Abstract

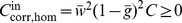

Correlations in spike-train ensembles can seriously impair the encoding of information by their spatio-temporal structure. An inevitable source of correlation in finite neural networks is common presynaptic input to pairs of neurons. Recent studies demonstrate that spike correlations in recurrent neural networks are considerably smaller than expected based on the amount of shared presynaptic input. Here, we explain this observation by means of a linear network model and simulations of networks of leaky integrate-and-fire neurons. We show that inhibitory feedback efficiently suppresses pairwise correlations and, hence, population-rate fluctuations, thereby assigning inhibitory neurons the new role of active decorrelation. We quantify this decorrelation by comparing the responses of the intact recurrent network (feedback system) and systems where the statistics of the feedback channel is perturbed (feedforward system). Manipulations of the feedback statistics can lead to a significant increase in the power and coherence of the population response. In particular, neglecting correlations within the ensemble of feedback channels or between the external stimulus and the feedback amplifies population-rate fluctuations by orders of magnitude. The fluctuation suppression in homogeneous inhibitory networks is explained by a negative feedback loop in the one-dimensional dynamics of the compound activity. Similarly, a change of coordinates exposes an effective negative feedback loop in the compound dynamics of stable excitatory-inhibitory networks. The suppression of input correlations in finite networks is explained by the population averaged correlations in the linear network model: In purely inhibitory networks, shared-input correlations are canceled by negative spike-train correlations. In excitatory-inhibitory networks, spike-train correlations are typically positive. Here, the suppression of input correlations is not a result of the mere existence of correlations between excitatory (E) and inhibitory (I) neurons, but a consequence of a particular structure of correlations among the three possible pairings (EE, EI, II).

Author Summary

The spatio-temporal activity pattern generated by a recurrent neuronal network can provide a rich dynamical basis which allows readout neurons to generate a variety of responses by tuning the synaptic weights of their inputs. The repertoire of possible responses and the response reliability become maximal if the spike trains of individual neurons are uncorrelated. Spike-train correlations in cortical networks can indeed be very small, even for neighboring neurons. This seems to be at odds with the finding that neighboring neurons receive a considerable fraction of inputs from identical presynaptic sources constituting an inevitable source of correlation. In this article, we show that inhibitory feedback, abundant in biological neuronal networks, actively suppresses correlations. The mechanism is generic: It does not depend on the details of the network nodes and decorrelates networks composed of excitatory and inhibitory neurons as well as purely inhibitory networks. For the case of the leaky integrate-and-fire model, we derive the correlation structure analytically. The new toolbox of formal linearization and a basis transformation exposing the feedback component is applicable to a range of biological systems. We confirm our analytical results by direct simulations.

Introduction

Neurons generate signals by weighting and combining input spike trains from

presynaptic neuron populations. The number of possible signals which can be read out

this way from a given spike-train ensemble is maximal if these spike trains span an

orthogonal basis, i.e. if they are uncorrelated [1]. If they are correlated, the

amount of information which can be encoded in the spatio-temporal structure of these

spike trains is limited. In addition, correlations impair the ability of readout

neurons to decode information reliably in the presence of noise. This is often

discussed in the context of rate coding: for  uncorrelated spike trains, the signal-to-noise ratio of the

compound spike-count signal can be enhanced by increasing the population size

uncorrelated spike trains, the signal-to-noise ratio of the

compound spike-count signal can be enhanced by increasing the population size

. In the presence of

correlations, however, the signal-to-noise ratio is bounded [2], [3]. The same reasoning holds for

any other linear combination of spike trains, also for those where exact spike

timing matters (for example for the coding scheme presented in [4]). Thus, the robustness of

neuronal responses against noise critically depends on the level of correlated

activity within the presynaptic neuron population.

. In the presence of

correlations, however, the signal-to-noise ratio is bounded [2], [3]. The same reasoning holds for

any other linear combination of spike trains, also for those where exact spike

timing matters (for example for the coding scheme presented in [4]). Thus, the robustness of

neuronal responses against noise critically depends on the level of correlated

activity within the presynaptic neuron population.

Several studies suggested that correlated neural activity could be beneficial for information processing: Spike-train correlations can modulate the gain of postsynaptic neurons and thereby constitute a gating mechanism (for a review, see [4]). Coherent spiking activity might serve as a means to bind elementary representations into more complex objects [5], [6]. Information represented by correlated firing can be reliably sustained and propagated through feedforward subnetworks (‘synfire chains’; [7], [8]). Whether correlated firing has to be considered favorable or not largely depends on the underlying hypothesis, the type of correlation (e.g. the time scale or the affected frequency band) or which subpopulations of neurons are involved. Most ideas suggesting a functional benefit of correlated activity rely on the existence of an asynchronous ‘ground state’. Spontaneously emerging correlations, i.e. correlations which are not triggered by internal or external events, would impose a serious challenge to many of these hypotheses. Functionally relevant synfire activity, for example, cannot be guaranteed in the presence of correlated background input from the embedding network [9]. It is therefore–from several perspectives–important to understand the origin of uncorrelated activity in neural networks.

It has recently been shown that spike trains of neighboring cortical neurons can indeed be uncorrelated [10]. Similar results have been obtained in several theoretical studies [11]–[17]. From an anatomical point of view, this observation is puzzling: in general, neurons in finite networks share a certain fraction of their presynaptic sources. In particular for neighboring neurons, the overlap between presynaptic neuron populations is expected to be substantial. This feedforward picture suggests that such presynaptic overlap gives rise to correlated synaptic input and, in turn, to correlated response spike trains.

A number of theoretical studies showed that shared-input correlations are only weakly transferred to the output side as a consequence of the nonlinearity of the spike-generation dynamics [15], [18]–[21]. Unreliable spike transmission due to synaptic failure can further suppress the correlation gain [22]. In [9], we demonstrated that spike-train correlations in finite-size recurrent networks are even smaller than predicted by the low correlation gain of pairs of neurons with nonlinear spike-generation dynamics. We concluded that this suppression of correlations must be a result of the recurrent network dynamics. In this article, we compare correlations observed in feedforward networks to correlations measured in systems with an intact feedback loop. We refer to the reduction of correlations in the presence of feedback as “decorrelation”. Different mechanisms underlying such a dynamical decorrelation have been suggested in the recent past. Asynchronous states in recurrent neural networks are often attributed to chaotic dynamics [23], [24]. In fact, networks of nonlinear units with random connectivity and balanced excitation and inhibition typically exhibit chaos [11], [25]. The high sensitivity to noise may however question the functional relevance of such systems ([26], [27]; cf., however, [28]). [29] and [27] demonstrated that asynchronous irregular firing can also emerge in networks with stable dynamics. Employing an analytical framework of correlations in recurrent networks of binary neurons [30], the balance of excitation and inhibition has recently been proposed as another decorrelation mechanism [17]: In large networks, fluctuations of excitation and inhibition are in phase. Positive correlations between excitatory and inhibitory input spike trains lead to a negative component in the net input correlation which can compensate positive correlations caused by shared input.

In the present study, we demonstrate that dynamical decorrelation is a fundamental phenomenon in recurrent systems with negative feedback. We show that negative feedback alone is sufficient to efficiently suppress correlations. Even in purely inhibitory networks, shared-input correlations are compensated by feedback. A balance of excitation and inhibition is thus not required. The underlying mechanism can be understood by means of a simple linear model. This simplifies the theory and helps to gain intuition, but it also confirms that low correlations can emerge in recurrent networks with stable, non-chaotic dynamics.

The suppression of pairwise spike-train correlations by inhibitory feedback is

reflected in a reduction of population-rate fluctuations. The main effect described

in this article can therefore be understood by studying the dynamics of the

macroscopic population activity. This approach leads to a simple mathematical

description and emphasizes that the described decorrelation mechanism is a general

phenomenon which may occur not only in neural networks but also in other

(biological) systems with inhibitory feedback. In “

Results

: Suppression of

population-rate fluctuations in LIF networks”, we first illustrate

the decorrelation effect for random networks of  leaky integrate-and-fire (LIF) neurons with inhibitory or

excitatory-inhibitory coupling. By means of simulations, we show that low-frequency

spike-train correlations, and, hence, population-rate fluctuations are substantially

smaller than expected given the amount of shared input. As shown in the subsequent

section, the “Suppression of population-activity fluctuations by

negative feedback” can readily be understood in the framework of a

simple one-dimensional linear model with negative feedback. In

“

Results

: Population-activity fluctuations in

excitatory-inhibitory networks”, we extend this to a two-population

system with excitatory-inhibitory coupling. Here, a simple coordinate transform

exposes the inherent negative feedback loop as the underlying cause of the

fluctuation suppression in inhibition-dominated networks. The population-rate models

of the inhibitory and the excitatory-inhibitory network are sufficient to understand

the basic mechanism underlying the decorrelation. They do, however, not describe how

feedback in cortical networks affects the detailed structure of pairwise

correlations. In “

Results

: Population averaged correlations in

cortical networks”, we therefore compute self-consistent population

averaged correlations for a random network of

leaky integrate-and-fire (LIF) neurons with inhibitory or

excitatory-inhibitory coupling. By means of simulations, we show that low-frequency

spike-train correlations, and, hence, population-rate fluctuations are substantially

smaller than expected given the amount of shared input. As shown in the subsequent

section, the “Suppression of population-activity fluctuations by

negative feedback” can readily be understood in the framework of a

simple one-dimensional linear model with negative feedback. In

“

Results

: Population-activity fluctuations in

excitatory-inhibitory networks”, we extend this to a two-population

system with excitatory-inhibitory coupling. Here, a simple coordinate transform

exposes the inherent negative feedback loop as the underlying cause of the

fluctuation suppression in inhibition-dominated networks. The population-rate models

of the inhibitory and the excitatory-inhibitory network are sufficient to understand

the basic mechanism underlying the decorrelation. They do, however, not describe how

feedback in cortical networks affects the detailed structure of pairwise

correlations. In “

Results

: Population averaged correlations in

cortical networks”, we therefore compute self-consistent population

averaged correlations for a random network of  linear excitatory and inhibitory neurons. By determining the parameters of the

linear network analytically from the LIF model, we show that the predictions of the

linear model are—for a wide and realistic range of parameters—in

excellent agreement with the results of the LIF network model. In

“

Results

: Effect of feedback

manipulations”, we demonstrate that the active decorrelation in

random LIF networks relies on the feedback of the (sub)population averaged activity

but not on the precise microscopic structure of the feedback signal. In the

“

Discussion

”, we put the consequences of

this work into a broader context and point out limitations and possible extensions

of the presented theory. The “

Methods

” contain details on the LIF

network model, the derivation of the linear model from the LIF dynamics and the

derivation of population-rate spectra and population averaged correlations in the

framework of the linear model. This section is meant as a supplement; the basic

ideas and the main results can be extracted from the “

Results

”.

