Abstract

Arthritis is highly prevalent and is the leading cause of disability among older adults in the United States owing to the aging of the population and increases in the prevalence of risk factors (e.g., obesity). Arthritis will play a large role in the health-related quality of life, functional independence, and disability of older adults in the upcoming decades. We have emphasized the role of the public health system in reducing the impact of this large and growing public health problem, and we have presented priority public health actions.

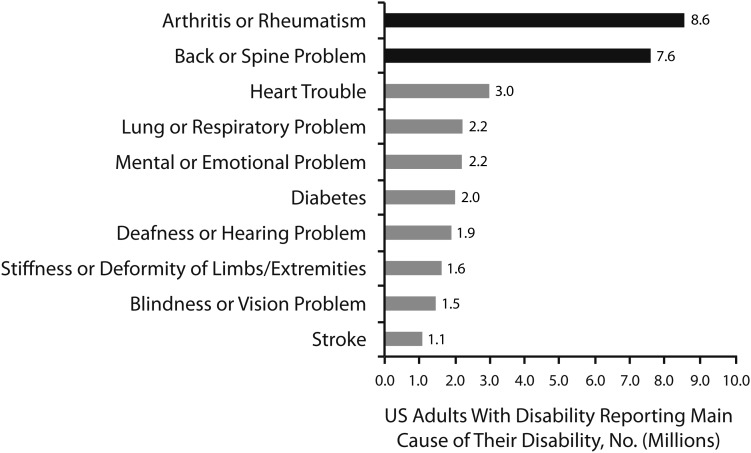

Decreasing mortality rates combined with the entry of the large baby boomer generation into age groups at higher risk means that there will be many more older adults living more years with chronic conditions than ever before. Chronic musculoskeletal conditions, such as arthritis, are among the most common chronic diseases that affect millions of American adults. They are also disabling: among the 47.5 million US adults who have a disability,1 8.6 million report arthritis and rheumatism and 7.6 million report back or spine problems as the main cause of their disability (Figure 1). Because of the aging of the population and increases in risk factors (e.g., obesity), these conditions will likely play a large role in the health-related quality of life and disability of older adults in the upcoming decades.

FIGURE 1—

Most common causes of disability among US adults 18 years and older: Survey of Income and Program Participation, 2005.

Source. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.1

We have provided a state-of-the-art perspective on arthritis as a prototypical musculoskeletal condition, emphasizing the role of the public health system in reducing the impact of this large and growing public health problem. We have provided examples from our 10-year experience with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's (CDC's) Arthritis Program that may help in the development of a useful public health practice framework for addressing other chronic musculoskeletal conditions, such as osteoporosis and chronic back pain.

DESCRIPTION AND DEFINITION OF THE PROBLEM

Arthritis and other rheumatic conditions encompass more than 100 different diseases that affect the joints and surrounding connective tissues (muscles, tendons, and ligaments). These conditions are generally characterized by pain, aching, and stiffness in and around a joint. Inflammatory or systemic types of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus) can affect multiple organ systems (e.g., cardiovascular, renal, respiratory) and often have an autoimmune component. The most common type of arthritis is osteoarthritis. The long-term effects of arthritis include worsening of joint symptoms, joint deformity, and disability.2

Arthritis Disability Is Preventable and Treatable

Arthritis is the most common cause of disability,1 and more than 23% of incident disability in activities of daily living among older adults can be attributed to arthritis.3

Strong scientific evidence supports the fact that engaging in aerobic and muscle-strengthening exercise reduces pain, increases function, improves quality of life, and delays disability among people with arthritis.4–6 Longitudinal studies suggest that if older adults with arthritis engage in regular physical activity, age-related functional decline can be reduced by as much as 32%.7 In a randomized controlled trial of aerobic and muscle-strengthening exercise among older adults with knee osteoarthritis, incident activity of daily living disability was reduced by about 43% over 18 months.8

Excess weight increases pressure on the joints, and modest weight loss improves important clinical symptoms of arthritis, such as functional limitation, pain, and disability. In several randomized controlled trials, weight loss significantly improved physical function by as much as 28%.9–13 Even small amounts of weight loss are beneficial. For example, weight loss of about 5% (about 12 lbs for a person weighing 250 lbs) significantly reduced pain and physical disability,11 and weight loss of about 10% has been shown to have moderate to large clinical effects on disability.12 Intentional weight loss among those with osteoarthritis may even lower mortality risk by about 50%.14 Multiple professional guidelines suggest that health care providers advise all overweight or obese patients with osteoarthritis to lose weight.15–18

Self-management education is an interactive educational process that focuses on building skills such as goal setting, decision-making, problem-solving, and self-monitoring and is different from didactic arthritis education and information dissemination.19,20 Persons with arthritis who participate in self-management education programs have small, but important improvements in self-efficacy (including confidence in their ability to manage their condition), psychological health (including anxiety and depression), and physical health (including fatigue and social role limitations).19 Widespread community dissemination of these relatively low-cost, effective programs is facilitated by the availability of disease-specific (arthritis self-management programs) and generic (chronic disease self-management programs) formats, the use of trained lay leaders as instructors, and the existence of basic training and program support infrastructure.20

