Abstract

The coral species Leptoseris troglodyta sp. n. (Scleractinia, Agariciidae) is described as new to science. It is the first known azooxanthellate shallow-water agariciid and is recorded from the ceilings of caves at 5-35 m depth in West Pacific coral reefs. The corals have monocentric cup-shaped calices. They may become colonial through extramural budding from the basal coenosteum, which may cause adjacent calices to fuse. The size, shape and habitat of Leptoseris troglodyta are unique compared to other Leptoseris species, many of which have been recorded from mesophotic depths. The absence of zooxanthellae indicates that it may survive well in darkness, but endolithic algae in some corals indicate that they may be able to get some light. The presence of menianes on the septal sides, which may help to absorb light at greater depths in zooxanthellate corals, have no obvious adaptive relevance in the new species and could have been inherited from ancestral species that perhaps were zooxanthellate. The new species may be azooxanthellate as derived through the loss of zooxanthellae, which would be a reversal in Leptoseris phylogeny.

Keywords: Cavernicolous, colonial, dwarfism, extramural budding, monocentric, skiophilous, solitary, troglobiotic

Introduction

Reef-dwelling species of the genus Leptoseris Milne-Edwards and Haime, 1849 (Scleractinia: Agariciidae) consist of foliaceous corals that are common in poorly illuminated environments, such as the deepest parts of reef slopes and vertical rocky walls with crevices, caves, tunnels and overhangs (Dinesen 1980, 1982, 1983; Waheed and Hoeksema in press). They are considered skiophilous (shade-loving) or cavernicolous, i.e., living in caves (Dinesen 1982, 1983). Because they appear to show more preference for dark habitats than many other reef corals, Leptoseris species constitute an important component of zooxanthellate scleractinian coral communities at mesophotic depths (30–150 m) (Kahng and Kelley 2007, Chan et al. 2009, Bare et al. 2010, Bongaerts et al. 2010, Kahng et al. 2010, Rooney et al. 2010, Dinesen et al. 2012). They may even occur deeper, with records of 153 and 165 m by Leptoseris hawaiiensis Vaughan, 1907, in the Pacific Ocean (Maragos and Jokiel 1986, Kahng and Maragos 2006), and 145 m by Leptoseris fragilis Milne Edwards and Haime 1849, in the Red Sea (Fricke and Schuhmacher 1983, Fricke et al. 1987, Kaiser et al. 1993).

Because some Leptoseris species inhabit deep and poorly accessible habitats, they may not all be well known. An example is the recently discovered Leptoseris kalayaanensis Licuanan & Aliño, 2009, which so far has only been recorded from rocky substrates at 13–28 m depth in the South China Sea basin (Licuanan and Aliño 2009, Hoeksema et al. 2010). It shows a distinct brown and white coloured pattern on its upper surface, consisting of areas that are either with or without zooxanthellae.

The Agariciidae were not known to include true deep-sea species but according to recent phylogenetic studies, the solitary attached deep-water coral Dactylotrochus cervicornis (Moseley, 1881), which was originally classified with the Caryophylliidae, is also a member of the Agariciidae (Kitahara et al. 2010, 2012). This species has a recorded depth range of 73–852 m, is therefore considered ahermatypic and probably azooxanthellate (for terminology see Schuhmacher and Zibrowius 1985, Cairns and Kitahara 2012). It is monocentric and has smooth-edged septa that bear 2–5 elongate ridges (menianes or latera), which are considered characteristic for the Agariciidae (Kitahara et al. 2010, 2012).

Because Dactylotrochus cervicornis is predomintly from deep water, it is considered the first known extant azooxanthellate agariciid. Dactylotrochus cervicornis holds a basal position in a recent phylogeny reconstruction of extant Agariciidae and because extinct solitary agariciids from the Middle Cretaceous were also solitary, it is assumed that the ancestor of the Agariciidae, which nowadays predominantly consist of colonial and zooxanthellate species, was also solitary and azooxanthellate (Kitahara et al. 2012).

In the present paper a new agariciid coral species is described that is entirely azooxanthellate and dwells on ceilings of caves in steep reef slopes and walls. No co-occurrence with any zooxanthellate scleractinians was observed. Although its calices are relatively small, cup-shaped and predominantly monocentric, it resembles species of Leptoseris,which otherwise is known to consist of zooxanthellate species with polycentric (“circumoral”) calices (Wells 1956). It is furthermore unique among extant reef-dwelling Agariciidae because it is modular (colonial) through extramural budding by growing new calices from a basal coenosteum, which eventually may fuse. It has been found in the western Pacific, including eastern Indonesia, central Philippines, Papua New Guinea, Palau and Guam. Most of its presently known distribution range overlaps with the centre of maximum marine species richness, the so-called Coral Triangle (Hoeksema 2007).

Methods

Specimens were observed, photographed and collected while diving with the help of SCUBA. All specimens were encountered below 5 m depth on the ceilings of caves inside steep reef slopes and walls, usually in areas with limestone outcrops. The caves measured one to several meters in width and several meters in length, enabling easy access and maneuvering for observations. Use of an underwater torch was indispensable to locate the corals. Collected specimens were soaked in fresh water or in sodium hypochlorite solution for cleaning. They were deposited in the Coelenterata collection (RMNH Coel.) of Naturalis Biodiversity Center, Leiden (formerly known as Rijksmuseum van Natuurlijke Historie). Specimens from Cebu were already available in the RMNH collection before they were photographed and collected for the present research. SEM photographs were taken with a Jeol 6480LV electron microscope operated at 10 kV.

