Abstract

Although many believe that low rates of perceived mental health need and service use among racial/ethnic minorities are due, in part, to somatization, data supporting this notion are lacking. This study examined two hypotheses: (1) increased physical symptoms are associated with lower perceived need for mental health services and actual service use; and (2) physical symptoms are most strongly associated with perceived mental health need and service use among first-generation individuals. Data come from the National Latino and Asian-American Study, a nationally-representative household survey in the United States conducted from 2002 to 2003. Participants reported on the presence of fourteen physical symptoms within the past year. Perceived mental health need was present for individuals who endorsed having an emotional or substance use problem or thinking they needed treatment for such a problem within the past year. After adjusting for sociodemographic and clinical covariates, the number of physical symptoms was positively associated with perceived mental health need and service, an effect that differed by generation. Among first-generation individuals, physical symptoms were associated with increased perceived need and service use. Physical symptoms were not significantly associated with perceived need or service use among third-generation Latinos, but were associated with service use among third-generation Asian-Americans. Physical symptoms do not appear to interfere with mental health problem recognition or service use. In contrast, individuals, especially of the first-generation, with more physical symptoms were more likely to perceive need for and utilize mental health services. Our findings do not support the notion that physical symptoms account for low rates of perceived mental health need and service use among Latino and Asian-Americans.

Keywords: USA, National Latino and Asian American study, perceived need, ethnicity, race, service use, mental health, somatization

Introduction

Help-seeking for mental disorders can be conceptualized as a series of events that begins with an individual experiencing symptoms, then attributing the symptoms to a mental condition (or not), evaluating options for care, and subsequently, seeking (or not seeking) treatment. Research has consistently found perceived mental health need (hereafter termed “perceived need”) to be one of the most important predictors mental health service use, (Bauer et al., 2010; Mojtabai et al., 2002; Nadeem et al., 2009) with evidence that it is central in the decision-making process to determine if professional care is required (Edlund et al., 2006; Leaf et al., 1988; Mojtabai et al., 2002; Pescosolido et al., 1998).

Perceptions of need for care are socially constructed (Mechanic, 2002) and arise in part through social comparison of symptoms (Mojtabai, 2008). Symptom attribution may vary by people’s sociocultural context and normative judgments of what is pathological (Alegria et al., 2002; Cauce et al., 2002; Kirmayer et al., 1994; Meadows et al., 2002; Sussman et al., 1987). For example, in qualitative research, low-income African-Americans thought their mental health problems were normal responses to difficult life situations (Hines-Martin et al., 2003). Similarly, fewer minority than white women with depression perceived a need for treatment, suggesting that ethnic differences in perceived need could offer a partial explanation for service use disparities (Nadeem et al., 2009). Additionally, limited English proficiency has been associated with lower perceived need (Bauer et al., 2010). Other studies report no differences in perceived need by race/ethnicity (Edlund et al., 2006; Mojtabai et al., 2002) raising questions about the role of perceived need in differences in care. Consequently, understanding correlates of perceived need represents a critical challenge for mental health services researchers.

Although reasons for racial/ethnic differences in perceived need are poorly understood, many believe that low perceived need results when somatic symptoms “mask” recognition of psychopathology (Skapinakis & Araya, 2011). According to DSM-IV-TR, conversion symptoms (psychogenic symptoms affecting voluntary motor and sensory systems) are culturally-shaped and are more common in less developed regions (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). The literature includes several explanations why somatization may be more common in non-Western cultures. Historically, the somatic expression of distress was believed to reflect incomplete psychological development and poor insight, attributes ascribed to racial/ethnic minorities (USDHHS, 2001). More recent views suggest that societies where health is viewed holistically may have fewer distinctions between mind and body. Alternately, manifestation of psychological symptoms may carry greater stigma in more collectivistic societies (Keyes & Ryff, 2003). Thus, it has been hypothesized that racial/ethnic minorities may be more likely to deny psychological symptoms and somatize distress and furthermore, that because of this tendency, they have lower recognition of psychiatric problems and are more likely to seek medical rather than mental health services (Nadeem et al., 2009; Skapinakis & Araya, 2011; USDHHS, 2001). Although evidence suggests that help-seeking patterns are associated with characteristics of the healthcare system rather than physical symptoms (Simon et al., 1999), the somatization hypothesis may have gained traction among clinicians because it locates one source for well-observed disparities in care among patients themselves, thus diverting attention from provider or institutional factors.

