Cancer-associated retinopathy (CAR), a retinal photoreceptor degeneration disease, is characterised by photopsia and progressive visual loss, and is considered to be related to the presence of malignancy. To our knowledge, CAR related to benign thymoma has not been previously reported. We present a case of CAR associated with benign thymoma. The patient had serum antirecoverin autoantibodies, and his thymoma tissue was positively stained by serum from another patient with CAR containing antirecoverin autoantibodies.

CASE DESCRIPTION

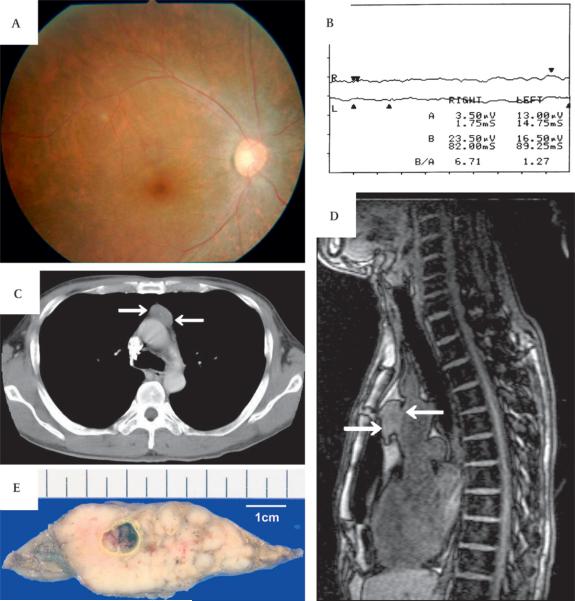

A 47-year-old man noticed quite suddenly visual loss, photopsia and night blindness in August 2003. When he visited our hospital in October 2003, his visual acuity was counting fingers bilaterally, and slit-lamp test revealed normal anterior segments. Funduscopic examination revealed narrowing of the retinal arteries and slight atrophy of retinal pigment epithelium (figure 1A). Goldmann perimetry showed only peripheral islands of vision, and the standard full-field 20 J single flash electroretinogram (ERG) was non-recordable (figure 1B). Chest x-ray, chest CT scanning (figure 1C) and chest MRI (figure 1D) revealed the presence of thymoma, but no other malignancy was found by positron emission tomography scanning. From the serum sample collected at the initial presentation, antirecoverin antibodies were detected by western blotting. The patient received systemic corticosteroid treatment, 1000 mg of methylprednisolone for 3 days, but his vision did not improve. He underwent thymectomy in November 2003, and the encapsulated tumour was removed (figure 1E). Histopathological diagnosis was non-invasive cortical thymoma. He lost light perception 4 months after the onset.

Figure 1.

Clinical features of a 47-year-old male patient with progressive visual loss. (A) Fundus image of the right eye showing narrowing of retinal arteries and retinal pigment epithelium atrophy. (B) Standard full-field 20 J single flash electroretinogram (ERG) after 30 min of dark adaptation, not detectable in both eyes. (C) Chest CT and (D) chest MRI showing a marginal clear solid mass in the anterior mediastinum (arrows). (E) Surgically removed tumour. This was revealed to be an encapsulated non-invasive thymoma.

