Abstract

Background:

The development of nutrition care programs for patients undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation is necessity in view of the rapid and aggressive consequences frequently seen with this procedure. Patients require constant care to reduce complications and to contribute to the success of therapy.

Methods:

In an attempt to ascertain the impact of systematic nutritional care on patients submitted to allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, the present study assessed the nutritional and clinical status, use of parenteral nutrition, and complication and mortality rates in two groups of patients, who were submitted to transplantation between April 2003 and December 2004 (Non-intervention Group - NIG; n = 57) and between March 2006 and January 2008 (Intervention Group - IG; n = 34).

Results:

There were no significant differences between groups in terms of clinical or nutritional profiles. Additionally, the length of hospital stay and complication and mortality rates were similar for both groups. However, time on parenteral nutrition during treatment was shorter for the IG [median 6.5 days (range: 1-28) for related donor recipients and 11 days (range: 1-21) for unrelated donor recipients] than for the NIG [median 20.5 days (range, 4-73) for patients submitted to myeloablative conditioning and 18.5 days (range: 11-59 days) for those submitted to nonablative conditioning].

Conclusion:

The implementation of a nutritional follow-up and therapy protocol for adult patients submitted to hematopoietic stem cell transplantation shortens the duration of parenteral nutrition. It certainly has an impact on hospitalization costs and, potentially, on the rate of complications, even though this was not demonstrated in this study.

Keywords: Nutrition assessment, Parenteral nutrition solutions, Bone marrow transplantation, Nutritional support, Stem cell transplantation

Introduction

Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) is a therapeutic procedure that consists of high-dose chemotherapy followed by an infusion of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) derived from harvested bone marrow or peripheral blood, with the objective of restoring hematopoietic system function. There are two types of HSCT, autologous (patients receive their own, previously-harvested HSCs) and allogeneic (patients receive HSCs harvested from a related or unrelated donor). For autologous HSCT, patients receive high-dose chemotherapy and mean time to engraftment and the duration of neutropenia and mucositis may differ from those of allogeneic transplant recipients(1,2). For allogeneic HSCT, patients also undergo conditioning regimens that combine high-dose chemotherapy and total body irradiation to induce immunosuppression. Total body irradiation is extremely toxic and leads to severe, protracted mucositis, which is a risk factor for malnutrition, as is the underlying disease(3). Graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), which may occur within 10 to 12 days of transplantation, produces more severe complications, particularly in the gastrointestinal tract. High-dose corticosteroid therapy for GVHD management and the use of antiviral drugs to prevent infectious complications also contribute to malnutrition(4,5).

Malnutrition is a common issue in oncology patients, and worse clinical outcomes have beenreported in malnourished patients. The goal of nutritional therapy (NT) is to prevent malnutrition secondary to complications and, consequently, prevent worse clinical outcomes(6-9). Although many patients are able to feed orally, intake is often insufficient and requires complementation, whether by enteral feeding (EN) and/or parenteral nutrition (PN). PN is the most widely used alternative, in view of the gastrointestinal problems induced by the clinical complications of induction, radiation, chemotherapy, and other HSCT-related procedures(10). However, there is no consensus as to the optimal timing for PN and nutritional requirements (calories per kg of body weight, nonprotein calorie to nitrogen ratio, and grams of protein per kg of body weight) in these patients(6).

Given this lack of consensus, there is wide variability in the management of patients with respect to PN. The literature has shown a pressing need for the development and implementationof adequate PN protocols for this patient population with better clinical outcomes having been described in patients enrolled in such protocols(11-14). Due to the difficulty of achieving consensus,there has been little development of nutritional care protocols for patients with cancer as to optimal nutritional therapy, to the variability in current management and to the lack of external validation of management strategies(8,15). Current criteria for the prescription of PN range from routine use in all patients with severe malnutrition to prolonged periods (7 to 10 days) of minimal oral intake or significant weight loss (> 10% of body weight) during treatment(16,19).

The effects of nutritional care practices on quality of life, toxicity, and prognosis in cancer patients are still unknown. However, there is evidence to support the assertion that early nutritional supplementation may prevent or decrease the severity of the most common debilitating complications of HSCT(20). Therefore, the present study sought to assess the clinical impact of systematic nutritional care on a sample of patients submitted to allogeneic HSCT.

