Abstract

Background

The association between methamphetamine use and HIV seroconversion for men who have sex with men (MSM) was examined using longitudinal data from the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study.

Methods

Seronegative (n=4003) men enrolled in 1984–85, 1987–1991 and 2001–2003 were identified. Recent methamphetamine and popper use were determined at either the current or the previous visit. Time to HIV-seroconversion was the outcome of interest. Covariates included race/ethnicity, cohort, study site, educational level, number of sexual partners, number of unprotected insertive anal sexual partners (UIAS), number of unprotected receptive anal sexual partners (URAS), insertive rimming, cocaine use at either the current or last visit, ecstasy use at either the current or last visit, any needle use since last visit, CES-D depression score > 16 since last visit, and alcohol consumption.

Results

After adjusting for covariates, there was an approximately 1.46-fold independent increased relative hazard (HR) of HIV seroconversion for methamphetamine use. The HR associated with popper use was 2.1 [95% CI 1.63, 2.70]. The HR of HIV seroconversion increased with URAS ranging from 1.87 [95% CI 1.40, 2.51] for 1 partner to 9.32 [95% CI 6.20, 13.98] for 5+ partners. The joint HR for methamphetamine and popper use was 3.05 [95% CI 2.12, 4.37]. Most notably, there was a significant joint HR for methamphetamine use and URAS of 2.71 [95% CI 1.81, 4.04] for men with 1 unprotected receptive anal sex partner, which increased in a dose-dependent manner for >1 partners.

Conclusions

Further examination of the synergism of patterns of drug use and sexual risk behaviors on rates of HIV seroconversion will be necessary in order to develop new HIV prevention strategies for drug-using MSM.

Keywords: Multicenter AIDS cohort study, methamphetamine, HIV seroconversion, MSM

INTRODUCTION

The use of methamphetamine, a powerful central nervous system stimulant associated with sexual enhancement has been popular among men who have sex with men (MSM) for many years. 1–3 Behavioral research has demonstrated that gay male methamphetamine users are more likely to engage in high risk sexual practices for the transmission of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections, and to be HIV seropositive. 4–18

Even though a substantial literature exists to demonstrate the cross-sectional association between methamphetamine use and risk for HIV transmission among MSM, only a few studies have examined the relationship between methamphetamine use and HIV seroincidence. Chesney, et al. 19 demonstrated a 1.02 and 2.89 relative risk of HIV seroconversion for current methamphetamine vs. non-users and chronic methamphetamine users vs. non-users, respectively, after adjusting for unprotected anal intercourse in 337 seronegative gay men followed for 3 years from the San Francisco Men’s Health Study. Most recently, Buchacz, et al. 20 examined the association of methamphetamine use and HIV seroincidence in 2991 MSM who were tested anonymously for HIV in San Francisco. Thirty-four out of 290 methamphetamine users (within the past year) had recently seroconverted, yielding a relative risk of HIV seroconversion associated with methamphetamine use of 2.5 [95% CI 0.9–6.9], adjusted for age, race, ethnicity, use of other non-injected drugs in the past year (including poppers), marijuana use, and alcohol use. Although important, these studies have been limited by small number of seroconversions and self-reported data collected over a short follow-up period, inadequate adjustment for confounding factors, and/or limited geographic diversity, and so only provide a limited measure of the methamphetamine-HIV seroconversion relationship.

A better understanding of the drug use-HIV seroincidence relationship in general and the methamphetamine-HIV seroincidence relationship in particular among vulnerable populations is needed. An examination of this relationship across multiple sites and over longer periods of time, taking into account important risk factors would provide an important extension of the finding that methamphetamine use is associated with new HIV infections among MSM. Since methamphetamine use can highly disengage sexual pleasure from cognition 21 and with its recent spread of use among MSM across geographically diverse areas, it has been shown to be associated with intentionally practice unprotected anal sex (“barebacking”) 22–25

Our examination of popper use, in addition to methamphetamine use, in this study was the result of previous findings demonstrating popper use was one of the most consistently and strongly associated drug use behaviors in HIV seroconversion among MACS participants. 26 Additionally, popper use has been shown to be frequently used along with methamphetamine to “enhance sexual pleasure, get a better high, or take the edge off of methamphetamine”. 27

In this study we examined the association of methamphetamine and other stimulant use along with risky sexual behavior on HIV seroconversion using data from MSM who were initially HIV seronegative and followed over time in the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study.

METHODS

Population and Study Design

The Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study (MACS) is an ongoing, prospective study of the natural history of HIV infection among MSM in the United States. A total of 6973 men were recruited: 4954 in 1984–1985, 668 in 1987–1991, and 1351 in 2001–2003 at four centers located in Baltimore, MD/Washington DC; Chicago, IL; Los Angeles, CA; and Pittsburgh, PA. The study design has been described previously 28, 29 and only methods relevant to the present study are presented here. The study questionnaires are available at http://www.statepi.jhsph.edu/macs/forms.html. The MACS study protocols were approved by institutional review boards of each of the participating centers, and their community affiliates, and informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Participants returned every 6 months for a detailed interview, a physical examination, and collection of blood for concomitant laboratory testing and storage. The interview included questions about medical conditions, medical treatments, sexual behavior, and recreational drugs (e.g., marijuana, poppers, cocaine, crack, heroin, methamphetamine, ecstasy) as well as alcohol consumption. All questions concerning sexual and drug use behaviors were assessed using audio computer-assisted self interviewing (ACASI) during Phase II of the study, a methodology shown to yield more accurate assessments of “sensitive behaviors” than interviewer-administered questionnaires. 30 ELISAs with confirmatory Western blot tests were performed on all participants initially and at every semi-annual visit thereafter for initially seronegative men to determine HIV seroincidence.