linear excitatory and inhibitory neurons. By determining the parameters of the

linear network analytically from the LIF model, we show that the predictions of the

linear model are—for a wide and realistic range of parameters—in

excellent agreement with the results of the LIF network model. In

“

Results

: Effect of feedback

manipulations”, we demonstrate that the active decorrelation in

random LIF networks relies on the feedback of the (sub)population averaged activity

but not on the precise microscopic structure of the feedback signal. In the

“

Discussion

”, we put the consequences of

this work into a broader context and point out limitations and possible extensions

of the presented theory. The “

Methods

” contain details on the LIF

network model, the derivation of the linear model from the LIF dynamics and the

derivation of population-rate spectra and population averaged correlations in the

framework of the linear model. This section is meant as a supplement; the basic

ideas and the main results can be extracted from the “

Results

”.

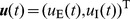

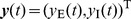

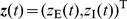

Results

In a recurrent neural network of size  , each

neuron

, each

neuron  receives in general

inputs from two different types of sources: External inputs

receives in general

inputs from two different types of sources: External inputs  representing the sum of afferents from other brain areas,

and local inputs resulting from the recurrent connectivity within the network.

Depending on their origin, external inputs

representing the sum of afferents from other brain areas,

and local inputs resulting from the recurrent connectivity within the network.

Depending on their origin, external inputs  and

and

to different neurons

to different neurons

and

and  can be correlated or not. Throughout this manuscript, we

ignore correlations between these external sources, thereby ensuring that

correlations within the network activity arise from the local connectivity alone and

are not imposed by external inputs [17]. The local inputs feed the network's spiking

activity

can be correlated or not. Throughout this manuscript, we

ignore correlations between these external sources, thereby ensuring that

correlations within the network activity arise from the local connectivity alone and

are not imposed by external inputs [17]. The local inputs feed the network's spiking

activity  back to the network

(we refer to spike train

back to the network

(we refer to spike train  , the

, the  th component of the column vector

th component of the column vector  [the superscript “

[the superscript “ ” denotes the transpose], as a sum over

delta-functions centered at the spike times

” denotes the transpose], as a sum over

delta-functions centered at the spike times  :

:

; the abstract quantity

‘spike train’ can be considered as being derived from the observable

quantity ‘spike count’

; the abstract quantity

‘spike train’ can be considered as being derived from the observable

quantity ‘spike count’  , the

number of spikes occurring in the time interval

, the

number of spikes occurring in the time interval  , by taking the limit

, by taking the limit  :

:

). The structure and

weighting of this feedback can be described by the network's connectivity

matrix

). The structure and

weighting of this feedback can be described by the network's connectivity

matrix  (see Fig. 1 A). In a finite network,

the local connectivity typically gives rise to overlapping presynaptic populations:

in a random (Erdös-Rényi) network with connection probability

(see Fig. 1 A). In a finite network,

the local connectivity typically gives rise to overlapping presynaptic populations:

in a random (Erdös-Rényi) network with connection probability

, for example, each

pair of postsynaptic neurons shares, on average,

, for example, each

pair of postsynaptic neurons shares, on average,  presynaptic sources. For a network size of, say,

presynaptic sources. For a network size of, say,

and a connection

probability

and a connection

probability  , this corresponds to a

fairly large number of

, this corresponds to a

fairly large number of  identical inputs. For

other network structures, the amount of shared input may be smaller or larger. Due

to this presynaptic overlap, each pair of neurons receives, to some extent,

correlated input (even if the external inputs are uncorrelated). One might therefore

expect that the network responses

identical inputs. For

other network structures, the amount of shared input may be smaller or larger. Due

to this presynaptic overlap, each pair of neurons receives, to some extent,

correlated input (even if the external inputs are uncorrelated). One might therefore

expect that the network responses  are

correlated as well. In this article, we show that, in the presence of negative

feedback, the effect of shared input caused by the structure of the network is

compensated by its recurrent dynamics.

are

correlated as well. In this article, we show that, in the presence of negative

feedback, the effect of shared input caused by the structure of the network is

compensated by its recurrent dynamics.

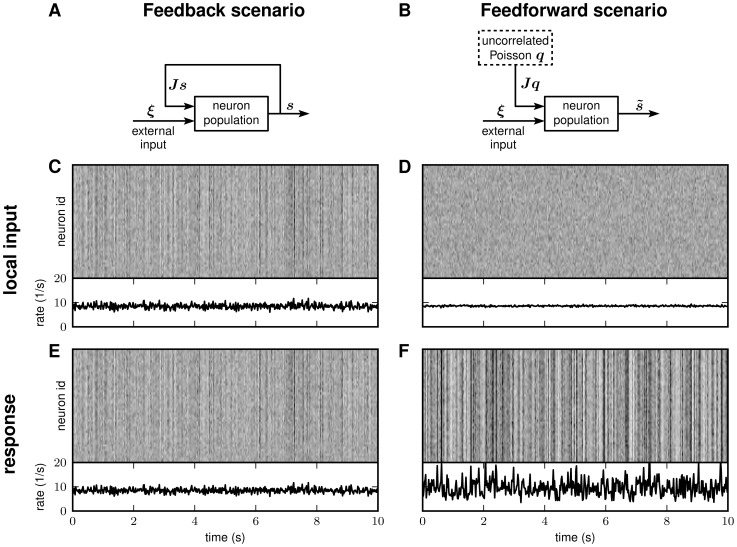

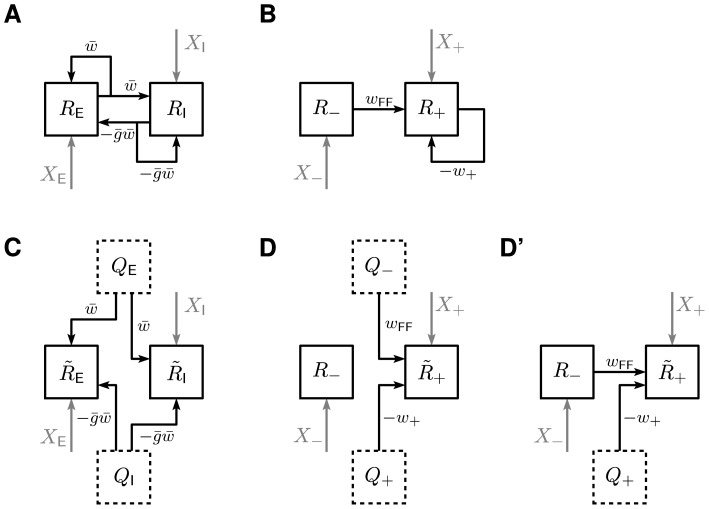

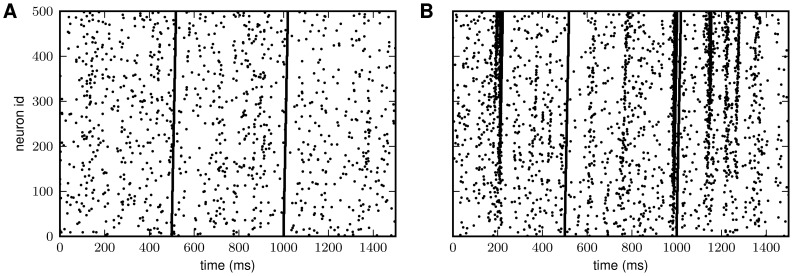

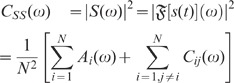

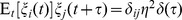

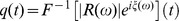

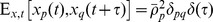

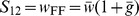

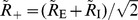

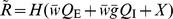

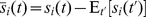

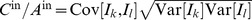

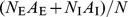

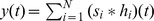

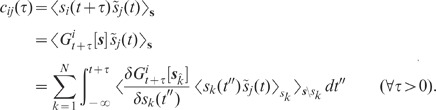

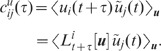

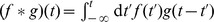

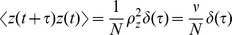

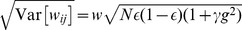

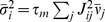

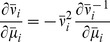

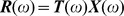

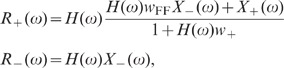

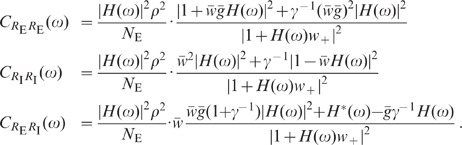

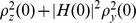

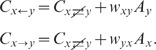

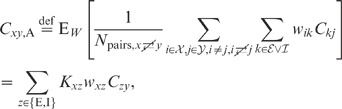

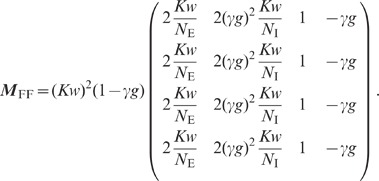

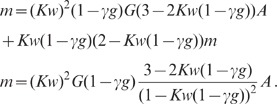

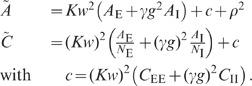

Figure 1. Spiking activity in excitatory-inhibitory LIF networks with intact (left column; feedback scenario) and opened feedback loop (right column; feedforward scenario).