Methods

This double cohort study was carried out on a sample of adult patients (age >18 years) undergoing allogeneic HSCT. Two groups of patients were formed relating to two assessment periods: from April 2003 to April 2004, which constituted the Non-intervention Group (NIG), and from March 2006 to January 2008, which constituted the Intervention Group (IG). The intervention evaluated in this study, systematic nutritional care for HSCT patients, was implemented in 2005; therefore, patients admitted over the course of this year were not included in the study, as this was atransitional period for adaptation. All patients were enrolled only once, at the time of HSCT. Patients admitted for retransplantation or management of HSCT complications were not included.

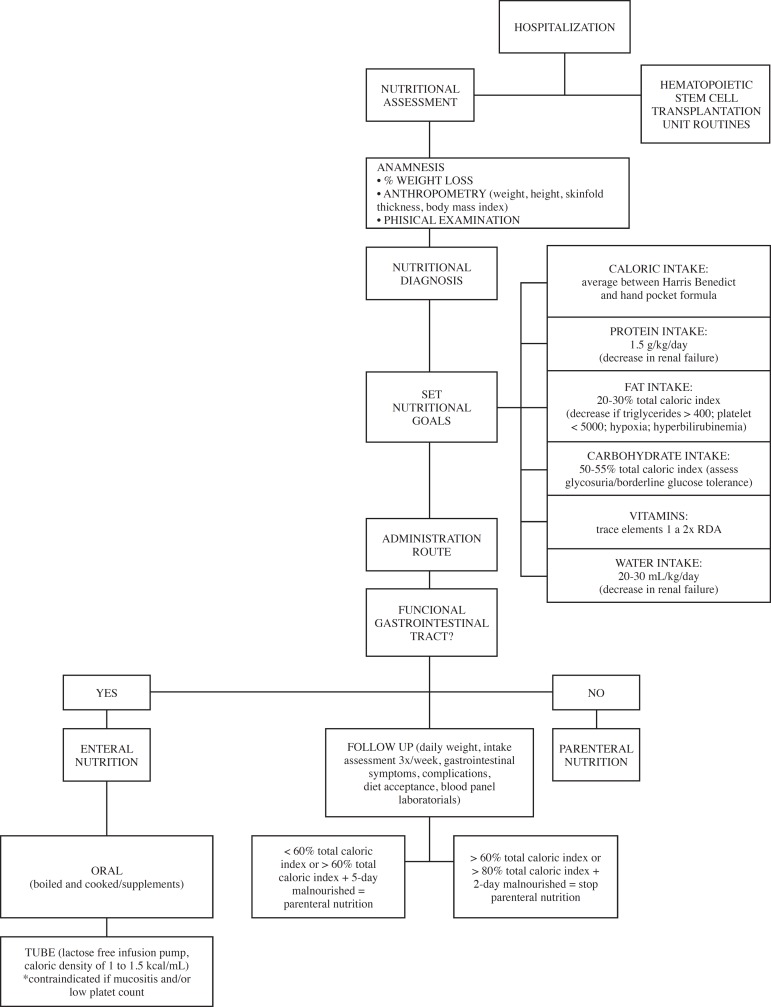

The NIG was constructed retrospectively through analysis ofthe database of the Department of Hematology at the Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre (HCPA), Brazil, where the study was carriedout. In 2005, the HCPA Physician Nutrition Specialist Service, Nutrition and Dietetics Service and Department of Hematology jointly developed and implemented a protocol of routine, systematic nutritional care for all adult HSCT patients (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the study design

The IG was assessed prospectively for the same variables analyzed in the NIG, as described below. IG follow-up was led by the medical and nutritional teams of the HSCT unit. No changes were made in the type of diet or supplemental nutrition provided between the pre-intervention and post-intervention periods, but criteria for institution and discontinuation of PN, according to oral intake, were established. Clinical and nutritional parameters were assessed by meansof a standard protocol, which was used in both groups. Nutritional assessment was carried out by a staff dietitian in the HSCT unit or by a previously trained student dietitian on admission and throughout the hospital stay. Body mass index (BMI), mid-upper arm circumference (MUAC), triceps skinfold thickness (TSF), and percent weight loss (%WL) were assessed. Weight was measured at the HSCT unit usingdigital scales with stadiometer (OS 180 A®, Urano). MUAC wasmeasured with a flexible, non-stretch anthropometric measuring tape (Barlow®) and TSF, with a skinfold caliper (Cescorf®), in accordance with World Health Organization (WHO) recommendations. BMI, %WL and MUAC were calculated as per WHO recommendations(19).

