Abstract

RhoA protein is involved in the Ca2+ sensitization of bronchial smooth muscle (BSM) contraction, and an upregulation of RhoA in BSMs has been suggested in allergic bronchial asthma. However, the mechanism of upregulation of RhoA remains poorly understood. In the present study, the transcriptional regulation of human RhoA gene was investigated in cultured human BSM cells stimulated with IL-13 and TNF-α, both of which have an ability to upregulate RhoA protein. Luciferase-based assay showed that the RhoA promoter activity was augmented by both IL-13 and TNF-α. The deletion studies revealed a significant level of promoter activity between the 112 bp upstream and the transcription start site, which contains the STAT6 (78–70 bp upstream) and NF-κB (84–74 bp upstream) binding regions. The promoter activity was also decreased significantly by the mutations of these regions. Thus, the current study for the first time characterized the transcriptional regulation of the human RhoA gene. The findings also suggest that STAT6 and NF-κB are important for the upregulation of RhoA in human BSM induced by IL-13 and TNF-α, both of which are major cytokines in the pathogenesis of allergic bronchial asthma.

Keywords: RhoA, STAT6, NF-κB, Airway hyperresponsiveness, IL-13, TNF-α

1. Introduction

Airway hyperresponsiveness (AHR) associated with heightened airway resistance and inflammation is an asthmatic characteristic feature. Although the importance of AHR in the pathogenesis of asthma has been suggested by its relevance to the severity of this disease, the pathophysiologic alterations leading to the hyperresponsiveness are unclear now. It has been demonstrated that smooth muscle responsiveness to contractile agonists was significantly increased in bronchial preparations from repeatedly antigen challenged rats [1]. It is thus important to understand the changes in the contractile signaling of airway smooth muscle cells associated with the disease for development of new types of asthma therapy.

Smooth muscle contraction is mainly regulated by an increase in cytosolic Ca2+ concentration in myocytes. Recently, additional mechanism, termed Ca2+ sensitization, has also been suggested to be involved in the agonist-induced smooth muscle contraction. It has been demonstrated that agonist stimulation increases myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity in permeabilized smooth muscles of the rat coronary artery [2], guinea pig vas deferens [3], canine trachea [4], and rat bronchus [5]. Although the detailed mechanism is not fully revealed, the involvement of RhoA, a monomeric GTP-binding protein, in agonist-induced Ca2+ sensitization has been suggested by many investigators [6]. Previously, we demonstrated that the Ca2+ sensitization of the bronchial smooth muscle (BSM) contraction was markedly augmented concomitantly with an increased expression of RhoA protein in the AHR rats and mice [7,8]. Moreover, an augmented RhoA-mediated Ca2+ sensitization of smooth muscle contraction has been reported in experimental animal models of diseases, such as hypertension [9–11], and coronary [2,12,13] and cerebral vasospasms [14,15]. It is thus possible that RhoA-mediated signaling is a crucial key for understanding the abnormal contraction of diseased smooth muscles.

IL-13 is a Th2 cytokine that has emerged as a critical regulator of inflammatory immune responses with key roles in asthma [16,17]. IL-13 can be detected in the bronchial tissue [18], nasal lavage fluid [19], and induced sputum [18] of asthmatics. Following segmental allergen challenge, bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid contains IL-13 mRNA [20] and protein [21], indicating that the cytokine is generated in the lungs in response to respiratory provocation. Transgene pulmonary overexpression of IL-13 in mice is associated with several key pathological features of airway inflammation and remodeling, also observed in patients with chronic severe asthma, including lymphocyte and eosinophil accumulation, mucus cell metaplasia, subepithelial fibrosis and AHR [22]. Several studies indicate the importance of direct effects on airway smooth muscle (ASM) and epithelial cells in causing AHR [23,24]. ASM cells express functional IL-13 receptors, and IL-13 is also linked to an augmented ASM contractility in rabbit tracheal strips [21].

On the other hand, TNF-α, one of the proinflammatory cytokines released from inflammatory cells, is directly linked to the airway inflammation and hyperresponsiveness [25]. TNF-α is elevated in the sputa and BAL fluids of patients with bronchial asthma [26,27]. Increased levels of TNF-α have also been detected in the BALFs of sensitized animals after challenge with antigen in mouse and guinea pig models of lung inflammation [28,29]. In addition, incubation of airway smooth muscle tissues with TNF-α augments contractile response to agonists in mice, guinea pigs and rats [30–32]. TNF-α blockade with anti-TNF-α antibody resulted in a significant inhibition of AHR without affecting airway eosinophilia and inflammation in mice [33].

Thus, both IL-13 and TNF-α might have an ability to cause BSM hyperresponsiveness. However, the mechanisms of IL-13- and TNF-α-induced BSM hyperresponsiveness are not clear. Here, we show that the associations of STAT6 and NF-κB with the proximal STAT6 site and NF-κB site in the RhoA promoter are required for RhoA upregulation induced by IL-13 or TNF-α in hBSMCs.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Chemicals

All biochemicals were of analytical grade and were purchased from commercial suppliers: recombinant human IL-13 (Peprotech, Paris, France), recombinant human TNF-α (Peprotech), and BMS-345541 (Sigma–Aldrich, MO). AS1517499 were kindly provided Astellas Pharma Inc. (Tokyo, Japan).

