change in ADC within FSA had significantly shorter overall survival (p=0.032) and progression free survival (p=0.046) than those with no change.

Conclusion

In patients with recurrent glioblastoma multiforme treated with bevacizumab and irinotecan, a change in ADC after therapy in FSA is associated with decreased survival.

Genotypic heterogeneity within histologically indistinguishable tumours remains a major barrier to successful treatment of patients with high-grade primary brain tumours [1]. Because of this heterogeneity, only a minority of individual tumours are likely to respond to any given chemotherapeutic agent [2]. Early identification of non-responders would allow potentially more effective therapy to be instituted while minimising the morbidity and financial cost associated with prolonged, ineffective treatment. Current assessment of therapeutic efficacy relies on changes in cross-sectional area estimated weeks to months after the completion of a treatment protocol [3,4]. Unfortunately, patients with aggressive tumours may experience significant disease progression with related morbidity and mortality before therapy can be evaluated and altered using this approach. Biomarkers of treatment response that are independent of late changes in tumour volume will be crucial for optimal treatment of this patient group.

Diffusion-weighted MRI (DWI) can be used to characterise early tissue microstructural changes associated with cell death [4,5]. Since parameters derived from DWI can provide a quantitative assessment of such effects, there is increasing interest in this technique as a biomarker of therapeutic efficacy. Although there is good evidence that DWI can be used to characterise treatment effects, the optimal parameter and region of interest are yet to be determined [4,6-12].

The preponderance of studies on this subject has quantified the apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) within regions of interest defined by abnormal tumour-related enhancement [6,9,11]. In vivo, the ADC is primarily determined by cell density [4,8,13,14]. As a result, changes in the ADC are sensitive to early alterations in tissue microstructure related to cell death; these changes include cell swelling and loss of membrane integrity associated with early necrosis as well as cell shrinkage due to apoptosis [11,15]. Indeed, it has been demonstrated that changes in the ADC within enhancing regions of interest can be used to identify the response to chemotherapy earlier than standard MRI [9]. Recent evidence, however, suggests the importance of non-enhancing, infiltrative tumour, as defined on fluid attenuation inversion recovery (FLAIR) images, with respect to tumour progression [16,17]. This non-enhancing component of tumour seems to be of particular relevance to patients treated with anti-angiogenesis agents [16,17]. Since the ADC is sensitive to variations in vasogenic oedema (increasing oedema tends to decrease cell density), in addition to the aforementioned direct effects on tumour cells, we hypothesise that the ADC would be an ideal parameter to characterise the effects of treatment within regions of interest defined by abnormal tumour-related FLAIR signals.

Although there are few data in patients with brain tumours, there is some evidence that parameters of diffusion anisotropy derived from diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) may more accurately depict early changes in brain tissue microstructure than the ADC in central nervous system (CNS) diseases [18]. Fractional anisotropy (FA) is a measure of the degree of directional variation of the diffusion of water protons. Like the ADC, FA has been shown to correlate with cell density [7,18,19], but FA provides additional information regarding the integrity and alignment of parenchymal fibre tracts [20]. A recent study in patients with primary brain tumours demonstrated increasing FA across the study population within regions of interest defined by tumour-related contrast enhancement as early as 1 day after initiation of chemotherapy [12]. This same study failed to detect a significant change in the ADC at the same time point, raising the possibility that FA may be a more sensitive parameter to early treatment response.

Although these preliminary results are promising, the significance of such changes with respect to patient survival has not been widely studied. In addition, there are very few data regarding the test–retest reproducibility of these parameters in patients with primary brain tumours, information which is crucial for understanding whether changes in these parameters can be used to guide therapy. In particular, an understanding of the magnitude of variability intrinsic to the method will be required to ascribe significance to changes in these parameters that occur after therapy in an individual patient.

The goal of this study is to use the repeatability of ADC and FA derived from DTI to devise a method by which prognostic significance can be assigned to changes in these parameters that occur after therapy in patients with glioblastoma multiforme. In particular, we prospectively identified the following two null hypotheses:

Patients with an increase in FA within regions of interest defined by tumour-related enhancement will not survive longer than those with no change or a decrease in FA.

Patients with a change in ADC within regions of interest defined by an abnormal FLAIR signal will not survive longer than those with no change.

Although it may seem counterintuitive to evaluate the significance of any change in the ADC without respect for direction, there is evidence that both increasing and decreasing the ADC may reflect a clinically relevant treatment response [9,11].

