Abstract

Although situational avoidance is viewed as the most disabling aspect of panic disorder (PD), few studies have evaluated how dimensions of neurotic (i.e., NT; neuroticism, behavioral inhibition) and extraverted (i.e. ET; extraversion, behavioral activation) temperament may influence the presence and severity of agoraphobia (AG). Using logistic regression and structural equation modeling, the present study examined the unique effects of ET on situational avoidance in a sample of 274 outpatients diagnosed with PD with and without AG. Results showed low ET (i.e., introversion) to be associated with both the presence and severity of situational avoidance. Findings are discussed in regard to conceptualizations of conditioned avoidance, activity levels, sociability, and positive emotions within the context of PD with AG.

Panic disorder (PD) involves various maladaptive cognitive and behavioral responses. Among the most impairing behavioral responses to panic are interoceptive, experiential, and situational avoidance tactics. Interoceptive avoidance involves refusing substances (e.g., caffeine) or activities (e.g., exercise) that elicit panic-like symptoms. Experiential avoidance refers to attempts to control panic via medications or distraction. Situational avoidance, which has been described as “the most palpable and impairing aspect of PD” (p. 148, White, Brown, Somers, & Barlow, 2006), involves a refusal to enter or tendency to escape from feared environments (e.g., bridges, crowds, elevators).

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed., Text Revision; DSM-IV-TR; American Psychiatric Association, 2000) describes agoraphobia (AG) as anxiety linked to situations from which escape might be difficult or help may be unavailable in the event of panic symptoms. As fear of being in certain situations is often accompanied by a refusal to enter situations, situational avoidance is an important AG criterion. Because AG is most frequently diagnosed as comorbid with PD in clinical settings (i.e., PD with AG; Brown, Campbell, Lehman, Grisham, & Mancill, 2001), it is no surprise that conceptual models of AG have been strongly influenced by PD theories (e.g., Barlow, 2002).

Temperament, Anxiety Sensitivity, and Agoraphobia

Research and theory has implicated genetically based dimensions of neurotic (NT) and extraverted (ET) temperaments as being instrumental in the etiology and maintenance of anxiety and mood disorders (e.g., Barlow, 2002; Clark, Watson, & Mineka, 1994). Theories of emotion and personality vulnerabilities have described NT and ET by constructs such as neuroticism and extraversion (Digman, 1990; Eysenck & Eysenck, 1985), negative and positive affect (Tellegen, 1985), and behavioral inhibition and activation (Gray, 1987). Although their interrelationships are not yet fully understood, evidence suggests that neuroticism is closely related to negative affect and behavioral inhibition while extraversion shares many characteristics with positive affect and behavioral activation (Barlow, 2002; Brown, 2007; Campbell-Sills, Liverant, & Brown, 2004). Whereas NT influences the experience of negative emotional states (i.e., anxiety, sadness), ET is related to sociability, levels of activity, reward-seeking behaviors, and positive emotions (i.e., excitement, joy).

Contemporary conceptualizations of the relationships between temperament and the emotional disorders stem from the tripartite model, which posited that NT (i.e., negative affect, neuroticism) is relevant to both the anxiety and mood disorders, while ET (i.e., positive affect, extraversion) is uniquely related to depression (Clark & Watson, 1991). While research has consistently found strong positive correlations between NT and the full range of emotional disorders (Bienvenu et al., 2001, 2004; Brown, 2007; Brown, Chorpita, & Barlow, 1998), findings regarding ET have been limited and mixed. For example, although initial support for the unique association between ET and depression was found in some non-clinical samples (Joiner, 1996) and samples with low rates of anxiety (Watson et al., 1995), examinations of outpatient and epidemiological data also found significant inverse relationships between ET (i.e., high introversion) and social phobia (e.g., Bienvenu et al., 2001; Brown et al., 1998). As subsequent research further supported this relationship (for a meta-analytic review, see Kashdan, 2007), leading conceptual models of the emotional disorders have been revised to reflect such findings (e.g., Mineka, Watson, & Clark, 1998).