A prospective cohort design was used to examine the effects of recreational drugs, particularly methamphetamine and poppers, on the risk of HIV-seroconversion among initially HIV-negative participants. The cohort included all participants who were HIV-negative at baseline and had data of methamphetamine use at baseline or follow-up visits (n=4003). Since methamphetamine use data were not collected at visits 16–25 (April 1992–April 1996) these visits were excluded. Specifically, the analysis used MACS data at visits 1–15 (April 1984–September 1991) and 26–41 (October 1996–September 2004).

Outcome variable

Time to HIV-seroconversion was the outcome of interest. The date of seroconversion was defined as the midpoint between the dates of the last HIV negative visit and the first HIV seropositive visit. Participants who did not seroconvert during one or both observation periods also contributed time to the analysis. In visits 1–15, the person-time contributed to the analysis was the time from study entry to the date of seroconversion for those who seroconverted prior to September 1991 (end of visit 15), or to the earlier date of the last visit seen or visit 15 (if no seroconversion). Participants who were HIV-negative as of October 1, 1996 (visit 26) contributed time to the analysis of visits 26–41. Specifically, in the second phase such participants were treated as late entries; entry time was the date of visit 26 for those enrolled prior to 1996 and the date of baseline visit for 2001–2003 cohort, and exit time was the date of seroconversion if subsequent to 1996, or the earlier of the last visit seen or visit 41 (if no seroconversion).

Exposure variables

The primary exposure of interest was the use of methamphetamine (yes/no), which was defined as ‘yes’ if a participant reported using it at either the current visit or the previous visit. The questions eliciting information about use of methamphetamines differed in the two phases. In the early phase, we used affirmative to the question of uses of “amphetamines, speed, crystal or other uppers“ whereas in the second phase, use of crystal methamphetamine (along with speed) was a unique drug category in the questionnaire.

Demographics and other behaviors were included to adjust for possible confounding. Age at the time of enrollment was calculated using self-reported date of birth and treated as a continuous covariate centered at the approximate median of 33.4 years. Race was self-reported at baseline and categorized as White non-Hispanic, White Hispanic, Black non-Hispanic, Black Hispanic, and Other. Self-reported highest level of education completed at baseline was categorized as 12th grade or less, college and post-college graduate. Individuals enrolled between 2001–2003 were compared to those who were enrolled between 1984–1985 and 1987–1991.

Using the interview data collected at each visit, the number of sexual partners since the prior visit was categorized as none, one, 2–4, and 5 or more. The number of anal sexual partners with whom the participants reported always using a condom was subtracted from the total number of partners for each respective activity (receptive or insertive) to obtain the number of partners with whom the participant engaged in unprotected anal sex and were also categorized as none, one, 2–4, and 5 or more. Any insertive oral/anal (rimming) sex reported at the visit was treated as a dichotomous variable. Current or previous visit use of poppers, cocaine or ecstasy and any needle use also were dichotomized. Type of alcohol use was classified using frequency of drinking and average number of drinks the participant drank per day since the last visit. Binge drinking was defined as 5 or more drinks per occasion occurring at least monthly. Moderate to heavy drinking was at least weekly drinking of 3–4 drinks or drinking 5 or more drinks less than monthly. The remaining participants who had low to moderate or no drinking comprised the third group of alcohol use in this analysis. Likelihood of clinical depression was indicated by a score of 16 or higher using the Center for Epidemiologic Study of Depression symptom checklist. 31 Except for age, race, education, cohort membership, and study center, other factors were all time-varying, i.e., they were updated at each visit.

Statistical Analyses

Associations between the risk factors and the time-to-seroconversion were estimated using the Cox proportional hazards regression model with time dependent covariates. 32 Since the model for the proportionality factor is log linear, effects on the relative hazard are multiplicative. An important feature of this model is that it can accommodate late entries (technically, left truncated observations - subjects for whom data are available only if they survive to a known observation point). 33 In our analysis subjects having data during the second phase (visits 26–41) were treated as late entries at their first available visit during this period. This prevented bias caused by events, in particular use of methamphetamine, occurring during the period between the two phases when no data was collected. Time dependent covariates are treated in a similar fashion; available subjects are included in the risk set at each time point of observation according to their covariate status (for example, use of a given drug or not), which can change during different intervals of time. Predicted survival curves were calculated by using a nonparametric estimate of the baseline survival function (corresponding to the reference categories for all covariates), and applying the parametric proportionality factors for the hazard estimated by the model using particular choices for the values of the covariates.

Data collected at the time of study enrollment were used to characterize the men who remained persistently seronegative and those who seroconverted during the follow-up. The remaining variables were computed using questions asked at each visit. Each exposure variable was first evaluated in a univariate proportional hazards model. The multivariate approach used methamphetamine and popper use with all other covariates to test the most recent antecedent exposure to the outcome event. Interactions terms such as recent methamphetamine use * popper use, recent methamphetamine use * number of unprotected receptive anal sex partners, and popper use * number of unprotected receptive anal sex partners were also tested.