Methods and materials

Patient group

This Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act-compliant prospective study was approved by the local institutional review board. Informed consent was obtained. 20 patients were enrolled with the following inclusion criteria: (a) the candidate was referred for a pathologically proven diagnosis of Grade IV astrocytoma; (b) the candidate had experienced treatment failure as defined by standard criteria [3] before entering the study; (c) the candidate was older than 18 years; (d) there was an interval of at least 6 weeks between prior surgical resection and study enrolment; (e) there was an interval of at least 4 weeks between prior radiotherapy or chemotherapy and enrolment on this protocol, unless unequivocal evidence of tumour progression after radiotherapy or chemotherapy; (f) the Karnofsky score was ≥60%; (g) haematocrit was >29%, platelets were >125 000 cells dl–1 and serum creatinine was <1.5 mg dl–1; (h) those patients on corticosteroids must have been on a stable dose for 1 week prior to entry, and the dose was not be escalated over entry dose level during the imaging portion of the study (i.e. during the first 6 weeks after the first MR examination); (i) there was no evidence of haemorrhage on the baseline MRI or CT scan; and (j) they were MRI compatible. Exclusion criteria were as follows: (a) pregnancy or breast-feeding; (b) comedication that could interfere with study results, e.g. immunosuppressive agents other than corticosteroids; (c) active infection; (d) more than three prior recurrences; (e) evidence of CNS haemorrhage on baseline MRI on CT scan; (f) blood pressure >150/100 mmHg; (g) history of myocardial infarction within 6 months; (h) history of stroke within 6 months; (i) evidence of bleeding diathesis, coagulopathy or taking acetylsalicylic acid, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or clopidogrel; (j) major surgical procedure, open biopsy or significant traumatic injury within 28 days prior to day 0, anticipation of need for major surgical procedure during the course of the study; (k) minor surgical procedures, fine needle aspirations or core biopsies within 7 days prior to day 0; (l) serious, non-healing wound, ulcer or bone fracture; and (m) history of adverse reaction to gadolinium chelates.

Patients underwent serial MRI, including volumetric gadolinium-enhanced T1 weighted three-dimensional (3D) spoiled gradient recall echo, FLAIR and DTI on days 1 and 3 of the study without interval intervention or therapy. On day 4, patients began a chemotherapeutic regimen consisting of bevacizumab (Avastin; Genentech Biooncology, San Francisco, CA) and irinotecan (Camptosar; Pfizer Inc, New York, NY). Bevacizumab was dosed at 10 mg kg–1. Irinotecan was dosed at 340 mg m–2 for patients taking enzyme-inducing anti-epileptic drugs and 125 mg m–2 for all other patients. Irinotecan was co-administered with corticosteroids. All patients underwent repeat imaging with identical sequences 6 weeks after initiation of therapy. Clinical follow up and survival status was documented up to 20 months after the date of initial MRI. Tumour progression during the study follow-up period was defined by neuro-oncologists blinded to the DTI findings using the Macdonald criteria [3]. Overall and progression-free survival were measured from the date of initial MRI.

MRI

MRI was performed on a single 1.5 T scanner (Siemens Avanto; Siemens, Berlin, Germany). Patients received intravenous injections of gadolinium-diethylenetriamine penta-acetic acid (Gd-DTPA) (Magnevist; Bayer Schering Pharma, Berlin–Wedding, Germany); the dose of Gd-DTPA was 0.1 mmol kg–1. Sequences obtained included (a) axial single-shot echo planar DTI [repetition time (TR)/echo time (TE) (ms), 6000/100; flip angle, 90 degrees; 4 acquisition (NEX; number of excitations), 4; matrix, 128×128; voxel size (mm), 1.72×1.72×5]; (b) sagittal contrast-enhanced three-dimensional (3D) fast low angle shot [FLASH; TR/TE (ms), 8.6/4.1; flip angle, 20 degrees; 1 acquisition (NEX, 1); matrix, 256×256; voxel size, 1×1×1 mm; images obtained approximately 8 min after administration of intravenous contrast]; and (c) sagittal 3D FLAIR [TR/TE/inversion time (ms), 6000/353/2200; flip angle, 180 degrees; 1 acquisition (NEX, 1); matrix, 256×216; voxel size, 1×1×1 mm]. For DTI, a total of 13 image sets were acquired: one without diffusion weighting and 12 with non-collinear diffusion weighting gradients and a b value of 1000 s mm–2. Integrated parallel imaging techniques with an acceleration factor of 2 were used. All DTI was performed prior to contrast administration.

