Abstract

Sildenafil is a cGMP-specific phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitor that augments cGMP accumulation following the activation of soluble guanylate cyclase (sGC). In this study, we investigated whether sildenafil promotes the production of the sGC-stimulatory gases, carbon monoxide and nitric oxide, by stimulating the expression of the inducible isoforms of heme oxygenase (HO-1) and nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) in vascular smooth muscle cells (SMCs). Sildenafil increased HO-1 expression and potentiated cytokine-mediated expression of iNOS and NO synthesis by SMCs. The induction of HO-1 was unaffected by the sGC inhibitor 1H-(1,2,4)oxadiazolo[4,3-α]quinozalin-1-one (ODQ) or the (9S,10R,12R)-2,3,9,10,11,12-hexahydro-10-methoxy-2,9-dimethyl-1-oxo-9,12-epoxy-1H-diindol91,2,3-fg:3′,2′,1′-kl)pyrrolo(3,4-i)benzodiazocine-10-carboxylic acid, methyl ester (KT 5823). However, the sildenafil-mediated increase in HO-1 promoter activity was abolished by mutating the antioxidant responsive elements in the promoter or by overexpressing a dominant-negative mutant of NF-E2-related factor-2 (Nrf2). Furthermore, the induction of HO-1 by sildenafil was accompanied by an increase in reactive oxygen species (ROS) and blocked by N-acetyl-L-cysteine and rotenone. In contrast, the enhancement of cytokine-stimulated NO synthesis by sildenafil was prevented by ODQ and the protein kinase A inhibitor (9S,10S,12R)-2,3,9,10,11,12-hexahydro-10-hydroxy-9-methyl-1-oxo-9,12-epoxy-1H-diindolo(1,2,3-fg:3′,2′,1′-kl)pyrrolo(3,4-i)(1,6)benzodiazocine-10-carboxylic acid hexyl ester (KT 5720) and duplicated by lipophilic analogues of cGMP. In conclusion, these studies demonstrate that sildenafil stimulates the expression of HO-1 and iNOS via the ROS-Nrf2 and sGC-cGMP pathway, respectively. The ability of sildenafil to block the catabolism of cGMP while stimulating the synthesis of sGC-stimulatory gaseous monoxides through the induction of HO-1 and iNOS provides a potent mechanism by which cGMP-dependent vascular actions of this drug are amplified.

Keywords: heme oxygenase, inducible nitric oxide synthase, vascular smooth muscle cells

1. Introduction

Sildenafil is a potent and selective inhibitor of cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP)-specific phosphodiesterase type 5 (PDE-5) that is widely used for the treatment of erectile dysfunction [1]. Sildenafil is also approved for the management of pulmonary arterial hypertension and shows considerable promise in other cardiovascular disease states, including ischemia-reperfusion injury, myocardial infarction, cardiac hypertrophy, heart failure, and stroke [2,3]. The target of sildenafil, PDE-5, is widely expressed in many tissues and cells but it is highly enriched in smooth muscle cells (SMCs) [4,5]. PDE-5 catalyzes the breakdown of cGMP that is generated following the activation of guanylate cyclase by gaseous monoxides and natriuretic peptides [6]. By inhibiting PDE-5 activity, sildenafil increases intracellular cGMP levels in vascular SMCs leading to prominent decreases in blood vessel tone, especially in the venous system of the corpus cavernosum and the pulmonary vasculature [4,7]. In addition, sildenafil inhibits the proliferation of vascular SMCs by promoting the activation of cGMP-dependent protein kinase G (PKG), which suppresses multiple mitogenic signaling pathways [8,9].

The diatomic gases nitric oxide (NO) and carbon monoxide (CO) are important physiologic activators of soluble guanylate cyclase in vascular SMCs. CO is generated by the enzyme heme oxygenase (HO), which oxidatively degrades heme into equimolar amounts of CO, biliverdin and iron . Two discrete isoforms of HO, HO-1 and HO-2, are expressed by SMCs. While HO-2 is largely constitutively expressed, HO-1 is a highly inducible isoform that is activated by numerous biochemical and biophysical stimuli [see 10,11]. Alternatively, NO is predominantly produced in vascular SMCs via the oxidation of arginine to citrulline by the enzyme inducible NO synthase (iNOS). This dimeric enzyme is induced by various inflammatory mediators and generates substantial amounts of NO over a sustained interval of time [12]. Both gases bind to soluble guanylate cyclase causing conformation changes in the enzyme that dictates their unique ability to stimulate enzyme activity [13]. Although CO is a much weaker activator of soluble guanylate cyclase compared to NO, CO elicits potent cGMP-mediated effects. As seen with NO, CO inhibits vascular tone, vascular SMC proliferation, and platelet aggregation in a cGMP-dependent fashion [14-17].

Although sildenafil can potentiate the biological actions of gaseous monoxides by preventing the degradation of cGMP in vascular SMCs, the ability of this PDE-5 inhibitor to stimulate the synthesis of gaseous monoxides has not been explored in these cells. In the current study, we investigated the role of sildenafil in modulating the expression of HO-1 and iNOS in vascular SMCs. Furthermore, we identified signaling pathways that are activated by sildenafil that modulate the expression of these gas-producing enzymes. The ability of sildenafil to coordinately induce the expression of enzymes capable of generating soluble guanylate cyclase-activating gases while simultaneously blocking the hydrolysis of cGMP may provide a novel mechanism by which this drug is able to amplify cGMP-dependent vascular responses. Moreover, the induction of HO-1 and iNOS by sildenafil may contribute to the emerging pleiotropic actions of this therapeutic agent.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Materials

Minimum essential medium, streptomycin, penicillin, actinomycin D, N-acetyl-L-cysteine, L-glutamine, Tes, Tris, HEPES, collagenase, Triton X-100, elastase, 8-bromo-cGMP, dibutyryl cGMP, sildenafil, DT-2, sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), glycerol, nitrite, rotenone, phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), formaldehyde, mercaptoethanol, and bromophenol blue were from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Bovine calf serum, 5-(and-6)-chloromethyl-2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate acetyl ester (CM-H2-DCFDA), and MitoSOX Red reagent were from Invitrogen Corporation (Carlsbad, CA). Interleukin-1β was from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). Tumor necrosis factor-α was from Genzyme (Boston, MA). KT-5823, KT-5720, and 1 H-(1,2,4)oxadiazolo[4,3-α]quinozalin-1-one (ODQ) were from Calbiochemical (San Diego, CA). A polyclonal antibody against HO-1 was from Assay Designs (Ann Arbor, MI). A polyclonal antibody against iNOS was from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA) while antibodies against NF-E2-related factor-2 (Nrf2) and β-actin, and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Antibodies against vasodilator-activated stimulated phosphoprotein (VASP) and phospho-VASP (Ser239) were from Cell Signaling Technologies (Danvers, MA). Dowex 50W-X8 and nitrocellulose were from Bio-Rad Laboratories (Hercules, CA). α-[32P]dCTP (3000 Ci/mmol) was from Amersham Life Sciences (Arlington Heights, IL) and [3H]L-arginine (43 Ci/mmol) was from Perkin Elmer (Boston, MA).

