Abstract

Herein we report the synthesis of the mixed ligand paddlewheel complex dirhodium(II) tris[N-phthaloyl-(S)-tert-leucinate] triphenylacetate, Rh2(S-PTTL)3TPA, the structure of which bears similarity to the chiral crown complex Rh2(S-PTTL)4. Rh2(S-PTTL)3TPA engages substrate classes (aliphatic alkynes, silylacetylenes, α-olefins) that are especially challenging in intermolecular reactions of α-alkyl-α-diazoesters, and catalyzes enantioselective cyclopropanation, cyclopropenation, and indole C-H functionalization with yields and enantioselectivities that are comparable or superior to Rh2(S-PTTL)4. Mixing ligands on paddlewheel complexes offers a versatile handle for diversifying catalyst structure and reactivity. The results described herein illustrate how mixed ligand catalysts can create new opportunities for the optimization of catalytic asymmetric processes.

Rh(II)-carboxylate catalysts supported by N-phthaloyl- and N-naphthaloyl amino acid ligands are robust tools for asymmetric synthesis.1 These catalysts were pioneered by Hashimoto,2 and in recent years have opened new modes of reactivity including highly enantioselective cyclopropanation3, cyclopropenation4, and C-H functionalization5 of α-alkyl-α-diazoesters; cyclopropanation and C-H functionalization of α-aryl- and α-vinyl- α-diazoesters6; cyclopropanation of PMP-α-diazoketones,7 and cycloadditions of β-keto-α-diazoesters8.

We recently reported that dirhodium(II) tetrakis[N-phthaloyl-(S)-tert-leucinate], Rh2(S-PTTL)4 (Fig. 1), gives high enantioselectivity in the cyclopropanation reactions of α-alkyl-α-diazoesters.3 The model for enantioselectivity was explained by a “chiral crown” structure, in which all four N-phthalimide groups are presented on the same face of the catalyst in an α, α, α, α conformation.9 Charette also proposed that the α, α, α, α conformation is important for Rh-catalysts supported by N-phthaloyl amino acid ligands in cyclopropanation reactions of α-4-methoxyphenyl-α-diazoketones.7 Crystallographic support for the chiral crown structure in bimetallic paddlewheel complexes has been established in subsequent study10, which includes work on Rh2(S-NTTL)4 catalyzed cyclopropanation by Ghanem,11 Rh2(S-TBPTTL)4 catalyzed cyclopropenation4 by Hashimoto, and Rh2(S-NTTL)4 catalyzed C-H functionalization of indoles by our group.5

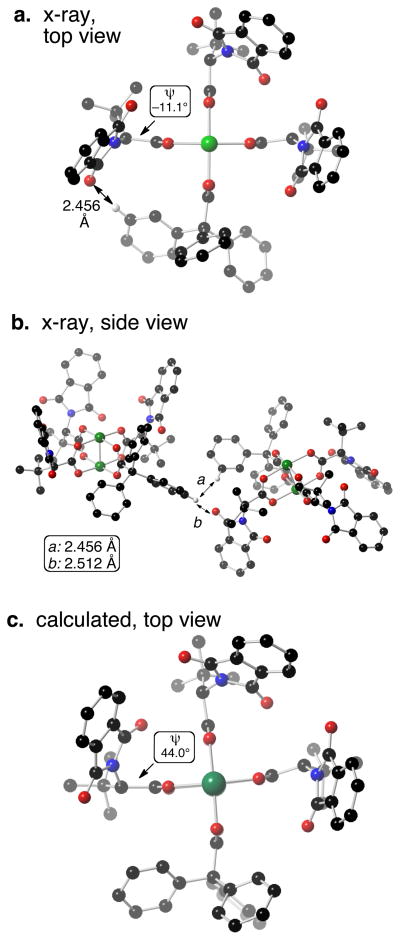

Fig. 1.

