Abstract

The cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA) mediates a myriad of cellular signaling events and its activity is tightly regulated both in space and time. Among these regulatory mechanisms is N-myristoylation, whose biological role has been elusive. Using a combination of thermodynamics, kinetics, and spectroscopic methods, we analyzed the effects of N-myristoylation and phosphorylation at Ser10 on the interactions of PKA with model membranes. We found that in the absence of lipids, the myristoyl group is tucked into the hydrophobic binding pocket of the enzyme (myr-in state). Upon association with lipid bilayers, the myristoyl group is extruded and inserts into the hydrocarbon region of the lipid bilayer (myr-out state). NMR data indicate that the enzyme undergoes conformational equilibrium between myr-in and myr-out states, which can be shifted either by interaction with membranes and/or phosphorylation at Ser10. Our results provide evidence that the membrane binding motif of myristoylated PKA-C steers the enzyme towards lipids independent of its regulatory subunit or an A-kinase anchoring protein (AKAP), providing an additional mechanism to localize the enzyme near membrane-bound substrates.

Keywords: Protein Kinase A, N-myristoylation, peripheral membrane proteins, NMR spectroscopy, Deuterium NMR, Lipid Bicelles

INTRODUCTION

Protein kinase A (PKA) is a Ser/Thr phosphoryl transferase that transfers the γ-phosphate group of ATP to protein substrates1. PKA phosphorylates more than 100 cytoplasmic and membrane associated targets2. The catalytic subunit (PKA-C) is a bean shaped molecule of 350 amino acids, with a highly conserved core spanning residues 40–3003. The catalytic activity of PKA-C is tightly regulated both in space and time via binding partners, including the PKA regulatory subunits (R-subunits, which form the inactive holoenzyme), A-kinase anchoring proteins (AKAPs)4, and the endogenous protein kinase inhibitor (PKI)5. In addition to regulation by other proteins, a cluster of posttranslational modifications at the N-terminus may fine tune enzyme activity, regulation, and localization. These modifications include phosphorylation at Ser10, deamidation at Asn2, and myristoylation at Gly16.

Myristoylation of PKA-C implies the covalent linkage of a tetradecanoyl lipid group to the N-terminal Gly1 of the protein, catalyzed by N-myristoyl transferase (NMT, E.C 2.3.1.97). Myristoylation has often been associated with membrane targeting7. However, myristoylation may actively participate in protein kinase activation or deactivation. For instance, a myristoyl/phosphotyrosine switch has been proposed as an integral part of the regulatory cycle of the c-Abelson (c-Abl) tyrosine kinase8, where N-myristoylation modulates the activity of the enzyme by gating the effects of the SH2 domain8. In contrast, myristoylation of c-Src kinase has a positive effect on catalytic activity and, together with membrane binding, may regulate enzyme ubiquitination and degradation9. Therefore, myristoylation may have varying effects on protein kinase function and tune different signaling events regulated by these enzymes.

Thermal denaturation studies of myristoylated PKA-C (myr(+)PKA-C) show that N-myristoylation confers higher stability when compared to non-myristoylated PKA-C (myr(−)PKA-C)10. On the other hand, phosphorylation kinetic experiments with Kemptide (a soluble standard substrate) show that the catalytic efficiency of myr(+)PKA-C is indistinguishable to that of myr(−)PKA-C10. Comparison of X-ray structures of both mammalian and recombinant PKA-C show that the N-terminus of the protein kinase is essentially disordered in the absence of myristoylation, and becomes helical and ordered upon myristoylation11. In the crystal structure, the myristoyl group of myr(+)PKA-C is retracted in a hydrophobic pocket of the protein kinase far away from the entrance of the active site11. The aliphatic chain of the myristoyl group stretches within this hydrophobic pocket, connecting the large lobe to the small lobe, and making contacts with a number of peripheral segments in the enzyme10. These segments include the A-helix, the apex of a loop connecting the C-helix with β-strand 4, the E-helix, and the C-terminal tail11.

Although biophysical and high-resolution studies offer a view of how stability can be afforded by positioning the myristoyl group within the catalytic core of myr(+)PKA-C, mechanistic data regarding the role of the myristoyl group in substrate recognition and modulation of catalytic function at the membrane interface are still lacking. In fact, localization and structural studies of myr(+)PKA-C in the presence of a lipid membrane are limited to short myristoylated peptides, corresponding to the N-terminal portion of the protein kinase821 12; 2597 13. Based on these data, it has been hypothesized that both myristoylation and a basic face of an amphipathic helix at the N-terminus of myr(+)PKA-C steer the enzyme toward the membrane to recognize and phosphorylate membrane-bound substrates12. Also, structural disorder induced upon Ser 10 phosphorylation in a peptide corresponding to the N-terminus of myr(+)PKA-C has been proposed as a subsidiary control on the protein kinase to bind lipid membranes13. These results are quite intriguing and open up the possibility that membrane association of PKA-C is controlled by a myristoyl/phosphoserine switch14. Other reports have proposed the necessity of accessory or regulatory proteins to target myr(+)p(−)PKAC to the membrane15. Specifically, fluorescence data support the role of R-subunit type II to form an isoform-specific switch in myr(+)p(−)PKA-C which causes it to target cellular membranes15. Also, the identification of AKAPs in the role of PKA-C membrane localization4 has opened new questions regarding the exact functional role of myristoylation. How does the conformation of the myristoylated and phosphorylated PKA-C peptides compare to the full-length enzyme in solution and in the presence of membranes? Could the myristoyl hydrophobic pocket act as an allosteric site?

In this paper, we analyzed the role of N-myristoylation and its structural coupling with Ser10 phosphorylation in the context of lipid membranes for full-length PKA-C. These studies were made possible thanks to homogenously myristoylated samples prepared using in vitro site specific ligation chemistry, which enabled the production of isotopically labeled myr(+)PKA-C for biophysical and structural studies. In this manner, myr(+)PKA-C could be obtained in milligram quantities with or without S10 phosphorylation. Using a combination of isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC), differential scanning calorimetry (DSC), circular dichroism (CD), steady-state kinetics, and NMR spectroscopy, we found a conformational switch in myr(+)PKA-C which is modulated by S10 phosphorylation or membrane interactions. These data confirm the previously proposed mechanism of myr(+)PKA-C interactions with the membrane15, while offering an atomistic view of the allosteric changes induced by both myristoylation and membrane binding in the enzyme's active site.

RESULTS

Folding, stability, and function of in vitro myristoylated PKA-C

The production of recombinantly expressed myristoylated PKA-C has been previously accomplished by co-expression of NMT and PKA-C in E. coli bacteria10, 16. This procedure results in a mixture of myristoylated PKA-C in two different phosphoisoforms, which are not phosphorylated at S10. In addition, a high level of NMT expression is obtained, which is difficult to separate from the kinase17. To avoid the difficulties associated with the separation of this complex mixture and provide an avenue to obtain myr(+)PKA-C with S10 phosphorylated (myr(+)p(+)PKA-C), or unphosphosphorylated (myr(+)p(−)PKA-C), we optimized a protocol for the myristoylation of myr(−)PKA-C phosphoisoforms in vitro. In this manner, we could utilize recombinantly expressed myr(−)PKA-C, which contains phosphorylated or unphosphorylated S10, to test the functional effects of myristoylation and N-terminal phosphorylation on the full-length enzyme.