2.2. Cell culture and sample collection

Normal human BSM cells (hBSMCs; Cambrex Bio Science Walkersville, Inc., MD) were maintained in SmBM medium (Cambrex) supplemented with 5% FBS, 2 ng/mL human fibroblast growth factor-basic (hFGF-b), 0.5 ng/mL human epidermal growth factor (hEGF), 5 μg/mL insulin, 50 μg/mL gentamicin, and 50 ng/mL amphotericin B. Cells were maintained at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere (5% CO2), fed every 48–72 h, and passaged when cells reached 90–95% confluence. Then the hBSMCs (passages 6–9) were seeded in 6-well plates (Becton Dickinson Labware, NJ) and at a density of 3500 cells/cm2 and, when 80–85% confluence was observed, cells were cultured without serum for 24 h before addition of recombinant human IL-13 or recombinant human TNF-α. The culture technique was used in experiments involving stimulation with 100 ng/mL IL-13 or 10 ng/mL TNF-α or sterile PBS as its vehicle control for 24 h. AS1517499, a STAT6 inhibitor, or BMS-345541, an IKK inhibitor, was co-incubated with IL-13 or TNF-α. Cells were washed with PBS, immediately collected and disrupted with 1× SDS sample buffer (200 μL/well), and used for Western blot analyses. For RNA extraction, TRI Reagent™ (1 mL/well; Sigma–Aldrich) was added directly to the washed cells.

2.3. RNA interference

RNA interference was performed on hBSMCs using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen Life Technologies, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For target gene silencing, Silencer Select Validated small interference RNAs (siRNAs; Ambion, TX) targeting human p65 (GenBank Accesion No. NM 021975), human STAT6 (GenBank Accesion No. NM 003153), and negative control were diluted and stored according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The hBSMCs at 30–50% confluence were transfected with a final concentration of 50 nM of target siRNA or negative control. Cells were cultured without serum for 24 h before addition of recombinant human IL-13 or recombinant human TNF-α and analyzed 72 h after the transfection.

2.4. Real-time RT-PCR

The quantitative analyses of mRNA levels of RhoA were examined by real-time RT-PCR as described previously [34]. Briefly, total RNA was extracted from hBSMCs with a one-step guanidium–phenol–chloroform extraction procedure using TRI Reagent™. cDNAs were prepared from the total RNA (1.0 μg) by using QuantiTect Reverse Transcriptase (Qiagen, Germany) after incubation with gDNA wipeout buffer at 42 °C for 3 min to remove genomic DNA contamination. The reaction mixture (2 μL) was subjected to PCR (50 nM forward and reverse primers, iQ SYBR Green Supermix (BIO RAD, CA) in a final volume of 20 μL. The PCR primer sets used were as follows: Hs RHOA 1 SG QuantiiTect Primer Assay (Qiagen) for RhoA of human, 5′-GGAGCCAAAAGGGTCATCATCTC-3′ (sense) and 5′-AGGGATGATGTTCTGGAGAGCC-3′ (antisense) for GAPDH of human, which were designed from published sequences (GenBank Accesion No. NM 001664, NM 057132, respectively). The thermal cycle profile used was 1) denaturing for 30 s at 95 °C, 2) annealing primers for 30 s at 60 °C. The PCR amplification was performed at 40 cycles. Data are expressed as the relative expression to GAPDH mRNA as a house-keeping gene using the 2−ΔΔCT method [34].

2.5. Western blot analyses

The samples (10 μg of total protein per lane) were subjected to 15% SDS-PAGE, and the proteins were then electrophoretically transferred to a polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane. After blocking with 3% gelatin, the PVDF membrane was incubated with polyclonal rabbit anti-RhoA (1:2500 dilution; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., CA) overnight. Then the membrane was incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG (1:2500 dilution; Amersham Biosciences, Co., NJ), detected by an enhanced chemiluminescent system (Amersham Biosciences) and analyzed by a densitometry system. Detection of house-keeping gene was also performed on the same membrane by using polyclonal monoclonal mouse anti-β-actin (1:5000 dilution; Sigma–Aldrich) samples to confirm the same amount of proteins loaded.

2.6. Construction of human RhoA-luciferase promoter plasmids

For the reporter assay, a human RhoA genomic fragment from nt-1248 to +21 was obtained by PCR amplification using the human genomic DNA isolated from hBSMCs as a template. The forward primer contained a KpnI restriction site and reverse primer contained a BglII restriction site. The PCR primer sets used were as follows: 5′-GACTCCGGGAGCTCAAAATAGC-3′ (sense) and 5′-GCGCACTCACAGATCTTCCACTAT-3′ (antisense), which were designed from published sequences (GenBank Accesion No. NC 000003). The PCR product was digested by KpnI (−1241) and BglII (+8), and inserted into the pGL4.10 vector (Promega, WI). Five 5′-deletion constructs thus obtained (pGL4-1160, -564, -342, -197 and -112) were sequenced to determine the exact sequences. Point mutations of putative STAT6 site and putative NF-κB site within human RhoA promoter were made in the reporter construct, pGL4-1241. The forward primer contained a KpnI restriction site and reverse primer contained a BglII restriction site. The primers used to introduce point mutations are: mSTAT6, 5′-CCGGGAGCTCAAAATAGCAACCAGGTCTTTTATAGCCCCGGAGTTCCCCAGATGCCC-3′ (sense); mNF-κB, 5′-CCGGGAGCTCAAAATAGCAACCAGGTCTTTTATAGCCCGCGTGTTCCCGTGAT-3′ (sense) and 5′-GCGCACTCACAGATCTTCCACTAT-3′ (antisense), which were designed from published sequences (GenBank Accesion No. NC 000003). The PCR product was digested by KpnI and BglII, and inserted into the pGL4.10 vector. The putative STAT6 site and NF-κB site are underlined; boldface indicates the mutation site.

2.7. Luciferase assay

The hBSMCs were seeded in 96-well tissue culture plates, grown to 80% confluence, and transfected with pGL4 reporter plasmids containing various lengths of the human RhoA gene promoter using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen Life Technologies) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were cultured without serum for 24 h before addition of recombinant human IL-13 or recombinant human TNF-α. Luciferase assay was performed using ONE-Glo™ Luciferase assay system (Promega) 72 h after transfection in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. Luciferase activity was measured with a Wallac 1420 ARVOsx multilabel counter (PerkinElmer, MA).