(a) Top view and (b) side view of crystal structure of Rh2(S-PTTL) 3TPA. Axial ethanol ligands are not displayed. (c) Lowest energy conformation of Rh2(S-PTTL) 3TPA from DFT calculation.

|

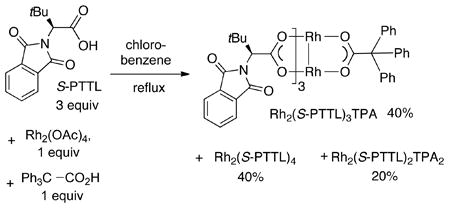

(1) |

The chiral crown structure offers a unique platform for catalyst design. Inspection of transition state models involving chiral crown catalysts implies that non-covalent ligand-substrate interactions contribute to the induction of asymmetry.3,5,7 We hypothesized that the chiral pocket would still be maintained in structures where one of the chiral carboxylate ligands of Rh2(S-PTTL)4 was replaced by an achiral ligand. We further reasoned that introducing a ligand with a large aromatic surface area could have a beneficial influence on the yield and enantioselectivity in intermolecular reactions. Herein, we report the mixed ligand catalyst dirhodium(II) tris [N-phthaloyl-(S)-tert-leucinate] triphenylacetate, Rh2(S-PTTL)3TPA (Eq 1). Computational and crystallographic studies show that Rh2(S-PTTL)3TPA adopts a structure in which the N-phthaloyl groups are presented on the same face of the catalyst. For a number of recalcitrant substrates, Rh2(S-PTTL)3TPA is shown to give results in enantioselective cyclopropanation, cyclopropenation, and indole C-H functionalization that are superior to the parent catalyst, Rh2(S-PTTL)4.

While studies on chiral bimetallic rhodium (II) complexes have been extensive,12 there has been relatively little study on bimetallic Rh(II) complexes bearing different ligand types. Corey reported that Rh2(DPTI)3(OAc), which is capable of achieving high enantioselectivity in cyclopropenation and cyclopropanation reactions of ethyl diazoacetate.13 Doyle has reported immobilized Rh(II) mixed ligand carboxamidates as useful catalysts for intramolecular cyclopropanation and C-H insertion reactions,13 and Hashimoto has reported a polymer-supported analogue of Rh2(S-PTTL)4 as a useful recyclable catalyst for C-H insertion reactions.13 Concurrent with the work being reported here, Charette and coworkers have developed chiral Rh-catalysts bearing mixed N-phthaloyl amino acid ligands that give excellent enantioselectivity in the cyclopropanation reaction of α-nitro-α-diazo-p-methoxyacetophenone with styrene.14

As shown in Eq. 1, the unsymmetrical complex Rh2(S-PTTL)3TPA can be synthesized in 40% yield by simply combining N-phthaloyl-(S)-tert-leucinate (3 equiv), triphenylacetic acid (1 equiv) and Rh2(OAc)4 (1 equiv). Also formed in the reaction are Rh2(S-PTTL)4 (40%) and isomers of Rh2(S-PTTL)2TPA2 (20%).

We began work on Rh2(S-PTTL)3TPA with computational and crystallographic studies. Crystals of Rh2(S-PTTL)3TPA were grown from ethanol. Rh2(S-PTTL)3TPA adopts a conformation in the solid state in which all of the phthaloyl groups are displayed on the α-face (Fig 1a–b). When DFT calculations (B3LYP/LAN2DZ) were used to computationally optimize the crystallographic coordinates, the lowest energy structure displayed in Fig 1c was found. An energetically and structurally similar structure to the one displayed in Fig 1c was also found as the result of a conformational search.15 Starting from several different conformations, Rh2(S-PTTL)3TPA was subjected to molecular dynamics-based conformational (LowModeMD16), and the lowest energy structures were optimized using DFT calculations (B3LYP/LAN2DZ).

The largest difference between the computed and solid state structures of Rh2(S-PTTL)3TPA is the ψ-angle for one the PTTL ligands, which is −11.1° in the x-ray structure (Fig 1b), but 44.0° in the calculated structure (Fig 1a). This clockwise ψ-angle twist17 in the crystal structure may be a result of attractive intramolecular (2.456 Å) and intermolecular (2.512 Å) interactions between the phthalimide carbonyl and a nearby aromatic hydrogen from the TPA ligand. However, there is an overall good agreement between the predicted and crystallized structure of Rh2(S-PTTL)3TPA.

