Abstract

We have performed a meta-analysis of the major-histocompatibility-complex (MHC) region in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) to determine the association with both SNPs and classical human-leukocyte-antigen (HLA) alleles. More specifically, we combined results from six studies and well-known out-of-study control data sets, providing us with 3,701 independent SLE cases and 12,110 independent controls of European ancestry. This study used genotypes for 7,199 SNPs within the MHC region and for classical HLA alleles (typed and imputed). Our results from conditional analysis and model choice with the use of the Bayesian information criterion show that the best model for SLE association includes both classical loci (HLA-DRB1∗03:01, HLA-DRB1∗08:01, and HLA-DQA1∗01:02) and two SNPs, rs8192591 (in class III and upstream of NOTCH4) and rs2246618 (MICB in class I). Our approach was to perform a stepwise search from multiple baseline models deduced from a priori evidence on HLA-DRB1 lupus-associated alleles, a stepwise regression on SNPs alone, and a stepwise regression on HLA alleles. With this approach, we were able to identify a model that was an overwhelmingly better fit to the data than one identified by simple stepwise regression either on SNPs alone (Bayes factor [BF] > 50) or on classical HLA alleles alone (BF > 1,000).

Introduction

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE [MIM 152700]) is one of the many complex diseases that are still without an adequate explanation for the known heritability (>66% in the case of SLE1). Delineating the genetic contribution to the risk of developing a complex disease, such as SLE, is complicated by the likelihood that disease is caused by multiple genes. In this paper, we concentrate on one region, the extended major histocompatibility complex (MHC) (Chr6: 26–34 Mb), which is known to be the most polymorphic region in the genome. The MHC can be divided into three regions, termed classes I, II, and III. Classical class I and II loci encode the human leukocyte antigen (HLA) proteins involved in antigen presentation to T cells. The class III region contains the greatest density of genes in the human genome and includes many with immune function, such as genes involved in the complement system and the TNF gene cluster. The MHC class II region is the densest area of the genome for disease associations,2 and the MHC confers the greatest genetic risk for SLE in all populations studied by genome-wide association studies thus far3,4

Understanding the genetic risk of this region is therefore critical for defining the genetic predisposition to SLE. However, this region is complex because there is linkage disequilibrium (LD) spanning the entire extended MHC, which makes determining the true causal loci very difficult. There is strong evidence for association at the class II locus HLA-DRB1 (MIM 142857), in which alleles HLA-DRB1∗03:01 and HLA-DRB1∗15:01 are consistently replicated.5–7 There have also been associations with other alleles such as HLA-DRB1∗08:018 and HLA-DRB1∗14:01.7 However, because of strong LD in the class II region (HLA-DR and HLA-DQ), HLA-DRB1 alleles are correlated with alleles of the class II loci HLA-DQA1 (MIM 146880) and HLA-DQB1 (MIM 604305). Therefore, alleles outside of HLA-DRB1 have often shown evidence of association with SLE, but this might be due to the LD arising from extended haplotypes. In northern Europeans, there are two main extended SLE-associated MHC haplotypes that contain the class II alleles HLA-DRB1∗03:01 and HLA-DRB1∗15:01;5 these extended haplotypes comprise the following HLA alleles: HLA-A∗03:01 – HLA-B∗07:02 – HLA-C∗07:02 – HLA-DRB1∗15:01 – HLA-DQA1∗01:02 – HLA-DQB1∗06:02 and HLA-A∗01:01 – HLA-B∗08:01 – HLA-C∗07:01 – HLA-DRB1∗03:01 – HLA-DQA1∗05:01 – HLA-DQB1∗02:01. Associated signals independent of HLA-DRB1 have been detected, but there is no consensus on where these associations lie or how many there are. In fact, it is still not clear whether the genetic risk for SLE lies in HLA alleles alone or whether other genes outside of classical HLA loci are affecting disease risk.

Several studies have analyzed genetic variation within the MHC region with the aim of identifying multiple loci independently associated with SLE.5–7 Strictly speaking, this is statistical independence; locus A disease associations that cannot be explained by the correlation between locus A and locus B. This does not necessarily mean that the two associated loci are biologically independent (given that they might both act on the same pathway). However, because of the complexity of the region, extended regions of LD, and a lack of statistical power, the disease-causing alleles within the MHC have not yet been identified. A larger study of the MHC in SLE is needed for refining previously identified signals and for searching for additional disease-associated loci, and this will require methods designed to better account for extensive LD in associated regions. This paper reports on the largest study to date of SLE association at the MHC in the search for statistically independent associated loci.

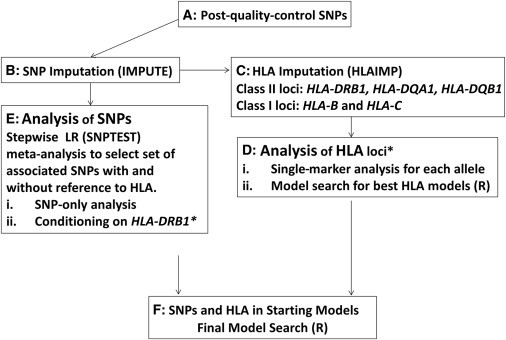

It is common for association studies of the MHC to look for independent signals by conditioning on the strongest signal by using either HLA alleles or a SNP as a covariate in logistic regression. What follows is a stepwise regression where each successive associated marker is used as an additional covariate. This approach relies heavily on the first locus taken as a covariate and can lead to a suboptimal final model of association if the first signal tags two or more associations.9 We propose to start the stepwise search from multiple starting points determined from both a priori evidence about association and analyses of subsets of the data: SNPs only, HLA alleles only, and separate HLA classes. Our study therefore takes a broader approach than simply conditioning on the most significant associated signal in the search for the best model of association within the MHC. A flowchart of the approach we took can be seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

A Flowchart of the Work Flow for This Study

The asterisk (∗) represents information carried from the HLA-DRB1 analysis to the SNP analysis conditional on HLA-DRB1 alleles. The following abbreviation is used: LR, logistic regression.

For this study, we obtained data from six sources (Table 1), as well as additional well-defined control data (from the Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium 2 [WTCCC2]12 and the National Institute of Mental Health [NIMH] [see Web Resources]) and performed a meta-analysis within the MHC region (Chr6: 26–34 Mb, NCBI build 126) by using an imputation strategy to maximize the number of markers across all studies. This large study provided us with a total of 3,701 independent cases and 12,110 control individuals of European ancestry and genotypes for 7,199 SNPs in the MHC region after imputation. We had complete HLA-DRB1 typing for one of the studies; for the other studies, we used imputation of HLA-DRB1 alleles from SNP genotypes (see Material and Methods). Imputation was also performed on HLA-B (MIM 142830), HLA-C (MIM 142840), HLA-DQA1, and HLA-DQB1. We also had limited typing for HLA-DRB1, HLA-B, HLA-DQA1, and HLA-DQB1 in one of the studies. With the complete HLA-DRB1 typing, we were able to use these data to evaluate the quality of imputation. Although we were not able to evaluate the accuracy of HLA-C imputation, the results from the original study13 by the authors of the imputation program we used show that this locus has an accuracy superior to that of HLA-B in Europeans (this latter locus performed well in our study).

Table 1.

Summary of Individual Studies

| Study | Genome-wide Markers | MHC SNPsa | Cases | Controls | External Controls | Population Summary |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina 550K3 | Illumina 317K | 2,380 | 1,137 | 6,529 | 3,493 from WTCCC2 | European: mixture of UK, Italian, Spanish, and North American |

| Illumina 317K4 | Illumina 317K | 1,522 | 413 | 1,927 | 1,300 from WTCCC2 | European: mixture of UK and North American |

| Affy500K10 | selected 14Kb | 1,468 | 210 | 1,707 | 1,707 from NIMH | European: mixture of UK and North American |

| Illumina MHC Panel7 | 384 continental AIMsc | 2,360 | 917 | 553d | N/A | European: mixture of UK and North American |

| Illumina Custom6 | genomic control SNPse | 1,230 | 686 | 773 | N/A | European: mixture of UK and North American |

| Affy100K11 | selected 7Kb | 227 | 338 | 621 | N/A | European: mixture of Swedish and Argentinian |

The genome-wide inflation factor for each study (see Material and Methods) is as follows: 1.140 for Illumina 550K, 1.092 for Illumina 317K, 1.000 for Affy500K, 1.000 for Illumina Custom, and 1.094 for Affy100K. For the Illumina MHC Panel study, we found no significant difference between the matched and unmatched cases for the variable used as the estimation of percent northern European ancestry (rank sum test, p = 0.22). The following abbreviations are used: MHC, major histocompatibility complex; WTCCC2, Welcome Trust Case Control Consortium 2; NIMH, National Institute of Mental Health; AIMs, ancestry informative markers; and N/A, not available.

Chr6: 26,000–34,000 kb.

Selected from Affy-Illumina overlap, excluding regions of high LD and SNPs in LD with each other (all R2 < 0.25).

See original paper7 for description of selected markers (AIMs).

The Illumina MHC Panel study contained individuals from a previous trio study,7 in which controls genotypes were taken from nontransmitted alleles. See Table S1 for a breakdown of the origin of recruitment.

Genomic control SNPs included in the Illumina Custom panel.

These data gave us the opportunity to determine whether the association signals within the MHC are primarily due to classical HLA alleles, to only SNPs, or to a combination of HLA alleles and other effects independent of these alleles.

Material and Methods

Ethical Approval

This study was approved by the London Research Ethics Committee, United Kingdom (ref: 06/MRE02/9). All meta-studies were previously published.