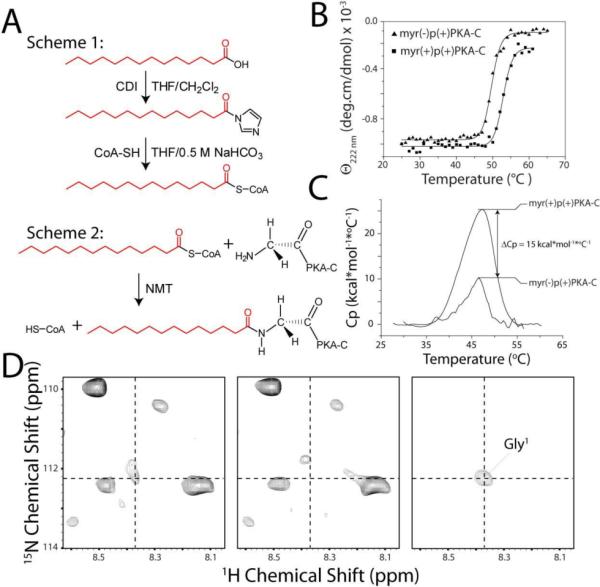

First, we synthesized myristoyl coenzyme A according to a previously published protocol (Figure 1A)18. Then, we carried out NMT catalyzed myristoylation by adding myr-CoA to myr(−)p(+)PKA-C or myr(−)p(−)PKA-C. The protocol required an extensive optimization of the experimental conditions by testing different detergents that would retain the solubility of the myristoylated product during the enzymatic reaction. However, since low nanomolar concentrations of NMT are sufficient for full myristoylation, isolation of the myristoylated product is more facile. After the reaction, the myristoylated product was separated from residual non-myristoylated PKA-C (less than ~2%) by ion exchange chromatography. The efficiency of the in vitro myristoylation of PKA-C was found to be >98% based on analytical HPLC or standard addition monitored by electrospray ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (ESI-TOF-MS).

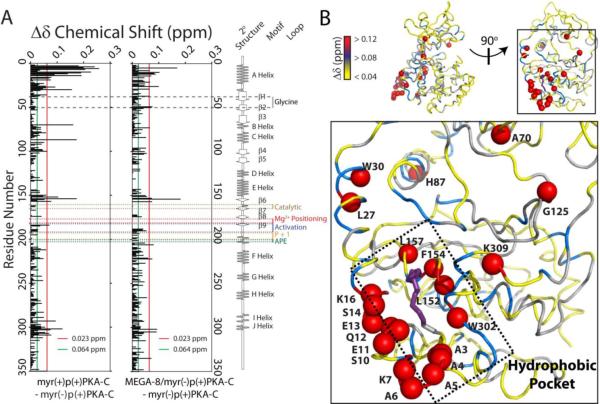

Figure 1.

Preparation and characterization of myr(+)p(+)PKA-C. A) Synthetic schemes for myristoylcoenzymeA and myr(+)p(+)PKA-C preparation. B) CD melting curves of PKA-C samples. N-myristoylation increases the enzyme thermostability by ~3 °C. C) DSC profiles of myr(+)p(+)PKA-C and myr(−)p(+)PKA-C. The difference in the enthalpy of unfolding is ~15 kcal*mol*°C−1, in favor of the myristoylated sample. D) 2D portions of the [1H/15N]-CCLS-HSQC experiments for the identification of the linkage between the myristic group, labeled at 1-13C, and Gly1. Experimental conditions are detailed on the methods section.

The covalent attachment of the myristoyl group to PKA-C and subsequent changes in the physical properties of the enzyme were confirmed by 1) ESI-TOF-MS, 2) thermal melting, and 3) NMR spectroscopy. For myr(+)p(+)PKA-C, the mass spectrum of the purified product is shifted by an additional 211 a.m.u. (corresponding to the myristoyl group, Figure S1 and Table 1). The CD spectra of myr(−)p(+)PKA-C and myr(+)p(+)PKA-C showed the same profile (Figure S2), consistent with the small structural changes observed by X-ray crystallography6. However, thermal metling (Tm) monitored by CD spectroscopy showed an increase of 3.2 °C for myr(+)p(+)PKA-C over myr(−)p(+)PKA-C (Figure 1B), as shown previously for recombinantly expressed myr(+)p(−)PKA-C10. This was further verified by differential scanning calorimetry, which revealed a ΔCp of ~15 kcal/mol between myr(+)p(+)PKA-C and myr(−)p(+)PKA-C, and a shift of ~3 °C in melting point (Figure 1C).

Table 1.

Kinetic and thermodynamics parameters of myr(+)p(+)PKA-C and myr(−)p(+)PKA-C.

| myr(−)p(+)PKA-C | myr(+)p(+)PKA-C | |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Mass (a.m.u.) | 40,685 | 40,896 |

| KM (μM)* | 40 ± 9 | 41 ± 3 |

| Vmax (μM/s)* | 0.20 ± 0.02 | 0.21 ± 0.01 |

| kcat (S−1)* | 20 ± 2 | 21 ± 1 |

| (μM) | 20.1 ± 4.0 | 24.1 ± 0.4 |

| Tm (°C) | 49.7 ± 0.1 | 52.9 ± 0.1 |

Steady-state kinetic measurements were performed with the standard soluble substrate, Kemptide.

The N-terminal covalent attachment of the myristoyl group in myr(+)p(+)PKA-C was confirmed by NMR spectroscopy. Specifically, we used the [1H/15N]-CCLS-HSQC19 on a myr(+)p(+)PKA-C sample, which contained uniform 15N labeling and 13C labeling only at the C-1 position of the myristoyl moiety. The CCLS pulse sequence allows the detection of amide resonances linked to 15N-13C' pairs. It consists of the acquisition of a control [1H/15N]-HSQC 13C'-decoupled spectrum with constant time evolution of the 15N magnetization; and a suppression spectrum, where 15N resonances coupled to 13C' (in this case the 13C-1 of the myristoyl group) become suppressed. The subtraction of the two spectra results in a subspectrum with only the amide resonances linked to 13C carbonyl carbons detected. For myr(+)p(+)PKA-C, the difference spectrum revealed a single 1H-15N resonance, which corresponded to the G1 amide covalently attached to the myristoyl group (Figure 1D).

To test the structural integrity and the activity of myr(−)p(+)PKA-C and myr(+)p(+)PKA-C, we carried out kinetics and thermodynamic assays. A summary of these kinetic and thermodynamic parameters is reported in Table 1. In particular, we tested nucleotide binding affinity by isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) measurements and the catalytic phosphorylation efficiency with the standard substrate, Kemptide. ITC measurements showed that both myr(−)p(+)PKA-C and myr(+)p(+)PKA-C have identical dissociation constants (Kd) for adenosine diphosphate (ADP), with similar thermodynamic properties (Figure S2). As for the recombinantly expressed myr(+)p(−)PKA-C10, the catalytic efficiency for myr(+)p(+)PKA-C and myr(−)p(+)PKA-C is nearly identical, having similar values of kcat (~20 s−1) and Km (~40 μM)10. Taken together, the experimental data from CD, thermal melting, phosphorylation kinetics and nucleotide binding indicate that the in vitro myristoylation protocol preserved the overall fold, activity and nucleotide binding properties of the enzyme.

