Abstract

Barbiturate use in conjunction with alcohol can result in severe respiratory depression and overdose deaths. The mechanisms underlying the additive/synergistic actions were unresolved. Current management of ethanol-barbiturate-induced apnea is limited to ventilatory and circulatory support coupled with drug elimination. Based on recent preclinical and clinical studies of opiate-induced respiratory depression, we hypothesized that ampakine compounds may provide a treatment for other types of drug-induced respiratory depression. The actions of alcohol, pentobarbital, bicuculline, and the ampakine CX717, alone and in combination, were measured via 1) ventral root recordings from newborn rat brain stem-spinal cord preparations and 2) plethysmographic recordings from unrestrained newborn and adult rats. We found that ethanol caused a modest suppression of respiratory drive in vitro (50 mM) and in vivo (2 g/kg ip). Pentobarbital induced an ∼50% reduction in respiratory frequency in vitro (50 μM) and in vivo (28 mg/kg for pups and 56 mg/kg for adult rats ip). However, severe life-threatening apnea was induced by the combination of the agents in vitro and in vivo via activation of GABAA receptors, which was exacerbated by hypoxic (8% O2) conditions. Administration of the ampakine CX717 alleviated a significant component of the respiratory depression in vitro (50–150 μM) and in vivo (30 mg/kg ip). Bicuculline also alleviated ethanol-/pentobarbital-induced respiratory depression but caused seizure activity, whereas CX717 did not. These data demonstrated that ethanol and pentobarbital together caused severe respiratory depression, including lethal apnea, via synergistic actions that blunt chemoreceptive responses to hypoxia and hypercapnia and suppress central respiratory rhythmogenesis. The ampakine CX717 markedly reduced the severity of respiratory depression.

Keywords: apnea, glutamate, hypoxia, hypercapnia, GABA

the combination of barbiturate use in conjunction with alcohol can result in severe respiratory depression and significant incidence of overdose deaths (1, 3, 14, 22, 31, 32). Barbiturates and alcohol enhance gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA)-mediated chloride currents (36, 41), the primary source of inhibitory signaling within the CNS. In the context of respiratory control, neurons located in the proposed respiratory rhythm-generating center, the pre-Bötzinger complex (preBötC), express GABAA receptors and are potently inhibited by their activation (4, 28, 29, 35). In addition, activation of GABAA receptors results in depressed neuronal activity within other respiratory brain stem nuclei and motoneurons controlling respiratory muscles (45). Here, we designed our study to further enhance our mechanistic understanding of alcohol-barbiturate suppression of breathing by using in vitro and in vivo newborn and adult rat models to examine the combinatorial action of ethanol and pentobarbital on respiratory depression under normoxic, hypoxic, and hypercapnic conditions. We then tested the hypothesis that the ampakine CX717 can alleviate the severe respiratory depression induced by the combination of alcohol and barbiturates.

CX717 is a member of the ampakine family of compounds that positively modulate amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionate (AMPA) receptors by increasing the duration of glutamate-induced AMPA receptor-gated inward currents (2, 17). Importantly, CX717 has good metabolic stability and has been deemed safe in primate studies and early stage clinical trials for short-term use (6, 21, 26, 42). Glutamate, acting via AMPA receptors, is a key component of the excitatory drive critical for respiratory rhythmogenesis within the preBötC (15, 23) and the drive to respiratory motoneurons (9, 11, 23). This forms the basis for the hypothesis that accentuation of excitatory AMPA-mediated currents within respiratory neuronal populations induced by CX717 would act to counter the barbiturate-alcohol-induced potentiation of inhibitory GABAA receptor-mediated currents within those neurons. Precedence for this pharmacological approach was established in preclinical rodent studies demonstrating that CX717 alleviated opiate-induced depression of respiratory rhythmogenesis (27) and drive to XII motoneurons (16) acting via μ-opiate receptors. Subsequently, the rodent data translated well with a positive phase IIA clinical trial demonstrating prevention of alfentanyl-induced respiratory depression by CX717 without loss of analgesia or significant side-effects (21).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In vitro brain stem-spinal cord preparations.

All experimental procedures were approved by University of Alberta Animal Welfare Committee. Neonatal Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats aged postnatal day 0 (P0) to P2 were anaesthetized with metofane and decerebrated, and the brain stem-spinal cord was dissected according to procedures previously described (11, 37). The neuraxis was continuously perfused at 27 ± 0.5°C (5 ml/min; volume of 3 ml) with modified Kreb's solution that contained (in mM): 128 NaCl, 3.0 KCl, 1.5 CaCl2, 1.0 MgSO4, 24 NaHCO3, 0.5 NaH2PO4, and 30 d-glucose equilibrated with 95% O2-5% CO2 (pH 7.4). Recordings from the fourth ventral cervical nerve roots were amplified, rectified, low-pass filtered, and recorded using an analog-to-digital converter (Axon Instruments Digidata 1200; Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) and data acquisition software (Axon Instruments).

Plethysmographic measurements.

Measurements from unrestrained newborn and adult male SD rats were performed in whole-body plethysmographs that had inflow and outflow ports for continuous delivery of gases (room air, 8% oxygen, or 5% CO2) and removal of expired carbon dioxide. The plethysmograph volumes were 260 and 2,000 ml for neonatal (P7–P8) and adult (300–400 g) male rats with a flow rate of 2 l/min and 10 l/min, respectively. Pressure changes were recorded with a pressure transducer (model DP 103, Validyne, Northridge, CA), signal conditioner (CD-15, Validyne), and analog-to-digital board (pClamp, Axon Instruments). Our plethysmographic recording setup is effective for studying respiratory frequency (fR) and detection of apneas. However, it is not suitable for precise quantification of tidal volume (Vt) but rather changes relative to control values (i.e., pre- and post-drug delivery). The physical principle underlying whole-body plethysmography is the detection of pressure changes in the chamber resulting from the heating and humidification of inspired gas. However, Vt (ml/g) measurement may also be influenced by gas compression effects related to the airway resistance. Because of these limitations, whole-body plethysmography only provides semi-quantitative measurements of Vt and detection of changes relative to control state (before drug). Minute ventilation (V̇e; ml·min−1·g−1) equals fR × Vt, providing semi-quantitative measurements. Therefore, relative value (to control), but not absolute value for Vt and V̇e are provided. The chemoreceptive responses (5 min, after 30 s of gas exchange equilibration) to changed O2 or CO2 were made by switching from room air to hypoxia (8% O2) or hypercapnea (5% CO2) with a flow rate of 10 l/min. It took ∼30 s for gas exchange within the large chamber, as confirmed with Oxychek instrumentation (Critikon, Tampa, FL). Furthermore, a pulse oximeter (Norin 8600V, Plymouth, MN) was placed on the tail to monitor oxygen saturation levels. Rectal temperature was measured before drug and after ethanol and/or pentobarbital administration (model 8402-10 thermistor, Cole-Parmer Instrument). For newborns, the plethysmograph and air pump were contained within an infant incubator (Isolette, model C-86; Air-Shields/Dräger Medical, Hatboro, PA) to maintain the ambient temperature at the approximate nest temperature of 32°C and relative humidity at ∼50% (20, 30). The fresh air is also warmed up to 32°C before entering the plethysmographical recording chamber to avoid the “cool down” effect of rapid air flow on the pups' body temperature. The dose of ethanol (2 g/kg ip) tested is twice the blood alcohol concentration limits (0.08%) for driving in U.S., Canada, and United Kingdom. Pentobarbital (28–56 mg/kg ip) is based on previous studies of patients with acute intoxication of pentobarbital at the range of 2–72 μg/ml plasma concentration (10).