Systematic section

Order Scleractinia Bourne, 1905. Family Agariciidae Gray, 1847. Genus Leptoseris Milne Edwards & Haime, 1849

Leptoseris troglodyta sp. n.

urn:lsid:zoobank.org:act:DB802B45-E18D-4F55-9D23-5401660DD94E

http://species-id.net/wiki/Leptoseris_troglodyta

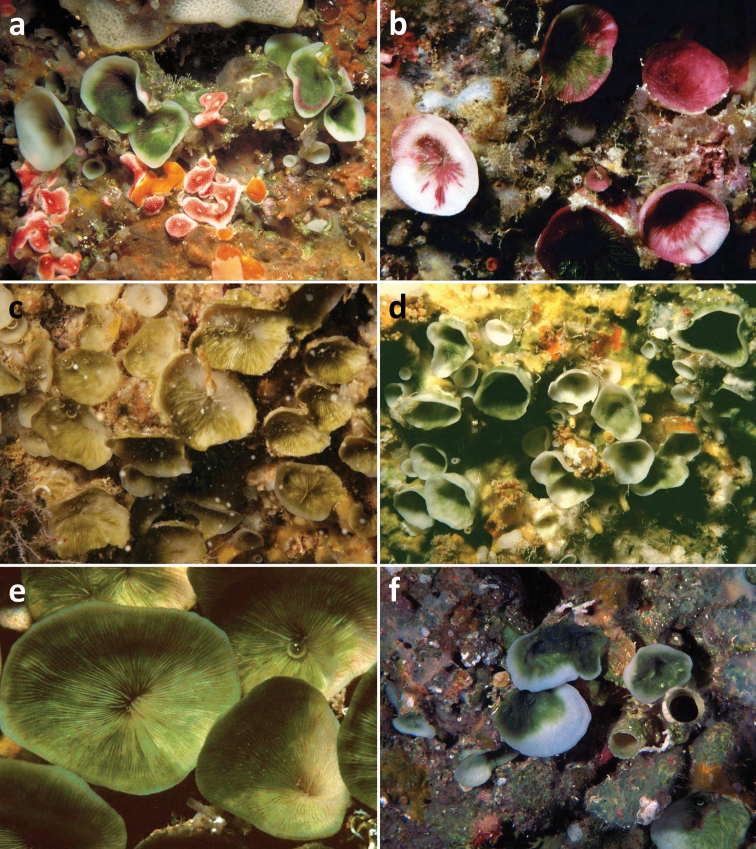

Figure 1.

Living specimens of Leptoseris troglodyta sp. n. a Philippines, Cebu Strait, W of Bohol, NW of Cabilao Island, 10–30 m depth (7 November 1999) b Indonesia, NE Kalimantan, Berau Islands, S of Derawan Island, 7–10 m depth (4 October 2003).

Figure 2.

Living specimens of Leptoseris troglodyta sp. n. a Philippines, Cebu Strait, W of Bohol, NW of Cabilao Island, 10–30 m depth (7 November 1999) b Indonesia, Tukang Besi Islands (Wakatobi), Binongko, 20 m depth (10 May 2003) c Indonesia, North Sulawesi, S of Bunaken Island, 17 m depth (19 December 2008; photo B.T. Reijnen) d Palau, W of Ulong Island (Rattakadokoru Island), W off barrier reef, 32 m depth (28 July 2002) e Papua New Guinea, Misima Island, 6–10 m depth (31 May 1998; photo G. Paulay) f Guam, Blue Hole, 35 m depth (1 June 2000; photo G. Paulay).

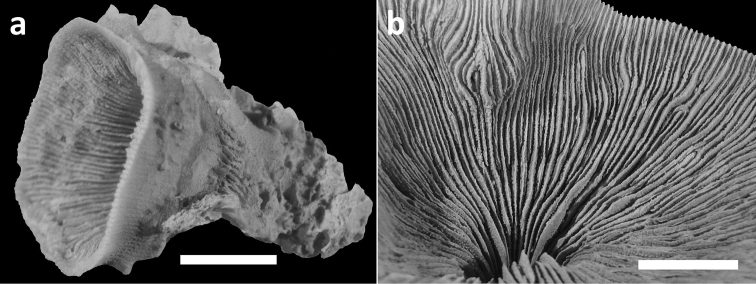

Figure 3.

Holotype (RMNH Coel. 40138) and three paratypes (RMNH Coel. 40139) of Leptoseris troglodyta sp. n.from Palau. Scale bars: 1 cm. a Holotype consists of four calices: one (most left) has fused mid-height its calyx with two totally fused calices (centre), while another (right) has fused only with its corallum margin to those at the centre and the rest of its calyx has remained separate b Paratype: two separate calyces c Paratype: single calyx d Paratype: two fused calices. Scale bars: 1 cm.

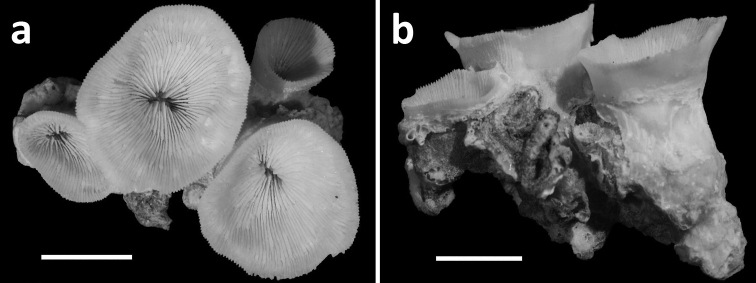

Figure 4.