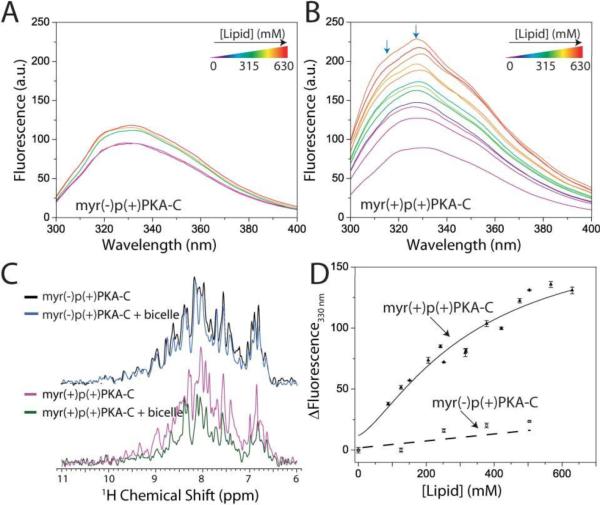

The [1H/15N] TROSY-HSQC spectra of ADP bound myr(−)p(+)PKA-C and ADP bound myr(+)p(+)PKA-C had very similar amide fingerprints, consistent with the identical CD profiles observed. The differences in the amide fingerprint are mainly due to the hydrophobic myristoyl group. This was verified by titrations of MEGA-8 into samples containing 15N-labeled myr(−)p(+)PKA-C, and measuring the amide shifts in the TROSY-HSQC NMR spectra. MEGA-8 is a myristoyl group analogue and a crystal structure of myr(−)p(−)PKA-C bound to MEGA-8 showed that it occupied the same hydrophobic pocket as the myristoyl group in myr(+)p(−)PKA-C20. The NMR spectrum of MEGA-8 bound myr(−)p(+)PKA-C was nearly superimposable with myr(+)p(+)PKA-C, with only small differences in the extent of changes in chemical shifts. Therefore, the assignment myr(+)p(+)PKA-C was facilitated by the comparison with the NMR spectrum of myr(−)PKA-C with MEGA-8 bound myr(−)p(+)PKA-C. A plot of the 1H/15N combined chemical shift perturbations (Δδ) for the presence of the covalently attached myristoyl group or MEGA-8 is reported in Figure 2A. The largest changes (Δδ ~0.1–0.15 ppm) caused by the myristoyl group are mainly clustered at the hydrophobic pocket of the enzyme, formed between the large lobe and the N-terminal A-helix (Figure 2B). These perturbations are also present in the E helix and for several residues that have been predicted to contact the myristoyl group in the crystal structure of myr(+)p(−)PKA-C (Protein Database:1CMK21), or MEGA-8 bound myr(−)p(−)PKAC (PDB:1SMH14). In addition to local perturbations, significant changes were observed for residues located in helices B and C, and near the active site of the enzyme, suggesting long-range allosteric effects of the myristoyl group.

Figure 2.

Mapping the changes upon myristoylation of PKA-C. A) Chemical shift perturbations (Δδ) versus residues upon myristoylation and detergent (MEGA-8) binding. B) Mapping of Δδ for myristoylation changes on a cartoon representation of PKA-C crystal structure.

Role of the myristoyl group in membrane association of PKA-C

Previous reports indicated that in addition to membrane interactions mediated by the myristoyl group, a cluster of basic residues at the N-terminus and large lobe of PKA-C can also facilitate membrane binding12, 14. To establish the role of the myristoyl group in mediating the interaction with lipid membranes and determine whether the basic residues alone in PKA-C may facilitate these interactions, we first used intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence. Based on the X-ray crystal structures of myr(+)p(−)PKA-C, at least two tryptophan residues (W30 and W302) would be sensitive to structural changes at the myristoyl hydrophobic pocket of the protein kinase (Figure S3). In addition, at least six nearby aromatic residues (Phe or Tyr) could affect the tryptophan fluorescence signal in the hydrophobic pocket6. Isotropic bicelles composed of 1,2-dimystoyl-sn-glycero-3-phsphochoine (DMPC)/1,2-diheptanoyl-sn-gycero-2-phosphocholine (D7PC) (q = 0.5, cL ~3–24%) were added stepwise to myr(−)p(+)PKA-C or myr(+)p(+)PKA-C and their tryptophan fluorescence was measured. Duplicate spectra without PKA-C samples were acquired to subtract any possible changes in the background signal due to the bicelles. The addition of bicelles to myr(−)p(+)PKA-C led to a small enhancement in the intrinsic fluorescence signal measured (Figure 3A). In contrast, the addition of bicelles to myr(+)p(+)PKA-C led to a four-fold enhancement of the intrinsic fluorescence (Figure 3B, arrows), consistent with at least one tryptophan of the enzyme being exposed to a less polar environment. Although a 10–20 nm blue shift in the fluorescence signal may be expected, this was likely masked by the lack of effects for the majority of tryptophan residues for from the hydrophobic pocket in the enzyme (Figure S4). The enzyme interaction with isotropic bicelles was further verified by measuring the profile and signal intensity changes in the amide region of NMR spectra (Figure 3C). Consistent with the intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence measurements, small changes in the profile and signal intensity of the 1D 1H spectrum of myr(−)p(+)PKA-C were detected. However, these changes for the myr(+)p(+)PKA-C sample were more drastic upon addition of bicelles. Specifically, the signal intensity decreased 40–60%. This decrease is consistent with myr(+)p(+)PKA-C binding to the larger bicellar structure, causing a change in rotational correlation time. We fit the bicelle induced changes in tryptophan fluorescence intensity to a one-site binding model, and found a Kd of ~260 mM for myr(+)p(+)PKA-C and ~1200 mM for myr(−)p(+)PKA-C (Figure 3D). These data indicate that although myr(−)p(+)PKA-C may have some interaction with the membrane surface of bicelles, this interaction is strengthened by the presence of the myristoyl group in myr(+)p(+)PKA-C.

Figure 3.

Membrane interactions of myr(−)p(+)PKA-C and myr(+)p(+)PKA-C. Intrinsic fluorescence spectra as a function of bicelle addition for A) myr(−)p(+)PKA-C and B) myr(+)p(+)PKA-C. D) Binding isotherms for both enzymes obtained from intrinsic fluorescence spectra. C) 15N-edited one-dimensional 1H NMR spectra for myr(−)p(+)PKA-C and myr(+)p(+)PKA-C showing the signal reduction upon addition of 15% isotropic bicelles. Experimental conditions are detailed on the methods section.

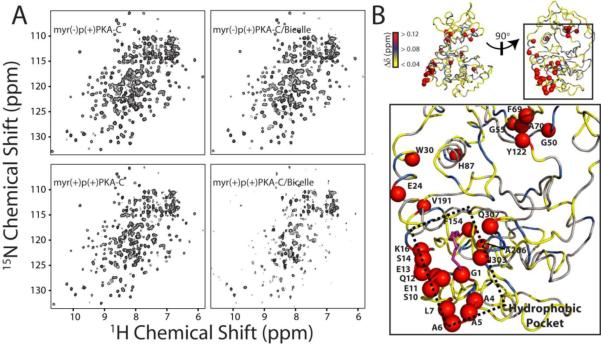

To characterize the lipid interactions at the atomic level, we analyzed amide 1H/15N combined chemical shift perturbations of both myr(−)p(+)PKA-C and myr(+)p(+)PKA-C upon addition of isotropic bicelles. Consistent with the weak binding to bicelles observed by 1D 1H NMR measurements and tryptophan fluorescence changes, the perturbations in the amide fingerprint spectra of 15N-labeled myr(−)p(+)PKA-C with bicelles were small (Figures 4A and S4). In contrast, the spectrum of 15N-labeled myr(+)p(+)PKA-C changed more substantially. In particular, the spectrum of myr(+)p(+)PKA-C was drastically attenuated in the presence of bicelles, suggesting a longer rotational correlation time (Figure 4A). Mapping of the chemical shift perturbations in 15N-labeled myr(+)p(+)PKA-C (Figure 4B) showed localized changes at the hydrophobic pocket. In addition, long-range allosteric changes in helices B, C, E, F, and J were also present. Interestingly, a cluster of residues (G50, G55, F69, A70 and Y122) near the active site of the enzyme was substantially perturbed. Small changes were detected near conserved residues involved in catalysis, such as the glycine rich Asp184-Phe185-Gly186, DFG, activation, and peptide positioning loops These changes were propagated as far away as ~30 Å from the hydrophobic pocket of myr(+)p(+)PKA-C, exemplifying an allosteric change within the enzyme upon membrane interaction.

Figure 4.

Atomic details of PKA-C interaction with bicelles. A) 2D [1H, 15N]-HSQC spectra for myr(−)p(+)PKA-C and myr(+)p(+)PKA-C in the presence of 15% isotropic bicelles. B) Mapping of Δδ for myr(+)p(+)PKA-C upon perturbation with 5% isotropic bicelles showed localized effects at the hydrophobic pocket and allosteric effects, including a group of residues at the active site of the enzyme ~30 Å from the myristoyl group.