Pharmacological agents.

Bicuculline and strychnine (from Sigma Canada) were dissolved in DMSO and pentobarbital (Nembutal or Euthanyl, 240 mg/ml; Bimeda-MTC, Cambridge, ON), and/or ethanol (anhydrous ethyl alcohol) was injected intraperitonealy into the left abdomen of postnatal or adult male rats. CX717 (provided by Dr. Mark Varney, Cortex Pharmaceuticals, Irvine, CA) was dissolved in a 100% DMSO (stock solution: 200 mM) for in vitro experiments (final DMSO concentration of <0.1% volume) and dissolved in a 10% 2-hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin (HPCD; Sigma) in 0.45% saline solution (stock solution: 6 mg/ml) for all in vivo experiments (intraperitoneal final HPCD administrated was ≤500 mg/kg body wt). The vehicle (DMSO in vitro, HPCD in vivo) had no effects on baseline respiratory parameters or ethanol-pentobarbital-induced respiratory depression.

Statistical analyses.

Data are expressed as means ± SE. The respiratory parameters were measured over a period of 5 min for both in vitro and in vivo except for the chemoreceptive experiments where we analyzed the reflex response to hypoxia and hypercapnia for 1 min. Sigmaplot 11 (Systat Software) was used to conduct the statistical analyses. The significance of changes in the respiratory parameters was evaluated by a one-way ANOVA (multiple groups) with a post hoc Tukey's test or t-test (two groups). We normalized and reported control values as 1. The significance of changes in survival rate was evaluated by a proportion z-test. P < 0.05 was taken as significant difference.

RESULTS

In vitro newborn rat brain stem spinal cord preparation.

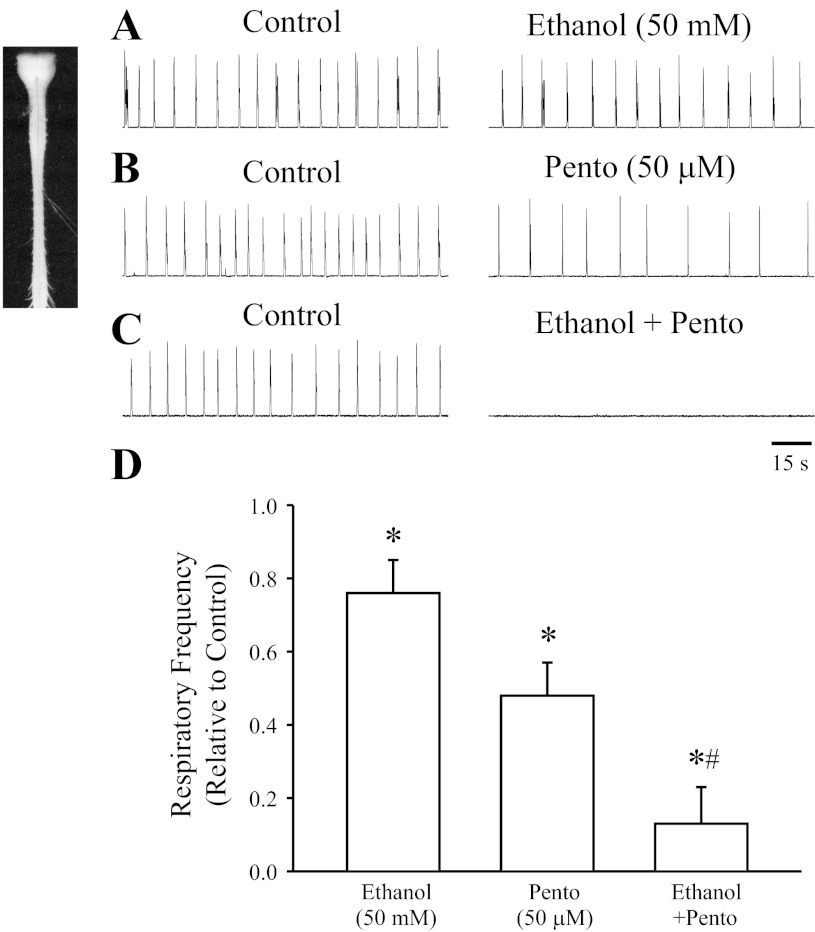

Perinatal rodent brain stem-spinal cord preparations have been well characterized and shown to generate complex, coordinated patterns of respiratory-related activity (12, 37). The use of in vitro preparations allowed for the examination of the synergistic effects of ethanol and pentobarbital on respiratory activity in isolation of indirect modulation via action at supramedullary structures. Figure 1 shows a representative example of the respiratory discharge of ventral fourth cervical nerve roots (C4) produced by brain stem-spinal cord preparations of P2 rats. Application of ethanol (50 mM) or pentobarbital (50 μM) caused a partial depression in the frequency of rhythmic respiratory discharge, with a maximum suppression occurring within 5–40 min of perfusion. Co-administration of ethanol (50 mM) and pentobarbital (50 μM) severely suppressed the respiratory frequency and completely blocked the respiratory activity within 10–40 min of perfusion in three of five of preparations. The depression of respiratory frequency persisted for 10–60 min after washout of ethanol-pentobarbital from the bathing medium. There was no significant effect on respiratory amplitude with application of ethanol or pentobarbital. Population data (Fig. 1D) show the respiratory frequency suppressed by 50 mM ethanol alone (76 ± 9% of control; n = 5), 50 μM pentobarbital alone (48 ± 9% of control; n = 5), and after co-administration (13 ± 10% of control; n = 5).