As shown in table 1, the reaction to produce Rh2(S-PTTL)3TPA also produced isomers of Rh2(S-PTTL)2TPA2 (20%). The cis-isomer crystallized from a solution of CD3CN. In the x-ray structure of cis-Rh2(S-PTTL)2TPA2, both phthalimido groups are projected on the same face of the catalyst.

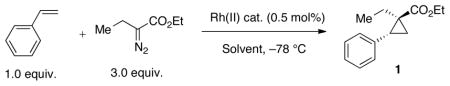

Table 1.

Catalyst screening for enantioselective cyclopropanation of styrene with ethyl α-diazobutanonate: Rh2(S-BPTTL)4= dirhodium(II) tetrakis[N-2,3-naphthaloyl-(S)-tert-leucinate]; Rh2(S-NTTL)4= dirhodium(II) tetrakis[N-1,8-naphthaloyl-(S)-tert-leucinate]; Rh2(S-TBPTTL)4= dirhodium(II) tetrakis[N-tetrabromophthaloyl-(S)-tert-leucinate];

; ; | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rh(II) Catalyst | Solvent | %yda | drb | %eec |

| Rh2(S-PTTL)4 | Hexanes | 95 | 92:8 | 79 |

| Rh2(S-BPTTL)4 | Toluene | 80 | 88:12 | 73 |

| Rh2(S-NTTL)4 | Toluene | 61 | 75:25 | 45 |

| Rh2(S-TBPTTL)4 | CH2Cl2 | 6 | 97:3 | 11 |

| Rh2(S-TBPTTL)4 | Toluene | 10 | 88:12 | 16 |

| Rh2(S-TBPTTL)4 | Hexanes | 23d | 84:16 | 16 |

| Rh2(TPA)(S-PTTL)3 | Toluene | 66 | 95:5 | 81 |

| Rh2(TPA)(S-PTTL)3 | Hexanes | 91 | 96:4 | 88 |

Isolated yields.

Measured by GC.

Measured by chiral HPLC.

Run at −60 °C for 2 hours. No reaction occurred at −78 °C.

As reported previously, the Rh2(S-PTTL)4 catalyzedcyclopropanation of styrene by ethyl-α-diazobutanoate was not particularly enantioselective, providing 1 in 79% ee. As shown in Table 1, a number of Rh-catalysts were surveyed, including Rh2(S-NTTL)4, the most useful catalyst from our prior work on indole C-H functionalization,5 and Rh2(S-TBPTTL)4, a catalyst recently reported by Hashimoto to be useful in cyclopropenation4 and also reported to be useful in the cyclopropanation of α-diazopropionates.18 Of the catalysts surveyed, Rh2(S-PTTL)3TPA gave the best enantioselectivity in hexanes with 88% ee (Table 1).19