Early diagnosis and appropriate clinical care with a growing spectrum of effective disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, especially newer biological response–modifying drugs, have been shown to improve prognosis and outcomes for inflammatory types of rheumatic disease, such as rheumatoid arthritis. Early treatment with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs limits radiographic joint damage, improves health-related quality of life, and reduces lost work disability days.21–26 In a Dutch study, individuals whose time from symptom onset to assessment by a rheumatologist was more than 12 weeks had significantly higher rates of joint destruction over 6 years.26

Effective Arthritis Interventions Are Underutilized

Despite the known health benefits of being physically active, 55% of adults with arthritis aged 65 years and older are physically inactive.27 Adults aged 65 years and older with arthritis report low rates of health care provider counseling for weight loss (39%) and exercise (50%) and low levels of arthritis education (8.5%).28 Lack of awareness and knowledge of effective arthritis management interventions among consumers and health care practitioners likely contribute to this underutilization. Audience research with people with arthritis indicates that many believe that arthritis is something to be tolerated, not managed, and they do not begin to seek out solutions until their arthritis begins to threaten their valued life activities (unpublished 2000 CDC reports). Healthy People 201029 and now Healthy People 202030 arthritis management objectives address arthritis education as well as health care provider counseling for weight loss and physical activity. From 2002 through 2006 there has been a modest 18% improvement in self-reported rates of health care provider counseling for weight loss among overweight or obese adults with arthritis (aged 18 years and older)28 but no change for the other 2 objectives, exercise and education; rates for all 3 objectives still fall below Healthy People 2010 targets. Adults aged 65 years and older have particularly low rates of participation in evidence-based arthritis education (8.6%).28 Despite evidence-based clinical guidelines focused on nonpharmacological treatments for osteoarthritis, such as weight loss and physical activity, current clinical practice does not reflect these guidelines.31 For example, in the United States at least 1 medication was ordered or continued in 71% of ambulatory care visits for arthritis, whereas counseling or education for diet or nutrition (9% of visits) and exercise (19% of visits) were ordered much less frequently.32

EPIDEMIOLOGY AND PUBLIC HEALTH BURDEN

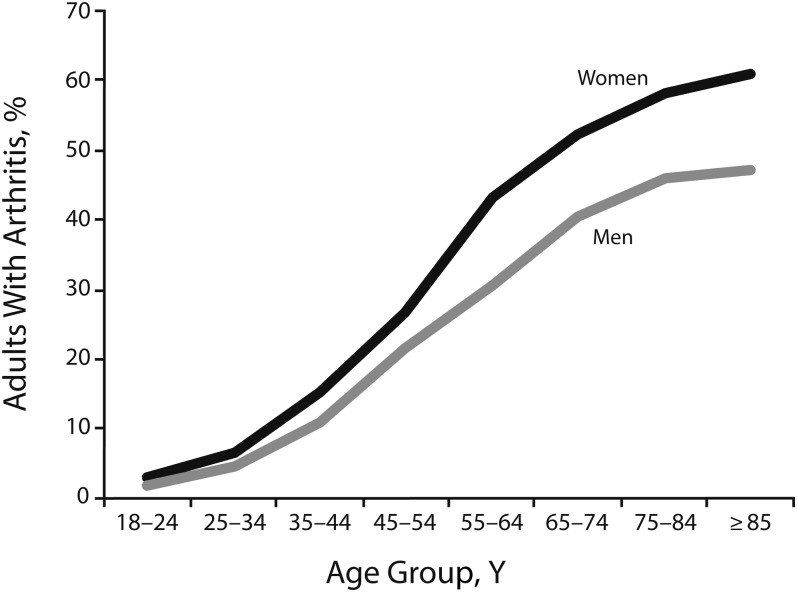

In 2007–2009, 21% (50 million) of US adults aged 18 years and older had doctor-diagnosed arthritis.33 Arthritis prevalence increases steadily with age (Figure 2), affecting 29.8% of those aged 45 to 64 years and 50.0% of those aged 65 years and older. Women have a higher prevalence of arthritis than do men at all ages. However, arthritis is not just an old person's disease; two thirds of adults with arthritis are younger than 65 years.33 Based purely on the aging of the population (and not accounting for the current obesity epidemic), the projected prevalence of arthritis is expected to exceed 67 million individuals (25 million individuals with arthritis-attributable activity limitations) by the year 2030.34

FIGURE 2—

Prevalence of arthritis among US adults 18 years and older, by age and gender: National Health Interview Survey, 2007–2009.

Source. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Unpublished Data.

Osteoarthritis is the most common type of arthritis, affecting approximately 27 million adults overall and 12 million (34%) adults aged 65 years and older.35 Other prevalent types of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions among adults aged 18 years and older include rheumatoid arthritis (1.3 million), systemic lupus erythematosus (approximately 300 000), gout (3 million), and fibromyalgia (5 million).35,36 Although the medical management of these various types of arthritis are very different, arthritis management strategies such as maintaining a healthy weight, being physically active, and participating in self-management education are appropriate and beneficial for all types of arthritis and may be extremely beneficial in preventing loss of independence and disability among older adults.