Although the evidence is sparse, significant associations have been found between dimensions of ET and AG. For example, Bienvenu et al. (2001) used logistic regression to examine if ET (i.e., extraversion) predicted lifetime prevalence of various DSM anxiety and mood disorders. Results showed that ET was a significant predictor of AG, whereby lower levels ET (i.e., high introversion) were associated with increased odds of a lifetime AG diagnosis. Significant associations between ET and PD were not found. Although studies have had success in replicating and extending these findings (e.g., Bienvenu et al., 2004), few have accounted for the occurrence of AG secondary to PD (e.g., PD with AG). A notable exception is Carrera et al.’s (2006) study of personality traits among patients in the early phases of PD, which controlled for comorbidity between PD and AG. Results showed that ET (i.e., introversion) predicted a diagnosis of PD with AG but not PD without AG. The authors interpreted this finding to indicate that low levels of ET may contribute to the development of AG within PD but not PD itself.

Although compelling, these studies provide limited information about the relationship between ET and AG by exclusively examining DSM diagnostic status. The degree of impairment assumed to be caused by situational avoidance (e.g., White et al., 2006) suggests it may be more important to study avoidance behaviors within AG rather than broadly studying the presence of the disorder. Moreover, exclusively examining dichotomous representations of dimensional phenomena (i.e., diagnoses) provides limited utility by not capturing important information (cf. Brown & Barlow, 2005; MacCallum, Zhang, Preacher, & Rucker, 2002) such as individual differences in AG severity.

Preliminary evidence regarding the relationship between ET and AG has been useful in examining genetic relationships between ET and AG. Recently, Bienvenu, Hettema, Neale, Prescott, and Kendler (2007) used a large twin sample to test the independent genetic contributions of ET and NT (i.e., extraversion and neuroticism) on heritable influences (i.e., genetic vs. shared environmental factors) of AG. Analyses found significant negative within-person correlations between extraversion and AG and that monozygotic twins had higher cross-twin correlations than dizygotic twins. In other words, the genetic factors that influence extraversion are the same as those affecting a lifetime diagnosis of AG.

In addition to ET and NT, conceptualizations of PD and AG also emphasize the construct of anxiety sensitivity (AS), or the fear of anxiety and anxiety-related physical symptoms. Much like ET and NT, AS may be a heritable vulnerability playing an important role in PD and AG (Stein, Jang, & Livesley, 1999). It is posited that high AS may develop early in life and, coexisting with high levels of NT, may lead to the onset and maintenance of the PD or PD with AG (Barlow, 2002). This model has received support, as individuals with heightened levels of AS experience a greater degree of panic symptoms (Zinbarg, Brown, Barlow, & Rapee, 2001) and agoraphobic fear and avoidance (Taylor & Rachman, 1992; White et al., 2006). Unfortunately, these studies have not evaluated the unique contributions of AS while controlling for NT.

Although the negative consequences of AG within PD have been well documented, relatively few studies have focused on the relationship between ET and situational apprehension and avoidance. Extant studies have rarely examined ET and AG in clinical samples or contained AG symptom information beyond diagnostic status (e.g., Bienvenu et al., 2001, 2004; Carrera et al., 2006). Moreover, much of the literature examining PD and AG has not controlled for levels of NT and AS (e.g., Taylor & Rachman, 1992; White et al., 2006). The present study aims to examine the unique effects of ET on agoraphobic avoidance in PD within a clinical sample. ET was hypothesized to predict the presence and severity of agoraphobic avoidance while controlling for NT and AS. It was also hypothesized that ET would predict the severity of AG but not be associated with the severity of PD.

Method

Participants

The sample was 274 patients presenting for assessment and treatment at the Center for Anxiety and Related Disorders (CARD) at Boston University. The sample was predominantly female (60.2%) and the average age was 32.88 (SD = 10.56, range = 18 to 77). The majority of participants identified as Caucasian (85.8%). Individuals were assessed by doctoral students or doctoral-level clinical psychologists using the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV-Lifetime Version (ADIS-IV-L; Di Nardo, Brown, & Barlow 1994). The ADIS-IV-L is a semi-structured interview that assesses DSM-IV (APA, 2000) anxiety, mood, somatoform, and substance use disorders. When administering the ADIS-IV-L, clinicians assign each diagnosis a 0-8 clinical severity rating (CSR) that represents the degree of distress or impairment in functioning associated with specific diagnoses. The disorder receiving the highest CSR is considered an individual’s “principal” diagnosis. Patients were included in the study if they met criteria for a principal diagnosis of PD with AG (n = 260) or PD without AG (n = 14). The ADIS-IV-L has shown good-to-excellent reliability for the majority of anxiety and mood disorders, including PD with AG (κ = .77) and PD without AG (κ = .72) (Brown, Di Nardo, Lehman, & Campbell, 2001). Study exclusionary criteria were current suicidal/homicidal intent and/or plan, psychotic symptoms, or significant cognitive impairment (e.g., dementia, mental retardation).