2.2 Cell culture

Vascular SMCs were isolated by collagenase and elastase digestion of rat thoracic aortas and characterized by morphological and immunological criteria, as we previously described [18]. Cells were cultured serially in minimum essential media supplemented with 10% bovine serum, 2 mM L-glutamine, 5 mM Tes, 5mM Hepes, 100U/ml penicillin, and 100U/ml streptomycin. Cells were propagated at 37°C in an atmosphere of 95% air and 5% CO2, and used between passages 6 and 21.

2.3 Western blotting

Vascular SMCs were collected in lysis buffer (125mM Tris, pH 6.8, 12.5% glycerol, 2% SDS), sonicated, spiked with bromophenol blue, and proteins separated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. The separated proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, blocked with PBS and non-fat (5%) milk, and incubated with antibodies directed against HO-1 (1:1000), iNOS (1:200), phospho-VASP (1:150), VASP (1:250), Nrf2 (1:85), and β-actin (1:200) overnight at 4°C. Membranes were then washed in PBS, incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies and developed with commercial chemoluminescence reagents (Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL). Blots were then stripped of antibodies at 50°C for 30 minutes using a stripping solution consisting of 10% SDS and 100mM mercaptoethanol in 62.5mM Tris buffer, pH 6.8, before reprobing with complementary antibodies. Protein expression was quantified by densitometry and normalized with respect to β-actin or VASP.

2.4 Northern blotting

Total RNA was isolated from vascular SMCs with Trizol (Invitrogen, Corporation, Carlsbad, CA) and fractionated on 1.2% agarose gels containing formaldehyde. RNA was transferred to Gene Screen Plus membranes (Perkin Elmer Life Sciences, Waltham, MA) and prehybridized at 68°C for 4 hours in rapid hybridization buffer (Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL). Membranes were then hybridized at 68°C overnight with buffer containing [32P]DNA probes for HO-1 mRNA or 18S rRNA. DNA probes were generated by RT-PCR and labeled with α-[32P]dCTP using a random primer kit (Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL), as previously described [19,20]. Following hybridization, membranes were washed, exposed to X-ray film, and densitometry performed on autoradiographs to quantitate HO-1 mRNA expression relative to 18S rRNA.

2.5 Heme oxygenase-1 promoter analysis

HO-1 promoter activity was measured using promoter/firefly luciferase constructs that were generously provided by Dr. Jawed Alam (Ochner Clinic Foundation, New Orleans, LA). These constructs consisted of the wild type enhancer (E1) that contains three antioxidant responsive element (AREs) core sequences linked to a minimum HO-1 promoter and a mutant enhancer (M739) that has mutations in each of the three ARE sequences [21]. A plasmid expressing a dominant-negative mutant (dnNrf2) was also employed in some experiments. Transfection efficiency was determined by introducing a plasmid encoding Renilla luciferase (hRluc/TK; Promega, Madison, WI) in all cells. SMCs were transfected with plasmids using lipofectamine (Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, CA) for 48 hours and then treated with sildenafil. Cells were lysed and luciferase activity measured using the Promega Dual-Light assay system and a Glomax luminometer (Promega, Madison, WI). Firefly luciferase activity was normalized with respect to Renilla luciferase activity and expressed relative to control cells.

2.6 Intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) and mitochondrial superoxide production

ROS production was monitored using the cell permeable probe CM-H2-DCFDA, as we previously reported [20]. Vascular SMCs grown on glass cover slips were incubated with dye (5μM) for 30 minutes at 37°C. Dye-loaded cells were then washed with PBS and fluorescence images obtained with a Bio-Rad Radiance 2000 confocal system coupled to an inverted microscope using excitation and emission wavelengths of 480 nm and 520 nm, respectively. Mitochondrial superoxide production was measured in live vascular SMCs using MitoSOX Red reagent (514 nm excitation/585 nm emission). MitoSOX Red is a mitochondria-targeted form of dihydroethidium that undergoes oxidation in the organelle to form the DNA-binding red fluorophore ethidium bromide. Cells were loaded with MitoSOX Red (2.5μM) for 20 minutes, washed with PBS, and images obtained by confocal microscopy (Zeiss LSM 510; Carl Zeiss Incorporated, Thornwood, NY). For both probes, mean fluorescence intensity per image was quantified by Image J analysis software (NIH, Bethesda, MD).

2.7 NO synthase (NOS) activity

NOS activity was determined by measuring the conversion of [3H]L-arginine to [3H]citrulline , as we have previously described [22]. Vascular SMCs were incubated with [3H]L-arginine (1μCi)-containing culture media for 4 hours after which radiolabel-containing media were removed and cells washed three times with PBS. Cells were then lysed with ice-cold Tris buffer, pH 7.4, containing Triton X-100 (0.1%), collected, and centrifuged at 1,000 x g for 1 minute. Supernatants were then applied to the cation exchange resin Dowex 50W-X8 and neutrally charged L-citrulline eluted and quantified by liquid scintillation counting.

2.8 NO synthesis

NO synthesis was determined by measuring the accumulation of nitrite in the culture media, as we previously described [18]. Aliquots of culture medium were mixed with an equal volume of Griess reagent (Promega, Madison, WI), incubated at room temperature for 10 minutes, and absorbance measured at 540 nm. Concentrations were determined relative to a standard curve obtained using aqueous solutions of nitrite.

2.9 Statistics

Results were expressed as means ± SEM. Data were analyzed using SigmaStat 3.1 (Systat Software Incorporated, San Jose, CA). Comparisons between treatment groups were made using a Student’s two-tailed t-test or an analysis of variance with post-hoc Bonferroni testing when multiple groups were compared. A P value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