Impact

Arthritis has substantial personal and societal effects. Among adults with arthritis aged 65 years and older, 45.4% report arthritis-attributable activity limitations,32 and about 1 in 4 report severe pain.37 Among working-age adults with arthritis, 30.6% (7 million) report work limitations because of arthritis.38 These arthritis-related impairments and limitations are associated with poor mental health and diminished health-related quality of life39–41 and higher rates of physical inactivity and obesity27,42 and likely contribute to arthritis being the most common cause of disability.1 In 2003, arthritis among adults aged 18 years and older cost the United States $128 billion in direct costs (medical expenditures) as well as indirect costs (lost wages), accounting for approximately 2% of the annual gross domestic product.43

Comorbidity

Because the prevalence of arthritis is high, it often co-occurs with other chronic diseases, resulting in more activity limitation, disability, and perhaps early mortality. More than 50% of adults aged 18 years and older with diabetes or heart disease and 31% of obese adults also have arthritis.33,44,45 Arthritis may complicate the management of these common chronic conditions by limiting the ability to be physically active, a key self-management behavior for these and other chronic conditions. For example, adults with both diabetes and arthritis were found to be 1.5 to 2 times more likely to be physically inactive than were adults having only arthritis or diabetes.44

PUBLIC HEALTH APPROACHES AND INTERVENTIONS

In 1999, on the heels of the National Arthritis Action Plan: A Public Health Strategy,46 the US Congress appropriated the first-ever funding to address the public health burden of arthritis by creating the Arthritis Program at the CDC. The overall goal of the CDC Arthritis Program is to improve the quality of life of persons affected by arthritis. In collaboration with public health partners (aging services, community-based organizations, health foundations, etc.) over the past decade, the CDC Arthritis Program has been developing and growing a comprehensive public health program for arthritis that focuses efforts in the following 5 areas.

Defining the Epidemiology of Arthritis

Studies have established arthritis as a large and growing problem in the United States that has significant personal effects (e.g., severe pain, activity limitation, work limitation, disability, decrease in health-related quality of life) for all demographic groups and large societal effects (e.g., health care system burden, direct and indirect costs). To define this burden, it was necessary to develop and validate a standard case definition for self-report surveys (doctor-diagnosed arthritis) as well as a definition that can be applied in clinical and administrative databases that use diagnostic codes. A validated47,48 self-report case-finding question for arthritis surveillance has been used since 2002 in both national (the National Health Interview Survey) and state-based (the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System) annual health surveys. Self-reports of arthritis are used to monitor the burden and impact of arthritis at the national and state levels; particular emphasis is placed on data that are informative for guiding programmatic activities at the state and local levels. To assess the impact of arthritis on the health care system using other sources of administrative data, the National Arthritis Data Workgroup developed a definition of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions derived from the International Classification of Disease, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics).49 This definition has been used to monitor the impact of arthritis on ambulatory care as well as hospitalizations.32,50,51

Expanding the Number of Evidence-Based Interventions

The CDC has been expanding the number of evidence-based interventions to address arthritis by (1) actively identifying existing interventions appropriate for arthritis, (2) funding the development of new interventions, and (3) evaluating the effectiveness of new and existing interventions. With public health partners, the CDC established standard criteria (arthritis appropriateness, strength of evidence, and implementability as a public health intervention) and uses these criteria to screen existing self-management education and physical activity interventions for their usefulness in arthritis management.19 The menu of such programs has also been expanded through prevention research on the development and evaluation of new modes of intervention delivery (e.g., the Internet, self-study, and self-directed programs) and the addition of programs in different languages (e.g., Spanish).

For self-management education, the CDC promotes an arthritis-specific program (the Arthritis Self-Management Program), a similar program for Spanish-speaking adults (Programa de Manejo Personal de la Artritis), and 2 generic programs (the Chronic Disease Self-Management Program and its Spanish version, Tomando control de su salud). The generic programs are proven to help people with arthritis but address other chronic diseases as well (Table 1). These programs cover topics such as problem-solving, developing health habits such as regular exercise and relaxation, managing symptoms, appropriate use of medications, and communicating with your health care provider.

