Abstract

Purpose

There is persistent controversy as to whether EGFR/KRAS mutations occur in pulmonary squamous cell carcinoma (SQCC). We hypothesized that the reported variability may reflect difficulties in the pathologic distinction of true SQCC from adenosquamous carcinoma (AD-SQC) and poorly-differentiated adenocarcinoma (ADC) due to incomplete sampling or morphologic overlap. The recent development of a robust immunohistochemical approach for distinguishing squamous vs glandular differentiation provides an opportunity to reassess EGFR/KRAS and other targetable kinase mutation frequencies in a pathologically homogeneous series of SQCC.

Experimental Design

Ninety-five resected SQCC, verified by immunohistochemistry as ΔNp63+/TTF-1−, were tested for activating mutations in EGFR, KRAS, BRAF, PIK3CA, NRAS, AKT1, ERBB2/HER2, and MAP2K1/MEK1. Additionally, all tissue samples from rare patients with the diagnosis of EGFR/KRAS-mutant “SQCC” encountered during5 years of routine clinical genotyping were reassessed pathologically.

Results

The screen of 95biomarker-verified SQCC revealed no EGFR/KRAS (0%; 95%CI 0–3.8%), 4 PIK3CA (4%; 95% CI 1–10%) and 1 AKT1 (1%; 95% CI 0–5.7%) mutations. Detailed morphologic and immunohistochemical reevaluation of EGFR/KRAS-mutant SQCC” identified during clinical genotyping (n=16) resulted in reclassification of 10 (63%)cases as AD-SQC and 5 (31%) cases as poorly-differentiated ADC morphologically mimicking SQCC (i.e. ADC with “squamoid” morphology). One (6%) case had no follow-up.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that EGFR/KRAS mutations do not occur in pure pulmonary SQCC, and occasional detection of these mutations in samples diagnosed as “SQCC” is due to challenges with the diagnosis of AD-SQC and ADC, which can be largely resolved by comprehensive pathologic assessment incorporating immunohistochemical biomarkers.

Keywords: EGFR, KRAS, TTF-1, p63, squamous cell carcinoma

INTRODUCTION

Adenocarcinoma (ADC) and squamous cell carcinoma (SQCC) represent the two major types of non-small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC). Historically, the subtype of NSCLC has not been a major factor in determining patient management, and fundamental differences in the molecular pathogenesis of these tumors were not well established. It is only in recent years that it has become apparent that lung ADC and SQCC have distinct driver mutation profiles, which underlies their divergent responses to targeted therapies (1). In particular, since the early identification of EGFR and KRAS mutations in NSCLC – the predictors of sensitivity and resistance, respectively, to EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) – it was noted that these mutations have a remarkable predilection for ADC (2–5). Despite the general agreement that EGFR and KRAS mutations occur almost exclusively in ADC, there has been a persistent controversy as to whether these mutations also occur, albeit at a lower frequency, in SQCC. A number of studies have described the detection of activating EGFR mutations (range 1–15%) (6–10) and KRAS mutations (range 1–9%) (11, 12) in SQCC, although in most studies the detailed pathologic analysis of those samples was not provided. Clarifying this controversy is of interest both as a biological question pertaining to the degree of lineage restriction of EGFR/KRAS mutations, and as a practical clinical question pertaining to the optimal triage of patient samples for predictive molecular testing based on the pathologic diagnosis.

There are several well-known limitations in the traditional diagnosis of NSCLC subtypes. In particular, it is well established that poorly-differentiated ADC and SQCC can appear indistinguishable by routine light microscopy, particularly in small biopsies and cytology samples, leading to a historically high rate of unclassified NSCLC and the potential for erroneous subtype assignment (13). Largely driven by the recent molecular and clinical insights on the significance of NSCLC subtypes, there has been an explosion in research aimed at circumventing the limitations of traditional morphology through the use of immunohistochemical (IHC) biomarkers to more precisely and objectively determine cell lineage in poorly-differentiated NSCLC (14–17). We (14) and others investigators (15) have shown that IHC for TTF-1 and p63 – the developmental transcription factors and master-regulators in glandular and squamous cell lineages, respectively – can effectively identify a tumor cell type in clinical samples of NSCLC with equivocal morphology. In particular, recent studies show the value of IHC for ΔN isoform of p63 – a highly squamous-specific variant of p63 (18, 19). Several studies have already shown that incorporation of IHC leads to a dramatic decline in the rate of unclassified NSCLC, as well as an increase in the accuracy and reproducibility of ADC vs SQCC diagnoses both in the investigational setting (17, 20) and in clinical practice (21, 22). For these reasons, IHC is now widely advocated to be incorporated into routine diagnosis of NSCLC that are difficult to classify by morphology (23). However, to what degree the lack of precision in the morphologic diagnosis of NSCLC subtypes in pre-IHC era may have contributed to atypical molecular findings has not been investigated in detail.

Another well-known confounder in the accurate determination of NSCLC subtype is adenosquamous carcinoma (AD-SQC) -a rare tumor, representing0.4–4% of NSCLC (24), which shows bi-directional differentiation with morphologically and immunophenotypically distinct squamous and glandular components. Preoperative diagnosis of AD-SQC is notoriously difficult because it requires simultaneous sampling of both components, which cannot be reliably achieved in small tissue fragments (14, 21, 23). As a result, this tumor may be diagnosed as “SQCC” or “ADC” depending on which component is sampled. Importantly, AD-SQC is known to harbor a spectrum of EGFR/KRAS mutation that is similar to ADC (25–30). Several investigators have previously suggested that the detection of EGFR mutations in small samples diagnosed as “SQCC” could be a result of incomplete sampling of AD-SQC (2, 25). However, this possibility has not been formally investigated.

Based on these issues, we hypothesized that the reported variability of EGFR/KRAS mutations in samples diagnosed as SQCC could be a result of the above difficulties in the pathologic distinction of true SQCC from ADC and AD-SQC, particularly in samples diagnosed prior to the recent advances in IHC. The goal of the study was therefore to combine mutational analysis with detailed pathologic assessment incorporating IHC. The study design included two separate approaches. First, we performed a screen for EGFR/KRAS mutations in a large series of surgically resected SQCC (n=95) in which the diagnosis was verified by IHC to exclude the possibility of inadvertent testing of ADC that morphologically mimics SQCC. Second, we performed detailed histologic and IHC reassessment of cases diagnosed as “SQCC” found to harbor EGFR/KRAS mutations during 5 years of routine molecular testing at our institution (n=16). In addition, we used this highly validated, pathologically homogenous group of pure resected SQCC to investigate mutation frequencies in six other therapeutically-targetable signaling molecules- BRAF, PIK3CA, NRAS, AKT1, ERBB2/HER2, and MAP2K1/MEK1.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

This study was approved by the institutional review board of Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC), New York, NY. For the first part of the study (mutation screen of resected IHC-verified SQCC), a search of the electronic medical records from the Department of Pathology at MSKCC was performed to identify 100lung resections with a diagnosis of SQCC. A representative formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tumor block was selected and used for IHC with ΔNp63 andTTF-1, as described below. Sufficient archival material was available for 98 cases. Of those, only cases with immunoprofiles compatible with the diagnosis of SQCC (n=95) were included in the mutation screen, as described below.