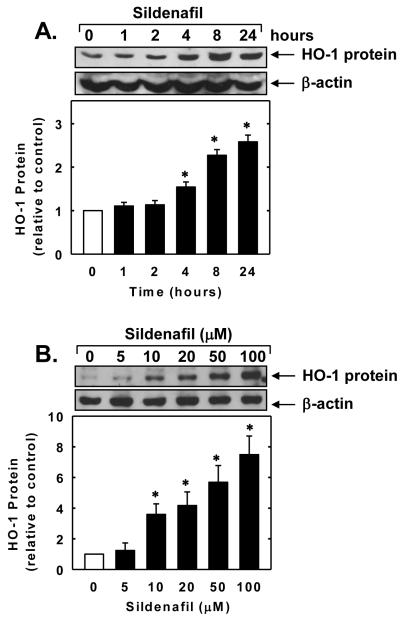

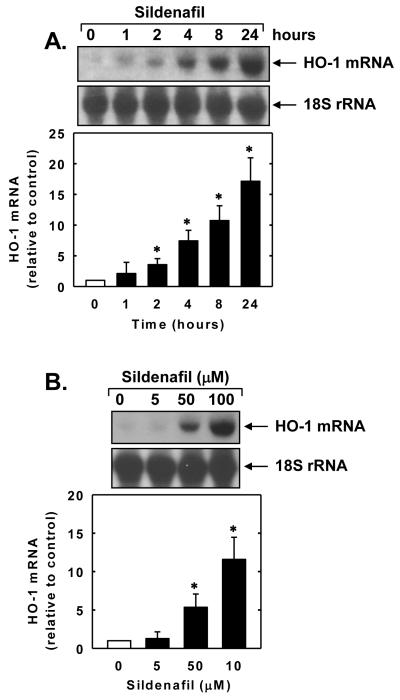

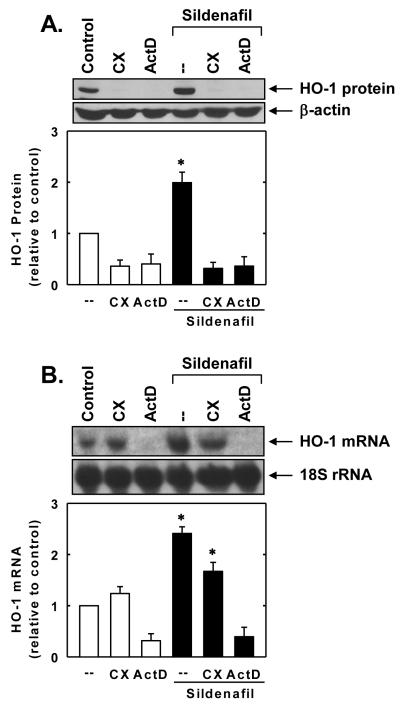

Treatment of vascular SMCs with sildenafil stimulated a time- and concentration-dependent increase in HO-1 protein. The induction of HO-1 protein by sildenafil was delayed, with a significant increase in HO-1 protein appearing 4 hours after sildenafil administration, and levels remained elevated for 24 hours (Figure 1A). An increase in HO-1 protein was detected after 24 hours with 10μM of sildenafil and higher concentrations of sildenafil resulted in a progressive increase in HO-1 protein (Figure 1B). In addition, sildenafil stimulated a concentration-dependent rise in HO-1 mRNA expression that preceded the increase in HO-1 protein (Figure 2A and B). A significant and progressive increase in HO-1 mRNA was first detected after 2 hours of sildenafil exposure. Incubation of vascular SMCs with the transcriptional inhibitor actinomycin D abolished basal and sildenafil-induced HO-1 mRNA and protein expression (Figure 3A and B). In contrast, the protein synthesis inhibitor cycloheximide had no effect on basal or sildenafil-mediated increases in HO-1 mRNA but it completely blocked HO-1 protein expression in the absence or presence of sildenafil (Figure 3A and B).

Figure 1.

Sildenafil stimulates HO-1 protein expression in vascular SMCs. A. Time-course of HO-1 protein expression following the administration of sildenafil (50μM). B. Concentration-dependent effect of sildenafil (5-100μM for 24 hours) on HO-1 protein expression. HO-1 protein was quantified by densitometry, normalized with respect to β-actin, and expressed relative to that of control, untreated cells. Results are means ± SEM (n=3). *Statistically significant effect of sildenafil (P<0.05).

Figure 2.

Sildenafil stimulates HO-1 mRNA expression in vascular SMCs. A. Time-course of HO-1 mRNA expression following the administration of sildenafil (100μM). B. Concentration-dependent effect of sildenafil (5-100μM for 24 hours) on HO-1 mRNA expression. HO-1 mRNA was quantified by densitometry, normalized with respect to 18 S rRNA, and expressed relative to that of control, untreated cells. Results are means ± SEM (n=3). *Statistically significant effect of sildenafil (P<0.05).

Figure 3.

Sildenafil-mediated HO-1 gene expression in vascular SMCs requires de novo RNA synthesis. A. Effect of actinomycin D (ActD;2μg/ml) or cycloheximide (CX;5μg/ml) on sildenafil (50μM for 24 hours)-mediated increase in HO-1 protein. B. Effect of ActD (2μg/ml) or CX (5μg/ml) on sildenafil (50μM for 8 hours)-mediated increase in HO-1 mRNA. HO-1 protein and mRNA expression were quantified by densitometry, normalized with respect to β-actin or 18 S rRNA, respectively, and expressed relative to that of control, untreated cells. Results are means ± SEM (n=3). *Statistically significant effect of sildenafil (P<0.05).

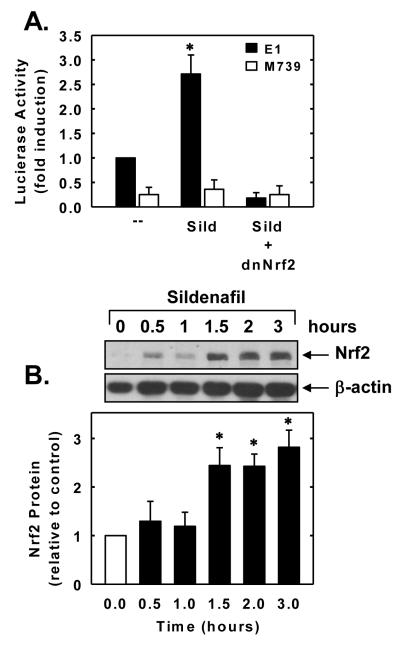

To further examine the molecular mechanism by which sildenafil induces HO-1 gene expression, vascular SMCs were transiently transfected with an HO-1 promoter construct and reporter activity monitored. Treatment of SMCs with sildenafil stimulated an increase in HO-1 promoter activity that was abolished by mutating the antioxidant responsive element (ARE) sequences in the promoter (Figure 4A). Mutation of the ARE sequences also reduced basal promoter activity. Since the transcription factor Nrf2 plays a major role in ARE-mediated gene activation, we explored whether Nrf2 contributes to the activation of HO-1 by sildenafil. Transfection of SMCs with a dominant-negative mutant that had its activation domain deleted inhibited the sildenafil-mediated elevation in HO-1 promoter activity. Furthermore, sildenafil evoked a rapid increase in Nrf2 protein expression beginning 1.5 hours after sildenafil exposure (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Sildenafil stimulates HO-1 promoter activity and Nrf2 expression in vascular SMCs. A. Sildenafil stimulated HO-1 promoter activity. Cells were transfected with a HO-1 promoter construct (E1) or a mutated HO-1 promoter construct (M739) and a Renilla luciferase construct, treated with sildenafil (Sild; 100μM for 6 hours), and then analyzed for luciferase activity. In some instances, a dominant-negative Nrf2 (dnNrf2) construct was co-transfected into cells. B. Time-course of Nrf2 protein expression after administration of sildenafil (100μM). Protein expression was quantified by scanning densitometry, normalized with respect to β-actin, and expressed relative to that of control, untreated cells. Results are means ± SEM (n=3-5). *Statistically significant effect of sildenafil (P<0.05).