RESULTS

The baseline characteristics of the cohort are presented in Table 1. Men who seroconverted were similar to seronegative men in terms of age at baseline, race/ethnicity, and educational level. The proportions of seroconverters (22–28%) and seronegative men (23–28%) were similar across study centers. However, seroconverters were more likely to have enrolled in the first phase of the cohort, to ever have used methamphetamine, poppers, cocaine, or ecstasy during any of the cohort visits and to have practiced both unprotected insertive and receptive anal sex prior to enrollment. The prevalences of having ever used poppers, cocaine, ecstasy or needle use during any of the cohort visits among the seroconverters who recently used methamphetamine was 93%, 51%, 38%, and 16%, respectively, and was consistent throughout the study periods. Additionally, 98% and 94% of these seroconverters reported having had either unprotected insertive or receptive anal sex at least once [data not shown].

TABLE 1.

Enrollment characteristics of MACS HIV seroconverters (SC) and HIV seronegatives (SN) studied

| Seroconverters | Seronegatives | Overall | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 436 | 3567 | 4003 |

| Age (yrs), mean (SD) | 32.0 (7.6) | 34.6 (8.6) | 34.4 (8.6) |

| Age at seroconversion (yrs), mean (SD) | 34.7 (8.4) | ||

| Age categories at enrollment | |||

| 18–25 | 96 (22%) | 576 (16%) | 672 (17%) |

| 26–35 | 223 (51%) | 1572 (44%) | 1795 (45%) |

| 36–45 | 96 (22%) | 1052 (30%) | 1148 (28%) |

| 46–55 | 20 (5%) | 303(8%) | 323 (8%) |

| 56+ | 1 (0.2%) | 64 (2%) | 65 (2%) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White, non-Hispanic | 377 (86%) | 2742 (77%) | 3119 (78%) |

| White, Hispanic | 22 (5%) | 147 (4%) | 169 (4%) |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 34 (8%) | 548 (15%) | 582 (15%) |

| Black, Hispanic | 0 (0%) | 21 (1%) | 21 (1%) |

| All Other | 3 (1%) | 106 (3%) | 109 (3%) |

| Educational level | |||

| 12th grade or less | 47 (11%) | 584 (16%) | 631 (16%) |

| Some college or college graduate | 252 (59%) | 1720 (49%) | 1972 (50%) |

| Some graduate work or graduate degree | 131 (30%) | 1218 (35%) | 1349(34%) |

| Cohort enrollment | |||

| 1984–1985 and 1987–1991 (early) | 431 (99%) | 2926 (82%) | 3357 (84%) |

| 2001–2003 (late) | 5 (1%) | 641 (18%) | 646 (16%) |

| Center | |||

| Baltimore | 104 (24%) | 986 (28%) | 1090 (27%) |

| Chicago | 98 (22%) | 769 (22%) | 867 (22%) |

| Pittsburgh | 105 (24%) | 972 (27%) | 1077 (27%) |

| Los Angeles | 129 (30%) | 840 (23%) | 969 (24%) |

| Ever used methamphetamine | |||

| Yes | 173 (40%) | 753 (21%) | 926 (23%) |

| Ever used poppers | |||

| Yes | 356 (82%) | 2068 (58%) | 2424 (61%) |

| Ever used cocaine | |||

| Yes | 135 (31%) | 418 (12%) | 553 (14%) |

| Ever used Ecstasy | |||

| Yes | 86 (20%) | 384 (11%) | 470 (12%) |

| Ever had unprotected insertive anal sex | |||

| Yes | 407 (93%) | 2728 (76%) | 3135 (78%) |

| Ever had unprotected receptive anal sex | |||

| Yes | 410 (94%) | 2478 (69%) | 2888 (72%) |

Table 2 presents univariate and multivariate predictors of HIV seroconversion. As expected in this cohort of MSMs, number of unprotected anal receptive sex partners was the primary risk factor demonstrated by an increasing ‘dose-response’ relationship with HIV seroconversion. Protective univariate predictors of HIV seroconversion were older age at baseline and late vs. early cohort, whereas number of sexual partners, number of unprotected insertive anal sex partners, insertive rimming, methamphetamine use, the use of cocaine, ecstasy or poppers, any needle use, and alcohol use were positive risk factors for HIV seroconversion.

TABLE 2.

Univariate and multivariate hazard ratios associated with HIV seroconversion using Cox proportional hazard models with time dependent covariates – Combined MACS Cohort Enrollment1

| Univariate Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | Multivariate Hazard Ratio (95% CI)2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Age at enrollment | 0.96 (0.95, 0.97) | 0.99 (0.98,1.00) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| White, non-Hispanic | 1 | 1 |

| White, Hispanic | 1.34 (0.87, 2.06) | 1.12 (0.70,1.80) |

| Black, (includes non-Hispanic and Hispanic) | 1.02 (0.72, 1.45) | 2.10 (1.45, 3.03) |

| All Other | 0.43 (0.14, 1.33) | 0.59 (0.15, 2.40) |

| Educational level | ||

| 12th grade or less | 1 | 1 |

| Some college or college graduate | 1.20 (0.88, 1.64) | 1.17 (0.84, 1.64) |

| Some graduate work or graduate degree | 0.81 (0.58, 1.13) | 0.93 (0.64, 1.33) |

