Abstract

Introduction Sri Lanka has one of the highest suicide rates in the world, with recent protracted conflict and the tsunami aggravating mental health needs. This paper describes a project to establish a systematic “train the trainers” programme to integrate mental health into primary care in Sri Lanka's public health system and private sector.

Methods A 40 hour training programme was delivered to curriculum and teaching materials were adapted for Sri Lanka, and delivered to 45 psychiatrists, 110 medical officers of mental health and 95 registered medical practitioners, through five courses, each in a different region (Colombo, Kandy, Jaffna, Galle and Batticola). Participants were selected by the senior psychiatrist of each region, on the basis of ability to conduct subsequent roll out of the training. The course was very interactive, with discussions, role plays and small group work, as well as brief theory sessions.

Results Qualitative participant feedback was encouraging about the value of the course in improving patient assessments and treatments, and in providing a valuable package for roll out to others. Systematic improvement was achieved between pre- and post-test scores of participants at all training sites. The participants had not had prior experience in such interactive teaching methods, but were able to learn these new techniques relatively quickly.

Conclusions The programme has been conducted in collaboration with the Sri Lankan National Institute of Mental Health and the Ministry of Health, and this partnership has helped to ensure that the training is tailored to Sri Lanka and has the chance of long term sustainability.

Keywords: mental health, primary care, trainers, training

Introduction

This paper describes a project to establish a systematic ‘Train the Trainers’ programme to integrate mental health into primary care in Sri Lanka in 2009–2011. It was funded by the World Psychiatric Association (WPA), and carried out in collaboration with the National Institute of Mental Health, Sri Lanka, and in dialogue with the Sri Lanka Ministry of Health.

Mental health needs in Sri Lanka are probably as high if not higher than in other parts of the world. Indeed the suicide rates are amongst the highest globally, with 1994 figures of 49.6 per 100 000 males and 19 per 100 000 females per year,1 more recently estimated at 25 per 100 000.2 However, there is a dearth of systematic epidemiology in the country. A subnational mental health survey was commissioned by the Ministry of Health in 2007 with the assistance of the World Bank, Health Sector Development Project, but has not been published. A study of 89 people in one tsunami-affected area found rates of 40% common mental disorder (CMD),3 and the WHO country office estimated a 3% incidence of severe mental disorder.4

The Sri Lankan health system is a government-funded decentralised public health system, accompanied by a robust private sector. Table 1 shows the different health system levels and the cadres at each level. Sri Lanka has long emphasised prevention and public health, and this is reflected in the division of labour for different cadres, with some of focusing on public health and others focusing on treatment of the disorder, resulting in two parallel sets of health tiers, one for preventive work and the other for curative work. This emphasis on public health has probably contributed to Sri Lanka's high immunisation rate and good life expectancy relative to some other middle-income countries. In total, 1.6% of the total health budget is spent on mental health.5

Table 1.

Health system structure in Sri Lanka

| Health system level | Population coverage | Management structure | Public health system cadre | Treatment system cadre | Private system |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ministry of Health Special and teaching hospitals |

19 million | Secretary of Health (Permanent Secretary) Director General of Health Services Deputy Director General Medical Services Director of Mental Health |

Director of Mental Health is a public health doctor | No psychiatrist in Ministry of Health | |

| National Institute of Mental Health 269 acute beds, all the s. |

19 million | Director Dr Jayan reports to Deputy Director General Medical Services |

8 psychiatrists 300 psychiatric nurses 0 psychologists 6 occupational therapists |

||

| 9 provincial hospitals 421 acute beds |

2.1 million | Provincial Health Minister Provincial Health Council |

1 psychiatrist 12–15 psychiatric nurses 0 psychologists 1 occupational therapist 1 social worker |

||

| 25 district hospitals A few have a small number of acute beds, e.g. Negombo, Trincomalee and Kalmunai |

0.76 million | District medical officer ? District Health Council (3 districts don't have a psychiatrist) |