The literature on cultural variations in somatic symptoms is mixed. Conventional wisdom suggests that inasmuch as somatization occurs among less Westernized groups, those who have had the least exposure to Western norms and values would somatize more. In contrast, there is evidence that later immigrant generations and more acculturated individuals have worse mental and physical health, through increased awareness of and exposure to discrimination, increased family cultural conflict and family burden, and detrimental effects of assimilation on health behaviors (Acevedo-Garcia et al., 2010; Acevedo-Garcia et al., 2005; Alegria et al., 2007; Lara et al., 2005). Because effects begin in early childhood among later generations, and accumulate over the life-course, the burden of these social stressors may be heightened among later generations relative to immigrants arriving as adults (Alegria et al., 2007; Viruell-Fuentes, 2007). Therefore, to the extent that physical symptoms are positively associated with overall psychological distress, they may be more prominent among later generations. It remains unknown how generational status may be associated with symptom attribution and perceptions of mental health need.

Our previous finding that physical symptoms are equally prevalent among Latinos and whites, yet less common among Asian-Americans in the United States is not consistent with the view that racial/ethnic minorities experience more physical symptoms (Bauer et al., In Press). However, data is lacking on whether physical symptoms are associated with perceived need among Latino and Asian-Americans and whether such associations, if present, are particularly salient among the first generation. To address this gap in knowledge, this study examined two hypotheses: (1) increased physical symptoms are associated with lower perceived mental health need and service use; and (2) physical symptoms are more strongly associated with perceived need and service use among earlier compared to later generations.

Methods

Sample and Participants

We analyzed data from the National Latino and Asian-American Study (NLAAS), a nationally-representative household survey of adults in one of the 50 US states or the District of Columbia. The sample consisted of 2554 Latino (Mexican, Puerto Rican, Cuban, and “other”) and 2095 Asian-Americans (Chinese, Vietnamese, Filipino, and “other”) who spoke English, Spanish, Mandarin, Cantonese, Vietnamese, or Tagalog and completed written informed consent in their preferred language. Details of the design, sampling procedures, and human subjects’ protections have been reported previously (Alegria et al., 2004; Heeringa et al., 2004; Pennell et al., 2004). Data were collected by trained bilingual interviewers who conducted computer-assisted interviews in-person or by telephone in 2002–2003, with a weighted response rate of 75.5% for Latinos and 65.6% for Asian-Americans. The institutional review boards at Cambridge Health Alliance, University of Washington, and University of Michigan approved all recruitment, consent and interviewing procedures.

Measures

Generation

Respondents born outside the fifty US states or in Puerto Rico were “first-generation”, whereas US-born participants were “second-generation” if one or both parents were foreign-born; or “third-generation” if both parents were US-born (Rumbaut, 2004).

Language Proficiency

Because English proficiency is associated with both perceived need and service use among Latino and Asian-Americans (Bauer et al., 2010), participants were asked, “How well do you speak English?” with responses coded dichotomously as “poor/fair” or “good/excellent” (Abe-Kim et al., 2006; Bauer et al., 2010).

Physical Symptoms

Fourteen symptoms were selected based upon prior studies of physical symptoms in the community and among racial/ethnic minority populations (Escobar et al., 2010; Escobar et al., 1987), indicating that these symptoms are common, disabling, and associated with psychopathology: dizziness; fainting spells; trouble swallowing or lump in throat; nausea, gas, indigestion; stomach or belly pain; diarrhea or constipation; chest pain; heart pounding or racing; shortness of breath or trouble breathing; pain in arms, legs, joints; back pain; pains or problems related to menstruation; pain or problems during sex; and numbness or tingling. A symptom was counted if participants considered it “frequent or severe” and had discussed it with a health professional within the past 12 months. Because the requirement for discussion with a professional may reflect help-seeking behavior rather than severity, sensitivity analyses were conducted using lifetime symptoms which did not necessitate discussion with a professional.