| Cohort enrollment | ||

| 1984–1985 and 1987–1991 (early) | 1 | 1 |

| 2001–2003 (late) | 0.19 (0.08, 0.46) | 0.31 (0.13, 0.77) |

| Sexual partners | ||

| None | 1 | 1 |

| 1 partner | 2.63 (1.33, 5.17) | 1.63 (0.78, 3.39) |

| 2–4 partners | 6.65 (3.50, 12.64) | 2.87 (1.43, 5.76) |

| 5+ partners | 9.29 (4.93, 17.50) | 2.50 (1.24, 5.04) |

| Unprotected insertive anal sex partners | ||

| None | 1 | 1 |

| 1 partner | 1.83 (1.44, 2.32) | 1.11 (0.84, 1.46) |

| 2–4 partners | 3.83 (2.96, 4.96) | 1.16 (0.84, 1.59) |

| 5+ partners | 5.40 (3.94, 7.39) | 0.95 (0.63, 1.43) |

| Unprotected receptive anal sex partners | ||

| None | 1 | 1 |

| 1 partner | 2.17 (1.69, 2.78) | 1.87 (1.40, 2.51) |

| 2–4 partners | 8.73 (6.78, 11.24) | 5.37 (3.94, 7.32) |

| 5+ partners | 15.32(11.27,20.84) | 9.32 (6.21, 13.98) |

| Insertive rimming | ||

| Yes | 1.65 (1.36, 2.01) | 0.85 (0.69, 1.06) |

| No | 1 | 1 |

| Methamphetamine use | ||

| Yes | 3.88 (3.14, 4.80) | 1.46 (1.12, 1.92) |

| No | 1 | 1 |

| Cocaine use | ||

| Yes | 3.12 (2.57, 3.79) | 1.48 (1.16, 1.88) |

| No | 1 | 1 |

| Ecstacy use | ||

| Yes | 4.0 (3.06, 5.23) | 1.53 (1.12, 2.11) |

| No | 1 | 1 |

| Popper use | ||

| Yes | 3.27 (2.69, 3.98) | 2.10 (1.63, 2.70) |

| No | 1 | 1 |

| Any needle use | ||

| Yes | 3.69 (1.83, 7.41) | 1.54 (0.66, 3.55) |

| No | 1 | 1 |

| Alcohol use | ||

| Abstains/low to moderate | 1 | 1 |

| Moderate to heavy | 1.77 (1.44, 2.18) | 1.18 (0.94, 1.48) |

| Binge | 2.05 (1.53, 2.74) | 1.13 (0.81, 1.56) |

| Depressive symptom overall score | ||

| <=16 | 1 | 1 |

| >16 | 0.83 (0.64, 1.08) | 0.83 (0.63, 1.09) |

Early enrollment included 405 men who seroconverted between MACS visit 1 (1984–early 1985) and 15 (early – late 1991); late enrollment included 31 men who seroconverted between MACS visit 26 (late 1996 – early 1997) and 41 (early – late 2004).

Model adjusted for race/ethnicity, age at baseline, cohort, study center, education level, number of sexual partners, number of unprotected insertive anal (UIAS) sexual partners, number of unprotected receptive anal (URAS) sexual partners, insertive rimming, cocaine use, methamphetamine use, needle use, CES depression scale, ecstasy use, popper use, and alcohol consumption.

After adjusting for all the covariates, there was an independent, 1.46-fold increased relative hazard rate of HIV seroconversion associated with methamphetamine use and a two-fold increased risk associated with popper use. The number of sexual partners, cocaine or ecstasy use and race/ethnicity (Black vs. non-Hispanic White) were also independent predictors of HIV seroconversion in the multivariate model. There was a significantly increased risk with the increasing number of unprotected receptive anal sexual partners; however this pattern was not evident with the number of unprotected insertive anal sexual partners. In the multivariate model, the interplay of polydrug use attenuated the increased risk of seroconversion of each drug separately. The combined multiplicative effects of these relative hazards of methamphetamine, popper, and cocaine use exceeded by far the effect of any sociodemographic effect such as race/ethnicity.