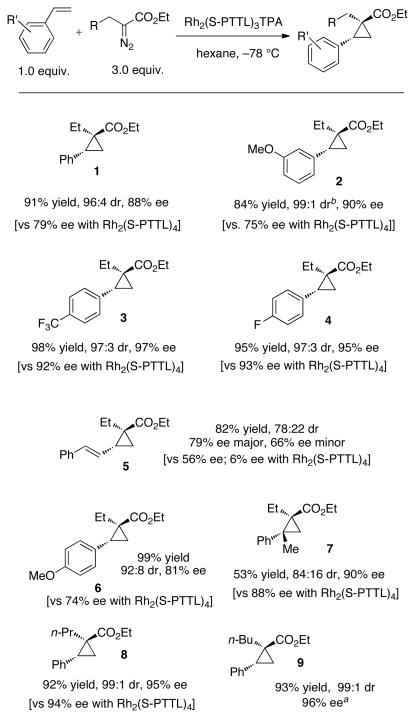

To determine if Rh2(S-PTTL)3TPA could also improve the selectivity for other cyclopropanation reactions, we surveyed a range of substrates as shown in Scheme 1. In addition to cyclopropane 1, significant improvements in enantioselectivity were observed in the cases of cyclopropanation products 2–6 when Rh2(S-PTTL)3TPA was used instead of Rh2(S-PTTL)4. Slight enantioselectivity improvements were also noted for 7 and 8, and results comparable to Rh2(S-PTTL)4 were observed in the case of cyclopropanation product 9. In general, yields and diastereoselectivities were comparable for the reactions studied. A notable exception was 3-methoxystyrene, where the diastereoselectivity to form 2 increased from 83:17 with Rh2(S-PTTL)4 to 99:1 with Rh2(S-PTTL)3TPA.

Scheme 1.

Rh2(S-PTTL)3TPA catalyzed cyclopropanation of styrene derivatives with α-alkyl diazoesters

a The enantioselectivity with Rh2(S-PTTL)4 was the same as that observed for Rh2(S-PTTL)3TPA. b The dr with Rh2(S-PTTL)4 was only 83:17

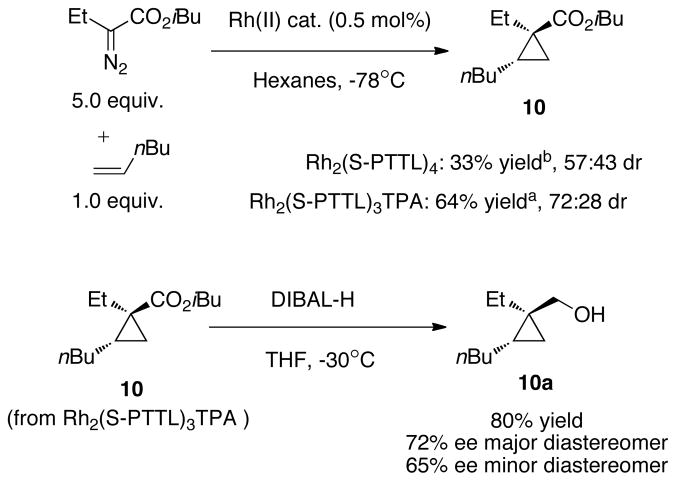

In prior studies on intermolecular cyclopropanation with α-alkyl-α-diazoesters, it was noted that α-olefins are particularly challenging substrates. The reaction between 1-octene and ethyl α-diazobutanoate did not yield cyclopropane products with Rh2TPA4, a catalyst that is effective in cyclopropanation reactions of α-alkyl-α-diazoesters with styrenes or vinyl ethers.20 Very recently, Hashimoto reported the cyclopropanation of diazopropionate with 1-hexene.18 Still unknown, however, is α-olefin cyclopropanation by α-n-alkyl-α-diazocarbonyl compounds, which contain weaker β-C-H bonds. As shown in Scheme 3, the reaction between 1-hexene and isobutyl α-diazobutanoate (5 equiv.) is successful with with Rh2(S-PTTL)4, but gives cyclopropane 10 in only 33% yield. With Rh2(S-PTTL)3TPA, cyclopropane 10 can be obtained in a more useful 64% yield, albeit with modest dr (72:28) and enantiomeric excess (72% ee and 65% ee for the major and minor diasteroemers, determined by reduction to 10a). This represents the first example of an α-olefin cyclopropanation with an α-n-alkyl-α-diazocarbonyl compound that is selective over β-hydride elimination. We previously reported a method to access cyclopropenation products of α-alkyl-α-diazoesters using low reaction temeperatures and Rh2Piv4 as a catalyst.20 Very recently, Hashimoto reported an elegant method for enantioselective cyclopropenation using α-alkyl-α-diazoesters.4 Despite these advances, considerable challenges remain. Silylacetylenes had not proven effective substrates for cyclopropenation reactions with α-alkyl-α-diazoesters. Avoiding β-elimination in cyclopropenation of aliphatic alkynes had also been limited to α-methyl-α-diazocarbonyls, which possess strong bonds to β-hydrogens.22 Unknown were cyclopropenation reactions between aliphatic alkynes and diazo compounds with weaker β-C-H bonds. Previously, we reported that the scope of cyclopropenation could be extended to α-n-alkyl-α-diazoesters by using Rh2Piv4 at low temperature.21 These conditions were successful with aromatic alkynes and enynes. However, cyclopropenation products were not observed with 1-hexyne.