TABLE 1—

CDC Arthritis Program Recommended Evidence-Based Self-Management and Physical Activity Interventions for Adults With Arthritis

| Description | For More Information | |

| Self-Management Education | ||

| Arthritis Self-Management Program | Small group sessions taught by 2 trained leaders meeting wkly for 2-h classes for 6 wk. Content includes focus on health behaviors, medication use, cognitive symptoms management using skills such as goal setting, and problem-solving. | http://patienteducation.stanford.edu/programs/asmp.html |

| Chronic Disease Self-Management Program | Small group format lead by 2 trained leaders meeting wkly for 2–2.5 h/session for 6 wk. Persons with a variety of chronic conditions attend together. The content is not arthritis specific but focuses on health behaviors and general disease management skills. Self-study mail-based and interactive group Internet versions are also available; however, infrastructure for widespread dissemination is still in development. | http://patienteducation.stanford.edu/programs/cdsmp.html |

| Programa de Manejo Personal de la Artritis | A Spanish version of the Arthritis Self-Help Program conducted by 2 Spanish-speaking leaders. Course is culturally adapted and delivered in Spanish (not translated). | http://patienteducation.stanford.edu/programs_spanish/asmpesp.html |

| Tomando Control de su Salud | A culturally adapted Spanish language version of the Chronic Disease Self-Management Program conducted by 2 Spanish-speaking leaders who follow a standardized curriculum. Persons with a variety of chronic conditions, including arthritis, attend together. | http://patienteducation.stanford.edu/programs_spanish/tomando.html |

| Physical Activity | ||

| Arthritis Foundation Exercise Program | A nonaquatic group exercise class that includes aerobic (moderate intensity), muscle-strengthening, balance, and flexibility exercises. Classes meet 2–3 times/wk for 1 h and are ongoing or time limited (8–12 wk). Trained instructors select approximately 25 exercises from a menu of more than 90 for each session. The class can accommodate persons with varying functional levels; exercise can be adapted to be done sitting, standing, or lying down. | http://www.arthritis.org/af-exercise-program.php. Formerly known as People With Arthritis Can Exercise. |

| Arthritis Foundation Aquatic Program | A warm water pool exercise class developed specifically for people with arthritis. Group classes are offered 2–3 d per wk for 1 h and may be ongoing or time limited (8–12-wk sessions). Instructors complete a training course, are CPR certified, and typically hold water rescue or lifesaving certification. Participants do not need to know how to swim; all exercises are done in chest-deep water. | http://www.arthritis.org/aquatic-program.php |

| Arthritis Foundation Walk With Ease | A 6-wk walking program developed for sedentary adults with arthritis or other chronic conditions offered in 2 formats: traditional small group and self-directed. A trained instructor leads group sessions, which can be done indoors or outdoors. Group walks start with a short education topic and 10–40 min of walking, including a warm-up and cool-down period. A structured workbook, derived from behavioral change theory, guides self-directed participants to develop a safe and individualized walking program. | http://www.arthritis.org/walk-with-ease.php |

| EnhanceFitness | An ongoing small group exercise class developed for older adults (not specifically for people with arthritis). A rheumatologist and physical therapist have reviewed the exercises, and exercises are considered arthritis appropriate. Classes are offered 3 d/wk for 1 h and include conditioning, strengthening, balance, and flexibility exercises. Exercises can be done sitting or standing and can accommodate various functional levels. Periodic fitness assessments are used to assess participant progress. | http://www.projectenhance.org/admin_enhancefitness.html. Formerly known as Lifetime Fitness. |

| Fit and Strong! | Designed specifically for adults with lower extremity osteoarthritis, this small group exercise program includes 1 h of conditioning (aerobic walking) and strengthening exercise and 30 min of arthritis education. Certified exercise instructors lead classes, which are offered 3 times/wk. | http://www.fitandstrong.org |

| Active Living Every Day | A 12–20-wk group behavioral change program designed to teach participants how to identify and overcome barriers to physical activity, goal setting, and so on. Hr-long classes are conducted wkly and led by trained facilitators following a lesson plan. No exercise is done in class; participants learn how to incorporate physical activity into their daily lifestyle. | http://www.activeliving.info |

Note. CPR = cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

For physical activity, the CDC promotes walking, swimming, and biking as generally safe and feasible activities for most adults with arthritis. For those who want more support to become physically active or who need the security of knowing that the exercise they perform is appropriate for people with arthritis, 6 physical activity programs are proven safe and effective for persons with arthritis (Table 1). These programs offer a variety of choices, including arthritis-specific (e.g., Fit and Strong!, the Arthritis Foundation Exercise Program, the Arthritis Foundation Aquatic Program) and generic (EnhanceFitness, Arthritis Foundation Walk With Ease) exercise classes as well as a behavioral change program (Active Living Every Day) that teaches participants how to become and stay physically active using skills such as goal setting, recognizing barriers to being physically active, and rewards but does not include actual exercise during class.

Fostering Dissemination of Evidence-Based Interventions

Since 1999, the CDC has funded arthritis programs in state health departments and worked with national partners to foster the dissemination and adoption of evidence-based self-management education and physical activity programs to reach adults with arthritis. The CDC funds state health departments directly to create state arthritis programs and has funded between 12 and 36 programs every year since 1999. A primary goal of these state arthritis programs is to exponentially expand the reach of evidence-based self-management education and physical activity interventions across the state.52 The CDC has also indirectly funded arthritis activities in state health departments by working with the National Association of Chronic Disease Directors53 to fund other chronic diseases programs in state health departments to integrate evidence-based arthritis-appropriate interventions into their chronic disease program activities.