Specimens of Leptoseris troglodyta sp. n.from Indonesia, Wakatobi (RMNH Coel. 40152) a Single specimen from the side showing cup-shaped calyx shape and costae with fine granular spines (scale bar: 1 cm) b Close-up of large calyx showing septa with wide menianes along their sides (see Figure 5; scale bar: 5 mm).

Figure 5.

SEM photographs of Leptoseris troglodyta sp. n. from Wakatobi, Indonesia (RMNH Coel. 40152). a Upper side of septa showing wide menianes (scale bar: 1 mm; insert: Figure 5b) b Close-up (insert) of Figure 5a (arrows: menianes; scale bar: 0.5 mm) c Cross-section of septa showing multiple menianes along their sides (scale bar: 0.5 mm; insert: Figure 5d) d Close-up (insert) of Figure 5c (arrows: menianes; scale bar: 0.5 mm).

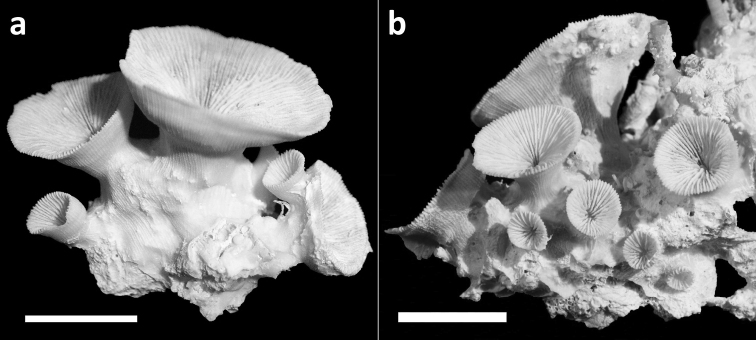

Figure 6.

Specimens of Leptoseris troglodyta sp. n. from the Philippines, Cebu, Mactan Island, (RMNH Coel. 40151). Scale bars: 1 cm. a Upper side of a specimen showing four separate calices b Three calices that are partly fused at their sides.

Figure 7.

Specimens of Leptoseris troglodyta sp. n.from the Philippines, W of Bohol, NW side of Cabilao Island (RMNH Coel 24195). Scale bars: 1 cm. a Cluster of calices formed by extra-calicular budding showing costae with small granular spines b Idem.

Figure 8.

Specimens of Leptoseris troglodyta sp. n. from the Philippines, W of Bohol, NW side of Cabilao Island (RMNH Coel 24195). Scale bars: 5 mm a Single calyx from above, showing nearly solid columella in the fossa b Two totally fused monocentric calices showing, each with its own fossa c Upper side of calyx showing clearly visible granulation on septal sides d Calyx showing solid corallum wall covered by costae with fine granular spines.

Leptoseris sp. Hoeksemaand Van Ofwegen 2004.

Type material.

Holotype. RMNH Coel. 40138 (1 specimen, dry, Figure 3a), Palau, W of Ulong Island (Rattakadokoru Island), W off barrier reef, 07°18'40"N, 134°13'30"E, Tsey’s tunnel ceiling at 32 m depth, 28 July 2002, coll. B.W. Hoeksema. Paratypes: RMNH Coel. 40139 (15 specimens, dry), same collection data (Figures 2d, 3b–d).

Other material examined.

Philippines. RMNH Coel. 24187 (3 specimens, dry), RMNH Coel 24195 (36 specimens, dry), Cebu Strait, W of Bohol, NW side of Cabilao Island, 09°53'12"N, 123°45'32"E, vertical wall with caves,10–30 m depth, 7 and 17 November 1999, coll. B.W. Hoeksema (Figures 1a, 2a, 7, 8). RMNH Coel. 40151 (2 specimens, dry), Philippines, Cebu, Mactan Island, Lapu-Lapu City, Marigondon Cave, 10°15'33"N, 123°59'07"E, ceiling of cave at 25-30 m depth, May 1981, coll. M.B. Best (Figure 6). Indonesia. RMNH Coel. 40152 (7 specimens, dry), Tukang Besi Islands (Wakatobi), Binongko, SW Bay, 05°59'47"S, 124°02'55"E, cave in steep wall 20 m depth, 10 May 2003, coll. B.W. Hoeksema (Figures 2b, 4–5). RMNH Coel. 40150 (25 specimens, ethanol), Tukang Besi Islands (Wakatobi), NE Hoga Island, 05°28'S, 123°47'E, cave in steep reef slope 5 m depth, 12 July 2011, coll. B.W. Hoeksema. RMNH Coel. 40137 (2 specimens, ethanol), North Sulawesi, South of Bunaken Island, Alung Banua village, 01°37'07"N, 124°45'30"E, tunnel in reef wall 17 m depth, 19 December 2008, coll. B.T. Reijnen and S.E.T van der Meij (Figure 2c).

Additional photographic records:

Indonesia, NE Kalimantan, Berau Islands, S of Derawan Island, jetty Derawan Dive Resort, 02°17'03"N, 118°14'49"E, ceiling of caves, 7–10 m deep (4 October 2003; Figure 1b). Papua New Guinea, Off SE point, Misima Island, Pt. Ebola, 6–10 m depth (31 May 1998; Figure 2e). Guam,Blue Hole, 35 m depth (1 June 2000; Figure 2f).

Description.

