The Editor — Sir,

Influenza A (H1N1) virus-associated pneumonia is an atypical pneumonia that has recently been reported in Mexico and the United States, and has since spread throughout the world. As of July 31 2009, 168 countries and overseas territories/communities have reported at least one laboratory-confirmed case of this infection. All continents are affected by the pandemic [1]. The clinical symptoms, in the greatest number of cases, consist of mild clinical presentations with influenza-like illness. In addition, cases of severe illness, such as acute respiratory distress syndrome and even death, have been reported in previously healthy persons [2].

A 25-year-old previously healthy woman presented with a 5-day history of fever, headache, myalgia and dry cough. Her symptoms rapidly progressed to chest pain, progressive dyspnoea, worsening clinical status and syncope, which led to her being admitted to the Emergency Department. On physical examination, she had a general aspect of suffering: prostration, tachypnoea (40 breaths per min), tachycardia (120 beats per min), an axillary temperature of 101.3°F (38.5°C) and a blood pressure of 90/40 mmHg. Oxygen saturation level in room air was 84% (normal level, >95%). There were crackles in both lungs. The remainder of the examination was normal. She was subsequently transferred to the intensive care unit.

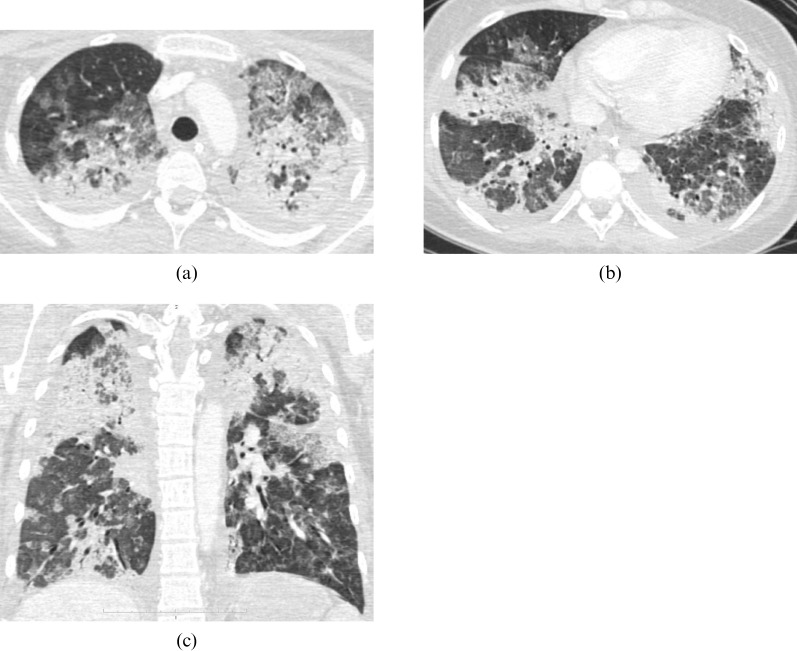

Laboratory tests performed at admission revealed a normal white cell count, absolute lymphopenia (800 lymphocytes mm−3), pH of 7.34, arterial oxygen tension of 49 mmHg, arterial carbon dioxide tension of 33 mmHg, C-reactive protein level of 19.1 mg dl−1, lactate dehydrogenase level of 1040 IU l−1 and creatine kinase level of 600 IU l−1. The patient fulfilled the criteria for a confirmed case of infection with novel influenza A (H1N1) virus established by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which are the presence of an influenza-like illness and a laboratory-confirmed novel influenza A (H1N1) virus infection by real-time polymerase chain reaction [3]. Bedside anteroposterior chest X-ray revealed diffuse bilateral air-space consolidation. High-resolution CT (HRCT) performed 12 h after admission showed diffuse consolidations and ground-glass opacities predominating in the upper lung areas (Figure 1). The patient developed severe refractory hypoxaemia, and mechanical ventilation was required. The patient died two days after admission.

Figure 1.