Evidence for a conformational switch in myristoylated PKA-C

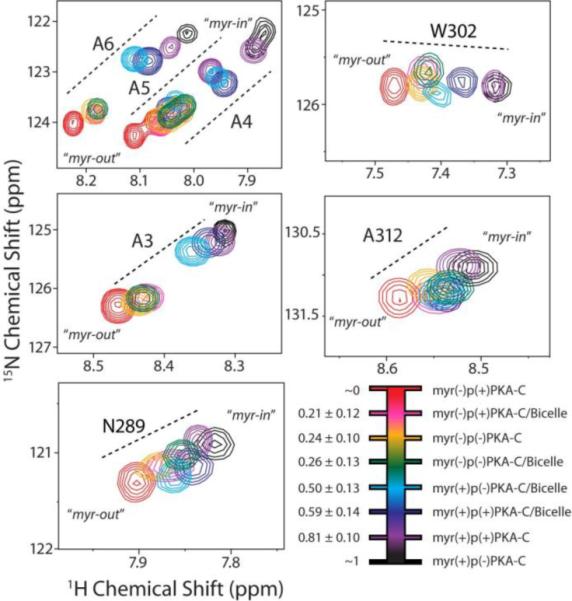

As suggested by crystallographic data, the conformation of the N-terminus of PKA-C may be sensitive to phosphorylation at S1010–13, 15, 20. Crystal structures of myr(+)p(−)PKA-C containing non-phosphorylated S10 show an ordered α-helix at the N-terminus11. On the other hand, a lack of electron density for myr(−)p(+)PKA-C22, which is phosphorylated at S10, suggests an unfolded, disordered N-terminus. In order to glean insight into how phosphorylation may affect the conformation of the N-terminus, we recorded TROSY-HSQC spectra for PKA-C samples where myristoylation was present or absent: myr(+) or myr(−), respectively; and where phosphorylation was present or absent: p(+) and p(−), respectively. When data for samples containing isotropic bicelles was included, a clear trend in chemical shift changes was evident for residues in the proximity of the hydrophobic pocket: A3–A6, N289, W302, and A312. At one end of the extreme was the downfield shifted 1H NMR resonances myr(−)p(+)PKA-C (red resonances, Figure 5). At the other extreme was the upfield shifted 1H NMR resonances of myr(+)p(−)PKA-C (black resonances, Figure 5). The position of these NMR resonances renders an apparent two-state equilibrium: downfield 1H NMR resonances suggest a disordered conformation of the N-terminus which is solvent exposed, a state which we termed myr-out; while the upfield shifts are consistent with an ordered, helical conformation of the N-terminus which is solvent protected, a state which we termed myr-in.

Figure 5.

Conformational switch of myr(+)PKA-C probed by NMR chemical shift analysis. Selected regions of the 2D [1H,15N]-HSQC spectra of specific residues undergoing fast conformational exchange between myr-in and myr-out states. The different colors indicate the various PKA-C species in the absence or presence of phosphorylation, myristoylation, and lipid bicelles. The linear trajectories of the chemical shifts observed between two extremes, corresponding to a myr-in state (black resonances) and a myr-out state (red resonances), indicates that phosphorylation and interaction with bicelles shifts the conformational equilibrium at the N-terminus. Experimental conditions are detailed on the methods section.

A number of samples had chemical shift positions which lie in between the two extremes identified, indicative of fast exchange between these two predominant conformational states. Strikingly, the membrane-free myristoylated samples (Figure 5, black and purple resonances) were shifted toward the myr-out conformational state in the presence of isotropic bicelles (Figure 5, dark blue and light blue resonances). In addition, all phosphorylated samples (Figure 5, red, pink, dark blue, and purple resonances) were shifted toward the myr-out state relative to the non-phosphorylated samples (Figure 5, yellow, green, light blue, and black resonances). This suggests that myr(+)PKA-C undergoes a conformational equilibrium at its N-terminus, where the amphipathic N-terminal helix can interact with the charged lipid headgroup and a shift to a more unfolded conformation can occur by either phosphorylation at Ser10 or myristoyl interaction with the membrane surface (Figure S5).

Positioning of the myristoyl group within the lipid bilayer

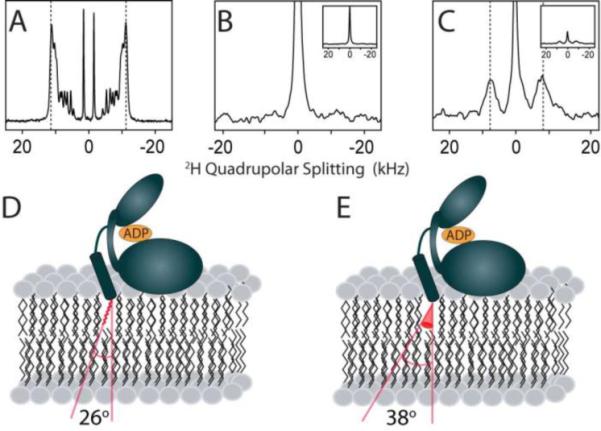

To verify the extrusion of the myristoyl group of myr(+)p(+)PKA-C out of the hydrophobic pocket and into the lipid bilayer, we reconstituted myr(+)p(+)PKA-C into oriented lipid bicelles composed of DMPC/D7PC (q = 3.2, cL = 10%). 2H-myr(+)p(+)PKA-C, which had 2H-labeling only at the myristoyl group, was obtained by incorporating 2H-labeled myristic acid into Myr-CoA. Using 2H DMPC as a reference for the quadrupolar splitting of the acyl chain in the bicelle (and therefore the order and orientation), we first measured the quadrupolar splittings of the lipid bicelles alone (Figure 6A). A superposition of 2H quadrupole splittings from each of the motionally averaged sites is observed12, 23, where the outside edges of the spectrum likely correspond to C-2 methylenes (the least motionally averaged sites) and the centermost splitting corresponds to the terminal methyl group (the most motionally averaged site). We found a maximal splitting of ~22.4 kHz for the most restricted methylene carbons in DMPC. On the other hand, 2H-myr(+)p(+)PKA-C free in solution showed no quadrupolar splitting, as expected for a molecule which has no orientation and tumbles isotropically in solution. Upon addition of aligned bicelles, 2H-myr(+)p(+)PKA-C produced a maximal quadrupolar splitting of ~15.8 kHz. This indicates that the myristoyl group has a decreased order parameter relative to the DMPC acyl chain. To describe the topology of the myristoyl group in the bicelle, the data were fit to a model which assumed the myristoyl group is static (Eqs. 4) or diffuses in a cone (Eq. 5). Using the static model, we found that the myristoyl group must be inserted into the bicelle core and is kinked at an angle of 26° with respect to the bilayer normal (Table 2, Figure 6D). Using a model which assumed diffusion in a cone, we again found that the myristoyl group must be inserted into the bicelle core and the acyl chain wobbles in a cone with an amplitude 38° with respect to the bilayer normal (Table 2, Figure 6E). These results are in agreement with previous data on a myristoylated peptide corresponding to the first 14 residues of PKA-C, which showed an angle of ~30°12. Importantly, if the acyl group of myr(+)p(+)PKA-C were resting on the surface of the bilayer (βnm=90°) the quadrupolar coupling would be ≤ 11 kHz (i.e., ≤ ½Δbicelle), assuming no additional uniaxial motion on the surface. However, the observed splitting for the myristoyl group is ~15.8 kHz. Although the observed data does not provide the exact location and dynamics of the myristoyl group from either model used, the measurements indicate unequivocally that the myristoyl group must insert into the lipid bilayer.

Figure 6.