276 Medical Officers of Health (MOHs) – deal with public health, maternal, child health, immunisation, prevention, teaching and training. | 1 psychiatrist 10 psychiatric nurses 0 psychologists 1 occupational therapist 110 MOMHs; The intention is to have 276 in total 276 district medical officers 392 district assistant medical officers 144 consultant specialists, and some community support officers (ex-midwives) in 3 districts as pilot Report to MMOH |

|

| Subdistrict hospitals | Accountable to district medical officer | 254 PHNs 1697 PHIs 8937 midwives |

Medical officers working in outpatient departments | ||

| Rural hospitals Not much used: going to transform to long-term care |

Accountable to district medical officer | Registered medical practitioners 1–2 nurses 1 midwife |

|||

| Dispensaries | 10 000 | Accountable to district medical officer | Registered medical practitioners (3 year training) | Private GPs Accountable to the public system, but do have their own college |

|

Health care in Sri Lanka is funded by two streams: directly by central government and more locally via the provincial council. However, there is no ring-fenced or indeed identifiable active separate budget line or heading dedicated to mental health used to allocate funds. The contribution from the non-governmental sector for mental health prevention and promotion programmes at the national level is 55%, while the state provides 45%.5

Sri Lanka has a population of 19 million and 48 consultant psychiatrists. There are no specialised psychiatric nurses, but 800 nurses attached to psychiatric units having some experience in psychiatry, only three psychologists who are attached to the university units, 57 occupational therapists, 20 psychosocial workers (PSWs) and 60 assistant PSWs. Thus there is approximately one consultant psychiatrist per 500 000 persons, with these psychiatrists placed at the national, provincial and district levels in the health system.

There are also 110 medical officers of mental health (MOMHs) in the country. This cadre is a relatively recent development in Sri Lanka, developed to assist in the decentralisation of mental health services. MOMHs are qualified doctors who have been selected either for a 1-month course in psychiatry or a 12-month diploma in psychiatry, leading to a certificate from the College of Psychiatrists, and the title of medical officer of mental health. The diploma course was initiated by the Sri Lankan College of Psychiatrists and is now delivered by the Postgraduate Institute of Medicine. The aspiration is to have one MOMH in each of the 276 subdistricts in which case there will eventually be one MOMH per 70 000 population; at present there are 110 MOMHs, resulting in an actual ratio of one per 173 000 population.

Primary health care is delivered in dispensaries, each responsible for around 10 000 population and staffed by registered medical practitioners (who have three years of medical training) and general nurses. There are also numerous private general practitioners (GPs) who have their own professional college and standards but are not accountable within the public system. However, they are crucial to consider here as they see a significant proportion of the general population and are a major source of referral of people with mental illness.

Thus, the mental health programme has until now been staffed as a vertical programme from national to subdistrict level. Neither the current nor the planned availability of MOMHs is adequate for MOMHs to be the front line health workers for mental health, and to see, assess and manage all those with a mental disorder. Rather it makes logistical sense that they should be viewed as the first level of specialist care, taking referrals from primary care, with more complex referrals being passed to district psychiatrists. Whether the prevalence rates of mental illness are similar to those in the rest of the world or higher than elsewhere, if the general population of Sri Lanka is to have equitable access to mental health care, it is essential to integrate mental health into primary care (the lower levels of the health system including the general health workers and public health workers in subdistricts, rural hospitals and dispensaries). Certainly a staff to population ratio of either one per 173 000 (current situation) or of one per 70 000 (planned situation) is completely inadequate to form the front line of mental health care.

Given the scarcity of psychiatrists, psychiatric nurses and MOMHs, it is therefore crucial, as it is in all other countries,6 to include mental health in the basic training, post basic training and continuing professional development of all health cadres at subdistrict, rural hospital and dispensary levels in both curative and preventive services. This will include the medical officers working in outpatient departments, for OPD, the MOMHs, the public health nursers (PHNs) and public health inspectors (PHIs). In Colombo, the National Institute of Mental Health has already run some training courses for registered medical practitioners and family health workers on mental health.

The WPA has therefore funded a programme of collaboration with the Sri Lankan Ministry of Health and the National Institute of Mental Health to integrate mental health into the work of the lower tiers of the health service, both curative and preventive. This paper describes the methods and results of that programme to date and discusses the challenges to the integration of mental health into primary care, in the context of other similar efforts elsewhere in the world.