Covariates

Participants reported age, gender, education, employment status, income, marital status, and chronic medical conditions (arthritis, gastrointestinal ulcer, hypertension, myocardial infarction, stroke, diabetes, cancer, asthma, COPD, tuberculosis, or HIV/AIDS). Participants also completed the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (Andrews & Slade, 2001; Kessler et al., 2002) and the World Health Organization disability assessment scale (Rehm et al., 1999).

Perceived Mental Health Need

Participants were classified as perceiving a mental health need if within the past year they thought they had “a nervous, emotional, drug or alcohol problem” or thought they “should talk to a medical doctor or other health professional about these problems (emotions, nerves, mental health, or your use of alcohol or drugs)”.

Service Use

Service use for mental disorders within the past year was counted for participants who reported use of services from a general medical (general practitioner, other medical doctor, nurse, occupational therapist, or other health professional) or specialty mental health (psychiatrist, psychologist or any other mental health professional) provider for mental health purposes.

Statistical Analysis

Logistic regression models stratified by race/ethnicity were specified with perceived need and service use as separate dependent variables. Independent variables were the number of physical symptoms, generation, English proficiency, and sociodemographic and clinical covariates. A second model added interaction terms to specify the association of physical symptoms for each generation. For analyses of service use, a third model included perceived need as an independent variable.