To provide technical assistance and training to support the dissemination of evidence-based arthritis management interventions, the CDC Arthritis Program also works with national partners54 such as the Arthritis Foundation, Project Enhance, the Stanford Patient Education and Research Center, the Administration on Aging, and the National Council on Aging, among others. Using funds from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, the Administration on Aging funded 45 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico to deliver the Chronic Disease Self-Management Program to older adults, build statewide delivery networks, and train the workforce to deliver this program in communities. A new partnership with the Y (also known as the YMCA) of the United States will seek to embed EnhanceFitness and other physical activity programs appropriate for people with arthritis in their national network and system of more than 2000 YMCAs in local communities across the United States.

Increasing Public Awareness of Management Strategies

The CDC and public health partners have identified and promote 5 key public health messages (see box on this page) through proactive media outreach and multicomponent community-based health communications campaigns. Utilizing extensive audience research, the CDC developed Physical Activity, the Arthritis Pain Reliever, a health communications campaign promoting physical activity among White and African American adults with arthritis, and Buenos Días, Artritis, a parallel campaign designed to promote physical activity among Spanish-speaking adults with arthritis. Both campaigns have demonstrated an increase in self-reported physical activity among respondents in communities where the campaign was conducted.55–57 Currently, all CDC-funded state arthritis programs conduct at least 1 of these campaigns in concentrated local areas each year, and campaign materials are available, free of charge, for other organizations to use as well.58 In addition, in 2010, the Arthritis Foundation worked with the Ad Council to release a public awareness campaign, Moving Is the Best Medicine,59 to foster greater awareness of arthritis management strategies.

Five Key Public Health Messages for People With Arthritis

| • Learn arthritis management strategies. Learn techniques to reduce pain and activity limitations through participating in self-management education programs available in communities across the country. Both arthritis-specific and generic (any or multiple chronic diseases) programs are offered in a variety of community settings including churches, senior centers, recreation centers and health care facilities. Classes are lead by 2 trained instructors and meet for 2.5 hours a week for a 6-week session. |

| • Watch your weight. Excess weight worsens arthritis symptoms, physical function and contributes to disability and poor outcomes after joint replacement surgery. Even small amounts of weight loss, about 10–12 pounds for a 200-pound woman, can improve symptoms. A variety of weight management approaches have been successful for persons with arthritis including behavioral modifications (diet, exercise, etc.), medication, and surgery. |

| • Be active. Physical activity produces healthier joints and improves balance needed for doing activities of daily living. For persons with inflammatory types of arthritis, physical activity can help mitigate the cardiovascular, pulmonary and renal complications associated with these conditions and help maintain bone health for persons taking long-term, low dose corticosteroids. Adults with arthritis are recommendeda to engage in at least 150 minutes per week (e.g., 30 minutes per day on 5 days per week) of at least moderate intensity aerobic activity such as walking, cycling, or water exercise and do muscle strengthening exercises at least 2 days per week. |

| • See your health care provider. Especially important for inflammatory types of arthritis, early diagnosis and appropriate medical treatment will slow progression and can prevent unnecessary disability. For osteoarthritis, implementing self-management strategies such as weight management and engaging in appropriate physical activity at the first sign of symptoms may delay disability and preserve independence. |

| • Protect your joints. Persons who have had previous trauma to the joints such as ruptured ligaments or serious fractures have higher rates of osteoarthritis. Certain occupations that involve carrying heavy loads, repeated knee bending or kneeling and collision or contact sports and recreation activities can lead to joint injuries. Following occupational and sports safety guidelines can help avoid joint injuries that may lead to arthritis. |

2008 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. Available at http://www.health.gov/paguidelines.

Bringing Stakeholders Together

Annually, arthritis state grantees and other partners, such as the local and regional offices of the Arthritis Foundation, meet to set goals, review progress, obtain technical assistance, and share information and best practices related to implementing evidence-based arthritis management interventions at the local community level. In addition, expert panels conducted by the CDC have examined topics such as physical activity and arthritis60 and pediatric rheumatic disease surveillance case definitions.61 In 2009, the Arthritis Foundation and the CDC brought together a group of more than 70 diverse experts and stakeholders to create a blueprint for public health action to address osteoarthritis, the most common type of arthritis. Released in February 2010, the National Public Health Agenda for Osteoarthritis62 outlines a strategic response to address osteoarthritis for the next 3 to 5 years and includes the following overarching goals:

To ensure the availability of evidence-based intervention strategies—such as self-management education, physical activity, injury prevention, weight management, and healthy nutrition—to all Americans with or at risk for osteoarthritis,

To establish supportive policies, communication initiatives, and strategic alliances for osteoarthritis prevention and management, and

To initiate needed research to better understand the burden of osteoarthritis, its risk factors, and effective strategies for prevention and intervention.62(p1)

In 2011, to facilitate implementation of the recommendations in the Agenda for Osteoarthritis, the CDC and the Arthritis Foundation held a meeting of the Osteoarthritis Action Alliance, a coalition of stakeholders and organizations interested in advancing the Agenda for Osteoarthritis, and a group of physical activity and policy experts to prioritize policy and environmental strategies that can facilitate physical activity among people with arthritis. The priority strategies developed from these 2 activities can be implemented by national, state, and local partners, including state arthritis programs.