High-resolution CT obtained 5 days after the onset of symptoms. Scans obtained at the level of the (a) upper and (b) lower lobes showing consolidations and ground-glass opacities in both lungs. Note also the bilateral pleural effusion. (c) Coronal reconstruction demonstrates that the consolidations are diffuse but predominate in the upper areas.

Perez–Padilla et al [2] described the clinical and epidemiological characteristics of 18 patients hospitalised for pneumonia in Mexico who had laboratory-confirmed influenza A (H1N1) infection. The patients, most of whom were previously healthy, had an influenza-like illness that progressed to acute lung injury or acute respiratory distress syndrome. All patients had fever, cough, dyspnoea or respiratory distress, and bilateral patchy radiologically confirmed pneumonia. 12 patients required mechanical ventilation, and 7 died. The most consistent laboratory characteristics were increased lactate dehydrogenase levels, a total leukocyte count within normal limits, lymphopenia and increased creatine kinase levels. Histopathological samples obtained from one case showed necrosis of the bronchiolar walls, a neutrophilic infiltrate, and diffuse alveolar damage with prominent hyaline membranes. The Novel Swine-Origin Influenza A (H1N1) Virus Investigation Team observed similar clinical and epidemiological findings in the United States outbreak [4].

Evidence from multiple outbreak sites demonstrates that the H1N1 pandemic virus has rapidly established itself and is now the dominant influenza strain in most parts of the world. The pandemic will persist in the coming months as the virus continues to move through susceptible populations. The overwhelming majority of patients continue to experience mild illness. Although the virus can cause severe and fatal illness, even in young and healthy people, the number of such cases remains small. Clinicians from around the world are reporting a very severe form of the disease, again even in young and otherwise healthy people, that is rarely seen during seasonal influenza infections [5]. The World Health Organization is advising countries in the northern hemisphere to prepare for a second wave of pandemic spread during the next winter. Countries with tropical climates, where the pandemic virus arrived later than elsewhere, also need to prepare for an increasing number of cases [5]. As the outbreak of influenza A (H1N1) virus has been relatively recent, reports on this subject are limited.

For the majority of patients with pneumonia, chest radiography provides adequate imaging information and a CT scan is not warranted. However, CT, particularly HRCT, is helpful especially when there is a high clinical suspicion for pneumonia in the presence of normal or questionable radiographic findings, or for assessing complications or evidence of mixed infections in patients with known pneumonia who are failing to respond to appropriate therapy [6].

References

- 1.World HealthOrganization Pandemic (H1N1) 2009 - update 60. Laboratory-confirmed cases of pandemic (H1N1) 2009 as officially reported to WHO by States Parties to the IHR (2005), 31 July 2009. Available from: http://www.who.int/csr/don/2009_08_04/en/index.html [Accessed 8 August 2009] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perez-Padilla R, de laRosa-Zamboni D, Ponce deLeon S, the INER., Working Group on Influenza Pneumonia and respiratory failure from swine-origin influenza A (H1N1) in Mexico. N Engl J Med 2009 [Epub ahead of print]. N Engl J Med 2009;361(7):680–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers forDiseaseControlandPrevention Interim guidance on case definitions to be used for investigations of novel Influenza A (H1N1) cases. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/H1N1FLU/casedef.htm [Accessed 6 August 2009] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Novel Swine-OriginInfluenza A., (H1N1) Virus Investigation Team Emergence of a novel swine-origin influenza A (H1N1) virus in humans. N Engl J Med 2009;360:2605–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World HealthOrganization(WHO) Preparing for the second wave: lessons from current outbreaks. Pandemic (H1N1) 2009 briefing note 9. Available at: http://www.who.int/csr/disease/swineflu/notes/h1n1_second_wave_20090828/en/index.html [Accessed 6 September 2009] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reittner P, Ward S, Heyneman L, Johkoh T, Müller NL. Pneumonia: high-resolution CT findings in 114 patients. Eur Radiol 2003;13:515–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]