Calculation of diffusion indices

For each patient, ADC and FA maps from each time point were created using JDTI, a Java-based software tool designed to analyse DTI (http://dblab.duhs.duke.edu, Daniel Barboriak, Department of Radiology, Duke University Medical Center, NC). JDTI is implemented as a plug-in to ImageJ, an open source image analysis program (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/, Wayne Rasband, Research Services Branch, National Institute of Mental Health, MD).

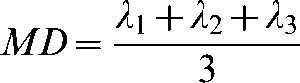

For each voxel, a diffusion tensor matrix was derived from the imaging data. After diagonalisation of the matrix, diffusion tensor eigenvalues were obtained. ADC (defined as the mean diffusivity; MD) and FA were derived for each pixel according to the following equations:

|

(1) |

|

(2) |

where λ1, λ2, and λ3 are eigenvalues describing the magnitude of diffusivity in the orthogonal directions of maximum, median and minimum diffusion, respectively.

Image analysis

All imaging data were obtained prospectively and analysed retrospectively. For each time point, ADC and FA maps were aligned to that patient's contrast-enhanced FLASH and FLAIR image volumes using a rigid body normalised mutual information algorithm provided by the National Library of Medicine Insight Segmentation and Registration Toolkit (MultiResMIRegistration, www.itk.org). Specifically, the trace (an image taken as the average of the 12 diffusion-weighted directions) was used as the source for image registration. The transform matrix derived from this registration was then applied to the ADC and FA maps.

Contrast-enhanced FLASH and FLAIR image volumes were segmented using a semi-automated technique to isolate volumes of interest defined by abnormal tumour-related enhancement (TRE) and FLAIR signal abnormality (FSA). Segmentation was performed by two board-certified radiologists blinded to the survival data. Segmentation was implemented using macro-scripts and plug-in extensions to ImageJ as follows: (1) images from the isotropic SPGR and FLAIR data sets were smoothed using an edge-preserving technique (Anisotropic diffusion filtering, http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/plugins/anisotropic-diffusion.html) [21]; (2) eligible pixels were defined as having signal intensity greater than 2 SDs (standard deviations) above the mean within regions of interest drawn in normal-appearing corpus callosum on contrast-enhanced FLASH images for TRE, or within the caudate head contralateral to the largest area of visible tumour on FLAIR images for FSA; (3) for the FLAIR images, a seed point was placed manually within the FLAIR abnormality overlying tumour-related enhancement; a connecting region algorithm was used to isolate those voxels of FLAIR abnormality in contiguity with tumour-related enhancement; (4) subsets of pixels which were clearly not part of the tumour-related abnormality were removed manually. On the FLASH images, areas of intrinsic T1 hyperintensity (i.e. fat and mineralisation) and non-tumoural (i.e. vascular) enhancement were removed. Linear pachymeningeal enhancement measuring less than 5 mm in thickness in contiguity with the craniotomy site was also removed as it was considered probably post-operative in nature. On the FLAIR images, hyperintense fluid collections and regions clearly related to flow-related artefacts were removed; and (5) the regions of tumour-related abnormality from each slice were summed to create volumes of tumour-related abnormality.

FLAIR analysis

This portion of the study was performed after initial results suggested a relationship between ADC and survival. In order to clarify these initial results, co-registered pre- and post-therapy FLAIR image volumes were analysed independently by two board-certified neuroradiologists blinded to the survival data. Each patient was scored according to worsening extent of new regions of FLAIR signal abnormality. Inconsistencies were settled by consensus. Since changes in diffusion parameters within TRE had no detectable prognostic value in this study, a comparable analysis of changes in the extent of tumour-related enhancement was not performed.

Data analysis

Mean ADC and FA were calculated for each time point within both TRE and FSA (Figure 1). Using the data derived from DTI performed on days 1 and 3 (both obtained prior to treatment), a Bland–Altman repeatability coefficient was calculated [22]. A patient was considered to have a change in FA or ADC after therapy if the difference between the pre- and post-treatment values was greater than the repeatability coefficient for that parameter. The repeatability coefficient for FA within TRE was 0.0196 and for ADC within FSA was 0.071×10−3, as previously reported [23].