Regression and Structural Model Indicators

ADIS-IV-L panic disorder criteria ratings

Clinicians made severity ratings for the following DSM-IV PD criteria on a 0 (absent) to 8 (very severely disturbing/disabling) scale: (1) recurrent and unexpected panic attacks, (2) fear of having additional attacks, (3) worry about the consequences of panic, and (4) change in behavior related to the panic. A composite score composed of ratings (1) through (3) was generated for each participant. Rating (4) was omitted from the composite score because of redundancy with indicators of AG (i.e., situational avoidance would be considered a significant change in behavior).

ADIS-IV-L situational avoidance ratings

The AG section of the ADIS-IV-L contains a subsection in which clinicians assess and rate the patient’s avoidance of 22 situations associated with PD (e.g., public transportation, theaters) from 0 (no avoidance) to 8 (very severe avoidance). The AG rating score has been associated with excellent inter-rater reliability (Brown, Di Nardo, et al., 2001). The AG scale structure was evaluated using exploratory factor analysis (EFA). Although the EFA confirmed unidimensionality, one item had a factor loading < .30 (item 14, ‘Being home alone’) and was removed from the composite rating.

Albany Panic and Phobia Questionnaire (APPQ; Rapee, Craske, & Barlow, 1994)

The APPQ is a 27-item questionnaire measuring interoceptive, situational, and social related fears. Respondents rate how much fear they would experience in certain activities and situations on a 0 (no fear) to 8 (extreme fear) scale. The 9-item Agoraphobia scale (APPQ-A), measuring situational apprehension commonly associated with panic (e.g., driving, theaters), and 5-item Interoceptive scale (APPQ-I), assessing fear associated with activities/objects that may mimic panic symptoms, were used in this study. Evaluation of the APPQ supports the factor structure, reliability, and validity of the APPQ in clinical samples (Brown, White, & Barlow, 2005).

Anxiety Sensitivity Index (ASI; Peterson & Reiss, 1992)

The ASI is a 16-item measure in which patients rate each item on a 0 (very little) to 4 (very much) scale. The ASI has adequate reliability and validity and is composed of a hierarchical factor structure, with three lower-order factors (i.e., Physical Concerns, Mental Incapacitation, and Social Concerns), and a single, higher-order factor (Zinbarg, Barlow, & Brown, 1997).

Behavioral Inhibition/Activation Scales (BIS/BAS; Carver & White, 1994)

The BIS/BAS is a 20-item self-report instrument designed to assess Gray’s (1987) personality constructs of behavioral inhibition and activation. Items are rated on a 4-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 “quite untrue of you” to 4 “quite true of you.” The BIS/BAS has demonstrated excellent psychometric properties in clinical samples (Campbell-Sills et al., 2004).

NEO Five Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI; Costa & McCrae, 1992)

The NFFI is a 60-item self-report inventory assesses dimensions of the five-factor model of personality: neuroticism, extraversion, openness, agreeableness, and conscientiousness. Items are rated on 5-point Likert scale, which ranges from 0 (“strongly disagree”) to 4 (“strongly agree”). The NEO-FFI is the abbreviated form the NEO-PI-R, a widely used self-report personality measure that has demonstrated excellent reliability and validity (Costa & McCrae, 1992).

Analytic plan

Logistic regression and structural models were evaluated in Mplus 5.2 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998-2009). Missing data were handled by direct maximum likelihood estimation. Model fit was examined using the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) and its test of close fit (C-Fit), the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), the comparative fit index (CFI), and the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR). Guidelines defined by Hu and Bentler (1999) were used in determining acceptable fit (i.e., RMSEA near or below .06, C-Fit above .05, TLI and CFI near or above .95, SRMR near or below .08). Multiple goodness-of-fit parameters were evaluated in order to examine various aspects of model fit (i.e., absolute fit, parsimonious fit, fit relative to the null). Unstandardized and completely standardized solutions were examined to evaluate the significance and strength of parameter estimates. Standardized residuals and modification indices were used to determine the presence of any localized areas of strain in the solution.