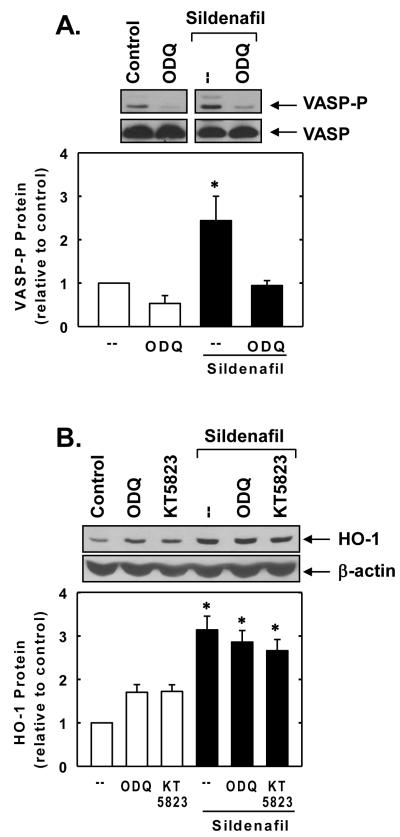

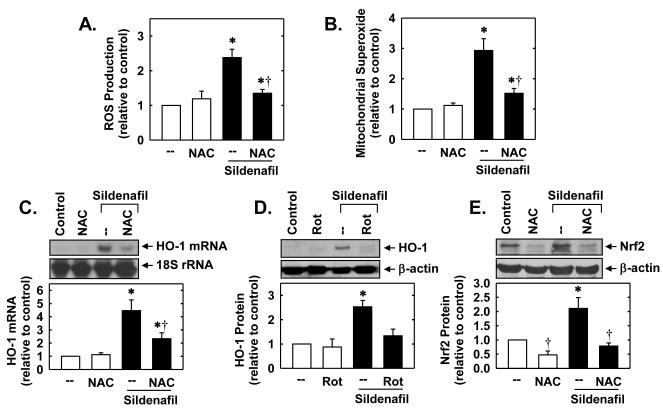

In subsequent experiments, we sought to determine the upstream signaling pathways that are responsible for stimulating Nrf2 and HO-1 expression. Because the biological actions of sildenafil on vascular SMCs are largely dependent on the generation of cGMP by soluble guanylate cyclase, the role of this enzyme was examined. Treatment of SMCs with sildenafil enhanced cGMP-dependent signaling, as evidenced by the specific phosphorylation of VASP, a downstream target of PKG (Figure 5A). Although the soluble guanylate cyclase cylase inhibitor ODQ blocked the phosphorylation of VASP by sildenafil (Figure 5A), it had no effect on the sildenafil-mediated induction of HO-1 (Figure 5B). In addition, the PKG inhibitor KT 5823 failed to prevent the sildenafil-mediated induction of HO-1 protein. Since oxidative stress is a well characterized activator of Nrf2 [23,24], the role of reactive oxygen species (ROS) was investigated. Interestingly, treatment of vascular SMCs with sildenafil stimulated an increase in intracellular ROS and mitochondrial superoxide production that was prevented by the glutathione donor, N-acetyl-L-cysteine (Figure 6A and B). In addition, the sildenafil-mediated increase in HO-1 expression was blocked by N-acetyl-L-cysteine or rotenone (Figure 6C and D). N-Acetyl-L-cysteine also inhibited the induction of Nrf2 protein by sildenafil (Figure 6E).

Figure 5.

Sildenafil stimulates HO-1 expression in a soluble guanylate cyclase and protein kinase G (PKG)-independent manner. A. Effect of the soluble guanylate cyclase inhibitor ODQ (30μM) on the sildenafil (100μM)-mediated phosphorylation of the PKG substrate, VASP. B. Effect of ODQ (30μM) or the PKG inhibitor KT 5823 (10μM) on sildenafil (100μM for 24 hours)-mediated induction of HO-1 protein. Protein expression or phosphorylation were quantified by densitometry, normalized with respect to β-actin or VASP, respectively, and expressed relative to that of control, untreated cells. Results are means ± SEM (n=3). *Statistically significant effect of sildenafil (P<0.05).

Figure 6.

Sildenafil-mediated HO-1 expression in vascular SMCs is dependent on oxidative stress. A. Effect of sildenafil (100 μM for 6 hours) on the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in the absence and presence of N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC; 10mM). B. Effect of sildenafil (100 μM for 6 hours) on mitochondrial superoxide production in the absence and presence of NAC (10mM). C. Effect of NAC (10mM) on sildenafil (100μM for 24 hours)-mediated HO-1 mRNA expression. D. Effect of rotenone (Rot; 5μM) on sildenafil (100μM for 24 hours)-mediated HO-1 protein expression. E. Effect of NAC (10mM) on sildenafil (100μM for 2 hours)-mediated Nrf2 protein expression. Protein and mRNA expression were quantified by densitometry, normalized with respect to β-actin or 18 S rRNA, respectively, and expressed relative to that of control, untreated cells. Results are means ± SEM (n=4-6). *Statistically significant effect of sildenafil (P<0.05). †Statistically significant effect of NAC (P<0.05).