Scheme 3.

Diastereoselective Rh2(S-PTTL)3TPA catalyzed cyclopropanation of 1-hexene. a) Isolated yield. b) Yield by 1H NMR

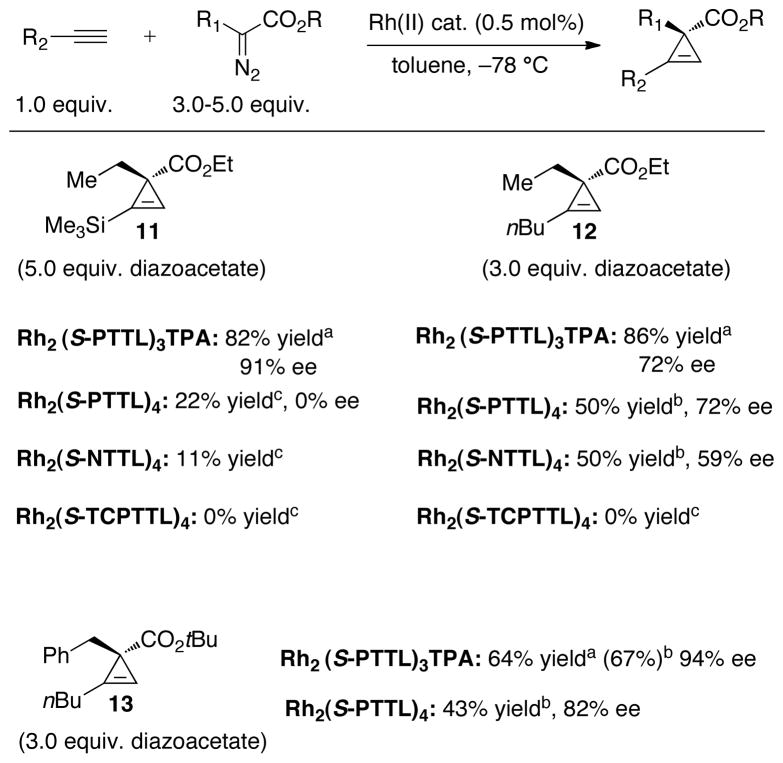

As shown in Scheme 4, Rh2(S-PTTL)3TPA successfully catalyzes the reactions of α-n-alkyl-α-diazoesters with trimethylsilylacetylene and 1-hexyne. Compared to other catalysts that were surveyed, Rh2(S-PTTL)3TPA was superior both in terms of yield and in terms of enantioselectivity. Products of β-elimination dominated the reactions with Rh2(S-PTTL)4, Rh2(S-NTTL)4 and Rh2(S-TCPTTL)4. With Rh2(S-PTTL)3TPA, cyclopropenation product 11 was produced from ethyl α-diazobutanoate and trimethylsilylacetylene in 82% yield and 91% ee. For Rh2(S-PTTL)4, the next best catalyst, the yield (22%) and enantioselectivity (racemic) were sharply reduced. Similar trends in yield were noted in the cyclopropenation reactions of 1-hexyne to form 12 and 13, with comparable enantioselectivity to Rh2(S-PTTL)4 being noted in Rh2(S-PTTL)3TPA-catalyzed formation of 12 and superior enantioselectivity to Rh2(S-PTTL)4 being noted in Rh2(S-PTTL)3TPA-catalyzed formation of 13.

Scheme 4.