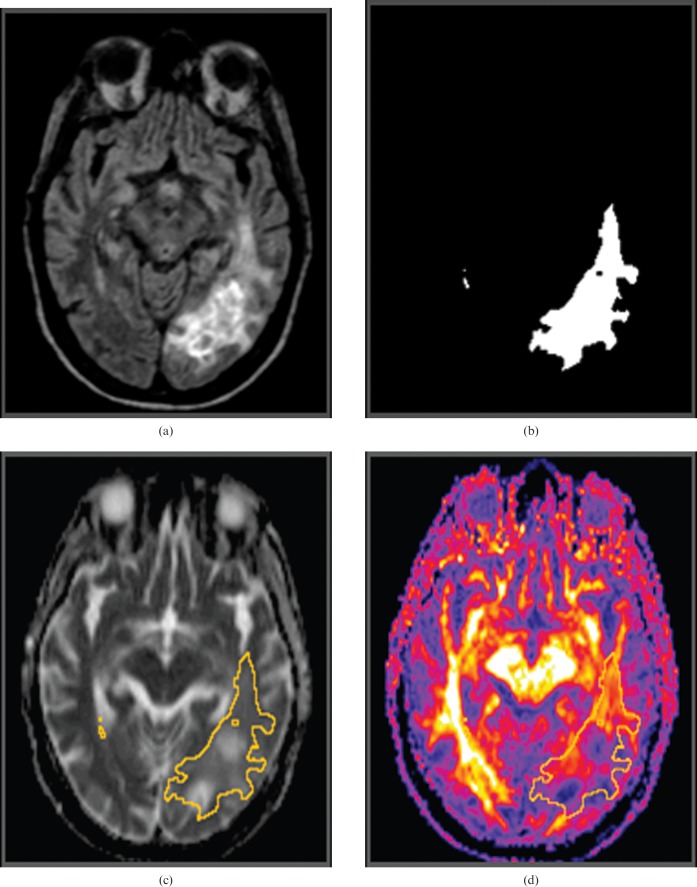

Figure 1.

Image analysis. Three-dimensional (3D) fluid attenuation inversion recovery (FLAIR) image obtained prior to initiation of treatment (a) demonstrates a left parieto-occipital glioblastoma multiforme. The 3D FLAIR image set was segmented to isolate a region of interest defined by FLAIR signal abnormality (FSA). (b) The mean apparent diffusion coefficient and mean fractional anisotropy (FA) were then calculated within FSA from co-registered (c) ADC and (d) FA maps, respectively.

Survival was compared using a Cox proportional hazard model.

Results

Patient demographics

All imaging was performed during the time period April 2006 through January 2007. Of the 18 patients initially enrolled in the study, one patient was excluded from analysis owing to insufficient size of the enhancing and FLAIR regions of interest (<1 cm in greatest dimension). One patient was excluded for significant Nyquist ghost artefact; this artefact has been shown to degrade quantification of ADC [24]. Finally, one patient was excluded owing to the use of incorrect DTI parameters (technologist error). The final study group comprised 15 patients (9 men and 6 women, age range 38–62 years).