2.8. Statistical analyses

All the data were expressed as the mean with S.E.M. Statistical significance of difference was determined by ANOVA with post hoc Bonferroni/Dunn (StatView for Macintosh ver. 5.0, SAS Institute, Inc., NC). A value of p < 0.05 was considered as significant.

3. Result

3.1. Involvement of STAT6 and NF-κB in the upregulation of RhoA in hBSMCs

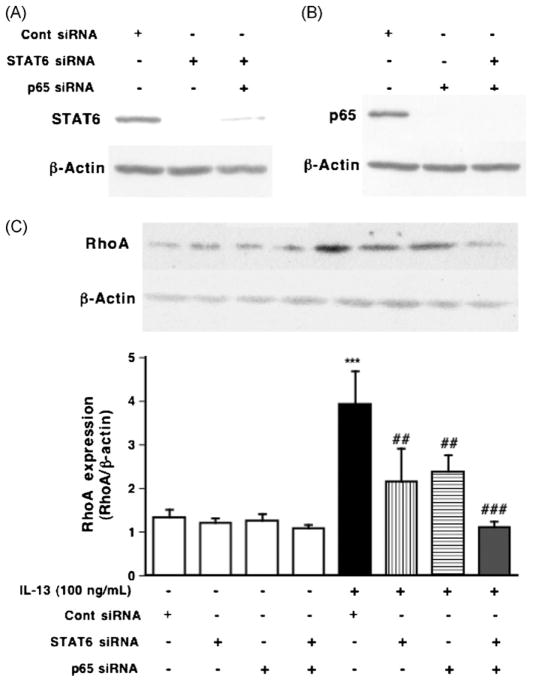

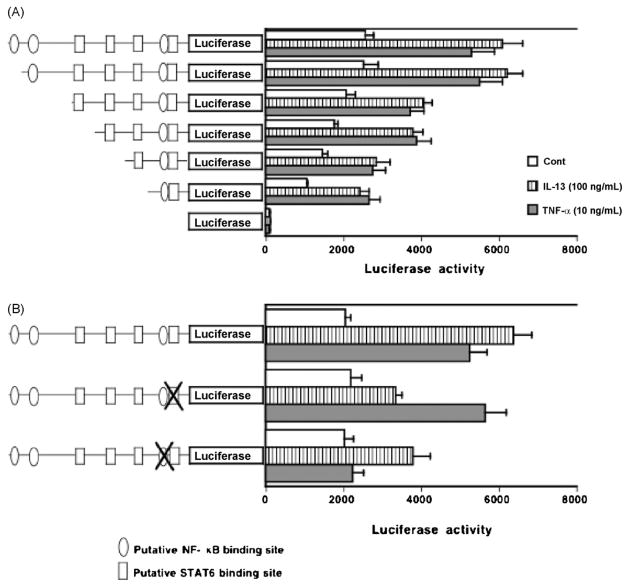

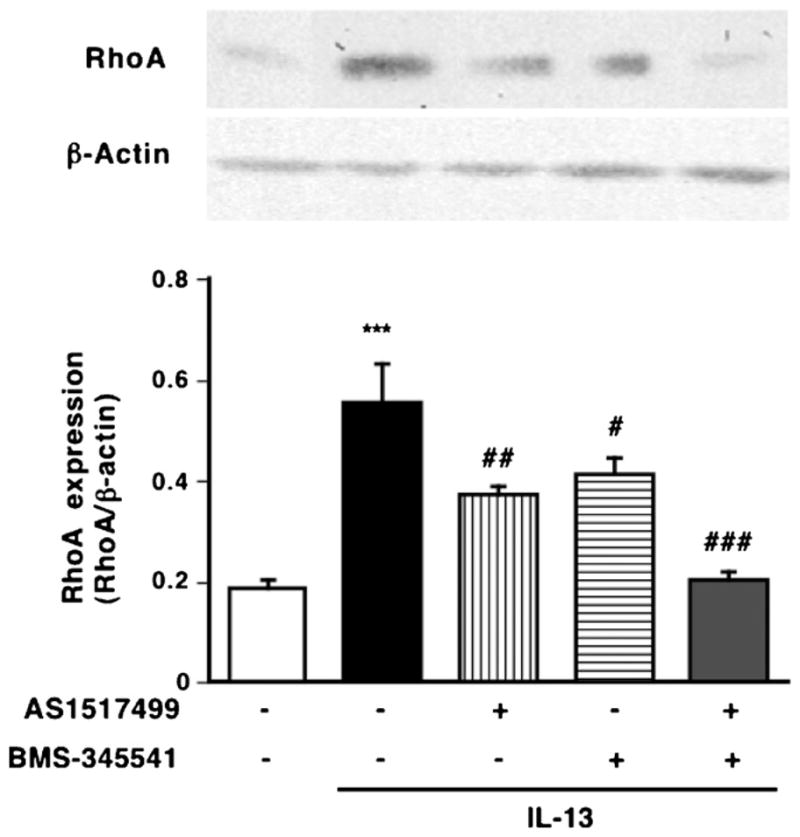

IL-13 binds to cell surface receptor complexes, IL-13 receptor α1 (IL13Rα1) and IL-4 receptor α (IL-4 Rα), leading to the activation of STAT6 that is capable of binding to STAT binding site in the promoters of various IL-13-responsive genes. The phosphorylation of STAT6 was observed when the hBSMCs were treated with IL-13 (100 ng/mL) for 1 h [8]. To determine the role of STAT6 in the IL-13-induced upregulation of RhoA, the cells were also treated with AS1517499, a STAT6 inhibitor [35], in hBSMCs (Fig. 1). The phosphorylation of STAT6 induced by 100 ng/mL of IL-13 for 1 h was significantly inhibited by AS1517499 in a concentration-dependent manner (data not shown). As shown in Fig. 1, the increase in RhoA expression induced by IL-13 was partially inhibited by the treatment with AS1517499. To further confirm the involvement of STAT6, we used RNA interference to knock down the expression of STAT6, and examined the effect of its specific knockdown on IL-13-induced RhoA upregulation in hBSMCs (Fig. 2C). Protein expression was completely lost 3 days after transfection (Fig. 2A). As shown in Fig. 2C, the depletion of STAT6 partially inhibited the IL-13-induced RhoA upregulation.