A,B: Network sketches for the feedback (A) and feedforward

scenario (B). C,D: Spiking activity (top panels) and population

averaged firing rate (bottom panels) of the local presynaptic populations.

E,F: Response spiking activity (top panels) and population

averaged response rate (bottom panels). In the top panels of C–F, each

pixel depicts the number of spikes (gray coded) of a subpopulation of

neurons in a

neurons in a

time interval.

In both the feedback and the feedforward scenario, the neuron population

time interval.

In both the feedback and the feedforward scenario, the neuron population

is driven by

the same realization

is driven by

the same realization  of an

uncorrelated white-noise ensemble; local input is fed to the population

through the same connectivity matrix

of an

uncorrelated white-noise ensemble; local input is fed to the population

through the same connectivity matrix  . The in-degrees, the synaptic weights and the

shared-input statistics are thus exactly identical in the two scenarios. In

the feedback case (A), local presynaptic spike-trains are provided by the

network's response

. The in-degrees, the synaptic weights and the

shared-input statistics are thus exactly identical in the two scenarios. In

the feedback case (A), local presynaptic spike-trains are provided by the

network's response  , i.e. the pre- (C) and postsynaptic spike-train

ensembles (E) are identical. In the feedforward scenario (B), the local

presynaptic spike-train population is replaced by an ensemble of

, i.e. the pre- (C) and postsynaptic spike-train

ensembles (E) are identical. In the feedforward scenario (B), the local

presynaptic spike-train population is replaced by an ensemble of

independent

realizations

independent

realizations  of a Poisson

point process (D). Its rate is identical to the time- and

population-averaged firing rate in the feedback case. See Table 1 and Table 2 for details on

network models and parameters.

of a Poisson

point process (D). Its rate is identical to the time- and

population-averaged firing rate in the feedback case. See Table 1 and Table 2 for details on

network models and parameters.

Suppression of population-rate fluctuations in LIF networks

To illustrate the effect of shared input and its suppression by the recurrent

dynamics, we compare the spike response  of a recurrent random network (feedback scenario; Fig. 1 A,C,E) of

of a recurrent random network (feedback scenario; Fig. 1 A,C,E) of

LIF neurons to the

case where the feedback is cut and replaced by a spike-train ensemble

LIF neurons to the

case where the feedback is cut and replaced by a spike-train ensemble

, modeled by

, modeled by

independent

realizations of a stationary Poisson point process (feedforward

scenario; Fig. 1

B,D,F). The rate of this Poisson process is identical to the time and

population averaged firing rate in the intact recurrent system. In both the

feedback and the feedforward case, the (local) presynaptic spike trains are fed

to the postsynaptic population according to the same connectivity matrix

independent

realizations of a stationary Poisson point process (feedforward

scenario; Fig. 1

B,D,F). The rate of this Poisson process is identical to the time and

population averaged firing rate in the intact recurrent system. In both the

feedback and the feedforward case, the (local) presynaptic spike trains are fed

to the postsynaptic population according to the same connectivity matrix

. Therefore, not

only the in-degrees and the synaptic weights but also the shared-input

statistics are exactly identical.

. Therefore, not

only the in-degrees and the synaptic weights but also the shared-input

statistics are exactly identical.

For realistic size  and connectivity

and connectivity

, asynchronous

states of random neural networks [12], [31] exhibit spike-train

correlations which are small but not zero (compare raster displays in Fig. 1 C and D; see also [15]). Although

the presynaptic spike trains are, by construction, independent in the

feedforward case (Fig. 1 D),

the resulting response correlations, and, hence, the population-rate

fluctuations, are substantially stronger than those observed in the feedback

scenario (compare Fig. 1 F and

E). In other words: A theory which is exclusively based on the amount

of shared input but neglects the details of the presynaptic spike-train

statistics can significantly overestimate correlations and population-rate

fluctuations in recurrent neural networks.

, asynchronous

states of random neural networks [12], [31] exhibit spike-train

correlations which are small but not zero (compare raster displays in Fig. 1 C and D; see also [15]). Although

the presynaptic spike trains are, by construction, independent in the

feedforward case (Fig. 1 D),

the resulting response correlations, and, hence, the population-rate

fluctuations, are substantially stronger than those observed in the feedback

scenario (compare Fig. 1 F and

E). In other words: A theory which is exclusively based on the amount

of shared input but neglects the details of the presynaptic spike-train

statistics can significantly overestimate correlations and population-rate

fluctuations in recurrent neural networks.

The same effect can be observed in LIF networks with both purely inhibitory and

mixed excitatory-inhibitory coupling (Fig. 2). To demonstrate this quantitatively,

we focus on the fluctuations of the population averaged activity  . Its power-spectrum (or auto-correlation, in the time

domain)

. Its power-spectrum (or auto-correlation, in the time

domain)

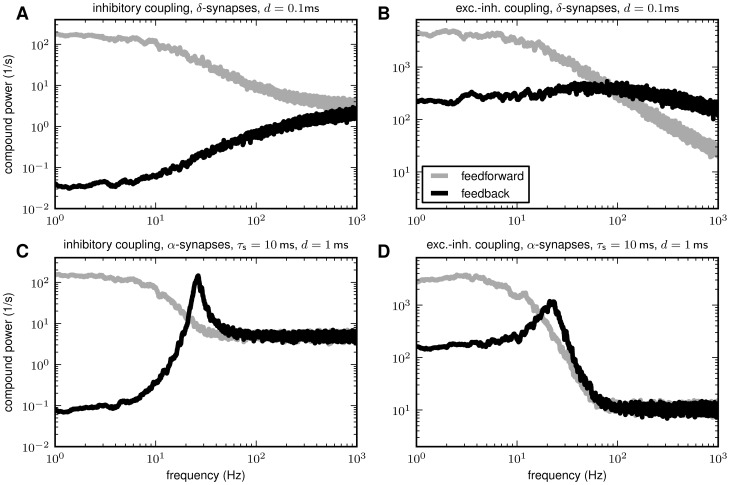

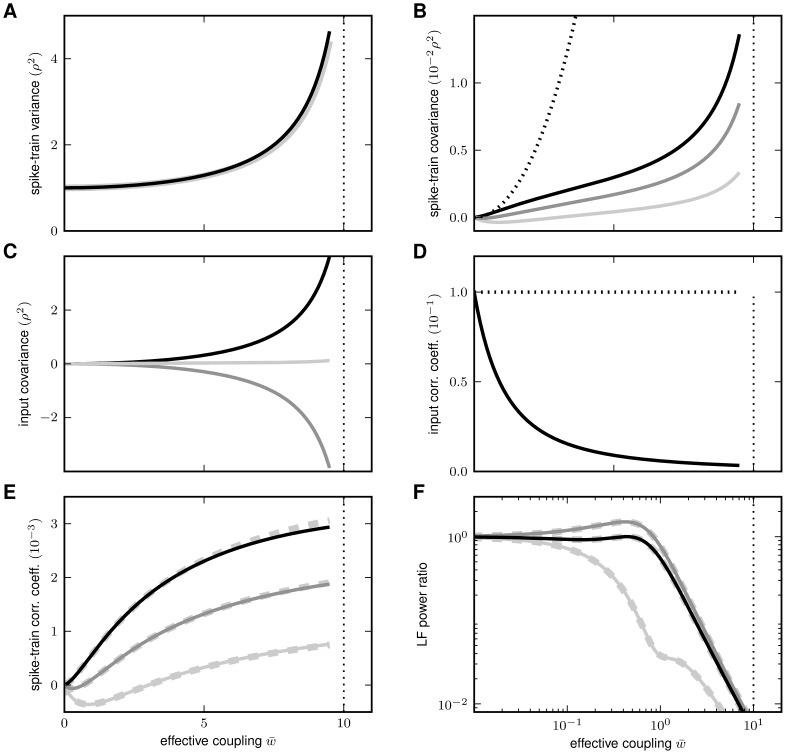

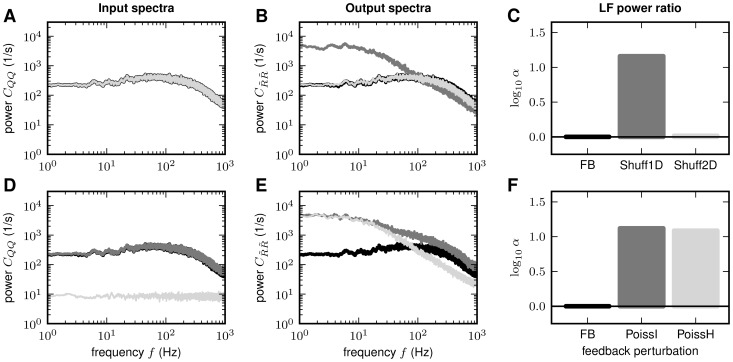

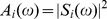

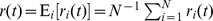

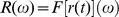

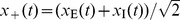

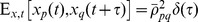

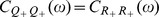

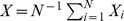

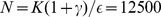

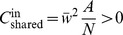

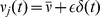

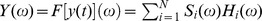

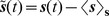

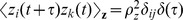

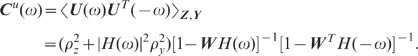

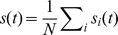

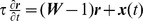

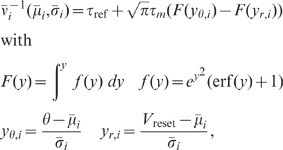

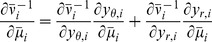

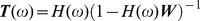

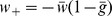

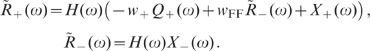

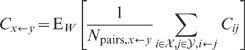

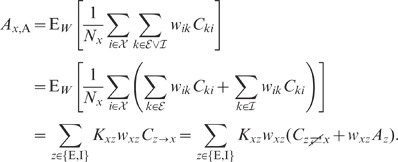

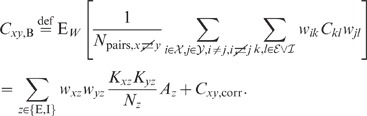

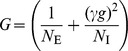

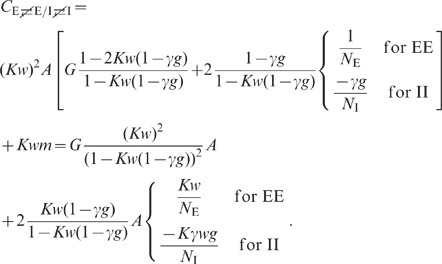

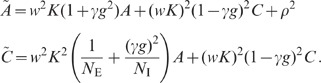

Figure 2. Suppression of low-frequency fluctuations in recurrent LIF networks

with purely inhibitory (A, C) and mixed excitatory-inhibitory coupling

(B, D) for instantaneous synapses with delay  (A, B) and

low-pass synapses with

(A, B) and

low-pass synapses with  (C, D).