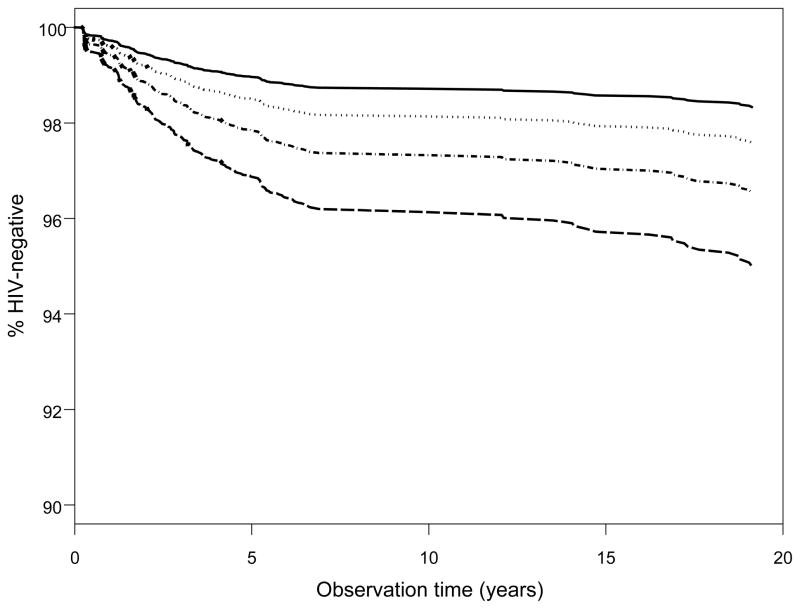

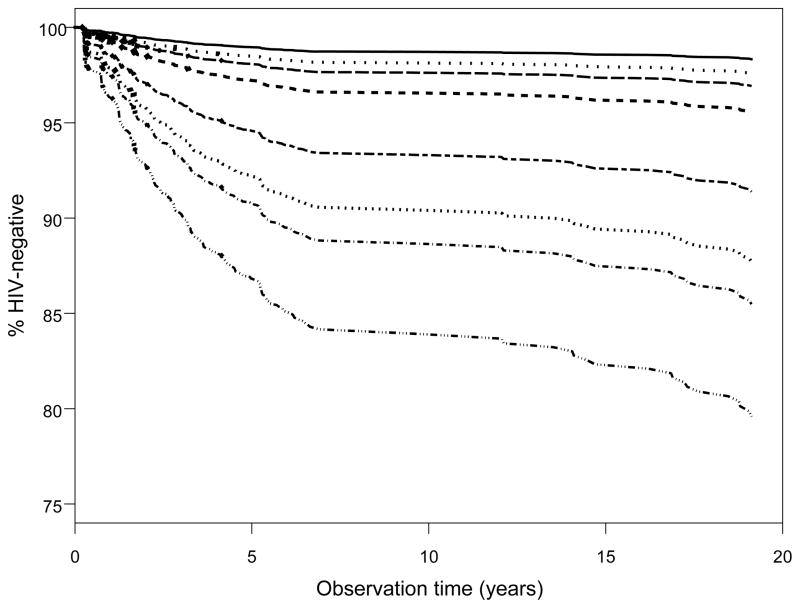

Additionally, given the high prevalence of popper use and the number of unprotected receptive anal sex partners among the seroconverters who used methamphetamine, we focused our results on these phenomena in assessing the risk of HIV seroconversion. In doing so, we found the joint relative hazard rate for methamphetamine and popper use vs. no use was 3.0 [95% CI 2.12, 4.37] (Figure 1). Most notably, there was a significant ‘dose-response’ relationship between methamphetamine use and 1, 2–4 or 5+ unprotected receptive anal sex partners with the joint relative hazard rates being 2.71 [95% CI 1.81, 4.04], 7.79 [95% CI 5.17,11.74], and 13.57 [95% CI 8.43, 21.84], respectively (Figure 2). These associations were not attenuated during later periods of study in the MACS (e.g. the relative hazards were nearly identical when we studied early visits 1–15 alone). Also, sensitivity testing demonstrated that the relative hazard rate for methamphetamine use unadjusted for the sexual practice covariates was similar [2.1, 95% CI 1.6, 2.7] to the full model. Likewise the relative hazard rates for the number of unprotected insertive and receptive anal sex partners unadjusted for methamphetamine, popper, cocaine, ecstasy, and needle use did not change compared to those from the full model. None of the 3 interaction terms tested in the full multivariate model was statistically significant.

FIGURE 1.

Adjusted time to HIV seroconversion by methamphetamine (CM) and popper (P) use. All categorical covariates set to the reference value and age was set to the average. ——: CM−/P−;· · · · · · · · · · · · ·: CM+/P−;----: CM−/P+;----: CM+/P+

FIGURE 2.

Adjusted time to HIV seroconversion by methamphetamine (CM) use and number of unprotected receptive anal sex partners (URAS). All categorical covariates set to the reference value and age was set to the average. Eight lines from the top to the bottom of figure 3 are: (1) ——: CM−/0 URAS; (2) · · · · · · · · · · · · ·: CM+/0 URAS; (3)– – –: CM−/1 URAS; (4)----: CM+/1 URAS; (5)– – –: CM−/2–4 URAS; (6) · · · · · · · · · ·: CM+/2–4 URAS; (7)----: CM−/5+ URAS; (8) — —: CM+/5+ URAS.

DISCUSSION

We found a significant association between methamphetamine use and HIV seroconversion after adjusting for other important risk factors in the MACS. In addition, we also found independent effects of popper use and number of unprotected receptive anal sex partners on HIV seroconversion. Individually, these increased relative hazards for HIV seroconversion were approximately 1.5 and two-fold, respectively; however, among men who used both drugs, the multiplicative effect reached 2.7-fold. There was a significant joint ‘dose-response’ relationship of methamphetamine use and number of unprotected anal sex partners ranging from 2.7 to 13.6-fold. Although the joint relative hazard associated with increasing number of unprotected anal sex partners is not surprising, the 2.7 increased risk of HIV seroconversion for recent methamphetamine users with only one unprotected receptive anal sex partnership is noteworthy, particularly in this cohort where 26% of seronegative men reported only one unprotected receptive anal sex encounter since their last visit.

We also examined other potential covariates of HIV seroconversion in this cohort based on earlier findings. 34, 35 Neither alcohol use per se or heavy/binge drinking contributed significantly to increased rates of HIV seroconversion in the multivariate model; other drug groups tested were also non-significant, as was needle use. These findings are consistent with other investigators’ earlier findings 19, 20, and extend those findings to a well characterized, large, longitudinal, multi-site cohort of MSM. We also found that late entry into the cohort (2001–2003) was an independent protective predictor against HIV seroconversion. This effect may possibly be due to lower viral loads in the population due to the availability of HAART, the overall decreased prevalence of stimulant use, unprotected receptive anal sex and other alternative forms of sexual risk reduction among the late cohort or perhaps the existence of different viral or host genetic characteristics in the late cohort. Regardless of any differences in these factors between the early and late entry into the cohort, the association of methamphetamine use and HIV seroconversion remained the same between the entry phases. Ultimately, this protective effect may represent a spurious finding due to the relatively low number of seroconversions among the late entry cohort members.