Fig. 1.

Inhibitory effects of AS1517499, a STAT6 inhibitor, and BMS-345541, an IκB kinase inhibitor, on the upregulation of RhoA induced by IL-13 (100 ng/mL, for 24 h) in hBSMCs. Proteins of hBSMCs were assayed for RhoA by immunoblotting. (Upper photos) Typical blots for RhoA and β-actin. The expression levels of RhoA are summarized in lower panel. Values are the means with S.E.M. from 5 independent experiments. ***p < 0.001 vs. Cont, #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01 and ###p < 0.001 vs. IL-13 alone by two-way ANOVA with post hoc Bonferroni/Dunn’s test.

Fig. 2.

Inhibitory effects of STAT6 siRNA and p65 siRNA on the upregulation of RhoA induced by IL-13 (100 ng/mL, for 24 h) in hBSMCs. (A, B) The effects of siRNAs were assayed by immunoblotting using the indicated antibodies after the transfection with siRNAs as described in Section 2. (C) Proteins of hBSMCs were assayed for RhoA by immunoblotting. (Upper photos) Typical blots for RhoA and β-actin. The expression levels of RhoA are summarized in lower panel. Values are the means with S.E.M. from 3 independent experiments. ***p < 0.001 vs. Cont siRNA, ##p < 0.01 and ###p < 0.001 vs. IL-13 + Cont siRNA by two-way ANOVA with post hoc Bonferroni/Dunn’s test.

We previously reported that IL-13 also activates NF-κB via IKK activation in hBSMCs [36]. Thus, the role of NF-κB in the IL-13-induced RhoA upregulation was examined using BMS345541, an IKK inhibitor, and siRNA against p65. The effect of siRNA was confirmed as shown in Fig. 2B. The increase in RhoA expression induced by IL-13 was partially inhibited by the treatment with BMS345541 (Fig. 1) or transfection with p65 siRNA (Fig. 2C).

In addition, inhibition of both STAT6 and NF-κB completely abolished RhoA upregulation induced by IL-13 in hBSMCs (Figs. 1 and 2C). Therefore, these observations indicate that IL-13 upregulates RhoA via activation of both STAT6 and NF-κB.

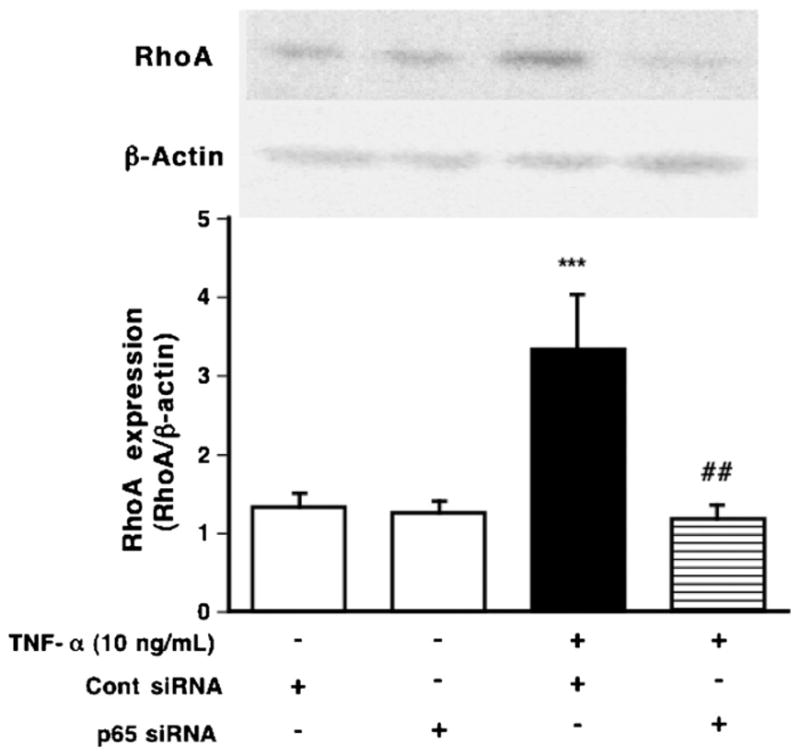

3.2. Involvement of NF-κB in TNF-α-induced RhoA upregulation in hBSMCs

TNF-α binds to cell surface receptor, TNF-α receptor 1 (TNFR1), leading to the activation of NF-κB that is capable of binding to NF-κB binding site in the promoters of various TNF-α-responsive genes. In our previous study, the increase in the nuclear p65 was observed when cells were stimulated with 10 ng/mL of TNF-α for 30 min, and the increase in nuclear p65 induced by TNF-α was significantly inhibited by BMS-345541 in a concentration-dependent manner in hBSMCs [37]. Furthermore, TNF-α-induced increase in RhoA protein was inhibited by BMS-345541 [37]. In the present study, to further determine the role of NF-κB in the TNF-α-induced upregulation of RhoA, we used RNA interference to knock down the expression of NF-κB, and examined the effect of its specific knockdown on TNF-α-induced RhoA upregulation in hBSMCs (Fig. 3). TNF-α had no effect on the phosphorylation of STAT6 in hBSMCs (data not shown).

Fig. 3.

Inhibitory effects of p65 siRNA on the upregulation of RhoA induced by TNF-α (10 ng/mL, for 24 h) in hBSMCs. Proteins of hBSMCs were assayed for RhoA by immunoblotting. (Upper photos) Typical blots for RhoA and β-actin. The expression levels of RhoA are summarized in lower panel. Values are the means with S.E.M. from 3 independent experiments. ***p < 0.001 vs. Cont siRNA, ##p < 0.01 and ###p < 0.001 vs. TNF-α+ Cont siRNA by two-way ANOVA with post hoc Bonferroni/Dunn’s test.