Probing myr(+)p(+)PKA-C insertion in aligned bicelles using 2H solid-state NMR. A) 2H spectrum of 2H54-DMPC in aligned bicelles in the absence of myr(+)p(+)PKA-C. 2H spectrum of myr(+)p(+)PKA-C labeled with 2H27-myristic acid in the B)absence and C) presence of aligned bicelles. Insertion models of the myristoyl group within the lipid bicelle using D) static and E) dynamic models.

Table 2.

Model fitting results from 2H NMR spectroscopy.

| Sample | Quadrupolar splitting (kHz) | βij* (degrees) | βo** (degrees) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bicelle (2H54-DMPC) | 22.3 | - | - |

| 2H-myr(+)p(+)PKA-C + Bicelle | 15.8 | 26 | 38 |

Static Angle

Angle for diffusion in a cone

DISCUSSION

Previous studies indicated that N-myristoylation does not change the phosphorylation kinetics for soluble substrates10, and eluded that this modification changed the membrane localization properties of the enzyme12, 15. A myristoylation/phosphorylation switch for PKA-C was also hypothesized based on a study which was limited to small peptides corresponding to the N-terminus of the enzyme 13or crystal structures which are absent of any membrane environment14. The connection for the structural details and localization properties for the full-length protein with the post-translational modifications of myristoylation/phosphorylation are absent due to difficulty in obtaining N-myristoylated protein which is also phosphorylated. The in vitro myristoylation method described here allowed a facile approach to selectively myristoylate a particular phosphoisoform of the enzyme while retaining its functional properties. In this manner, we were able to test how the presence or absence of myristoylation effects interactions with the membrane surface of bicelles, particularly in the context of phosphorylation at S10.

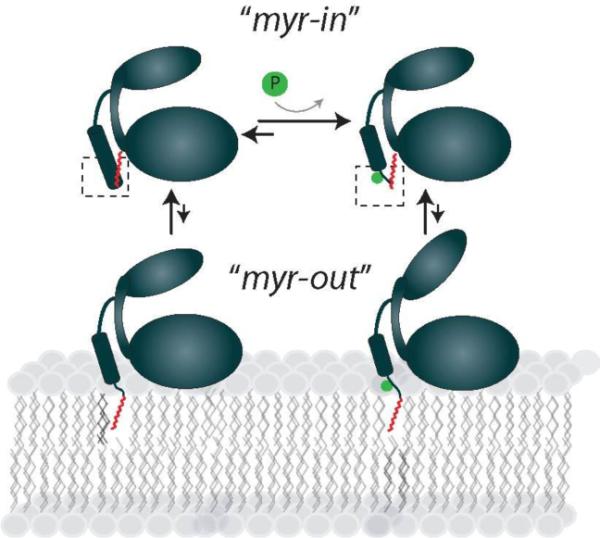

Based on our NMR chemical shift data, myr(+)PKA-C likely undergoes conformational interconversion between two major states: a myr-in state, where the myristoyl group is tucked into the hydrophobic pocket of the enzyme, and a myr-out state, where the myristoyl group is extruded from the hydrophobic pocket (Figure 7). The conformation of these major states are best characterized by crystallographic data: the myr-in state is best represented by the two additional turns of the N-terminal α-helix of myr(+)p(−)PKA-C, and the myr out state is best represented by the lack of electron density for the first ~12 residues at the N-terminus of myr(−)p(+)PKA-C. The structural features of these two conformational states agree well with the change in thermostability and the ΔCp between myr(+)p(+)PKA-C and myr(−)p(+)PKA-C that we measured in the current study. However, NMR chemical shift identify two additional states (Figure S5) that reflect the concomitant folding and unfolding of the N-terminal helix, which allows the extrusion of the myristoyl group and its insertion into the membrane core. These states lay along the same path of the two major states and indicate that folding and unfolding of the N-terminal helix is an integral part of the mechanism of the myristoyl switch. Therefore, we propose that myr(+)PKA-C has a highly populated myr-in state in the absence of membranes, and a population shift to the myr-out state is induced by the presence of a membrane surface (Figure 7) or phosphorylation at S10. The chemical shift changes of myr(+)p(+)PKA-C and myr(+)p(−)PKA-C illustrate this point. Residues in the hydrophobic pocket report on a myr-in state of ~81% for myr(+)p(+)PKA-C, which shifts to ~59% in the presence of bicelles. Whereas, phosphorylation appears to shift the myr-in state of myr(+)p(−)PKA-C from 100% to ~81% (Figure 6). X-ray crystallography11, 21 and NMR24–26 data indicate that membrane free myr(−)p(+)PKA-C has a highly mobile, unstructured N-terminus. Therefore, the myr-out state likely contains an unwound N-terminus, which likely decreases the stability of the enzyme. These dynamics of the myr-out conformational state may facilitate lipid binding by exposing both the basic patch and myristoyl anchor at the N-terminus.

Figure 7.

Proposed model of a myristoyl/phosphorylation conformational switch in PKA-C. PKA-C undergoes conformational interconversion between an N-terminal tucked myr-in state and an N-terminal extruded myr-out state. Phosphorylation and the presence of membranes cause a shift to a larger population of myr-out state which may facilitate the interaction with membranes.

The extrusion of the myristoyl group in the myr-out state and its insertion into the hydrocarbon region of the lipid bilayer are supported by 2H NMR measurements. Membrane free 2H-myr(+)PKA-C showed a completely isotropic peak for the d27-myristoyl group. A dramatic restriction of the myristoyl group dynamics was observed in the presence of anisotropic bicelles, consistent with the myristoyl group inserted into the bicelle core. The data also indicated that the myristoyl group likely assumes some degree of tilt inside the bilayer core. Although we showed evidence that myr(−)PKA-C interacts weakly with the membrane surface of bicelles, the interaction is stronger for myr(+)PKA-C. This underscores the important role of the myristoyl group to localize PKA-C to the membrane and facilitates its interactions with proteins at the interface between the membrane and aqueous environment.

The ability of myr(+)PKA-C to undergo a population shift to a myr-out state is reminiscent of the Ca2+-activated switch proposed for recoverin27 and other myristoyl-mediated membrane interactions proposed for Ras28, guanylate-cyclase29, 30, HIV-1 Nef, HIV-1 MA, and ARF123, 31–37. However, our data indicate that the role of N-myristoylation of PKA-C differs significantly from that identified for other protein kinases, such as Abl and c-Src8, 9. For these signaling enzymes, myristoylation does not necessarily coincide with their interactions with cellular membranes; rather it plays a role in the regulatory mechanism. Our studies show that the myristoyl group of myr(+)PKA-C undergoes a switch-like mechanism which plays a role in localization, specifically, trafficking the protein kinase to membrane surfaces. Therefore, protein kinase myristoylation represents a general control of the function, but the mechanism may be context specific, fine-tuning phosphorylation levels in different cellular compartments. Nonetheless, the N-myristoyl/phosphoserine switch might be necessary but not sufficient for effective membrane targeting of the kinase. In fact, the apparent Kd for lipid binding is rather weak compare to similar systems such as MARCKS38. However, PKA-C is exquisitely sensitive to ligand binding24–26 and unique changes in the dynamics of the enzyme are widespread depending on the ligand bound form of PKA-C. Therefore, it is possible that nucleotides, substrates, or inhibitors may provide another avenue to induce a myristoyl switch in PKA-C, similar to the mechanism hypothesized for ARF134, 35. AKAPs and the RII subunit may further amplify this signaling, and contribute to PKA-C membrane binding and localization.

A previously unidentified aspect from the NMR analysis is the identification of allosteric changes which are distal to the myristoylation pocket. These residues were perturbed upon integration of myristoyl group into the enzyme, or when the myristoyl group became extruded from the hydrophobic pocket upon interaction with lipid membranes. These residues represent remote sites that are in allosteric communication with the hydrophobic pocket, and may be pivotal in understanding how allostery occurs in this complex enzyme. PIt is possible that myristoylation constitutes an internal control which modulates function, and these allosteric effects observed for remote residues may reveal new elements to control PKA-C function, as in the case of Bcr-Abl kinase39.