Results

Logistic Regression Models

Logistic regression analyses were conducted to examine if ET uniquely predicted the presence of situational avoidance within PD patients while controlling for NT and AS. Situational avoidance was defined as having a secondary AG diagnosis and an ADIS-IV-L situational avoidance rating above 0 (n = 222) or not (n = 29; 23 cases excluded because of missing questionnaires). Two regression models were examined such that the presence of situational avoidance was regressed onto constructs representing dimensions of temperament (i.e., NEO-FFI and BIS/BAS) and AS. As shown in Table 1, only the Extraversion scale was found to significantly predict the presence of situational avoidance (B = −0.07, p < .05) in the NEO-FFI and AS model. Lower levels of ET (i.e., higher introversion) were associated with increased odds of agoraphobic avoidance (odds ratio = .94, 95% confidence interval = .87 to .99). The regression coefficient for the BAS scale approached statistical significance (B = −0.06, p = .10) in the BIS/BAS and AS model.

Table 1.

Logistic Regression Models Evaluating the Relationship Between Temperament Constructs and the Presence of Situational Agoraphobic Avoidance

| Model and predictor variables | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Presence of situational agoraphobic avoidance |

|||

| B | t | OR (95% CI) | |

|

|

|||

| NEO-FFI: | |||

| ASI-P | 0.020 | 0.694 | 1.02 (0.96 - 1.08) |

| Neuroticism | −0.039 | 1.527 | 0.96 (0.91 - 1.01) |

| Extraversion | −0.065 | 2.296* | 0.94 (0.89 - 0.99) |

| Constant: | −4.497 | 3.643*** | |

|

|

|||

| BIS/BAS: | |||

| ASI-P | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.99 (0.94 - 1.06) |

| Behavioral inhibition | 0.04 | 0.72 | 1.04 (0.93 - 1.17) |

| Behavioral activation | −0.06 | 1.67 | 0.95 (0.89 - 1.01) |

| Constant: | −3.31 | 1.74 | |

Note. OR = Odds Ratio; 95% CI = 95% Confidence Interval; NEO-FFI = NEO Five Factor Inventory; BIS/BAS = Behavioral Inhibition and Activation Scales; ASI-P = Anxiety Sensitivity Index – Physical Concerns scale.

p < .05,

p < .001

Structural Equation Models

Structural regression models were fit to the data to examine the unique association between dimensions of ET and AG. The BAS and NEO-Extraversion subscales were used as indicators for a latent variable representing ET, while BIS and NEO-Neuroticism were specified to load on the NT factor. AS was defined solely by ASI-Physical Concerns because of its theoretical relevance specific to PD and AG (Zinbarg et al., 2001). A latent variable representing dimensions of AG was comprised of the APPQ-A subscale and ADIS-IV-L AG situational avoidance rating. The APPQ-I subscale and ADIS-IV-L PD criteria composite rating (see Method section) were used as indicators to represent the latent variable of PD.

Two structural models were evaluated, whereby latent representations of AG (Model 1) and PD (Model 2) were regressed onto dimensions of NT, ET, and AS. Measurement models of the temperament and disorder constructs were not separately evaluated because both models were structurally just-identified. Initial inspections of the models revealed that model fit could be improved if a correlated error was estimated between the NEO-Extraversion and NEO-Neuroticism scales (Model 1 and 2 modification indices = 14.16 and 13.79, respectively). The models were subsequently specified to reflect this method variance shared between the NEO subscales.