3.3. Identification of IL-13- and TNF-α-responsive elements in human RhoA gene promoter

To examine whether the expression of human RhoA is regulated by the activation of transcription factors, STAT6 and NF-κB, we analyzed the promoter of the human RhoA gene. Reporter constructs containing the sequence from −1241 to +8 were prepared and transfected to hBSMCs. As shown Fig. 4A, luciferase activity was increased after IL-13 or TNF-α stimulation compared with nonstimulation. We then used TFSEARCH, a computer program for searching transcription factor binding sites, to analyze the promoter region of the RhoA gene from nt-1238 to the transcription start site. Four putative STAT6 binding sites, at nt-518 to -510, nt-271 to -263, nt-191 to -183, and nt-78 to -70 and three putative p65 binding sites, at nt-1202 to -1191, nt-1099 to -1090, and nt-84 to -74, were identified as shown in Table 1. To determine which binding site is IL-13- or TNF-α-responsible for RhoA promoter activity, we prepared a series of 5′-deletion mutations of RhoA promoter (Fig. 4A). Deletion of nt-1241 to -112 had minimal effect on IL-13- or TNF-α-responsive luciferase activity despite the lack of two p65 binding sites and three STAT6 binding sites. However, deletion of nt-112 to +8 markedly decreased IL-13- or TNF-α-responsive luciferase activity (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4.

Determination of the IL-13- or TNF-α-responsive region in the human RhoA gene promoter. (A) Human BSMCs were transfected with luciferase reporter plasmids containing various lengths (−1241, −1160, −564, −342, −197 and −112/+ 8 bp) of the human RhoA gene promoter. Putative STAT6 binding site and NF-κB binding site are indicated by the illustration on the left. (B) Mutation analysis. The mutation of proximal STAT6 or NF-kB site abrogates the RhoA promoter activities of pGL4-1241 construct. Luciferase assays were performed in hBSMCs with no stimulation, IL-13 (100 ng/mL) or TNF-α (10 ng/mL) for 24 h. Values are the means with S.E.M. from 6 independent experiments.

Table 1.

Sequence and position of STAT6 and NF-kB binding sites in human RhoA promoter.

| Transcription factor | Position | Sequence |

|---|---|---|

| NF-κB | nt-1202 to -1191 | ATGGACTGTCCA |

| NF-κB | nt-1099 to -1090 | GAGAACTCCC |

| STAT6 | nt-518 to -510 | TTCCCGTAG |

| STAT6 | nt-271 to -263 | TTCCGGGAC |

| STAT6 | nt-191 to -183 | TTCGGGGAG |

| NF-κB | nt-84 to -74 | CCGGAGTTCCC |

| STAT6 | nt-78 to -70 | TTCCCGTGA |

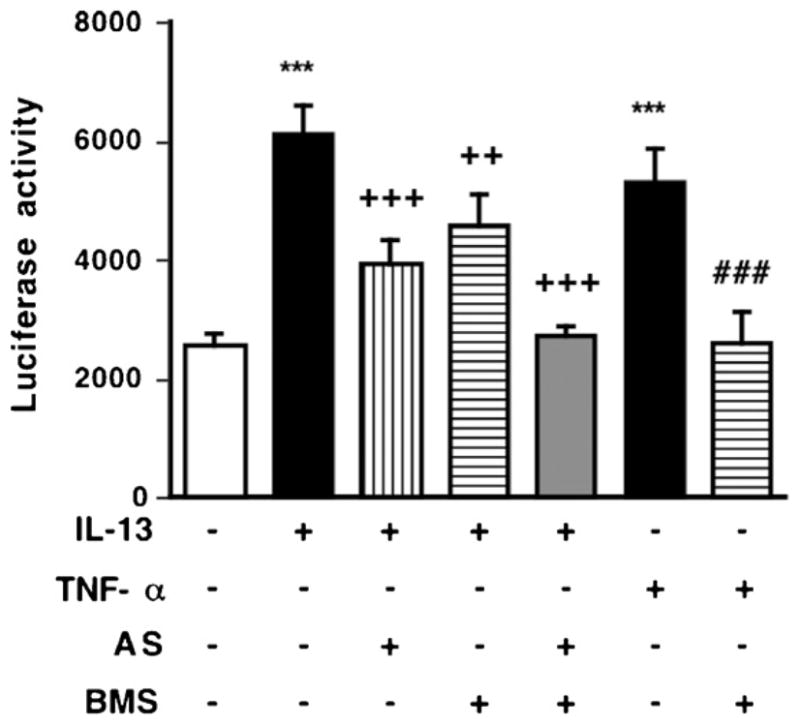

Next, we prepared mutants that had 2- or 3-nt mutations at putative proximal NF-κB site (nt-84 to 74) and putative STAT6 site (nt-78 to 70). The promoter activities were markedly reduced by these mutants (Fig. 4B): the IL-13-induced increase in promoter activity was sensitive both to STAT6 and NF-κB mutants, whereas the TNF-α-induced activity was sensitive only to NF-κB mutants. Similar results were also obtained when the pGL4-1241-tranfected cells were treated with AS1517499 and/or BMS345541 (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Inhibitory effects of AS1517499, a STAT6 inhibitor, and BMS-345541, an IκB kinase inhibitor, on the promoter activity of RhoA induced by IL-13 (100 ng/mL, for 24 h) or TNF-a (10 ng/mL, for 24 h) in hBSMCs. Promoter activity of pGL4-1241 construct were measured by luciferase assay. Values are the means with S.E.M. from 5 independent experiments. ***p < 0.001 vs. Cont, ++p < 0.01, +++p < 0.001 vs. IL-13 alone, and ###p < 0.001 vs. TNF-α alone by two-way ANOVA with post hoc Bonferroni/Dunn’s test.