For the second part of the study (reassessment of clinical samples), a separate search was performed to identify specimens with the diagnosis of SQCC which were found to harbor EGFR or KRAS mutations during routine clinical genotyping at our institution between January 2006 and February 2011 (n=16) by methods described previously (31). Although routine testing for EGFR/KRAS mutations at out institution during this time period generally excluded tumors with the diagnosis of SQCC, testing of some samples with this diagnosis was performed at the request of the individual treating oncologists. All available pathologic samples from these patients were evaluated by light microscopy, as well as IHC for ΔNp63/TTF-1and EGFR/KRAS mutations if not previously performed and if sufficient tissue was available.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry was performed on a Bench Mark series automated stainer (Ventana, Tucson, AZ) as previously described (14, 18). Briefly, primary antibodies included ΔNp63 (p40 clone, 5–17, CalBiochem/EMD Biosciences, 1:2000 dilution) and TTF-1 (SPT24 clone, NovoCastra, 1:50 dilution). Antigen retrieval was performed using CC1 (Cell Conditioning 1; citrate buffer pH 6.0, Ventana, Tucson, AZ) for 30 minutes. Interpretation of ΔNp63/TTF-1 immunoprofiles was performed as recently described (18, 19). Briefly, ΔNp63-diffuse/TTF-1-negative profile supported SQCC. Rare cases with diffuse ΔNp63 and weak/focal coexpression of TTF-1 (known to occasionally occur in SQCC with SPT24 clone of TTF-1 antibody) were further confirmed as SQCC by diffuse expression of CK5/6 and negative Napsin A (data not shown), and such TTF-1 reactivity was regarded as non-specific. Profiles that supported ADC were TTF-1-positive/ΔNp63-negative (ΔNp63 reactivity in isolated tumor cells was scored as negative). TTF-1/ΔNp63 double-negative profile was interpreted as in determinate but favoring ADC because negative ΔNp63 is highly unusual for SQCC, whereas TTF-1-negative ADC are not uncommon (14, 18, 19). Double-negative carcinomas were further evaluated by Napsin A and mucicarmine, which were non-contributory in all cases, and this data is not shown. Reactivity for ΔNp63 and TTF-1in distinct cell populations was used to support bi-phenotypic differentiation (i.e. AD-SQC).

Mutational Analysis

DNA Extraction

Hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections corresponding to the selected FFPE tumor blocks were reviewed to identify areas of tumor. Macrodissection on 10 corresponding 5-um thick unstained sections was performed to ensure greater than 50% tumor nuclei for each case. Genomic DNA was extracted using the DN easy Tissue kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA) following the manufacturer’s recommendations. Extracted DNA was quantified on the NanoDrop8000 (Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, DE).

Mutation analysis by Sequenom mass spectrometry genotyping

Tumors were genotyped by Sequenom Mass ARRAY system (Sequenom Inc., San Diego, CA). Briefly, samples were tested in duplicate using a series of multiplexed assays designed to interrogate the hot-spot mutations in 8oncogenes: EGFR, KRAS, BRAF, PIK3CA, NRAS, AKT1, ERBB2/HER2, and MAP2K1/MEK1. A total of 92non-synonymous mutations were tested in 6 multiplex reactions (see Supplemental Figure 1 for complete list of tested mutations). Genomic DNA amplification and single base pair extension steps were performed using specific primers designed with the Sequenom Assay Designer v3.1 software. The allele-specific single base extension products were then quantitatively analyzed using matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) on the Sequenom Mass Array Spectrometer. All automated system mutation calls were confirmed by manual review of the spectra (M.E.A., M.L.).

EGFR exon 19 fragment analysis

Fragment analysis of fluorescently labeled PCR products was performed in duplicate. Briefly, a 207-bp genomic DNA fragment encompassing the entire exon 19 was amplified using the following fluorescently labeled primers (FW1: 5′-GCACCATCTCACAATTGCCAGTTA-3′; REV1: 5′-Fam-AAAAGGTGGGCCTGAGGTTCA-3′). PCR products were detected by capillary electrophoresis on an ABI 3730Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA).

RESULTS

Immunohistochemical verification and mutation screen of 95 resected pure squamous cell carcinomas

Immunohistochemistry for ΔNp63 and TTF-1 was performed on 98 resected lung tumors with the diagnosis of SQCC. Ninety-five cases had immunoprofiles supporting SQCC (ΔNp63+/TTF-1−), whereas immunoprofiles of 3 tumors were inconsistent with the diagnosis of SQCC due to diffuse expression of TTF-1 and/or lack of ΔNp63 (Supplemental Table 2). Microscopically, the3 tumors with atypical immunoprofiles were poorly-differentiated non-small cell carcinomas that had a solid growth pattern, abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm, and sharp cell borders – a morphology resembling SQCC (i.e. “squamoid”), but lacking the defining features of true SQCC (i.e. no keratinization or intercellular bridges). In conjunction with biomarker immunoprofile supporting glandular rather than squamous lineage, these tumors were reclassified as solid ADC and excluded from further analysis.

Mutation screen was performed on 95 pure IHC-verified SQCC. Clincopathologic characteristics of these patients are summarized in Table 1, and molecular results are shown in Table 2. None of the tested SQCC harbored EGFR or KRAS mutations (0% observed incidence; 95% CI 0 – 3.8%). Four tumors harbored PIK3CA mutations (4.2%; 95% CI 1.2 – 10.4%) and 1 tumor harbored an AKT1 mutation (1.1%; 95% CI 0 – 5.7%). No mutations were identified in BRAF, NRAS, ERBB2/HER2 or MAP2K1/MEK1. PIK3CA mutations occurred both in the helical domain encoded by exon9 (E542K, E545K) and in the catalytic domain encoded by exon 20 (H1047R, n=2). The clinicopathologic features of individual patients with PIK3CA/AKT1 mutations are summarized in Table 3. PIK3CA/AKT1 mutations did not show a significant association with age, gender, pack-year smoking history, tumor size, stage, and grade of differentiation (Supplemental Table 3).