Fig. 1.

Ethanol and pentobarbital decrease respiratory frequency in neonatal rat in vitro brain stem-spinal cord preparations. A–C: rectified and integrated recordings from C4 ventral roots of P2 rat brain stem-spinal cord preparations in control conditions and after 30 min of the following drug applications to the bathing media: 50 mM ethanol, 50 μM pentobarbital, or 50 mM ethanol in combination with 50 μM pentobarbital. D: population data showing relative respiratory frequency after drug treatment (n = 5 for each group). *Significant difference from control (P < 0.05). #Significant difference from all other groups (P < 0.05).

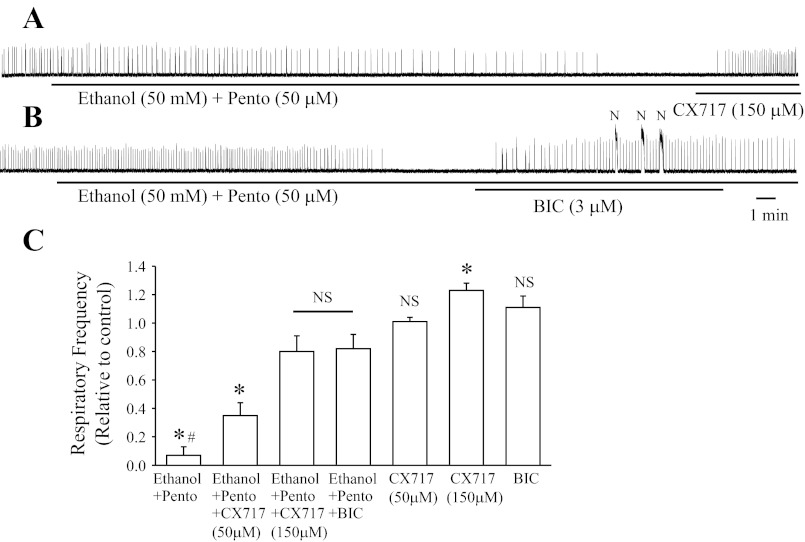

Data in Fig. 2B show that the respiratory suppression induced by ethanol-pentobarbital was significantly alleviated (82 ± 10% of control) by the GABAA receptor antagonist bicuculline (BIC; 3 μM, administered for 15 min). As shown in previous studies (28), BIC alone at these doses does not significantly alter baseline respiratory activity but often induced long-duration (>3 s), high-amplitude, non-respiratory, seizure-like motor discharge (Fig. 2B; observed in four of five preparations). Bath application of the glycine receptor antagonist strychnine (1 μM) did not change the respiratory depression by ethanol-pentobarbital combination (n = 3; data not shown). Note that chloride-mediated conductances in the respiratory rhythm-generating preBötC are inhibitory after embryonic day 19 (E19) in rats (28).

Fig. 2.

CX717 and bicuculline (BIC) alleviate ethanol plus pentobarbital-induced depression of the rhythmic respiratory activity generated by in vitro brain stem-spinal cord neonatal rat preparations. A: rectified and integrated recording from C4 ventral roots of postnatal day 1 (P1) rat brain stem after bath application of ethanol (50 mM) plus pentobarbital (50 μM). Apnea was alleviated by additional bath application of CX717 (150 μM). B: rectified and integrated recording from C4 ventral roots of P1 rat brain stem after bath application of ethanol (50 mM) plus pentobarbital (50 μM). Apnea was alleviated by additional bath application of BIC (3 μM). Note that bath application of bicuculline induced nonrespiratory (N), high-amplitude, long-duration bursts of motor activity. C: population data showing respiratory burst frequency relative to control (n = 4–5 for each group, from P0 to P2). *Significant difference compared with control (P < 0.05). #Significant difference compared with all other groups (P < 0.05). NSNo significant difference compared with control or between two compared groups (P > 0.05).

We then examined the effects of CX717 on reversing the respiratory depression caused by co-administration of ethanol and pentobarbital by applying two doses of CX717 (50 or 150 μM) to the bathing medium. After 15 min of exposure, the lower dose of 50 μM CX717 partially alleviated the alcohol-pentobarbital-induced depression of respiratory frequency (35 ± 9% of control; Fig. 2C), whereas 150 μM CX717 had a much more pronounced effect (80 ± 11% of control; Fig. 2, A and C). Note that a low dose of CX717 (50 μM; n = 5) did not cause a significant change of baseline respiratory frequency when added on its own to the media bathing brain stem-spinal cord preparations, whereas a higher dose (150 μM; n = 4) increased baseline respiratory frequency to 123 ± 5% of control. Neither dose induced nonrespiratory, seizure-like activity.