4. Discussion

Airway smooth muscle is an important effector tissue regulating bronchomotor tone. It has been suggested that modulation of airway smooth muscle by inflammatory mediators such as cytokines may play an important role in the development of airway hyperresponsiveness [38], one of the characteristic features of patients with allergic bronchial asthma. In our animal model of allergic bronchial asthma, an increased contractility of isolated bronchial smooth muscle to contractile agonists has also been found [39,40]. The augmented bronchial smooth muscle contraction induced by antigen challenge has reportedly been associated with an upregulation of RhoA, a small GTPase that is involved in the agonist-induced Ca2+ sensitization of smooth muscle contraction [6,41]. An importance of RhoA and its downstream Rho-kinases was also demonstrated in contraction of human bronchial smooth muscle [42], and the RhoA/Rho-kinase pathway has now been proposed as a new target for the treatment of AHR in asthma [43]. Therefore, understanding the regulation of RhoA upregulation is even more crucial under clinical consideration.

The current study revealed that an upregulation of RhoA was observed by IL-13 via activation of both STAT6 and NF-κB (Figs. 1 and 2). An upregulation of RhoA was also observed by TNF-α via activation of NF-κB in hBSMCs (Fig. 3). The most proximal STAT6 binding site and NF-κB binding site were indispensable to the induction of RhoA transcription by stimulation of IL-13 and TNF-α (Fig. 4). The increased luciferase activity by IL-13 or TNF-α was inhibited by STAT6 inhibitor and/or NF-κB inhibitor (Fig. 5). These observations indicate that the association of STAT6 and NF-κB with the proximal STAT6 site and NF-κB site in the RhoA promoter is required for induction of upregulation of RhoA by IL-13 and TNF-α.

The upstream genomic DNA sequence of human RhoA contains several STAT6 binding sites—nt-518 (from the transcription start site) to -510, nt-271 to -263, nt-191 to -183, and nt-78 to -70 and p65 binding sites—nt-1202 to -1191, nt-1099 to -1090, and nt-84 to -74 (Table 1)—when analyzed using the TFSEARCH program (http://mbs.cbrc.jp/research/db/TFSEARCH.html). Our data of luciferase assay indicate for the first time that the proximal STAT6 binding site located at nt-78 to -70 and NF-κB binding site located at nt-84 to -74 are responsible for the transcription of RhoA gene by the stimulation of IL-13 or TNF-α (Fig. 4). Matsukura et al. and Hoeck et al. demonstrated that a similar overlapping sequence regulated expression of eotaxin-1 by stimulation of IL-4 and TNF-α [44,45]. Sauzeau et al. [46] reported that RhoA expression is augmented by NO through activation of cGMP/CRE in rat vascular smooth muscle cells. Therefore, it would be interesting to clarify the mechanism by which different stimuli induce different pathway of signal transduction and distinct sets of transcription factors to induce the expression of RhoA gene.

As well as our previous findings that both the STAT6 phosphorylation and RhoA upregulation induced by IL-13 were inhibited by leflunomide, tyrosine kinase inhibitor (250 μM) [8], the treatment of hBSMCs with a STAT6 siRNA (Fig. 2C) or a STAT6 inhibitor AS1517499 (Fig. 1) partly inhibited the upregulation of RhoA induced by IL-13. Treatment with a STAT6 inhibitor AS1517499 partly inhibited the promoter activity of RhoA induced by IL-13 (Fig. 5). Because IL-13 activated not only STAT6 but also NF-κB in hBSMCs [36], we currently examined the role of NF-κB in RhoA upregulation induced by IL-13. Treatment of hBSMCs with a p65 siRNA (Fig. 2C) or an IKK inhibitor (Fig. 1) partly inhibited the IL-13-induced RhoA upregulation. Treatment with an IKK inhibitor partly inhibited the promoter activity of RhoA induced by IL-13 (Fig. 5). In addition, depletion of both STAT6 and NF-κB using siRNAs (Fig. 2C) or inhibitors abolished RhoA upregulation induced by IL-13. These findings indicate that the activation of STAT6 and NF-κB in hBSMCs are involved in the IL-13-induced transcription of RhoA.

Our previous findings that both the NF-κB translocation to nuclei and RhoA upregulation induced by TNF-α were inhibited by BMS-345541, an IKK inhibitor, concentration-dependently [37]. In the present study, the treatment of hBSMCs with a p65 siRNA completely inhibited RhoA upregulation induced by TNF-α (Fig. 3). The treatment of hBSMCs with a BMS345541 completely inhibited RhoA promoter activity induced by TNF-α (Fig. 5). These results indicate that the activation of NF-κB in hBSMCs is involved in the TNF-α-induced RhoA transcription. However, a STAT6 siRNA or a p65 siRNA had no effect on RhoA expression in nonstimulated hBSMCs (Figs. 2C and 3). These findings indicate that STAT6 and NF-κB is involved in upregulation of RhoA induced by IL-13 or TNF-α, but not involved in basal expression of RhoA in hBSMCs.

In conclusion, the current study clearly demonstrated the importance of STAT6 and NF-κB activation in the RhoA transcription induced by IL-13 or TNF-α. Therefore, we suggest that activated STAT6 and NF-κB by augmentation of IL-13 and TNF-α bind respective proximal binding sites in RhoA promoter region to induce RhoA upregulation in bronchial smooth muscle in allergic asthma.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Taiki Kobayashi and Makiko Momata for their technical assistance. This work was partly supported by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan.