Table 1.

Clinicopathologic characteristics of IHC-verified resected squamous cell carcinomas (N=95).

| Characteristic | N (%) or Median (range) |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Age | 68 (37–88) |

|

| |

| Gender | |

| Male | 62 (65) |

| Female | 33 (35) |

|

| |

| Smoking | |

| Never | 2 (2) |

| Current or former | 93 (98) |

|

| |

| Smoking pack years | 58 (0–132) |

|

| |

| Tumor size | 2.5 (0.7–11.5) |

| Tumor differentiation grade | |

| Well or moderate | 44 (46) |

| Poor | 51 (54) |

|

| |

| Stage (pathologic)† | |

| IA | 48 (51) |

| IB | 9 (10) |

| IIA | 16 (17) |

| IIB | 10 (11) |

| IIIA | 10 (11) |

| IIIB/IV | 2 (2) |

|

| |

| Surgical procedure | |

| Wedge | 31 (33) |

| Segmentectomy | 2 (2) |

| Lobectomy | 49 (52) |

| Pneumonectomy | 9 (10) |

| En block resection of lung and chest wall | 1 (1) |

| Bronchial tumor resection | 3 (3) |

|

| |

| Immunohistochemistry‡ | |

| ΔNp63+/TTF-1− | 95 (100) |

American Joint Commission on Cancer Staging Manual 7th Edition.

See Supplemental Table 2 for details.

Table 2.

Spectrum of driver oncogene mutations in 95 squamous cell carcinomas.

| Gene | N (%) with mutation | 95% confidence intervals |

|---|---|---|

| EGFR | 0 | 0 – 3.8% |

| KRAS | 0 | 0 – 3.8% |

| PIK3CA | 4 (4.2%) | 1.2 – 10.4% |

| AKT1 | 1 (1.1%) | 0 – 5.7% |

| BRAF | 0 | 0 – 3.8% |

| NRAS | 0 | 0 – 3.8% |

| ERBB2/HER2 | 0 | 0 – 3.8% |

| MAP2K1/MEK1 | 0 | 0 – 3.8% |

| Any mutation | 5 (5.3%) | 1.7 – 11.9% |

Table 3.

Clinicopathologic characteristics of individual patients with PIK3CA and AKT1 mutations in squamous cell carcinoma.

| Case ID | Mutation | Age Gender | Smoking (pack years) | Tumor size (cm) | Stage (pathologic) | Grade of differentiation | DFS (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | PIK3CA E542K | 81F | 48 | 5.5 | IIA | Poor | 63+ |

| 2 | PIK3CA E545K | 51F | 3 | 4 | IIIA | Poor | 12 |

| 3 | PIK3CA H1047R | 62M | 35 | 2.6 | IA | Poor | 22+ |

| 4 | PIK3CA H1047R | 60M | 120 | 2.5 | IIB | Moderate | 19 |

| 5 | AKT1 E17K | 65F | 63 | 2 | IA | Moderate | 23+ |

DFS disease free survival, + remains disease free, F female, M male

Reassessment of 16 EGFR/KRAS-mutant “squamous cell carcinomas”

During routine genotyping of clinical samples for EGFR/KRAS mutations, 16 samples were encountered which had a pathologic diagnosis of SQCC and were found to harbor EGFR (n=10) or KRAS (n=6) mutations. EGFR mutations included exon 19 deletions (n=7) and L858R mutations (n=3), and KRAS mutations included G12C (n=2), G12V (n=2), G12D (n=1) and G12S (n=1). The detailed histologic and IHC reassessment of the index samples (mutant “SQCC”) and all other samples available for these patients is shown in Table 4 and is described next.

Table 4.

Reassessment of 16 EGFR/KRAS-mutant “squamous cell carcinomas” identified by routine clinical genotyping.

| Pt ID | Age Gender | PY | Pathology | Mutation | Interpretation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample #‡; site (time in months) | Specimen type | Diagnosis (original → Δpost-review†) | IHC | ||||||