In sum, our results provide evidence that the membrane binding motif of myr(+)PKA-C steers the enzyme to the membrane surface, a mechanism which may be controlled by a phosphoserine switch and is independent from AKAPs or RII subunit. Direct lipid association of myr(+)PKA-C may work in concert with these proteins to insure optimal response to signaling cascades at the lipid interface.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Synthesis of Myristoylcoenzyme A

Coenzyme A (CoA, free acid) was from Avanti Polar Lipids. MyristoylcoenzymeA thioester (Myr-CoA) was synthesized as previously described with minor modifications to the protocol18. Myristic acid (12 mg., 0.052 mmol, MP Biomedicals) and 1,1'-carbonyldiimidazole (8.4 mg, 0.052 mmol, Aldrich) were dissolved in 2 mL dry CH2Cl2 and 2 mL dry tetrahydrofuran (THF). The reaction was stirred for 30 min. and the solvents were removed in vacuo. The residue was dissolved in 2 mL dry THF, and the solution was added to CoA (20 mg, 0.026 mmol) dissolved in 2 mL 0.5 M aqueous NaHCO3. The reaction was stirred for 2 h. The formation of Myr-CoA was monitored by reverse-phase high performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC) on a C18 column with detection at 280 nm. Myr-CoA has a Tr = 42.9 min using a gradient of 0 – 60 % acetonitrile/0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) (Buffer B) over 60 min. THF was removed in vacuo and Myr-CoA was precipitated by dropwise addition of 20% perchloric acid until CO2 evolution ceased. The precipitate was centrifuged, and the pellet was washed three times with acetone. The acetone was removed and the pellet was dissolved in ddH2O. The solute was divided equally between four eppendorf tubes and lyophilized. Myr-CoA was stored dessicated at −20 °C. Identity was confirmed by on electrospray ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (calc: 977.3 a.m.u., found: 977.3 a.m.u.).

In vitro myristoylation of PKA-C by NMT

Recombinant PKA-C and NMT were expressed and purified as previously described40. For the myristoylation reaction, myr(−)p(+)PKA-C or myr(−)p(−)PKA-C was dialyzed extensively against buffer A (20 mM KH2PO4, pH 7.4, 90 mM KCl, 1 mM NaN3, 1 mM MgCl2 and 10 mM sucrose) at 4 °C and concentrated to 150 μM using an centrifugal concentrator (Millipore, 10 kDa cut-off). The protein kinase was then diluted to 30 μM in buffer A containing 10 mM adenosine diphosphate (ADP) and 3 mM 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio]-2-hydroxy-1-propanesulfonate (CHAPSO), followed by addition of NMT (final concentration of 1.2 μM). The reaction was initiated by addition of 500 μM Myr-CoA from a 12.5 mM aqueous stock at a pH 7.4. The reaction mixture was incubated at 24 °C for ~6 hours under gentle agitation. After the reaction, the mixture was diluted 5 times with buffer (20mM KH2PO4, pH 7.4, 25 mM KCl, 5% (v/v) glycerol, 1 mM DTT, pH 7.4) and dialyzed once against the same solution composition at pH 6.5. Separation from residual NMT was achieved by cation exchange on a MonoS column (GE Life Sciences) using a linear gradient from buffer C (20 mM KH2PO4 (pH 6.5), 5 mM DTT, 5% glycerol) into the same buffer containing 1 M KCl (0–8% over 5 minutes, 8–18% over 66 minutes). The enzyme product was dialyzed against buffer C with 180 mM KCl, 1 mM NaN3, 10 mM MgCl2, 10 mM DTT, and 10 mM ADP. The molecular weight of myr(+)p(+)PKA-C was confirmed by ESI mass spectrometry, carried out using ESI-TOF-MS. The sample was prepared by desalting on a reversed-phase C18 analytical column (Vydac), using a linear gradient of water/0.1% TFA into acetonitrile/0.1% TFA (0–20% over 20 minutes, 21–44% over 5 minutes, 45–49% over 10 minutes). For myr(+)p(+)PKA-C, a calculated mass of 40,897 a.m.u. was expected, and 40,896 a.m.u. was found.

Intrinsic Fluorescence Measurements

Fluorescence spectra were recorded on a Varian Cary Eclipse fluorescence spectrophotometer. The excitation wavelength was set to 280 nm and emission was recorded from 300 to 400 nm. The slit width was set to 10 nm (5 nm) for the excitation (emission). The scan rate was 120 nm/min with a 1 nm data interval and 0.5 s of averaging time. The protein concentration was 0.33 μM in 20 mM KH2PO4 (pH 6.5), 180 mM KCl, 100 nM EGTA, and 5% v/v glycerol. A stock solution of isotropic bicelles (q = 0.5, 40% w/v DMPC/D7PC) was prepared in the same buffer. All the bicelle samples were prepared separately and the fluorescence spectra were recorded 5 minutes after addition. All experiments were performed in triplicate. Fluorescence spectra were corrected for the blank. The blue shift observed when the bicelles were added was most dominant at 315 nm. The increase in florescence was fit to a one-site binding model using Origin 7.0 (Microcal).

Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) and differential scanning calorimetry (DSC)

For ITC measurements, the enzyme buffer was exchanged into ITC buffer containing 50 mM MOPS (pH 7.0), 5 mM MgCl2, and 1 mM DTT. The enzyme was concentrated by filtration to ~23 μM at pH 6.5. The injectant consisted of 670 μM ADP in ITC buffer. Samples were degassed for ~10 min prior to titration of the ligand. Isothermal titration calorimetry was carried out on a Microcal MCS-ITC at 27 °C with a stirring rate of 400 r.p.m. The titrations consisted of an initial 2 μL injection of ADP, followed by twenty 10 μL injections. An initial delay of 60 s and 300 s waiting time between each consecutive injection was used. The binding curves were fit to a one-site binding model using Origin 7.0 (Microcal). The curves were corrected for the heat of dilution, which was determined by separate blank titrations of ADP into ITC buffer.

For DSC measurements, samples were prepared in DSC buffer (20 mM KH2PO4, pH 6.5, 150 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 10 mM DTT and 1 mM NaN3) to a concentration of ~25 μM. Both samples were degassed with stirring for 5 minutes in a ThermoVac (Microcal). DSC measurements were carried out on a Microcal VP-DSC instrument over a temperature range of 20 to 60 °C, a scan rate of 90 °C/hour, and a prescan delay of 15 minutes. Two scans were carried out with each sample, which verified the irreversibility of the transition. Data analysis was carried out in Origin (Microcal). Reference scans were obtained using reference buffer and were subtracted during data analysis.

Thermostability by circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy

Samples consisted of 10 μM protein kinase in 5 mM KH2PO4 (pH 6.5), 45 mM KCl, 1mM NaN3, and 300 μM MgADP. Far-UV (190–260 nm) CD spectra were obtained on a Jasco J-715 spectropolarimeter. The samples were measured in a 1 mm dichroically neutral quartz cuvette with a 1 mm bandwidth, 2 s time constant, of 20 nm/min scan speed, and an average of 2 scans with background signal correction. After acquisition of the far-UV profile, the samples were heated to 65 °C at 3 °C/min (10 s equilibration) and the signal at 222 nm was measured as a reporter of thermal melting. Data were fit to a two-state sigmoidal unfolding model with Origin 8.0 (Microcal) and the midpoint of the curve was taken as the melting temperature (Tm).