Corallum attached and solitary or colonial by budding from basal coenosteum (Figures 3–4, 6–8). Calices predominantly monocentric, very thin, cup-shaped to foliaceous, height < 15 mm, outline irregularly circular, Ø < 30 mm (Figures 1–4, 6–8). They are usually separate from each other above the interconnecting basal plate (Figures 3b, 6, 7), but can also be fused at their margins or lateral sides (Figures 3a, 8b). Corallum wall massive. Costae equal and well defined, with small spiny protuberances (Figures 4a, 7a, 8d). Septa approximately equal in size, with smooth upper edges and parallel ridges (menianes) on their sides (Figures 3, 5, 8). Septal sides may show evenly distributed granulations where menianes are absent (Figures 8b–c). Columella nearly solid (Figures 3a, 3c–d, 8a–b). Living animals azooxanthellate; corals are white, or partly green or red (Figures 1–2), owing to the presence of endolithic algae (Kühl and Polerecky 2008).

Diagnosis.

Corals cave-dwelling, azooxanthellate. Calices small, cup-shaped, monocentric or fused, forming buds at basal coenosteum.

Etymology.

The epithet troglodyta (noun) means cave dweller in Latin, derived from ancient Greek for “one who dwells in holes”.

Distribution.

Records are from coral reefs, usually in areas with limestone outcrops: Indonesia (East Kalimantan, North Sulawesi, Southeast Sulawesi), the central Philippines (Cebu, Bohol), Palau, eastern Papua New Guinea, and the Marianas (Guam) (Figure 9).

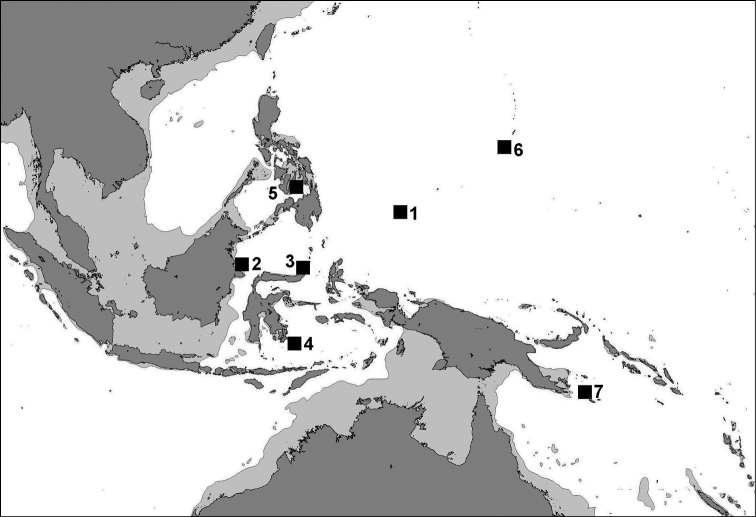

Figure 9.

Distribution map ofLeptoseris troglodyta sp. n. showing records at (1) Palau, (2) East Kalimantan, (3) North Sulawesi, (4) Wakatobi, (5) Bohol, (6) Guam, (7), eastern Papua New Guinea.

Discussion

Systematics

Leptoseris troglodyta sp. n. has a habitat and growth form unlike any other known Leptoseris; its corals are cavernicolous and azooxanthellate, and have small, monocentric calices that may multiply by extramural budding and fuse. Other Leptoseris species are polycentric by circumoral and marginal budding (Dinesen 1980, Veron and Pichon 1980, Veron 2000, Licuanan and Aliño 2009). All congeneric species are larger, which may be related to their symbiosis with zooxanthellae. Polycentric species are usually bigger than close relatives with monocentric calices, as demonstrated for mushroom corals (Hoeksema 1991b, Gittenberger et al. 2011).

The new species lacks pigments of its own, like many cavernicolous (= troglobiotic) animals. Although there are no zooxanthellae in its soft tissue, it usually contains green or red shade-adapted endolithic cyanobacteria imbedded in the skeleton, which have also been reported from Leptoseris fragilis Milne-Edwards and Haime, 1849 (Schlichter et al. 1997).

Dinesen (1983) mentions the occurrence of “numerous Leptoseris cf. scabra (G. Hodgson, M. Ross, pers. comm.)”, which were observed in 1981 on the ceiling inside the large Marigondon Cave (Mactan Island, Cebu), the Philippines. They were found “further back in the cave, in gloomier conditions” than the cave entrance at ca 30 m depth. It is likely that this record pertains to specimens of the new species. Two corals of the present study were collected at that site in 1981 and were available for study in the RMNH collection in Leiden. These specimens confirm that the new species was present at that locality at that time. Museum collections may indeed help to retrieve information on the earlier occurrence of coral species that have not been recorded before (Van der Meij et al. 2010, Hoeksema et al. 2011, Van der Meij and Visser 2011). However, without field observations it would not have been possible to know that the new species lacks zooxanthellae.

Despite its unique small monocentric corallites and lack of zooxanthellae, the new species is classified with Leptoseris because of similarly shaped septa and costae, and by its thin, cup-shaped or foliaceous coralla somewhat resembling those of Leptoseris fragilis. The latter species features corals that can be monocentric, but its calices grow larger (Ø > 50 mm) and may eventually form secondary stomata by intracalicular, circumoral budding. Other extinct agariciid genera predominantly consist of encrusting and massive, polystomatous species (Wells 1954, Veron 2000).