| TTF-1 | ΔNp63 | ||||||||

| 1 | 61M | 0 | 1) Spine (0) | Bx |

|

nd | nd | EGFR L858R | “SQCC” = component of AD-SQC |

| 2) Lung (−26) | Bx |

|

nd | nd | EGFR L858R | ||||

| 2 | 71F | 0 | 1) Lung, RLL (0) | Bx |

|

− | + | EGFR ex 1915 bp Δ | “SQCC” = component of AD-SQC |

| 2) Lung, RLL (−23) | Bx |

|

+ | nd | EGFR ex 1915 bp Δ | ||||

| 3 | 58M | 0 | 1) Bronchus (0) | Bx |

|

− | + | EGFR ex 19 15 bp Δ | “SQCC” = component of AD-SQC |

| 2) Lung, RUL (−9) | Bx |

|

nd | nd | EGFR ex 19 15 bp Δ | ||||

| 3) Lung, LLL (+21) | Bx |

|

+ | − | EGFR ex 19 15 bp Δ | ||||

| 4 | 45F | 0 | 1) Sacrum (0) | FNA |

|

− | + | EGFR ex 1915 bp Δ | “SQCC” = component of AD-SQC |

| 2) Lung (−17) | Pleural fluid |

|

+ | − | EGFR ex 1915 bp Δ | ||||

| 5 | 46M | 0 | 1) Lung (0) | FNA |

|

− | + | EGFR ex 19 9 bp Δ | “SQCC” = component of AD-SQC |

| 2) SCLN (+1) | Bx |

|

+ | − | EGFR ex 19 9 bp Δ | ||||

| 6 | 73M | 25 | 1) Adrenal (0) | Resection |

|

− | + | EGFR ex 19 18 bp Δ | “SQCC” = component of AD-SQC |

| 2) SCLN (−9) | Bx |

|

f¥ | f¥ | EGFR ex 19 18 bp Δ | ||||

| 7 | 68M | 45 | 1) Lung (0) | Lobectomy |

|

− | + | EGFR ex 1915 bp Δ | “SQCC” = component of AD-SQC |

| 2) Hilar LN (0) | Dissection |

|

+ | − | EGFR ex 1915 bp Δ | ||||

| 8 | 50M | 63 | 1) Skin (0) | FNA |

|

nd | nd | KRAS G12C | “SQCC” = component of AD-SQC |

| 2) Lung (−5) | FNA |

|

nd | nd | nd | ||||

| 3) SCLN (−5) | Bx |

|

− | f¥ | KRAS G12C | ||||

| 9 | 63F | 0 | 1) Lung, LUL (0) | Bx |

|

− | + | KRAS G12D | “SQCC” = component of AD-SQC |

| 2) Lung, LUL (0) | FNA |

|

nd | nd | nd | ||||

| 3) Lung, LUL (+5) | Lobectomy |

|

f¥ | f¥ | KRAS G12D | ||||

| 10 | 58M | 0 | 1) Bronchus (0) | Bx |

|

− | + | EGFR L858R | Indeterminate |

| 2) Spine (+1) | Bx |

|

− | + | nd | ||||

| 11 | 89F | 0 | Lung | Bx |

|

+ | − | EGFR L858R | “SQCC” = PD ADC |

| 12 | 56F | 31 | Lung | Lobectomy |

|

+ | − | EGFR ex 19 18 bp Δ | “SQCC” = PD ADC |

| 13 | 49F | 33 | Bronchus | Bx |

|

+ | − | KRAS G12V | “SQCC” = PD ADC |

| 14 | 69F | 34 | Hilar LN | FNA |

|

+ | − | KRAS G12V | “SQCC” = PD ADC |

| 15 | 63M | 80 | Bone | Bx |

|

− | − | KRAS G12S | “SQCC” = favor PD ADC |

| 16 | 58M | 51 | Lung | Bronchial excision |

|

f (5%)¥ | f (95%)¥ | KRAS G12C | “SQCC” = biphasic tumor with <10% glands |

Sample order is non-chronological: sample 1 represents an index case (EGFR/KRAS-mutant “SQCC”).

Review diagnosis was based on a combination of morphology and IHC; in the absence of IHC, tumor type was considered verified if morphology was diagnostic.

TTF-1 and ΔNp63 labeled distinct cell populations.

+diffusely positive, f focally positive, − negative, Δ deletion or change, ADC adenocarcinoma, AD-SQC adenosquamous carcinoma, Bx biopsy, bp base pair, ex exon, FNA fine needle aspiration, IHC immunohistochemistry, LN lymph node, LLL left lower lobe, LUL left upper lobe, nd not done (tissue insufficient or unavailable), PD poorly differentiated, Pt patient, PY pack years, RLL right lower lobe, SCLN supraclavicular lymph node, SQCC squamous cell carcinoma

In one group of patients (#1–10; n=10), the diagnosis of SQCC in the index sample was verified by morphologic and IHC reassessment. Remarkably, in all but one of these patients (#1–9; n=9), definitive evidence of glandular differentiation in the form of either ADC or AD-SQC was uncovered in second or third tissue samples from other sites or time-points. In most cases, the glandular component was apparent on conventional morphology, but in two cases (#1 and 8) a minor glandular component was revealed with the aid of IHC. Importantly, despite the distinct histologies, different samples from an individual patient harbored identical EGFR or KRAS mutations (whenever molecular data was available), indicating they were clonally-related and therefore represented components of a single AD-SQC. Paired samples represented primary tumor vs metastasis/recurrence (n=7), tumors at different metastatic sites (n=1), and preoperative biopsy vs same-site resection (n=1). The latter case (#9) was particularly informative in that it was comprised of a preoperative biopsy showing a KRAS-mutant “SQCC” with subsequent same-site resection revealing AD-SQC with 80% squamous and 20% glandular components, which directly confirmed that squamous histology in the biopsy represented incomplete sampling of AD-SQC. Interestingly, one case (#7) was a lobectomy in which the completely resected primary tumor was an EGFR-mutant SQCC whereas a hilar lymph node metastasis was ADC with an identical EGFR mutation. A thorough review of the primary tumor failed to uncover the evidence of glandular differentiation, suggesting that glandular metastases arose from a minor glandular component not represented in the sections of primary tumor used for microscopic evaluation (of note, there was no pathologic or clinicoradiologic evidence of another primary tumor in this patient). In this group, there was only a single patient (#10; never smoker) with the diagnosis of EGFR-mutant SQCC in two small biopsies, in whom evidence of ADC could not be identified in either sample. Because a resection of the primary tumor was not performed, the possibility of an underlying AD-SQC could not be either confirmed or excluded, and the final diagnosis was therefore considered “indeterminate”. Examples of microscopic findings for this group of patients are illustrated in Figure 1 (A–L).

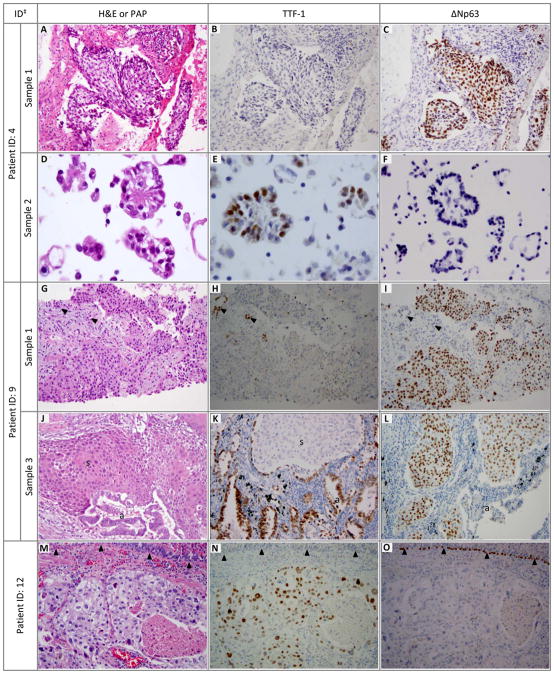

Figure 1. Microscopic features of EGFR/KRAS-mutant “squamous cell carcinomas” with a revised diagnosis of adenosquamous carcinoma or solid adenocarcinoma.

Patient 4 (A–F) and patient 9(D–I) illustrate incomplete sampling of AD-SQC leading to the diagnosis of “SQCC” with EGFR or KRAS mutations. While only squamous component was present in the index sample (core biopsies; A–C and G–I), glandular component was manifest in a cytology sample from another site (pleural fluid; D–F) or subsequent same-site resection (J–L). Glandular and squamous components have distinct morphology and ΔNp63/TTF-1 immunoprofiles as seen indifferent small samples (A–C vs D–F) or different areas of a resected tumor (J–L).

Patient12 (M–O) illustrates a solid growth pattern in ADC which resembles SQCC morphologically (“squamoid” or “pseudo-squamous” appearance), but it is readily identified as being of a glandular rather than squamous lineage by IHC.