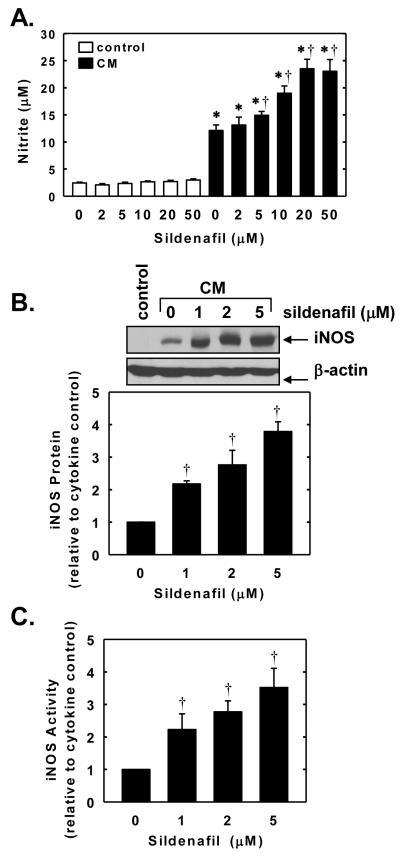

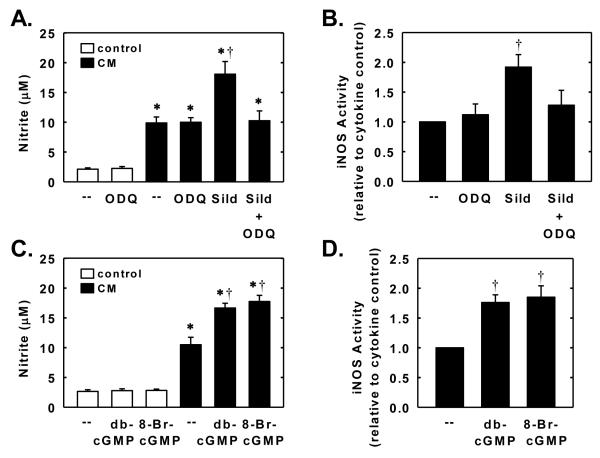

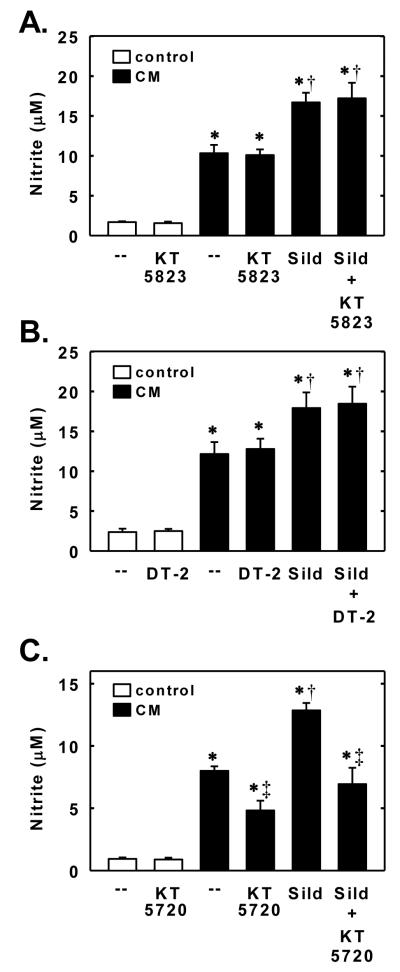

In the next series of experiments, we investigated whether sildenafil also regulates the expression of a NO-generating enzyme. Control, untreated SMCs produce minimal amounts of nitrite; however, treatment of cells with a cytokine mixture containing interleukin-1β and tumor necrosis factor-α resulted in a significant increase in nitrite production (Figure 7A). The cytokine-mediated rise in nitrite synthesis by vascular SMCs was accompanied by the induction of iNOS protein and activity (Figure 7B and C). Interestingly, simultaneous addition of sildenafil potentiated the cytokine-mediated increase in nitrite production, iNOS protein expression, and iNOS activity. The potentiating effect of sildenafil was concentration-dependent. A significant elevation in iNOS protein and activity by sildenafil was first noted at a concentration of 1μM while higher concentrations of sildenafil (>5μM) were required to augment nitrite synthesis (Figure 7A, B, and C). The ability of sildenafil to enhance cytokine-mediated nitrite production or iNOS activity was dependent on soluble guanylate cyclase activity because it was abolished by ODQ (Figure 8A and B). In addition, lipophilic analogues of cGMP, dibutyryl cGMP and 8-bromo-cGMP, potentiated the cytokine-mediated increase in nitrite production and iNOS activity but had no effect on nitrite synthesis in the absence of cytokines (Figure 8C and D). Finally, we investigated the role of downstream protein kinases in mediating the augmentation of nitrite synthesis by sildenafil. Treatment of vascular SMCs with the PKG inhibitor KT 5823 or DT-2 had no effect on basal or cytokine-induced nitrite formation, and did not modify the sildenafil-mediated increase in nitrite formation by cytokine-treated cells (Figure 9A and B). In contrast, the protein kinase A inhibitor KT 5720 diminished the cytokine-mediated increase in nitrite synthesis and abrogated the ability of sildenafil to augment cytokine-mediated nitrite synthesis without affecting the basal production of nitrite (Figure 9C).

Figure 7.

Sildenafil potentiates cytokine-mediated NO synthesis and iNOS expression and activity in vascular SMCs. A. Effect of sildenafil (2-50μM) on nitrite accumulation after treatment of cells with a cytokine mixture (CM) consisting of interleukin-1β (5ng/ml) and tumor necrosis factor-α (5ng/ml) for 24 hours. B. Effect of sildenafil (1-5μM) on iNOS protein expression after treatment of cells with a CM for 24 hours. C. Effect of sildenafil (1-5μM) on iNOS protein activity after treatment of cells with a CM for 24 hours. Results are means ± SEM (n=4-6). *Statistically significant effect of CM (P<0.01). †Statistically significant effect of sildenafil (P<0.05).

Figure 8.

Sildenafil potentiates cytokine-mediated NO synthesis and iNOS activity in a soluble guanylate cyclase-dependent manner. A. Effect of soluble guanylate cyclase inhibitor ODQ (30μM) on the stimulatory effect of sildenafil (5μM) on nitrite production after treatment of cells with a cytokine mixture (CM) consisting of interleukin-1β (5ng/ml) and tumor necrosis factor-α (5ng/ml) for 24 hours. B. Effect of soluble guanylate cyclase inhibitor ODQ (30μM) on the stimulatory effect of sildenafil (5μM) on nitrite production after treatment of cells with a CM for 24 hours. C. Effect of dibutyryl cGMP (db-cGMP; 500μM) or 8-bromo-cGMP (8-Br-cGMP; 200μM) on nitrite production in the presence and absence of CM for 24 hours. D. Effect of db-cGMP (500μM) or 8-Br-cGMP (200μM) on nitrite production in the presence and absence of CM for 24 hours. Results are means ± SEM (n=4-5). *Statistically significant effect of CM (P<0.01). †Statistically significant effect of sildenafil or cGMP analogues (P<0.05).

Figure 9.

Sildenafil potentiates cytokine-mediated NO synthesis in a PKA-dependent manner. Effect of the PKG inhibitor KT 5823 (10μM) on the stimulatory effect of sildenafil (Sild; 5μM) on nitrite production after treatment of cells with a cytokine mixture (CM) consisting of interleukin-1β (5ng/ml) and tumor necrosis factor-α (5ng/ml) for 24 hours. B. Effect of the PKG inhibitor DT-2 (10μM) on the stimulatory effect of Sild (5μM) on nitrite production after treatment of cells with a CM for 24 hours. C. Effect of the PKA inhibitor KT 5720 (10μM) on the stimulatory effect of Sild (5μM) on nitrite production after treatment of cells with a CM for 24 hours. Results are means ± SEM (n=5-7). *Statistically significant effect of CM (P<0.01). †Statistically significant effect of sildenafil (P<0.05). ‡Statistically significant effect of KT 5720 (P<0.05).

4. Discussion

In the present study, we identified sildenafil as a novel inducer of HO-1 and iNOS protein expression in vascular SMCs. Interestingly, sildenafil induces the expression of these two enzymes via distinct signaling pathways. The sildenafil-mediated induction of HO-1 is redox-sensitive and relies on the activation of Nrf2, while sildenafil-mediated increases in iNOS expression depend on the activation of the sGC-cGMP signaling cascade. The finding that sildenafil stimulates the expression of enzymes that generate the sGC-activating gases NO and CO combined with its previously recognized ability to block cGMP degradation may serve a critical amplification process by which sildenafil augments cellular cGMP levels and regulates vascular SMC function. Furthermore, the induction of HO-1 and iNOS by sildenafil may also contribute to the pleiotropic actions of this drug.