Results

Perceived Mental Health Need

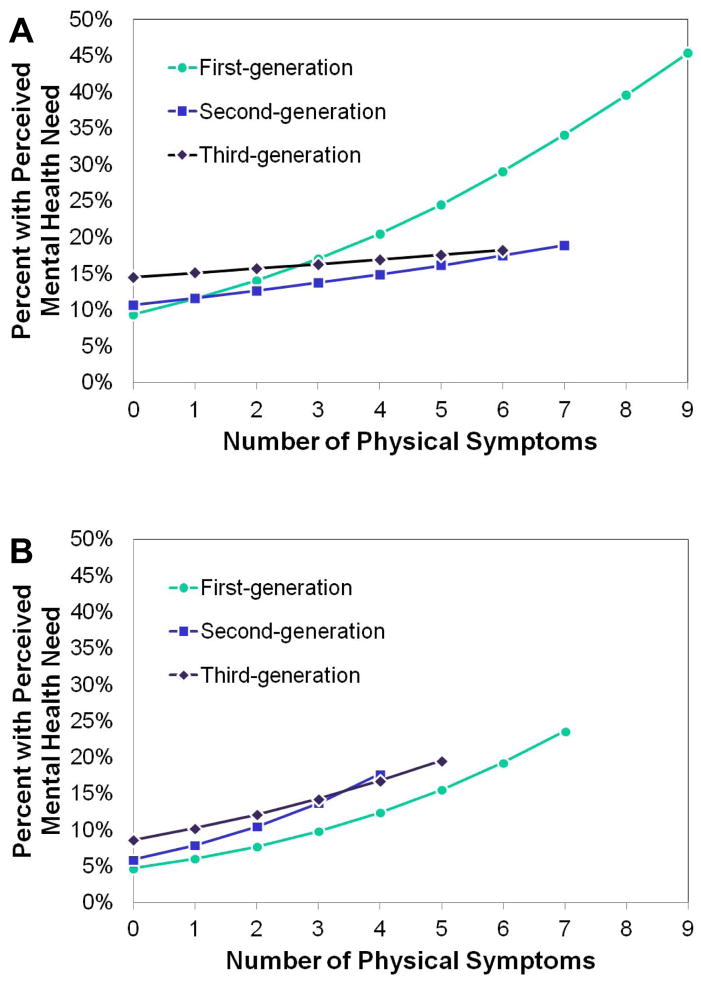

In adjusted models, physical symptoms were associated with increased perceived need (Latino: OR=1.21; Asian-American: OR=1.37, ps≤0.001; Table 1). Entered simultaneously, neither English proficiency nor generation were significantly associated with perceived need among Latinos; however, significantly more Asian-Americans with good versus limited English proficiency reported perceived need (OR=1.72, p≤0.05). Significant interactions between physical symptoms and generation emerged (Figure). Among the third-generation, physical symptoms were not significantly associated with perceived need. In contrast, among the earlier generations, physical symptoms were positively associated with perceived need, a pattern that was significant among first-generation Latinos (OR=1.32, p<0.001) and both first- and second-generation Asian-Americans (OR=1.38 and OR=1.46, respectively, ps<0.001). After introducing the interaction term, a main effect of generation emerged, with earlier generations having lower perceived need (OR range 0.45 to 0.65), a pattern significant only among first-generation Latinos (OR=0.55, p<0.05). Sensitivity analyses were conducted using lifetime symptoms without necessitating discussion with a provider and among the subsample with a usual source of healthcare. Results were unchanged suggesting that the results are not explained by healthcare access.

Table 1.

Association of physical symptoms and generation with past-year perceived mental health need a

| Latino Odds Ratio (95% confidence interval) | Asian-American Odds Ratio (95% confidence interval) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Model A | Model B | Model A | Model B | |

| Good English Proficiency (reference: limited) | 1.25 (0.84–1.84) | 1.26 (0.85–1.85) | 1.72* (1.08–2.73) | 1.72* (1.07–2.74) |

| Generation (reference: Third-generation) | ||||

| Second-generation | 0.72 (0.45–1.11) | 0.65 (0.41–1.05) | 0.74 (0.36–1.51) | 0.61 (0.26–1.14) |

| First-generation | 0.72 (0.41–1.27) | 0.55* (0.32–0.95) | 0.52 (0.22–1.22) | 0.45 (0.18–1.12) |

| Number of Physical Symptoms (Range 0–14) | 1.21** (1.10–1.32) | 1.37** (1.19–1.57) | ||

| Physical symptoms in third-generation | 1.06 (0.94–1.19) | 1.26 (0.79–2.02) | ||

| Physical symptoms in second-generation | 1.12 (0.94–1.33) | 1.46** (1.18–1.81) | ||

| Physical symptoms in first-generation | 1.32** (1.16–1.50) | 1.38** (1.19–1.60) | ||

p<0.05;

p<0.001

Adjusted for age, gender, education, employment, income, marital status, psychological distress, chronic medical conditions, and disability

Figure.

Estimated perceived need by generation for (A) Latinos and (B) Asian-Americans (adjusted for sociodemographic and clinical covariates).

Service Use

Analogous to the results for perceived need, physical symptoms were positively associated with service use (Latino: OR=1.12, p<0.01; Asian-American: OR=1.34, p<0.001, Table 2) and symptoms interacted with generation. Physical symptoms were not associated with service use among third-generation Latinos, but were associated with greater service use among third-generation Asian-Americans (OR=1.62, p≤0.01) and among first-generation Latinos (OR=1.15, p≤0.01) and Asian-Americans (OR=1.30, p≤0.01).

Table 2.

Association of physical symptoms and generation with past-year service use a

| Latino Odds Ratio (95% confidence interval) | Asian-American Odds Ratio (95% confidence interval) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Model A | Model B | Model C | Model A | Model B | Model C | |

| Good English Proficiency (reference: limited) | 1.64 (0.92–2.91) | 1.65 (0.94–2.91) | 1.63 (0.89–2.99) | 1.26 (0.59–2.69) | 1.26 (0.59–2.71) | 1.08 (0.43–2.74) |

| Generation (reference: Third-generation) | ||||||

| Second-generation | 0.59* (0.40–.088) | 0.50* (0.28–0.90) | 0.54 (0.27–1.09) | 0.38* (0.16–0.89) | 0.67 (0.24–1.83) | 0.83 (0.30–2.29) |

| First-generation | 0.68 (0.37–1.27) | 0.60 (0.27–1.29) | 0.69 (0.27–1.74) | 0.39** (0.21–0.73) | 0.57 (0.25–1.28) | 0.74 (0.39–1.40) |

| Number of Physical Symptoms | 1.12** (1.04–1.21) | 1.34*** (1.15–1.56) | ||||

| Physical symptoms in third-generation | 1.04 (0.90–1.20) | 1.03 (0.85–1.25) | 1.62** (1.15–2.27) | 1.64* (1.05–2.56) | ||

| Physical symptoms in second-generation | 1.16 (0.97–1.39) | 1.14 (0.96–1.34) | 1.15 (0.81–1.64) | 0.93 (0.63–1.39) | ||

| Physical symptoms in first-generation | 1.15** (1.04–1.27) | 1.08 (0.97–1.19) | 1.30** (1.11–1.53) | 1.20 (0.99–1.46) | ||

| Perceived Need | 6.83*** (4.09–11.38) | 17.74*** (10.56–29.80) | ||||

p<0.05;

p<0.01;

p<0.001

Adjusted for age, gender, education, employment, income, marital status, psychological distress, chronic medical conditions, and disability