NMR Spectroscopy

NMR experiments were carried out on a Varian Inova spectrometer operating at 599.71 MHz and equipped with an HCN probe. Enzyme samples were prepared in 20mM KH2PO4, 180 mM KCl, 1 mM NaN3,10 mM DTT, 10 mM ADP, 10 mM MgCl2, 5% v/v glycerol, and 5% v/v D2O (pH 6.5). The concentrations of the samples were ~0.1–0.3 mM. To confirm the N-terminal linkage between the myristic acid and the protein, we used myristic acid with 13C incorporated specifically at the carbonyl position to synthesize Myr-CoA for in vitro reactions. PKA-C (uniformly labeled with 15N) was then myristoylated enzymatically by NMT as described. To detect the linkage, we used the carbonyl carbon label selective [1H/15N]-CCLS-HSQC experiment19, which detects 15N labeled amide groups covalently linked to 13C labeled carbonyl groups. For membrane binding studies, we prepared 1,2-dimyristoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine/1,2-diheptanoyl-sn-glyero-2-phosphocholine (DMPC/D7PC) isotropic bicelles (q = 0.5, cL = 40% for stock solutions). The NMR data were processed and visualized using NMRPipe41 and SPARKY42. Backbone resonance assignments were performed by 1) comparison of the myr(+)p(+)PKA-C fingerprint with those of myr(−)p(+)PKA-C43, 2) following the NMR chemical shifts during titrations of myr(−)p(+)PKA-C with the myristoyl analog, MEGA-8, and 3) additional resolution provided by 15N selectively labeled samples (Glu, Lys, and Ala residues) of myr(+)p(+)PKA-C (Figure S6). Chemical shift perturbations from the NMR titrations were measured using combined chemical shifts according to the equation:

| Eq. 1 |

where Δδ is the combined chemical shift, and ΔδH and ΔδN are the differences of 1H and 15N chemical shifts, respectively, between the two different isoforms, or the first and last points of titrations. Populations of the myr-in state (pmyr-in) was quantified using:

| Eq. 2 |

where Ωx, Ωmyr-out, and Ωmyr-in are the chemical shift of sample X, myr(−)p(+)PKA-C, and myr(+)p(−)PKA-C, respectively. The mean of pmyr-in was determined from seven resonances distributed within 12 Å from the myristoyl group in pdb 1CMK.

2H Solid-state NMR Spectroscopy

Deuterated myristic acid was (2H-myr) used to prepare 2H-myr(+)p(+)PKA-C for the measurement of quadrupolar splitting in the presence or absence of aligned bicelles (DMPC/D7PC, q = 3.2) by solid-state NMR. NMR samples were prepared in 20 mM KH2PO4 (pH 6.5), 180 mM KCl, 1 mM NaN3, 10 mM DTT, 20 mM ADP, 20 mM MgCl2, and 5% (v/v) glycerol, in deuterium depleted water. Stock bicelle solutions (cL=30%) were titrated into an enzyme solution on ice to obtain a final concentration of 600 μM myr(+)p(+)PKA-C and a cL of 10%. Quadrupolar splittings of DMPC were performed on a bicelle solution containing 2% (v/v) 2H54-DMPC of the total DMPC present. All 2H experiments were recorded at a 2H resonance frequency of 107.4 MHz. Samples were initially at 5 °C and were gradually warmed to 27 °C over 10 minutes and equilibrated for 30 minutes. The bicelle alignment was checked by 31P NMR spectroscopy. A quadrupolar echo sequence, (π/2)-τ1-(π/2)-τ2, was used to measure the 2H-quadrupolar splitting. The spectra of myr(+)p(+)PKA-C in the presence and absence of bicelles were acquired with 40,000 scans each.

The bicellar composition used in this study has a negative order parameter such that the bilayer normal is oriented perpendicular to the magnetic field. The observed quadrupolar splitting (Δ) for a methylene deuteron in an alkyl chain is given by the following relationship44:

| Eq. 3 |

where kHz and is the orientational order parameter which links the coordinate axes i and j to one another. This requires obtaining the average orientation of the bicelle normal, n', with respect to the magnetic field in the laboratory frame (βn'l), the angle between the average bilayer normal and the instantaneous, n, or local bilayer normal (βn'n), the orientation of a molecular axis, m, with respect to n, (βnm), and the local angel between the molecular axis and the principal axis, p, of the quadrupolar tensor along the CD bond (βmp). The expression in Eq. 3 can be simplified by dividing the splitting of the myristoylated sample by that of the bicelle:

| Eq. 4 |

The equation above can be fit to extract a static angle or by assuming diffusion-in-a-cone model shown in Eq. 5:

| Eq. 5 |

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge Susan Taylor for many helpful discussions. This work was supported by the NIH (GM072701 and HL080081 to G.V, and T32DE007288 to L.R.M.) and the AHA (09PRE2080017 to E.M). NMR data were collected at the U. of Minnesota NMR Facility (NSF BIR-961477).