Our finding that sildenafil stimulates HO-1 gene expression in vascular SMCs extends an earlier report [25] showing that sildenafil evokes an increase in HO-1 protein in cultured endothelial cells and is consistent with previous in vivo studies demonstrating that oral administration of sildenafil elevates HO-1 protein and activity in cavernous tissues of rats [26,27]. However, the mechanism by which sildenafil stimulates HO-1 expression in these tissues remains unresolved. In vascular SMCs, we found that the induction of HO-1 mRNA by sildenafil is dependent on de novo RNA synthesis, as the transcriptional inhibitor actinomycin D blocked the increase in HO-1 expression. In contrast, the induction of HO-1 mRNA is independent of protein synthesis, since HO-1 mRNA expression is largely preserved in the presence of cycloheximide. In addition, sildenafil stimulates a significant increase in HO-1 promoter activity. The sildenafil-mediated increase in HO-1 promoter activity is dependent on the presence of AREs, as mutation of these response elements prevents the increase in promoter activity. Given the predominant role of Nrf2 in triggering ARE-dependent HO-1 gene transcription [28], we investigated the involvement of this transcription factor in mediating the induction of HO-1. Indeed, sildenafil stimulates a rapid rise in Nrf2 expression that parallels the induction of HO-1 mRNA expression. Moreover, transfection of SMCs with a dominant-negative Nrf2 construct abolishes the activation of HO-1 promoter activity in response to sildenafil. Thus, the mobilization of Nrf2 plays a fundamental role in mediating HO-1 gene expression by sildenafil and provides a novel pathway by which this drug can stimulate mammalian gene expression.

Interestingly, the sildenafil-mediated induction of HO-1 does not involve soluble guanylate cyclase. Although sildenafil promotes cGMP signaling in vascular SMCs, as reflected by the specific phosphorylation of the PKG substrate, VASP, the soluble guanylate cyclase inhibitor, ODQ, fails to prevent the induction of HO-1 while completely blocking the phosphorylation of VASP in response to sildenafil. Moreover, the PKG inhibitor KT 5823 has no effect on the induction of HO-1 by sildenafil. These findings are consistent with previous work from our laboratory showing that cGMP does not stimulate HO-1 gene transcription in vascular SMCs [29]. Surprisingly, the induction of HO-1 by sildenafil is dependent on oxidative stress. Treatment of vascular SMCs with sildenafil stimulates a significant increase in intracellular ROS production. Significantly, administration of the glutathione donor N-acetyl-L-cysteine attenuates the sildenafil-mediated generation of reactive oxygen and the induction of HO-1 in vascular SMCs. While sildenafil has been shown to exert antioxidant effects in some experimental systems [30,31], pro-oxidant effects of sildenafil have also been reported in monocytes and tumor cells [32,33]. Although the mechanism by which sildenafil stimulates oxidative stress is not known, a mitochondrial pathway has been proposed [34]. Consistent with this notion, we found that sildenafil stimulates mitochondrial superoxide production in vascular SMCs. Moreover, the sildenafil-mediated increase in HO-1 expression is blocked by the mitochondrial electron transport chain complex I inhibitor rotenone, further implicating this organelle with the induction of HO-1 by sildenafil. The mechanism by which sildenafil activates Nrf2 is unclear but it likely involves the oxidation of cysteine residues in Keap1 since several cysteine residues undergo redox-dependent alterations that result in the release and/or blockade of Keap1-dependent ubiquitination and catabolism of Nrf2 [23,34]. Indeed, we found that N-acetyl-L-cysteine inhibits the expression of Nrf2 by sildenafil.

Aside from stimulating HO-1 expression, sildenafil promotes the expression of the NO-generating enzyme iNOS in vascular SMCs. Alone, sildenafil does not stimulate iNOS protein expression or NO synthesis, but it markedly increases iNOS protein and activity, and NO formation by a combination of inflammatory cytokines. However, in this case, the enhancement of iNOS activity and NO production by sildenafil is dependent on soluble guanylate cyclase activity because inhibition of soluble guanylate cyclase by ODQ abrogates the elevation in NO synthesis. In addition, lipophilic analogs of cGMP mimic the ability of sildenafil to enhance cytokine-mediated iNOS activity and NO synthesis. Interestingly, the sildenafil-mediated increases in NO formation is not mediated by PKG since inhibition of this kinase by two distinct inhibitors fails to inhibit the stimulatory effect of sildenafil on NO synthesis. Since cGMP can also lead to the activation of PKA [35], the role of this kinase in raising NO synthesis was explored. In fact, incubation of SMCs with the PKA inhibitor KT 5720 abolishes the sildenafil-mediated increase in NO synthesis in cytokine-exposed cells. These results are in-line with earlier reports showing that PKA mediates the augmentation of cytokine-induced NO generation in vascular SMCs by activators of guanylate cyclase [36,37]. Furthermore, the ability of KT 5720 to suppress NO synthesis following cytokine treatment is consistent with a previous study showing a critical role for PKA in mediating the induction of iNOS by cytokines [38]. Our finding that sildenafil promotes the induction of iNOS in vascular SMCs is in agreement with in vivo and in vitro studies showing that sildenafil increases iNOS expression in cardiac myocytes [39,40] but contrasts with other reports demonstrating that sildenafil decreases iNOS expression in microglial and tumor cells [41,42]. The discrepancy between studies may reflect differences in cell type, culture conditions, and/or type of inflammatory stimuli.

The ability of sildenafil to stimulate the production of gaseous monoxides via the induction of HO-1 and iNOS may be of pharmacological relevance. The concentration of sildenafil (>1μM) required to induce iNOS protein expression and activity is achieved in the plasma of adult male patients given a single high oral dose of sildenafil [43]. While the concentration of sildenafil needed to stimulate HO-1 expression is higher (>10μM) than plasma concentrations normally attained in patients following oral sildenafil administration, advanced age, renal dysfunction, hepatic cirrhosis, and drug-induced impairment in liver metabolism can significantly increase circulating sildenafil levels [44]. Moreover, plasma drug concentrations do not always reflect the intracellular concentration of the drug which could be substantially higher due to cell or tissue specific accumulation. Despite the high concentration of sildenafil needed to stimulate HO-1 expression in our cultured vascular cells, sildenafil is an effective inducer of HO-1 in vivo. Oral ingestion of clinically relevant concentrations of sildenafil is sufficient to elevate HO-1 expression in rodents [26,27]. Interestingly, biomechanical forces generated by blood flow can increase the sensitivity of vascular cells to pharmacological inducers of HO-1, providing a potential mechanism whereby the potency of sildenafil is enhanced in vivo (45).

The upregulation of CO and NO synthesis by sildenafil may also be of therapeutic significance since it provides an amplification mechanism by which sildenafil elevates tissue cGMP levels. Consistent with this notion, the efficacy of sildenafil is substantially diminished when gas-generating enzymes are inhibited or deleted in cavernous or pulmonary tissues [27,46-48]. Interestingly, the induction of HO-1 and iNOS may also underlie new emerging uses for sildenafil in cardiovascular disease. In particular, the powerful preconditioning-like effect of sildenafil against myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury may involve HO-1 and iNOS since both enzymes have been implicated as downstream effectors of the preconditioning response [49,50]. Furthermore, sildenafil’s ability to improve survival and cardiac function following myocardial infarction in rodents may involve the induction of HO-1 since gene delivery of this protein evokes similar protective responses in animals [51,52]. Finally, since both HO-1 and iNOS can influence vascular function in a soluble guanylate cyclase-independent manner, the induction of these proteins by sildenafil may underlie the emerging pleiotropic effects of this drug.