Study Cohorts and Genotyping

Our analysis incorporated data from six studies. Table S1, available online, displays the original sample sizes for each study and the sample sizes for this meta-analysis after reassignment of overlapping individuals. Any subjects who were observed in more than one study were assigned to a single group on the basis of a variety of considerations, including density of genotype data and case-control balance. Table 1 includes details of the genotyping platforms used for each study and information on genome-wide markers available for ancestry and relatedness analyses. The Illumina MHC Panel study contained individuals from a previous trio-family study,7 in which controls genotypes were taken from nontransmitted alleles. For all other studies, cases and controls were independent. We also used genotype data from the WTCCC212 and the NIMH.

Four-digit HLA-DRB1 data were available for 2,075 individuals: 605 cases from the UK arm of the Illumina Custom study6 and 1,470 individuals (917 cases and 553 nontransmitted-allele controls) from the Illumina MHC Panel study.7 Details on the HLA-DRB1 typing can be found in the original study publications.6,7

Four-digit HLA-B, HLA-DQA1, and HLA-DQB1 data were available for 326, 340, and 341 cases, respectively, from the UK arm of the Illumina Custom study (four-digit typing for these genes was performed at the Anthony Nolan Trust, London, UK with Luminex One Lambda SSO methodology).

Quality Control

A set of common quality-control filters was applied to each parent study before they were merged for analysis. Subjects and SNPs with <90% genotyping were removed, and a lower bound for minor allele frequency (MAF) was set to 1%. The 90% rate was selected from a plot of percentage data removed against missing rate; moving to 95% across studies would have increased the amount of data removed from <3% to 9%. Differential missingness (between cases and controls) was checked in each study separately with a threshold set at 10−5; for SNPs reported in this paper, over all studies, the range of p values for this test was 0.02–1.00. SNPs were removed by study source for Hardy-Weinberg disequilibrium with the use of the false-discovery-rate (FDR)14 procedure with a rate of 0.05. We removed 55 subjects (one from Illumina 500K, two from Illumina 317K, 14 from Affymetrix 100K, and 38 from the Illumina MHC Panel) from all studies as a result of low genotyping (<90%). Over all studies, 185 SNPs were rejected because of departure from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) according to the FDR (≤ 0.05) procedure. Similarly, 186 SNPs were rejected after quantile-quantile plots were looked at, and 138 were rejected after a study-wide rejection level of p < 0.0001 was set.

In order to identify unknown duplicates and first-degree relatives where feasible, we performed identity-by-descent (IBD) analysis by using PLINK15 on subsets of cases and controls with potential overlap. For this we used the same 300K, 14K, and 7K genome-wide marker sets as described below for the principal-component analysis (PCA). In order to confirm that the 14K and 7K marker sets were sufficient for this purpose, we performed IBD analysis by using the 300K, 14K, and 7K marker sets on a common set of subjects with known duplicates and first-degree relatives. Pi_hat, measuring the degree of IBD sharing, was similar for all three marker sets, and a cutoff of 0.3 was appropriate throughout for the detection of first-degree relatives. One subject (the one with the least amount of missing data) from each related pair (pi_hat > 0.3) or set was retained; for duplicate individuals, genotypes were merged by consensus call in PLINK.

We removed 203 subjects because of relatedness (IBD > 0.3): these were five subjects from the NIMH, 59 from the WTCCC2 (four were removed because of relatedness between the 1958 birth cohort [1958BC] and the National Blood Service [NBS], seven were removed from within the 1958BC only, and 48 were removed from the NBS only), and 139 first-degree relatives dropped on the basis of IBD or relatedness in other studies (89 from Illumina 317K, 39 from the Illumina MHC Panel, and 11 from Illumina Custom).

Population Substructure

We analyzed population substructure by using PCA in EIGENSTRAT16 to identify outliers by ancestry and to adjust for intra-European ancestry in the association analyses. Because the whole-genome data available were different for each study, we performed the following series of analyses.

First, for outlier identification (i.e., likely non-European ancestry), a series of PCAs using EIGENSTRAT16 was performed with each type of available whole-genome data (300K, 14K, and 7K). Outliers were removed with sigma > 6 for any of the first five principal components (PCs) in any of these analyses. For the Illumina MHC Panel subjects, for whom we only had 384 intercontinental ancestry informative marker data, a previous STRUCTURE analysis7 was used for identifying and removing subjects with <90% European ancestry.

We removed 58 individuals (12 from Illumina 500K, 21 from Illumina 317K, 10 from NIMH, and 15 from WTCCC2) from all studies after PCA to identify outliers. Table S2 shows the marker sets, subjects included, and number of outliers identified from each PCA from each data set. A subset of subjects with known common four-grandparent origins within the Illumina 550K data set enabled us to interpret these initial PCAs. Figure S1 shows a representative set of these PCAs.

For association analysis, we re-ran PCA by using only subjects allocated to each of the final six groups (after allocation of overlapping subjects and external controls), except for the Illumina MHC Panel, for which we used a previous estimation of percent northern European ancestry (with STRUCTURE17). Consistently, the first PC represented by far the most variance—from observation of scree plots—and corresponded to a northwest-southeast European gradient.

The first PC from each PCA (or percent northern European ancestry for the Illumina MHC Panel) was included as a covariate in the logistic regressions for adjusting for intra-European ancestry. The PC was included in all analyses of SNP and HLA data.

We calculated an inflation factor for each of the four genome-wide studies by running a case-control analysis with the PCA. This resulted in the following inflation factors: 1.175 for Illumina 550K, 1.166 for Illumina 317K, 1.000 for Affy500K, and 1.082 for Affy100K. When the first PC was added in, the inflation factors were as follows: 1.140 for Illumina 550K, 1.092 for Illumina 317K, 1.000 for Affy500K, and 1.094 for Affy100K. For the Illumina Custom study, an analysis of a subset (458 cases and 382 controls, who were typed on the Illumina omni1-quad as part of another study18) of the data used in this paper gave an inflation factor of 1.000; the inflation factor for all individuals with the use of only the genomic control SNPs (54 SNPs) on the custom chip was 1.209. The Illumina MHC Panel study was well matched because all the controls were made up of nontransmitted alleles from 553 of the cases; the remaining 364 cases were not found to be significantly different from the matched cases for the variable used as estimation of percent northern European ancestry (rank sum test, p = 0.22).

SNP Imputation

The genotypes for this meta-analysis were obtained from six different platforms, and, with the exception of the Illumina 317K and 550K platforms, the percentage of overlap was not high. For example, there are only 737 SNPs common to the Illumina 550K (2,380 MHC SNPs) and the Illumina MHC Panel (2,360), and there are only 161 SNPs common to the Illumina 317K (1,522) and Affy500K (1,118) MHC regions. Therefore, in order to combine association results for as many studies as possible for each SNP, we used an imputation strategy by using IMPUTE;19 each study was imputed up to the density of the WTCCC2 controls (typed on the Illumina 1.2M chip and Affy v.6.0 chip), which were used as a reference set (4,793 individuals with 7,119 markers in the MHC). These controls were also used as control genotypes in the Illumina 550K study (n = 3,493) and the Illumina 317K study (n = 1,300). Howie et al.19 have shown that using genotypes both as a reference data set and subsequently as controls in an association analysis does not lead to inflated levels of false discovery.

We did not make use of additional imputation reference data (1000 Genomes, HapMap) because the fact that the WTCCC2 control data were of a much higher density than any of the individual studies could lead to an imbalance in imputation accuracy between cases and controls; some difficult-to-impute SNPs would be more accurately imputed in the WTCCC2 control data than in the cases, and so this could lead to differences in frequencies. Because the WTCCC2 data are of higher density, some SNPs (in 1000 Genomes) might have little information in the study data (low density around the SNP position) but have good information in the WTCCC2 data. The study data would then have imputed SNPs with frequencies tending toward the reference data (1000 Genomes), whereas the WTCCC2 data would have well-imputed SNPs with frequencies more representative of the true genotypes.

The density of SNPs in cases and controls (per study) prior to imputation was forced to be equivalent (i.e., a SNP that was present in the cases, but not in controls, or vice versa, was removed). This guarded against the possibility of spurious association arising as a result of an imbalance of imputation accuracy between cases and controls. This also gave us an extra test of our imputation because we were able to evaluate the accuracy at these known but removed genotypes. The results from this comparison, displayed in Table S3B, also performed well (average accuracy > 0.94) and were consistent with the quality measures output by IMPUTE19 in Table S3A.

Measures of imputation performance in each study can be seen in Tables S3, S5, and S6. For all imputed SNPs (Table S3A), the average certainty across studies was high (>0.88), and this is supported by the consistently high scores in the cross-validation analyses (concordance and R2 > 0.87). The average information was also high (>0.82), except for the Affy100K (0.64), which had relatively sparse genotyping overall, and the Illumina MHC Panel (0.76), which had no genotype data within much of the extended class I region.

The imputation evaluation specific to our most associated SNPs (conditional and unconditional on HLA alleles) showed a high degree of accuracy (>0.9) and certainty (>0.9 for all except on the Affy100K [>0.7]). The information statistics were lower for the Affy100K study (0.4 < info < 0.8) than for the others (all > 0.7) as a result of the lower density of genotyping in this study, but removing this study from the analysis did not alter the results. The HWE figures in controls were satisfactory (there were no significant p values after adjustment for testing eight SNPs in six studies).

HLA Imputation

We imputed HLA-B, HLA-C, HLA-DRB1, HLA-DQA1, and HLA-DQB1 by using HLA∗IMP13,20 in all the studies. We made use of the desktop application that comes with this program for quality control, alignment, and phasing. The imputation was then performed online with the browser application. We took the full set of post-SNP-imputation SNPs (n = 7,122) as potential predictive variables, but we removed genotypes if the maximum imputation probability was less than 0.95 and then removed potential SNPs if they had more than 10% missingness. The final set of SNPs used for HLA imputation (usually ∼40) is chosen by HLA∗IMP internally. The SNPs used for HLA imputation at each locus are displayed in Tables S7A–S7E. Some of these SNPs were typed, and some were imputed, so we checked the SNP-imputation scores (“INFO” from IMPUTE) for these SNPs; these are displayed in Tables S7A–S7E for each study. The range of INFO scores was very high for Illumina 500K, Illumina 317K, Affy500K, the MHC Panel, and Illumina Custom (it was 0.704–1.000 over all HLA genes), whereas for the Affy100K study, the range was generally a little lower (0.654–1.000 over all HLA genes). Although the lower point of the ranges was around 0.7 for many loci, the majority of SNPs actually had imputation scores > 0.9.