Support from molecular analyses (Stefani et al. in prep) would be needed to justify the position of the new species in a separate genus instead of Leptoseris. In that case, it could be appropriate to classify it with Trochoseris Milne Edwards & Haime, 1849, an extinct genus (Mid Cretaceous – Oligocene) consisting of corals that are solitary, attached and turbinate or trochoid (Wells 1956). However, molecular analyses cannot support such a transition because no live material is available of this genus.

The corals have a basic growth form like that of Cladopsammia gracilis (Milne Edwards and Haime 1848) (Dendrophylliidae), i.e., by extramural budding from the basal coenosteum (see Cairns 1991). They are not distinctly reptoid as described for some Rhizopsammia species of the same family (Cairns and Zibrowius 1997) because there are no clear basal costate stolons involved. Extramural budding is also shown by fossils of the extinct genus Brachyphyllia Reuss, 1854 (Agariciidae), which has thick, low plocoid corallites (Wells 1956) instead of the thin cup-shaped corallites shown by the new species. Compared to the extant solitary agariciid deep-water species Dactylotrochus cervicornis (see Wells 1954, Cairns 1999, Kitahara et al. 2012, Cairns and Kitahara 2012), Leptoseris troglodyta differs by the capacity to become colonial and by having a circular corallum outline instead of a periphery with thecal extensions. Only a few specimens of Dactylotrochus cervicornis are known to show an ‘aberrant’ tendency for coloniality (Kitahara et al. 2012).

Evolution of symbiosis with zooxanthellae

Leptoseris troglodyta is the first extant shallow-water agariciid known known to be reef-dwelling and azooxanthellate. The extinct agariciid genera, Trochoseris Milne Edwards & Haime, 1849 and Vaughanoseris Wells, 1934, also consists of monocentric species; the first being attached and turbinate or trochoid, and the second being free-living and discoid (Wells 1956). According to Kitahara et al. (2012) they could have been azooxanthellate because the extant Dactylotrochus cervicornis, which shows a basal position in the phylogeny reconstruction of the Agariciidae, is considered both azooxanthellate and monocentric. However, the phylogenetic positions of the two extinct taxa are unknown and although they share a (supposedly plesiosmorph) solitary growth form with Dactylotrochus, this does not necessarily imply that they are phylogenetically closely related to each other. For example, several phylogenetic lineages within the reef-dwelling mushroom coral family Fungiidae show an evolution from monocentric to polycentric zooxanthellate corals, implying that not all monocentric fungiid species are directly related to each other (Hoeksema 1989, 1991b, Gittenberger et al. 2011, Benzoni et al. 2012).

Coincidently, the Fungiidae show many examples of solitary free-living species that resemble the extinct Vaughanoseris. So, regarding their lifestyle, Vaughanoseris species could be reef-dwelling and zooxanthellate as well. Moreover, the attached, monocentric dendrophylliid Balanophyllia europaea (Risso, 1826) is an example of a single zooxanthellate species (Schuhmacher and Zibrowius 1985) among a majority of congeners without zooaxanthellae (Cairns et al. 1999). Its growth form resembles that of Trochoseris, for which the absence of zooxanthellae may therefore perhaps be less certain. Nevertheless, a solitary growth form, an old fossil record, and a possible ancestral position in the phylogeny may not be sufficient to predict whether an extinct coral taxon may have been azooxanthellate. Its habitat (especially depth) may be more indicative, especially if species were shallow reef-dwellers.

The deep-water species Dactylotrochus cervicornis and the cave-dweller Leptoseris troglodyta posses parallel ridges on the sides of their septa, which are called menianes (Kitahara et al. 2010, 2012). These are probably the same structures (compare Figure 5, Kitahara et al. 2012 figure 2, and Kahng et al. 2012 figure 9) that help zooxanthellate Leptoseris corals to absorb sunlight more efficiently at greater depths (Kahng et al. 2012). The bathymetric records of Dactylotrochus cervicornis (Kitahara et al. 2012) partly coincide with depth ranges of zooxanthellate Leptoseris species (see Dinesen et al. 2012). Depth may therefore not always be indicative for the absence of zooxanthellae.

All live specimens of Leptoseris troglodyta, which were observed in their habitat (Figures 1–2), were clearly azooxanthellate by lacking a brown colour, like completely bleached corals (Hoeksema 1991a, Hoeksema and Matthews 2011). In the case of dredged deep sea corals in collections, which are either dry or being preserved in ethanol, pigments of any present zooaxanthellae might have dissolved, which makes it difficult to see whether they were present. If Dactylotrochus cervicornis corals lack zooxanthellae, like those of Leptoseris troglodyta, the presence of menianes at least suggests that their ancestors might have been zooxanthellate and that the loss of zooxanthellae may be an evolutionary novelty related to life in deep water or in caves. Consequently, ancestral agariciids, along with Trochoseris and Vaughanoseris, were perhaps also zooxanthellate like many modern monocentric zooxanthellate reef corals in illuminated habitats. On the other hand, a preceding presence of menianes in agariciid corals may also have facilitated the development of symbiosis with zooxanthellae, which implies that early agariciids may have been azooxanthellate as suggested by Kitahara et al. (2012), presenting a “chicken or the egg” causality dilemma.