In conclusion, these studies demonstrate that sildenafil stimulates the expression of HO-1 and iNOS in vascular SMCs via the ROS-Nrf2 and sGC-cGMP pathways, respectively. The ability of sildenafil to stimulate the production of the soluble guanylate cyclase-activating gases CO and NO by inducing the expression of HO-1 and iNOS while preventing the catabolism of cGMP may serve to amplify cGMP-dependent biological responses in vascular SMCs. Furthermore, the induction of HO-1 and iNOS by sildenafil may contribute to novel beneficial actions of this drug in the cardiovascular system.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health Grants HL59976 and HL74966.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Boolell M, Allen MG, Ballard SA, Gepi-Atti S, Muirhead GJ, Naylor AM, Osterloh IH, Gingell C. Sildenafil: an orally active type 5 cyclic nucleotide cGMP-specific phosphodiesterase inhibitor for the treatment of penile erectile dysfunction. Int J Impot Res. 1996;8:47–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Konstantinos G, Petros P. Phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors: future perspectives. Curr Pharm Des. 2009;15:3540–51. doi: 10.2174/138161209789206953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kukreja R, Salloum FN, Das A, Koka S, Ockaili RA, Xi L. Emerging new uses of phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors in cardiovascular disease. Exp Clin Cardiol. 2011;16:e30–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wallis RM, Corbin JD, Francis SH, Ellis P. Tissue distribution of phosphodiesterase families and the effects of sildenafil on tissue cyclic nucleotides, platelet function, and the contractile responses of tuberculae carneae and aortic rings in vivo. Am J Cardiol. 1999;83:3C–12C. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(99)00042-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lin CS, Lin G, Xin ZC, Lue TF. Expression, distribution and regulation of phosphodiesterase 5. Curr Pharm Des. 2006;12:3493–557. doi: 10.2174/138161206778343064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rybalkin SD, Yan C, Bornfeldt KE, Beavo JA. Cyclic GMP phosphodiesterase and regulation of smooth muscle function. Circ Res. 2003;93:280–91. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000087541.15600.2B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sebkhi A, Strange JW, Phillips SC, Wharton J, Wilkins MR. Phosphodiesterase type 5 as a target for the treatment of hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension. Circulation. 2003;107:3230–3235. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000074226.20466.B1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wharton J, Strange JW, Moller GM, Growcott EJ, Ren X, Franklyn AP, Phillips SC, Wilkins MR. Antiproliferative effect of phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibition in human pulmonary artery cells. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172:105–13. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200411-1587OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li M, Sun X, Li Z, Liu Y. Inhibition of cGMP phosphodiesterase 5 suppresses serotonin signaling in pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells. Pharmacol Res. 2009;59:312–8. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2009.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Durante W, Johnson FK, Johnson RA. Role of carbon monoxide in cardiovascular function. J Cell Mol Med. 1996;10:672–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2006.tb00427.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Durante W. Targeting heme oxygenase-1 in vascular disease. Curr Drug Targets. 2011;11:1504–16. doi: 10.2174/1389450111009011504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morris SM, Jr, Billiar TR. New insights into the regulation of inducible nitric oxide synthase. Am J Physiol. 1994;266:E829–39. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1994.266.6.E829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stone JT, Marletta MA. Soluble guanylate cyclase from bovine lung: activation with nitric oxide and carbon monoxide and spectral characterization of the ferrous and ferric states. Biochemistry. 1994;33:5636–40. doi: 10.1021/bi00184a036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brune B, Ullrich V. Inhibition of platelet aggregation by carbon monoxide is mediated by the activation of guanylate cyclase. Mol Pharmacol. 1987;32:497–504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson RA, Lavesa M, Askari B, Abraham NG, Nasjletti A. A heme oxygenase product, presumably carbon monoxide, mediates a vasodepressor function in rats. Hypertension. 1995;25:166–9. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.25.2.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peyton KJ, Reyna SV, Chapman GB, Ensenat D, Liu XM, Wang H, Schafer AI, Durante W. Heme oxygenase-1-derived carbon monoxide is an autocrine inhibitor of vascular smooth muscle cell growth. Blood. 2002;99:4443–8. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.12.4443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Otterbein LE, Zuckerbraun BS, Haga M, Liu F, Song R, Usheva A, Stachulak C, Bodyak N, Smith RN, Csizmadia E, Tyagi S, Akamatsu Y, Flavell RJ, Billiar TR, Tzeng E, Bach FH, Choi AM, Soares MP. Carbon monoxide suppresses arteriosclerosis lesions associated with chronic graft rejection and balloon injury. Nat Med. 2003;9:183–90. doi: 10.1038/nm817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Durante W, Schini VB, Catovsky S, Kroll MH, Vanhoutte PM, Schafer AI. Plasmin potentiates the induction of nitric oxide synthesis by interleukin-1β in vascular smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1993;264:H617–23. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1993.264.2.H617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wei Y, Liu XM, Peyton KJ, Wang H, Johnson FK, Johnson RA, Durante W. Hypochlorous acid-induced heme oxygenase-1 gene expression promotes human endothelial cell survival. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2009;297:C907–15. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00536.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu XM, Peyton KJ, Shebib AR, Wang H, Durante W. Compound C stimulates heme oxygenase-1 expression via the Nrf2-ARE pathway to preserve human endothelial cell survival. Biochem Pharmacol. 2011;82:371–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2011.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alam J, Wicks C, Stewart D, Gong P, Touchard C, Otterbein S, Choi AM, Burrow ME, Tou J. Mechanism of heme oxygenase-1 gene activation by cadmium in MCF-7 mammary epithelial cells. Role of p38 kinase and Nrf2 transcription factor. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:27694–702. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004729200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Durante W, Liao L, Iftikhar I, O’Brien WE, Schafer AI. Differential regulation of L-arginine transport and nitric oxide production by vascular smooth muscle and endothelium. Circ Res. 1996;78:1075–82. doi: 10.1161/01.res.78.6.1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Itoh K, Wakabayashi N, Katoh Y, Ishii T, O’Connor Y, Yamamoto M. Keap1 regulates both cytoplasmic-nuclear shuffling and degradation of Nrf2 in response to electrophiles. Genes Cells. 2003;8:379–91. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.2003.00640.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang DD, Hannink M. Distinct cysteine residues in keap1 are required for keap1-dependent ubiquitination of Nrf2 and for stabilization of Nrf2 by chemopreventative agents and oxidative stress. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:8137–51. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.22.8137-8151.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vidavalur R, Penumathsa SV, Zhan L, Thirunavukkarasu M, Maulik N. Sildenafil induces angiogenic response in human coronary arteriolar endothelial cells through the expression of thioredoxin, hemeoxygenase, and vascular endothelial growth factor. Vasc Pharmacol. 2006;45:91–5. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2006.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aziz MT, Al-Asmar MF, Mostafa T, Atta H, Rashed L, Sabry D, Ashour S, Aziz AT. Assessment of heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) activity in the cavernous tissues of sildenafil citrate-treated rats. Asian J Androl. 2007;9:377–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7262.2007.00241.