Abbreviations

- BSM

bronchial smooth muscle

- IL

interleukin

- TNF

tumor necrosis factor

- STAT

signal transducer and activator of transcription

- NF-κB

nuclear factor κB

- AHR

airway hyperresponsiveness

- hBSMCs

human bronchial smooth muscle cells

- IKK

IκB kinase

- siRNA

small interfering RNA

- hFGF-b

human fibroblast growth factor-basic

- hEGF

human epidermal growth factor

- PVDF

polyvinylidene fluoride

- Tyk

tyrosine kinase

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

References

- 1.Chiba Y, Misawa M. Alteration in Ca2+ availability involved in antigen-induced airway hyperresponsiveness in rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 1995;278:79–82. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(95)00132-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Satoh S, Kreutz R, Wilm C, Ganten D, Pfitzer G. Augmented agonist-induced Ca2+-sensitization of coronary artery contraction in genetically hypertensive rats. Evidence for altered signal transduction in the coronary smooth muscle cells. J Clin Invest. 1994;944:1397–403. doi: 10.1172/JCI117475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fujita A, Takeuchi T, Nakajima H, Nishio H, Hata F. Involvement of heterotrimeric GTP-binding protein and Rho protein, but not protein kinase C, in agonist-induced Ca2+ sensitization of skinned muscle of guinea pig vas deferens. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1995;274:555–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bremerich DH, Warner DO, Lorenz RR, Shumway R, Jones KA. Role of protein kinase C in calcium sensitization during muscarinic stimulation in airway smooth muscle. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:L775–781. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1997.273.4.L775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chiba Y, Takeyama H, Sakai H, Misawa M. Effects of Y-27632 on acetylcholine-induced contraction of intact and permeabilized intrapulmonary bronchial smooth muscles in rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 2001;427:77–82. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(01)01225-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Somlyo AP, Somlyo AV. Ca2+ sensitivity of smooth muscle and nonmuscle myosin II: modulated by G proteins, kinases, and myosin phosphatase. Physiol Rev. 2003;83:1325–58. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00023.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chiba Y, Sakai H, Wachi H, Sugitani H, Seyama Y, Misawa M. Upregulation of RhoA mRNA in bronchial smooth muscle of antigen-induced airway hyperresponsive rats. J Smooth Muscle Res. 2003;39:221–8. doi: 10.1540/jsmr.39.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chiba Y, Nakazawa S, Todoroki M, Shinozaki K, Sakai H, Misawa M. Interleukin-13 augments bronchial smooth muscle contractility with an up-regulation of RhoA protein. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2009;40:159–67. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2008-0162OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mukai Y, Shimokawa H, Matoba T, Kandabashi T, Satoh S, Hiroki J, et al. Involvement of Rho-kinase in hypertensive vascular disease: a novel therapeutic target in hypertension. FASEB J. 2001;15:1062–4. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0735fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seko T, Ito M, Kureishi Y, Okamoto R, Moriki N, Onishi K, et al. Activation of RhoA and inhibition of myosin phosphatase as important components in hypertension in vascular smooth muscle. Circ Res. 2003;92:411–8. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000059987.90200.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Uehata M, Ishizaki T, Satoh H, Ono T, Kawahara T, Morishita T, et al. Calcium sensitization of smooth muscle mediated by a Rho-associated protein kinase in hypertension. Nature. 1997;389:990–4. doi: 10.1038/40187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shimokawa H, Seto M, Katsumata N, Amano M, Kozai T, Yamawaki T, et al. Rho-kinase-mediated pathway induces enhanced myosin light chain phosphorylations in a swine model of coronary artery spasm. Cardiovasc Res. 1999;43:1029–39. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(99)00144-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kandabashi T, Shimokawa H, Miyata K, Kunihiro I, Kawano Y, Fukata Y, et al. Inhibition of myosin phosphatase by upregulated Rho-kinase plays a key role for coronary artery spasm in a porcine model with interleukin-1beta. Circulation. 2000;101:1319–23. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.11.1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chrissobolis S, Sobey CG. Evidence that Rho-kinase activity contributes to cerebral vascular tone in vivo and is enhanced during chronic hypertension: comparison with protein kinase C. Circ Res. 2001;88:774–9. doi: 10.1161/hh0801.090441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sato M, Tani E, Fujikawa H, Kaibuchi K. Involvement of Rho-kinase-mediated phosphorylation of myosin light chain in enhancement of cerebral vasospasm. Circ Res. 2000;87:195–200. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.3.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wills-Karp M. Interleukin-13 in asthma pathogenesis. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2004;4:123–31. doi: 10.1007/s11882-004-0057-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berry MA, Parker D, Neale N, Woodman L, Morgan A, Monk P, et al. Sputum and bronchial submucosal IL-13 expression in asthma and eosinophilic bronchitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;114:1106–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Noah TL, Tudor GE, Ivins SS, Murphy PC, Peden DB, Henderson FW. Repeated measurement of nasal lavage fluid chemokines in school-age children with asthma. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2006;96:304–10. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)61240-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prieto J, Lensmar C, Roquet A, van der Ploeg I, Gigliotti D, Eklund A, et al. Increased interleukin-13 mRNA expression in bronchoalveolar lavage cells of atopic patients with mild asthma after repeated low-dose allergen provocations. Respir Med. 2000;94:806–14. doi: 10.1053/rmed.2000.0826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Batra V, Musani AI, Hastie AT, Khurana S, Carpenter KA, Zangrilli JG, et al. Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid concentrations of transforming growth factor (TGF)-beta1, TGF-beta2, interleukin (IL)-4 and IL-13 after segmental allergen challenge and their effects on alpha-smooth muscle actin and collagen III synthesis by primary human lung fibroblasts. Clin Exp Allergy. 2004;34:437–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2004.01885.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grunstein MM, Hakonarson H, Leiter J, Chen M, Whelan R, Grunstein JS, et al. IL-13-dependent autocrine signaling mediates altered responsiveness of IgE-sensitized airway smooth muscle. Am J Physiol. 2002;282:L520–528. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00343.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhu Z, Homer RJ, Wang Z, Chen Q, Geba GP, Wang J, et al. Pulmonary expression of interleukin-13 causes inflammation, mucus hypersecretion, subepithelial fibrosis, physiologic abnormalities, and eotaxin production. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:779–88. doi: 10.1172/JCI5909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuperman DA, Huang X, Koth LL, Chang GH, Dolganov GM, Zhu Z, et al. Direct effects of interleukin-13 on epithelial cells cause airway hyperreactivity and mucus overproduction in asthma. Nat Med. 2002;8:885–9. doi: 10.1038/nm734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Laporte JC, Moore PE, Baraldo S, Jouvin MH, Church TL, Schwartzman IN, et al. Direct effects of interleukin-13 on signaling pathways for physiological responses in cultured human airway smooth muscle cells. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:141–8. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.1.2008060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shah A, Church MK, Holgate ST. Tumour necrosis factor alpha: a potential mediator of asthma. Clin Exp Allergy. 1995;25:1038–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.1995.tb03249.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Broide DH, Lotz M, Cuomo AJ, Coburn DA, Federman EC, Wasserman SI. Cytokines in symptomatic asthma airways. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1992;89:958–67. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(92)90218-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Taki F, Kondoh Y, Matsumoto K, Takagi K, Satake T, Taniguchi H, et al. Tumor necrosis factor in sputa of patients with bronchial asthma on exacerbation. Arerugi. 1991;40:643–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Watson ML, Smith D, Bourne AD, Thompson RC, Westwick J. Cytokines contribute to airway dysfunction in antigen-challenged guinea pigs: inhibition of airway hyperreactivity, pulmonary eosinophil accumulation, and tumor necrosis factor generation by pretreatment with an interleukin-1 receptor antagonist. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1993;8:365–9. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb/8.4.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lukacs NW, Strieter RM, Chensue SW, Widmer M, Kunkel SL. TNF-alpha mediates recruitment of neutrophils and eosinophils during airway inflammation. J Immunol. 1995;154:5411–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Amrani Y, Chen H, Panettieri RA., Jr Activation of tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 in airway smooth muscle: a potential pathway that modulates bronchial hyper-responsiveness in asthma? Respir Res. 2000;1:49–53. doi: 10.1186/rr12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sakai H, Otogoto S, Chiba Y, Abe K, Misawa M. Involvement of p42/44 MAPK and RhoA protein in augmentation of ACh-induced bronchial smooth muscle contraction by TNF-alpha in rats. J Appl Physiol. 2004;97:2154–9. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00752.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pennings HJ, Kramer K, Bast A, Buurman WA, Wouters EF. Tumour necrosis factor-alpha induces hyperreactivity in tracheal smooth muscle of the guineapig in vitro. Eur Respir J. 1998;12:45–9. doi: 10.1183/09031936.98.12010045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Choi IW, Sun K, Kim YS, Ko HM, Im SY, Kim JH, et al. TNF-alpha induces the late-phase airway hyperresponsiveness and airway inflammation through cytosolic phospholipase A2 activation. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;116:537–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chiba Y, Tanabe M, Goto K, Sakai H, Misawa M. Downregulation of miR-133a contributes to upregulation of RhoA in bronchial smooth muscle cells. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180:713–9. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200903-0325OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nagashima S, Yokota M, Nakai E, Kuromitsu S, Ohga K, Takeuchi M, et al. Synthesis and evaluation of 2-{[2-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-ethyl]amino} pyrimidine-5-carboxamide derivatives as novel STAT6 inhibitors. Bioorg Med Chem. 2007;15:1044–55. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2006.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goto K, Chiba Y, Misawa M. IL-13 induces translocation of NF-kappaB in cultured human bronchial smooth muscle cells. Cytokine. 2009;46:96–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2008.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Goto K, Chiba Y, Sakai H, Misawa M. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha) induces upregulation of RhoA via NF-kappaB activation in cultured human bronchial smooth muscle cells. J Pharmacol Sci. 2009;110:437–44. doi: 10.1254/jphs.09081fp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Amrani Y, Panettieri RA., Jr Modulation of calcium homeostasis as a mechanism for altering smooth muscle responsiveness in asthma. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;2:39–45. doi: 10.1097/00130832-200202000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chiba Y, Ueno A, Sakai H, Misawa M. Hyperresponsiveness of bronchial but not tracheal smooth muscle in a murine model of allergic bronchial asthma. Inflamm Res. 2004;53:636–42. doi: 10.1007/s00011-004-1305-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chiba Y, Takada Y, Miyamoto S, MitsuiSaito M, Karaki H, Misawa M. Augmented acetylcholine-induced. Rho-mediated Ca2+ sensitization of bronchial smooth muscle contraction in antigen-induced airway hyperresponsive rats. Br J Pharmacol. 1999;127:597–600. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chiba Y, Misawa M. The role of RhoA-mediated Ca2+ sensitization of bronchial smooth muscle contraction in airway hyperresponsiveness. J Smooth Muscle Res. 2004;40:155–67. doi: 10.1540/jsmr.40.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yoshii A, Iizuka K, Dobashi K, Horie T, Harada T, Nakazawa T, et al. Relaxation of contracted rabbit tracheal and human bronchial smooth muscle by Y-27632 through inhibition of Ca2+ sensitization. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1999;20:1190–200. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.20.6.3441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gosens R, Schaafsma D, Nelemans SA, Halayko AJ. Rho-kinase as a drug target for the treatment of airway hyperrespon-siveness in asthma. Mini Rev Med Chem. 2006;6:339–48. doi: 10.2174/138955706776073402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hoeck J, Woisetschlager M. STAT6 mediates eotaxin-1 expression in IL-4 or TNF-alpha-induced fibroblasts. J Immunol. 2001;166:4507–15. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.7.4507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Matsukura S, Stellato C, Georas SN, Casolaro V, Plitt JR, Miura K, et al. Interleukin-13 upregulates eotaxin expression in airway epithelial cells by a STAT6-dependent mechanism. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2001;24:755–61. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.24.6.4351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sauzeau V, Rolli-Derkinderen M, Marionneau C, Loirand G, Pacaud P. Rhoa expression is controlled by nitric oxide through cGMP-dependent protein kinase activation. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:9472–80. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212776200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]