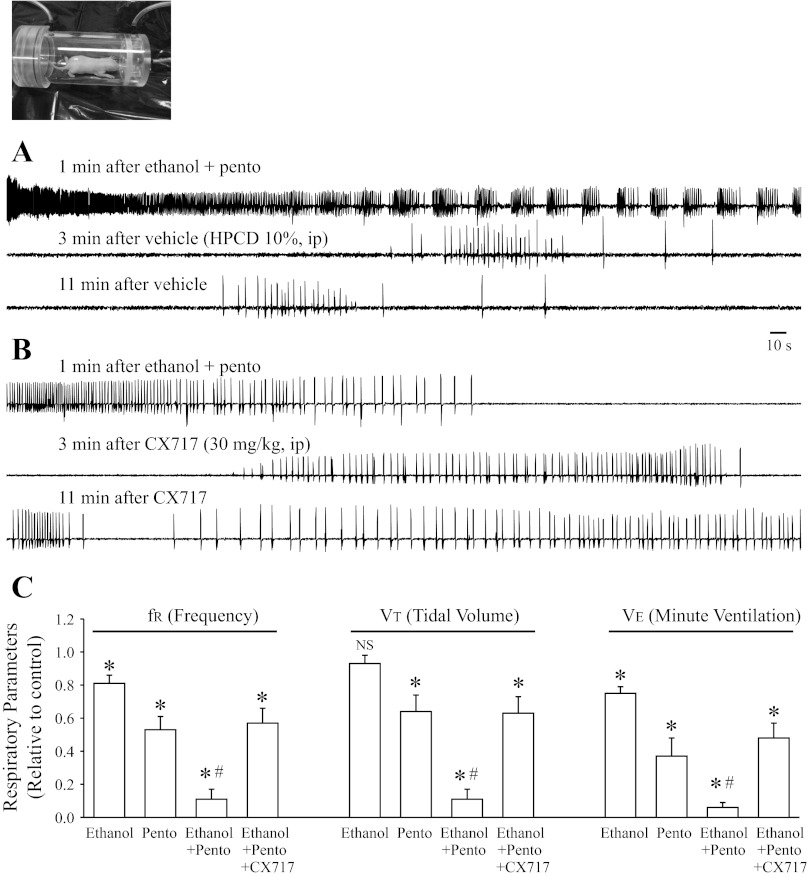

In vivo newborn rat plethysmographic recordings.

The next stage of the study was to examine the interactions of ethanol and pentobarbital in vivo. Toward correlating with the in vitro studies, we first examined newborn rats in vivo. Figure 3 shows data from whole-body plethysmographic recordings from unrestrained newborn rats (P7–8). The baseline respiratory frequency in pups was 141 ± 5 breaths/min (n = 44). Administration of ethanol (2 g/kg; n = 6) alone significantly suppressed fR (81 ± 5% of control) and V̇e (75 ± 4% of control) without significant effects on Vt (93 ± 5% of control). Pentobarbital (28 mg/kg; n = 8) alone significantly suppressed fR (53 ± 8% of control), Vt (64 ± 10% of control), and V̇e (37 ± 11%). The combined administration of ethanol (2 g/kg) and pentobarbital (28 mg/kg) caused a severe depression of fR (11 ± 6% of control), Vt (12 ± 6% of control), and V̇e (6 ± 3%). Ethanol-pentobarbital combination caused marked apneas interposed with periodic bursts of respiratory activity in 12 of 15 animals (Fig. 3A). The administration of either ethanol (2 g/kg; n = 6) or pentobarbital (28 mg/kg; n = 8) did not induce any fatal apneas (Table 1). In contrast, 10 of 15 newborn rats had lethal apnea after the combined administration of ethanol (2 g/kg) and pentobarbital (28 mg/kg). Administration of vehicle (10% HPCD) did not change the course of respiratory depression and lethal apneas (Fig. 3A), whereas with administration of CX717 (30 mg/kg ip), 12 of 15 animals survived when CX717 was administered within 5–30 min after ethanol and pentobarbital administration (Fig. 3, B and C; Table 1; Z-test, P = 0.026). Furthermore, ethanol-pentobarbital-induced decrease of respiratory activity (fR, Vt, and V̇e) was significantly alleviated after administration of CX717 (30 mg/kg; Fig. 3C; P < 0.05). Consistent with a previous study (27), administration of CX717 (30 mg/kg; n = 4) alone to unanesthetised animals did not cause any seizure-like activity, marked behavioral change, or significant change in baseline respiratory parameters.

Fig. 3.

Co-administration of ethanol and pentobarbital caused a marked suppression of respiratory activity in newborn rats in vivo. A: whole-body plethysmographic measurements from unrestrained newborn rats after administration of the combination of ethanol (2 g/kg ip) and pentobarbital (28 mg/kg ip). Administration of vehicle (10% HPCD ip; filled rectangle) did not change the course of respiratory depression and lethal apnea. B: whole-body plethysmographic measurements from an unrestrained newborn rat after administration of the combination of ethanol (2 g/kg ip) and pentobarbital (28 mg/kg ip). Administration of CX717 (30 mg/kg ip) rescued the animal from ethanol plus pentobarbital-induced lethal apnea. C: population data showing respiratory parameters (relative to control): frequency (fR), tidal volume (Vt), and minute ventilation (V̇e) with ethanol (n = 6), pentobarbital (n = 8), ethanol + pentobarbital (n = 15), and ethanol + pentobarbital + CX717 (n = 15). *Significant difference compared with control (P < 0.05). #Significant difference compared with all other groups (P < 0.05). NSNo significant difference relative to control (P > 0.05).

Table 1.

Effects of drugs on survival rate of adult rats

| Age | Groups | Animals Tested | Animals Survived |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adult | Ethanol (2 g/kg) | 5 | 5* |

| Pento (56 mg/kg) | 5 | 5* | |

| Ethanol + Pento | 16 | 8 | |

| CX717 (30 mg/kg) administered within 30 s of apnea after ethanol + Pento | 13 | 12* | |

| BIC (2 mg/kg) administered within 30 s of apnea after ethanol + Pento | 8 | 8* | |

| CX717 (30 mg/kg) administered after 60 s of apnea after ethanol + Pento | 5 | 3 | |

| BIC (2 mg/kg) administered after 60 s of apnea after ethanol + Pento | 4 | 2 | |

| Neonate | Ethanol (2 g/kg) | 6 | 6* |

| Pento (28 mg/kg) | 8 | 8* | |

| Ethanol + Pento | 15 | 5 | |

| CX717 (30 mg/kg) administered after ethanol + Pento | 15 | 12* |

Pento, pentobarbital.

Significant difference from ethanol + pento co-administration group by z-test (P < 0.05).