Perceived need was strongly associated with service use (Latino: OR=6.83; Asian-American: OR=17.74, ps≤0.001). Adjusting for perceived need, physical symptoms were no longer associated with service use among Latinos. Among Asian-Americans, addition of perceived need to the model had little effect on the associations between physical symptoms and service use (third-generation: OR=1.64, p≤0.05, first-generation: OR=1.20, p=0.06). Sensitivity analyses with lifetime physical symptoms yielded no substantive changes in these patterns.

Discussion

After accounting for psychological distress, chronic medical conditions, and disability, individuals with more physical symptoms are more likely than counterparts to perceive a need for and to use mental health services. These patterns were evident among both Latino and Asian-Americans, and most pronounced among the first-generation. Consistent with recent research on symptom attribution in the general population in Latin America (Skapinakis & Araya, 2011), our findings call into question the conventional wisdom that physical symptoms interfere with an individual’s recognition of a mental health problem and thus, can account for low rates of perceived need and service use among racial/ethnic minorities. Our findings are also inconsistent with the hypothesis that less Westernized individuals with physical symptoms deny psychological symptoms. Rather than somatization reflecting a non-Western process, some have suggested that psychologization may be a more culture-specific process in Western societies (Kirmayer et al., 1994; Simon et al., 1999).

Our findings challenge the paradigm that locates under-detection of mental disorders among people with physical symptoms within the individual, a paradigm that is consistent with Western biases in causal attribution that overestimate the role of the individual while minimizing the importance of contextual factors (Kirmayer et al., 1994). Although we did not have data addressing providers’ interpretation of an individual’s symptoms, we speculate that such interpretation, which may incorporate person-centered biases in attribution, may influence service use for mental disorders. Previous research has demonstrated that psychiatric conditions are less likely to be identified among patients with comorbid psychological and physical symptoms, that physicians are less likely to discuss mental health concerns with patients who have greater medical complexity, and that physicians, not patients, initiate biomedical evaluations and interventions for physical symptoms (Ring et al., 2005; Rost et al., 2000). Under-recognition of mental disorders is particularly problematic among racial/ethnic minorities (Borowsky et al., 2000), with evidence that providers talk less about these conditions with minority patients (Tai-Seale et al., 2007). Future research on the under-detection of mental disorders among individuals with physical symptoms should address contextual factors by considering potential contributions from clinical providers and healthcare systems.

Consistent with prior research, we find that perceived need for mental health care is strongly associated with help-seeking among community-dwelling Latino and Asian-Americans (Bauer et al., 2010; Mojtabai et al., 2002; Nadeem et al., 2009). Among Asian-Americans but not Latinos, physical symptoms remained associated with service use after accounting for the strong association of service use with perceived need. Although our analyses did not specifically test whether patterns were different between Latinos and Asian-Americans, we observe that the association between physical symptoms and perceived need appeared somewhat stronger among Asian-Americans for all generations. We speculate that this pattern may relate to the site of care because Asian-Americans in the community access specialty mental health services at lower rates than Latinos (Abe-Kim et al., 2006; Alegria et al., 2006). Therefore, it is plausible that Asian-Americans who accessed services received more services in general medical settings, and could account for a stronger relationship between physical symptoms and service use among Asian-Americans. An important direction for future research would be to determine whether groups differ significantly in patterns of service use and if so, to unravel the implications.

Past research has found that the major determinants of help-seeking among individuals with perceived mental health need were sociodemographic and attitudinal, as opposed to clinical (Sareen et al., 2005). Our results differed in indicating that physical symptoms remained associated with service use after adjusting for perceived need among certain Asian-Americans. Several clinical covariates in our models also demonstrated significant associations with service use after accounting for perceived need, including chronic medical conditions among Asian-Americans, and psychological distress among both groups (data available on request). Therefore, our findings are consistent with the notion that clinical variables are associated with mental health service use directly in addition to associations mediated by perceived mental health need.