‡ ID corresponds to patient and sample numbers in Table 4.

a adenocarcinoma component, s squamous component, H&E hematoxylin and eosin stain, PAP Papanicolaou stain; arrowheads in G–I – benign pneumocytes (TTF-1+), arrowheads in M–O – benign bronchial basal cells (ΔNp63+)

The other group of EGFR/KRAS-mutant “SQCC” (#11–15; n=5) consisted of poorly differentiated carcinomas with “squamoid” morphology but with ΔNp63/TTF-1immunoprofiles inconsistent with a diagnosis of SQCC, and instead supporting or favoring ADC. Similar to “SQCC” excluded from the mutation screen described above, these were poorly differentiated carcinomas with solid histology resembling SQCC but lacking keratinization or intercellular bridges (Figure 1 M-0).

In addition to the above two groups, case #16(KRAS-mutant “SQCC”) was a tumor with squamous and glandular components, but in which glands occupied only 5% of the tumor mass. This tumor was, as a result, classified as SQCC based on the World Health Organization (WHO) 2004 definition of AD-SQC requiring >10% of each component (24).

The above findings are summarized in Table 5. Overall, of 16 cases with the diagnosis of “SQCC” harboring EGFR/KRAS mutations, 10 (63%) were reclassified as AD-SQC (including the tumor with 5% glandular component), 5 (31%) as ADC, and one case (6%) was indeterminate. Notably, the majority (7/10; 70%) of patients with EGFR-mutant “SQCC” were never-smokers.

Table 5.

Reassessment of 16 EGFR/KRAS-mutant “squamous cell carcinomas” identified by routine clinical genotyping: Summary.

| Characteristic# | N (%) |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Specimen type | |

| - Small specimen (biopsy or cytology) | 12 (75) |

| - Surgical resection | 4 (25) |

|

| |

| Tumor site | |

| - Lung primary | 8 (50) |

| - Metastasis (lymph node, adrenal, bone, skin) | 6 (38) |

| - Recurrence | 2 (11) |

|

| |

| Interpretation after morphologic and IHC reassessment | |

| - Reclassified as AD-SQC§ | 10 (63) |

| - Reclassified as solid ADC by IHC | 5 (31) |

| - Indeterminate | 1 (6) |

|

| |

| Smoking status by mutation | |

| - EGFR-mutant “SQCC” | 10 (63) |

| ▪ Never | 7 |

| ▪ Current or former | 3 |

| - KRAS-mutant “SQCC” | 6 (37) |

| ▪ Never | 1 |

| ▪ Current or former | 5 |

Data for index samples (EGFR/KRAS-mutant “SQCC”), correspondingtosamples#1 in Table 4.

Includes patients with a small biopsy/cytology diagnosis of “SQCC” in an index sample, but evidence of glandular differentiation in other (non-index) tissue sample(s) (n=9), and one resected tumor with 5% glandular component.

ADC adenocarcinoma, AD-SQC adenosquamous carcinoma, IHC immunohistochemistry, SQCC squamous cell carcinoma

DISCUSSION

In this study, we combined mutational analysis of lung cancers diagnosed as SQCC with rigorous IHC-assisted pathologic verification in an attempt to resolve the persistent controversy regarding the occurrence of EGFR/KRAS mutations in this tumor type. The main finding of this study is that EGFR/KRAS mutations do not occur in pure biomarker-verified SQCC, and that the main culprits responsible for the detection of these mutations in samples diagnosed as “SQCC” are1) incomplete sampling of AD-SQC and 2) poorly-differentiated ADC morphologically mimicking SQCC. In addition to addressing the above controversy, we used a highly homogeneous series of IHC-verified SQCC to investigate the rate of mutations in other signaling molecules, for which targeted agents are either available or are at various stages of clinical development.

While the possibility that incomplete sampling of an underlying AD-SQC is a potential culprit for the detection of EGFR/KRAS mutations in samples diagnosed as “SQCC” has been suggested by several investigators in the past (2, 25), our data provide direct supporting evidence for this hypothesis. AD-SQC is uncommon but harbors a similar rate of EGFR/KRAS mutations as ADC (25–30), with our data supporting previous observations that these mutations are present uniformly in both the glandular and squamous components of this tumor type (25–29). These findings indicate that squamous histology per se is not incompatible with EGFR/KRAS mutations, but that these mutations are restricted to squamous histology that represents a component of AD-SQC, whereas they are not a feature of pure SQCC. Notably, this situation in SQCC is remarkably similar to the findings in small cell lung carcinoma (SCLC). While EGFR/KRAS mutations are not a feature of SCLC in general, these mutations may be present in SCLC that has a clonal relationship with ADC, as seen in rare instances when SCLC is combined with ADC or in recently-described small cell transformation of ADC after prolonged treatment with EGFR TKIs (32–36). These findings suggest that EGFR/KRAS-mediated tumorigenesis is specific to progenitor/stem cells giving rise to ADC, but that subsequent (or inherent) clonally-related phenotypic divergence accounts for the occasional detection of these mutations in unexpected histologies. Other than the presence of ADC-specific mutations, both SQCC and SCLC arising from ADC are otherwise morphologically and immunophenotypically identical to their pure counterparts. The analysis of driver mutations can provide insights into tumor origin and clonal relationships in these settings.

As mentioned above, a key issue with the diagnosis of AD-SQC is that small biopsy or cytology specimens may contain only one of the two histologic components. A further diagnostic challenge is that metastases derived from AD-SQC sometimes consist entirely of a single histology (37, 38), as exemplified by case 6 in this study. These factors make it impossible to determine whether squamous histology in a small biopsy or even a meta stasectomy represents a true SQCC vs a component of AD-SQC. On the other hand, because AD-SQC is a rare tumor, the diagnosis of SQCC in a small specimen is statistically very likely to represent true SQCC (as discussed below, a patient’s clinical characteristics, particularly the never-smoker status, may serve as a clue to an underlying AD-SQC). Although these challenges in the diagnosis of AD-SQC in clinical samples are well known (24), that they are the main culprits leading to conflicting molecular data in SQCC has not been previously well documented. This study illustrates that a comprehensive pathologic analysis of all specimens from different sites and time-points from individual patients can reveal both squamous and glandular differentiation in the majority of patients. Furthermore, we show that while IHC cannot circumvent the issue of incomplete sampling, it can improve the diagnosis of AD-SQC in a subset of cases.