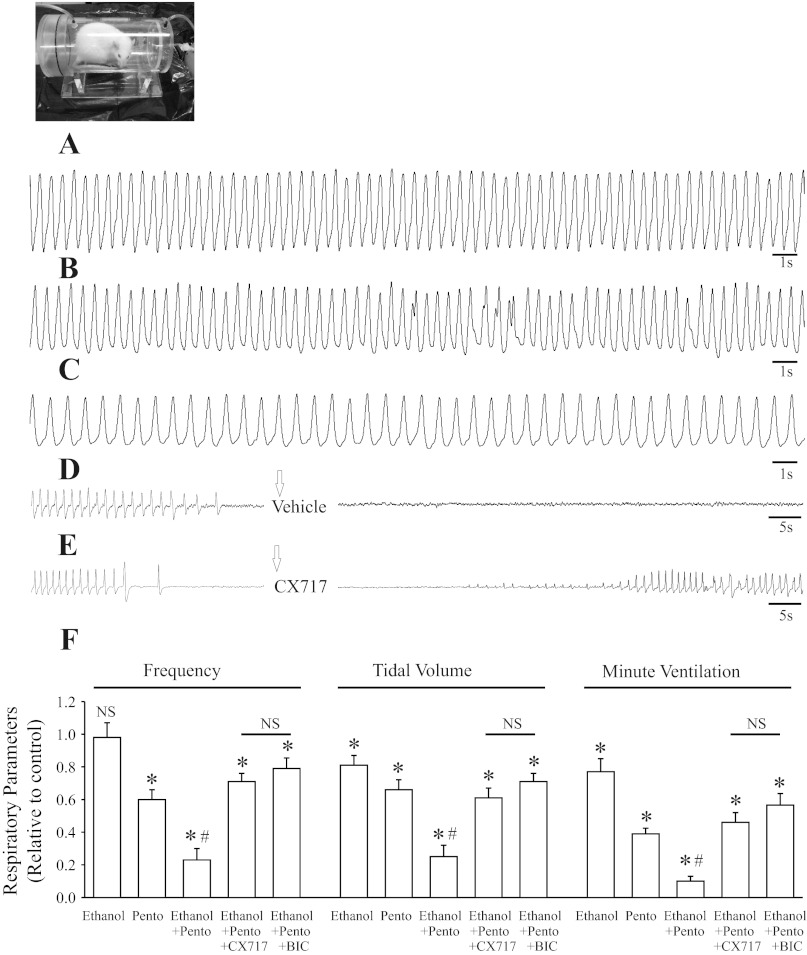

In vivo adult rat plethysmographic recordings.

Figure 4 shows data from whole-body plethysmographic recordings of respiratory activity from unrestrained adult rats in control and ∼60 min after drug administration. The baseline breathing frequency varied among the adult rats, with an average of 134 ± 6 breaths/min (n = 39), close to an average of ∼130 breaths/min (34). Ethanol (2 g/kg; n = 5) induced a significant suppression of Vt (81 ± 6% of control) and V̇e (77 ± 8%) without a significant effect on fR (98 ± 9% of control). Pentobarbital (56 mg/kg; n = 5) administration resulted in a significant suppression of fR (80 ± 6% of control), Vt (66 ± 6% of control), and V̇e (39 ± 3%). The combination of administering ethanol (2 g/kg) and pentobarbital (56 mg/kg) caused a severe depression of fR (23 ± 7% of control), Vt (25 ± 7% of control), and V̇e (10 ± 3%) and induced lethal apneas (in 8 of 16 animals; Table 1).

Fig. 4.

Co-administration of ethanol and pentobarbital caused a marked suppression of respiratory activity in adult rats. Traces A–E show whole-body plethysmographic recordings from unrestrained adult rats. A: control. B: ethanol (2 g/kg ip). C: pentobarbital (pento; 56 mg/kg ip). D: combined administration of ethanol (2 g/kg ip) and pentobarbital (56 mg/kg ip) with intervention of vehicle (10% HPCD ip; arrow bar) administration. E: combined administration of ethanol (2 g/kg ip) and pentobarbital (56 mg/kg ip) with intervention of CX717 (30 mg/kg ip; arrow bar) administration. F: population data showing respiratory parameters (relative to control): fR, Vt, and V̇e after treatment with ethanol (n = 5), pento (n = 5), ethanol + pento (n = 16), ethanol + pento + CX717 (n = 13), and ethanol + pento + bicuculline (n = 8). *Significant difference from control (P < 0.05). #Significant difference from all other groups (P < 0.05). NSNo significant difference relative to control or between two compared groups (P > 0.05).

Administration of vehicle (10% HPCD) did not change the course of respiratory depression and lethal apnea induced by the combination of ethanol and pentobarbital (Fig. 4D), whereas 12 of 13 animals survived after administration of CX717 (30 mg/kg ip; ∼45–60 min after ethanol-pentobarbital administration) despite receiving what was normally a lethal dose of ethanol-pentobarbital combination (Fig. 4E; Table 1). Similarly, administration of BIC (2 mg/kg ip; ∼45–60 min after ethanol-pentobarbital administration) rescued all eight adult rats tested from ethanol plus pentobarbital-induced lethal apneas if applied within 30 s of onset of apneas. Delay of delivery of CX717 or BIC until 1 min after the appearance of ethanol plus pentobarbital-induced apneas reduced the rescue rate to three of five rats and two of four rats tested, respectively. As reported previously (24), administration of CX717 (30 mg/kg; n = 4) alone did not cause any seizure-like activity or result in significant changes of baseline respiratory parameters after CX717. However, after BIC (2 mg/kg), four of eight animals examined developed seizure-like activity and altered respiratory pattern during the seizure period.

Effects on core temperature and oxygen saturation in adult rats.

Table 2 shows data from adult rats in control and ∼50 min after drug administration on the effects of core temperature and oxygen saturation. Ethanol (2 g/kg ip) administration did not significantly change core temperature and oxygen saturation levels, whereas pentobarbital (56 mg/kg ip) alone and with ethanol (2 g/kg ip) caused significant decreases in body temperature and oxygen saturation levels compared with the animals before drug administration. Note that the oxygen saturation and body temperature were markedly lower after ethanol-pentobarbital co-administration relative to control. The enhanced respiratory activity in the presence of CX717 (30 mg/kg ip) helped maintain body temperature and oxygen saturation levels.

Table 2.

Effects of drugs on core temperature and oxygen saturation of adult rats

| Groups | Animals | Temperature, °C | Oxygen Saturation, % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 4 | 38.1 ± 0.1 | 96.1 ± 1.3 |

| Ethanol, 2 g/kg | 3 | 37.6 ± 0.2 | 94.0 ± 2.3 |

| Pento, 56 mg/kg | 3 | 35.3 ± 0.4† | 85.1 ± 3.9† |

| Ethanol + Pento | 4 | 34.7 ± 0.3* | 62.4 ± 4.1* |

| Ethanol + Pento with CX717 | 3 | 36.2 ± 0.4† | 84.5 ± 4.0† |

In CX717 treatment group, CX717 (30 mg/kg) was administered 20 min before measurements.

Significant difference from all other groups (P < 0.05).