Apparent diffusion coefficient

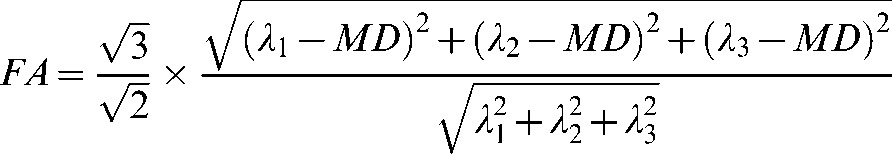

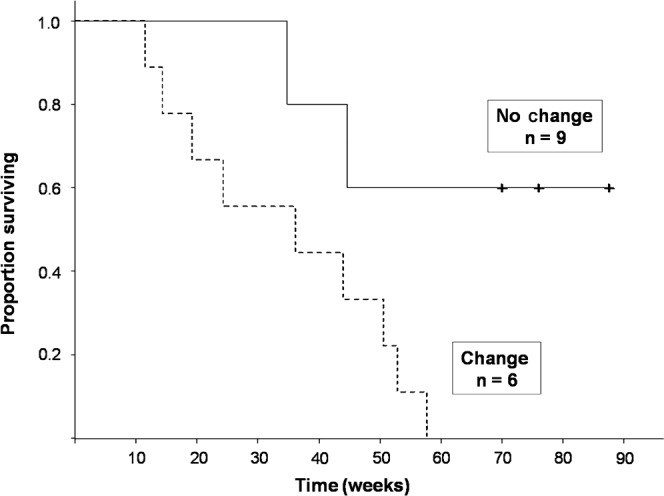

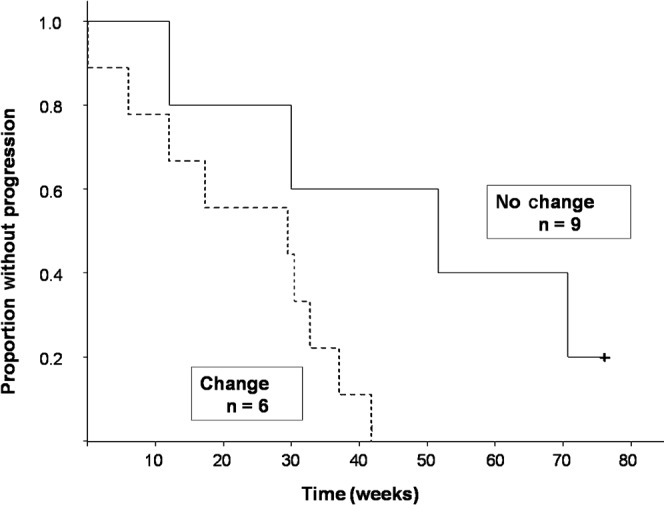

DTI detected a change in ADC within FSA after therapy (five decreased, four increased) in nine patients. Median survival in patients with a significant change in ADC was 36.1 (95% confidence interval 19.1–50.6) weeks. Median survival has not been reached in the patient group with no change. Patients with a change in ADC within FSA had a 4.8 times greater risk of death during the follow-up period (p=0.03) than patients with no change (Figure 2). Patients with a change in ADC within FSA also had a 4.3 times greater risk of progression (p=0.046) than patients with no change (Figure 3). The direction of change in the ADC (increased vs decreased) did not affect the relationship to overall survival (p=0.96).

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier survival curve. Patients with a change in the apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) within regions of interest defined by fluid attenuation inversion recovery signal abnormality after treatment had significantly decreased overall survival compared with those with no change in ADC (p=0.032).

Figure 3.

Kaplan–Meier survival curve. Patients with a change in apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) within regions of interest defined by fluid attenuation inversion recovery signal abnormality after treatment had significantly decreased progression-free survival compared with those with no change in ADC (p=0.046).

Fractional anistropy

DTI detected a change in FA within TRE after therapy (all increased) in seven patients. No significant difference in either overall or progression-free survival was detected when patients with a change in FA within TRE after therapy were compared with those without.

FLAIR analysis

This portion of the study was performed to clarify the relationship between ADC and survival. It was initially hypothesised that the prognostic significance of changes in ADC within FSA might reflect interval tumour growth on FLAIR images (since new regions of abnormality are likely to have an inherently different ADC than more well-established tumour [25]). No patient had a decrease in the volume of their FLAIR abnormality. Four patients had no interval change. The extent of FLAIR abnormality increased in 11 patients. There was no significant association between patients with a change in ADC and patients who developed new FLAIR signal abnormality on the post-therapy scan.

Discussion

In this study, a change in mean ADC after therapy within regions defined by an abnormal FLAIR signal was associated with decreased survival in patients treated with bevacizumab and irinotecan. These data provide evidence that quantitative analysis of parameters derived from DTI can provide an early, clinically relevant assessment of therapeutic efficacy in patients with recurrent glioblastoma multiforme. Furthermore, these data suggest that any change in mean ADC, regardless of direction, had the same significance with regard to clinical outcome. Together, these findings highlight the importance of tumour stasis, to be distinguished from tumour response, in the successful treatment of malignant glioma with anti-angiogenesis agents. This conclusion is in concert with previous studies that have demonstrated the presence of stable disease to be a favourable prognostic factor [3,6,9].

Since new regions of abnormality are likely to have an inherently different ADC than better-established tumour [25], it was initially hypothesised that interval tumour growth on FLAIR images might explain the relationship between a change in ADC and survival. Therefore, to further clarify our results, a comparison of pre- and post-therapy FLAIR images was performed to assess for new regions of FLAIR signal abnormality. No association was found between patients with a significant change in ADC and patients who developed new FLAIR abnormalities on the post-therapy scan; thus, the observed changes in ADC are likely to reflect microstructural alterations within an existing tumour.