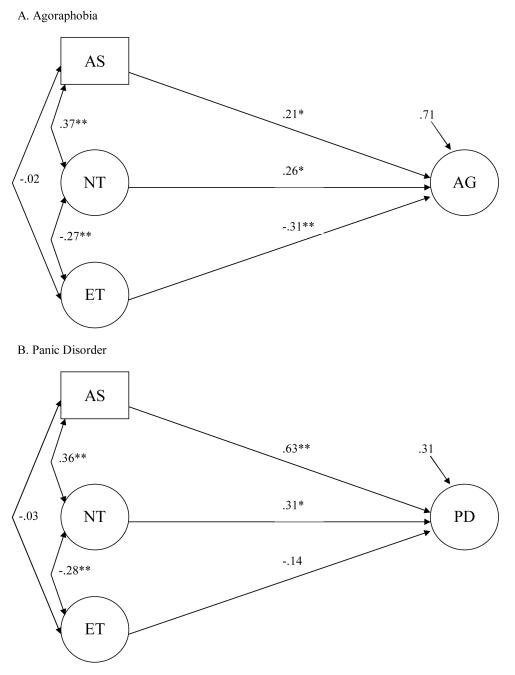

It was predicted that when holding NT and AS constant, ET would demonstrate an inverse and statistically significant structural path to AG but not PD. Model 1 fit the data well, χ2(8) = 18.286, p < .05, SRMR = 0.03, RMSEA = 0.06 (CFit p = .20), TLI = 0.94, CFI = .97. Figure 1a shows the completely standardized estimates from this solution. In total, AS, NT, and ET explained 29% of the variance in AG. ET uniquely explained a significant portion of the variance in AG (γ = −.31, p < .001) while controlling for AS and NT. The regression paths for AS and NT were also significant; both predictors demonstrated a positive relationship with AG (γ = .21 and .26, respectively; ps < .01).

Figure 1.

Latent structural models of the relationship between dimensions of agoraphobia, panic disorder, temperament, and anxiety sensitivity. AG = agoraphobia, PD = panic disorder ET = extraverted temperament, NT = neurotic temperament, AS = anxiety sensitivity. Completely standardized estimates are shown. *p < .01, **p < .001.

Figure 1b shows the completely standardized estimations from Model 2, which also fit the data well, χ2(8) = 13.681, p = 0.09, SRMR = 0.03, RMSEA = 0.05 (CFit p = .43), TLI = 0.96, CFI = .98. AS, NT, and ET accounted for 69% of the variance in PD. Consistent with prediction, there was not a significant path between ET and PD (γ = −.14, ns). However, AS and NT each uniquely predicted a significant portion of the variance in PD (γ = .63 and .31, p < .001 and < .01, respectively).

Discussion

Consistent with hypotheses and prior research (i.e., Bienvenu et al., 2001; Carrera et al., 2006), results from the logistic regression analyses showed ET constructs to uniquely predict (NEO-Extraversion) or have trends towards predicting (BAS) the presence of situational avoidance among PD patients while controlling for NT and AS. Structural modeling confirmed that ET was inversely and significantly related to dimensions of AG but not PD. The present study adds to literature on ET and AG conducted at the diagnostic level (i.e., Bienvenu et al., 2001; Carrera et al., 2006) by specifically examining the presence and severity of situational agoraphobic avoidance, arguably the most disabling aspect of PD with AG (White et al., 2006).

In general, introversion was associated with both the presence and severity of situational avoidance among individuals with PD. These results add to the findings of Carrera et al. (2006) by showing that ET may have a more circumscribed relationship with situational avoidance rather than being broadly related to a diagnosis of AG. In line with a predispositional relationship between ET and AG (cf. Brown, 2007; Clark et al., 1994), theory on temperament and aversive conditioning has posited that introverted individuals perceive unconditioned stimuli as subjectively stronger and consequently more reinforcing (Eysenck & Eysenck, 1985). In other words, introverted individuals who experience recurrent and unexpected panic attacks may be more prone to associate their panic symptoms with concurrent stimuli (i.e., the environment), leading them to develop AG characterized by greater situational avoidance. Activation levels, reward-seeking behaviors, and sociability may also play a role; AG may reflect a premorbid disposition toward low activity/reward-seeking (i.e., low ET) expressed in the context of unexpected panic, or discomfort/disinterest (i.e., low ET) being around others when experiencing a vulnerable emotional state like panic. Indeed, the relevance of ET in approach/avoidance motivation and reward-seeking behaviors has been theorized (i.e., introverts are less likely to find novel environments exciting/enjoyable; Eysenck & Eysenck, 1985) and supported in laboratory studies (cf. Robinson, Meier, & Vargas, 2005). Positive emotionality may also have an influence on AG, as individuals prone to experience low levels of positive emotions (i.e., low levels of ET) may have difficulty distinguishing the source of the similar physiological symptoms of panic and positive emotions (i.e., increased heart rate due to panic versus excitement). Through interoceptive fear conditioning principles (i.e., McNally, 1990), the physiological symptoms of positive emotions may serve as a panic trigger. Along these lines, Williams, Chambless, and Ahrens (1997) found that fears of positive emotions (and anger) predicted fear of laboratory-induced bodily sensations in a non-clinical sample.