We had four-digit typing for HLA-DRB1 for the Illumina MHC Panel study for 917 cases and 553 nontransmitted-allele controls, and we had four-digit typing for HLA-DRB1 for the Illumina Custom study for 605 cases. We also had four-digit HLA-B, HLA-DQA1, and HLA-DQB1 data available for 326, 340, and 341 cases, respectively, from the Illumina Custom study. We used these data for cross-validation; the imputed HLA data were compared to the typed data, and calculations were made for sensitivity, specificity, correlation squared (R2), frequencies, and accuracy (the number of correct assignments divided by the total [2 × n] alleles). Tables S10A–S10E contain data on this cross-validation for all HLA alleles. This was assessed on the most likely alleles (reported by HLA∗IMP) for each gene, and because the performance of this was very high, we used the most likely calls (as opposed to probabilistic data) in further statistical analysis for association. We also compared our imputation performance to that of a study of the MHC in rheumatoid arthritis (hereafter called the RA study).21 Our accuracy was very similar to that of the RA study, and the comparison can be seen in Table S8. We also note that the accuracy reported in the paper by the authors of HLA∗IMP20 agrees with our observed rates of >90%; our accuracy was higher, and this was predicted by the authors of HLA∗IMP given that they only used two-thirds of the reference data (because one-third was used for prediction). We also found, as did they, that HLA-DRB1 had slightly lower accuracy than did the other loci.

We were not able to evaluate the performance of HLA-C imputation. However, this locus was found to be more reliably imputed than was HLA-B in Europeans in the original study by the authors of HLA∗IMP.13 HLA∗IMP has a much larger reference data set than in the original paper, and so the imputation is most likely more accurate. From the accuracy reported in the HLA∗IMP13 paper, there is no reason to believe that the performance of HLA-C imputation is any worse than that of HLA-B, that is, HLA-C is probably more accurately imputed.

RNA-Expression Data

RNA-expression data were downloaded from the Gene Expression Omnibus repository (see Web Resources). These data arise from a study22 of 210 unrelated HapMap individuals, from whom RNA was extracted from lymphoblastoid cell lines. Genotype data for the 210 HapMap individuals were downloaded from the HapMap website.

Linear regression was performed in R on the RNA-expression data. Genotype was taken as the explanatory variable coded as minor allele dosage [0,1,2], and expression levels (log scale, base = 2) were the outcome. Each of the three SNPs (rs2246618, rs8192591, and rs2524117) that were associated with SLE independently of classical HLA alleles was tested for correlation with the expression levels of genes closest to the respective SNPs; rs8192591 was tested against expression for NOTCH4 (MIM 164951), the class I SNPs (rs2246618 and rs2524117) were both tested against HLA-B and HLA-C expression, and rs2246618 was also tested against MICB (MIM 602436) expression. Therefore, we adjusted for six tests in total.

Statistical Analysis: Overview

The SNP and HLA analysis was a multistep process from imputation to association and model selection. We therefore include a flow chart (Figure 1) to aid the reader, and we refer to this in each part of the results section.

Statistical Analysis: SNP Data Only

As a result of differences in the data available for ancestry adjustment, we were not able to simply pool the imputed studies’ data and analyze as a single group. Thus, we reanalyzed each study separately and then combined our results via standard meta-analysis methods (inverse variance method and test for heterogeneity of odds ratios [ORs]23).

Association testing was performed for each study with logistic regression (additive model), accounting for imputation uncertainty via the software SNPTEST.24 We accounted for ancestry by including the first PC, obtained from PCA using EIGENSTRAT with available genome-wide markers (see Supplemental Data) as a covariate. For the Illumina MHC Panel study, we used the percentage of European ancestry estimated in a previous study.7

After identifying the first top associated SNP (i.e., the SNP with the lowest p value from the combined meta-analysis), we used this SNP as a covariate in logistic regression. This conditional analysis then identified the next best associated SNP (which was used as a third covariate along with the first associated SNP and the ancestry covariate). We proceeded to identify as many associations as were statistically significant (FDR ≤ 0.05) and added each successive SNP as a covariate. Heterogeneity of ORs was tested for in the logistic-regression framework with best-guess genotypes in R.25

Statistical Analysis: SNP and HLA Data

We analyzed the HLA data in a logistic-regression model in which each allele was taken in turn and was coded as a biallelic marker (0, 1, or 2 copies of the allele), and we used the same PC for ancestry as we did with the SNP data. We estimated the OR for each study separately and then combined the results by using the inverse-variance method.23

Multiple testing was accounted for within each study by permutation (maxT) in PLINK; 100,000 permutations were taken. We combined the permuted p values across studies by using the sample-size method for meta-analysis.23 Alleles were taken as significantly associated if they had a combined adjusted p < 0.01. The number of permutations limited the strength of association to 10−5 within each study, but this only affected the most associated alleles, which were significant after the meta-analysis. This procedure therefore has a lower bound for the estimated p value because PLINK limits the p value to a minimum of [1 / nperms + 1] to avoid a p value of zero, but this is adequate for detecting an adjusted value of less than 0.01. This permutation adjustment was made for HLA-DRB1 alone within the HLA-DRB1 analysis. We also adjusted across all HLA loci for multiple testing when we included all the HLA data.

A stepwise model search with HLA alleles and SNPs was performed in R with the use of dosage values. For imputed genotypes, this is a function of genotype probabilities. We analyzed all studies together by using a covariate for study and by assuming random effects for the PC covariate; we did this to ensure a different effect size for each study (because each PCA was performed separately). The ORs were assumed to be equal for all studies, although we relaxed this assumption to test for heterogeneity (likelihood-ratio test of differing ORs against equal ORs). The Bayesian information criterion (BIC) was used as the variable-selection criterion in the stepwise regression.

We used forward and backward selection for the stepwise regression. When combining the HLA alleles and the SNPs, we began the search from a variety of starting positions: the null model (no variables), the best models for each of the HLA genes (HLA-B, HLA-C, HLA-DRB1, HLA-DQA1, and HLA-DQB1), each HLA class (class I alleles and class II alleles), individually significant HLA alleles, and the best overall HLA model. The aim of this search was to find the best set of SNPs and/or HLA alleles that are independently associated with SLE as judged by the lowest BIC. To avoid local minimum, it is a good idea to begin the search from as many starting positions as possible. Therefore, we also started the search from models similar to those that each stepwise search converged to by substituting markers with alternatives in high LD. One must also take care not to overfit by including multiple correlated explanatory variables, and so each model must be checked carefully; the observed correlation among variables should be checked, and the direction of effect for a particular explanatory variable should not change between when it is analyzed on its own and when it is conditional on other markers in the model. In our analysis, we included SNPs that were independent of HLA alleles and also SNPs that were correlated (SNPs that we identified as significant in SNP-only analysis); therefore, we also conducted the model search by including only HLA alleles and SNPs independent of HLA alleles.

We did not use SNPTEST for this stepwise search because SNPTEST does not perform stepwise regression. Using SNPTEST in the first stage was for the purpose of gaining the best set of SNPs given the imputation uncertainty. We did check that the results for the SNPs returned from SNPTEST analyses did not change (level of significance and p values) when we used the pooled approach.

We used PLINK to perform conditional haplotype analysis of all the studies’ data together by using a covariate for study and by assuming random effects for the PC covariate; we did this to ensure a different effect size for each study (because each PCA was performed separately). We ran the analysis separately for each of the alleles and SNPs (HLA-DRB1∗03:01, HLA-DRB1∗15:01, HLA-DQA1∗01:02, rs8192591, rs2246618, and rs2524117) conditional on haplotypes formed by the alleles on each of the extended HLA-DRB1∗0301 and extended HLA-DRB1∗15:01 haplotypes defined above.

Results

Association: SNPs

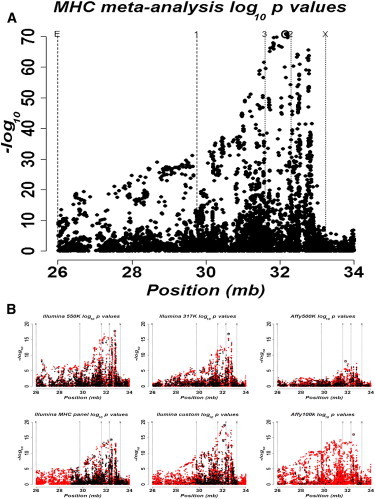

After we applied quality-control procedures and SNP imputation, the data contained 7,119 markers for 3,701 cases and 12,110 controls (see Table 1 for numbers of individuals per study and methods for full quality-control information). We first analyzed the SNPs as single markers by using logistic regression with a covariate to account for intra-European ancestry (see Material and Methods). This is step E-i in Figure 1. We used SNPTEST24 to account for imputation uncertainty, and we combined the results across studies by using the standard inverse-variance method.23 Figure 2 displays a plot of the p values (−log10 scale) for the meta-analysis, as well as plots for each contributing study. These plots demonstrate the consistency across studies and the relative contributions of each data source. The most significant SNP from this analysis was used as the first covariate in the stepwise logistic regression, again with SNPTEST, and results across studies were combined with the inverse-variance method.

Figure 2.

Association Results

(A) Meta-analysis results.

(B) Individual study data.