Methods

Co-ordination

The co-ordinating team consists of Professor Rachel Jenkins, Director of the WHO Collaborating Centre, Institute of Psychiatry, King's College London; Dr Jayan Mendis, Director of the National Institute of Mental Health, Sri Lanka; and Drs Sherva and Marius Cooray, in dialogue with Professor Mario Maj, President of the WPA. Detailed discussions with Sri Lankan partners and stakeholders was undertaken through 2009 in order to enable the selection of the appropriate cadre to deliver efficient training to front line general health workers, training sites and adaptation of the training materials for Sri Lanka (see below).

Funding

The WPA allocated funding to train 155 trainers (45 psychiatrists, 110 MOMHs) and 95 specially selected others (registered medical practitioners, DMOs) in order to equip the trainers to roll out the training on a continuous basis funded by local district health funds.

Training methods and materials

Curriculum and teaching materials were originally developed by the WHO Collaborating Centre for a Nuffield Foundation-funded programme to train primary care staff in Kenya, in collaboration with Kenya partners (colleagues in primary care, the Ministry of Health, University of Nairobi, professional and regulatory bodies for nurses and clinical officers), and based on the Kenyan adaptation of the WHO primary care guidelines.7,8 These teaching materials have subsequently been adapted for use in Malawi, Nigeria, Pakistan, Iraq and Oman. They were adapted by Sri Lankan colleagues for Sri Lanka in 2009. A cluster randomised controlled trial of the training course has been conducted in Malawi on health worker diagnostic practice,9 and a second in Kenya is underway to assess client health and social outcomes as well as health worker practice,10 and both will report in due course. A randomised controlled trial has also been carried out in Iraq, which has demonstrated improved physician behaviour and competencies, as observed by research psychiatrists in routine consultations in the primary care centres and improved client perceptions of physician behaviour and competencies on patient exit interviews.11

The training programme for primary care is a 5-day course, and consists of five modules, the first covering core concepts (mental health and mental disorders and their contribution to physical health, economic and social outcomes); the second covering core skills (communication skills, assessment, mental state examination, diagnosis, management, managing difficult cases, management of violence, breaking bad news); the third covering common neurological disorders (epilepsy, Parkinson's disease, headache, dementia, toxic confusional states); the fourth covering psychiatric disorders (content based on the WHO primary care guidelines for mental health, Sri Lankan adaptation); and the fifth covering health and other sector system issues of policy (legislation, links between mental health and child health, reproductive health, HIV and malaria; roles and responsibilities, health management information systems, working with community health workers and with traditional healers, and integration of mental health into annual operational plans).

The course is conducted through multimethod teaching of theory, discussion, role-plays and WPA videos on depression, psychosis and somatisation. There is a major emphasis through the course on the acquisition of practical skills and competencies for assessment, diagnosis and management. Each participant has to complete over 25 supervised role-plays on different topics in the course of the week, and to observe and comment on 25 role-plays conducted by colleagues. The role-plays, videos, discussions and theoretical slides are accompanied by the Sri Lankan WHO primary care guidelines. Each participant is given both a hard copy print out and a CD of the guidelines, plus all the teaching slides, role-plays and teacher's guide.

Pilot study

In November 2009, we trained 25 MOMHs and five psychiatrists in a pilot run funded by the Cooray Family Trust. In the light of this experience, we have further revised the training materials to suit Sri Lanka.