The exact histopathological correlate of these changes remains the subject of speculation. A decrease in ADC may occur secondary to an increase in tumour cell density [13], possibly correlating with tumour progression. It is possible, however, that an increase in ADC may also indicate tumour progression. Astrocytic growth is characterised initially by infiltration of sparse tumour cells, accompanied by vasogenic oedema, along intact white matter tracts [18,25]. It is only at a relatively late stage that progressive tumour proliferation destroys or displaces all intact native architecture from a given area [7]. We suggest that increasing ADC could reflect worsening vasogenic oedema associated with early progressive infiltration of tumour cells at a time before proliferation can significantly impact the overall cell density of the infiltrated brain tissue.

Several clinical studies have established the ability of DWI to detect changes after therapy within high-grade primary brain tumours, some as early as 24 h after initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy [10,11,26]. In most instances, however, the clinical significance of such changes has not been evaluated. Work by Hamstra et al [9] has demonstrated the predictive value of functional diffusion maps with regard to survival. In that study, patients with a larger fractional volume of tumour in which ADC changed after therapy (determined on a pixel-by-pixel basis) survived longer; lack of change was associated with poorer prognosis. Direct comparison with our results is difficult, given the markedly disparate methodologies used for image analysis. In particular, calculation of mean diffusion parameters in our study has the potential to obscure spatially heterogeneous alterations in the ADC. Additional differences between the two studies could contribute to the discrepant results, including (1) the chemotherapeutic regimen (variable and at the discretion of the treating physician in Hamstra et al [9]) (2) the definition of change (determined using post-therapeutic ADC maps in normal-appearing brain structures in Hamstra et al [9]); and (3) the timing of imaging follow-up (3 weeks post therapy in Hamstra et al [9]).

The issue of timing is of particular relevance to this and similar studies as the cellular processes underlying successful treatment have varied, sometimes opposing, effects on diffusion over time. Cell death mediated by necrosis results in early cell swelling and restricted diffusion [14]. However, swelling is followed by loss of membrane integrity and cell lysis, processes which result in greater water mobility [4]. Apoptosis, by comparison, is associated with early cell shrinkage and thus increased ADC [15]. Later, reductions in tumour bulk tend to augment ADC [8] while dynamic reorganisation of the extracellular space may be associated with relatively restricted diffusion [11]. Further complicating matters, the specific effects of a given chemotherapeutic agent may not be constant over time [27]. In sum, the time course of post-therapeutic changes in tumour water mobility is potentially quite intricate and further study is necessary to determine the optimal timing for treatment assessment.

Traditional methods used to assess treatment response focus on the components of tumour that demonstrate contrast enhancement [3]. Similarly, the preponderance of clinical trials that have employed DWI in this regard has measured parameters within enhancing regions of interest [9,11]. Recent studies, however, have suggested the importance of non-enhancing, infiltrative tumour, defined by signal abnormality on FLAIR sequences, with respect to imaging tumour progression [16,17]. Such non-enhancing tumour seems to be of particular relevance in patients treated with anti-angiogenesis agents [16,17]. Our findings highlight the clinical significance of interval changes in water mobility occurring within such non-enhancing regions of tumour-related abnormality in patients with glioblastoma multiforme.

Our analysis also provides an example of how repeatability can be used to investigate the clinical significance of changes in parameters derived from DTI after therapy. We calculated a Bland–Altman repeatability coefficient for each parameter based on two pre-treatment scans. For an individual patient, changes after therapy greater than the repeatability coefficient are unlikely to be related to intramethod variability in the measurement of ADC and FA; only measured changes of this magnitude or greater were considered to reflect a real change in the underlying parameter. If these results can be replicated in a larger multicentre trial, this kind of analysis would allow parameters derived from DTI to guide therapy in individual patients. It is important to note that our findings do not imply that change of lesser magnitude is without clinical significance, only that such change will not be reliably detected within an individual patient.