(C, D).

Power-spectra  of

population rates

of

population rates  for the

feedback (black) and the feedforward case (gray; cf. Fig. 1). See Table 1 and Table 2 for details

on network models and parameters. In C and D, local synaptic inputs are

modeled as currents

for the

feedback (black) and the feedforward case (gray; cf. Fig. 1). See Table 1 and Table 2 for details

on network models and parameters. In C and D, local synaptic inputs are

modeled as currents  with

with  -function shaped kernel

-function shaped kernel  with time

constant

with time

constant  (

( denotes

Heaviside function). (Excitatory) Synaptic weights are set to

denotes

Heaviside function). (Excitatory) Synaptic weights are set to

(see Table 1 for

details). Simulation time

(see Table 1 for

details). Simulation time  . Single-trial spectra smoothed by moving average

(frame size

. Single-trial spectra smoothed by moving average

(frame size  ).

).

|

(1) |

is determined both by the power-spectra (auto-correlations)  of the individual spike trains and the cross-spectra

(cross-correlations)

of the individual spike trains and the cross-spectra

(cross-correlations)  (

( ) of pairs of spike trains (throughout the article, we

use capital letters to represent quantities in frequency [Fourier]

space;

) of pairs of spike trains (throughout the article, we

use capital letters to represent quantities in frequency [Fourier]

space;  represents the

Fourier transform of the spike train

represents the

Fourier transform of the spike train  ).

We observe that the spike-train power-spectra

).

We observe that the spike-train power-spectra  (and auto-correlations) are barely distinguishable in

the feedback and in the feedforward case (not shown here; the main features of

the spike-train auto-correlation are determined by the average single-neuron

firing rate and the refractory mechanism; both are identical in the feedback and

the feedforward scenario). The differences in the population-rate spectra

(and auto-correlations) are barely distinguishable in

the feedback and in the feedforward case (not shown here; the main features of

the spike-train auto-correlation are determined by the average single-neuron

firing rate and the refractory mechanism; both are identical in the feedback and

the feedforward scenario). The differences in the population-rate spectra

are therefore

essentially due to differences in the spike-train cross-spectra

are therefore

essentially due to differences in the spike-train cross-spectra  . In other words, the fluctuations in the population

activity serve as a measure of pairwise spike-train correlations [32]: small

(large) population averaged spike-train correlations are accompanied by small

(large) fluctuations in the population rate (see lower panels in Fig. 1 C–F). The

power-spectra

. In other words, the fluctuations in the population

activity serve as a measure of pairwise spike-train correlations [32]: small

(large) population averaged spike-train correlations are accompanied by small

(large) fluctuations in the population rate (see lower panels in Fig. 1 C–F). The

power-spectra  of the population

averaged activity reveal a feedback-induced suppression of the population-rate

variance at low frequencies up to several tens of Hertz. For the examples shown

in Fig. 2, this suppression

spans more than three orders of magnitude for the inhibitory and more than one

order of magnitude for the excitatory-inhibitory network.

of the population

averaged activity reveal a feedback-induced suppression of the population-rate

variance at low frequencies up to several tens of Hertz. For the examples shown

in Fig. 2, this suppression

spans more than three orders of magnitude for the inhibitory and more than one

order of magnitude for the excitatory-inhibitory network.

The suppression of low-frequency fluctuations does not critically depend on the

details of the network model. As shown in Fig. 2, it can, for example, be observed for

both networks with zero rise-time synapses ( -shaped synaptic currents) and short delays and for

networks with delayed low-pass filtering synapses (

-shaped synaptic currents) and short delays and for

networks with delayed low-pass filtering synapses ( -shaped synaptic currents). In the latter case, the

suppression of fluctuations is slightly more restricted to lower frequencies

(

-shaped synaptic currents). In the latter case, the

suppression of fluctuations is slightly more restricted to lower frequencies

( ). Here, the

fluctuation suppression is however similarly pronounced as in networks with

instantaneous synapses.

). Here, the

fluctuation suppression is however similarly pronounced as in networks with

instantaneous synapses.

In Fig. 2 C,D, the

power-spectra of the population activity converge to the mean firing rate at

high frequencies. This indicates that the spike trains are uncorrelated on short

time scales. For instantaneous  -synapses, neurons exhibit an immediate response to

excitatory input spikes [33], [34]. This fast response causes spike-train correlations

on short time scales. Hence, the compound power at high frequencies is

increased. In a recurrent system, this effect is amplified by reverberating

simultaneous excitatory spikes. Therefore, the high-frequency power of the

compound activity is larger in the feedback case (Fig. 2 B). Note that this high-frequency

effect is absent in networks with more realistic low-pass filtering synapses

(Fig. 2 C,D) and in

purely inhibitory networks (Fig. 2

A).

-synapses, neurons exhibit an immediate response to

excitatory input spikes [33], [34]. This fast response causes spike-train correlations

on short time scales. Hence, the compound power at high frequencies is

increased. In a recurrent system, this effect is amplified by reverberating

simultaneous excitatory spikes. Therefore, the high-frequency power of the

compound activity is larger in the feedback case (Fig. 2 B). Note that this high-frequency

effect is absent in networks with more realistic low-pass filtering synapses

(Fig. 2 C,D) and in

purely inhibitory networks (Fig. 2

A).

Synaptic delays and slow synapses can promote oscillatory modes in certain

frequency bands [12], [31], thereby leading to peaks in the population-rate

spectra in the feedback scenario which exceed the power in the feedforward case

(see peaks at  in Fig. 2 C,D). Note that, in the

feedforward case, the local input was replaced by a stationary Poisson process,

whereas in the recurrent network (feedback case) the presynaptic spike trains

exhibit oscillatory modes. By replacing the feedback by an inhomogeneous Poisson

process with a time dependent intensity which is identical to the population

rate in the recurrent network, we found that these oscillatory modes are neither

suppressed nor amplified by the recurrent dynamics, i.e. the peaks in the

resulting power-spectra have the same amplitude in the feedback and in the

feedforward case (data not shown here). At low frequencies, however, the results

are identical to those obtained by replacing the feedback by a homogeneous

Poisson process (i.e. to those shown in Fig. 2; see “

Results

: Effect of

feedback manipulations”). In the present study, we mainly focus

on these low-frequency effects.

in Fig. 2 C,D). Note that, in the

feedforward case, the local input was replaced by a stationary Poisson process,

whereas in the recurrent network (feedback case) the presynaptic spike trains

exhibit oscillatory modes. By replacing the feedback by an inhomogeneous Poisson

process with a time dependent intensity which is identical to the population

rate in the recurrent network, we found that these oscillatory modes are neither

suppressed nor amplified by the recurrent dynamics, i.e. the peaks in the

resulting power-spectra have the same amplitude in the feedback and in the

feedforward case (data not shown here). At low frequencies, however, the results

are identical to those obtained by replacing the feedback by a homogeneous

Poisson process (i.e. to those shown in Fig. 2; see “

Results

: Effect of

feedback manipulations”). In the present study, we mainly focus

on these low-frequency effects.

The observation that the suppression of low-frequency fluctuations is particularly pronounced in networks with purely inhibitory coupling indicates that inhibitory feedback may play a key role for the underlying mechanism. In the following subsection, we demonstrate by means of a one-dimensional linear population model that, indeed, negative feedback alone leads to an efficient fluctuation suppression.

Suppression of population-activity fluctuations by negative feedback

Average pairwise correlations can be extracted from the spectrum (1) of the

compound activity, provided the single spike-train statistics

(auto-correlations) is known (see previous section). As the single spike-train

statistics is identical in the feedback and in the feedforward scenario, the

mechanism underlying the decorrelation in recurrent networks can be understood

by studying the dynamics of the population averaged activity. In this and in the

next subsection, we consider the linearized dynamics of random networks composed

of homogeneous subpopulations of LIF neurons. The high-dimensional dynamics of

such systems can be reduced to low-dimensional models describing the dynamics of

the compound activity (for details, see “

Methods

: Linearized network

model”). Note that this reduction is exact for networks with

homogeneous out-degree (number of outgoing connections). For the networks

studied here (random networks with homogeneous in-degree), it serves as a

sufficient approximation (in a network of size  where each connection is randomly and independently

realized with probability

where each connection is randomly and independently

realized with probability  [Erdös-Rényi graph], the [binomial] in- and

out-degree distributions become very narrow for large

[Erdös-Rényi graph], the [binomial] in- and

out-degree distributions become very narrow for large  [relative to the mean in/out-degree]; both in-

and out-degree are therefore approximately constant across the population of

neurons). In this subsection, we first study networks with purely inhibitory

coupling. In “

Results

: Population-activity fluctuations in

excitatory-inhibitory networks”, we investigate the effect of

mixed excitatory-inhibitory connectivity.

[relative to the mean in/out-degree]; both in-

and out-degree are therefore approximately constant across the population of

neurons). In this subsection, we first study networks with purely inhibitory

coupling. In “

Results

: Population-activity fluctuations in

excitatory-inhibitory networks”, we investigate the effect of

mixed excitatory-inhibitory connectivity.