Mortality, infection, and prolonged hospital stay were considered dependent variables. Hospital-acquired infection was defined as any infection that developed during hospitalization, regardless of site of origin, in accordance with the local Hospital-Acquired Infection Control Committee (HAICC) protocols. Prolonged length of stay was defined as any hospitalization exceeding the mean length expected for HSCT recipients, i.e. 56 days.

Statistical analysis

Study variables were analyzed in the SPSS 17.0. software environment. The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to determine normality and variables were then expressed as means and standard deviations or medians and ranges depending on their distribution. Relative frequencies (percentages) were also used in describing the sample. Significance was set for a p-value < 0.05.

Results

The NIG (pre-implementation of the study intervention, 2002-2004) comprised 57 patients whereas the IG (post-implementation, 2006-2008) comprised 34 patients. Table 1 shows the distribution of hematological diseases of patients in each of the study groups.

Table 1.

Distribution of indications for hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in the Non-intervention and Intervention Groups

| Disease | NIG | NIG |

| n (%) | n (%) | |

| Aplastic anemia | 5 (8.8) | 4 (11.7) |

| Myelodysplasia | 3 (5.3) | 7 (20.6) |

| Hodgkin's disease | 2 (3.5) | 2 (5.9) |

| Leukemia, acute biphenotypic or lymphoblastic | 8 (14.1) | 3 (8.8) |

| Leukemia, chronic lymphocytic | 2 (3.5) | 0 |

| Leukemia, acute myeloid | 14 (24.6) | 9 (26.5) |

| Leukemia, chronic myeloid | 15 (26.3) | 6 (17.7) |

| Lymphoma, T-cell | 2 (3.5) | 0 |

| Lymphoma, non-Hodgkin | 4 (7.02) | 3 (8.8) |

| Multiple myeloma | 2 (3.5) | 0 |

Table 2 shows the demographic profile of the two groups and the distribution of graft type and conditioning regimen.

Table 2.

Median age, gender, distribution, graft type and conditioning regimen for the Non-intervention and Intervention Groups

| NIG | IG | p-value | |

| Age (years) - median (range) | 37 (19-55) | 35 (19-60) | 0.249 |

| Females - n (%) | 35 (61.4) | 14 (41.2) | 0.063 |

| Males - n (%) | 22 (38.6) | 20 (58.8) | |

| Related-donor - n (%) | 57 (100) | 25 (73.5) | 0.000 |

| Unrelated-donor - n (%) | 0 | 9 (26.5) | |

| Myeloablative conditioning - n (%) | 43 (75.4) | 27 (79.4) | 0.665 |

| Non-myeloablative conditioning - n (%) | 14 (24.6) | 7 (20.6) |

Anthropometric assessment showed no significant pre-hospitalization weight loss in either group. Mean weight loss was 0.83% (range: -1.48 to 4.8%) in the NIG and 0.14% (range: -3.8 to 4.8%) in the IG. Mean BMI was 25.28 kg/m2 (range: 22.65 to 28.03 kg/m2) in the NIG and 24.89 kg/m2 (range: 21.95 to 28.82 kg/m2) in the IG(21). There were no significant differences between groups in respect to anthropometric parameters (DCT, CB and CMB) on admission.