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aziz MT, Mostafa T, Atta H, Rashed L, Marzouk SA, Obaia EM, Sabry D, Hassouna AA, El-Shehaby AM, Aziz AT. The role of PDE5 inhibitors in heme oxygenase-cGMP relationship in cavernous tissues. J Sex Med. 2008;5:1636–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00729.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alam J, Cook JL. How many transcription factors does it take to turn on the heme oxygenase-1 gene. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2007;36:166–74. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2006-0340TR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu XM, Peyton KJ, Ensenat D, Wang H, Hannink M, Alam J, Durante W. Nitric oxide stimulates heme oxygenase-1 gene transcription via the Nrf2-ARE complex to promote vascular smooth muscle cell survival. Cardiovasc Res. 2007;75:381–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2007.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dias-Junior CA, Souza-Costa DC, Zerbini T, da Roche JB, Gerlach RF, Tanus-Santos JE. The effect of sildenafil on pulmonary embolism-induced oxidative stress and pulmonary hypertension. Anesth Analg. 2005;101:115–20. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000153499.10558.F3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bevalacqua TJ, Sussan TE, Gebska MA, Strong TD, Berkowitz DE, Biswal S, Burnett AL. Sildenafil inhibits superoxide formation and prevents endothelial dysfunction in a mouse model of secondhand smoke induced by erectile dysfunction. J Urol. 2009;181:899–906. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.10.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Speranza L, Franceschelli S, Pesce M, Vinciguerra I, De Lutiis MA, Grilli A, Felaco M, Patruno A. Phosphodiesterase type-5 inhibitor and oxidative stress. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2008;21:879–89. doi: 10.1177/039463200802100412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Das A, Durrant D, Mitchell C, Mayton E, Hoke NH, Salloum FN, Park MA, Qureshi I, Lee R, Dent P, Kukreja RC. Sildenafil increases chemotherapeutic efficacy of doxorubicin in prostate cancer cells and ameliorates cardiac dysfunction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:18202–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1006965107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kukreja RC. Mechanism of reactive oxygen species generation after opening of mitochondrial KATP channels. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;291:H2041–3. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00772.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cornwall TL, Arnold E, Boerth NJ, Lincoln TM. Inhibition of smooth muscle cell growth by nitric oxide and activation of cAMP-dependent protein kinase by cGMP. Am. J. Physiol. 1994;267:C1405–C1413. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1994.267.5.C1405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Iimura O, Kusano E, Homma S, Takeda S, Ikeda U, Shimada K, Asano Y. Atrial natriuretic peptide enhances IL-1β-stimulated nitric oxide production in cultured rat vascular smooth muscle cells. Kidney Blood Press Res. 1998;21:36–41. doi: 10.1159/000025841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu XM, Peyton KJ, Mendelev NN, Wang H, Tulis DA. YC-1 stimulates the expression of gaseous monoxide-generating enzymes in vascular smooth muscle cells. Mol Pharmacol. 2009;75:208–17. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.048314. (2009) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Boese M, Busse R, Mulsch A, Schini-Kerth V. Effect of cyclic GMP-dependent vasodilators on the expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase in vascular smooth muscle cells: role of cyclic AMP. Br J Pharmacol. 1996;119:707–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15730.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Salloum F, Yin C, Xi L, Kukreja RC. Sildenafil induces delayed preconditioning through inducible nitric oxide synthase-dependent pathway in mouse heart. Circ Res. 2003;92:595–7. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000066853.09821.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Das A, Xi L, Kukreja RC. Phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitor sildenafil preconditions adult cardiac myocytes against necrosis and apoptosis. Essential role of nitric oxide signaling. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:12944–55. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404706200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim KO, Park SY, Han CW, Chung HK, Yoo DH, Han JS. Effect of sildenafil citrate on interleukin-1beta-induced nitric oxide synthesis and iNOS expression in SW982 cells. Exp Mol Biol. 2008;40:286–93. doi: 10.3858/emm.2008.40.3.286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhao S, Zhang L, Lian G, Wang X, Zhang H, Yao X, Yang J, Wu C. Sildenafil attenuates LPS-induced pro-inflammatory responses through down-regulation of intracellular ROS-related MAPK/NF-κB signaling pathways in N9 microglia. Int Immunopharmacol. 2011;11:468–474. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2010.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Milligan PA, Marshall SF, Karlsson MO. A population pharmacokinetic analysis of sildenafil citrate in patients with erectile dysfunction. Br J Clin Pharm. 2002;53:455–525. doi: 10.1046/j.0306-5251.2001.00032.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Muirhead GJ, Wilner K, Colburn W, Haug-Pihale G, Rouviex B. The effects of age and renal and hepatic impairment on the pharmacokinetics of sildenafil citrate. Br J Clin Pharm. 2002;53:21S–30S. doi: 10.1046/j.0306-5251.2001.00029.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ali F, Zakkar M, Karu K, Lidington EA, Hamdulay SS, Boyle JJ, Zloh M, Bauer A, Haskard DO, Evans PC, Mason JC. Induction of the cytoprotective enzyme heme oxygenase-1 by statins is enhanced in vascular endothelium exposed to laminar shear stress and impaired by disturbed flow. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:1882–92. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.009886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhao L, Mason NA, Morrell NW, Kojonazarov B, Sadykov A, Maripov A, Mirrakhimov MM, Aldashev A, Wilkins MR. Sildenafil inhibits hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension. Circulation. 2001;104:424–28. doi: 10.1161/hc2901.093117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cashen DE, MacIntyre DE, Martin WJ. Effects of sildenafil on erectile activity in mice lacking neuronal or endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Br J Pharmacol. 2002;136:693–700. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Abdel Aziz MT, El-Asmer MF, Mostafa S, Atta H, Aziz Wassef MA, Fouad H, Rashed L, Sabry D, Mahfouz S. Heme oxygenase vs nitric oxide synthase in signaling mediating sildenafil citrate action. J Sex Med. 2007;4:1098–1107. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00533.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ockaili T, Salloum F, Hawkins J, Kukreja RC. Sildenafil (Viagra) induces powerful cardioprotective effect via opening of mitochondrial KATP channels in rabbits. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;283:H1263–69. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00324.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bolli R. Preconditioning: a paradigm shift in the biology of myocardial ischemia. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;292:H19–27. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00712.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Salloum FN, Abbate A, Das A, Houser JE, Mudrick JE, Qureshi IZ, Hoke NN, Roy Sk, Brown WR, Prabhakar S, Kukreja RC. Sildenafil (Viagra) attenuates ischemic cardiomyopathy and improves left ventricular function in mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;294:H1398–1406. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.91438.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liu X, Simpson JA, Brunt KR, Ward CA, Hall SR, Kinobe RT, Barrette V, Tse MY, Pang SC, Pachori AS, Dzau VJ, Ogunyankin KO, Melo LG. Preemptive heme oxygenase-1 gene delivery reveals reduced mortality and preservation of left ventricular function 1 yr after acute myocardial infarction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;293:H48–59. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00741.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]