Consider a random network of  identical neurons with connection probability

identical neurons with connection probability  . Each neuron

. Each neuron  receives

receives  randomly chosen

inputs from the local network with synaptic weights

randomly chosen

inputs from the local network with synaptic weights  . In addition, the neurons are driven by external

uncorrelated Gaussian white noise

. In addition, the neurons are driven by external

uncorrelated Gaussian white noise  with amplitude

with amplitude  , i.e.

, i.e.

and

and

. For small input

fluctuations, the network dynamics can be linearized. This linearization is

based on the averaged response of a single neuron to an incoming spike and

describes the activity of an individual neuron

. For small input

fluctuations, the network dynamics can be linearized. This linearization is

based on the averaged response of a single neuron to an incoming spike and

describes the activity of an individual neuron  by an abstract fluctuating quantity

by an abstract fluctuating quantity  which is defined such that within the linear

approximation its auto- and cross-correlations fulfill the same linearized

equation as the spiking model in the low-frequency limit. Consequently, also the

low-frequency fluctuations of the population spike rate are captured correctly

by the reduced model up to linear order. This approach is equivalent to the

treatment of finite-size fluctuations in spiking networks (see, e.g., [31]). For

details, see “

Methods

: Linearized network

model”. For large

which is defined such that within the linear

approximation its auto- and cross-correlations fulfill the same linearized

equation as the spiking model in the low-frequency limit. Consequently, also the

low-frequency fluctuations of the population spike rate are captured correctly

by the reduced model up to linear order. This approach is equivalent to the

treatment of finite-size fluctuations in spiking networks (see, e.g., [31]). For

details, see “

Methods

: Linearized network

model”. For large  ,

the population averaged activity

,

the population averaged activity  can hence be described by a one-dimensional linear system

can hence be described by a one-dimensional linear system

| (2) |

with linear kernel  , effective

coupling strength

, effective

coupling strength  and the population

averaged noise

and the population

averaged noise  (see

“

Methods

: Linearized network model”

and Fig. 3 B). The coupling

strength

(see

“

Methods

: Linearized network model”

and Fig. 3 B). The coupling

strength  represents the

integrated linear response of the neuron population to a small perturbation in

the input rate of a single presynaptic neuron. For a population of LIF neurons,

its relation to the synaptic weight

represents the

integrated linear response of the neuron population to a small perturbation in

the input rate of a single presynaptic neuron. For a population of LIF neurons,

its relation to the synaptic weight  (PSP amplitude) is derived in “

Methods

: Linearized network

model” and “

Methods

: Response kernel of the LIF

model”. The normalized kernel

(PSP amplitude) is derived in “

Methods

: Linearized network

model” and “

Methods

: Response kernel of the LIF

model”. The normalized kernel  (with

(with  )

captures the time course of the linear response. It is determined by the

single-neuron properties (e.g. the spike-initiation dynamics [35],

[36]),

the properties of the synapses (e.g. synaptic weights and time constants [37], [38]) and the

properties of the input (e.g. excitatory vs. inhibitory input [39]). For

many real and model neurons, the linear population-rate response exhibits

low-pass characteristics [13], [34]–[46]. For illustration (Fig. 3), we consider a

1st-order low-pass filter, i.e. an exponential impulse response

)

captures the time course of the linear response. It is determined by the

single-neuron properties (e.g. the spike-initiation dynamics [35],

[36]),

the properties of the synapses (e.g. synaptic weights and time constants [37], [38]) and the

properties of the input (e.g. excitatory vs. inhibitory input [39]). For

many real and model neurons, the linear population-rate response exhibits

low-pass characteristics [13], [34]–[46]. For illustration (Fig. 3), we consider a

1st-order low-pass filter, i.e. an exponential impulse response  with time constant

with time constant  (cutoff frequency

(cutoff frequency  ;

see Fig. 3 A, light gray

curve in E). The results of our analysis are however independent of the choice

of the kernel

;

see Fig. 3 A, light gray

curve in E). The results of our analysis are however independent of the choice

of the kernel  . The

auto-correlation

. The

auto-correlation  of the external

noise is parametrized by the effective noise amplitude

of the external

noise is parametrized by the effective noise amplitude  .

.

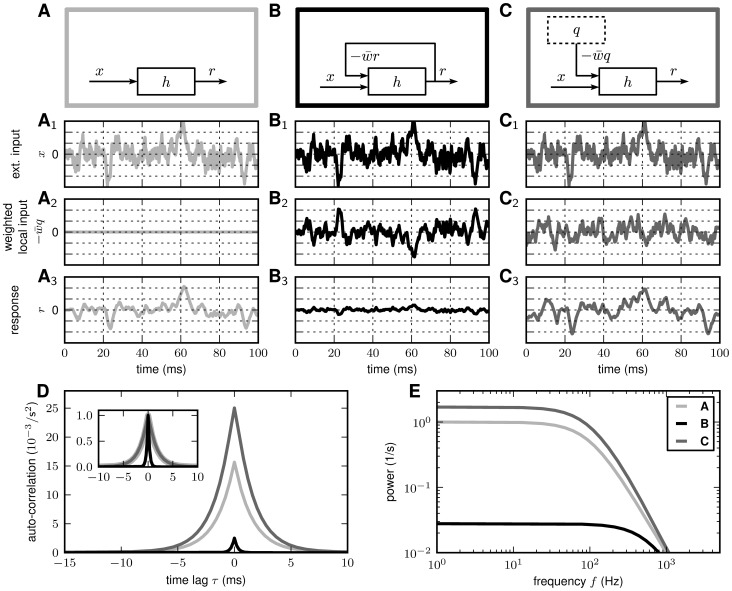

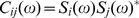

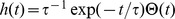

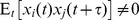

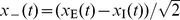

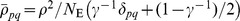

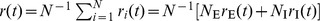

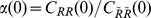

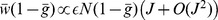

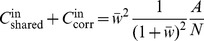

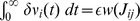

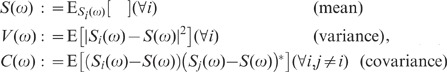

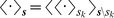

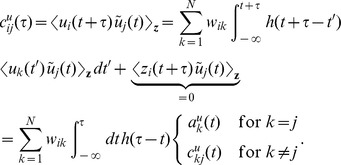

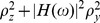

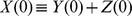

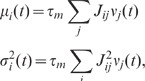

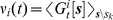

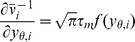

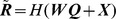

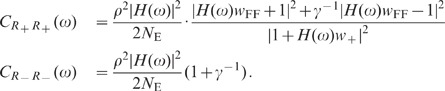

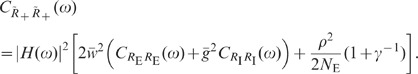

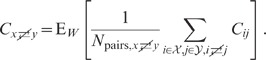

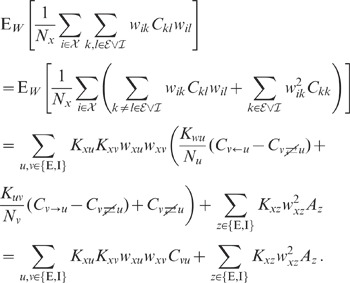

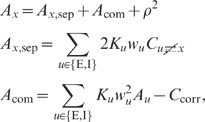

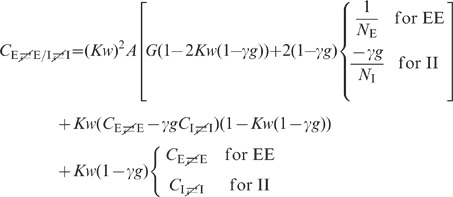

Figure 3. Partial canceling of fluctuations in a linear system by inhibitory feedback.

Response  of a

linear system with impulse response

of a

linear system with impulse response  (1st-order

low-pass, cutoff frequency

(1st-order

low-pass, cutoff frequency  ) to Gaussian white noise input

) to Gaussian white noise input  with

amplitude

with

amplitude  for three

local-input scenarios. A (light gray): No feedback (local

input

for three

local-input scenarios. A (light gray): No feedback (local

input  ).

B (black): Negative feedback (

).

B (black): Negative feedback ( ) with

strength

) with

strength  . The

fluctuations of the weighted local input

. The

fluctuations of the weighted local input  (B

(B ) are

anticorrelated to the external drive

) are

anticorrelated to the external drive  (B

(B ).

C (dark gray): Feedback in B is replaced by

uncorrelated feedforward input

).

C (dark gray): Feedback in B is replaced by

uncorrelated feedforward input  with the same auto-statistics as the response

with the same auto-statistics as the response

in

B

in

B . The local

input

. The local

input  is

constructed by assigning a random phase

is

constructed by assigning a random phase  to each

Fourier component

to each

Fourier component  of the

response in B

of the

response in B .

Fluctuations in C

.

Fluctuations in C and

C

and

C are

uncorrelated. A, B, C: Network

sketches. A

are

uncorrelated. A, B, C: Network

sketches. A

, B

, B

,

C

,

C

: External

input

: External

input  .

A

.

A

,

B

,

B

,

C

,

C

: Weighted

local input

: Weighted

local input  .

A

.

A

,

B

,

B

,

C

,

C

: Responses

: Responses

.

D, E: Response auto-correlation functions

(D) and power-spectra (E) for the three cases shown in A,B,C (same gray

coding as in A,B,C; inset in D: normalized auto-correlations).

.

D, E: Response auto-correlation functions

(D) and power-spectra (E) for the three cases shown in A,B,C (same gray

coding as in A,B,C; inset in D: normalized auto-correlations).