The second culprit that we identified as a cause for the conflicting data surrounding EGFR/KRAS mutations in SQCC is the ability of poorly-differentiated ADC to grow in a solid pattern closely mimicking SQCC (i.e. “squamoid” or “pseudo-squamous” appearance). We show that the cell lineage in areas with this ambiguous appearance is readily clarified by IHC for ΔNp63 and TTF-1, but that interpretation in the absence of IHC may lead to an erroneous diagnosis of “SQCC” harboring EGFR/KRAS mutations. This is an under-recognized morphologic feature in lung ADC, which may be present either focally or as a predominant pattern, and we show here that it may present a diagnostic pitfall in both small specimens and resected tumors. These findings validate the value of IHC, which is becoming widely incorporated into clinical practice in recent years, for the diagnosis of morphologically-challenging NSCLC and for assuring homogeneity of tumor types included in molecular studies. It is of note that, while immunomarkers used in this study are not new, their application to clinical samples was characterized in detail only recently (15–19). We should also emphasize that IHC is not required for the diagnosis of all SQCC; in the majority of cases the line of differentiation is evident based on morphology, and IHC is only needed for a minority of cases that are poorly-differentiated and have equivocal morphology.

The third and least common cause of conflicting molecular data is the definition of AD-SQC itself, which requires that both glandular and squamous components represent at least 10% of the tumor mass (24). This arbitrarily-selected criterion predates the new molecular data showing that any amount of glandular differentiation, even less than 10%, appears to be a harbinger of ADC-specific driver mutations. Similar to our KRAS-mutant “SQCC” in which glands represented 5% of the tumor (case #16), detection of EGFR mutation in “SQCC” with <10% glands has been described by Ohtsuka et al (26). Therefore any amount of glandular differentiation should qualify a tumor for EGFR/KRAS genotyping.

The potential contribution of the above diagnostic challenges to the previous reports of EGFR/KRAS mutations in SQCC is difficult to estimate. The vast majority of reported patients with EGFR-mutant SQCC had advanced disease (where the diagnosis is typically based on small specimens), and many patients were never-smokers (6, 8, 10), suggesting that, similar to this study, those cases may have represented incompletely sampled AD-SQC. Interestingly, one recent study used a similar approach of combining IHC-based diagnosis verification with EGFR mutation testing in a series of 85 resected SQCC (9). A total of 5 EGFR-mutant tumors were identified, of which 2 were re-classified by IHC as AD-SQC and ADC, whereas 3 tumors were verified as SQCC. These latter cases may be similar to case#7in our series, in which whole tissue sections of the primary tumor showed only SQCC (by morphology and IHC) though a hilar lymph node metastas is showed ADC that harbored an identical EGFR mutation as the primary tumor, supporting their clonal relationship. This suggests that in rare cases under sampling of AD-SQC is possible even in whole tissue sections, which may occur because large tumors are examined representatively in pathology laboratories, and therefore a minorglandular component may not be represented in microscopically-scrutinized tissue.

A potential criticism of this study is that although no EGFR/KRAS mutations were identified in the screen of 95IHC-verifiedpure SQCC, one cannot exclude the possibility of low-frequency mutations in these genes falling within the confidence intervals of this study (95% CI 0–3.8%). However, our conclusions are in equal part supported by the findings that none of the “SQCC” with EGFR/KRAS mutations identified in our clinical practice could be confirmed to represent true (i.e. pure) SQCC. Detailed pathologic review, incorporating the modern IHC methods, of EGFR/KRAS-mutant carcinomas diagnosed as SQCC at other institutions will be needed to validate the conclusions reached in this study.

What are the implications of our findings for clinical practice? The current recommendation in the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines is to exclude SQCC from EGFR/KRAS mutation testing (39). Our findings support this recommendation for SQCC diagnosed in a surgically resected primary tumor (where under-sampling of AD-SQC is highly unlikely). On the other hand, testing patients with SQCC diagnosed in small biopsy or cytology specimens (where the possibility of an underlying AD-SQC cannot be excluded) should be guided by clinical parameters. In particular, similar to ADC, EGFR mutations in AD-SQC are associated with a never-smoker status (25, 30), whereas the lack of smoking history is unusual for patients with a true SQCC [2% in this study, 1–3% in other studies (5, 9, 40)]. Indeed, the majority of patients with EGFR-mutant “SQCC” with a revised diagnosis of ADC or AD-SQC in this study were never-smokers. We therefore suggest that patients that receive a diagnosis of SQCC based on a small biopsy and who do not have a history of smoking are likely to have an underlying mixed tumor and should be tested for EGFR/KRAS mutations. Detailed clinical analysis of the patients in this series, including their EGFR TKI sensitivity, will be reported separately (Paik et al, in preparation).

The specificity of EGFR/KRAS mutations for carcinomas with glandular differentiation (ADC and AD-SQC), and strict exclusion of these mutations from pure SQCC provides an interesting insight into the histogenetic relationship of these tumors. In the past, it has been questioned whether lung ADC and SQCC represent truly distinct entities vs a spectrum of related tumors (41). The sharp divide in tumor-initiating mutations provides a strong support for the distinct molecular pathogenesis of pure SQCC compared to tumors with glandular differentiation. The biological underpinnings of specificity for ADC of EGFR/KRAS and several other driver mutations in NSCLC, including BRAF (42) and EML4-ALK (43), remain to be elucidated, but these findings are in line with lineage-restriction of many other somatic genetic alterations across human tumors (44).

Lastly, in this study we used a rigorously verified series of pure SQCC to investigate the rate of mutations in other important signaling molecules. We found a low frequency of PIK3CA (4%) and AKT1 (1%) mutations, which is in agreement with prior studies showing a 2–4%rate of PIK3CA mutations (45–47) and a ~1% rate of AKT1 mutations (48, 49) in NSCLC. Prior studies have shown that PIK3CA mutations occur in both ADC and SQCC, but are more common in SQCC. Importantly, several PI3Kand AKT1 inhibitors are in early clinical development (50), and screening of lung SQCC for these mutations may be used in the future to select patients for targeted therapies.

In conclusion, we present compelling evidence that EGFR/KRAS mutations have a strong specificity for carcinomas with glandular differentiation, whereas they are not a feature of pure SQCC. We describe several pitfalls in the traditional pathologic diagnosis of NSCLC subtypes that can lead to conflicting genotype data, and illustrate how comprehensive pathologic assessment utilizing biomarker expression can clarify the tumor lineage and resolve a typical molecular findings. Our results support incorporating this approach into routine clinical practice and future clinicopathologic and molecular studies.

Supplementary Material

STATEMENT OF TRANSLATIONAL RELEVANCE.