These findings should be considered within the context of several limitations. Because the sample excluded hospitalized and institutionalized individuals who may have had the most severe psychiatric and medical conditions, our results may underestimate associations between clinical variables, perceived need and service use. Perceived need, service use, and physical symptoms were based on self-report and therefore could have been subject to recall bias. To minimize this potential bias, symptoms were counted only if within the past year they were frequent and severe such that they had been discussed with a health professional, thereby restricting analyses to symptoms that were recent and considered to be serious. Requiring that symptoms were discussed excludes those who did not use any services. However, sensitivity analyses using lifetime symptoms without requiring discussion yielded similar results. Because most participants in this community-based sample reported five or fewer physical symptoms, some estimates for perceived need are based on small numbers and future research should evaluate patterns among highly symptomatic individuals. Although we focus on associations with generation and English proficiency, we did not examine other measures that may be relevant to help-seeking for mental disorders among ethnic minority and immigrant communities. For example, social networks, which undergo change during the longitudinal acculturative process, are likely important. Finally, we report on patterns among Latino and Asian-Americans but recognize that the use of broad racial/ethnic categories may obscure distinct patterns among subethnic subgroups.

This is the first nationally-representative study to examine associations between physical symptoms, perceived need, and mental health service use in the United States. The findings contradict the belief that one reason racial/ethnic minorities have low perceived need and low service use is because they are more likely to express distress as physical symptoms. The presence of physical symptoms instead is associated with increased mental health problem recognition and treatment, particularly among immigrants, a population that is highly likely to have unmet mental health needs. Developing greater understanding of the links between physical symptoms, perceived need, and service use may prove fruitful in efforts directed at engaging such individuals in treatment. Moreover, these findings should stimulate researchers to consider the importance of perceived mental health need, which is likely closely associated with mental health literacy, as an avenue to understand and address service use disparities among racial/ethnic minority groups.

Research highlights.

It has been hypothesized that racial/ethnic minorities somatize distress, thus masking mental health problem recognition

The somatization hypothesis was tested in a nationally-representative sample of Latino and Asian Americans in the USA

Physical symptoms were associated with higher perceived mental health need and treatment, especially among immigrants

Physical symptoms do not explain low perceived mental health need and service use among Latino and Asian Americans

Physical symptoms may not account for under-detection of mental disorders and contextual factors should be considered

Acknowledgments

The NLAAS data used in this analysis were provided by the Center for Multicultural Mental Health Research at the Cambridge Health Alliance. The authors gratefully acknowledge financial support from the Dupont-Warren and Livingston Fellowships of the Department of Psychiatry at Harvard Medical School, training grants T32 MH20021 (PI: Katon) from the National Institute of Mental Health, and NIH Research Grant # U01 MH62209 funded by the National Institute of Mental Health as well as the Substance Abuse & Mental Health Services Administration/Center for Mental Health Services and the Office of Behavioral and Social Science Research. This publication was also made possible by Grant # P60 MD002261 from the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD) and Grant #P50 MH073469 from the National Institute of Mental Health. A preliminary version of this report was presented as a poster at the Twenty-first NIMH Conference on Mental Health Services Research in Washington DC, July 2011.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Amy M. Bauer, Email: abauer1@u.washington.edu, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, University of Washington, Seattle, WA.

Chih-Nan Chen, Email: cchen@charesearch.org, Department of Economics, National Taipei University, Taiwan.