The deep-water species Dactylotrochus cervicornis and the cave-dweller Leptoseris troglodyta both live in dark environments. The latter has been observed to be azooxanthellate in caves at various localities. Dactylotrochus cervicornis specimens may have to be examined for the absence of zooxanthellae to be sure that this species is always azooxanthellate. If so, its menianes have no use in connection to light absorption, like in Leptoseris troglodyta. Leptoseris troglodyta shows that the evolutionary relation between scleractinian reef corals and their algal symbionts is not fixed and that it may be difficult to deduct such a relation based on coral growth forms and their possible position in phylogeny reconstructions, especially if no molecular data can be obtained, as is the case for fossil corals. According to a recent molecular study, coloniality may have become lost at least six times and symbiosis with zooxanthellae at least three times in the phylogeny of the Scleractinia (Barbeitos et al. 2010). However, these numbers are based on a subset of species and may have to be revised if additional species are involved (see Gittenberger et al. 2011).

Eco-morphological considerations

Leptoseris troglodyta sp. n. is the first reef-dwelling agariciid coral without zooxanthellae. As a small cave-dwelling species it can live without sunlight. It has not been observed to co-occur with any zooxanthellate scleractinians (only azooxanthellate species), although in small and poorly illuminated cavities a variety of zooxanthellate scleractinians can be discerned (Dinesen 1983). Other Leptoseris species are zooxanthellate and most of them are able to live on deep, poorly illuminated reefs or rocky substrates. Therefore, from an evolutionary perspective, the new species may have lost the capacity to live in symbiosis with zooxanthellae and it may have obtained a smaller corallum size (dwarfism). By their small and thin corolla the corals have little weight. Consequently, with their wide basal plate they may not easily break off from their substrate, which consist of porous limestone cave ceilings where settlement space is limited. Without zooxanthellae, they may not easily reach large sizes, whatsoever. Owing to its modular growth form a Leptoseris troglodyta coral may risk losing a few expendable calices while other Leptoseris corals may harm and lose their entire corallum in unfavourable conditions. Other examples of zooxanthellae loss in relation to a cavernicolous lifestyle are so far unknown among scleractinian families. However, among shallow-water brachycnemic zoanthids an undescribed cave-dwelling Palythoa species has been recorded that also lacks zooxanthellae, while its congeners are known to be zooxanthellate (Reimer 2010).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

I want to thank the following people, organizations and institutes who assisted during the fieldwork or other parts of the research: Dr Pat Colin and Ms Lori Colin (Coral Reef Research Foundation, Palau), Dr Filipina B. Sotto and Dr Thomas Heeger (University of San Carlos, Cebu City); Dr Arjan Gittenberger (Naturalis and Leiden University), The Nature Conservancy, Operation Wallacea (Wakatobi, Indonesia), Research Centre for Oceanography, Indonesian Institute of Sciences (PPO-LIPI, Jakarta). Fieldwork was funded by the Schure-Beijerinck-Popping Fonds. Mr Bastian T. Reijnen and Ms Sancia E.T. van der Meij supplied material and photos from North Sulawesi. Dr Gustav Paulay generously provided photos and accompanying data of specimens from Guam and Papua New Guinea. Dr Leen P. van Ofwegen took the SEM photographs. I am grateful to Dr Francesca Benzoni, Dr Marcelo Kitahara, and various other members of the Scleractinia Systematics Working Group (SSWG) for their suggestions given during discussions. I thank Ms Zarinah Waheed and two reviewers, Dr Zena Dinesen and Dr Marcelo Kitahara, for constructive remarks on early drafts of the manuscript.

References

- Barbeitos MS, Romano SL, Lasker HR. (2010) Repeated loss of coloniality and symbiosis in scleractinian corals. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 107: 11877-11882. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914380107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bare AY, Grimshaw KL, Rooney JJ, Sabater MG, Fenner D, Carroll B. (2010) Mesophotic communities of the insular shelf at Tutuila, American Samoa. Coral Reefs 29: 369-377. doi: 10.1007/s00338-010-0600-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Benzoni F, Arrigoni R, Stefani F, Reijnen BT, Montano S, Hoeksema BW. (2012) Phylogenetic position and taxonomy of Cycloseris explanulata and C. wellsi (Scleractinia: Fungiidae): lost mushroom corals find their way home. Contributions to Zoology 81: 125-146. [Google Scholar]

- Bongaerts P, Ridgway T, Sampayo EM, Hoegh-Guldberg O. (2010) Assessing the ‘deep reef refugia’ hypothesis: focus on Caribbean reefs. Coral Reefs 29: 309-327. doi: 10.1007/s00338-009-0581-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bourne GC. (1905) Report on the solitary corals collected by Professor Herdmann, at Ceylon, in 1902. Ceylon Pearl Oyster Fisheries, Part 4, Supplementary Report 29: 187–242, pls. 1–4.

- Cairns SD. (1991) A revision of the ahermatypic Scleractinia of the Galapagos and Cocos Islands. Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology 504: 1–32, pls 1–12. doi: 10.5479/si.00810282.504 [DOI]

- Cairns SD. (1999) Cnidaria Anthozoa: deep-water azooxanthellate Scleractinia from Vanuatu, and Wallis and Futuna islands. Mémoires du Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle 180: 31-167. [Google Scholar]

- Cairns SD, Kitahara MV. (2012) An illustrated key to the genera and subgenera of the Recent azooxanthellate Scleractinia (Cnidaria: Anthozoa), with an attached glossary. ZooKeys 227: 1-47. doi: 10.3897/zookeys.227.3612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cairns SD, Zibrowius H. (1997) Cnidaria Anthozoa: Azooxanthellate Scleractinia from the Philippine and Indonesian regions. Mémoires du Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle 172: 27-243. [Google Scholar]

- Cairns SD, Hoeksema BW, Van der Land J. (1999) List of extant stony corals. Atoll Research Bulletin 459: 13-46. [Google Scholar]