Enantioselective cyclopropenation of aliphatic alkynes 1-hexene and trimethylsilylacetylene. Rh2(S-TCPTTL)4= dirhodium(II) tetrakis[N-tetrachlorophthaloyl-(S)-tert-leucinate]; a) Isolated yield. b) Yield by 1H NMR. c) Yield by GC.

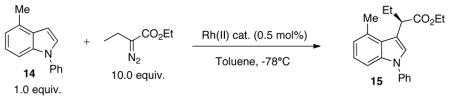

We recently described a Rh2(S-NTTL)4 catalyzed method for enantioselective C-H functionalization of indoles.5 Hashimoto and coworkers described the use of dirhodium(II) tetrakis[N-phthaloyl-(S)-triethylalaninate [Rh2(S-PTTEA)4] to be useful in the C-H functionalization of indoles by α-diazopropionates.23 Despite a good scope of reactivity, a number of substrate types have thus far proven problematic, including 4-substituted indoles, which have a nucleus prevalent in biologically active natural products. To date, only Hashimoto has achieved the enantioselective C-H functionalization of a 4-substituted indole: the Rh2(S-PTTEA)4 catalyzed reaction of N-methoxymethyl-4-methylindole with 2,4-dimethyl-3-pentyl-α-diazopropionate in 69% ee.

As shown in Table 2, 4-methyl-N-phenylindole 14 reacts poorly with excess ethyl α-diazobutanoate under Rh2(S-NTTL)4 catalyzed conditions, leading to product 15 in only 5% yield and 40% ee (Table 2). With an excess of ethyl α-diazobutanoate, Rh2(S-PTTL)3TPA gave 15 in superior yield (79%) and enantioselectivity (81% ee) relative to Rh2(S-PTTL)4 and Rh2(S-NTTL)4.

Table 2.

C-H functionalization of 4-substituted indoles.

Isolated yields.

Measured by chiral HPLC

Conclusions

In summary, we have described a mixed ligand catalyst, Rh2(S-PTTL)3TPA, which displays all of the N–phthalimide groups on one face in structural similarity to the chiral crown complex Rh2(S-PTTL)4. Rh2(S-PTTL)3TPA engages substrate classes (aliphatic alkynes, silylacetylenes, α-olefins) that are especially challenging in intermolecular reactions of α-alkyl-α-diazoesters, and catalyzes enantioselective cyclopropanation, cyclopropenation, and indole C-H functionalization with yields and enantioselectivities that are comparable or superior to Rh2(S-PTTL)4. The use of mixed ligand catalysts offers new opportunities for the optimization of catalytic processes that are catalyzed by bimetallic paddlewheel complexes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH Grant Number GM068640. Spectra were obtained with instrumentation supported by NSF CRIF:MU grants: CHE 0840401 and CHE-0541775.

Footnotes

Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) available: Experimental and computational procedures, cif files and full characterization details are provided. See DOI: 10.1039/b000000x/

Notes and references

- 1.For earlier examples of Rh(II) catalyzed reactions utilizing N-phthalimide ligands, see: Minami K, Saito H, Tsutsui H, Nambu H, Anada M, Hashimoto S. Adv Synth Catal. 2005;347:1483.Tsutsui H, Yamaguchi Y, Kitagaki S, Nakamura S, Anada M, Hashimoto S. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2003;14:817.Saito H, Oishi H, Kitagaki S, Nakamura S, Anada M, Hashimoto S. Org Lett. 2002;4:3887. doi: 10.1021/ol0267127.Shimada N, Anada M, Nakamura S, Nambu H, Tsutsui H, Hashimoto S. Org Lett. 2008;10:3603. doi: 10.1021/ol8013733.Tsutsui H, Shimada N, Abe T, Anada M, Nakajima M, Nakamura S, Nambu H, Hashimoto S. Adv Synth Catal. 2007;349:521.Anada M, Tanaka M, Washio T, Yamawaki M, Abe T, Hashimoto S. Org Lett. 2007;9:4559. doi: 10.1021/ol702019b.Yamawaki M, Tsutsui H, Kitagaki S, Anada M, Hashimoto S. Tetrahedron Lett. 2002;43:9561.Kitagaki S, Yanamoto Y, Tsutsui H, Anada M, Nakajima M, Hashimoto S. Tetrahedron Lett. 2001;42:6361.Denton JR, Cheng K, Davies HML. Chem Commun. 2008:1238. doi: 10.1039/b719175h.Reddy RP, Davies HML. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:10312. doi: 10.1021/ja072936e.Reddy RP, Davies HML. Org Lett. 2006;8:5013. doi: 10.1021/ol061742l.Reddy RP, Lee GH, Davies HML. Org Lett. 2006;8:3437. doi: 10.1021/ol060893l.