OPTIONS FOR PRIORITY PUBLIC HEALTH ACTIONS

Arthritis prevalence and impact data illustrate the fact that arthritis is a large and growing public health concern among older adults that urgently needs attention. Public health and health care systems and community-based organizations can consider several options for action.

Forge Strategic Alliances

As with any complex public health problem, achieving improvements in health among adults with arthritis will take integrated efforts across multiple sectors. The long-standing CDC and Arthritis Foundation partnership has produced important changes in arthritis awareness and funding, which eventually should result in improved quality of life for persons living with arthritis. Because effective interventions (self-management education, physical activity, weight loss, etc.) for arthritis are also common to many chronic diseases such as heart disease, diabetes, and obesity, greater coordination of intervention efforts with these other chronic disease programs and partners would reach more individuals and subsequently increase the impact on health. Building and sustaining alliances with nonpublic health groups, including aging networks; federal, state, and local community organizations; health care systems; faith-based and religious organizations; employers and businesses; and others, can maximize the effects of existing resources and have the most impact on public health.

Expand Delivery of Evidence-Based Interventions

Despite proven effectiveness, evidence-based arthritis management interventions are clearly underutilized by persons with arthritis.28,31 This may be because of a lack of awareness or access to such programs as well as low rates of referral by health care providers. Awareness can be addressed with targeted communication campaigns; however, access and referral issues are more complex to resolve. One strategy to improve access and sustainability is to embed evidence-based interventions into existing organizations with multiple points of service delivery whose constituents or service users are likely to have arthritis. This systems approach of embedding interventions into the routine work of organizations with multiple service delivery points (as opposed to engaging single sites) has the potential to exponentially increase the reach of these interventions. Examples of strong delivery system partners include area agencies on aging (and other members of the aging network, which has multiple sites in every US state), health care systems and community health clinics, university extension services, parks and recreation centers, YMCAs and other health and fitness groups, and faith-based organizations.

Increase Visibility of Public Health Messages and Effective Interventions

It is important to raise the visibility of key public health messages about self-management education, physical activity, and healthy weight strategies as well as about the availability of arthritis self-management education and physical activity interventions for those with high need, such as older adults. Outreach to media, health care providers, and community members at large can all increase awareness of the importance of adopting self-management behaviors and of the availability and accessibility of public health interventions among adults with arthritis. The CDC is testing ways to link clinical and community services through a primary care practice–based outreach effort, using an academic detailing approach to inform primary care practitioners about these evidence-based interventions and to facilitate provider recommendations of the interventions to their patients with arthritis or other chronic diseases. The CDC is also testing a strategy to use grassroots marketing by experienced program participants to generate word-of-mouth program recommendations throughout communities.

Initiate Priority Policy and Environmental Change Strategies

Identifying, implementing, and evaluating policy strategies that will affect the prevention and management of arthritis will eventually reduce the burden and impact of these disabling conditions for older adults. Policies that reduce obesity in the general population (e.g., increase access to fruits and vegetables)62 and reduce or mitigate occupational and sports- and recreation-related joint injuries (e.g., implement work safety guidelines, promote wearing appropriate safety equipment) may be effective at preventing osteoarthritis. Policy and environmental changes to facilitate regular physical activity (e.g., provide walkable neighborhoods and access to safe places to be active) and participation in self-management education among people with arthritis can also substantially reduce the burden of arthritis. Policies that increase the reach of effective interventions will improve symptoms, function, and quality of life and delay disability for the millions of adults currently affected by arthritis.

CONCLUSIONS

Arthritis is a common condition and has a severe impact on older adults. Aggressively addressing arthritis pain and functional impairment among older adults through appropriate medical management and public health approaches, such as the use of community-based physical activity and self-management education interventions, may delay loss of independence and disability.

Acknowledgments

This article was prepared for the CDC series on aging and the roles of public health.

We thank Richard Goodman, MD, JD, MPH, and Lynda Anderson, PhD, of the Healthy Aging Program at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) for recruiting this article for the healthy aging series.

Note. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the CDC.