ABBREVIATIONS

- CDI

1,1'-carbonydiimidazole

- CoA

Coenzyme A

- Myr

myristoylated

- RP-HPLC

reversed phase high pressure liquid chromatography

- THF

tetrahydrofuran

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Walsh DA, Perkins JP, Krebs EG. An adenosine 3',5'-monophosphate-dependant protein kinase from rabbit skeletal muscle. J. Biol. Chem. 1968;243:3763–3765. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shabb JB. Physiological substrates of cAMP-dependent protein kinase. Chem. Rev. 2001;101:2381–2411. doi: 10.1021/cr000236l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Knighton DR, Zheng JH, Ten Eyck LF, Ashford VA, Xuong NH, Taylor SS, Sowadski JM. Crystal structure of the catalytic subunit of cyclic adenosine monophosphate-dependent protein kinase. Science. 1991;253:407–414. doi: 10.1126/science.1862342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carnegie GK, Means CK, Scott JD. A-kinase anchoring proteins: from protein complexes to physiology and disease. IUBMB Life. 2009;61:394–406. doi: 10.1002/iub.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walsh DA, Ashby CD, Gonzalez C, Calkins D, Fischer EH. Krebs EG: Purification and characterization of a protein inhibitor of adenosine 3',5'-monophosphate-dependent protein kinases. J. Biol. Chem. 1971;246:1977–1985. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnson DA, Akamine P, Radzio-Andzelm E, Madhusudan M, Taylor SS. Dynamics of cAMP-dependent protein kinase. Chem. Rev. 2001;101:2243–2270. doi: 10.1021/cr000226k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boutin JA. Myristoylation. Cell. Signal. 1997;9:15–35. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(96)00100-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hantschel O, Nagar B, Guettler S, Kretzschmar J, Dorey K, Kuriyan J, Superti-Furga G. A myristoyl/phosphotyrosine switch regulates c-Abl. Cell. 2003;112:845–857. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00191-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patwardhan P, Resh MD. Myristoylation and membrane binding regulate c-Src stability and kinase activity. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2010;30:4094–4107. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00246-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yonemoto W, McGlone ML, Taylor SS. N-myristylation of the catalytic subunit of cAMP-dependent protein kinase conveys structural stability. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:2348–2352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zheng J, Knighton DR, Nguyen HX, Taylor SS, Sowadski JM, Ten Eyck LF. Crystal structures of the myristylated catalytic subunit of cAMP-dependent protein kinase reveal open and closed conformations. Protein Sci. 1993;2:1559–1573. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560021003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Struppe J, Komives EA, Taylor SS, Vold RR. 2H NMR studies of a myristoylated peptide in neutral and acidic phospholipid bicelles. Biochemistry. 1998;37:15523–27. doi: 10.1021/bi981326b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tholey A, Pipkorn R, Bossemeyer D, Kinzel V, Reed J. Influence of myristoylation, phosphorylation, and deamidation on the structural behavior of the N-terminus of the catalytic subunit of cAMP-dependent protein kinase. Biochemistry. 2001;40:225–231. doi: 10.1021/bi0021277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Breitenlechner CB, Engh RA, Huber R, Kinzel V, Bossemeyer D, Gassel M. The Typically Disordered N-Terminus of PKA Can Fold as a Helix and Project the Myristoylation Site into Solution. Biochemistry. 2004;43:7743–7749. doi: 10.1021/bi0362525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gangal M, Clifford T, Deich J, Chen X, Taylor SS, Johnson DA. Mobilization of the A-kinase N-myristate through an Isoform-specific Intermolecular Switch. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:12394–12399. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.22.12394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Duronio R, Jackson-Machelski E, Heuckeroth RO, Olins PO, Devine CS, Yonemoto W, Slice LW, Taylor SS, Gordon JI. Protein N-myristoylation in Escherichia coli: Reconstitution of a eukaryotic protein modification in bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:1506–10. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.4.1506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yonemoto WM, McGlone ML, Slice LW, Taylor SS. Prokaryotic expression of catalytic subunit of adenosine cyclic monophosphate-dependent protein kinase. Methods Enzymol. 1991;200:581–596. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)00173-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heal WP, Wickramasinghe SR, Bowyer PW, Holder AA, Smith DF, Leatherbarrow RJ, Tate EW. Site-specific N-terminal labelling of proteins in vitro and in vivo using N-myristoyl transferase and bioorthogonal ligation chemistry. Chem. Commun. (Camb) 2008;(4):480–482. doi: 10.1039/b716115h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tonelli M, Masterson LR, Hallenga K, Veglia G, Markley JL. Carbonyl carbon label selective (CCLS) (1)H- (15)N HSQC experiment for improved detection of backbone (13)C- (15)N cross peaks in larger proteins. J. Biomol. NMR. 2007;39(3):177–85. doi: 10.1007/s10858-007-9185-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sowadski JM, Ellis CA, Madhusudan Detergent binding to unmyristylated protein kinase A. Structure implications for the role of myristate. Journal of Bioenergetics and Biomembranes. 1996;28:7–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zheng J, Knighton DR, ten Eyck LF, Karlsson R, Xuong N, Taylor SS, Sowadski JM. Crystal structure of the catalytic subunit of cAMP-dependent protein kinase complexed with MgATP and peptide inhibitor. Biochemistry. 1993;32:2154–2161. doi: 10.1021/bi00060a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Knighton DR, Zheng J, Eyck LFT, Xuong NH, Taylor SS, Sowadski JM. Structure of a Peptide Inhibitor Bound to the Catalytic Subunit of Cyclic Adenosine Monophosphate-Dependent Protein Kinase. Science. 1991;253:414–420. doi: 10.1126/science.1862343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Valentine KG, Mesleh MF, Opella SJ, Ikura M, Ames JB. Structure, topology, and dynamics of myristoylated recoverin bound to phospholipid bilayers. Biochemistry. 2003;42:6333–6340. doi: 10.1021/bi0206816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Masterson LR, Mascioni A, Traaseth NJ, Taylor SS, Veglia G. Allosteric cooperativity in protein kinase A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 15. 2008;105(2):506–11. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709214104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Masterson LR, Cheng C, Yu T, Tonelli M, Kornev AP, Taylor SS, Veglia G. Dynamics connect substrate recognition to catalysis in protein kinase A. Nature Chemical Biology. 2010;6:821–828. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Masterson LR, Shi L, Metcalfe E, Gao J, Taylor SS, Veglia G. Dynamically committed, uncommitted, and quenched states encoded in protein kinase A revealed by NMR spectroscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2011;108(17):6969–74. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1102701108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ames JB, Ishima R, Tanaka T, Gordon JI, Stryer L, Ikura M. Molecular mechanics of calcium-myristoyl switches. Nature. 1997;389:198–202. doi: 10.1038/38310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vogel A, Reuther G, Roark MB, Tan KT, Waldmann H, Feller SE, Huster D. Backbone conformational flexibility of the lipid modified membrane anchor of the human N-Ras protein investigated by solid-state NMR and molecular dynamics simulation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2010;1798:275–285. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2009.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Theisgen S, Scheidt HA, Magalhaes A, Bonagamba TJ, Huster D. A solid-state NMR study of the structure and dynamics of the myristoylated N-terminus of the guanylate cyclase-activating protein-2. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2010;1798:266–274. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2009.06.028. 10.1016/j.bbamem.2009.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Theisgen S, Thomas L, Schroder T, Lange C, Kovermann M, Balbach J, Huster D. The presence of membranes or micelles induces structural changes of the myristoylated guanylate-cyclase activating protein-2. Eur. Biophys. J. 2011;40:565–576. doi: 10.1007/s00249-011-0680-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jeromin A, Muralidhar D, Parameswaran MN, Roder J, Fairwell T, Scarlata S, Dowal L, Mustafi SM, Chary KV, Sharma Y. N-terminal myristoylation regulates calcium-induced conformational changes in neuronal calcium sensor-1. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:27158–67. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312172200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Provitera P, El-Maghrabi R, Scarlata S. The effect of HIV-1 Gag myristoylation on membrane binding. Biophys Chem. 2006;119:23–32. doi: 10.1016/j.bpc.2005.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Losonczi JA, Tian F, Prestegard JH. Nuclear magnetic resonance studies of the N-terminal fragment of adenosine diphosphate ribosylation factor 1 in micelles and bicelles: influence of N-myristoylation. Biochemistry. 2000;39:3804–3816. doi: 10.1021/bi9923050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu Y, Kahn RA, Prestegard JH. Structure and membrane interaction of myristoylated ARF1. Structure. 2009;17:79–87. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu Y, Kahn RA, Prestegard JH. Dynamic structure of membrane-anchored Arf*GTP. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2010;17:876–881. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saad JS, Miller J, Tai J, Kim A, Ghanam RH, Summers MF. Structural basis for targeting HIV-1 Gag proteins to the plasma membrane for virus assembly. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2006;103:11364–11369. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602818103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Saad JS, Ablan SD, Ghanam RH, Kim A, Andrews K, Nagashima K, Soheilian F, Freed EO, Summers MF. Structure of the myristylated human immunodeficiency virus type 2 matrix protein and the role of phosphatidylinositol-(4,5)-bisphosphate in membrane targeting. J. Mol. Biol. 2008;382:434–447. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.07.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vergeres G, Ramsden JJ. Binding of MARCKS (myristoylated alanine-rich C kinase substrate)-related protein (MRP) to vesicular phospholipid membranes. Biochem. J. 1998;330:5–11. doi: 10.1042/bj3300005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang J, Adrian FJ, Jahnke W, Cowan-Jacob SW, Li AG, Iacob RE, Sim T, Powers J, Dierks C, Sun F, Guo GR, Ding Q, Okram B, Choi Y, Wojciechowski A, Deng X, Liu G, Fendrich G, Strauss A, Vajpai N, Grzesiek S, Tuntland T, Liu Y, Bursulaya B, Azam M, Manley PW, Engen JR, Daley GQ, Warmuth M, Gray NS. Targeting Bcr-Abl by combining allosteric with ATP-binding-site inhibitors. Nature. 2010;463:501–506. doi: 10.1038/nature08675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cook LL, Stine KE, Reiter LW. Tin distribution in adult rat tissue after exposure to trimethyltin and triethyltin. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 1984;76:344–348. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(84)90015-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Delaglio F, Grzesiek S, Vuister GW, Zhu G, Pfeifer J, Bax A. NMRPipe: A Multidimensional Spectral Processing System Based on UNIX Pipes. J. Biomol. NMR. 1995;6:277–293. doi: 10.1007/BF00197809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Goddard TD, Kneller DG. SPARKY 3. 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Masterson LR, Shi L, Tonelli M, Mascioni A, Mueller MM, Veglia G. Backbone NMR resonance assignment of the catalytic subunit of cAMP-dependent protein kinase A in complex with AMP-PNP. Biomol. NMR Assign. 2009;3:115–117. doi: 10.1007/s12104-009-9154-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Seelig J. Deuterium magnetic resonance: theory and application to lipid membranes. Q Rev Biophys. 1977;10:353–418. doi: 10.1017/s0033583500002948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.