- 2.Watanabe N, Ogawa T, Ohtake Y, Ikegami S, Hashimoto S. Synlett. 1996:85. [Google Scholar]

- 3.DeAngelis A, Dmitrenko O, Yap GPA, Fox JM. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:7230. doi: 10.1021/ja9026852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goto T, Takeda K, Shimada N, Nambu H, Anada M, Shiro M, Ando K, Hashimoto S. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2011;50:6803–6808. doi: 10.1002/anie.201101905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DeAngelis A, Shurtleff VW, Dmitrenko O, Fox JM. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:1650. doi: 10.1021/ja1093309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pelphrey P, Hansen J, Davies HML. Chem Sci. 2010;1:254. [Google Scholar]; Nadeau E, Ventura DL, Brekan JA, Davies HML. J Org Chem. 2010;75:1927. doi: 10.1021/jo902644f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lindsay VNG, Lin W, Charette AB. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:16383. doi: 10.1021/ja9044955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Lindsay VNG, Nicolas C, Charette AB. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:8972. doi: 10.1021/ja201237j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lian Y, Miller LC, Born S, Sarpong R, Davies HML. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:12422. doi: 10.1021/ja103916t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Shimada N, Hanari T, Kurosaki Y, Takeda K, Anada M, Nambu H, Shiro M, Hashimoto S. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:8972–8981. [Google Scholar]

- 9.For discussion of conformations in chiral Rh paddlewheel complexes, see: Hansen J, Davies HML. Coord Chem Rev. 2008;252:5. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.08.019.Qin C, Boyarskikh V, Hansen JH, Hardcastle KI, Musaev DG, Davies HML. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:19198. doi: 10.1021/ja2074104.

- 10.DeAngelis A, Boruta DT, Lubin JB, Plampin JN, III, Yap GPA, Fox JM. Chem Commun. 2010;46:4541–4543. doi: 10.1039/c001557a.For more recent observations of the chiral crown complex in Cu-complexes, see: Reger DL, Horger JJ, Debreczeni A, Smith MD. Inorg Chem. 2011;50:10225. doi: 10.1021/ic201238n.Reger DL, Horger JJ, Smith MD. Chem Commun. 2011;47:2805. doi: 10.1039/c0cc04797j.