PN was prescribed to 30 (52.6%) patients in the NIG and 20 patients (58.8%) in the IG. The duration of PN, mean PN calorie intake and mean oral calorie intake are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Comparison between duration of parenteral nutrition and mean caloric intake in the Non-intervention and Intervention Groups

| Non-intervention Group | Intervention Group | ||||||

| Graft type | Conditioning regimen | Graft type | Conditioning regimen | ||||

| Related donor n = 57 (100%) | Myeloablative n = 42 (73.7%) | Nonablative n = 15 (26.3%) | Related donor n = 25 (73.5%) | Unrelated donor n = 9 (26.5%) | Myeloablative n = 28 (82.3%) | Nonablative n = 6 (17.7%) | |

| Patients receiving PN - n (%) | 30 (52.6) | 26 (61.9) | 4 (26.6) | 14 (56) | 6 (66.6) | 20 (71.4) | 0 |

| Duration of PN (days) - median (range) | 20.5 (4-73) | 20.5 (4-73) | 18.5 (11-59) | 6.5 (1-28) | 11 (1-21) | 7 (1-28) | 0 |

| Daily PN calorie intake (kcal) - Mean ± SD | 1554 ± 309 | 1600 ± 259 | 1395 ± 425 | 1516 ±250 | 1343 ± 462 | 1480 ± 299 | 0 |

| Mean daily oral intake during oral feeding (kcal) - Mean ± SD | 1310 ± 465 | 1288 ± 446 | 1366 ± 525 | 1642 ± 586 | 1646 ± 598 | 1609 ± 616 | 1801±366 |

PN: parenteral nutrition; SD; Standard deviation

There were no significant differences between related-donor and unrelated-donor graft recipients with respect to any of the outcomes of interest (Table 4).

Table 4.

Comparison between main outcomes by group (Non-intervention vs. Intervention Group): graft type, and conditioning regimen

| Non-intervention Group | Intervention Group | ||||||

| Graft type | Conditioning regimen | Graft type | Conditioning regimen | ||||

| Related donor n = 57 | Myeloablative n = 42 | Nonablative n = 15 | Related donor n = 25 | Unrelated donor n = 9 | Myeloablative n = 28 | Nonablative n = 6 | |

| Hospital stay (days) - median (range) | 43 (15-101) | 43 (15-93) | 41 (28-101) | 41 (23-89) | 48 (24-117) | 42.5 (23-117) | 36 (24-78) |

| Infections - n (%) | 39 (68.4) | 25 (59.5) | 14 (93.3) | 17 (68) | 5 (55.5) | 18 (64.3) | 4 (6.66) |

| In-hospital deaths - n (%) | 9 (15.8) | 9 (15.8) | 0 | 5 (20) | 5 (55.5) | 7 (25) | 1 (16.6) |

| Death at 6 months - n (%) | 14 (24.6) | 12 (28.6) | 2 (13.3) | 8 (32) | 3 (33.3) | 10 (35.7) | 1 (16.6) |

| Death at 12 months - n (%) | 29 (50.9) | 22 (52.4) | 7 (4.6) | 7 (28) | 3 (33.3) | 10 (35.7) | 0 |

| Number post-HSCT admissions - median (range) | 2 (0-16) | 2 (0-16) | 2(0-15) | 3 (1-14) | 7 (0-14) | 5 (1-14) | 2.5 (0-12) |

| Chronic GVHD - n (%) | |||||||

| None | 34 (59.65) | 29 (69) | 5 (33.3) | 20 (80) | 9 (100) | 24 (85.7) | 5 (83.3) |

| Limited | 13 (22.8) | 8 (19) | 5 (33.3) | 4 (16) | 0 | 4 (14.3) | 0 |

| Extensive | 10 (17.5) | 5 (11.9) | 5 (33.3) | 1 (4) | 0 | 0 | 1 (16.6) |

| Acute GVHD - n (%) | |||||||

| Grade I/II | 14 (24.6) | 8 (19) | 6 (40) | 9 (36) | 3 (33.3) | 10 (35.7) | 2 (33.3) |

| Grade III/IV | 10 (17.5) | 7 (16.6) | 3 (20) | 3 (12) | 1 (11.1) | 3 (10.7) | 1 (16.6) |

| CMV - n (%) | 10 (17.5) | 8 (19) | 2 (13.3) | 7 (28) | 4 (44.4) | 8 (28.6) | 3 (50) |

| In-hospital weight loss > 10% - n (%) | 22 (38.6) | 14 (33.3) | 8 (53.3) | 10 (40) | 5 (55.5) | 12 42.8) | 3 (50) |

| Neutropenia - n (%) | 55 (96.5) | 41 (97.6) | 14 (93.3) | 20 (80) | 8 (88.8) | 22 (78.5) | 6 (100) |

HSCT: Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; GVHD: Graft versus host disease; CMV: Cytomegalovirus

There were no significant differences between groups in length of hospital stay, prolonged hospitalization rate, presence and severity of GVHD, infection rate, or duration of neutropenia.