Margarita Alegría, Email: malegria@charesearch.org, Center for Multicultural Mental Health Research and Cambridge Health Alliance, Somerville, MA

References

- Abe-Kim J, Takeuchi D, Hong S, Zane N, Sue S, Spencer M, et al. Use of Mental Health-Related Services among Immigrant and Us-Born Asian Americans: Results from the National Latino and Asian American Study. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;97:91–98. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.098541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acevedo-Garcia D, Bates LM, Osypuk TL, McArdle N. The Effect of Immigrant Generation and Duration on Self-Rated Health among Us Adults 2003–2007. Social Science & Medicine. 2010;71:1161–1172. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acevedo-Garcia D, Pan J, Jun HJ, Osypuk TL, Emmons KM. The Effect of Immigrant Generation on Smoking. Social Science & Medicine. 2005;61:1223–1242. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alegria M, Canino G, Rios R, Vera M, Calderon J, Rusch D, et al. Inequalities in Use of Specialty Mental Health Services among Latinos, African Americans, and Non-Latino Whites. Psychiatric Services. 2002;53:1547–1555. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.53.12.1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alegria M, Mulvaney-Day N, Woo M, Torres M, Gao S, Oddo V. Correlates of Past-Year Mental Health Service Use among Latinos: Results from the National Latino and Asian American Study. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;97:76–83. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.087197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alegria M, Shrout PE, Woo M, Guarnaccia P, Sribney W, Vila D, et al. Understanding Differences in Past Year Psychiatric Disorders for Latinos Living in the Us. Social Science & Medicine. 2007;65:214–230. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.03.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alegria M, Takeuchi D, Canino G, Duan N, Shrout P, Meng XL, et al. Considering Context, Place and Culture: The National Latino and Asian American Study. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2004;13:208–220. doi: 10.1002/mpr.178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews G, Slade T. Interpreting Scores on the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10) Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health. 2001;25:494–497. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-842x.2001.tb00310.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer AM, Chen CN, Alegria M. English Language Proficiency and Mental Health Service Use among Latino and Asian Americans with Mental Disorders. Medical Care. 2010;48:1097–1104. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181f80749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer AM, Chen CN, Alegria M. Prevalence of Physical Symptoms and Their Association with Race/Ethnicity and Acculturation in the United States. General Hospital Psychiatry. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2012.02.007. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borowsky SJ, Rubenstein LV, Meredith LS, Camp P, Jackson-Triche M, Wells KB. Who Is at Risk of Nondetection of Mental Health Problems in Primary Care? Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2000;15:381–388. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.12088.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cauce AM, Domenech-Rodriguez M, Paradise M, Cochran BN, Shea JM, Srebnik D, et al. Cultural and Contextual Influences in Mental Health Help Seeking: A Focus on Ethnic Minority Youth. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70:44–55. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edlund MJ, Unutzer J, Curran GM. Perceived Need for Alcohol, Drug, and Mental Health Treatment. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2006;41:480–487. doi: 10.1007/s00127-006-0047-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escobar JI, Cook B, Chen CN, Gara MA, Alegria M, Interian A, et al. Whether Medically Unexplained or Not, Three or More Concurrent Somatic Symptoms Predict Psychopathology and Service Use in Community Populations. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2010;69:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escobar JI, Golding JM, Hough RL, Karno M, Burnam MA, Wells KB. Somatization in the Community: Relationship to Disability and Use of Services. American Journal of Public Health. 1987;77:837–840. doi: 10.2105/ajph.77.7.837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heeringa SG, Wagner J, Torres M, Duan N, Adams T, Berglund P. Sample Designs and Sampling Methods for the Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiology Studies (CPES) International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2004;13:221–240. doi: 10.1002/mpr.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hines-Martin V, Malone M, Kim S, Brown-Piper A. Barriers to Mental Health Care Access in an African American Population. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 2003;24:237–256. doi: 10.1080/01612840305281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Andrews G, Colpe LJ, Hiripi E, Mroczek DK, Normand SLT, et al. Short Screening Scales to Monitor Population Prevalences and Trends in Non-Specific Psychological Distress. Psychological Medicine. 2002;32:959–976. doi: 10.1017/s0033291702006074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes CL, Ryff CD. Somatization and Mental Health: A Comparative Study of the Idiom of Distress Hypothesis. Social Science & Medicine. 2003;57:1833–1845. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(03)00017-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirmayer LJ, Young A, Robbins JM. Symptom Attribution in Cultural Perspective. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 1994;39:584–595. doi: 10.1177/070674379403901002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lara M, Gamboa C, Kahramanian MI, Morales LS, Bautista DE. Acculturation and Latino Health in the United States: A Review of the Literature and Its Sociopolitical Context. Annual Review of Public Health. 2005;26:367–397. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leaf PJ, Bruce ML, Tischler GL, Freeman DH, Jr, Weissman MM, Myers JK. Factors Affecting the Utilization of Specialty and General Medical Mental Health Services. Medical Care. 1988;26:9–26. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198801000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meadows G, Burgess P, Bobevski I, Fossey E, Harvey C, Liaw ST. Perceived Need for Mental Health Care: Influences of Diagnosis, Demography and Disability. Psychological Medicine. 2002;32:299–309. doi: 10.1017/s0033291701004913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mechanic D. Removing Barriers to Care among Persons with Psychiatric Symptoms. Health Affairs. 2002;21:137–147. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.21.3.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mojtabai R. Social Comparison of Distress and Mental Health Help-Seeking in the Us General Population. Social Science & Medicine. 2008;67:1944–1950. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.09.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mojtabai R, Olfson M, Mechanic D. Perceived Need and Help-Seeking in Adults with Mood, Anxiety, or Substance Use Disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2002;59:77–84. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadeem E, Lange JM, Miranda J. Perceived Need for Care among Low-Income Immigrant and U.S.-Born Black and Latina Women with Depression. Journal of Women’s Health. 2009;18:369–375. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2008.0898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennell BE, Bowers A, Carr D, Chardoul S, Cheung GQ, Dinkelmann K, et al. The Development and Implementation of the National Comorbidity Survey Replication, the National Survey of American Life, and the National Latino and Asian American Survey. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2004;13:241–269. doi: 10.1002/mpr.180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pescosolido BA, Gardner CB, Lubell KM. How People Get into Mental Health Services: Stories of Choice, Coercion and “Muddling through” from “First-Timers”. Social Science & Medicine. 1998;46:275–286. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(97)00160-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehm J, Üstün TB, Saxena S, Nelson CB, Chatterji S, Ivis F, et al. On the Development and Psychometric Testing of the Who Screening Instrument to Assess Disablement in the General Population. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 1999;8:110–122. [Google Scholar]