Human Participant Protection

Institutional review board approval was not needed, as this is a review article.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Prevalence and most common causes of disability among adults—United States, 2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58(16):421–426 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nevitt MC. Osteoporosis. : Klippel JH, Crofford LJ, Stone JH, Weyand CM, Primer on the Rheumatic Diseases. Atlanta: Arthritis Foundation; 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Song J, Chang RW, Dunlop DD. Population impact of arthritis on disability in older adults. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;55(2):248–255 [PAGAC report] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee Report, 2008. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2008. Available at: http://www.health.gov/paguidelines/Report/pdf/CommitteeReport.pdf. Accessed December 12, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kelley GA, Kelley KS, Hootman JM, Jones DL. Effects of community-deliverable exercise on pain and physical function in adults with arthritis and other rheumatic diseases: a meta-analysis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2011;63(1):79–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fransen M, McConnell S. Land-based exercise for osteoarthritis of the knee: a metaanalysis of randomized controlled trials. J Rheumatol. 2009;36(6):1109–1117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dunlop DD, Semanik P, Song J, Manheim LM, Shih V, Chang RW. Risk factors for functional decline in older adults with arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(4):1274–1282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Penninx BW, Messier SP, Rejeski WJet al. Physical exercise and the prevention of disability in activities of daily living in older persons with osteoarthritis. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161(19):2309–2316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Christensen R, Astrup A, Bliddal H. Weight loss: the treatment of choice for knee osteoarthritis? A randomized trial. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2005;13(1):20–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miller GD, Nicklas BJ, Davis C, Loeser RF, Lenchik L, Messier SP. Intensive weight loss program improves physical function in older obese adults with knee osteoarthritis. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2006;14(7):1219–1230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Messier SP, Loeser RF, Miller GDet al. Exercise and dietary weight loss in overweight and obese older adults with knee osteoarthritis: the Arthritis, Diet, and Activity Promotion Trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50(5):1501–1510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Christensen R, Bartels EM, Astrup A, Bliddal H. Effect of weight reduction in obese patients diagnosed with knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66(4):433–439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bliddal H, Christensen R. The treatment and prevention of knee osteoarthritis: a tool for clinical decision-making. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2009;10(11):1793–1804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shea MK, Houston DK, Nicklas BJet al. The effect of randomization to weight loss on total mortality in older overweight and obese adults: the ADAPT Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2010;65(5):519–525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.American College of Rheumatology Recommendations for the medical management of osteoarthritis of the hip and knee: 2000 update. American College of Rheumatology Subcommittee on Osteoarthritis Guidelines. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43(9):1905–1915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang W, Doherty M, Arden Net al. EULAR evidence based recommendations for the management of hip osteoarthritis: report of a task force of the EULAR Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutics (ESCISIT). Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64(5):669–681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang W, Moskowitz RW, Nuki Get al. OARSI recommendations for the management of hip and knee osteoarthritis, part II: OARSI evidence-based, expert consensus guidelines. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2008;16(2):137–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang W, Moskowitz RW, Nuki Get al. OARSI recommendations for the management of hip and knee osteoarthritis, part I: critical appraisal of existing treatment guidelines and systematic review of current research evidence. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2007;15(9):981–1000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brady TJ, Jernick SL, Hootman JM, Sniezek JE. Public health interventions for arthritis: expanding the toolbox of evidence-based interventions. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2009;18(12):1905–1917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Osteoarthritis Agenda Interventions Working Group Osteoarthritis Public Health Agenda. Intervention White Paper. Arthritis Foundation; 2008. Available at: http://www.arthritis.org/media/prevent%20osteoarthritis/OA%20Summit%20Intervention%20White%20Paper_attachments.pdf. Accessed December 12, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saag KG, Teng GG, Patkar NMet al. American College of Rheumatology American College of Rheumatology 2008 recommendations for the use of nonbiologic and biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59(6):762–784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Knevel R, Schoels M, Huizinga TWet al. Current evidence for a strategic approach to the management of rheumatoid arthritis with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: a systematic literature review informing the EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69(6):987–994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Strand V, Singh JA. Improved health-related quality of life with effective disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: evidence from randomized controlled trials. Am J Manag Care. 2008;14(4):234–254 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Korpela M, Laasonen L, Hannonen Pet al. FIN-RACo Trial Group Retardation of joint damage in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis by initial aggressive treatment with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: five-year experience from the FIN-RACo study. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50(7):2072–2081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Puolakka K, Kautiainen H, Möttönen Tet al. Impact of initial aggressive drug treatment with a combination of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs on the development of work disability in early rheumatoid arthritis: a five-year randomized followup trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50(1):55–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van der Linden MP, le Cessie S, Raza Ket al. Long-term impact of delay in assessment of patients with early arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62(12):3537–3546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shih M, Hootman JM, Kruger J, Helmick CG. Physical activity in men and women with arthritis: National Health Interview Survey, 2002. Am J Prev Med. 2006;30(5):385–393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Do BT, Hootman JM, Helmick CG, Brady TJ. Healthy People 2010 arthritis management objectives: monitoring prevalence of self-management education and provider counseling for weight loss and exercise. Ann Fam Med. 2011;9(2):136–141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.US Department of Health and Human Services Healthy People 2010. Washington, DC; 2000. Available at: http://www.health.gov/healthypeople. Accessed December 12, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 30.US Department of Health and Human Services Healthy People 2020. Washington, DC; 2010. Available at: http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/default.aspx. Accessed December 12, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hunter DJ, Neogi T, Hochberg MC. Quality of osteoarthritis management and the need for reform in the US. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2011;63(1):31–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hootman JM, Helmick CG, Schappert SM. Magnitude and characteristics of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions on ambulatory medical care visits, United States, 1997. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2002;47(6):571–581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Prevalence of doctor-diagnosed arthritis and arthritis-attributable activity limitation—United States, 2007–2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59(39):1261–1265 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hootman JM, Helmick CG. Projections of US prevalence of arthritis and associated activity limitations. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(1):226–229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lawrence RC, Felson DT, Helmick CGet al. National Arthritis Data Workgroup Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States. Part II. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58(1):26–35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Helmick CG, Felson DT, Lawrence RCet al. National Arthritis Data Workgroup Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States. Part I. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58(1):15–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bolen J, Schieb L, Hootman JMet al. Differences in the prevalence and impact of arthritis among racial/ethnic groups in the United States: National Health Interview Survey, 2002, 2003, and 2006. Prev Chronic Dis. 2010;7(3):A64. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Theis KA, Murphy L, Hootman JM, Helmick CG, Yelin E. Prevalence and correlates of arthritis-attributable work limitation in the US population among persons ages 18–64: 2002 National Health Interview survey data. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57(3):355–363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hootman JM, Cheng WV. Psychological distress and fair/poor health among adults with arthritis: state-specific prevalence and correlates of general health status, United States, 2007. Int J Public Health. 2009;54(suppl 1):S75–S83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Strine TW, Hootman JM, Okoro CAet al. Frequent mental distress status among adults with arthritis age 45 years and older, 2001. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;51(4):533–537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Furner SE, Hootman JM, Helmick CG, Bolen J, Zack MM. Health-related quality of life of US adults with arthritis: analysis of data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2003, 2005, and 2007. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2011;63(6):788–799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention State-specific trends in obesity prevalence among adults with arthritis: Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2003–2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(16):509–513 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National and state medical expenditures and lost earnings attributable to arthritis and other rheumatic conditions—United States, 2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2007;56(1):4–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Arthritis as a potential barrier to physical activity among adults with diabetes—United States, 2005 and 2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57(18):486–489 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Arthritis as a potential barrier to physical activity among adults with heart disease—United States, 2005 and 2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58(7):165–169 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Arthritis Foundation; Association of State and Territorial Health Officers; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Arthritis Action Plan: A Public Health Strategy. Atlanta: Arthritis Foundation; 1999. Available at: http://www.arthritis.org/naap.php. Accessed December 12, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sacks JJ, Harrold LR, Helmick CG, Gurwitz JH, Emani S, Yood RA. Validation of a surveillance case definition for arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2005;32(2):340–347 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bombard JM, Powell KE, Martin LM, Helmick CG, Wilson WH. Validity and reliability of self-reported arthritis, Georgia Senior Centers, 2000–2001. Am J Prev Med. 2005;28(3):251–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Arthritis prevalence and activity limitations—United States, 1990. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1994;43(24):433–438 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sacks JJ, Luo YH, Helmick CG. Prevalence of specific types of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the ambulatory health care system in the United States, 2001–2005. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2010;62(4):460–464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lethbridge-Cejku M, Helmick CG, Popovic J. Hospitalizations for arthritis and other rheumatic conditions: data from the 1997 National Hospital Discharge Survey. Med Care. 2003;41(12):1367–1373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention State Programs. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/arthritis/state_programs.htm. Accessed December 12, 2011