Given the simplified description (2), the suppression of response fluctuations by

negative feedback can be understood intuitively: Consider first the case where

the neurons in the local network are unconnected (Fig. 3 A; no feedback,  ). Here, the response

). Here, the response  (Fig. 3

A

(Fig. 3

A

) is simply a

low-pass filtered version of the external input

) is simply a

low-pass filtered version of the external input  (Fig. 3

A

(Fig. 3

A

), resulting in an

exponentially decaying response auto-correlation (Fig. 3 D; light gray curve) and a drop in the

response power-spectrum at the cutoff frequency

), resulting in an

exponentially decaying response auto-correlation (Fig. 3 D; light gray curve) and a drop in the

response power-spectrum at the cutoff frequency  (Fig. 3

E). At low frequencies,

(Fig. 3

E). At low frequencies,  and

and  are in phase; they

are correlated. In the presence of negative feedback (Fig. 3 B), the local input

are in phase; they

are correlated. In the presence of negative feedback (Fig. 3 B), the local input  (Fig. 3

B

(Fig. 3

B

) and the

low-frequency components of the external input

) and the

low-frequency components of the external input  (Fig. 3

B

(Fig. 3

B

) are

anticorrelated. They partly cancel out, thereby reducing the response

fluctuations

) are

anticorrelated. They partly cancel out, thereby reducing the response

fluctuations  (Fig. 3 B

(Fig. 3 B

). The auto-correlation function and the power-spectrum

are suppressed (Fig. 3 D,E;

black curves). Due to the low-pass characteristics of the system, mainly the

low-frequency components of the external drive

). The auto-correlation function and the power-spectrum

are suppressed (Fig. 3 D,E;

black curves). Due to the low-pass characteristics of the system, mainly the

low-frequency components of the external drive  are transferred to the output side and, in turn, become

available for the feedback signal. Therefore, the canceling of input

fluctuations and the resulting suppression of response fluctuations are most

efficient at low frequencies. Consequently, the auto-correlation function is

sharpened (see inset in Fig. 3

D). The cutoff frequency of the system is increased (Fig. 3 E; black curve). This

effect of negative feedback is very general and well known in the engineering

literature. It is employed in the design of technical devices, like, e.g.,

amplifiers [47]. As the zero-frequency power is identical to the

integrated auto-correlation function, the suppression of low-frequency

fluctuations is accompanied by a reduction in the auto-correlation area (Fig. 3 D; black curve). Note

that the suppression of fluctuations in the feedback case is not merely a result

of the additional inhibitory noise source provided by the local input, but

follows from the precise temporal alignment of the local and the external input.

To illustrate this, let's consider the case where the feedback channel is

replaced by a feedforward input

are transferred to the output side and, in turn, become

available for the feedback signal. Therefore, the canceling of input

fluctuations and the resulting suppression of response fluctuations are most

efficient at low frequencies. Consequently, the auto-correlation function is

sharpened (see inset in Fig. 3

D). The cutoff frequency of the system is increased (Fig. 3 E; black curve). This

effect of negative feedback is very general and well known in the engineering

literature. It is employed in the design of technical devices, like, e.g.,

amplifiers [47]. As the zero-frequency power is identical to the

integrated auto-correlation function, the suppression of low-frequency

fluctuations is accompanied by a reduction in the auto-correlation area (Fig. 3 D; black curve). Note

that the suppression of fluctuations in the feedback case is not merely a result

of the additional inhibitory noise source provided by the local input, but

follows from the precise temporal alignment of the local and the external input.

To illustrate this, let's consider the case where the feedback channel is

replaced by a feedforward input  (Fig. 3 C) which has the

same auto-statistics as the response

(Fig. 3 C) which has the

same auto-statistics as the response  in the feedback case (Fig. 3

B

in the feedback case (Fig. 3

B

) but is

uncorrelated to the external drive

) but is

uncorrelated to the external drive  .

In this case, external input fluctuations (Fig. 3 C

.

In this case, external input fluctuations (Fig. 3 C

) are not canceled by the local input

) are not canceled by the local input  (Fig. 3

C

(Fig. 3

C

). Instead, the

local feedforward input acts as an additional noise source which leads to an

increase in the response fluctuations (Fig. 3 C

). Instead, the

local feedforward input acts as an additional noise source which leads to an

increase in the response fluctuations (Fig. 3 C

). The response auto-correlation and power-spectrum

(Fig. 3 D,E; dark gray

curves) are increased. Compared to the unconnected case (Fig. 3 E; light gray curve), the cutoff

frequency remains unchanged.

). The response auto-correlation and power-spectrum

(Fig. 3 D,E; dark gray

curves) are increased. Compared to the unconnected case (Fig. 3 E; light gray curve), the cutoff

frequency remains unchanged.

The feedback induced suppression of response fluctuations can be quantified by comparing the response power-spectra

| (3) |

and

| (4) |

in the feedback (Fig. 3 B)

and the feedforward case (Fig. 3

C), respectively (see “

Methods

: Population-activity spectrum of

the linear inhibitory network”). Here,  and

and  denote the Fourier transforms of the response fluctuations in the feedback and

the feedforward scenario, respectively,

denote the Fourier transforms of the response fluctuations in the feedback and

the feedforward scenario, respectively,  the transfer function (Fourier transform of the filter kernel

the transfer function (Fourier transform of the filter kernel  ) of the neuron population, and

) of the neuron population, and  the average across noise realizations. We use the power

ratio

the average across noise realizations. We use the power

ratio

| (5) |

as a measure of the relative fluctuation suppression caused by feedback. For low

frequencies ( ) and strong

effective coupling

) and strong

effective coupling  , the power ratio

(5) decays as

, the power ratio

(5) decays as  (see Fig. 4 A): the suppression of

population-rate fluctuations is promoted by strong negative feedback. In line

with the observations in “

Results

: Suppression of population-rate

fluctuations in LIF networks”, this suppression is restricted

to low frequencies; for high frequencies (

(see Fig. 4 A): the suppression of

population-rate fluctuations is promoted by strong negative feedback. In line

with the observations in “

Results

: Suppression of population-rate

fluctuations in LIF networks”, this suppression is restricted

to low frequencies; for high frequencies ( ,

i.e.

,

i.e.  ), the power ratio

), the power ratio

approaches

approaches

. Note that the

power ratio (5) is independent of the amplitude

. Note that the

power ratio (5) is independent of the amplitude  of the population averaged external input

of the population averaged external input

. Therefore, even

if we dropped the assumption of the external inputs

. Therefore, even

if we dropped the assumption of the external inputs  being uncorrelated, i.e. if

being uncorrelated, i.e. if  for

for  ,

the power ratio (5) remained the same. For correlated external input, the power

,

the power ratio (5) remained the same. For correlated external input, the power

of the population

average

of the population

average  is different from

is different from

. The suppression

factor

. The suppression

factor  , however, is not

affected by this. Moreover, it is straightforward to show that the power ratio

(5) is, in fact, independent of the shape of the external-noise spectrum

, however, is not

affected by this. Moreover, it is straightforward to show that the power ratio

(5) is, in fact, independent of the shape of the external-noise spectrum

. The same result

(5) is obtained for any type of external input (e.g. colored noise or

oscillating inputs).

. The same result

(5) is obtained for any type of external input (e.g. colored noise or

oscillating inputs).

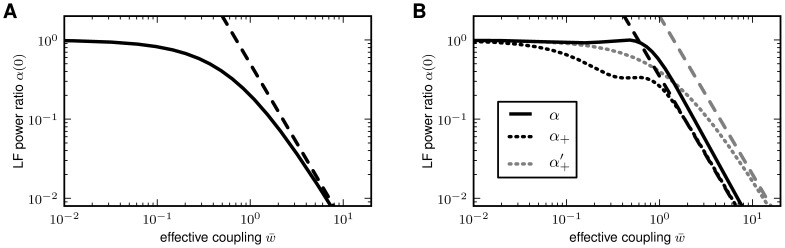

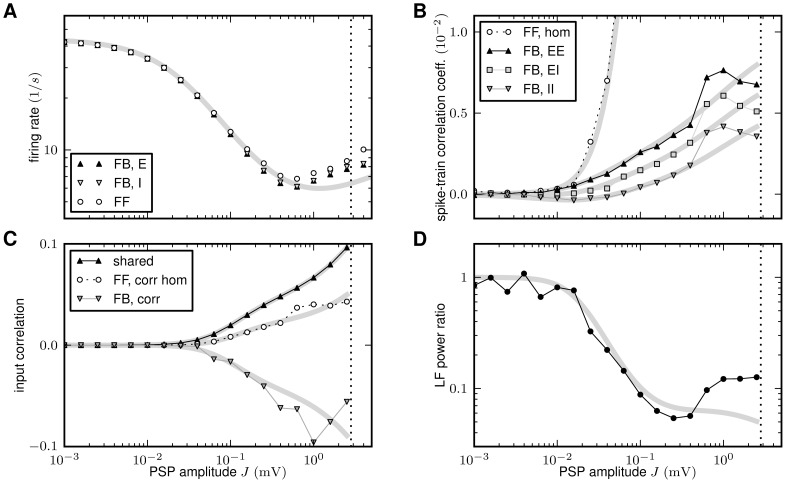

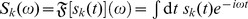

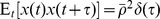

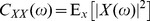

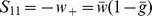

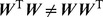

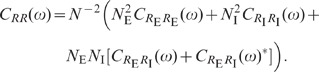

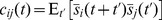

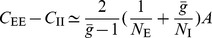

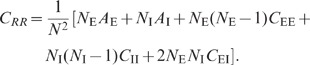

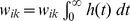

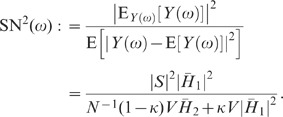

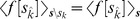

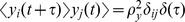

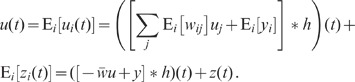

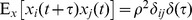

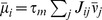

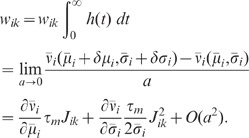

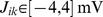

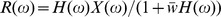

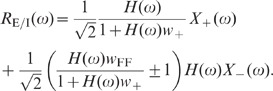

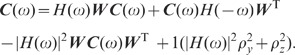

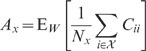

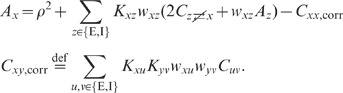

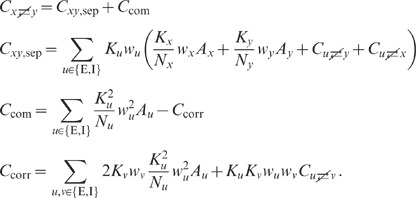

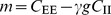

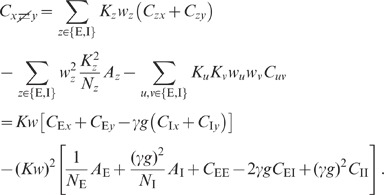

Figure 4. Suppression of low-frequency (LF) population-rate fluctuations in linearized homogeneous random networks with purely inhibitory (A) and mixed excitatory-inhibitory coupling (B).