While the MACS participants were diverse in terms of age, socioeconomic status, race/ethnicity, geographic region, and baseline levels of HIV risk, they may not be nationally representative of MSM. All the behavioral data used in these analyses were obtained through either face-to-face interview or ACASI, both of which have been shown to produce valid estimates of sexual and drug use behavior in this type of cohort. 36 Despite the different wording of the questions eliciting methamphetamine use over the cohort visits, the drug and sexual behavior questions attempted to identify broad use or behavior within the previous 6 months and hence were limited to general use as they were not linked directly to each other. While this is a documented drawback of general behavioral data collection 37, approximately 25–30% of all MACS participants reported the use of poppers in the last 6 months, and the majority of the 12% of men who used methamphetamine were also popper users. Since the seroconversion outcome is not misclassified, any underreporting of methamphetamine, poppers, or sexual practices by the highly exposed men would underestimate the risks we presented here. Due to nearly 65 percent of missing frequency of use data we were unable to explore whether there may be a ‘dose-dependent’ relationship between frequency of methamphetamine use and sexual risk behaviors. However, the strongest advantage of this data is that all the exposures were ascertained similarly across the cohort and were obtained prior to the seroconversion outcome. Hence the inclusion of a large number of previously uninfected but sexually active MSM has permitted us to examine a cumulative ‘natural history’ of predictors of HIV seroconversion. Planned further studies will expand this “natural history” approach to acute and chronic health effects of methamphetamine and other stimulant use among both HIV-seropositive and HIV-seronegative men in the MACS.

While we cannot conclude from this study the exact mechanisms for the increased likelihood of HIV seroconversion with methamphetamine and/or poppers use associated with unprotected anal sex, it is likely to be a multi-factorial process involving behavioral disinhibition, anal trauma, and selection bias for higher risk sexual partners. Drumwright, et al. 38 have postulated a conceptual model of methamphetamine and popper use among MSM with the alteration of mental state 39, 40, reduction of pain 41, 42, enhancement of sexual function 43, 44, and increased vasodilation 45, 46 leading to tissue damage or increased bleeding, reduction of condom use, increased number of sexual partners or duration of sexual encounter as potential causative risk factors for HIV infection.

The results from this large study have replicated those found in a small cluster of previous studies. Although 90% of the MACS participants have never used methamphetamine, the 2.7-fold increased risk of HIV seroconversion associated with methamphetamine use with limited number of unprotected receptive anal sex partners provides a clear rationale for improving access to information for methamphetamine using MSM to reduce the number of sexual partners in sexual and drug-using networks characterized by high HIV seroprevalence rates resulting in a higher probability of HIV exposure.

To date, the methamphetamine-HIV concerns have been primarily focused within the Caucasian gay/bisexual community; however, swift community-based public health prevention strategies with follow-up assessment of their efficacy need to be developed and implemented before methamphetamine use captures other populations. 47, 48 Ultimately our task is to move beyond descriptive research of the methamphetamine-seroconversion relationship to better understand the dynamics of behavior and vulnerabilities to drug abuse and addiction and their intertwining with the HIV epidemic. 2 It is time to address these issues in designing primary and secondary interventions to disrupt these links.

Acknowledgments

Sources of support: The Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study is funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, with supplemental funding from the National Cancer Institute; and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute: UO1-AI-35042, 5-M01-RR-00052 (GCRC), UO1-AI-35043, UO1-AI-37984, UO1-AI-35039, UO1-AI-35040, UO1-AI-37613, and UO1-AI-35041. Additional support was provided by the National Institute of Drug Abuse through 1R01DA022936, “Long Term Health Effects of Methamphetamine Use in the MACS”, Ronald Stall, PhD., PI.

The Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study (MACS) includes the following: Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health: Joseph B. Margolick (Principal Investigator), Haroutune Armenian, Barbara Crain, Adrian Dobs, Homayoon Farzadegan, Joel Gallant, John Hylton, Lisette Johnson, Shenghan Lai, Justin McArthur, Ned Sacktor, Ola Selnes, James Shepard, Chloe Thio. Washington, DC: Michael W. Plankey. Chicago: Howard Brown Health Center, Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University, and Cook County Bureau of Health Services: John P. Phair (Principal Investigator), Joan S. Chmiel (Co-Principal Investigator), Sheila Badri, Bruce Cohen, Craig Conover, Maurice O’Gorman, David Ostrow, Frank Palella, Daina Variakojis, Steven M. Wolinsky. Los Angeles: University of California, UCLA Schools of Public Health and Medicine: Roger Detels (Principal Investigator), Barbara R. Visscher (Co-Principal Investigator), Aaron Aronow, Robert Bolan, Elizabeth Breen, Anthony Butch, Thomas Coates, Rita Effros, John Fahey, Beth Jamieson, Otoniel Martinez-Maza, Eric N. Miller, John Oishi, James A. Peck, Paul Satz, Harry Vinters, Dorothy Wiley, Mallory Witt, Otto Yang, Stephen Young, Zuo Feng Zhang. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh, Graduate School of Public Health: Charles R. Rinaldo (Principal Investigator), Lawrence Kingsley (Co-Principal Investigator), James T. Becker, Robert L. Cook, Robert W. Evans, John Mellors, Sharon Riddler, Anthony Silvestre, Ron Stall. Data Coordinating Center: The Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health: Lisa P. Jacobson (Principal Investigator), Alvaro Munoz (Co-Principal Investigator), Haitao Chu, Stephen R. Cole, Christopher Cox, Stephen J. Gange, Janet Schollenberger, Eric C. Seaberg, Sol Su. NIH: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases: Robin E. Huebner; National Cancer Institute: Geraldina Dominguez; National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute: Cheryl McDonald. Website located at http://www.statepi.jhsph.edu/macs/macs.html.