- 53.National Association of Chronic Disease Directors Arthritis Integration and Dissemination (AID) Projects. Available at: http://www.chronicdisease.org/nacdd-initiatives/arthritis/arthritis-integration-dissemination-aid-projects. Accessed December 12, 2011

- 54.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Arthritis Program Partnerships. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/arthritis/partners/partners.htm. Accessed December 12, 2011

- 55.Sacks JJ, Helmick CG, Luo YH, Ilowite NT, Bowyer S. Prevalence of and annual ambulatory health care visits for pediatric arthritis and other rheumatologic conditions in the United States in 2001–2004. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57(8):1439–1445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Aeffect, Inc Physical Activity. The Arthritis Pain Reliever. Health Communication Campaign Evaluation Report; April 2005 [Unpublished Report] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Brady TJ, Lam J. Impact of Buenos Días, Artritis, a Spanish health communications campaign promoting physical activity among Spanish-speaking people with arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:S611 [Google Scholar]

- 58.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Intervention Programs. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/arthritis/interventions.htm. Accessed December 12, 2011

- 59.Arthritis Foundation My Weapon Against Arthritis. Available at: www.fightarthritispain.org. Accessed December 12, 2011

- 60.Minor MA. 2002 Exercise and Physical Activity Conference St. Louis, Missouri: Exercise and Arthritis “We Know a Little Bit About a Lot of Things…” Arthritis Rheum. 2003;49(1):1–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention A National Public Health Agenda for Osteoarthritis 2010. Available at: www.cdc.gov/arthritis/docs/OAagenda.pdf. Accessed December 12, 2011

- 62.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Recommended community strategies and measurements to prevent obesity in the United States. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58(RR-7):1–26 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]