There is significant variability in the reported prevalence of EGFR/KRAS mutations in squamous cell carcinoma (SQCC) of lung, which has raised a concern regarding the pathologic homogeneity of the tumors included in molecular studies. Here we combined mutational analysis with rigorous pathologic verification utilizing immunohistochemistry (IHC). We find that EGFR/KRAS mutations do not occur in pure biomarker-verified SQCC, and occasional detection of these mutations in cases reported as “SQCC” is a result of difficulties in the pathologic diagnosis of adenocarcinoma and adenosquamous carcinoma, which in the majority of cases can be resolved by comprehensive pathologic assessment incorporating IHC. The translational relevance is three-fold. First, we highlight the value of IHC in the diagnosis of SQCC, which clarifies the conflicting data on the spectrum of mutations in this tumor type. Second, we establish a sharp biological divide in the patterns of oncogenic driver mutations between lung adenocarcinoma (pure or combined) vs pure SQCC. Third, we determine the rate of several targetable mutations in a pathologically homogeneous set of SQCC.

Acknowledgments

Financial support: NIH: P01 CA129243 (to M.L., M.G.K.)

We thank Dr Laetitia Borsu and Angela Marchetti for assistance with Sequenom assays. The MSKCC Sequenom facility was supported by the Anbinder Fund.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: none to disclose