Dependence of the zero-frequency power ratio  on the

effective coupling strength

on the

effective coupling strength  (solid curves: full solutions; dashed lines:

strong-coupling approximations). The power ratio

(solid curves: full solutions; dashed lines:

strong-coupling approximations). The power ratio  represents

the ratio between the low-frequency population-rate power in the

recurrent networks (A: Fig. 3 B; B: Fig. 5 A,B) and in

networks where the feedback channels are replaced by uncorrelated

feedforward input (A: Fig. 3 C; B, black:

Fig. 5 C,D;

B, gray: Fig. 5 D′). Dotted curves in B depict

power ratio of the sum modes

represents

the ratio between the low-frequency population-rate power in the

recurrent networks (A: Fig. 3 B; B: Fig. 5 A,B) and in

networks where the feedback channels are replaced by uncorrelated

feedforward input (A: Fig. 3 C; B, black:

Fig. 5 C,D;

B, gray: Fig. 5 D′). Dotted curves in B depict

power ratio of the sum modes  and

and  (see text). B: Balance factor

(see text). B: Balance factor  .

.

For low frequencies, the transfer function  approaches unity (

approaches unity ( ); the exact shape

of the kernel

); the exact shape

of the kernel  becomes

irrelevant. In particular, the cutoff frequency (or time constant) of a low-pass

kernel has no effect on the zero-frequency power (integral correlation) and the

zero-frequency power ratio

becomes

irrelevant. In particular, the cutoff frequency (or time constant) of a low-pass

kernel has no effect on the zero-frequency power (integral correlation) and the

zero-frequency power ratio  (Fig. 4). Therefore, the

suppression of low-frequency fluctuations does not critically depend on the

exact choice of the neuron, synapse or input model. The same reasoning applies

to synaptic delays: Replacing the kernel

(Fig. 4). Therefore, the

suppression of low-frequency fluctuations does not critically depend on the

exact choice of the neuron, synapse or input model. The same reasoning applies

to synaptic delays: Replacing the kernel  by a delayed kernel

by a delayed kernel  leads to an

additional phase factor

leads to an

additional phase factor  in the transfer

function

in the transfer

function  . For sufficiently

small frequencies (long time scales), this factor can be neglected

(

. For sufficiently

small frequencies (long time scales), this factor can be neglected

( ).

).

For networks with purely inhibitory feedback, the absolute power (3) of the

population rate decreases monotonously with increasing coupling strength

. As we will

demonstrate in “

Results

: Population-activity fluctuations in

excitatory-inhibitory networks” and “

Results

: Population

averaged correlations in cortical networks”, this is

qualitatively different in networks with mixed excitatory and inhibitory

coupling

. As we will

demonstrate in “

Results

: Population-activity fluctuations in

excitatory-inhibitory networks” and “

Results

: Population

averaged correlations in cortical networks”, this is

qualitatively different in networks with mixed excitatory and inhibitory

coupling  and

and

, respectively:

here, the fluctuations of the compound activity increase with

, respectively:

here, the fluctuations of the compound activity increase with  . The power ratio

. The power ratio  ,

however, still decreases with

,

however, still decreases with  .

.

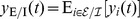

Population-activity fluctuations in excitatory-inhibitory networks

In the foregoing subsection, we have shown that negative feedback alone can

efficiently suppress population-rate fluctuations and, hence, spike-train

correlations. So far, it is unclear whether the same reasoning applies to

networks with mixed excitatory and inhibitory coupling. To clarify this, we now

consider a random network composed of a homogeneous excitatory and inhibitory

subpopulation  and

and

of size

of size

and

and

, respectively.

Each neuron receives

, respectively.

Each neuron receives  excitatory and

excitatory and

inhibitory inputs

from

inhibitory inputs

from  and

and

with synaptic

weights

with synaptic

weights  and

and

, respectively. In

addition, the neurons are driven by external Gaussian white noise. As

demonstrated in “

Methods

: Linearized network

model”, linearization and averaging across subpopulations leads

to a two-dimensional system

, respectively. In

addition, the neurons are driven by external Gaussian white noise. As

demonstrated in “

Methods

: Linearized network

model”, linearization and averaging across subpopulations leads

to a two-dimensional system

| (6) |

describing the linearized dynamics of the subpopulation averaged activity

. Here,

. Here,

denotes the

subpopulation averaged external uncorrelated white-noise input with correlation

functions

denotes the

subpopulation averaged external uncorrelated white-noise input with correlation

functions  (

( ,

,  ), and

), and

a normalized

linear kernel with

a normalized

linear kernel with  . The excitatory

and inhibitory subpopulations are coupled through an effective connectivity

matrix

. The excitatory

and inhibitory subpopulations are coupled through an effective connectivity

matrix

| (7) |

with effective weight  and balance

parameter

and balance

parameter  .

.

The two-dimensional system (6)/(7) represents a recurrent system with both positive and negative feedback connections (Fig. 5 A). By introducing new coordinates

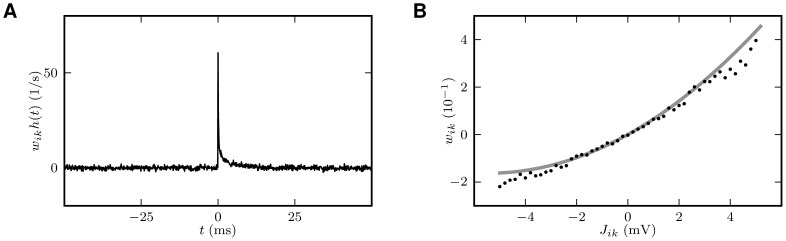

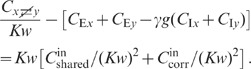

Figure 5. Sketch of the 2D (excitatory-inhibitory) model for the feedback (A,B) and the feedforward scenario (C,D) in normal (A,C) and Schur-basis representation (B,D).

A: Original 2D recurrent system. B: Schur-basis

representation of the system shown in A. C: Feedforward

scenario: Excitatory and inhibitory feedback connections of the original

network (A) are replaced by feedforward input from populations with

rates  ,

,

,

respectively. D: Schur-basis representation of the system

shown in C. D′: Alternative feedforward scenario:

Here, the feedforward channel (weight

,

respectively. D: Schur-basis representation of the system

shown in C. D′: Alternative feedforward scenario:

Here, the feedforward channel (weight  ) of the

original system in Schur basis (B) remains intact. Only the inhibitory

feedback (weight

) of the

original system in Schur basis (B) remains intact. Only the inhibitory

feedback (weight  ) is

replaced by feedforward input

) is

replaced by feedforward input  .

.

| (8) |

and  ,

,  , we obtain an equivalent representation of (6)/(7),

, we obtain an equivalent representation of (6)/(7),

| (9) |

describing the dynamics of the sum and difference activity  and

and  ,

respectively, i.e. the in- and anti-phase components of the excitatory and

inhibitory subpopulations (see [48]–[50]). The new coupling

matrix

,

respectively, i.e. the in- and anti-phase components of the excitatory and

inhibitory subpopulations (see [48]–[50]). The new coupling

matrix

| (10) |

reveals that the sum mode  is subject to

self-feedback (

is subject to

self-feedback ( ) and receives

feedforward input from the difference mode

) and receives

feedforward input from the difference mode  (

( ). All remaining

connections are absent (

). All remaining

connections are absent ( ) in the new

representation (8) (see Fig. 5

B). The correlation functions of the external noise in the new

coordinates are given by

) in the new

representation (8) (see Fig. 5

B). The correlation functions of the external noise in the new

coordinates are given by  with

with

(

( ).

).

The feedforward coupling is positive ( ):

an excitation surplus (

):

an excitation surplus ( ) will excite all

neurons in the network, an excitation deficit (

) will excite all

neurons in the network, an excitation deficit ( ) will lead to global inhibition. In inhibition dominated

regimes with

) will lead to global inhibition. In inhibition dominated

regimes with  , the self-feedback

of the sum activity

, the self-feedback

of the sum activity  is effectively

negative (

is effectively

negative ( ). The dynamics of

the sum rate in inhibition-dominated excitatory-inhibitory networks is therefore

qualitatively similar to the dynamics in purely inhibitory networks

(“

Results

: Suppression of population-activity

fluctuations by negative feedback”). As shown below, the

negative feedback loop exposed by the transform (8) leads to an efficient

relative suppression of population-rate fluctuations (if compared to the

feedforward case).

). The dynamics of

the sum rate in inhibition-dominated excitatory-inhibitory networks is therefore

qualitatively similar to the dynamics in purely inhibitory networks

(“

Results

: Suppression of population-activity

fluctuations by negative feedback”). As shown below, the

negative feedback loop exposed by the transform (8) leads to an efficient

relative suppression of population-rate fluctuations (if compared to the

feedforward case).