Although the repeatability of ADC has been used as a component of image analysis in prior studies [11], our analysis differs from these in certain respects. In prior studies, the repeatability of ADC within contralateral, normal appearing brain parenchyma calculated from pre- and post-therapy diffusion maps [11] was used to define regions of changed ADC in the tumour. One potential confounder using this approach is that standard therapies, including glucocorticoids, can alter brain ADC, even within normal appearing structures [28-31]. Furthermore, it is not clear that the reproducibility of diffusion parameters in normal brain is similar to that in regions of tumour-related abnormality. These results underscore the need for a more thorough understanding of the reproducibility of parameters derived from DTI prior to widespread application of this technology. In particular, a study that measures the reproducibility of these parameters across a variety of MR instrumentation would be of great practical value towards the development of a larger, multicentre trial.

This study has several limitations. First, this is a small pilot study of a highly selected cohort of patients with recurrent glioblastoma multiforme. Extrapolation of these results to patients with other types of CNS malignancy may not be valid and will require further study. Second, diffusion parameters were evaluated in the study population after administration of combination therapy with bevacizumab and irinotecan. It is not clear, therefore, how these results will apply to larger patient groups that may have undergone more diverse therapies. In a related issue, administration of corticosteroids has the potential to alter diffusion parameters within brain tumours and peritumoral oedemas [32]. Controlling for variation in steroid dose over time will present a significant obstacle to implementation of our assessment paradigm. Finally, no biopsies were obtained to determine the pathological diagnoses underlying the imaging findings in our patients. For this reason, it was not possible to distinguish tumour-related from treatment-related brain parenchymal abnormalities. Although this diagnostic distinction has significant consequences regarding management of these patients, it did not seem in this study to affect the prognostic implications of the imaging findings.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our study has demonstrated the potential for quantitative measurements derived from DTI to provide an early, clinically relevant assessment of therapeutic efficacy in patients with recurrent high-grade glioma. If these findings can be validated in larger studies, such measurements may provide the basis for useful biomarkers of patient outcome in clinical trials.