Black points indicate raw data, and red points indicate imputed data. Details on individual studies can be seen in Table 1, where sample sizes are the following: 1,137 cases and 6,529 controls for Illumina 550K, 413 cases and 1,927 controls for Illumina 317K, 210 cases and 1,707 controls for Affy500K, 1,012 cases and 613 controls for the Illumina MHC Panel, 686 cases and 776 controls for Illumina Custom, and 338 cases and 621 controls for Affy100K. In all plots, “E” is the lower bound for extended class I, “1” is the lower bound for class I, “3” is the lower bound for class III, “2” is the lower bound for class II, and “X” is the lower bound for extended class II. Circled SNPs show in which class the most associated SNP lies.

By setting the FDR at ≤ 0.05, we identified five SNPs with study-wide significance by using stepwise multiple logistic regression. The top SNP (rs1150753 [32,167,845 bp]; meta p value = 1.0 × 10−71) in the single-marker analysis was in a class III, intronic region of TNXB (MIM 600985) and had an estimated OR of 2.20 (95% confidence interval [CI] = 2.01–2.39). After we conditioned on this SNP, the next most significant marker (rs9271731 [32,701,590 bp]; meta p value = 1.3 × 10−29) was in the intergenic class II HLA-DRB1–HLA-DQA1 region and had an estimated OR of 1.58 (95% CI = 1.46–1.71). Further conditional analyses, using the two SNPs previously declared as associated as covariates, resulted in three additional associated SNPs: rs9378200 (class III; 31,680,906 bp; intergenic NCR3 [MIM 611550]–AIF1 [MIM 601833] region; p = 8.5 × 10−11; OR = 0.65 [95% CI = 0.57–0.74]), rs9469220 (class II; 32,766,288 bp; upstream of HLA-DQB1; p = 1.8 × 10−7; OR = 0.83 [95% CI = 0.78–0.89]), and rs9265604 (class I; 31,407,429 bp; intergenic HLA-B–HLA-C region; p = 1.0 × 10−6; OR = 0.83 [95% CI = 0.78–0.89]). The conditional p values above are unadjusted for multiple testing; however, they all passed a simple Bonferroni correction, which is highly conservative given the LD in this region.

Table 2 contains marginal and multivariate ORs and p values obtained from SNPTEST and PLINK on the five SNPs that obtained study-wide conditional significance. A further step in this conditional analysis, using the five associated SNPs as covariates, did not result in any additional markers that passed Bonferroni or FDR multiple-testing procedures. The estimated ORs per study can be seen in Table S9.

Table 2.

Association Results from Logistic Regression

| SNP (A1, A2) |

Marginal |

Multivariate Model |

Location | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p Values | OR (95% CI) | p Values | ||

| rs1150753 (G, A) | 2.20 (2.01–2.39) | 1.0 × 10−71 | 1.67 (1.52–1.84) | 1.6 × 10−26 | class III, intronic TNXB |

| rs9271731 (A, G) | 1.34 (1.25–1.45) | 2.5 × 10−14 | 1.40 (1.29–1.51) | 3.2 × 10−17 | class II, intergenic HLA-DRB1–HLA-DQA1 |

| rs9378200 (C, T) | 0.59 (0.52–0.67) | 8.2 × 10−17 | 0.64 (0.56–0.74) | 1.7 × 10−9 | class III, upstream of BAT2 |

| rs9469220 (T, C) | 0.65 (0.61–0.68) | 1.1 × 10−47 | 0.85 (0.79–0.91) | 1.0 × 10−6 | class II, downstream of HLA-DQA1 |

| rs9265604 (G, A) | 0.83 (0.78–0.89) | 1.3 × 10−8 | 0.88 (0.82–0.93) | 7.6 × 10−5 | class I, downstream of HLA-B |

Estimated ORs (95% CIs), p values, and Bonferroni-adjusted p values are shown. “Marginal” displays the single-marker association results from SNPTEST (averaging over genotype uncertainty). “Multivariate Model” contains results when all five SNPs in the logistic regression were included, when the genotypes with maximum probability were taken, and when the model was fit with PLINK. The p values for the multivariate model tended to be less significant (than the single-marker p values) because extra degrees of freedom were taken up by the inclusion of five markers in the regression. In the first column, the first of the two alleles is the minor allele associated with the effect, and the risk allele is in bold (for example, G is the risk allele for rs1150753, whereas C is the protective allele for rs9378200). The following abbreviations are used: A1, allele 1; A2, allele 2; OR, odds ratio; and CI, confidence interval.

Association: HLA-DRB1 Alleles

Given the evidence of association between HLA-DRB1 and SLE, we sought to deduce the relationship between the associated SNPs and HLA-DRB1 alleles and to determine whether there were association signals independent of HLA-DRB1. To achieve this, we had to first impute HLA-DRB1 in all studies (step C in Figure 1) and then determine the HLA-DRB1 alleles to condition on in a repeat analysis of the SNP data (step D in Figure 1). Table S10 contains details of HLA-DRB1 imputation performance. In summary, the performance was comparable to that of a recent study of the MHC in rheumatoid arthritis21 and to that noted by the authors of HLA∗IMP.20

Consistent with the analysis for the SNP data, we applied logistic-regression models for each HLA-DRB1 allele and used a covariate to account for intra-European ancestry. This is step D-i in Figure 1. The meta-analysis of HLA-DRB1 alleles confirmed previously declared associations for HLA-DRB1∗03:01 (OR = 1.87 [95% CI = 1.73–2.02]; p = 1.17 × 10−58) and HLA-DRB1∗15:01 (OR = 1.33 [95% CI = 1.23–1.44]; p = 1.92 × 10−12). Table S11 contains association results (OR, p value, and adjusted p value) for all alleles.

We performed stepwise regression on HLA-DRB1 alleles (see Material and Methods; step D-ii in Figure 1) again by using a covariate to account for intra-European ancestry. The best HLA-DRB1 model returned by this stepwise search was DRB1∗03:01 + DRB∗15:01 + DRB1∗08:01 + DRB1∗13:02 + DRB1∗16:01. Conditional on these alleles as covariates in a multivariate logistic-regression model, the only allele showing marginal significance was HLA-DRB1∗14:01 (p = 4.4 × 10−3).

Association: SNPs Conditional on HLA-DRB1

To determine whether there were association signals independent of HLA-DRB1, we re-ran the association analysis on SNPs as before but with the addition of a range of HLA-DRB1 alleles as covariates (step E-ii in Figure 1). Alleles were chosen as a result of an analysis of HLA-DRB1 for association and prior knowledge of associated alleles. Because HLA-DRB1∗03:01 and HLA-DRB1∗15:01 were the strongest independent signals and were reported in many studies previously, they were chosen first as covariates. We also used the alleles specified in the best HLA-DRB1 model, identified above, as covariates.

The results were consistent regardless of which HLA-DRB1 alleles were chosen as covariates. Using DRB1∗03:01 + DRB1∗15:01, we found evidence of association with rs2246618 (class I; MICB [MIM 602436]), rs8192591 (class III; NOTCH4 [MIM 164951]), and rs12529318 (class II; HLA-DRA–HLA-DRB5) (FDR ≤ 0.05). Repeating the analysis with the use of DRB1∗03:01 + DRB1∗15:01 + DRB1∗08:01 + DRB1∗13:02 + DRB1∗16:01 as covariates also resulted in association with rs2246618 and rs8192591; however, rs12529318 was replaced by rs2524117 (class I; downstream of HLA-C). The class II SNP (rs12529318) perhaps tagged an effect (or effects) at classical loci (this effect was picked up with the extended set of DRB1 alleles); there was strong LD (R2 = 0.9; D′ = 0.96) between rs12529318 and HLA-DRB1∗08:01.

The effect sizes for the two SNPs (rs2246618 and rs8192591) that were consistently associated when they were conditional on HLA-DRB1 were also consistent between analyses; see Table S12 for ORs and p values for all four SNPs showing significance when conditional on either set of HLA-DRB1 alleles.

HLA Associations: HLA-B, HLA-C, HLA-DQA1, and HLA-DQB1

We found evidence of SNPs associated with SLE independently of HLA-DRB1 alleles. However, our broader aim was to ask whether the association signals within the MHC could be explained completely by HLA alleles. To achieve this, we had to impute HLA class I and class II alleles (step C in Figure 1). The accuracy of imputation for HLA-B and HLA-DQB1 was very similar to a study of the MHC in rheumatoid arthritis21 (HLA-DQA1 was not included in the RA study), and the comparison is discussed in the Material and Methods (further details are provided in the Supplemental Data.

Consistent with the analysis for the SNP data, we applied logistic-regression models to each of the class I and class II alleles and used a covariate to account for intra-European ancestry (step D-i in Figure 1).

The meta-analysis of class I alleles found very strong evidence of association for HLA-B∗08:01 (OR = 1.84 [95% CI = 1.70–1.99]; p = 3.58 × 10−53) and HLA-C∗07:01 (OR = 1.57 [95% CI = 1.47–1.69]; p = 6.26 × 10−36). The other alleles were not significant at the 0.05 level after multiple-testing adjustment (see Material and Methods). Table S11 contains association results for all alleles.

Given the known strong LD within class II, it is not surprising that we found many association signals at HLA-DQA1 and HLA-DQB1. In order to address this correlation, we also performed analyses of HLA-DQ alleles conditional on the HLA-DRB1 alleles DRB1∗03:01 and HLA-DRB1∗15:01. From this analysis, we found evidence of association independent of DRB1∗03:01 and HLA-DRB1∗15:01 (after adjusting for multiple testing) at HLA-DQA1∗05:01, HLA-DQA1∗01:01, HLA-DQA1∗01:02, HLA-DQB1∗03:01, and HLA-DQB1∗03:03 (p = 6.66 × 10−15, p = 8.88 × 10−15, p = 9.77 × 10−15, p = 4.61 × 10−22, and p = 1.50 × 10−10, respectively). Further details can be seen in the Supplemental Data and Table S11.