Significant difference from control (P < 0.05).

Responses to hypoxia and hypercapnia in adult rats.

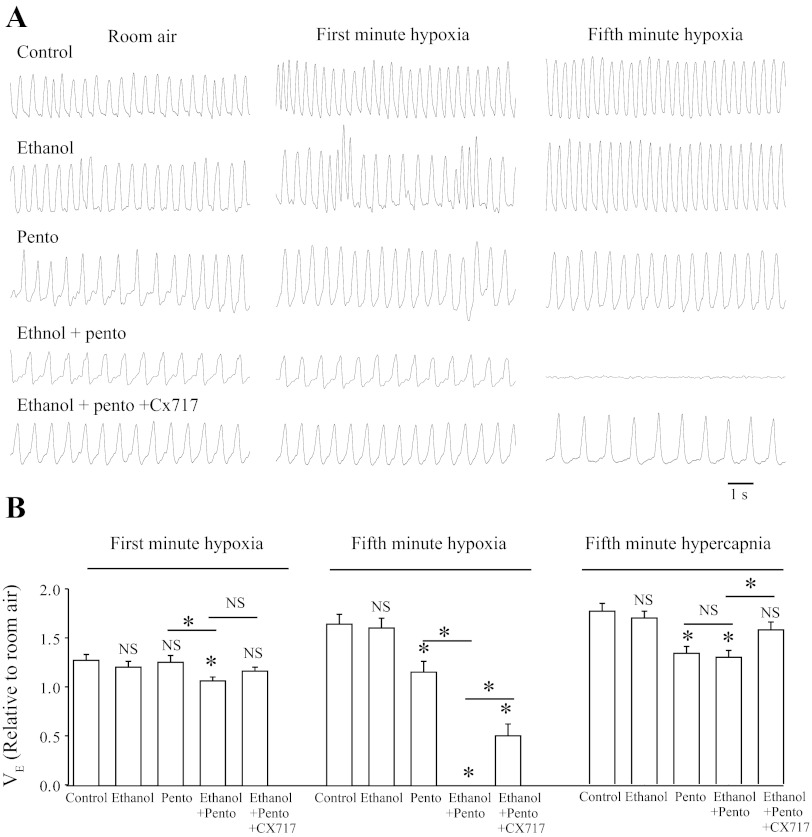

V̇e was measured during hypoxia (5-min exposure to 8% O2) or hypercapnia (5-min exposure to 5% CO2) and reported relative to that observed in control room air conditions. Data was compared after 40-min exposure to vehicle, ethanol, and/or pentobarbital, at a time when no lethal apneas were induced by co-administration of ethanol-pentobarbital. Figure 5A shows representative plethysmographic recordings in response to hypoxia under various conditions. The group data is shown in Fig. 5B. Exposure to hypoxia caused an increase in V̇e to 128 ± 6 and 165 ± 10% of control in the untreated rats (n = 4) during minutes 1 and 5 of exposure (after 30 s of gas exchange equilibration), respectively. Ethanol (2 g/kg; n = 5) alone did not significantly change the responses to hypoxia at either time point. Pentobarbital (56 mg/kg; n = 5) alone caused a blunted response to hypoxia during the last minute of hypoxic exposure (V̇e increased to 116 ± 11%) but did not change the response to minute 1 of hypoxia. Co-administration of ethanol (2 g/kg) and pentobarbital (56 mg/kg) caused a significantly blunted response to hypoxia in minute 1 (P = 0.013 vs. control group) and terminal apnea (P < 0.001 vs. control group) by minute 5 in all eight rats tested. Preadministration with CX717 (30 mg/kg) ∼10 min before the hypoxic challenge in rats co-administered ethanol and pentobarbital significantly alleviated the respiratory depression during minutes 1 and 5 and ultimately prevented lethality in three of eight rats.

Fig. 5.

Altered responses to hypoxia and hypercapnia after administration of ethanol and pentobarbital in adult rats. A: plethysmographic recordings from adult rats after exposure to hypoxia (5 min 8% O2, balanced with N2). Traces shown are control (top), ethanol (2 g/kg ip; second), pentobarbital (pento; 56 mg/kg ip; third), ethanol (2 g/kg ip) plus pento (56 mg/kg ip; fourth), and ethanol (2 g/kg ip) plus pento (56 mg/kg ip) plus CX717 (30 mg/kg ip; bottom). B: population data showing minute volume (V̇e) during hypercapnia (5% CO2; n = 3–4 each) or hypoxia (8% O2) exposure relative to room air (21% O2): control (n = 4), ethanol (n = 5), pento (n = 5), ethanol + pento (n = 8), ethanol + pento + CX717 (n = 8). *Significant difference relative to control or between two compared groups (P < 0.05). NSNo significant difference relative to control or between two compared groups (P > 0.05).

Figure 5B includes the data for responses to hypercapnia. All groups of animals tested had no significant difference in response to hypercapnia during minute 1 of 5% CO2. At minute 5 of hypercapnia, pentobarbital (56 mg/kg; P = 0.006 vs. control group; n = 4) alone or co-administered with ethanol (2 g/kg; P = 0.004 vs. control group; n = 4) caused a blunted response to hypercapnia, whereas ethanol (2 g/kg; n = 4) did not change the response to hypercapnia compared with control group. The blunted response to hypercapnia after ethanol-pentobarbital administration was alleviated by pre-administration of CX717 (30 mg/kg; P = 0.037 vs. ethanol-pentobarbital group; n = 3).

DISCUSSION

Most overdoses of depressant medications arise from mixtures of drugs, commonly involving alcohol, barbiturates, or opiates. In this study, we demonstrated that ethanol and pentobarbital have a synergistic action when co-administered and cause severe respiratory depression, including lethal apnea. There are likely to be several mechanisms underlying the synergistic action of the drugs. Data from the in vitro brain stem-spinal cord preparation provide insights on drug interactions independent of supramedullary centers and peripheral afferent input to the respiratory rhythm-generating center. Ethanol, at the concentrations administered to the bathing medium, caused a modest suppression of respiratory frequency in vitro without a significant change in amplitude, consistent with a previous in vitro study (5). The concentration of pentobarbital administered caused an ∼50% reduction of frequency, which is also consistent with previous studies using a similar in vitro preparation (7, 38). The administration of both agents together led to a pronounced suppression of respiratory frequency, including induction of complete apnea. The administration of the GABAA receptor antagonist bicuculline countered the majority of ethanol- and pentobarbital-induced respiratory depression in vitro, which is consistent with the two agents working primarily via modulation of GABAA receptor opening. Specifically, pentobarbital enhances GABA-mediated chloride currents by increasing the duration of ionophore opening at low doses, and at high doses it stimulates GABAA receptors directly in the absence of GABA. Ethanol binds to a distinct site on the GABAA receptor (41). At the single channel level, ethanol enhances the frequency of GABA-mediated channel opening events and mean open time. There is also evidence for a presynaptic facilitation of GABA release by ethanol at some synapses. The net functional implication is that the combinatorial exposure to barbiturates and ethanol results in a strong synergistic increase in GABAA receptor-mediated conductance. This would result in inhibition of respiratory neurons at multiple sites, including those located within the preBötC.