Training sites

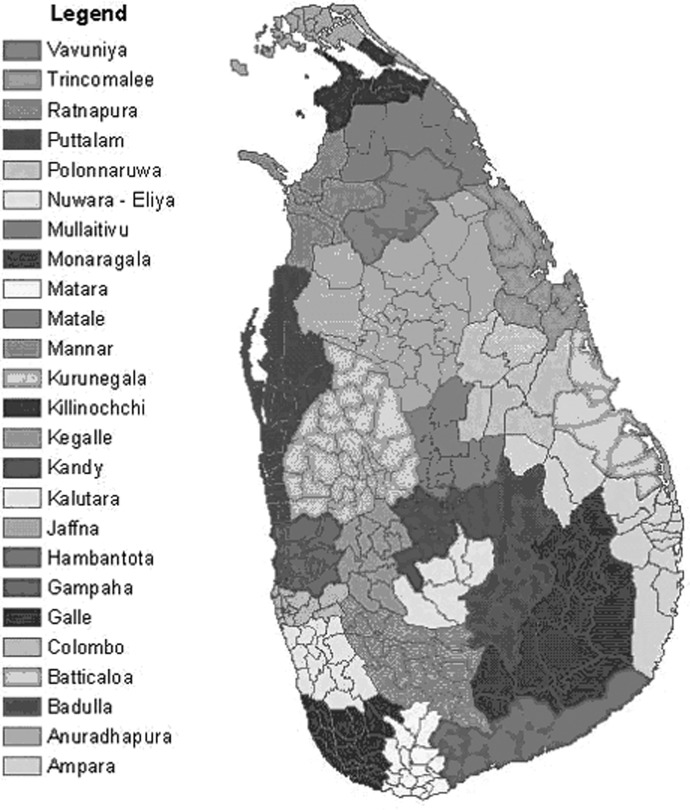

In 2010/11, the remaining MOMHs and all the MOHs were trained over five training weeks based respectively in Colombo (capital city on west coast), Kandy (centre of Sri Lanka), Jaffna (north coast), Batticoloa (east coast) and Galle (south coast) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Sri Lanka training: Colombo, Kandy, Jaffna, Batticoloa, Galle

Selection of participants

Participants were selected for training by the senior psychiatrist of that region, using criteria developed in discussion with the trainers. Criteria for selection included all MOMHs, and other mental health cadres who were able to commit time to subsequent roll out of the training programme to primary care staff. It proved difficult on Jaffna, a site of long-standing serious conflict, to deploy all MOMHs to the training course as their workloads were too heavy for them to be released, and instead a variety of other district and primary care general health staff were also included in the training course.

Evaluation

Opening workgroups on the problems faced by MOMHs graphically described the pressures they have to deal with as a result of the lack of integration of mental health in primary care (Box 1).

Box 1. Problems faced by medical officers of mental health.

Excessive workload – too many patients to be seen by the doctor in the clinic.

Very little time available for each patient, e.g. 1200 patients have to be seen by 20 doctors in 6 hours in a clinic, which is 60 patients per doctor, 10 patients an hour or 6 minutes each patient.

Lack of time to take a history or to educate the patient about their illness and medicine compliance.

Lack of adequate knowledge about mental health in doctors (stemming from too little exposure to psychiatry in basic training, and in continuing professional development).

Shortage of essential medicines in clinics and inpatient units.

Shortage of dedicated beds for psychiatry, so that sometimes agitated patients have to be cared for on a general medical ward, which creates difficulties.

The need to transfer some patients to distant inpatient units results in a greater financial burden to the family and creates problems for families, especially for poor people. Sometimes very aggressive patients have to be transferred to Angoda for a few days and are then transferred back before recovery.

Lack of community based psychiatric treatment settings. Patients are discharged home after acute treatment, but then with lack of adequate follow-up there are frequent relapses.

Too few staff, with no social workers or occupational therapists available.

Lack of laboratory facilities.

Declining family support to patients.

Language problems, especially with Tamil populations.

Cultural stigma towards psychiatric staff and patients.

Shortage of medical officers even at tertiary care units, leading to multiple management problems.

Lack of compliance by patients.

Phase 1 testing of the training intervention so far has included: (1) iterative improvement of the course, based on feedback from teachers and students on the early courses; (2) detailed collated written feedback from participants, regularly scrutinised by teachers (see Box 2); (3) pre- and post-test evaluation of the participants (see Table 2); and (4) a follow-up questionnaire several months after the training (to be published elsewhere). We also plan examination of routine data collected before and after training in two districts and supervision observations of clinical practice in 15 health facilities across three districts – in collaboration with the Ministry of Health – in order to appraise how efficient and effective the level 2 and 3 service providers in mental health management were following their participation in the training course (to be published elsewhere). Ethical approval was not required for Phase 1 testing of the training intervention.

Box 2. Qualitative feedback from participants about the training course.

What do you think of the course?

Very practical.

Useful; good overview; excellent teaching material; could be done faster, especially if everyone attending has some basic training in psychiatry.

Good.