- Chan YL, Pochon X, Fisher MA, Wagner D, Concepcion GT, Kahng SE, Toonen RJ, Gates RD. (2009) Generalist dinoflagellate endosymbionts and host genotype diversity detected from mesophotic (67–100 m depths) coral Leptoseris. BMC Ecology 2009, 9: 21 doi: 10.1186/1472-6785-9-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Dinesen ZD. (1980) A revision of the coral genus Leptoseris (Scleractinia: Fungina: Agariciidae). Memoirs of the Queensland Museum 20: 182-235. [Google Scholar]

- Dinesen ZD. (1982). Regional variation in shade-dwelling coral assemblages of the Great Barrier Reef Province. Marine Ecology Progress Series 7: 117-123. doi: 10.3354/meps007117 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dinesen ZD. (1983) Shade-dwelling corals of the Great Barrier Reef. Marine Ecology Progress Series 10: 173-185. doi: 10.3354/meps010173 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dinesen ZD, Bridge TCL, Luck DG, Kahng SE, Bongaerts P. (2012) Importance of the coral genus Leptoseris to mesophotic coral communities in the lndo-Pacific. Poster 12th International Coral Reef Symposium, Cairns, 2012: P101.

- Fricke HW, Schuhmacher H. (1983) The depth limits of Red Sea stony corals: an ecophysiological problem (a deep diving survey by submersible). PSZNI: Marine Ecology 4: 163−194. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0485.1983.tb00294.x [DOI]

- Fricke HW, Vareschi E, Schlichter D. (1987) Photoecology of the coral Leptoseris fragilis in the Red Sea twilight zone (an experimental study by submersible). Oecologia 73: 371−381. doi: 10.1007/BF00385253 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Gittenberger A, Reijnen BT, Hoeksema BW. (2011) A molecularly based phylogeny reconstruction of mushroom corals (Scleractinia: Fungiidae) with taxonomic consequences and evolutionary implications for life history traits. Contributions to Zoology 80: 107-132. [Google Scholar]

- Gray JE. (1847) An outline of an arrangement of stony corals. Annals and Magazine of Natural History, Ser. 1, 19: 120–128. doi: 10.1080/037454809496460 [DOI]

- Hoeksema BW. (1989) Taxonomy, phylogeny and biogeography of mushroom corals (Scleractinia: Fungiidae). Zoologische Verhandelingen Leiden 254: 1-295. [Google Scholar]

- Hoeksema BW. (1991a) Control of bleaching in mushroom coral populations (Scleractinia: Fungiidae) in the Java Sea: stress tolerance and interference by life history strategy. Marine Ecology Progress Series 74: 225-237. doi: 10.3354/meps074225 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hoeksema BW. (1991b) Evolution of body size in mushroom corals (Scleractinia: Fungiidae) and its ecomorphological consequences. Netherlands Journal of Zoology 41: 122-139. [Google Scholar]

- Hoeksema BW. (2007) Delineation of the Indo-Malayan centre of maximum marine biodiversity: the Coral Triangle. In: Renema W. (Ed). Biogeography, Time and Place: Distributions, Barriers and Islands. Springer, Dordrecht: 117-178. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4020-6374-9_5 [DOI]

- Hoeksema BW, Matthews JL. (2011) Contrasting bleaching patterns in mushroom coral assemblages at Koh Tao, Gulf of Thailand. Coral Reefs 30: 95. doi: 10.1007/s00338-010-0675-5 [DOI]

- Hoeksema BW, Van Ofwegen LP. (2004) Indo-Malayan reef corals: a generic overview. World Biodiversity database, CD-ROM Series ETI, Amsterdam.

- Hoeksema BW, Dautova TN, Savinkin OV, Tuan VS, Ben HX, Hoang PK, Du HT. (2010) The westernmost record of the coral Leptoseris kalayaanensis in the South China Sea. Zoological Studies 49: 325.

- Hoeksema BW, Van der Land J, Van der Meij SET, Van Ofwegen LP, Reijnen BT, Van Soest RWM, De Voogd NJ. (2011) Unforeseen importance of historical collections as baselines to determine biotic change of coral reefs: the Saba Bank case. Marine Ecology 32: 135-141. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0485.2011.00434.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kahng SE, Kelley C. (2007) Vertical zonation of megabenthic taxa on a deep photosynthetic reef (50−140 m) in the Au’au Channel, Hawaii. Coral Reefs 26: 679−687. doi: 10.1007/s00338-007-0253-7 [DOI]

- Kahng SE, Maragos JE. (2006) The deepest zooxanthellate, scleractinian corals in the world? Coral Reefs 25: 254. doi: 10.1007/s00338-006-0098-5 [DOI]