The data from newborn and adult rat in vivo studies were consistent with the in vitro results; the combination of ethanol and pentobarbital, at doses that on their own cause partial respiratory depression, resulted in pronounced apneas that could be lethal. In vivo, the combinatorial actions of alcohol and pentobarbital will be beyond simple depression of medullary respiratory rhythm-generating centers. There may be compromised degradation of each class of compound when both are present in the circulation due to interference with liver function (33). Alcohol, opiates, and perhaps other sedative agents can indirectly modulate respiratory drive via effects on state-dependent/arousal-related processes (24, 25, 39). Furthermore, data in this study demonstrate a marked suppression of hypoxia- and hypercapnia-induced regulatory reflexes in the presence of alcohol and pentobarbital. The fact that exposure to what is normally a well tolerated level of hypoxia was lethal in all cases when ethanol and pentobarbital were administered was particularly striking. These marked accentuated inhibitory actions of hypoxia may include direct effects of alcohol-pentobarbital on chemoreceptors, neuronal circuitry that processes reflex input (45), and accentuation of the suppression of respiratory drive in the medulla in response to elevated GABA release with hypoxia (13, 19, 44). There was also a blunting of the reflex stimulatory response to hypercapnia in the presence of pentobarbital on its own or in conjunction with alcohol. Collectively, the functional consequences of these drug-induced alterations in chemosensitivity are that there is less protection against the hypoventilation and apneas induced by the central actions of the agents.

The fact that administration of bicuculline countered a significant component of the alcohol-pentobarbital-induced respiratory depression via blocking of GABAA receptor-mediated effects was informative regarding mechanism. However, bicuculline also induces nonrespiratory, seizure-like neuronal activity that would negate clinical use. The administration of the ampakine CX717 was also effective for partially alleviating the drug-induced respiratory depression, and it has been shown to be well tolerated at therapeutic doses. We propose that part of the CX717 mechanism of action is via positive allosteric modulation of AMPA receptors within the preBötC network. Increased current flow through the AMPA receptor on those neurons would counter the suppressing actions of alcohol and pentobarbital via both GABA-mediated conductances and their additional inhibitory actions directly at AMPA receptors (8, 18, 40, 43). This is similar to the mode of action proposed for the ampakine-mediated alleviation of opiates acting, in part, by suppressing preBötC excitability via binding to μ-opiate receptors (27, 30). In addition, it is likely that CX717 provides positive respiratory drive via action at other brain stem and supramedullary neuronal structures that modulate breathing.

In conclusion, these data suggest that exposure to both alcohol and barbiturates can lead to a much more profound suppression of breathing than with either agent in isolation. Furthermore, ampakine compounds, which also counter opiate-induced respiratory depression, can alleviate GABAA receptor-mediated suppression of central respiratory drive and thus may offer a novel pharmacological approach to counter a wider range of drug-induced central hypoventilation and apnea.

GRANTS

Research was supported by the Canadian Institutes for Health Research (CIHR) and Alberta Advanced Education and Technology. J. Ren received Studentships from the Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research (AHFMR, Edmonton, AB) and CIHR. J. J. Greer is a Scientist of the Alberta Innovates-Health Solutions (AHIS; formerly AHFMR).

DISCLOSURES

Ampakines were provided by Cortex Pharmaceuticals.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: J.R. and X.D. performed experiments; J.R. and X.D. analyzed data; J.R. and J.J.G. interpreted results of experiments; J.R. and J.J.G. prepared figures; J.R. and J.J.G. drafted manuscript; J.R. and J.J.G. edited and revised manuscript; J.R., X.D., and J.J.G. approved final version of manuscript; J.J.G. conception and design of research.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abrams RC.American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry (AAGP) 2010 Annual Meeting: Abs NR5; Presented March 6, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Arai AC, Xia YF, Suzuki E. Modulation of AMPA receptor kinetics differentially influences synaptic plasticity in the hippocampus. Neuroscience 123: 1011–1024, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bogan J, Smith H. Analytical investigations of barbiturate poisoning: description of methods and a survey of results. Forensic Sci Soc 7: 37–45, 1967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Brockhaus J, Ballanyi K. Synaptic inhibition in the isolated respiratory network of neonatal rats. Eur J Neurosci 10: 3823–3839, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Di Pasquale E, Monteau R, Hilaire G, Iscoe S. Effects of ethanol on respiratory activity in the neonatal rat brainstem-spinal cord preparation. Brain Res 695: 271–274, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Doraiswamy PM, Xiong GL. Pharmacological strategies for the prevention of Alzheimer's disease. Expert Opin Pharmacother 7: 1–10, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fregosi RF, Luo Z, Lizuka M. GABAA receptors mediate postnatal depression of respiratory frequency by barbiturates. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 140: 219–230, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Frye GD, Fincher A. Sustained ethanol inhibition of native AMPA receptors on medial septum/diagonal band (MS/DB) neurons. Br J Pharmacol 129: 87–94, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Funk GD, Smith JC, Feldman JL. Generation and transmission of respiratory oscillations in medullary slices: role of excitatory amino acids. J Neurophysiol 70: 1497–1515, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Greenblatt DJ, Allen MD, Harmatz JS, Noel BJ, Shader RI. Overdose with pentobarbital and secobarbital-assessment of factors related to outcome. J Clin Pharmacol 19: 758–768, 1979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Greer JJ, Smith JC, Feldman JL. The role of excitatory amino acids in the generation and transmission of respiratory drive in the neonatal rat. J Physiol 437: 727–749, 1991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Greer JJ, Smith JC, Feldman JL. Generation of respiratory and locomotor patterns by an in vitro brainstem-spinal cord fetal rat preparation. J Neurophysiol 67: 996–999, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hayashi F, Fukuda Y. Neuronal mechanisms mediating the integration of respiratory responses to hypoxia. Jpn J Physiol 50: 15–24, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jones AW. Alcohol and drug interactions. In: Handbook of Drug Interactions: A Clinical and Forensic Guide, edited by Mozayani A, Raymon LP. Totowa, NJ: Humana, 2003, p. 395–462 [Google Scholar]