Really good and very interesting – learnt a lot that helped me a lot.

Teaches us to delegate responsibility so more time can be allocated per client.

Very beneficial.

Very good, very refreshing and practicable ways in practicing psychiatry.

Up-to-date training for us for our work that will help patients and families achieve good mental health.

Good – it reminds of our duties to the society.

I learned to think from this course.

Excellent.

Very useful.

Indeed helpful. Fruitful.

Extremely good.

Very useful and informative.

Most helpful and will improve the training skills of the participants.

Excellent; benefit a lot.

Very informative and educative; presented in a very interesting way.

Do you think it may help others and if so how?

To help others.

Ideas for teaching, training and co-ordination. Meeting others involved in the same area of work. Teaching material of good standard is available so I can conduct teaching sessions without worries. Eye opener about patients' rights.

Yes – a bio-psychosocial approach to patient care.

Yes, when dealing with patients and with university students and also in general practice.

To reduce workload, provide better care for patient, to organise and review work and to improve knowledge.

Yes. I will spend more time with patients.

Definitely. As a general practitioner, motivation to learn more about psychiatry and counselling.

Will help with bio-psychosocial interventions, and especially with breaking bad news.

Yes! To be more vigilant while taking history to probe for underlying mental illness which is not immediately presented to the doctor.

Yes.

Yes – to do better mental health service at primary care level.

To practise at workplace.

Yes: mainly to train others and also managing patients.

Yes. Got a more comprehensive view about mental illnesses. How to manage patients.

Yes – it will help me a lot.

Improve the communication/teaching skills; change the thinking patterns; gained motivation towards community health.

Yes, of course.

Yes. Helpful in identifying the mentally ill patients at outpatient level.

Do you have any suggestions for improvement of the course?

Role-plays in Sinhalese would be more practical. Some repetition and overlap in slides which could be reduced.

Lengthen time allocated to role-plays.

Can include some more counselling sessions.

More detail on community work in villages and rural areas.

Get more trainers.

Put up a summary slide at the end of a topic.

The course duration should be longer.

Make it more interactive.

Create more group work.

Same course, expand to 1 week.

Any other comments?

This course is exhausting for the lecturers!

Refreshments are very good; both lecturers very co-operative.

Thank you very much.

Train all medical staff to recognise and respect mental illness.

Consider OPD and GP set up as the primary care level.

Good work!

Please hold similar programmes to other cadres including medical officers, psychiatrists, other specialty doctors and general staff.

Details of course should be informed prior; we came to know the contents once we came to the lecture hall.

Table 2.

Pre- and post-test scores before and after training

| Training centre | Pre-test mean score (%) | Post-test mean score (%) | Number of participants completing tests |

|---|---|---|---|

| Colombo | 66.4 | 82.0 | 32 |

| Kandy | 74.0 | 90.0 | 46 |

| Jaffna | 62.8 | 67.4 | 35 |

| Batticola | 69.0 | 77.0 | 51 |

| Galle | 74.9 | 76.4 | 20 |

Examples of written feedback from participants

Box 2 gives examples of written feedback from participants, who generally found the course extremely helpful, partly to update their own clinical skills and partly as a user-friendly comprehensive teaching toolkit to enable them to teach others.

Pre- and post-test evaluation

Table 2 shows the pre- and post-test evaluation scores in each of the five training sites. It can be seen that pre-training scores were good, indicating the relatively high quality of the basic training already received by the MOMHs. Nonetheless, our continuing professional development course was still able to achieve improvements between pre- and post-course test scores. We do not present significance tests as the sample sizes for each training course are relatively small.

The trainers (the current authors) of the ‘Train the Trainers’ course found that they initially had to work hard to achieve vigorous participation by the trainees, who are more used to didactic teaching and a powerful educational hierarchy. The use of multiple discussion sessions and role-plays facilitated active learning, and by the end of the first day participation was usually very good. The participants were expected to practice core competencies, including, and especially, assessment of severity of depression, of suicidal risk, giving psychosocial support to client and carer, and explanation of side effects of medications to assist adherence.