Model Choice: SNPs + HLA-B, HLA-C, HLA-DQA1, HLA-DQB1, and HLA-DRB1

We identified SNPs independently associated with SLE and also HLA associations. A summary of these findings can be seen in Table 3. However, we aimed to answer the more refined question as to whether the association within the MHC resides with HLA alleles only, SNPs only, or a combination of both HLA alleles and SNPs. To answer this, we searched for the best combination of SNPs and/or HLA alleles that independently explained SLE as an outcome. This is the final step (F) in Figure 1. Our model-selection criterion was the BIC because this has a heavy penalty for the inclusion of variables. However, we found that the results did not differ from those obtained with the AIC (Akaike information criterion), a model-choice metric that uses a weaker penalty (when sample sizes are large) than does the BIC for the inclusion of variables.

Table 3.

Summary of SNPs and HLA Alleles Reported as Associated within Each Analysis

| Analysis | Marker | Gene | Class |

|---|---|---|---|

| Analysis of SNPsa | |||

| Candidate SNPs independently associated from SNP-only analysis |

rs1150753 | intronic region of TNXB | III |

| rs9271731 | HLA-DRB1–HLA-DQA1 | II | |

| rs9378200 | NCR3-AIF1 | III | |

| rs9469220 | upstream of HLA-DQB1 | II | |

| rs9265604 | HLA-B–HLA-C | I | |

| HLA-DRB1 Analysisb | |||

| Candidate alleles independently associated from class II HLA-DRB1 analysis |

HLA-DRB1∗03:01 | HLA-DRB1 | II |

| HLA-DRB1∗15:01 | HLA-DRB1 | II | |

| HLA-DRB1∗08:01 | HLA-DRB1 | II | |

| HLA-DRB1∗13:02 | HLA-DRB1 | II | |

| HLA-DRB1∗16:01 | HLA-DRB1 | II | |

| HLA-DRB1∗14:01 | HLA-DRB1 | II | |

| Analysis of SNPs Conditional on HLA-DRB1c | |||

| Candidate SNPs from analysis conditional on HLA-DRB1 alleles |

rs2246618 | MICB | I |

| rs2524117 | downstream of HLA-C | I | |

| rs8192591 | NOTCH4 | III | |

| rs12529318 | HLA-DRA–HLA-DRB5 | II | |

| Analysis of HLA Class Id | |||

| Candidate alleles from class I analysis |

HLA-B∗08:01 | HLA-B | I |

| HLA-C∗07:01 | HLA-C | I | |

| Analysis of HLA-DQA1 and HLA-DQB1 Conditional on HLA-DRB1e | |||

| Candidate alleles from class II HLA-DQA1 and HLA-DQB1 analysis conditional on DRB1 | HLA-DQA1∗05:01 | HLA-DQA1 | II |

| HLA-DQA1∗01:01 | HLA-DQA1 | II | |

| HLA-DQA1∗01:02 | HLA-DQA1 | II | |

| HLA-DQB1∗03:01 | HLA-DQB1 | II | |

| HLA-DQB1∗03:03 | HLA-DQB1 | II | |

Analysis of SNPs only.

Analysis of HLA-DRB.

Analysis of SNPs conditional on HLA-DRB1.

Analysis of HLA class I only (these two signals are not independent [R2 = 0.71; D′ = 0.98]).

HLA-DQA1 and HLA-DQB1 alleles associated when conditioned on HLA-DRB1. These signals, which were the only alleles significant in single-marker association tests conditional on DRB1, are not necessarily independent. The bolded SNPs and alleles are those included in the best model for independent association.

We ran a stepwise logistic regression by using all HLA alleles (class I and II) together with the five SNPs identified as independently associated without reference to the HLA alleles (Table 2) and the SNPs (rs2246618, rs8192591, rs2524117, and rs12529318) identified by the regression conditional on HLA-DRB1 alleles. The model search began from various starting points (see Material and Methods and Table S13), including the simplest model with no HLA alleles or SNPs and single-marker models with HLA alleles or SNPs that were significant in a single-marker association. We also used the best HLA model, as well as the best models from individual HLA loci, as a starting point (see Material and Methods; step D-ii in Figure 1). In all models, we included the same covariate to account for intra-European ancestry as in all previous analyses (of HLA alleles and SNPs).

Table 4 displays the model (model C) that resulted as the best fit to the data from this search. Several other models are displayed as they were within a BIC of 10 of the model with the lowest BIC. There is some uncertainty as to the best model. However, the following six variables (model F) were consistently included in models within a BIC of 10 of the best model: HLA-DRB1∗03:01 + HLA-DRB1∗08:01 + HLA-DQA1∗01:02 + rs2246618 (MICB) + rs8192591 (NOTCH4) + rs2524117 (HLA-C). The uncertainty relates to whether we find evidence of a further two signals at HLA-DRB1∗14:01 and HLA- DQB1∗03:01 (model C) or a single further signal at HLA-DQB1∗03:02 (model D). However, HLA-DQB1∗03:02 does not seem to be an independent effect because the marginal effect was observed to be slightly protective and nonsignificant (OR = 0.95 [95% CI = 0.87–1.05]; p = 0.31), whereas the effect is risk in model D (p = 1 × 10−4). Table 5 contains OR estimates and p values for all variables in Table 4 models C and F. The estimated ORs per study can be seen in Table S4.

Table 4.

HLA Alleles and SNPs Contained in Models within a BIC of 10 of the Model with the Lowest BIC and Lowest AIC

| Model | Model Description | Variables in Model | Difference in BIC | Difference in AIC | Bayes Factora | Markers Considered | Start |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | best set of SNPs independently associated with SLE | rs1150753 + rs9271731 + rs9378200 + rs9469220 + rs9265604 | +9 | +32 | 90.02 | all 7,122 SNPs | null |

| B | best set of HLA (class I and II) alleles associated with SLE | HLA-DRB1∗03:01 + HLA-DRB1∗08:01 + HLA-DQA1∗01:02 + HLA-DRB1∗01:02 + HLA-DRB1∗14:01 + HLA-B∗08:01 + HLA-DQB1∗03:01 + HLA-DQB1∗03:03 + HLA-C∗12:03 | +25 | +18 | 27K | all HLA Alleles | null, multiple HLA modelsb |

| C | model with lowest BIC | HLA-DRB1∗03:01 + HLA-DRB1∗08:01 + HLA-DQA1∗01:02 + HLA-DRB1∗14:01 + HLA-DQB1∗03:01 + rs2246618 + rs8192591 + rs2524117 | 0 | 0 | 1.00 | all HLA alleles (except DRB1∗03:02) plus SNPs independent of HLA-DRB1 | null, multiple HLA modelsb |

| D | alternative model | HLA-DRB1∗03:01 + HLA-DRB1∗08:01 + HLA-DQA1∗01:02 + HLA-DQB1∗03:02 + rs2246618 + rs8192591 + rs2524117 | +1 | +9 | 1.65 | all HLA alleles plus SNPs independent of HLA-DRB1 | null, multiple HLA modelsb |

| E | alternative model | HLA-DRB1∗0301 + HLA-DRB1∗0801 + HLA-DQA1∗0102 + HLA-B∗08:01 + HLA-DQB1∗0302 + rs8192591 + rs2524117 | +7 | +15 | 33.12 | all HLA alleles plus SNPs independent of HLA-DRB1 | null, multiple HLA modelsb |

| F | set of HLA alleles and SNPs consistently observed in models above | HLA-DRB1∗03:01 + HLA-DRB1∗08:01 + HLA-DQA1∗01:02 + rs2246618 + rs8192591 + rs2524117 | +6 | +22 | 20.09 | N/A | N/A |

We also include the best HLA model (model B) and the model (using only SNPs) returned by stepwise logistic regression (model A). The following abbreviations are used: BIC, Bayesian information criterion; AIC, Akaike information criterion; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; and HLA, human leukocyte antigen.

The estimate of the Bayes factor is taken from the BIC as an estimate of the log of the marginal likelihood under the assumption of vague priors for the ORs; for example, the estimate of the Bayes factor for model C to model A is Exp(0.5 × [BICA – BICC]). The alleles and SNPs that are consistently included across models are in bold. “Null” refers to no markers included. The column “Start” describes models taken as starting models in the stepwise regression.

Search started from multiple points, namely individually associated HLA alleles and best set of alleles for each class: class I (HLA-B∗08:01 + HLA-B∗57:01 + HLA-B∗44:02 + HLA-C∗12:03), class II (HLA-DRB1∗03:01 + HLA-DQA1∗01:02 + HLA-DRB1∗08:01 + HLA-DQB1∗03:02 + HLA-DQB1∗03:03), HLA-B (HLA-B∗08:01 + HLA-B∗57:01 + HLA-B∗44:02), HLA-C (HLA-C∗07:01 + HLA-C∗12:03 + HLA-C∗03:04 + HLA-C∗07:02), HLA-DRB1 (HLA-DRB1∗03:01 + HLA-DRB1∗15:01 + HLA-DRB1∗08:01 + HLA-DRB1∗13:02 + HLA-DRB1∗16:01), HLA-DQA1 (HLA-DQA1∗01:02 + HLA-DQA1∗05:01 + HLA_DQA1∗04:01), and HLA-DQB1 (HLA-DQB1∗02:01 + HLA-DQB1∗06:02 + HLA-DQB1∗03:01 + HLA-DQB1∗03:03 + HLA-DQB1∗05:03 + HLA-DQB1∗05:01). We found model B by starting from the null with no variables. We found model D by starting from the null model with no variables. We found model C by removing HLA-DQB1∗03:02 from the search (because there is evidence that this is not an independent signal; see Results). We found model E directly by starting the search with HLA-B∗08:01 alone. Note that we found models C–E by only including SNPs independent of the HLA alleles; we found no models within a BIC of 10 of the minimum when we included the additional five SNPs.

Table 5.