- Ring A, Dowrick CF, Humphris GM, Davies J, Salmon P. The Somatising Effect of Clinical Consultation: What Patients and Doctors Say and Do Not Say When Patients Present Medically Unexplained Physical Symptoms. Social Science & Medicine. 2005;61:1505–1515. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rost K, Nutting P, Smith J, Coyne JC, Cooper-Patrick L, Rubenstein L. The Role of Competing Demands in the Treatment Provided Primary Care Patients with Major Depression. Archives of Family Medicine. 2000;9:150–154. doi: 10.1001/archfami.9.2.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rumbaut RG. Ages, Life Stages, and Generational Cohorts: Decomposing the Immigrant First and Second Generations in the United States. International Migration Review. 2004;38:1160–1205. [Google Scholar]

- Sareen J, Cox BJ, Afifi TO, Clara I, Yu BN. Perceived Need for Mental Health Treatment in a Nationally Representative Canadian Sample. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;50:643–651. doi: 10.1177/070674370505001011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon GE, VonKorff M, Piccinelli M, Fullerton C, Ormel J. An International Study of the Relation between Somatic Symptoms and Depression. New England Journal of Medicine. 1999;341:1329–1335. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199910283411801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skapinakis P, Araya R. Common Somatic Symptoms, Causal Attributions of Somatic Symptoms and Psychiatric Morbidity in a Cross-Sectional Community Study in Santiago, Chile. BMC Research Notes. 2011;4:155. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-4-155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sussman LK, Robins LN, Earls F. Treatment-Seeking for Depression by Black and White Americans. Social Science & Medicine. 1987;24:187–196. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(87)90046-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tai-Seale M, McGuire T, Colenda C, Rosen D, Cook MA. Two-Minute Mental Health Care for Elderly Patients: Inside Primary Care Visits. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2007;55:1903–1911. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- USDHHS. Mental Health: Culture, Race, and Ethnicity: A Supplement to Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Mental Health Services; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viruell-Fuentes EA. Beyond Acculturation: Immigration, Discrimination, and Health Research among Mexicans in the United States. Social Science & Medicine. 2007;65:1524–1535. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]