There were no significant differences between groups in inhospital death or post-transplant mortality at 6 months or 12 months.

Discussion

Nutritional and clinical assessment revealed no significant differences between groups for any of the variables of interest, confirming the similarity in nutritional and clinical profile of the study sample prior to the intervention.

Less PN was given to patients in the IG than those in the NIG; however, as both groups were similar at the time of HSCT, this means that prescription of PN was optimized in the IG. This rationalization of management after the implementation of a nutritional care protocol will certainly have reduced hospital costs.

There were no significant differences in the post-HSCT complication rates, infection rates or lengths of hospital stay. This may be explained by the fact that length of stay is determined by the duration of treatment itself, that the mortality rate may have been the same due to universally adequate treatment and that PN-associated infection rates are mostly determined by care in compounding(22).

In the present study, 52% of patients in the NIG and 58% of those in the IG received PN. This is within the range reported in the literature, where the percentage of HSCT patients given PN ranges from 37% in autologous graft recipients to 91% in unrelated-donor allogeneic graft recipients(16).

The duration of PN may have an impact on catheter-related infection rates and on hospitalization costs. In the literature, the mean duration of PN after HSCT ranges from 6.9-16 days after autologous transplantation and 10.3-25 days after allogeneic ransplantation(15,16,23). The present study showed a reduction in PN duration in the IG. Use of a nutritional care protocol, including control and optimization of food intake, in these patients may reduce the duration of PN by approximately 14 days in patients undergoing related-donor allogeneic HSCT. We found in this work a median duration of PN of 6.5 days (range: 1-28) in related-donorgraft recipients and 11 days (range: 1-21) in unrelated-donor graft recipients. This duration is well short of that usually reported in the literature for allogeneic HSCT recipients. Although other factors associated with better care in these patients (such as better use of antiemetics and prophylaxis for GVHD) may have had an impact, monitoring of dietary intake plays an essential role in determining when to discontinue parenteral nutrition(16).

We believe PN should not be used routinely as first-line therapy, but rather restricted to patients who are unable to tolerate enteral feeding and will derive real benefit from PN(24).

HSCT patients who receive PN, when indicated, may experience fewer complications when adequate nutritional supportis provided(13,25). Furthermore, the lack of adequate nutritional support may lead to increased complication rates and prolong hospitalization, consequently leading to higher hospital costs(14,23).

Conclusion

The implementation of a systematic nutritional follow-up and therapy protocol for adult patients undergoing allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation optimized (shortened) the duration of parenteral nutrition.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interest