- 11.Ghanem A, Gardiner MG, Williamson RM, Müller P. Chem Eur J. 2010;16:3291. doi: 10.1002/chem.200903231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Doyle MP, McKervey MA, Ye T. Modern Catalytic Methods for Organic Synthesis with Diazo Compounds. John Wiley; NewYork: 1998. [Google Scholar]; Doyle MP, Ren T. In: In Progress in Inorganic Chemistry. Karlin KA, editor. Vol. 49. Wiley; New York: 2001. pp. 113–168. [Google Scholar]; Davies HML, Walji AM. In: In Modern Rhodium-Catalyzed Organic Reactions. Evans PA, editor. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim, Germany: 2005. pp. 301–340. [Google Scholar]; Taber DF, Joshi PV. In: In Modern Rhodium-Catalyzed Organic Reactions. Evans PA, editor. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim: 2005. p. 357. [Google Scholar]; Doyle MP. Chem Rev. 1986;86:919. [Google Scholar]; Doyle MP. Top Organomet Chem. 2004;13:203. [Google Scholar]; Davies HML, Beckwith RE. J Chem Rev. 2003;103:2861. doi: 10.1021/cr0200217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Müller P, Fruit C. Chem Rev. 2003;103:2905. doi: 10.1021/cr020043t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Doyle MP, Duffy R, Ratnikov M, Zhou L. Chem Rev. 2010;110:704. doi: 10.1021/cr900239n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Zhang Z, Wang J. Tetrahedron. 2008;64:6577. [Google Scholar]; Lu HJ, Zhang XP. Chem Soc Rev. 2011;40:1899. doi: 10.1039/c0cs00070a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Padwa A, Austin DJ. Angew Chem, Int Ed Engl. 1994;33:1797. [Google Scholar]; Merlic CA, Zechman AL. Synthesis. 2003;8:1137. [Google Scholar]; Espino CG, Fiori KW, Kim M, Du Bois J. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:15378. doi: 10.1021/ja0446294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Pirrung MC, Morehead TA., Jr J Am Chem Soc. 1994;116:8991. [Google Scholar]; Thornton AR, Blakey SB. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:5020. doi: 10.1021/ja7111788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Stoll AH, Blakey SB. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:2108. doi: 10.1021/ja908538t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Stokes BJ, Liu S, Driver TG. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:4702. doi: 10.1021/ja111060q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Chuprakov S, Kwok SW, Zhang L, Lercher L, Fokin VV. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:18034. doi: 10.1021/ja908075u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Corey EJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:8916. doi: 10.1021/ja047064k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Doyle MP, Yan M, Gau HM, Blossey EC. Org Lett. 2003;5:561–563. doi: 10.1021/ol027475a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Lou Y, Horikawa M, Kloster RA, Hawryluk NA, Takeda K, Oohara T, Anada M, Nambu H, Hashimoto S. Angew Chem, Int Ed Engl. 2010;49:6979–6983. doi: 10.1002/anie.201003730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Charette AB. personal communication.

- 15.A structurally and energetically similar (ΔE +0.5 kcal/mol) structure to the one displayed in Fig 1c was found as a result of the combined molecular dynamics/DFT search. The primary difference between the structures is the rotational phase of the TPA ligand. The coordinates are provided in the Supplementary Information.

- 16.Kolossvary I, Guida WC. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:5011. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Similarly, a clockwise twist of a S-PTTL ligand had been observed previously in one crystal structure of Rh2(S–PTTL)4. In this case, a C-H pi interaction is observed in the crystal structure. See reference 10.

- 18.Goto T, Takeda K, Anada M, Ando K, Hashimoto S. Tetrahedron Lett. 2011;52:4200–4203. [Google Scholar]

- 19.The cyclopropanation of styrene with t-butyl-α-diazobutanoate (3 equiv) was also studied. In a reaction catalyzed with Rh2(S-PTTL)3(TPA), the cyclopropane was obtained in 54% ee and 96:4 dr. Using Rh2(S-PTTL)4, the cyclopropane was formed in 28% ee and 88:12 dr. The yield was low (~30%) in both reactions.

- 20.Panne P, DeAngelis Andrew, Fox JM. Org Lett. 2008;10:2987. doi: 10.1021/ol800983y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Panne P, Fox JM. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:22. doi: 10.1021/ja0660195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.For diazoketones: Padwa A, Kassir JM, Xu SL, Simon L. J Org Chem. 1997;62:1642.Padwa A, Kassir JM, Xu SL. J Org Chem. 1991;56:6971–6972.For diazoesters: Müller P, Gränicher C. Helv Chim Acta. 1995;78:129.Tarwade V, Liu X, Yan N, Fox JM. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:5382. doi: 10.1021/ja900949n.For TMS-acetylene with α-diazobutyrolactone: Sattely ES, Meek SJ, Malcolmson SJ, Hoveyda AH, Schrock RR. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:943. doi: 10.1021/ja8084934.

- 23.Goto T, Natori Y, Takeda K, Nambu H, Hashimoto S. Tetrahedron Asymmetry. 2011;22:907. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.