References

- 1.DeAngelis LM. Brain tumors. N Engl J Med 2001;344:114–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perry JR, Cairncross JG. Glioma therapies: how to tell which work? J Clin Oncol 2003;21:3547–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Macdonald DR, Cascino TL, Schold SC, Jr, Cairncross JG. Response criteria for phase II studies of supratentorial malignant glioma. J Clin Oncol 1990;8:1277–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chenevert TL, Stegman LD, Taylor JM, Robertson PL, Greenberg HS, Rehemtulla A, et al. Diffusion magnetic resonance imaging: an early surrogate marker of therapeutic efficacy in brain tumors. J Natl Cancer Inst 2000;92:2029–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Galons JP, Altbach MI, Paine-Murrieta GD, Taylor CW, Gillies RJ. Early increases in breast tumor xenograft water mobility in response to paclitaxel therapy detected by non-invasive diffusion magnetic resonance imaging. Neoplasia (New York) 1999;1:113–17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barker FG, 2nd, Prados MD, Chang SM, Gutin PH, Lamborn KR, Larson DA, et al. Radiation response and survival time in patients with glioblastoma multiforme. J Neurosurg 1996;84:442–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beppu T, Inoue T, Shibata Y, Kurose A, Arai H, Ogasawara K, et al. Measurement of fractional anisotropy using diffusion tensor MRI in supratentorial astrocytic tumors. J Neurooncol 2003;63:109–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chenevert TL, McKeever PE, Ross BD. Monitoring early response of experimental brain tumors to therapy using diffusion magnetic resonance imaging. Clin Cancer Res 1997;3:1457–66 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hamstra DA, Chenevert TL, Moffat BA, Johnson TD, Meyer CR, Mukherji SK, et al. Evaluation of the functional diffusion map as an early biomarker of time-to-progression and overall survival in high-grade glioma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2005;102:16759–64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mardor Y, Pfeffer R, Spiegelmann R, Roth Y, Maier SE, Nissim O, et al. Early detection of response to radiation therapy in patients with brain malignancies using conventional and high b-value diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging. J Clin Oncol 2003;21:1094–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moffat BA, Chenevert TL, Lawrence TS, Meyer CR, Johnson TD, Dong Q, et al. Functional diffusion map: a noninvasive MRI biomarker for early stratification of clinical brain tumor response. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2005;102:5524–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paldino MJ, Desjardins A, Vredenburgh JJ, Friedman HS, Barboriak DP. Treatment of patients with glioblastoma multiforme results in a rapid increase in fractional anisotropy. Chicago, IL: Radiologic Society of North America; 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guo AC, Cummings TJ, Dash RC, Provenzale JM. Lymphomas and high-grade astrocytomas: comparison of water diffusibility and histologic characteristics. Radiology 2002;224:177–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Le Bihan D. The ‘wet mind’: water and functional neuroimaging. Phys Med Biol 2007;52:R57–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee KC, Hamstra DA, Bhojani MS, Khan AP, Ross BD, Rehemtulla A. Noninvasive molecular imaging sheds light on the synergy between 5-fluorouracil and TRAIL/Apo2L for cancer therapy. Clin Cancer Res 2007;13:1839–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Norden AD, Young GS, Setayesh K, Muzikansky A, Klufas R, Ross GL, et al. Bevacizumab for recurrent malignant gliomas: efficacy, toxicity, and patterns of recurrence. Neurology 2008;70:779–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zuniga RM, Torcuator R, Jain R, Anderson J, Doyle T, Ellika S, et al. Efficacy, safety and patterns of response and recurrence in patients with recurrent high-grade gliomas treated with bevacizumab plus irinotecan. J Neurooncol 2009;91:329–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stadlbauer A, Ganslandt O, Buslei R, Hammen T, Gruber S, Moser E, et al. Gliomas: histopathologic evaluation of changes in directionality and magnitude of water diffusion at diffusion-tensor MR imaging. Radiology 2006;240:803–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beppu T, Inoue T, Shibata Y, Yamada N, Kurose A, Ogasawara K, et al. Fractional anisotropy value by diffusion tensor magnetic resonance imaging as a predictor of cell density and proliferation activity of glioblastomas. Surg Neurol 2005;63:56–61; discussion 61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goebell E, Fiehler J, Ding XQ, Paustenbach S, Nietz S, Heese O, et al. Disarrangement of fiber tracts and decline of neuronal density correlate in glioma patients—a combined diffusion tensor imaging and 1H-MR spectroscopy study. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2006;27:1426–31 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Perona P, Malik J. Scale-space and edge detection using anisotropic diffusion. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell 1990;12:629–39 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bland JM, Altman DG. Measuring agreement in method comparison studies. Stat Methods Med Res 1999;8:135–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Paldino MJ, Barboriak D, Desjardins A, Friedman HS, Vredenburgh JJ. Repeatability of quantitative parameters derived from diffusion tensor imaging in patients with glioblastoma multiforme. J Magn Reson Imaging 2009;29:1199–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Porter DA, Calamante F, Gadian DG, Connelly A. The effect of residual Nyquist ghost in quantitative echo-planar diffusion imaging. Magn Reson Med 1999;42:385–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goebell E, Paustenbach S, Vaeterlein O, Ding XQ, Heese O, Fiehler J, et al. Low-grade and anaplastic gliomas: differences in architecture evaluated with diffusion-tensor MR imaging. Radiology 2006;239:217–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Paldino MJ, Desjardins A, Vredenburgh JJ, Friedman HS, Barboriak DP. Repeatability of apparent diffusion coefficient and fractional anisotropy in patients with recurrent glioblastoma multiforme. Toronto, Canada: ISMRM; 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee KC, Hall DE, Hoff BA, Moffat BA, Sharma S, Chenevert TL, et al. Dynamic imaging of emerging resistance during cancer therapy. Cancer Res 2006;66:4687–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bastin ME, Carpenter TK, Armitage PA, Sinha S, Wardlaw JM, Whittle IR. Effects of dexamethasone on cerebral perfusion and water diffusion in patients with high-grade glioma. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2006;27:402–8 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bastin ME, Delgado M, Whittle IR, Cannon J, Wardlaw JM. The use of diffusion tensor imaging in quantifying the effect of dexamethasone on brain tumours. Neuroreport 1999;10:1385–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Minamikawa S, Kono K, Nakayama K, Yokote H, Tashiro T, Nishio A, et al. Glucocorticoid treatment of brain tumor patients: changes of apparent diffusion coefficient values measured by MR diffusion imaging. Neuroradiology 2004;46:805–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sinha S, Bastin ME, Wardlaw JM, Armitage PA, Whittle IR. Effects of dexamethasone on peritumoural oedematous brain: a DT-MRI study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psych 2004;75:1632–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Armitage PA, Schwindack C, Bastin ME, Whittle IR. Quantitative assessment of intracranial tumor response to dexamethasone using diffusion, perfusion and permeability magnetic resonance imaging. Magn Reson Imaging 2007;25:303–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]