References

- 1.Harousseau JL.Role of stem cell transplantation Hematol Oncol Clin North Am 20072 (6) 1157–1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harousseau JL.The allogeneic dilemma Bone Marrow Transplant 200740 (12) 1123–1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhatt V, Vendrell N, Nau K, Crumb D, Roy V.Implementation of a standardized protocol for prevention and management of oral mucositis in patients undergoing hematopoietic cell transplantation J Oncol Pharm Pract 201016 (3) 195–204.Comment on: J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2012;18(1):158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murray SM, Pindoria S.Nutrition support for bone marrow transplant patients Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2002. (2) CD002920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ordóñez González FJ, Jiménez Jiménez FJ, Delgado Pozo JA. Parenteral nutrition in hematologic patients treated with hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Nutr Hosp. 2000;15(Suppl 1):114–120. Spanish. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hadjibabaie M, Iravani M, Taghizadeh M, Ataie-Jafari A, Shamshiri AR, Mousavi SA, et al. Evaluation of nutritional status in patients undergoing hematopoietic SCT Bone Marrow Transplant 200842 (7) 469–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rzepecki P, Barzal J, Sarosiek T, Oborska S, Szczylik C.Which parameters of nutritional status should we choose for nutritional assessment during hematopoietic stem cell transplantation? Transplant Proc 200739 (9) 2902–2904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thompson JL, Duffy J.Nutrition support challenges in hematopoietic stem cell transplant patients Nutr Clin Pract 200823 (5) 533–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fearon KC, Von Meyenfeldt MF, Moses AG, Van Geenen R, Roy A, Gouma DJ, et al. Effect of a protein and energy dense N-3 fatty acid enriched oral supplement on loss of weight and lean tissue in cancer cachexia: a randomised double blind trial Gut 200352 (10) 1479–1486.Comment in: Blood. 2003;52(10):1391-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.August DA, Huhmann MB, American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (A.S.P.E.N.) Board of Directors A.S.P.E.N. clinical guidelines: nutrition support therapy during adult anticancer treatment and in hematopoietic cell transplantation JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 200933 (5) 472–500.Comment in: JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2010;34(4):455; author reply 456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klein CJ, Stanek GS, Wiles CE 3rd.Overfeeding macronutrients to critically ill adults: metabolic complications J Am Diet Assoc 199898 (7) 795–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Muscaritoli M, Grieco G, Capria S, Iori AP, Rossi Fanelli F.Nutritional and metabolic support in patients undergoing bone marrow transplantation Am J Clin Nutr 200275 (2) 183–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bozzetti F, SCRINIO Working Group Screening the nutritional status in oncology: a preliminary report on 1,000 outpatients Support Care Cancer 200917 (3) 279–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Horsley P, Bauer J, Gallagher B.Poor nutritional status prior to peripheral blood stem cell transplantation is associated with increased length of hospital stay Bone Marrow Transplant 200535 (11) 1113–1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weisdorf SA, Lysne J, Wind D, Haake RJ, Sharp HL, Goldman A, et al. Positive effect of prophylactic total parenteral nutrition on long-term outcome of bone marrow transplantation Transplantation 198743 (6) 833–838. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scolapio JS, Tarrosa VB, Stoner GL, Moreno-Aspitia A, Solberg LA Jr, Atkinson EJ.Audit of nutrition support for hematopoietic stem cell transplantation at a single institution Mayo Clin Proc 200277 (7) 654–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iestra JA, Fibbe WE, Zwinderman AH, Romijn JA, Kromhout D.Parenteral nutrition following intensive cytotoxic therapy: an exploratory study on the need for parenteral nutrition after various treatment approaches for haematological malignancies Bone Marrow Transplant 199923 (9) 933–939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martin-Salces M, de Paz R, Canales MA, Mesejo A, Hernandez-Navarro F.Nutritional recommendations in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation Nutrition 200824 (7-8) 769–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.World Health Organization Physical status: The use and interpretation of anthropometry. Report of a WHO Expert Committee. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 1995;854:1–452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zatarain L, Savani BN.The role of nutrition and effects on the cytokine milieu in allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation Cell Immunol 2012276 (1-2) 6–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sommacal HM, Jochims AM, Schuch I, Silla LM.Comparison of nutritional assessment methods employed to monitor patients undergoing Rev Bras Hemat Hemot 201032 (1) 28–33. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beghetto MG, Victorino J, Teixeira L, de Azevedo MJ.Parenteral nutrition as a risk factor for central venous catheter-related infection JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 200529 (5) 367–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sonis ST, Oster G, Fuchs H, Bellm L, Bradford WZ, Edelsberg J, et al. Oral mucositis and the clinical and economic outcomes of hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation J Clin Oncol 200119 (8) 2201–2205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arfons LM, Lazarus HM.Total parenteral nutrition and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: an expensive placebo? Bone Marrow Transplant 200536 (4) 281–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.ASPEN Board of Directors. Clinical Guidelines Task Force Guidelines for the use of parenteral and enteral nutrition in adult and pediatric patients JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 200226 (1) Suppl1SA–138SA.Erratum in: JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2002;26(2):144 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]