- 15. Liu G, Feldman JL, Smith JC. Excitatory amino acid-mediated transmission of inspiratory drive to phrenic motoneurons. J Neurophysiol 64: 423–436, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lorier AR, Funk GD, Greer JJ. Opiate-induced suppression of rat hypoglossal motoneuron activity and its reversal by ampakine therapy. PLos One 5: e8766, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lynch G. Glutamate-based therapeutic approaches: ampakines. Curr Opin Pharmacol 6: 82–88, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Martin D, Tayyeb MI, Swartzwelder HS. Ethanol inhibition of AMPA and kainate receptor-mediated depolarizations of hippocampal area CA1. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 19: 1312–1316, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Melton JE, Neubauer JA, Edelman NH. GABA antagonism reverses hypoxic respiratory depression in the cat. J Appl Physiol 9: 1296–1301, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mortola JP, Frappell PB. On the barometric method for measurements of ventilation, and its use in small animals. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 76: 937–944, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Oertel BG, Felden L, Tran PV, Bradshaw MH, Angst MS, Schmidt H, Johnson S, Greer JJ, Geisslinger G, Varney MA, Lötsch J. Selective antagonism of opioid-induced ventilatory depression by an ampakine molecule in humans without loss of opioid analgesia. Clin Pharmacol Ther 87: 204–211, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Olin BR, Hebel SK, Dewein AC. (editors). Drug Facts and Comparisons. St. Louis, MO: Lippincott, Williams, and Wilkins, 1995, p. 242–245 [Google Scholar]

- 23. Pace RW, Mackay DD, Feldman JL, Del Negro CA. Inspiratory bursts in the preBötzinger complex depend on a calcium-activated non-specific cation current linked to glutamate receptors in neonatal mice. J Physiol 582: 113–125, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pattinson KT. Opioids and the control of respiration. Br J Anaesth 100: 747–758, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pattinson KT, Governo RJ, MacIntosh BJ, Russell EC, Corfield DR, Tracey I, Wise RG. Opioids depress cortical centers responsible for the volitional control of respiration. J Neurosci 29: 8177–8186, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Porrino LJ, Daunais JB, Rogers GA, Hampson RE, Deadwyler SA. Facilitation of task performance and removal of the effects of sleep deprivation by an ampakine (CX717) in nonhuman primates. PLoS Biol 3: e299, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ren J, Ding X, Funk GD, Greer JJ. Ampakine CX717 protects against fentanyl-induced respiratory depression and lethal apnea in rats. Anesthesiology 110: 1364–1370, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ren J, Greer JJ. Modulation of respiratory rhythmogenesis by chloride mediated conductances during the perinatal period. J Neurosci 26: 3721–3730, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ren J, Greer JJ. Neurosteroid modulation of respiratory rhythm in rats during the perinatal period. J Physiol 574: 535–546, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ren J, Poon BY, Tang Y, Funk GD, Greer JJ. Ampakines alleviate respiratory depression in rats. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 174: 1384–1391, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Schears Barbiturates RM. In: Tintinalli JE, Kelen GD, Stapczynski JS, Ma OJ, Cline DM. (editors). Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide (6th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill, 2004, chapt. 163 [Google Scholar]

- 32. Schuckit MA. Drug and Alcohol Abuse: A Clinical Guide to Diagnosis and Treatment, edited by Schuckit MA. New York: Springer, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 33. Seidel G. Distribution of pentobarbital, barbital and thiopental under ethanol. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Exp Pathol Pharmakol 257: 221–229, 1967 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Seifert El Knowles J, Mortola JP. Continuous circadian measurements of ventilation in behaving adult rats. Respir Physiol 120: 179–183, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Shao XM, Feldman JL. Respiratory rhythm generation and synaptic inhibition of expiratory neurons in pre-Botzinger complex: differential roles of glycinergic and GABAergic neural transmission. J Neurophysiol 77: 1853–1860, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sigel E. Mapping of the benzodiazepine recognition site on GABA(A) receptors. Curr Top Med Chem 2: 833–839, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Smith JC, Greer JJ, Liu GS, Feldman JL. Neural mechanisms generating respiratory pattern in mammalian brain stem-spinal cord in vitro. I. Spatiotemporal patterns of motor and medullary neuron activity. J Neurophysiol 64: 1149–1169, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Tarasiuk A, Grossman Y, Kendig JJ. Barbiturate alteration of respiratory rhythm and drive in isolated brainstem-spinal cord of newborn rat: studies at normal and hyperbaric pressure. Br J Anaesth 66: 88–96, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Vecchio LM, Grace KP, Liu H, Harding S, Lê AD, Horner RL. State-dependent vs. central motor effects of ethanol on breathing. J Appl Physiol 108: 387–400, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wang MY, Rampil IJ, Kendig JJ. Ethanol directly depresses AMPA and NMDA glutamate currents in spinal cord motor neurons independent of actions on GABAA or glycine receptors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 290: 362–367, 1999 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Weiner Valenzuela CFJL. Ethanol modulation of GABAergic transmission: the view from the slice. Pharmacol Ther 111: 533–554, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wesensten NJ, Reichardt RM, Balkin TJ. Ampakine (CX717) effects on performance and alertness during simulated night shift work. Aviat Space Environ Med 78: 937–943, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Wirkner K, Eberts C, Poelchen W, Allgaier C, Illes P. Mechanism of inhibition by ethanol of NMDA and AMPA receptor channel functions in cultured rat cortical neurons. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 362: 568–576, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wood JB, Watson WJ, Drucker AJ. The effect of hypoxia on brain gamma-aminobutyric acid levels. J Neurochem 15: 603–608, 1981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Zuperku EJ, McCrimmon DR. Gain modulation of respiratory neurons. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 131: 121–133, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]