Discussion

This paper has described a systematic ‘Train the Trainers’ programme to integrate mental health into primary care in Sri Lanka, structured as a partnership between WPA, the Ministry of Health, and the National Institute of Mental Health, using the Sri Lankan UK diaspora and the WHO Collaborating Centre, Institute of Psychiatry, King's College London to deliver training to the trainers. We believe such a partnership has helped to ensure that the training is suitable for Sri Lanka, fits into wider Sri Lankan initiatives, and has the chance of long-term sustainability. The training programme for trainers has proceeded according to schedule and participants have found it helpful both for their own practice and for teaching others (see Box 2). These trainers are enthusiastic about running training courses for the various cadres working in subdistrict hospitals, rural hospitals and dispensaries, and can see that such training will greatly enhance the ability of these lower levels in the health system (see Table 1) to reduce the numbers of clients who need to be referred to the MOMHs, and hence will enable more time to be spent by the MOMHs as well on each patient, leading to better assessments and follow up and also freeing up time in the working day for more intersectoral collaboration.

In order to assist decentralised mental healthcare, participants in the training courses suggested that it would be very useful to establish a formal system of intersectoral collaboration for mental health, which could usefully follow the model of the National Authority on Tobacco and Alcohol. This national authority has oversight of district committees which contain representation from the Department of Police, the Excise Department, Education and non-governmental organisations (NGOs), receive regular funding and meet at least once a year. The equivalent district mental health fora could contain representation from the regional directors of health, an MOMH, social services, NGOs and relevant other stakeholders, and should meet quarterly to strengthen population access to mental health care. Continuing dialogue and technical support over the coming years will be helpful in facilitating this process. However, there is concern that the cadre of MOMH is difficult to sustain as incumbents are seeking promotion elsewhere faster than new ones are being trained. If it survives, it represents a useful layer of the mental health system and a unique decentralised training resource for primary care.

Ministry of Health funding for the roll out has so far been difficult to achieve as the government is short of funds due to the recent natural disasters and conflict. Others have commented on the widespread problem of financial allocation to mental health,12,13 illustrated by the analysis of the 2006–07 WHO budgets which revealed that the funds allocated between communicable and non-communicable diseases are disproportionate, with 87% of budget allocated to infectious diseases, 12% allocated to non-communicable diseases, and only 1% to injuries and violence.14 Continued advocacy and collaborative efforts will be crucial, with both Ministries of Health and international donors.15–22

This course is different from other mental health courses evaluated in the literature in a number of ways. First, it has an extensive emphasis on active participation through discussions and role-plays. During the 5-day programme each participant has to complete 27 observed role-plays, and participate in over 30 discussion groups. Second, it is designed to be relatively comprehensive in approach. It addresses not a single disorder or group of disorders,23,24 but rather all the broad categories of disorder that may present in primary care. It also addresses core concepts, core mental health skills, neurological disorders, links with key physical health topics, and issues of policy, legislation, human rights, health management information systems, etc. Thus it is designed to cover the core components of knowledge and skills required to deliver mental health in primary care. The participants are all given the complete package of training materials after the course so that they themselves can deliver it afterwards, either in its entirety or in modules as circumstances allow. The programme has not aimed to produce a new cadre of mental health worker, but rather to train the cadres that already exist.25

Since the design and implementation of this course, WHO has produced MhGAP guidelines which are constructed as diagrammatic algorithms, which may assist primary care staff in their busy clinics. Training courses will be developed in due course for these guidelines, and will hopefully build on the comprehensive approach described here.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors are extremely grateful for the financial support received from the WPA for the five training weeks in 2010 and 2011, and from the Cooray Family Trust for the pilot work in 2009 and their continuing interest in the success of the programme. We are also grateful for the assistance of Sri Lankan colleagues in each of the training centres who have given considerable assistance with planning and co-ordination of the training weeks.

Contributor Information

Rachel Jenkins, Director of WHO Collaborating Centre, Institute of Psychiatry, King's College London, London, UK.

Jayan Mendis, Director of National Institute of Mental Health, Sri Lanka.

Sherva Cooray, Consultant Psychiatrist, Central and North West London NHS Foundation Trust, The Kingswood Centre, London, UK.