Conversely, the present findings may also reflect other types of relationships between ET and AG. For instance, according to a complication/scar model (cf. Brown, 2007; Clark et al., 1994), the presence of AG may cause reductions in ET. In other words, developing increasingly severe situational avoidance may lead individuals to be less active and sociable, seek fewer rewards, and experience fewer positive emotions. It is also possible that low ET and AG reflect similar underlying processes, regardless of one’s experience of panic. Perhaps introversion is avoidant behavior, with AG serving as expression of this temperament in the context of unexpected panic. Unfortunately, the cross-sectional and correlational nature of the present study precluded our ability to disentangle predispositional, complication/scar, or tautological interpretations.

Although not an a priori aim of the study, findings supporting the effects of AS and NT on PD and AG are consistent with theory (i.e., Barlow, 2002) and add to the extant literature on these vulnerabilities, which has rarely examined these constructs while controlling for the other (e.g., White et al., 2006). Given the past debate over the discriminant and incremental validity of AS over NT (Lilienfeld, Jacob, & Turner 1989), it is interesting that both NT and AS significantly predicted dimensions of AG and PD in the structural models. Thus, despite any phenotypic overlap in NT and AS among patients with AG and PD (e.g., experiencing negative affect in response to negative affect, or anxiety focused on fear), both constructs explain a unique portion of the variance in AG and PD.

Despite strengths in methodology (i.e., analyses conducted in a latent variable framework, use of self-report and clinician rated indicators) and sampling (i.e., large clinical sample), the present study has some limitations. For example, the APPQ-I provides limited information about a single dimension of PD. Although the APPQ-I assesses common behavioral changes related to PD (i.e., avoidance of caffeine), a questionnaire assessing broader dimensions of panic, such as panic frequency and fear (e.g., the Panic Disorder Severity Scale-Self Report; Houck, Spiegel, Shear, & Rucci, 2002) may have been more appropriate. Another limitation is the predominate representation of Caucasians in the study. Additional research on more diverse samples is needed to examine if the relationship between ET and AG generalizes to other cultural groups. Finally, the sample may have benefited from a greater representation of PD without AG patients. Further study of PD without AG may aid in distinguishing features uniquely associated with the development of AG within the context of PD.

Many individuals with PD experience profound disability through persistent avoidance of the situations they associate with panic. Although results of the present study provide meaningful information to the body of literature examining ET and AG, additional research is needed to further examine etiological and maintenance factors of AG. For example, longitudinal research following individuals from premorbid periods to early phases of PD is needed to clarify the relationship between ET and AG (e.g., does low ET cause AG or vice versa). In addition, experimental research examining the experience of positive emotions in anxiety disorders may aid in our understanding of ET’s relevance to disorders such as social phobia and AG.

References

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Author; Washington, DC: 2000. Text Revision. [Google Scholar]

- Barlow DH. Anxiety and its disorders: The nature and treatment of anxiety and panic. 2nd ed Guilford Press; New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Bienvenu OJ, Brown C, Samuels JF, Liang K, Costa PT, Eaton WW, et al. Normal personality traits and comorbidity among phobic, panic, and major depressive disorders. Psychiatry Research. 2001;102:73–85. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(01)00228-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bienvenu OJ, Hettema JM, Neale MC, Prescott CA, Kendler KS. Low extraversion and high neuroticism as indices of genetic and environmental risk for social phobia, agoraphobia, and animal phobia. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;164:1714–1721. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06101667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bienvenu OJ, Samuels JF, Costa PT, Reti IM, Eaton WW, Nestadt G. Anxiety and depressive disorders and the five-factor model of personality: A higher- and lower-order personality trait investigation in a community sample. Depression and Anxiety. 2004;20:92–97. doi: 10.1002/da.20026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA. Temporal course and structural relationships among dimensions of temperament and DSM–IV anxiety and mood disorder constructs. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2007;116:313–328. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.116.2.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA, Barlow DH. Categorical vs. dimensional classification of mental disorders in DSM–V and beyond. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2005;114:551–556. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.4.551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA, Campbell LA, Lehman CL, Grisham JR, Mancill RB. Current and lifetime comorbidity of the DSM-IV anxiety and mood disorders in a large clinical sample. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2001;110:585–599. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.110.4.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA, Chorpita BF, Barlow DH. Structural relationships among dimensions of the DSM-IV anxiety and mood disorders and dimensions of negative affect, positive affect, and autonomic arousal. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1998;107:179–192. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.107.2.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA, Di Nardo PA, Lehman CL, Campbell LA. Reliability of DSM-IV anxiety and mood disorders: Implications for the classification of emotional disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2001;110:49–58. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.110.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA, White KS, Barlow DH. A psychometric re-evaluation of the Albany Panic and Phobia Questionnaire. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2005;43:337–355. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2004.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell-Sills L, Liverant GI, Brown TA. Psychometric evaluation of the Behavioral Inhibition/Behavioral Activation Scales in a large sample of outpatients with anxiety and mood disorders. Psychological Assessment. 2004;16:244–254. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.16.3.244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrera M, Herran A, Ramirez ML, Ayestaran A, Sierra-Biddle D, Hoyuela F, et al. Personality traits in early phases of panic disorder: Implications on the presence of agoraphobia, clinical severity, and short-term outcome. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2006;114:417–425. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00826.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark LA, Watson D. Tripartite model of anxiety and depression: Psychometric evidence and taxonomic implications. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1991;100:316–336. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.100.3.316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark LA, Watson D, Mineka S. Temperament, personality, and the mood and anxiety disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1994;103:103–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa PT, McCrae RR. Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI-R) and NEO Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI) professional manual. Psychological Assessment Resources; Odessa, FL: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Digman JM. Personality structure: Emergence of the five-factor model. Annual Review of Psychology. 1990;41:417–440. [Google Scholar]