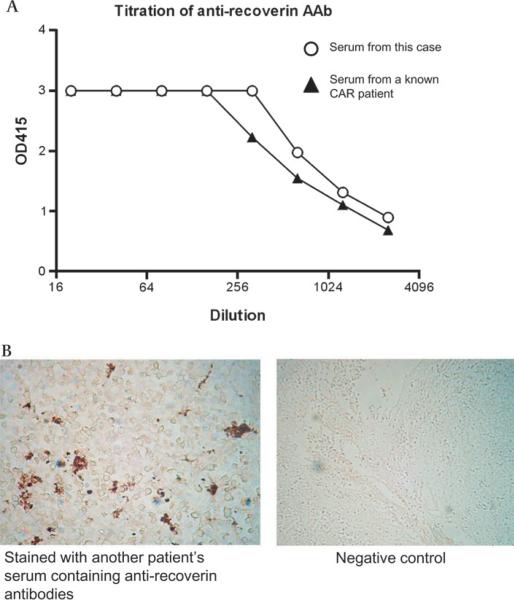

Three years after tumour resection, the patient's serum was again tested for the presence of antiretinal autoantibodies by ELISA using sera from a known antirecoverin CAR patient as a positive control or from a healthy donor as a negative control, and a high titre of antirecoverin autoantibodies was still present (figure 2A). Immunohistochemistry performed on paraffin-embedded sections of the resected tumour revealed a strong staining with serum from another patient with CAR containing antirecoverin antibodies but not with serum from a healthy donor, suggesting the presence of recoverin protein in the thymoma cells (figure 2B). It is therefore assumed that antirecoverin antibodies were initially elucidated against recoverin present in thymoma cells and are now reacting with recoverin present in the retina.

Figure 2.

(A) ELISA of antirecoverin antibodies in the serum. Serum from the patient contains a high titre of antirecoverin antibodies (Abs). Serum from a known CAR patient containing antirecoverin antibody is also tested as a positive control. (B) Immunostaining of the tumour section. Paraffin-embedded sections of the resected tumour were positively stained with serum from another patient with CAR containing antirecoverin antibodies detected by ELISA shown above. When the tissue was stained with serum from healthy donor, no signal was detected.

COMMENT

Immunological findings suggest that recoverin that is present in the thymoma stimulated humoral immunity, and this lead to the production of specific antibodies against recoverin. These antibodies cross-reacted with recoverin in photoreceptor and bipolar cells in the retina. Previous in vivo and in vitro studies have demonstrated reactivity between different cancers and the retina.1,2

Because the thymus is an organ where self-reactive T cells are deleted by negative selection mechanism, thymic medullary epithelial cells produce promiscuous tissue peripheral antigens, including recoverin.3 Such recoverin-producing cells might have clonally expanded and caused overexpression of recoverin, and the high amounts of recoverin in the tumour during cell turnover might have stimulated systemic humoral immunity to produce specific antibodies, although the tumour was benign and encapsulated.

There are a few reports on patients with CAR-like autoimmune retinopathy with serum antirecoverin antibodies but no underlying malignancies.4 It is possible that non-malignant tumours originate the production of these autoantibodies, so even a benign tumour should not be ignored and should be immunopathologically examined to investigate the ectopic expression of retina-specific proteins. Although the second blood sampling was performed 3 years after thymectomy, a high titre of antirecoverin antibodies was still detected. It is assumed that once antirecoverin autoantibodies were produced, thymectomy could not stop the progression of the disease, suggesting the role of autoantibodies in pathogenicity of retinopathy. From the experience of antibody testing in the Ocular Immunology Laboratory, autoantibodies against recoverin were not detected in normal patients without visual problems, only in patients with CAR or cancer.5 Further studies are required to evaluate treatments of patients with CAR possibly by blocking neutralising retina-specific antibodies or blocking cascades of apoptotic signals in retinal cells. Treating a patient with CAR using monoclonal antibody (Ab) against pan-lymphocyte antigen, CD52,6 suggests the importance of modulating the immune system to treat patients with CAR.

Footnotes

Competing interests None.

Ethics approval Ethics approval was provided by the Tokyo Medical and Dental University Ethics Commitee.

Patient consent Obtained.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed

REFERENCES

- 1.Maeda T, Maeda A, Maruyama I, et al. Mechanisms of photoreceptor cell death in cancer-associated retinopathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001;42:705–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adamus G, Webb S, Shiraga S, et al. Anti-recoverin antibodies induce an increase in intracellular calcium, leading to apoptosis in retinal cells. J Autoimmun. 2006;26:146–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2005.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Takase H, Yu CR, Mahdi RM, et al. Thymic expression of peripheral tissue antigens in humans: a remarkable variability among individuals. Int Immunol. 2005;17:1131–40. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mizener JB, Kimura AE, Adamus G, et al. Autoimmune retinopathy in the absence of cancer. Am J Ophthalmol. 1997;123:607–18. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)71073-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adamus G. Autoantibody targets and their cancer relationship in the pathogenicity of paraneoplastic retinopathy. Autoimmun Rev. 2009;8:410–14. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Espandar L, O'Brien S, Thirkill C, et al. Successful treatment of cancer-associated retinopathy with alemtuzumab. J Neurooncol. 2007;83:295–302. doi: 10.1007/s11060-006-9326-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]