References

- 1.NIDA Community Epidemiology Working Group. Advance Report. Jun, 2005. Epidemiologic trends in drug abuse. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stall R, Purcell DW. Intertwining Epidemics: A review of research on substance use among men who have sex with men and Its connection to the AIDS epidemic. AIDS and Behavior. 2000;4(2):181–192. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gorman M, Halkitis P. Methamphetamine and club drug use and HIV. Focus. 2003 Jul;18(7):5–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reback CJ. The social construction of a gay drug: methamphetamine use among gay and bisexual males in Los Angeles. Los Angeles, CA: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Halkitis PN, Parsons JT, Wilton L. Barebacking among gay and bisexual men in New York City: explanations for the emergence of intentional unsafe behavior. Arch Sex Behav. 2003 Aug;32(4):351–357. doi: 10.1023/a:1024095016181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morin SF, Steward WT, Charlebois ED, et al. Predicting HIV transmission risk among HIV-infected men who have sex with men: findings from the healthy living project. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005 Oct 1;40(2):226–235. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000166375.16222.eb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bimbi DS. Factors related to barebacking, or intentional unprotected anal sex, among HIV-positive and HIV-negative gay and bisexual men. Paper presented at: Int Conf AIDS; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Colfax G, Coates TJ, Husnik MJ, et al. Longitudinal patterns of methamphetamine, popper (amyl nitrite), and cocaine use and high-risk sexual behavior among a cohort of san francisco men who have sex with men. J Urban Health. 2005 Mar;82(1 Suppl 1):i62–70. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jti025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crosby GM, Stall RD, Paul JP, Barrett DC, Midanik LT. Condom use among gay/bisexual male substance abusers using the timeline follow-back method. Addict Behav. 1996 Mar-Apr;21(2):249–257. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(96)00055-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dolezal C, Meyer-Bahlburg HFL, Remien RH, Petkova E. Substance use during sex and sensation seeking as predictors of sexual risk behavior among HIV+ and HIV−gay men. AIDS and Behavior. 1997;1(1):19–28. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Halkitis PN, Parsons JT, Stirratt MJ. A double epidemic: crystal methamphetamine drug use in relation to HIV transmission among gay men. J Homosex. 2001;41(2):17–35. doi: 10.1300/J082v41n02_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Halkitis PN, Green KA, Mourgues P. Longitudinal investigation of methamphetamine use among gay and bisexual men in New York City: findings from Project BUMPS. J Urban Health. 2005 Mar;82(1 Suppl 1):i18–25. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jti020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Molitor F, Truax SR, Ruiz JD, Sun RK. Association of methamphetamine use during sex with risky sexual behaviors and HIV infection among non-injection drug users. West J Med. 1998 Feb;168(2):93–97. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pendo M, DeCarlo P. CAPS Fact Sheet: How do club drugs impact HIV prevention? San Francisco: University of California San Francisco; Jul, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rekart ML, Marchand R. The “Sex Now Survey”: HIV risk and prevention for gay men in Vancouver. Paper presented at: Int AIDS Conf; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stopka TJ, Webb DS. Gay men/MSM, methamphetamine use and HIV: the California perspective. Paper presented at: Natl HIV Prev Conf; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Swanson J, Cooper A. Dangerous liaison: club drug use and HIV/AIDS. IAPAC Mon. 2002 Dec;8(12):330–338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ven PVD, Campbell D, Kippax S, et al. Factors associated with unprotected anal intercourse in gay men’s casual partnerships in Sydney, Australia. AIDS Care. 1997;9(6):637–649. doi: 10.1080/713613230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chesney MA, Barrett DC, Stall R. Histories of substance use and risk behavior: precursors to HIV seroconversion in homosexual men. Am J Public Health. 1998 Jan;88(1):113–116. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.1.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Buchacz K, McFarland W, Kellogg TA, et al. Amphetamine use is associated with increased HIV incidence among men who have sex with men in San Francisco. AIDS. 2005 Sep 2;19(13):1423–1424. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000180794.27896.fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McKirnan DJ, Vanable PA, Ostrow DG, Hope B. Expectancies of sexual “escape” and sexual risk among drug and alcohol-involved gay and bisexual men. J Subst Abuse. 2001;13(1–2):137–154. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(01)00063-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mansergh G, Colfax GN, Marks G, Rader M, Guzman R, Buchbinder S. The Circuit Party Men’s Health Survey: findings and implications for gay and bisexual men. Am J Public Health. 2001 Jun;91(6):953–958. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.6.953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Parsons JT, Bimbi DS. Intentional unprotected anal intercourse among sex who have sex with men: barebacking-from behavior to identity. AIDS Behav. 2006 Jun 15; doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9135-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mansergh G, Marks G, Colfax GN, Guzman R, Rader M, Buchbinder S. “Barebacking” in a diverse sample of men who have sex with men. AIDS. 2002 Mar 8;16(4):653–659. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200203080-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mansergh G, Shouse RL, Marks G, et al. Methamphetamine and sildenafil (Viagra) use are linked to unprotected receptive and insertive anal sex, respectively, in a sample of men who have sex with men. Sex Transm Infect. 2006 Apr;82(2):131–134. doi: 10.1136/sti.2005.017129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ostrow DG, Beltran ED, Joseph JG, DiFranceisco W, Wesch J, Chmiel JS. Recreational drugs and sexual behavior in the Chicago MACS/CCS cohort of homosexually active men. Chicago Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study (MACS)/Coping and Change Study. J Subst Abuse. 1993;5(4):311–325. doi: 10.1016/0899-3289(93)90001-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Patterson TL, Semple SJ, Zians JK, Strathdee SA. Methamphetamine-using HIV-positive men who have sex with men: correlates of polydrug use. J Urban Health. 2005 Mar;82(1 Suppl 1):i120–126. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jti031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaslow RA, Ostrow DG, Detels R, Phair JP, Polk BF, Rinaldo CR., Jr The Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study: rationale, organization, and selected characteristics of the participants. Am J Epidemiol. 1987 Aug;126(2):310–318. doi: 10.1093/aje/126.2.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dudley J, Jin S, Hoover D, Metz S, Thackeray R, Chmiel J. The Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study: retention after 9 1/2 years. Am J Epidemiol. 1995 Aug 1;142(3):323–330. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gribble JN, Miller HG, Cooley PC, Catania JA, Pollack L, Turner CF. The impact of T-ACASI interviewing on reported drug use among men who have sex with men. Subst Use Misuse. 2000 May-Jun;35(6–8):869–890. doi: 10.3109/10826080009148425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Radloff LS, Rae DS. Susceptibility and precipitating factors in depression: sex differences and similarities. J Abnorm Psychol. 1979 Apr;88(2):174–181. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.88.2.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cox DR, Oakes R. Analysis of survival data. London: Chapman and Hall; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Klein JP, Moeschberger ML. Survival analysis: techniques for censored and truncated data. 2. New York: Springer-Verlag; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ostrow DG, DiFranceisco WJ, Chmiel JS, Wagstaff DA, Wesch J. A case-control study of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 seroconversion and risk-related behaviors in the Chicago MACS/CCS Cohort, 1984–1992. Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study. Coping and Change Study. Am J Epidemiol. 1995 Oct 15;142(8):875–883. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Detels R, English P, Visscher BR, et al. Seroconversion, sexual activity, and condom use among 2915 HIV seronegative men followed for up to 2 years. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1989;2(1):77–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fenton KA, Johnson AM, McManus S, Erens B. Measuring sexual behaviour: methodological challenges in survey research. Sex Transm Infect. 2001 Apr;77(2):84–92. doi: 10.1136/sti.77.2.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leigh BC, Stall R. Substance use and risky sexual behavior for exposure to HIV. Issues in methodology, interpretation, and prevention. Am Psychol. 1993 Oct;48(10):1035–1045. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.48.10.1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Drumright LN, Patterson TL, Strathdee SA. Club Drugs as causal risk factors for HIV acquisition among men who have sex with men: A review. Subst Use Misuse. 2006;41(10):1551–1601. doi: 10.1080/10826080600847894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Murray JB. Psychophysiological aspects of amphetamine-methamphetamine abuse. J Psychol. 1998 Mar;132(2):227–237. doi: 10.1080/00223989809599162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nordahl TE, Salo R, Leamon M. Neuropsychological effects of chronic methamphetamine use on neurotransmitters and cognition: a review. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2003 Summer;15(3):317–325. doi: 10.1176/jnp.15.3.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Green AI. “Chem friendly”: the institutional basis of “club drug” use in a sample of urban gay men. Deviant Behav. 2003;24:427–447. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Romanelli F, Smith KM, Thornton AC, Pomeroy C. Poppers: epidemiology and clinical management of inhaled nitrite abuse. Pharmacotherapy. 2004 Jan;24(1):69–78. doi: 10.1592/phco.24.1.69.34801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kurtz SP. Post-circuit blues: motivations and consequences of crystal meth use among gay men in Miami. AIDS Behav. 2005 Mar;9(1):63–72. doi: 10.1007/s10461-005-1682-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Green AI. “Chem friendly”: the institutional basis of “club drug” use in a sample of urban gay men. Deviant Behav. 2003;24:427–447. [Google Scholar]

- 45.French RS, Power R. Self-reported effects of alkyl nitrate use: a qualitative study amongst targeted groups. Addict Res. 2001;28:57–76. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mayer KH. Medical consequences of the inhalation of volatile nitrites. In: Ostrow DG, Sandholzer TA, Felman YM, editors. Sexually transmitted diseases in homosexual men: diagnosis, treatment and research. New York: Plenum Press; 1983. pp. 237–242. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jacobs A. New York Times. Feb 21, 2006. Battling HIV where sex meets crystal meth. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Krawczyk C. Methamphetamine use and HIV risk behaviors among heterosexual men - preliminary results from five Northern California counties, December 2001–November 2003. MMWR. 2006;55(10):273–277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]