Effect Sizes and p Values for Variables in Models C and F in Table 4

| Variable |

Model C |

Model F |

Marginal |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p Value | OR (95% CI) | p Value | OR (95% CI) | p Value | |

| DRB1∗03:01 | 1.67 (1.51–1.84) | 4.3 × 10−27 | 1.77 (1.60–1.95) | 2.1 × 10−36 | 1.87 (1.73–2.02) | 1.17 × 10−58 |

| DRB1∗08:01 | 1.57 (1.29–1.91) | 2.8 × 10−6 | 1.67 (1.40–1.99) | 7.7 × 10−8 | 1.34 (1.12–1.60) | 1.32 × 10−3 |

| DQA1∗01:02 | 1.46 (1.35–1.58) | 3.4 × 10−22 | 1.55 (1.44–1.68) | 1.4 × 10−32 | 1.31 (1.22–1.40) | 9.77 × 10−15 |

| DRB1∗14:01 | 0.65 (0.51–0.82) | 2.2 × 10−4 | N/A | N/A | 0.56 (0.45–0.70) | 2.58 × 10−7 |

| DQB1∗03:01 | 0.84 (0.78–0.91) | 1.7 × 10−4 | N/A | N/A | 0.68 (0.63–0.73) | 4.61 × 10−22 |

| rs2246618 (A, G) | 1.17 (1.09–1.27) | 9.6 × 10−6 | 1.16 (1.07–1.26) | 2.3 × 10−5 | 1.49 (1.40–1.58) | 1.76 × 10−36 |

| rs8192591 (A, G) | 0.53 (0.65–0.44) | 1.7 × 10−9 | 0.56 (0.46–0.68) | 1.7 × 10−8 | 0.54 (0.46–0.63) | 1.33 × 10−13 |

| rs2524117 (G, A) | 1.17 (1.09–1.26) | 8.8 × 10−6 | 1.19 (1.10–1.28) | 3.0 × 10−6 | 1.34 (1.26–1.43) | 8.20 × 10−21 |

The last column has the marginal effect sizes and p values. For the SNPs, the first allele is the minor allele associated with the effect, and the risk allele is in bold. The following abbreviations are used: OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval, and N/A, not available.

The possible effect of HLA-B∗08:01 is interesting. Marginally, this is very significant (OR = 1.84 [95% CI = 1.70–1.99]; p = 3.58 × 10−53), whereas in model E (Table 4), where HLA-B∗08:01 replaces one of the class I SNPs (rs2246618), its effect is modest (OR = 1.19 [95% CI = 1.05–1.33]; p = 0.008). This allele is clearly not independent of rs2246618, which is in class I (MICB; R2 = 0.29; D′ = 0.93); however, rs2246618 is a better explanation of the data than is the combination of HLA-B∗08:01 and HLA-DQB1∗03:02 (model F versus model E).

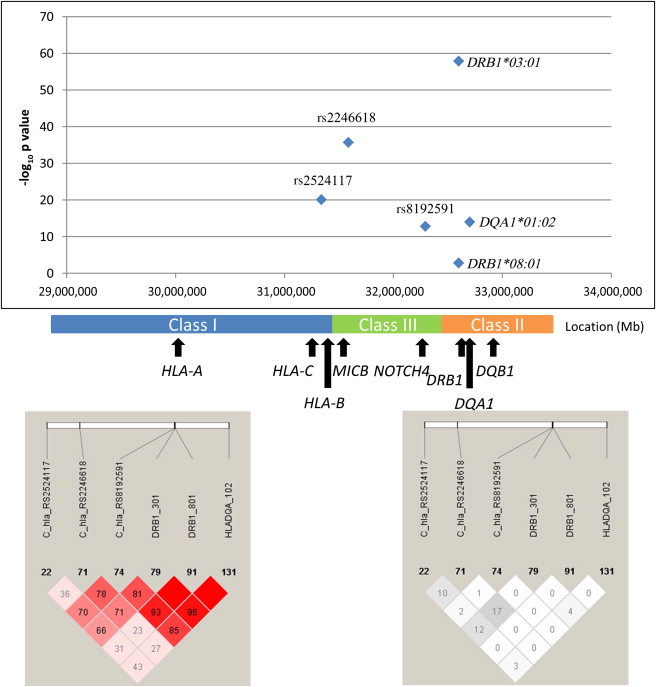

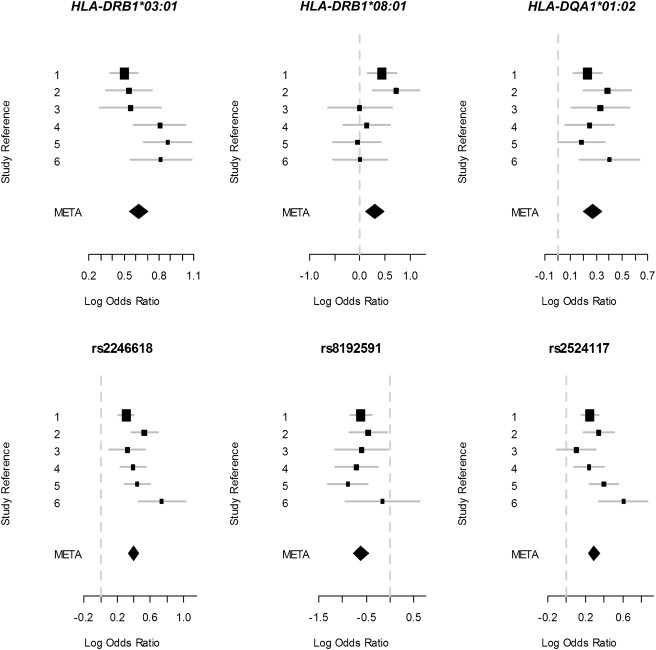

The model including only the five SNPs in Table 2 is strongly rejected with these data; the BIC gives a Bayes-factor (BF) estimate of 90 in favor of the model with HLA plus SNPs (see Table 4). Furthermore, the model including only HLA alleles is very strongly rejected with these data; the BIC gives a BF estimate of over 1,000 in favor of the model with HLA plus SNPs. Our data therefore strongly favor a combination of HLA alleles and SNPs as opposed to a model with only HLA alleles or only SNPs. The positions of each marker within the MHC can be seen in Figure 3, and forest plots for the log ORs (marginally for each marker) can be seen in Figure 4.

Figure 3.

Representation of Three SNPs Associated Independently of Classical HLA Alleles and the Three HLA Alleles that Consistently Appear in the Best Models Explaining SLE Risk

The bottom left panel shows LD as measured by D′, and the bottom right panel shows LD as measured by r2.

Figure 4.

Forest Plots of the Log ORs for the HLA Alleles and SNPs in the Final Model for SLE Association within the MHC

The error lines cover 95% confidence intervals. The box sizes are relative to study size. Study reference codes are the following: 1, Illumina 550K; 2, Illumina 317K; 3, Affy500K; 4, Illumina MHC Panel; 5, Illumina Custom; and 6, Affy100K.

Confounding Effects Created by LD among SNPs and HLA Alleles

We observed many SNPs and HLA alleles whose effects were significant marginally but that could be explained by LD with other alleles. Our study cannot claim to identify all of these confounding effects, but we can explain some. See Figures S2A (numbers indicate R2) and S2B (numbers indicate D′) for the LD structure in our data among all HLA alleles and all SNPs considered in our results.

An important example in this study is the associations observed in the analysis of SNP-only data. These same five SNPs were also observed to be the only significant associations when we included HLA-DRB1 alleles (along with the eight candidate SNPs) and ran a conditional logistic regression starting from no variables. The reason for this is that the most associated marker (rs1150753) was correlated with HLA-DRB1∗03:01 (R2 = 0.73; D′ = 0.92). Therefore, when we conditioned on this SNP, the effect at HLA-DRB1∗03:01 was not observed to be very strong (p = 0.006), whereas we found that the class II SNP rs9271731 was very significantly associated; this latter SNP tagged HLA-DRB1∗15:01 (R2 = 0.68; D′ = 0.99). The most associated marker, rs1150753, was also correlated with class I alleles, such as HLA-B∗08:01 (R2 = 0.72; D′ = 0.89), and so this HLA allele was also not significant when it was conditioned on rs1150753. The starting point for conditional logistic regression (stepwise regression) therefore affects all subsequent association signals.

Related specifically to the HLA, another important example in our data is HLA-DRB1∗15:01, which was marginally significant (OR = 1.33 [95% CI = 1.23–1.44]; p = 1.92 × 10−12), but not when the effect of HLA-DQA1∗01:02 was accounted for (p = 0.162). However, when we conditioned on HLA-DRB1∗15:01, the effect of HLA-DQA1∗01:02 was still borderline significant (OR = 1.23 [95% CI = 1.10–1.38]; p = 2.78 × 10−4). This suggests that the observed association of HLA-DRB1∗15:01 is due to its correlation with HLA-DQA1∗01:02, whereas the association of HLA-DQA1∗01:02 cannot be explained by its correlation with HLA-DRB1∗15:01.

HLA-DQA1∗01:02 was also in LD (R2 = 0.16; D′ = 0.96) with HLA-DRB1∗13:02, which suggests that our signal at HLA-DQA1 could be a composite of two DRB1 signals. However, we did not find evidence of this in our data; replacing DQA1∗01:02 with DRB1∗15:01 + DRB1∗13:02 gave a BIC difference of 14 in favor of DQA1∗01:02.

HLA-DQA1∗01:02 lies on various HLA-DRB1–HLA-DQB1 haplotype backgrounds,26 including HLA-DRB1∗16:01, so we also considered the HLA-DQA1∗01:02 effect against these haplotypes. If the HLA-DQA1∗01:02 is the causal locus, then there should be no heterogeneity in risk over these haplotypes; however, if there is heterogeneity in risk, then HLA-DRB1 might be the likely source of risk. We found no evidence of heterogeneity of risk (p = 0.6). See Table S14 for more details on haplotypes and analysis.