- Eysenck HJ, Eysenck MW. Personality and individual differences: A natural science approach. Plenum Press; New York: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Gray JA. The psychology of fear and stress. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, England: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Houck PR, Spiegel DA, Shear MK, Rucci P. Reliability of the self-report version of the Panic Disorder Severity Scale. Depression and Anxiety. 2002;115:183–185. doi: 10.1002/da.10049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE. A confirmatory factor-analytic investigation of the tripartite model of depression and anxiety in college students. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 1996;20:521–539. [Google Scholar]

- Kashdan TB. Social anxiety spectrum and diminished positive experiences: Theoretical synthesis and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review. 2007;27:348–365. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lilienfeld SO, Jacob RG, Turner SM. Comment on Holloway and McNally’s (1987) “Effects of anxiety sensitivity on the response to hyperventilation.”. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1989;98:100–102. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.98.1.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacCallum RC, Zhang S, Preacher KJ, Rucker DD. On the practice of dichotomization of quantitative variables. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:19–40. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNally RJ. Psychological approaches to panic disorder: A review. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;108:403–419. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.108.3.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mineka S, Watson D, Clark LA. Comorbidity of anxiety and unipolar mood disorders. Annual Review of Psychology. 1998;49:377–412. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.49.1.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus 5.2 [Computer software] Author; Los Angeles: 1998-2009. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson RA, Reiss S. Anxiety sensitivity index manual. 2nd ed IDS Publishing; Worthington, OH: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Rapee RM, Craske MG, Barlow DH. Assessment instrument for panic disorder that includes fear of sensation producing activities: The Albany Panic and Phobia Questionnaire. Anxiety. 1994/1995;1:114–122. doi: 10.1002/anxi.3070010303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson MD, Meier BP, Vargas PT. Extraversion, threat categorizations, and negative affect: A reaction time approach to avoidance motivation. Journal of Personality. 2005;73:1397–1436. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2005.00353.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein MB, Jang KL, Livesley WJ. Heritability of anxiety sensitivity: A twin study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;156:246–251. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.2.246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor S, Rachman S. Fear and avoidance of aversive affective states: Dimensions and causal relations. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 1992;6:15–26. [Google Scholar]

- Tellegen A. Structures of mood and personality and their relevance to assessing anxiety with an emphasis on self-report. In: Tuma AH, Maser JD, editors. Anxiety and the anxiety disorders. Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1985. pp. 681–706. [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1988;54:1063–1070. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams KE, Chambless DL, Ahrens A. Are emotions frightening? An extension of the fear of fear construct. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1997;35:239–248. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(96)00098-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White KS, Brown TA, Somers TJ, Barlow DH. Avoidance behavior in panic disorder: The moderating influence of perceived control. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2006;44:147–157. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zinbarg RE, Barlow DH, Brown TA. Hierarchical structure and general factor saturation of the Anxiety Sensitivity Index: Evidence and implications. Psychological Assessment. 1997;9:277–284. [Google Scholar]

- Zinbarg RE, Brown TA, Barlow DH, Rapee RM. Anxiety sensitivity, panic, and depressed mood: A re-analysis teasing apart the contributions of the two levels in the hierarchical structure of the Anxiety Sensitivity Index. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2001;110:372–377. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.110.3.372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]