- Kahng SE, Garcia-Sais JR, Spalding HL, Brokovich E, Wagner D, Weil E, Hinderstein L, Toonen RJ. (2010) Community ecology of mesophotic coral reef ecosystems. Coral Reefs 29: 255-275. doi: 10.1007/s00338-010-0593-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kahng SE, Hochberg EJ, Aprill A, Wagner D, Luck DG, Perez D, Bidigare RR. (2012) Efficient light harvesting in deep-water zooxanthellate corals. Marine Ecology Progress Series 455: 65-77. doi: 10.3354/meps09657 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser P, Schlichter D, Fricke HW. (1993) Influence of light on algal symbionts of the deep coral Leptoseris fragilis. Marine Biology 117: 45-52. doi: 10.1007/BF00346424 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kitahara MV, Cairns SD, Stolarski J, Blair D, Miller DJ. (2010) A comprehensive phylogenetic analysis of the Scleractinia (Cnidaria, Anthozoa) based on mitochondrial CO1 sequence data. PLoS ONE 5(7): e11490. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kitahara MV, Stolarski J, Miller DJ, Benzoni F, Stake J, Cairns SD. (2012) The first modern solitary Agariciidae (Anthozoa, Scleractinia) revealed by molecular and microstructural analysis. Invertebrate Systematics 26: 303-315. doi: 10.1071/IS11053 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kühl M, Polerecky L. (2008) Functional and structural imaging of phototrophic microbial communities and symbioses. Aquatic Microbial Ecology 53: 99-118. doi: 10.3354/ame01224 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Licuanan WY, Aliño PM. (2009) Leptoseris kalayaanensis (Scleractinia: Agariciidae), a new coral species from the Philippines. Raffles Bulletin of Zoology 57: 1-4. [Google Scholar]

- Maragos JE, Jokiel P. (1986) Reef corals of Johnston Atoll: one of the world’s most isolated reefs. Coral Reefs 4: 141-150. doi: 10.1007/BF00427935 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Milne Edwards H, Haime J. (1848) Recherches sur les polypiers. Troisième mémoire. Monographie des Eupsammides. Annales des Sciences Naturelles, Zoologie, Ser. 3, 10: 65–114, pl. 1.

- Milne Edwards H, Haime J. (1849) Recherches sur les polypiers. Quatrième mémoire. Monographie des Astréides. Annales des Sciences Naturelles, Zoologie, Ser. 3, 11: 235–312.

- Moseley HN. (1881) Report on certain hydroid, alcyonarian, and madreporarian corals procured during the voyage of H.M.S. Challenger, in the years 1873–1876. Challenger Reports, Zoology 2: 1–248, pls. 1–32.

- Reimer JD. (2010) Key to field identification of shallow water brachycnemic zoanthids (Order Zoantharia: Suborder Brachycnemina) present in Okinawa. Galaxea, Journal of Coral Reef Studies 12: 23-29. doi: 10.3755/galaxea.12.23 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reuss AE. (1854) Beiträge zur Characteristik der Kreideschichten in den Ostalpen besonders im Gosauthale und am Wolfgangsee. Denkschriften der Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftlichen Klasse der Kaiserlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Wien 7 (1): 1–157, pls. 1–31.

- Risso A. (1826) Tableau des zoophytes les plus ordinaires qui existent ou qui ont existé dans les Alpes Maritimes. In: Risso A, Histoire naturelle des principales productions de l’Europe méridionale et particulièrement de celles des environs de Nice et des Alpes Maritimes. Levrault, Paris, 5: 307–383, pl. 3. doi: 10.5962/bhl.title.58984 [DOI]

- Rooney J, Donham E, Montgomery A, Spalding H, Parrish F, Boland R, Fenner D, Gove J, Vetter O. (2010) Mesophotic coral ecosystems in the Hawaiian Archipelago. Coral Reefs 29: 361-367. doi: 10.1007/s00338-010-0596-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schlichter D, Kampmann H, Conrady S. (1997) Trophic potential and photoecology of endolithic algae living within coral skeletons. PSZNI: Marine Ecology 18: 299−317. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0485.1997.tb00444.x [DOI]

- Schuhmacher H, Zibrowius H. (1985) What is hermatypic? A redefinition of ecological groups of corals and other organisms. Coral Reefs 4: 1-9. doi: 10.1007/BF00302198 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan TW. (1907) Recent Madreporaria of the Hawaiian Islands and Laysan. Bulletin of the United States National Museum 59: i-iv, 1–427, pls. 1–96. doi: 10.5479/si.03629236.59.i [DOI]

- Van der Meij SET, Visser RR. (2011) The Acropora humilis group (Scleractinia) of the Snellius expedition (1929–30). Raffles Bulletin of Zoology 59: 9-17. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Meij SET, Suharsono, Hoeksema BW. (2010) Long-term changes in coral assemblages under natural and anthropogenic stress in Jakarta Bay (1920–2005). Marine Pollution Bulletin 60: 1442-1454. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2010.05.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veron JEN. (2000) Corals of the world. Volume 2. Australian Institute of Marine Science, Townsville, 429 pp. [Google Scholar]

- Veron JEN, Pichon M. (1980) Scleractinia of Eastern Australia III. Families Agariciidae, Siderastreidae, Fungiidae, Oculinidae, Merulinidae, Mussidae, Pectiniidae, Caryophylliidae, Dendrophylliidae. Australian Institute of Marine Science Monograph Series 4: 1-422. doi: 10.5962/bhl.title.60646 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Waheed Z, Hoeksema BW. (in press) A tale of two winds: species richness patterns of reef corals around the Semporna peninsula, Malaysia. Marine Biodiversity. doi: 10.1007/s12526-012-0130-7 [DOI]

- Wells JW. (1934) Some fossil corals from the West Indies. Proceedings of the United States National Museum, Washington 83: 71–110, pls. 1–5. doi: 10.5479/si.00963801.83-2975.71 [DOI]

- Wells JW. (1954) Recent corals of the Marshall Islands. United States Geological Survey, Professional Paper260-I: i-iv, 385–486, pls. 94–187.

- Wells JW. (1956) Scleractinia. In Moore RC (Ed) Treatise on invertebrate paleontology F. Coelenterata. Geologial Society of America and University of Kansas Press, 328–440.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.