Mathematically, the coordinate transform (8) corresponds to a Schur

decomposition of the dynamics: Any recurrent system of type (6)

(with arbitrary coupling matrix  )

can be transformed to a system with a triangular coupling matrix (see, e.g.,

[50]). The

resulting coupling between the different Schur modes can be ordered so that

there are only connections from modes with lower index to modes with the same or

larger index. In this sense, the resulting system has been termed

‘feedforward’ [50]. The original coupling matrix

)

can be transformed to a system with a triangular coupling matrix (see, e.g.,

[50]). The

resulting coupling between the different Schur modes can be ordered so that

there are only connections from modes with lower index to modes with the same or

larger index. In this sense, the resulting system has been termed

‘feedforward’ [50]. The original coupling matrix  is typically not normal, i.e.

is typically not normal, i.e.  . Its eigenvectors do not form an orthogonal basis. By

performing a Gram-Schmidt orthonormalization of the eigenvectors, however, one

can obtain a (normalized) orthogonal basis, a Schur basis. Our new coordinates

(8) correspond to the amplitudes (the time evolution) of two orthogonal Schur

modes.

. Its eigenvectors do not form an orthogonal basis. By

performing a Gram-Schmidt orthonormalization of the eigenvectors, however, one

can obtain a (normalized) orthogonal basis, a Schur basis. Our new coordinates

(8) correspond to the amplitudes (the time evolution) of two orthogonal Schur

modes.

The spectra  ,

,  ,

,  and

and

of the

subpopulation averaged rates

of the

subpopulation averaged rates  ,

,

and the sum mode

and the sum mode

, respectively, are

derived in “

Methods

: Population-activity spectra of the

linear excitatory-inhibitory network”. In contrast to the

purely inhibitory network (see “

Results

: Suppression of population-activity

fluctuations by negative feedback”), the population-rate

fluctuations of the excitatory-inhibitory network increase monotonously with

increasing coupling strength

, respectively, are

derived in “

Methods

: Population-activity spectra of the

linear excitatory-inhibitory network”. In contrast to the

purely inhibitory network (see “

Results

: Suppression of population-activity

fluctuations by negative feedback”), the population-rate

fluctuations of the excitatory-inhibitory network increase monotonously with

increasing coupling strength  .

For strong coupling,

.

For strong coupling,  approaches

approaches

| (11) |

from below with  . Close to the

critical point (

. Close to the

critical point ( ), the rate

fluctuations become very large; (11) diverges. Increasing the amount of

inhibition by increasing

), the rate

fluctuations become very large; (11) diverges. Increasing the amount of

inhibition by increasing  , however, leads to

a suppression of these fluctuations. In the limit

, however, leads to

a suppression of these fluctuations. In the limit  ,

,  and (11) approach

the spectrum

and (11) approach

the spectrum  of the unconnected

network. For strong coupling (

of the unconnected

network. For strong coupling ( ),

the ratio

),

the ratio  approaches

approaches

: the fluctuations

of the population averaged excitatory firing rate exceed those of the inhibitory

population by a factor

: the fluctuations

of the population averaged excitatory firing rate exceed those of the inhibitory

population by a factor  (independently of

(independently of

and

and

).

).

Similarly to the strategy we followed in the previous subsections, we will now

compare the population-rate fluctuations of the feedback system (6), or

equivalently (9), to the case where the feedback channels are replaced by

feedforward input with identical auto-statistics. A straight-forward

implementation of this is illustrated in Fig. 5 C: Here, the excitatory and inhibitory

feedback channels  and

and

are replaced by

uncorrelated feedforward inputs

are replaced by

uncorrelated feedforward inputs  and

and  , respectively. The

Schur representation of this scenario is depicted in Fig. 5 D. According to (6), the Fourier

transforms of the response fluctuations of this system read

, respectively. The

Schur representation of this scenario is depicted in Fig. 5 D. According to (6), the Fourier

transforms of the response fluctuations of this system read

|

(12) |

With  , and using

, and using

,

,  ,

,  , we can express

the spectrum

, we can express

the spectrum  of the sum

activity in the feedforward case in terms of the spectra

of the sum

activity in the feedforward case in terms of the spectra  and

and  of the feedback system (see eq. (55)). For strong coupling (

of the feedback system (see eq. (55)). For strong coupling ( ), the zero-frequency component (

), the zero-frequency component ( ) becomes

) becomes

| (13) |

Thus, for strong coupling, the zero-frequency power ratio

| (14) |

reveals a relative suppression of the population-rate fluctuations in the

feedback system which is proportional to  (see Fig. 4 B; black dashed

line). The power ratio

(see Fig. 4 B; black dashed

line). The power ratio  for arbitrary

weights

for arbitrary

weights  is depicted in

Fig. 4 B (black dotted

curve). For a network at the transition point

is depicted in

Fig. 4 B (black dotted

curve). For a network at the transition point  , (14) equals

, (14) equals  .

Increasing the level of inhibition by increasing

.

Increasing the level of inhibition by increasing  leads to a decrease in the power ratio: in the limit

leads to a decrease in the power ratio: in the limit

, (14) approaches

, (14) approaches

monotonously.

monotonously.

Above, we suggested that the negative self-feedback of the sum mode

, weighted by

, weighted by

(Fig. 5 B), is responsible for

the fluctuation suppression in the recurrent excitatory-inhibitory system. Here,

we test this by considering the case where this feedback loop is opened and

replaced by uncorrelated feedforward input

(Fig. 5 B), is responsible for

the fluctuation suppression in the recurrent excitatory-inhibitory system. Here,

we test this by considering the case where this feedback loop is opened and

replaced by uncorrelated feedforward input  , weighted by

, weighted by  ,

while the feedforward input from the difference mode

,

while the feedforward input from the difference mode  , weighted by

, weighted by  ,

is left intact (see Fig. 5

D′). As before, we assume that the auto-statistics of

,

is left intact (see Fig. 5

D′). As before, we assume that the auto-statistics of

is identical to

the auto-statistics of

is identical to

the auto-statistics of  as obtained in the

feedback case, i.e.

as obtained in the

feedback case, i.e.  . According to the

Schur representation of the population dynamics (9)/(10), the Fourier transform

of the sum mode of this modified system is given by

. According to the

Schur representation of the population dynamics (9)/(10), the Fourier transform

of the sum mode of this modified system is given by

| (15) |

With  given in (54) and

given in (54) and

, we obtain the

power ratio

, we obtain the

power ratio

| (16) |

Its zero-frequency component  is shown in Fig. 4 B (gray

dotted curve). For strong coupling, the power ratio decays as

is shown in Fig. 4 B (gray

dotted curve). For strong coupling, the power ratio decays as  (gray dashed line in Fig. 4 B). Thus, the (relative) power in the

recurrent system is reduced by strengthening the negative self-feedback loop,

i.e. by increasing

(gray dashed line in Fig. 4 B). Thus, the (relative) power in the

recurrent system is reduced by strengthening the negative self-feedback loop,

i.e. by increasing  .

.

So far, we have presented results for the subpopulation averaged firing rates

and

and

and the sum mode

and the sum mode

. The spectrum of

the compound rate

. The spectrum of

the compound rate  , i.e. the activity

averaged across the entire population, reads

, i.e. the activity

averaged across the entire population, reads

|

(17) |

In the feedforward scenario depicted in Fig. 5 C, the spectrum of the compound rate

(with

(with

) is given by

) is given by

| (18) |

For strong coupling, the corresponding low-frequency power ratio  (black solid curve in Fig. 4 B) exhibits qualitatively the same

decrease

(black solid curve in Fig. 4 B) exhibits qualitatively the same

decrease  as the sum

mode.

as the sum

mode.

To summarize the results of this subsection: the population dynamics of a

recurrent network with mixed excitatory and inhibitory coupling can be mapped to

a two-dimensional system describing the dynamics of the sum and the difference

of the excitatory and inhibitory subpopulation activities. This equivalent

representation uncovers that, in inhibition dominated networks ( ), the sum activity is subject to negative self-feedback.

Thus, the dynamics of the sum activity in excitatory-inhibitory networks is

qualitatively similar to the population dynamics of purely inhibitory networks

(see “

Results

: Suppression of population-activity

fluctuations by negative feedback”). Indeed, the comparison of

the compound power-spectra of the intact recurrent network and networks where

the feedback channels are replaced by feedforward input reveals that the

(effective) negative feedback in excitatory-inhibitory networks leads to an

efficient suppression of population-rate fluctuations.

), the sum activity is subject to negative self-feedback.

Thus, the dynamics of the sum activity in excitatory-inhibitory networks is

qualitatively similar to the population dynamics of purely inhibitory networks

(see “

Results

: Suppression of population-activity

fluctuations by negative feedback”). Indeed, the comparison of

the compound power-spectra of the intact recurrent network and networks where

the feedback channels are replaced by feedforward input reveals that the

(effective) negative feedback in excitatory-inhibitory networks leads to an

efficient suppression of population-rate fluctuations.

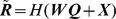

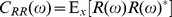

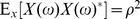

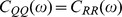

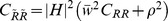

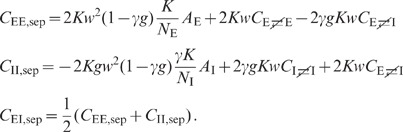

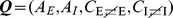

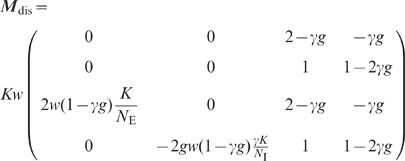

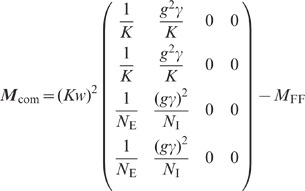

Population averaged correlations in cortical networks

The results presented in the previous subsections describe the fluctuations of

the compound activity. Pairwise correlations  between the (centralized) spike trains

between the (centralized) spike trains  are outside the scope of such a description. In this

subsection, we consider the same excitatory-inhibitory network as in

“

Results

: Population-activity fluctuations in

excitatory-inhibitory networks” and present a theory for the

population averaged spike-train cross-correlations. In general, this is a hard

problem. To understand the structure of cross-correlations, it is however

sufficient to derive a relationship between the cross- and auto-covariances in

the network, because the latter can, to good approximation, be understood in

mean-field theory. The integral of the auto-covariance function of spiking LIF

neurons can be calculated by Fokker-Planck formalism [12], [31], [51]. To determine the

relation between the cross-covariance and the auto-covariance, we replace the