RNA Expression Analysis

We sought to determine whether any of the SNPs independently associated with SLE show evidence of correlation with cis-acting gene expression. From the Gene Expression Omnibus repository (which contains RNA extracted from lymphoblastoid cell lines in unrelated HapMap individuals; see Material and Methods), we found modest evidence that the class I SNP rs2246618 is correlated with HLA-C expression (p = 0.007; risk allele associated with reduced expression). We found no evidence that rs8192591 is correlated with expression of NOTCH4 (p = 0.65) and no evidence that rs2524117 is associated with expression of HLA-C (p = 0.97). We conducted six tests in total (see Material and Methods), and so rs2246618 is significant at the 0.05 level.

Haplotype Analysis

The results we have presented include HLA alleles and SNPs that show statistical evidence of independent association with SLE. However, this might not translate directly to independent loci as a result of the extended LD known to exist in the MHC; it is very possible that markers that seem to be acting independently with respect to genotype risk could be on a shared haplotype. We therefore used PLINK15 to test each of the HLA alleles and SNPs for association independent of the HLA-DRB1∗03:01 and HLA-DRB1∗15:01 haplotype backgrounds (see Material and Methods).

The results of the conditional haplotype analysis can be seen in Table 6. We confirmed that rs2246618 and rs8192591 are associated with SLE independently of the extended HLA-DRB1∗03:01 haplotype and the HLA-DRB1∗15:01 haplotype. We found that rs2524117 might tag the HLA-DRB1∗03:01 haplotype because we failed to find evidence of a risk effect for this SNP when it was conditioned on the background for the alleles contained in this haplotype. However, we did find evidence of an independent risk effect for HLA-DRB1∗03:01 (p = 0.002, Bonferroni adjusted < 0.05). We also found evidence that HLA-DQA1∗01:02 has a risk effect independent of the extended HLA-DRB1∗15:01 haplotype (p = 0.003).

Table 6.

p Values for Conditional Haplotype Results

| Location of Gene or SNP | HLA Allele or SNP |

Haplotype Conditioned on |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Hap-DRB1∗03:01 | Hap-DRB1∗15:01 | ||

| Class II | DRB1∗03:01 | 0.002∗ | N/A |

| Class II | DRB1∗15:01 | N/A | 0.251 |

| Class II | DQA1∗01:02 | 1.19 × 10−21∗∗∗ | 0.00264∗ |

| Class III: upstream of NOTCH4 | rs8192591 | 9.61 × 10−5∗∗ | 0.000346∗∗ |

| Class I: downstream of HLA-C | rs2524117 | 0.921 | 5.22 × 10−14∗∗∗ |

| Class I: MICB | rs2246618 | 0.000919∗ | 2.21 × 10−23∗∗∗ |

Each allele or SNP in the first column was tested for association with SLE and was conditional on the haplotypes formed by the alleles in each of the haplotypes: Hap-DRB1∗03:01 (HLA-B∗08:01 – HLA-C∗07:01 – DRB1∗03:01 – DQA1∗05:01 – DQB1∗02:01) and Hap-DRB1∗15:01 (HLA-B∗07:02 – HLA-C∗07:02 – DRB1∗15:01 – DQA1∗01:02 – DQB1∗06:02). The null hypothesis is that there is no association for the allele or SNP when the background haplotype is fixed. We failed to reject this, for example, for HLA-DRB1∗15:01 when we conditioned on Hap-DRB1∗15:01, whereas we did reject this for HLA-DQA1∗01:02 when we conditioned on Hap-DRB1∗15:01 at the adjusted 0.05 level. The p values in the table are not corrected for multiple testing; assuming ten independent tests and taking a Bonferroni correction leads to those rejected at the 0.05 level (∗), those rejected at the 0.01 level (∗∗), and those rejected at the 0.001 level (∗∗∗). The following abbreviations are used: HLA, human leukocyte antigen; and N/A, not available.

These analyses do not implicate HLA-DRB1∗15:01 because this allele’s observed effect is not independent of the extended haplotype (p = 0.251). Although the class I SNP rs2246618 has an effect independent of the HLA-DRB1∗03:01 haplotype, neither HLA-B∗08:01 nor rs2524117 were found to have effects independent of the haplotype. These two variables (HLA-B∗08:01 and rs2524117) most likely tag the same effect, and rs2524117 is the more likely candidate on the basis of our analysis.

Discussion

We have performed the largest study to date of the MHC in SLE by bringing together six data sets from previously published studies in a meta-analysis. Previous to this study, many association signals had been found in the MHC; however, very little was understood about which alleles were the driving force behind the association and which were associated as a result of correlation (LD). The class II alleles HLA-DRB1∗03:01 and HLA-DRB1∗15:01 have been consistently reported as being associated with SLE. Other class II loci (HLA-DQA1 and HLA-DQB1) have also been reported as being associated; however, they are in strong LD with HLA-DRB1, and so the observed association could simply be HLA-DRB1 tagging effects. This is also true of observed associations at SNPs across the MHC.

Our results support and refine previous findings (a UK study,5 a US study,7 and the Illumina Custom6) of multiple signals in the MHC for a population of European ancestry. The UK study5 reported two independent signals: one in class III (rs419788 [32,036,778 bp]) and one in class II (HLA-DRB1∗03:01). This class III marker is significant in our meta-analysis (p = 1.4 × 10−47). However, it is not significant (p = 0.33) when it is conditioned on both the most associated single marker, rs1150753, and the second independent signal (rs9271731; class II), which suggests that this SNP tags class II and III signals. The UK study did not find evidence that a class I SNP (rs2523589 [31,435,313 bp]), which was associated as a single marker, was independent of HLA-DRB1∗03:01. We found an association at this marker (p = 1.5 × 10−21), but this was not independent of our most associated marker (p = 1.5 × 10−4). This suggests that the class I marker reported in the UK study in fact tags class II and III effects and that the class I signal lies elsewhere. The class I marker reported in the UK study is not correlated (R2 = 0.007) with the SNP, rs2246618 (class I; 31,586,965 bp), that we found to be associated independently of HLA-DRB1. The US study7 also found class I association signals independent of HLA-DRB1∗03:01.

The Illumina Custom study found that the strongest association was in class III (rs1269852 [32,151,660 bp]) and that this SNP was still significant when it was conditioned on HLA-DRB1∗03:01, whereas the HLA-DRB1∗03:01 effect was not significant when it was conditioned on rs1269852. They hypothesized that their imperfect HLA imputation might have underestimated the HLA-DRB1∗03:01 effect. rs1269852 is significantly associated in our meta-analysis (p = 1.2 × 10−71) and is very correlated with our most significant single marker, rs1150753 (R2 = 0.99). We also found that the significance of HLA-DRB1∗0301 decreased (p = 0.0006) when we conditioned on the most strongly associated marker (rs1150753). However, when we conditioned on the class III SNP rs8192591 (the class III SNP in our final model), HLA-DRB1∗0301 was significant (p = 5.8 × 10−58). In fact, when we conditioned on all markers in our final model (see Table 5), HLA-DRB1∗03:01 was still very significant. Our results suggest that the most associated class III SNP tags both HLA-DRB1∗03:01 and an association in class I (which is why it was significant when it was conditioned on HLA-DRB1∗0301) and that including this marker in a model of SLE association might confound subsequent conditional associations. All these previous studies contributed samples to this meta-analysis, so the consistencies are expected. However, the size of our data set allowed us to identify more independent signals and disentangle HLA from non-HLA associations.

Approaches such as stepwise regression can be misleading because they are dependent on the primary association; the first signal might tag two or more associated loci, which will then be missed in further conditional analyses. This is evident from our data (analysis with SNPs and all HLA-DRB1 alleles); stepwise regression, beginning from a model with no variables, only returns the five SNPs identified from the SNP-only analysis as significant and misses HLA-DRB1∗03:01. Our approach was to perform a multistart stepwise procedure in which we begin each search from HLA alleles with evidence a priori to be associated with disease and alleles identified as associated with subanalyses of our current data. Importantly, our analyses converged to just a few models, the best of which was overwhelmingly a better fit (as judged by the BIC or AIC) to the data than was a model with HLA alleles alone or with SNPs alone. The approach we have taken will be useful for analyzing other immune-related diseases in which there are multiple association signals at the MHC.

We identified the best model for genetic association by considering classical HLA loci (HLA-B, HLA-C, HLA-DRB1, HLA-DQA1, and HLADQB1) and 7,199 SNPs across the extended MHC. From these data, there is strong evidence that the alleles DRB1∗03:01, DRB1∗08:01 and DQA1∗01:02 are the driving force behind classical HLA association signals. In class II, there are additional signals that are likely to be HLA-DRB1∗14:01 and HLA-DQB1∗03:01, but we cannot completely rule out HLA-DRB1:11 alleles, such as HLA-DRB1∗11:01, because these had lower imputation accuracy than did other common (MAF >1%) HLA-DRB1 alleles. We found evidence that three SNPs (rs2246618 [class I, MICB], rs8192591 [class III, upstream of NOTCH4], and rs2524117 [class I, downstream of HLA-C]) are associated independently of HLA alleles. However, because we could not validate our imputation of HLA-C alleles, we cannot rule out the possibility that rs2246618 tags a poorly imputed HLA-C allele. Our results also suggest that the often reported association at HLA-DRB1∗15:01 is due to this allele’s correlation with HLA-DQA1∗01:02 because we found that the data are better explained by HLA-DQA1∗01:02. Both of these alleles were imputed, but HLA-DRB1∗15:01 had slightly better accuracy in our validation (Tables S10A, S10B, and S10D), and so our finding cannot be explained by lower power as a result of imputation uncertainty for HLA-DRB1∗15:01.