References

- 1.Selvaggi G, Scagliotti GV. Histologic subtype in NSCLC: does it matter? Oncology (Williston Park) 2009;23:1133–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ladanyi M, Pao W. Lung adenocarcinoma: guiding EGFR-targeted therapy and beyond. Mod Pathol. 2008;21 (Suppl 2):S16–22. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3801018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rodenhuis S, Slebos RJ. Clinical significance of ras oncogene activation in human lung cancer. Cancer Res. 1992;52:2665s–9s. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marchetti A, Martella C, Felicioni L, Barassi F, Salvatore S, Chella A, et al. EGFR mutations in non-small-cell lung cancer: analysis of a large series of cases and development of a rapid and sensitive method for diagnostic screening with potential implications on pharmacologic treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:857–65. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.08.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee SY, Kim MJ, Jin G, Yoo SS, Park JY, Choi JE, et al. Somatic mutations in epidermal growth factor receptor signaling pathway genes in non-small cell lung cancers. J Thorac Oncol. 2010;5:1734–40. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181f0beca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chou TY, Chiu CH, Li LH, Hsiao CY, Tzen CY, Chang KT, et al. Mutation in the tyrosine kinase domain of epidermal growth factor receptor is a predictive and prognostic factor for gefitinib treatment in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:3750–7. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Park SH, Ha SY, Lee JI, Lee H, Sim H, Kim YS, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor mutations and the clinical outcome in male smokers with squamous cell carcinoma of lung. J Korean Med Sci. 2009;24:448–52. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2009.24.3.448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pallis AG, Voutsina A, Kalikaki A, Souglakos J, Briasoulis E, Murray S, et al. ‘Classical’ but not ‘other’ mutations of EGFR kinase domain are associated with clinical outcome in gefitinib-treated patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Br J Cancer. 2007;97:1560–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miyamae Y, Shimizu K, Hirato J, Araki T, Tanaka K, Ogawa H, et al. Significance of epidermal growth factor receptor gene mutations in squamous cell lung carcinoma. Oncol Rep. 2011;25:921–8. doi: 10.3892/or.2011.1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim KS, Jeong JY, Kim YC, Na KJ, Kim YH, Ahn SJ, et al. Predictors of the response to gefitinib in refractory non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:2244–51. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vachtenheim J, Horakova I, Novotna H, Opaalka P, Roubkova H. Mutations of K-ras oncogene and absence of H-ras mutations in squamous cell carcinomas of the lung. Clin Cancer Res. 1995;1:359–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Le Calvez F, Mukeria A, Hunt JD, Kelm O, Hung RJ, Taniere P, et al. TP53 and KRAS mutation load and types in lung cancers in relation to tobacco smoke: distinct patterns in never, former, and current smokers. Cancer Res. 2005;65:5076–83. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Travis WD, Rekhtman N, Riley GJ, Geisinger KR, Asamura H, Brambilla E, et al. Pathologic diagnosis of advanced lung cancer based on small biopsies and cytology: a paradigm shift. J Thorac Oncol. 2010;5:411–4. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181d57f6e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rekhtman N, Ang DC, Sima CS, Travis WD, Moreira AL. Immunohistochemical algorithm for differentiation of lung adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma based on large series of whole-tissue sections with validation in small specimens. Mod Pathol. 2011;24:1348–59. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2011.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pelosi G, Rossi G, Bianchi F, Maisonneuve P, Galetta D, Sonzogni A, et al. Immunhistochemistry by Means of Widely Agreed-Upon Markers (Cytokeratins 5/6 and 7, p63, Thyroid Transcription Factor-1, and Vimentin) on Small Biopsies of Non-small Cell Lung Cancer Effectively Parallels the Corresponding Profiling and Eventual Diagnoses on Surgical Specimens. J Thorac Oncol. 2011;6:1039–49. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e318211dd16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mukhopadhyay S, Katzenstein AL. Subclassification of non-small cell lung carcinomas lacking morphologic differentiation on biopsy specimens: Utility of an immunohistochemical panel containing TTF-1, napsin A, p63, and CK5/6. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35:15–25. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3182036d05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Righi L, Graziano P, Fornari A, Rossi G, Barbareschi M, Cavazza A, et al. Immunohistochemical subtyping of non small cell lung cancer not otherwise specified in fine-needle aspiration cytology: A retrospective study of 103 cases with surgical correlation. Cancer. 2011;117:3416–23. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bishop JA, Teruya-Feldstein J, Westra WH, Pelosi G, Travis WD, Rekhtman N. p40 (ΔNp63) is superior to p63 for the diagnosis of pulmonary squamous cell carcinoma. Mod Pathol. 2011 doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2011.173. In Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pelosi G, Fabbri A, Bianchi F, Eng PM, Tamborini E, Rossi G, et al. D (delta) Np63 (p40) and Thyroid Transcription Factor-1 (TTF1) Immunoreactivity upon Small Biopsies or Cellblocks for Typing Non-small Cell Lung Cancer: A Novel Two-hit, Sparing-Material Approach. J Thor Oncol. 2011 doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31823815d3. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nicholson AG, Gonzalez D, Shah P, Pynegar MJ, Deshmukh M, Rice A, et al. Refining the diagnosis and EGFR status of non-small cell lung carcinoma in biopsy and cytologic material, using a panel of mucin staining, TTF-1, cytokeratin 5/6, and P63, and EGFR mutation analysis. J Thorac Oncol. 2010;5:436–41. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181c6ed9b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rekhtman N, Brandt SM, Sigel CS, Friedlander MA, Riely GJ, Travis WD, et al. Suitability of thoracic cytology for new therapeutic paradigms in non-small cell lung carcinoma: high accuracy of tumor subtyping and feasibility of EGFR and KRAS molecular testing. J Thorac Oncol. 2011;6:451–8. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31820517a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McLean EC, Monaghan H, Salter DM, Wallace WA. Evaluation of adjunct immunohistochemistry on reporting patterns of non-small cell lung carcinoma diagnosed histologically in a regional pathology centre. J Clin Pathol. 2011 doi: 10.1136/jcp.2011.090571. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Travis WD, Brambilla E, Noguchi M, Nicholson AG, Geisinger KR, Yatabe Y, et al. International association for the study of lung cancer/american thoracic society/european respiratory society international multidisciplinary classification of lung adenocarcinoma. J Thorac Oncol. 2011;6:244–85. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e318206a221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Travis WD, Brambilla E, Muller-Hermelink HK, Harris CC, editors. Pathology & Genetics: Tumours of the Lung, Pleura, Thymus and Heart. Lyon: IARC Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kang SM, Kang HJ, Shin JH, Kim H, Shin DH, Kim SK, et al. Identical epidermal growth factor receptor mutations in adenocarcinomatous and squamous cell carcinomatous components of adenosquamous carcinoma of the lung. Cancer. 2007;109:581–7. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ohtsuka K, Ohnishi H, Fujiwara M, Kishino T, Matsushima S, Furuyashiki G, et al. Abnormalities of epidermal growth factor receptor in lung squamous-cell carcinomas, adenosquamous carcinomas, and large-cell carcinomas: tyrosine kinase domain mutations are not rare in tumors with an adenocarcinoma component. Cancer. 2007;109:741–50. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Toyooka S, Yatabe Y, Tokumo M, Ichimura K, Asano H, Tomii K, et al. Mutations of epidermal growth factor receptor and K-ras genes in adenosquamous carcinoma of the lung. Int J Cancer. 2006;118:1588–90. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tochigi N, Dacic S, Nikiforova M, Cieply KM, Yousem SA. Adenosquamous carcinoma of the lung: a microdissection study of KRAS and EGFR mutational and amplification status in a western patient population. Am J Clin Pathol. 2011;135:783–9. doi: 10.1309/AJCP08IQZAOGYLFL. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jia XL, Chen G. EGFR and KRAS mutations in Chinese patients with adenosquamous carcinoma of the lung. Lung Cancer. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2011.04.005. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sasaki H, Endo K, Yukiue H, Kobayashi Y, Yano M, Fujii Y. Mutation of epidermal growth factor receptor gene in adenosquamous carcinoma of the lung. Lung Cancer. 2007;55:129–30. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2006.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.D’Angelo SP, Park B, Azzoli CG, Kris MG, Rusch V, Ladanyi M, et al. Reflex testing of resected stage I through III lung adenocarcinomas for EGFR and KRAS mutation: report on initial experience and clinical utility at a single center. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;141:476–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2010.08.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tatematsu A, Shimizu J, Murakami Y, Horio Y, Nakamura S, Hida T, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor mutations in small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:6092–6. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fukui T, Tsuta K, Furuta K, Watanabe S, Asamura H, Ohe Y, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor mutation status and clinicopathological features of combined small cell carcinoma with adenocarcinoma of the lung. Cancer Sci. 2007;98:1714–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2007.00600.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zakowski MF, Ladanyi M, Kris MG. EGFR mutations in small-cell lung cancers in patients who have never smoked. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:213–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc053610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sequist LV, Waltman BA, Dias-Santagata D, Digumarthy S, Turke AB, Fidias P, et al. Genotypic and histological evolution of lung cancers acquiring resistance to EGFR inhibitors. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3:75ra26. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rekhtman N, Marchetti A, Lau C, Moreira AL, Travis WD, Zakowski M, et al. Analysis of EGFR and KRAS mutations in small cell carcinoma and large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of lung. J Thor Oncol. 2011;6 (Supplement 2):S346. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Takamori S, Noguchi M, Morinaga S, Goya T, Tsugane S, Kakegawa T, et al. Clinicopathologic characteristics of adenosquamous carcinoma of the lung. Cancer. 1991;67:649–54. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19910201)67:3<649::aid-cncr2820670321>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shimizu J, Oda M, Hayashi Y, Nonomura A, Watanabe Y. A clinicopathologic study of resected cases of adenosquamous carcinoma of the lung. Chest. 1996;109:989–94. doi: 10.1378/chest.109.4.989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Guidelines: Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Version 3.2011. National Comprehensive Cancer Network; Fort Washington, PA: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sakurai H, Asamura H, Watanabe S, Suzuki K, Tsuchiya R. Clinicopathologic features of peripheral squamous cell carcinoma of the lung. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;78:222–7. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2004.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yesner R. The dynamic histopathologic spectrum of lung cancer. Yale J Biol Med. 1981;54:447–56. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marchetti A, Felicioni L, Malatesta S, Grazia Sciarrotta M, Guetti L, Chella A, et al. Clinical features and outcome of patients with non-small-cell lung cancer harboring BRAF mutations. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:3574–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.9638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Takahashi T, Sonobe M, Kobayashi M, Yoshizawa A, Menju T, Nakayama E, et al. Clinicopathologic features of non-small-cell lung cancer with EML4-ALK fusion gene. Annals of surgical oncology. 2010;17:889–97. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0808-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Garraway LA, Sellers WR. Lineage dependency and lineage-survival oncogenes in human cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:593–602. doi: 10.1038/nrc1947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yamamoto H, Shigematsu H, Nomura M, Lockwood WW, Sato M, Okumura N, et al. PIK3CA mutations and copy number gains in human lung cancers. Cancer Res. 2008;68:6913–21. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kawano O, Sasaki H, Endo K, Suzuki E, Haneda H, Yukiue H, et al. PIK3CA mutation status in Japanese lung cancer patients. Lung Cancer. 2006;54:209–15. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2006.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Samuels Y, Wang Z, Bardelli A, Silliman N, Ptak J, Szabo S, et al. High frequency of mutations of the PIK3CA gene in human cancers. Science. 2004;304:554. doi: 10.1126/science.1096502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Malanga D, Scrima M, De Marco C, Fabiani F, De Rosa N, De Gisi S, et al. Activating E17K mutation in the gene encoding the protein kinase AKT1 in a subset of squamous cell carcinoma of the lung. Cell Cycle. 2008;7:665–9. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.5.5485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Do H, Salemi R, Murone C, Mitchell PL, Dobrovic A. Rarity of AKT1 and AKT3 E17K mutations in squamous cell carcinoma of lung. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:4411–2. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.21.13654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pao W, Girard N. New driver mutations in non-small-cell lung cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:175–80. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70087-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.