Marius Cooray, Consultant in Occupational Medicine, Consultant in Occupational Medicine and General Practitioner.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization Suicide Rates (per 100 000), by Country, Year, and Gender. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gunnell D, Fernando R, Hewagama M, et al. The impact of pesticide regulations on suicide in Sri Lanka. International Journal of Epidemiology 2007;36:1235–42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hollifield M, Hewage C, Gunawardena C, et al. Symptoms and coping in Sri Lanka 20–21 months after the 2004 tsunami. British Journal of Psychiatry 2008;192:39–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization Mental Health Update, Country Office Sri Lanka, 2008. www.whosrilanka.org/LinkFiles/WHO_Sri_Lanka_Home_Page_Mental_Health_Factsheet.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kitsiri R. Policy Study Report: financing public health care in Sri Lanka. Basic Needs International, 2009. www.basicneeds.org/download/PUB%20-%20Financing%20Mental%20Health%20Care%20in%20Sri%20Lanka%20-%20BasicNeeds%20Sri%20Lanka%202009.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization Report of the International Conference on Primary Health Care Alma Ata, USSR. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1979 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jenkins R, Kiima D, Njenga F, et al. Integration of mental health into primary care in Kenya. World Psychiatry 2010;9:118–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jenkins R, Kiima D, Okonji M, et al. Integration of mental health in primary care and community health workers in Kenya: context, rationale, coverage and sustainability. Mental Health in Family Medicine 2010;7:37–47 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kauye F, Jenkins R. Impact on diagnostic practice of a structured mental health training course for primary care workers in Malawi – a cluster randomised controlled trial. 2011

- 10.Jenkins R, Kauye F, Basset P. Impact on client outcomes of a structured mental health training course for primary care workers in Kenya – a cluster randomised controlled trial. 2011

- 11.Sadiq S, Abdulrahman S, Bradley M, Jenkins R. Integrating mental health into primary care in Iraq. Mental Health in Family Medicine 2011;8:39–49 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saraceno B, Ommeren M, Batniji R, et al. Barriers to improvement of mental health services in low-income and middle-income countries. The Lancet 2007;370:1164–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jenkins R, Baingana F, Belkin G, et al. Mental health and the development agenda in Sub-Saharan Africa. Psychiatric Services 2010;61(3):229–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stuckler D, King L, Robinson H, McKee M. WHO's budgetary allocations and burden of disease: a comparative analysis. The Lancet 2008;372(9649):1563–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jenkins R, Baingana F, Ahmed R, et al. Should development agencies care about mental health. Mental Health in Family Medicine 2011;8:65–7 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jenkins R, Baingana F, Ahmed R, et al. Mental health and the global agenda: core conceptual issues. Mental Health in Family Medicine 2011;8:69–82 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jenkins R, Baingana F, Ahmed R, et al. Scaling up mental health services: where would the money come from? Mental Health in Family Medicine 2011;8:83–6 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jenkins R, Baingana F, Ahmed R, et al. Social, economic, human rights and political challenges to global mental health. Mental Health in Family Medicine 2011;8:87–96 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jenkins R, Baingana F, Ahmed R, et al. What action can national and international agencies take? Mental Health in Family Medicine 2011;8:97–9 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jenkins R, Baingana F, Ahmed R, et al. International and national policy challenges in mental health. Mental Health in Family Medicine 2011;8:101–14 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jenkins R, Baingana F, Ahmed R, et al. How can mental health be integrated into health system strengthening? Mental Health in Family Medicine 2011;8:115–17 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jenkins R, Baingana F, Ahmed R, et al. Health system challenges and solutions to improving mental health outcomes. Mental Health in Family Medicine 2011;8:119–27 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rahman A, Malik A, Sikander S, et al. Cognitive behaviour therapy-based intervention by community health workers for mothers with depression and their infants in rural Pakistan: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. The Lancet 2008;372(9642):902–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zakroyeva A, Goldberg D, Gask L, Leese M. Training Russian family physicians in mental health skills. The European Journal of General Practice 2008;14(1):19–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Patel V, Weiss HA, Chowdhary N, et al. Effectiveness of an intervention led by lay health counsellors for depressive and anxiety disorders in primary care in Goa, India (MANAS): a cluster randomised controlled trial. The Lancet 2010;376(9758):2086–95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]