On subsequent conditional haplotype testing, we found that rs2524117 most likely tags the extended HLA-DRB1∗03:01 haplotype (HLA-A∗01:01 – C∗07:01 – B∗08:01 – DRB1∗03:01 – DQA1∗05:01 – DQB1∗02:01). This result does not reject the additional association in class I; rather, it is a lack of evidence that the signal arises from rs2424117. Therefore, although our best model for association does include this SNP (the BIC without this marker is worse by 12), we only report association independent of classical HLA alleles at rs2246618 and rs8192591. The other class I SNP (rs2246618), which we found to be correlated with HLA-C expression, was associated independently of both haplotypes, as was rs8192591. We also tested each of the associated HLA alleles and SNPs for dominant and recessive effects (see Table S15); with the exception of rs2524117, which is most likely dominant, none showed significant deviation from an additive model.

In summary, we performed a large meta-analysis of SLE studies of European ancestry to determine association at classical HLA genes and SNPs independent of these loci. Our results extend and refine the genetic contribution of the MHC region to risk of SLE. There was some uncertainty in our model choice, but the inclusion of the classical HLA alleles HLA-DRB1∗03:01, HLA-DRB1∗08:01, and HLA-DQA1∗01:02 was clear. The class III SNP rs8192591 was associated independently of both the extended HLA-DRB1∗03:01 and HLA-DRB1∗15:01 SLE risk haplotypes, which implies either a further independent association at HLA-DRB1 or HLA-DQ or an effect outside of classical loci, possibly at NOTCH4. Furthermore, the class I SNP rs2246618 was associated independently of both the extended HLA-DRB1∗03:01 and HLA-DRB1∗15:01 SLE risk haplotypes and was possibly correlated with HLA-C expression. Our results are not determined by the most associated signal in any locus within the MHC (SNPs or HLA alleles) because our approach, using multiple stepwise regression analyses, converged on just a few HLA alleles and SNPs, which are displayed in Table 4. This study has provided evidence that the genetic contribution to SLE within the MHC is composed of several independent loci, some of which are most likely independent of classical HLA alleles.

Acknowledgments

We thank the original study participants and their families for their contributions to this research, as well as clinical colleagues who facilitated data collection. We thank Bryan Howie and Jonathan Marchini for their valuable advice in the planning of the imputation analysis. We thank Alexander Dilthey for his advice during the human-leukocyte-antigen imputation. We also thank the investigators of IMAGEN (John D. Rioux, Philippe Goyette, Timothy J. Vyse, Lennart Hammarström, Michelle M.A. Fernando, Todd Green, Philip L. De Jager, Sylvain Foisy, Joanne Wang, Paul I.W. de Bakker, Stephen Leslie, Gilean McVean, Leonid Padyukov, Lars Alfredsson, Vito Annese, David A. Hafler, Qiang Pan-Hammarström, Ritva Matell, Stephen J. Sawcer, Alastair D. Compston, Bruce A.C. Cree, Daniel B. Mirel, Mark J. Daly, Tim W. Behrens, Lars Klareskog, Peter K. Gregersen, Jorge R. Oksenberg, and Stephen L. Hauser) and the SLEGEN Consortium (John B. Harley, Marta E. Alarcón-Riquelme, Lindsey A. Criswell, Chaim O. Jacob, Robert P. Kimberly, Kathy L. Moser, Betty P. Tsao, Timothy J. Vyse, and Carl D. Langefeld). A full list of the investigators who contributed to the generation of the Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium (WTCCC) data is available from the WTCCC website (see Web Resources). Control subjects from the National Institute of Mental Health data and biomaterials were collected by the “Molecular Genetics of Schizophrenia II” collaboration. The investigators and coinvestigators, as well as members of the GENLES collaboration in Argentina and those who contributed samples to the 100K genome-wide association study, can be seen in the Supplemental Data.

Contributor Information

Lindsey A. Criswell, Email: lindsey.criswell@ucsf.edu.

Timothy J. Vyse, Email: tim.vyse@kcl.ac.uk.

Supplemental Data

Web Resources

The URLs for data presented herein are as follows:

Gene Expression Omnibus repository, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE6536

Welcome Trust Case Control Consortium data, www.wtccc.org.uk

National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), http://zork.wustl.edu/nimh/

Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM), http://www.omim.org

References

- 1.Moser K.L., Kelly J.A., Lessard C.J., Harley J.B. Recent insights into the genetic basis of systemic lupus erythematosus. Genes Immun. 2009;10:373–379. doi: 10.1038/gene.2009.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnson A.D., O’Donnell C.J. An open access database of genome-wide association results. BMC Med. Genet. 2009;10:6. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-10-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hom G., Graham R.R., Modrek B., Taylor K.E., Ortmann W., Garnier S., Lee A.T., Chung S.A., Ferreira R.C., Pant P.V. Association of systemic lupus erythematosus with C8orf13-BLK and ITGAM-ITGAX. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008;358:900–909. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0707865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harley J.B., Alarcón-Riquelme M.E., Criswell L.A., Jacob C.O., Kimberly R.P., Moser K.L., Tsao B.P., Vyse T.J., Langefeld C.D., Nath S.K., International Consortium for Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Genetics (SLEGEN) Genome-wide association scan in women with systemic lupus erythematosus identifies susceptibility variants in ITGAM, PXK, KIAA1542 and other loci. Nat. Genet. 2008;40:204–210. doi: 10.1038/ng.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fernando M.M., Stevens C.R., Sabeti P.C., Walsh E.C., McWhinnie A.J., Shah A., Green T., Rioux J.D., Vyse T.J. Identification of two independent risk factors for lupus within the MHC in United Kingdom families. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:e192. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rioux J.D., Goyette P., Vyse T.J., Hammarström L., Fernando M.M., Green T., De Jager P.L., Foisy S., Wang J., de Bakker P.I., International MHC and Autoimmunity Genetics Network Mapping of multiple susceptibility variants within the MHC region for 7 immune-mediated diseases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:18680–18685. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909307106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barcellos L.F., May S.L., Ramsay P.P., Quach H.L., Lane J.A., Nititham J., Noble J.A., Taylor K.E., Quach D.L., Chung S.A. High-density SNP screening of the major histocompatibility complex in systemic lupus erythematosus demonstrates strong evidence for independent susceptibility regions. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000696. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Graham R.R., Ortmann W.A., Langefeld C.D., Jawaheer D., Selby S.A., Rodine P.R., Baechler E.C., Rohlf K.E., Shark K.B., Espe K.J. Visualizing human leukocyte antigen class II risk haplotypes in human systemic lupus erythematosus. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2002;71:543–553. doi: 10.1086/342290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hocking R.R. A Biometrics Invited Paper: The Analysis and Selection of Variables in Linear Regression. Biometrics. 1976;32:1–49. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Graham R.R., Cotsapas C., Davies L., Hackett R., Lessard C.J., Leon J.M., Burtt N.P., Guiducci C., Parkin M., Gates C. Genetic variants near TNFAIP3 on 6q23 are associated with systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat. Genet. 2008;40:1059–1061. doi: 10.1038/ng.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kozyrev S.V., Abelson A.K., Wojcik J., Zaghlool A., Linga Reddy M.V., Sanchez E., Gunnarsson I., Svenungsson E., Sturfelt G., Jönsen A. Functional variants in the B-cell gene BANK1 are associated with systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat. Genet. 2008;40:211–216. doi: 10.1038/ng.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium Genome-wide association study of 14,000 cases of seven common diseases and 3,000 shared controls. Nature. 2007;447:661–678. doi: 10.1038/nature05911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leslie S., Donnelly P., McVean G. A statistical method for predicting classical HLA alleles from SNP data. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2008;82:48–56. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Benjamini Y., Hochberg Y. Controlling the False Discovery Rate: A Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. J R Stat Soc Series B Stat Methodol. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Purcell S., Neale B., Todd-Brown K., Thomas L., Ferreira M.A.R., Bender D., Maller J., Sklar P., de Bakker P.I.W., Daly M.J., Sham P.C. PLINK: A tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2007;81:559–575. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Price A.L., Patterson N.J., Plenge R.M., Weinblatt M.E., Shadick N.A., Reich D. Principal components analysis corrects for stratification in genome-wide association studies. Nat. Genet. 2006;38:904–909. doi: 10.1038/ng1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pritchard J.K., Stephens M., Donnelly P. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics. 2000;155:945–959. doi: 10.1093/genetics/155.2.945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cunninghame Graham D.S., Morris D.L., Bhangale T.R., Criswell L.A., Syvänen A.C., Rönnblom L., Behrens T.W., Graham R.R., Vyse T.J. Association of NCF2, IKZF1, IRF8, IFIH1, and TYK2 with systemic lupus erythematosus. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002341. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Howie B.N., Donnelly P., Marchini J. A flexible and accurate genotype imputation method for the next generation of genome-wide association studies. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000529. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dilthey A.T., Moutsianas L., Leslie S., McVean G. HLA∗IMP—An integrated framework for imputing classical HLA alleles from SNP genotypes. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:968–972. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Raychaudhuri S., Sandor C., Stahl E.A., Freudenberg J., Lee H.-S., Jia X., Alfredsson L., Padyukov L., Klareskog L., Worthington J. Five amino acids in three HLA proteins explain most of the association between MHC and seropositive rheumatoid arthritis. Nat. Genet. 2012;44:291–296. doi: 10.1038/ng.1076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stranger B.E., Forrest M.S., Dunning M., Ingle C.E., Beazley C., Thorne N., Redon R., Bird C.P., de Grassi A., Lee C. Relative impact of nucleotide and copy number variation on gene expression phenotypes. Science. 2007;315:848–853. doi: 10.1126/science.1136678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lin D.Y., Zeng D. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies: No efficiency gain in using individual participant data. Genet. Epidemiol. 2010;34:60–66. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marchini J., Howie B., Myers S., McVean G., Donnelly P. A new multipoint method for genome-wide association studies by imputation of genotypes. Nat. Genet. 2007;39:906–913. doi: 10.1038/ng2088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]